This cohort study assesses the association of hidradenitis suppurativa with comorbidities that precede the diagnosis or develop after the diagnosis in Danish patients.

Key Points

Question

What are the temporal associations of comorbidities with hidradenitis suppurativa diagnosis?

Findings

In this cohort study of 14 488 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from Denmark, inflammatory diseases, diabetes, depression, asthma, and reaction to severe stress, and adjustment disorders frequently preceded the diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa and may be associated with its development.

Meaning

The findings suggest that patients with newly diagnosed hidradenitis suppurativa may have a high frequency of type 1 diabetes and subsequent high risk of acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Abstract

Importance

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic skin disease characterized by recurrent inflamed nodular lesions and is associated with multiple comorbidities; previous studies have been of cross-sectional design, and the temporal association of HS with multiple comorbidities remains undetermined.

Objective

To evaluate and characterize disease trajectories in patients with HS using population-wide disease registry data.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective registry-based cohort study included the entire Danish population alive between January 1, 1994, and April 10, 2018 (7 191 519 unique individuals). Among these, 14 488 Danish inhabitants were diagnosed with HS or fulfilled diagnostic criteria identified through surgical procedure codes.

Exposures

Citizens of Denmark with a diagnosis code of HS as defined by International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) or as identified through surgical procedures.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Disease trajectories experienced more frequently by patients with HS than by the overall Danish population. Strength of associations between disease co-occurrences was evaluated using relative risk (RR). All significant disease pairs were tested for directionality using a binomial test, and pairs with directionality were merged into disease trajectories of 3 consecutive diseases. Numerous disease trajectories were combined into a disease progression network showing the most frequent disease paths over time for patients with HS.

Results

A total of 11 929 individuals were identified by ICD-10 diagnosis codes (8392 [70.3%] female; mean [SD] age, 37.72 [13.01] years), and 2791 were identified by procedural codes (1686 [60.4%] female; mean [SD] age, 37.38 [15.83]). The set of most common temporal disease trajectories included 25 diagnoses and had a characteristic appearance in which genitourinary, respiratory, or mental and behavioral disorders preceded the diagnosis of HS and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (604 cases [4.2%]; RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.55-1.59; P < .001), pneumonia (827 [5.7%]; RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.15-1.20; P < .001), and acute myocardial infarction (293 [2.0%]; RR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.35-1.39; P < .001) developed after the diagnosis.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings suggest that patients with newly diagnosed HS may have a high frequency of manifest type 1 diabetes and subsequent high risk of acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic skin disease of the pilosebaceous unit characterized by recurrent inflamed nodular lesions of the intertriginous skin areas. The lesions progress via abscess formation to scars and sinus tracts.1,2 HS is not an infectious disease; however, the lesions are commonly described as boils.3 This description is thought to contribute to a reporting bias. HS has an estimated population prevalence of 1% to 2%4,5 but appears to be underdiagnosed because approximately 90% of patients with symptoms qualifying for the HS diagnosis do not receive a diagnosis.5,6 The diagnosis is still poorly recognized and primary HS lesions are often misdiagnosed as staphylococcal abscesses.7 Treatment remains a clinical challenge despite recent advances and includes parallel medical treatment, surgical intervention, and supportive care.8

Globally, the typical patient with HS experiences a diagnostic delay of 7.2 years from first symptom to diagnosis.9 To fulfill the diagnostic criteria, one must experience at least 2 episodes of typical lesions (eg, nodules, abscesses, or sinus tracts) at a classic body site (axillae, groin, genitals, buttocks, perineal and perianal region, and inframammary and intermammary folds) within a 6-month period.10

In addition, HS has been associated with multiple comorbidities, such as metabolic syndrome, disorders of the lipoprotein metabolism, diabetes, obesity, smoking, depression, anxiety, and Crohn disease.11,12,13 Despite the associations, a temporal relationship and causality remain to be determined because most studies have had a cross-sectional design. The objective of this study was to assess and characterize disease trajectories in patients with HS using population-wide disease registry data.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This retrospective cohort study included patients in the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) who had received an International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnose code for HS (L73.2) during a 24.3-year period from 1994 to 2018. The control individuals were all other Danish residents who received any other diagnosis during the same week. The DNPR registry data were protected by the Danish Act on Processing of Personal Data and can only be accessed after application. This study was approved by the Danish Health Authority, Copenhagen. The study used national registry data. Informed consent was not obtained because data were anonymized.

Registries

Since 1968, all inhabitants in Denmark have been assigned a unique 10-digit Civil Personal Register (CPR) number that provides easy record-linkage on a personal level.14 The data used for this study (age, sex, encrypted CPR numbers [including parental CPR numbers], diagnoses, and procedures) were all taken from the CPR and from the DNPR, which covered all hospital encounters by individuals in the Danish population since its initiation in 1977. The subset started with the Danish incorporation of the ICD-10 codes in 1994 and the Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee classification system for surgical procedures in 1996.14 We performed our analysis based on the latest update of the registry. Since April 10, 2018, the registry has contained 7 191 519 unique individuals.

HS Proxy Group and Algorithm

Any individual who twice within a 6-month period underwent a surgical procedure for an abscess or similarly typical HS lesions in a classical body site per definition also qualified for the diagnosis of HS.10 We found 8 surgical procedural codes that could be linked to treatment of HS and divided them into 2 categories. Group 1 included likely procedural codes for HS (incision and drainage of abscess in mammary area, incision of pilonidal cyst, minor incision of soft tissue in pelvic area, incision of perianal abscess, and incision in vulva and perineum), and group 2 included procedural codes less likely to be for HS (incision of skin on the upper limb, incision of skin without further specification of localization, and insertion of surgical drain into the subcutaneous skin of the upper limb) (eTable 1 in the Supplement). We constructed an algorithm that screened for the relevant procedural code in DNPR and assigned the proxy diagnosis for HS to anyone who (during the 22.3-year timespan from 1996 to 2018 within any 6-month period) had either a minimum of 2 procedures from group 1 (method 1), 5 from group 2 (method 2), or 1 from group 1 plus 3 from group 2 (method 2). Individuals with the proxy diagnosis were assigned to the proxy group.

Assessment of Temporal Disease Trajectories

To assess common temporal disease trajectories, we applied a previously published method.15 Initially, all patients who received a diagnosis of primary or secondary HS (ICD-10 diagnosis code: L73.2) were identified. All combinations of disease co-occurrences in the population of patients with HS were tested to find diseases that co-occur more often than what would be expected based on their individual frequencies. The strength of the association between disease co-occurrences was evaluated using relative risk (RR) as follows:

|

where Cexposed is the number of patients with HS who had disease D1 and who subsequently had disease D2 (D1 and D2 identified as any 2 randomly picked diseases from thousands of permutations of the ICD-10 diagnosis codes). For each pair of diseases (D1 and D2), we identified 10 000 comparison groups with D1 matched to the patients with HS on birth decade, sex, type of hospital encounter, and discharge week. The occurrence of D2 within each of the comparison groups was calculated (C1 … CN) and evaluated how prevalent the occurrence of D1 and D2 were in the general population. To construct 95% CIs for the RRs, bootstrapping with 80% of the patients was calculated 20 times.

P values for each RR calculation were determined using a binomial distribution, and all significant disease pairs with an RR greater than 1 and P < .001 were tested for directionality using a binomial test. If significantly more patients had one disease before the other, the disease pair had a direction. P values for directionality testing were corrected using the Bonferroni correction. Disease pairs with a significant direction could be merged into longer disease trajectories of at least 3 consecutive diseases. A temporal disease trajectory occurred if the patient received diagnoses of at least 3 diseases in the order specified by the trajectory. We included disease trajectories for which there was a minimum of 100 ICD-10–defined cases (0.8%) and a minimum of 23 proxy-defined cases (0.8%). For the combined ICD-10 and proxy group, a minimum of 119 cases (0.8%) followed each trajectory. Numerous disease trajectories can be combined into a disease progression network showing how frequent disease paths were followed over time. This can be visualized in a figure in which all diseases that are part of the network are represented as orbs and the arrows connecting them represent the temporal manifestation, with the width of the arrow representing the number of patients following this temporal disease trajectory.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R, version 3.4.0 for Windows (R Project for Statistical Computing). We applied two 1-sided binomial tests; 1 to test if A shows up significantly more before B and 1 to test if B shows up significantly more after A. Statistical significance was considered as a Bonferroni corrected P < .05. For descriptive statistics, means (SDs) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) are provided.

Results

In the DNPR, 11 929 persons had received the ICD-10 diagnosis code of L73.2, and 55 843 individuals had a relevant HS surgical procedure performed during the study period (the distribution among procedural codes is given in eTable 1 in the Supplement). Among them, 5.0% (2791 of 55 843) fulfilled the criteria for the proxy diagnosis (99.8% through method 1) and 8.3% (232 of 2791) of those in the proxy group already had the L73.2 diagnosis code.

Descriptive data of the ICD-10 group is given in Table 1. The ICD-10 group (n = 11 929) was larger than the proxy group (n = 2791). They had a similar mean (SD) age at the time of diagnosis (ICD-10 group: 37.72 [13.01] years vs proxy group: 37.38 [15.83] years) and a similar percentage of familial cases (3.8% [455] vs 1.4% [39]). Both groups consisted primarily of females (ICD-10 group: 8392 [70.3%]; proxy group: 1686 [60.4%]). The ICD-10 group reported a longer follow-up time from the time of HS diagnosis (median, 10.36 years [IQR, 4.55-16.87 years] vs 5.80 years [IQR, 1.82-8.42 years]).

Table 1. Descriptive Data of the Groups From the Danish National Patient Registrya.

| Characteristic | ICD-10 group (n = 11 929) | Proxy group (n = 2791) | Combined (n = 14 488)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alive by first quarter of 2018, No. (% of total Danish population)c | 10 975 (0.19) | 2655 (0.05) | 13 410 (0.23) |

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD), y | 37.72 (13.01) | 37.38 (15.83) | 37.68 (13.61) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Male | 3537 (29.7) | 1105 (39.6) | 4587 (31.7) |

| Female | 8392 (70.3) | 1686 (60.4) | 9901 (68.3) |

| Type of HS, No. (%)d | |||

| Familial | 455 (3.8) | 39 (1.4) | 541 (3.7) |

| Spontaneous | 9176 (76.9) | 2118 (75.9) | 10 752 (74.2) |

| Parents Civil Personal Register not reported | 2298 (19.3) | 634 (22.7) | 3195 (22.0) |

| Follow-up from time of diagnosis, median (IQR), y | 10.36 (4.55-16.87) | 5.8 (1.82-8.42) | 8.76 (3.60-15.63) |

Abbreviations: HS, hidradenitis suppurativa; ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision; IQR, interquartile range.

Descriptive statistics for the ICD-10 group were identified through the HS ICD-10 diagnosis code in the Danish National Patient Registry; for the proxy group, through the algorithm on procedural codes.

From the total of 14 720 persons, 232 persons diagnosed with HS who were also identified through the algorithm were excluded, leaving a total of 14 488 unique persons.

Total Danish population of 5 781 190 according to Statistics Denmark. First quarter ended on March 31, 2018.

Familial type defined as patients with a first-degree relative with the HS ICD-10 code; spontaneous defined as patients without a first-degree relative with the HS ICD-10 code. In the combined group column, familial is defined as patients with first-degree relatives in either the ICD-10 group or the proxy group.

From the total of 14 720 persons, excluding 232 persons diagnosed with HS who were also identified through the algorithm, we identified 14 488 persons with either HS or the proxy diagnosis and combined them into 1 group (eTables 2-6 and eFigures 1-3 in the Supplement gives the full comparison). Of those, 13 410 persons were alive by April 10, 2018, which correlated with 0.23% (13 410 of 5 781 190) of the Danish population at the time.16

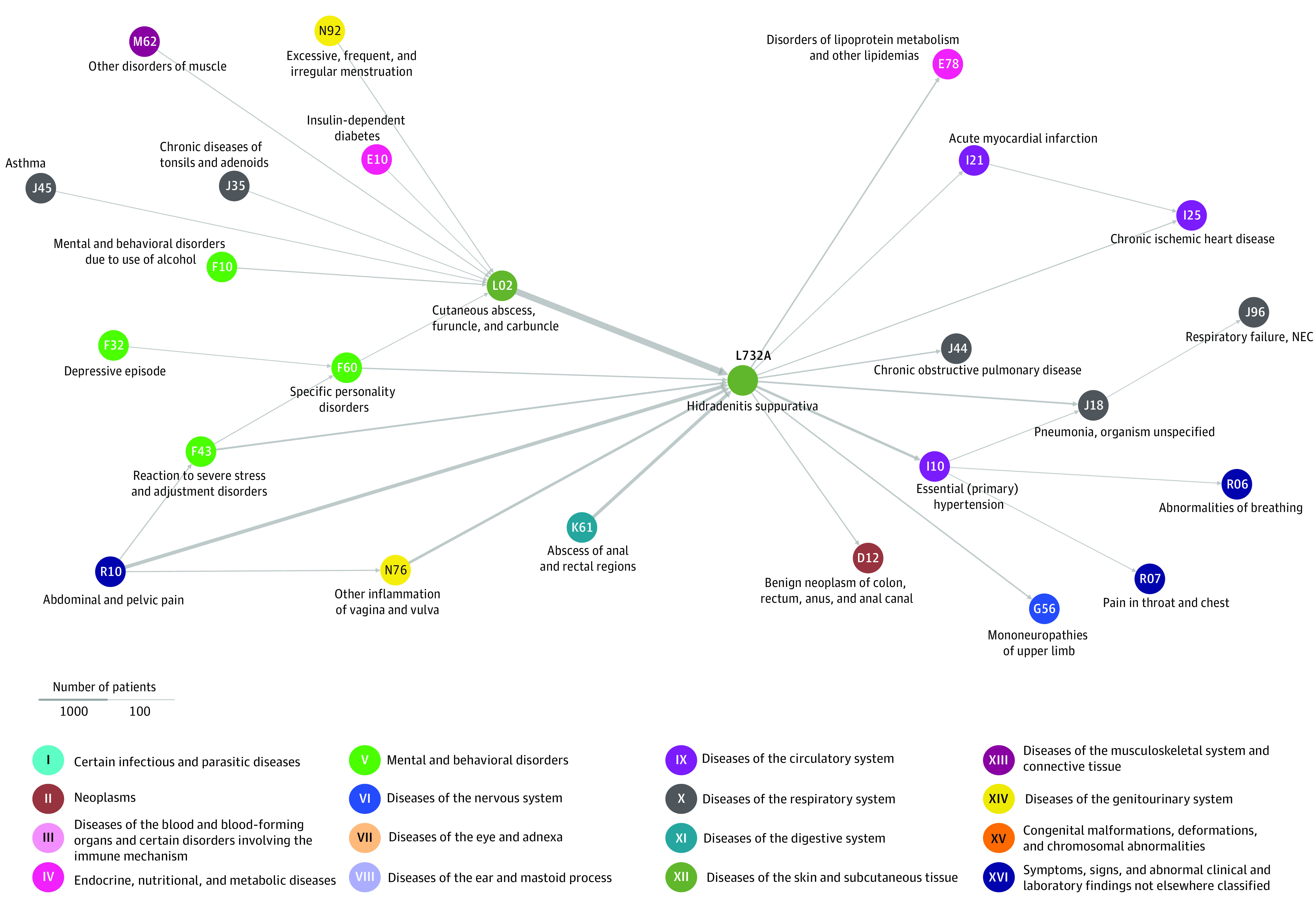

To reveal disease progression patterns that were more common among people with HS compared with a sex-matched and birth decade–matched control group selected from the Danish patient population, we identified all significant disease trajectories with 3 consecutive diagnoses. The Figure shows the trajectory network of the 14 488 unique individuals of the combined ICD-10 and proxy group and the 25 different diagnoses. There was a characteristic appearance in which various diagnoses, including depression, type 1 diabetes, asthma, and inflammatory diseases of vagina and vulva, preceded and primarily converged on cutaneous abscesses (L02), which progressed to HS (L732) before continuing to hypertension (1393 cases [9.6%]; RR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.35-1.37; P < .001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; J44) (604 [4.2%]; RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.55-1.59; P < .001), pneumonia (J18) (827 [5.7%]; RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.15-1.20; P < .001), acute myocardial infarction (AMI; I21) (293 [2.0%]; RR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.35-1.39; P < .001), and chronic ischemic heart disease (395 [2.7%]; RR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.21-1.24; P < .001). Diseases such as depression, diabetes, asthma, and inflammatory diseases of vagina and vulva converged on cutaneous abscesses before continuing to HS without a connection between diseases and HS.

Figure. Disease Trajectory Network of the Combined International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) and Proxy Groups for Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS).

The temporal associations of diseases experienced by patients with HS are shown. All diseases that are part of the trajectory network are represented as orbs with arrows connecting them representing the temporal manifestation. All trajectories (3 diseases linked left to right through arrows) include a minimum 119 patients with HS. This corresponds to a minimum of 0.8% of the total HS population. Increased arrow width indicates a higher number of patients following the trajectory.

The median time from HS diagnosis to other diagnoses more common for those with HS are listed in Table 2.; the median time for chronic ischemic heart disease was 4.44 years (IQR, −0.54 to 10.90), for acute myocardial infarctions was 4.9 years (IQR, 0-11.50 years), for COPD was 8.18 years (IQR, 2.37-14.44 years), and for pulmonary failure was 8.78 years (IQR, 2.27-13.87).

Table 2. Median Time From HS Diagnosis to Other Common Diagnoses in the HS Trajectory Networka.

| Diagnosis (ICD-10 code) | Time from HS diagnosis to disease diagnosis, median (IQR), y | Full list of ICD-10 subcodes within group |

|---|---|---|

| Mononeuropathies in upper limb (G56) | 3.73 (−2.24 to 10.16) | G56, G560, G561, G562, G562A, G563, G564, G568, G568A, G569 |

| Disorders of lipoprotein metabolism (E78) | 3.90 (−1.25 to 10.59) | E780, E780B, E780C, E781, E782, E782C, E784, E785, E788, E788B, E789 |

| Sleep disorders (G47) | 4.34 (−1.26 to 11.33) | G47, G470, G4703, G471, G4711, G4712, G4714, G4715, G472, G473, G4730, G4731, G4732, G4734, G4735, G4735C, G4735D, G474, G4741¸ G4742, G4744, G4752, G475B, G4761, G4762, G4763 |

| Pneumonia (J18) | 4.35 (−1.70 to 11.29) | J18, J180, J181, J182, J188, J189 |

| Chronic ischemic heart disease (I25) | 4.44 (−0.54 to 10.90) | I251, I252, I252A, I252B, I252C, I253, I255, I256, I258, I259 |

| Essential hypertension (I10) | 5.01 (−0.24 to 11.66) | I109 |

| Acute myocardial infarction (I21) | 4.79 (0 to 11.50) | I21, I210, I210A, I210B, I211, I211A, I211B, I212, I213, I214, I219 |

| Abnormalities of breathing (R06) | 5.80 (−0.90 to 12.84) | R06, R060, R060A, R0601, R062, R063, R064, R065, R065A, R066, R068, R068D |

| Benign neoplasm of colon, rectum, anus, and anal canal (D12) | 6.87 (0.46 to 13.84) | D120, D120A, D121, D122, D123, D124, D125, D126, D126A, D126B, D126C, D126F, D128, D129, D129A, D129B |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (J44) | 8.18 (2.37 to 14.44) | J440, J441, J448, J448A, J448B, J488C, J449 |

| Pain in throat and chest (R07) | 8.26 (1.56 to 14.54) | R07, R070, R071, R072, R073, R074 |

| Respiratory failure (J96) | 8.78 (2.27 to 13.87) | J960, J961, J969 |

Abbreviations: HS, hidradenitis suppurativa; ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision; IQR, interquartile range.

Median times from HS diagnosis to the other common diagnoses shown in the HS trajectory network in the Figure.

The individual networks of the ICD-10 group are shown in eFigure 1 in the Supplement and those of the proxy group are shown in eFigure 2 in the Supplement. The networks shared 66% to 85% of their linear trajectories, with the discrepancy primarily because of the lower detection limit in the proxy group (100 vs 23 cases). Further comparison is given in eTables 2 and 3 in the Supplement.

The patients in the ICD-10 group who died during the follow-up period were more likely to have received a diagnosis of AMI, COPD, or pneumonia compared with those who remained alive by the end of the study. Of all deaths among the patients with HS, 10.5% were preceded by a diagnosis of AMI (vs 4.7% of the surviving age-matched patients with HS), 23.6% by a diagnosis of COPD (vs 10.0% of the surviving age-matched patients with HS), and 33.5% by a diagnosis of pneumonia (vs 11.2% of the surviving age-matched patients with HS) (eTable 4 in the Supplement). The same analyses were conducted for the proxy group and yielded similar results (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Discussion

HS has been associated with multiple comorbidities11,12,13 but the underlying temporal associations have not been elucidated. The disease trajectories identified in this study suggest that diseases, such as depression, type 1 diabetes, asthma, and inflammatory diseases of vagina and vulva occurred before the diagnosis of HS, whereas hypertension, COPD, AMI, and chronic ischemic heart disease occurred after the diagnosis of HS. These data suggest that diabetes, depression, asthma, reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders, all inflammatory diseases,17,18,19,20 and alcohol intake (which also increases systemic inflammation)21 are associated with HS before diagnosis, whereas COPD, AMI, disorder of lipoprotein metabolism, and chronic ischemic heart disease develop in the time after HS diagnosis.

Our findings are generally consistent with the literature.11,12,22,23 Obesity, diabetes, smoking, disorder of the lipoprotein metabolism, and metabolic syndrome have previously been shown to be associated with HS, though the association with hypertension has not been found to be significant.11 These results match our findings, because hypertension was the last of the diagnoses associated with metabolic syndrome to occur among the patients with HS in our study. Of note, despite obesity not appearing on the trajectory, the reason was not because of a lack of association but because the timing of the diagnosis was so near the time of the HS diagnosis (eFigures 1-3 in the Supplement). Depression has been associated with HS, with psychological stress as the suggested reason.12 This information matched our finding in which reaction to severe stress (F43) appeared in the trajectory network. Overuse of alcohol has been shown to be increased among patients with HS,22 as has AMI, ischemic heart disease, and all-cause cardiac mortality,23 consistent with our findings. In areas where the current literature does not support our findings, it is not because of evidence of missing associations but because the possibility of an association having never been investigated to our knowledge. This was the case for asthma, COPD, pneumonia, and chronic tonsillitis. Our collective trajectory network did not include Crohn disease, for which an association has previously been found.13 This diagnosis, however, was part of the network for the proxy group (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). A possible explanation as to why this diagnosis was lacking from the trajectory network of the ICD-10 group could be the diagnostic delay experienced by patients with Crohn disease.24

The literature9 shows that patients may experience an average of 7.2 years delay before receiving a diagnosis of HS. With such a delay there may be uncertainties concerning the diagnoses preceding the HS diagnosis (ie, if the symptoms manifested before HS developed or before HS was diagnosed). However, most of the preceding diagnoses in the trajectories converged on cutaneous abscesses (L02) before arriving at HS (L732). Because the trajectories use the first time that the diagnosis was given, diseases such as diabetes, depression, reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders, and asthma may have preceded not only the diagnosis of HS but also the manifestation of symptoms as defined by the diagnosis of cutaneous abscesses (L02).

These findings suggest that physicians who treat patients with newly diagnosed HS should be aware of the higher frequency of type 1 diabetes and other inflammatory diseases. Furthermore, during subsequent care, physicians should note that patients with HS have a higher yearly risk of AMI, COPD, and pneumonia (eTable 6 in the Supplement) than their age- and sex-matched peers. Of note, after the HS diagnosis was made, the median time of serious subsequent diagnoses such as AMI and chronic ischemic heart disease was fewer than 5 years. In addition, we believe that procedure codes are a way of identifying patients with HS that could prove to be beneficial.

Large-scale temporal disease trajectories revealed from data on the municipality- or national-level may be an important resource in the future. They can help reveal associations that physicians, anesthesiologists, and surgeons need to be aware of regarding groups with higher risks of complications and/or development of comorbidities. This is especially true in psychiatry because psychiatric comorbidities are often underdiagnosed25,26 and because psychiatric patients receive lower-quality health care (eg, underdiagnoses and reduced access to tests and treatment) for both somatic26,27,28,29 and surgical challenges.28,30 Within all medical and surgical specialties, trajectories can help reveal information that could result in revision or creation of guidelines. Although ICD-10 codes would be able to capture somatic diseases, codes for surgical procedures would better elucidate any association with surgical procedure and/or the anesthesia necessary for most of a surgical procedure. Trajectories on surgical procedures can also help evaluate the association of diagnostic delay experienced within trajectories of solely ICD-10–based origin.

Limitations

A limitation of the study was that approximately 90% of people with HS symptoms did not receive a diagnosis.5,6 Patients with the most severe disease were likely diagnosed, and these individuals were more likely to experience comorbidities that would affect the RR of finding these comorbidities in the trajectories. However, because the diagnoses were all reported by the hospitals and not by general physicians, the same can be said of all the other diagnoses identified by ICD-10 diagnosis codes in this study. Another limitation to using trajectories as a way to show temporal associations was shown in our study by the diagnosis of obesity. Although obesity was associated with HS, the timing for the obesity diagnosis was approximately the same as for the diagnosis of HS. Although an association between HS and obesity was found, a significant disease trajectory between them was not.

Conclusions

The findings suggest patients with newly diagnosed HS may have a high frequency of manifest type 1 diabetes and subsequent high risk of acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

eTable 1. Procedural Codes Relevant for HS

eTable 2. How Common the Trajectories With Min 100 Patients (4.55%) Found Through ICD-10 Codes Alone, are Amongst Those Identified by the Procedure Codes Algorithm

eTable 3. How Common the Trajectories With Min 23 Patients (11.31%) Found Through the Procedure Code Algorithm, are Amongst Those Identified by ICD-10 Codes Alone

eTable 4. Differences in Diagnosis Received for the Deceased vs Those Alive in the ICD-10 Group by the End of the Study

eTable 5. Differences in Diagnosis Received for the Deceased vs Those Alive in the Proxy Group by the End of the Study

eTable 6. Disease Development and Yearly Rates in the Procedure Group Based on Follow-up Time and Matched With the ICD-10 Group

eFigure 1. Disease Trajectory Network Experienced by the HS Group Identified From the Danish National Patient Registry

eFigure 2. Disease Trajectory Network Experienced by the Proxy HS Group Identified Through the Algorithm

eFigure 3. ICD10 HS Group Where the Diagnosis of HS Were Artificially Delayed by 6 Months

References

- 1.Jemec GBE. Clinical practice. hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):158-164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1014163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zouboulis CC, Del Marmol V, Mrowietz U, Prens EP, Tzellos T, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: criteria for diagnosis, severity assessment, classification and disease evaluation. Dermatology. 2015;231(2):184-190. doi: 10.1159/000431175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa and immune dysregulation. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(2):237-238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10802.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ingram JR, Jenkins-Jones S, Knipe DW, Morgan CLI, Cannings-John R, Piguet V. Population-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink study using algorithm modelling to identify the true burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(4):917-924. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(4):774-781 doi: 10.1111/bjd.16998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos JV, Lisboa C, Lanna C, Costa-Pereira A, Freitas A. Is the prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa being overestimated in Europe? or is the disease underdiagnosed? evidence from a nationwide study across Portuguese public hospitals. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(12):1491-1492. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clerc H, Tavernier E, Giraudeau B, et al. Understanding the long diagnostic delay for hidradenitis suppurativa: a national survey among French general practitioners. Eur J Dermatol. Published online December 10, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saunte DML, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(20):2019-2032. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saunte DM, Boer J, Stratigos A, et al. Diagnostic delay in hidradenitis suppurativa is a global problem. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(6):1546-1549. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zouboulis CC, Desai N, Emtestam L, et al. European S1 guideline for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(4):619-644. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tzellos T, Zouboulis CC, Gulliver W, Cohen AD, Wolkenstein P, Jemec GBE. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(5):1142-1155. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shavit E, Dreiher J, Freud T, Halevy S, Vinker S, Cohen AD. Psychiatric comorbidities in 3207 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(2):371-376. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shalom G, Freud T, Ben Yakov G, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa and inflammatory bowel disease: a cross-sectional study of 3,207 patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(8):1716-1718. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449-490. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen AB, Moseley PL, Oprea TI, et al. Temporal disease trajectories condensed from population-wide registry data covering 6.2 million patients. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4022. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Statistics Denmark Folketal den 1. i kvartalet efter civilstand, alder, køn, område og tid. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.statistikbanken.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1920

- 17.Todd JA, Wicker LS. Genetic protection from the inflammatory disease type 1 diabetes in humans and animal models. Immunity. 2001;15(3):387-395. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00202-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berk M, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, et al. So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from? BMC Med. 2013;11:200. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu YZ, Wang YX, Jiang CL. Inflammation: the common pathway of stress-related diseases. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017;11:316. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canonica GW. Treating asthma as an inflammatory disease. Chest. 2006;130(1)(suppl):21S-28S. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1_suppl.21S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang HJ, Zakhari S, Jung MK. Alcohol, inflammation, and gut-liver-brain interactions in tissue damage and disease development. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(11):1304-1313. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i11.1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, Strunk A, Merson J. Opioid, alcohol, and cannabis misuse among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based analysis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3):495-500.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egeberg A, Gislason GH, Hansen PR. Risk of major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(4):429-434. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.6264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorrentino D. Preclinical and undiagnosed Crohn’s disease: the submerged iceberg. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(2):476-486. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uzun S, Kozumplik O, Topić R, Jakovljević M. Depressive disorders and comorbidity: somatic illness vs side effect. Psychiatr Danub. 2009;21(3):391-398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fugger G, Dold M, Bartova L, et al. Comorbid hypertension in patients with major depressive disorder—results from a European multicenter study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29(6):777-785. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2019.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park S-C, Kim J-M, Jun T-Y, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of insomnia in depressive disorders: the CRESCEND study. Psychiatry Investig. 2013;10(4):373-381. doi: 10.4306/pi.2013.10.4.373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reeves E, Henshall C, Hutchinson M, Jackson D. Safety of service users with severe mental illness receiving inpatient care on medical and surgical wards: a systematic review. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27(1):46-60. doi: 10.1111/inm.12426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mellesdal L, Kroken RA, Lutro O, et al. Self-harm induced somatic admission after discharge from psychiatric hospital—a prospective cohort study. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29(4):246-252. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Degos B, Daelman L, Huberfeld G, et al. Portosystemic shunts: an underdiagnosed but treatable cause of neurological and psychiatric disorders. J Neurol Sci. 2012;321(1-2):58-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.07.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Procedural Codes Relevant for HS

eTable 2. How Common the Trajectories With Min 100 Patients (4.55%) Found Through ICD-10 Codes Alone, are Amongst Those Identified by the Procedure Codes Algorithm

eTable 3. How Common the Trajectories With Min 23 Patients (11.31%) Found Through the Procedure Code Algorithm, are Amongst Those Identified by ICD-10 Codes Alone

eTable 4. Differences in Diagnosis Received for the Deceased vs Those Alive in the ICD-10 Group by the End of the Study

eTable 5. Differences in Diagnosis Received for the Deceased vs Those Alive in the Proxy Group by the End of the Study

eTable 6. Disease Development and Yearly Rates in the Procedure Group Based on Follow-up Time and Matched With the ICD-10 Group

eFigure 1. Disease Trajectory Network Experienced by the HS Group Identified From the Danish National Patient Registry

eFigure 2. Disease Trajectory Network Experienced by the Proxy HS Group Identified Through the Algorithm

eFigure 3. ICD10 HS Group Where the Diagnosis of HS Were Artificially Delayed by 6 Months