Abstract

Background:

Tests for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) based on reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are being used to “rule out” infection among high-risk persons, such as exposed inpatients and health care workers. It is critical to understand how the predictive value of the test varies with time from exposure and symptom onset to avoid being falsely reassured by negative test results.

Objective:

To estimate the false-negative rate by day since infection.

Design:

Literature review and pooled analysis.

Setting:

7 previously published studies providing data on RT-PCR performance by time since symptom onset or SARS-CoV-2 exposure using samples from the upper respiratory tract (n = 1330).

Patients:

A mix of inpatients and outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Measurements:

A Bayesian hierarchical model was fitted to estimate the false-negative rate by day since exposure and symptom onset.

Results:

Over the 4 days of infection before the typical time of symptom onset (day 5), the probability of a false-negative result in an infected person decreases from 100% (95% CI, 100% to 100%) on day 1 to 67% (CI, 27% to 94%) on day 4. On the day of symptom onset, the median false-negative rate was 38% (CI, 18% to 65%). This decreased to 20% (CI, 12% to 30%) on day 8 (3 days after symptom onset) then began to increase again, from 21% (CI, 13% to 31%) on day 9 to 66% (CI, 54% to 77%) on day 21.

Limitation:

Imprecise estimates due to heterogeneity in the design of studies on which results were based.

Conclusion:

Care must be taken in interpreting RT-PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection—particularly early in the course of infection—when using these results as a basis for removing precautions intended to prevent onward transmission. If clinical suspicion is high, infection should not be ruled out on the basis of RT-PCR alone, and the clinical and epidemiologic situation should be carefully considered.

Primary Funding Source:

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Johns Hopkins Health System, and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Tests for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 based on reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are being used to “rule out” infection among high-risk persons, such as exposed inpatients and health care workers, but studies suggest that test sensitivity may be low. This study estimates the false-negative rate by day since exposure to infection by pooling and modeling data from previously published studies on RT-PCR sensitivity of upper respiratory tract samples of persons who were ultimately confirmed to have coronavirus disease 19.

Tests for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) based on reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are often used to “rule out” infection among high-risk persons, such as exposed inpatients and health care workers. Hence, it is critical to understand how the predictive value changes in relation to time since exposure or symptoms, especially when using the results of these tests to make decisions about whether to stop using personal protective equipment or allow exposed health care workers to return to work. The sensitivity and specificity of PCR-based tests for SARS-CoV-2 are poorly characterized, and the “window period” after acquisition in which testing is most likely to produce false-negative results is not well known.

Accurate testing for SARS-CoV-2, followed by appropriate preventive measures, is paramount in the health care setting to prevent both nosocomial and community transmission. However, most hospitals are facing critical shortages of SARS-CoV-2 testing capacity, personal protective equipment, and health care personnel (1). As the epidemic progresses, hospitals increasingly have to decide how to respond when a patient or health care worker has a known exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Although 14 days of airborne precautions or quarantine would be a conservative approach to minimizing transmission per guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2), this is not feasible for many hospitals given starkly limited resources.

As RT-PCR–based tests for SARS-CoV-2 are becoming more available, they are increasingly being used to “rule out” infection to conserve scarce personal protective equipment and preserve the workforce. When exposed health care workers test negative, they may be cleared to return to work; similarly, when exposed patients test negative, airborne or droplet precautions may be removed. If negative results from tests done during the window period are treated as strong evidence that an exposed person is SARS-CoV-2–negative, preventable transmission could occur.

It is critical to understand how the predictive value of the test varies with time from exposure and symptom onset to avoid being falsely reassured by negative results from tests done early in the course of infection. The goal of our study was to estimate the false-negative rate by day since infection.

Methods

Source Data

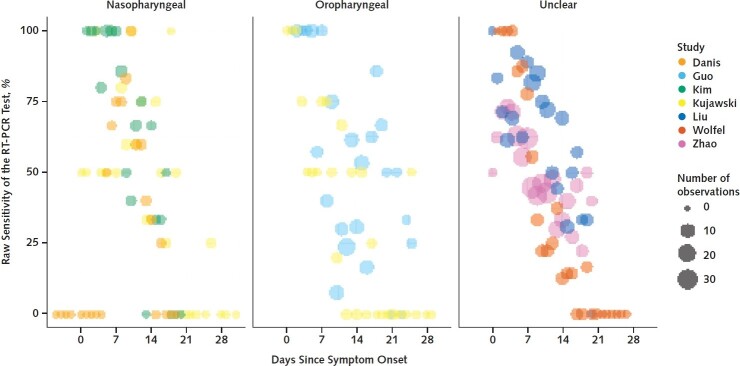

As part of a broader effort to provide critical evaluation of emerging evidence, the Novel Coronavirus Research Compendium at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health did a literature review to identify preprint and peer-reviewed articles on SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics (3). Investigators searched PubMed, bioRxiv, and medRxiv using a strategy detailed in Supplement Table 1. The search was last updated on 15 April 2020. From the broader search, we identified articles that provided data on RT-PCR performance by time since symptom onset or exposure using samples derived from nasal or throat swabs among patients tested for SARS-CoV-2. Inclusion criteria were use of an RT-PCR–based test, sample collection from the upper respiratory tract, and reporting of time since symptom onset or exposure. We excluded articles that did not clearly define time between testing and symptom onset or exposure. We identified 7 studies (2 preprints and 5 peer-reviewed articles) (4–10) with a total of 1330 respiratory samples analyzed by RT-PCR. Figure 1 summarizes the source data. One study by Kujawski and colleagues (10) provided both nasal and throat samples for each patient; we used only the nasal samples in our analysis.

Figure 1.

Sensitivity of RT-PCR tests, by study and days since symptom onset, for nasopharyngeal samples (left), oropharyngeal samples (middle), and unspecified upper respiratory tract (right).

RT-PCR = reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

How Cases Were Defined

Most studies (Danis and colleagues [6], Wölfel and colleagues [4], Kim and colleagues [7], Kujawski and colleagues [10], and Zhao and colleagues [8]) did serial testing and required at least 1 positive RT-PCR result to consider a case confirmed. Our pooled analysis included only confirmed cases from those studies. The studies by Liu and colleagues (9) and Guo and colleagues (5) included both confirmed cases (≥1 positive RT-PCR result, similar to other studies; n = 153 for Liu and n = 82 for Guo) and probable cases as determined by a set of clinical criteria (n = 85 for Liu and n = 58 for Guo). In both studies, most probable case patients were positive for IgM or IgG SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (67 of 85 probable cases for Liu were IgM- or IgG-positive, and 54 of 58 for Guo were IgM-positive). Thus, 22 participants were considered case patients on the basis of clinical criteria alone because we could not separate them out using the information provided. Supplement Table 2 provides additional details on the source data used in our calculations. As a sensitivity analysis to assess the effect of individual studies on our inferences, we excluded each study in turn from calculations of the posttest probability of infection after a negative RT-PCR result (Supplement Figure 3).

Statistical Analysis

Model for Estimating False-Negative Rate and False Omission Rate by Time Since Exposure

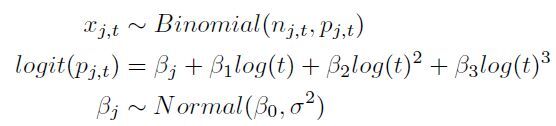

Using an approach similar to that of Leisenring and colleagues (11) and Azman and colleagues (12), we fitted a Bayesian hierarchical logistic regression model for test sensitivity pj,t with a random effect for study j and a cubic polynomial spline for log-time t since exposure:

where xj,t is the number of patients who tested positive on RT-PCR out of nj,t total tests t days after exposure in study j. The exposure was assumed to have occurred 5 days before symptom onset based on the median incubation period previously estimated in a large study of transmission in household contacts (13) and among publicly confirmed cases (14). From the sensitivity, we calculated the expected false-negative rate on each day. We also calculated the posttest probability of infection, assuming a pretest probability based on the attack rate in close household contacts of SARS-CoV-2 case patients in Shenzhen, China (77 of 686 [11.2%]) (14). We assumed a specificity of 100% for RT-PCR, as reported in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration package insert for the Quest RT-PCR assay for SARS-CoV-2, which based its estimate on testing in 72 presumed negative samples from the upper respiratory tract and 30 from the lower respiratory tract (15). This specificity is further supported by a European study that showed no cross-reactivity with other coronaviruses in 297 clinical samples (16).

Sensitivity Analyses

Although the Food and Drug Administration reported that specificity for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR is 100%, many of the supporting studies were done outside the United States, and we cannot exclude variability in test performance. Thus, we repeated our analysis assuming 90% specificity to assess the sensitivity of our results to this assumption. A second assumption of our model, the 5-day incubation period, was based on a large study of household contacts in Shenzhen (13) and on publicly confirmed cases (14). We did additional analyses varying the incubation period to 3 and 7 days to assess the sensitivity of our results to this assumption. We also repeated analyses excluding 1 study each time to assess the effect on our inferences.

Code and Data Availability

The data and code used to run this analysis are publicly available at https://github.com/HopkinsIDD/covidRTPCR (17).

Role of the Funding Source

The funders had no influence on the study's design, conduct, or reporting.

Results

Probability of a False-Negative Result Among SARS-CoV-2–Positive Patients, by Day Since Exposure

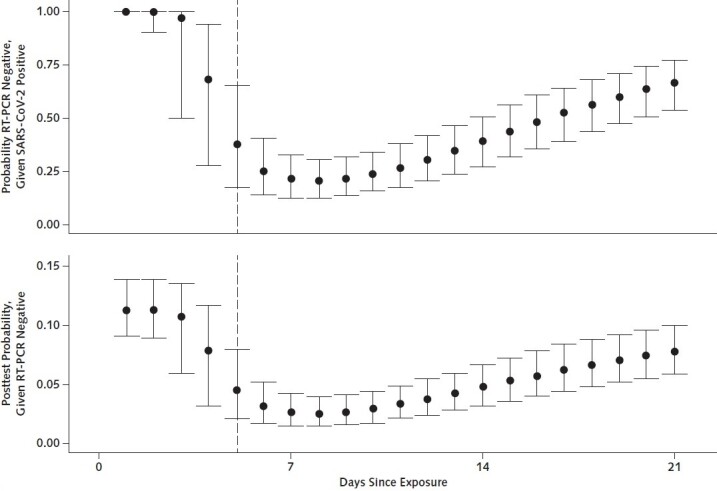

Over the 4 days of infection before the typical time of symptom onset (day 5), the probability of a false-negative result in an infected person decreases from 100% (95% CI, 100% to 100%) on day 1 to 67% (CI, 27% to 94%) on day 4, although there is considerable uncertainty in these numbers. On the day of symptom onset, the median false-negative rate was 38% (CI, 18% to 65%) (Figure 2, top). This decreased to 20% (CI, 12% to 30%) on day 8 (3 days after symptom onset) then began to increase again, from 21% (CI, 13% to 31%) on day 9 to 66% (CI, 54% to 77%) on day 21.

Figure 2.

Probability of having a negative RT-PCR test result given SARS-CoV-2 infection (top) and of being infected with SARS-CoV-2 after a negative RT-PCR test result (bottom), by days since exposure.

RT-PCR = reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Posttest Probability of Infection if RT-PCR Result is Negative (1 Minus Negative Predictive Value)

Translating these results into a posttest probability of infection, a negative result on day 3 would reduce our estimate of the relative probability that a case patient was infected by only 3% (CI, 0% to 47%) (for example, from 11.2%, the rate seen in a large study of household contacts, to 10.9%) (Figure 2, bottom). Tests done on the first day of symptom onset are more informative, reducing the inferred probability that a case patient was infected by 60% (CI, 33% to 80%).

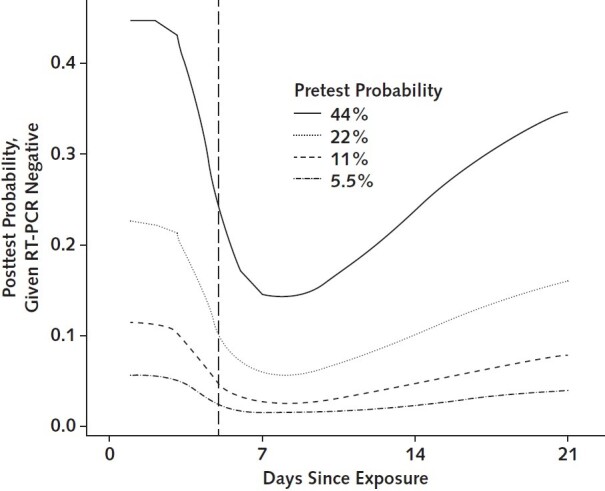

Variation in Posttest Probability of Infection if RT-PCR Result is Negative, by Pretest Probability

The posttest probability of infection in a patient with a negative RT-PCR result varies with the pretest probability of infection—that is, how likely infection is on the basis of the magnitude of exposure or clinical presentation. When we assumed a high pretest probability of infection (4 times the attack rate observed in a large cohort study), the posttest probability of infection was at minimum 14% (CI, 9% to 20%) 8 days after exposure (Figure 3). When we assumed a lower pretest probability of 5.5% (half the observed attack rate), the negative posttest probability of infection was still minimized 8 days after exposure (1.2% [CI, 0.7% to 2.0%]).

Figure 3.

Posttest probability of SARS-CoV-2 infection after a negative RT-PCR result, by pretest probability of infection.

RT-PCR = reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Sensitivity Analyses

When we repeated our analysis assuming a specificity of RT-PCR of 90% rather than 100%, results were very similar (Supplement Figure 1). We found a higher probability of infection in the setting of a negative RT-PCR result, with the greatest difference occurring on day 2 (12.4% vs. 11.3% [1.1 percentage point higher]). When we repeated our analyses varying the incubation period, we found that an earlier onset time of symptoms led to a quicker decrease in false omission rate and a later onset time led to a slower decrease; however, curves were similar overall, and our primary inferences remained the same relative to the date of onset (Supplement Figure 2). When we repeated our analysis of the posttest probability of infection excluding a different study each time, our inferences were unchanged (Supplement Figure 3).

Discussion

Over the 4 days of infection before the typical time of symptom onset (day 5), the probability of a false-negative result in an infected person decreased from 100% on day 1 to 68% on day 4. On the day of symptom onset, the median false-negative rate was 38%. This decreased to 20% on day 8 (3 days after symptom onset) then began to increase again, from 21% on day 9 to 66% on day 21. The false-negative rate was minimized 8 days after exposure—that is, 3 days after the onset of symptoms on average. As such, this may be the optimal time for testing if the goal is to minimize false-negative results. When the pretest probability of infection is high, the posttest probability remains high even with a negative result. Furthermore, if testing is done immediately after exposure, the pretest probability is equal to the negative posttest probability, meaning that the test provides no additional information about the likelihood of infection.

Since the outbreak began, concerns have been raised about the poor sensitivity of RT-PCR–based tests (18); 1 study has suggested that this might be as low as 59% (19). We have designed a publicly available model that provides a framework for estimating the performance of these tests by time since exposure and can be updated as additional data become available.

Tests for SARS-CoV-2 based on RT-PCR added little diagnostic value in the days immediately after exposure. This is consistent with a window period between acquisition of infection and detectability by RT-PCR seen in other viral infections, such as HIV and hepatitis C (20, 21). Our study suggests a window period of 3 to 5 days, and we would not recommend making decisions regarding removing contact precautions or ending quarantine on the basis of results obtained in this period in the absence of symptoms. Although the false-negative rate is minimized 1 week after exposure, it remains high at 21%. Possible mechanisms for the high false-negative rate include variability in individual amount of viral shedding and sample collection techniques.

One consideration is whether serial testing would offer any benefit in test performance compared with a single test. If we assume independence of the test results, serial testing would almost certainly reduce the false-negative rate; however, without more data on the underlying mechanism for the high false-negative rate, this assumption may not be warranted. For example, if the rate were due to individual variability in viral shedding, performance would likely not be improved by serial tests. Although we are aware of no large-scale studies, some preliminary reports suggest lack of independence; for example, in 1 case report of a person with infection confirmed on the basis of both radiologic findings and RT-PCR positivity from endotracheal aspirates, RT-PCR results from nasopharyngeal swabs were negative throughout the clinical course (6). Further studies to better characterize the underlying mechanism for poor diagnostic performance of SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR are needed to inform testing strategies.

The relationship between a false-negative result and infectiousness is unclear, and patients who test negative on samples from nasopharyngeal swabs may be less likely to transmit the virus regardless of true case status. We found an increase in the false-negative rate starting 9 days after exposure; however, it is possible that some of the later results were not true false negatives but rather represented clearance of the infection. Thus, interpretation later in the clinical course depends on the purpose of testing: If the goal is to clear a patient from isolation, these negative results may be correct, although more data are needed given studies showing viral replication in other sites. However, if the goal of the test is to evaluate whether additional follow-up is needed or whether the patient should be treated as SARS-CoV-2–positive for the purpose of contact tracing, the test may not be providing the desired information and caution should be used in decision making. Because antibodies appear later in the course of infection, a combination of antibody testing and RT-PCR might be most useful for patients more remote from symptoms or exposure.

Our study has several limitations. There was significant heterogeneity in the design and conduct of the underlying studies from which the data used in our analyses were drawn. However, when we did a sensitivity analysis excluding each study in turn, we found that no 1 study was especially influential and inferences were largely unchanged. Sample collection techniques varied across studies (oropharyngeal vs. nasopharyngeal swabs), and several studies stated that samples were from the upper respiratory tract without providing further details. Thus, we could not fully account for differences in sample collection techniques. Most studies tested samples at time of symptom onset rather than time of exposure, leading to high variance in estimates in the first few days after exposure. Our model is applicable only in the setting of a known, one-time exposure, not in the setting of continuous exposure, such as in health care workers who may be exposed daily to SARS-CoV-2–positive patients. Finally, most studies defined true-positive cases as those with at least 1 positive RT-PCR result, meaning that patients who never tested positive would not be included; this could lead to underestimation of the true false-negative rate. Two studies included probable cases based on clinical and epidemiologic characteristics even if the patients had never had a positive RT-PCR result or serology. Because such criteria as fever, respiratory symptoms, and imaging findings are nonspecific, misclassification is likely, wherein some proportion of probable cases are actually true negatives rather than false negatives. We believe that this effect was small because excluding these studies from our analysis did not change our primary inferences.

In summary, care must be taken when interpreting RT-PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly early in the course of infection and especially when using these results as a basis for removing precautions intended to prevent onward transmission. If clinical suspicion is high, infection should not be ruled out on the basis of RT-PCR alone, and the clinical and epidemiologic situation should be carefully considered. In many cases, time of exposure is unknown and testing is done on the basis of time of symptom onset. The false-negative rate is lowest 3 days after onset of symptoms, or approximately 8 days after exposure. Clinicians should consider waiting 1 to 3 days after symptom onset to minimize the probability of a false-negative result. Further studies to characterize test performance and research into higher-sensitivity approaches are critical.

Biography

Financial Support: In part by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health; by the Johns Hopkins Health System; by grant NU2GGH002000 from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and by extramural grants R01AI135115 and T32DA007292 from the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures: Dr. Lauer reports grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases during the conduct of the study. Dr. Laeyendecker reports salary from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Division of Intramural Research during the conduct of the study. Authors not named here have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Disclosures can also be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M20-1495.

Editors' Disclosures: Christine Laine, MD, MPH, Editor in Chief, reports that her spouse has stock options/holdings with Targeted Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Darren B. Taichman, MD, PhD, Executive Editor, reports that he has no financial relationships or interests to disclose. Cynthia D. Mulrow, MD, MSc, Senior Deputy Editor, reports that she has no relationships or interests to disclose. Eliseo Guallar, MD, MPH, DrPH, Deputy Editor, Statistics, reports that he has no financial relationships or interests to disclose. Jaya K. Rao, MD, MHS, Deputy Editor, reports that she has stock holdings/options in Eli Lilly and Pfizer. Christina C. Wee, MD, MPH, Deputy Editor, reports employment with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Sankey V. Williams, MD, Deputy Editor, reports that he has no financial relationships or interests to disclose. Yu-Xiao Yang, MD, MSCE, Deputy Editor, reports that he has no financial relationships or interest to disclose.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol: Further details are available from Dr. Kucirka (e-mail, lauren@jhmi.edu). Statistical code and data set: Available at https://github.com/HopkinsIDD/covidRTPCR.

Corresponding Author: Lauren M. Kucirka, MD, PhD, 600 North Wolfe Street, Phipps Building Suite 279, Baltimore, MD 21287; e-mail, lauren@jhmi.edu.

Current Author Addresses: Dr. Kucirka: 600 North Wolfe Street, Phipps Building Suite 279, Baltimore, MD 21287.

Dr. Lauer: 615 North Wolfe Street, E6003, Baltimore, MD 21231.

Dr. Laeyendecker: 855 North Wolfe Street, Rangos Building, Room 538A, Baltimore, MD 21205.

Dr. Boon: 624 North Broadway, Room 888, Baltimore, MD 21215.

Dr. Lessler: 615 North Wolfe Street, E6545, Baltimore, MD 21231.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: L.M. Kucirka, S.A. Lauer, J. Lessler.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: L.M. Kucirka, S.A. Lauer, O. Laeyendecker, J. Lessler.

Drafting of the article: L.M. Kucirka, S.A. Lauer, J. Lessler.

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: L.M. Kucirka, O. Laeyendecker, D. Boon, J. Lessler.

Final approval of the article: L.M. Kucirka, S.A. Lauer, O. Laeyendecker, D. Boon, J. Lessler.

Statistical expertise: L.M. Kucirka, S.A. Lauer, J. Lessler.

Obtaining of funding: J. Lessler.

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: O. Laeyendecker, J. Lessler.

Collection and assembly of data: L.M. Kucirka, S.A. Lauer, D. Boon.

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 13 May 2020.

* Drs. Kucirka and Lauer contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9. The Lancet. COVID-19: protecting health-care workers [Editorial]. Lancet. 2020;395:922. [PMID: 32199474] doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. on 31 March 2020.

- 3. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. 2019 Novel Coronavirus Research Compendium (NCRC). 2020. Accessed at https://ncrc.jhsph.edu. on 8 May 2020.

- 4. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020. [PMID: 32235945] doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa310. Guo L, Ren L, Yang S, et al. Profiling early humoral response to diagnose novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [PMID: 32198501] doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa424. Danis K, Epaulard O, Bénet T, et al; Investigation Team. Cluster of coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) in the French Alps, 2020. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [PMID: 32277759] doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e142. Kim ES, Chin BS, Kang CK, et al; Korea National Committee for Clinical Management of COVID-19. Clinical course and outcomes of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: a preliminary report of the first 28 patients from the Korean cohort study on COVID-19. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e142. [PMID: 32242348] doi:10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [PMID: 32221519] doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.05.008. Liu L, Liu W, Wang S, et al. A preliminary study on serological assay for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in 238 admitted hospital patients. Preprint. Posted online 8 March 2020. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2020.03.06.20031856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10. Kujawski SA, Wong KK, Collins JP, et al. First 12 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States. Preprint. Posted online 12 March 2020. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2020.03.09.20032896.

- 11. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970615)16:11<1263::aid-sim550>3.0.co;2-m. Leisenring W, Pepe MS, Longton G. A marginal regression modelling framework for evaluating medical diagnostic tests. Stat Med. 1997;16:1263-81. [PMID: 9194271] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30141-5. Azman AS, Lauer S, Bhuiyan MTR, et al. Vibrio cholerae O1 transmission in Bangladesh: insights from a nationally-representative serosurvey. Preprint. Posted online 16 March 2020. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2020.03.13.20035352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020. [PMID: 32150748] doi:10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14. Bi Q, Wu Y, Mei S, et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in Shenzhen China: analysis of 391 cases and 1,286 of their close contacts. Preprint. Posted online 27 March 2020. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423.

- 15. Quest Diagnostics. SARS-CoV-2 RNA, qualitative real-time RT-PCR (test code 39433): package insert. Accessed at www.fda.gov/media/136231/download. on 20 April 2020.

- 16. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25. [PMID: 31992387] doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17. Kucirka LM, Lauer SA, Laeyendecker O, et al. Analysis of RT-PCR sensitivity by day since exposure or symptom onset. 2020. Accessed at https://github.com/HopkinsIDD/covidRTPCR. on 26 April 2020.

- 18. Krumholz HM. If you have coronavirus symptoms, assume you have the illness, even if you test negative. The New York Times. 1 April 2020. Accessed at www.nytimes.com/2020/04/01/well/live/coronavirus-symptoms-tests-false-negative.html. on 20 April 2020.

- 19. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020:200642. [PMID: 32101510] doi:10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2017.03.002. Konrad BP, Taylor D, Conway JM, et al. On the duration of the period between exposure to HIV and detectable infection. Epidemics. 2017;20:73-83. [PMID: 28365331] doi:10.1016/j.epidem.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.04390.x. Glynn SA, Wright DJ, Kleinman SH, et al. Dynamics of viremia in early hepatitis C virus infection. Transfusion. 2005;45:994-1002. [PMID: 15934999] [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data and code used to run this analysis are publicly available at https://github.com/HopkinsIDD/covidRTPCR (17).