ABSTRACT

During mitotic cell division, the actomyosin cytoskeleton undergoes several dynamic changes that play key roles in progression through mitosis. Although the regulators of cytokinetic ring formation and contraction are well established, proteins that regulate cortical stability during anaphase and telophase have been understudied. Here, we describe a role for CLIC4 in regulating actin and actin regulators at the cortex and cytokinetic cleavage furrow during cytokinesis. We first describe CLIC4 as a new component of the cytokinetic cleavage furrow that is required for successful completion of mitotic cell division. We also demonstrate that CLIC4 regulates the remodeling of the sub-plasma-membrane actomyosin network within the furrow by recruiting MST4 kinase (also known as STK26) and regulating ezrin phosphorylation. This work identifies and characterizes new molecular players involved in regulating cortex stiffness and blebbing during the late stages of cytokinetic furrowing.

KEY WORDS: Actin, Cell division, Cleavage furrow

Highlighted Article: CLIC4 regulates remodeling of the sub-plasma-membrane actomyosin network within the cytokinetic furrow by recruiting MST4 kinase and regulating ezrin phosphorylation, thus regulating cortex stiffness and blebbing.

INTRODUCTION

Cytokinesis is the last step in mitotic cell division that relies on orchestrated changes in membrane traffic and cytoskeletal rearrangements, both of which are required to complete the separation of the two daughter cells. Failure in cytokinesis has wide-ranging effects, including apoptosis and ploidy. Understanding these cytoskeletal rearrangements and shape changes is paramount to understanding cell division during development and disease contexts such as cancer. A number of highly controlled shape changes owing to these cytoskeletal rearrangements occur during cell division, from rounding up in metaphase, to furrowing in anaphase, and finally to the formation of the intercellular bridge in telophase. During metaphase, mitotic rounding contributes to creating the geometric space necessary for spindle organization and morphometry (Lancaster and Baum, 2014). Some of the proteins that are known to regulate these changes in metaphase include non-muscle myosins IIA and IIB, as well as members of the ezrin–radixin–moesin (ERM) family of proteins. They do so by regulating actin dynamics at the cell cortex, where they assist in maintaining the cortical actomyosin network and rigidity of the plasma membrane. Loss of these proteins leads to altered shape changes and often a failure in cell division (Carreno et al., 2008; Fujiwara and Pollard, 1976; Kunda et al., 2008; Mabuchi and Okuno, 1977).

Following metaphase, cells undergo the process of cytoplasmic separation, also known as cytokinesis. Cytokinesis relies heavily on the formation and contraction of the cytokinetic actomyosin ring, an actin-rich structure that forms at telophase onset. A number of proteins have been shown to be required for cytokinetic ring formation and contraction, including RhoA, anillin and non-muscle myosin family members (Piekny and Glotzer, 2008; Straight et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2015; Wagner and Glotzer, 2016). RhoA is a key regulator of this process as its activation drives formation and constriction of the cytokinetic ring through an increase in actin polymerization and myosin activation. Anillin is a scaffolding protein that contributes to regulating the localization of RhoA, actin and septins to the contractile ring. Although furrows can initiate in the absence of anillin, cytokinesis often fails due to the necessity of its scaffolding partners.

An important consideration in telophase during furrow ingression is that the cortices of the dividing cells remain mostly rigid, while the furrow is constricting to separate the cytoplasm. These local changes in stiffness are regulated by the actomyosin cytoskeleton in conjunction with the ERM proteins, and ultimately aid in furrow ingression. Several studies have shown that moesin-dependent regulation of the actin cytoskeleton is required for cytokinesis (Rodrigues et al., 2015; Roubinet et al., 2011). Furthermore, moesin removal by kinetochore-coupled phosphatase helps soften the poles for expansion during furrow ingression (Rodrigues et al., 2015; Roubinet et al., 2011). An additional facet of this regulation is the pressure dynamics induced by the rigidity of the cell cortex. It is thought that self-induced ruptures and blebs of the cortex allow for pressure release and for cell division to continue. However, disruption of the actomyosin cortex via manipulation of these proteins can lead to abnormal blebbing events, which can lead to a failure in cell division (Hickson et al., 2006; Hiruma et al., 2017; Roubinet et al., 2011). While non-muscle myosins and ERM proteins have been extensively studied and are well known to regulate this blebbing phenomenon (Carreno et al., 2008; Jiao et al., 2018; Kunda et al., 2008; Taneja and Burnette, 2019), it is still poorly understood how these blebs are regulated during cytokinesis.

Upon completion of furrow ingression, the daughter cells remain connected by a thin and actin-rich intracellular bridge (ICB). The conversion of the contracting actomyosin ring to a stable, actin-rich ICB is a key step in mitotic cell division, and failure in this transition often leads to furrow regression and polyploidy. However, the molecular machinery mediating the conversion of a formin-based actomyosin ring to a stable sub-plasma membrane actin network in the ICB remains largely unknown. In our previous analysis of the midbody proteome, we identified a number of proteins that have the potential to regulate actin cytoskeletal dynamics during cell division. One such protein is chloride intracellular channel 4 (CLIC4). CLIC4 is a 28 kDa protein that belongs to the family of CLIC proteins. As its name might imply, it was initially described as a chloride channel; however, numerous recent studies have shown that CLIC4 may actually function as a regulator of actin dynamics. These studies implicated CLIC4 in regulating branched actin networks and filopodia formation, although how CLIC4 performs these functions remains to be defined (Argenzio et al., 2014, 2018; Chou et al., 2016; Tavasoli et al., 2016). In this study, we describe a role for CLIC4 in ensuring the fidelity of cell division through the regulation and recruitment of actin-interacting proteins during cell division. We show that CLIC4 is recruited to the cytokinetic furrow by RhoA at the onset of furrow formation. We also demonstrate that CLIC4 binds to MST4 (a kinase and known regulator of ERM proteins; also known as STK26) and mediates recruitment of MST4 to the ingressing furrow during telophase. The absence of CLIC4 results in decreased recruitment of phospho-ezrin and non-muscle myosin IIA and IIB to the furrow, leading to increased membrane blebbing and a failure to transition from cytokinetic actomyosin ring to ICB. Collectively, our data demonstrate that CLIC4 is a new component of the contractile cytokinetic ring that contributes to regulating cortical actomyosin dynamics during cell division.

RESULTS

CLIC4 is enriched at the cytokinetic furrow

We have recently completed a proteomic analysis of post-mitotic midbodies purified from HeLa cell media (Peterman et al., 2019). Post-mitotic midbodies are released into the media as a result of symmetric abscission, and therefore contain the membranous envelope derived from the plasma membrane of the intracellular bridge connecting two daughter cells during telophase (Fig. 1A). Consequently, post-mitotic midbodies are also expected to contain proteins that regulate cytokinetic actomyosin ring contraction during early telophase and disassembly during abscission. Consistent with this idea, numerous cytokinesis regulators, such as RhoA, MKLP1, Plk1, anillin, Rab11 and Rab35, were all identified in the midbody proteome (Capalbo et al., 2019; Peterman et al., 2019; Skop et al., 2004). Among these known cytokinesis regulators, CLIC4 was also identified as a potential midbody-localizing protein (Berryman and Goldenring, 2003; Peterman et al., 2019). As CLIC4 was previously implicated in regulating actin cytoskeleton dynamics during cell migration, we hypothesized that CLIC4 may also be involved in regulating actin networks during cytokinesis. To test this hypothesis, we first analysed the localization of CLIC4 during cytokinetic ring formation and contraction. To that end we used a fluorescent protein-tagged version of CLIC4 (N-terminus). As previously reported (Argenzio et al., 2014), Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP)–CLIC4 predominantly localizes at the plasma membrane as well as actin filaments at both the plasma membrane cortex and in filopodia during interphase (Fig. S1A). Consistent with the involvement of CLIC4 in regulating cytokinesis, CLIC4 is enriched at the cleavage furrow and the contractile ring in early and late anaphase (Fig. 1B,D,F; Fig. S1, Movies 1,2). To ensure that localization of GFP–CLIC4 is not a result of over-expression, we next used CRISPR/Cas9 to tag endogenous CLIC4 with GFP on the N-terminus (Fig. S1B). As shown in Fig. 1E,F, endogenously tagged CLIC4 was also targeted to the cleavage furrow during anaphase where it co-localized with anillin, one of the well-established contractile ring proteins. Interestingly, when cells expressing endogenous GFP–CLIC4 were treated with siRNA targeting anillin, we saw a slight but significant decrease in GFP–CLIC4 levels at the contractile ring, suggesting that anillin may contribute to regulating CLIC4 localization during anaphase (Fig. S1C).

Fig. 1.

Localization of CLIC4 throughout the cell cycle. (A) Schematic representation of abscission that generates an extracellular post-mitotic midbody. (B,C) HeLa cells expressing exogenous GFP–CLIC4 were fixed and stained with phalloidin–Alexa 568 (B) or anti-acetylated tubulin antibodies (C). Arrow in B points to an ingressing cleavage furrow. Arrow in C points to an abscission site. Asterisk marks the midbody. (D) HeLa cells expressing exogenous GFP–CLIC4 were analysed by time-lapse microscopy. Images shown are stills representing different sequential time points during anaphase. Arrow marks cleavage furrow. (E) HeLa cells expressing endogenously tagged GFP–CLIC4 were fixed and stained with anti-anillin antibody. Arrow points to the cleavage furrow. (F) 3D volume rendition of a GFP–CLIC4 expressing HeLa cell in anaphase. Red marks central spindle microtubules labeled with anti-acetylated tubulin antibodies. The 3D image is shown at an angle to better demonstrate the GFP–CLIC4 ring at the furrow. For different angles of the 3D rendering see Movie 1. Scale bars in B–F: 10 μm

During telophase and upon completion of cytokinetic ring contraction, GFP–CLIC4 remained associated with the intercellular bridge and the midbody (Fig. 1D), explaining its identification in midbody proteome (Peterman et al., 2019) and consistent with a previous report suggesting that CLIC4 is a midbody protein (Berryman and Goldenring, 2003). During abscission, GFP–CLIC4 is removed from the abscission site (Fig. 1C, lower panel). This observation is consistent with previous reports that actin filaments needs to be removed from the abscission site to allow for recruitment of the ESCRT-III complex and final separation of daughter cells (Dambournet et al., 2011; Schiel et al., 2012). Collectively, we propose that CLIC4 is a newly described component of the cytokinetic furrow that may regulate the actomyosin ring contraction, as well as formation and stabilization of the ICB.

RhoA is necessary and sufficient to localize CLIC4 at the cytokinetic cleavage furrow

As previous studies have reported that RhoA regulates CLIC4 localization in interphase cells (Argenzio et al., 2014), we hypothesized that activated RhoA at the cytokinetic furrow may be responsible for targeting of CLIC4 during cytokinesis. To test this hypothesis, we first confirmed that CLIC4 indeed co-localizes with active RhoA during anaphase. Using a trichloroacetic acid (TCA) fixation method that is known to preserve RhoA localization during cell division and anti-RhoA antibody, we observed endogenous GFP–CLIC4 co-localizing with RhoA (Fig. 2A). Next, we tested if RhoA activation is sufficient to drive CLIC4 relocalization. To do so, we used our endogenous GFP-tagged CLIC4 cell line in tandem with an optogenetic RhoA clustering assay (Bugaj et al., 2013). To that end, we used HeLa cells expressing Cry2mCH-RhoA. The exposure of cells to 488 nm wavelength light leads to clustering and activation of RhoA within the cytoplasm (Pertz et al., 2006) (see Materials and Methods section for detailed description). As shown in Fig. S1D, endogenous GFP–CLIC4 accumulated in light-induced activated RhoA complexes, suggesting that RhoA activation is sufficient to recruit CLIC4.

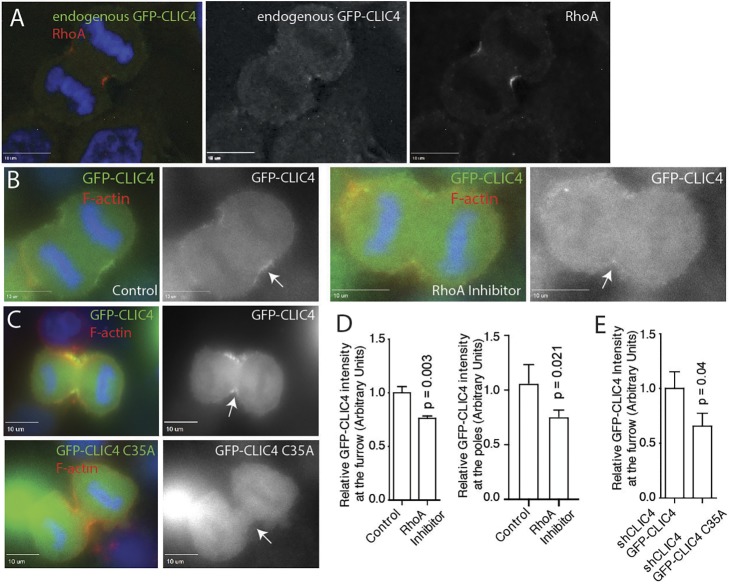

Fig. 2.

RhoA is necessary and sufficient for CLIC4 localization. (A) HeLa cells expressing endogenous GFP–CLIC4 were TCA-fixed and stained with RhoA antibodies. Image was deconvolved. (B) HeLa cells expressing endogenously labeled GFP–CLIC4 were imaged in anaphase in the presence or absence of RhoA inhibitor. Arrows point to cleavage furrows. (C) shCLIC4 HeLa cells were transfected with either wild-type GFP–CLIC4 or GFP–CLIC4 C35A. Cells were then fixed and stained with phalloidin–Alexa 568. Arrows point to cleavage furrow. (D,E) Quantification of GFP–CLIC4 (D,E) or GFP–CLIC4 C35A (E) fluorescence in cleavage furrow and poles of dividing cell. Data shown are the means and standard deviations of 15–30 anaphase cells randomly picked during three independent experiments. Scale bars in A–C: 10 μm

We next tested if RhoA is necessary for the recruitment of CLIC4 to the cytokinetic ring. First, we used a low dose (0.5 µg/ml for 4 h) of a Rho inhibitor that still allowed furrow formation, although at reduced rates and efficiency. Consistent with the involvement of RhoA in mediating CLIC4 recruitment, RhoA inhibitor decreased the levels of endogenous GFP–CLIC4 at the furrow (Fig. 2B,D). Interestingly, RhoA inhibition also affected GFP–CLIC4 localization at the poles, suggesting that the levels of activated RhoA probably determine the levels of CLIC4 at the plasma membrane throughout the entire cell during cytokinesis. Second, we examined the localization of GFP–CLIC4-C35A, a mutation that was previously shown block CLIC4 function (Argenzio et al., 2014). GFP–CLIC4 or GFP–CLIC4-C35A were expressed in CLIC4-knockdown HeLa cells (shCLIC4), and fluorescent intensity was measured and compared at the contractile ring as well as at the poles of the dividing cell. As shown in Fig. 2C,E, GFP–CLIC4-C35A was not enriched at the contractile ring compared with GFP–CLIC4, consistent with RhoA involvement in recruiting CLIC4 to the furrow during anaphase. Together, these data suggest that RhoA is responsible for CLIC4 recruitment to the ingression furrow during anaphase.

CLIC4 is required for actin-dependent stabilization of the intracellular bridge

Our data demonstrate that CLIC4 is recruited to the plasma membrane at the cytokinetic furrow during telophase and remains associated with the intracellular bridge during abscission. However, the function of CLIC4 remains unclear. We next asked if CLIC4 is required for any aspect of cytokinesis. To determine that, we created a HeLa cell line stably expressing CLIC4 shRNA (shCLIC4) (Fig. S2A,B). As shown in Fig. 3A, CLIC4 knockdown resulted in an increase in multi-nucleation in HeLa cells, indicating defects in cytokinesis. In contrast, knockdown of another closely related CLIC family member, CLIC3, did not induce a multi-nucleation phenotype (Fig. 3A). Finally, this increase in multi-nucleation could be rescued by reintroduction of GFP–CLIC4, but not GFP–CLIC4-C35A (Fig. 3A). It is also worth noting that, despite extensive effort, we were unable to create a viable CLIC4 knockout HeLa cell line using CRISPR/Cas9, suggesting that complete deletion of CLIC4 may block cell division in HeLa cells. In contrast, our shCLIC4 cell line still expresses ∼5% of CLIC4, allowing cells to eventually complete cytokinesis.

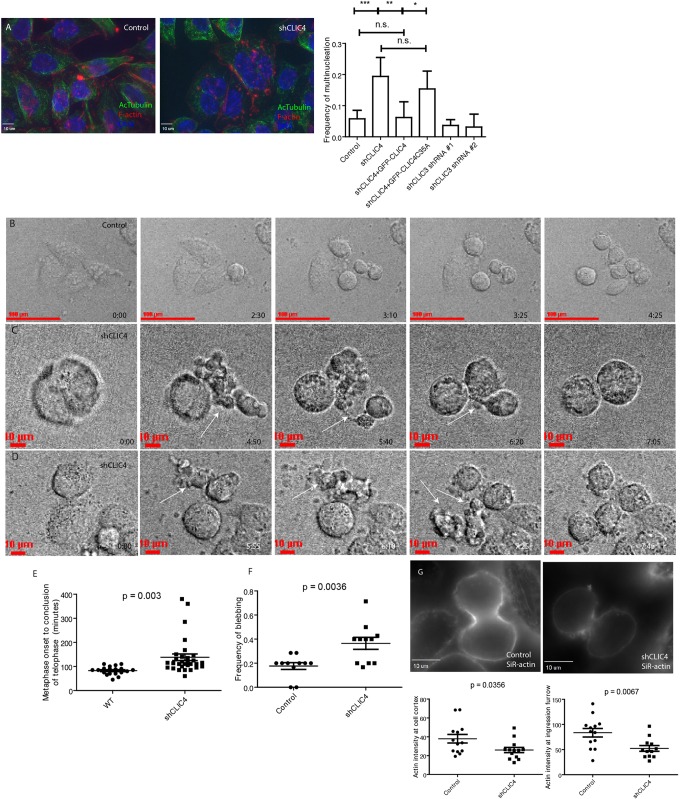

Fig. 3.

Depletion of CLIC4 leads to mitotic defects. (A) HeLa cells were fixed and co-stained with phalloidin–Alexa 568 and anti-acetylated tubulin antibodies. The number of multi-nucleated cells were then counted. Graph on the right shows quantification and statistical analysis of multi-nucleation induced by shRNA-dependent CLIC4 depletion. Data shown are the means and standard deviations of at least 75 cells counted in randomly chosen fields from three different experiments. *P<0.05; **P<0.025; ***P<0.01; ns, not significant. (B–D) Control (B) or shCLIC4 (C,D) HeLa cells were analysed by time-lapse microscopy. Images shown are the stills from different time points of cells undergoing mitotic cell division. Arrows point to blebs during anaphase. (E) Quantification of time required for cells to go from metaphase to abscission. Data shown are means and standard deviations derived from randomly picked cells in two different experiments. WT, wild type. (F) Quantification of blebbing frequency in control or shCLIC4 HeLa cells. Data shown are means and standard deviations derived from randomly picked cells in three different experiments. (G) Control or shCLIC4 cells were incubated with SiR-actin and live imaged. Quantification of actin intensity at the cell cortex and furrows are shown. Data shown are means and standard deviations of individual cell intensities from randomly picked cells in three different experiments. Scale bars in A,C,D,G: 10 μm. Scale bar in B: 100 μm.

As CLIC4 was initially described as a putative chloride ion channel, we next tested the effect of IAA94, a chloride channel inhibitor, on cell division. Treatment of cells with this inhibitor did not induce multi-nucleation (Fig. S2C), nor did it affect CLIC4 recruitment to the furrow (Fig. S2D,F), suggesting that, at least in the context of cell division, CLIC4 does not function as chloride channel.

To determine what part of cytokinesis depends on CLIC4, we next assessed cell division using time-lapse microscopy. As shown in Fig. 3E, CLIC4 depletion led to an increase in the amount of time it took cells to complete mitosis (Movies 4,5). While all shCLIC4 cells formed an ingression furrow, about 20% of furrows regressed at late anaphase resulting in multi-nucleation (Fig. 3C; Movies 4,5; for control see Fig. 3B and Movie 3). The shCLIC4 cells that did divide exhibited an extreme ‘blebbing’ phenotype during anaphase (Fig. 3C,D,F). The formation of blebs during telophase has been previously observed and has been suggested to function as a pressure release mechanism at the end of furrowing (Cattin et al., 2015; Charras, 2008; Paluch et al., 2005; Sedzinski et al., 2011). These blebs typically occur at the poles of the dividing cell and are rarely observed at the furrow. In shCLIC4 cells, enlarged blebs could be observed at the furrow as well as at the poles of the cell, especially during the transition from the contracting cytokinetic ring to stable intercellular bridge (Fig. 3C,D,F; Movies 4,5). As local changes in the cortical actin network are responsible for furrow ingression, cortical rigidity, and bleb formation and pressure release during anaphase, we imaged the anaphase cortical actin network using SiR-actin in live cells. We found that shCLIC4 cells had decreased levels of SiR-actin in both the furrow and poles of the cells, leading to the idea that these cells have a weaker cortical network and are therefore more likely to have an extreme blebbing phenotype (Fig. 3G).

To further test whether CLIC4 is required for cell division we used a combination of time-lapse microscopy and an optogenetic trap (termed ‘Mitotrap’) assay. In this assay, HeLa cells expressing endogenously tagged GFP–CLIC4 were transfected with Cry2 GFP-VHH and Tom20-CIB-stop (Fig. 4A). Cells that receive both constructs will recruit endogenous GFP–CLIC4 to mitochondria when pulsed with a 488 nm laser (Fig. 4B), thereby depleting CLIC4 from its normal localization at the plasma membrane. As shown in Fig. 4C–E, cells that have CLIC4 anchored to the mitochondria also exhibit blebbing phenotypes, increase in mitosis time and, in some cases, regression of the cytokinetic furrow at late anaphase (Movies 6,7). Taken together, these data indicate that CLIC4 is an important player in the fidelity of cell division, and probably plays a role in formation of the stable intercellular bridge and in regulating cytoskeletal remodeling.

Fig. 4.

An optogenetic targeting of CLIC4 to the mitochondria delays cell division. (A) Schematic of Mitotrap used in this experiment. In all cases cells expressing endogenously tagged GFP–CLIC4 were co-transfected with Cry2-GFP-VHH and CIB-Tom20 plasmids and pulsed with a 488 nm laser to re-target GFP–CLIC4 at the mitochondria. (B) Interphase cell exposed to 488 nm to activate Mitotrap. Mitochondria are labeled in red and endogenous GFP–CLIC4 in green. (C,D) Still images from time-lapse microscopy where Mitotrap was activated. Arrows point to blebs or cytokinesis failure induced by GFP–CLIC4 Mitotrap. Scale bars: 100 μm. (E) Quantification of time required for cells to complete mitotic cell division in control and Mitotrapped cells. Data shown are the means and standard deviations.

CLIC4 is required for the recruitment of non-muscle myosin IIA and IIB to the cytokinetic furrow

Our data demonstrate that CLIC4 is localized to the cytokinetic furrow and the absence of CLIC4 leads to increased blebbing and furrow regression, presumably due to the failure to transition from contractile actomyosin ring to ICB. Next, we decided to identify the mechanisms that mediate CLIC4 function during cell division. Recent studies identified several proteins involved in the regulation of mitotic blebbing process, namely the non-muscle myosins IIA (NMMIIA) and IIB (NMMIIB) (Taneja et al., 2020; Taneja and Burnette, 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Furthermore, NMMIIA and NMMIIB have previously been shown to be responsible for regulating cortical rigidity during anaphase and telophase (Mitchison et al., 2008). We first tested whether CLIC4 contributes to recruitment and/or maintenance of NMMIIA and NMMIIB at the cleavage furrow. Consistent with this idea, GFP–CLIC4 co-localizes with NMMIIB during anaphase (Fig. 5A). We measured NMMIIA and NMMIIB levels in the furrow in control and shCLIC4 cells and found that CLIC4 depletion leads to a decrease in NMMIIA and NMMIIB levels at the furrow during cytokinesis (Fig. 5B–F), suggesting that CLIC4 may contribute to the spatiotemporal control of NMMIIA and NMMIIB during telophase.

Fig. 5.

Loss of CLIC4 results in decreases in NMMIIA and -IIB at cortex and furrow. (A) HeLa cells expressing GFP–CLIC4 were fixed and stained with anti-NMMIIB antibodies. (B–E) Control (B,D) or shCLIC4 (C,E) HeLa cells were fixed and stained with either anti-NMMIIA (B,C) or anti-NMMIIB (D,E) antibodies. Arrows point to ingressing furrow during anaphase. (F) Quantification of NMMIIA or NMMIIB at the furrow or at the poles of the anaphase cell. The data shown are the means and standard deviations of 20–40 randomly picked cells from three different experiments. Scale bars in A–E: 10 μm.

CLIC4 regulates phospho-ezrin recruitment to the plasma membrane

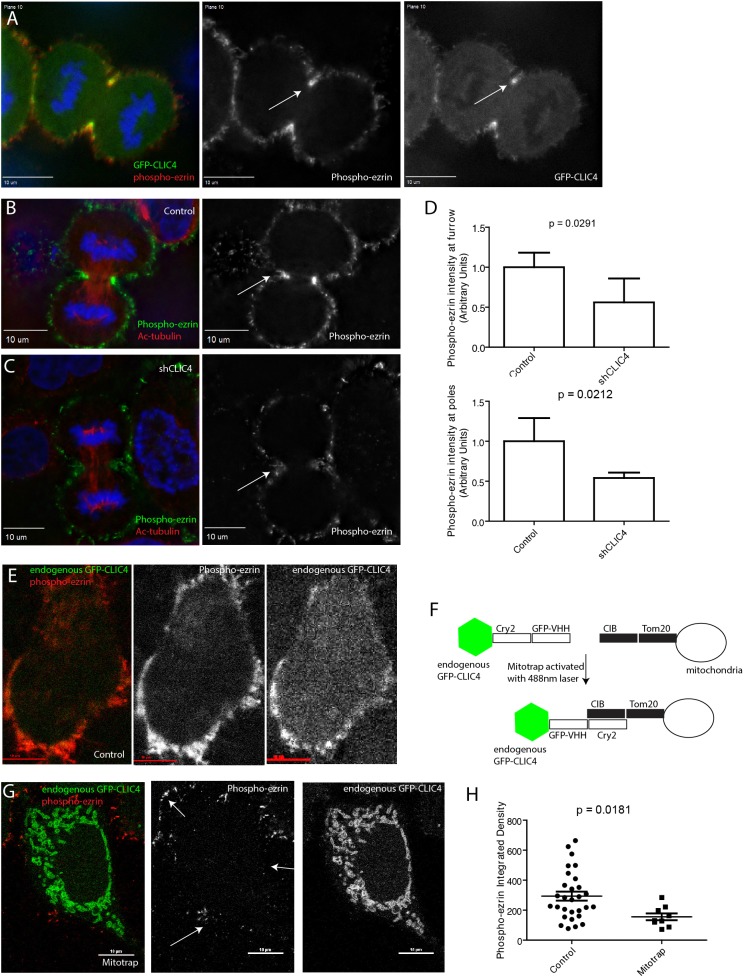

An additional mediator of cortical rigidity during cell division is ezrin, a member of the ERM family of proteins. There have been previous reports of CLIC4 and ezrin functional interactions. For example, it was shown that loss of CLIC4 in kidney and glomerular endothelium modulates activated ezrin levels (Tavasoli et al., 2016). Furthermore, it has been shown that loss of moesin in Drosophila led to mitotic defects and a propensity for cells to bleb during anaphase (Carreno et al., 2008; Kunda et al., 2008). To begin examining a potential CLIC4 and ezrin functional interaction, we first analysed phospho-ezrin localization during cell division and found that GFP–CLIC4 and phospho-ezrin co-localize during telophase (Fig. 6A, see arrow). Next, we examined phospho-ezrin levels in shCLIC4 cells. We found that CLIC4 depletion led to a decrease in phospho-ezrin levels at the cell cortex and ingression furrow, suggesting that CLIC4 is necessary for the phosphorylation and activation of ezrin at the cytokinetic furrow (Fig. 6B–D). To further confirm that CLIC4 is required for proper phospho-ezrin localization at the cell cortex, we used our Mitotrap approach to acutely inactivate all cellular CLIC4 (Fig. 6E,F). To that end, cells expressing endogenous GFP–CLIC4 were transfected with the Mitotrap constructs and exposed to 488 nm laser to ‘trap’ CLIC4 at the mitochondria. Cells were then fixed and stained for phospho-ezrin. As shown in Fig. 6G,H, inactivation of CLIC4 led to a decrease in the amount of phospho-ezrin at the plasma membrane. As CLIC4 was initially described as a putative chloride ion channel, we also tested the effect of IAA94, a chloride channel inhibitor, on the levels and localization of phospho-ezrin. As shown in Fig. S2E,F, IAA94 had no effect on activation of ezrin at the furrow, consistent with the idea that during cell division CLIC4 does not function as an ion channel but rather plays a role in regulating ezrin phosphorylation and actin dynamics at the cytokinetic furrow.

Fig. 6.

CLIC4 is necessary for efficient phospho-ezrin recruitment to the cleavage furrow. (A) HeLa cells expressing GFP–CLIC4 were fixed and stained with anti-phospho-ezrin antibodies. Arrows point to the cleavage furrow. (B,C) Control or shCLIC4 cells were fixed and stained with anti-acetylated tubulin and anti-phospho-ezrin antibodies. Arrows point to the furrow. (D) Quantification of phospho-ezrin signal intensity in cleavage furrow and poles of the cell. Data shown are the means and standard deviations derived from three different experiments. For every experiment phospho-ezrin fluorescence intensity in shCLIC4 data was normalized against phospho-ezrin fluorescence intensity in control cells. (E–G) The GFP–CLIC4 Mitotrap assay designed to test the effect of CLIC4 depletion on the levels of phospho-ezrin at the plasma membrane. Panel F shows a schematic of Mitotrap set-up, where endogenous GFP–CLIC4 cells are transiently transfected with the Mitotrap plasmids and pulsed with a 488 nm laser to trap CLIC4 at the mitochondria. Panels E and G show localization of endogenously tagged GFP–CLIC4 and phospho-ezrin in cells before and after exposure to 488 nm wavelength pulse. (H) Quantification of phospho-ezrin levels at the plasma membrane before and after exposure to 488 nm to activate GFP–CLIC4 Mitotrap. Data shown are the means and standard deviations derived from three different experiments. Scale bars in A–C,E,G: 10 μm.

To further confirm that CLIC4 is involved in regulating phospho-ezrin targeting to the cytokinetic furrow, we next knocked out CLIC4 in Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells. MDCK cells are an epithelial cell line that retain the ability to form polarized epithelial monolayers (Fig. S4A). Consistent with our data using HeLa cells, GFP–CLIC4 also localizes to the cleavage furrow in MDCK polarized monolayers (Fig. S4B). Unlike HeLa cells, dividing MDCK cells do not form blebs, probably due to the fact that they are still part of the epithelial monolayer and maintain tight junction and adherens junctions with neighboring interphase cells (Fig. S4B). Importantly, MDCK CLIC4-KO cells in telophase formed multiple membranous protrusions (Fig. S4D), suggesting that CLIC4 is also required to maintain the rigidity of sub-plasma membrane cytoskeleton in epithelial cells. Finally, CLIC4-KO also led to a dramatic decrease in phospho-ezrin levels at the cytokinetic furrow in MDCK cells (Fig. S4C).

MST4 kinase is a CLIC4-binding protein that could regulate ezrin activation during anaphase

As our data demonstrate the requirement of CLIC4 for successful completion of cytokinesis, we next decided to identify the molecular machinery governing CLIC4 function during mitosis. To that end, we used HeLa cells stably expressing pLVX:GFP-CLIC4 and performed immunoprecipitation using a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged anti-GFP nanobody followed by mass spectrometry in order to identify potential binding partners of CLIC4 (Table S1). Our proteomic analysis identified numerous actin regulators as putative CLIC4-interacting proteins (Fig. 7A). Importantly, a putative CLIC4-interacting protein identified in our proteomics was MST4, one of the kinases responsible for phosphorylating and activating ezrin, affecting the formation/activation of the cortical actomyosin network (ten Klooster et al., 2009). The Dictyostelium discoideum homolog of MST4 was shown to be necessary for cell division (Rohlfs et al., 2007). Furthermore, recent work in Caenorhabditis elegans has shown that MST4 (C. elegans GCK-1) localizes to the contractile ring (Rehain-Bell et al., 2019), and that depletion of GCK-1 leads to collapse of intercellular canals in these animals. These data raise the possibility that MST4 may be targeted and/or activated by CLIC4 at the cytokinetic ring. To test this hypothesis, we first used a glutathione bead pull-down assay to demonstrate that recombinant purified GST–CLIC4 binds to MST4 in cell lysates (Fig. 7B). As MST4 localization during mammalian cell division was never investigated, we next examined the localization of MST4 in mammalian cells throughout mitosis and found it to be enriched at the cytokinetic contractile ring (Fig. 7C, see arrow). Interestingly, MST4 translocates to the furrow only at late telophase. This coincides with the timing of the formation of blebs outside the furrow, the process that appears to be regulated by CLIC4. To test whether MST4 recruitment to the furrow is mediated by CLIC4 we analysed MST4 localization in shCLIC4 cells. Depletion of CLIC4 results in a moderate but significant decrease in MST4 at the furrow in late telophase (Fig. 7D,E).

Fig. 7.

CLIC4 interacts with MST4 and affects its localization during anaphase. (A) Putative candidates revealed via immunoprecipitation of GFP–CLIC4 followed by mass spectrometry. (B) Glutathione bead pulldown assay using HeLa cell lysate and either GST only or GST–CLIC4. Coomassie staining showing equal loading as well as quality of the recombinant proteins used in the pulldown assay. (C) HeLa cells were fixed and stained with phalloidin–Alexa 568 and anti-MST4 antibodies. Arrow points to MST4 at the cleavage furrow. (D) Control or shCLIC4 HeLa cells were fixed and stained with anti-MST4 antibody. Arrows point to the cleavage furrow. (E) Quantification of MST4 enrichment in the furrow in control, shCLIC4, siAnillin and shCLIC4/siAnillin cells. Data shown are from four individual experiments, horizontal bar indicates the mean. n is the total number of cells quantified. Scale bars in C,D: 10 µm.

While depletion of CLIC4 decreased the amount of MST4 at the furrow during late anaphase, the effect is moderate. We wondered whether other furrow proteins may also contribute to MST4 targeting during cell division. Recent work in C. elegans embryos suggested that anillin may bind to MST4 and mediate MST4 recruitment to cytokinetic furrow (Rehain-Bell et al., 2019). To test whether anillin has a similar function in mammalian cells, we analysed the localization of MST4 during anaphase in HeLa cells transfected with anillin siRNA. As shown in Fig. 7E, anillin depletion alone had little effect on MST4 recruitment during cell division. Intriguingly, co-knockdown of both anillin and CLIC4 resulted in a much greater decrease in MST4 localization at the cytokinetic furrow than knockdown of either of these proteins alone (Fig. 7E). These findings suggest that in mammalian cells CLIC4 is likely to play a primary role in mediating MST4 targeting during late anaphase. However, it is clear that anillin is also involved in MST4 targeting, especially in the context of CLIC4 depletion.

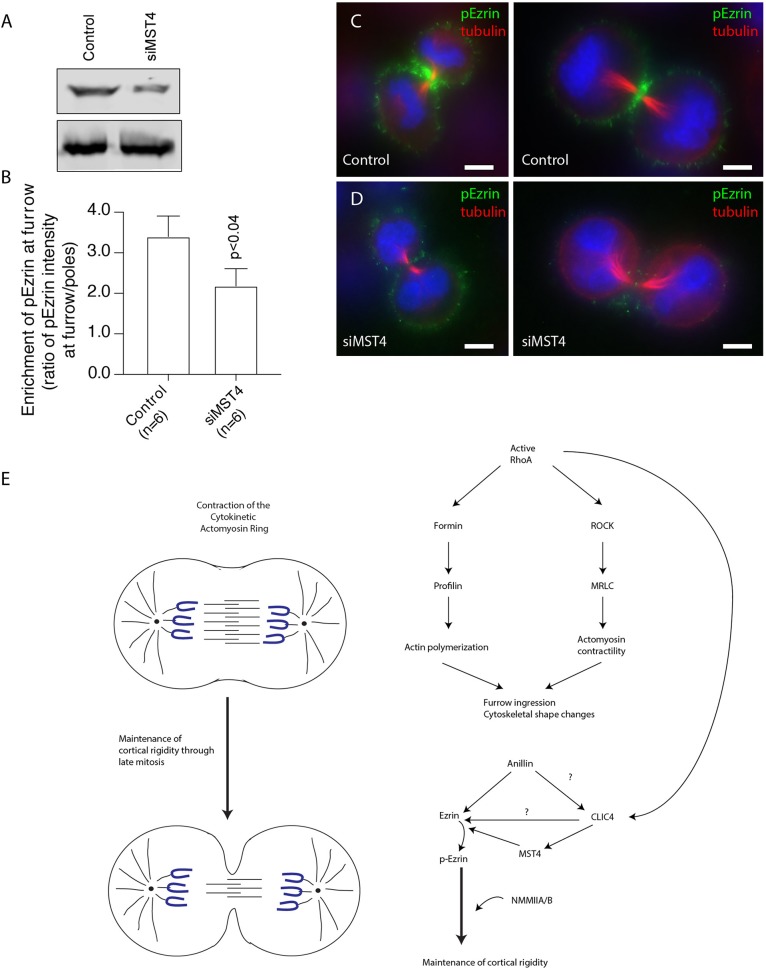

To further confirm that CLIC4 regulates phospho-ezrin levels by recruiting MST4 to the cleavage furrow, we used siRNA to transiently knock down MST4 in HeLa cells (Fig. 8A) and analysed the enrichment of phospho-ezrin at the furrow. As shown in Fig. 8B–D, MST4 depletion significantly reduced phospho-ezrin levels in the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis. Taken together, these data suggest that depletion of CLIC4 specifically at the cell cortex also results in loss of activated ezrin, providing a potential explanation for the increase in blebbing and failure in cell division.

Fig. 8.

MST4 is required for phospho-ezrin recruitment to cytokinetic furrow. (A) Triton X-100 lysates from HeLa control cells or cells transfected with MST4 siRNA were analysed by western blotting with anti-MST4 and anti-tubulin antibodies. (B) Quantification of the enrichment of phospho-ezrin at the furrow. Data shown are the means and standard deviations, and n indicates the number of cells analysed. (C,D) Control HeLa cells (C) or cells transfected with MST4 siRNA (D) were fixed and stained with anti-phospho-ezrin (green) and anti-tubulin (red) antibodies. Scale bars: 5 µm. (E) Schematic representation of the proposed role for CLIC4 during cytokinesis.

DISCUSSION

Cytokinesis is an incredibly complex process that must be regulated appropriately in order to maintain mitotic fidelity. The actin cytoskeleton plays a key role during cytokinesis, forming the cytokinetic contractile ring that drives the separation of the mother cell into two daughter cells. Additionally, it is becoming well established that the cortical actomyosin network is very important for successful completion of cytokinesis. Dynamic changes in the cortical actin cytoskeleton allow dividing cells to undergo dramatic shape changes, from rounding up during metaphase to the elongation during anaphase and finally flattening during late telophase and abscission (Fig. 8E). At the end of cleavage furrow ingression, the cytokinetic contractile ring needs to be remodeled and converted to an actin network that stabilizes the newly formed intercellular bridge until the abscission step of cytokinesis. The failure of intercellular bridge stabilization often leads to regression of cleavage furrow, leading to polyploidy. Interestingly, in some developmental instances, the abscission step is delayed, leading to the formation of stable syncytial connections between cells (Amini et al., 2014; Haglund et al., 2011, 2010; Rehain-Bell et al., 2017). How the cortical actin cytoskeleton coordinates with the cytokinetic contractile ring to simultaneously allow various cell shape changes as well as furrow ingression is still under investigation by our laboratory and others. In this study, we have identified CLIC4 as a new component of cytokinetic furrow that plays a key role in regulating the actomyosin cytoskeleton and maintaining this network during cell division.

We originally identified CLIC4 as putative midbody-associated protein from our midbody proteomics analysis (Peterman et al., 2019) and have confirmed that CLIC4 is indeed present at the midbody during late telophase, consistent with a previous study (Berryman and Goldenring, 2003). Thus, we initially studied CLIC4 as a putative regulator of abscission. However, we found no evidence that CLIC4 is directly required for abscission (data not shown). In contrast, our localization analysis suggested that CLIC4 is actually removed from the abscission site (Fig. 1C), although the mechanism mediating CLIC4 exclusion during abscission remains unclear. As it has been shown that actin filaments need to be removed from the abscission site (Dambournet et al., 2011; Schiel et al., 2012) and CLIC4 is known to regulate actin polymerization, it is tempting to speculate that CLIC4 exclusion from the abscission site may contribute to the regulation of determining the timing and location of the abscission.

Our previously published midbody proteome identified a number of proteins that may be involved in regulating actin dynamics during furrow ingression. As CLIC4 has been implicated in regulating actin dynamics in interphase cells, we have explored the possibility that CLIC4 may regulate actin dynamics during cytokinesis and have identified CLIC4 as a new component of cytokinetic furrow (Fig. 1). We show that CLIC4 localizes to the cleavage furrow during the onset of cytokinetic ring contraction and that CLIC4 recruitment is dependent on RhoA activation (Fig. 2). We propose that in addition to activating NMMIIA and -IIB and inducing formin-dependent actin polymerization, RhoA also drives the accumulation of CLIC4 at the furrow (Fig. 8E). Interestingly, RhoA also seems to affect CLIC4 localization at the poles of cytokinetic cell. Thus, it is likely that by modulating the levels of RhoA at different plasma membrane domains, dividing cells can also modulate CLIC4 recruitment and, presumably, stiffness of the cell cortex. Finally, CLIC4 could also be observed in filopodia-like structures at the base of the furrow. This observation is consistent with the previously published suggestion that CLIC4 regulates filopodia formation during cell migration (Argenzio et al., 2018), although it remains unclear whether filopodia-associated CLIC4 plays any role in cytokinesis.

Following the discovery that CLIC4 is a component of the cytokinetic furrow, we next asked what role CLIC4 plays during cytokinesis. Upon depletion of CLIC4, we found an increase in the percentage of multi-nucleated cells as well as an increase in division times (Fig. 3), phenotypes typically observed as a result of failure in cytokinetic ring contraction. Surprisingly, our time-lapse analysis demonstrated that CLIC4 depletion has little effect on furrow formation and initial ingression in HeLa cells. Instead, some shCLIC4 cells underwent furrow regression. Furthermore, cells that managed to divide exhibited a high blebbing phenotype (Fig. 3C,D,F). Blebs are commonly observed during late anaphase and are believed to serve the role of pressure release valves due to rapid decrease in cell volume (Cattin et al., 2015; Charras, 2008; Charras et al., 2006; Mitchison et al., 2008). However, the burst of blebbing is usually brief and restricted to the poles of the dividing cell. In contrast, shCLIC4 cells form much larger blebs, with many of them occurring at the furrow (Fig. 3C,D,F), suggesting that CLIC4 may predominantly function to regulate the cortex stiffness and inhibit blebbing at the furrow during its conversion to the stable intercellular bridge. Consistent with this, we observed decreased intensity of the cortical actin network in shCLIC4 cells in telophase (Fig. 3G). As NMMIIA and -IIB were previously shown to regulate bleb formation (Charras et al., 2006; Mitchison et al., 2008; Taneja and Burnette, 2019; Taneja et al., 2020), we also examined the recruitment of NMMIIA and -IIB in shCLIC4 cells. Consistent with the involvement of CLIC4 in the regulation of blebbing, loss of CLIC4 resulted in the decrease of the NMMIIA and -IIB at the furrow cortex in late anaphase (Fig. 5). Based on these data we propose that CLIC4 regulates furrow cortex stiffness, and consequently blebbing, during anaphase. We also speculate that CLIC4-dependent machinery plays a key role during the formation and stabilization of the intercellular bridge (Fig. 8).

CLIC4 has been initially described as a putative chloride channel, but recent work has determined that it has other functions, including the regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics. Indeed, CLIC4 has been thought to regulate actin polymerization in several different contexts and appears to predominantly enhance formation of formin-induced actin polymerization while inhibiting Arp2/3-dependent formation of branched actin networks (Argenzio et al., 2018; Chou et al., 2016). What remains unclear is how CLIC4 regulates actin dynamics as it does not affect actin polymerization directly, nor does it bind directly to polymerized actin filaments (Argenzio et al., 2014; Suginta et al., 2001). Some recent work has suggested that CLIC4 may bind to profilin (Argenzio et al., 2018), although it remains unclear whether this interaction plays any role in regulating actin during cell division. In this study we identified MST4 as a CLIC4-interacting protein, and have shown that CLIC4 contributes to mediating the recruitment of MST4 to the cytokinetic contractile ring (Figs 7 and 8). Interestingly, while CLIC4 is enriched at the cytokinetic contractile ring from the onset of anaphase, MST4 is only recruited there at late anaphase. This is consistent with the putative role of MST4 in regulating actin cytoskeleton remodeling during the formation of a stable intercellular bridge. These studies in C. elegans have pointed to a role for MST4/GCK-1 in stabilizing intercellular ring canals during development, and MST4/GCK-1 was shown to be localized to the contractile ring, confirming our mammalian localization (Rehain-Bell et al., 2017, 2019).

MST4 is one of the kinases capable of phosphorylating ezrin. The role of activated ezrin in mediating the attachment of actin filaments to the plasma membrane is now well defined (Fehon et al., 2010) and seems to depend on the ability of ezrin to co-bind filamentous actin and phosphatidyl-inositol 4,5-di-phosphate (PIP2), as well as several plasma membrane proteins. Importantly, PIP2 is required for successful completion of cytokinesis and was shown to be enriched at the intracellular bridge (Kouranti et al., 2006). It is possible that the recruitment of MST4 to the furrow at late anaphase ensures the stabilization of filamentous actin and its attachment to the plasma membrane in forming the intracellular bridge (Fig. 8). Similarly, activation of this CLIC4–MST4–ezrin pathway would increase furrow stiffness, inhibiting blebbing at the furrow membranes. However, we observed only a slight effect on MST4 recruitment during anaphase in shCLIC4 cells. However, we saw a much larger effect on phospho-ezrin levels in the furrow in HeLa-shCLIC4 and MDCK-CLIC4-KO cells. This suggests an alternative mechanism for CLIC4 in modulating phospho-ezrin expression and localization during anaphase. One obvious mechanism would be for a direct CLIC4–ezrin binding interaction. However, ezrin did not pass our cut-off in our mass spectrometry data and we could not demonstrate that CLIC4 binds to ezrin (Fig. S3). Although we cannot fully rule out that CLIC4 binds directly to ezrin, it is likely that in addition to MST4, CLIC4 may also recruit or regulate some other phospho-ezrin regulator.

We have also shown that CLIC4 contributes to NMMIIA and -IIB recruitment to the furrow. However, how CLIC4 regulates NMMIIA and -IIB remains unclear. We did not pull down any kinases that might be responsible for phosphorylation and activation of NMMIIA and -IIB, but we cannot rule out the possibility that CLIC4 can regulate myosin in this fashion. Alternatively, CLIC4 may regulate NMMIIA and -IIB indirectly by modulating the cortical actin cytoskeleton.

We conclude that CLIC4 is a novel component of the cytokinetic furrow that regulates cortical rigidity during cell division. Consistent with this hypothesis, a recent study has also demonstrated the involvement of CLIC4 in regulating ERM recruitment and activation during cytokinetic furrowing and blebbing (Uretmen et al., 2020). We propose that CLIC4 functions, at least in part, by recruiting MST4 and regulating ezrin activation at the furrow plasma membrane (Fig. 8). However, many questions remain. Does CLIC4 regulate recruitment of other actin regulators? What are the roles, if any, of other CLIC family members during cell division? Does CLIC4 have similar functions in vivo, especially in the context of formation of long-lived intracellular bridges or ring canals? Finally, what are the molecular mechanisms driving CLIC4-mediated recruitment of phospho-ezrin to the cell cortex? With the identification of a RhoA–CLIC4–MST4–ezrin pathway, we and others can start to answer these questions and systematically analyse the role of CLIC4 during cytokinesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and treatments

HeLa and MDCK cells were kept in a humidified incubator at 5% CO2 and 37°C, routinely tested for mycoplasma, and maintained in DMEM with 5% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. To create the GFP-CLIC4 cell line, HeLa or MDCK cells were transduced with the lentivirus pLVX:GFP-CLIC4. Populations were selected with puromycin.

To create shCLIC4 stable knockdown cell lines, HeLa cells were transduced with the lentivirus TRCN0000044358. Populations were selected with puromycin, and stable clones were isolated. For cell synchronization, a double thymidine–nocodazole block was used (Schiel et al., 2012). Cell lysates were harvested when cells entered anaphase. For RhoA inhibition, Rho Inhibitor I (cytoskeleton) was used at a final concentration of 0.5 µg/ml for 6 h. IAA94 was used at a concentration of 50 µM for 24 h. The anillin siRNA sequence is as follows: CGAUGCCUCUUUGAAUAAAUU and was used at a final concentration of 250 nM.

To knock out CLIC4, MDCK cells expressing dox-inducible Cas9 were co-transfected with two CLIC4 gRNAs (GCUGUCGAUGCCGCUGAAGUUUUAGAGCUAUGCUGUUUUG and UGACGAAGAGCUCGAUGAGUUUUAGAGCUAUGCUGUUUUG). Cells were then plated at low density and the resulting clones were isolated and tested for presence of CLIC4 by western blot.

To knock down MST4 in HeLa cells, cells were transfected with ON-TARGET plus siRNA pool (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) and incubated for 72 h before harvesting for western blot and image analysis. The MST4 siRNA sequences are: GAUCCAUCAUUUCGUCCUA; UCUUCGAGCUGGUCCAUUU; GAGAAUAACGCUAGCAGGA; UGACUGAACUGAUAGAUCG.

GFP-tagging endogenous CLIC4

The Horizon Discovery Edit-R system was used to insert GFP into the endogenous CLIC4 locus. Briefly, 5′ and 3′ homology arms were PCR amplified and a homology-directed repair template with GFP was created using Gibson Assembly. GFP was inserted into the endogenous locus immediately downstream of the ATG start site. The primers used to amplify the 5′ arm were 5′-CAGCTACTTGGGAGGCTGAGGCAGGAGAATGGCGTGAACCCGGGGCAGAG-3′ and 5′-GGGACCGCGAGGCGAGCGCTCACCTTGACGAAGAGCTCGATGAGGGGCTC-3′. The primers used to amplify the 3′ arm were 5′-GGACGAGCTGTACAAGGGAGGTAGCGCGTTGTCGATGCCGCT-3′ and 5′-ATAACGGAGACCGGCACACTGCCATAGTTTTGAGGGAAGGAGCTGGA-3′.

HeLa cells expressing Cas9 under a doxycycline-inducible promoter were transfected with the homology-directed repair (HDR) plasmid and with gRNA CAAGUUCUGCACAGGUCUGCGUUUUAGAGCUAUGCUGUUUUG, flow sorted, and CLIC4 was sequenced and probed for via western blot. To confirm the insertion of the GFP tag at the N-terminus of the endogenous CLC4 allele, all HeLa lines were genotyped by sequencing.

Plasmids and antibodies

The following antibodies and reagents were used for immunofluorescence: anti-acetylated tubulin (T7451; Sigma; 1:200), Hoechst 33342, SiR-actin (Cytoskeleton, Inc., Denver, CO; 1:10,000), anti-phospho-ERM (CST 3726; 1:100), anti-MST4 (10847; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL; 1:100), anti-NMMIIA (75590; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1:500), anti-NMMIIB (CST 3404; 1:100), anti-anillin (MABT96; EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA; 1:100) and anti-RhoA (sc-418; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; 1:100). Alexa Fluor 594- and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA; 1:200). Alexa Fluor 568–phalloidin was purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA; 1:200). The following antibodies were used for western blotting: anti-CLIC4 (sc-135739; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1000), anti-α-tubulin (sc-23948; 1:2000) and anti-MST4 (10847; Proteintech; 1:1000). The IRDye 680RD donkey anti-mouse and IRDye 800CW donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibodies used for western blotting were purchased from Li-COR (Lincoln, NE; 1:5000). Uncropped images of western blots presented in the main text and supplementary information are shown in Fig. S5. The following plasmids were used: pCAG:IRES-CLIC4 (a gift from the Sung Laboratory, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY), pEGFP-N3:CLIC4, RhoA FRET biosensor (a gift from Gary Bokoch, Scripps Research Institute, San Diego, CA), pGEX:CLIC4, pCMV-SNAP-CRY2-VHH(GFP) (58370; Addgene, Watertown, MA), Tom20-CIB-stop (117243; Addgene), Cry2PHR-mCH-RhoA (42959; Addgene) and pGEX6P1-GFP-Nanobody (61838; Addgene). Site-directed mutagenesis was used to create pEGFP-N3:CLIC4C35A.

Microscopy

Routine imaging was performed on an inverted Axiovert 200M microscope (Zeiss) with a 63× oil immersion lens and QE charge-coupled device camera (Sensicam). Z-stack images were taken at a step size of 500–1000 nm. Image processing was performed using three-dimensional (3D) rendering and exploration software Slidebook 5.0 (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO) or in ImageJ. Images were not deconvolved unless otherwise stated in the figure legend. Time-lapse imaging was performed using a Nikon A1R, equipped with a humidified chamber and temperature-controlled stage. All time lapses were taken at 5 min intervals with 10–15 z-stacks. Time-lapse imaging sessions lasted for approximately 18 h. Time between images is displayed in the figures of each experiment.

Optogenetics for Mitotrap and FRET analysis

For the RhoA activation and GFP–CLIC4 recruitment assay, cells expressing GFP-tagged endogenous CLIC4 were transfected with Cry2PHR-mCH-RhoA (42959; Addgene). Cells were kept in the dark and incubated for 24 h. To induce clustering and activation of RhoA, cells were exposed to 488 nm light for 5 s with the laser power varied between 1 and 10%.

For the Mitotrap experiments, cells expressing endogenous GFP–CLIC4 were transfected with Cry2-VHH (58370; Addgene) and Tom20-CIB-stop (117243; Addgene). Cells were kept in the dark and incubated for 24–48 h. To induce mitochondrial anchoring of GFP–CLIC4, cells were exposed to 488 nm light for 5 s with the laser power varied between 1 and 10%. For fixation, cells were fixed ∼20 min following 488 nm light pulse. For the Mitotrap time-lapse assays, mitochondrial anchoring was ensured for the entirety of the experiment as cells were pulsed and imaged every 5 min. Cells expressing only one of the Mitotrap constructs (Tom20-CIB-stop) were used as controls. All cells (control and Mitotrap) were exposed to 488 nm light pulse to control for phototoxicity.

Identification of CLIC4-interacting proteins

To identify CLIC4-interacting proteins, cells expressing GFP alone or pLVX:GFP-CLIC4 were lysed and proteins were immunoprecipitated using a GST-tagged GFP-nanobody (61838; Addgene) that was covalently linked to Affigel 10/15 resin (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). First, lysates were precleared with GST linked to Affigel, then incubated with GFP-nanobody-containing Affigel. Affigel beads were then washed and resuspended in 500 µl of 50 mM ABC to remove residual DTT and IAA. After centrifugation and supernatant removal, ProteaseMAX (0.02%) and mass spectrometry (MS) grade trypsin was added (1:50) to the particle pellet. The beads were then washed twice in 100 µl of 80% acetonitrile with 1% formic acid and the supernatants were pooled and analysed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Scaffold (version 4.8; Proteome Software, Portland, OR) was used to validate MS/MS based peptide and protein identifications. Peptide identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 95.0% probability as specified by the Peptide Prophet algorithm. Protein identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 99.0% probability and contained at least two identified unique peptides. The criteria to determine CLIC4-interacting proteins were to use a 1.5-fold enrichment cut-off of spectral counts in GFP–CLIC4 over empty GFP (Table S1).

For GST pulldown assays, GST–CLIC4 was purified from BL21-Codon PLUS E. coli as previously described (Mangan et al., 2016). HeLa cells were lysed in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, protease and phosphatase inhibitors and 0.1% Triton X-100. HeLa cell lysate (1 mg) was mixed with 10 µg of either GST or GST–CLIC4 and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Glutathione beads were added and incubated for an additional 60 min. Beads were washed, protein was eluted with 1% SDS and separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by western blot analysis.

Image quantification and statistical analysis

Unless described otherwise, statistics were performed using a Student's t-test. For multi-nucleation assays, at least five random fields were selected and imaged. For measurements containing cells in anaphase, at least 15–30 cells were randomly chosen and imaged. For measuring cell division times, metaphase onset was determined as cell rounding and conclusion of telophase/division was determined as cell flattening and no apparent intercellular bridge. Fluorescent intensities were measured using 3i software or ImageJ and displayed either as raw fluorescence or as fluorescence ratio (poles versus furrow). In all cases, data were collected from at least three independent experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ching-Hwa Sung for providing pCAG:IRES-CLIC4.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: E.P., R.P.; Methodology: E.P.; Validation: E.P.; Formal analysis: E.P.; Investigation: E.P.; Resources: E.P., M.V., R.P.; Data curation: E.P., M.V.; Writing - original draft: E.P., R.P.; Writing - review & editing: E.P., R.P.; Visualization: E.P.; Supervision: E.P.; Project administration: E.P., R.P.; Funding acquisition: E.P., R.P.

Funding

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health (R01 DK064380) to R.P. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.241117.supplemental

Peer review history

The peer review history is available online at https://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.241117.reviewer-comments.pdf

References

- Amini R., Goupil E., Labella S., Zetka M., Maddox A. S., Labbé J. C. and Chartier N. T. (2014). C. elegans anillin proteins regulate intercellular bridge stability and germline syncytial organization. J. Cell Biol. 206, 129-143. 10.1083/jcb.201310117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argenzio E., Klarenbeek J., Kedziora K. M., Nahidiazar L., Isogai T., Perrakis A., Jalink K., Moolenaar W. H. and Innocenti M. (2018). Profilin binding couples chloride intracellular channel protein CLIC4 to RhoA–mDia2 signaling and filopodium formation. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 19161-19176. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argenzio E., Margadant C., Leyton-Puig D., Janssen H., Jalink K., Sonnenberg A. and Moolenaar W. H. (2014). CLIC4 regulates cell adhesion and 1 integrin trafficking. J. Cell Sci. 127, 5189-5203. 10.1242/jcs.150623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berryman M. A. and Goldenring J. R. (2003). CLIC4 is enriched at cell–cell junctions and colocalizes with AKAP350 at the centrosome and midbody of cultured mammalian cells. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 56, 159-172. 10.1002/cm.10141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugaj L. J., Choksi A. T., Mesuda C. K., Kane R. S. and Schaffer D. V. (2013). Optogenetic protein clustering and signaling activation in mammalian cells. Nat. Methods 10, 249-252. 10.1038/nmeth.2360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capalbo L., Bassi Z. I., Geymonat M., Todesca S., Copoiu L., Enright A. J., Callaini G., Riparbelli M. G., Yu L., Choudhary J. S. et al. (2019). The midbody interactome reveals unexpected roles for PP1 phosphatases in cytokinesis. Nat. Commun. 10, 4513 10.1038/s41467-019-12507-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreno S., Kouranti I., Glusman E. S., Fuller M. T., Echard A. and Payre F. (2008). Moesin and its activating kinase Slik are required for cortical stability and microtubule organization in mitotic cells. J. Cell Biol. 180, 739-746. 10.1083/jcb.200709161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattin C. J., Düggelin M., Martinez-Martin D., Gerber C., Müller D. J. and Stewart M. P. (2015). Mechanical control of mitotic progression in single animal cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 11258-11263. 10.1073/pnas.1502029112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charras G. T. (2008). A short history of blebbing. J. Microsc. 231, 466-478. 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2008.02059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charras G. T., Hu C. K., Coughlin M. and Mitchison T. J. (2006). Reassembly of contractile actin cortex in cell blebs. J. Cell Biol. 175, 477-490. 10.1083/jcb.200602085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou S. Y., Hsu K. S., Otsu W., Hsu Y. C., Luo Y. C., Yeh C., Shehab S. S., Chen J., Shieh V., He G. A. et al. (2016). CLIC4 regulates apical exocytosis and renal tube luminogenesis through retromer- and actin-mediated endocytic trafficking. Nat. Commun. 7, 10412 10.1038/ncomms10412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambournet D., Machicoane M., Chesneau L., Sachse M., Rocancourt M., El Marjou A., Formstecher E., Salomon R., Goud B. and Echard A. (2011). Rab35 GTPase and OCRL phosphatase remodel lipids and F-actin for successful cytokinesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 981-988. 10.1038/ncb2279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehon R. G., McClatchey A. I. and Bretscher A. (2010). Organizing the cell cortex: the role of ERM proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 276-287. 10.1038/nrm2866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara K. and Pollard T. D. (1976). Fluorescent antibody localization of myosin in the cytoplasm, cleavage furrow, and mitotic spindle of human cells. J. Cell Biol. 71, 848-875. 10.1083/jcb.71.3.848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund K., Nezis I. P., Lemus D., Grabbe C., Wesche J., Liestøl K., Dikic I., Palmer R. and Stenmark H. (2010). Cindr interacts with anillin to control cytokinesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 20, 944-950. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund K., Nezis I. P. and Stenmark H. (2011). Structure and functions of stable intercellular bridges formed by incomplete cytokinesis during development. Commun. Integr. Biol. 4, 1-9. 10.4161/cib.13550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickson G. R. X., Echard A. and O'Farrell P. H. (2006). Rho-kinase controls cell shape changes during cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 16, 359-370. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiruma S., Kamasaki T., Otomo K., Nemoto T. and Uehara R. (2017). Dynamics and function of ERM proteins during cytokinesis in human cells. FEBS Lett. 591, 3296-3309. 10.1002/1873-3468.12844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao M., Wu D. and Wei Q. (2018). Myosin II-interacting guanine nucleotide exchange factor promotes bleb retraction via stimulating cortex reassembly at the bleb membrane. Mol. Biol. Cell 29, 643-656. 10.1091/mbc.E17-10-0579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouranti I., Sachse M., Arouche N., Goud B. and Echard A. (2006). Rab35 regulates an endocytic recycling pathway essential for the terminal steps of cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 16, 1719-1725. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunda P., Pelling A. E., Liu T. and Baum B. (2008). Article moesin controls cortical rigidity, cell rounding, and spindle morphogenesis during mitosis. Curr. Biol. 18, 91-101. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster O. M. and Baum B. (2014). Shaping up to divide: coordinating actin and microtubule cytoskeletal remodelling during mitosis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 34, 109-115. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabuchi I. and Okuno M. (1977). The effect of myosin antibody on the division of starfish blastomeres. J. Cell Biol. 74, 251-263. 10.1083/jcb.74.1.251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan A. J., Sietsema D. V., Li D., Moore J. K., Citi S. and Prekeris R. (2016). Cingulin and actin mediate midbody-dependent apical lumen formation during polarization of epithelial cells. Nat. Commun. 7, 12426 10.1038/ncomms12426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison T. J., Charras G. T. and Mahadevan L. (2008). Implications of a poroelastic cytoplasm for the dynamics of animal cell shape. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 215-223. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paluch E., Piel M., Prost J., Bornens M. and Sykes C. (2005). Cortical actomyosin breakage triggers shape oscillations in cells and cell fragments. Biophys. J. 89, 724-733. 10.1529/biophysj.105.060590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertz O., Hodgson L., Klemke R. L. and Hahn K. M. (2006). Spatiotemporal dynamics of RhoA activity in migrating cells. Nature 440, 1069-1072. 10.1038/nature04665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterman E., Gibieža P., Schafer J., Skeberdis V. A., Kaupinis A., Valius M., Heiligenstein X., Hurbain I., Raposo G. and Prekeris R. (2019). The post-abscission midbody is an intracellular signaling organelle that regulates cell proliferation. Nat. Commun. 10, 3181 10.1038/s41467-019-10871-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piekny A. J. and Glotzer M. (2008). Anillin is a scaffold protein that links RhoA, actin, and myosin during cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 18, 30-36. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehain-Bell K., Love A., Werner M. E., Macleod I., Yates J. R. and Maddox A. S. (2017). A sterile 20 family kinase and its co-factor CCM-3 regulate contractile ring proteins on germline intercellular bridges. Curr. Biol. 27, 860-867. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehain-Bell K., Werner M., Doshi A., Cortes D., Sattler A., Vuong-Brender T., Labouesse M. and Maddox A. (2019). Novel cytokinetic ring components limit RhoA activity and contractility. BioRxiv. 10.1101/633743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues N. T. L., Lekomtsev S., Jananji S., Kriston-Vizi J., Hickson G. R. X. and Baum B. (2015). Kinetochore-localized PP1-Sds22 couples chromosome segregation to polar relaxation. Nature 524, 489-492. 10.1038/nature14496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlfs M., Arasada R., Batsios P., Janzen J. and Schleicher M. (2007). The Ste20-like kinase SvkA of Dictyostelium discoideum is essential for late stages of cytokinesis. J. Cell Sci. 120, 4345-4354. 10.1242/jcs.012179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roubinet C., Decelle B., Chicanne G., Dorn J. F., Payrastre B., Payre F. and Carreno S. (2011). Molecular networks linked by moesin drive remodeling of the cell cortex during mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 195, 99-112. 10.1083/jcb.201106048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiel J. A., Simon G. C., Zaharris C., Weisz J., Castle D., Wu C. C. and Prekeris R. (2012). FIP3-endosome-dependent formation of the secondary ingression mediates ESCRT-III recruitment during cytokinesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 1068-1078. 10.1038/ncb2577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedzinski J., Biro M., Oswald A., Tinevez J. Y., Salbreux G. and Paluch E. (2011). Polar actomyosin contractility destabilizes the position of the cytokinetic furrow. Nature 476, 462-466. 10.1038/nature10286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skop A. R., Liu H., Yates J., Meyer B. J. and Heald R. (2004). Dissection of the mammalian midbody proteome reveals conserved cytokinesis mechanisms. Science 305, 61-66. 10.1126/science.1097931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight A. F., Field C. M. and Mitchison T. J. (2005). Anillin binds nonmuscle myosin II and regulates the contractile ring. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 193-201. 10.1091/mbc.e04-08-0758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suginta W., Karoulias N., Aitken A. and Ashley R. H. (2001). Chloride intracellular channel protein CLIC4 (P64H1) binds directly to brain dynamin I in a complex containing actin, tubulin and 14-3-3 isoforms. Biochem. J. 359, 55-64. 10.1042/bj3590055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Guan R., Lee I.-J., Liu Y., Chen M., Wang J., Wu J.-Q. and Chen Z. (2015). Mechanistic insights into the anchorage of the contractile ring by anillin and Mid1. Dev. Cell 33, 413-426. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneja N. and Burnette D. T. (2019). Myosin IIA drives membrane bleb retraction. Mol. Biol. Cell 30, 1051-1059. 10.1091/mbc.E18-11-0752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneja N., Bersi M. R., Baillargeon S. M., Fenix A. M., Cooper J. A., Ohi R., Gama V., Merryman W. D. and Burnette D. T. (2020). Precise Tuning of Cortical Contractility Regulates Cell Shape during Cytokinesis. Cell reports. 31, 107477 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavasoli M., Al-Momany A., Wang X., Li L., Edwards J. C. and Ballermann B. J. (2016). Both CLIC4 and CLIC5A activate ERM proteins in glomerular endothelium. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 311, F945-F957. 10.1152/ajprenal.00353.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ten Klooster J. P., Jansen M., Yuan J., Oorschot V., Begthel H., Di Giacomo V., Colland F., De Koning J., Maurice M. M., Hornbeck P. et al. (2009). Mst4 and ezrin induce brush borders downstream of the Lkb1/Strad/Mo25 polarization complex. Dev. Cell 16, 551-562. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uretmen K., Cansu Z., Saner N., Akdag M., Sanal E., Degirmenci B. S., Mollaoglu G. and Ozlu N. (2020). CLIC4 and CLIC1 bridge plasma membrane and cortical actin network for a successful cytokinesis. Life Sci. Alliance 3, e201900558 10.26508/lsa.201900558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E. and Glotzer M. (2016). Local RhoA activation induces cytokinetic furrows independent of spindle position and cell cycle stage. J. Cell Biol. 213, 641-649. 10.1083/jcb.201603025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Wloka C. and Bi E. (2019). Non-muscle myosin-II is required for the generation of a constriction site for subsequent abscission. iScience 13, 69-81. 10.1016/j.isci.2019.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.