Abstract

The World Health Organization and the World Health Assembly recommended eradicating hepatitis as a public threat by 2030. The accurate genotyping of hepatitis C virus (HCV) is crucial to achieving this goal because it is vital for the selection of anti-HCV therapy required for complete cure of HCV infection. We report the development of a method for accurate genotyping of HCV 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6 genotypes. The merits of the developed method for HCV genotyping include (i) requirement of a single polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primer set, (ii) room-temperature detection in 30 min after the PCR, (iii) no need of highly trained professionals, (iv) highly accurate HCV genotyping results afforded by highly specific DNA–DNA hybridization, and (v) probe sequences that can be used on other platforms.

1. Introduction

According to the 2018 report on hepatitis C virus (HCV) by the World Health Organization (WHO), 71 million people had chronic HCV infection worldwide. About 0.4 million died from chronic liver diseases, including cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma in 2015 alone.1 The World Health Assembly recommended the Global Health Sector Strategy (GHSS) to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public threat by 2030. It is required to diagnose 90% of the infected people and to treat at least 80% of them to eliminate hepatitis as a public threat.2 However, a significant barrier to this goal is that successful treatment of HCV infection critically depends on the correct identification of HCV genotypes, including 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6. Treatment of hepatitis C has made significant advances with the development of drugs such as PEGylated interferon (PegIFN)-α, ribavirin, and direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) such as dasabuvir, simeprevir, sofosbuvir, ombitasvir, and ledipasvir.3 However, HCV genotype identification is vital for tailoring anti-HCV therapy. The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) identifies that the choice of medicine or the combination drugs, and the duration of treatment varies depending on the HCV genotype.4 Therefore, not only the screening but also the correct HCV genotyping using a simple and accurate detection method is crucial to achieving the goals set forth by GHSS.

Among 67 confirmed and 20 provisional subtypes, the HCV 1 (46.2%; 1a (31%), 1b (68%)), HCV 2 (9.1%), HCV 3 (30.1%), HCV 4 (8.3%), and HCV 6 (5.4%) are the most common HCV genotypes on a global scale.5 However, the distribution and the subtypical composition of HCV 6 in Asian countries (Vietnam: HCV 6a (24%); Myanmar: HCV 6n (39%); Thailand: HCV 6f (56%), HCV 6n (22%), and HCV 6i (11%)) are significantly different from the overall global ratio.6 Therefore, for appropriate treatment of hepatitis C, the detection and discrimination of HCV genotypes using a simple and efficient method is of paramount importance.7

The methods based on the detection of HCV core antigens and anti-HCV IgG are used for HCV screening. However, these methods are not suitable for HCV genotyping.8 The sequence analysis of specific regions such as NS5, core, E1, and 5′ UTR is a gold standard for HCV genotyping. However, due to the longer turnaround time, high cost, and the requirement of highly trained professionals, sequencing analysis is not suitable for HCV genotyping in point-of-care settings.9 The nucleic acid-based assays, including real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), restriction fragment length polymorphism, heteroduplex mobility analysis, and line-probe assay, are available for HCV genotyping, but the agreement between the results of these methods is low.10

Most of these assays have limitations for the correct identification of HCV 1a, 1b, and 6.11 About 95% of the sequence homology between the HCV genotypes and subtypes is a reason behind the poor performance of the reported methods. Unfortunately, incorrect HCV genotyping can lead to critical errors in the choice of optimal drug therapy. Hence, there is a need for a rapid, simple, precise, and inexpensive genotyping test to execute the strict treatment regime in the management of hepatitis C.

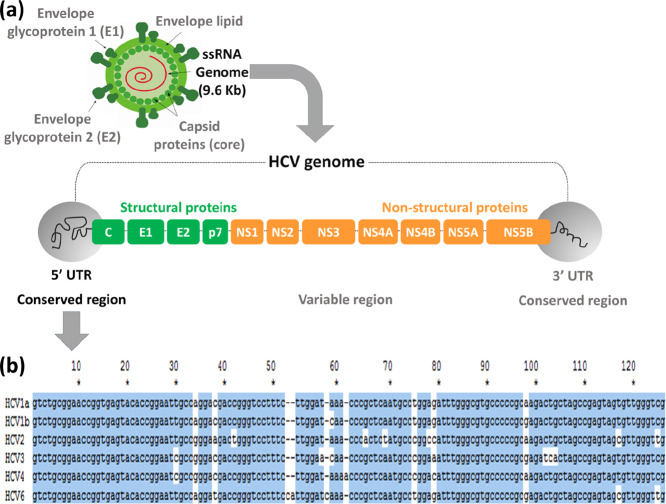

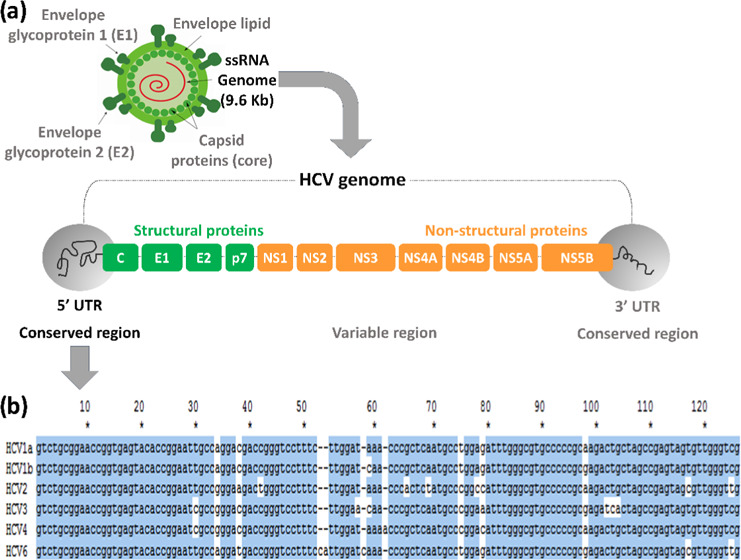

Herein, we report on the development of a method for the screening and genotyping of HCV genotypes, including 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6 (Table S1). The presented method takes advantage of the highly specific hybridization of the Cy5-labeled HCV PCR product with the meticulously designed HCV genotype-specific probes immobilized on the surface of a DNA chip. HCV is an RNA virus (9.6 kb nucleotides) consisting of a single open reading frame flanked by 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs), as shown in Figure 1. Even though the 5′ UTR has over 95% of the sequence homology between the HCV genotypes, it was chosen for the development of a method for the screening and genotyping of HCV 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6 for the following two reasons. First, the 5′ UTR is a conserved region, with no observed mutations due to drug treatment or demography, making it an attractive target for HCV genotyping. Second, the sequence homology allows the use of a single PCR primer set for PCR amplification of six different HCV genotypes.

Figure 1.

(a) HCV RNA structure including open reading frame and 5′ UTR, 3′ UTR regions, (b) alignment of sequences of HCV genotypes 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6 in the 5′ UTR.

2. Results and Discussion

For the optimization of the PCR conditions targeting the cDNA of the HCV genome (Table S2) obtained by RT-PCR, six forward primers (F1–F6) with melting temperatures (TM) in the range of 54.5–60.7 °C and six reverse primers (P1–P6) with TMs in the range of 52.5–59.7 °C were selected (Table S3). The obtained results of PCR optimization indicated that among all primer sets, the primer sets F2:R4 (5:20 pmol ratio/test) and F6:R6 (5:20 pmol ratio/test) showed a high yield of the PCR (Figure S1). However, for 100 copies each of HCV 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6, the primer set F6:R6 (5:20 pmol ratio/test) showed a high PCR yield for each HCV genotype (Figure S2). Therefore, the primer set F6:R6 (5:20 pmol ratio/test) was further used for the optimization of the annealing temperature using 100–10 copies of HCV1a. The annealing temperature of 59 °C and F6:R6 (5:20 pmol ratio/test) showed a high PCR yield in the range of 100–10 copies (Figure S3). About 22 probes (Figures S4–S9) were designed using the probe selection method12 to finally select six optimized probes for the highly efficient screening and genotyping of six HCV genotypes, including 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6 (Table S4). The designed probes appended with nine consecutive guanines were immobilized on the AMCA slides to obtain HCV DNA chips using a reported method.13

The Cy5-labeled PCR products of the six HCV genotypes were allowed to hybridize with the probes immobilized on the HCV DNA chips at 25 °C for 30 min in a commercial incubator. Then, HCV DNA chips were rinsed with washing buffer solutions A and B (Table S5) successively for 2 min each and dried. The fluorescence signal intensities were measured on ScanArrayLite, followed by image analysis with QuantArray software (Packard Bioscience).

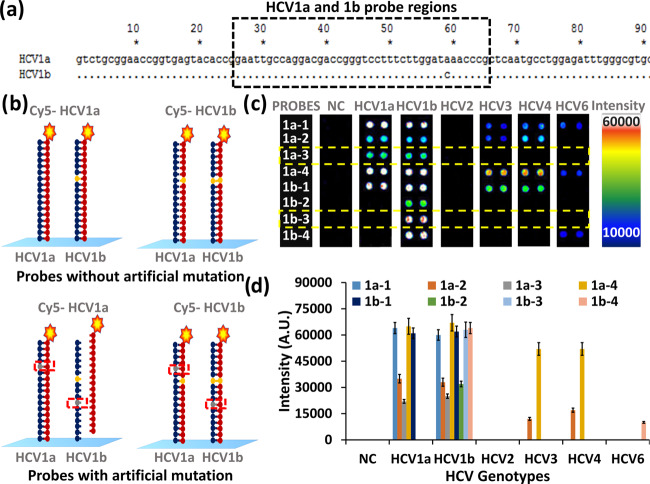

As depicted in Figure 2a, the HCV 1a and 1b genotypes have only one mismatch in the probe-binding region. Therefore, for discrimination of HCV 1a and 1b, four probes for each genotype were designed. Probes 1a-1 and 1b-1 were without artificial mutation, and probes 1a-2 to 1a-4 and 1b-2 to 1b-4 were with one artificial mutation (Figures 2c–d, Table S4, and Figures S4–S9).

Figure 2.

Selection of probes for HCV1a and HCV1b. (a) alignment of HCV1a and 1b sequences indicating the probe region, (b) hybridization of HCV 1a and 1b PCR products with HCV1a and HCV1b probes with and without an artificial mutation, (c) and (d) fluorescence intensities for respective probes upon hybridization with respective PCR products.

The Cy5-labeled single-stranded DNA was obtained by the reaction of the amine group of DNA with the Cy5-Dye monoreactive NHS ester by following the standard protocol provided by the manufacturer with the monoreactive Cy5 Dye (GE Healthcare UK Limited, Buckinghamshire, U.K.). Hybridization of Cy5-labeled PCR products of HCV 1a and 1b with immobilized probes showed specific as well as nonspecific hybridization with HCV1a and HCV1b probes without artificial mutations 1a-1 and 1b-1, respectively, as depicted in Figures 2b–d. These probes also showed nonspecific hybridization with PCR products of other HCV genotypes. However, the HCV 1a probe with artificial mutation (1a-3) showed high specificity for the HCV1a PCR product. The two-nucleotide (separated by three nucleotides) mismatch between the HCV1b probe (1b-3) and the HCV1a PCR product allowed the elimination of nonspecific hybridization of the HCV1a PCR product with the HCV1b probe. The HCV1b probe with artificial mutation (1b-3) showed specific hybridization with the HCV1b PCR product and nonspecific hybridization only with the HCV1a PCR product, among other HCV genotypes. Therefore, for the detection of HCV1a, the probe with artificial mutation (1a-3) was used for further studies. However, the simultaneous hybridization of the HCV1b PCR product with probes 1a-3 and 1b-3 is used for the detection of the HCV1b genotype. It is interesting to notice that probes 1a-3 and 1b-3 did not hybridize with PCR products of any other HCV genotype. The improvement in sensitivity of the probes using artificial mutation was in accordance with our previous report on the generalized probe selection method for DNA chips.12 The use of artificial mutation decreases the melting temperature (TM) of the probes, thus reducing its nonspecific hybridization with other probes.

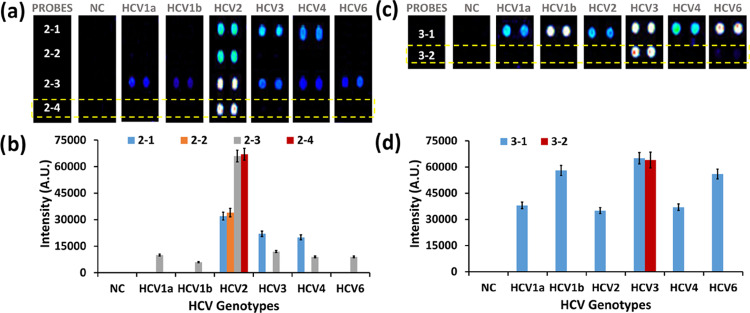

For the correct genotyping of HCV2 and HCV3, four (2-1 to 2-4) and two (3-1, 3-2) probes were designed, respectively (Table S4 and Figures S4–S9). As depicted in Figure 3a,b, the probes without artificial mutation (2-1 and 2-3) showed specific hybridization with the PCR product of the HCV2 genotype and nonspecific hybridizations with PCR products of other HCV genotypes. The probes with artificial mutations (2-2 and 2-4) showed highly specific hybridization with the HCV2 genotype. Probe 2-4, which had four nucleotide mismatches with HCV1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6 (Figures S4–S9), showed highly specific hybridization with HCV2. Furthermore, probe 2-4 showed two times higher signal intensity than probe 2-2. Hence, probe 2-4 was selected for HCV2 genotyping. Similarly, as depicted in Figure 3c,d, probe 3-2 (with artificial mutation) containing 5, 4, 5, 5, 4 nucleotide mismatches with HCV1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6, respectively (Figures S4–S9), showed highly specific hybridization with the HCV3 PCR product making it a potential candidate for HCV3 genotyping.

Figure 3.

Selection of probes for HCV2 and HCV3 genotyping. (a, b) Fluorescence intensities of HCV2 probes upon hybridization with PCR products of HCV 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6. (c, d) Fluorescence intensities of HCV3 probes upon hybridization with PCR products of HCV 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6.

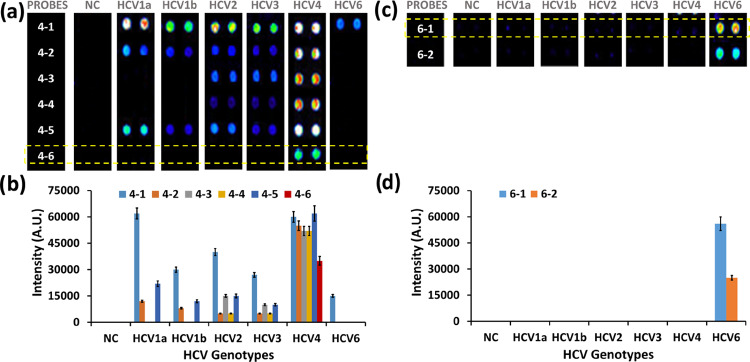

The discrimination of HCV4 was challenging as it has high sequence homogeneity with other HCV genotypes. As shown in Figure 4a,b, a total of six probes, including three probes without artificial mutation (4-1, 4-3, and 4-5) and three probes with artificial mutation (4-2, 4-4, and 4-6) were initially designed for HCV4 genotyping. Probe 4-6 showed highly specific hybridization with the HCV4 genotype. There were no nonspecific hybridizations for probe 4-6 as it had 2, 3, 2, 4, and 2 (with two additional insertions) nucleotide mismatches with the genomic sequence of other HCV genotypes (Figures S4–S9). Even though the signal intensity was low (35 000 a.u.), probe 4-6 was selected for HCV4 genotyping.

Figure 4.

Selection of probes for HCV4 and HCV6 genotyping. (a, b) Fluorescence intensities of HCV4 probes upon hybridization with PCR products of HCV 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6. (c, d) Fluorescence intensities of HCV6 probes upon hybridization with PCR products of HCV 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6.

The highly accurate detection and genotyping of HCV6 was the most straightforward case among all other HCV genotypes as its genome contained two insertions (Figures 1 and S4–S9). Among the two probes designed for HCV6 genotyping, probe 6-1 (without artificial mutation) showed high selectivity with considerably higher signal intensity than probe 6-2 (with artificial mutation). Therefore, probe 6-1 was selected for HCV6 genotyping.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first article on the development of a method for the screening and genotyping of six major HCV genotypes. The commercial nucleic acid-based assays available in the market are known to have limitations in the correct detection and identification of HCV1a and 1b.14 The accurate HCV genotype identification critically influences the success of treatment. The HCV1 screening and subtyping to differentiate 1a and 1b subtypes are crucial before starting the antiviral therapy because the choice of DAA, the necessity to use ribavirin, and treatment duration are dependent on the HCV genotype infection found in patients.

The present method requires further validation using clinical specimens. The results presented in this article are based on the synthetic template DNA. One of the limitations of the presented method is that it is based on the DNA chip hybridization that requires several steps, including PCR amplification, DNA–DNA hybridization, washing, drying, and scanning. Therefore, the primer set and probes optimized in this study will be used for the generation of a lateral flow strip membrane assay that can be implemented in point-of-care settings.

3. Conclusions

The obtained results indicate that for accurate HCV screening and genotyping of HCV1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and 6, probes 1a-3, 1b-3, 2-4, 3-2, 4-6, and 6-1, respectively, are highly applicable. The guidelines set forth by the EASL and the WHO clearly indicate that the accurate detection of HCV genotypes is decisive for the efficient treatment of hepatitis C. The presented method, and especially the designed probes, have a very high potential for precise screening and genotyping of HCV genotypes 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, and, 6 in clinical settings.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals, Korea. All of the oligonucleotides were purchased from Bioneer (Daejeon, South Korea). The RT-PCR premix and RNA extraction kits were obtained from Invitrogen, Korea. Glass slides (2.5 × 7.5 cm2) were purchased from Paul Marienfeld GmbH & Co. KG, Germany. All washing solvents for the substrates are of HPLC grade from SK Chemicals, Korea. Ultrapure water (18 MΩ/cm) was obtained from a Milli-Q purification system (Millipore). The DNA chips modified with mentioned probes (Table S2) were obtained from Biometrix Technology Inc., Korea. Oligonucleotides were spotted using a Qarray2 microarrayer (Genetix Technologies, Inc.) to produce DNA Chips used for the experiments. All DNA chips used in this study were obtained by following a previously reported method.15

4.2. Optimization of Primer and PCR Conditions

The PCR amplification process is briefly explained here (Table S3). For the PCR of HCV 1a (1000 copies), Taq-DNA-Polymerase was initially activated for 5 min at 94 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s denaturation at 94 °C, annealing for 15 s at 57 °C, and extension for 15 s at 72 °C. The program ended with a 5 min fill-in step at 72 °C.

4.3. Preparation of the HCV DNA Chip

The HCV DNA Chips were prepared by following a previous report.15 In brief, the immobilization solution containing oligonucleotide probes was spotted to make 6 by 3 pixels on the 9G slides. The microarrayed 9G slides were then kept in an incubator (25 °C, 50% humidity) for 4 h to immobilize the oligonucleotides. The slides were then suspended in the blocking buffer solution at 25 °C for 30 min, to remove the excess oligonucleotides and to deactivate the nonspotted area. Then, the slides were rinsed with washing buffer solutions A and B for 5 min each and then dried with a commercial centrifuge to obtain the HCV 9G DNA Chip. Before hybridization, the HCV DNA Chip was covered with Secure-Seal hybridization chambers.

4.4. Typical Hybridization and Washing Procedure

Hybridizations were done using Cy5-labeled PCR products of the HCV genotypes at 25 °C for 30 min in a commercial incubator. Then, the HCV 9G DNA Chip was rinsed with washing buffer solutions A and B successively for 2 min each, to remove the excess target DNA, and dried with a commercial centrifuge (1000 rpm). The fluorescence signal of the microarray was measured on ScanArrayLite, and the images were analyzed by Quant Array software (Packard Bioscience).

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) and the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) through the Encouragement Program for The Industries of Economic Cooperation Region (Project No. P0004191). This research was also supported by the Hallym University Research Fund (HRF-201911-008).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c00386.

Strains covered by selected HCV probes; optimization of PCR and electrophoresis conditions and selection of primers; probes immobilized on the DNA Chip with respect to the targeted HCV genotypes; alignment of selected probe sequences with HCV genotype sequences; composition of solutions used for immobilization, blocking, hybridization, and washing (PDF)

Author Contributions

† S.D.W. and S.B.N. authors contributed equally. Hence, both should be considered as first authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- WHO, 2018. https://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/hepatitis-c-guidelines-2018/en/.

- WHO, 2016. https://www.who.int/hepatitis/strategy2016-2021/ghss-hep/en/.

- Mishra P.; Murray J.; Birnkrant D. Direct-acting antiviral drug approvals for treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection: Scientific and regulatory approaches to clinical trial designs. Hepatology 2015, 62, 1298–1303. 10.1002/hep.27880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2018. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 461–511. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Smith D. B.; Bukh J.; Kuiken C.; Muerhoff A. S.; Rice C. M.; Stapleton J. T.; Simmonds P. Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: Updated criteria and genotype assignment web resource. Hepatology 2014, 59, 318–327. 10.1002/hep.26744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Messina J. P.; Humphreys I.; Flaxman A.; Brown A.; Cooke G. S.; Pybus O. G.; Barnes E. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology 2015, 61, 77–87. 10.1002/hep.27259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Pham V. H.; Nguyen H. D.; Ho P. T.; Banh D. V.; Pham H. L.; Pham P. H.; Lu L.; Abe K. Very high prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotype 6 variants in southern Vietnam: large-scale survey based on sequence determination. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 64, 537–539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lwin A. A.; Shinji T.; Khin M.; Win N.; Obika M.; Okada S.; Koide N. Hepatitis C virus genotype distribution in Myanmar: predominance of genotype 6 and existence of new genotype 6 subtype. Hepatol. Res. 2007, 37, 337–345. 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Akkarathamrongsin S.; Praianantathavorn K.; Hacharoen N.; Theamboonlers A.; Tangkijvanich P.; Tanaka Y.; Mizokami M.; Poovorawan Y. Geographic distribution of hepatitis C virus genotype 6 subtypes in Thailand. J. Med. Virol. 2010, 82, 257–262. 10.1002/jmv.21680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warkad S. D.; Nimse S. B.; Song K. S.; Kim T. HCV Detection, Discrimination, and Genotyping Technologies. Sensors 2018, 18, E3423. 10.3390/s18103423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Heidrich B.; Pischke S.; Helfritz F. A.; Mederacke I.; Kirschner J.; Schneider J.; Raupach R.; Jäckel E.; Barg-Hock H.; Lehner F.; Klempnauer J.; von Hahn T.; Cornberg M.; Manns M. P.; Ciesek S.; Wedemeyer H. Hepatitis C virus core antigen testing in liver and kidney transplant recipients. J. Viral. Hepatol. 2014, 21, 769–779. 10.1111/jvh.12204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kamili S.; Drobeniuc J.; Araujo A. C.; Hayden T. M. Laboratory diagnostics for hepatitis C virus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, S43–S48. 10.1093/cid/cis368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firdaus R.; Saha K.; Biswas A.; Sadhukhan P. C. Current molecular methods for the detection of hepatitis C virus in high risk group population: A systematic review. World J. Virol. 2015, 4, 25–32. 10.5501/wjv.v4.i1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cai Q.; Zhao Z.; Liu Y.; Shao X.; Gao Z. Comparison of three different HCV genotyping methods: core, NS5B sequence analysis and line probe assay. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 31, 347–352. 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mazzuti L.; Lozzi M. A.; Riva E.; Maida P.; Falasca F.; Antonelli G.; Turriziani O. Evaluation of performances of VERSANT HCV RNA 1.0 assay (kPCR) and Roche COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HCV test v2.0 at low level viremia. New Microbiol. 2016, 39, 224–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kessler H. H.; Cobb B. R.; Wedemeyer H.; Maasoumy B.; Michel-Treil V.; Ceccherini-Nelli L.; Bremer B.; Hübner M.; Helander A.; Khiri H.; Heilek G.; Simon C. O.; Luk K.; Aslam S.; Halfon P. Evaluation of the COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HCV test, v2.0 and comparison to assays used in routine clinical practice in an international multicenter clinical trial: the ExPECT study. J. Clin. Virol. 2015, 67, 67–72. 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Sunanchaikarn S.; Theamboonlers A.; Chongsrisawat V.; Yoocharoen P.; Tharmaphornpilas P.; Warinsathien P.; Sinlaparatsamee S.; Paupunwatana S.; Chaiear K.; Khwanjaipanich S.; Poovorawan Y. Seroepidemiology and genotypes of hepatitis C virus in Thailand. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2007, 25, 175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yang R.; Cong X.; Du S.; Fei R.; Rao H.; Wei L. Performance Comparison of the Versant HCV Genotype 2.0 Assay (LiPA) and the Abbott Realtime HCV Genotype II Assay for Detecting Hepatitis C Virus Genotype 6. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 3685–3692. 10.1128/JCM.00882-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimse S. B.; Song K. S.; Kim J.; Ta V. T.; Nguyen V. T.; Kim T. A generalized probe selection method for DNA chips. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 12444–12446. 10.1039/c1cc15137a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K. S.; Nimse S. B.; Kim J.; Kim J.; Nguyen V. T.; Ta V. T.; Kim T. 9G DNAChip: Microarray based on the multiple interactions of 9 consecutive guanines. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 7101–7103. 10.1039/c1cc12489g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chueca N.; Rivadulla I.; Lovatti R.; Reina G.; Blanco A.; Fernandez-Caballero J. A.; Cardeñoso L.; Rodriguez-Granjer J.; Fernandez-Alonso M.; Aguilera A.; Alvarez M.; Galán J. C.; García F. Using NS5B Sequencing for Hepatitis C Virus Genotyping Reveals Discordances with Commercial Platforms. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0153754 10.1371/journal.pone.0153754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Guelfo J. R.; Macias J.; Neukam K.; Di Lello F. A.; Mira J. A.; Merchante N.; Mancebo M.; Nuñez-Torres R.; Pineda J. A.; Real L. M. Reassessment of Genotype 1 Hepatitis C Virus Subtype Misclassification by LiPA 2.0: Implications for Direct-Acting Antiviral Treatment. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 4027–4029. 10.1128/JCM.02209-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song K. S.; Nimse S. B.; Kim J.; Kim J.; Ta V. T.; Nguyen V. T.; Kim T. 9G DNAChip: a platform for the efficient detection of proteins. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 7716–7718. 10.1039/c1cc12721g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.