Abstract

Purpose:

The objective of this study was to quantify age-related changes in accelerometer-derived day-level physical activity and sedentary behavior pattern metrics (i.e., number, length, and temporal dispersion of bouts and breaks) across three years of middle childhood. Differences by child sex and weekend vs. weekday were examined.

Method:

Children (N = 169, 54% female, 56% Hispanic; 8–12 years old at enrollment) participated in a longitudinal study with six assessments across three years. Day-level moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA; i.e., total min, number of short [<10 min] bouts, proportion of long [≥20 min] bouts, temporal dispersion) and sedentary behavior (i.e., total min, number of breaks, proportion of long [≥60 min] bouts, temporal dispersion) pattern metrics were measured using a waist-worn accelerometer (Actigraph GT3X).

Results:

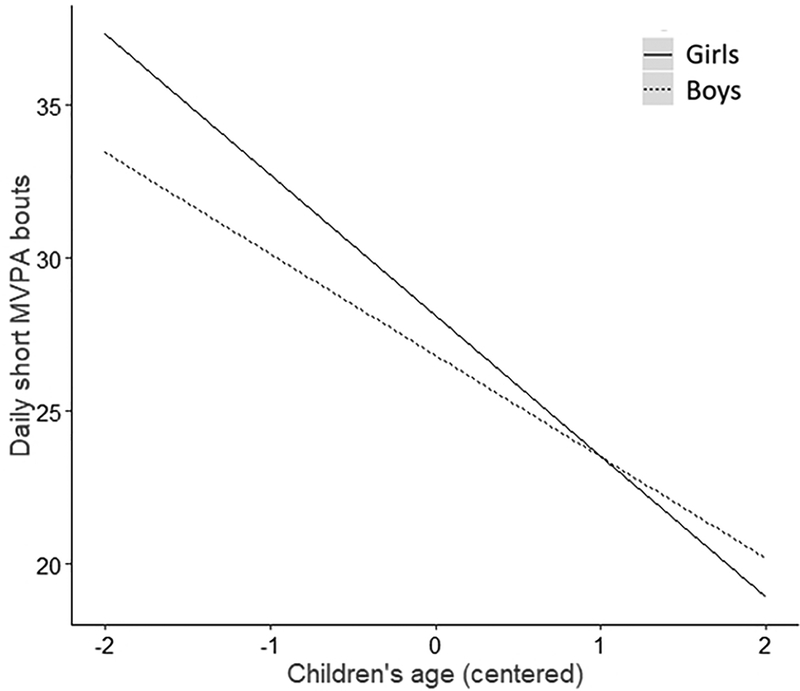

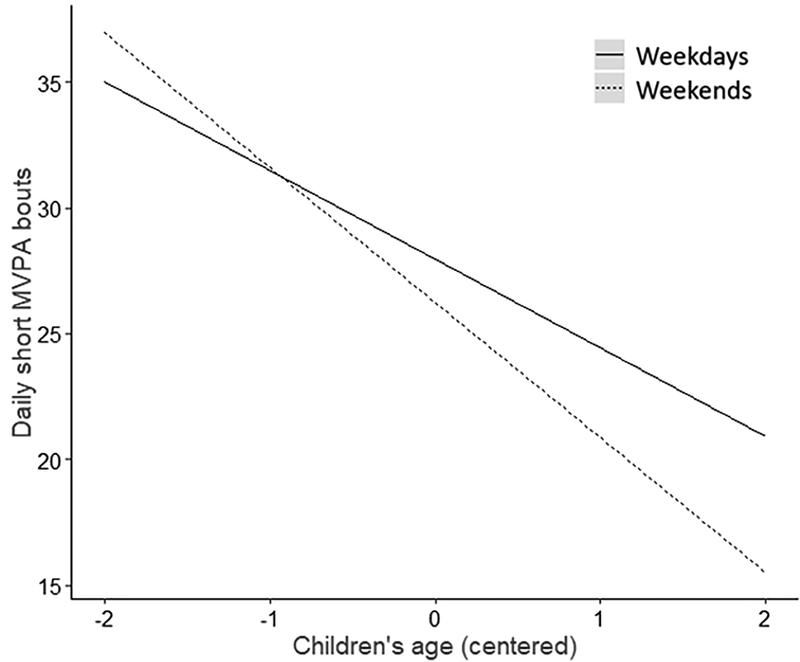

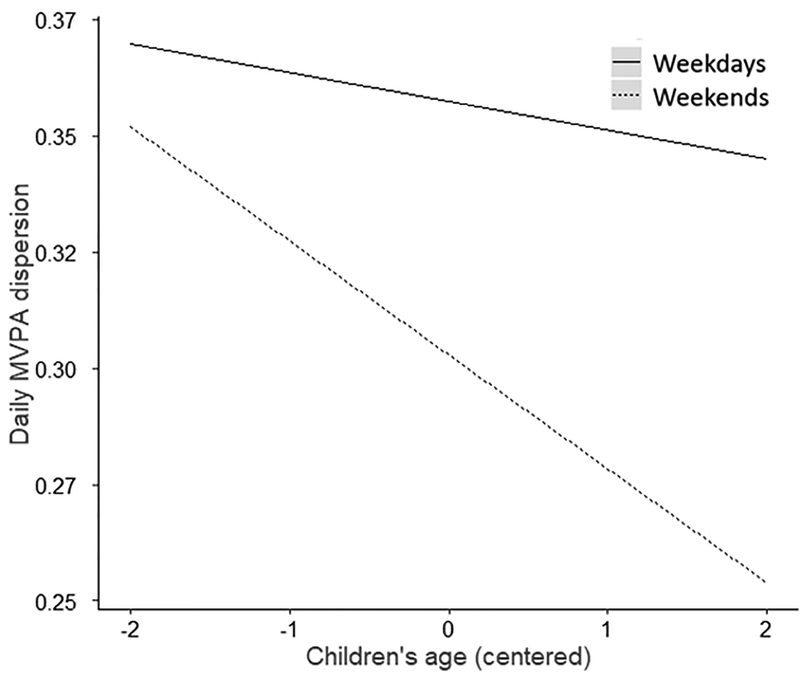

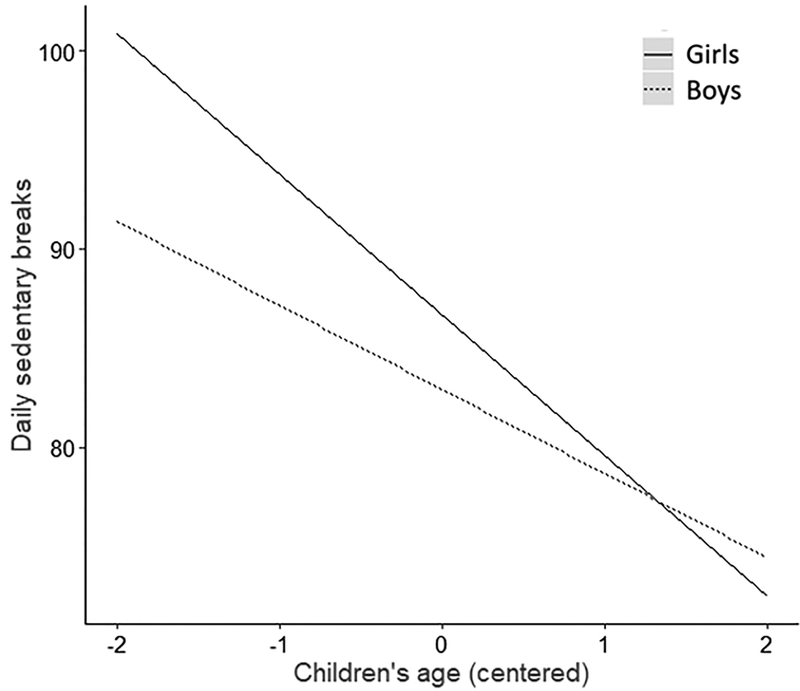

Random intercept multilevel linear regression models showed that age-related decreases in the number of short MVPA bouts per were steeper for girls vs. boys (b= −1.28, 95% CI −1.93 to −0.64; p<.01) and on weekend days vs. weekdays (b= −1.82, 95% CI −2.36 to −1.29; p<.01). The evenness of the temporal dispersion of MVPA across the day increased more on weekend days vs. weekdays as children got older (b= −0.02, 95% CI −0.02 to −0.01; p<.01). Girls had steeper age-related decreases in the number of sedentary breaks per day (b= −2.89, 95% CI −3.97 to −1.73; p<.01) and the evenness of the temporal dispersion of sedentary behavior across the day (b= <0.01, 95% CI <0.01 to 0.01; p<.01) than boys. Changes in sedentary behavior metrics did not differ between weekend days vs. weekdays.

Conclusion:

Strategies to protect against declines in short physical activity bouts and promote sedentary breaks, especially among girls and on weekend days, could reduce cardiometabolic risks.

Keywords: sex, weekend, Actigraph, bouts, breaks, Gini index, dispersion

Introduction

Low levels of physical activity and high levels of sedentary time during childhood are modifiable health behaviors that have been implicated in elevated lifelong risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (1–3). Most epidemiological studies to date examine total time spent in or total volume of activity (e.g., minutes per day) across various intensities (e.g., sedentary, light, moderate, vigorous) in relation to health outcomes and disease risk. However, emerging evidence from clinical and experimental studies shows that features of the way in which physical activity and sedentary behavior bouts and breaks are patterned across the day (e.g., length, number, and temporal dispersion) predict acute and long-term health outcomes in children (4–7). These associations exist even after controlling for the effects of total time spent in (or volume) of behavior. Whereas previous reliance of self-report instruments limited the assessment of daily physical activity and sedentary behavior pattern metrics, advancements in accelerometer technologies have enabled the measurement of novel behavior pattern metrics in recent years (8).

Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that total time spent in (or volume) of physical activity and sedentary behavior change across childhood and adolescence. Research in this area generally shows that average daily physical activity decreases (9, 10), and average daily sedentary time increases (9–12) as children get older. To date, only limited research has examined patterning and accumulation of daily physical activity and sedentary behavior bouts and breaks (i.e., length, number, and temporal distribution) in children (13, 14). Furthermore, no studies to date have investigated factors associated with longitudinal changes in physical activity and sedentary behavior pattern metrics such as sex, and whether these changes differ on weekend days versus weekdays.

Thus, the primary objective of this study was to quantify changes in objectively-measured day-level physical activity and sedentary behavior pattern metrics (i.e., length, number, and distribution of bouts and breaks) across three years of middle childhood (ages 8–12 years at baseline) using a longitudinal study design. Secondary objectives were to determine whether child sex was associated with longitudinal changes in physical activity and sedentary behavior pattern metrics, and whether longitudinal changes in these pattern metrics differed on weekend days as compared to weekdays.

Methods

Design, Recruitment, Participants

Data came from the Mothers’ and Their Children’s Health (MATCH) study, which is a longitudinal investigation of stress, parenting factors, and obesity in mothers and children. A total of six assessments were conducted at approximately 6-month intervals (i.e.: baseline, 6-months, 12-months, 18-months, 24 months, 30-months). Ethnically-diverse children (ages 8–12 years) were recruited from public elementary schools and after-school programs in the greater Los Angeles metropolitan area between August 2014 and March 2016. Children learned about the study through informational flyers and in-person recruitment events. Inclusion criteria were: 1) child is in the 3rd–6th grade upon enrollment, 2) ≥ 50% of child’s custody resides with the mother, and 3) child is able to read English. Exclusion criteria were: 1) child is currently taking medications for thyroid function or psychological conditions such as mood disorders or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), 2) child has health issues that limit physical activity, 3) enrolled in special education programs, 4) child is currently using oral or inhalant corticosteroids for asthma, 5) mother is pregnant, 6) child is classified as underweight by a Body Mass Index (BMI) percentile < 5% adjusted for sex and age, and 7) mother works more than two weekday evenings (between the hours of 5–9pm) per week or more than 8 hours on any weekend day.

Procedures and Consent

At each assessment time point, children attended an in-person data collection session at a local school or community center where they completed a paper questionnaire, underwent anthropometric assessments, and received an accelerometer that they were asked to wear for the next seven days (excluding during any water-based activities and sleep). Children were given $100 for completing these procedures. Parental consent was obtained, and all participants provided written assent. The University of Southern California Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Measures

Objective measurement of physical activity and sedentary behavior.

Physical activity and sedentary behavior were measured using a waist-worn Actigraph, Inc. GT3X model accelerometer at a frequency of 30hz with a 30-sec epoch. Periods of non-wear (> 60 continuous minutes of zero activity counts) and non-valid days (<10 hours of wear) were eliminated. Data from days with ≥18 hours valid wear time were visually checked for periods of erroneous device wear during sleep, and these periods were coded as non-wear. A custom-built R program applied cut-points for time spent in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and sedentary behavior were using age-specific thresholds (adjusted for 30-sec epochs) for children based on national data (15, 16) and generated from the Freedson prediction equation equivalent to 4 Metabolic Equivalents (METs) (16–18). Sedentary behavior was defined as activity <100 counts per minute (19, 20).

A total of eight day-level physical activity and sedentary behavior pattern metrics describing the length, number, and temporal distribution of bouts and breaks were generated. The end of a bout of MVPA was defined as activity levels falling below 4 METs for any 30-sec epoch. A break in a sedentary bout was defined as accelerometer-derived activity exceeding 100 counts per minute for at least a minute. Day-level accelerometer-derived physical activity pattern metrics included: 1) total time spent in MVPA, 2) number of short bouts (<10 min) of MVPA, 3) number of long bouts (≥20 min) of MVPA based on a threshold previously used in children (21), and 4) a Gini index for MVPA using the R package “reldist” (22). Originally utilized in the field of economics to describe the distribution or dispersion of wealth (23), the Gini index is increasingly being applied to physical activity research (24, 25). The Gini index ranges from zero to one, with smaller values indicating that behavior was accumulated more evenly (i.e., more dispersed) across the chronological time of the day (23). Day-level accelerometer-derived sedentary behavior pattern metrics included: 1) total time spent in sedentary behavior, 2) number of breaks in sedentary bouts, 3) number of long sedentary bouts (≥60 min), and 4) a Gini index for sedentary behavior to describe the distribution of sedentary behavior across the day, with smaller (closer to 0) values indicating that sedentary behavior was accumulated more evenly (i.e., more dispersed) throughout the chronological time of the day.

Anthropometric assessments.

Weight and height were measured in duplicate using an electronically calibrated digital scale (Tanita WB-110A) and professional stadiometer (Seca 213 Portable Stadiometer) to the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.1 cm, respectively. Body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) and age and sex-specific BMI percentiles were determined using the SAS program and growth charts (ages 0 to <20 years) provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (26).

Demographic factors.

Mothers completed paper questionnaires reporting on their child’s race and ethnicity, and annual household income. Children self-reported their birthdate and sex. Age in years (to the second decimal place) was calculated based on the time elapsed between the child’s birthdate and the date of each of the assessments.

Statistical Analyses

To account for the interdependency of the nested data structure in the current study (Level 1-days nested within Level 2-children), random intercept multilevel linear regression models were used for the prediction of continuous daily behavior metric outcomes. Linear longitudinal trends in children’s physical activity and sedentary behavior pattern metrics were tested as a function of children’s age at each assessment. Separate models were run for each of the different behavior pattern metric outcomes. Each model controlled for children’s age at the first assessment, children’s sex (girl=1), whether the day was a weekend versus weekday (weekend =1), the number of valid accelerometer wear days across all available assessments, average daily valid accelerometer wear time (in minutes) at each valid day, averaged child BMI z-score across all available assessments, averaged household income quartile across all available assessments, and child ethnicity (Hispanic versus non-Hispanic; Hispanic=1). To adjust for the positive skew of total time spent in MVPA (skewness=1.49, Kurtosis=5.45), this outcome was log-transformed (skewness= −0.93, Kurtosis=1.44). Due to the large proportion of days with no long MVPA bouts (≥20 min; 61% of days) and long sedentary bouts (≥60 min; 53% of days), random intercept multilevel logistic regression models (generalized multilevel model) were applied to analyze those outcomes (1 was coded for days with one or more long bout and 0 was coded for days with no long bouts). Two-way interactions (sex by age, weekend by age, sex by weekend) were added to the above models test moderation effects. Data were analyzed using R 3.2.2 program (R Core Team, 2018) with the lme4 package for generalized multilevel modeling (27).

Results

Data Availability and Characteristics of the Study Sample

Of the 464 families initially expressing interest in the study, 132 families could not be reached by phone for eligibility screening, and 22 families declined to be screened for eligibility. Of the 310 families screened, 62 families did not meet eligibility criteria. Of the remaining 248 families who met eligibility criteria, 46 families either did not attend their initial enrollment session or were no longer interested in the study. A total of 202 children initially enrolled in the study. Given that only a very small number of children reached age 14 by the end of the sixth assessment, days where children were 14 years old were dropped from the analyses. In total, 169 children provided at least one valid accelerometry wear day during at least two of the six assessments. This minimum level of protocol compliance was deemed necessary for statistical analyses. Welch’s robust mean test suggested that there were no significant differences in demographic factors between the children included and excluded in the analysis (ps range=0.16–0.72) (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1: differences in means for demographic characteristics of included and excluded children).

Children in the current analysis (54.4% female; 55.6% Hispanic) provided a total of 4,282 valid days of accelerometry data across six assessments. As seen in Table 1, the daily accelerometry data covered ages ranging from 8.31 to 13.9 years old across six assessments. Each child provided an average of 4.95 (range=1.50–7.00, SD=1.26) valid accelerometer wear days per assessment and an average of 25.39 (range=3–42, SD=9.41) valid accelerometer wear days across all assessments. For each valid day, children had an average of approximately 13.6 hours of valid accelerometer wear.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for all predictors included in data analysis (N =169 children)

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first assessment (years) | 10.16 | 0.87 | 8.31 | 12.49 |

| Age by assessment (years) | 11.18 | 1.19 | 8.31 | 13.9 |

| Valid accelerometer wear (days per child)a | 25.39 | 9.41 | 3 | 42 |

| Valid accelerometer wear (minutes per day)b | 818.96 | 52.06 | 669 | 971 |

| Body Mass Index (z-score) | 0.52 | 1.10 | −2.46 | 2.56 |

| Annual household Income quartilec | 2.50 | 1.07 | 1 | 4 |

| Frequency (1) | % | Min | Max | |

| Girl (1) vs boy (0) | 92 | 54.4 | 0 | 1 |

| Weekend day (1) vs weekday (0) | 1096 | 25.6 | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic (1) vs non-Hispanic (0) | 94 | 55.6 | 0 | 1 |

A valid accelerometer wear day consisted of at least 10 hours of valid accelerometer wear time.

Non-valid accelerometer wear time consisted of zero activity counts for at least consecutive 60 minutes.

The annual household income quartile in USD was stratified as: 0–35,000 (1); 35,001–75,000 (2); 75,001–105,000 (3); 105,001 and above (4)

Longitudinal Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Pattern Metrics

Linear longitudinal trends in children’s day-level physical activity and sedentary behavior pattern metrics were observed (see Table 2). Overall, children’s total time spent in MVPA per day (b= −0.20, 95% CI −0.22 to −0.18; p<.001), number of daily short (< 10 min) MVPA bouts (b= −4.01, 95% CI −4.33 to −3.67; p<.001), and number of sedentary breaks per day (b= −5.79, 95% CI −6.44 to −5.13; p<.001) significantly decreased from age 8 to age 13. MVPA decreased about 30 min per day during this period. The number of short MVPA bouts per day declined by about half, and the number of breaks in sedentary behavior declined by about a fourth. In contrast, children’s total time spent in sedentary behavior per day significantly increased (by about 2 hours per day) between age 8 and 13 years (b= 22.95, 95% CI 19.62 to 26.28; p<.001). Overall, children’s daily proportions of long (≥20 min) MVPA bouts decreased (from 2.1% to 1.6%, OR= 0.94, 95% CI 0.93 to 0.95; p<.001), and daily proportions of long (≥60 min) sedentary bouts increased (from 0.6% to 2.3%, OR= 1.06, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.07; p<.001). Children’s MVPA became more evenly dispersed (b= −0.011, 95% CI −0.015 to −0.007; p<.001), and sedentary behavior became less evenly dispersed (b= 0.008, CI 0.006 to 0.009; p<.001) across the day as children got older.

Table 2.

Day-level descriptive statistics for children’s day-level physical activity and sedentary behavior pattern metrics at each age (N=169)

| Age ≤ 8 to <9 | Age ≤9 to <10 | Age ≤10 to <11 | Age ≤11 to <12 | Age ≤12 to <13 | Age ≤13 to <14 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of days | 121 | 628 | 1160 | 1246 | 825 | 276 | ||

| Total MVPA (min) | Boys | M (SD) |

82.45 (33.35) |

73.48 (38.89) |

59.74 (33.95) |

59.25 (35.94) |

50.47 (32.31) |

51.44 (43.63) |

| Girls | M (SD) |

69.24 (30.94) |

54.71 (28.33) |

44.79 (26.01) |

40.88 (31.98) |

32.63 (22.36) |

30.93 (21.76) |

|

| Number of short (<10 min) MVPA bouts |

Boys | M (SD) |

34.97 (12.48) |

33.05 (12.09) |

27.99 (10.56) |

26.97 (10.41) |

21.81 (10.18) |

21.18 (10.50) |

| Girls | M (SD) |

46.48 (15.73) |

35.43 (11.79) |

30.24 (11.39) |

26.34 (11.19) |

21.94 (10.02) |

19.20 (9.05) |

|

| Number of long (≥20 mins) MVPA boutsb | Boys | M (SD) |

1.19 (1.20) |

1.12 (1.23) |

0.89 (1.13) |

0.85 (1.05) |

0.72 (0.96) |

0.80 (1.30) |

| Girls | M (SD) |

0.67 (0.79) |

0.56 (0.88) |

0.40 (0.73) |

0.41 (1.04) |

0.27 (0.63) |

0.28 (0.53) |

|

| MVPA dispersiona |

Boys | M (SD) |

0.43 (0.08) |

0.40 (0.10) |

0.38 (0.12) |

0.38 (0.12) |

0.38 (0.14) |

0.36 (0.14) |

| Girls | M (SD) |

0.32 (0.07) |

0.33 (0.09) |

0.31 (0.10) |

0.31 (0.12) |

0.30 (0.13) |

0.31 (0.14) |

|

| Total sedentary behavior (min) |

Boys | M (SD) |

429.85 (84.53) |

462.79 (107.67) |

497.13 (124.36) |

487.72 (104.47) |

518.17 (111.73) |

508.68 (103.32) |

| Girls | M (SD) |

413.15 (95.12) |

459.97 (107.82) |

488.02 (108.54) |

512.45 (101.86) |

551.41 (109.86) |

568.52 (94.12) |

|

| Number of sedentary breaks |

Boys | M (SD) |

85.89 (20.86) |

89.64 (20.89) |

86.53 (20.63) |

83.63 (19.17) |

77.09 (21.16) |

75.81 (19.03) |

| Girls | M (SD) |

105.22 (23.19) |

96.80 (20.40) |

89.74 (21.27) |

84.12 (23.42) |

77.28 (22.38) |

71.74 (24.26) |

|

| Number of long (≥60 min) sedentary boutsb |

Boys | M (SD) |

0.57 (0.74) |

0.57 (0.85) |

0.67 (0.98) |

0.68 (0.89) |

0.82 (0.92) |

0.70 (0.93) |

| Girls | M (SD) |

0.39 (0.77) |

0.50 (0.79) |

0.61 (0.87) |

0.74 (0.94) |

0.88 (1.11) |

1.20 (1.32) |

|

| Sedentary behavior dispersiona |

Boys | M (SD) |

0.59 (0.06) |

0.58 (0.05) |

0.59 (0.05) |

0.60 (0.05) |

0.60 (0.05) |

0.61 (0.05) |

| Girls | M (SD) |

0.56 (0.06) |

0.58 (0.05) |

0.59 (0.05) |

0.60 (0.05) |

0.61 (0.05) |

0.63 (0.04) |

|

M: mean; SD: standard deviation. MVPA: moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Data are for valid accelerometer wear days (≥10 hours of valid accelerometer wear time).

Dispersion measured by the Gini index: where a lower Gini value indicates more even distribution across the day.

Counts of long MVPA and long sedentary bouts allow for a 2-min threshold of non-MVPA or non-sedentary time.

Factors Associated with Longitudinal Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Pattern Metrics

Rates of longitudinal change in many of the physical activity pattern metrics differed by child sex and on weekend days versus weekdays (see Table 3). The interactions between child age at each assessment and sex were significant for predicting total time spent in MVPA per day and number of short (<10 min) MVPA bouts across the day. As girls got older, they had a greater decrease in total time spent in MVPA per day and the number of short MVPA bouts per day (see Figure 1a) than boys. Furthermore, the interactions between child age at each assessment and weekend were significant for predicting the total time spent in MVPA per day, number of short MVPA bouts per day, and dispersion of MVPA bouts across the day. Age-related decreases in total time spent in MVPA per day and number of short MVPA bouts per day (see Figure 1b) were steeper on weekend days as compared to weekdays. Also, as children got older, increases in the evenness of the temporal dispersion of MVPA across the day were larger on weekend days as compared to weekdays (see Figure 1c). Finally, weekend day compared to weekday differences in number of short MVPA bouts differed between boys and girls. Weekdays generally accumulated more daily short MVPA bouts than weekend days, but the differences were larger for girls compared to boys.

Table 3.

Multilevel linear and logistic regression model coefficients predicting children’s day-level physical activity and sedentary behavior pattern metrics

| Total MVPA (min)a | Number of short (< 10 min) MVPA bouts | Long (≥ 20 min) MVPA boutsb | MVPA Dispersionc | Total sedentary behavior (min) | Number of sedentary breaks | Long (≥ 60 min) sedentary boutsb | Sedentary behavior dispersionc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.10 | |

| Fixed Effects | Intercept (SD) [95% CI] |

3.72** (0.09) [3.53; 3.90] |

28.69** (1.38) [25.98; 31.39] |

−0.89** (0.25) [−1.38; −0.39] |

0.34** (0.01) [0.32; 0.36] |

510.85** (11.31) [488.68; 533.02] |

83.21** (2.35) [78.60; 87.82] |

−0.06 (0.18) [−0.41; 0.29] |

0.59** (<0.01) [0.58; 0.60] |

| Age (SD) [95% CI] |

−0.17** (0.01) [−0.20; −0.15] |

−4.13** (0.23) [−4.59; −3.67] |

−0.26** (0.06) [−0.37; −0.15] |

<−0.01* (<0.01) [−0.01; 0.01] |

26.79** (1.70) [23.46; 30.11] |

−7.26** (0.41) [−8.06; −6.49] |

0.30** (0.05) [0.20; 0.39] |

0.01** (<0.01) [0.01; 0.02] |

|

| Sex (SD) [95% CI] |

0.32** (0.06) [0.21; 0.43] |

−1.70* (0.84) [−3.35; −0.05] |

1.26** (0.15) [0.96; 1.56] |

0.07** (0.01) [0.05; 0.09] |

−14.26 (6.84) [−27.76; −0.76] |

−3.48 (1.43) [−6.30; −0.67] |

0.02 (0.11) [−0.19; 0.24] |

<0.01 (<0.01) [−0.01;0.01] |

|

| Weekend (SD) [95% CI] |

−0.40** (0.03) [−0.46; −0.35] |

−2.45** (0.45) [−3.34; −1.57] |

−0.59** (0.13) [−0.84; −0.34] |

−0.05** (0.01) [−0.06; −0.04] |

2.71 (3.24) [−3.64; 9.07] |

1.15 (0.79) [−0.39; 2.70] |

0.20* (0.10) [0.01; 0.40] |

<−0.01 (<0.01) [−0.05; 0.05] |

|

| Sex by age interaction (SD) [95% CI] |

0.04* (0.02) [0.01; 0.08] |

1.28** (0.33) [0.64; 1.93] |

−0.06 (0.08) [−0.21; 0.10] |

−0.01 (<0.01) [−0.01; <0.01] |

−8.52** (2.39) [−13.19; −3.84] |

2.89** (0.57) [1.73; 3.97] |

−0.11 (0.07) [−0.24; 0.02] |

<−0.01** (<0.01) [−0.01; 0.01] |

|

| Weekend by age interaction (SD) [95% CI] |

−0.17** (0.02) [−0.20; −0.13] |

−1.82** (0.27) [−2.36; −1.29] |

−0.10 (0.07) [−0.24; 0.04] |

−0.02** (<0.01) [−0.02; −0.01] |

2.62 (1.95) [−1.20; 6.44] |

0.66 (0.47) [−0.26; 1.59] |

0.04 (0.06) [−0.08; 0.16] |

<−0.01 (<0.01) [−0.01; 0.01] |

|

| Sex by weekend interaction (SD) [95% CI] |

0.01 (0.04) [−0.07; 0.10] |

1.58* (0.67) [0.28; 2.89] |

−0.24 (0.17) [−0.58; 0.09] |

<−0.01 (0.01) [−1.79; 0.01] |

8.68 (4.77) [−0.67; 18.02] |

−1.07 (1.16) [−3.34; 1.20] |

0.08 (0.15) [−0.21; 0.38] |

<−0.01 (<0.01) [−0.01; <0.01] |

|

| Random Effects | Intercept SD | 0.34 | 4.87 | 0.82 | 0.05 | 40.84 | 8.28 | 0.51 | 0.02 |

| Residual SD | 0.58 | 9.31 | - | 0.10 | 66.54 | 16.18 | - | 0.05 |

SD: standard deviation. CI: confidence interval. ICC: Intraclass correlation coefficient. MVPA: moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Age: at each assessment. Sex: 1= girls, 0 = boys. Weekend: 1= weekend day, 0= weekday. Outcome variables are listed in the first row of the table. Data are for valid accelerometer wear days (≥10 hours of valid accelerometer wear time). Models controlled for valid daily accelerometer wear time, number of valid accelerometer wear days, averaged Body Mass Index (BMI) z-score, age at first assessment, averaged household income quartile, Hispanic or non-Hispanic.

The outcome values were log-transformed.

Multilevel logistic regression models predicted the likelihood of ≥1 long bout(s) (1) vs no long bouts (0), and the coefficients are in log odds.

Dispersion measured by the Gini index: where a lower Gini value indicates more even distribution across the day.

p <.05,

p <.01.

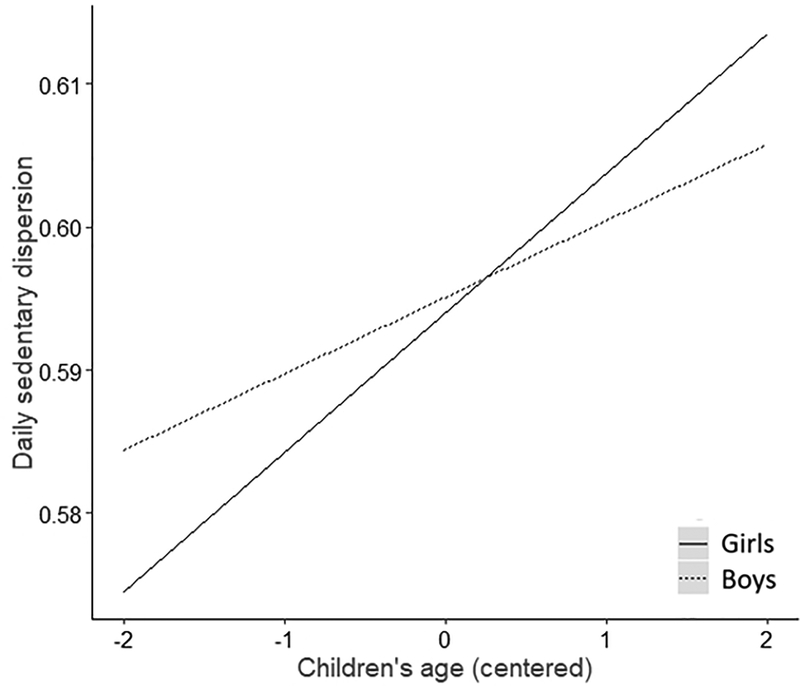

Figure 1: Panel Plots of Interactions Predicting Daily Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Pattern Metrics.

1a. Interaction plot of age and sex interaction predicting daily number of short MVPA bouts

1b. Interaction plot of age and weekend interaction predicting daily number of short MVPA bouts

1c. Interaction plot of age and weekend interaction predicting daily MVPA temporal dispersion (Gini index)

1d. Interaction plot of age and sex interaction predicting daily number of sedentary behavior breaks

1e. Interaction plot of age and sex interaction predicting daily sedentary behavior temporal dispersion (Gini index)

Table 3 shows that rates of longitudinal change in many of the sedentary behavior pattern metrics differed by child sex. The interactions between child age at each assessment and sex were significant for predicting the total time spent in sedentary behavior per day, number of breaks in sedentary behavior per day, and temporal dispersion of sedentary behavior across the day. As boys got older, they had a greater increase in total time spent in sedentary behavior per day than girls. However, as girls got older, they had a greater decrease in the number of sedentary breaks per day (see Figure 1d) and the evenness of the temporal dispersion of sedentary behavior across the day (see Figure 1e) than boys. Rates of longitudinal change the sedentary behavior pattern metrics did not differ by weekend day versus weekday.

Discussion

Longitudinal changes in children’s daily patterning and accumulation of physical activity and sedentary behaviors were observed. The number of daily short and long physical activity bouts decreased, and physical activity became more evenly dispersed across the day as children got older. In contrast, the number of daily sedentary breaks decreased, the number of long sedentary bouts increased, and sedentary behavior became less evenly dispersed across the day. However, examination of sex and day of the week differences in these pattern metrics revealed unique vulnerabilities that could be overlooked when examining only total time spent in activity across various intensity levels (e.g., min/day of sedentary, light, moderate, vigorous).

In general, most of the physical activity pattern metrics (e.g., length of bouts, total volume) were lower among girls as compared to boys, which is consistent with national data (28, 29). An important exception to this pattern of findings was that girls performed a greater number of short (<10 min) MVPA bouts per day than boys─ suggesting that girls’ bouts of physical activity may be more intermittent, unstructured, and sporadic. However, as girls got older, they had steeper declines in the number of short (but not intermediate [10–19 min] [see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2: model coefficients predicting children’s day-level intermediate length MVPA bouts (≥10 minutes to > 20 minutes)]) or long [≥20 min]) MVPA bouts per day than boys. Given recent updates to the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans that underscore the health benefits of accumulated physical activity regardless of the bout duration (30), implementing targeted strategies to protect against declines in short physical activity bouts among girls could yield positive health outcomes. These strategies could include the development of sex-specific products or programs such as active video and non-video games designed for girls, recess-based activity clubs for girls, active homework assignments, or running clubs (31).

Findings from the current study also highlight the vulnerability of weekend time to declining physical activity levels across childhood. Age-related decreases in the number of short (<10 min) (but not intermediate [10–19 min] [see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2: model coefficients predicting children’s day-level intermediate length MVPA bouts (≥10 minutes to > 20 minutes)] or long [≥20 min]) MVPA bouts per day were steeper on the weekend days as compared to the weekdays. Younger children participate in more unorganized active free play (32), which may be more characterized by short and sporadic activity bouts. Given that unorganized active free play is more likely to occur on weekend days when children have more unstructured leisure time (33), waning interest in unorganized active free play among older children may lead to a decline in short activity bouts on weekend days. Also, results indicated that as children got older, their physical activity tended to be i.e., more evenly dispersed across the day on weekend days compared to on weekdays. This trend may reflect declining interest in weekend-based organized sports tournaments or competitions (e.g., martial arts, dance) as children get older (34). The consistent trend of declining physical activity across multiple pattern metrics on weekend days highlights the need for increased resourcing and opportunities for structured weekend physical activity and organized sport for youth. It also underscores the importance of weekday school-based activities such as physical education, recess, and walking to school in protecting against decreasing physical activity levels during childhood (35).

Longitudinal changes were seen for the sedentary behavior pattern metrics that are consistent with research showing that as children get older, they spend more time in sedentary types of activities (e.g., TV, video games, homework) and break up these sedentary behaviors less often (9–12, 36). The school day did not appear to be protective against age-related increases in the proportion of long sedentary bouts, as rates of change in this outcome did not differ between weekend days and weekdays. The beneficial effect of the school day on limiting younger children’s sedentary behavior may be mitigated by longer school class periods and more sedentary-oriented classroom activities in the higher grades.

The current study found evidence for sex differences in the rates of longitudinal change in sedentary behavior pattern metrics. As girls got older, they had greater decreases in the number of sedentary behavior breaks and their sedentary behaviors became less dispersed across the day compared to boys. This finding suggests that sedentary behaviors become more clustered at certain times of the day as girls get older, possibly due to greater focused time spent in homework sessions, social media, or sedentary socializing than boys (37–39). Targeted approaches to breaking up sedentary behaviors among girls as they get older such as standing desks for homework, planned homework breaks, or the encouragement of face-to-face active socializing may be needed.

Strengths of the current analysis include the longitudinal design with six assessment points across three years, use of an objective measure of physical activity and sedentary behavior, examination of novel behavior patterns metrics, and consideration of day-level data. One of the limitations was missing data resulting from accelerometer device non-wear. Statistical models that controlled for the number of valid accelerometer wear days (>10 hours) and the valid daily accelerometer wear time (in minutes) at each assessment may not fully eliminate underestimation of sedentary time due to device non-wear (40, 41). Furthermore, the representativeness of the study sample was limited by the regional focus in Southern California, which has a large Hispanic population. Results may not generalize to children of different racial/ethnic backgrounds or to other regions of the U.S.

Overall, this analysis found that examining longitudinal changes in timing and patterning of how physical activity and sedentary behaviors are accumulated may offer unique insights into clinical and policy intervention strategies that would not necessarily be evident when looking only at total time spent in these behaviors. Sex and weekend-specific approaches to encourage short activity bouts and breaks in sedentary behavior, and to reduce clustering of sedentary behavior in children as they get older could reduce cardiometabolic and other health risks.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health grants R01HL119255, R01HL121330, and T32CA009492.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Genevieve F. Dunton received consulting payments from the Dairy Council of California and the National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity Research. Genevieve F. Dunton received travel funding from the National Physical Activity Plan Alliance and the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. These organizations had no role in the design/conduct of the study, collection/analysis/interpretation of the data, or preparation/review/approval of the manuscript. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM. The results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation.

References:

- 1.Strong WB, Malina RM, Blimkie CJ, Daniels SR, Dishman RK, Gutin B, et al. Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. The Journal of pediatrics. 2005;146(6):732–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Kho ME, Saunders TJ, Larouche R, Colley RC, et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2011;8(1):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The lancet. 2013;380(9859):2224–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey DP, Charman SJ, Ploetz T, Savory LA, Kerr CJ. Associations between prolonged sedentary time and breaks in sedentary time with cardiometabolic risk in 10–14-year-old children: The HAPPY study. Journal of sports sciences. 2017;35(22):2164–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saunders TJ, Tremblay MS, Mathieu ME, Henderson M, O’Loughlin J, Tremblay A, et al. Associations of sedentary behavior, sedentary bouts and breaks in sedentary time with cardiometabolic risk in children with a family history of obesity. PloS one. 2013;8(11):e79143 Epub 2013/11/28. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belcher BR, Berrigan D, Papachristopoulou A, Brady SM, Bernstein SB, Brychta RJ, et al. Effects of Interrupting Children’s Sedentary Behaviors With Activity on Metabolic Function: A Randomized Trial. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2015;100(10):3735–43. Epub 2015/08/28. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broadney MM, Belcher BR, Berrigan DA, Brychta RJ, Tigner IL Jr., Shareef F, et al. Effects of Interrupting Sedentary Behavior With Short Bouts of Moderate Physical Activity on Glucose Tolerance in Children With Overweight and Obesity: A Randomized, Crossover Trial. Diabetes care. 2018. Epub 2018/08/08. doi: 10.2337/dc18-0774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keadle SK, Sampson J, Li H, Lyden K, Matthews CE, Carroll R. An evaluation of accelerometer-derived metrics to assess daily behavioral patterns. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2017;49(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalene KE, Anderssen SA, Andersen L, Steene-Johannessen J, Ekelund U, Hansen BH, et al. Secular and longitudinal physical activity changes in population-based samples of children and adolescents. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2018;28(1):161–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harding SK, Page AS, Falconer C, Cooper AR. Longitudinal changes in sedentary time and physical activity during adolescence. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2015;12:44 Epub 2015/04/19. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0204-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brodersen NH, Steptoe A, Boniface DR, Wardle J. Trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviour in adolescence: ethnic and socioeconomic differences. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2007;41(3):140–4. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.031138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Treuth MS, Baggett CD, Pratt CA, Going SB, Elder JP, Charneco EY, et al. A longitudinal study of sedentary behavior and overweight in adolescent girls. Obesity. 2009;17(5):1003–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janssen X, Mann KD, Basterfield L, Parkinson KN, Pearce MS, Reilly JK, et al. Development of sedentary behavior across childhood and adolescence: longitudinal analysis of the Gateshead Millennium Study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2016;13(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell JA, Pate RR, Dowda M, Mattocks C, Riddoch C, Ness AR, et al. A Prospective Study of Sedentary Behavior in a Large Cohort of Youth. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2012;44(6):1081–7. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182446c65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2008;40(1):181–8. Epub 2007/12/20. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belcher BR, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Emken BA, Chou CP, Spruijt-Metz D. Physical activity in US youth: effect of race/ethnicity, age, gender, and weight status. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2010;42(12):2211–21. Epub 2010/11/19. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e1fba9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freedson P, Pober D, Janz KF. Calibration of accelerometer output for children. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2005;37(11 Suppl):S523–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1998;30(5):777–81. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Treuth MS, Schmitz K, Catellier DJ, McMurray RG, Murray DM, Almeida MJ, et al. Defining accelerometer thresholds for activity intensities in adolescent girls. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2004;36(7):1259–66. Epub 2004/07/06. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, Cerin E, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, et al. Breaks in sedentary time: beneficial associations with metabolic risk. Diabetes care. 2008;31(4):661–6. Epub 2008/02/07. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trost SG, Kerr L, Ward DS, Pate RR. Physical activity and determinants of physical activity in obese and non-obese children. International journal of obesity. 2001;25(6):822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chastin S, Granat M. Methods for objective measure, quantification and analysis of sedentary behaviour and inactivity. Gait & posture. 2010;31(1):82–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gastwirth JL. The estimation of the Lorenz curve and Gini index. The review of economics and statistics. 1972:306–16. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellis K, Kerr J, Godbole S, Lanckriet G, Wing D, Marshall S. A random forest classifier for the prediction of energy expenditure and type of physical activity from wrist and hip accelerometers. Physiological measurement. 2014;35(11):2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lord S, Chastin SFM, McInnes L, Little L, Briggs P, Rochester L. Exploring patterns of daily physical and sedentary behaviour in community-dwelling older adults. Age and ageing. 2011;40(2):205–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prevention CfDCa. A SAS program for the 2000 CDC Growth Charts (ages 0 to <20 years). . Atlanta, GA:: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S, Christensen RHB, Singmann H, et al. Package ‘lme4’. Convergence. 2015;12(1). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belcher BR, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Emken BA, Chou C-P, Spuijt-Metz D. Physical Activity in US Youth: Impact of Race/Ethnicity, Age, Gender, & Weight Status. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2010;42(12):2211–21. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e1fba9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2008;40(1):181–8. Epub 2007/12/20. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. Jama. 2018;320(19):2020–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robbins LB, Gretebeck KA, Kazanis AS, Pender NJ. Girls on the move program to increase physical activity participation. Nursing research. 2006;55(3):206–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson SE, Economos CD, Must A. Active play and screen time in US children aged 4 to 11 years in relation to sociodemographic and weight status characteristics: a nationally representative cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public health. 2008;8(1):366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brockman R, Jago R, Fox KR. The contribution of active play to the physical activity of primary school children. Preventive medicine. 2010;51(2):144–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crane J, Temple V. A systematic review of dropout from organized sport among children and youth. European physical education review. 2015;21(1):114–31. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brazendale K, Beets MW, Weaver RG, Pate RR, Turner-McGrievy GM, Kaczynski AT, et al. Understanding differences between summer vs. school obesogenic behaviors of children: the structured days hypothesis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2017;14(1):100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swaminathan S, Selvam S, Thomas T, Kurpad AV, Vaz M. Longitudinal trends in physical activity patterns in selected urban south Indian school children. The Indian journal of medical research. 2011;134:174–80. Epub 2011/09/14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atkin AJ, Gorely T, Biddle SJ, Marshall SJ, Cameron N. Critical hours: physical activity and sedentary behavior of adolescents after school. Pediatric Exercise Science. 2008;20(4):446–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bauer KW, Friend S, Graham DJ, Neumark-Sztainer D. Beyond screen time: assessing recreational sedentary behavior among adolescent girls. Journal of obesity. 2011;2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liao Y, Intille S, Wolch J, Pentz MA, Dunton GF. Understanding the physical and social contexts of children’s nonschool sedentary behavior: an ecological momentary assessment study. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11(3):588–95. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2011-0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janssen X, Basterfield L, Parkinson KN, Pearce MS, Reilly JK, Adamson AJ, et al. Objective measurement of sedentary behavior: impact of non-wear time rules on changes in sedentary time. BMC public health. 2015;15(1):504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borghese M, Borgundvaag E, McIsaac MA, Janssen I. Imputing accelerometer nonwear time in children influences estimates of sedentary time and its associations with cardiometabolic risk. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2019;16(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Of the 464 families initially expressing interest in the study, 132 families could not be reached by phone for eligibility screening, and 22 families declined to be screened for eligibility. Of the 310 families screened, 62 families did not meet eligibility criteria. Of the remaining 248 families who met eligibility criteria, 46 families either did not attend their initial enrollment session or were no longer interested in the study. A total of 202 children initially enrolled in the study. Given that only a very small number of children reached age 14 by the end of the sixth assessment, days where children were 14 years old were dropped from the analyses. In total, 169 children provided at least one valid accelerometry wear day during at least two of the six assessments. This minimum level of protocol compliance was deemed necessary for statistical analyses. Welch’s robust mean test suggested that there were no significant differences in demographic factors between the children included and excluded in the analysis (ps range=0.16–0.72) (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1: differences in means for demographic characteristics of included and excluded children).

Children in the current analysis (54.4% female; 55.6% Hispanic) provided a total of 4,282 valid days of accelerometry data across six assessments. As seen in Table 1, the daily accelerometry data covered ages ranging from 8.31 to 13.9 years old across six assessments. Each child provided an average of 4.95 (range=1.50–7.00, SD=1.26) valid accelerometer wear days per assessment and an average of 25.39 (range=3–42, SD=9.41) valid accelerometer wear days across all assessments. For each valid day, children had an average of approximately 13.6 hours of valid accelerometer wear.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for all predictors included in data analysis (N =169 children)

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first assessment (years) | 10.16 | 0.87 | 8.31 | 12.49 |

| Age by assessment (years) | 11.18 | 1.19 | 8.31 | 13.9 |

| Valid accelerometer wear (days per child)a | 25.39 | 9.41 | 3 | 42 |

| Valid accelerometer wear (minutes per day)b | 818.96 | 52.06 | 669 | 971 |

| Body Mass Index (z-score) | 0.52 | 1.10 | −2.46 | 2.56 |

| Annual household Income quartilec | 2.50 | 1.07 | 1 | 4 |

| Frequency (1) | % | Min | Max | |

| Girl (1) vs boy (0) | 92 | 54.4 | 0 | 1 |

| Weekend day (1) vs weekday (0) | 1096 | 25.6 | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic (1) vs non-Hispanic (0) | 94 | 55.6 | 0 | 1 |

A valid accelerometer wear day consisted of at least 10 hours of valid accelerometer wear time.

Non-valid accelerometer wear time consisted of zero activity counts for at least consecutive 60 minutes.

The annual household income quartile in USD was stratified as: 0–35,000 (1); 35,001–75,000 (2); 75,001–105,000 (3); 105,001 and above (4)