Abstract

Background:

Ileostomy surgery is associated with a high readmission rate, and care pathways to prevent readmissions have been proposed. However, the extent to which readmission rates have improved is unknown. This study examined rates of readmission and emergency department visits (“return to hospital”, or RTH) across hospitals in Michigan.

Methods:

This was a retrospective cohort study of patients undergoing colorectal surgery with ileostomy formation from July 2012 to August 2017 in twenty Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative (MSQC) hospitals. Primary outcome was RTH within 30 days of surgery. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify risk factors for RTH. RTH rates over time were calculated, and hospitals’ risk-adjusted rates were estimated using a multivariable model. Hospitals were divided into quartiles by risk-adjusted RTH rates, and RTH rates were compared between quartiles.

Results:

Of 982 patients, 28.5% experienced RTH. Rates of RTH did not decrease over time. Adjusted hospital RTH rates ranged from 9.4% to 43.3%. The risk-adjusted rate in the best performing hospital quartile was 17.5% vs. 37.3% in the worst-performing quartile (p< 0.001). Hospitals that were outliers for ileostomy RTH were not outliers for colorectal resection RTH in general.

Conclusions:

Rates of RTH following ileostomy surgery are high and vary between hospitals. This suggests inconsistent or ineffective use of pathways to prevent these events and potential for improvement. There is clear opportunity to standardize care to prevent RTH after ileostomy surgery.

Keywords: ileostomy, hospital readmission, colorectal surgery, colectomy

Introduction

More than 38,000 Americans undergo ileostomy surgery each year for rectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, and other conditions.(1) It is known that ileostomy surgery is associated with a very high rate of readmissions, due to complications including dehydration.(2-9) To address this problem, several groups have implemented programs to decrease readmission rates for ileostomy patients.(10) Nagle and colleagues’ well-known study showed that readmissions for dehydration could be eliminated using a program involving standardized patient education and post-discharge care.(10)

However, the extent to which these advances have improved “real world” clinical practice is unknown. A recent study by Fish and colleagues showed a 39% rate of return to hospital (RTH, emergency room visits and/or readmissions) after ileostomy surgery, suggesting an ongoing problem with high RTH rates.(2) Understanding of this problem is hampered by a lack of population-based studies of ileostomy surgery, as most studies on this topic have been single-institution retrospective reviews.(2-4, 6-8)

In this context, the goal of the present study was to perform a multi-institutional study of ileostomy surgery, with a focus on readmissions and emergency room visits after discharge (we called this composite outcome “return to hospital”, or RTH). We hypothesized that there would be variation between hospitals in rates of RTH. If this were the case, surgical quality improvement based upon regional best practices could be pursued.

Methods

Patient Population and Setting:

This was a retrospective cohort study of patients in the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative (MSQC). The MSQC is a voluntary regional surgical quality improvement organization, with 72 hospitals currently participating. Nurses in each participating hospital abstract clinical data and 30-day outcomes from a sampling of surgical cases, selected using methodology to avoid bias.(11) The MSQC is funded by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan, which provides funding for each institution’s nurse data abstractor. However, the organization is independently run by physicians and nurses.

Cases were identified from the timeframe of July 2012 to August 2017. The cohort was restricted to patients from hospitals that had at least 35 eligible cases in the MSQC database, since valid hospital comparisons are not possible when case numbers are extremely small. Cases were included according to this process: they had to have an eligible Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code (44120, 44125, 44130, 44140, 44141, 44143, 44144, 44145, 44146, 44150, 44151, 44156, 44157, 44158, 44205, 44206, 44207, 44208, 44210, 44211, 45111, 45113, 45119, 45397). Next, the MSQC has an “ostomy” variable (options: ileostomy, colostomy, neither ileostomy nor colostomy, unknown), and cases had to have “ileostomy” recorded for this variable. Finally, all cases with the CPT codes 44155, 44187, 44212, 44310 were included, as these codes denote formation of an ileostomy. Cases for which it could not be determined whether or not an ileostomy was created were excluded. All diagnosis codes were permitted (Appendix Table 1).

Outcome and Covariates:

The primary outcome was “return to hospital” (RTH), defined as either emergency room visit and/or readmission within 30 days of surgery. Covariates associated with this outcome were identified using bivariate analysis, starting with risk factors for readmission from the literature and identified by clinical experts on the research team.(2, 4-7) Covariates tested for association with the outcome are listed in Table 1. These included age (dichotomized as <70 v. >=70), Sex, race (white v. other), BMI (dichotomized as < or >=35), functional status (independent v. dependent), urgent/emergent case priority, one or more postoperative complications, surgical approach [open v. minimally invasive (MIS)], diagnosis (neoplasm v. diverticular disease v. inflammatory bowel disease v. other), insurance type, and discharge destination (home v. home with home healthcare v. skilled nursing facility v. other).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Cohort (n=982)

| Variable | Category | Overall | No Readmission or ED |

Readmission or ED |

Probability chi-square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Less than 70 | 707 (72%) |

498 (71%) |

209 (75%) |

0.243 |

| Greater than or equal to 70 | 275 (28%) |

204 (29%) |

71 (25%) |

||

| Sex | Female | 488 (50%) |

345 (71%) |

143 (29%) |

0.586 |

| Male | 494 (50%) |

357 (72%) |

137 (28%) |

||

| Race | White |

827 (87%) |

602 ( 89%) |

225 ( 83%) |

0.0165* |

| Non-white |

125 (13%) |

78 (11%) |

47 ( 17%) |

||

| BMI | Less than 35 | 847 (86%) |

609 (87%) |

238 (85%) |

0.472 |

| Greater than or equal to 35 | 135 (14%) |

93 (13%) |

42 (15%) |

||

| Dependent Status | Not dependent | 854 (88%) |

603 (86%) |

251 (90%) |

0.097 |

| Dependent | 122 (13%) |

95 (14%) |

27 (10%) |

||

| Urgent-Emergent Operation | Elective | 500 (51%) |

360 (51%) |

140 (50%) |

0.717 |

| Urgent-emergent | 482 (49%) |

342 (49%) |

140 (50%) |

||

| Complications | No complication | 562 (57%) |

439 (63%) |

123 (44%) |

<0.0001* |

| One or more complication | 420 (43%) |

263 (37%) |

157 (56%) |

||

| Length of Stay | Days [Median (IQR)] | 9 (5-15) |

9 (5-16) |

8 (5-14) |

0.714 |

| Minimally Invasive Surgery | MIS | 315 (32%) |

225 (32%) |

90 (32%) |

0.961 |

| Open | 665 (68%) |

476 (68%) |

189 (68%) |

||

| Diagnosis | Neoplasm | 315 (32%) |

226 (32%) |

89 (32%) |

0.902 |

| Diverticular Disease | 97 (10%) |

61 (9%) |

36 (13%) |

0.048* | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 231 (24%) |

154 (22%) |

77 (28%) |

0.064 | |

| Other | 339 (35%) |

261 (37%) |

78 (28%) |

0.006* | |

| Insurance | Commercial non-HMO | 278 (28%) |

203 (29%) |

75 (27%) |

0.503 |

| HMO | 155 (16%) |

106 (15%) |

49 (18%) |

0.352 | |

| Government Insurance | 408 (42%) |

298 (42%) |

110 (39%) |

0.364 | |

| Medicaid | 59 (6%) |

36 (5%) |

23 (8%) |

0.066 | |

| Uninsured | 21 (2%) |

14 (2%) |

7 (3%) |

0.621 | |

| Other | 43 (4%) |

31 (4%) |

12 (4%) |

0.928 | |

| Discharge Destination | Home |

225 (23%) |

155 (22%) |

70 (25%) |

<0.0001* |

| Home w/Home Healthcare |

447 (46%) |

297 (42%) |

150 (54%) |

||

| SNF |

130 (13%) |

84 (12%) |

46 (16%) |

||

| Other |

180 (18%) |

166 (24%) |

14 (5%) |

statistically-significant

ED=emergency department visit; BMI=body mass index; MIS=minimally-invasive surgery; HMO=health maintenance organization; SNF=skilled nursing facility

Statistical Analysis:

A patient-level analysis was conducted, and descriptive statistics were used to characterize the patient cohort and hospital characteristics. Categorical variables were tested for association with RTH using Chi-Square tests, except in the case of small cell sizes where Fisher’s Exact test was performed. For hospital comparisons, multivariable logistic regression was constructed by entering covariates in a stepwise approach to identify factors for risk adjustment. The final risk-adjustment model included age, sex, race, dependent status, complications, and discharge destination. Age, sex, and dependent status were kept in the model for face validity, but were not independently associated with RTH in multivariable analysis for the ileostomy cohort.

A hospital-level analysis was then performed. Only hospitals with at least 35 ileostomy cases in the database were included in the analysis (n=20 hospitals). Hospital characteristics were obtained from the American Hospital Association (Appendix Table 2). Risk adjusted rates of RTH where then determined, with 95% confidence intervals, using the aforementioned logistic regression model. Hospitals were also divided into quartiles based upon their return to hospital rates, to determine whether quartiles had significantly different adjusted rates.

To determine whether hospitals with high RTH rates for ileostomy surgery also had high RTH rates for other colorectal operations, we conducted an exploratory analysis comparing RTH performance for ileostomy cases v. for non-ostomy colorectal resection cases. Colorectal resection cases without ostomy were defined as cases with CPT codes 44140, 44160, 44204, 44205, 44208, 44210, 45111and “neither ileostomy or colostomy” coded for the MSQC ostomy variable. For this comparator cohort, the risk adjustment model (derived via stepwise selection as above) included age, sex, race, dependent status, complications, urgent/emergent status, Medicaid insurance, and discharge destination. All analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4 (Cary, NC). This study met the criteria for “not regulated” status by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board-Medical.

Results

Patient Characteristics and RTH:

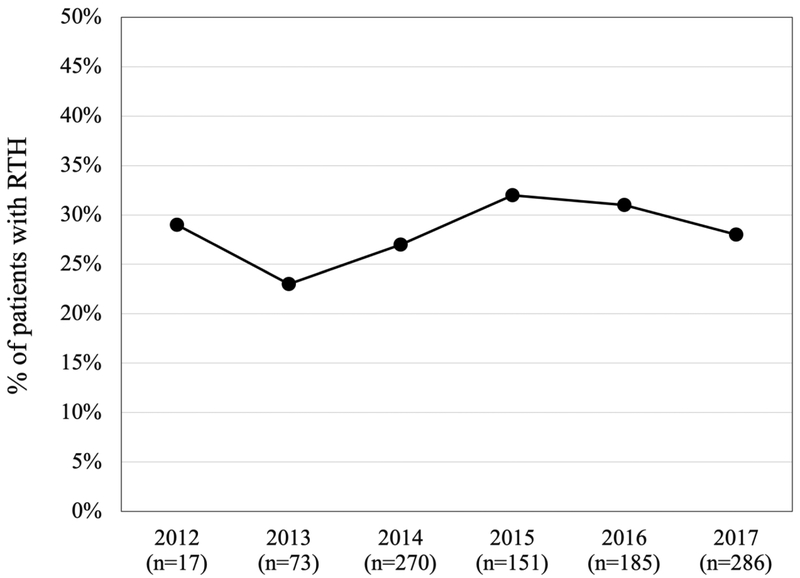

982 patients from 20 hospitals were included in the study. Characteristics of patients with and without RTH are shown in Table 1. Overall, 28.5% of patients returned to hospital after ileostomy surgery, with 20.4% being readmitted. The rate of RTH did not decline over time (Figure 1). Factors independently associated with RTH included: race, surgical complications, and discharge destination (Table 2).

Figure 1:

Observed RTH Rate by Year. The unadjusted yearly rate of RTH after ileostomy surgery ranged from 23 – 32% of cases.

Table 2:

Multivariable Risk-Adjustment Model (Composite Outcome: Readmission and/or Visit to Emergency Department)

| Variable | Category | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

95% Wald Confidence Limits |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 70 or greater | 1.066 | 0.721 | 1.576 |

| Sex | Female v. male | 1.031 | 0.761 | 1.396 |

| Race | Non-white v. white | 1.611* | 1.048 | 2.478 |

| Dependent status | Dependent v. independent | 1.02 | 0.584 | 1.781 |

| Complications | Any v. none | 3.66* | 2.634 | 5.086 |

| Discharge Destination | Home health v. home | 0.988 | 0.682 | 1.431 |

| SNF v. home | 0.643 | 0.362 | 1.142 | |

| Other v. home | 0.082* | 0.04 | 0.167 | |

Statistically-significant. SNF=skilled nursing facility

Further analysis of association between discharge destination and RTH reveals that almost half of patients in our cohort were discharged home with home healthcare (46%, compared to 23% discharged home without home healthcare and 13% discharged to SNF). However, the RTH rate was 34% for the home healthcare group, compared to 31% for the home without home healthcare group. Thus, having a visiting nurse was not protective against RTH.

Hospital Characteristics and Variation in RTH:

The 20 hospitals included in the study had the following characteristics, based on the American Hospital Association database: they tended to be in the highest quartile for size and operative volume; in the highest quartile of hospitals for Medicaid discharges; part of a hospital network; and affiliated with a medical school (Appendix Table 2).

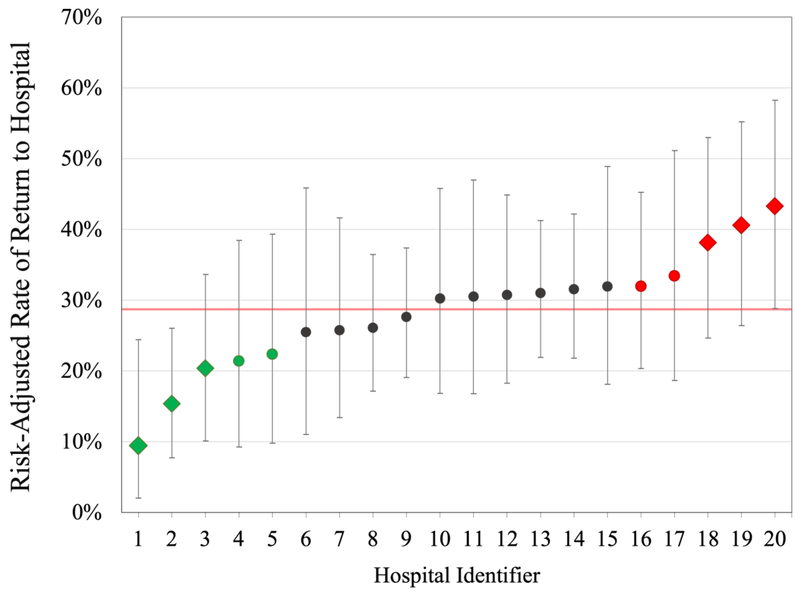

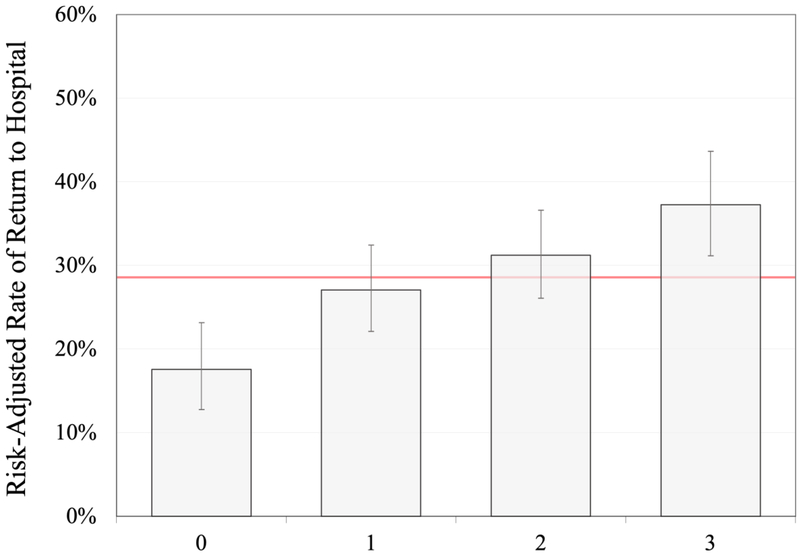

Hospitals’ adjusted rates of RTH ranged from 9.4% to 43.3% (Figure 2). Hospital quartiles differed significantly in their adjusted rates of RTH (Figure 3). Patients in the hospitals in the quartile with the lowest rates of RTH (best-performing) had a risk-adjusted rate of was 17.5% compared to 37.3% in the worst-performing quartile (p-value < 0.001).

Figure 2:

Variation in Hospital RTH Rates. Risk-adjusted hospital RTH rates ranged from 9.4% to 43.3%. The red line marks the average hospital RTH rate across the MSQC. Green markers denote hospitals in the best-performing quartile (with diamonds marking the best performers), while red markers denote hospitals in the worst-performing quartile (with diamonds marking the worst performers).

Figure 3:

Differences in RTH between Hospital Quartiles. The best-performing quartile of hospitals had a significantly lower adjusted RTH rate compared to the worst-performing quartile (17.5% vs. 37.3%, p<0.001). The red line marks the average hospital RTH rate across the MSQC.

Hospitals’ RTH rates for non-ileostomy colorectal surgery v. ileostomy:

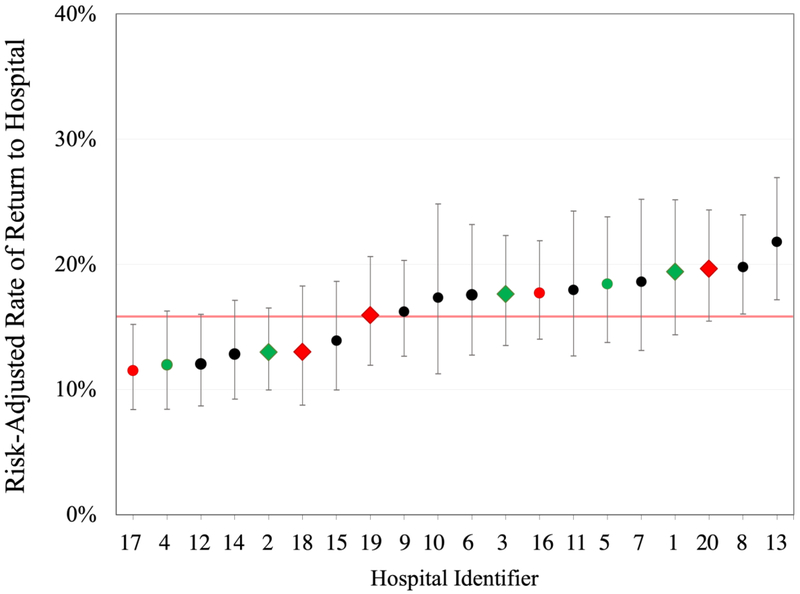

To investigate whether high RTH rates for ileostomy surgery were simply a reflection of high RTH rates for that hospital generally, we examined hospitals’ RTH performance for non-ileostomy colorectal resection cases to determine whether outliers for ileostomy surgery RTH were also outliers for RTH in other colorectal cases. Hospitals with the highest and lowest RTH rates for ileostomy surgery (marked with stars in Figure 4) were not the same hospitals that had highest or lowest RTH rates for colorectal resections without ileostomy (Figure 4).

Figure 4:

Hospital RTH Performance in Non-Ileostomy Colorectal Surgery. In this figure, hospitals are ranked by performance in non-ileostomy colorectal surgery. Green and red markers denote the best- and worst-performing quartiles for RTH in ileostomy surgery. These same hospitals do not have similar performance for non-ileostomy colorectal surgery. The red line marks the average hospital RTH rate across the MSQC.

Discussion

In this multi-institutional study of ileostomy surgery, we found that rates of RTH are extremely high, with a statewide rate of 28.5%. Despite published pathways for decreasing readmissions, rates have not decreased over time in our cohort. Furthermore, hospitals vary in their performance on this outcome. This indicates that there is opportunity to decrease rates of RTH, based upon the best practices of the hospitals with lowest rates of RTH.

Hospital readmissions and emergency department visits are costly events, and have been targeted for payment reductions by government and private healthcare insurers.(12, 13) Critics of this approach note that, in general, it is unclear what proportion of hospital readmissions are avoidable.(14) However, ileostomy surgery provides a unique opportunity to decrease readmissions, because studies in which discharge practices were standardized demonstrate significantly decreased rates of readmission.(10, 15) It is important to point out that our outcome, RTH (readmission and/or emergency department visit) is different from the outcome measured in most studies of pathways to decrease readmissions after ileostomy surgery (readmissions). However, we think it is likely that RTH and readmission involve the same mechanisms and will respond to the same interventions.

The present study found very similar risk factors to the study by Fish and colleagues.(2) As expected, in both studies there is a strong association between surgical complications and subsequent RTH. Other studies on readmission after ileostomy have noted a variety of risk factors for readmission, including age, male sex, renal and cardiovascular comorbidities, steroid use, diabetes, depression, preoperative chemotherapy or radiation therapy, laparoscopic surgery, lack of social support, and lack of ostomy education.(4-7)

We conducted an exploratory analysis comparing hospitals’ RTH performance for ileostomy v. non-ostomy colorectal resections to understand whether high RTH for ileostomy surgery was simply a marker of high RTH for colorectal surgery in that hospital. In other words, this analysis explored whether the RTH problem was unique to ileostomy care, or part of an institutional pattern. We found that the hospitals with highest RTH rates for ileostomy surgery did not have highest RTH rates for other colorectal resections. This finding suggests that ileostomy readmissions are a unique problem that likely requires specific and tailored interventions, such as the ileostomy pathways reported in the literature.(10, 15)

Limitations of this study include its retrospective nature and the absence of several key covariates in our data. These include: in-hospital ileostomy output, anti-motility drug use, whether or not patients were marked for their ostomy pre-operatively, the extent of perioperative ostomy teaching, health literacy, and English literacy. Each of these factors might influence risk, and we would have liked to test these for association with RTH. However, these variables are not available in the MSQC data. In addition, small case numbers affected our study in several ways. First, most MSQC hospitals had too few cases to allow for statistically-valid comparisons. We recognize that because this study excludes low-volume hospitals for ileostomy surgery, that results may not apply to low-volume centers, which may have a different risk profile. Also, the small case numbers allowed only a few statistical outliers to be identified in the hospital-level analysis, requiring us to group hospitals into quartiles to demonstrate the variation convincingly. Furthermore, we currently do not know whether the best-performing hospitals had actually implemented programs to decrease readmissions for this type of surgery.

Despite these limitations, this study has the advantage of being statewide, and using a high-quality clinical registry rather than administrative data. This makes the results more generalizable than prior studies. Furthermore, this work will form the basis for future study of best-performing hospitals, to determine patterns of care associated with lower risk of RTH. Through the MSQC, we ultimately we hope to decrease RTH after ileostomy surgery in Michigan, statewide.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is significant variation between hospitals in their risk-adjusted rates of RTH after ileostomy surgery. This is a promising area for surgical quality improvement projects, with potential approaches including the implementation of care pathways to decrease this costly problem.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the participation of the MSQC hospitals, their MSQC nurses, and their surgeon champions.

Financial support and role of the funding source

There was no direct grant support for this study, but several authors have research support:

-Dr. Hendren receives financial support for research from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Research Foundation.

-Dr. Vu receives financial support for research from the Ruth L Kirschstein National Research Service Award (1F32DK115340-01A1).

-Dr. Suwanabol receives funding for research from the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract and the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Research Foundation, and the American College of Surgeons.

-Dr. Hardiman receives funding from the National Cancer Institute, K08CA190645.

-The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative (the setting and data source for this research study) is funded by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM). By agreement, BCBSM is not provided with individual hospital performance data but sees only aggregate and de-identified data. There was no influence from BCBSM in the study design, data collection or analysis, writing or decision to submit this work for publication.

-The authors report no conflicts of interest in the research presented.

Appendix

Appendix Table 1:

Diagnosis Groupings by ICD9 and ICD10 Codes

| Diagnosis Codes for Surgery |

ICD10 codes | ICD9 codes |

|---|---|---|

| Neoplasms | ||

| Colorectal cancer |

|

|

| Colorectal adenomas/polyps |

|

|

| Other neoplasms |

|

|

| Diverticular Disease | ||

| Diverticular disease |

|

|

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | ||

| IBD |

|

|

| Other | ||

| Hemorrhage |

|

|

| Obstruction/ileus |

|

|

| Other inflammatory disease |

|

|

| Vascular insufficiency |

|

|

| Diagnosis Codes for Readmissions and ED Visits |

ICD10 codes | ICD9 codes |

| Acute renal failure |

|

|

| Dehydration/fluid imbalance |

|

|

| SSI |

|

|

| Ileus/ nausea/ vomiting |

|

|

| Ileostomy |

|

|

| Other postoperative infections |

|

|

| Pain |

|

|

Appendix Table 2:

Hospital Characteristics

| Hospital characteristic | # of hospitals | % of hospitals |

|---|---|---|

|

MAPP5_recode Medical school affiliation reported to American Medical Association |

No 3, yes 17 | 85 |

|

MAPP8_recode Member of Council of Teaching Hospital of the Association of American Medical Colleges (COTH) |

No 14, yes 6 | 30 |

|

MAPP18_recode Critical Access Hospital |

No 20 | 0 |

|

MAPP19_recode Rural Referral Center |

No 20 | 0 |

|

MEDHME_recode Does your hospital have an established medical home program? |

No 3, yes 17 | 85 |

|

NETWRK_recode Is the hospital a participant in a network |

No 5, yes 15 | 75 |

|

PHYGP_recode Is hospital owned in whole or in part by physicians or a physicians group |

No 20 | 0 |

|

admtot_grp4_flag Total facility admissions |

Lower quartiles 5, highest quartile 15 | 75 |

|

bdtot_grp4_flag Total facility beds set up and staffed at the end of reporting period |

Lower quartiles 6, highest quartile 14 | 70 |

|

genbd_grp4_flag General medical and surgical (adult) beds |

Lower quartiles 8, highest quartile 12 | 60 |

|

hospbd_grp4_flag Total hospital beds |

Lower quartiles 6, highest quartile 14 | 70 |

|

lbedsa_grp4_flag Licensed Beds Total Facility |

Lower quartiles 6, highest quartile 14 | 70 |

|

mcddc_grp3_flag Total facility Medicaid discharges |

Lower tertiles 3, highest tertile 17 | 85 |

|

rehabbd_grp3_flag Physical Rehabilitation care beds |

Lower tertiles 9, highest tertile 11 | 55 |

|

snbd88_grp2_flag Skilled nursing care beds |

No 18, yes 2 | 10 |

|

suropip_grp4_flag Inpatient surgical operations |

Lower quartiles 6, highest quartile 14 | 70 |

|

suropop_grp4_flag Outpatient surgical operations |

Lower quartiles 8, highest quartile 12 | 60 |

|

suroptot_grp4_flag Total surgical operations |

Lower quartiles 6, highest quartile 14 | 70 |

Footnotes

Meeting Presentation: American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Annual Meeting, Nashville, TN, poster presentation. May 19-23, 2018.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Gwen B Turnbull R, BS. The Ostomy Files: Ostomy Statistics: The $64,000 Question. Ostomy Wound Management. 2003 6/January/2003;49(6). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fish DR, Mancuso CA, Garcia-Aguilar JE, et al. Readmission After Ileostomy Creation: Retrospective Review of a Common and Significant Event. Ann Surg. 2017. February;265(2):379–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glasgow MA, Shields K, Vogel RI, Teoh D, Argenta PA. Postoperative readmissions following ileostomy formation among patients with a gynecologic malignancy. Gynecologic oncology. 2014. September;134(3):561–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayden DM, Pinzon MC, Francescatti AB, et al. Hospital readmission for fluid and electrolyte abnormalities following ileostomy construction: preventable or unpredictable? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013. February;17(2):298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iqbal A, Sakharuk I, Goldstein L, et al. Readmission After Elective Ileostomy in Colorectal Surgery Is Predictable. JSLS. 2018. Jul-Sep;22(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Justiniano CF, Temple LK, Swanger AA, et al. Readmissions With Dehydration After Ileostomy Creation: Rethinking Risk Factors. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2018. November;61(11):1297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li W, Stocchi L, Cherla D, et al. Factors associated with hospital readmission following diverting ileostomy creation. Tech Coloproctol. 2017. August;21(8):641–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Messaris E, Sehgal R, Deiling S, et al. Dehydration is the most common indication for readmission after diverting ileostomy creation. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2012. February;55(2):175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paquette IM, Solan P, Rafferty JF, Ferguson MA, Davis BR. Readmission for dehydration or renal failure after ileostomy creation. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2013. August;56(8):974–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagle D, Pare T, Keenan E, Marcet K, Tizio S, Poylin V. Ileostomy pathway virtually eliminates readmissions for dehydration in new ostomates. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2012. December;55(12):1266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collaborative MSQ. 2019 MSQC Program Manual. Available at: https://reports.msqc.org/Registry/content/resources?menuId=3025. Accessed March 6, 2019, 2019.

- 12.Cross IB. Inpatient hospital readmission policy changes: Frequently asked questions. Available at: http://provcomm.ibx.com/ProvComm/ProvComm.nsf/0/0a79cfe370afd5d1852581670054a350/$FILE/IBC_Inpatient%20readmissions%20FAQ_20170816.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2018.

- 13.CMS.gov. Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). Available at: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed October 7, 2018.

- 14.van Walraven C, Bennett C, Jennings A, Austin PC, Forster AJ. Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2011. April 19;183(7):E391–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaffer VO, Owi T, Kumarusamy MA, et al. Decreasing Hospital Readmission in Ileostomy Patients: Results of Novel Pilot Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2017. April;224(4):425–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]