Abstract

Superoxide radical (O2•–) is involved in numerous physiological and stress processes in higher plants. Fruit ripening encompasses degradative and biosynthetic pathways including reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. With the use of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) fruits at different ripening stages and under a nitric oxide (NO)-enriched environment, the metabolism of O2•– was evaluated at biochemical and molecular levels considering the O2•– generation by a NADPH oxidase system and its dismutation by superoxide dismutase (SOD). At the biochemical level, seven O2•–-generating NADPH-dependent oxidase isozymes [also called respiratory burst oxidase homologs (RBOHs) I–VII], with different electrophoretic mobility and abundance, were detected considering all ripening stages from green to red fruits and NO environment. Globally, this system was gradually increased from green to red stage with a maximum of approximately 2.4-fold increase in red fruit compared with green fruit. Significantly, breaking-point (BP) fruits with and without NO treatment both showed intermediate values between those observed in green and red peppers, although the value in NO-treated fruits was lower than in BP untreated fruits. The O2•–-generating NADPH oxidase isozymes I and VI were the most affected. On the other hand, four SOD isozymes were identified by non-denaturing electrophoresis: one Mn-SOD, one Fe-SOD, and two CuZn-SODs. However, none of these SOD isozymes showed any significant change during the ripening from green to red fruits or under NO treatment. In contrast, at the molecular level, both RNA-sequencing and real-time quantitative PCR analyses revealed different patterns with downregulation of four genes RBOH A, C, D, and E during pepper fruit ripening. On the contrary, it was found out the upregulation of a Mn-SOD gene in the ripening transition from immature green to red ripe stages, whereas a Fe-SOD gene was downregulated. In summary, the data reveal a contradictory behavior between activity and gene expression of the enzymes involved in the metabolism of O2•– during the ripening of pepper fruit. However, it could be concluded that the prevalence and regulation of the O2•– generation system (NADPH oxidase-like) seem to be essential for an appropriate control of the pepper fruit ripening, which, additionally, is modulated in the presence of a NO-enriched environment.

Keywords: NADPH oxidase, nitric oxide, nitration, pepper fruit, respiratory burst oxidase homolog, S-nitrosation, superoxide dismutase, ripening

Introduction

Fruit ripening is a genetically coordinated developmental process that involves important physiological and biochemical changes affecting their organoleptic properties such as color, flavor, aroma, texture, and nutritional quality (Giovannoni, 2001; Osorio et al., 2013; Karlova et al., 2014). The ripening process occurs naturally when the fruits are in the plant, but it can also take place during the period of postharvest and storage especially in those types of fruits whose ripening depends on ethylene (climacteric fruits), such as tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.), custard apple (Annona squamosa L.), banana (Musa spp.), or mango (Mangifera indica L.).

Pepper (Capsicum spp.) fruit, a non-climacteric one, belongs to the Solanaceae family, which includes other members such as tomatoes, potatoes, or eggplant. Fresh or processed pepper fruits are widely consumed around the world, so they have a great economic importance. Pepper fruit including many types and varieties differ in size, shape, color, and degree of pungency (hotness), being this last feature due to the presence of capsaicin (8-methyl-N-vanillyl-trans-6-nonenamide), and an alkaloid produced as a secondary metabolite. Furthermore, pepper fruits contain a high level of vitamin C and other vitamins such as A, E, B1, and B2 (Rodríguez-Ruiz et al., 2017). Pepper fruit ripening has an associated drastic change in color because the initial green color due to chlorophylls is progressively decomposed and is substituted by a different range of carotenoids including β-carotene, lutein, violaxanthin, capsanthin, violaxanthin, and zeaxanthin among others, which contribute to provide a variety of color (red, yellow, orange, purple/violet, etc.) in the ripe stage (Pascual et al., 2010; Gómez-García and Ochoa-Alejo, 2013; Ou et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2020). In fact, this variety of color and shape is even being used for ornamental purposes. In general, the main function of these carotenoids is the protection against oxidative damage because they can interact with singlet oxygen (1O2) as well as scavenger of peroxy radicals (LOOŢ), but also they are precursors of phytohormones such as abscisic acid (ABA) or strigolactones (Fanciullino et al., 2014).

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) are two families of molecules that are part of the physiological metabolism in all types of cells. Some of these molecules such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or nitric oxide (NO) have regulatory functions in many physiological processes including seed germination, plant growth and development, and senescence, but also these reactive species could be also overproduced under adverse environmental conditions being involved in nitro-oxidative processes (Corpas and Barroso, 2013). Recently, biochemical evidences support that both ROS and RNS interact and seem to be involved in fruit ripening (Tanou et al., 2015; Palma et al., 2015, 2019; Corpas et al., 2018; Corpas and Palma, 2018; Léchaudel et al., 2018; Rodríguez-Ruiz et al., 2019).

NADPH oxidase (NOX), also called respiratory burst oxidase homolog (RBOH), is one of the main enzymatic sources of superoxide radicals (O2•–) in plants (Sagi and Fluhr, 2006; Suzuki et al., 2011; Marino et al., 2012). RBOHs participate in a wide range of function including cellular signal transduction, cell growth and development, pollen germination and tube growth, stomatal movements, plant interaction with beneficial organism, plant defense against pathogens (Müller et al., 2009; Jiménez-Quesada et al., 2016, 2019; Qu et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Fonseca-García et al., 2019; Kaya et al., 2019). The number of RBOH genes reported thus far differs among the different plant species. Thus, 10 RBOH genes have been identified in the model plant Arabidopsis, nine in rice (Oryza sativa) (Wang et al., 2013; Kaur and Pati, 2018) and common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) (Montiel et al., 2012), eight in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) (Li et al., 2015) and seven in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa cv. Toyonaka) (Zhang et al., 2018), grape (Vitis vinifera) (Cheng et al., 2013), and pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). This diversity of RBOH genes suggests that the corresponding proteins could have specific function according to their organ location (root, stem, leaf, flower, or fruit), physiological stage (seedling or flowering plants), or environmental conditions.

Superoxide dismutases (SODs) are metalloenzymes that catalyze the disproportionation of O2•– into O2 and H2O2 and are associated with stress, development, and senescence conditions in plants (Houmani et al., 2016; del Río et al., 2018). Moreover, the type and number of SOD isozymes can differ between different plant species and their corresponding organs (Asada et al., 1973; Bridges and Salin, 1981; Almansa et al., 1989; Corpas et al., 1991, 2006; Pinilla et al., 2019). In preliminary studies, the presence of four SOD and seven O2•–-generating NOX isozymes, which seemed to be differentially regulated during ripening in different sweet pepper cultivars, was reported (Mateos et al., 2013; Chu-Puga et al., 2019). Moreover, additional research has identified and characterized other enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems in pepper fruit (Jiménez et al., 2003; Mateos et al., 2009; Martí et al., 2009, 2011; Camejo et al., 2015; Chiaiese et al., 2019; Rodríguez-Ruiz et al., 2019; Ribes-Moya et al., 2020). With the goal to get a deeper knowledge of the physiological function and the regulation of the O2•– metabolism in the ripening of sweet pepper fruit, biochemical and molecular approach-based in-gel activity assays and RNA-Seq/real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analyses were accomplished in fruits at different ripening stages and in the presence of a NO-enriched environment. The data provide differential profile between biochemical and molecular results; however, it can be concluded that during ripening of sweet pepper from green to red stage, there is a prevalence of O2•– generation, which seems to be negatively modulated in the presence of a NO-enriched environment.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Nitric Oxide Gas Treatment

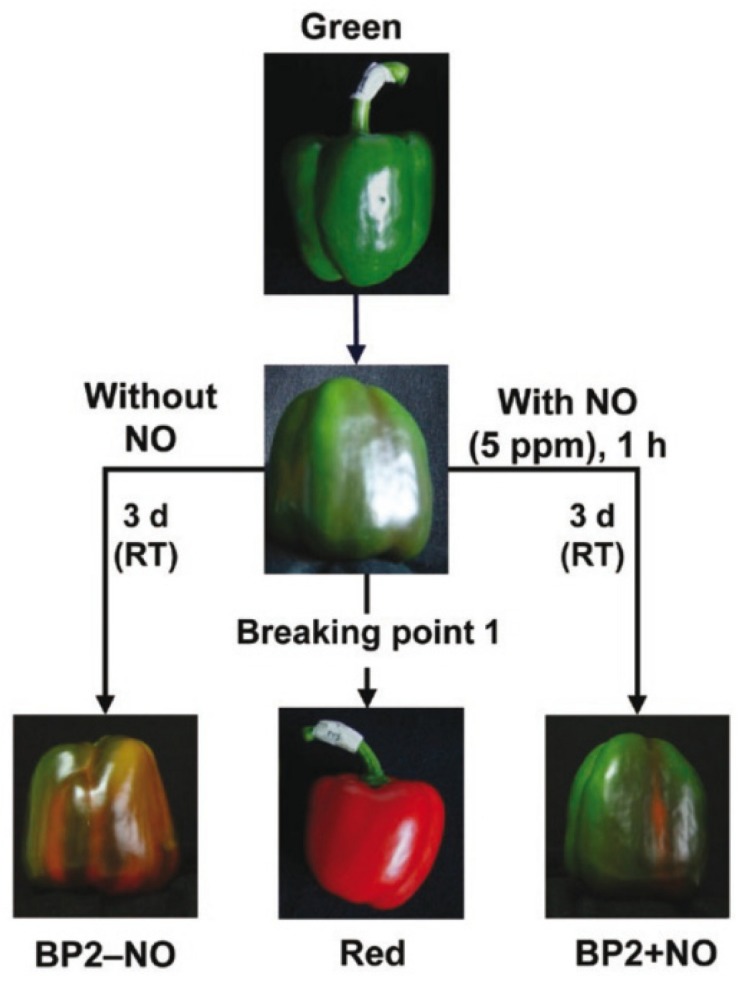

California-type sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L., cv. Melchor) fruits were collected at three different developmental stages – green immature (G), breaking point (BP1), and red ripe (R) – from plants grown in plastic-covered experimental greenhouses (Zeraim Iberica S.A./Syngenta Seeds, Ltd., El Ejido, Almería, Spain). Supplementary Figure S1 shows a typical distribution of fruits at the three stages mentioned above (G, BP, and R) in pepper plants. In addition, to study the exogenous NO gas effect on the fruit ripening, we set two additional groups: treated fruits with 5 ppm NO for 1 h (BP2 + NO) and another parallel group that was not treated with NO (BP2 − NO) (Palma et al., 2018; González-Gordo et al., 2019). After 3 days, all fruits from the five groups were chopped into small cubes (5 mm/edge), frozen under liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80°C until use. Figure 1 provides a comprehensive picture of the experimental design used in this study, which is based on a previous report (González-Gordo et al., 2019).

FIGURE 1.

Illustrative picture showing the experimental design used in this study with the representative phenotype of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) fruits at different stages and treatments: immature green, breaking point 1 (BP1), breaking point 2 without NO treatment (BP2 – NO), breaking point 2 with NO treatment (BP2 + NO), and ripe red. Fruits were subjected to a NO-enriched atmosphere (5 ppm) in a hermetic box for 1 h and were then stored at room temperature (RT) for 3 days. Reproduced with permission from González-Gordo et al. (2019).

Preparation of Pepper Samples for Biochemical Analyses

The pericarp of pepper fruits stored at −80°C of the different groups were ground under liquid nitrogen in an IKA A11 Basic mill and then dissolved in a ratio 1:1 (w/v) with 50 mM of Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, 0.1 mM of EDTA, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 5 mM of dithiothreitol (DTT). In all cases, pericarp samples were prepared from, at least, five fruits (biological replicates) at each stage and treatments. Homogenates were filtered through two layers of Miracloth and centrifuged at 27,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min. The supernatants were used for the enzymatic assays.

In-Gel Isozyme Profile of NADPH Oxidase and Superoxide Dismutase Activity Assays

Protein samples were separated using non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) on 6% acrylamide gels, and O2•–-generating NOX isozymes were visualized by a photochemical nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction method described previously (Airaki et al., 2012; Chu-Puga et al., 2019). Briefly, after the electrophoresis, the gels were incubated in the dark for 20 min in a reaction mixture solution containing 50 mM of Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4), 0.2 mM of NBT, 0.1 mM of MgCl2, and 1 mM of CaCl2. Subsequently, 0.2 mM of NADPH was added, and the appearance of the blue formazan bands was monitored. The reaction was stopped by immersing the gels in distilled water. As controls, gels were preincubated 30 min with 50 μM of diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), a specific inhibitor of NADPH-dependent O2•– generation activity (Leterrier et al., 2012).

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) isozymes were separated by non-denaturing PAGE on 10% acrylamide gels, and activity was localized in gels by the NBT reduction method with O2•– radicals generated photochemically (Beauchamp and Fridovich, 1971). To identify the type of SOD isozymes, the gels were preincubated separately at 25°C for 30–45 min in 50 mM of K-phosphate, pH 7.8, in the presence or absence of either 5 mM of KCN or 5 mM of H2O2. CuZn-SOD is inhibited by KCN and H2O2; Fe-SOD is inhibited by H2O2 but not by KCN, and Mn-SOD is not inhibited by either KCN or H2O2 (Corpas et al., 1998).

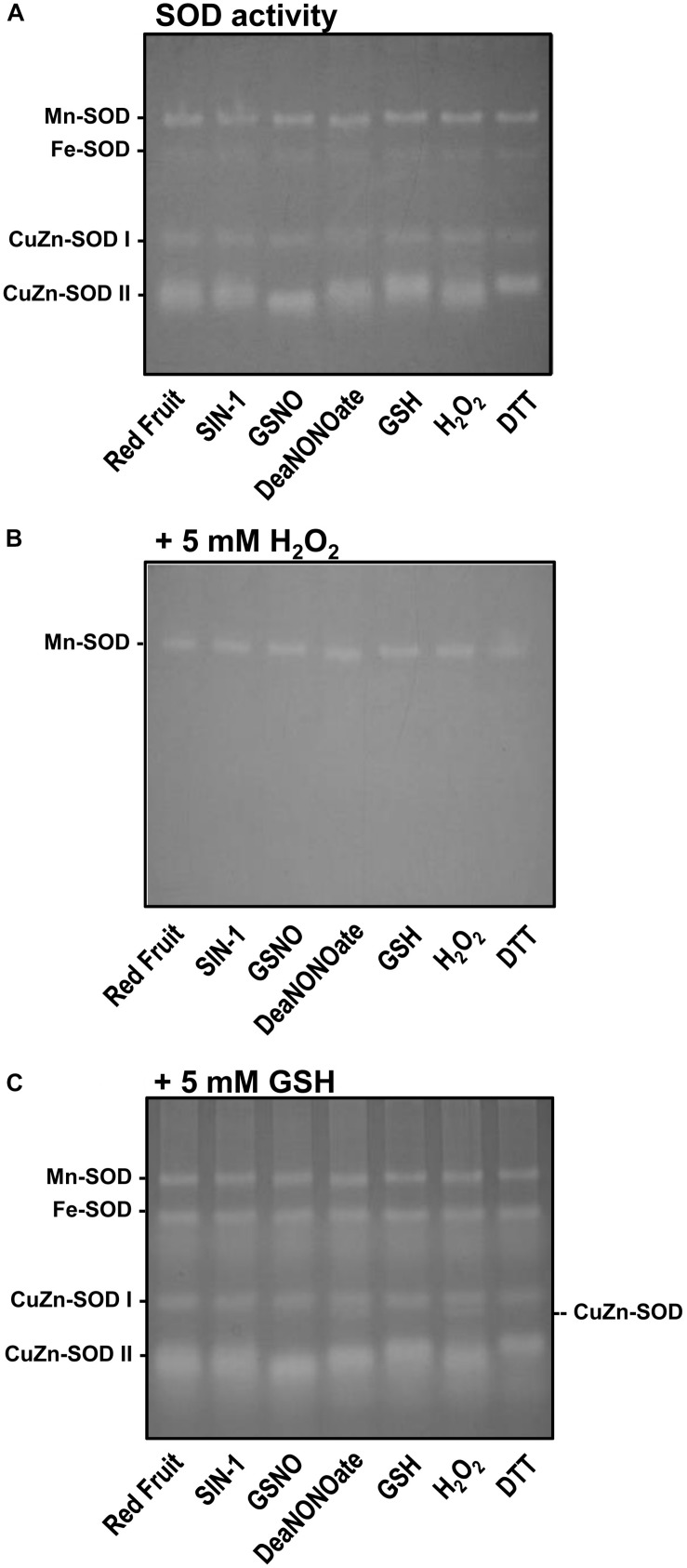

For the in vitro assay of the effect of some RNS and oxidizing/reducing agents on the isozyme SOD activity, pepper samples were preincubated with different chemicals including 4 mM of 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1), a peroxynitrite (ONOO–) donor, 4 mM of S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) and 4 mM of diethylamine NONOate (DEA NONOate) as NO donors, 10 mM of H2O2 as an oxidant; 4 mM of reduced glutathione (GSH), and 10 mM of DTT as reductants. All preincubations were done at 25°C for 2 h in the dark. Then, electrophoresis gels were stained for SOD activity as it has been previously described. In certain assays as those described in Figure 7, gels were preincubated for 30 min under dark conditions with either 5 mM of H2O2 or 5 mM of GSH before staining for SOD activity.

FIGURE 7.

Analysis on gel electrophoresis of the activity of the different superoxide dismutase (SOD) isozymes of red pepper fruit samples preincubated with different chemicals. (A) Samples were preincubated with 4 mM of SIN-1, 4 mM of GSNO, 4 mM of DEA NONOate, and 4 mM of GSH; 10 mM of H2O2; and 10 mM of DTT. After electrophoresis (acrylamide 8%), gels were stained for SOD activity. (B) Samples were processed as in panel (A), but the gel was preincubated with 5 mM of H2O2 before staining for SOD activity. (C) Samples were processed as in panel (A), but the gel was preincubated with 5 mM of GSH prior to SOD activity staining. The gel pictures are representative of those obtained from at least three biological replicas repeated three times.

Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Hercules, CA, United States), with bovine serum albumin as standard. Band intensity of RBOH isozymes was quantified using ImageJ 1.45 software1.

RNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from pepper fruits using a two-step method based on TRIzol® Reagent (Gibco BRL) and the RNAeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were prepared using an optimized Illumina protocol and were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq550 comprising four independent replicates belonging to the green stage and five to each of the other stages (González-Gordo et al., 2019). RNA (1 μg) was used for cDNA synthesis. It was added to a mixture containing 0.67 mM of dNTPs and 5 μM of oligo d(T)23VN in a volume of 15 μl. This mix was incubated 5 min at 65°C. Afterward, reaction buffer [75 mM of Tris-HCl, pH 9.0, 2 mM of MgCl2, 50 mM of KCl, and 20 mM of (NH4)2SO4], 1 U/μl of RnaseOUTTM (Invitrogen), and 10 U/μl of SuperScriptTM II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) were added in a final reaction volume of 20 μl. Finally, cDNA synthesis was performed at 42°C for 50 min, followed by an inactivation step of 15 min at 70°C.

In order to get our reference transcriptome and differentially expressed (DE) genes among the ripening stages and the NO treatment, we analyzed 24 biological replicates (4 × G, 5 × BP1, 5 × BP2 + NO, 5 × BP2 − NO, and 5 × R) and followed an optimized workflow to process all the data. Data processing involved several bioinformatic tools (TransFlow, Seoane et al., 2018 and DEgenes Hunter, González-Gayte et al., 2017), which apply different algorithms with their own statistical tests, to validate the whole experiment. The trends found in the expression patterns in the RNA-Seq experiments were confirmed by performing the real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) experiments.

Real-time quantitative PCR experiments were performed on a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) with QUANTIMIX HotSplit Easy kit (Biotools, B&M Labs, Madrid, Spain) following manufacturer’s instructions and using specific primers (see Supplementary Table S1). Actin and glyceraldehyde−3−phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used as housekeeping genes (Wan et al., 2011; Bin et al., 2012). Reactions were performed with an initial step at 95°C for 30 s and then cycled at 95°C for 1 min, 67°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 15 s for 40 cycles. Each PCR was performed at least three times (technical replicates), with three independent samples (biological replicates). Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2–ΔΔCt method (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008). A time-course expression analysis of RBOH and SOD genes constitutes a trustworthy visual representation of the expression values obtained by RNA-Seq.

Phylogenetic Analysis and Conserved Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homolog Protein Sequences

Alignment of plant RBOH proteins was performed using the ClustalW tool with default parameters. Then, a phylogenetic tree was generated using MEGA 7.0 and edited with Figtree software. Sequence logos of conserved motifs were created by WebLogo 3.

Statistical Analysis

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the statistical significance between relative expression values obtained using RT-qPCR. Post hoc comparisons of means were made by using a Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) test. Statistical significance was considered at the conventional 5% level (P ≤ 0.05). All calculations were performed using R Studio.

Results

The main goal of this study is to understand how O2•– metabolism is modulated during pepper fruit ripening with special focus in the activity of two groups of isozymes, O2•–-generating NOXs and the antioxidant SODs. Additionally, it was evaluated how these two enzymatic systems could be affected in the presence of a NO-enriched environment during the ripening of sweet pepper fruits.

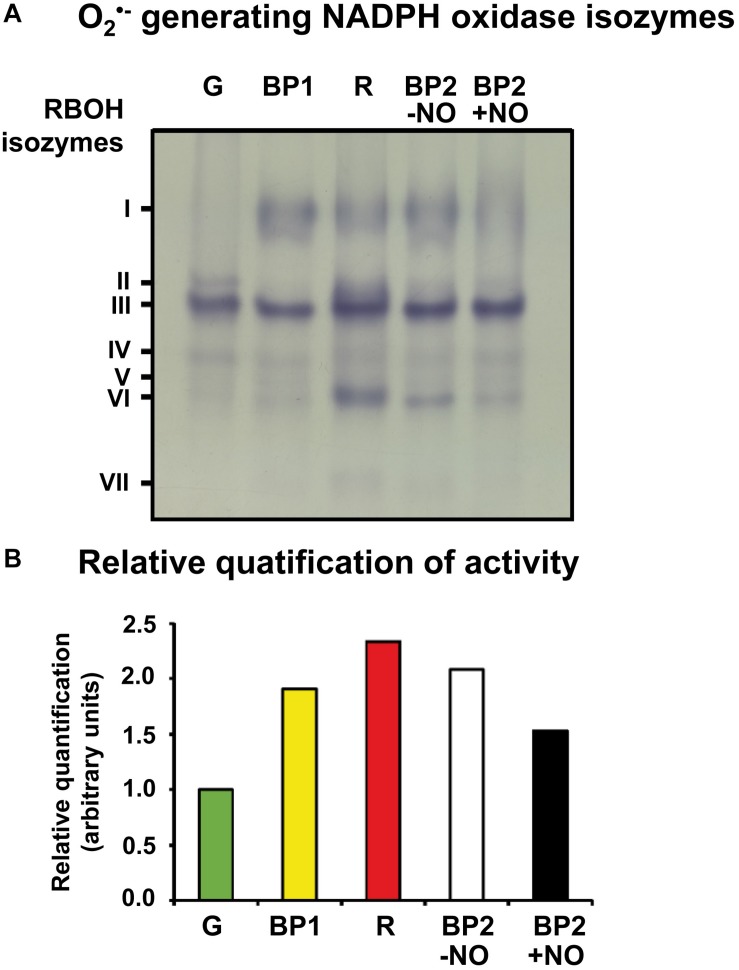

With the use of these group of samples, Figure 2A shows the O2•–-generating NOX isozymes profile of sweet pepper fruits at different stages of ripening: immature green, BP1, BP2 with and without NO (BP2 + NO and BP2 − NO, respectively), and red. Thus, a total of seven O2•–-generating NOX isozymes, with different electrophoretic mobility and abundance, were globally detected during the ripening from green to red fruits considering all the different stages and the NO treatment. They were designated as I to VII according to their increasing electrophoretic mobility. Supplementary Figure S2 illustrates the relative quantification of each O2•–-generating NOX isozyme in the analyzed ripening stages, with isozyme III being the most prominent in all ripening stages. Figure 2B shows the total relative quantification considering all the O2•–-generating NOX isozymes present in each ripening stages. Thus, a gradual increased activity was observed throughout ripening with a maximum of about 2.4-fold increase in red fruit compared with green fruit. Significantly, pepper fruits both with and without NO treatment (BP2 + NO and BP2 − NO) showed intermediate values to those observed for green and red peppers (Figure 2B), with the value in NO-treated fruits being lower than in untreated fruits. In this case, isozymes I and VI seemed to be the most affected.

FIGURE 2.

Activity (A) and relative quantification (B) of O2– -generating NADPH oxidase isozymes of sweet pepper fruits at different stages of ripening: immature green (G), breaking point 1 (BP1), breaking point 2 with and without NO treatment (BP2 + NO and BP2 – NO, respectively), and red ripe (R). Protein samples (25 μg per lane) were separated by non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE; 6% acrylamide), and activity was detected by the nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT)-reducing method. Isozymes were labeled I–VII (on the left) according to their increasing electrophoretic mobility. Comparative total band intensities in each lane were quantified using ImageJ 1.45 software (see Supplementary Figure S1 for details). The gel image is representative of those obtained from at least three biological replicas repeated three times.

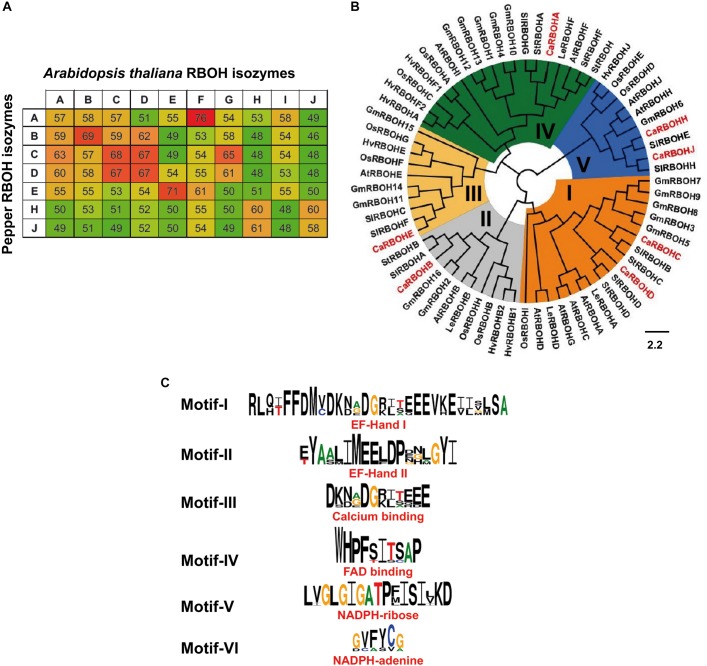

To get deeper knowledge about this O2•–-generating NOX isozymes during ripening, the identification of RBOH genes in the transcriptome of sweet pepper previously reported (González-Gordo et al., 2019) and their corresponding protein sequences were accomplished. With this information, one could make a comparative analysis of the percentage of identities among the protein sequences of the 10 Arabidopsis RBOH isozymes (A to J) with the seven identified sweet pepper RBOH isozymes because Arabidopsis thaliana provides the most complete information on this subject (Figure 3A). Considering the highest degree of protein identities with respect to the Arabidopsis RBOHs, the seven sweet pepper RBOH isozymes identified here were designated with letters A, B, C, D, E, H, and J.

FIGURE 3.

Analyses of sweet pepper respiratory burst oxidase homolog (RBOH) isozymes based on their protein sequences. (A) Percentage of protein sequence identity among the 10 Arabidopsis RBOH isozymes with the seven sweet pepper RBOH isozymes. High, intermediate, and low identities are shown as green, yellow, and red color, respectively. (B) Phylogenetic analysis and conserved regions of sweet pepper RBOH proteins. Maximum-likelihood tree of 67 plant RBOH protein sequences. Identified CaRBOH proteins are highlighted in red color. The scale bar represents the phylogenetic branch length. Different subgroups of RBOHs are depicted in different colors (I–V). Species abbreviations: At (Arabidopsis thaliana), Ca (Capsicum annuum), Gm (Glycine max), Hv (Hordeum vulgare), Ls (Lepidium sativum), Os (Oryza sativa), Sl (Solanum lycopersicum), and St (Solanum tuberosum). (C) Conservation of sequence motifs (I–VI) of sweet pepper RBOH protein sequences.

Figure 3B illustrates the phylogenetic comparative analysis among RBOH proteins from eight plant species including sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum), Arabidopsis thaliana, garden cress (Lepidium sativum), soybean (Glycine max), barley (Hordeum vulgare), rice (Oryza sativa), and two species of the Solanum genus: tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and potato (Solanum tuberosum). This allowed to identify five main RBOH groups designated as I to V, which are depicted with different colors in the diagram. CaRBOH A, reported in this work, was included in group IV, CaRBOH B was present in group II, CaRBOH C and D are in group I, CaRBOH E is in group III, and CaRBOH H and J are in group V. Figure 3C shows the identification of six conserved motifs of plant RBOHs present in sweet pepper RBOH protein sequences, which correspond to EF-Hand I and II, calcium and FAD binding, NADPH-ribose, and NADPH-adenine motifs, respectively.

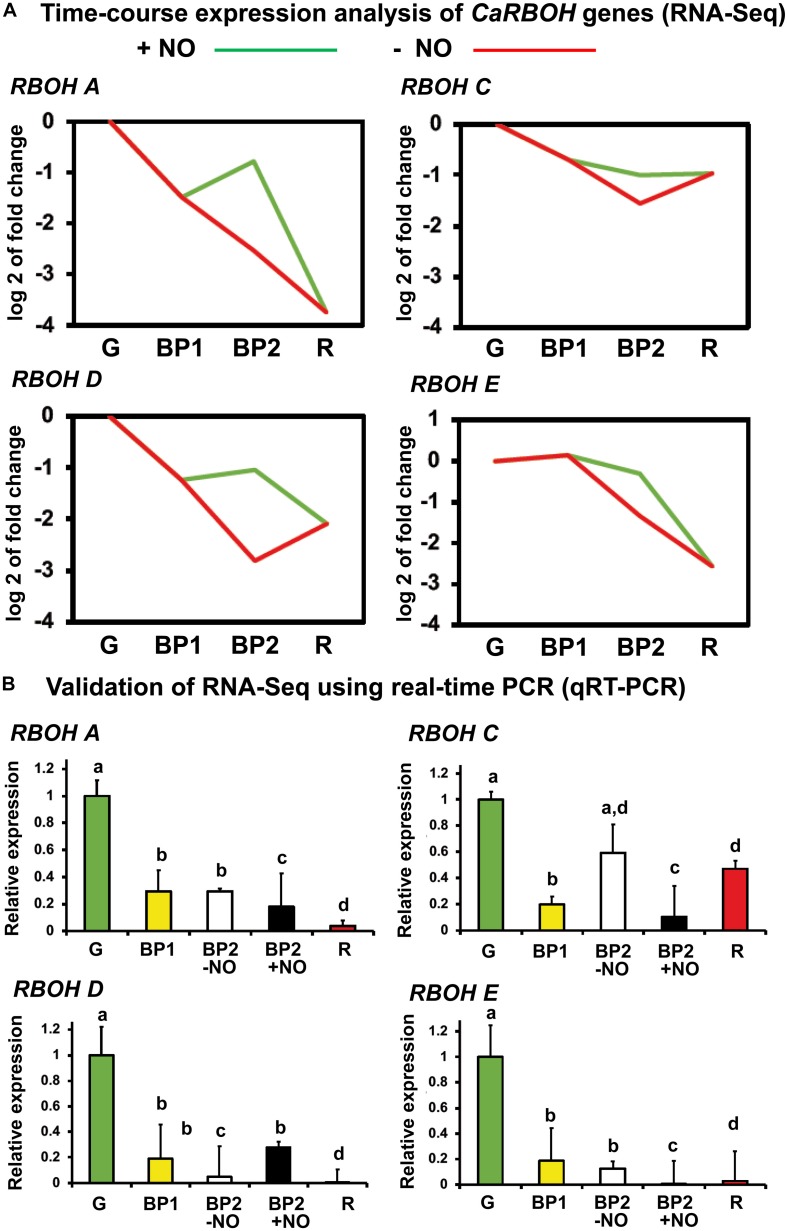

With the seven identified RBOH genes in the sweet pepper transcriptome (RNA-Seq) (González-Gordo et al., 2019), a time-course analysis was done, and among these seven genes, only the designated RBOH A, C, D, and E were found to show expression changes in our experimental design. Figure 4A shows the time-course expression analysis of these four RBOH genes by RNA-Seq of sweet pepper fruits at different stages of ripening mentioned before including the NO treatment. In all four cases, the RBOH gene expression was downregulated from green (G) to red (R) stage. In general, the gene expression in fruits with and without NO treatment (BP2 + NO and BP2 − NO, respectively) both showed intermediate values between those observed for green and red peppers, but in all cases, the NO treatment increased the expression of the four RBOH genes. To corroborate these data, RT-qPCR analyses of the genes were done using the same fruit sample set to perform the RNA-Seq approach (Figure 4B). Thus, the expression of the four RBOH genes was also downregulated throughout ripening. Additionally, the NO effect (BP2 + NO) in the gene expression did not show significant difference regarding the BP − NO group, with the exception of RBOH C expression, which was downregulated.

FIGURE 4.

(A) Time-course expression analysis of four CaRBOH genes (RNA-Seq). (B) Validation of RNA-Seq data using real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). Samples of sweet pepper fruits at different stages of ripening correspond to immature green (G), breaking point 1 (BP1), and breaking point 2 with and without NO treatment (BP2 + NO and BP2 – NO, respectively). Each PCR was performed at least three times, with three independent samples. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

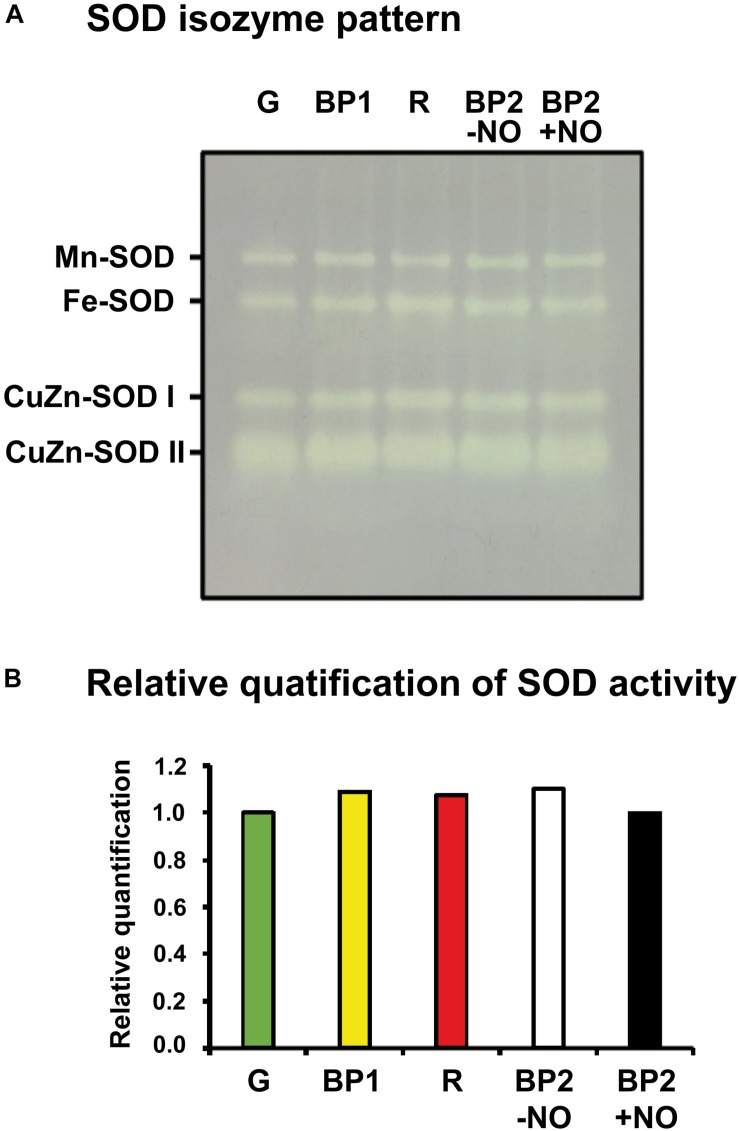

As part of the O2•– metabolism analysis, the SOD system activity and its gene expression during pepper fruit ripening were also studied. Figure 5A depicts the SOD isozyme profile in non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel of sweet pepper fruits at the different ripening stages used in this work: immature green (G), BP1, BP2 with and without NO treatment (BP2 + NO and BP2 − NO, respectively), and ripe red (R). According to the mobility in gels and the response to inhibitors, a total of four SOD isozymes were identified: one Mn-SOD, one Fe-SOD, and two CuZn-SODs. It is remarkable to point out that after the quantification of the SOD in-gel activity, none of the isozymes showed any significant change either during the ripening from green to red fruits or considering the different stages after the NO treatment (Figure 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Activity (A) and relative quantification (B) of superoxide dismutase (SOD) isozymes of sweet pepper fruits at different stages of ripening: immature green (G), breaking point 1 (BP1), and breaking point 2 with and without NO treatment (BP2 + NO and BP2 – NO, respectively). Protein (5 μg per lane) samples were separated by non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE; 8%), and the activity was detected by the nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT)-reducing method. Comparative total band intensities were quantified using ImageJ 1.45 software (see Supplementary Figure S1 for details). The gel pictures are representative of those obtained from at least three biological replicas repeated three times.

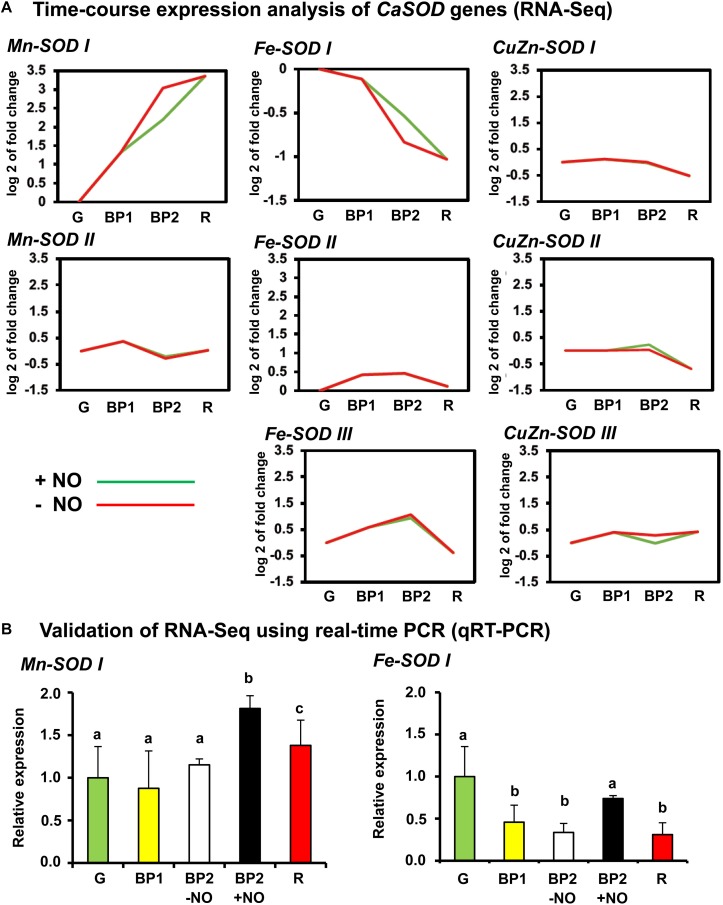

The search of SOD genes in the sweet pepper transcript database previously obtained by RNA-Seq (González-Gordo et al., 2019) allowed finding a total of eight SOD genes including two Mn-SODs, three Fe-SODs, and three CuZn-SODs. Figure 6A shows the time-course expression analysis of these eight SOD genes (RNA-Seq) of sweet pepper fruits at the different ripening stages reported above. Among these eight SOD genes, only two, Mn-SOD I and Fe-SOD I, were modulated during ripening and under the NO treatments. Whereas the Mn-SOD I expression increased during ripening, the Fe-SOD I showed an opposite behavior. Additionally, under NO treatment, the expression of these two genes was also different because Mn-SOD I was downregulated after NO treatment whereas Fe-SOD I expression increased. The data of the two genes obtained by RNA-Seq were corroborated by RT-qPCR (Figure 6B).

FIGURE 6.

(A) Time-course expression analysis of CaSOD genes (RNA-Seq). (B) Validation of RNA-Seq for Mn-SOD I and Fe-SOD I genes using real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). Each PCR was performed at least three times, with three independent samples. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

In a previous study, we showed that in sweet pepper, the O2•– generation by a NOX system was inhibited in the presence of NO donors, ONOO–, and GSH, suggesting that the responsible enzymes could be regulated by S-nitrosation, Tyr-nitration, or glutathionylation, respectively (Chu-Puga et al., 2019). However, to our knowledge, there is no such similar analysis of SOD isozymes from pepper fruits. Consequently, we performed a series of biochemical in vitro assays of the SOD activity in the presence of different chemicals including 4 mM of SIN-1 as ONOO– donor, 4 mM of GSNO and 4 mM of DEA NONOate as NO donor, 4 mM of GSH and 10 mM of DTT as reductants, and 10 mM of H2O2 as oxidant. Figure 7A shows that, except for the slight changes in the electrophoretic mobility of CuZn-SOD II, none of the SOD isozymes present in the red fruits were affected for any of the treatments. To discard potential masking effect, considering that both CuZn-SOD and Fe-SOD activities are well known to be inhibited by H2O2, it was decided to repeat the experiments, but in this case, the gel was incubated in the presence of 5 mM of H2O2 once the samples were incubated with the chemicals and the electrophoresis was completed. As observed in Figure 7B, and as expected, both CuZn-SODs and Fe-SOD were indeed inhibited whereas the Mn-SOD was unaffected in all cases. With the goal to get deeper knowledge about SOD isozyme activities and their potential regulation by RNS and distinct redox conditions, a similar analysis was done, but in this case, the gel was incubated with 5 mM of GSH (Figure 7C). In this situation, it was observed that none of the SOD isozymes underwent significant changes in its activity. However, we detected a new CuZn-SOD band close to and faster than the CuZn-SOD I in the samples treated with DEA NONOate and H2O2.

Discussion

Reactive oxygen species generation is part of the cellular metabolism, and depending on the levels of production and the ROS type, they could have either toxic effects or signal properties. There are evidences that ROS metabolism is involved in a diverse range of plant processes, and the available data indicate that fruit development and ripening have an active ROS metabolism in different species such as grapevine berry (Pilati et al., 2014), mango (Rosalie et al., 2015), peach (Huan et al., 2016), tomato (Kumar et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2017), grape berry (Xi et al., 2017), or guava (Mondal et al., 2009; Batista-Silva et al., 2018). In previous reports on sweet pepper ripening, we focused on the H2O2 metabolism, and it was found that catalase activity and their gene expression were diminished during ripening. Moreover, catalase was downregulated by NO-mediated posttranslational modifications including Tyr-nitration and S-nitrosation (Chaki et al., 2015; Rodríguez-Ruiz et al., 2019). To get deeper knowledge on the ROS metabolism during sweet pepper ripening, the present study has been focused on another main ROS, specifically in O2•–, to analyze some of the biochemical players involved in their generation and decomposition. With the goal to get a deeper understanding of the ROS metabolism during sweet pepper fruit ripening, especially on the metabolism of O2•– and its potential modulation under a NO-enrichment environment, we have based on a previous study where we reported the first transcriptome of sweet pepper at different ripening stages, being also compared with the transcriptome under a NO-enrichment environment (González-Gordo et al., 2019). In such study, it was observed that during fruit ripening the ROS metabolism was altered with an increase of lipid oxidation and that NO reduced this parameter with a concomitant increase in the content of GSH and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity.

O2•– Generation by a NADPH-Dependent Oxidase System Increases During Ripening but Is Negatively Modulated by NO

It should be mentioned that to our knowledge there are only few reports focused on the function of a specific RBOH activity during fruit ripening. In an early study, we found up to seven NADPH-oxidase isozymes that were differently regulated during the ripening of sweet pepper fruits (Chu-Puga et al., 2019). It should be remarked that the identification of the seven isozymes in non-denaturing gel activity assays involved the optimization of the amount of loaded protein samples for each stage being determined in green fruit by almost two-fold the amount found in red fruits. Thus, these seven NADPH-oxidase isozymes with different electrophoretic mobility and abundance were detected considering both green and red fruits. The present data corroborate those previous data, but the analysis of the intermediate ripening stages in the presence of NO (BP2 + NO) showed a fine regulation of this system because isozymes I and III displayed lower activities when they were compared with the BP2 without NO treatment (BP2 − NO); however, one cannot discard the existence of additional isozymes whose activity may be too low for their detection in our experimental conditions. To our knowledge, the only identified NOX that has been reported to be negatively regulated by NO corresponds to the Arabidopsis RBOH isozyme D activity (AtRBOHD) that was inhibited by S-nitrosation at Cys825, thus disturbing the mechanism of the immune response (Yun et al., 2011). Very recently, it has been reported that this AtRBOHD is also susceptible to undergo persulfidation, a posttranslational modification mediated by hydrogen sulfide (H2S) (Corpas et al., 2019), at Cys825 and Cys890, provoking an increase in the O2•– production, which was relevant in the ABA signaling to induce stomatal closure (Shen et al., 2020). In pepper fruit, we have previously described that the content of endogenous H2S increases at ripening (Muñoz-Vargas et al., 2018) and that it could be hypothesized that this H2S might be involved in the observed increase of NOX activity. However, future analyses should be carried out to corroborate this and to identify what isozyme(s) could be the target of persulfidation in our plant model.

On the other hand, these data indicate that this increase in NOX activity might be necessary in the physiological ripening process, and this is concomitant with the enhanced NADPH-generating systems described during sweet pepper ripening, specifically NADP-malic enzyme and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase activities (Muñoz-Vargas et al., 2020). However, the O2•– generation could have other beneficial effects in pepper fruit as a mechanism to prevent potential pathogen infections (Tian et al., 2013). In this sense, the latest results in apricot fruit treated exogenously with polyamines showed that the activities and gene expression levels of NOX systems were triggered, allowing the resistance to the fungus Alternaria alternata (Li et al., 2019). Recently, it has been described by in silico analyses the identification of the RBOH family genes in Chinese white pear (Pyrus bretschneideri), which contains 10 RBOHs. Among these genes, it was found that PbRBOHA and PbRBOHD were specially accumulated in pear stone cells, suggesting the involvement of ROS metabolism in the lignification of these cells (Cheng et al., 2019).

Sweet Pepper Fruit Transcriptome Contains Seven Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homolog Isozymes

Based on the comparative analysis between the Arabidopsis RBOH genes with the sweet pepper fruit transcriptome (González-Gordo et al., 2019) and their corresponding protein sequences, the seven pepper RBOH proteins were designated with the letters A, B, C, D, E, H, and J. All these RBOH proteins showed the six characteristic conserved motifs of plant RBOHs, which correspond to EF-Hand I and II, calcium and FAD binding sites, NADPH-ribose, and NADPH-adenine (Torres and Dangl, 2005; Kaur et al., 2018). However, the correspondence between the seven NOX isozymes identified with the seven RBOH genes reported here need to be confirmed by future experiments where each pepper RBOH protein encoded by its respective gene needs to be purified, and their mobility needs be evaluated under non-denaturing gel electrophoresis.

There Is No Correlation Between NADPH Oxidase and Superoxide Dismutase Isoenzymatic Activities and the Corresponding Genes

In our experimental model of sweet pepper, it should be pointed out that the analyses of activity and gene expression of both NOX and SOD isozymes have different behaviors. Thus, it was found that whereas O2•– generation by NOX isoenzymes increased during ripening, the identified RBOH genes were downregulated. Comparative observation could be made with the activity of SOD isozymes, which did not show any significant variations, whereas the gene expression of Mn-SOD increased, Fe-SOD decreased, and CuZn-SOD did not change. This apparent contradiction between enzyme activity and gene expression is not unusual, and there are numerous examples where the inexistent correlation between gene expression and their corresponding protein activity has been described. Recently, the analysis of protein and transcript abundance during tomato fruit development and ripening showed a poor correlation owing to, among other factors, the rate of protein translation and degradation; in fact, the levels of transcripts were more reduced than the protein levels (Belouah et al., 2019). Among other factors that could support these discrepancies, the protein posttranslational modifications including those mediated by ROS or RNS could be considered.

The Superoxide Dismutase Isoenzymatic Pattern Was Unaffected Either During Ripening or by a NO-Enriched Environment

In a previous study, we showed by in vitro analyses that the O2•– generation by the NADPH-oxidase system was inhibited in the presence of NO donors, ONOO–, and GSH, suggesting that the responsible enzymes can undergo S-nitrosation, Tyr-nitration, and glutathionylation, respectively (Chu-Puga et al., 2019). Although we did not observe any apparent change in the SOD isoenzymatic activity during ripening or in the NO-enriched atmosphere, we decided to prepare in vitro analyses to study the pepper SOD isoenzymatic activity because in the in vitro analysis of the seven Arabidopsis SOD isozymes, it was reported that, using GSNO as NO donor, none of the Arabidopsis SODs were affected. Conversely, peroxynitrite (a nitrating agent) triggered the inhibition of the mitochondrial Mn-SOD, peroxisomal CuZn-SOD (CSD3), and chloroplastic iron SOD3 (FSD3), whereas the other SODs were unaffected (Holzmeister et al., 2015). In our experimental conditions of sweet pepper, neither GSNO nor peroxynitrite seems to affect any of the SOD isozymes. Nevertheless, it was found that the pretreatment of pepper sample with NO and H2O2 previous to the gel analysis of the SOD isozymes allowed to identify a new CuZn-SOD with mobility higher than that of the CuZn-SOD I but slower than that of CuZn-SOD II. A reasonable explanation of the appearance of a new isoenzyme could be due to the presence of two different oxidation states of the CuZn-SOD I corresponding to a mixed Cu(I)/Cu(II) redox pair after these mentioned treatments, such as it has been described in bovine and human CuZn-SOD after isoelectrofocusing analyses (Chevreux et al., 2009). A similar behavior of the potential oxidation of a CuZn-SOD that affected the electrophoretic mobility of the enzyme was also reported for the cytosolic CuZn-SOD from watermelon cotyledons (Palma et al., 1997).

Conclusion

Reactive oxygen species metabolism is of great importance for fruit ripening because it is involved in the process of development and quality (Decros et al., 2019). The present study has focused on the O2•– metabolism in the non-climacteric sweet pepper ripening, and the data support that O2•–-generating NOX production increases during ripening being regulated by NO. On the other hand, the SOD activity of the different isoenzymes was unaffected during ripening, and it should be pointed out that none of the SOD isozymes were significantly affected by any of the assayed in vitro nitro-oxidative conditions. This suggests that the basal SOD activity is sufficient to keep the homeostasis of the necessary physiological O2•– production during sweet pepper ripening. This prevalence of O2•– production could have additional benefits because they could be a barrier to prevent potential pathogen infections. Moreover, these new data of the prevalence of O2•–-generating NOX during sweet pepper fruit ripening should be also integrated with the NADPH-generating system constituted by a group of NADP-dehydrogenases, which are regulated by signal molecules such as NO and H2S (Muñoz-Vargas et al., 2018, 2020). Additionally, future analyses should be developed to understand the integration of the redox homeostasis with the phytohormones including ABA, indole-3-acetic acid, gibberellins, cytokinins, or jasmonic acid involved in the ripening of sweet pepper considering that it is a non-climacteric fruit (Symons et al., 2012; Fuentes et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2019). This will allow to extend our knowledge of the complex network of involved signal molecules in this physiological process.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

FC and JP conceived and designed the experiments. SG-G and MR-R performed the experiments. SG-G, JP, and FC analyzed the data. All authors contributed to drafting the work, revised the final manuscript, and approved submission.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. The research work of FC and JP is supported by a European Regional Development Fund-cofinanced grant from the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (AGL2015-65104-P and PID2019-103924GB-I00), the Plan Andaluz de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación (PAIDI 2020) (P18-FR-1359), and Junta de Andalucía (group BIO192), Spain.

Acknowledgements

SG-G acknowledges a “Formación de Personal Investigador” contract (BES-2016-078368) from the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Spain. The provision of pepper fruits by Zeraim Iberica/Syngenta Seeds Ltd. (El Ejido, Almería, Spain) is acknowledged, especially Víctor J. Domínguez, Lidia Martín, and Manuel Solís. The valuable technical assistance of Mrs. María J. Campos, Mr. Carmelo Ruiz-Torres, and Dr. Pancracio is deeply acknowledged.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.00485/full#supplementary-material

References

- Airaki M., Leterrier M., Mateos R. M., Valderrama R., Chaki M., Barroso J. B., et al. (2012). Metabolism of reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) plants under low temperature stress. Plant Cell Environ. 35 281–295. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almansa M. S., del Río L. A., Alcaraz C. F., Sevilla F. (1989). Isoenzyme pattern of superoxide dismutase in different varieties of Citrus plants. Physiol. Plant 76 563–568. [Google Scholar]

- Asada K., Urano M., Takahashi M. (1973). Subcellular location of superoxide dismutase in spinach leaves and preparation and properties of crystalline spinach superoxide dismutase. Eur. J. Biochem. 36 257–266. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb02908.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista-Silva W., Cosme Silva G. M., Santana D. B., Salvador A. R., Medeiros D. B., Belghith I., et al. (2018). Chitosan delays ripening and ROS production in guava (Psidium guajava L.) fruit. Food Chem. 242 232–238. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.09.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp C., Fridovich I. (1971). Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 44 276–287. 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90370-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belouah I., Nazaret C., Pétriacq P., Prigent S., Bénard C., Mengin V., et al. (2019). Modeling protein destiny in developing fruit. Plant Physiol. 180 1709–1724. 10.1104/pp.19.00086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bin W. S., Wei L. K., Ping D. W., Li Z., Wei G., Bing L. J., et al. (2012). Evaluation of appropriate reference genes for gene expression studies in pepper by quantitative real-time PCR. Mol. Breed. 30 1393–1400. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges S. M., Salin M. L. (1981). Distribution of iron-containing superoxide dismutase in vascular plants. Plant Physiol. 68 275–278. 10.1104/pp.68.2.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camejo D., Jiménez A., Palma J. M., Sevilla F. (2015). Proteomic identification of mitochondrial carbonylated proteins in two maturation stages of pepper fruits. Proteomics 15 2634–2642. 10.1002/pmic.201400370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaki M., Álvarez de Morales P., Ruiz C., Begara-Morales J. C., Barroso J. B., Corpas F. J., et al. (2015). Ripening of pepper (Capsicum annuum) fruit is characterized by an enhancement of protein tyrosine nitration. Ann. Bot. 116 637–647. 10.1093/aob/mcv016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C., Xu X., Gao M., Li J., Guo C., Song J., et al. (2013). Genome-wide analysis of respiratory burst oxidase homologs in grape (Vitis vinifera L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 24169–24186. 10.3390/ijms141224169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Li G., Manzoor M. A., Wang H., Abdullah M., Su X., et al. (2019). In silico genome-wide analysis of respiratory burst oxidase homolog (RBOH) family genes in five fruit-producing trees, and potential functional analysis on lignification of stone cells in chinese white pear. Cells 8:E520. 10.3390/cells8060520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevreux S., Roudeau S., Fraysse A., Carmona A., Devès G., Solari P. L., et al. (2009). Multimodal analysis of metals in copper-zinc superoxide dismutase isoforms separated on electrophoresis gels. Biochimie 91 1324–1327. 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaiese P., Corrado G., Minutolo M., Barone A., Errico A. (2019). Transcriptional regulation of ascorbic acid during fruit ripening in pepper (Capsicum annuum) varieties with low and high antioxidants content. Plants (Basel) 8:206. 10.3390/plants8070206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu-Puga Á, González-Gordo S., Rodríguez-Ruiz M., Palma J. M., Corpas F. J. (2019). NADPH oxidase (Rboh) activity is up regulated during sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) fruit ripening. Antioxidants (Basel) 8:E9. 10.3390/antiox8010009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpas F. J., Fernández-Ocaña A., Carreras A., Valderrama R., Luque F., Esteban F. J. (2006). The expression of different superoxide dismutase forms is cell-type dependent in olive (Olea europaea L.) leaves. Plant Cell Physiol. 47 984–994. 10.1093/pcp/pcj071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpas F. J., Freschi L., Rodríguez-Ruiz M., Mioto P. T., González-Gordo S., Palma J. M. (2018). Nitro-oxidative metabolism during fruit ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 69 3449–3463. 10.1093/jxb/erx453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpas F. J., González-Gordo S., Cañas A., Palma J. M. (2019). Nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide in plants: which comes first? J. Exp. Bot. 70 4391–4404. 10.1093/jxb/erz031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpas F. J., Palma J. M. (2018). Nitric oxide on/off in fruit ripening. Plant Biol. 20 805–807. 10.1111/plb.12852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpas F. J., Sandalio L. M., del Río L. A., Trelease R. N. (1998). Copper-zinc superoxide dismutase is a constituent enzyme of the matrix of peroxisomes in the cotyledons of oilseed plants. New Phytol. 138 307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpas F. J., Sandalio L. M., Palma J. M., Leidi E. O., Hernández J. A., Sevilla F., et al. (1991). Subcellular dustribution of superoxide dismutase in leaves of ureide-producing leguminous plant. Physiol. Plant. 82 285–291. [Google Scholar]

- Decros G., Baldet P., Beauvoit B., Stevens R., Flandin A., Colombié S., et al. (2019). Get the balance right: ROS homeostasis and redox signalling in fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 10:1091. 10.3389/fpls.2019.01091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Río L. A., Corpas F. J., López−Huertas E., Palma J. M. (2018). “Plant superoxide dismutases: function under abiotic stress conditions,” in Antioxidants and Antioxidant Enzymes in Higher Plants, eds Gupta D. K., Palma J. M., Corpas F. J., (Cham: Springer International Publishing; ), 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fanciullino A. L., Bidel L. P., Urban L. (2014). Carotenoid responses to environmental stimuli: integrating redox and carbon controls into a fruit model. Plant Cell Environ. 37 273–289. 10.1111/pce.12153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-García C., Zayas A. E., Montiel J., Nava N., Sánchez F., Quinto C. (2019). Transcriptome analysis of the differential effect of the NADPH oxidase gene RbohB in Phaseolus vulgaris roots following Rhizobium tropici and Rhizophagus irregularis inoculation. BMC Genomics. 20:800. 10.1186/s12864-019-6162-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes L., Carlos R., Figuero C. R., Valdenegro M. (2019). Recent advances in hormonal regulation and cross-talk during non-climacteric fruit development and ripening. Horticulturae 5:45. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni J. (2001). Molecular biology of fruit maturation and ripening. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 52 725–749. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-García M. R., Ochoa-Alejo N. (2013). Biochemistry and molecular biology of carotenoid biosynthesis in chili peppers (Capsicum spp.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 19025–19053. 10.3390/ijms140919025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Gayte I., Moreno R. B., Zonjic P. S., Claros M. G. (2017). DEgenes Hunter – a flexible R pipeline for automated RNA-seq studies in organisms without reference genome. Genomics Comput. Biol. 3:31. [Google Scholar]

- González-Gordo S., Bautista R., Claros M. G., Cañas A., Palma J. M., Corpas F. J. (2019). Nitric oxide-dependent regulation of sweet pepper fruit ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 70 4557–4570. 10.1093/jxb/erz136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzmeister C., Gaupels F., Geerlof A., Sarioglu H., Sattler M., Durner J., et al. (2015). Differential inhibition of Arabidopsis superoxide dismutases by peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration. J. Exp. Bot. 66 989–999. 10.1093/jxb/eru458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houmani H., Rodríguez-Ruiz M., Palma J. M., Abdelly C., Corpas F. J. (2016). Modulation of superoxide dismutase (SOD) isozymes by organ development and high long-term salinity in the halophyte Cakile maritima. Protoplasma 253 885–894. 10.1007/s00709-015-0850-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huan C., Jiang L., An X., Yu M., Xu Y., Ma R., et al. (2016). Potential role of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant genes in the regulation of peach fruit development and ripening. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 104 294–303. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez A., Romojaro F., Gómez J. M., Llanos M. R., Sevilla F. (2003). Antioxidant systems and their relationship with the response of pepper fruits to storage at 20 degrees C. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51 6293–6299. 10.1021/jf030052i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Quesada M. J., Traverso J. Á, Alché J. D. (2016). NADPH oxidase-dependent superoxide production in plant reproductive tissues. Front. Plant Sci. 7:359. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Quesada M. J., Traverso J. A., Potocký M., Žárský V., Alché J. D. (2019). Generation of superoxide by OeRbohH, a NADPH oxidase activity during olive (Olea europaea L.) pollen development and germination. Front. Plant Sci. 10:1149. 10.3389/fpls.2019.01149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlova R., Chapman N., David K., Angenent G. C., Seymour G. B., de Maagd R. A. (2014). Transcriptional control of fleshy fruit development and ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 65 4527–4541. 10.1093/jxb/eru316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G., Pati P. K. (2018). In silico insights on diverse interacting partners and phosphorylation sites of respiratory burst oxidase homolog (Rbohs) gene families from Arabidopsis and rice. BMC Plant Biol. 18:161. 10.1186/s12870-018-1378-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G., Guruprasad K., Temple B. R. S., Shirvanyants D. G., Dokholyan N. V., Pati P. K. (2018). Structural complexity and functional diversity of plant NADPH oxidases. Amino Acids. 50 79–94. 10.1007/s00726-017-2491-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya H., Takeda S., Kobayashi M. J., Kimura S., Iizuka A., Imai A., et al. (2019). Comparative analysis of the reactive oxygen species-producing enzymatic activity of Arabidopsis NADPH oxidases. Plant J. 98 291–300. 10.1111/tpj.14212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V., Irfan M., Ghosh S., Chakraborty N., Chakraborty S., Datta A. (2016). Fruit ripening mutants reveal cell metabolism and redox state during ripening. Protoplasma 253 581–594. 10.1007/s00709-015-0836-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léchaudel M., Darnaudery M., Joët T., Fournier P., Joas J. (2018). Genotypic and environmental effects on the level of ascorbic acid, phenolic compounds and related gene expression during pineapple fruit development and ripening. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 130 127–138. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leterrier M., Airaki M., Palma J. M., Chaki M., Barroso J. B., Corpas F. J. (2012). Arsenic triggers the nitric oxide (NO) and S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) metabolism in Arabidopsis. Environ. Pollut. 166 136–143. 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Ma Y., Zhang T., Bi Y., Wang Y., Prusky D. (2019). Exogenous polyamines enhance resistance to Alternaria alternata by modulating redox homeostasis in apricot fruit. Food Chem. 301:125303. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Lv J., Liu Z., Wang J., Yang B., Chen W., et al. (2020). Integrative analysis of metabolome and transcriptome reveals the mechanism of color formation in pepper fruit (Capsicum annuum L.). Food Chem. 306:125629. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhang H., Tian L., Huang L., Liu S., Li D., et al. (2015). Tomato SlRbohB, a member of the NADPH oxidase family, is required for disease resistance against Botrytis cinerea and tolerance to drought stress. Front. Plant Sci. 6:463. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino D., Dunand C., Puppo A., Pauly N. (2012). A burst of plant NADPH oxidases. Trends Plant Sci. 17 9–15. 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martí M. C., Camejo D., Olmos E., Sandalio L. M., Fernández-García N., Jiménez A., et al. (2009). Characterisation and changes in the antioxidant system of chloroplasts and chromoplasts isolated from green and mature pepper fruits. Plant Biol. (Stuttg) 11 613–624. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00149.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martí M. C., Camejo D., Vallejo F., Romojaro F., Bacarizo S., Palma J. M., et al. (2011). Influence of fruit ripening stage and harvest period on the antioxidant content of sweet pepper cultivars. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 66 416–423. 10.1007/s11130-011-0249-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateos R. M., Bonilla-Valverde D., del Río L. A., Palma J. M., Corpas F. J. (2009). NADP-dehydrogenases from pepper fruits: effect of maturation. Physiol. Plant 135 130–139. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateos R. M., Jiménez A., Román P., Romojaro F., Bacarizo S., Leterrier M., et al. (2013). Antioxidant systems from pepper (Capsicum annuum L.): involvement in the response to temperature changes in ripe fruits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 9556–9580. 10.3390/ijms14059556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal K., Malhotra S. P., Jain V., Singh R. (2009). Oxidative stress and antioxidant systems in guava (Psidium guajava L.) fruits during ripening. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 15 327–334. 10.1007/s12298-009-0037-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montiel J., Nava N., Cárdenas L., Sánchez-López R., Arthikala M. K., Santana O., et al. (2012). A Phaseolus vulgaris NADPH oxidase gene is required for root infection by Rhizobia. Plant Cell Physiol. 53 1751–1767. 10.1093/pcp/pcs120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller K., Carstens A. C., Linkies A., Torres M. A., Leubner-Metzger G. (2009). The NADPH-oxidase AtrbohB plays a role in Arabidopsis seed after-ripening. New Phytol. 184 885–897. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Vargas M. A., González-Gordo S., Cañas A., López-Jaramillo J., Palma J. M., Corpas F. J. (2018). Endogenous hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is up-regulated during sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) fruit ripening. In vitro analysis shows that NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase (ICDH) activity is inhibited by H2S and NO. Nitric Oxide 81 36–45. 10.1016/j.niox.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Vargas M. A., González-Gordo S., Palma J. M., Corpas F. J. (2020). Inhibition of NADP-malic enzyme activity by H2S and NO in sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) fruits. Physiol. Plant 168 278–288. 10.1111/ppl.13000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio S., Scossa F., Fernie A. R. (2013). Molecular regulation of fruit ripening. Front. Plant Sci. 4:198. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou L. J., Zhang Z. Q., Dai X. Z., Zou X. X. (2013). Photooxidation tolerance characters of a new purple pepper. PLoS One 8:e63593. 10.1371/journal.pone.0063593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma J. M., de Morales P. Á, del Río L. A., Corpas F. J. (2018). The proteome of fruit peroxisomes: sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) as a model. Subcell Biochem. 89 323–341. 10.1007/978-981-13-2233-4_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma J. M., Freschi L., Rodríguez-Ruiz M., González-Gordo S., Corpas F. J. (2019). Nitric oxide in the physiology and quality of fleshy fruits. J. Exp. Bot. 70, 4405–4417. 10.1093/jxb/erz350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma J. M., Pastori G. M., Bueno P., Distefano S., del Río L. A. (1997). Purification and properties of cytosolic copper, zinc superoxide disrnutase from watermelon (Citrullus vulgaris Schrad.) cotyledons. Free Radic. Res. 26 83–91. 10.3109/10715769709097787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma J. M., Sevilla F., Jiménez A., del Río L. A., Corpas F. J., Álvarez de Morales P., et al. (2015). Physiology of pepper fruit and the metabolism of antioxidants: chloroplasts, mitochondria and peroxisomes. Ann. Bot. 116 627–636. 10.1093/aob/mcv121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma J. M., Ruiz C., Corpas F. J. (2018). A simple and useful method to apply exogenous no gas to plant systems: bell pepper fruits as a model. Methods Mol. Biol. 1747 3–11. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7695-9_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual I., Azcona I., Aguirreolea J., Morales F., Corpas F. J., Palma J. M., et al. (2010). Growth, yield, and fruit quality of pepper plants amended with two sanitized sewage sludges. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58 6951–6959. 10.1021/jf100282f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinilla M., Iglesias-Moya J., Campos M. J., Corpas F. J., Palma J. M. (2019). Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) fruits: characterization of the main enzymatic antioxidants (peroxisomal catalase and SOD isozymes) and the NADPH-regenerating system. Agronomy 9:338. [Google Scholar]

- Pilati S., Brazzale D., Guella G., Milli A., Ruberti C., Biasioli F., et al. (2014). The onset of grapevine berry ripening is characterized by ROS accumulation and lipoxygenase-mediated membrane peroxidation in the skin. BMC Plant Biol. 14:87. 10.1186/1471-2229-14-87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y., Yan M., Zhang Q. (2017). Functional regulation of plant NADPH oxidase and its role in signaling. Plant Signal. Behav. 12:e1356970. 10.1080/15592324.2017.1356970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribes-Moya A. M., Adalid A. M., Raigón M. D., Hellín P., Fita A., Rodríguez-Burruezo A. (2020). Variation in flavonoids in a collection of peppers (Capsicum sp.) under organic and conventional cultivation: effect of the genotype, ripening stage, and growing system. J. Sci. Food Agric. 100 2208–2223. 10.1002/jsfa.10245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Ruiz M., Mateos R. M., Codesido V., Corpas F. J., Palma J. M. (2017). Characterization of the galactono-1,4-lactone dehydrogenase from pepper fruits and its modulation in the ascorbate biosynthesis. Role of nitric oxide. Redox Biol. 12 171–181. 10.1016/j.redox.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Ruiz M., Mioto P., Palma J. M., Corpas F. J. (2017). S-nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR) activity is down-regulated during pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) fruit ripening. Nitric Oxide 68 51–55. 10.1016/j.niox.2016.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Ruiz M., González-Gordo S., Cañas A., Campos M. J., Paradela A., Corpas F. J., et al. (2019). Sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) fruits contain an atypical peroxisomal catalase that is modulated by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Antioxidants (Basel) 8:E374. 10.3390/antiox8090374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosalie R., Joas J., Deytieux-Belleau C., Vulcain E., Payet B., Dufossé L., et al. (2015). Antioxidant and enzymatic responses to oxidative stress induced by pre-harvest water supply reduction and ripening on mango (Mangifera indica L. cv. ‘Cogshall’) in relation to carotenoid content. J. Plant Physiol. 184 68–78. 10.1016/j.jplph.2015.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagi M., Fluhr R. (2006). Production of reactive oxygen species by plant NADPH oxidases. Plant Physiol. 141 336–340. 10.1104/pp.106.078089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen T. D., Livak K. J. (2008). Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C T method. Nat. Protoc. 3 1101–1108. 10.1038/nprot.2008.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoane P., Espigares M., Carmona R., Polonio Á, Quintana J., Cretazzo E., et al. (2018). TransFlow: a modular framework for assembling and assessing accurate de novo transcriptomes in non-model organisms. BMC Bioinform. 19:416. 10.1186/s12859-018-2384-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Zhang J., Zhou M., Zhou H., Cui B., Gotor C., et al. (2020). Persulfidation-based modification of cysteine desulfhydrase and the NADPH oxidase RBOHD controls guard cell abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell 32 1000–1017. 10.1105/tpc.19.00826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L. R., Zhao Z. J., Hao F. S. (2019). NADPH oxidases, essential players of hormone signalings in plant development and response to stresses. Plant Signal. Behav. 14:1657343. 10.1080/15592324.2019.1657343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N., Miller G., Morales J., Shulaev V., Torres M. A., Mittler R. (2011). Respiratory burst oxidases: the engines of ROS signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14 691–699. 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symons G. M., Chua Y. J., Ross J. J., Quittenden L. J., Davies N. W., Reid J. B. (2012). Hormonal changes during non-climacteric ripening in strawberry. J. Exp. Bot. 63 4741–4750. 10.1093/jxb/ers147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanou G., Minas I. S., Karagiannis E., Tsikou D., Audebert S., Papadopoulou K. K., et al. (2015). The impact of sodium nitroprusside and ozone in kiwifruit ripening physiology: a combined gene and protein expression profiling approach. Ann. Bot. 116 649–662. 10.1093/aob/mcv107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian S., Qin G., Li B. (2013). Reactive oxygen species involved in regulating fruit senescence and fungal pathogenicity. Plant Mol. Biol. 82 593–602. 10.1007/s11103-013-0035-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M. A., Dangl J. L. (2005). Functions of the respiratory burst oxidase in biotic interactions, abiotic stress and development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 8 397–403. 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H., Yuan W., Ruan M., Ye Q., Wang R., Li Z., et al. (2011). Identification of reference genes for reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR normalization in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). BBRC 416 24–30. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. F., Li W. Q., Li W. Y., Wu G. L., Zhou C. Y., Chen K. M. (2013). Characterization of rice NADPH oxidase genes and their expression under various environmental conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 9440–9458. 10.3390/ijms14059440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Chen D., Zhang X., Liu D., Cheng Y., Shen F. (2018). Role of plant respiratory burst oxidase homologs in stress responses. Free Radic. Res. 52 826–839. 10.1080/10715762.2018.1473572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi F. F., Guo L. L., Yu Y. H., Wang Y., Li Q., Zhao H. L., et al. (2017). Comparison of reactive oxygen species metabolism during grape berry development between ‘Kyoho’ and its early ripening bud mutant ‘Fengzao’. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 118 634–642. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun B. W., Feechan A., Yin M., Saidi N. B., Le Bihan T., Yu M., et al. (2011). S-nitrosylation of NADPH oxidase regulates cell death in plant immunity. Nature 478 264–268. 10.1038/nature10427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Li Y., He Y., Hu W., Zhang Y., Wang X., et al. (2018). Identification of NADPH oxidase family members associated with cold stress in strawberry. FEBS Open Bio 8 593–605. 10.1002/2211-5463.12393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Chen Y., Shi G., Zhang X. (2017). Selenium delays tomato fruit ripening by inhibiting ethylene biosynthesis and enhancing the antioxidant defense system. Food Chem. 219 179–184. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.09.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.