Abstract

Background:

The new coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS–CoV-2), has caused more than 210 000 deaths worldwide. However, little is known about the causes of death and the virus's pathologic features.

Objective:

To validate and compare clinical findings with data from medical autopsy, virtual autopsy, and virologic tests.

Design:

Prospective cohort study.

Setting:

Autopsies performed at a single academic medical center, as mandated by the German federal state of Hamburg for patients dying with a polymerase chain reaction–confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19.

Patients:

The first 12 consecutive COVID-19–positive deaths.

Measurements:

Complete autopsy, including postmortem computed tomography and histopathologic and virologic analysis, was performed. Clinical data and medical course were evaluated.

Results: Median patient age was 73 years (range, 52 to 87 years), 75% of patients were male, and death occurred in the hospital (n = 10) or outpatient sector (n = 2). Coronary heart disease and asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were the most common comorbid conditions (50% and 25%, respectively). Autopsy revealed deep venous thrombosis in 7 of 12 patients (58%) in whom venous thromboembolism was not suspected before death; pulmonary embolism was the direct cause of death in 4 patients. Postmortem computed tomography revealed reticular infiltration of the lungs with severe bilateral, dense consolidation, whereas histomorphologically diffuse alveolar damage was seen in 8 patients. In all patients, SARS–CoV-2 RNA was detected in the lung at high concentrations; viremia in 6 of 10 and 5 of 12 patients demonstrated high viral RNA titers in the liver, kidney, or heart.

Limitation:

Limited sample size.

Conclusion:

The high incidence of thromboembolic events suggests an important role of COVID-19–induced coagulopathy. Further studies are needed to investigate the molecular mechanism and overall clinical incidence of COVID-19–related death, as well as possible therapeutic interventions to reduce it.

Primary Funding Source:

University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf.

Little is known of the pathologic changes that lead to death in patients with COVID-19. This study reports the autopsy findings of consecutive patients who died with a diagnosis of COVID-19.

Since it was first detected in December 2019, the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS–CoV-2) spread from the central Chinese province of Hubei to almost every country in the world (1, 2). Most persons with COVID-19 have a mild disease course, but about 20% develop a more severe course with a high mortality rate (3). As of 26 April 2020, more than 2.9 million persons have been diagnosed with COVID-19 and 210 000 of them have died (4). Why the new coronavirus seems to have a much higher mortality rate than the seasonal flu is not completely understood. Some authors have reported potential risk factors for a more severe disease course, including elevated D-dimer levels, a high Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, and older age (5, 6). Because of the novelty of the pathogen, little is known about the causes of death in affected patients and its specific pathologic features. Despite modern diagnostic tests, autopsy is still of great importance and may be a key to understanding the biological characteristics of SARS–CoV-2 and the pathogenesis of the disease. Ideally, knowledge gained in this way can influence therapeutic strategies and ultimately reduce mortality. To our knowledge, only 3 case reports have been published about COVID-19 patients who have undergone complete autopsy (7, 8). Therefore, in this study we investigated the value of autopsy for determining the cause of death and describe the pathologic characteristics in patients who died of COVID-19.

Methods

Study Design

In response to the pandemic spread of SARS–CoV-2, the authorities of the German federal state of Hamburg ordered mandatory autopsies in all patients dying with a diagnosis of COVID-19 confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The legal basis for this was section 25(4) of the German Infection Protection Act. Because of legal regulations, no COVID-19 death was exempted from this order, even if its clinical cause seemed obvious. The case series demonstrated herein consists of 12 consecutive autopsies, starting with the first known SARS–CoV-2–positive death occurring in Hamburg (the second largest city in Germany, with 1.8 million inhabitants). All autopsies were performed at the Department of Legal Medicine of University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. The Ethics Committee of the Hamburg Chamber of Physicians was informed about the study (no. WF-051/20). The study was approved by the local clinical institutional review board and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. In all deceased patients, postmortem computed tomography (PMCT) and a complete autopsy, including histopathologic and virologic evaluation, were performed. Clinical records were checked for preexisting medical conditions and medications, current medical course, and antemortem diagnostic findings.

PMCT, Autopsy, and Histologic Examination

Computed tomographic examination was done at the Department of Legal Medicine with a Philips Brilliance 16-slice multidetector scanner in accordance with an established protocol (9). In brief, full-body computed tomography was performed from top to thigh (slice thickness, 1 mm; pitch, 1.5; 120 kV; 230 to 250 mAs), complemented by dedicated scans of the thorax with higher resolution (slice thickness, 0.8 mm; pitch, 1.0; 120 kV; 230 to 250 mAS). We performed external examinations and full-body autopsies on all deceased persons with SARS–CoV-2 positivity (PCR confirmed) as soon as possible after taking proper safety precautions (using personal protection equipment with proper donning and doffing), following guidelines from the German Association of Pathologists, which are closely aligned with relevant international guidelines. The recently published recommendations for the performance of autopsies in cases of suspected COVID-19 were taken into account (10). The interval from death to postmortem imaging and autopsy (postmortem interval) ranged from 1 to 5 days. During autopsy, tissue samples for histology were taken from the following organs: heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, spleen, pancreas, brain, prostate and testes (in males), ovaries (in females), small bowel, saphenous vein, common carotid artery, pharynx, and muscle.

For virologic testing, we took small samples of heart, lungs, liver, kidney, saphenous vein, and pharynx and sampled the venous blood.

Tissue samples for histopathologic examination were fixed in buffered 4% formaldehyde and processed via standard procedure to slides stained with hematoxylin–eosin. For the lung samples, we also used the keratin marker AE1/AE3 (Dako) for immunohistochemistry.

Quantitative SARS–CoV-2 RNA Reverse Transcription PCR From Tissue

Tissue samples were ground by using ceramic beads (Precellys lysing kit) and extracted by using automated nucleic acid extraction (MagNA Pure 96 [Roche]) according to manufacturer recommendations. For virus quantification in tissues, a previously published assay was adopted with modifications (11). One-step real-time PCR was run on the LightCycler 480 system (Roche) by using a 1-step RNA control kit (Roche) as master mix. The Ct (cycle threshold) value for the target SARS–CoV-2 RNA (fluorescein) and whole-process RNA control (Cy5) was determined by using the second derivative maximum method. For quantification, standard in vitro–transcribed RNA of the E gene of SARS–CoV-2 was used (12). These samples were also analyzed in a study focusing on renal tropism of SARS–CoV-2 (Puelles V, et al. Multi-organ and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. In preparation).

Statistical Analysis

Data that were normally distributed are presented as means (SDs); data outside the normal distribution are presented as medians (ranges). Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. All data were analyzed with Statistica, version 13 (StatSoft).

Role of the Funding Source

The sponsor was not involved in the design or conduct of the study, nor in the analysis of the data or the decision to submit the manuscript.

Results

Clinical Data

The median age of the 12 patients included in this study was 73 years (interquartile range, 18.5); 25% were women. For all patients, preexisting chronic medical conditions, such as obesity, coronary heart disease, asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral artery disease, diabetes mellitus type 2, and neurodegenerative diseases, could be identified (Table 1). Two patients died out of the hospital after unsuccessful cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 5 died after treatment in the intensive care unit, and the remaining 5 had an advanced directive for best supportive care and died in the non–intensive care ward. Laboratory results for clinical chemistry, hematology, and coagulation were not available for the patients who died out of the hospital. In the remaining patients, the most striking features of the initial laboratory test were elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase (median, 7.83 µkat/L [range, 2.71 to 11.42 µkat/L]), D-dimer (available for 5 patients; median, 495.24 nmol/L [range, 20.38 to >1904.76 nmol/L]), and C-reactive protein (median, 189 mg/L [range, 18 to 348 mg/L]), as well as mild thrombocytopenia in 4 of 10 patients. A procalcitonin test had been performed in 6 patients, and the results were negative in all but 1 patient with pneumonia (case 10). Table 2 provides an overview of the initial laboratory results.

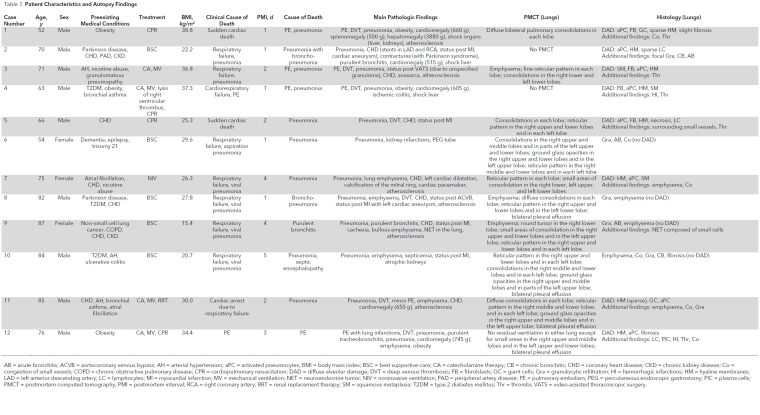

Table 1. Patient Characteristics and Autopsy Findings.

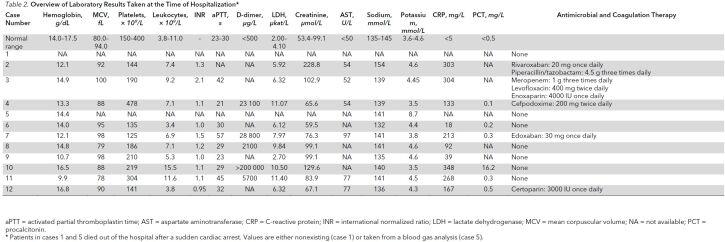

Table 2. Overview of Laboratory Results Taken at the Time of Hospitalization*.

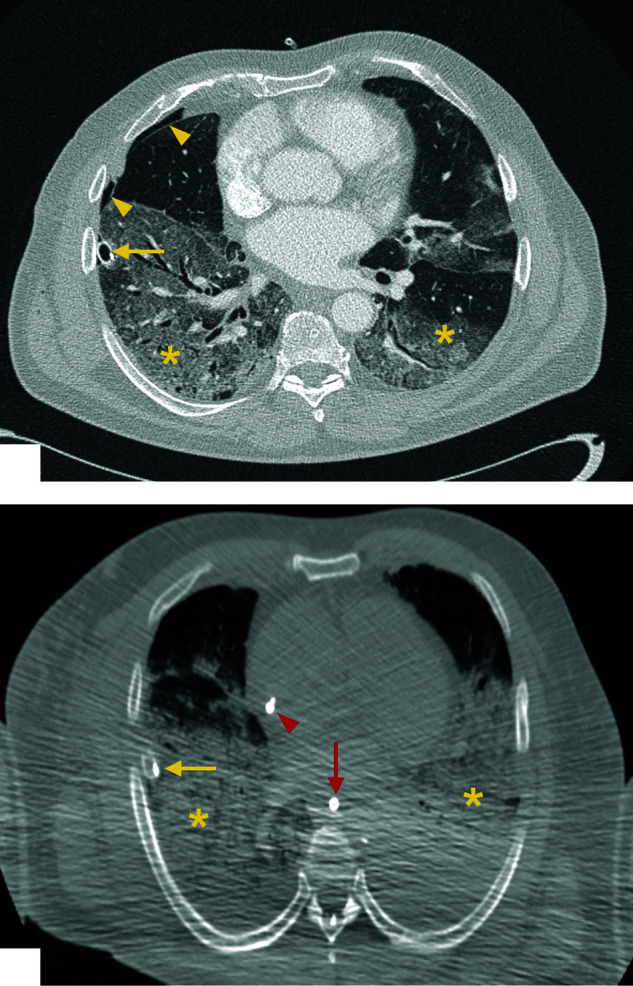

PMCT

In 2 cases (2 and 4), PMCT was not possible for logistic reasons. In the remaining cases, PMCT demonstrated mixed patterns of reticular infiltrations and severe, dense, consolidating infiltrates in both lungs in the absence of known preexisting pathology (such as emphysema or tumor). A juxtaposition of antemortem and postmortem findings is demonstrated in Figure 1. A complete summary of PMCT findings is presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Antemortem versus postmortem computed tomographic imaging (case 3).

Top. Contrast medium–enhanced computed tomography scan demonstrates the antemortem findings: bilateral ground glass opacities in the lower lobes of both lungs (yellow asterisks) and a chest tube (yellow arrow), which has been introduced to treat a pneumothorax (yellow arrowheads). Bottom. Computed tomography scan without contrast medium enhancement demonstrates the corresponding postmortem findings. For technical reasons, the postmortem image has a lower resolution. To protect the staff from potential infection, bodies were scanned in a double-layer body bag with the arms positioned alongside the body. Although the findings correspond to the antemortem images, ground glass opacities in both lower lobes (yellow asterisks) and a chest tube (yellow arrow) are seen. In addition, a central venous line (red arrowhead) and gastric tube (red arrow) are visible.

Autopsy

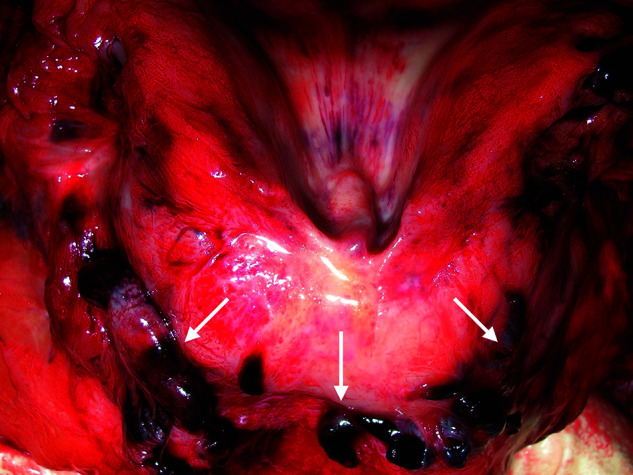

In 4 cases (1, 3, 4, and 12), massive pulmonary embolism was the cause of death, with the thrombi deriving from the deep veins of the lower extremities. In another 3 cases (5, 8, and 11), fresh deep venous thrombosis was present in the absence of pulmonary embolism. In all cases with deep venous thrombosis, both legs were involved (Figure 2). In 6 of the 9 men (two thirds) included in the study, fresh thrombosis was also present in the prostatic venous plexus (Appendix Figure 1, available at Annals.org).

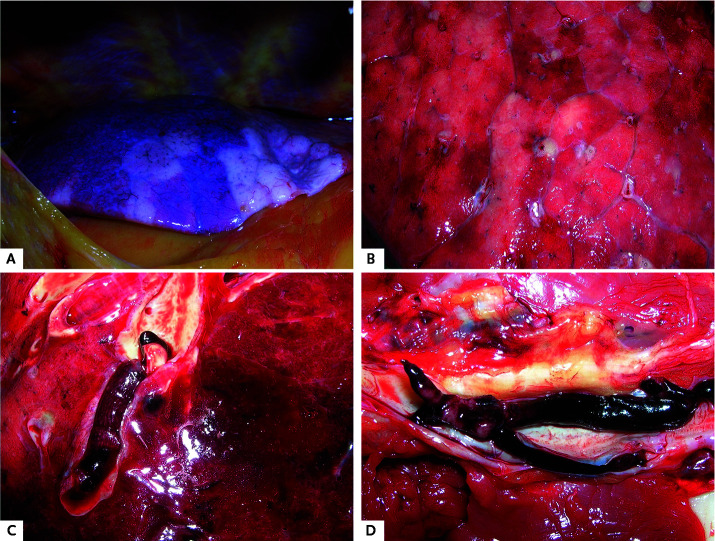

Figure 2.

Macroscopic autopsy findings.

A. Patchy aspect of the lung surface (case 1). B. Cutting surface of the lung in case 4. C. Pulmonary embolism (case 3). D. Deep venous thrombosis (case 5).

Appendix Figure 1.

Thrombosis of the prostatic vein (case 1) (arrows).

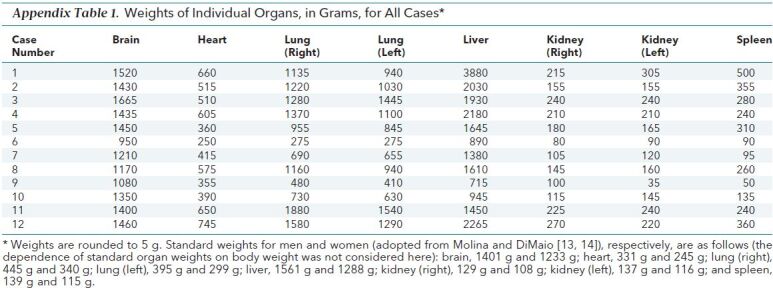

In all 12 cases, the cause of death was found within the lungs or the pulmonary vascular system. However, macroscopically differentiating viral pneumonia with subsequent diffuse alveolar damage (a histologic diagnosis) from bacterial pneumonia was not always possible. Typically, the lungs were congested and heavy, with a maximum combined lung weight of 3420 g in case 11. The mean combined lung weight was 1988 g (median, 2088 g). Standard lung weights for men and women are 840 g and 639 g, respectively (13, 14). Only cases 6 and 9 presented with a relatively low lung weight: 550 g and 890 g, respectively (Appendix Table 1, available at Annals.org). The lung surface often displayed mild pleurisy and a distinct patchy pattern, with pale areas alternating with slightly protruding and firm, deep reddish blue hypercapillarized areas. On the cutting surfaces, this pattern was also visible (Figure 2). The consistency of the lung tissue was firm yet friable. In 8 cases, all parts of the lungs were affected by these changes. Cases 6, 7, and 9—occurring in the 3 women of the case series—presented with changes compatible with focal purulent bronchopneumonia. Macroscopically, no changes were observed outside the lungs and respiratory tract, except for splenomegaly in 3 cases, which suggested a viral infection.

Appendix Table 1. Weights of Individual Organs, in Grams, for All Cases*.

During autopsy, all cases except for case 6 presented with preexisting heart disease, including high-grade coronary artery sclerosis (7 of 12); myocardial scarring, indicating ischemic heart disease (6 of 12); and congestive cardiomyopathy. Mean heart weight was 503 g (median, 513 g). In addition to this finding, the most common accompanying diseases were pulmonary emphysema (6 of 12) and ischemic enteritis (3 of 12). Often these conditions were known to the treating physician before death (compare columns 4 and 10 of Table 1). The macroscopic autopsy findings are presented organ by organ in Appendix Table 2 (available at Annals.org) and the lung findings in Table 1.

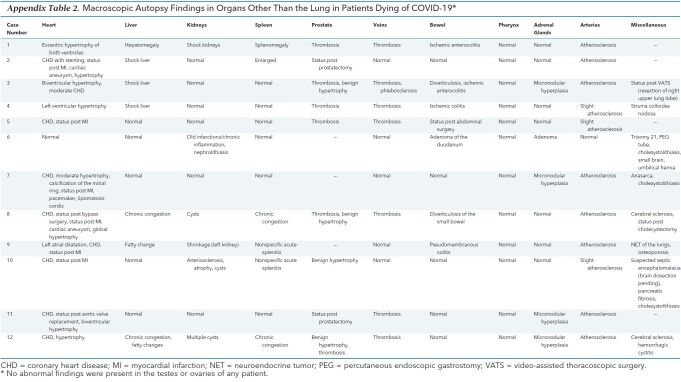

Appendix Table 2. Macroscopic Autopsy Findings in Organs Other Than the Lung in Patients Dying of COVID-19*.

A clear trend toward obesity was observed among the cases (mean body mass index, 28.7 kg/m2; median, 28.7 kg/m2). However case 9, involving a patient with known neuroendocrine tumor of the lung, presented with severe cachexia (body mass index, 15.4 kg/m2). The comorbid conditions found are summarized in Table 1.

Histology

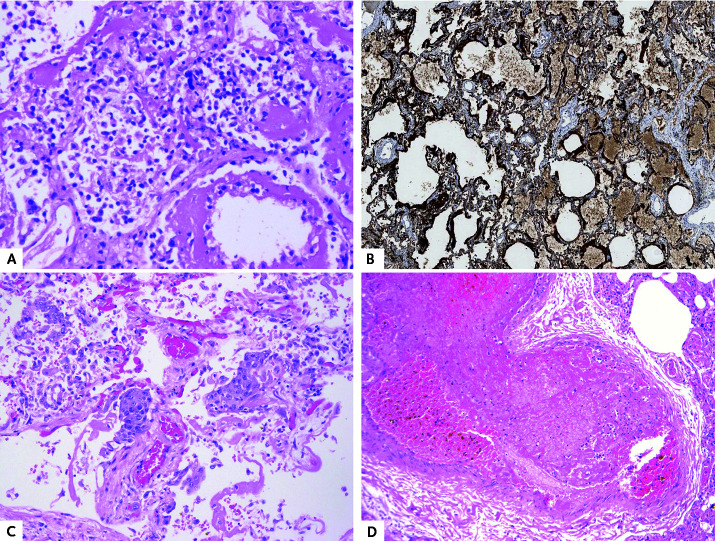

Histopathology of the lungs showed diffuse alveolar damage, consistent with early acute respiratory distress syndrome in 8 cases. Predominant findings were hyaline membranes (Figure 3, A and B), activated pneumocytes, microvascular thromboemboli, capillary congestion, and protein-enriched interstitial edema. As described by Wang and colleagues (15), a moderate degree of inflammatory infiltrates concurred with clinically described leukopenia in patients with COVID-19 and predominant infiltration of lymphocytes fit the picture of a viral pathogenesis. In later stages, squamous metaplasia was present (Figure 3, C). Long-term changes, such as destruction of alveolar septae and lymphocytic infiltration of the bronchi, were often visible as preexisting conditions. Four cases (6, 8, 9, and 10) showed no diffuse alveolar damage but extensive granulocytic infiltration of the alveoli and bronchi, resembling bacterial focal bronchopneumonia. Histologically, thromboemboli were detectable in cases 1, 3, 4, and 5 (Figure 3, D). Microthrombi were regularly found within small lung arteries, occasionally within the prostate, but not in other organs.

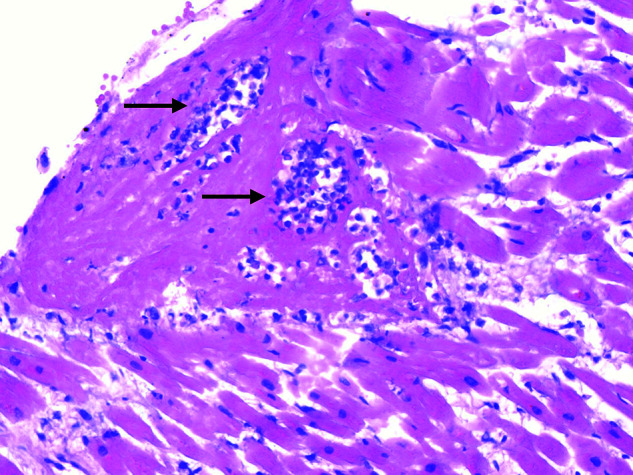

Figure 3.

Histopathologic findings.

A. Diffuse alveolar damage with hyaline membranes (case 4) (hematoxylin–eosin [H&E] stain; original magnification,×50). B. Hyaline membranes (case 4) (cytokeratin AE1/AE3 stain, original magnification×50). C. Squamous metaplasia in the lung (case 5) (H&E stain; original magnification,×100). D. Pulmonary embolism (case 1) (H&E stain; original magnification,×100).

In addition to the lung changes described in Table 1, there were isolated histologic findings that might indicate a viral infection. The pharyngeal mucosa was examined in 7 cases. In 6 of them, hyperemia and alternating dense, predominantly lymphocytic infiltrates were found as signs of chronic pharyngitis. In 1 case (case 3), lymphocytic myocarditis was seen in the right ventricle (Appendix Figure 2, available at Annals.org). The remaining histologic changes were compatible with shock changes in part of the deceased patient (liver, kidneys, intestine) or corresponded to the macroscopically determined virus-independent preexisting pathology (such as ischemic cardiomyopathy).

Appendix Figure 2.

Mononuclear infiltrations consisting of lymphocytes (arrows) in the myocardium of the right ventricle (case 3) (hematoxylin–eosin stain; original magnification,×100).

Apart from findings related to SARS–CoV-2 infection, patients showed other histopathologic findings related to their chronic preexisting conditions, including hypertrophy of myocardial fibers or scarring of the myocardium. The peripheral veins, including those occluded by thrombi, showed no abnormalities on hematoxylin–eosin staining.

PCR Results

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR detected SARS–CoV-2 RNA in the lungs of all 12 patients (range, 1.2×104 to 9×109 copies/mL) and in the pharynx of 9 patients. Six patients showed moderate viremia (<4×104 copies/mL). In 5 of these patients, viral RNA was also detected in other tissues (heart, liver, or kidney) in concentrations exceeding viremia. Patients without viremia showed no or a low virus load in the other tissues. Only 4 patients had detectable viral RNA in the brain and saphenous vein.

Discussion

In this autopsy study of 12 consecutive patients who died of COVID-19, we found a high incidence of deep venous thrombosis (58%). One third of the patients had a pulmonary embolism as the direct cause of death. Furthermore, diffuse alveolar damage was demonstrated by histology in 8 patients (67%).

To our knowledge, this is the first case series summarizing and comparing clinical data of consecutive COVID-19 cases with findings obtained by a full autopsy, supplemented by PMCT, histology, and virology.

The high rate of death-causing pulmonary embolism at autopsy correlates well with the unsuccessful resuscitation of 3 of 4 patients, 2 of whom died out of the hospital. Apart from that, no preclinical evidence had been reported of pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis.

In studies that examined deceased patients with COVID-19 without relying on autopsy, no increased rates of pulmonary embolism were observed clinically. However, it is known that many cases of pulmonary embolism remain clinically overlooked and are often associated with sudden, unexpected death. This may have been aggravated by the method for diagnosing COVID-19 in Germany, which is based on PCR tests rather than computed tomographic imaging because of concerns about infection of medical staff and other patients. A recent report described clinical features of 85 fatal cases of COVID-19 from Wuhan (16). Besides respiratory failure, the cause of death was multiorgan failure in 16% and cardiac arrest in 9%. No autopsies were performed. The gold standard for identifying cause of death is still the autopsy (17). However, in-hospital autopsy rates have declined worldwide over the past decades. Also, because of pathologists' potential risk for SARS–CoV-2 infection, very few autopsies have been performed worldwide (18). To our knowledge, only 3 case reports have been published on patients with COVID-19 who have undergone complete autopsy and a few more in which only lung tissue was examined (7, 8).

Other researchers have described coagulopathy as a common complication in patients with severe COVID-19 (5, 6, 19). In a recent study of 191 patients with COVID-19, 50% of those who died had coagulopathy, compared with 7% of survivors. D-dimer levels greater than 1000 µg/L were associated with a fatal outcome (6).

COVID-19 may predispose to venous thromboembolism in several ways. The coagulation system may be activated by many different viruses, including HIV, dengue virus, and Ebola virus (20, 21). In particular, coronavirus infections may be a trigger for venous thromboembolism, and several pathogenetic mechanisms are involved, including endothelial dysfunction, characterized by increased levels of von Willebrand factor; systemic inflammation, by Toll-like receptor activation; and a procoagulatory state, by tissue factor pathway activation (22). In a subgroup of patients with severe COVID-19, high plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines were observed (23). The direct activation of the coagulation cascade by a cytokine storm is conceivable. With COVID-19, severe hypoxemia develops in some patients (24). Thrombus formation under hypoxic conditions is facilitated both in animal models of thrombosis and in humans. The vascular response to hypoxia is controlled primarily by the hypoxia-inducible transcription factors, whose target genes include several factors that regulate thrombus formation (25). Lastly, indirect causes, such as immune-mediated damage by antiphospholipid antibodies, may partially contribute, as speculated by Zhang and colleagues (26).

The macroscopic findings in our autopsy series—with rather heavy, consolidated, friable, basically air-free lungs in most of the cases—were impressive and explain the difficulties in sufficiently ventilating some of these patients. The histopathologic changes in most of our cases with diffuse alveolar damage as the main finding resemble those described by Xu and colleagues (7) and Barton and colleagues (8), who reported single cases; Zhang and colleagues (26), who reported on lung biopsy in a patient with SARS–CoV-2 positivity; and Tian and colleagues (27), who described macroscopic and histologic pulmonary findings in 2 patients with lung cancer who received positive results on SARS–CoV-2 testing. However, the full-blown picture of diffuse alveolar damage seems to be more prevalent in younger patients with fewer preexisting diseases and longer survival, whereas older patients with more comorbid conditions tend to die in the early stages of the disease.

In line with clinical, macroscopic, and histopathologic findings, PCR detected the highest concentration of SARS–CoV-2 RNA in lung and pharyngeal tissue. Of interest, in most patients with disease, high titers of RNA were also detected in postmortem samples. The clinical relevance of this is not yet clear. Clearance of viral RNA from blood 7 days after transfusion of COVID-19 convalescent plasma was associated with substantial clinical improvement, but studies have not shown a correlation between viremia and acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients with severe COVID-19 (28, 29). As in patients with SARS–CoV-1, in whom viral replication could be detected in other organs, including the liver, kidney, spleen, and cerebrum (30), we detected viral RNA at high titers in other organs (liver, kidney, and heart) in 5 patients. These data suggest that SARS–CoV-2 may spread via the bloodstream and infect other organs. To prove this, replication intermediates must be detected.

The current study had some limitations: First, the sample size was small, possibly leading to overestimation of the rate of pulmonary embolism. However, both the clinical and postmortem observations agree well with the current knowledge about SARS–CoV-2 pathology. This includes the sex and age distribution as well as the preexisting conditions among the patients, but also the histologic findings. Second, although viral titers in swabs (pharynx) taken longitudinally up to 7 days after death remained similar, we lack data on how postmortem processes affect viral titers and dynamics in different tissues and body fluids. Moreover, the quantitative PCR assay used cannot discriminate between genomic and subgenomic RNA. As stated earlier, to prove viral replication, detection of replication intermediates or antigenomic RNA would be necessary.

In conclusion, we found a high incidence of thromboembolic events in patients with COVID-19. When hemodynamic deterioration occurs in a patient with COVID-19, pulmonary embolism should always be suspected. That patients with COVID-19 who have increased D-dimer levels, a sign of coagulopathy, may benefit from anticoagulant treatment seems plausible (31). As demonstrated in our cohort, this might be important for hospitalized patients and outpatients. In this context, some professional societies have already made recommendations for antithrombotic therapy for patients with COVID-19 (32). Robust evidence, however, remains scant, and further prospective studies are urgently needed to confirm and validate these results.

Biography

Financial Support: Institutional Funds of University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Disclosures: Dr. Nierhaus reports grants and personal fees from CytoSorbents Europe and personal fees from Thermo Fisher Scientific and Biotest outside the submitted work. Dr. Frings reports personal fees from Xenios outside the submitted work. Dr. Bokemeyer reports personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis, Merck KgaA, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Lilly ImClone, Bayer, GSO Contract Research, AOK Rheinland/Hamburg, and Novartis outside the submitted work. Dr. Kluge reports grants from Ambu, E.T. View, Fisher & Paykel, Pfizer, and Xenios and personal fees from Amomed, ArjoHuntleigh, Astellas, Astra, Basilea, Bard, Bayer, Baxter, Biotest, CSL Behring, CytoSorbents, Fresenius, Gilead, MSD, Orion, Pfizer, Philips, Sedana, Sorin, Xenios, and Zoll outside the submitted work. Authors not named here have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Disclosures can also be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M20-2003.

Editors' Disclosures: Christine Laine, MD, MPH, Editor in Chief, reports that her spouse has stock options/holdings with Targeted Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Darren B. Taichman, MD, PhD, Executive Editor, reports that he has no financial relationships or interests to disclose. Cynthia D. Mulrow, MD, MSc, Senior Deputy Editor, reports that she has no relationships or interests to disclose. Eliseo Guallar, MD, MPH, DrPH, Deputy Editor, Statistics, reports that he has no financial relationships or interests to disclose. Jaya K. Rao, MD, MHS, Deputy Editor, reports that she has stock holdings/options in Eli Lilly and Pfizer. Christina C. Wee, MD, MPH, Deputy Editor, reports employment with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Sankey V. Williams, MD, Deputy Editor, reports that he has no financial relationships or interests to disclose. Yu-Xiao Yang, MD, MSCE, Deputy Editor, reports that he has no financial relationships or interest to disclose.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol: Available with approval through written agreement with Dr. Wichmann (e-mail, d.wichmann@uke.de). Statistical code: Available from Dr. Kluge (e-mail, s.kluge@uke.de). Data set: Not available.

Corresponding Author: Dominic Wichmann, MD, Department of Intensive Care Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistr. 52, 20246 Hamburg, Germany; e-mail, d.wichmann@uke.de.

Current Author Addresses: Drs. Wichmann, Burdelski, de Heer, Nierhaus, Frings, and Kluge: Department of Intensive Care Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistr. 52, 20246 Hamburg, Germany.

Drs. Sperhake, Edler, Heinemann, Heinrich, Mushumba, Kniep, Schröder, and Püschel: Department of Legal Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistr. 52, 20246 Hamburg, Germany.

Drs. Lütgehetmann, Pfefferle, and Aepfelbacher: Institute of Medical Microbiology Virology and Hygiene, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistr. 52, 20246 Hamburg, Germany.

Dr. Steurer: Department of Pathology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistr. 52, 20246 Hamburg, Germany.

Dr. Becker: Department of Pulmonology and Internal Intensive Care, Asklepios Hospital Barmbek, Rübenkamp 220, 22307 Hamburg, Germany.

Dr. Bredereke-Wiedling: Emergency Department, Bethesda Hospital Bergedorf, Glindersweg 80, 21029 Hamburg, Germany.

Dr. de Weerth: Department of Internal Medicine, Agaplesion Diakonie Hospital, Hohe Weide 17, 20259 Hamburg, Germany.

Dr. Paschen: Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Amalie Sieveking Hospital, Haselkamp 33, 22359 Hamburg, Germany.

Dr. Sheikhzadeh-Eggers: Emergency Department, Asklepios Hospital Saint Georg, Lohmühlenstrasse 5, 20099 Hamburg, Germany.

Dr. Stang: Department of Oncology, Asklepios Hospital Barmbek, Rübenkamp 220, 22307 Hamburg, Germany.

Drs. Schmiedel and Addo: Sections of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistr. 52, 20246 Hamburg, Germany.

Dr. Bokemeyer: Department of Hematology and Oncology, Section of Pneumology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistr. 52, 20246 Hamburg, Germany.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: D. Wichmann, J.P. Sperhake, F. Heinrich, S. Kluge.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: D. Wichmann, J.P. Sperhake, M. Lütgehetmann, S. Steurer, F. Heinrich, H. Mushumba, I. Kniep, A.S. Schröder, A. de Weerth, C. Bokemeyer, M.M. Addo, M. Aepfelbacher, S. Kluge.

Drafting of the article: D. Wichmann, J.P. Sperhake, M. Lütgehetmann, I. Kniep, S. Kluge.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: D. Wichmann, J.P. Sperhake, I. Kniep, C. Burdelski, G. de Heer, A. Nierhaus, A. de Weerth, A. Stang, S. Schmiedel, M.M. Addo, M. Aepfelbacher, S. Kluge.

Final approval of the article: D. Wichmann, J.P. Sperhake, M. Lütgehetmann, S. Steurer, C. Edler, A. Heinemann, F. Heinrich, H. Mushumba, I. Kniep, A.S. Schröder, C. Burdelski, G. de Heer, A. Nierhaus, D. Frings, S. Pfefferle, H. Becker, H. Bredereke-Wiedling, A. de Weerth, H. Paschen, S. Sheikhzadeh-Eggers, A. Stang, S. Schmiedel, C. Bokemeyer, M.M. Addo, M. Aepfelbacher, K. Püschel, S. Kluge.

Provision of study materials or patients: D. Wichmann, A. Heinemann, F. Heinrich, H. Mushumba, C. Burdelski, G. de Heer, A. deWeerth, S. Sheikhzadeh-Eggers, C. Bokemeyer, M.M. Addo, K. Püschel.

Statistical expertise: S. Kluge.

Obtaining of funding: M. Aepfelbacher.

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: D. Wichmann, J.P. Sperhake, S. Steurer, C. Edler, A. Heinemann, F. Heinrich, A.S. Schröder, C. Burdelski, M.M. Addo, S. Kluge.

Collection and assembly of data: D. Wichmann, J.P. Sperhake, M. Lütgehetmann, S. Steurer, C. Edler, F. Heinrich, H. Mushumba, I. Kniep, A.S. Schröder, G. de Heer, A. Nierhaus, D. Frings, S. Pfefferle, H. Becker, H. Bredereke-Wiedling, A. de Weerth, H.R. Paschen, A. Stang, S. Schmiedel, K. Püschel, S. Kluge.

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 6 May 2020.

* Drs. Wichmann and Sperhake share first authorship.

† Drs. Püschel and Kluge share last authorship.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus—China. Accessed at www.who.int/csr/don/12-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-china/en. on 26 April 2020.

- 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al; China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-733. [PMID: 31978945] doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72?314 cases from the chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020. [PMID: 32091533] doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4. Johns Hopkins University. Coronavirus Resource Center. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Accessed at https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. on 26 April 2020.

- 5. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844-847. [PMID: 32073213] doi:10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054-1062. [PMID: 32171076] doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420-422. [PMID: 32085846] doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa062. Barton LM, Duval EJ, Stroberg E, et al. COVID-19 autopsies, Oklahoma, USA. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020. [PMID: 32275742] doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqaa062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-2-201201170-00008. Wichmann D, Obbelode F, Vogel H, et al. Virtual autopsy as an alternative to traditional medical autopsy in the intensive care unit: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:123-30. [PMID: 22250143] doi:10.7326/0003-4819-156-2-201201170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Collection and Submission of Postmortem Specimens from Deceased Persons with Known or Suspected COVID-19, March 2020 (Interim Guidance). Accessed at www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-postmortem-specimens.html. on 26 April 2020.

- 11. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25. [PMID: 31992387] doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.07.017. Romette JL, Prat CM, Gould EA, et al. The European Virus Archive goes global: a growing resource for research. Antiviral Res. 2018;158:127-134. [PMID: 30059721] doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0b013e31823d29ad. Molina DK, DiMaio VJ. Normal organ weights in men: part II—the brain, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2012;33:368-72. [PMID: 22182984] doi:10.1097/PAF.0b013e31823d29ad. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000175. Molina DK, DiMaio VJ. Normal organ weights in women: part II—the brain, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2015;36:182-7. [PMID: 26108038] doi:10.1097/PAF.0000000000000175. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0736LE. Wang Y, Lu X, Chen H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of 344 intensive care patients with COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. [PMID: 32267160] doi:10.1164/rccm.202003-0736LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0543OC. Du Y, Tu L, Zhu P, et al. Clinical features of 85 fatal cases of COVID-19 from Wuhan: a retrospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. [PMID: 32242738] doi:10.1164/rccm.202003-0543OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17. doi: 10.7326/M13-2211. Wichmann D, Heinemann A, Weinberg C, et al. Virtual autopsy with multiphase postmortem computed tomographic angiography versus traditional medical autopsy to investigate unexpected deaths of hospitalized patients: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:534-41. [PMID: 24733194] doi:10.7326/M13-2211. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206522. Hanley B, Lucas SB, Youd E, et al. Autopsy in suspected COVID-19 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2020;73:239-242. [PMID: 32198191] doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206522. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. [PMID: 32217556] doi:10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-526277. Antoniak S, Mackman N. Multiple roles of the coagulation protease cascade during virus infection. Blood. 2014;123:2605-13. [PMID: 24632711] doi:10.1182/blood-2013-09-526277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201629. Oudkerk M, Büller HR, Kuijpers D, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of thromboembolic complications in COVID-19: report of the National Institute for Public Health of the Netherlands. Radiology. 2020:201629. [PMID: 32324101] doi:10.1148/radiol.2020201629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104362. Giannis D, Ziogas IA, Gianni P. Coagulation disorders in coronavirus infected patients: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and lessons from the past. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104362. [PMID: 32305883] doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30920-X. Li H, Liu L, Zhang D, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and viral sepsis: observations and hypotheses. Lancet. 2020. [PMID: 32311318] doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30920-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24. doi: 10.1007/s00063-020-00689-w. Kluge S, Janssens U, Welte T, et al. German recommendations for critically ill patients with COVID-19. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2020. [PMID: 32291505] doi:10.1007/s00063-020-00689-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.07.013. Gupta N, Zhao YY, Evans CE. The stimulation of thrombosis by hypoxia. Thromb Res. 2019;181:77-83. [PMID: 31376606] doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2019.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26. doi: 10.7326/M20-0533. Zhang H, Zhou P, Wei Y, et al. Histopathologic changes and SARS-CoV-2 immunostaining in the lung of a patient with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020. [PMID: 32163542] doi:10.7326/M20-0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010. Tian S, Hu W, Niu L, et al. Pulmonary pathology of early-phase 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia in two patients with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:700-704. [PMID: 32114094] doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004168117. Duan K, Liu B, Li C, et al. Effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:9490-9496. [PMID: 32253318] doi:10.1073/pnas.2004168117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0271. Dreher M, Kersten A, Bickenbach J, et al. The characteristics of 50 hospitalized COVID-19 patients with and without ARDS. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117:271-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30. doi: 10.1002/path.1560. Ding Y, He L, Zhang Q, et al. Organ distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in SARS patients: implications for pathogenesis and virus transmission pathways. J Pathol. 2004;203:622-30. [PMID: 15141376] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, et al. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1094-1099. [PMID: 32220112] doi:10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. [PMID: 32311448] doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]