ABSTRACT

EML4–ALK is an oncogenic fusion present in ∼5% of non-small cell lung cancers. However, alternative breakpoints in the EML4 gene lead to distinct variants of EML4–ALK with different patient outcomes. Here, we show that, in cell models, EML4–ALK variant 3 (V3), which is linked to accelerated metastatic spread, causes microtubule stabilization, formation of extended cytoplasmic protrusions and increased cell migration. EML4–ALK V3 also recruits the NEK9 and NEK7 kinases to microtubules via the N-terminal EML4 microtubule-binding region. Overexpression of wild-type EML4, as well as constitutive activation of NEK9, also perturbs cell morphology and accelerates migration in a microtubule-dependent manner that requires the downstream kinase NEK7 but does not require ALK activity. Strikingly, elevated NEK9 expression is associated with reduced progression-free survival in EML4–ALK patients. Hence, we propose that EML4–ALK V3 promotes microtubule stabilization through NEK9 and NEK7, leading to increased cell migration. This represents a novel actionable pathway that could drive metastatic disease progression in EML4–ALK lung cancer.

KEY WORDS: EML4–ALK, EML4, NEK9, NEK7, NSCLC, Microtubules, Cell migration, Metastasis

Summary: EML4–ALK fusions are major drivers of lung cancer. Particular fusion variants act through a novel actionable pathway involving NEK7 and NEK9, promoting cell migration and potentially influencing metastatic progression.

INTRODUCTION

The EML4–ALK translocation is an oncogenic driver in a subset of lung cancers resulting from an inversion on the short arm of chromosome 2. This inversion creates an in-frame fusion of an N-terminal fragment of the echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4, EML4 (Li and Suprenant, 1994; Suprenant et al., 1993), to the C-terminal tyrosine kinase domain of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase, ALK. The fusion was first identified in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), where it is present in ∼5% of cases, but it has since been identified in other tumour types, including breast and colorectal cancers (Lin et al., 2009; Rikova et al., 2007; Soda et al., 2007). The majority of EML4–ALK lung cancers respond remarkably well to catalytic inhibitors of the ALK tyrosine kinase, such as crizotinib. However, this approach is not curative as acquired resistance to ALK inhibitors, due to either secondary mutations in the ALK tyrosine kinase domain or off-target alterations that switch dependence to other signalling pathways, is inevitable (Choi et al., 2010; Crystal et al., 2014; Hrustanovic et al., 2015; Kwak et al., 2010; McCoach et al., 2018; Shaw et al., 2013). Consequently, alternative therapies capable of selectively targeting ALK inhibitor resistant lung cancers are warranted.

It is clear that not all EML4–ALK patients respond well to ALK inhibitors (Woo et al., 2017). One potential explanation for this is the presence of alternative EML4–ALK variants that arise from distinct breakpoints (Bayliss et al., 2016; Choi et al., 2008). All known fusions encode the C-terminal catalytic domain of the ALK kinase and an N-terminal coiled-coil from EML4 that promotes oligomerization and autophosphorylation. However, alternative breakpoints in the EML4 gene lead to different EML4 sequences being present in the different fusion variants. The N-terminal coiled-coil of EML4 (residues 14–63) has been shown by X-ray crystallography to form trimers (Richards et al., 2015). This sequence is followed by an unstructured region of ∼150 residues, which is rich in serine, threonine and basic residues. Based on crystallographic analysis of the related EML1 protein, the ∼600 residue C-terminal region of EML4 (residues 216–865) is predicted to fold into a tandem pair of atypical β-propellers, termed the TAPE domain (Richards et al., 2014). Structure-function studies have shown that, although the C-terminal TAPE domain binds to α/β-tubulin heterodimers, it is the N-terminal domain (NTD) encompassing the coiled-coil and unstructured region that promotes binding to polymerized microtubules (Richards et al., 2014, 2015).

Although all EML4–ALK fusion proteins have the trimerization motif, the distinct breakpoints in EML4 mean that the different variants encode the unstructured and TAPE domains to different extents. Thus, the longer variants, V1 and V2, encode the unstructured domain and a partial fragment of the TAPE domain, whereas the shorter variants, V3 and V5, have none of the sequence encoding the TAPE domain. Interestingly, the presence of a TAPE domain fragment renders the V1 and V2 fusion proteins unstable and consequently they are dependent on the HSP90 chaperone for expression (Heuckmann et al., 2012; Richards et al., 2014). Indeed, binding to HSP90 might interfere with microtubule association as these longer variants localize poorly to the microtubule network despite containing the microtubule-binding region of EML4 (Richards et al., 2015). In theory, this observation identifies the use of HSP90 inhibitors as an alternative therapeutic approach for patients with the longer variants, although to date clinical trials of HSP90 inhibitors have not shown efficacy in ALK-positive patients (Chatterjee et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2010; Workman and van Montfort, 2014). Moreover, HSP90 inhibitors would not be useful in patients with EML4–ALK V3 or V5 because these fusion proteins are not dependent upon HSP90 for their expression. Furthermore, patients with V3 respond less well to ALK inhibitors, suggesting that additional tumorigenic mechanisms that may be independent of ALK activity exist (Woo et al., 2017). This is important because V3 represents up to 50% of EML4–ALK fusions in NSCLC (Choi et al., 2010, 2008; Christopoulos et al., 2018; Sasaki et al., 2010; Woo et al., 2017).

Wild-type EML proteins have been found to interact with members of the human NEK kinase family (Ewing et al., 2007). The human genome encodes eleven NEKs, named NEK1 to NEK11, many of which exhibit cell cycle-dependent activity and have functions in microtubule organization (Fry et al., 2017, 2012; Moniz et al., 2011). NEK9, NEK6 and NEK7 are activated in mitosis and act together to regulate mitotic spindle assembly, with NEK9 acting upstream of NEK6 and NEK7 (Sdelci et al., 2011). NEK6 and NEK7 are the shortest of the NEKs, consisting solely of a kinase domain with a short N-terminal extension that determines their substrate specificity (de Souza et al., 2014; Vaz Meirelles et al., 2010). Moreover, NEK6 and NEK7 are ∼85% identical within their catalytic domains. NEK9 is one of the longest NEKs, consisting of an N-terminal catalytic domain (residues 52–308) followed by a C-terminal regulatory region (residues 309–979). Within this C-terminal region is an RCC1 (regulator of chromatin condensation 1)-like domain (residues 347–726) that is predicted to fold into a seven-bladed β-propeller. Biochemical studies indicate that deletion of the RCC1-like domain causes constitutive activation of NEK9, indicating that this domain has an auto-inhibitory function (Roig et al., 2002). The RCC1-like domain is followed by a C-terminal tail that contains a coiled-coil motif (residues 891–939) that promotes NEK9 dimerization (Roig et al., 2002). NEK9 directly interacts with NEK7, and presumably with NEK6, through a short sequence (residues 810–828) that lies between the RCC1-like domain and the coiled-coil motif (Haq et al., 2015). NEK9 stimulates NEK6 and NEK7 kinase activity through multiple mechanisms, including activation loop phosphorylation, dimerization-induced autophosphorylation, and allosteric binding-induced reorganization of catalytic site residues (Belham et al., 2003; Haq et al., 2015; Richards et al., 2009).

Here, we demonstrate that expression of not only activated NEK9 and NEK7 kinases but also full-length EML4 and the short EML4–ALK variants that bind microtubules (V3 and V5), alters cell morphology and promotes cell migration. These changes are not seen in cells expressing the longer EML4–ALK variants (V1 and V2) that do not bind microtubules. Moreover, our data reveal an interaction between the EML4 NTD and NEK9, and suggest a model in which the EML4–ALK V3 and V5 proteins stabilize microtubules and perturb cell behaviour through recruitment of NEK9 and NEK7 to microtubules. Finally, we show that EML4–ALK lung cancer patients exhibit a significant correlation between expression of either V3 or V5 and high levels of NEK9 protein, and demonstrate that elevated NEK9 expression is associated with worse progression-free survival, raising the prospect of novel therapeutic approaches for these patients.

RESULTS

Constitutively active NEK9 alters interphase cell morphology and stabilizes microtubules

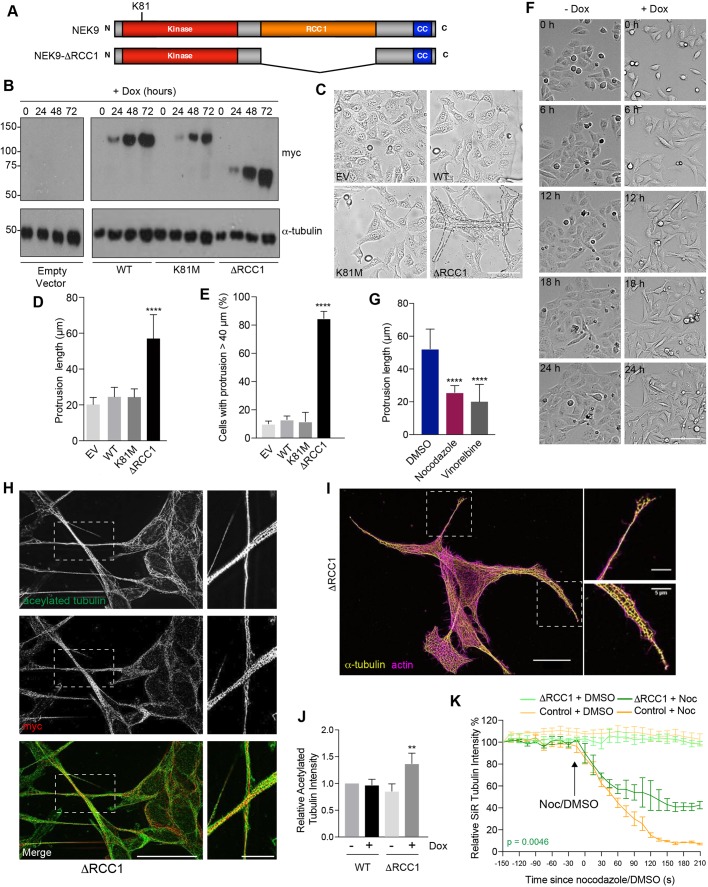

We initially set out to explore the function of NEK9 by analysing the consequences of its untimely activation in interphase cells. For this, an inducible system was established in which expression of myc-tagged wild-type NEK9, a full-length kinase-inactive mutant (K81M), and a constitutively activated mutant lacking the RCC1-like domain (ΔRCC1) was placed under the control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter in U2OS osteosarcoma cells (Fig. 1A). Western blots indicated time-dependent induction of expression of all three recombinant proteins upon addition of doxycycline, while subcellular localization confirmed the previously described cytoplasmic localization of the full-length and activated (ΔRCC1) proteins, and nuclear localization of the catalytically-inactive mutant (Roig et al., 2002) (Fig. 1B; Fig. S1A). Flow cytometry indicated no significant change in cell cycle distribution upon induction of these NEK9 proteins (Fig. S1B). Unexpectedly, brightfield and immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that induction of activated NEK9 led to a change in interphase cell morphology with the formation of long cytoplasmic protrusions that were not seen upon induction of either wild-type or catalytically-inactive NEK9 (Fig. 1C–E; Fig. S1C). Time-lapse imaging indicated that these protrusions were comparatively stable structures that did not undergo retraction except during cell division (Fig. 1F). Depolymerization of the microtubule network using nocodazole or vinorelbine treatment caused loss of these protrusions indicating that they are microtubule-dependent (Fig. 1G), while super-resolution microscopy revealed that protrusions contained not only microtubules and the activated NEK9 protein but also actin and acetylated tubulin (Fig. 1H,I). Western blotting confirmed that the induction of activated NEK9 was associated with an increase in overall expression of acetylated tubulin, a marker of stabilized microtubules (Fig. 1J). Consistent with this observation, time-lapse imaging of live cells incubated with the fluorescent SiR-tubulin probe (Lukinavičius et al., 2014) demonstrated that microtubules were more resistant to nocodazole-induced depolymerization following induction of the activated NEK9 kinase (Fig. 1K; Fig. S1D). Hence, activation of NEK9 leads to a microtubule-dependent change in interphase cell morphology characterized by formation of elongated cytoplasmic protrusions that contain both actin and stabilized microtubules.

Fig. 1.

Constitutively active NEK9 induces altered morphology and stabilized microtubules in interphase cells. (A) Schematic representation of full-length and activated NEK9, showing the kinase, RCC1 and coiled-coil (CC) domains. The position of the inactivating K81M mutation is indicated. (B) U2OS stable cell lines were induced (+Dox) to express wild-type (WT), catalytically inactive (K81M) or constitutively active (ΔRCC1) myc–NEK9 for 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. Lysates were prepared and analysed by western blotting with myc and α-tubulin antibodies. U2OS cells with the tetracycline-inducible plasmid (empty vector, EV) were used as a negative control. Blots shown are representative of n=3 experiments. (C) Phase-contrast images of cells as described in B that were induced to express NEK9 proteins for 48 h prior to imaging. Scale bar: 50 µm. (D) The maximum length of cytoplasmic protrusions for cells as prepared in C is indicated. (E) The percentage of cells with protrusions exceeding 40 µm for cells as prepared in C is indicated. (F) Still images from time-lapse phase-contrast imaging of U2OS:myc–NEK9 ΔRCC1 cells with or without doxycycline for the times indicated. Scale bar: 100 µm. Images are representative of n=3 experiments. (G) Dox-induced U2OS:myc–NEK9 ΔRCC1 cells were treated with DMSO, nocodazole or vinorelbine then analysed by phase-contrast microscopy. The maximum length of cytoplasmic protrusions measured is shown. (H) U2OS:myc–NEK9 ΔRCC1 cells were analysed by immunofluorescence microscopy with myc and acetylated tubulin antibodies. Images reconstructed using SRRF analysis are shown. Images are representative of n=3 experiments. (I) U2OS:myc–NEK9 ΔRCC1 cells were analysed by immunofluorescence microscopy with α-tubulin antibodies while actin was stained with phalloidin–FITC. Images reconstructed using SRRF analysis are shown. Images are representative of n=3 experiments. In H and I, magnified views of cytoplasmic protrusions are shown on the right. The locations of the magnified views are indicated by boxed regions in the images on the left. Scale bars: 20 µm (main images) and 5 µm (magnified views). (J) Cell lysates prepared from U2OS:myc–NEK9 WT and ΔRCC1 cells were western blotted with acetylated tubulin and GAPDH antibodies. The intensity of acetylated tubulin relative to GAPDH is indicated. (K) U2OS:myc–NEK9 WT and ΔRCC1 cells were incubated with SiR-Tubulin. Measured SiR-Tubulin intensity before and after addition of nocodazole or DMSO (arrow) is shown.

Activated NEK9 stimulates cell migration

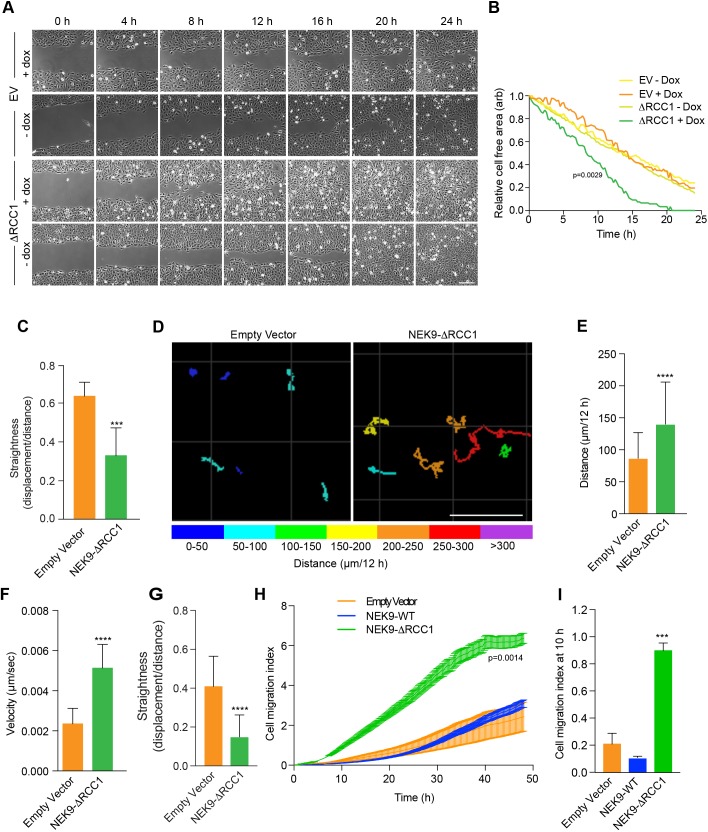

Time-lapse imaging of cells expressing the activated NEK9 construct suggested that these cells not only underwent a change in morphology but also exhibited increased migration. To test whether activated NEK9 alters parameters of cell migration, the rate of closure of a scratch wound on 2D cell culture plates was measured. This revealed that cells induced to express the activated NEK9 closed the wound more quickly than cells containing an empty vector or cells containing the activated NEK9 construct but without induction (Fig. 2A,B). This difference in wound closure did not appear to result from increased persistence during directional migration into the wound, as the ΔRCC1 cells migrated with reduced straightness compared to the migration of control cells (Fig. 2C). Individual cell tracking experiments in sparsely plated cells confirmed a significant increase in the velocity of migration, as well as the distance travelled, in isolated cells induced to express activated NEK9 (Fig. 2D–F). Furthermore, in the absence of a chemoattractant, there was a decrease in the straightness of migration of isolated cells in the presence of activated NEK9, consistent with more frequent changes in direction of migration (Fig. 2G). Finally, continuous monitoring of cell migration using a real-time Transwell migration assay provided further evidence that induction of activated NEK9 led to an increased rate of migration; this was evident at 10 h after induction and therefore is not a result of increased proliferation (Fig. 2H,I). Because this assay measures 2D migration in response to serum, the results suggest that accelerated migration can occur in a directional manner in the presence of a chemoattractant, as might be expected if growth factor receptors are expressed on the cytoplasmic protrusions. Taken together, these data demonstrate that activated NEK9 not only leads to a change in interphase cell morphology but also enhances cell migration.

Fig. 2.

Activated NEK9 increases cell migration. (A) U2OS:myc–NEK9–ΔRCC1 or EV (empty vector) cells with or without dox induction were imaged to observe closure of a scratch wound. Representative images at time-points indicated are shown (n=3 experiments). Scale bar: 200 µm. (B) Rates of wound closure for cells imaged as described in A are shown. Data are representative of n=3 experiments. (C) The persistence of movement for cells at the leading edge of wounds generated as in A, as measured by quantifying track straightness for each cell. (D) U2OS:myc–NEK9 ΔRCC1 or EV were induced for 24 h, transfected with YFP for 24 h and subsequently imaged by time-lapse microscopy. Movement of individual cells was tracked over a 12 h period by following the position of the YFP signal. The total distance travelled is shown, colour-coded as indicated (µm). Scale bar: 100 µm. (E) The mean distance travelled by cells treated as in D is shown. (F) The mean velocity of cells treated as in D is indicated. (G) The persistence of movement for cells treated as in D as measured by quantifying track straightness (track displacement/track length) for each cell. (H) U2OS:myc–NEK9 WT, ΔRCC1 or EV were induced for 24 h before being starved in serum-free medium for a further 24 h, and seeded in RTCA CIM-16 plates. Complete medium containing 10% FBS was used as a chemoattractant and impedance measurements were used to determine cell migration in real time. The cell migration index over the course of the assay is shown. (I) The histogram shows the cell migration index at 10 h from RTCA assays as presented in H.

NEK9-induced changes in cell morphology and migration are dependent on NEK7

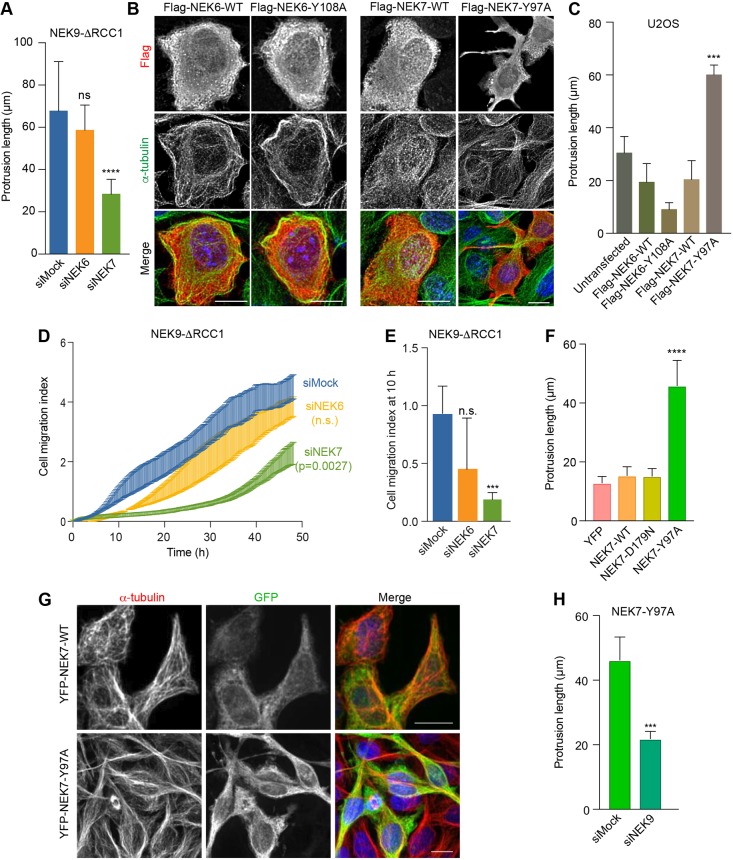

A major function of NEK9 activity in mitosis is to activate NEK6 and NEK7 (Fry et al., 2017). This is thought to occur via both phosphorylation of activation loop residues and allosteric binding (Belham et al., 2003; Richards et al., 2009). Indeed, biochemical and structural studies have revealed direct interaction between residues 810–828 of NEK9 and a groove on the C-terminal lobe of the NEK7 catalytic domain (Haq et al., 2015). To determine whether the change in interphase cell morphology and migration induced by activated NEK9 is dependent on NEK6 or NEK7, cells expressing activated NEK9 were depleted of NEK6 or NEK7 (Fig. S2A). Quantitative imaging revealed that, in contrast to mock- or NEK6-depleted cells, which still exhibited extended cytoplasmic protrusions upon induction of activated NEK9, NEK7-depleted cells exhibited reduced protrusion formation (Fig. 3A; Fig. S2B). This suggested that the protrusion phenotype was dependent upon the untimely activation of NEK7 by NEK9. To confirm this hypothesis, we made use of a constitutively active mutant version of NEK7. Previous studies have revealed that, in the absence of NEK9, NEK7 adopts an auto-inhibited conformation in which the side-chain of Tyr97 blocks the active site, and that mutation of this residue to alanine relieves this inhibition (Richards et al., 2009). Strikingly, transient expression of the activated NEK7-Y97A mutant, but not wild-type NEK7, caused the generation of elongated cytoplasmic protrusions in U2OS cells (Fig. 3B,C), similar to those formed following induction of activated NEK9. Consistent with the lack of effect of NEK6 depletion, expression of the equivalent activated NEK6-Y108A mutant did not cause formation of cytoplasmic protrusions but rather caused cells to become more rounded. Real-time Transwell assays indicated that the increase in cell migration induced by activated NEK9 was also dependent on NEK7 but not NEK6 and, as it was detected after 10 h, unlikely to be explained by reduced proliferation (Fig. 3D,E; Fig. S2C,D).

Fig. 3.

NEK9-induced alterations in cell morphology and migration are dependent on NEK7. (A) U2OS:myc–NEK9–ΔRCC1 cells were depleted as indicated. Cells were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy and the maximum lengths of interphase cytoplasmic protrusions measured are shown. (B) U2OS cells were transiently transfected with wild type (WT) or constitutively active FLAG–NEK6 (Y108A) or FLAG–NEK7 (Y97A), as indicated, before being processed for immunofluorescence microscopy with FLAG (green) and α-tubulin (red) antibodies. DNA (blue) was stained with Hoechst 33258. Scale bars: 10 µm. Images shown are representative of n=3 experiments. (C) The maximum length of interphase cytoplasmic protrusions for cells as described in B. (D) U2OS:myc–NEK9–ΔRCC1 cells were depleted as indicated, and cell migration was analysed in real time as described in Fig. 2H. Cell migration index over the course of the assay is shown. (E) Cell migration index at 10 h from the RTCA assays as shown in D. (F) HeLa:YFP, or YFP–NEK7 WT, D179N or Y97A cells were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy. The maximum length of interphase cytoplasmic protrusion is shown. (G) HeLa:YFP–NEK7 WT and Y97A cells were analysed by immunofluorescence microscopy with GFP (green) and α-tubulin (red) antibodies. Scale bars: 20 µm. Images shown are representative of n=3 experiments. (H) HeLa:YFP–NEK7 Y97A were depleted as indicated and cells were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy. The maximum length of interphase cytoplasmic protrusions measured is shown.

To further address the role of NEK7 in this pathway, we established HeLa cell lines in which YFP-tagged wild-type, catalytically-inactive (D179N) and constitutively-active (Y97A) versions of NEK7 were expressed under the control of a tetracycline inducible promoter (Fig. S3). Consistent with the results of our transient expression experiments, inducible expression of activated NEK7 but not wild-type or kinase-inactive NEK7 resulted in the formation of microtubule-rich cytoplasmic protrusions in interphase cells (Fig. 3F,G). Interestingly, protrusions that formed upon expression of activated NEK7 were lost upon depletion of NEK9 suggesting that NEK9 does not simply act upstream to enhance NEK7 catalytic activity (Fig. 3H). Taken together, these data indicate that the microtubule-dependent alteration of cell morphology and increased rate of migration that occur upon activation of NEK9 are dependent on NEK7, whereas similar changes induced upon activation of NEK7 require the presence of NEK9 protein.

EML4 interacts with NEK9 and promotes cell migration

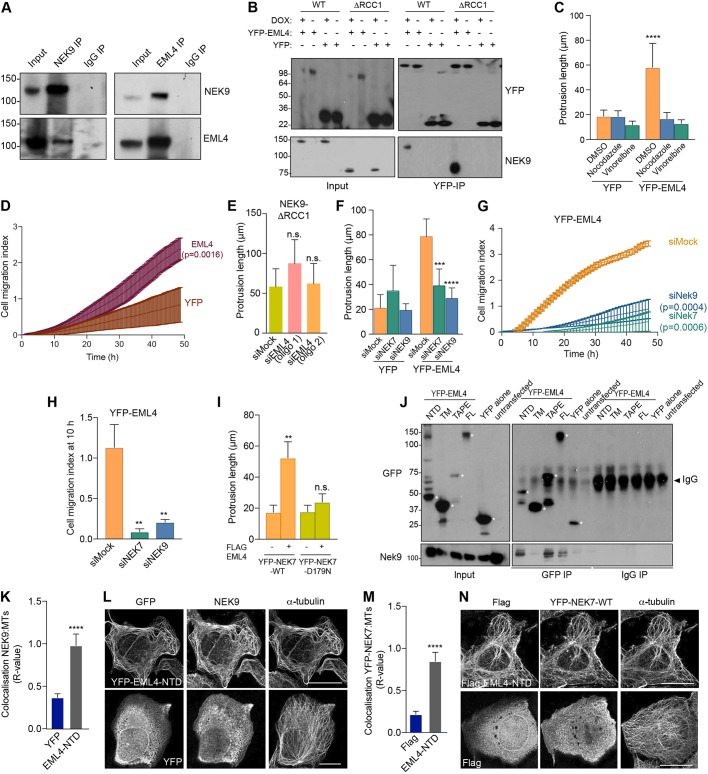

To further explore the mechanism through which the NEK9–NEK7 pathway might cause changes in cell morphology and migration, myc-tagged wild-type NEK9 was immunoprecipitated from asynchronous cells, and the precipitated immune complexes were analysed by mass spectrometry. Intriguingly, this identified not only tubulin, supporting the notion that NEK9 can interact with interphase microtubules, but also the microtubule-associated protein, EML4 (Fig. S4A–C). Previous large-scale proteomic mapping had identified EML2, EML3 and EML4 as potential binding partners of NEK6 (Ewing et al., 2007), while we have recently found that EML4 can be phosphorylated by NEK6 and NEK7 in mitosis (Adib et al., 2019). Western blotting of immunoprecipitates prepared using antibodies against either NEK9 or EML4 confirmed an interaction between endogenous EML4 and NEK9 in extracts prepared from asynchronous U2OS cells (Fig. 4A). Moreover, YFP–EML4 was found to co-precipitate as well, if not more strongly, with the activated NEK9-ΔRCC1 mutant than with wild-type NEK9 (Fig. 4B). As described above, NEK9 binds directly to NEK7 and NEK6 through its C-terminal region (residues 810–828), an interaction that is normally blocked in interphase by competitive interaction with the LC-8 adaptor protein (also known as DYNLL1) (Haq et al., 2015; Regué et al., 2011). Removal of the RCC1 domain somehow relieves the auto-inhibited conformation and leads to increased NEK9 kinase activity (Roig et al., 2002). This in turn enables autophosphorylation at Ser944, which displaces LC-8 and allows interaction with NEK7 and NEK6 (Regué et al., 2011). Hence, we propose that activated NEK9 can potentially interact simultaneously with both EML4 and NEK7.

Fig. 4.

EML4 induces NEK9-dependent changes in cell morphology and migration, and recruits NEK9 and NEK7 to interphase microtubules. (A) U2OS cell lysates (inputs) and immunoprecipitates (IP) were prepared with rabbit NEK9, EML4 and control IgGs and analysed by western blotting with the indicated antibodies. (B) U2OS:myc–NEK9–WT or ΔRCC1 cells were transfected with YFP–EML4 or YFP alone. Lysates (input) and immunoprecipitates (IP) were prepared with GFP antibodies and analysed by western blotting with the indicated antibodies. (C) U2OS:YFP or U2OS:YFP–EML4 cell lines were treated as indicated for 16 h before analysis by phase-contrast microscopy. The maximum length of interphase cytoplasmic protrusions measured is shown. (D) Cell migration of U2OS:YFP or U2OS YFP–EML4 cells was analysed in real time as in Fig. 2H. The cell migration index over the course of the assay is shown. (E) U2OS:myc–NEK9–ΔRCC1 were depleted with mock or two different siRNAs against EML4. The maximum length of interphase cytoplasmic protrusion is shown. (F) U2OS:YFP or U2OS:YFP–EML4 cells were depleted as indicated before being analysed by phase-contrast microscopy. The maximum length of interphase cytoplasmic protrusion is shown. (G) U2OS:YFP–EML4 cells were depleted as indicated and cell migration was analysed in real time as in Fig. 2H. The cell migration index over the course of the assay is shown. (H) Cell migration index at 10 h from the data in G. (I) HeLa:YFP–NEK7 WT or D179N were transfected with FLAG–EML4 for 24 h. The maximum length of cytoplasmic protrusion for transfected cells is shown. (J) U2OS cells were transfected with YFP–EML4 full length (FL), TM (trimerization motif), TAPE domain, NTD domain or YFP alone for 24 h. Lysates (inputs) and immunoprecipitates (IP) were prepared with GFP and control IgGs and analysed by western blotting with the antibodies indicated. Asterisks indicate the proteins of interest. (K) U2OS cells were transfected with YFP alone or YFP–EML4 NTD before being processed for immunofluorescence microscopy with antibodies against GFP, NEK9 and α-tubulin. Colocalization between the Nek9 and α-tubulin signals is shown. (L) Representative images of cells analysed in K. Scale bars: 10 µm. (M) HeLa:YFP–NEK7 cells were transfected with FLAG alone or FLAG–EML4 NTD for 24 h. Cells were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy with antibodies against FLAG, GFP and α-tubulin. Colocalization between the YFP–NEK7 fluorescence and α-tubulin signals is shown. (N) Representative images of cells analysed in M. Scale bars: 10 µm. R values in K and M show the mean±s.d. Pearson's correlation coefficient from five lines per cell in ten cells taken from a total of n=3 experiments. Blots shown in A, B and J are representative of n=3 experiments.

To investigate whether the microtubule-dependent changes in cell morphology that result from expression of activated NEK9 and NEK7 might relate to its interaction with EML4, U2OS cell lines were generated that stably expressed YFP alone or YFP–EML4. Proteins of the predicted size were expressed, as determined by western blotting, and the YFP–EML4 protein localized, as expected, to the microtubule network (Fig. S5A–C). In contrast to parental cells or cells expressing YFP alone, the YFP–EML4 cells exhibited a morphology similar to that of cells expressing activated NEK9 or NEK7, with extended cytoplasmic protrusions that were lost upon treatment with the microtubule depolymerizing agents nocodazole or vinorelbine (Fig. 4C; Fig. S5D). Individual cell tracking experiments, as well as real-time Transwell migration assays, revealed that cells expressing YFP–EML4 had an increased rate, distance and velocity of migration, but reduced straightness of migration, compared to those of cells expressing YFP alone (Fig. 4D; Fig. S5E–H). To test the relationships between EML4, NEK9 and NEK7 in the generation of these phenotypes, proteins were depleted in the different stable cell lines. Depletion of EML4 did not prevent the alterations in cell morphology induced upon expression of activated NEK9 (Fig. 4E; Fig. S5I). By contrast, depletion of NEK9 or NEK7 led to loss of cytoplasmic protrusions and reduced migration in cells expressing YFP–EML4 (Fig. 4F–H; Fig. S5J,K). Furthermore, induced expression of catalytically inactive NEK7 prevented formation of cytoplasmic protrusions in cells overexpressing EML4 (Fig. 4I). These data indicate that the altered cell morphology and enhanced migration induced by overexpression of EML4 is dependent upon NEK9 and NEK7, and can be blocked by expression of inactive NEK7.

EML4 recruits NEK9 and NEK7 to microtubules

To understand how NEK9 and NEK7 act downstream of EML4 to induce alterations in cell morphology and migration, we first examined whether specific regions of the EML4 protein are responsible for interaction with NEK9. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that endogenous NEK9 could interact not only with full-length EML4 but also with both the isolated NTD and TAPE domains (Fig. 4J). Conversely, it did not interact with a shorter fragment of the NTD that only encompassed the trimerization motif. We then hypothesized that EML4 might promote recruitment of NEK9 to the microtubule cytoskeleton. To test this hypothesis, we examined the localization of endogenous NEK9 in cells expressing different EML4 constructs. In cells expressing the TAPE domain, endogenous NEK9 was mainly distributed in the cytoplasm and was only faintly detected on microtubules, whereas in cells expressing the NTD, NEK9 exhibited strong recruitment to microtubules (Fig. 4K,L; Fig. S6A). Meanwhile, using the stable YFP–NEK7 HeLa cell line (because localization of endogenous NEK7 is difficult to detect with currently available antibodies), it was found that NEK7 was recruited to microtubules upon transfection of FLAG-tagged EML4 NTD, but not upon transfection of similarly tagged TAPE domain (Fig. 4M,N; Fig. S6B). Taken together, these data suggest a model in which the EML4 NTD recruits both NEK9 and NEK7 to microtubules. This explains not only how EML4 can act upstream of NEK9 and NEK7, but also why the NEK9 protein is required for activated NEK7 to promote microtubule-dependent changes in cell morphology and migration.

EML4–ALK V3 and V5, but not V1 or V2, induce altered cell morphology and migration

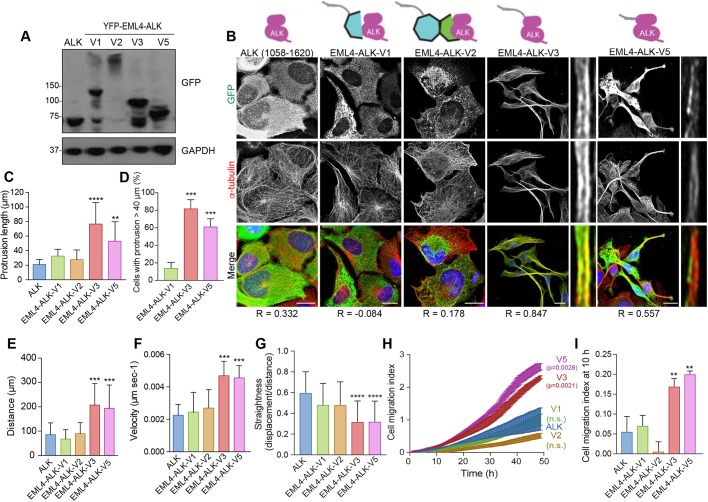

Considering their importance in cancer biology, we were intrigued to know whether EML4–ALK fusion proteins might also alter cell morphology and migration. To explore this possibility, we generated U2OS cell lines that stably expressed the ALK kinase domain alone or four of the different EML4–ALK variants (Fig. 5A). These included the longer variants, V1 and V2, which encode unstable proteins that do not localize to microtubules, and the shorter variants, V3 and V5, which encode stable proteins that do localize to microtubules (Richards et al., 2014, 2015). Strikingly, microscopic analysis revealed that those cells expressing the stable variants that localize to interphase microtubules (V3 and V5) formed extended cytoplasmic protrusions, whereas those cells expressing the unstable variants that do not localize to the microtubules (V1 and V2) did not (Fig. 5B–D). Furthermore, both individual cell tracking and real-time Transwell assays revealed that expression of V3 and V5 stimulated cell migration, causing significant increases in distance and velocity, whereas expression of V1 and V2 did not (Fig. 5E–I). Hence, expression of the short EML4–ALK variants that localize to microtubules leads to altered morphology and enhanced migration as compared to the morphology and migration of cells expressing the longer EML4–ALK variants that do not localize to microtubules.

Fig. 5.

EML4–ALK variants that bind microtubules alter cell morphology and migration. (A) U2OS cell lines stably expressing YFP-tagged EML4–ALK fusion variants were lysed and analysed by western blotting with antibodies indicated. Blots shown are representative of n=3 experiments. (B) U2OS stable cell lines expressing YFP-tagged proteins as in A were analysed by immunofluorescence microscopy with antibodies against GFP (green) and α-tubulin (red). DNA (blue) was stained with Hoechst 33258. Magnified views of individual microtubules are shown on the right of V3 and V5 images shown on the left. Schematic diagrams of the YFP-tagged proteins and the Pearson's correlation coefficient (R; mean of five lines per cell in ten cells from n=3 experiments) of colocalization with microtubules are shown. Scale bars: 10 µm. (C) The maximum length of interphase cytoplasmic protrusions for cells treated as in B. (D) The percentage of cells from C with protrusions greater than 40 µm is shown. (E) Individual cell tracking experiments were undertaken with YFP-tagged EML4–ALK variant cell lines and analysed as in Fig. 2D. The mean distance travelled is indicated. (F) As for E, but showing mean velocity of movement. (G) As for E but showing track straightness. (H) Migration of YFP-tagged EML4–ALK variant cell lines was analysed in real time as in Fig. 2H. The cell migration index over the course of the assay is shown. (I) The cell migration index at 10 h from the data in H.

The altered morphology and migration of EML4–ALK V3 cells depend on NEK9 and NEK7

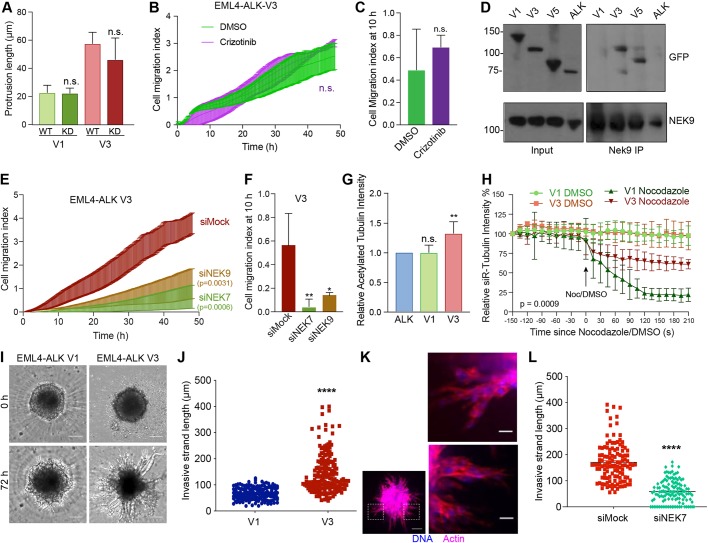

To determine whether the observed changes in cell morphology and migration induced by EML4–ALK V3 required catalytic activity of the ALK tyrosine kinase, we first generated U2OS cell lines that stably expressed catalytically inactive (D1270N) versions of EML4–ALK V1 and V3. Observation of these cell lines revealed that cells expressing the inactive mutant proteins had similar length cytoplasmic protrusions as those seen in cells expressing the wild-type proteins (Fig. 6A). Second, we determined the consequences on cell migration of treatment with the ALK inhibitor, crizotinib. This treatment did not alter the rate of migration of U2OS cells expressing EML4–ALK V3, despite preventing ALK-dependent signalling in these cells as expected (Fig. 6B,C; Fig. S7A). Hence, we conclude that the altered morphology and enhanced migration of cells expressing EML4–ALK V3 does not require ALK activity.

Fig. 6.

EML4–ALK V3 stabilizes microtubules and increases cell migration in a NEK9- and NEK7-dependent manner. (A) U2OS cells were transfected with WT and kinase dead (KD) YFP–EML4–ALK V1 and V3, as indicated, and analysed by immunofluorescence microscopy. The maximum length of interphase cytoplasmic protrusion for transfected cells is shown. (B) U2OS:YFP–EML4–ALK V3 cells were treated with DMSO or 100 nM Crizotinib and cell migration analysed in real time as in Fig. 2H. The cell migration index over the course of the assay is shown. (C) Cell migration index at 10 h from data in B. (D) U2OS: YFP–EML4–ALK cells, as indicated, were lysed. Lysates (inputs) and immunoprecipitates (IP) were prepared with NEK9 antibodies or control IgGs and analysed by western blotting using the antibodies indicated. Blots shown are representative of n=3 experiments. (E) U2OS:YFP–EML4–ALK V3 cells were mock-, NEK6- or NEK7-depleted and cell migration analysed in real time as in Fig. 2H. The cell migration index over the course of the assay is shown. (F) Cell migration index at 10 h from data in E. (G) Cell lysates prepared from U2OS:YFP–EML4–ALK V1 and V3 cells were western blotted with acetylated tubulin and GAPDH antibodies. The intensity of acetylated tubulin signal is plotted relative to GAPDH signal. (H) U2OS:YFP–EML4–ALK V1 and V3 were incubated with SiR-Tubulin. Measured SiR-Tubulin intensity before and after addition of nocodazole or DMSO (arrow) is shown. (I) Phase-contrast microscopy of invasion into Matrigel of dox-induced BEAS-2B:EML4–ALK V1 and V3 spheroids at time-points indicated. Scale bars: 100 µm. Images shown are representative of n=3 experiments. (J) Length of invasive strands after 72 h for cells as described in I. (K) Cells were treated as in I but fixed and actin stained with TRITC-phalloidin (red) and DNA stained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Magnified views of chains of cells shown on the right are taken from the boxed regions of the spheroid on the left. Scale bars: 20 µm (magnified views), 100 µm (whole image). Images shown are representative of n=3 experiments. (L) EML4–ALK V3 cells were treated as in I except cells were also transfected with Nek7 siRNAs. The length of invasive strands is shown. Horizontal line indicates mean strand length.

Because all four EML4–ALK variants under analysis here contain the EML4 NTD, which can interact with NEK9, we tested whether these oncogenic fusion variants also bind NEK9. Surprisingly, co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed that endogenous NEK9 interacts with EML4–ALK V3 and V5, but not with V1 or the ALK domain alone (Fig. 6D). This reflects a similar difference in the ability of the variants to bind microtubules and, while the explanation remains unknown, it is possible that interaction with both NEK9 and microtubules is prevented in V1 and V2 either by misfolding of the NTD in the presence of the partial TAPE domain or competing association with chaperones. Real-time Transwell migration assays revealed that depletion of NEK9 or NEK7 significantly reduced the migration of cells expressing EML4–ALK V3 or V5 (Fig. 6E,F; Fig. S7B,C). Overexpression of wild-type EML4, as well as activated NEK9, can promote microtubule stabilization (Adib et al., 2019; Houtman et al., 2007). Hence, we wished to determine whether expression of EML4–ALK V3 also caused a similar increase in microtubule stabilization. Both western blot analysis of acetylated tubulin expression and measurement of the rate of nocodazole-induced microtubule depolymerization in live cells (using the SiR-tubulin probe) confirmed that cells expressing EML4–ALK V3 had increased microtubule stability as compared to cells expressing EML4–ALK V1 (Fig. 6G,H; Fig. S7D).

We then expressed EML4–ALK V1 and V3 in BEAS-2B bronchial epithelial cells as an alternative model for lung disease (Fig. S8A). Parental BEAS-2B cells exhibit a more elongated morphology than U2OS cells and their growth is subject to contact inhibition, as expected for non-cancer-derived cells. For this reason, it was not possible to measure changes in cell morphology or the rate of migration in a wound-healing assay with these cells. However, they do form three-dimensional (3D) spheroids when grown on ultra-low attachment plates, allowing us to analyse the consequences of expression of these fusion variants on 3D migration into Matrigel. Strikingly, we found that expression of EML4–ALK V3, but not V1, led to the generation of extended chains of BEAS-2B cells typical of collective cell migration (Fig. 6I–K). Moreover, there was a significant reduction in the length of these chains when cells expressing EML4–ALK V3 were first depleted of NEK7 (Fig. 6L; Fig. S8B). We therefore conclude that expression of EML4–ALK V3 but not V1 leads to NEK9- and NEK7-dependent alterations in cell morphology and migration, and to enhanced stabilization of microtubules.

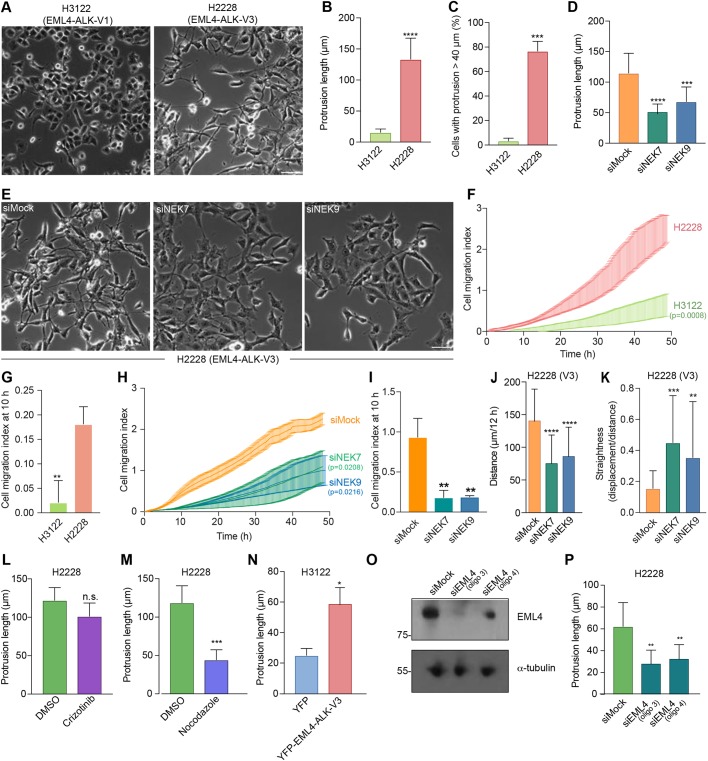

Cells from EML4–ALK V3 NSCLC patients exhibit NEK9- and NEK7-dependent alterations in morphology and migration

To determine whether the altered cell morphology and migration observed in U2OS cell lines might be relevant to tumour progression in NSCLC patients, we first examined the morphology and migration of established cell lines derived from patients expressing different EML4–ALK variants. H3122 cells are derived from an NSCLC tumour that expresses V1, whereas H2228 are derived from an NSCLC tumour that expresses V3. Brightfield microscopy revealed that, whereas H3122 cells exhibit a cobblestone appearance, H2228 cells have a spindle-like morphology with extended cytoplasmic protrusions (Fig. 7A–C). As observed in U2OS cells, the protrusions present in H2228 cells were significantly reduced in length upon depletion of either NEK7 or NEK9 (Fig. 7D,E; Fig. S8C). Real-time Transwell migration assays revealed that the H2228 cells exhibited a significantly increased rate of migration as compared to the migration of H3122 cells, while this was reduced by depletion of NEK7 or NEK9 (Fig. 7F–I). Individual cell tracking experiments indicated that depletion of NEK7 or NEK9 reduced the distance and increased the straightness of migration in H2228 but not H3122 cells (Fig. 7J,K; Fig. S8D,E). Again consistent with data from experiments using U2OS cells, the elongated protrusions present in H2228 cells were not affected by treatment with the ALK inhibitor crizotinib, whereas they were reduced in length upon depolymerization of microtubules with nocodazole (Fig. 7L,M). Importantly, to confirm that the differences observed between H2228 cells and H3122 cells were caused by the different EML4–ALK variants expressed, we first transfected H3122 cells with YFP–EML4–ALK V3. This caused a significant increase in the length of interphase cytoplasmic protrusions in H3122 cells (Fig. 7N). Second, we depleted EML4–ALK V3 from H2228 cells and found that this led to a significant reduction in cytoplasmic protrusion length (Fig. 7O,P). Taken together, these data provide persuasive evidence that the different behaviour of these established NSCLC patient cells results from the different EML4–ALK fusion variants that they express.

Fig. 7.

Depletion of NEK7 or NEK9 reduces migration of NSCLC patient cells expressing microtubule-binding EML4–ALK variants. (A) Representative phase-contrast images of H3122 and H2228 cells. (B) Maximum length of interphase cytoplasmic protrusions for H3122 and H2228 cells. (C) The percentage of cells from B with protrusions greater than 40 µm is indicated. (D) H2228 cells were depleted with NEK7 or NEK9 siRNAs. The maximum length of cytoplasmic protrusions for mock- and NEK-depleted cells is shown. (E) Representative phase-contrast images of cells treated as described in D. (F) H3122 and H2228 cell migration was analysed in real time as in Fig. 2H. The cell migration index over the course of the assay is shown. (G) Cell migration index at 10 h for cells in F is shown. (H) H2228 cells were depleted as indicated and migration analysed in real time as in Fig. 2D. The cell migration index over the course of the assay is shown. (I) Cell migration index at 10 h for cells in H is shown. (J,K) H2228 cells that were mock- or NEK9-depleted were analysed by individual cell tracking as in Fig. 2D. Mean distance travelled is shown in J, and track straightness is shown in K. (L,M) The maximum length of interphase cytoplasmic protrusions of H2228 cells treated with crizotinib (L) or nocodazole (M) is shown. Control cells were treated with DMSO. (N) H3122 cells were transfected with either YFP alone or YFP–EML4–ALK V3. The maximum length of interphase cytoplasmic protrusions for transfected cells is shown. (O) Lysates were prepared from H2228 cells that were either mock transfected or transfected with two alternative siRNAs (siEML4 oligo 3 and oligo 4) designed to target the portion of EML4 found in EML4–ALK V3. Western blots of the lysates using the indicated antibodies are shown. Blots are representative of n=3 experiments. (P) Maximum length of interphase cytoplasmic protrusions for cells treated as in O. Scale bars in A and E: 100 µm. Images in A and E are representative of n=3 experiments.

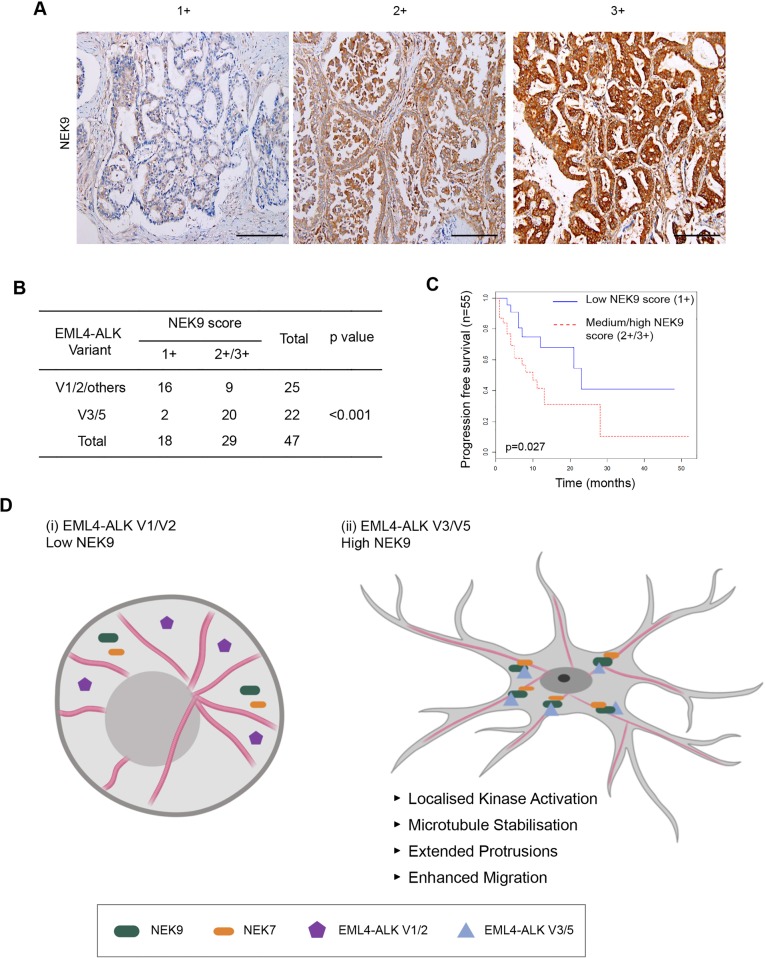

Lung cancer patients with EML–ALK V3 exhibit upregulation of NEK9

Experiments using established cell lines suggest that the more aggressive properties associated with EML4–ALK V3 as compared to V1 might in part be caused by a NEK9-dependent pathway that promotes cell migration. This hypothesis would require NEK9 protein to be expressed in EML4–ALK V3 tumours. To test this, we used immunohistochemistry to examine NEK9 expression in a cohort of primary tumours from patients with ALK-positive stage IV advanced lung adenocarcinoma. Remarkably, this revealed that although the majority of tumours expressing V1 or V2 (or others) had low levels of NEK9 expression (64%, n=25), the majority of tumours expressing V3 or V5 had medium or high levels of NEK9 expression (91%, n=22), with an overall significant difference between the V1/V2/others cohort and the V3/V5 cohort of P<0.001 (Fig. 8A,B). Intriguingly, ALK-positive lung cancer patients with medium or high NEK9 expression also exhibited worse progression-free survival (P=0.027) than patients with low NEK9 expression (Fig. 8C). Assessment of clinicopathological features revealed no association of NEK9 expression with gender, age or smoking history. However, EML4–ALK patients with low NEK9 expression had on average undergone more rounds of previous treatment, suggestive of more prolonged and potentially less aggressive disease, than those patients with moderate or high NEK9 expression (Tables S1 and S2). Clearly, further work will be required to define the molecular events that underpin the apparent link between elevated NEK9, EML4–ALK variant expression and survival. However, these findings raise the exciting possibility not only that these patients could be amenable to treatments that target NEK9 or NEK7, but also that this pathway represents an important mechanism through which EML4–ALK variants that bind microtubules accelerate lung cancer progression (Fig. 8D).

Fig. 8.

Elevated NEK9 expression correlates with EML4–ALK V3 or V5 genotype in NSCLC patient tumours as well as poor overall survival. (A) Representative images of tumour biopsies from NSCLC patients that were processed for immunohistochemistry with NEK9 antibodies (brown) and scored as low (1+), medium (2+) or high (3+) expression. Tissue was also stained with haematoxylin to detect nuclei (blue). Scale bars: 200 μm. (B) NEK9 expression, scored as in A, with respect to the EML4–ALK variant present. (C) Kaplan–Meier plot indicating the progression-free survival of NSCLC patients with EML4–ALK fusions that had low (1+) or medium/high (2+/3+) NEK9 expression (n=32). (D) Schematic model showing rationale for stratification of cancer patients for treatment based on EML4–ALK variant. (i) The majority of tumours expressing EML4–ALK V1 or V2 express low levels of NEK9. In these cells, the EML4–ALK protein neither binds NEK9 nor colocalizes with microtubules, and cells retain a more rounded morphology. (ii) However, the majority of tumours expressing EML4–ALK V3 or V5 express moderate or high levels of NEK9. In these cells, the EML4–ALK protein binds and recruits NEK9 and NEK7 to microtubules leading to localized kinase activity that promotes microtubule stabilization, formation of extended cytoplasmic protrusions and enhanced migration.

DISCUSSION

A better understanding of the processes that drive progression and metastatic dissemination of EML4–ALK tumours is urgently required as this will identify opportunities for development of new therapeutic approaches to treat ALK inhibitor-resistant NSCLC. Here, we show that the short EML4–ALK variants, including the common V3, promote microtubule-dependent changes in cell morphology and enhance cell migration in both 2D and 3D models in a manner that could promote dysplastic development and metastasis. EML4–ALK V3 is associated with a poor response to ALK inhibitors, suggesting the existence of additional oncogenic mechanisms that are independent of ALK tyrosine kinase activity (Woo et al., 2017). Indeed, we found that the cellular changes induced by EML4–ALK V3 were not dependent on ALK activity. Experimentally, these short variants retain the capacity to bind microtubules, in contrast to the longer variants, V1 and V2, that encode destabilizing fragments of the EML4 TAPE domain and that rely on the HSP90 chaperone for expression (Richards et al., 2014). We speculate that either protein misfolding or chaperone interaction blocks the ability of the longer variants to associate with and regulate microtubules. We also show that the altered cell morphology and increased migration induced by the short EML4–ALK variants are dependent on the NEK9–NEK7 kinase module. Hence, these data not only reveal a novel mechanism through which EML4–ALK variants could promote cancer progression, but also reveal new biomarkers and targets that could be exploited for the treatment of patients with these oncogenic fusions.

NEK9 is required for assembly of the microtubule-based mitotic spindle. This role is consistent with the kinase achieving maximal activity in mitosis following phosphorylation by the CDK1 and PLK1 mitotic kinases (Fry et al., 2017). These phosphorylation events cause release of an auto-inhibited state that relies on the presence of an internal RCC1-like inhibitory domain (Roig et al., 2002). Upon inducible expression of an activated NEK9 mutant lacking this domain, we observed striking alterations in interphase cell morphology and enhanced cell migration. The mitotic functions of NEK9 are executed in part through phosphorylation of the microtubule nucleation adaptor protein NEDD1 (also known as GCP-WD), and in part through activation of two other members of the NEK family, NEK6 and NEK7 (Belham et al., 2003; Kaneta and Ullrich, 2013; Roig et al., 2005, 2002; Sdelci et al., 2012). Interestingly, we found that depletion of NEK7, but not NEK6, prevented the altered cell morphology and enhanced migration observed in interphase cells, arguing that activated NEK9 promotes these phenotypes through activation of NEK7. Indeed, similar phenotypes were generated by expression of constitutively active NEK7 but not by expression of constitutively active NEK6. These findings are consistent with growing evidence that NEK7 has microtubule-associated functions in interphase cells, with depletion of endogenous NEK7 interfering with interphase microtubule dynamics, the centrosome duplication cycle and ciliogenesis (Cohen et al., 2013; Gupta et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2011, 2007; Yissachar et al., 2006). Of particular interest to our findings, a kinase-dependent role was recently described for NEK7 in stimulating dendrite growth in post-mitotic neurons. This stimulation resulted from phosphorylation by NEK7 of the kinesin motor protein Eg5 (also known as KIF11), which in turn led to stabilization of microtubules (Freixo et al., 2018). As EML4 is highly expressed in neurons, we speculate that modulation of microtubule organization leading to altered neuronal morphology and migration might represent the normal physiological role for the EML4–NEK9–NEK7 pathway identified here. However, NEK7 can phosphorylate other motor proteins to control microtubule organization and interact with additional regulators of the microtubule and actin networks, offering alternative mechanisms through which this pathway could operate (Cullati et al., 2017; de Souza et al., 2014).

The discovery of EML4 as a binding partner for NEK9 provides new insight into how NEK9 might regulate microtubule dynamics. The EMLs are a family of relatively poorly characterized microtubule-associated proteins (Fry et al., 2016). Humans have six EMLs of which EML1, 2, 3 and 4 share a similar organization consisting of an NTD that encompasses a trimerization motif and basic region that binds microtubules, and a C-terminal TAPE domain that binds tubulin heterodimers (Richards et al., 2014, 2015). The possibility that EMLs may be interacting partners of NEKs was first raised by a proteomic study that identified association of NEK6 not only with NEK7 and NEK9, but also with EML2, EML3 and EML4 (Ewing et al., 2007). We identified EML4, as well as tubulin, in a mass spectrometry analysis for NEK9 binding partners, and interaction between endogenous EML4 and NEK9 was confirmed by western blotting. Co-immunoprecipitation studies revealed that NEK9 can bind to the isolated NTD of EML4, as well as to the EML4–ALK V3 and V5 proteins. Interestingly, it did not bind to EML4–ALK V1 despite this variant encoding the complete NTD. This suggests that misfolding or binding of chaperones might prevent interaction with NEK9 as well as microtubules. Further experiments revealed that the EML4 NTD was capable of recruiting both NEK9 and NEK7 to microtubules. This suggests that binding of the EML4 NTD to microtubules and to NEK9 is not mutually exclusive, although the fact that NEK9 and the EML4 NTD form dimers and trimers, respectively, means that this recruitment could rely on oligomerization of these proteins. We propose that recruitment of NEK7 relies on its direct interaction with NEK9, although we do not rule out an independent interaction with EML4. However, the fact that NEK9 is required for these morphological consequences, even in the presence of activated NEK7, suggests that NEK9 plays an essential role, potentially including the targeting of NEK7 to its downstream substrates. Moreover, although we have shown that expression of activated NEK9 and EML4–ALK V3 leads to stabilization of microtubules, further work is required to establish the mechanisms through which this pathway regulates cell morphology and migration.

Of major clinical significance is the fact that EML4–ALK fusion proteins act as oncogenic drivers in ∼5% of NSCLC patients (Soda et al., 2007). Unscheduled activation of the ALK tyrosine kinase is primarily responsible for driving tumorigenesis, as demonstrated by the fact that ALK inhibitors block transformation. First and second generation ALK inhibitors have revolutionized survival outcomes in ALK-positive lung cancer patients; however, resistance is inevitable, emerging through point mutations in the catalytic domain as well as through bypass pathways (Liao et al., 2015; Rolfo et al., 2014). Alternative targeted therapies would therefore be highly attractive and, in the case of the longer EML4-ALK variants, HSP90 inhibitors could provide an option. The longer variants are unstable proteins as a result of expressing an incomplete fragment of the highly structured TAPE domain. In the absence of the HSP90 chaperone they are rapidly degraded by the proteasome leading to loss of downstream proliferative signalling (Richards et al., 2014). HSP90 inhibitors have been tested in ALK-positive patients although, to date, clinical trials have yet to prove their efficacy (Katayama et al., 2015; Workman and van Montfort, 2014). However, the short variants of EML-ALK4 are not dependent on HSP90 for their expression and HSP90 inhibitor treatment is unlikely to be effective. Moreover, EML4–ALK V3 tumours appear less sensitive to ALK inhibitors in the first place emphasizing the need for alternative treatments for these particular patients (Woo et al., 2017). Demonstration that the downstream consequences on cell morphology and migration induced by these short variants is dependent on NEK9 and NEK7, but not ALK activity, raises the tantalizing prospect that inhibitors of this pathway might be beneficial in EML4–ALK V3 cancers where metastasis and ALK inhibitor resistance underpin lethality (Christopoulos et al., 2018). Although we have no evidence that inhibiting this pathway promotes cytotoxicity, the ability to block migration and invasion with so-called ‘migrastatics’ offers huge potential benefits in slowing disease progression in patients with solid cancers (Gandalovičová et al., 2017).

The significant correlation in patient samples between elevated NEK9 expression and the presence of EML4–ALK V3 is particularly intriguing as it implicates this pathway in the high metastatic potential of these tumours (Christopoulos et al., 2018; Doebele et al., 2012). However, although the association of elevated NEK9 with V3 and V5 was significant, expression does not necessarily reflect activation, and it will be important in the future to assess the catalytic activity of NEK9 and NEK7 in these tumours. Moreover, we cannot rule out that tumour cells with this variant exert positive selection for high expression of NEK9 either due to its role as a downstream target or as a result of their increased aggressiveness. Nevertheless, the reduced progression-free survival of patients with increased NEK9 expression potentially explains the poor response of these patients to ALK-based therapies, despite the fact that the different EML4–ALK variants bind ALK inhibitors with similar affinity (Heuckmann et al., 2012). This also adds further evidence that NEK9 could be an important prognostic factor for EML4–ALK lung cancers, and supports the hypothesis that targeting NEK9 or NEK7 could be beneficial in patients with EML4–ALK V3.

Finally, it is interesting to note that EML proteins are involved in other oncogenic fusions, including the EML1–ABL1 fusion found in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) (De Keersmaecker et al., 2005). Whether these fusion proteins also localize to microtubules and alter cell morphology and migration in a manner that is dependent on the microtubule network and the NEK9–NEK7 kinase module will be important to examine. Standard treatments for many cancers, including NSCLC and ALL, often involve microtubule poisons, such as vinorelbine or paclitaxel. Hence, it will also be worthwhile to explore the possibility that EML4–ALK variant status affects response to these drugs, and test whether there could be benefit to patients in combining microtubule poisons with targeted agents against ALK, HSP90 or indeed NEK9 or NEK7.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction and mutagenesis

Full-length EML4 cDNA was isolated by PCR from human cDNA (Clontech) and subcloned into a version of pcDNA3 or pcDNA3.1 Hygro (Invitrogen) providing sequences encoding N-terminal YFP or FLAG tags. YFP-tagged EML4–ALK variants and fragments of EML4, and FLAG-tagged NEK6 and NEK7 constructs were generated as previously described (O'Regan and Fry, 2009; Richards et al., 2014, 2015). A full-length myc-tagged cDNA expressing human NEK9 (NM_001329237.1) was subcloned into the pVLX-Tight-Puro vector (Clontech). The sequence encoding the RCC1 domain was deleted using the Quickchange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene), using the primer sequences 5′-gctgtagtaacatcacgaaccagtatccgttccaatagcagtggcttatcc-3′ and 5′-ggataagccactgctattggaacggatactggttcgtgatgttactacagc-3′. Point mutations in sequences encoding the NEK7, NEK6 and ALK catalytic domains were also introduced using the Quickchange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit. Constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing (University of Leicester).

Cell culture, drug treatments and transfection

HeLa, U2OS and derived stable cell lines were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with GlutaMAX™-I (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI-FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin, at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. H3122 and H2228 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% HI-FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. All cell lines were obtained from ATCC within the last 10 years, stored in liquid nitrogen and maintained in culture for a maximum of 2 months. We relied on the provenance of the original collections for authenticity, while mycoplasma infection was avoided through bimonthly tests using an in-house PCR-based assay. Doxycycline-inducible NEK9 stable U2OS cell lines were generated through lentiviral transduction of parental U2OS cells stably carrying the pVLX-Tet-On Advanced vector (Clontech, PT3990-5). Briefly, NEK9 lentiviral particles for each construct were harvested from transfected 293T packaging cells using the Lenti-X™ HTX Packaging System (Clontech), transduced into U2OS parental cells and selected in fresh medium supplemented with 2 mg/ml of G418 and 1 µg/ml puromycin over several days. To maintain expression of constructs, culture medium was supplemented with 1 μg/ml of G418 and 800 ng/ml of puromycin. For induction of constructs, doxycycline was added to growth medium at a final concentration of 1 µg/ml for 72 h, unless otherwise stated. Doxycycline-inducible HeLa:YFP–NEK7 cell lines were generated via co-transfection of parental HeLa cells that stably express the lacZ–Zeocin fusion gene and Tet repressor from pFRT/lacZeo and pcDNA6/TR plasmids (Invitrogen), respectively, with the appropriate pcDNA5/FRT/TO–YFP–NEK7 vector (Invitrogen) and the Flp recombinase expression vector, pOG44 (Invitrogen). After 48 h, cells were incubated in selective medium containing 200 µg/ml hygromycin B (Invitrogen) and resistant clones were selected and expanded. To maintain expression in stable cell lines, growth medium was supplemented with 200 µg/ml hygromycin B. For induction of NEK7 constructs, doxycycline was added at a final concentration of 1 µg/ml for 72 h unless otherwise stated. Constitutively expressing EML4 and EML4–ALK cell lines were generated by transfecting the relevant construct into U2OS cells. After 48 h, cells were incubated in selective medium containing 100 µg/ml hygromycin B. To maintain expression in stable cell lines, growth medium was supplemented with 100 µg/ml hygromycin B. Where indicated, cells were treated with 200 ng/ml nocodazole (Sigma), 20 nM vinorelbine (Sigma) or 100 nM Crizotinib (Selleck). Transient transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For flow cytometry, cells were fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol before DNA was labelled with 5 µg/ml propidium iodide. Analysis was performed using a FACSCanto II instrument and FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences).

Preparation of cell extracts, SDS–PAGE and western blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1% v/v Nonidet P-40, 0.1% w/v SDS, 0.5% w/v sodium deoxycholate, 5 mM NaF, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 30 µg/ml RNase, 30 µg/ml DNase I, 1× Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Expedeon), 1 mM PMSF] prior to analysis by SDS–PAGE and western blotting. Primary antibodies used were anti-GFP (0.2 µg/ml, cat# ab6556, Abcam), anti-α-tubulin (0.1 µg/ml, clone B512, cat# T5168, Sigma), anti-myc (1:1000, clone 9B11, cat# 2276, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-NEK9 (0.8 µg/ml, cat# sc-50765, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-EML4 (0.2 µg/ml, cat# A310-908A, Bethyl Laboratories), anti-FLAG (0.5 µm/ml, clone M2, cat# F3165, Sigma), anti-acetylated tubulin (0.5 µg/ml, clone 6-11 B-1, cat# T6793, Sigma), anti-ALK (1:2000, cat# 3633, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-pALK (1:1000, cat# 3341, Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-GAPDH (1 µg/ml, cat# 2118, Cell Signaling Technology). Secondary antibodies used were anti-rabbit, anti-mouse and anti-goat horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labelled IgGs (1:1000; cat# A6154, A4416 and A5420, respectively, Sigma). Western blots were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce).

RNAi

Cells at 30–40% confluency were cultured in Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Medium (Invitrogen) and transfected with 50 nM siRNA duplexes using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. At 72 h after transfection, cells were either fixed for immunocytochemistry or prepared for western blotting. siRNA oligos were directed against NEK9 [AM51334-1113 and -1115 silencer select duplexes (Ambion)] or EML4 [HSS120688 and HSS178451 On-Target Plus duplexes (Dharmacon)]. siRNA duplexes for NEK6 and NEK7 were as previously described (O'Regan and Fry, 2009).

Immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry

Cells were harvested by incubation with 1× PBS containing 0.5 mM EDTA, and pelleted by centrifugation (5 min at 500 g) prior to being lysed in NEB lysis buffer (Fry and Nigg, 1997). Lysates were immunoprecipitated using antibodies against NEK9 (0.8 µg/ml, cat# sc-50765, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), EML4 (0.4 µg/ml, cat# A310-908A, Bethyl Laboratories), myc (1:1000, clone 9B11 cat# 2276, Cell Signaling Technologies) or GFP (0.2 µg/ml, cat# ab6556, Abcam). Proteins that co-precipitated with myc–NEK9 were excised from gels and subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion prior to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using an RSLCnano HPLC system (Dionex, UK) and an LTQ-Orbitrap-Velos mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). The raw data file obtained from each LC-MS/MS acquisition was processed using Proteome Discoverer (version 1.4, Thermo Scientific), searching each file in turn using Mascot (version 2.2.04, Matrix Science Ltd.) against the human reference proteome downloaded from UniProtKB (Proteome ID: UP000005640). The peptide tolerance was set to 5 ppm and the MS/MS tolerance set to 0.6 Da. The output from Proteome Discoverer was further processed using Scaffold Q+S (version 4.0.5, Proteome Software). Upon import, the data was searched using X!Tandem (The Global Proteome Machine Organization). PeptideProphet and ProteinProphet (Institute for Systems Biology) probability thresholds of 95% were calculated from the decoy searches, and Scaffold was used to calculate an improved 95% peptide and protein probability threshold based on the two search algorithms.

Fixed-cell and time-lapse microscopy

Cells grown on acid-etched coverslips were fixed and permeabilized by incubation in ice-cold methanol at −20°C for a minimum of 20 min. Cells were blocked with PBS supplemented with 3% BSA and 0.2% Triton X-100 prior to incubation with the appropriate primary antibody diluted in PBS supplemented with 3% BSA and 0.2% Triton X-100. Primary antibodies used were against GFP (0.5 µg/ml, cat# ab6556, Abcam), α-tubulin (0.1 µg/ml, clone B512, cat# T5168, Sigma), myc (1:1000, clone 9B11, cat# 2276, Cell Signaling Technologies), FLAG (0.5 µg/ml, clone M2, cat# F3165, Sigma-Aldrich), NEK9 (0.8 µg/ml, cat# sc-50765, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and γ-tubulin (0.2 µg/ml, cat# T3559, Sigma). Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 488, 594 and 647 conjugated donkey anti-rabbit, donkey anti-mouse and donkey anti-goat IgGs (1 µg/ml; cat# A32790, A32744 and AS32849, respectively, Invitrogen). DNA was stained with 0.8 µg/ml Hoechst 33258. For actin visualization, cells were fixed using 3.7% formaldehyde and stained using phalloidin–TRITC (1:200; Sigma). Imaging was performed on a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope equipped with an inverted microscope (DMI6000 B, Leica) using a 63× oil objective (NA 1.4). Z stacks comprising 30–50 0.3 µm sections were acquired using LAS-AF software (Leica), and deconvolution of 3D image stacks was performed using Huygens software (Scientific Volume Imaging). For super-resolution radial fluctuations (SRRF) microscopy a VisiTech Infinity 3 confocal microscope fitted with a Hamamatsu C11440-22CU Flash 4.0 V2 sCMOS camera and a Plan Apo 100× objective (NA 1.47) was used. A total of 100 images from the same slice were captured per channel and processed using the nanoJ-SRRF plugin in Fiji (Culley et al., 2018; Gufstafsson et al., 2016). Immunohistochemistry with NEK9 antibodies (1:500, cat# ab138488, Abcam) was performed on samples from NSCLC patients with EML4–ALK fusions.

Phase-contrast and time-lapse microscopy was carried out using a Nikon eclipse Ti inverted microscope with either a Plan Fluor 10× DIC objective (NA 0.3) or a Plan Fluor 40× objective (NA 1.3). Images were captured using an Andor iXonEM+ EMCCD DU 885 camera and NIS elements software (Nikon). For time-lapse imaging, cells were cultured in 6-well dishes and maintained on the stage at 37°C in an atmosphere supplemented with 5% CO2 using a microscope temperature control system (Life Imaging Services) with images acquired every 15 min for ≥24 h. Videos were prepared using ImageJ (NIH, MD). Cell protrusions were measured using Fiji. The length of protrusion was defined as the distance from the edge of the nucleus of the cell to the furthest point of the plasma membrane. For each experiment 50 cells were measured per condition.

Individual cell tracking assays

To allow automated detection of individual cells for tracking analysis, cells were transfected with YFP alone and subjected to time-lapse imaging as appropriate. Individual cell tracking was then analysed using Imaris (BitPlane). Fluorescent cells were identified using the Imaris spots function and subsequently the Imaris TrackLineage algorithm was used to identify movements or tracks of these cells through the entire time period and thus provide numerical values for parameters such as speed and distance. For each experiment, 25 tracks were measured per condition.

Live-cell microtubule stability assays

For live-cell microtubule stability assays, cells were grown in µ-well 8-well chamber slides (Ibidi). Cells were incubated with 25 nM SiR-Tubulin (Cytoskeleton Inc.) for 4 h prior to imaging, A total of 10 images were captured prior to the addition of nocodazole, and a further 15 images were captured after drug was added. Z stacks comprising ∼10 sections of 0.5 µm were captured every 30 s for 7 min. Images were cropped to single cells and deconvolved prior to analysis in MATLAB (MathWorks). For each experiment, 10 cells were measured per treatment.

Cell migration assays

For scratch-wound assays, cells were grown to 95% confluency in 6-well dishes before a pipette tip was used to scrape a 0.5–1 µm line across the width of the well. Cells were washed 3–5 times in pre-warmed medium and either imaged by time-lapse microscopy or incubated at 37°C for 6 h before being processed for immunofluorescence microscopy. Cell migration in real time was analysed using the xCELLigence Real-Time Cell Analyzer (RTCA) DC equipment (AECA Biosciences) and CIM-16 plates, a 16-well system where each well is composed of upper and lower chambers separated by an 8 μm microporous membrane. Cells were grown in serum-free medium for 24 h before being seeded in serum-free medium into the upper chamber; complete medium containing 10% FBS was used as a chemoattractant in the lower chamber of the plate and migration determined as the relative impedance change (cell migration index) across microelectronic sensors integrated into the membrane, where: cell migration index = (impedance at time-point n/impedance in the absence of cells)/nominal impedance value. Measurements were taken every 15 min for 48 h.

3D spheroid invasion assays

Spheroids were grown in ultra-low attachment 96-well plates (Corning) for 24 h hours, before EML4–ALK expression was induced using 1 μg/ml doxycycline and siRNA was applied for a further 72 h. On day 5, Matrigel (Corning) was added to wells at 2.5 mg/ml and further induction and siRNA treatment applied. Spheroids were imaged at 0 h and 72 h after addition of Matrigel using a VisiTech infinity 3 confocal microscope fitted with Hamamatsu C11440-22CU Flash 4.0 V2 sCMOS camera and 10×/0.3 Pan Fluor DIC L/N objective. The resulting images were analysed using Fiji software. In total, ten invasive strands were measured per spheroid and six spheroids were measured per condition.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data represent means±s.d. of three independent experiments. Statistical analyses on data shown in histograms were performed using a one-tailed unpaired Student's t-test assuming unequal variance or a one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc testing for analysis of two data sets and multiple data sets, respectively. For RTCA cell migration data and microtubule stability assays, which generated line plots, the area under the curve was calculated for each data set and statistical analysis was performed on these data using either a one-tailed unpaired Student's t-test assuming unequal variance (two data sets) or a one-way ANOVA (more than two data sets). For patient data, statistical significance was calculated using χ2 tests. P-values represent *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001; ns, not significant.

Statement of ethics

All work involving patient samples was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center. All data were subject to an anonymizing program to retrieve patient lists, which removes patient hospital ID and assigns a new research ID to each patient.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Patrick Meraldi and his colleagues (University of Geneva) for introducing us to the kinetic SiR-tubulin microtubule depolymerization assay. We acknowledge the University of Leicester Core Biotechnology Services for support with cloning, mass spectrometry, DNA sequencing and microscopy.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: L.O'R., P.A.J.M., S.J.C., D.A.F., J.C., R.B., A.M.F.; Methodology: L.O'R., P.A.J.M., R.B., A.M.F.; Validation: L.O'R., A.M.F.; Formal analysis: L.O'R., G.B., R.A., C.G.W., H.J.J., E.L.R.; Investigation: L.O'R., G.B., R.A., C.G.W., H.J.J., E.L.R., M.W.R.; Resources: M.W.R., R.B., A.M.F.; Data curation: L.O'R.; Writing - original draft: L.O'R., A.M.F.; Writing - review & editing: P.A.J.M., S.J.C., D.A.F., J.C., R.B.; Visualization: L.O'R., G.B., R.A., C.G.W., H.J.J.; Supervision: L.O'R., A.M.F.; Project administration: L.O'R., R.B., A.M.F.; Funding acquisition: G.B., S.J.C., J.C., R.B., A.M.F.

Funding

This work was supported by grants to A.M.F. from Worldwide Cancer Research (13-0042 and 16-0119), Wellcome Trust (082828 and 097828) and Cancer Research UK (C1362/A180081); to R.B. from Cancer Research UK (C24461/A23302); to R.B. and J.C. from MRC-KHIDI, UK (Medical Research Council, MC_PC_17103) and MRC-KHIDI, Republic of Korea (Korea Health Industry Development Institute, HI17C1975); to S.J.C. from Cancer Research UK (Senior Cancer Research Fellowship A12102); and to G.B. from Weston Park Hospital Cancer Charity (Large Project Grant CA164). Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.241505.supplemental

Peer review history

The peer review history is available online at https://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.241505.reviewer-comments.pdf

References

- Adib R., Montgomery J. M., Atherton J., O'Regan L., Richards M. W., Straatman K. R., Roth D., Straube A., Bayliss R., Moores C. A. et al. (2019). Mitotic phosphorylation by NEK6 and NEK7 reduces the microtubule affinity of EML4 to promote chromosome congression. Sci. Signal. 12, 594 10.1126/scisignal.aaw2939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss R., Choi J., Fennell D. A., Fry A. M. and Richards M. W. (2016). Molecular mechanisms that underpin EML4-ALK driven cancers and their response to targeted drugs. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 1209-1224. 10.1007/s00018-015-2117-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belham C., Roig J., Caldwell J. A., Aoyama Y., Kemp B. E., Comb M. and Avruch J. (2003). A mitotic cascade of NIMA family kinases. Nercc1/Nek9 activates the Nek6 and Nek7 kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34897-34909. 10.1074/jbc.M303663200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S., Bhattacharya S., Socinski M. A. and Burns T. F. (2016). HSP90 inhibitors in lung cancer: promise still unfulfilled. Clin. Adv. Hematol. Oncol. 14, 346-356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Sasaki T., Tan X., Carretero J., Shimamura T., Li D., Xu C., Wang Y., Adelmant G. O., Capelletti M. et al. (2010). Inhibition of ALK, PI3K/MEK, and HSP90 in murine lung adenocarcinoma induced by EML4-ALK fusion oncogene. Cancer Res. 70, 9827-9836. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. L., Takeuchi K., Soda M., Inamura K., Togashi Y., Hatano S., Enomoto M., Hamada T., Haruta H., Watanabe H. et al. (2008). Identification of novel isoforms of the EML4-ALK transforming gene in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 68, 4971-4976. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. L., Soda M., Yamashita Y., Ueno T., Takashima J., Nakajima T., Yatabe Y., Takeuchi K., Hamada T., Haruta H. et al. (2010). EML4-ALK mutations in lung cancer that confer resistance to ALK inhibitors. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 1734-1739. 10.1056/NEJMoa1007478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos P., Endris V., Bozorgmehr F., Elsayed M., Kirchner M., Ristau J., Buchhalter I., Penzel R., Herth F. J., Heussel C. P. et al. (2018). EML4-ALK fusion variant V3 is a high-risk feature conferring accelerated metastatic spread, early treatment failure and worse overall survival in ALK(+) non-small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer 142, 2589-2598. 10.1002/ijc.31275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Aizer A., Shav-Tal Y., Yanai A. and Motro B. (2013). Nek7 kinase accelerates microtubule dynamic instability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833, 1104-1113. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal A. S., Shaw A. T., Sequist L. V., Friboulet L., Niederst M. J., Lockerman E. L., Frias R. L., Gainor J. F., Amzallag A., Greninger P. et al. (2014). Patient-derived models of acquired resistance can identify effective drug combinations for cancer. Science 346, 1480-1486. 10.1126/science.1254721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullati S. N., Kabeche L., Kettenbach A. N. and Gerber S. A. (2017). A bifurcated signaling cascade of NIMA-related kinases controls distinct kinesins in anaphase. J. Cell Biol. 216, 2339-2354. 10.1083/jcb.201512055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culley S., Tosheva K. L., Pereira P. M. and Henriques R. (2018). SRRF: Universal live-cell super-resolution microscopy. Int. J. Biochem. Cell B. 101, 74-79. 10.1016/j.biocel.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Keersmaecker K., Graux C., Odero M. D., Mentens N., Somers R., Maertens J., Wlodarska I., Vandenberghe P., Hagemeijer A., Marynen P. et al. (2005). Fusion of EML1 to ABL1 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with cryptic t(9;14)(q34;q32). Blood 105, 4849-4852. 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza E. E., Meirelles G. V., Godoy B. B., Perez A. M., Smetana J. H. C., Doxsey S. J., McComb M. E., Costello C. E., Whelan S. A. and Kobarg J. (2014). Characterization of the human Nek7 interactome suggests catalytic and regulatory properties distinct from those of Nek6. J. Proteome Res. 13, 4074-4090. 10.1021/pr500437x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebele R. C., Lu X., Sumey C., Maxson D. L. A., Weickhardt A. J., Oton A. B., Bunn P. A. Jr., Barón A. E., Franklin W. A., Aisner D. L. et al. (2012). Oncogene status predicts patterns of metastatic spread in treatment-naive nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer 118, 4502-4511. 10.1002/cncr.27409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing R. M., Chu P., Elisma F., Li H., Taylor P., Climie S., McBroom-Cerajewski L., Robinson M. D., O'Connor L., Li M. et al. (2007). Large-scale mapping of human protein-protein interactions by mass spectrometry. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3, 89 10.1038/msb4100134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freixo F., Martinez Delgado P., Manso Y., Sánchez-Huertas C., Lacasa C., Soriano E., Roig J. and Lüders J. (2018). NEK7 regulates dendrite morphogenesis in neurons via Eg5-dependent microtubule stabilization. Nat. Commun. 9, 2330 10.1038/s41467-018-04706-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry A. M. and Nigg E. A. (1997). Characterization of mammalian NIMA-related kinases. Methods Enzymol. 283, 270-282. 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)83022-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry A. M., O'Regan L., Sabir S. R. and Bayliss R. (2012). Cell cycle regulation by the NEK family of protein kinases. J. Cell Sci. 125, 4423-4433. 10.1242/jcs.111195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]