Abstract

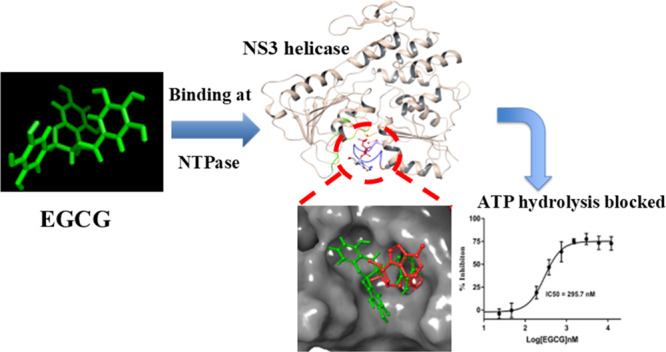

Since 2007, repeated outbreaks of Zika virus (ZIKV) have affected millions of people worldwide and created a global health concern with major complications like microcephaly and Guillain Barre’s syndrome. To date, there is not a single Zika-specific licensed drug present in the market. However, in recent months, several antiviral molecules have been screened against ZIKV. Among those, (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), a green tea polyphenol, has shown great virucidal potential against flaviviruses including ZIKV. The mechanistic understanding of EGCG-targeting viral proteins is not yet entirely deciphered except that little is known about its interaction with viral envelope protein and viral protease. We designed our current study to find inhibitory actions of EGCG against ZIKV NS3 helicase. NS3 helicase performs a significant role in viral replication by unwinding RNA after hydrolyzing NTP. We employed molecular docking and simulation approach and found significant interactions at the ATPase site and also at the RNA binding site. Further, the enzymatic assay has shown significant inhibition of NTPase activity with an IC50 value of 295.7 nM and Ki of 0.387 ± 0.034 μM. Our study suggests the possibility that EGCG could be considered as a prime backbone molecule for further broad-spectrum inhibitor development against ZIKV and other flaviviruses.

Introduction

Zika virus (ZIKV), a close relative of dengue virus (DENV), is primarily a mosquito-transmitted pathogen that has already affected millions of people in more than 40 countries including America, South Pacific, and South Asia.1,2 The real danger posed by ZIKV is neurological defects like microcephaly and Guillain-Barre syndrome in newborns and in adults, respectively.3,4 Epidemiological studies have also reported a sexual mode of ZIKV transmission which is further raising the threat alarm worldwide.5 As on 1st February 2016, the World Health Organization has called a global health emergency that demands the development of safe and effective therapeutics. In 2017, WHO has confirmed three cases of ZIKV in Ahmedabad District, Gujarat, State, India (http://www.who.int/). A recent ZIKV outbreak in 2018 has been observed in India where more than 200 Zika cases were confirmed including pregnant women. There is an urgency to develop antivirals against ZIKV. In past months, several bioactive molecules have been assayed either against ZIKV proteins or targeting cellular proteins by employing different approaches like screening new compound libraries or employing drug repurposing.6,7 Another essential aspect in drug discovery that could not be ignored is the use of natural products which are known to possess enormous structural and chemical variety over any other synthetic compound library.8 Moreover, natural products deliver a crucial advantage of being pre-selected evolutionarily with optimized chemical structures against biological targets.9 One such natural product is a polyphenol called EGCG which constitutes a major fraction (59% of all polyphenols) of green tea polyphenols and has shown multiple health benefits such as antitumor, antimicrobial, antioxidative, and antiviral.10 The antiviral role of EGCG has been well-demonstrated against several viruses such as hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), influenza virus (FLU), DENV, and chikungunya virus.11−15 In a recent study, EGCG has shown a strong virucidal effect against ZIKV with a probable mechanism related to the inhibition of the entry into the host cell demonstrated by computational finding.16,17 However, reports suggest that apart from viral entry inhibition EGCG can also block essential steps in the replication cycle of some viruses.10 Because of the lack of complete understanding of the EGCG inhibition mechanism on ZIKV, we designed our study to find a specific viral protein which could be targeted by EGCG. We have chosen NS3 helicase protein of ZIKV, a crucial enzyme in viral replication which unwinds genomic RNA after deriving energy from intrinsic nucleoside triphosphatase (NTPase) activity.18,19 In addition to RNA unwinding activity, flavivirus helicases have also been reported to participate in other vital functions such as ribosome biogenesis, pre-mRNA splicing, RNA export and degradation, RNA maturation, and translation.20 Hence, essential functions of these helicases make them attractive drug targets.

Like other flavivirus helicases, the ZIKV helicase also belongs to the SF2 (superfamily) family and a phylogenetically close relative of Murray Valley encephalitis virus (MVEV), DENV4, and DENV2.18 Full-length NS3 protein has N-terminal protease activity, and C-terminal is associated with helicase activity. ZIKV NS3 helicase (172–617 residues) is a large protein containing three domains where domain 1 (residues 175–332) and domain 2 (residues 333–481) forms NTPase pocket and domain 3 (residues 481–617) in association with domains 1 and 2 forms a RNA binding tunnel.21 Though ZIKV helicase is well-structured, the active sites at NTPase and RNA binding pockets contain highly flexible or disordered P-loop (193–203 residues) and RNA binding loop (244–255 residues) respectively, which are critical for helicase function.21,22 In general, past decade has evidenced the significant contribution of intrinsically disordered proteins/regions (IDRs/IDPs) in almost all biological processes, and the regions are considered as novel therapeutic targets.23−29 Despite the conversed active site amino acid residues among flavivirus helicases, ZIKV helicase shows different motor domain movements and RNA binding modes when compared to DENV helicase.21 Therefore, the critical functions of ZIKV helicase encourage the screening of antiviral molecules against its active sites. In a recent study, we have determined the inhibitory potential of a small molecule (HCQ) against ZIKV protease with computational and enzyme kinetics studies.30 Also, we have reported few natural compounds and targeted library molecules showing considerable binding potential at the NTPase site of ZIKV helicase.31,32 In this article, we have used molecular docking and simulation approach to find out a significant binding cavity for EGCG. Further, we have verified our computational findings by in vitro enzyme assay to probe the potential binding of EGCG at the NTPase site of ZIKV helicase.

Results

In Silico Docking Studies

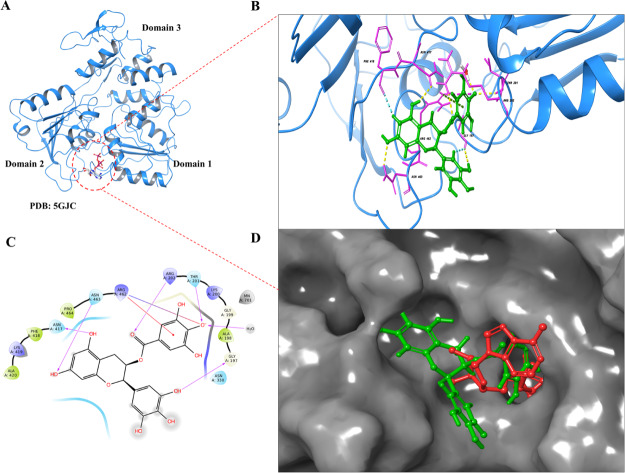

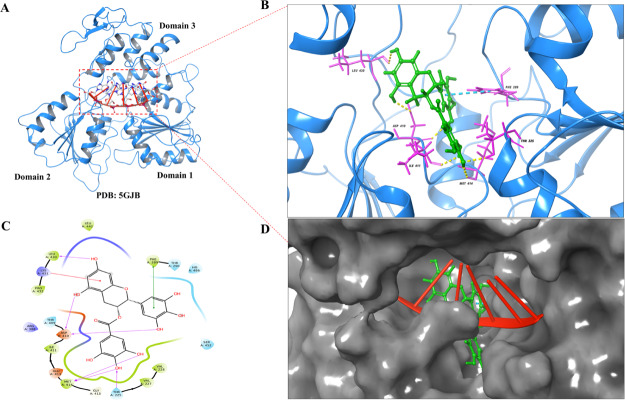

Since for the first time a flavivirus helicase has been co-crystallized with bound ATP at the substrate binding site, this structure seems more significant for the inhibitor screening purpose (Figure 1A). Similarly, another crystal structure has ssRNA bound at the helicase active site which appears suitable for employing in a virtual screening protocol (Figure 2A). We have used extra precision (XP) mode in glide suite of Schrödinger to dock EGCG first at the ATPase site and after that at the helicase site (Figures 1 and 2 respectively). After docking, the extent of EGCG binding at the ATPase site was represented in terms of the docking score, as shown in Table 1. A significant docking score (−7.8 kcal mol–1) was observed which is contributed by various hydrogen bonding interactions with key residues of the ATPase site such as ARG (202), THR (201), GLY (197), ASN (463), and ASN (417) (Figure 1B,C and Table 1). Another important interaction was observed with ARG (462) which shows salt bridge and π–cation bonding with EGCG (Figure 1B,C). More importantly, these interactions were reported at the critical P-loop (residues 193–203) and motif VI (residues Q455, R459, and R462) of the NTPase binding pocket. Mechanistic studies have already shown that P-loop residues play the most significant contribution in NTP binding and further hydrolysis.21,33

Figure 1.

Extra precision (XP) docking of EGCG at the ATPase site of ZIKV NS3 helicase. (A) ZIKV NS3 helicase with PDB ID: 5GJC shows the ATP molecule bound at the NTPase site (red dotted circle) between domain 1 and domain 2. (B) After molecular docking, EGCG exhibits molecular interactions (3D view) by H-bonds (yellow dotted lines), π–cation interactions (green dotted lines), and salt bridges (pink dotted lines). (C) 2D interaction diagram illustrating EGCG binding interactions where interactions are represented as H-bonds (pink arrow), π–cation interactions (solid red line), and salt bridges (blue-red straight line). (D) NS3 helicase is represented as the solid grey surface where docked EGCG (green color) superimposes with the ATP molecule (red color) in the ATPase pocket.

Figure 2.

EGCG molecular docking interactions at RNA binding cavity of ZIKV NS3 helicase. (A) NS3 helicase of ZIKV with PDB ID: 5GJB displays RNA (red color) bound at the interface between domain 1, domain 2, and domain 3 (red dotted square). (B) 3D view of EGCG showing molecular interactions at the RNA binding cavity by H-bonds (yellow dotted lines), π–π interactions (Cyan dotted lines), and π–cation interactions (green dotted lines). (C) 2D interaction diagram of EGCG showing significant interaction displayed as H-bonds (pink arrow), π–cation interactions (red solid line), and π–π stacking (green solid lines). (D) Solid grey surface represented by NS3 helicase and docked EGCG (green color) is superimposed with RNA (red color) bound at the helicase site.

Table 1. Glide (XP) Score and Binding Energy Calculations for EGCG at ATPase and RNA Binding Sites.

| active sites | compound | docking score (kcal mol–1) | binding energy (kcal mol–1) | ligand interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATPase site | EGCG | –7.830 | –47.324 | H-bond: ASN417, ASN463, ARG202, THR201, GLY197; salt-bridge: ARG462; π–cation: ARG462 |

| RNA binding site | EGCG | –7.762 | –51.312 | H-bond: ASP410, LEU430, MET414, THR225; π–π stacking: PHE289; π–cation: LYS431 |

Further, EGCG was also docked at the RNA binding cavity (Figure 2) of NS3 helicase. EGCG exhibited almost a similar docking score (−7.762) like the dock score at ATPase site (Table 1). In Figure 2B,C, EGCG was found to interact with the RNA binding site where residues ASP 410, MET 414, LEU 430, and THR 225 were found to interact through H-bonding with EGCG and residues LYS 431 and PHE 289 were found to show π–cation and π–π stacking interactions, respectively. From Figure 2D, it can be interpreted that EGCG is bound at the entry site of the RNA molecule. Thus, it could probably interfere with the helicase activity also. The residues involved in the interaction with EGCG have been shown to play an essential role in RNA binding and helicase function.21 From our docking studies, it is clear that EGCG has the potential to bind at both sites on NS3 helicase with significant interactions.

Binding Energy Calculation and ADME Properties

Binding energy calculations for ligand binding at protein active sites were estimated by a molecular mechanics-based approach (MM-GBSA) which employs the forcefield methods to analyze the difference in free energies of the ligand, protein, and the complex. The glide XP docking poses of EGCG and helicase protein at both binding sites (NTPase and RNA binding site) were used for estimating the binding energies by using the Prime suite. In Table 1, binding energies for EGCG at the RNA binding site (−51.312 kcal/mol) are shown, which seem slightly higher than those at the ATPase site (−47.324 kcal/mol). These results show that the EGCG molecule can bind at both active sites of NS3 helicase. Further, ADME properties for EGCG molecules were calculated, as reported previously by Sharma et al., (2017).17 Except for a low oral absorption value, the rest of the ADME properties of EGCG were within the range to declare this molecule as a safe drug candidate. In support of this, a study on cell lines has reported that EGCG is starting to show cytotoxicity at concentrations greater than 200 μM.16

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

EGCG Complex at the NTPase Site

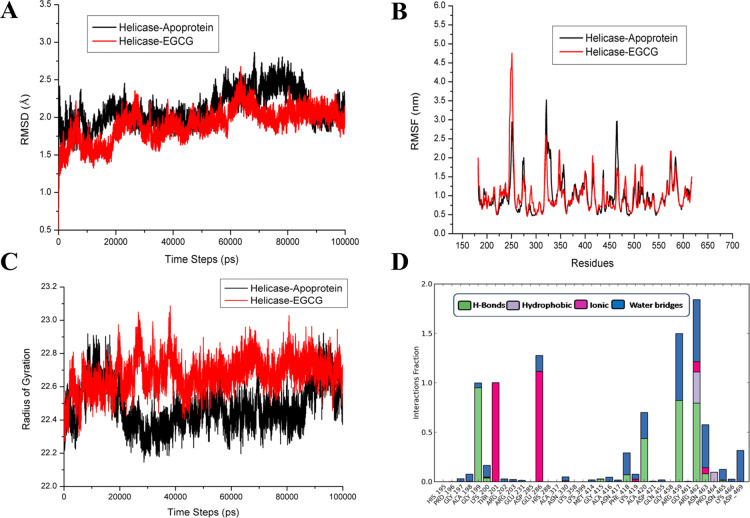

Molecular dynamics simulation studies help in understanding the protein structure–function such as folding, conformational flexibility, and stability. Hence, we have performed the MD simulations on the apo ZIKV helicase and compared the protein stability when EGCG is bound at the NTPase site and RNA binding site for a period of 100 ns (Figures 3 and 4, respectively). In Figure 3A, the analysis of C-α root mean square deviations (rmsd) portrays that the relative stabilitites of apo ZIKV helicase (rmsd = 1.75–2.75 Å) do not vary significantly when compared to the EGCG–NTPase complex represented in red (rmsd = 1.5–2.25 Å).

Figure 3.

Molecular dynamics simulation of the EGCG complex with the ATPase site of ZIKV helicase. (A) rmsd graph of the apo protein helicase and the helicase complex with EGCG at the NTPase site for the time period of 100 ns simulation. (B) Comparison of RMSF graph of Cα of the Apo protein helicase and helicase complex with EGCG at the NTPase site for the time period of 100 ns simulation. (C) Comparison plot of radius of gyration of apo-NS3 helicase and EGCG complex with helicase (D) histogram displaying different types of interaction fractions between EGCG and ATPase site of helicase during the simulation period.

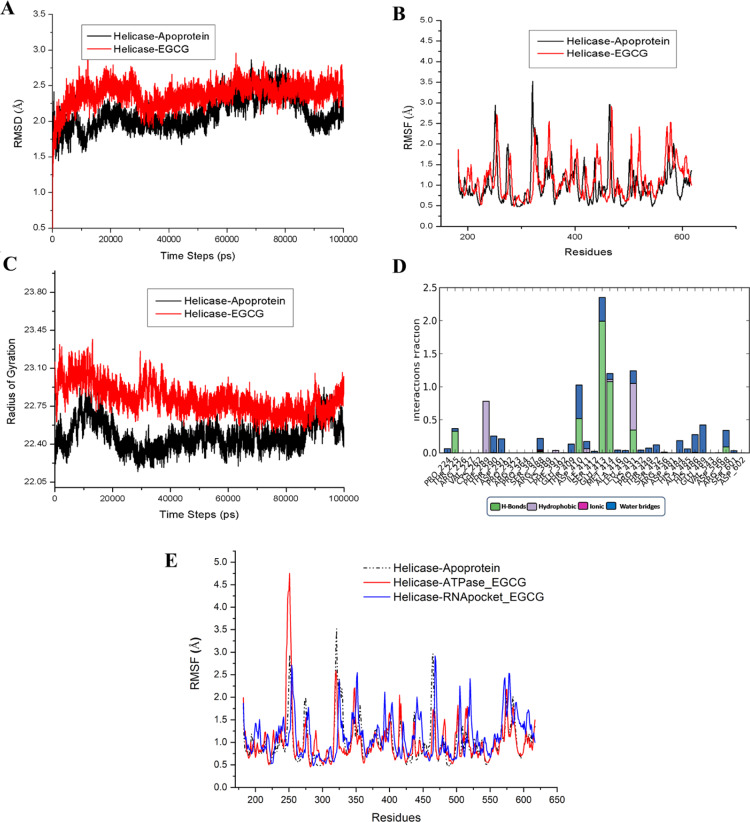

Figure 4.

Molecular dynamics simulation of the EGCG complex with the RNA binding site of ZIKV helicase. (A) rmsd graph of the apo protein helicase and helicase complex with EGCG at the RNA binding site for the time period of 100 ns simulation. (B) Comparison of RMSF graph of Cα of the Apo protein helicase and helicase complex with EGCG at the RNA binding site for the time period of 100 ns simulation. (C) Comparison plot of radius of gyration of apo-NS3 helicase and EGCG complex with helicase. (D) Histogram displaying different types of interaction fractions between EGCG and RNA binding site of helicase during the simulation period. (E) Comparison plot of RMSF was made between, EGCG-ATP site (red color), EGCG-RNA site (blue color), and apo-helicase (black color).

Initially, the EGCG complex exhibited similar fluctuations like apo helicase but after 65 ns, the complex was observed to achieve its stability until the completion of the simulation course period. The conformational fluctuations upon EGCG binding at the NTPase pocket and C-α root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) at the single residue level were compared between apo helicase and the complex (Figure 3B). In Figure 3B, it was observed that the region around 248–255 exhibited higher fluctuations of 4.75 Å in the EGCG complex and lower fluctuations of 2.75 Å were monitored in regions 320–326 in the EGCG complex, as compared to apo helicase. Notably, the studies have shown that the region 248–255 belongs to a RNA binding loop (244–255), which is highly dynamic and stabilized after RNA binding.21,34 Interestingly, it was noticed that the P-loop region (193–203) did not exhibit fluctuations in the EGCG complex and apo helicase as well. Because the dynamic P-loop is critical for ATP hydrolysis, it may be speculated that EGCG stabilizes the P-loop dynamics by forming significant interactions with key residues, as observed in the simulation interaction diagram (Figure S1C). In Figure 3C, compactness of the protein structure was measured by comparing the radius of gyration (Rg) in apo helicase and the EGCG complex. It was observed that the compactness of protein was maintained stably throughout 100 ns simulation period in the EGCG complex as compared to the apo helicase. This also shows that the dynamic NTPase site is also controlling the overall shape of the protein and EGCG is probably stabilizing the NTPase site that further maintains the overall compactness. Further, the analysis of secondary structure elements (Figure S1A) revealed that the region 180–185, 300–310, 330–350, and 450–470 shows an unstable conformation throughout the simulation time. In our previous study, these regions have been predicted to have higher intrinsic disorder propensity and are flexible.22 More deeply, in Figure S1B, the timeline of percentage index of total contacts is provided, and the analysis revealed that ARG 462, THR 201, GLU 286, and ARG 459 had retained the contacts throughout the simulation period. In Figure 3D, the interaction histogram in combination with the 2D simulation interaction diagram (Figure S1D) is shown as a fraction of different interactions (H-bond, hydrophobic, ionic, and water bridges) between EGCG and NTPase site residues. It was observed that residues GLU 286 and THR 201 have ionic interaction contribution of 100%, while ARG 462, ARG 459, and GLY 199 shows the hydrogen bond interaction of more than 70% of the simulation time. Figure 1C shows that the H-bonding is retained throughout the simulation time. Interestingly, the metal ion Mn2+ which is essential for NTP hydrolysis showed significant interaction with a negatively charged oxygen atom of EGCG (Figure S1C). In the meanwhile, the Mn2+ ion also interacts with the GLU 286 and THR 201 residues of the protein. The role of metal ion Mn2+ has already been established in the NTP hydrolysis cycle which helps to stabilize the NTP during the pre-hydrolysis step.33 Overall, EGCG has shown significant interactions with crucial residues of the P-loop (THR 201 and GLY 199) and also with motif VI (residues ARG 459 and ARG 462) of the NTPase binding pocket.

EGCG Complex at the RNA Binding Site

In our docking studies, we have observed that EGCG can also bind to the RNA binding cavity near the entry site with significant interactions (Figure 2 and Table 1). Therefore, we have run MD simulations for apo helicase and the EGCG complex at the RNA binding site to compare the overall protein stability and residue level interactions (Figures 4 and S2). The rmsd graph (Figure 4A) revealed that the apoprotein exhibited deviation upto 20 ns and attained a stable trajectory after 20 ns until it reached 50 ns, whereas after 55 ns, the deviation gradually increased by rmsd of 2.5 Å. In case of the EGCG complex at the RNA binding site, the deviation of the complex started increasing upto 2.5 Å until 25 ns and thereafter a decrease in rmsd (2.2 Å) was observed and maintained throughout the 100 ns period.

The graph shows that EGCG binding at the RNA site stabilizes the overall protein conformation. In Figure 4B, the comparison of RMSF revealed that higher fluctuations of almost 3.5 Å were observed in regions 320–326 in apo helicase, which were further reduced to 2.0 Å in the EGCG-RNA site complex. Interestingly, it was noticed that regions 248–255 exhibited higher fluctuations of 4.75 Å in the EGCG complex at the NTPase site (Figure 3B) in comparison to the EGCG complex at the RNA site (Figure 4B) which showed similar fluctuations of 2.75 Å like apo helicase. Overall, the RMSF plot of the EGCG-RNA site complex was found to support the rmsd graph. As already mentioned, regions 248–255 contain a crucial RNA binding loop which is important for helicase activity.21 From the above comparisons, it may be interpreted that EGCG binding at the NTPase site may lead to the conformational changes at the RNA binding loop region (244–255) which otherwise were not observed when EGCG was bound at the RNA site. In order to track the dynamics of protein more closely, we have compared the RMSF of the EGCG–NTPase site with the EGCG-RNA site and apo-helicase (Figure 4E). It was observed that EGCG binding at the RNA site induces a complete reorganization of the dynamic features of the protein structure as compared to the EGCG–NTPase complex (Figure 4E). In our previous study, the most dynamic regions in helicase were predicted to have higher intrinsic disorder propensities in the P-loop region and comparatively lesser in the R-loop region.22 However, the RMSF data display the R-loop (244–255) region to possess higher fluctuations than the P-loop region in apoprotein (Figure 4E). After EGCG is bound to ATP, a higher fluctuation can be observed at the R-loop region as compared to the P-loop region in the EGCG complex at the RNA site. Also, the EGCG–RNA complex could induce some fluctuations at the P-loop region (197–203) as compared to the EGCG–NTPase complex and apoprotein (Figure 4E). The aforementioned comparison shows that helicase active sites exploit the intrinsic disorder for substrate recognition and binding, and ultimately, the coupled action is executed.

Further, in Figure 4C, the radius of the gyration plot shows that the EGCG complex at the RNA site had maintained the compactness throughout the 100 ns period as compared to apo helicase. In Figure 4D, the different types of interaction fractions were observed that showed that mostly H-bonded interactions were prominent between EGCG and protein. In Figure S2A, the extent of formation of secondary structure elements was analyzed when EGCG bound to the RNA site throughout the 100 ns simulation period. Further, it was noticed that H-bonding was maintained throughout the simulation (Figure S2C), and mostly residues GLU 413 and MET 414 were continuously in contact throughout while residues LYS 431, PHE 289, and ASP 410 showed irregular contacts (Figure S2B,D). These residues observed in the interaction with EGCG at the RNA site have an essential role already mentioned in the crystal structure of helicase with RNA.21 For example, LYS410 and ASP410 shows an important interaction with RNA sugar bases. Hence, our simulation study shows that EGCG may have the capability to significantly bind at the RNA site too along with the NTPase site.

In Vitro Experiments

Inhibition of NTPase Activity

NTPase activity inhibition by EGCG has already been reported in the literature against bacterial DNA gyrases.35 Our molecular docking and simulation studies have shown that EGCG can bind to both the active sites (NTPase and RNA binding site) of ZIKV NS3 helicase with significant interactions between critical residues. Because NTP hydrolysis provides the required energy to open up RNA secondary structures during replication, we first focused on the NTPase activity inhibition assays experimentally.

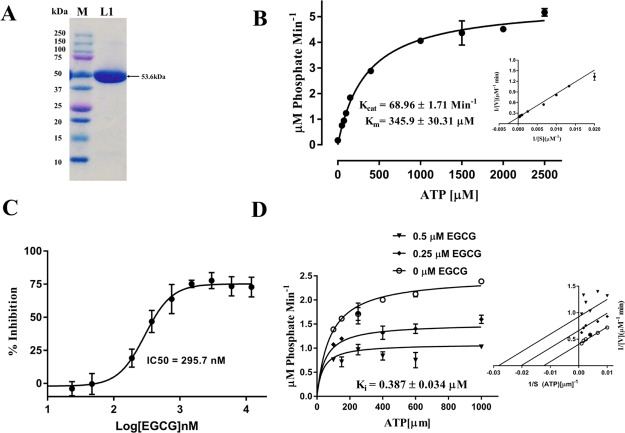

The E. coli-expressed recombinant NS3 helicase (53.6 kDa) was purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography, as shown in Figure 5A. ATPase activity of NS3 helicase was determined by the absorbance (630 nm)-based malachite green method which estimates the release of free phosphate.32 The Michaelis–Menten equation was used to quantitate the kinetic parameters (Km, Kcat, and Kcat/Km) for NTPase activity of NS3 helicase. Km, Kcat, and Kcat/Km were calculated as 345.9 ± 30.31 μM, 68.96 ± 1.71 min–1, and 0.1993 ± 0.056 μM–1 min–1, respectively (Figure 5B). Inhibition assays were carried out in triplicates, and the enzyme is preincubated for 10 min with varying concentrations of EGCG. Further, we have observed the dose-dependent inhibition of NTPase activity, and IC50 values were calculated as 295 nM against the NTPase site (Figure 5C). Additionally, the inhibitory potential of EGCG was determined using substrate velocity curves which showed inhibitory constant (Ki) of 0.387 ± 0.034 μM (Figure 5D). The binding mode suggested is uncompetitive, although surprising if compared to the prediction data. However, this could be due the limitation of lower detection limit of colorimetric assay. However, these result shows that the EGCG molecule is quite capable of inhibiting NTPase activity of NS3 helicase in the low micromolar range and could act as a potential leading backbone molecule for further inhibitor development.

Figure 5.

EGCG inhibits ATPase activity of NS3 helicase. (A) Purification of NS3 helicase by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. A 10% SDS gel was run and stained with Coomassie dye where final his-tagged NS3 helicase fractions were pooled and concentrated by an Amicon (10 kDa) centrifugal filter. In this figure, M-protein ladder (Bio-Rad Precision Plus) and L1 contains purified concentrated his-tagged NS3 helicase protein of ZIKV. (B) Kinetic parameters (substrate–velocity curve) calculated for 80 nM NS3 helicase after varying the substrate (ATP) concentration ranging from 50 to 2500 μM. (C) IC50 calculated for EGCG against the NTPase site by incubating 80 nM helicase with varying concentration of EGCG (serially diluted: 1200 nM: 23.40 nM). (D) Inhibition constant (Ki) was calculated for 80 nM helicase at different concentrations of ATP (100, 150, 250, 400, 600, and 1000 μM), and EGCG concentrations were kept at 0.5 and 0.25 μM.

Discussion

In recent years, repeated outbreaks of ZIKV have necessitated the urgent need for developing specific drugs. Also, the major complications of ZIKV infections are related to pregnant women; therefore, it is important to find molecules which are safe and have minimal or no side-effects. Considering the safety point, natural products have always been a great source of drugs or drug like molecules and also these molecules have evolutionary pre-optimized biological targets.8 To find specific biological targets, in silico structure-based drug discovery approaches have revolutionized and fasten the current drug developing strategies. In fact, the molecules which can target specifically viral proteins could act as safe therapeutics against ZIKV.36 EGCG, a green tea polyphenol, has shown significant antiviral activity against several viruses including HIV, HSV, and CHIKV and some flaviviruses like HCV and DENV.10 Recently, in ZIKV, EGCG inhibitory potential was determined in a cell line-based study where the probable mechanism was related to the interaction of the compound with the envelope protein.16 Previously, we have also supported the EGCG envelope protein interaction with computational study.17 However, reports suggested that EGCG may target other viral proteins which are important in genome replication and maturation.10 Because of lack of adequate experimental support regrading EGCG envelope protein interactions and considering the possibility of finding more specific target for EGCG, we have chosen NS3 helicase protein of ZIKV for determining potential inhibitory effects of EGCG. NS3 helicase of ZIKV is an attractive drug target because of its essential role in opening RNA secondary structures during replication.21 Also, reports suggest that EGCG has shown anti-ATPase activity against bacterial DNA gyrases.35

It is a well-known fact that flavivirus helicases are motor proteins and require energy released from NTP hydrolysis to perform their helicase function.37 Therefore, first, we analyzed EGCG affinity toward the NTPase site through docking, binding energy calculation, and MD simulations. These studies revealed that EGCG can dock significantly with key residues (ARG 202, THR 201, GLY 197, ASN 463, and ASN 417) at the NTPase site and further MD simulations were supporting the stable EGCG interaction with residues (Mn2+, ARG 462, THR 201, GLU 286, and ARG 459) were carried out throughout the simulation period (100 ns). In our previous study, these residues have been predicted to have intrinsic disorder propensity.22 Also, the NTPase pocket residues interacting with EGCG are mostly arginine, lysine, and glutamic acids which have been classified in the category of disorder-promoting amino acids.38,39 In the crystal structure of ZIKV NS3 helicase with bound ATP, these intrinsically disordered residues have significant functions such as the Mn2+ co-ordination with GLU 286 stabilizes the ATP molecule and the P-loop residues (GLY 197, ARG 202, and LYS 200) and motif VI residues (ARG 459 and ARG 462) play key roles in NTP hydrolysis by interacting with transition state nucleotides.21 Recently, a mutational study has shown that residues THR 201, ARG 202, and GLU 286 are critical for NTP hydrolysis by ZIKV NS3 helicase.33 Also, a compound NITD008 was shown to inhibit ZIKV replication experimentally where the mechanism was elucidated computationally to show binding at the NTPase site with significant interactions at the P-loop region.40 Based upon computational findings, we have done inhibition assays where EGCG has shown significant dose-dependent inhibition of NTPase activity with IC50 of 295.7 nM by the Malachite green method. Further, the mode of inhibition was determined to be uncompetitive with inhibition constant (Ki) in a low micromolar range (Ki = 0.387 ± 0.034 μM). A study of polyphenols inhibiting ZIKV protease has shown that EGCG inhibits protease with higher IC50 (87 μM) values.41 Taken together, our findings suggest that EGCG may target ZIKV helicase more specifically in addition to envelope protein and NS3 protease.

In ZIKV NS3 helicase, the RNA binding site along with the NTPase site has considerable flexible or intrinsically disordered pockets containing critical loop regions needed to perform the function.21,22 Therefore, we also studied the possibility of EGCG interaction at the RNA binding site. This was due to the fact that polyphenols have shown potential interactions with intrinsically disordered regions in proteins and could be seen as novel strategies of drug development against IDPs.42 Also, literature has shown that viral proteins have several short stretches of disordered regions within proteins and more propensity of intrinsically disordered active sites.22,24,43 Our docking and MD simulations studies demonstrate that EGCG has the ability to bind at the entry site of RNA binding pocket with significant interactions. More specifically, EGCG exhibits different types of interactions (H-bond, ionic, and salt bridge) with residues GLU 413, MET 414, LYS 431, PHE289, and ASP 410. In the crystal structure, these residues play a key role in binding to RNA.21 Also, the residues like glutamic acid, lysine, and aspartic acid are categorized as disorder-promoting amino acids, and in our previous disorder analysis of NS3 helicase, the regions 410–460 have shown high propensity of the intrinsic disorder.22,39 In our MD simulations, it has also been reported that EGCG binding at the NTPase site increases fluctuations in the RNA site which could be interpreted as an allosteric relationship between two sites. This observation could be supported by the recent study on DENV helicase where NTPase and RNA sites show allosteric effects.

In summary, our extensive docking and simulation analysis demonstrate that EGCG can bind strongly to the NTPase site and can inhibit the activity of ZIKV NS3 helicase more precisely, supported by in vitro enzyme kinetics assays. Also, EGCG can form significant binding interactions at the RNA site, as revealed by computational tools. Interestingly, the comparison with previous studies demonstrates that EGCG can target multiple viral proteins such as envelope,16 protease,41 and now more precisely helicase. Because EGCG has shown the virucidal effect against several viruses, the EGCG backbone could be used to develop a broad-spectrum antiviral molecule in near future.

Materials and Methods

In Silico Docking Studies

In-silico studies were carried out on an X-ray crystal structure (PDB ID: 5GJC, resolution 2.2 Å) of NS3 helicase bound to ATP-Mn2+ and the crystal structure containing bound ssRNA with PDB ID: 5GJB (1.7 Å). Further, the docking process was initiated by following a series of necessary steps such as protein preparation, receptor grid generation, ligand preparation, and finally ligand docking. Protein preparation was carried out by using Protein Preparation wizard in Schrodinger LLC Maestro v11.0. In protein preparation, force field OPLS-2005 was utilized for H-bond network optimization and energy minimization. Co-crystallization artifacts such as missing side chains and loops were filled by using Prime. Protonation states were generated using Epik at pH 7.4. In the literature, three crystal water molecules were reported at the substrate binding site; therefore except for these water molecules, rest were deleted beyond 5 Å from the ligand. A receptor grid was generated on the centroid of the substrate binding site by picking up the atoms of the co-crystallized ligand (ATP) in 5GJC and ssRNA in 5GJB. The length of the grid was kept 20 Å. Before the final docking step, the EGCG molecule was also prepared using LigPrep module of Maestro, as described by Sharma et al. Further, ligand docking was carried out by using extra precision glide (Glide XP) program from Schrodinger (Glide, Version 11). The EGCG molecule was docked flexibly at the rigid active site on the protein. Final XP dock scores were analyzed for significant interactions with active site residues.

Binding Energy Calculation and ADME Properties

The prime/MM-GBSA approach was used to calculate the free energy of binding for the XP docked complex. This method was utilized as described previously by Sharma et al., (2017).17 MM/GBSA is an empirical scoring that approximates the ligand binding affinities with the receptor. Following equation is used for calculating the free energy of binding

QikProp module of Schrödinger software (QikProp, version 4.3, Schrodinger) was used for the calculation of the drug like behavior through the evaluation of the pharmacokinetic properties that are required for the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME).17 These properties have been calculated already in our previous study.17

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Molecular dynamics simulation was executed for the apoprotein and complex of ZIKA helicase with EGCG at the NTPase site and RNA binding site using the Desmond module implemented in Schrodinger(a). The OPLS-AA (optimized potentials for liquid simulations—all atom) 2005 force field was used for the minimization of the complex and apoprotein.44 The structures of the protein and complex were imported in the Desmond setup wizard and were solvated in a cubic periodic box of TIP3P water molecules. The structures were neutralized by adding a suitable number of counter ions and 0.15 M of salt concentration.45 Steepest descent, a hybrid method is implemented for the local energy minimization of the system. The limited memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno algorithm with a maximum of 5000 steps is used until a gradient threshold (25 kcal/mol/Å) was reached. The constant NPT (number of atoms, pressure P, and temperature T) ensemble condition is incorporated to relax the simulation system to generate simulation data for post analyses. The overall simulation process is performed using the Nose–Hoover thermostats, and stable atmospheric pressure (1 atm) was carried out by the Martina–Tobias–Klein barostat method, and 300 K was assigned as the temperature value. In order to investigate the equation of motion throughout the dynamics, the multi-time step RESPA integrator algorithm was used.46,47 The bonded, near non-bonded, and far non-bonded interactions were assigned at the time steps of 2, 2, and 6 fs, respectively. The atoms involved in the hydrogen bond interaction were constrained with the SHAKE algorithm. A cut-off value of 9 Å radius was set up to estimate the long-range electrostatic interactions and Lennard-Jones interactions. The Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method was used to evaluate the long-range electrostatic interactions along with the simulation process using the periodic boundary conditions (PBC). During the intervals of 1.2 and 4.8 ps, the trajectory data and the energy analysis were recognized. The final production of molecular dynamics was carried out for 100 ns for both apoprotein and the protein complex. The results were analyzed using the simulation event analysis and simulation interaction diagram available in Desmond module.48

In Vitro Experiments

Cloning, Expression, and Purification

The ZIKV NS3 helicase coding region (1342 bp) corresponding to PDB ID: 5GJC was synthesized by GeneArt Gene synthesis services provided by Invitrogen (USA). This gene was further ligated into pET 151/D-TOPO vector purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA). The final construct containing N-terminal 6X-His tag with the TEV protease cleavage site was transformed into BL21 (Sigma) E. coli cells, and thereafter, positive clones were expressed in LB broth media (inducing with 1 mM IPTG at 20 °C overnight). Cells containing recombinant protein were harvested by centrifugation at 6000g at 4 °C and re-suspended in binding buffer (50 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol pH 8.0). Protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was added before cell lysis. Cells were lysed by sonication and adding 50% B-PER (Thermo scientific) reagent. After centrifugation at 16,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C, the supernatant containing recombinant protein was filtered and loaded on a HisTrap FF 5 mL column (GE healthcare). Recombinant protein was eluted by using a linear imidazole gradient from 0 to 100%. Eluted fractions were analyzed on 10% SDS-PAGE for purity. Buffer exchange was carried out to remove the Imidazole by using Amicon 10 kDa (Merck Millipore) centrifugal filters. Recombinant protein was kept in storage buffer (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol) stored in aliquots at −80 °C.

NTPase Activity Assay

The NTPase activity of recombinant NS3 helicase was analyzed by using a malachite green method, as described previously in the literature.49,50 We have slightly modified the ratio of reagents as follows: 1 mg/mL malachite green, 2 mg/mL ammonium molybdate, 0.7 M HCl, and 0.05% Triton X-100. All the reagents were prepared in ultrapure water ensuring that there is no phosphate contamination. A blank sample O.D. below 0.3 at 630 nm (TECAN infinite M200 PRO) confirms the phosphate-free assay system. A phosphate standard curve (serially diluted 6.25–100 μM) was prepared (40 μL sample + 160 μL Malachite reagent) which is used further to quantitate the amount of free phosphate released by NS3 helicase. In 96-well micro-plate assay, NS3 helicase was pre-incubated in duplicates at a concentration of 80 nM in 20 μL assay buffer (40 mM Tris, 80 mM NaCl, 8 mM Mg(AcO)2, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5). The NTP hydrolysis reaction was started after adding 10 μL ATP in varying concentrations from 25 to 2500 μM. The final sample volume was kept 40 μL, and after 20 min of incubation at 25 °C, the reaction was terminated by adding 160 μL of malachite reagent. After incubating the reaction at room temperature for 5 min, absorbance was measured at 630 nm. All the kinetic parameters were calculated by plotting the data in GraphPad Prims software 7.0. The data fitting was done using the Michaelis–Menten equation (V = Vmax[S]/(Km + [S])) to calculate kinetic parameters (Vmax, Km and Kcat).

NTPase Activity Inhibition Assay

Inhibition assays were carried out in similar buffer conditions as used in activity assay. EGCG (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in water at a stock concentration of 5 mM. Inhibition assay was carried out in triplicates in a 96 well plate. Initially, 80 nM enzyme is pre-incubated with a varying concentration of EGCG (serially diluted: 12,000–23.40 nM) in an assay buffer at 25 °C for 10 min. After incubation, 1 mM ATP substrate was added to the wells and incubated for 20 min. Finally, the reaction was stopped by adding 160 μL malachite green reagent to all the wells. Absorbance was taken at 630 nm after 5 min. The IC50 value was calculated by fitting the data in non-linear regression mode using GraphPad Prism 7.0. Further, the inhibition kinetic parameters were calculated at different ATP concentrations as 100, 150, 250, 400, 600, and 1000 μM. Two concentrations of EGCG were chosen in 40 μL sample volume as 0.5 and 0.25 μM, which are above and below from the IC50 value. For all the reactions, 80 nM enzyme was pre-incubated in assay buffer with different EGCG concentrations for 10 min. Afterward, ATP was added in varying concentrations as mentioned above and incubated for 20 min. Malachite reagent (160 μL) was added in each well, and absorbance was taken at 630 nm after 5 min. All the measurements were taken in triplicates, and Ki (Inhibition constant) was determined after fitting data in GraphPad Prism 7.0.

Acknowledgments

R.G. acknowledges DBT grant, India (BT/11/IYBA/2018/06), for partially supporting this work. D.K. is grateful for ICMR fellowship, India. R.G. also acknowledges the MHRD-SPARC grant (SPARC/2018-2019/P37/SL). N.S. is thankful for MHRD fellowship.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c01353.

Analysis of parameters of MD simulation of the EGCG complex at the NTPase site and RNA binding site, timeline of the content of secondary structure elements during 100 ns simulation, percentage analysis of total contacts, hydrogen bond analysis, and simulation 2D interaction diagrams (PDF)

Author Contributions

R.G.: conception, design, and study supervision and D.K., N.S., M.A., and S.K.S. D.K.: acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, writing, and review of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Stawicki S. P.; Sikka V.; Chattu V. K.; Popli R. K.; Galwankar S. C.; Kelkar D.; Sawicki S. G.; Papadimos T. J. The Emergence of Zika Virus as a Global Health Security Threat: A Review and a Consensus Statement of the INDUSEM Joint Working Group (JWG). J. Global Infect. Dis. 2016, 8, 3–15. 10.4103/0974-777X.176140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikan N.; Smith D. R. Zika Virus: History of a Newly Emerging Arbovirus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, e119–e126. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30010-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetro J. A. Zika and Microcephaly: Causation, Correlation, or Coincidence?. Microbes Infect. 2016, 18, 167–168. 10.1016/j.micinf.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musso D.; Nilles E. J.; Cao-Lormeau V.-M. Rapid Spread of Emerging Zika Virus in the Pacific Area. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, O595–O596. 10.1111/1469-0691.12707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musso D.; Roche C.; Robin E.; Nhan T.; Teissier A.; Cao-Lormeau V.-M. Potential Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 359–361. 10.3201/eid2102.141363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiz J.-C.; Martín-Acebes M. A. The Race To Find Antivirals for Zika Virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00411–17. 10.1128/aac.00411-17ss. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F.; Murray J. L.; Rubin D. H. Drug Repurposing: New Treatments for Zika Virus Infection?. Trends Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 919–921. 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B. A New Golden Age of Natural Products Drug Discovery. Cell 2015, 163, 1297–1300. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J. P.; Sasse F.; Brönstrup M.; Diez J.; Meyerhans A. Antiviral Drug Discovery: Broad-Spectrum Drugs from Nature. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 29–48. 10.1039/C4NP00085D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Xu Z.; Zheng W. A Review of the Antiviral Role of Green Tea Catechins. Molecules 2017, 22, 1337. 10.3390/molecules22081337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nance C. L.; Siwak E. B.; Shearer W. T. Preclinical Development of the Green Tea Catechin, Epigallocatechin Gallate, as an HIV-1 Therapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 123, 459–465. 10.1016/J.JACI.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calland N.; Albecka A.; Belouzard S.; Wychowski C.; Duverlie G.; Descamps V.; Hober D.; Dubuisson J.; Rouillé Y.; Séron K. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Is a New Inhibitor of Hepatitis C Virus Entry. Hepatology 2012, 55, 720–729. 10.1002/hep.24803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.-M.; Lee K.-H.; Seong B.-L. Antiviral Effect of Catechins in Green Tea on Influenza Virus. Antiviral Res. 2005, 68, 66–74. 10.1016/J.ANTIVIRAL.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber C.; Sliva K.; von Rhein C.; Kümmerer B. M.; Schnierle B. S. The Green Tea Catechin, Epigallocatechin Gallate Inhibits Chikungunya Virus Infection. Antiviral Res. 2015, 113, 1–3. 10.1016/J.ANTIVIRAL.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail N. A.; Jusoh S. A. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Studies to Predict Flavonoid Binding on the Surface of DENV2 E Protein. Interdiscip. Sci.: Comput. Life Sci. 2017, 9, 499–511. 10.1007/s12539-016-0157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro B. M.; Batista M. N.; Braga A. C. S.; Nogueira M. L.; Rahal P. The Green Tea Molecule EGCG Inhibits Zika Virus Entry. Virology 2016, 496, 215–218. 10.1016/j.virol.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N.; Murali A.; Singh S. K.; Giri R. Epigallocatechin Gallate, an Active Green Tea Compound Inhibits the Zika Virus Entry into Host Cells via Binding the Envelope Protein. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 1046–1054. 10.1016/J.IJBIOMAC.2017.06.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H.; Ji X.; Yang X.; Xie W.; Yang K.; Chen C.; Wu C.; Chi H.; Mu Z.; Wang Z.; et al. The Crystal Structure of Zika Virus Helicase: Basis for Antiviral Drug Design. Protein Cell 2016, 7, 450–454. 10.1007/s13238-016-0275-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R.; Coloma J.; García-Sastre A.; Aggarwal A. K. Structure of the NS3 Helicase from Zika Virus. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 752. 10.1038/nsmb.3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briguglio I.; Piras S.; Corona P.; Carta A. Inhibition of RNA Helicases of SsRNA + Virus Belonging to Flaviviridae, Coronaviridae and Picornaviridae Families. Int. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 2011, 1–22. 10.1155/2011/213135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H.; Ji X.; Yang X.; Zhang Z.; Lu Z.; Yang K.; Chen C.; Zhao Q.; Chi H.; Mu Z.; et al. Structural Basis of Zika Virus Helicase in Recognizing Its Substrates. Protein Cell 2016, 7, 562–570. 10.1007/s13238-016-0293-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri R.; Kumar D.; Sharma N.; Uversky V. N. Intrinsically Disordered Side of the Zika Virus Proteome. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 144. 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri R.; Morrone A.; Toto A.; Brunori M.; Gianni S. Structure of the Transition State for the Binding of C-Myb and KIX Highlights an Unexpected Order for a Disordered System. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 14942–14947. 10.1073/pnas.1307337110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue B.; Blocquel D.; Habchi J.; Uversky A. V.; Kurgan L.; Uversky V. N.; Longhi S. Structural Disorder in Viral Proteins. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6880–6911. 10.1021/cr4005692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toto A.; Giri R.; Brunori M.; Gianni S. The Mechanism of Binding of the KIX Domain to the Mixed Lineage Leukemia Protein and Its Allosteric Role in the Recognition of C-Myb. Protein Sci. 2014, 23, 962–969. 10.1002/pro.2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D.; Sharma N.; Giri R. Therapeutic Interventions of Cancers Using Intrinsically Disordered Proteins as Drug Targets: C-Myc as Model System. Cancer Inf. 2017, 16, 1176935117699408. 10.1177/1176935117699408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra P. M.; Uversky V. N.; Giri R. Molecular Recognition Features in Zika Virus Proteome. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 2372. 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianni S.; Morrone A.; Giri R.; Brunori M. A Folding-after-Binding Mechanism Describes the Recognition between the Transactivation Domain of c-Myb and the KIX Domain of the CREB-Binding Protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 428, 205–209. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.09.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toto A.; Camilloni C.; Giri R.; Brunori M.; Vendruscolo M.; Gianni S. Molecular Recognition by Templated Folding of an Intrinsically Disordered Protein. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21994. 10.1038/srep21994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Liang B.; Aarthy M.; Singh S. K.; Garg N.; Mysorekar I. U.; Giri R. Hydroxychloroquine Inhibits Zika Virus NS2B-NS3 Protease. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 18132–18141. 10.1021/acsomega.8b01002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D.; Aarthy M.; Kumar P.; Singh S. K.; Uversky V. N.; Giri R. Targeting the NTPase Site of Zika Virus NS3 Helicase for Inhibitor Discovery. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 1–11. 10.1080/07391102.2019.1689851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayank; Kumar D.; Kaur N.; Giri R.; Singh N. A Biscoumarin Scaffold as an Efficient Anti-Zika Virus Lead with NS3-Helicase Inhibitory Potential: In Vitro and in Silico Investigations. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 1872–1880. 10.1039/C9NJ05225A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.; Chen C.; Tian H.; Chi H.; Mu Z.; Zhang T.; Yang K.; Zhao Q.; Liu X.; Wang Z.; et al. Mechanism of ATP Hydrolysis by the Zika Virus Helicase. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 5250–5257. 10.1096/fj.201701140R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramharack P.; Oguntade S.; Soliman M. E. S. Delving into Zika Virus Structural Dynamics – a Closer Look at NS3 Helicase Loop Flexibility and Its Role in Drug Discovery. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 22133–22144. 10.1039/C7RA01376K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gradišar H.; Pristovšek P.; Plaper A.; Jerala R. Green Tea Catechins Inhibit Bacterial DNA Gyrase by Interaction with Its ATP Binding Site. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 264. 10.1021/JM060817O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottin M.; Borba J. V. V. B.; Braga R. C.; Torres P. H. M.; Martini M. C.; Proenca-Modena J. L.; Judice C. C.; Costa F. T. M.; Ekins S.; Perryman A. L.; et al. The A–Z of Zika Drug Discovery. Drug Discovery Today 2018, 23, 1833–1847. 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Bera A. K.; Kuhn R. J.; Smith J. L. Structure of the Flavivirus Helicase: Implications for Catalytic Activity, Protein Interactions, and Proteolytic Processing. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 10268–10277. 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10268-10277.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campen A.; Williams R.; Brown C.; Meng J.; Uversky V.; Dunker A. TOP-IDP-Scale: A New Amino Acid Scale Measuring Propensity for Intrinsic Disorder. Protein Pept. Lett. 2008, 15, 956–963. 10.2174/092986608785849164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky V. N. The Alphabet of Intrinsic Disorder: II. Various Roles of Glutamic Acid in Ordered and Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Intrinsically Disord. proteins 2013, 1, e24684 10.4161/idp.24684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y.-Q.; Zhang N.-N.; Li C.-F.; Tian M.; Hao J.-N.; Xie X.-P.; Shi P.-Y.; Qin C.-F. Adenosine Analog NITD008 Is a Potent Inhibitor of Zika Virus. Open forum Infect. Dis. 2016, 3, ofw175. 10.1093/ofid/ofw175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H.-j.; Nguyen T. T. H.; Kim N. M.; Park J.-S.; Jang T.-S.; Kim D. Inhibitory Effect of Flavonoids against NS2B-NS3 Protease of ZIKA Virus and Their Structure Activity Relationship. Biotechnol. Lett. 2017, 39, 415–421. 10.1007/s10529-016-2261-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Cao Z.; Zhao L.; Li S. Novel Strategies for Drug Discovery Based on Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 3205–3219. 10.3390/ijms12053205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuriki N.; Oldfield C. J.; Uversky V. N.; Berezovsky I. N.; Tawfik D. S. Do Viral Proteins Possess Unique Biophysical Features?. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009, 34, 53–59. 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S.; Yadav S.; Suryanarayanan V.; Singh S. K.; Saxena J. K. Investigating the Folding Pathway and Substrate Induced Conformational Changes in B. Malayi Guanylate Kinase. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 94, 621–633. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirin S.; Pearlman D. A.; Sherman W. Physics-Based Enzyme Design: Predicting Binding Affinity and Catalytic Activity. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 2014, 82, 3397–3409. 10.1002/prot.24694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekaran D.; Sridhar J.; Suryanarayanan V.; Manimaran N. C.; Singh S. K. Molecular Modeling and Structural Analysis of NAChR Variants Uncovers the Mechanism of Resistance to Snake Toxins. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2017, 35, 1654–1671. 10.1080/07391102.2016.1190791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryanarayanan V.; Singh S. K.; Singh S. K. Assessment of Dual Inhibition Property of Newly Discovered Inhibitors against PCAF and GCN5 through in Silico Screening, Molecular Dynamics Simulation and DFT Approach. J. Recept. Signal Transduction 2015, 35, 370–380. 10.3109/10799893.2014.956756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panwar U.; Singh S. K. Structure-Based Virtual Screening toward the Discovery of Novel Inhibitors for Impeding the Protein-Protein Interaction between HIV-1 Integrase and Human Lens Epithelium-Derived Growth Factor (LEDGF/P75). J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2018, 36, 3199–3217. 10.1080/07391102.2017.1384400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama T.; Fukui K.; Kometani K. The Initial Phosphate Burst in ATP Hydrolysis by Myosin and Subfragment-1 as Studied by a Modified Malachite Green Method for Determination of Inorganic Phosphate. J. Biochem. 1986, 99, 1465–1472. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geladopoulos T. P.; Sotiroudis T. G.; Evangelopoulos A. E. A Malachite Green Calorimetric Assay for Protein Phosphatase Activity. Anal. Biochem. 1991, 192, 112. 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.