Abstract

Background:

Blood transfusion in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is associated with increased morbidity, including periprosthetic joint infection (PJI). Tranexamic acid (TXA) reduces blood transfusion rates, but there is limited evidence demonstrating improved outcomes in TKA resulting from TXA administration. The objectives of this study were determining whether TXA was associated with decreased rate of PJI, decreased rate of outcomes associated with PJI, and whether there were differences in rates of adverse events.

Methods:

A multicenter cohort study comprising 23,421 TKA compared 4,423 patients receiving TXA to 18,998 patients not receiving TXA. Primary outcome was PJI within two years of TKA. Secondary outcomes included revision surgery, irrigation and debridement, transfusion, and length of stay. Adverse events included readmission, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary emboli, myocardial infarction, or stroke. Adjusted odds ratios were determined using linear mixed models controlling for age, sex, thromboembolic prophylaxis, Charlson comorbidity index, year of TKA, and surgeon.

Results:

TXA administration reduced incidence of PJI by approximately 50% (OR 0.55; p=0.03). Additionally, there was decreased incidence of revision surgery at two years (OR 0.66; p=0.02). Patients receiving TXA had reductions in transfusion rate (OR 0.15; p<0.0001) and length of stay (p<0.0001). There was no difference in the rate of pulmonary emboli (OR 1.20, p=0.39), myocardial infarction (OR 0.78, p=0.55), or stroke (OR 1.17, p=0.77).

Conclusion:

Administration of TXA in TKA resulted in reduced rate of PJI and overall revision surgery. No difference in thromboembolic events were observed. The use of TXA is safe and improves outcomes in TKA.

Level of Evidence, Level III, Observational Cohort Study

Keywords: tranexamic acid, periprosthetic joint infection, total knee arthroplasty, revision surgery, allogenic transfusion

Introduction

Allogenic blood transfusions in knee and hip arthroplasty are associated with an increased risk of severe adverse events. Morbidity and mortality associated with these transfusions include increased length of stay[1], deep venous thrombosis (DVT)[2], wound healing problems[3], and ninety-day mortality [4]. Further, the overall long term survival of the implant is at risk as allogenic transfusions have been associated with increased rates of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) [5].

These concerns have led to a focused effort to decrease the rate of perioperative transfusions in knee and hip arthroplasty. The expanded use of anti-fibrinolytics, primarily tranexamic acid (TXA), has resulted in a large decrease in allogenic transfusions in arthroplasty procedures. Over the last decade, transfusions have decreased from about one third of all knee replacements in 2010 [6] to a current rate of approximately 2% [7–18]. This overwhelming evidence at the efficacy of TXA has led to its widespread application into practice. The ultimate goal of TXA is to reduce the complications associated with transfusions such as PJI. Further, there were initial concerns that as an antifibrinolytic agent, administration of TXA may increase the risk of postoperative vascular occlusive and thromboembolic events. As the treatment effect of TXA is large, these clinical studies have needed smaller patient numbers to demonstrate the primary end point of a reduced transfusion rate. This has made it difficult to observe differences in smaller more rare events such as periprosthetic joint infection or other adverse vascular occlusive complications such as pulmonary emboli, myocardial infarction, or stroke.

The objective of this study was to determine if the use of TXA improves long term outcomes or changes the risk of adverse events in total knee arthroplasty. As TXA reduces transfusion rates, we hypothesized that there would be a corresponding decrease in transfusion-related complications. To overcome previous limitations in observing these rare events, we designed a large multicenter retrospective observational study to quantify differences in the rates of PJI, revision surgery, and vascular occlusive events.

Methods

Study Design

A multicenter observational retrospective study was completed of all patients undergoing a primary total knee arthroplasty between 2005 and 2015. Institutional review board approval was obtained, and data were acquired from the electronic medical records and manually validated for accuracy. The study was completed at 16 hospitals in a regional health system compromising a variety of academic, private practice, and hospital-employed environments in rural and urban settings.

We performed an a priori calculation to determine the sample size required to detect a statistically significant difference in the rates of our primary outcome, PJI, and main adverse events, myocardial infarction and stroke. For PJI, we assumed a baseline rate of 1% for the group of patients not receiving TXA [19]. For myocardial infarction and stroke, we assumed a baseline rate of 0.3% for the group of patients not receiving TXA [20]. Furthermore, we assumed a 4:1 ratio of sample sizes between groups given the initial distribution in adoption of TXA at these institutions. In order to observe an approximate 50% reduction in the rate of PJI to 0.5 % in the TXA group and conclude a significant between-group difference, we would need 16,000 patients that did not receive TXA and 4,000 patients that did receive TXA. In order to observe an approximate doubling in the incidence of myocardial infarction or stroke to 0.7% in the TXA group and conclude a significant between-group difference, we would need a similar distribution of patients as calculated in our PJI sample size calculations. These calculations assumed a two-tailed z-test for the difference between two independent proportions, as well as 90% power and a type I error rate of 0.05.

Participants

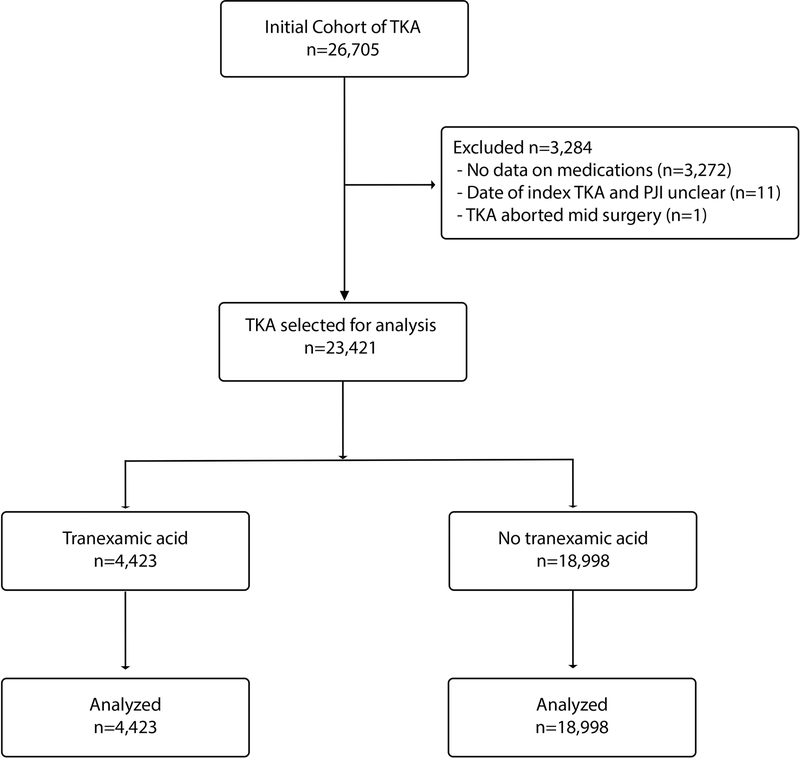

A patient flow diagram is provided demonstrating identifying participants, exclusion criteria, and distribution between treatment groups (figure 1). The initial cohort was obtained querying the medical record for all total knee arthroplasties completed at the 16 participating institutions identifying 26,705 patients. Laterality of the procedure was obtained for each primary total knee arthroplasty. Exclusion criteria included no data on intraoperative or perioperative medications (3,272), PJI diagnosis on same date as TKA (n=3), PJI diagnosis preceding the date of the TKA (n=6), Revision TKA prior to the date of the primary TKA (n=2), and abortion of TKA procedure for intraoperative medical condition (n=1).

Figure 1.

Flow of patients through the study

Description of Treatment

A total of 23,421 TKA were then analyzed to compare primary and secondary outcomes and adverse events. In this cohort, 4,423 patients were administered tranexamic acid during the TKA procedure and 18,998 patients were not administered TXA. As multiple studies have demonstrated no difference in transfusion rates between topical, intravenous, or oral administration of TXA, these were pooled into one group [22–26]. Of those undergoing TKA who were administered TXA, 61% were intravenous, 23% were oral, and 16% were topical.

Outcome Measures, Data Sources, and Bias

Irrigation and debridement procedures were defined as any deep or superficial procedure following the TKA that was defined by the surgeon as a debridement. Revision procedures were defined as any subsequent surgical procedure after the index TKA.

Diagnosis of TKA PJI was determined by the surgeon and identified using the electronic medical record. Periprosthetic joint infection was defined using the International Classification of Disease-9 code (ICD-9 code) for periprosthetic joint infection (996.66). As this diagnosis code can be used for different anatomic arthroplasty implants, TKA PJI was identified as the intersection of all patients in the medical system with the diagnosis code and a concurrent surgical procedure on the knee, as determined by the medical record.

Adverse events

Diagnosis of thromboembolic and vascular occlusive events were made by the treating surgical team and supportive consultant services, and identified using the electronic medical record.

The adverse events of pulmonary emboli, myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, and stroke were identified with their ICD-9 codes using electronic medical record data (Pulmonary emboli: 415.19, 415.1; Myocardial infarction: 410; Deep vein thrombosis: 453.40, 453.41; Stroke: 434, 436). Each of these events were then confirmed by direct review of the medical record to verify the event occurred within the appropriate time frame and met diagnostic criteria.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed to quantify demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in this study. Means and standard deviations were used for continuous variables with symmetric distributions, and medians and interquartile ranges were reported for continuous variables with skewed distributions. Categorical variables were summarized using counts and percentages.

Comorbid conditions of patients were identified using ICD-9 codes obtained from electronic medical billing records. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCMI) was calculated for each patient using the conventional method [27]. Weighted counts of a patient’s comorbid conditions were used to compute the widely-used combined comorbidity index.

Chi-square and t-tests were employed to compare these characteristics between those who received TXA and those who did not, for univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis was completed by using generalized linear mixed models with a logit link and random surgeon effect to test for differences in the proportion of TKAs that had an adverse event between those who received TXA and those who did not while adjusting for age, gender, CCMI, aspirin (ASA), and whether or not the surgery was performed before 2010. This time point was selected as it was the midpoint in the study. For the continuous outcome LOS, a generalized linear mixed model with a log link was used with the same random and fixed effects. All management of electronic medical record data and statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4.

Results

Demographics and Description of Study Participants

Demographics of the study participants were described (Table 1). Of the 23,421 cases of TKA that met inclusion criteria during the study period, 4,423 received TXA and 18,998 did not (Figure 1). There were no differences in gender or the incidence of diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis. The cohort that received tranexamic acid were older, received relatively less aspirin, and had a lower CCMI score. As adoption of the use of TXA in our system began in 2011, there was an expected difference in the use of TXA before and after 2010.

Table 1.

Patient demographic and characteristics.

| Total (n=23,421) | TXA (n=4,423) | No TXA (n=18,998) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 66.5 (9.8) | 67.5 (9.2) | 66.3 (10.0) | <0.0001 |

| CCMI, median (IQR)* | 0 (2.0) | 0 (1.0) | 0 (2.0) | <0.0001 |

| Female, N (%) | 14,704 (62.7) | 2,787 (63.0) | 11,917 (62.7) | 0.73 |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 1,479 (6.3) | 273 (6.2) | 1,206 (6.4) | 0.67 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis, N (%) | 535 (2.3) | 89 (2.0) | 446 (2.4) | 0.18 |

| TKA performed before 2010, N (%) | 4,333 (18.5) | 4 (0.1) | 4,329 (22.8) | <0.0001 |

| ASA, N (%) | 4,555 (19.5) | 729 (16.5) | 3,826 (20.1) | <0.0001 |

Charlson comorbidity index calculated excluding age as a factor.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; CCMI, Charlson comorbidity index; IQR, interquartile range; ASA, aspirin

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The use of tranexamic acid improved long-term outcomes following total knee arthroplasty (Table 2). The adjusted outcomes controlled for several factors including the use of aspirin, CCMI, age, gender, surgeon, and time of procedure. For the primary outcome, the use of tranexamic acid reduced the incidence of periprosthetic joint infection by approximately 50% in the first two years following surgery (OR 0.55, [95% CI: 0.42–0.94]; p<0.05). For secondary long-term outcomes, the rate of revision surgery at 2 years was decreased by more than 30% in those patients receiving TXA compared to those who did not (OR 0.66, [CI: 0.46–0.93]; p<0.01). There was no difference in the rate of irrigation and debridement at 2 years post-TKA between the groups (OR 1.20, [CI: 0.62–2.32]; p=0.59).

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes.

| TXA (n=4,423) | No TXA (n=18,998) | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PJI 2 yrs from surgery | 29 (0.7) | 239 (1.3) | 0.51 (0.20–0.84) | 0.014 | 0.55 (0.42–0.94) | 0.033 |

| I&D 2 yrs from surgery | 15 (0.3) | 116 (0.6) | 0.97 (0.51–1.86) | 0.93 | 1.20 (0.62–2.32) | 0.59 |

| Revision rate at 2 yrs | 46 (1.0) | 432 (2.3) | 0.59 (0.42–0.83) | 0.0027 | 0.66 (0.46–0.93) | 0.019 |

| Transfusion at 1 week | 63 (1.4) | 2,195 (11.6) | 0.15 (0.11–0.19) | <0.0001 | 0.15 (0.11–0.19) | <0.0001 |

| LOS, median (IQR) | 3.0 (0.6) | 3.2 (1.2) | 0.91* (0.89–0.93) | <0.0001 | 0.93* (0.91–0.95) | <0.0001 |

Note: This value is not an odds ratio, but a rate ratio. Abbreviations: TXA, tranexamic acid; CI, confidence interval; PJI, periprosthetic joint infection; I&D, irrigation and debridement; yrs, years; LOS, length of stay; IQR, interquartile range. Statistically significant values are highlighted.

The use of tranexamic acid improved short-term outcomes following total knee arthroplasty (Table 2). The use of tranexamic acid reduced transfusion rates from 12 to 1% (OR 0.15, [CI: 0.11–0.19]; p<0.0001). There was a 7% decrease in length of stay in those patients receiving TXA as compared to those who did not (CI: 0.91–0.95; p<0.0001).

Adverse Events

There were no differences in adverse events observed between administering or not administering tranexamic acid intraoperatively in total knee arthroplasty (Table 3). There was no difference in the rate of thromboembolic or vascular occlusive events between these two groups. This included deep vein thromboses (OR 0.92, [CI: 0.45–1.89]; p=0.82), pulmonary emboli (OR 1.2, [CI: 0.80–1.79]; p=0.39), myocardial infarction (OR 0.78, [CI: 0.34–1.77]; p=0.55), and stroke (OR 1.17, [CI: 0.41–3.37]; p=0.77). There was no difference in readmission rates between these two groups either at 30 days (OR 1.02, [CI: 0.86–1.20]; p=0.83) or 90 days (OR 1.03, [CI: 0.89–1.20]; p=0.68).

Table 3.

Adverse events.

| TXA (n=4,423) | No TXA (n=18,998) | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVT at 30 days | 11 (0.2) | 47 (0.2) | 0.87 (0.43–1.76) | 0.70 | 0.92 (0.45–1.88) | 0.82 |

| PE at 30 days | 39 (0.9) | 119 (0.6) | 1.37 (0.92–2.04) | 0.12 | 1.20 (0.80–1.79) | 0.39 |

| MI at 30 days | 8 (0.2) | 50 (0.3) | 0.70 (0.32–1.53) | 0.37 | 0.78 (0.34–1.77) | 0.55 |

| Stroke at 30 days | 5 (0.1) | 17 (0.1) | 1.12 (0.40–3.16) | 0.82 | 1.17 (0.41–3.37) | 0.77 |

| Readmission 30 days | 246 (5.6) | 1,384 (7.3) | 0.94 (0.80–1.10) | 0.44 | 1.02 (0.86–1.20) | 0.83 |

| Readmission 90 days | 327 (7.4) | 1,748 (9.2) | 0.95 (0.82–1.09) | 0.44 | 1.03 (0.89–1.20) | 0.68 |

Abbreviations: TXA, tranexamic acid; CI, confidence interval; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolus; MI, myocardial infarction. There were no statistically significant values.

Discussion

Allogenic blood transfusions in total knee arthroplasty are associated with a small increased risk of adverse long-term outcomes, including periprosthetic joint infection [28–30]. Multiple orthopaedic studies have demonstrated that tranexamic acid reduces blood transfusion rates [31–35], but these studies have not demonstrated a reduction in the risks that are associated with these transfusions. Further, as the efficacy of tranexamic acid at reducing transfusion rates is large, these well-designed clinical studies have been smaller as compared to traditional drug-based studies investigating the safety profile of a pharmaceutical agent. We completed a large multicenter retrospective observational study to quantify the long-term benefits of TXA and determine if there was an increased incidence of these more difficult to observe adverse events. Tranexamic acid was associated with a reduction in periprosthetic joint infection and its associated revision surgery, and there was no observed increased risk in thromboembolic or vascular occlusive events.

The use of tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty improves long-term outcomes, as demonstrated by reduced rates of periprosthetic joint infection and revision surgery. In patients that did not receive tranexamic acid, the rate of early periprosthetic joint infection was 1.3%. This is a comparable value to other large studies that have demonstrated that infection remains the primary cause of early failure in total knee arthroplasty [36–42]. In our cohort, the use of tranexamic acid reduced the rate of observed PJI by 50%. Other groups have observed a trend in the reduction in PJI with the use of TXA by a comparable magnitude, but given the smaller population size, this reduction was not statistically significant. We were further able to observe a decrease in overall 2-year revision surgical rates by more than 30%. As PJI is the most common reason for early failure and revision surgery in TKA, it is not surprising that a reduction in PJI observed by using TXA was also associated with a large reduction in revision surgery.

The use of tranexamic acid was observed to improve perioperative outcomes in TKA. It has been well documented that tranexamic acid reduces the rate of transfusion in TKA. Initially multiple retrospective studies [31–33, 43–45] and then prospective studies documented a large reduction in transfusion rates [34, 46, 47]. The range of reported transfusion was approximately 20 to 30% without the use of TXA. Addition of TXA reduced transfusion rates to approximately 1% [48]. Our study observed similar results and serves as an important control demonstrating the accuracy of our data for longer-term outcomes. We also observed a small but statistically significant reduction in length of stay by 7%. This is likely the result that acute post-operative anemia is typically diagnosed towards the end of the in-patient stay and requires additional monitoring during and after the transfusion. Late diagnosis of anemia would likely delay discharge.

Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic agent, and its mechanism of action in reducing blood loss is based on preventing the disruption of thrombus formation. There was an initial careful introduction of TXA based on safety concerns as thrombus formation is associated with pulmonary emboli, myocardial infarctions, and stroke. Numerous retrospective and prospective orthopaedic clinical studies have not observed an increase in thromboembolic and vascular occlusive events with TXA [49]. These high-quality studies were designed to detect differences in transfusion rates with the use of TXA. These studies had decreased patient numbers as the sample size needed to demonstrate efficacy was small as compared to the large size needed to observe an adverse event. Our a priori sample size calculation suggested that approximately 20,000 TKA would be needed to observe an approximate doubling in the incidence of myocardial infarction or stroke, assuming a reported rate of approximately 0.3% [20]. We did not observe a significant difference in thromboembolic events with or without the use of tranexamic acid with a sample size of 23, 421.

However, there are several limitations in this study that are important to consider. As with similar observational studies, there are inherent limitation including the retrospective nature of data collection and lack of randomization between treatment cohorts. We attempted to control for this by completing a multivariate analysis of patient-specific factors that are known to contribute to the risk of PJI. When this was completed, TXA continued to be an independent predictor of reduced incidence of PJI and revision rates. Additionally, as this dataset was collected from a large administrative database, we were unable to control for incomplete documentation or coding errors which other large database studies encounter. To account for this, each primary outcome, secondary outcome, and adverse event was manually confirmed within the medical record for accuracy. Unfortunately, body mass index was not consistently recorded within the medical record and hence was not included in our analysis. Furthermore, we were unable to control for surgeon specific perioperative antibiotic regimen, including use of topical vancomycin powder, dilute betadine lavage, or use of antibiotic impregnated cement. It is reasonable to consider that these factors could have influenced the incidence of PJI. Other confounders that should be considered include differences in perioperative wound care, route of TXA administration, post-operative rehabilitation protocol, and discharge disposition. Lastly, 80% of the non-TXA cohort underwent TKA while TXA was available, which may represent lack of familiarity with current best practices in arthroplasty. This confounder is likely due to the variations in hospital settings that patient data was extracted from. Thus, a multitude of factors contribute to the incidence of adverse events after TKA and it cannot be definitively concluded that TXA alone is responsible for reduction in PJI and revision surgery. Nonetheless, we believe that our results suggest that TXA is a major contributing factor to reductions in these postoperative complications.

Tranexamic acid has been widely adopted in total knee arthroplasty given its ability to reduce transfusion rates with no observed increase in adverse complications. Transfusions are associated with decreased long-term outcomes including PJI. We have demonstrated that TXA reduces the rate of PJI by almost 50% and its associated revision surgery. We did not observe a significant difference in adverse thromboembolic or vascular occlusive events. This provides important evidence for its continued widespread use. Continued evaluation, monitoring, and prospective studies are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Dr. Kenneth Urish is supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS K08AR071494), the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS KL2TR0001856), the Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation, and the Musculoskeletal Tissue Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Clair Smith, Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA 15261.

Neel B. Shah, Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Internal Medicine; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA 15219.

Scott D. Rothenberger, Center for Research on Health Care Data Center; Division of General Internal Medicine; University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; Pittsburgh, PA 15213.

Brian Hamlin, The Bone & Joint Center, Magee Womens Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA 15212.

Kenneth L. Urish, Arthritis and Arthroplasty Design Group, The Bone and Joint Center, Magee Womens Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Department of Bioengineering, and Clinical and Translational Science Institute, University of Pittsburgh; Department of Biomedical Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, 15219.

References

- 1.Bierbaum BE, Hill C, Callaghan JJ, Galante JO, Rubash HE, Tooms RE, Welch RB. An analysis of blood management in patients having a total hip or knee arthroplasty. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery -Series A 81(1): 2, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang T, Song K, Yao Y, Pan P, Jiang Q. Perioperative allogenic blood transfusion increases the incidence of postoperative deep vein thrombosis in total knee and hip arthroplasty. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 14(1), 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber EWG, Slappendel R, Prins MH, Van Der Schaaf DB, Durieux ME, Strümper D. Perioperative blood transfusions and delayed wound healing after hip replacement surgery: Effects on duration of hospitalization. Anesthesia and Analgesia 100(5): 1416, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Overgaard S, Johnsen SP. Allogeneic blood transfusion and prognosis following total hip replacement: A population-based follow up study. BMC musculoskeletal disorders 10, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pulido L, Ghanem E, Joshi A, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Periprosthetic joint infection: The incidence, timing, and predisposing factors. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 466(7): 1710, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spahn DR. Anemia and patient blood management in hip and knee surgery: A systematic review of the literature. Anesthesiology 113(2): 482, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguilera X, Martinez-Zapata MJ, Bosch A, Urŕutia G, Gonźalez JC, Jordan M, Gich I, Mayḿo RM, Martínez N, Monllau JC, Celaya F, Ferńandez JA. Efficacy and safety of fibrin glue and tranexamic acid to prevent postoperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery - Series A 95(22): 2001, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chimento GF, Huff T, Ochsner JL, Meyer M, Brandner L, Babin S. An evaluation of the use of topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty 28(8 SUPPL): 74, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbody J, Dhotar HS, Perruccio AV, Davey JR. Topical Tranexamic Acid Reduces Transfusion Rates in Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty 29(4): 681, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin JG, Cassatt KB, Kincaid-Cinnamon KA, Westendorf DS, Garton AS, Lemke JH. Topical administration of tranexamic acid in primary total hip and total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty 29(5): 889, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samujh C Decreased blood transfusion following revision total knee arthroplasty using tranexamic acid. The Journal of arthroplasty 29(9): 182, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goyal N, Chen DB, Harris IA, Rowden NJ, Kirsh G, MacDessi SJ. Intravenous vs Intra-Articular Tranexamic Acid in Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial. Journal of Arthroplasty 32(1): 28, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klika AK, Small TJ, Saleh A, Szubski CR, Chandran Pillai ALP, Barsoum WK. Primary total knee arthroplasty allogenic transfusion trends, length of stay, and complications: Nationwide inpatient sample 2000–2009. Journal of Arthroplasty 29(11): 2070, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshihara H, Yoneoka D. National Trends in the Utilization of Blood Transfusions in Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty 29(10): 1932, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bini SA, Darbinian JA, Brox WT, Khatod M. Risk Factors for Reaching the Post Operative Transfusion Trigger in a Community Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty Population. Journal of Arthroplasty 33(3): 711, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alshryda S, Sukeik M, Sarda P, Blenkinsopp J, Haddad FS, Mason JM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the topical administration of tranexamic acid in total hip and knee replacement. Bone Joint J 96-B(8): 1005, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, Mason JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 93(1): 39, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henry DA, Carless PA, Moxey AJ, O’Connell D, Stokes BJ, Fergusson DA, Ker K. Anti-fibrinolytic use for minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD001886, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah NB, Hersh BL, Kreger AM, Sayeed A, Bullock AG, Rothenberger SD, Klatt B, Hamlin B, Urish KL. Benefits and Adverse Events Associated with Extended Antibiotic Use in Total Knee Arthroplasty Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Clin Infect Dis, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Sorensen HT, Emmeluth C, Overgaard S, Johnsen SP. The risk of venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, major bleeding and death in patients undergoing total hip and knee replacement: a 15-year retrospective cohort study of routine clinical practice. Bone Joint J 96-B(4): 479, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Z, Xie X, Li L, Huang Q, Ma J, Shen B, Kraus VB, Pei F. Intravenous and Topical Tranexamic Acid Alone Are Superior to Tourniquet Use for Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 99(24): 2053, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen CS, Jans O, Orsnes T, Foss NB, Troelsen A, Husted H. Combined Intra-Articular and Intravenous Tranexamic Acid Reduces Blood Loss in Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 98(10): 835, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kayupov E, Fillingham YA, Okroj K, Plummer DR, Moric M, Gerlinger TL, Della Valle CJ. Oral and Intravenous Tranexamic Acid Are Equivalent at Reducing Blood Loss Following Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 99(5): 373, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan X, Li B, Wang Q, Zhang X. Comparison of 3 Routes of Administration of Tranexamic Acid on Primary Unilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Study. J Arthroplasty 32(9): 2738, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song EK, Seon JK, Prakash J, Seol YJ, Park YJ, Jin C. Combined Administration of IV and Topical Tranexamic Acid is Not Superior to Either Individually in Primary Navigated TKA. J Arthroplasty 32(1): 37, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yi Z, Bin S, Jing Y, Zongke Z, Pengde K, Fuxing P. Tranexamic Acid Administration in Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Intravenous Combined with Topical Versus Single-Dose Intravenous Administration. J Bone Joint Surg Am 98(12): 983, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 47(11): 1245, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pulido L, Ghanem E, Joshi A, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Periprosthetic joint infection: the incidence, timing, and predisposing factors. Clin Orthop Relat Res 466(7): 1710, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bierbaum BE, Callaghan JJ, Galante JO, Rubash HE, Tooms RE, Welch RB. An analysis of blood management in patients having a total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 81(1): 2, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JL, Park JH, Han SB, Cho IY, Jang KM. Allogeneic Blood Transfusion Is a Significant Risk Factor for Surgical-Site Infection Following Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: A Meta-Analysis. J Arthroplasty 32(1): 320, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S, Danninger T, Mazumdar M, Opperer M, Boettner F, Memtsoudis SG. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ 349: g4829, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandri A, Mimor BF, Ditta A, Finocchio E, Danzi V, Piccoli P, Regis D, Magnan B. Perioperative intravenous tranexamic acid reduces blood transfusion in primary cementless total hip arthroplasty. Acta Biomed 90(1-S): 81, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamatsuki Y, Miyazawa S, Furumatsu T, Kodama Y, Hino T, Okazaki Y, Masuda S, Okazaki Y, Ozaki T. Intra-articular 1 g tranexamic acid administration during total knee arthroplasty is safe and effective for the reduction of blood loss and blood transfusion. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alshryda S, Mason J, Vaghela M, Sarda P, Nargol A, Maheswaran S, Tulloch C, Anand S, Logishetty R, Stothart B, Hungin AP. Topical (intra-articular) tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates following total knee replacement: a randomized controlled trial (TRANX-K). J Bone Joint Surg Am 95(21): 1961, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fillingham YA, Ramkumar DB, Jevsevar DS, Yates AJ, Bini SA, Clarke HD, Schemitsch E, Johnson RL, Memtsoudis SG, Sayeed SA, Sah AP, Della Valle CJ. Tranexamic Acid Use in Total Joint Arthroplasty: The Clinical Practice Guidelines Endorsed by the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons, American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Hip Society, and Knee Society. J Arthroplasty 33(10): 3065, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koh CK, Zeng I, Ravi S, Zhu M, Vince KG, Young SW. Periprosthetic Joint Infection Is the Main Cause of Failure for Modern Knee Arthroplasty: An Analysis of 11,134 Knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res 475(9): 2194, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Chiu V, Vail TP, Rubash HE, Berry DJ. The epidemiology of revision total knee arthroplasty in the United States. Clin Orthop Relat Res 468(1): 45, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delanois RE, Mistry JB, Gwam CU, Mohamed NS, Choksi US, Mont MA. Current Epidemiology of Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty 32(9): 2663, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Postler A, Lutzner C, Beyer F, Tille E, Lutzner J. Analysis of Total Knee Arthroplasty revision causes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 19(1): 55, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le DH, Goodman SB, Maloney WJ, Huddleston JI. Current modes of failure in TKA: infection, instability, and stiffness predominate. Clin Orthop Relat Res 472(7): 2197, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fehring TK, Odum S, Griffin WL, Mason JB, Nadaud M. Early failures in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res (392): 315, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Urish KL, Qin Y, Li BY, Borza T, Sessine M, Kirk P, Hollenbeck BK, Helm JE, Lavieri MS, Skolarus TA, Jacobs BL. Predictors and Cost of Readmission in Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 33(9): 2759, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chimento GF, Huff T, Ochsner JL Jr., Meyer M, Brandner L, Babin S. An evaluation of the use of topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 28(8 Suppl): 74, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konig G, Hamlin BR, Waters JH. Topical tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 28(9): 1473, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.May JH, Rieser GR, Williams CG, Markert RJ, Bauman RD, Lawless MW. The Assessment of Blood Loss During Total Knee Arthroplasty When Comparing Intravenous vs Intracapsular Administration of Tranexamic Acid. J Arthroplasty 31(11): 2452, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong J, Abrishami A, El Beheiry H, Mahomed NN, Roderick Davey J, Gandhi R, Syed KA, Muhammad Ovais Hasan S, De Silva Y, Chung F. Topical application of tranexamic acid reduces postoperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92(15): 2503, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao G, Chen G, Huang Q, Huang Z, Alexander PG, Lin H, Xu H, Zhou Z, Pei F. The efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid for reducing blood loss following simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a multicenter retrospective study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 20(1): 325, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gianakos AL, Hurley ET, Haring RS, Yoon RS, Liporace FA. Reduction of Blood Loss by Tranexamic Acid Following Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: A Meta-Analysis. JBJS Rev 6(5): e1, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Madsen RV, Nielsen CS, Kallemose T, Husted H, Troelsen A. Low Risk of Thromboembolic Events After Routine Administration of Tranexamic Acid in Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 32(4): 1298, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.