On the basis of emerging evidence from patients with COVID-19, we postulate that endothelial cells are essential contributors to the initiation and propagation of severe COVID-19. Here, we discuss current insights into the link between endothelial cells, viral infection and inflammatory changes and propose novel therapeutic strategies.

Subject terms: Molecular biology, Cell biology

Here, Carmeliet and colleagues discuss the role of endothelial cells in inflammation and viral infection and propose novel therapeutic strategies for COVID-19.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the betacoronavirus SARS-CoV-2, is a worldwide challenge for health-care systems. The leading cause of mortality in patients with COVID-19 is hypoxic respiratory failure from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)1. To date, pulmonary endothelial cells (ECs) have been largely overlooked as a therapeutic target in COVID-19, yet emerging evidence suggests that these cells contribute to the initiation and propagation of ARDS by altering vessel barrier integrity, promoting a pro-coagulative state, inducing vascular inflammation (endotheliitis) and mediating inflammatory cell infiltration2,3. Therefore, a better mechanistic understanding of the vasculature is of utmost importance.

During homeostasis, the endothelium, surrounded by mural cells (pericytes), maintains vascular integrity and barrier function. It prevents inflammation by limiting EC–immune cell and EC–platelet interactions and inhibits coagulation by expressing coagulation inhibitors and blood clot-lysing enzymes and producing a glycocalyx (a protective layer of glycoproteins and glycolipids) with anti-coagulation properties2,3. Interestingly, recent studies using single-cell transcriptomics revealed endothelial phenotypes that exhibit immunomodulatory transcriptomic signatures typical for leukocyte recruitment, cytokine production, antigen presentation and even scavenger activity4. Compared with ECs from other organs, lung ECs are enriched in transcriptomic signatures indicating immunoregulation5, and a subtype of lung capillary ECs expresses high levels of genes involved in MHC class II-mediated antigen processing, loading and presentation4. This suggests a role for this EC subtype as antigen-presenting cells and a putative function in immune surveillance against respiratory pathogens. As ECs do not express the CD80/CD86 co-activators4, they cannot activate naive T cells but only antigen-experienced T cells and thus function as semi-professional antigen-presenting cells. Whether and to what extent this subtype of capillary ECs is involved in the immune response against SARS-CoV-2 infection is a focus of further investigation.

After the initial phase of viral infection, ~30% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 develop severe disease with progressive lung damage, in part owing to an overreacting inflammatory response1. Mechanistically, the pulmonary complications result from a vascular barrier breach, leading to tissue oedema (causing lungs to build up fluid), endotheliitis, activation of coagulation pathways with potential development of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and deregulated inflammatory cell infiltration. We hypothesize that, similar to the key role of ECs in ARDS induced by other causes, ECs play a central role in the pathogenesis of ARDS and multi-organ failure in patients with COVID-19.

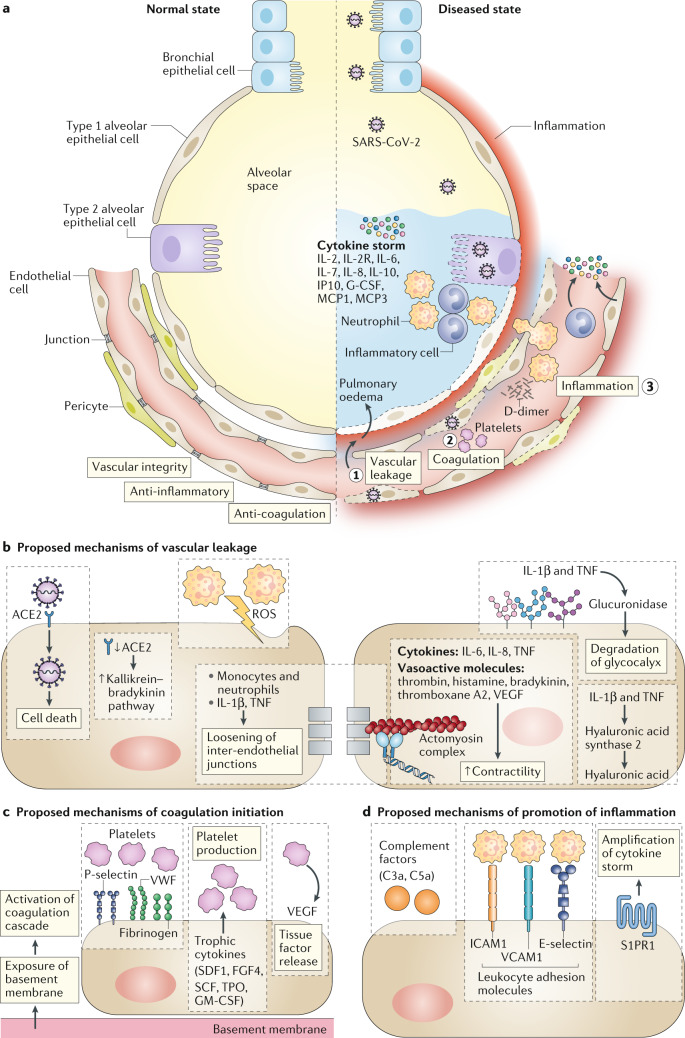

Vascular leakage and pulmonary oedema in patients with severe COVID-19 are caused by multiple mechanisms (Fig. 1). First, the virus can directly affect ECs as SARS-CoV-2-infected ECs were detected in several organs of deceased patients3. These ECs exhibited widespread endotheliitis characterized by EC dysfunction, lysis and death. Second, to enter cells, SARS-CoV-2 binds to the ACE2 receptor, which impairs the activity of ACE2 (an enzyme counteracting angiotensin vasopressors)6. Which vascular cell types express the ACE2 receptor remains to be studied in more detail. Reduced ACE2 activity indirectly activates the kallikrein–bradykinin pathway, increasing vascular permeability2. Third, activated neutrophils, recruited to pulmonary ECs, produce histotoxic mediators including reactive oxygen species (ROS). Fourth, immune cells, inflammatory cytokines and vasoactive molecules lead to enhanced EC contractility and the loosening of inter-endothelial junctions. In turn, this pulls ECs apart, leading to inter-endothelial gaps2. Finally, the cytokines IL-1β and TNF activate glucuronidases that degrade the glycocalyx but also upregulate hyaluronic acid synthase 2, leading to increased deposition of hyaluronic acid in the extracellular matrix and promoting fluid retention. Together, these mechanisms lead to increased vascular permeability and vascular leakage.

Fig. 1. Proposed vessel–lung tissue interface in normal state and in COVID-19 disease.

a | On the left, the normal interface between the alveolar space and endothelial cells is depicted; the right side highlights pathophysiological features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the lung, including loss of vascular integrity (1), activation of the coagulation pathway (2) and inflammation (3). b–d | Proposed contributing endothelial cell-specific mechanisms are detailed. ROS, reactive oxygen species; S1PR1, sphingosine 1 phosphate receptor 1; VWF, von Willebrand factor.

An established feature of severe COVID-19 is the activation of coagulation pathways with potential development of DIC. This is also related to EC activation and dysfunction because the disruption of vascular integrity and EC death leads to exposure of the thrombogenic basement membrane and results in the activation of the clotting cascade7. Moreover, ECs activated by IL-1β and TNF initiate coagulation by expressing P-selectin, von Willebrand factor and fibrinogen, to which platelets bind2. In turn, ECs release trophic cytokines that further augment platelet production. Platelets also release VEGF, which triggers ECs to upregulate the expression of tissue factor, the prime activator of the coagulation cascade, which is also expressed by activated pericytes2. In response, the body mounts countermeasures to dissolve fibrin-rich blood clots, explaining why high levels of fibrin breakdown products (D-dimers) are predictive of poor patient outcome. As a result of the DIC and clogging/congestion of the small capillaries by inflammatory cells, as well as possible thrombosis in larger vessels, lung tissue ischaemia develops, which triggers angiogenesis2 and potential EC hyperplasia. While the latter can aggravate ischaemia, angiogenesis can be a rescue mechanism to minimize ischaemia. However, the newly formed vessels can also promote inflammation by acting as conduits for inflammatory cells that are attracted by activated ECs2.

Many patients with severe COVID-19 show signs of a cytokine storm8. The high levels of cytokines amplify the destructive process by leading to further EC dysfunction, DIC, inflammation and vasodilation of the pulmonary capillary bed. This results in alveolar dysfunction, ARDS with hypoxic respiratory failure and ultimately multi-organ failure and death. EC dysfunction and activation likely co-determine this uncontrolled immune response. This is because ECs promote inflammation by expressing leukocyte adhesion molecules2, thereby facilitating the accumulation and extravasation of leukocytes, including neutrophils, which enhance tissue damage. Moreover, we hypothesize that denudation of the pulmonary vasculature could lead to activation of the complement system, promoting the accumulation of neutrophils and pro-inflammatory monocytes that enhance the cytokine storm. This is based on the observation that during influenza virus infection, pulmonary ECs induce an amplification loop, involving interferon-producing cells and virus-infected pulmonary epithelial cells9. Moreover, ECs seem to be gatekeepers of this immune response, as modulation of the sphingosine 1 phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1) in pulmonary ECs dampens the cytokine storm in influenza infection9. This raises the question whether pulmonary ECs have a similar function in the COVID-19 cytokine storm and whether S1PR1 could represent a therapeutic target. Another unexplained observation is the excessive lymphopenia in severely ill patients with COVID-19 and whether this relates to the recruitment of lymphocytes away from the blood by activated lung ECs.

Additional circumstantial evidence suggests a link between ECs, pericytes and COVID-19. First, risk factors for COVID-19 (old age, obesity, hypertension and diabetes mellitus) are all characterized by pre-existing vascular dysfunction with altered EC metabolism10. As hijacking of the host metabolism is essential for virus replication and propagation, an outstanding question is whether EC subtypes or other vascular cells in specific pathological conditions have a metabolic phenotype that is more attractive to SARS-CoV-2. Second, occasional clinical reports suggest an increased incidence of Kawasaki disease, a vasculitis, in young children with COVID-19. Third, severe COVID-19 is characterized by multi-organ failure, raising the question how and to what extent the damaged pulmonary endothelium no longer offers a barrier to viral spread from the primary infection site. Additionally, whether infected pericytes can promote coagulation remains to be studied. As such, the consequences of SARS-CoV-2 on the entire vasculature require further attention.

The proposed central role of ECs in COVID-19 disease escalation prompts the question whether vascular normalization strategies during the maladapted immune response could be useful. Indeed, a clinical trial (NCT04342897) is exploring the effect of targeting angiopoietin 2 in patients with COVID-19, based on the rationale that circulating levels of angiopoietin 2 correlate with increased pulmonary oedema and mortality in patients with ARDS. Several other clinical trials (NCT04344782, NCT04275414 and NCT04305106) are investigating bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds to VEGF and counteracts its vessel-permeabilizing effect, in patients with COVID-19. Normalization of the vascular wall through metabolic interventions could be considered as an additional route of intervention10. For instance, ECs treated with drugs targeting key metabolic enzymes of the glycolytic pathway adopt a ‘normalized’ phenotype with enhanced vascular integrity and reduced ischaemia and leakiness10. Although the hypothetical role and therapeutic targetability of the vasculature in COVID-19 require further validation, the possibility that ECs and other vascular cells are important players paves the way for future therapeutic opportunities.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Related links

ClinicalTrials.gov: https://clinicaltrials.gov/

Change history

6/4/2020

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41577-020-0356-8

References

- 1.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–2142. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pober JS, Sessa WC. Evolving functions of endothelial cells in inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:803–815. doi: 10.1038/nri2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varga Z, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goveia J, et al. An integrated gene expression landscape profiling approach to identify lung tumor endothelial cell heterogeneity and angiogenic candidates. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:421. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalucka J, et al. Single-cell transcriptome atlas of murine endothelial cells. Cell. 2020;180:764–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffmann M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nachman RL, Rafii S. Platelets, petechiae, and preservation of the vascular wall. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:1261–1270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehta P, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teijaro JR, et al. Endothelial cells are central orchestrators of cytokine amplification during influenza virus infection. Cell. 2011;146:980–991. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X, Sun X, Carmeliet P. Hallmarks of endothelial cell metabolism in health and disease. Cell Metab. 2019;30:414–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]