Abstract

Context.

Fatigue is a symptom reported by patients with a variety of chronic conditions. However, it is unclear whether fatigue is similar across conditions. Better understanding its nature could provide important clues regarding the mechanisms underlying fatigue and aid in developing more effective therapeutic interventions to decrease fatigue and improve quality of life.

Objectives.

To better understand the nature of fatigue, we performed a qualitative metasynthesis exploring patients’ experiences of fatigue across five chronic noninfectious conditions: heart failure, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Methods.

We identified 34 qualitative studies written in the last 10 years describing fatigue in patients with one of the aforementioned conditions using three databases (Embase, PubMed, and CINAHL). Studies with patient quotes describing fatigue were synthesized, integrated, and interpreted.

Results.

Across conditions, patients consistently described fatigue as persistent overwhelming tiredness, severe lack of energy, and physical weakness that worsened over time. Four common themes emerged: running out of batteries, a bad life, associated symptoms (e.g., sleep disturbance, impaired cognition, and depression), and feeling misunderstood by others, with a fear of not being believed or being perceived negatively.

Conclusion.

In adults with heart failure, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, we found that fatigue was characterized by severe energy depletion, which had negative impacts on patients’ lives and caused associated symptoms that exacerbated fatigue. Yet, fatigue is commonly misunderstood and inadequately acknowledged.

Keywords: Fatigue, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis

Introduction

Fatigue is a commonly reported symptom across chronic conditions that may occur with diagnosis or as a prodrome months or years before diagnosis.1 A common definition of fatigue is an overwhelming feeling of sustained exhaustion that is debilitating and interferes with an individual’s ability to function and perform activities.2 Typically, fatigue is dichotomized into acute or chronic fatigue, where chronic fatigue persists for six months or longer.2

Although prior studies have investigated fatigue in specific illnesses (e.g., acute myocardial infarction, cancer, and fibromyalgia), few studies have compared fatigue across chronic conditions. Only one previous study by Whitehead et al.3 performed in 2016 compared the experience of fatigue across chronic conditions. Just more than half of the participants in the studies included in this review were diagnosed with cancer. Our study builds on the review by Whitehead et al. by including studies published after 2016 and focusing on noncancer-related fatigue. We recently conducted a systematic review of the quantitative literature on fatigue to describe and compare biological mediators of fatigue in five noninfectious chronic illnesses: heart failure (HF), multiple sclerosis (MS),4 rheumatoid arthritis (RA), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).5 It was clear from that review that the definition and measures of fatigue varied across studies, and it was unclear whether fatigue is experienced in the same manner across chronic illnesses. Thus, in the present metasynthesis, we explored the qualitative experience of fatigue across these same conditions.

Gaining insight into the experience of fatigue in multiple chronic conditions can contribute to better understanding of this symptom, aid in improving fatigue management, and ultimately increase quality of life (QoL) for people with various chronic conditions. The World Health Organization defines QoL as a person’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.6 Better understanding patients’ experience of fatigue can help in successfully evaluating and managing their goals, expectations, standards, or concerns to improve the lives of people living with fatigue. With this goal in mind, the purpose of this qualitative metasynthesis was to explore the experiences of fatigue in chronically ill adults living with HF, MS, RA, CKD, or COPD to expand our understanding of fatigue, with the ultimate goal of improving the evaluation and management of fatigue.

Methods

We performed a metasynthesis of qualitative research using the qualitative metasynthesis methods proposed by Sandelowski and Barroso.7–9 We integrated, synthesized, and interpreted qualitative descriptions of fatigue across five chronically ill patient populations (HF, MS, RA, CKD, and COPD).9 These five conditions were chosen as they are all chronic noninfectious conditions known to be associated with fatigue.

Search Strategy

Working with biomedical library specialists, three databases (Embase, PubMed, and CINAHL) were searched to identify qualitative studies of fatigue in each individual chronic condition. These databases were used to replicate the approach we used in the quantitative review. Both electronic and manual searching methods were used. Only articles with primary data (i.e., patient quote(s)) were considered. Inclusion criteria were qualitative or mixed-method studies of adults (19 years of age or older) written in English and published in the decade between 2008 and 2018 except for Embase, where the search function is limited to five years. We ended the review interval at 2018 to provide time for synthesis and interpretation. This period was selected because a large number of relevant studies was available for review; 2484 qualitative studies on fatigue were indexed in PubMed between 2008 and 2018 compared with 835 indexed between 1998 and 2007.

Exclusion criteria were editorials, letters, conference abstracts, and unpublished dissertations. In addition, studies that did not provide or report at least one illustrative quote describing patients’ experience of fatigue were excluded. All articles meeting inclusion and exclusion eligibility criteria were reviewed for content and quality. In addition, references of each study were reviewed to identify other relevant literature. With the help of our biomedical library specialists, we refined our search strategy until all relevant articles were captured through the electronic search, and no additional articles were identified in the hand search. At an early stage, we agreed on use of a reference manager tool, created shared documents, and developed a system to track reasons for article exclusion. We decided how to manage the information and how to display the results. An example of a search statement and a summary of our inclusion exclusion criteria is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search Strategy Used, With HF and PubMed Shown as an Example

| Search ((narrativ* OR “Empirical Research”[Mesh] OR story OR stories OR phenomenolog* OR qualitative* OR ethnograph* OR “interview” OR “thematic” OR “interpretive”) AND (“fatigue”[Mesh] or fatigue) AND (“Heart Failure”[Mesh]OR “heart failure”[title])) |

| Filters: published in the last 10 years; English; adult: 19+ yrs |

| Summary of inclusion and exclusion criteria: Inclusion criteria–qualitative or mixed-method studies of adult populations written in English and published between 2008 and 2018; exclusion criteria–editorials, letters, conference abstracts, unpublished dissertations, and case studies |

HF = heart failure.

Analysis of Findings

We followed the method of Sandelowski and Barroso10 method of integrating the analysis to facilitate identification of data patterns and deviations.9 This method consists of six steps: conceiving the synthesis, examining the literature, appraising findings, classifying findings, synthesizing findings into metasummaries, and synthesizing findings into a metasynthesis.

Conceiving the Synthesis, Examining the Literature, and Appraising Findings (Steps 1–3).

Our goal was to better understand the nature of fatigue across five chronic noninfectious conditions. Articles were retrieved from the structured literature searches. Examining the literature involved careful review of each article, identifying methodological strengths and flaws, and locating relevant results. Each author led the review of studies focused on one of the five chronic conditions (HF, MS, RA, CKD, and COPD), independently extracted data, and scored article quality. Then, the entire team reviewed and discussed each article during routine meetings. Any uncertainty about the study relevance, findings/data, and quality was discussed by the group.

To appraise our findings, we used the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP)11 quality criteria for qualitative research to evaluate individual articles. The CASP qualitative checklist includes 10 questions and guided instructions to systematically assess each study based on multiple criteria (e.g., validity, significance, and clarity). Each of the questions received a score between zero and two; zero (cannot tell), one (no), and two (yes).12 Total scores range from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating better quality studies. The main purpose in quality appraisal was to explore whether the studies contributed to our study purpose and to evaluate validity of the study results. Studies were not excluded based on quality,13 but we discussed poor quality studies to determine whether they influenced the overall results. Any uncertainty about study quality was discussed as a group. The CASP score for each individual study is reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Study Characteristics

| Studies by Chronic Condition |

|

|

| HF | ||

| Dickson et al.17 |

|

|

| Gwaltney et al.18 |

|

|

| Hagglund et al.15 |

|

|

| Holden et al.20 |

|

|

| Jones et al.23 |

|

|

| Jurgens et al.19 |

|

|

| Norberg et al.21 |

|

|

| Walsh et al.22 |

|

|

| MS | ||

| Al-Sharman et al.24 |

|

|

| Kayes et al.12 |

|

|

| Lohne et al.11 |

|

|

| Moriya and Kutsumi25 |

|

|

| Newland et al.26 |

|

|

| Barlow et al.27 |

|

|

| Turpin et al.28 |

|

|

| RA | ||

| Connolly et al.29 |

|

|

| Feldthusen et al.30 |

|

|

| Minnock et al.31 |

|

|

| Mortada et al.32 |

|

|

| Nikolaus et al.33 |

|

|

| Repping-Wuts et al.34 |

|

|

| Thomsen et al.4 |

|

|

| CKD | ||

| Cox et al.36 |

|

|

| Kazemi et al.37 |

|

|

| Monaro et al.38 |

|

|

| Picariello et al.41 |

|

|

| Pugh-Clarke et al.42 |

|

|

| Schipper et al.39 |

|

|

| Yngman-Uhlin et al.40 |

|

|

| COPD | ||

| Kouijzer et al.43 |

|

|

| Paap et al.44 |

|

|

| Stridsman et al.45 |

|

|

| Wortz et al.46 |

|

|

| Shalit et al.47 |

|

|

CASP = Critical Appraisal Skills Program; HF = heart failure; MS = multiple sclerosis; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; TNFi = tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; CKD = chronic kidney disease; ESRD = end-stage renal disease; COPD = chronic = obstructive pulmonary disease; HRQOL = health-related quality of life.

Classifying and Integrating Summaries Into Metasummaries and Metasyntheses (Steps 4–6).

We classified the findings within each condition to systematically identify shared concepts and themes. These results were then integrated into metasummaries. Each author integrated findings focused on one of the five chronic conditions (HF, MS, RA, CKD, and COPD). Then, the entire team reviewed and discussed each of the five metasummaries, noting similarities and differences across the five chronic conditions.

Our approach to synthesizing involved translating findings of the qualitative studies into first-order, second-order (Table 3), and third-order themes.10 First-order themes examined patients’ descriptions of fatigue (i.e., direct patient quotes). Second-order themes referred to themes derived by the authors of each qualitative study (i.e., authors’ interpretation of patients’ descriptions of fatigue). Third-order themes reflected our interpretation and synthesis of all the qualitative studies. To identify first-order themes, quotes where participants described fatigue, lethargy, or reduced activity were extracted from the articles. To identify second-order themes, the authors’ paraphrases, conclusions, and observations were extracted from the results and discussion section of each study.

Table 3.

Themes Associated With Fatigue

| Authors (Yr) | First-Order Themes (Participants’ Quotes) | Second-Order Themes (Authors’ Interpretation) |

|---|---|---|

| HF | ||

| Dickson et al. (2013)17 |

|

|

| Gwaltney et al. (2012)18 |

|

|

| Hagglund et al. (2008)15 |

|

|

| Holden et al. (2015)20 |

|

|

| Jones et al. (2012)23 |

|

|

| Jurgens et al. (2009)19 |

|

|

| Norberg et al. (2017)21 |

|

|

| Walsh et al. (2018)22 |

|

|

| MS | ||

| Al-Sharman et al. (2018)24 |

|

|

| Barlow et al. (2009)27 |

|

|

| Kayes et al. (2011)12 |

|

|

| Lohne et al. (2010)11 |

|

|

| Moriya and Kutsumi (2010)25 |

|

|

| Newland et al. (2012)26 |

|

|

| Turpin et al. (2018)28 |

|

|

| RA | ||

| Connolly et al. (2015)29 |

|

|

| Feldthusen et al. (2013)30 |

|

|

| Minnock et al. (2017)31 |

|

|

| Mortada et al. (2015)32 |

|

|

| Nikolaus et al. (2010)33 |

|

|

| Repping-Wuts et al. (2008)34 |

|

|

| Thomsen et al. (2015)4 |

|

|

| CKD | ||

| Cox et al. (2017)36 |

|

|

| Kazemi et al. (2011)37 |

|

|

| Monaro et al. (2014)38 |

|

|

| Picariello et al. (2018)41 |

|

|

| Pugh-Clarke et al. (2017)42 |

|

|

| Schipper et al. (2016)39 |

|

|

| Yngman-Uhlin et al. (2010)40 |

|

|

| COPD | ||

| Kouijzer et al. (2018)43 |

|

|

| Paap et al. (2014)44 |

|

|

| Stridsman et al. (2014)45 |

|

|

| Wortz et al. (2012)46 |

|

|

| Shalit et al. (2016)47 |

|

|

HF = heart failure; ADL = activities of daily living; MS = multiple sclerosis; CKD = chronic kidney disease; QoL = quality of life; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The third order of themes (Table 4) involved combining, synthesizing, and interpreting the first-order and second-order themes14 within and across the five chronic conditions. At each stage of data abstraction, we discussed the studies to achieve consensus regarding the review and coding of data. Discrepancies were discussed by the team and resolved. Concepts and themes were identified and agreed on by all members of the team.

Table 4.

Summary of the Third-Order Themes by Study and Chronic Condition

| Studies by Chronic Condition | Running Out of Batteries | Bad Life | Associated Symptoms | Feeling Misunderstood |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | ||||

| Dickson et al.17 | ◆ | ◆ | ||

| Gwaltney et al.18 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |

| Hagglund et al.15 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Holden et al.20 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |

| Jones et al.23 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Jurgens et al.19 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Norberg et al.21 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Walsh et al.22 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| MS | ||||

| Al-Sharman et al.24 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Kayes et al.12 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |

| Lohne et al.11 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Moriya and Kutsumi25 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Newland et al.26 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Barlow et al.27 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Turpin et al.28 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| RA | ||||

| Connolly et al.29 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Feldthusen et al.30 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Minnock et al.31 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Mortada et al.32 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |

| Nikolaus et al.33 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Repping-Wuts et al.34 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Thomsen et al.4 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |

| CKD | ||||

| Cox et al.36 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Kazemi et al.37 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Monaro et al.38 | ◆ | ◆ | ||

| Picariello et al.41 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Pugh-Clarke et al.42 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Schipper et al.39 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Yngman-Uhlin et al.40 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| COPD | ||||

| Kouijzer et al.43 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Paap et al.44 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |

| Stridsman et al.45 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Wortz et al.46 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ |

| Shalit et al.47 | ◆ | ◆ | ◆ | |

HF = heart failure; MS = multiple sclerosis; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; CKD = chronic kidney disease; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The symbol ‘◆’ denotes third-order themes included in the study.

Results

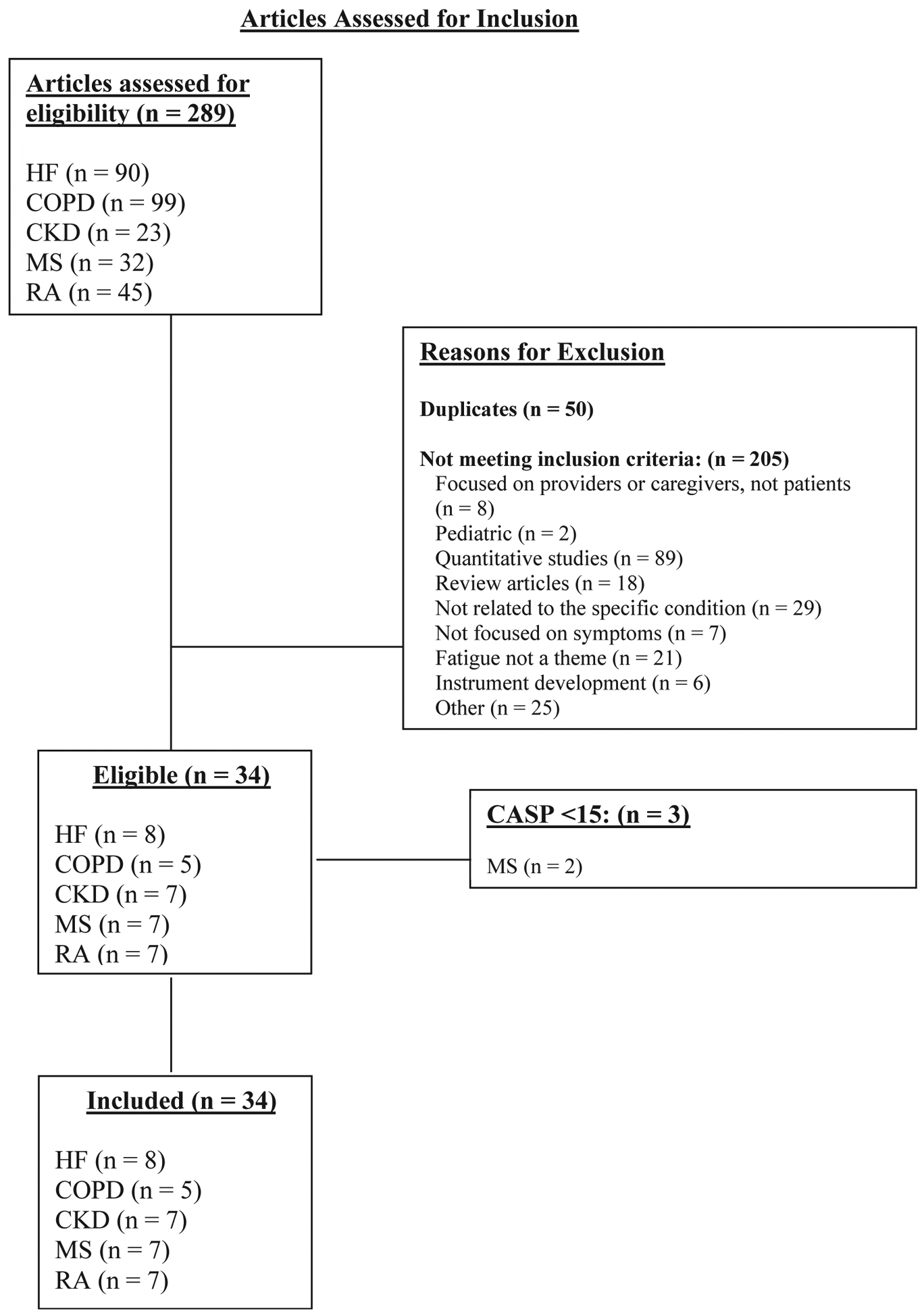

The search of the three databases yielded a total of 289 articles for review (Fig. 1). After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, we accepted eight articles for HF, seven articles for MS, seven articles for RA, seven articles for CKD, and five articles for COPD for a total of 34 studies included in the synthesis. A total of 865 participants were included across the studies (HF [n = 306], MS [n = 88], RA [n = 148], CKD [n = 185], and COPD [n = 138]). Some studies included numerous quotes, and some also organized the findings into broad themes.

Fig. 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of articles assessed for inclusion.

HF = heart failure; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD = chronic kidney disease; MS = multiple sclerosis; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; CASP = Critical Appraisal Skills Program.

Study Characteristics

The 34 articles included were published between 2008 and 2018. These studies were conducted in 12 different countries, including the U.S. (n = 9), Sweden (n = 5), The Netherlands (n = 5), Australia (n = 3), the U.K. (n = 3), Ireland (n = 2), Denmark (n = 1), Iran (n = 1), and Egypt (n = 1), Jordan (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), Japan (n = 1). Most of these studies were purely qualitative studies (n = 30), three were mixed-method studies, and one used a pluralist methodological approach. Qualitative methodologies included exploratory, descriptive, interpretive, and phenomenological approaches. Sampling strategies were identified as purposive, convenience, and consecutive; two studies did not name the sampling strategy. Sample sizes ranged from 10 to 77 participants. Study characteristics are reported in Table 2. Data were collected through individual semistructured interviews, conversational interviews, concept elicitation interviews, hierarchical interview schemes, in-depth interviews, telephone interviews, and focus groups. The data were analyzed with thematic analysis, content analysis, iterative analysis, interpretive methods, grounded theory methods, hermeneutic analysis, Krippendorff analysis, and framework analysis. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the 34 included articles.

Metasummaries

The experience of fatigue was examined in each individual condition. Each reviewer synthesized the findings related to the experience of fatigue in their respective chronically ill patient population.

Heart Failure.

Eight articles met our inclusion criteria and addressed fatigue in adults with HF. Most of these articles described general symptoms, but two articles specifically addressed fatigue.15,16 In general, fatigue was described primarily as lethargy and a reduced ability to engage in activity. Fatigue in HF was most commonly described as a severe lack of energy15–22 (…you just don’t have the energy … you see that you should clean, but …) and feebleness.15 Sleep was not sufficient to overcome the fatigue,15,23 and in some patients, a diurnal pattern was evident, with fatigue worse in the morning.15 The severity of fatigue resulted in difficulties with routine tasks and daily activities15, 17–19,21–23 (I can’t sweep, mop or run the vacuum cleaner. I get totally exhausted).18 Although fatigue affected multiple aspects of people living with HF, patients reported that others did not understand the extent and debilitating nature of their fatigue (It’s difficult when people of all ages look at me and laugh and they don’t recognize that I have a health issue … it’s just, I’m a fat slob. That disturbs me. So I get depressed), often pushing them to perform at an impossible level (The doctors want me to walk around. I just can’t do it).20–22

Symptoms of depression and breathlessness were closely related to fatigue.15,17,23 As one patient de scribes, depression like fatigue deeply disrupted their daily lives, When the blues come, I stay in bed and wait for it to pass. I don’t do anything … the pills don’t work; why take them. sometimes it doesn’t pass ….17 In addition, fatigue in HF was closely connected to breathlessness; seemingly easy activities like hair washing caused breathlessness and fatigue (my entire body quite simply gives out … and I get short of breath … when I bend over like this).15

Multiple Sclerosis.

Seven articles met inclusion criteria and examined fatigue in patients with MS.4,11,12,24–28 Fatigue was described as feeling very tired and lethargic11,12,24–28 … the days are becoming a lot more lethargic, just spending more time in bed and less time up ….12 Patients described how they felt fatigue that was similar to running out of batteries,25 feeling wiped out, and drained.26 Fatigue resulted in patients having difficulty with their daily activities, as evidenced by this patient’s description: It was not very easy for me to clean my home at once without feeling fatigue … I must divide the work and take rest intervals in between. Even with rests I feel so tired.24 Others described having an attack of fatigue.28 One person’s fatigue was so debilitating that they could not physically get up to go the bathroom, When I cannot get up to go to the bathroom, I prepare diapers 2026 getting up is torture.25

Participants also described feeling misunderstood, When I went to an art museum, I got tired and became unable to walk. Because I looked so healthy, [others] didn’t quite understand. I said “Could you lend me a hand?” But, it took quite a bit [of time until I was understood]. I should have said “pain” rather than “fatigue”, but I wasn’t understood.25 Another participant described, It’s just general ignorance, if they’re not aware of it or they haven’t heard of the fatigue involved … And they sort of say, ‘Oh yes, I know, I get so tired’ and I think, ‘How annoying. You know, no you don’t, YOU DON’T!28 Many also expressed feeling misunderstood by their health care providers, admitting that they managed their fatigue without help from their medical team, Even if I talk with the doctor, she/he tells me: “I wonder about that.” Lately, I don’t even mention [fatigue].25

The fatigue of MS is unpredictable, often is accompanied by other symptoms, and profoundly affects all aspects of the patient’s life including work, home, and social interactions.12,24–26,28 One person said, The unpredictable fatigue, walking difficulties, and balance disturbances are affecting my life tremendously.24 One man said, I was a very social man, and suddenly everything has changed. My social life has changed a lot.24 Others experienced cognitive issues with the fatigue: … the cognitive [fatigue] is just the most distressing ….26

Rheumatoid Arthritis.

Seven articles containing descriptions of fatigue in people with RA were included.4,29–34 Fatigue was described as omnipresent, uncontrollable, and overwhelming.4,31 Fatigue was depicted as severe and prioritized as one of their most distressing symptoms, often as distressing or more distressing than pain.4,24 Descriptions of fatigue explored its profound multidimensional effects (e.g., encompassing physical severity, emotional fatigue, and cognitive fatigue). Physical fatigue was described by a patient as I feel that my body is broken and every movement is as if I was moving a mountain.32 Another described how fatigue impacted their ability to socialize Every time I’m going to go somewhere, I’d rather go to bed and sleep.30 Despite its severe impact, fatigue was not well understood and/or largely ignored by clinicians.29,30,33

People with RA also described feeling misunderstood and how this led to feelings of social isolation and depression.29–31,33 One participant described how their family and friends did not fully grasp the profoundness of their fatigue, They can somehow understand [fatigue] intellectually, but you still know that they have not really understood what I’m talking about.35 Another described how their clinicians did not inquire about fatigue or understand how to treat it, Nobody says “what are you doing for the fatigue?” The health professionals don’t understand how to treat it either.29

Pain and cognitive decline were among the most common co-occurring symptom with fatigue in RA. Pain not only co-occurred but also exacerbated fatigue, Whenever I am in constant pain, I think that’s what makes me feel tired.31 People with RA also associated fatigue with a loss of cognitive function, I can’t remember people’s names or phone numbers. Like the password for my computer. and it’s just when I’m tired, it’s pure tiredness.29 Another symptom co-occurring with fatigue in RA was a sensory experience of heaviness, illustrated in these quotes: My legs become very heavy and I have to sit down, just doing nothing ….34 When I have fatigue, my body is wooden and I move with difficulty.32 It feels like I am carrying two buckets of water all the time.4 It feels like there’s porridge in my veins instead of blood.29

Chronic Kidney Disease.

Seven articles examining fatigue in people with CKD met our inclusion criteria.36–42 Fatigue was identified among the most common and impactful symptoms of patients with moderate-to-severe CKD.36–42 Fatigue was described as a prolonged tiredness or lack of energy that severely impacted QoL.36,39 As one person described, [fatigue] for me is having sudden moments without having any energy and without being able to do anything ….39 Physical manifestations included muscle weakness (My muscles are weak. After dialysis, I feel sick and have muscle cramps, my legs become weak …)37 and reduced mobility (there’s dishes in the sink because I didn’t have the energy to put the dishes away yet … If I’m folding laundry, I get really exhausted, so I have to stop and lay down). People with CKD also described mental fatigue including despair, which often triggered by their physical decline and making it difficult for them to communicate and socialize with others, It’s [illness] tiredness that caused by inactivity when your brain is muddled and your legs not working properly and you’ve got cramps.42 Another patient described their reduced interest in social behaviors because of their mental fatigue, sometimes, my friends call and I don’t like to answer them. [Instead, I] ask my mother to tell them I am not around. Because I am tired, weak, and sick and I have no patience for anybody.37

Another element that contributed to isolation and negative emotions was the perception that their fatigue was misunderstood by both family and friends (I don’t think they really know the inside of the fatigue … I don’t think that emotionally-wise and mentally-wise they know how I feel) and clinicians (The nephrologist is just looking at you when you explain your fatigue. And the only thing he does, is telling you: ‘It doesn’t fit with your GFR: it doesn’t fit’).39 Another patient described not only feeling misunderstood but also feeling ignored and judged, People don’t realize the impact of having this disease. They tend to ignore it and I think they see me as someone who fakes it.39

Fatigue was accompanied by other symptoms, including pruritus, sleep disturbances, and cognitive impairments. People with CKD associated their fatigue with sleep disturbances induced by pruritus, This itching … it’s worse at night. You’re trying to sleep with nothing else to think about, and it just takes over.41 Cognitive impairments, an inability to focus, forgetfulness, and decreases in attention span were also reported, My wife tells me I have to lay down because I don’t react as expected and I cannot find the appropriate words, I lose my concentration.42

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

Five articles met inclusion criteria and explored the experience of fatigue in adults with COPD.43–47 Fatigue was described as a severe chronic lack of energy43–45 (… you do not have any spark or energy to do things) and total exhaustion.43–45,47 Fatigue was associated with an inability to perform physical and social activities43–47 (you cannot do anything anymore).43 Overall, fatigue profoundly impacted both physical and mental aspects of daily life and contributed to a decreased QoL in patients with COPD.

People with COPD often experienced physical symptoms, including loss of appetite, sleep disturbances, and breathlessness. As one person described, I know I’m eating less. because I’m more tired. The ability to prepare meals was compromised (… you have to think ahead to have food that can be prepared very quickly).47 People with COPD commonly associated fatigue with sleep disturbances. They coped with fatigue by lying down and resting,44 but no matter how much they slept, the feeling of fatigue was always present (… fatigue is controlling your life, if you are going to rest or not).45 People with COPD often associated breathlessness with fatigue. Many attributed their fatigue to their underlying disease, COPD, and associated worsening fatigue with breathlessness, dyspnea, and oxygen deprivation.43,45,47

The daily limitations caused by fatigue led to a heavy mental burden or what some participants called mental fatigue. Fatigue caused feelings of loneliness,43 depression,43,44 worry,43,44,46 anxiety, anger, hopelessness, and a loss of joy in life and will to live (You do not just quit your life because you are tired, but sometimes it crosses my mind. It hurts so much that you cannot do anything anymore … What a bad life).45 Patients felt isolated because of their reduced ability to engage in social activity.

Furthermore, their feelings of social isolation and depression were exacerbated by feeling that their fatigue was misunderstood and ignored. Patients described not only feeling misunderstood but also feeling ignored by their doctor, the pulmonologist, he says very little. He never answers when you say that you are very tired. He completely ignores it.

Synthesis

After exploring fatigue as experienced by patients with various conditions, the findings were integrated to systematically identify shared and unique concepts and themes among the five chronically ill patient populations. One theme was running out of batteries. Across every condition, patients described severe lack of energy that was debilitating. Another theme was bad life. The intensity and magnitude of fatigue permeated all aspect of patients’ lives by challenging their physical and psychological well-being and leading to conflicting perceptions of intentions (what they needed/wanted to accomplish) vs. capacity (what they were actually able to accomplish). A third theme was associated symptoms. Fatigue was often accompanied by a variety of other symptoms, which exacerbated the profound negative impact of fatigue. A final theme was feeling misunderstood. Health care professionals and loved ones failed to understand the debilitating nature of the fatigue. Patients felt that they were viewed as malingerers, which caused them to experience social isolation and depression. Table 4 summarizes the contribution of each study to these four themes.

Running Out of Batteries.

Fatigue was consistently described as a persistent overwhelming feeling of tiredness, severe lethargy, or lack of energy, physical weakness, and cognitive decline, which were often unpredictable. Many participants described feeling like they had a limited amount of energy—like a battery that runs out of energy—they described needing to plan and restructure their lives to conserve their energy. Fatigue was described as a loss of this limited energy, which severely debilitated participants living with chronic conditions.

Bad Life.

Across conditions, patients reported that fatigue restricted their ability to engage in physical and social activities. The physical experience of fatigue made it difficult to walk, complete household chores, shop, and participate in leisure and self-care activities. The discrepancy between their intent and their decline in physical ability caused many to feel a loss of independence and left them feeling discouraged and guilty for requiring assistance. The unpredictability of the severity of their fatigue further contributed to feelings of loss of control and self-governance.

In causing a loss of physical ability and independence, fatigue decreased people’s ability to participate in social activities, leading to feelings of social isolation and depression. Patients reported missing family celebrations and social gatherings with friends because of their inability to travel or predict and consequently adequately prepare for fatigue. Patients described feeling depressed about not being able to participate in social activities because of extreme fatigue.

Associated Symptoms.

Patients across all five chronic conditions reported numerous symptoms that contributed to the profound negative effects of fatigue. The physical symptoms that co-occurred with fatigue in more than one study and in most of the five conditions were low endurance, decreased mobility, and sleep disturbances. Cognitive decline, including memory problems, poor concentration, and impaired cognition were also described. The most commonly reported psychological symptom was depression or sadness. A wide variety of other symptoms were noted in the various patient populations, but these symptoms were unique to specific conditions (e.g., pruritus in CKD, early satiety in COPD, pain in RA).

Feeling Misunderstood.

Across all five conditions, people perceived that friends, family members, health care professionals, and even strangers did not understand their fatigue. This lack of understanding negatively impacted their psychosocial well-being. The dissonance between the magnitude of their experience of fatigue and the lack of visible signs led many to fear that their friends and family members would not believe them and would perceive their fatigue as an excuse or laziness. As a result, some patients tried to hide their feelings from others. Patients also spoke of the difficulty they had explaining their fatigue to health care professionals. People experiencing fatigue described that the providers could not understand their fatigue, especially if their self-report of fatigue was more severe than the objective clinical indicators of their illness. Together, the four themes (running out of batteries, bad life, associated symptoms, and feeling misunderstood) captured the intensity, magnitude, and severity of fatigue, which profoundly impacted QoL across the five conditions.

Discussion

Identifying and examining similarities and differences in fatigue experienced across multiple conditions can help in better understanding the nature of fatigue to help guide the evaluation and management of fatigue. We performed a qualitative metasynthesis to explore the experience of fatigue in five noninfectious chronic conditions; HF, MS, RA, CKD, and COPD. We found themes that were shared across these conditions, running out of batteries, a bad life, associated symptoms, and feeling misunderstood. Our metasynthesis highlighted that fatigue is a common symptom across multiple chronic conditions and has severe negative impacts on patients’ QoL.

Our results are consistent with prior qualitative studies examining the experience of fatigue in individual disease processes and the only prior study we found that compared the experience of fatigue across chronic conditions. Whitehead et al.3 described the experience of fatigue across long-term conditions in a qualitative metasynthesis. However, multiple studies (22 of 58) and many participants (576 of 1153) included in their review had cancer-related fatigue. Our results build on their findings by focusing on noncancer-related fatigue. Importantly, the themes, running out of batteries and a bad life, were consistent with the description of fatigue by Whitehead et al. as occurring with an intensity that was overwhelming. Whitehead et al. also noted that people with fatigue perceived that others failed to understand their experience.

A major difference between the study by Whitehead et al.3 and our metasynthesis is that we found that associated symptoms accompanied and/or exacerbated fatigue. Whitehead et al.3 commented that fatigue was not typically linked with other symptoms. As the review by Whitehead et al. focused on cancer-related fatigue and other chronic conditions not included in our study, it is possible that fatigue’s association with other symptoms is unique to specific disease processes. Further research is needed to discern if fatigue is strongly associated with other symptoms and whether this phenomenon is consistent across other chronic conditions.

We found that family, friends, health care providers, and even strangers had difficulty understanding the profound impact of fatigue on psychosocial well-being. The responses of family and friends may be influenced by that of clinicians, and as Lian and Robson48 noted health care professionals often respond to medically unexplained symptoms such as fatigue with disbelief, inappropriate psychological explanations, marginalization of experiences, disrespectful treatment, lack of physical examination, and damaging health advice. Others have noted that patients are often not even asked about fatigue by their health care professionals.49 Failure to acknowledge fatigue undermines patients’ experiences, contributes to family members/friends’ misunderstanding of fatigue, and, as described by patients across these five chronic conditions, contributes to feelings of social isolation and depression.

Implications

The profound impact of fatigue is universally identified across the studies included in this review. Health care professionals need to validate the impact of fatigue on patients’ QoL. Evaluating and managing fatigue must become a priority because it has significant effects on physical and mental health. Furthermore, patients and their loved ones should receive information that recognizes and legitimizes the impact of fatigue. Doing so would validate patients’ experience of fatigue and empower patients and families by allowing them to prepare for and deal with potential challenges. Although the ultimate goal is identification of effective treatments that limit fatigue, it is premature to propose interventions. This metasynthesis illustrates the similarity of the descriptions across five chronic conditions, which could suggest that there are common biological mechanisms of fatigue underlying the phenomenon across these conditions. Research comparing and contrasting biological mechanisms across these conditions is needed to examine this possibility.

Future qualitative studies could contribute to our understanding of fatigue and thus aid in developing more accurate and consistent methods of evaluating and managing fatigue within and across conditions. Identifying common elements of the fatigue experience across conditions could suggest generic therapeutic intervention targets, whereas differences could reveal mechanisms unique to a disease process and help identify individualized interventions. Future studies should also test whether treating co-occurring symptoms influence fatigue and whether focused treatment of fatigue is sufficient to improve QoL.

Limitations and Strengths

Our integration and synthesis of existing studies was dependent on the authors’ interpretations of their qualitative data sets. The authors’ personal experiences guided their interpretation of the qualitative data, and there may be themes that were not identified by the authors. In addition, few of the qualitative studies reported details about the different stages of treatment, time since diagnosis, or comorbid conditions. Some studies failed to report the exact number of men and women or the average age of participants, so we are not able to describe the sample fully. Examining fatigue in other illness groups could capture more robust and representative depictions of fatigue. Strengths of our metasynthesis include that it is one of only two studies comparing the experience of fatigue across chronic conditions and the only one to focus on noncancer-related fatigue.

Conclusion

Fatigue is a common symptom across chronic conditions that has a profound impact on patients’ QoL. The severe energy depletion described by patients, the negative and life-altering impact of fatigue, treatment of co-occurring symptoms, and validation of the experience of fatigue are important to consider when establishing a plan of care for patients with HF, MS, RA, CKD, and COPD. Addressing these challenges is an important step to improving the QoL of people experiencing fatigue while living with chronic conditions.

Key Message.

This metasynthesis explored patients’ experiences of fatigue in heart failure, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Fatigue was characterized by severe energy depletion, was associated with other symptoms, and misunderstanding of fatigue by others decreased psychosocial well-being. Evaluating and managing fatigue must become a priority as it affects physical and mental health.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

The authors thank Christine Bradway, PhD, CRNP, Victoria V. Dickson, PhD, CRNP, and Sarah H. Kagan, PhD, RN, for providing guidance on qualitative research and appraisal. They also acknowledge Richard James and Sherry Morgan from the University of Pennsylvania Biomedical Library for providing assistance with the development of the search strategy and database searches. Support provided by the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services to R. B. J.-L. who received Postdoctoral Intramural Research Training Award. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.McSweeney JC, Cody M, O’Sullivan P, et al. Women’s early warning symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2003;108:2619–2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap Cooperative Group during its first two years. Med Care 2007;45:S3–S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitehead LC, Unahi K, Burrell B, Crowe MT. The experience of fatigue across long-term conditions: a qualitative meta-synthesis. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;52: 131–143.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomsen T, Beyer N, Aadahl M, et al. Sedentary behaviour in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2015;10:28578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matura LA, Malone S, Jaime-Lara R, Riegel B. A systematic review of biological mechanisms of fatigue in chronic illness. Biol Res Nurs 2018;20:410–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. WHOQOL: Measuring quality of life: World Health Organization. Available from https://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whoqol-qualityoflife/en/. Accessed November 17, 2019.

- 7.Ludvigsen MS, Hall EO, Meyer G, et al. Using Sandelowski and Barroso’s meta-synthesis method in advancing qualitative evidence. Qual Health Res 2016;26:320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Toward a metasynthesis of qualitative findings on motherhood in HIV-positive women. Res Nurs Health 2003;26:153–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York: Springer Publishing Company, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Finding the findings in qualitative studies. J Nurs Scholarsh 2002;34:213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lohne V, Aasgaard T, Caspari S, Slettebø Å, Nåden D. The lonely battle for dignity: individuals struggling with multiple sclerosis. Nurs Ethics 2010;17:301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kayes NM, McPherson KM, Schluter P, et al. Exploring the facilitators and barriers to engagement in physical activity for people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 2011; 33:1043–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon-Woods M, Sutton A, Shaw R, et al. Appraising qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a quantitative and qualitative comparison of three methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007;12:42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh D, Downe S. Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs 2005;50:204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagglund L, Boman K, Lundman B. The experience of fatigue among elderly women with chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2008;7:290–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones P, Harding G, Wiklund I, Berry P, Leidy N. Improving the process and outcome of care in COPD: development of a standardised assessment tool. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:208–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickson VV, McCarthy MM, Katz SM. How do depressive symptoms influence self-care among an ethnic minority population with heart failure? Ethn Dis 2013;23:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gwaltney CJ, Slagle AF, Martin M, Ariely R, Brede Y. Hearing the voice of the heart failure patient: key experiences identified in qualitative interviews. Br J Cardiol 2012;19:25. e1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jurgens CY, Hoke L, Byrnes J, Riegel B. Why do elders delay responding to heart failure symptoms? Nurs Res 2009;58:274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holden RJ, Schubert CC, Mickelson RS. The patient work system: an analysis of self-care performance barriers among elderly heart failure patients and their informal care-givers. Appl Ergon 2015;47:133–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norberg EB, Lofgren B, Boman K, Wennberg P, Brannstrom M. A client-centred programme focusing energy conservation for people with heart failure. Scand J Occup Ther 2017;24:455–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsh A, Kitko L, Hupcey J. The experiences of younger individuals living with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2018; 33:E9–E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones J, McDermott CM, Nowels CT, Matlock DD, Bekelman DB. The experience of fatigue as a distressing symptom of heart failure. Heart Lung 2012;41:484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Sharman AJ, Khalil H, Nazzal M, et al. Living with multiple sclerosis: a Jordanian perspective. Physiother Res Int 2018;23:e1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moriya R, Kutsumi M. Fatigue in Japanese people with multiple sclerosis. Nurs Health Sci 2010;12:421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newland PK, Thomas FP, Riley M, Flick LH, Fearing A. The use of focus groups to characterize symptoms in persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs 2012;44:351–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barlow J, Edwards R, Turner A. The experience of attending a lay-led, chronic disease self-management programme from the perspective of participants with multiple sclerosis. Psychol Health 2009;24:1167–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turpin M, Kerr G, Gullo H, et al. Understanding and living with multiple sclerosis fatigue. Br J Occup Ther 2018;81:82–89. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Connolly D, Fitzpatrick C, O’Toole L, Doran M, O’Shea F. Impact of fatigue in rheumatic diseases in the work environment: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:13807–13822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldthusen C, Bjork M, Forsblad-d’Elia H, Mannerkorpi K, University of Gothenburg Centre for Person-Centred Care. Perception, consequences, communication, and strategies for handling fatigue in persons with rheumatoid arthritis of working ageda focus group study. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:557–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minnock P, Ringner A, Bresnihan B, et al. Perceptions of the cause, impact and management of persistent fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis following tumour necrosing factor inhibition therapy. Musculoskeletal Care 2017;15: 23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mortada M, Abdul-Sattar A, Gossec L. Fatigue in Egyptian patients with rheumatic diseases: a qualitative study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikolaus S, Bode C, Taal E, van de Laar MA. New insights into the experience of fatigue among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:895–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Repping-Wuts H, Uitterhoeve R, van Riel P, van Achterberg T. Fatigue as experienced by patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA): a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:995–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feldthusen C, Grimby-Ekman A, Forsblad-d’Elia H, Jacobsson L, Mannerkorpi K. Explanatory factors and predictors of fatigue in persons with rheumatoid arthritis: a longitudinal study. J Rehabil Med 2016;48:469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cox KJ, Parshall MB, Hernandez SHA, Parvez SZ, Unruh ML. Symptoms among patients receiving in-center hemodialysis: a qualitative study. Hemodial Int 2017;21:524–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kazemi M, Nasrabadi AN, Hasanpour M, Hassankhani H, Mills J. Experience of Iranian persons receiving hemodialysis: a descriptive, exploratory study. Nurs Health Sci 2011;13:88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monaro S, Stewart G, Gullick J. A ‘lost life’: coming to terms with haemodialysis. J Clin Nurs 2014;23:3262–3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schipper K, van der Borg WE, de Jong-Camerik J, Abma TA. Living with moderate to severe renal failure from the perspective of patients. BMC Nephrol 2016;17:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yngman-Uhlin P, Friedrichsen M, Gustavsson M, Fernstrom A, Edell-Gustafsson U. Circling around in tiredness: perspectives of patients on peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Nurs J 2010;37:407–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Picariello F, Moss-Morris R, Macdougall IC, Chilcot J. ‘It’s when you’re not doing too much you feel tired’: a qualitative exploration of fatigue in end-stage kidney disease. Br J Health Psychol 2018;23:311–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pugh-Clarke K, Read SC, Sim J. Symptom experience in non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease: a qualitative descriptive study. J Ren Care 2017;43:197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kouijzer M, Brusse-Keizer M, Bode C. COPD-related fatigue: impact on daily life and treatment opportunities from the patient’s perspective. Respir Med 2018;141:47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paap MC, Bode C, Lenferink LI, et al. Identifying key domains of health-related quality of life for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the patient perspective. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2014;12:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stridsman C, Lindberg A, Skar L. Fatigue in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative study of people’s experiences. Scand J Caring Sci 2014;28:130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wortz K, Cade A, Menard JR, et al. A qualitative study of patients’ goals and expectations for self-management of COPD. Prim Care Respir J 2012;21:384–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shalit N, Tierney A, Holland A, et al. Factors that influence dietary intake in adults with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Diet Assoc 2016;73:455–462. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lian OS, Robson C. “It’s incredible how much I’ve had to fight.” Negotiating medical uncertainty in clinical encounters. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2017;12:1392219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katz P Fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2017;19:25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]