Abstract

Background

Total ankle replacement (TAR) is a high-risk procedure with significant revision rates, post-op complications and implant failures. Long term follow-up data is less available for TAR compared to other joint replacement surgeries. To identify optimal follow-up parameters for patients with TAR, we conducted a study on the clinical outcomes and patient-reported outcome measurements (PROMs) in patients who had TAR performed in a non-designer's centre belonging to one of the hospitals of East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust (ELHT).

Methods

60 TAR procedures were identified. Clinical outcomes being studied include post-op ankle range of movement (ROM), American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society (AOFAS) Ankle-Hindfoot scores, reoperation/revision rates, radiological parameters and general surgical outcomes. A Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was also conducted. PROMs data included the EQ-5D index and the Manchester-Oxford Foot Questionnaire (MOX-FQ).

Results

Ankle range of movement and AOFAS scores improved from pre-op to post-op with statistical significance. The reoperation rate and revision rate were 3.3% and 8.3% respectively. 5-year survival of implant was 97.3% and 10-year survival was 84.2%. Overall PROMs data showed improvement from pre-op to post-op.

Conclusion

The clinical outcomes of TARs were comparable with conventional literature. Improvements in clinical, radiological and patient-reported outcomes were observed from pre-op to post-op. Further follow-up studies are required to assess the long-term survival of implants.

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) of ankles refers to the clinical manifestation of cartilage degeneration, loss of menisci, growth of osteophytes and loss of joint space at the ankle joint. Patients with ankle osteoarthritis often suffer from ankle stiffness, restricted mobility and chronic pain. Total ankle replacement (TAR) is one of main surgical treatments for patients with end-stage osteoarthritis, which involves replacement of ankle joint articulations with prosthetic implants. Total ankle replacement is associated with high rates of implant failure, leading to subsequent revision surgeries. Routine monitor of surgical outcomes is required to assess if the failure rates at a non-designer's centre are comparable with those reported in current literature. Recent studies agreed that the 5-year survival of ankle replacements lies between 85 and 90%, while the 10-year survival rate lies between 70 and 80%.1 At ELHT, TARs were being performed for over 15 years. A timely assessment of surgical outcomes would be appropriate to keep track of implant survival data and identify key areas to reduce post-op complications.

In addition, a recent change in definition of ‘revision’ procedures was proposed by the UK National Joint Registry (NJR). Prior to the change, reports from current literature were inconclusive on whether the exchange of polyethylene insert of mobile bearing implants should be considered as ‘revision’ or ‘reoperation’. Starting from 2018, secondary procedures that involves changing of implant components, including polyethylene inserts, should be identified as revision surgeries. With this change, the revision rate of TARs would need to be updated to adhere to the current definitions.

1.1. Background

Ankle arthrodesis was the mainstay of treatment for ankle osteoarthritis in earlier years, but it was associated with higher rates of complications such as wound issues and joint non-union.2 With recent advancements of technology in joint replacement surgeries, the preferred treatment is gradually shifting towards total ankle replacement. In UK, the National Joint Registry (NJR) reported a total of 734 ankle replacements were being performed in 2018, which showed an increasing trend compared to the recorded number of 417 ankle replacements back in 2010 when the NJR first initiated the database for ankle replacement surgery.

There are no existing national clinical guidelines on TARs with regards to assessment of replacement outcomes. As a result, we conducted an evidence-based search with search engine PubMed to select the most appropriate parameters for our audit.

1.2. Patient demographics

1.2.1. Indication and contraindications

Syed and Ugwuoke1 performed a systematic review of worldwide joint registries and identified osteoarthritis as the commonest indication for ankle replacements (92.3%), followed by rheumatoid arthritis (5.5%). Zaidi et al.3 found rheumatoid arthritis is a risk factor for reoperations. Barg et al.4 suggested absolute contraindications for TAR include Charcot foot, active infection and peripheral neuropathies. They also suggested relative contraindications such as smoking, osteoporosis and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) were associated with poor clinical outcomes.

1.2.2. Intra-op complications

Complications are not uncommon during ankle replacement surgeries. These include fractures, implant positioning difficulties and injury to nerves and tendons. Fracture of malleoli was found to be the most common complication (23%), followed by peroneal nerve injuries (10%).4

1.2.3. Ankle function

The AOFAS score is comprised of 3 sections: pain, function and alignment of the hindfoot. Malviya et al.5 reported that the AOFAS score was shown to correlate with quality-adjusted life year (QALY) scores when comparing pre-op and scores starting at 6 months post-TAR. Measures of ROM is performed by combining the degrees of dorsiflexion and plantarflexion.

1.2.4. Reoperation/revision

Zaidi et al.3 found the implant failure rate to be 1.2% at 12 months post-op, which was significantly higher compared to the failure rate of 0.76% in hip replacements and other joint replacement surgeries. According to the NJR, the most common indication for revision is aseptic loosening of implant, followed by post-op residual pain.

1.2.5. Radiological parameters

The tibiotalar ratio is defined in the report by Tochigi et al.6 In their study, it was suggested that the tibiotalar ratio correlates with the severity of osteoarthritic joint degeneration by measuring the anterior or posterior subluxation of talus. An increase in post-op tibiotalar ratio predicts the relocation of talus to a satisfactory position. The inclination of tibial component to tibia serves to predict if the positioning of talus is ideal within the ankle mortise. Angles below 83° could indicate incorrect anterior subluxation of talus.7 The varus/valgus ankle of tibial component used in this study was defined in the report of Haytmanek et al.8

1.2.6. Patient reported outcome measurements

The EQ-5D measures general health in 5 different domains, including mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and anxiety. An overall score of general health is also measured. The Manchester Oxford Foot Questionnaire (MOX-FQ) is a validated questionnaire for foot conditions with 16 items assessing on pain, mobility and social functioning.9 The PROMS data consists of valuable information reported directly from patients through questionnaires. These data would allow surgeons to acquire updated information on patient quality of life, pain scores, physical functioning and psychological health, which are not measurable solely with clinical parameters.

2. Methods

The target audit population was all traceable patients who had TARs performed in ELHT. A prospective search of the ELHT patient database was performed using codes from Office of Population Censuses and Surveys (OPCS) Classification of Interventions and Procedures. The corresponding codes identified were O32.1 or (W43·1/W44·1/W45.1) +Z85.6. For patients with replacements performed before 2013, their records were identified manually with archived hardcopies of operation notes. The criteria were sent to ELHT clinical audit department for case notes retrieval. A proforma with the relevant parameters was created for data collection. Radiological outcomes were measured using the picture archiving and communication system (PACS) system. Post-op PROMS data were collected via telephone interviews with patient consent. There were no ethical concerns.

Statistical analysis included mean, standard deviations (SD), 95% confidence intervals and p values. Paired t-test was conducted to obtain p values with p < 0.05 considered as statistically significant. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed with the IBM SPSS software. The data is presented in the form of mean ± S.D.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic data

58 patients involving 60 TARs were included in this audit. Detailed demographics data were summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| Mean/Mean ± S.D/Percentage | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 58 | |

| Number of procedures | 60 | |

| Bilateral TARs | 2 | |

| Male | 38 | |

| Female | 20 | |

| Left sided TAR | 68.3% | |

| Right sided TAR | 31.7% | |

| Age | 69 ± 9.96 | 26–85 |

| BMI | 29.8 ± 4.49 | 21–43 |

| % within BMI 20–25 | 13.3% |

The oldest traceable ankle replacement was performed 16 years ago in 2003. Mean post-op follow-up time in outpatient settings was 44.1 months. Mortality rate was 21.7%. The mean follow-up duration from post-op to death was 41.2 months. Minimum duration from post-op to death was 6 months.

The most common indication for total ankle replacement was primary osteoarthritis (56%). 7% was due to rheumatoid arthritis (RA). 3% of patients had absolute contraindications at pre-op assessment, including peripheral neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease. All cases were assessed thoroughly pre-op for surgical risks. The commonest relative contraindication was T2DM (18%).

50% of patients received the Zenith (Corin) implant, while 47% of patients received the Mobility (DePuy Synthes) implant.

3.2. Intra-op complications

9 complications were recorded, and the overall complication rate was 15%. The most common complication was fracture of medial malleolus (n = 4), followed by damage of tibialis anterior tendon sheath and distal fibula fracture. These cases were managed without further complications.

3.3. General surgical outcomes

DVT rate was 1.7%. There was only 1 DVT case recorded at 61 days post-op due to popliteal vein thrombosis despite DVT prophylaxis. Surgical site infection rate was 3.3%. All cases were covered with pre and post-op antibiotics. The 30-day readmission rate was 5%, indications consist of acute coronary syndrome, suspected DVT and acute urinary retention. The mean time to ankle-related readmissions was 350 days. Indications included wound debridement and periprosthetic fracture due to stress reaction to implant.

3.4. Ankle function

The mean pre-op ROM was 26.3 ± 9.5° (range 5–45; 95% CI = 23.9–28.8). Total ROM increased for 6.8° up to 33.1 ± 9.2° (95% CI = 30.4–35.8) at 6 months post-op and 33.3 ± 10.2° (95% CI = 30.0–36.5) at the most recent follow-up. All ROM increases were statistically significant (p < 0.05) with the exception of dorsiflexion from pre-op to most recent follow-up (p = 0.10, p > 0.05). (Table 2).

Table 2.

ROM changes from pre-op to post-op.

| Range of movement (ROM) | Pre-op | Post-op |

p-value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 12 months | Most recent | 6 months | 12 months | Most recent | ||

| Dorsiflexion (Deg) | 6.51 ± 4.7 | 8.79 ± 4.9 | 10.0 ± 5.1 | 7.3 ± 4.9 | 0.006 | < 0.001 | 0.1 |

| Plantarflexion (Deg) | 19.8 ± 8.3 | 24.3 ± 6.8 | 24.3 ± 6.8 | 26 ± 8.1 | < 0.001 | 0.005 | < 0.001 |

| Total ROM (Deg) | 26.3 ± 9.5 | 33.1 ± 9.2 | 34.2 ± 9.2 | 33.3 ± 10.2 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

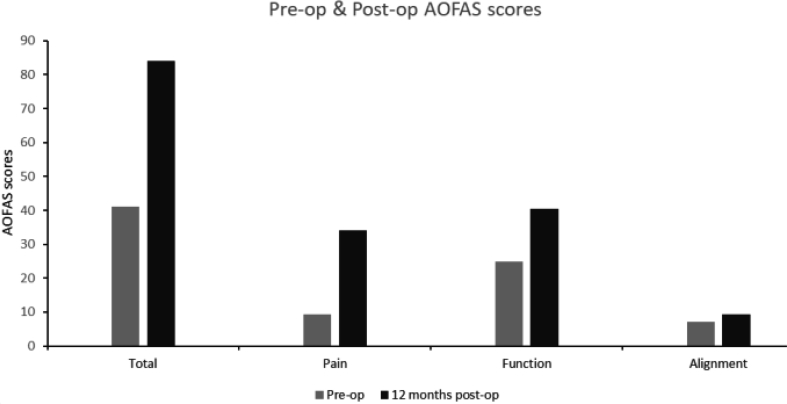

AOFAS scores increased for 42.9 points up to 84 ± 14.4 (range 48–100; 95% CI = 79.6–88.4) at 12 months post-op. Changes in AOFAS score from pre-op to post-op were all statistically significant (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1; Table 3.).

Fig. 1.

Pre-op and post-op AOFAS comparison (Total & component scores).

Table 3.

Pre-op and post-op AOFAS changes.

| AOFAS score | Pre-op | Post-op |

p-value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 months | Most recent* | 12 months | Most recent* | ||

| Total (100) | 41.1 ± 14.5 | 84.0 ± 14.4 | 80.1 ± 17.1 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Pain (40) | 9.3 | 34.1 | 31.8 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Function (50) | 24.9 | 40.4 | 39.3 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Alignment (10) | 7.1 | 9.4 | 9 | < 0.001 | 0.009 |

2 cases of reoperation were recorded. The reoperation rate was 3.3%. A valgus displacement osteotomy was performed 21 months post-op due to excessive hindfoot deformity. An excision of ankle ganglion was performed at 47 months post-op.

5 cases of revision surgeries were recorded. The revision rate was 8.3%. Mean time to revision was at 92.8 months post-op. The most common indication was damaged polyethylene insert of implant (n = 3). Other indications included septic loosening and leg amputation. 2 patients received conversion to tibiotalar calcaneal fusion.

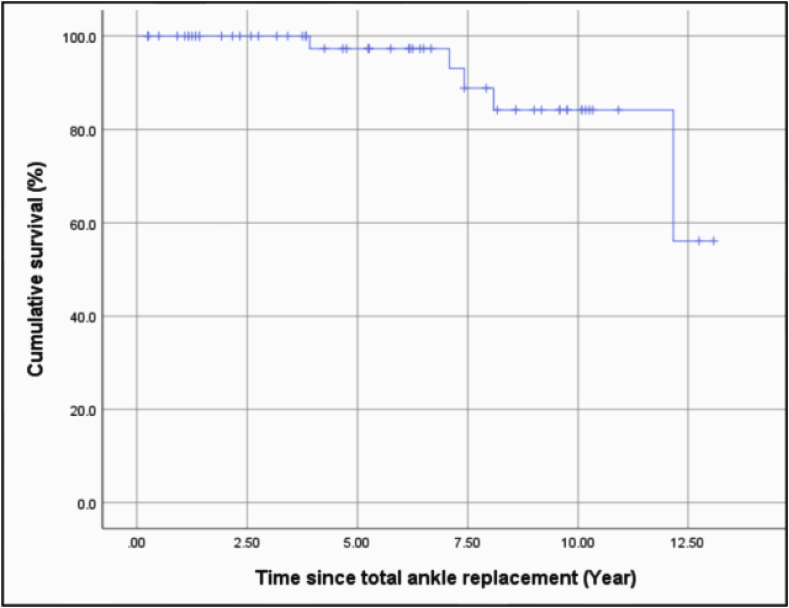

A Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was conducted to identify the survival rate of ankle implants. Failure was defined as revision of ankle replacement, while censorship was defined as withdrawal (survival without revision) or death. The 5-year survival rate was 97.3%, while the 10-year survival rate was 84.2% (Fig. 2; Table 4.)

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve.

Table 4.

Kaplan-Meier life-table survival analysis.

| Years since total ankle replacement | Number of cases at start | Number of revision surgeries | Withdrawal/Death | Implant survival rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to 1 | 60 | 0 | 6 | 100.0% |

| 1 to 2 | 54 | 0 | 8 | 100.0% |

| 2 to 3 | 46 | 0 | 4 | 100.0% |

| 3 to 4 | 42 | 1 | 5 | 97.3% |

| 4 to 5 | 36 | 0 | 3 | 97.3% |

| 5 to 6 | 33 | 0 | 4 | 97.3% |

| 6 to 7 | 29 | 0 | 6 | 97.3% |

| 7 to 8 | 23 | 2 | 2 | 88.8% |

| 8 to 9 | 19 | 1 | 4 | 84.2% |

| 9 to 10 | 14 | 0 | 5 | 84.2% |

| 10 to 11 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 84.2% |

| 11 to 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 84.2% |

| 12 to 13 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 56.1% |

| 13 to 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 56.1% |

| 14 to 15 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 56.1% |

3.5. PROMs outcomes

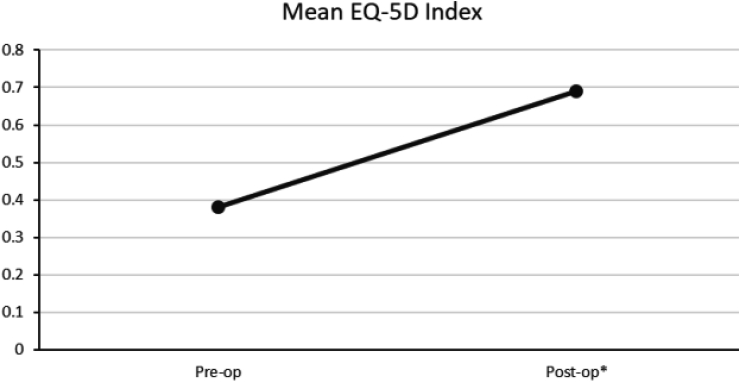

Excluding deceased patients, the response rate to interviews was 93.6%. For EQ5D, the scores were converted to an EQ5D index (−0.56 – 1) using the method reported by van Hout et al.,10 with 1 being the best outcome.11 The EQ5D index increased from 0.38 ± 0.2 (95% CI = 0.30–0.46) to 0.69 ± 0.22 (95% CI = 0.63–0.75) post-op with a significant p value (p < 0.001). However, the EQ-5D QOL visual analogue scale decreased from 67.3% ± 20.3 (95% CI = 58.6–75.9) to 64.7% ± 23.9 (95% CI = 57.6–71.8) post-op (Fig. 3; Table 5).

Fig. 3.

Pre-op and post-op changes in EQ-5D index.

Table 5.

Pre-op and post-op changes in EQ-5F index and EQ-5D quality of life visual analogue scale.

| EQ-5D | Pre-op | Post-op* | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index (−0.56 - 1) | 0.38 ± 0.2 | 0.69 ± 0.22 | < 0.001 | |

| Quality of life visual analogue scale (100) | 67.3 ± 20.3 | 64.7 ± 23.9 | 0.038 |

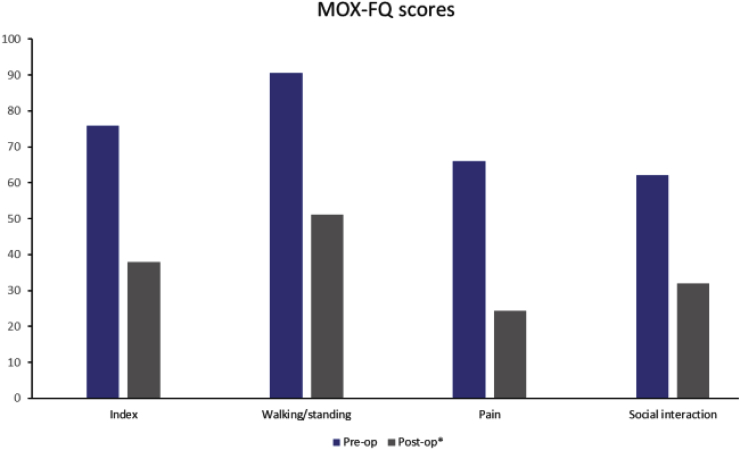

For MOX-FQ, scores were converted to a metric scale (0–100) for comparison, values closer to 0 are considered as better outcomes.9 The mean MOX-FQ index improved from 75.9 ± 10 (range 48.4–92.2; 95% CI = 71.0–80.0) to 38.0 ± 22.9 post-op (range 0–73.4; 95% CI = 31.2–44.8), which was statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4; Table 6.).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of pre-op and post-op MOX-FQ scores (Total & component scores).

Table 6.

Changes in MOX-FQ index and component scores from pre-op to post-op.

| MOX-FQ | Pre-op | Post-op∗ | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index (100) | 75.9 ± 10 | 38.0 ± 22.9 | < 0.001 | |

| Walking/Standing (100) | 90.6 ± 10.9 | 51.2 ± 28.2 | < 0.001 | |

| Pain (100) | 66.1 ± 13.5 | 24.3 ± 23.9 | < 0.001 | |

| Social interaction (100) | 62.2 ± 21.2 | 32 ± 28.4 | < 0.001 |

Radiological parameters.

The tibiotalar ratio measured at most recent follow-up increased from 32.8% ± 8.8–35.3% ± 6.7 post-op, which was statistically significant (p = 0.012, p < 0.05) (Table 7). The mean inclination angle of tibial component immediately post-op was 86.7 ± 3.6°. 58.3% of ankles were within 83–90° at most recent follow-up, with 20% of ankles below 83° of inclination. The changes of both inclination (p = 0.19) and varus/valgus angle (p = 0.45) from immediate post-op to most recent follow-up was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 8.).

Table 7.

Tibiotalar ratio changes from pre-op to immediate post-op and most recent follow-up post-op.

|

Radiological parameters |

Pre-op | Post-op |

p-value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate* | Most recent* | Immediate* | Most-recent* | |||

| Tibiotalar ratio (%) | 32.8% ± 8.8 | 33.2% ± 7.4 | 35.3% ± 6.7 | 0.35 | 0.012 | |

Table 8.

Comparison of tibial component inclination and varus/valgus angle of tibial component at immediate post-op and most recent follow-up post-op.

| Radiological parameters | Post-op |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate* | Most recent* | ||

| Inclination of tibial component (Deg) | 86.7 ± 3.6 | 86.2 ± 3.9 | 0.19 |

| Varus/valgus of tibial component (Deg) | 88.3 ± 3.9 | 88.2 ± 4.1 | 0.45 |

4. Discussion

Our study provided a detailed demographic picture of patients receiving total ankle replacements in a non-designer's centre. The mean age of patients was found to be 69. Current literature has yet to establish an association between age and risk of revision. Barg et al.4 suggested patients under age 70 was associated with 4 times increase in risk of implant failure, while Tenenbaum et al.12 suggested there was no difference in clinical outcomes in different age groups. In our study, 4 out of 5 cases of revision surgery were performed below age 70. Further studies on the association between age and odds of revision would be of value in the future. In terms of BMI, we found that only 13.3% of patients met the normal range of BMI 20–25. In the study by Barg et al.,4 they noted that although the range of BMI 20–25 would be ideal, only 10–20% would meet the criteria. This was supported by van der Plaat and Haverkamp,13 that BMI showed no correlation to risk of revision surgery and should not be considered as a contraindication.

In our study, 18% of patients had diabetes diagnosed at pre-op. van der Plaat and Haverkamp13 suggested controlled diabetes was not a risk factor of delayed wound healing or wound debridement in TAR. This was demonstrated in our study, where none of our patients who had revision surgery or wound debridement had pre-op diabetes. Primary arthritis (56%) was the most common indication for TAR in our patients, while only 7% were diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis is an established risk factor for reoperations such as bony debridement.3 This was supported by Hirao et al.,14 who suggested rheumatoid arthritis was associated with higher rates of periarticular osteopenia and excessive bone loss in rheumatoid arthritis, leading to risk of talar component subsidence and prothesis instability. In our study, 1 out of 5 revision cases had pre-op rheumatoid arthritis. Hence, further follow-up is warranted to monitor the clinical outcomes of TARs with pre-op rheumatoid arthritis.

With regards to general surgical outcomes, 1 DVT case was recorded despite pre and post-op DVT prophylaxis. The 30-day readmission rate was found to be 5%. In the study by Zaidi et al.,3 the 30-day readmission rate was 2.2% in 1627 TAR procedures, of which 32% were due to implant-related indications. In our study, none of the 30-day readmissions were implant related.

In terms of ankle function outcomes, we observed a 27% increase in total ROM from 26.3° pre-op to 33.3° post-op. The observed increase in total ROM is consistent with those in other studies. Barg et al.15 observed an increase in total ROM from 22.5° to 34.3° post-op, while Tenenbaum et al.12 reported a 19% increase in post-op ROM. In our study, both dorsiflexion and plantarflexion yielded significant increase at 12 months post-op. With regards to AOFAS score changes, the total score increased from 41.1 to 80.1 at 5 years post-op in our study. All AOFAS score components recorded an increase with statistical significance. Most literature recorded similar increases in AOFAS scores with statistical significance. A systematic review of 28 studies by Zaidi et al.16 recorded an increase in AOFAS scores from 40 to 80 post-op at 8.2 years.

Our study demonstrated a reoperation rate of 3.3%, involving valgus osteotomy and cyst aspiration. Koo et al.17 suggested the indication for cyst aspiration was more commonly seen in ankle prostheses with a dual hydroxyapatite coating. There were difficulties in comparing reoperation rates in literature, primarily due to the heterogenicity of reoperation definitions involving polyethylene inserts. In our study, procedures involving the polyethylene insert were defined as revision instead of reoperation. In the study by Zaidi et al.,3 the reoperation rate was 6.6% in 1627 NJR records, including exchange of polyethylene insert.

The revision rate in our study was 8.3% at a mean of 7.7 years post-op, which is comparable to rates in United Kingdom. The revision rate in United Kingdom was 7.7% at 5 years post-op.1 Higher rates of revision were observed in Scandinavian areas. Zaidi et al.3 suggested this might be due to higher rates of rheumatoid arthritis in Scandinavian. Interestingly, studies had yet to identify a statistically significant risk factor for revision surgeries.

The most common indication for revision was exchange of damaged polyethylene insert in our study, which differs significantly from other studies. Most studies reported aseptic loosening of implant as the most common indication, followed by persistent pain. Again, this might be due to heterogenicity in definitions of revision surgeries. The study by Palanca et al.18 reported a survival rate of polyethylene inserts to be 85.7% at 15.7 years. Given the prevalence of polyethylene insert damages in our study, further studies are required to identify possible risk factors contributing to the damage of polyethylene inserts.

The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis performed in our study showed a 5-year survival of 97.3% and a 10-year survival of 84.2%, which is similar to those reported in other studies. Zaidi et al.16 analysed 7942 TARs and reported a 10-year survival of 89%. Similar results were observed in implant-specific studies. Walter et al.19 reported a 5-year survival of 94% in 155 Zenith TARs, and Wood et al.20 reported a 5-year survival of 93.6% in 100 Mobility TARs.

Both EQ-5D & MOX-FQ in our study showed an overall improvement in patient's quality of life post-TAR. The mean EQ-5D index increased from 0.38 to 0.69 at 5.7 years post-op. The EQ-5D Quality of Life visual analogue scale decreased from pre-op to post-op, this however was mostly due to other co-existing health conditions such as hip joint replacements and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) that is likely to affect quality of life. Kamrad et al.11 studied PROMS data from 269 TARs and recorded an increase of EQ-5D index from 0.4 pre-op to 0.7 at 2 years post-op. Notably, significant changes in EQ-5D scores were detected only at the critical window of 6 months–12 months post-op but not at any other timepoints. In our study, most patients did not have records of PROMs at 12 months post-op. Given the evidence in literature, we therefore suggest routine measurement of PROMs at 12 months post-op would be of benefit in future TARs.

In terms of radiological outcomes, the tibiotalar ratio showed an increase from 32.8% pre-op to 35.3% at 3.5 years post-op. Usuelli et al.21 recorded an increase in tibiotalar ratio from 36.1% pre-op to 38% at 1-year post-op in 66 TARs. A previous study by Usuelli et al.22 also observed the posterior relocation of previously anteriorly subluxed talus in ankles with increased tibiotalar ratio. Routine surveillance of radiological parameters in future would be beneficial to monitor the in-situ status of implant.

Several limitations were identified in our study. The retrospective nature of this study may lead to bias arising from incomplete data. For example, we could only compare PROM changes in patients with complete pre-op and post-op data, leading to inevitable selection bias. Poor documentation also led to missing parameters such as incomplete ROM measurements and AOFAS scores. The inaccurate use of OPCS codes also led to incomplete identification of patients with TAR performed.

Contributor Information

T. Cheung, Email: cheungtimothy1411@gmail.com.

A. Din, Email: mrazhardin@gmail.com.

A. Zubairy, Email: aamir.zubairy@elht.nhs.uk.

References

- 1.SyedF UgwuokeA. Ankle arthroplasty. EFORT Open Rev. 2018;3(6):391–397. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.170029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LawtonCD ButlerBA., Dekker 2ndRG, PrescottA KadakiaAR. Total ankle arthroplasty versus ankle arthrodesis-a comparison of outcomes over the last decade. J Orthop Surg Res. 2017;12(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s13018-017-0576-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaidi R., Macgregor A.J., Goldberg A. Quality measures for total ankle replacement, 30-day readmission and reoperation rates within 1 year of surgery: a data linkage study using the NJR data set. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.BargA WimmerMD., WiewiorskiM WirtzDC., PagenstertGI ValderrabanoV. 2015. Total Ankle Replacement. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malviya A., Makwana N., Laing P. AOFAS SCORES. Trend and correlation with QALY score. Orthop Proc. 2005;87-B(SUPP_III):375. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87BSUPP_III.0870375c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.TochigiY SuhJ-S., AmendolaA SaltzmanCL. Ankle alignment on lateral radiographs. Part 2: reliability and validity of measures. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27(2):88–92. doi: 10.1177/107110070602700203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WoodPLR PremH., SuttonC Total ankle replacement: medium-term results in 200 Scandinavian total ankle replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(5):605–609. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B5.19677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.HaytmanekCT GrossC., EasleyME NunleyJA. Radiographic outcomes of a mobile-bearing total ankle replacement. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36(9):1038–1044. doi: 10.1177/1071100715583353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MorleyD, JenkinsonC, DollH The manchester–oxford foot questionnaire (MOXFQ) development and validation of a summary index score. Bone Jt Res. 2013;4(2):66–69. doi: 10.1302/2046-3a7a58.24.2000147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Hout B, Janssen M.F., Feng Y.S. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Heal J Int Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2012;15(5):708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.KamradI CarlssonÅ., HenricsonA MagnussonH., KarlssonMK RosengrenBE. Good outcome scores and high satisfaction rate after primary total ankle replacement. Acta Orthop. 2017;88(6):675–680. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2017.1366405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.TenenbaumS BariteauJ., ColemanS BrodskyJ. Functional and clinical outcomes of total ankle arthroplasty in elderly compared to younger patients. Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;23(2):102—107. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van derPlaatL, HaverkampD Patient selection for total ankle arthroplasty. Orthop Res Rev. 2017;9:63–73. doi: 10.2147/orr.s115411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HiraoM, HashimotoJ, TsuboiH Total ankle arthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis in Japanese patients: a retrospective study of intermediate to long-term follow-up. JB JS open access. 2017;2(4) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.OA.17.00033. e0033-e0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.BargA KnuppM., HintermannB . vol. 36. 2013. (Outcomes after Total Ankle Replacement). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaidi . 2013. The outcome of total ankle replacement; pp. 1500–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.KooK, LiddleAD, PastidesPS, RosenfeldPF. The Salto total ankle arthroplasty - clinical and radiological outcomes at five years. Foot Ankle Surg. April2018. doi:10.1016/j.fas.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.PalancaA MannRA., MannJA HaskellA. 2018. Scandinavian Total Ankle Replacement : 15-Year Follow-Up. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WalterR HarriesW., HeppleS WinsonI. The Zenith total ankle replacement: early to mid-term results in 155 cases. Orthop Proc. 2015;97-B(SUPP_14):15. doi: 10.1302/1358-992X.97BSUPP_14.BOFAS2015-015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WoodPLR KarskiMT., WatmoughP Total ankle replacement: the results of 100 mobility total ankle replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(7):958–962. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B7.23852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.UsuelliFG ManziL., BrusaferriG NeherRE., GuelfiM MaccarioC. Sagittal tibiotalar translation and clinical outcomes in mobile and fixed-bearing total ankle replacement. Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;23(2):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UsuelliFG MaccarioC., ManziL TanEW. Posterior talar shifting in mobile-bearing total ankle replacement. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;37(3):281–287. doi: 10.1177/1071100715610426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]