Abstract

Context:

Patients with blood cancers have low rates of timely hospice use. Barriers to hospice use for this population are not well understood. Lack of transfusion access in most hospice settings is posited as a potential reason for low and late enrollment rates.

Objectives:

We explored the perspectives of blood cancer patients and their bereaved caregivers regarding the value of hospice services and transfusions.

Methods:

Between June 2018 and January 2019, we conducted three focus groups with blood cancer patients with an estimated life expectancy ≤ 6months and two focus groups with bereaved caregivers of blood cancer patients. We asked participants their perspectives regarding quality of life (QOL) and about the potential association of traditional hospice services and transfusions with QOL. A hematologic oncologist, sociologist, and qualitatively-trained research assistant conducted thematic analysis of the data.

Results:

Twenty-seven individuals (18 patients and nine bereaved caregivers) participated in the five focus groups. Participants identified various QOL domains that were important to them but focused largely on a desire for energy to maintain physical/functional wellbeing. Participants considered transfusions a high-priority service for their QOL. They also felt that standard hospice services were important for QOL. Bereaved caregivers reported overall positive experiences with hospice.

Conclusion:

Our analysis suggests that although blood cancer patients value hospice services, they also consider transfusions vital to their QOL. Innovative care delivery models that combine the elements of standard hospice services with other patient-valued services like transfusions are most likely to optimize end-of-life care for patients with blood cancers.

Keywords: hospice, transfusions, hematologic cancers, end-of-life care

INTRODUCTION

Hospice care is beneficial for patients with serious illness near the end of life (EOL).1, 2 Through an interdisciplinary team of physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and home health aides, hospice provides symptom-directed care to patients with a life expectancy of six months or less. Patients who enroll in hospice have better quality of life (QOL) than those who die in hospitals,1 and their caregivers are more likely to report that their loved one received excellent EOL care.2, 3 Moreover, caregivers of hospice enrollees have a lower risk of psychosocial distress.1, 4 Accordingly, several national organizations recommend timely hospice use for patients with life-limiting illnesses.5–8

Despite the benefits of hospice, patients with hematologic malignancies have low enrollment rates.9–12 In addition, when blood cancer patients enroll in hospice, they are more likely to do so in the last three days of life, thus limiting the opportunity for meaningful benefit.13 This trend in late hospice use among patients with blood cancers appears to be rising.10, 14, 15 These findings raise concerns about the quality of symptom control for patients with blood cancers, especially when placed in the context of studies demonstrating a high symptom burden in this population near the EOL.16–18

Recent large database and physician survey studies have examined potential causes of low hospice use among patients with blood cancers. Hospice services may not be adequate for the unique needs of blood cancer patients and the lack of access to blood transfusions may contribute to low rates of referral and enrollment.14, 15, 19, 20 For example, nearly 50% of hematologic oncologists in a national survey felt that hospice services were inadequate for the needs of their patients, and the majority reported they would refer more patients to hospice if blood transfusions were available.20

Despite concerns about adequacy of hospice services for patients with blood cancers, patient and caregiver perspectives regarding the value of existing hospice services (visiting nurse, social work, chaplain, home health aide, respite care) and non-routine services such as blood transfusions are unknown. Both perspectives are crucial to assure quality EOL care for this patient population. We thus aimed to characterize the perspectives of blood cancer patients and bereaved caregivers regarding the utility of existing hospice services and transfusion access with respect to their QOL.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

We conducted a qualitative study of five focus groups with blood cancer patients near the EOL and bereaved caregivers. A qualitative study design was chosen because of the lack of blood cancer patient-specific data regarding hospice and to allow for an in-depth exploration of views regarding hospice services and QOL. We chose to conduct focus groups because they are ideal for gathering information on how groups of people think about a specific topic. Focus groups enable idea generation, sharing, consensus, and debate about a topic. Moreover, the group interaction creates a dynamic environment that can activate forgotten details of individual experiences and draw out latent issues that may not be captured in one-on-one interviews.21

All focus groups were conducted at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) in Boston between June 2018 and January 2019. We conducted three focus groups with blood cancer patients and two groups with bereaved caregivers, one of which was dedicated to those whose loved ones enrolled in hospice. Eligible patients had a blood cancer, were ≥18 years old, received primary oncologic care at DFCI (defined as ≥2 outpatient visits), had received at least one transfusion, and had a life expectancy of ≤6 months based on their oncologist answering “no” to the surprise question (“would you be surprised if this patient died within the next six months?”).24, 25 Bereaved caregivers were eligible if their loved one died >3 months prior to study enrollment to avoid acute grief,26, 27 but ≤12 months to reduce recall bias. We used purposeful sampling (maximum variation sampling type) to select sufficiently information-rich cases by recruiting individuals across various types of hematologic malignancies (leukemia/myelodysplastic syndromes, lymphoma, and myeloma) and gender.22,23 To operationalize this, we presented the study to hematologic oncologists practicing in different disease groups to ensure diagnostic variation and we asked them to recommend both eligible male and female participants.

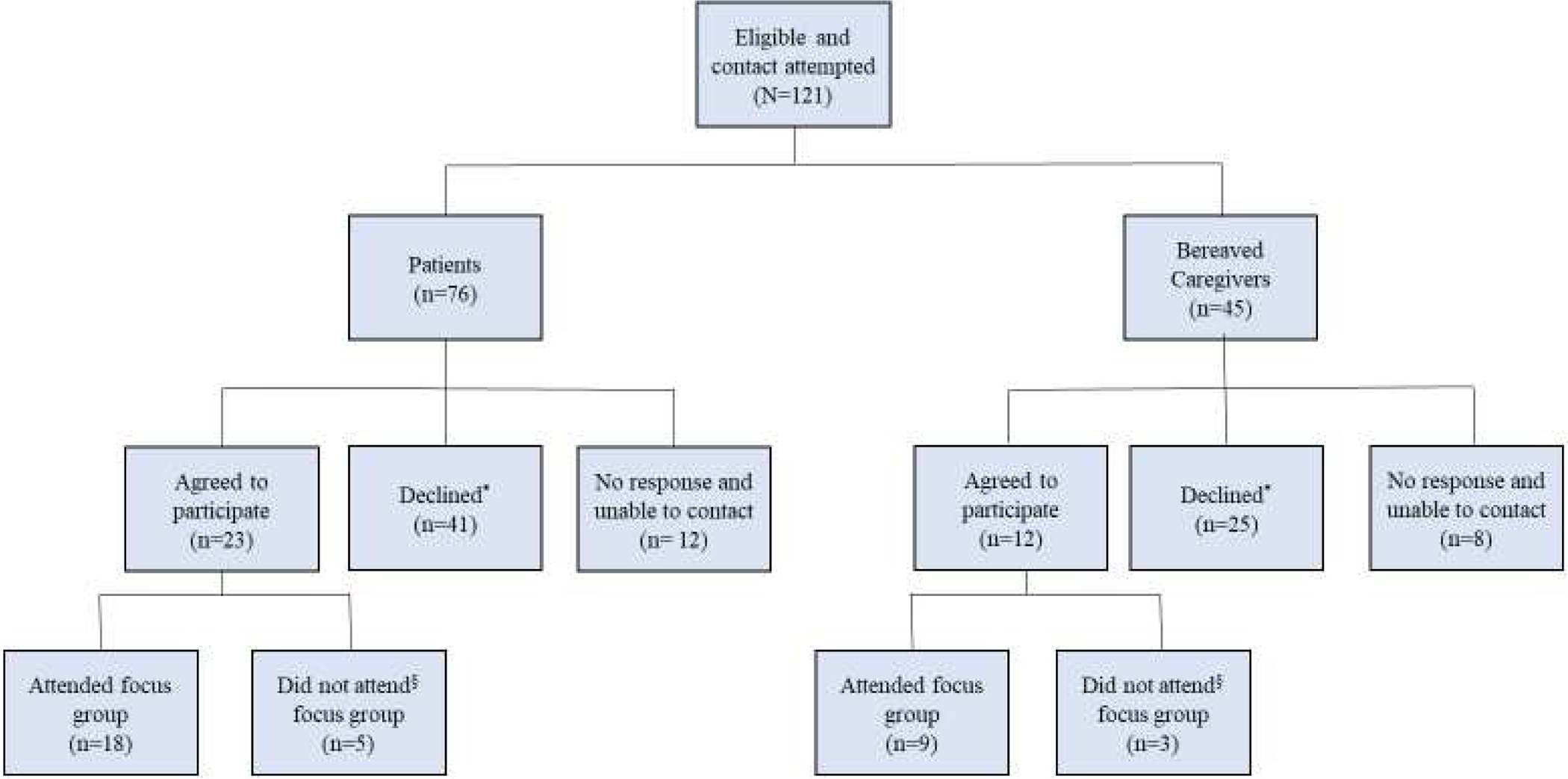

Potential participants were sent invitations by mail which included the date, time, and location of their respective focus group, as well as study staff information to confirm attendance. Pre-stamped opt-out cards were included in the mailing for those who did not wish to participate. We attempted telephone contact to non-respondents within 4 weeks of initial mailing (Figure 1). All participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Office of Human and Research Studies at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center.

Figure 1.

Participant Recruitment Flowchart

* Reasons for declining: too sick (n=3), distance/transportation (n=3), logistical conflict (n= 9), unspecified (n=51)

§ Reasons for not attending focus group: too sick (n=3), distance/transportation (n=2), logistical conflict (n=2), unspecified (n=1)

Data Collection

A semi-structured focus group guide (supplement) was developed by the research team. The guide included open-ended questions to elicit perspectives regarding QOL, existing or desired supportive care services, and transfusion access for patients with blood cancers. We first asked participants to describe what good QOL meant to them. Participants were provided a list of standard hospice services (home health aide, visiting nurse, social worker, chaplain, respite care), and alternative services (transfusion access, nutrition services, telemedicine). We asked participants to reflect on these services and discuss their perspectives on the importance of such services for QOL of blood cancer patients. Given the strength of qualitative research in capturing unanticipated aspects of care that are important to participants, we also collected data on issues that emerged unprompted during the focus group discussion. Participants received a $50 gift card. Focus groups were moderated by a study member (AR) and a note taker was present at each session. Each focus group lasted approximately 90 minutes. All sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service.

Data Analysis

We used a combination of inductive and deductive approaches to code and analyze the data. A hematologic oncologist, sociologist, and qualitatively-trained research assistant conducted thematic analysis of the qualitative data, with additional review by a palliative care physician and two hematologic oncologists. First, members of the study team (AR, CH, OO) read the transcripts and met iteratively to identify and define codes. Once a comprehensive code book was developed, each transcript was independently coded by two study members, using NVivo 12 software. Intercoder reliability was achieved through systematically comparing and discussing discrepancies which arose between the readers’ application of codes (kappa >0.85).28 To ensure interpretive consistency, the research team collaboratively reviewed the coded contents, identified emergent themes and patterns, and synthesized the data across themes, both within and across participant types.

RESULTS

Twenty-seven individuals participated in the focus groups, including 18 blood cancer patients and 9 bereaved caregivers (Table 1). Five key themes are explored below: i) QOL comprises multiple domains for patients with blood cancers, ii) Patients and caregivers value transfusions, iii) Standard elements of hospice and other services have high utility for patients with blood cancers, iv) Hospice positively influences EOL care for patients with blood cancers, and v) Caregivers desire early goals of care discussions (Table 2)

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants (n=27)

| Characteristic | Patients (n=18) | Bereaved Caregivers (n=9) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 12 (67%) | 1 (11%) |

| Female | 6 (33%) | 8 (89%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 15 (83%) | 9 (100%) |

| Nonwhite | 3 (17%) | 0 (0) |

| Education | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 10 (56%) | 7 (78%) |

| Less than bachelor’s degree | 8 (44%) | 2 (22%) |

| Diagnosis* | ||

| Leukemia/myelodysplastic syndromes | 7 (39%) | 6 (67%) |

| Lymphoma | 7 (39%) | 2 (22%) |

| Myeloma | 4 (22%) | 1 (11%) |

| Relationship of bereaved caregiver to patient | ||

| Spouse/partner | NA | 6 (67%) |

| Child/other | 3 (33%) |

For bereaved caregivers, this describes the diagnosis of their deceased loved one.

Table 2.

Themes

| Theme | Representative Quote |

|---|---|

| QOL comprises multiple domains for patients with blood cancers |

“At this point—the key thing so far is about energy…I can be feeling without energy whatsoever. I have a long list of things to do and they don’t get done.” P2 “I wanted to be able to be independent around the house…I can remember when I first started treatment. It was during the winter. And I emotionally got totally distraught because my wife had to go clean off the car from a snowstorm. That just bothered me to no end.” P11 “I was going through a rough patch so it was a bit difficult and quality of life wasn’t really good. However, I got to—I didn’t get to eat with my family and kids because I couldn’t, and I didn’t get to open gifts or maybe go do things with them.” P17 “I think independence is the thing I cherish the most. I like to do things for my myself, by myself, not have other people do them for me.” P3 “he was pretty beat up from - between the leukemia and some of the treatment, so he was definitely struggling to do day to day - like getting out of breath walking up the stairs, that type of thing. Like if we could go for a walk around the block, that was - a nice day.” BC2 “And my father used to always feel better after his appointments because he would leave there and say we know what’s happening for the next six days. Let’s go. That and just as we needed it, pain management. That was important for us.” BC8 |

| Patients and caregivers value transfusions |

“But when I get a blood transfusion, I can - I have a little more spunk.” P15 “I’ve had platelets and hemoglobin - platelets more often than hemoglobin. And I consider them lifesavers…they enable me to feel better physically and emotionally.” P1 “So for me, it [transfusions] absolutely—it sustains my life…It’s both lifesaving ad I do feel better in the short realm. When I need the transfusion, it’s because my energy level is low…So it has a direct impact on every aspect of my life really.” P2 “And so the transfusions don’t seem to have any—it’s not like chemo where you think I wish I hadn’t done this because it’s destroyed my quality of life. And what I’ve experienced was that after transfusion, I actually felt better. So, I just can’t see any downside to it.” P7 “I’ll get petechiae and I know I need platelets or I can’t - I’m winded and can’t do a whole lot and I know I need blood, and I do feel much better after I get blood.” P17 “You are here all day if you need all the blood transfusions and stuff like that…But my biggest problem is the transportation getting back and forth…” P18 “when he was so ill, I mean, it’s not like a choice. Would you like a bag of platelets? It’s like you need a bag of platelets now.” BC1 “I feel like my husband could usually tell when - like if his crit was really low, he could usually tell or if his platelets were low enough that he would need a transfusion, likely he’d be bruising or bleeding. So it was obviously helpful to get that when he needed it. But there were so many times where it was like well, you had the chemo on whatever day, so you have to come in to get the labs to see if you need a transfusion. And it just felt like a waste of time honestly. And he got a ton of transfusions, so obviously it helped.” BC2 “I think it [transfusions] added to the quality of life…I mean, my husband would be - you know, he’d be pretty logy and then he’d get the transfusions and it’d perk him up. He was good - much better.” BC5 “We always thought they [transfusions] were positive. On the days that he got the transfusions, we would always plan a big dinner that night because he’d have more energy. So that would be a night we’d get together and have like a little mini party…it gave him strength so we looked at it positively. BC8 |

| Standard elements of hospice and other services have high utility for patients with blood cancers |

“Well, getting back to the list, I prioritized the top two - home health aide and visiting nurse. I’m lucky enough that I don’t need either of those right now. But I get the sense everyone here is married or was married. I’m not. And so, it’s going to come a time when I’ll be relying on services like that.” P6 “I put down access to transfusions [as a high priority service], simply because sometimes it’s just simply a necessity.” P11 “In my case, my mom takes care of me. I can’t do housework. I can’t cook. I can’t clean. I can’t go to stores, so I can’t grocery shop. I can’t - so I see her tiring and tiring and tiring. And the level of stress of dealing with her daughter having leukemia is just - and she doesn’t get a break. I was looking at the respite care. That would be good if she could have a break.” P17 “I think it would be very helpful to talk about peer to peer whenever—to also on occasion be able to talk to someone who can empathize with what you’re going through. And I’m not talking about a medical professional. I’m talking about somebody who’s digging dirt while you’re digging dirt.” P3 “One downside of…creating a relationship is that the people that you’re dealing with are very fragile, as are you…There was a man…who had the same kind of transplant situation I did. And I would call him every now and then, but then…his health deteriorated, and he passed away.” P7 “She [social worker] would speak with him very candidly about his fears of dying and what was his biggest fear about dying” BC5 |

| Hospice positively influences EOL care for patients with blood cancers |

“I’m going to this hospice now for grief counseling…it is just like a beautiful place for families and the patients with their families.” BC3 “my husband was only on hospice one day, but it was amazing—it made the difference in our lives…so hospice I thought was awesome. And we would have had it, but you can’t have it while you’re having treatment. So - but even for one day, it was amazing.” BC5 “I had some wonderful [hospice] nurses. I do have to say that. The nurse that came was on a daily basis twice a day. She was very good. I loved her.” BC4 “We had hospice…and they did an awfully good job. They kept us at peace.” BC9 “I was just so scared because I was the one giving him [medications] because he was agitated and thrashing in the bed and he was just doing everything that he never had done before. And I kept thinking oh, my…I can’t do this. And I just kept thinking - they [hospice] kept saying to me, if you need us, call us. Well, what was I going to do, call them every hour because I was having a hard time giving him the morphine and all of that?…I was so overwhelmed that I didn’t know what to do.” BC4 “…It was kind of like falling off a cliff because you’ve been working with a great class A medical team for years, and the switch to hospice was just dramatic, and I think some helping with that transition would be helpful. Though hospice is good and what they do is great, it’s just such a big change from coming to Dana-Farber” BC7 |

| Caregivers desire early goals of care discussions |

“I don’t think the doctors talk about death, so the patients don’t talk about death. It’s the elephant in the room.” BC1 “Well, she was very candid. She would speak with him very candidly about his fears of dying and what was his biggest fear about dying…It’s the elephant in the room. There’s no point in not talking about it.” BC5 “We ended up finding a hospice. But I think I would have liked hospice discussed earlier in the process, because that last round of chemo really changed the way her mind was able to work and not work…if we had stopped [chemo] earlier, we would have gotten a better quality of life” BC6 “If I could have one thing to help, it would be to have a frank discussion of what’s important to the patient and what’s a top priority to still be able to do and what they really don’t want to go through and have that inform the treatment. It would be really nice to have a frank conversation early about like if you can’t walk, what makes your day good? What makes your day worth having? And if you’re not going to be able to able to have that day, how quick do you want it to be over.” BC6 “So, the whole approach to living with serious illness and the conversation - who is spearheading? Who is able to have conversations with the patient-any of us- about what matters to us now? In the context of people who are ill and getting sicker, who says so, what’s it worth to you now? What makes meaning for you at this moment in your illness?” P2 “Who do I turn to and ask for - excuse me - end-of-life type of help? Because that’s the situation I’m in right now. I’ve tried to do everything I can on my own as far as setting things up for my [family]. But I still have to contact a funeral home. I guess what I’m saying - I guess who to talk to - to somebody about the situation that I’m in that my time is limited. Where do I go? Who do I talk to? Who do I see?” P5 |

QOL Comprises Multiple Domains for Patients with Blood Cancers

Participants across all focus groups described QOL for patients with blood cancers under broad domains of physical/functional (e.g. having energy), emotional (e.g. absence of anxiety), and social wellbeing (e.g. spending time with friends/family). Physical/functional wellbeing was the most commonly identified domain, with several participants expressing that energy to function independently and do “normal things”—such as walking, going out—is vital. Absence of pain was not vocalized in any of the patient focus groups when defining QOL; however, a bereaved caregiver noted that pain management was important for their loved one’s QOL.

Barriers to physical/functional QOL included cancer symptoms and treatment side-effects (e.g. fatigue and dyspnea). For example, “he [my husband] was pretty beat up from—between the leukemia and some of the treatment, so he was definitely struggling to do day to day—like getting out of breath walking up the stairs” (BC2). The ensuing need to rely on the physical support of other people was emotionally difficult for some patients, especially when it led to role shifts in existing relationships. Medical care such as multiple hospitalizations was often noted to hinder social wellbeing by taking away time spent with family.

Patients and Caregivers Value Transfusions

Transfusions were reported across all patient and caregiver focus groups to have a positive impact on QOL. Benefits discussed were largely physical such as improvement in energy, dyspnea, and allowing patients to engage in activities they enjoyed, “I’m winded and can’t do a whole lot and I know I need blood, and I do feel much better after I get blood.” (P17). Similar experiences were described by caregivers, “And on the days that he got the transfusion, we would always plan a big dinner that night because he’d have more energy. So that would be a night we’d get together and have like a little mini party, right….it gave him strength” (BC8). Additionally, patient and caregivers expressed that transfusions were necessary for survival; and as such, they felt that lack of access to transfusions was not a viable choice. For example, a patient said regarding transfusions, “I would be dead without them” (P7).

While views about transfusions were overwhelmingly positive, participants acknowledged downsides such as the time required and concern about potential complications. Nonetheless, participants felt that the benefits far outweighed the downsides. Although the benefit/risk ratio of transfusions was almost universally in favor of transfusions, a caregiver (BC2) expressed some ambivalence. She noted that although blood transfusions improved her loved one’s symptoms, there were times when there was no discernable improvement and, in those situations, time that could have been spent with family was lost traveling for transfusions.

Overall, participants felt that transfusion access for patients with blood cancers should be a prioritized service. Some patients also expressed that it would be helpful if transfusions could be administered in the home setting to eliminate the burden of travel. At the same time, they raised concern about the potential risk of errors with home-based transfusions.

Standard Elements of Hospice and Other Services Have High Utility for Patients with Blood Cancers

Both patients and caregivers across all focus groups identified several high priority services typically present within hospice as well as others not routinely provided by hospice. Among traditional hospice services, participants especially valued visiting nurses and expressed the desire for more visits and lengthier duration of visits. Patients also considered social workers a source of emotional support and resource for accessing other services, while caregivers discussed the value of social workers with respect to communicating candidly with patients and families about dying. Chaplaincy services were not considered high priority for patients and caregivers because some relied on alternate sources of spiritual support and others did not consider themselves religious. With respect to services not routinely present in hospice, participants across all focus groups felt transfusion access should be a high-priority service. Several participants also considered telemedicine to be valuable given the potential to eliminate travel time in connecting with their clinical team.

In addition to the list of services presented at each session, all patient focus groups emphatically voiced a desire for peer support/connection with other patients. Participants reported that living with a blood cancer is isolating and connecting with other patients could provide invaluable emotional support, “I think it would be very helpful to talk about peer to peer whenever—to also on occasion be able to talk to someone who can empathize with what you’re going through. And I’m not talking about a medical professional. I’m talking about somebody who’s digging dirt while you’re digging dirt” (P3). While the best method to operationalize peer support was not determined, participants felt that blood cancer-specificity was important. Although participants spoke extensively of the importance of peer support, one acknowledged the difficulty that could arise when a patient dies: “One downside of…creating a relationship is that the people that you’re dealing with are very fragile, as are you…There was a man…who had the same kind of transplant situation I did. And I would call him every now and then, but then…his health deteriorated and he passed away” (P7). Another service suggested by participants was the need for care coordination. Participants felt that dealing with blood cancer was so complex and having a point person to help organize seamless coordination of care would be helpful, “…But the coordination of services is such a crying need…” (P2):

Hospice Positively Influences EOL Care for Patients with Blood Cancers

Bereaved caregivers (n=6) that participated in the focus group dedicated to those whose loved ones enrolled in hospice reported diverse but positive hospice experiences, often noting that hospice providers were kind and kept them at peace. A caregiver whose loved one enrolled in hospice the day before his death reported that it was beneficial despite the short exposure: “my husband was only on hospice one day, but it was amazing because it made the difference in our lives” (BC5). Another caregiver who participated in bereavement counseling through a hospice (even though her spouse did not enroll) had such a positive experience that she wished that her spouse had the opportunity to experience hospice care. Although views about hospice were largely positive, some caregivers reported that switching from a close relationship with their hematologic oncology team to a new hospice team was challenging and they desired support with the transition. Several caregivers also reported feeling overwhelmed about the level of medical care (e.g. administering pain medications) they had to provide their loved ones and they desired more hands-on support from hospice providers.

Caregivers Desire Early Goals of Care Discussions

Bereaved caregivers felt that although goals of care (GOC) discussions are important, both physicians and patients tend to avoid them, “I don’t think the doctors talk about death, so the patients don’t talk about death. It’s the elephant in the room” (BC1). Participants acknowledged that the unpredictable nature of their loved one’s disease and the likelihood of response to treatments made it challenging to anticipate the best time to engage in GOC conversations, especially those regarding hospice. The consensus, however, was that direct and early discussions about death and dying would be most beneficial rather than waiting till death is close. Caregivers felt that doctors engaging in GOC discussions with patients and families earlier in the disease course could make such discussions less scary and provide the added benefit of setting expectations and avoiding unnecessary treatments near the EOL,“I would have liked to have hospice discussed earlier in the process, because that last round of chemo really changed the way her mind was able to work” (BC6).

DISCUSSION

We identified several themes regarding the association of hospice services and transfusions with QOL from the perspectives of blood cancer patients and bereaved caregivers. First, we found that QOL for patients with blood cancers spans several domains, ranging from physical/functional to emotional wellbeing. Second, patients with blood cancers and their caregivers consider transfusions essential for QOL. Third, while services like transfusions and peer support are valuable for blood cancer patients, standard hospice services like visiting nurses also have high utility. Finally, caregivers of patients who enrolled in hospice reported positive experiences, and desired GOC discussions earlier in the disease course. Taken together, our data suggest that although patients with blood cancer value hospice services, they also consider transfusions vital for their QOL.

Our finding that seriously ill blood cancer patients emphasized a ubiquitous desire for energy is aligned with studies demonstrating that fatigue is one of the most common impairments for this population.29, 30 For example, in a cross-sectional study of patients with cancer, those with blood cancers reported greater levels of fatigue compared to other patients.30 Interestingly, despite rich discussions regarding physical/functional QOL in our study, participants rarely mentioned absence of pain as a consideration. This corroborates physician-based studies, which posit that pain may not be a highly prevalent issue for blood cancer patients near the EOL.31, 32 Although hospice focuses on aggressive symptom management with an emphasis on QOL, there are more effective tools available to hospice practitioners for pain management than for fatigue. The fact that patients with blood cancers perceive energy to be of greater significance to QOL than pain management may thus foster the viewpoint that hospice is less relevant for them. Instead, patients with blood cancers may opt for transfusion services to reduce fatigue.

Although several studies have suggested that transfusion access is important for blood cancer patients near the EOL,14, 15, 19 and the American Society of Hematology recently endorsed consideration of such access in hospice,33 data from this patient population is sparse. Our participants deemed transfusions vital for QOL and a significant factor when making hospice decisions. Consequently, the lack of transfusion availability in most hospice settings34 is likely a critical barrier to enrollment. In a study of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes, transfusion-dependent patients were less likely to enroll in hospice.14 Another study of acute myeloid leukemia patients who disenrolled from hospice found that 62% did so to receive transfusion support.15 Although palliative transfusions are consistent with the hospice philosophy to help people live as well as possible with their disease, many hospice organizations are unable to provide this resource due to reimbursement constraints. Innovative hospice delivery and payment models that incorporate transfusions may increase hospice use for blood cancer patients.

Peer support—a service that is not routinely part of hospice care—was highly cited by participants as important for QOL. Peer support helps to overcome feelings of isolation and can promote emotional wellbeing by providing shared experiences for patients. Although multiple studies integrate peer support during the cancer continuum, very few focus on the EOL phase.35, 36 Our data demonstrate the need to develop and test the impact of peer support interventions on QOL for blood cancer patients near the EOL. Such interventions must be sufficiently nuanced to address emotions that may accompany the death of fellow patients included in peer networks.

Despite participants’ interest in services not routinely provided in hospice, they also felt several standard hospice services were important, suggesting that hospice has value for blood cancer patients near the EOL. Moreover, although caregivers of patients who enrolled in hospice identified challenges with hospice transition and desired more hands-on hospice involvement, they overall considered their hospice experience to be positive. Accordingly, to optimize QOL for patients with blood cancers near the EOL, strategies that combine typical hospice services with non-traditional services (e.g. transfusions) will likely be more effective than focusing exclusively on one type of service.

An important determinant of hospice use is timely GOC discussions. Previous data have demonstrated that GOC discussions for blood cancer patients often occur too late and a substantial proportion of hospice discussions are initiated only when death is clearly imminent.37 While several reasons including high prognostic uncertainty and concerns about taking away patients’ hope are cited as reasons for late discussions, we found that participants desired early and direct discussions regarding hospice and dying. Concurrent with interventions that incorporate high-utility services within hospice, physician-targeted interventions to promote timely GOC discussions are needed to improve hospice use for this patient population.

Our study has limitations. First, because all our participants received care in a single tertiary setting, their perspectives may not be generalizable to patients who receive care in community settings. Second, our small sample size precluded us from assessing if participant characteristics were associated with certain perspectives. Finally, our study may be susceptible to participation bias such that individuals who had more favorable views regarding hospice may have chosen to participate; however, our recruitment letters advertised the study as focused on quality of life and made no specific mention of hospice.

Blood cancer patients near the EOL have a broad range of needs and value services that directly meet those needs. The high priority placed on palliative transfusions—coupled with limited access in most hospices—may partly explain low rates of hospice use by this population. On the other hand, the positive impact of routine hospice services reported by patients and caregivers suggests that focusing solely on transfusion access absent hospice is likely insufficient for optimizing QOL. Innovative strategies that harmonize existing hospice services with other patient-valued services such as transfusion access are likely the most effective way to improve EOL care for patients with blood cancers.

Supplementary Material

KEY MESSAGE.

In this focus group study, patients with blood cancers and their caregivers considered transfusions vital for quality of life and also valued standard hospice services. This suggests that harmonizing existing hospice services with other patient-valued services (e.g. transfusions) has the potential to improve EOL care for blood cancer patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

O.O. Odejide received research support from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NCI K08 CA218295)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES

No relevant financial conflict of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300: 1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291: 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Family Perspectives on Aggressive Cancer Care Near the End of Life. JAMA. 2016;315: 284–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kris AE, Cherlin EJ, Prigerson H, et al. Length of hospice enrollment and subsequent depression in family caregivers: 13-month follow-up study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14: 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. The Quality Oncology Practice Initiative Quality Measures. Available from URL: http://www.instituteforquality.org/qopi/measures [accessed August 1, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peppercorn JM, Smith TJ, Helft PR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement: Toward Individualized Care for Patients With Advanced Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29: 755–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Quality Forum. National Voluntary Consensus Standards: Palliative Care and End-of-Life Care: A Consensus Report. Available from URL: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2012/04/Palliative_Care_and_End-of-Life_Care%e2%80%94A_Consensus_Report.aspx [accessed August 1, 2019].

- 8.Dans M, Smith T, Back A, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Palliative Care, Version 2.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15: 989–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26: 3860–3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Earle CC, LaCasce AS, Abel GA. Hospice Use Among Patients With Lymphoma: Impact of Disease Aggressiveness and Curability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sexauer A, Cheng MJ, Knight L, Riley AW, King L, Smith TJ. Patterns of hospice use in patients dying from hematologic malignancies. J Palliat Med. 2014;17: 195–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Jawahri AR, Abel GA, Steensma DP, et al. Health care utilization and end-of-life care for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2015;121: 2840–2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connor NR, Hu R, Harris PS, Ache K, Casarett DJ. Hospice admissions for cancer in the final days of life: independent predictors and implications for quality measures. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32: 3184–3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fletcher SA, Cronin AM, Zeidan AM, et al. Intensity of end-of-life care for patients with myelodysplastic syndromes: Findings from a large national database. Cancer. 2016;122: 1209–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang R, Zeidan AM, Halene S, et al. Health Care Use by Older Adults With Acute Myeloid Leukemia at the End of Life. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35: 3417–3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manitta V, Zordan R, Cole-Sinclair M, Nandurkar H, Philip J. The symptom burden of patients with hematological malignancy: a cross-sectional observational study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42: 432–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geyer HL, Scherber RM, Dueck AC, et al. Distinct clustering of symptomatic burden among myeloproliferative neoplasm patients: retrospective assessment in 1470 patients. Blood. 2014;123: 3803–3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeBlanc TW, Smith JM, Currow DC. Symptom burden of haematological malignancies as death approaches in a community palliative care service: a retrospective cohort study of a consecutive case series. Lancet Haematol. 2015;2: e334–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeBlanc TW, Egan PC, Olszewski AJ. Transfusion dependence, use of hospice services, and quality of end-of-life care in leukemia. Blood. 2018;132: 717–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Earle CC, Tulsky JA, Abel GA. Why are patients with blood cancers more likely to die without hospice? Cancer. 2017;123: 3377–3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation. 2009;119: 1442–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, et al. Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2010;13: 837–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hui D Prognostication of Survival in Patients With Advanced Cancer: Predicting the Unpredictable? Cancer Control. 2015;22: 489–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DiBiasio EL, Clark MA, Gozalo PL, Spence C, Casarett DJ, Teno JM. Timing of Survey Administration After Hospice Patient Death: Stability of Bereaved Respondents. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50: 17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casarett DJ, Crowley R, Hirschman KB. Surveys to assess satisfaction with end-of-life care: does timing matter? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25: 128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burkholder GJ, Cox KA, Crawford LM, Hitchock JH. Research Design and Methods: An Applied Guide for the Scholar-Practitioner. SAGE, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowe JR, Yu Y, Wolf S, Samsa G, LeBlanc TW. A Cohort Study of Patient-Reported Outcomes and Healthcare Utilization in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients Receiving Active Cancer Therapy in the Last Six Months of Life. J Palliat Med. 2018;21: 592–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hochman MJ, Yu Y, Wolf SP, Samsa GP, Kamal AH, LeBlanc TW. Comparing the Palliative Care Needs of Patients With Hematologic and Solid Malignancies. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55: 82–88 e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LeBlanc TW, O’Donnell JD, Crowley-Matoka M, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among hematologic malignancy specialists: a mixed-methods study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11: e230–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odejide OO, Salas Coronado DY, Watts CD, Wright AA, Abel GA. End-of-life care for blood cancers: a series of focus groups with hematologic oncologists. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10: e396–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Society of Hematology. ASH Statement in Support of Palliative Blood Transfusions in Hospice Setting. Available from URL: https://www.hematology.org/Advocacy/Statements/9723.aspx [accessed July 1, 2019].

- 34.Johnson KS, Payne R, Kuchibhatla MN, Tulsky JA. Are Hospice Admission Practices Associated With Hospice Enrollment for Older African Americans and Whites? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51: 697–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoey LM, Ieropoli SC, White VM, Jefford M. Systematic review of peer-support programs for people with cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70: 315–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kowitt SD, Ellis KR, Carlisle V, et al. Peer support opportunities across the cancer care continuum: a systematic scoping review of recent peer-reviewed literature. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27: 97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Condron N, Earle CC, Wolfe J, Abel GA. Timeliness of End-of-Life Discussions for Blood Cancers: A National Survey of Hematologic Oncologists. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176: 263–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.