ABSTRACT

The nuclear lamina (NL) is an extensive protein network that underlies the inner nuclear envelope. This network includes LAP2-emerin-MAN1 domain (LEM-D) proteins that associate with the chromatin and DNA-binding protein Barrier-to-autointegration factor (BAF). Here, we investigate the partnership between three NL Drosophila LEM-D proteins and BAF. In most tissues, only Emerin/Otefin is required for NL enrichment of BAF, revealing an unexpected dependence on a single LEM-D protein. Prompted by these observations, we studied BAF contributions in the ovary, a tissue where Emerin/Otefin function is essential. We show that germ cell-specific BAF knockdown causes phenotypes that mirror emerin/otefin mutants. Loss of BAF disrupts NL structure, blocks differentiation and promotes germ cell loss, phenotypes that are partially rescued by inactivation of the ATR and Chk2 kinases. These data suggest that, similar to emerin/otefin mutants, BAF depletion activates the NL checkpoint that causes germ cell loss. Taken together, our findings provide evidence for a prominent NL partnership between the LEM-D protein Emerin/Otefin and BAF, revealing that BAF functions with this partner in the maintenance of an adult stem cell population.

KEY WORDS: Nuclear lamina, LEM-domain proteins, Drosophila oogenesis, Germline stem cells, Barrier-to-autointegration factor, Checkpoint kinase 2, Chk2

Summary: Emerin/Otefin, a Drosophila nuclear lamina LEM-D protein, plays a major role in localizing Barrier-to-autointegration factor to the nuclear lamina, a partnership that contributes to stem cell maintenance.

INTRODUCTION

The nuclear lamina (NL) is an extensive protein network that underlies the inner nuclear membrane. Comprising lamins and hundreds of associated proteins, the NL builds contacts with the genome to regulate transcription, replication and DNA repair (Geyer et al., 2011; Goldman et al., 2002; Gonzalo, 2014). The NL also connects the nucleus with the cytoskeleton, facilitating transduction of regulatory information between cellular compartments (Burke and Stewart, 2014). The composition of the NL is cell-type specific (Wong et al., 2014; de Las Heras et al., 2017), providing a diverse platform for the integration of developmental regulatory signals. Changes in NL structure occur during physiological aging and disease (Zink et al., 2004; Scaffidi and Misteli, 2006), suggesting that maintenance of NL function is crucial for cellular health and longevity.

One prominent family of NL proteins are LEM domain (LEM-D) proteins, named after the founding human members: LAP2, emerin and MAN1 (Brachner and Foisner, 2011; Barton et al., 2015). The defining feature of this conserved family is the LEM domain (LEM-D), an ∼40 amino acid domain that directly interacts with the metazoan chromatin-binding protein Barrier-to-autointegration factor [BAF, sometimes referred to as BANF1 (Lin et al., 2000; Zheng et al., 2000; Cai et al., 2001; Montes de Oca et al., 2005; Pinto et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2003)]. Purified human BAF directly binds double-stranded DNA, the A-type lamin and histones in vitro (Montes de Oca et al., 2005; Zheng et al., 2000; Umland et al., 2000; Samson et al., 2018; Brachner and Foisner, 2011; Lancaster et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2001), suggesting that BAF also promotes chromatin-NL connections using non-LEM-D-dependent mechanisms. In dividing metazoan cells, regulated formation of complexes between LEM-D proteins, BAF and lamin controls mitotic spindle assembly and positioning, as well as the reformation of the nucleus (Margalit et al., 2005; Samwer et al., 2017; Qi et al., 2015; Mehsen et al., 2018). In non-dividing metazoan cells, LEM-D proteins and BAF cooperate to tether the genome to the nuclear periphery and form repressed chromatin (González-Aguilera et al., 2014; Jamin and Wiebe, 2015). These properties highlight central connections between LEM-D proteins and BAF in NL function.

Studies in Drosophila melanogaster have begun to define the role of LEM-D proteins and BAF in development. Drosophila has three NL LEM-D proteins that bind BAF (Pinto et al., 2008), including two emerin orthologues (Emerin/Otefin and Emerin2/Bocksbeutel) and MAN1. Each LEM-D protein is globally expressed during development (Wagner et al., 2006; Wagner et al., 2004; Pinto et al., 2008). Even so, loss of individual NL LEM-D proteins causes different, non-overlapping defects in the several tissues, including the ovaries, testes, wings and the nervous system (Pinto et al., 2008; Barton et al., 2013, 2014; Wagner et al., 2010; Laugks et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2008). These restricted mutant phenotypes reflect functional redundancy among the Drosophila LEM-D proteins, as loss of any two proteins is lethal (Barton et al., 2014). Strikingly, phenotypes of the emerin double mutants (otefin−/−; bocksbeutel−/−) phenocopy baf null mutants (Furukawa et al., 2003). Both baf and the emerin double mutants die before pupation, resulting from decreased mitosis and increased apoptosis of imaginal discs (Barton et al., 2014; Furukawa et al., 2003). In contrast, emerin/otefin; MAN1 or emerin2/bocksbeutel; MAN1 die during pupal development, without associated defects in mitosis or apoptosis (Barton et al., 2014). Together, genetic studies indicate that the Drosophila emerin orthologues and BAF are important partners.

Here, we extend our investigations of the Drosophila NL LEM-D and BAF protein partnership. Using a CRISPR generated gfp-baf allele, we confirm that BAF is a globally expressed nuclear protein that shows strong enrichment at the NL in diploid cells. Strikingly, we uncovered that this NL enrichment largely depends upon one LEM-D protein, Emerin/Otefin. Prompted by these observations, we studied BAF contributions in the ovary, a tissue where Emerin/Otefin function is essential (Barton et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2008). In germline stem cells (GSCs), loss of Emerin/Otefin causes a thickening of the NL and reorganization of heterochromatin. These structural nuclear defects are linked to activation of two kinases of the DNA damage response pathway: Ataxia Telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR) and Checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2). Although oogenesis in emerin/otefin mutants is rescued by loss of these DDR kinases, canonical triggers are not responsible for pathway activation. Instead, ATR and Chk2 activation is linked to defects in NL structure itself (Barton et al., 2018). Given the roles of BAF in mitotic nuclear envelope formation and repair (Halfmann et al., 2019; Samwer et al., 2017; Mehsen et al., 2018), we reasoned that checkpoint activation in emerin/otefin mutants might result from altered BAF function. This prediction was tested using germ cell-specific RNA interference (RNAi) to knockdown BAF. We show that BAF depletion disrupts NL structure, blocks differentiation and promotes GSC loss, mutant phenotypes that mirror Emerin/Otefin loss. Additionally, mutation of atr or chk2 partially restores germ cell differentiation in the baf mutant background, supporting the possibility that BAF depletion activates the NL checkpoint. Taken together, our findings suggest that Emerin/Otefin plays a dominant role in the enrichment of BAF to the NL and provide evidence that BAF functions with this prominent partner in the maintenance of an adult stem cell population.

RESULTS

NL enrichment of BAF depends upon Emerin/Otefin

The subcellular localization of BAF varies in different cell types and depends upon the stage of the cell cycle (Jamin and Wiebe, 2015). In human cells, BAF is largely nuclear (Haraguchi et al., 2007), with its localization influenced by binding partners such as LEM-D proteins and lamin (Jamin and Wiebe, 2015). We were interested in understanding how Drosophila LEM-D proteins contribute to the subcellular distribution of BAF. In Drosophila, BAF directly binds three NL LEM-D proteins, Emerin/Otefin, Emerin2/Bocksbeutel and MAN1 (Pinto et al., 2008), but lacks binding to lamins (Schulze et al., 2009). As such, Drosophila provides an opportunity to assess the importance of LEM-D interactions with BAF. Unfortunately, immunohistochemical analyses of BAF have been hampered by the poor performance of extant BAF antibodies (Furukawa et al., 2003). For this reason, we used CRISPR to generate a gfp-baf allele (Fig. 1A, Fig. S1A,B). This allele encodes a N-terminal tagged protein, designed based on previous studies (Margalit et al., 2007; Shimi et al., 2004). Western analysis demonstrated that gfp-baf produces a single polypeptide of the expected size (Fig. S1C). Furthermore, genetic analyses revealed that gfp-baf complements the lethality associated with mutant baf alleles (Fig. 1B). Resulting gfp-baf females and males are fertile, and a homozygous gfp-baf stock can be maintained. Together, these findings suggest that GFP-BAF is a faithful reporter of BAF.

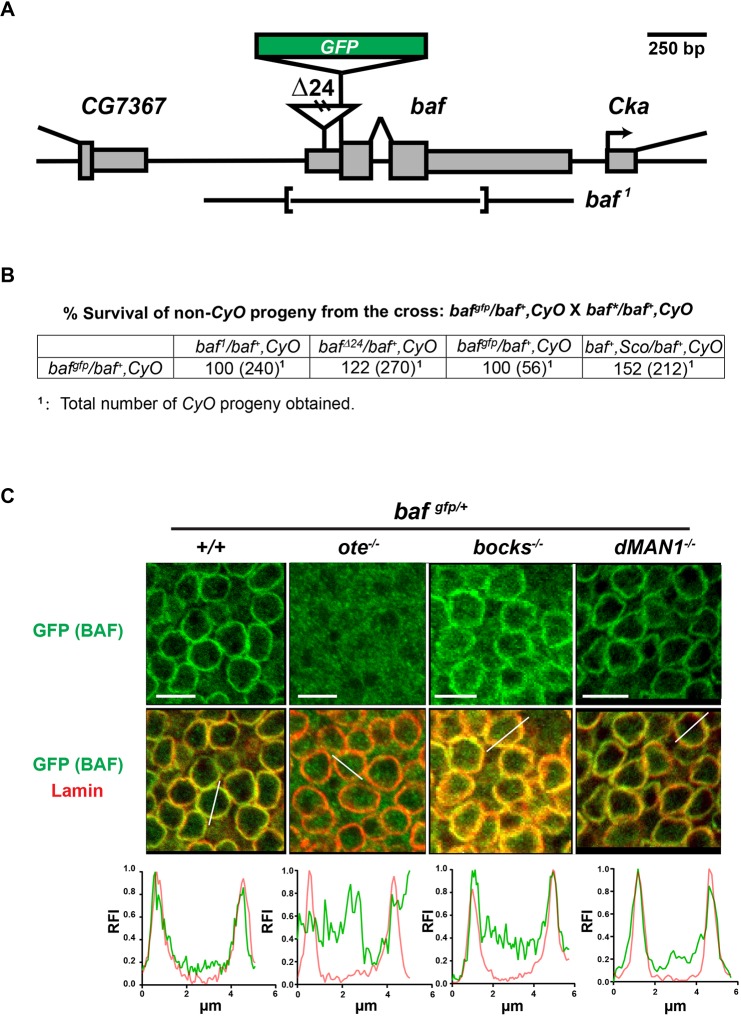

Fig. 1.

NL localization of BAF in somatic diploid cells depends on Emerin/Otefin. (A) A diagram of the baf locus, including baf and the 5′ CG7367 and 3′ Cka genes. The 5′ and 3′ UTR of genes are shown as narrow rectangles and coding regions are shown as wide rectangles. Lesions associated with mutant alleles are depicted, including the insertion in bafΔ24 and the deletion in baf1. The position of the inserted GFP-coding region is shown as a green rectangle. (B) Data obtained from complementation analysis of bafgfp, bafΔ24 and baf1 alleles. (C) Confocal images of fields of nuclei in third instar wing discs of the indicated genotype. Discs were stained using antibodies against GFP (green) and B-type lamin (Lamin; red). Genotypes are indicated at the top of each image, wherein the emerin/otefin mutant background (ote−/−) corresponds to oteB279G/PK, emerin2/bocksbeutel mutant background (bocks−/−) corresponds to bockΔ10/Δ10 and MAN1−/− corresponds to MAN1Δ81/Δ81. Below each image is a representative line scan of the relative fluorescent intensity (RFI) of GFP (green) and Lamin (red) across the selected nucleus. At least five nuclei were analyzed for each genotype, with similar results obtained. x-axis, distance; y-axis, RFI. Scale bars: 5 μm.

The spatial localization of GFP-BAF was first examined in larval imaginal discs. The NL of these cells contains lamins of the A-type (Lamin C, Fig. S2A) and B-type (Lamin/Lamin Dm0, Fig. 1C), as well as all three NL LEM-D proteins (Wagner et al., 2006; Pinto et al., 2008). Staining for GFP-BAF revealed a consistent nuclear phenotype within a field of imaginal disc cells, wherein GFP-BAF is enriched at the nuclear periphery and shows a strong overlap with lamins (Fig. 1C, Fig. S2A). Although BAF levels are unchanged in emerin/otefin mutants (Fig. S1C), its cellular distribution is greatly affected, localizing throughout the nucleus and cytoplasm in the absence of Emerin/Otefin (Fig. 1C). Surprisingly, null mutant backgrounds for the other NL LEM-D proteins had minimal or no effect on NL enrichment of BAF (Fig. 1C). Based on these data, we conclude that Emerin/Otefin is the primary NL partner of BAF in these nuclei. Next, we examined BAF distribution in the polyploid salivary gland, a tissue that contains a similar NL composition to imaginal discs. In salivary gland nuclei, BAF localizes throughout the nucleoplasm and at the NL (Fig. S2B), a distribution that mirrors that of Emerin/Otefin (Fig. S3). This distribution depends upon both Drosophila Emerin orthologues (Fig. S2B), as loss of Emerin/Otefin diminishes nucleoplasmic GFP-BAF and Emerin2/Bocksbeutel diminishes NL GFP-BAF. Taken together, our data suggest that Emerin/Otefin has a major role in NL localization of BAF in diploid cells.

Loss of Emerin/Otefin increases cell death in larval tissues

BAF is an apoptotic mediator (Furukawa et al., 2007). Yet loss of Emerin/Otefin has no effect on organism viability (Barton et al., 2014), indicating that loss of BAF within the NL might not be sufficient for induction of apoptosis. To test this possibility, we stained wild-type, emerin/otefin mutant and baf mutant imaginal discs with antibodies against a marker of apoptosis, the Drosophila effector cleaved Death Caspase 1 (DCP-1; Fig. 2A). We chose baf1/bafΔ24 animals for these studies, because bafΔ24 is a hypomorphic allele that allows enough BAF function to recover larvae with imaginal discs, but not viable adults. We found that emerin/otefin and baf1/bafΔ24 mutant discs showed DCP-1 staining, with higher levels of staining in baf1/bafΔ24 mutant discs (Fig. 2A). Based on these data, we suggest that delocalization of NL BAF might partially compromise BAF function, leading to increased apoptosis. Even so, increased cell death does not change adult structures. For example, although emerin/otefin mutant wing imaginal discs display approximately twice the level of apoptotic staining, the size of the adult wing is unchanged (Fig. 2B). We predict that loss of NL BAF sensitizes imaginal disc cells to apoptosis, but surviving cells might compensate for this loss to retain the normal size and structure of adult tissues, as occurs following induction of developmental stress (Martin et al., 2009; Perez-Garijo et al., 2004).

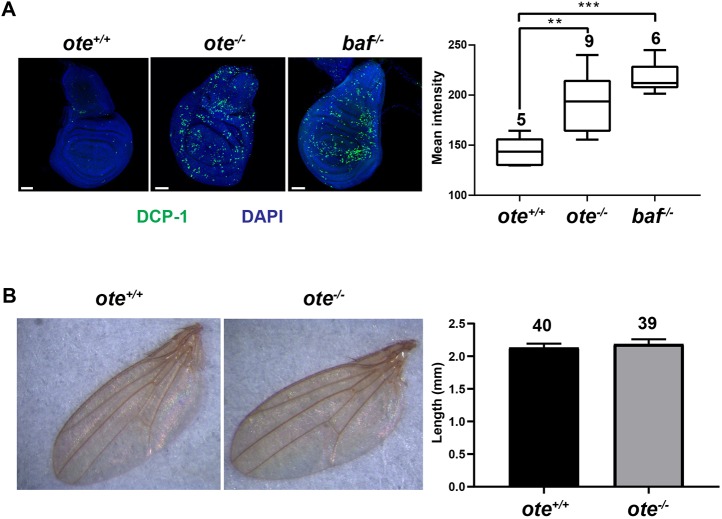

Fig. 2.

Loss of Emerin/Otefin increases apoptosis in developing tissues. (A) Left: confocal images of wing discs dissected from wild-type (ote+/+), emerin/otefin (ote−/−; oteB279G/PK) and baf (baf1/bafΔ24) mutant third instar larvae stained with DAPI (blue) and using the antibody against cleaved Death Caspase 1 (DCP-1; green). Scale bars: 50 μm. Right: box plots of the quantification of DCP-1 intensity of third instar larval wing discs of the indicated genotypes. For each box plot, the box represents the 25th to 75th percentile interval, the line represents the median, and the whiskers represent the 5th to 95th percentile interval and non-outlier range. The number of wing discs analyzed is noted above each top whisker. Student's t-test: **P<0.01, ***P<0.0001. (B) Left: representative wings dissected from wild-type (ote+/+) and emerin/otefin mutant (ote−/−; oteB279G/PK) females. No baf1/bafΔ24 animals survive to adulthood. Right: bar graph shows the quantification of wing length in the same backgrounds. Each bar represents mean length, with the whisker representing the s.d. of the population. The number of wings analyzed is indicated at the top.

BAF is required for the germline function of Emerin/Otefin

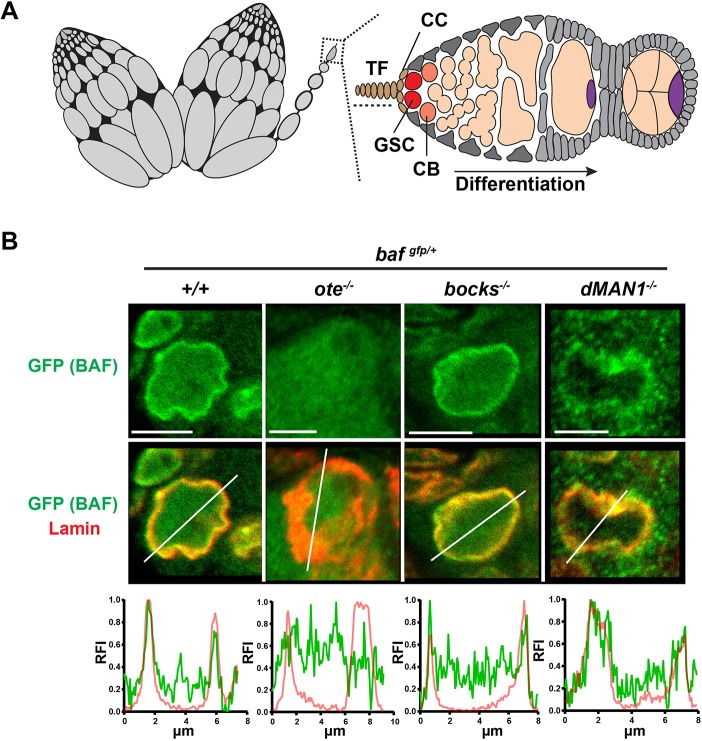

The partnership between Emerin/Otefin and BAF in larval tissues led to the prediction that the function of Emerin/Otefin in the ovary might involve BAF. Drosophila ovaries are divided into 16-20 structures called ovarioles that each carry an assembly line of advancing stages of oocyte maturation (Fig. 3A). At the anterior end of each ovariole is the germarium, a specialized structure that contains the stem cell niche that supports two or three GSCs. Asymmetric GSC divisions produce one germ cell that self-renews and one cystoblast (CB) that commits to differentiation. Four incomplete mitotic divisions of CBs generate an interconnected 16-cell cyst that differentiates into one oocyte and 15 supporting nurse cells (Fig. 3A). To examine BAF function in the ovary, we first defined BAF localization in GSCs, using the stereotypical structure of the niche to identify these stem cells. Once again, we found that BAF is enriched at the NL (Fig. 3B). Second, we examined the distribution of BAF in GSC nuclei found in ovaries dissected from the three lem-d null backgrounds. Mutant ovaries were co-stained using antibodies against Lamin and GFP to recognize BAF, demonstrating that the highly distorted NL in emerin/otefin mutant nuclei fails to localize BAF (Fig. 3B). Parallel analysis of emerin2/bocksbeutel mutant nuclei showed an unchanged nuclear profile, whereas analysis of MAN1 mutant nuclei showed nuclear shape changes and spotty NL accumulation of BAF (Fig. 3B). These observations suggest that MAN1 makes minor contributions to NL structure in GSCs, whereas Emerin/Otefin has a central role. Furthermore, these data provide evidence of a widespread partnership between Emerin/Otefin and BAF during development.

Fig. 3.

NL localization of BAF in germ cells depends on Emerin/Otefin. (A) A schematic representation of an ovary pair (left) and a germarium (right). Each ovary is divided into 16-20 ovarioles that carry advancing stages of oocyte maturation. At the anterior tip of each ovariole (box) is a germarium that contains the ovarian stem cell niche. Somatic cells of the niche include terminal filament and cap cells (brown, TF, CC). Other somatic cells in the germarium are shown in gray. Each niche anchors two or three germline stem cells (GSCs, red). Asymmetric GSC divisions produce one self-renewing stem cell that remains at the niche and a second daughter, called a cystoblast (CB, orange), that differentiates, ultimately leading to the formation of a 16-cell cyst, comprising 15 nurse cells and one oocyte (purple). (B) Confocal images of representative GSC nuclei stained using antibodies against GFP (green) and B-type lamin (red). Images of the corresponding germarium are shown in Fig. S4. Genotypes are indicated at the top of each image. Below each nuclear image is a line scan of the relative fluorescent intensity (RFI) of GFP (green) and B-type Lamin (red) across the selected nucleus. At least five nuclei were scanned, with similar results obtained. x-axis, distance; y-axis, RFI. Scale bars: 5 μm.

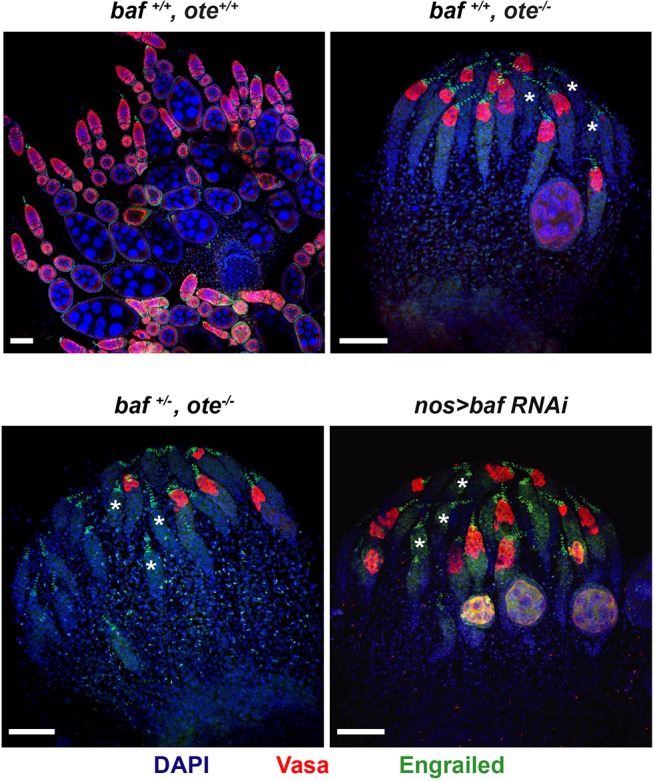

To test the role of the Emerin/Otefin and BAF partnership in the ovary, we used germ cell-specific RNAi knockdown to reduce BAF levels. In these studies, animals carrying a UASp transgene encoding a baf hairpin RNA were crossed with animals carrying the germline specific nanos (nos)-gal4vp16 driver at 25°C. We tested the efficiency of BAF knockdown using gfp-baf animals. In larval germ cells, we found that baf RNAi reduced, but did not eliminate GFP-BAF (Fig. S4A). Notably, this level of BAF depletion did not affect the amplification of primordial germ cells (PGCs), as the number of PGCs in nos>baf RNAi larval ovaries was similar to the wild-type number (Fig. S4B). However, in the adult ovary, GFP-BAF was completely lost (Fig. S4C), allowing investigation of the requirement of BAF in adult GSCs. To this end, we stained ovaries from newly eclosed nos>baf RNAi females using antibodies against the germ cell specific helicase Vasa and Engrailed, a transcription factor that identifies somatic cells of the stem cell niche. As controls, ovaries from wild type and emerin/otefin mutants were stained. These experiments revealed that, similar to loss of Emerin/Otefin, loss of BAF generates a complex phenotype, wherein many germaria lack germ cells, whereas other germaria have germ cells and even maturing stages of oogenesis (Fig. 4). In complementary experiments, we used a gfp hairpin RNA to knockdown BAF in a gfp-baf genetic background (gfp-baf; nos>gfp RNAi; Fig. S4A). In this case, we found strong PGC loss, with remaining PGCs showing a highly distorted NL. We reason that the decreased PGC number might be due to BAF knockdown in earlier stages of ovary development (Fig. S4A). Based on these observed phenotypes, we conclude that BAF partners with Emerin/Otefin to maintain GSCs.

Fig. 4.

Germ cell-specific BAF knockdown compromises oogenesis. Confocal images of ovaries dissected from less than 1-day-old nos>baf RNAi females compared with wild-type and emerin/otefin females with different levels of baf expression. Ovaries were stained for Vasa (red), Engrailed (green) and DAPI (blue). Asterisks mark a subset of germaria without germ cells. Genotypes are indicated at the top of each image. Scale bars: 50 µm.

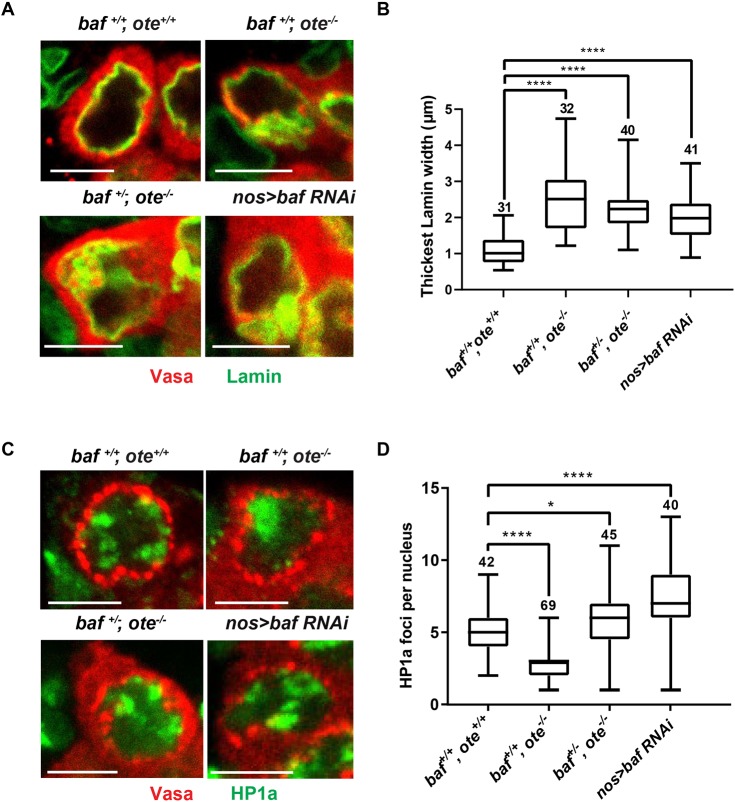

Next, we investigated nuclear phenotypes in baf RNAi GSCs. Ovaries were dissected from newly eclosed nos>baf RNAi females and co-stained with Vasa antibodies to detect germ cells and either antibodies against Lamin to examine NL phenotypes or Heterochromatin Protein 1a (HP1a) to examine the distribution of heterochromatin (Fig. 5A,C; Fig. S5). These analyses revealed that BAF knockdown causes a thickened and irregular NL structure, without heterochromatin aggregation. In comparison, emerin/otefin mutant nuclei display a thickened and irregular NL with heterochromatin aggregation (Fig. 5; Fig. S5). Based on these data, we conclude that BAF knockdown shares some, but not all, defects associated with loss of Emerin/Otefin.

Fig. 5.

BAF contributes to nuclear structure in GSCs. (A,C) Confocal images of individual GSC nuclei found in ovaries dissected from less than one-day-old females that were stained with antibodies against Vasa (red) and (A) the B-type lamin (Lamin, green) or (C) HP1a (green). An image of the corresponding germaria is shown in Fig. S5. GSCs are identified based on Vasa staining and the position in the niche. Vasa is a cytoplasmic protein that displays enriched localization near the nucleus. Scale bars: 5 μm. (B,D) Box plots of the quantification of (B) thickest width of the NL or (D) HP1a foci per GSC nucleus in GSCs of the indicated genotype. For each box plot, the box represents the 25th to 75th percentile interval, the line represents the median, and the whiskers represent the 5th to 95th percentile interval and non-outlier range. The number of nuclei analyzed is indicated above each box. Student's t-test: ns, not significant; *P<0.05, ****P<0.0001.

To gain a better understanding of the differences in heterochromatin distribution between emerin/otefin mutant and baf RNAi ovaries, we studied GSC phenotypes in ovaries dissected from emerin/otefin mutant females with reduced BAF levels (baf+/−, ote−/−). Strikingly, in these ovaries, heterochromatin became dispersed (Fig. 5C,D; Fig. S5), indicating that BAF contributed to the HP1a coalescence in emerin/otefin mutant GSCs. We propose that, in the absence of Emerin/Otefin, untethered BAF increases nucleoplasmic pools, leading to increased chromatin association. We suggest that this loss of NL BAF is similar to the previously reported BAF overexpression phenotype (Montes de Oca et al., 2011).

BAF loss triggers the ATR/Chk2-dependent NL checkpoint

Loss of GSC homeostasis in emerin/otefin mutants results from activation of an ATR- and Chk2-dependent NL checkpoint (Barton et al., 2018). To determine whether BAF loss triggers this checkpoint, we generated atr; nos>bafRNAi and chk2; nos>bafRNAi double mutants. In both double mutant backgrounds, we observed partial rescue of the mutant ovary phenotype (Fig. 6A). The greatest phenotypic improvement was found in the degree of germ cell differentiation (Fig. 6B), wherein 15-21% of the ovarioles contained strings of differentiating egg chambers. In the chk2, but not atr, double mutant background, we also found rescue of germ cell survival (Fig. 6C). However, the degree of rescue in either atr; nos>bafRNAi or chk2; nos>bafRNAi animals was far less than the complete rescue that was observed in chk2−/−, emerin/otefin animals (Barton et al., 2018). Based on these data, we conclude that loss of BAF contributes to the activation of the NL checkpoint and disrupts additional processes required for GSC survival.

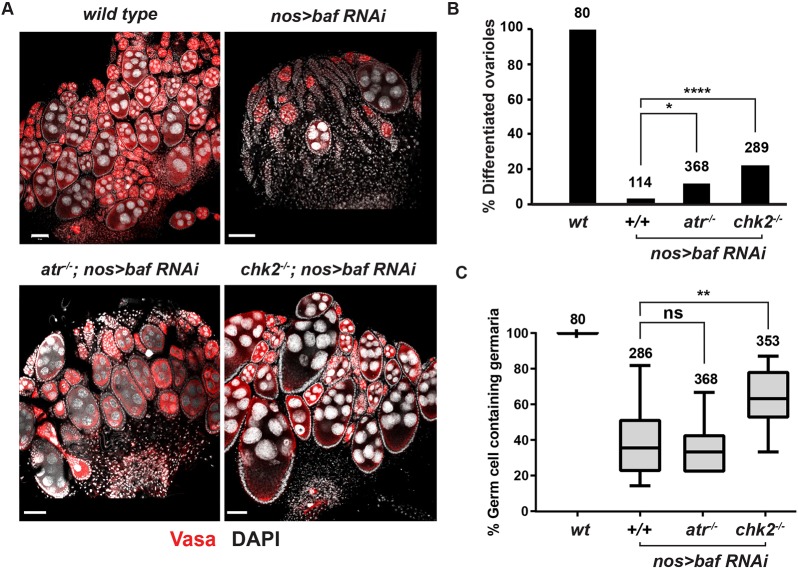

Fig. 6.

The ATR-Chk2-dependent NL checkpoint contributes to germline defects caused by BAF depletion. (A) Confocal images of ovaries dissected from less than 1-day-old females stained for Vasa (red) and DAPI (white). Genotypes are indicated at the top of each image, wherein ATR−/− corresponds to mei-41D9/29D and chk2−/− corresponds to lokp6/p30. Scale bars: 50 μm. (B) Quantification of the percentage of differentiated ovarioles defined as ovarioles that contain at least two egg chambers beyond the germarium. Student's t-test: ****P<0.0001. Genotypes are indicated below the graph and the number of germaria assessed is noted above each bar. (C) Quantification of the percentage of germ cell-containing germaria per ovary in less than one-day-old females. For each box plot, the box represents the 25th to 75th percentile interval, the line represents the median, and the whiskers represent the 5th to 95th percentile interval and non-outlier range. Genotypes are indicated below the graph and the number of germaria assessed is noted above each bar. Student's t-test: ns, not significant; **P<0.01.

BAF knockdown increases germ cell death using multiple pathways

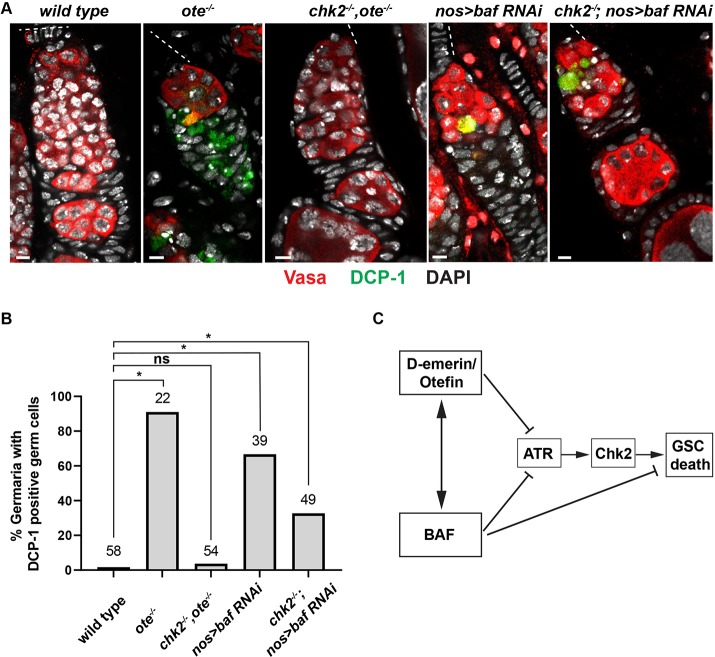

Loss of BAF induces cell type-specific apoptosis (Furukawa et al., 2007). To examine whether BAF knockdown induces germ cell apoptosis, we stained wild type, emerin/otefin mutant and nos>bafRNAi ovaries using antibodies against Vasa and cleaved DCP-1, quantifying the degree of activated caspase staining (Fig. 7A,B). We found significant DCP-1 staining in germ cells of emerin/otefin and nos>bafRNAi mutant germaria, consistent with observations of germ cell death. Strikingly, activated DCP-1 is absent in chk2, emerin/otefin mutant germaria, but remains in chk2, nos>bafRNAi mutant germ cells (Fig. 7A,B). These findings are consistent with the proposal that BAF depletion activates both Chk2-dependent and independent germ cell death pathways (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

BAF depletion causes Chk2-independent germ cell death. (A) Confocal images of representative germaria in ovaries dissected from less than one-day-old females stained for Vasa (red), cleaved Death Caspase 1 (DCP-1; green) and DAPI (white). The location of the GSC niches is shown by a dashed line. Genotypes are indicated at the top. Scale bars: 5 μm. (B) Quantification of the percentage of germaria that carry DCP-1-positive germ cells. Genotypes are listed below the corresponding bar, with the number of germaria scored listed at the top. Student's t-test: ns, not significant; *P<0.05. (C) Model summarizing Emerin/Otefin and BAF contributions to pathways involved in GSC death.

DISCUSSION

The NL establishes direct contacts with the genome to build nuclear architecture. BAF has a central role in this organization, as a DNA-binding protein that interacts with LEM-D proteins, lamins and nucleosomes (Jamin and Wiebe, 2015; Segura-Totten and Wilson, 2004). Metazoan genomes encode multiple LEM-D proteins, which demonstrate unique and shared functions within the NL (Liu et al., 2003; Huber et al., 2009; Barton et al., 2014), emphasizing the functional complexity of the NL.

Enrichment of BAF at the NL depends upon a single LEM-D protein

Here, we extended our in vivo studies of the BAF and LEM-D partnership. Capitalizing on a newly generated gfp-baf allele (Fig. 1), we show that NL localization of BAF largely depends upon a single LEM-D protein, Emerin/Otefin. Loss of Emerin/Otefin is sufficient to disperse BAF in cells that express the A- and B-type lamins, Emerin2/Bocksbeutel and MAN1 in the NL (Figs 1C and 3B, Fig. S2; Pinto et al., 2008; Wagner et al., 2004). These data establish the in vivo existence of a prominent NL partnership between one LEM-D protein and BAF.

The basis for the unexpected reliance on Emerin/Otefin is unknown. One possibility is that LEM-Ds have different affinities for BAF. Pairwise alignment of amino acid residues within LEM-Ds shows the highest conservation between Drosophila emerin orthologues (70% similarity; Barton et al., 2014). Nonetheless, all LEM-Ds are strongly conserved in BAF-binding residues (42% identical, 67% similar). A second possibility is that the interaction of LEM-D proteins with BAF depends upon how a given LEM-D protein assembles into the NL network. Self-association of emerin influences both BAF and lamin binding (Berk et al., 2014; Samson et al., 2017; Herrada et al., 2015). Finally, post-translational modifications (PTMs) of LEM-D proteins might impact BAF partnerships (Barton et al., 2015). As an example, O-GlcNAcylation modification of emerin affects BAF association (Berk et al., 2013), representing a regulated PTM that has the potential to alter NL function in response to nutrient availability (Hart et al., 2011; Bar et al., 2014). However, such signal-dependent PTMs are likely to be tissue specific, predicting a tissue-restricted, not global, effect on the NL enrichment of BAF. Further studies are needed to resolve the basis for the strong partnership between Emerin/Otefin and BAF.

Phenotypes associated with loss of NL BAF differ from those of complete BAF loss

BAF is essential for viability, with dying baf null larvae exhibiting a typical mitotic mutant phenotype that is associated with high levels of apoptosis (Furukawa et al., 2007). Several observations suggest that loss of NL BAF is not equivalent to complete loss of BAF. First, emerin/otefin null animals are viable, even though there is a global loss of NL BAF (Figs 1C and 3B, Fig. S2). Second, emerin/otefin null animals have lower levels of apoptosis in larval tissues than baf animals, without effects on the development of adult structures (Fig. 2A). Third, emerin/otefin mutant imaginal disc cells display an unchanged nuclear shape and chromatin architecture (Fig. 1C, Fig. S2A; Barton et al., 2018), whereas these cells are affected in baf mutants (Furukawa et al., 2003). Based on these data, we suggest that BAF function at the NL during interphase is not essential. We predict that the essential BAF function relates to its contributions in mitosis and depends upon both Drosophila emerin orthologues, as these double mutant animals die with a mitotic mutant phenotype (Barton et al., 2014).

Effects of mislocalized BAF share features resulting from BAF overexpression in other systems. In emerin/otefin mutant germ cells, BAF dispersal contributes to the aggregation of heterochromatin (Fig. 5C,D). Defects in HP1a distribution have also been found in human cells overexpressing BAF or expressing a BAF mutant defective in interacting with NL components (Montes de Oca et al., 2011; Loi et al., 2016). Furthermore, several diseases affecting expression and processing of lamin A alter the distribution of BAF and resemble a BAF overexpression phenotype (Loi et al., 2016). Together, these findings support a model in which BAF contributes to the deleterious effects resulting from lamin or LEM-D mutations.

Survival of adult stem cells depends upon BAF

BAF is required for maintenance of Drosophila GSCs (Figs 4 and 6C). Germ cell-specific BAF knockdown caused GSC loss, with remaining GSCs displaying a thickened and irregular NL structure, a phenotype shared with emerin/otefin mutants (Fig. 5A,B). These data support a model in which Emerin/Otefin and BAF function together to build NL structure in this cell type. Such a dependence on Emerin/Otefin for NL structure is consistent with limiting levels of the second Drosophila Emerin ortholog, Emerin2/Bocksbeutel (Barton et al., 2014). We predict that, in GSCs, the Emerin/Otefin and BAF might have a shared function in nuclear reformation at the end of mitosis.

Activation of the NL checkpoint is linked to NL deformation (Barton et al., 2018). Strikingly, baf mutant phenotypes are partially suppressed in atr/chk2; nos>bafRNAi animals, with double mutant ovaries showing increased germ cell survival and differentiation (Fig. 6). Yet cell death remained in the double mutant backgrounds (Fig. 7). Based on these observations, we predict that BAF loss in germ cells has multiple consequences. First, NL structure is affected (Fig. 5A,B). Second, loss of nuclear BAF might affect transcriptional networks required for GSC maintenance, suggested from studies showing BAF is an epigenetic regulator (Montes de Oca et al., 2011). Notably, the maintenance of mammalian stem cells also depends on BAF. Knockdown of BAF in either mouse or human embryonic stem cells promoted premature differentiation and reduced survival (Cox et al., 2011), phenotypes associated with an altered cell cycle. It remains possible that loss of Drosophila BAF in GSCs perturbs mitosis, which might induce apoptosis. Additional studies are needed to elucidate cell cycle contributions of BAF in GSCs.

Our studies emphasize the important role of BAF within the NL network. We present evidence for consequences of BAF dispersal and loss during development, showing BAF dysfunction causes cell-type specific responses. Further definition of the developmental contributions of BAF will advance our understanding of laminopathies, including the Nestór-Guillermo syndrome: a rare hereditary progeroid disorder caused by a missense mutation in BAF/BANF1 (Puente et al., 2011).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila stocks and culture conditions

Drosophila stocks were raised on standard cornmeal/agar medium with p-hydroxybenzoic acid methyl ester as a mold inhibitor. All crosses, including all RNAi crosses, were carried out at 25°C, 70% humidity. The wild-type reference strain was y1, w67c23. In all cases, emerin/otefin mutant animals were y1, w67c23; oteB279G/PK, wherein both alleles fail to generate protein (Barton et al., 2013). The oteB279G allele carries an insertion of a piggyBac transposon at +764 and otePK carries a premature stop at codon 127 (Barton et al., 2013). The baf1 allele was derived from the lethal strain l(2)k10210 that carries a P-element inserted 350 bp downstream of the baf termination site, wherein P-element excision removed ∼1 kb of the baf gene, while leaving ∼1 kb of the P-element (kindly provided by K. Furukawa; Furukawa et al., 2003; Fig. 1A). The bafΔ24 allele was derived from bafSH1315 (Bloomington, 29496), which carries a P-element inserted 75 bp downstream of the transcription start site, wherein P-element excision removed the white gene but left >700 bp of the starting P element (Fig. 1A). Knockdown of BAF was achieved using y1, sc*, v1, sev21; P{Trip.HMS00195}attP2 (Bloomington 36108) and of GFP-BAF using y1, sc*, v1, sev21; P{Trip.HMS00195}attP2 (Bloomington 41553). The bocksbeutel (bocks) allele was bocksΔ10, which carries a 344 bp deletion within the coding region of bocks (Barton et al., 2014). The MAN1 allele was MAN1Δ81, which carries an ∼2.3 kb deletion of the MAN1 gene that includes the coding region (Pinto et al., 2008). Other alleles are listed in Table S1.

Generation of the gfp-baf allele

The gfp-baf allele was generated using scarless CRISPR cloning as described previously (Bier et al., 2018). The guide RNA expression plasmid targeted position +146 of baf. The template plasmid contained 1 kb homology arms inserted flanking the GFP-coding sequence with a piggyBac transposon that contained a DsRed transgene. The guide and template plasmids were co-injected into y1, w*; nos-Cas9[III-attP40] embryos (Best Gene). DsRed-positive flies were crossed to a piggyBac transposase expressing line (Bloomington stock, 8285) to excise DsRed, resulting in an in-frame fusion of the GFP and baf-coding sequences. The successful generation of bafGFP was confirmed by using multiple PCR primers (Fig. S1B). Additionally, the gfp-baf gene was PCR isolated and sequenced, demonstrating the expected sequence. The encoded protein has the N-terminal GFP separated from BAF by a 14 amino acid linker.

Western analyses

GFP-BAF levels were assessed using proteins extracted from the anterior third of wandering third instar larvae (Fig. S1C). Five larval equivalents were loaded into each well, electrophoresed on a 4-20% gradient Tris gel and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were probed with primary antibodies against GFP (rabbit 1:2000, Life Technologies, A11122) or alpha-Tubulin (mouse 1:20,000, Sigma, T5168). Primary antibodies were detected with fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (donkey anti-mouse 680, 1:20,000, LI-COR, 926-68072; donkey anti-rabbit 800, 1:10,00, LI-COR, 925-32213).

Immunohistochemical analyses

For each experiment, five pairs of ovaries were dissected in ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution and immediately fixed in 4% EM Grade paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences 15710) at room temperature. Ovaries were then washed in PBST and blocked in 5% w/v BSA at room temperature for 1 h. Samples were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) were incubated with ovaries at room temperature for 2 h. Ovaries were washed in PBST, stained with 1 µg/ml DAPI (ThermoFisher Scientific) and mounted in SlowFade (ThermoFisher Scientific). Images were collected with a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope, and processed using ZEN imaging software. Primary antibodies included: goat anti-GFP at 1:2000 (Abcam), mouse anti-Lamin at 1:300 (DSHB ADL84.12), rabbit anti-cleaved DCP-1 at 1:200 (Cell Signaling), mouse anti-HP1a 1:200 (DSHB, C1A9), mouse anti-Engrailed at 1:100 (DSHB,4D9), mouse anti-Spectrin at 1:50 (DSHB, 3A9), rabbit anti-Vasa at 1:300 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and mouse anti-Lamin C at 1:300 (DSHB LC28.26). Experiments were performed using two or three biological replicates involving at least five pairs of ovaries per experiment. Quantification of phenotypes was completed on the indicated number of germaria from at least five different ovaries per replicate. The number of HP1a foci was quantified manually using Zen2 software. Two HP1a signals were considered as separate if they were separated by a black pixel.

Immunofluorescence intensity plots

Fluorescence intensity plots of nuclei were generated using a single slice of a 63× confocal image using ImageJ software. Briefly, the image background was subtracted using ImageJ (50 pixel rolling ball radius), a line segment was drawn across the nucleus and the plot profile function was used to generate a fluorescence intensity plot for each desired channel. The raw data files generated in this manner were analyzed in Excel, with each plot line normalized to the peak value within that plot, generating intensity plots wherein the maximum observed fluorescence of a line is presented by the value 1 relative fluorescence intensity (RFI). Normalized fluorescent values were plotted using Prism software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Rebecca Cupp and Jaya Guha for technical assistance. We thank members of the Geyer laboratory for helpful discussions. We thank K. Furukawa for generously supplying fly stocks. Imaging was supported by the University of Iowa Central Microscopy Research Facility and use of the Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope acquired via National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding (S10 RR025439-01).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: T.D., P.K.G.; Methodology: T.D., S.C.K., P.K.G.; Validation: S.C.K., P.K.G.; Formal analysis: T.D.; Investigation: T.D., S.C.K., P.K.G.; Resources: P.K.G.; Writing - original draft: T.D., P.K.G.; Writing - review & editing: T.D., S.C.K., P.K.G.; Visualization: T.D., P.K.G.; Supervision: T.D., P.K.G.; Project administration: T.D., P.K.G.; Funding acquisition: P.K.G.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health R01 funding (GM087341) to P.K.G. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.186171.supplemental

Peer review history

The peer review history is available online at https://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.186171.reviewer-comments.pdf

References

- Bar D. Z., Davidovich M., Lamm A. T., Zer H., Wilson K. L. and Gruenbaum Y. (2014). BAF-1 mobility is regulated by environmental stresses. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 1127-1136. 10.1091/mbc.e13-08-0477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L. J., Pinto B. S., Wallrath L. L. and Geyer P. K. (2013). The Drosophila nuclear lamina protein otefin is required for germline stem cell survival. Dev. Cell 25, 645-654. 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L. J., Wilmington S. R., Martin M. J., Skopec H. M., Lovander K. E., Pinto B. S. and Geyer P. K. (2014). Unique and shared functions of nuclear lamina LEM domain proteins in Drosophila. Genetics 197, 653-665. 10.1534/genetics.114.162941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L. J., Soshnev A. A. and Geyer P. K. (2015). Networking in the nucleus: a spotlight on LEM-domain proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 34, 1-8. 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L. J., Duan T., Ke W., Luttinger A., Lovander K. E., Soshnev A. A. and Geyer P. K. (2018). Nuclear lamina dysfunction triggers a germline stem cell checkpoint. Nat. Commun. 9, 3960 10.1038/s41467-018-06277-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk J. M., Maitra S., Dawdy A. W., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F. and Wilson K. L. (2013). O-Linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) regulates emerin binding to barrier to autointegration factor (BAF) in a chromatin- and lamin B-enriched “niche”. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 30192-30209. 10.1074/jbc.M113.503060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk J. M., Simon D. N., Jenkins-Houk C. R., Westerbeck J. W., Gronning-Wang L. M., Carlson C. R. and Wilson K. L. (2014). The molecular basis of emerin-emerin and emerin-BAF interactions. J. Cell Sci. 127, 3956-3969. 10.1242/jcs.148247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bier E., Harrison M. M., O'Connor-Giles K. M. and Wildonger J. (2018). Advances in engineering the fly genome with the CRISPR-Cas system. Genetics 208, 1-18. 10.1534/genetics.117.1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachner A. and Foisner R. (2011). Evolvement of LEM proteins as chromatin tethers at the nuclear periphery. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39, 1735-1741. 10.1042/BST20110724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke B. and Stewart C. L. (2014). Functional architecture of the cell's nucleus in development, aging, and disease. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 109, 1-52. 10.1016/B978-0-12-397920-9.00006-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai M., Huang Y., Ghirlando R., Wilson K. L., Craigie R. and Clore G. M. (2001). Solution structure of the constant region of nuclear envelope protein LAP2 reveals two LEM-domain structures: one binds BAF and the other binds DNA. EMBO J. 20, 4399-4407. 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. L., Mallanna S. K., Ormsbee B. D., Desler M., Wiebe M. S. and Rizzino A. (2011). Banf1 is required to maintain the self-renewal of both mouse and human embryonic stem cells. J. Cell Sci. 124, 2654-2665. 10.1242/jcs.083238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de las Heras J. I., Zuleger N., Batrakou D. G., Czapiewski R., Kerr A. R. and Schirmer E. C. (2017). Tissue-specific NETs alter genome organization and regulation even in a heterologous system. Nucleus 8, 81-97. 10.1080/19491034.2016.1261230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K., Sugiyama S., Osouda S., Goto H., Inagaki M., Horigome T., Omata S., Mcconnell M., Fisher P. A. and Nishida Y. (2003). Barrier-to-autointegration factor plays crucial roles in cell cycle progression and nuclear organization in Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 116, 3811-3823. 10.1242/jcs.00682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K., Aida T., Nonaka Y., Osoda S., Juarez C., Horigome T. and Sugiyama S. (2007). BAF as a caspase-dependent mediator of nuclear apoptosis in Drosophila. J. Struct. Biol. 160, 125-134. 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer P. K., Vitalini M. W. and Wallrath L. L. (2011). Nuclear organization: taking a position on gene expression. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 354-359. 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman R. D., Gruenbaum Y., Moir R. D., Shumaker D. K. and Spann T. P. (2002). Nuclear lamins: building blocks of nuclear architecture. Genes Dev. 16, 533-547. 10.1101/gad.960502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Aguilera C., Ikegami K., Ayuso C., de Luis A., Íñiguez M., Cabello J., Lieb J. D. and Askjaer P. (2014). Genome-wide analysis links emerin to neuromuscular junction activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Biol. 15, R21 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalo S. (2014). DNA damage and lamins. Cancer Biology and the Nuclear Envelope: Recent Advances May Elucidate Past Paradoxes 773, 377-399. 10.1007/978-1-4899-8032-8_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfmann C. T., Sears R. M., Katiyar A., Busselman B. W., Aman L. K., Zhang Q., O'Bryan C. S., Angelini T. E., Lele T. P. and Roux K. J. (2019). Repair of nuclear ruptures requires barrier-to-autointegration factor. J. Cell Biol. 218, 2136-2149. 10.1083/jcb.201901116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi T., Koujin T., Osakada H., Kojidani T., Mori C., Masuda H. and Hiraoka Y. (2007). Nuclear localization of barrier-to-autointegration factor is correlated with progression of S phase in human cells. J. Cell Sci. 120, 1967-1977. 10.1242/jcs.03461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart G. W., Slawson C., Ramirez-Correa G. and Lagerlof O. (2011). Cross talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 825-858. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060608-102511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrada I., Samson C., Velours C., Renault L., Östlund C., Chervy P., Puchkov D., Worman H. J., Buendia B. and Zinn-Justin S. (2015). Muscular Dystrophy Mutations Impair the Nuclear Envelope Emerin Self-assembly Properties. ACS Chem. Biol. 10, 2733-2742. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber M. D., Guan T. and Gerace L. (2009). Overlapping functions of nuclear envelope proteins NET25 (Lem2) and emerin in regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in myoblast differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 5718-5728. 10.1128/MCB.00270-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamin A. and Wiebe M. S. (2015). Barrier to Autointegration Factor (BANF1): interwoven roles in nuclear structure, genome integrity, innate immunity, stress responses and progeria. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 34, 61-68. 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Xia L., Chen D., Yang Y., Huang H., Yang L., Zhao Q., Shen L., Wang J. and Chen D. (2008). Otefin, a nuclear membrane protein, determines the fate of germline stem cells in Drosophila via interaction with Smad complexes. Dev. Cell 14, 494-506. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster O. M., Cullen C. F. and Ohkura H. (2007). NHK-1 phosphorylates BAF to allow karyosome formation in the Drosophila oocyte nucleus. J. Cell Biol. 179, 817-824. 10.1083/jcb.200706067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugks U., Hieke M. and Wagner N. (2017). MAN1 restricts BMP signaling during synaptic growth in Drosophila. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 37, 1077-1093. 10.1007/s10571-016-0442-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. K., Haraguchi T., Lee R. S., Koujin T., Hiraoka Y. and Wilson K. L. (2001). Distinct functional domains in emerin bind lamin A and DNA-bridging protein BAF. J. Cell Sci. 114, 4567-4573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F., Blake D. L., Callebaut I., Skerjanc I. S., Holmer L., Mcburney M. W., Paulin-Levasseur M. and Worman H. J. (2000). MAN1, an inner nuclear membrane protein that shares the LEM domain with lamina-associated polypeptide 2 and emerin. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 4840-4847. 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Lee K. K., Segura-Totten M., Neufeld E., Wilson K. L. and Gruenbaum Y. (2003). MAN1 and emerin have overlapping function(s) essential for chromosome segregation and cell division in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 4598-4603. 10.1073/pnas.0730821100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loi M., Cenni V., Duchi S., Squarzoni S., Lopez-Otin C., Foisner R., Lattanzi G. and Capanni C. (2016). Barrier-to-autointegration factor (BAF) involvement in prelamin A-related chromatin organization changes. Oncotarget 7, 15662-15677. 10.18632/oncotarget.6697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margalit A., Segura-Totten M., Gruenbaum Y. and Wilson K. L. (2005). Barrier-to-autointegration factor is required to segregate and enclose chromosomes within the nuclear envelope and assemble the nuclear lamina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 3290-3295. 10.1073/pnas.0408364102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margalit A., Neufeld E., Feinstein N., Wilson K. L., Podbilewicz B. and Gruenbaum Y. (2007). Barrier to autointegration factor blocks premature cell fusion and maintains adult muscle integrity in C. elegans. J. Cell Biol. 178, 661-673. 10.1083/jcb.200704049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin F. A., Perez-Garijo A. and Morata G. (2009). Apoptosis in Drosophila: compensatory proliferation and undead cells. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 53, 1341-1347. 10.1387/ijdb.072447fm [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehsen H., Boudreau V., Garrido D., Bourouh M., Larouche M., Maddox P. S., Swan A. and Archambault V. (2018). PP2A-B55 promotes nuclear envelope reformation after mitosis in Drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 217, 4106-4123. 10.1083/jcb.201804018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes de Oca R., Lee K. K. and Wilson K. L. (2005). Binding of barrier to autointegration factor (BAF) to histone H3 and selected linker histones including H1.1. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42252-42262. 10.1074/jbc.M509917200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes de Oca R., Andreassen P. R. and Wilson K. L. (2011). Barrier-to-Autointegration Factor influences specific histone modifications. Nucleus 2, 580-590. 10.4161/nucl.2.6.17960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Garijo A., Martin F. A. and Morata G. (2004). Caspase inhibition during apoptosis causes abnormal signalling and developmental aberrations in Drosophila. Development 131, 5591-5598. 10.1242/dev.01432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto B. S., Wilmington S. R., Hornick E. E. L., Wallrath L. L. and Geyer P. K. (2008). Tissue-specific defects are caused by loss of the drosophila MAN1 LEM domain protein. Genetics 180, 133-145. 10.1534/genetics.108.091371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puente X. S., Quesada V., Osorio F. G., Cabanillas R., Cadiñanos J., Fraile J. M., Ordóñez G. R., Puente D. A., Gutiérrez-Fernández A., Fanjul-Fernández M. et al. (2011). Exome sequencing and functional analysis identifies BANF1 mutation as the cause of a hereditary progeroid syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 650-656. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi R., Xu N., Wang G., Ren H., Li S., Lei J., Lin Q., Wang L., Gu X., Zhang H. et al. (2015). The lamin-A/C-LAP2alpha-BAF1 protein complex regulates mitotic spindle assembly and positioning. J. Cell Sci. 128, 2830-2841. 10.1242/jcs.164566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson C., Celli F., Hendriks K., Zinke M., Essawy N., Herrada I., Arteni A. A., Theillet F. X., Alpha-Bazin B., Armengaud J. et al. (2017). Emerin self-assembly mechanism: role of the LEM domain. FEBS J. 284, 338-352. 10.1111/febs.13983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson C., Petitalot A., Celli F., Herrada I., Ropars V., Le Du M.-H., Nhiri N., Jacquet E., Arteni A.-A., Buendia B. et al. (2018). Structural analysis of the ternary complex between lamin A/C, BAF and emerin identifies an interface disrupted in autosomal recessive progeroid diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 10460-10473. 10.1093/nar/gky736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samwer M., Schneider M. W. G., Hoefler R., Schmalhorst P. S., Jude J. G., Zuber J. and Gerlich D. W. (2017). DNA cross-bridging shapes a single nucleus from a set of mitotic chromosomes. Cell 170, 956-972.e23. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaffidi P. and Misteli T. (2006). Lamin A-dependent nuclear defects in human aging. Science 312, 1059-1063. 10.1126/science.1127168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze S. R., Curio-Penny B., Speese S., Dialynas G., Cryderman D. E., Mcdonough C. W., Nalbant D., Petersen M., Budnik V., Geyer P. K. et al. (2009). A comparative study of Drosophila and human A-type lamins. PLoS ONE 4, e7564 10.1371/journal.pone.0007564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura-Totten M. and Wilson K. L. (2004). BAF: roles in chromatin, nuclear structure and retrovirus integration. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 261-266. 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimi T., Koujin T., Segura-Totten M., Wilson K. L., Haraguchi T. and Hiraoka Y. (2004). Dynamic interaction between BAF and emerin revealed by Frap, Flip, and FRET analyses in living HeLa cells. J. Struct. Biol. 147, 31-41. 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umland T. C., Wei S.-Q., Craigie R. and Davies D. R. (2000). Structural basis of DNA bridging by barrier-to-autointegration factor. Biochemistry 39, 9130-9138. 10.1021/bi000572w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner N., Schmitt J. and Krohne G. (2004). Two novel LEM-domain proteins are splice products of the annotated Drosophila melanogaster gene CG9424 (Bocksbeutel). Eur. J. Cell Biol. 82, 605-616. 10.1078/0171-9335-00350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner N., Kagermeier B., Loserth S. and Krohne G. (2006). The Drosophila melanogaster LEM-domain protein MAN1. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 85, 91-105. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner N., Weyhersmüller A., Blauth A., Schuhmann T., Heckmann M., Krohne G. and Samakovlis C. (2010). The Drosophila LEM-domain protein MAN1 antagonizes BMP signaling at the neuromuscular junction and the wing crossveins. Dev. Biol. 339, 1-13. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong X. R., Luperchio T. R. and Reddy K. L. (2014). NET gains and losses: the role of changing nuclear envelope proteomes in genome regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 28, 105-120. 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng R., Ghirlando R., Lee M. S., Mizuuchi K., Krause M. and Craigie R. (2000). Barrier-to-autointegration factor (BAF) bridges DNA in a discrete, higher-order nucleoprotein complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 8997-9002. 10.1073/pnas.150240197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink D., Fischer A. H. and Nickerson J. A. (2004). Nuclear structure in cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 677-687. 10.1038/nrc1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.