Abstract

COVID-19 morbidity and mortality is significantly increased in patients with diabetes and kidney disease via unknown mechanisms. SARS-CoV-2 uses angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) for entry into human host cells, and ACE2 levels in target cells may influence SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility. We investigated how pre-existing conditions and drug treatments alter receptor expression in kidney tissue. Using single cell RNA profiling (scRNAseq) to assess ACE2 and associated SARS-CoV-2 proteases in healthy living donors (LD) kidneys, diabetic kidney disease (DKD), and in kidney injury during viral infection, ACE2 expression was primarily associated with proximal tubular epithelial cells (PTEC). ACE2 mRNA expression levels were significantly upregulated in DKD versus LD, however, ACE2 levels were not altered by exposures to renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors. ACE2+ expression signatures were defined by differential expression analysis and characterized by Bayesian integrative analysis of a large compendium of public -omics datasets, resulting in the identification of network modules induced in ACE2 positive PTEC in DKD and BK virus nephropathy. These ACE2 upregulated cell programs were linked to viral entry, immune activation, endomembrane reorganization, and RNA processing and overlapped significantly with the cellular responses induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Similar cellular programs were activated in ACE2-positive PTEC isolated in a urine sample from a COVID19 patient with acute kidney injury, suggesting a consistent ACE2-coregulated expression program that may interact with SARS-Cov-2 infection processes. The SARS-CoV-2 receptor associated gene signatures could seed further research into therapeutic strategies for COVID-19. Functional networks of gene expression signatures are available for further exploration to researchers at HumanBase (hb.flatironinstitute.org/covid-kidney).

Introduction

COVID-19 disproportionally affects individuals with diabetes, hypertension, and kidney disease1–3. Yet the underlying molecular and physiological causes of this association are unknown, and could be as varied as drugs used to treat these conditions4, disease biology5–7, direct infection of relevant organs by the virus8, 9 and consequent tissue destruction, and cytokine storm that occurs secondary to infection1. While upper and lower airway tissues are the primary sites of infection, additional sites are likely to include kidney tissue, and initial data suggest that patients with kidney disease suffer significantly higher mortality than age-matched individuals without these conditions10–12. Understanding the disease-specific molecular processes associated with COVID-19 in patients with kidney disease and diabetes can have a significant impact on public health.

COVID-19 develops from infection with SARS-CoV-2, a betacoronavirus with a single stranded RNA genome. It gains entry into specific cell types through interaction of surface spike protein with a cell surface receptor13. Studies of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in the early 2000s identified angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as the primary cell-entry receptor for the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in humans14, 15. Recent studies from the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrate that ACE2 is also the primary cell-entry receptor for SARS-CoV-213, 16, 17 and, similar to SARS-CoV, higher ACE2 expression may lead to higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection8, 18.

ACE2 is a membrane bound zinc metallopeptidase and a master regulator of the renin-angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS). Normally, ACE2 is expressed as a cell-surface protein to which both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 can bind4, 19. Cleavage of spike protein is required for fusion of the virus with host membranes and occurs in a manner similar to SARS-CoV: TMPRSS2 appears to be the primary means of this activation, at least in lung epithelial cells; however cleavage can also occur in endosomes by acid-activated proteases such as cathepsin L (CTSL)17, 20, 21.

Direct access to SARS-CoV-2 target tissues combined with the granularity of single cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) technology can locate specific cell types with enhanced ACE2 expression to determine whether these cells also possess additional molecular machinery that facilitate initial viral entry and subsequent cellular cytotoxicity. Characterization of these molecular processes in existing tissue from relevant cohorts could greatly accelerate the identification and development of therapeutic options for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In this study, we explored the expression and associated biological processes of ACE2 and other viral co-receptors in kidney cells from healthy living donors (LD), and from patients with diabetic kidney disease (DKD), BK virus nephropathy (BKVN) and COVID-19 associated AKI (COV-AKI). Using scRNAseq data, we defined the cellular expression of ACE2 in proximal tubular epithelial cells (PTEC), characterized the cellular programs associated with ACE2 and its regulation in DKD, BKVN and COV-AKI, mapped the ACE2 associated changes to emerging data on SARS-CoV-2 induced cellular responses and tested the associations with RAAS medication exposure (Figure 1). Our study focused on DKD since COVID-19 disproportionally affects individuals with diabetes and kidney disease1, 3, 7, 11, 22, 23, and research kidney biopsies were available in a comprehensive DKD cohort for scRNAseq profiling and analysis. The DKD analyses could identify underlying mechanisms of excessive risk associated with COVID-19 in patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease, with the studies in BKVN and COV-AKI establishing the link between DKD and virus-associated kidney disease.

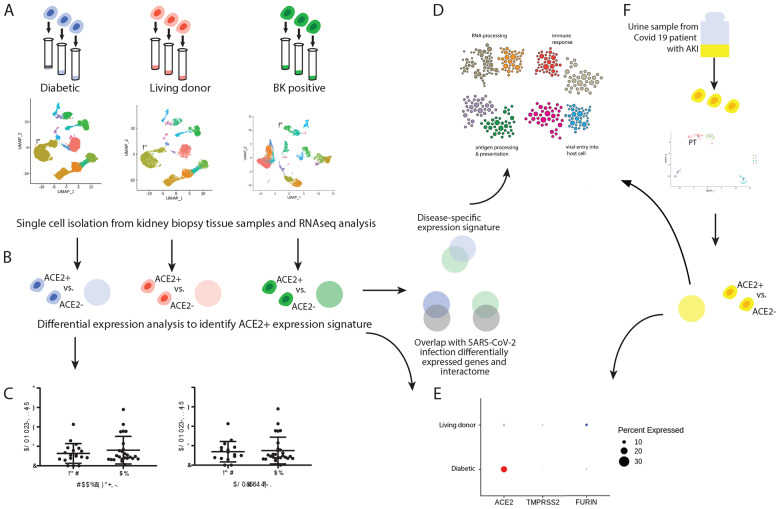

Figure 1. Study overview.

To identify SARS-CoV-2 receptor networks in diabetic kidney disease (DKD), BK-Virus nephropathy (BKVN) and COVID-19 associated acute kidney injury (COV-AKI), we used scRNAseq profiling and integrative analyses. (A) Biopsy samples from DKD, BKVN, All and living donors (LD) were processed for scRNAseq profiling and cell-type clusters were identified from each sample. (B) For each dataset, we identified genes that are differentially expressed in ACE2+ compared to ACE2- proximal cells (PTEC). We compared DKD and BKVN ACE2+ co-expression sets to identify a disease-specific signature, and we also compared each signature to published SARS-CoV-2-relevant gene sets. (C) In parallel, we evaluated the association of ACE2 expression levels with clinical characteristics, including exposure to RAAS blockers and ACE inhibitors in DKD (D) For each ACE2+ co-expression signature, we identified modules in a proximal tubule-specific functional network and found modules enriched with biological processes relevant to viral infection. (E) We compared expression of ACE2 and key proteases between LD and DKD PTEC. (F) Finally, we explored this ACE2+ signature in PTEC cells in BKVN kidney tissue and a COV-AKI urine sample.

Methods

Study Population

DKD biopsy cohort

An early DKD cohort was selected as the discovery cohort given the impact of COVID-19 on individuals with diabetes and kidney disease1, 3, 7, 11, 22, 23. Between 2013 and 2017, 141 American Indians (39 men, 102 women) from southern Arizona with type 2 diabetes were enrolled in an observational study of DKD that included annual research examinations. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was measured at each of these examinations by the urinary clearance of iothalamate24. At baseline, each participant also underwent a research kidney biopsy used for quantitative morphometry and for compartment-specific tissue expression studies. For kidney biopsies conducted in the last 44 participants enrolled between 2016 and 2017, processing of the kidney specimens was modified to enable scRNAseq studies using kidney biopsy tissues. These 44 participants (DKD) were included in the present study.

At each annual research examination, medicines taken by the participants were recorded. Blood pressure (BP) was measured with the participant resting in a seated position, and height and weight were obtained with the participant dressed in light clothing without shoes. Body mass index was defined as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Urine and serum creatinine were measured by an enzymatic method. Urinary albumin excretion was assessed by nephelometric immunoassay and expressed as the albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) in mg/g creatinine. GFR and HbA1c were measured by high performance liquid chromatography. Because of the level of obesity in the participants, absolute GFR (ml/min) was reported, uncorrected for body surface area25.

Clinical and demographic features and the antihypertensive medicines taken by the DKD cohort at the time of the kidney biopsy are shown in Table 1. Participants had mean diabetes duration of 12.2 ± 7.5 years, HbA1c of 9.2 ± 2.4 %, iGFR of 159 ± 58 ml/min with one patient GFR <60ml/min, and median ACR of 18 [9–53] mg/g (25 persons had a normal ACR <30 mg/g, 14 had moderate albuminuria of 30–300 mg/g and 3 had severe albuminuria >300mg/g of ACR at biopsy).

Allograft Kidney Transplant Surveillance cohort

The University of Michigan has a kidney transplant surveillance program in which biopsies are performed for clinical care at implantation and 3-, 6- and 12-months post transplantation. A subset of patients in this surveillance program participate in the Human Kidney Transplant Transcriptomic Atlas study, which procures an additional biopsy core for research and tissues from these biopsies were used in the present study. Reference healthy tissue from 7 LD biopsies were obtained prior to perfusion and before placement in the recipient. To evaluate the kidney epithelial response to viral infection 3 biopsies from 2 patients with active BK viremia at the time of their surveillance biopsies were also included in the study. BKVN biopsies were obtained before, at the time of, or after peak BK viremia by which time immunosuppression was reduced.

LD biopsies were selected as healthy reference tissue. Participant age was 49.3 ± 12, range (31–66), five of the 7 donors were female (71.4%), mean spot urine protein to creatinine ratio at the time of evaluation was 0.07 ± 0.03 g/g with range (0.04–0.12), mean iothalamate GFR was 87 ± 5 ml/min/1.73 m2 with range (81–96). All donors were white, nondiabetic and non-hypertensive.

BK Virus Nephropathy (BKVN) biopsies from the transplant atlas cohort study were used, with the first BKVN patient being the recipient of a deceased donor kidney transplant, with a peak viral load >10,000 copies/ml and immunohistochemistry staining positive for SV40 (peak biopsy). After net reduction in immunosuppression the BK viral load dropped to <5000 copies/ml and a subsequent biopsy became negative for SV40 staining (post peak biopsy). The second patient was the recipient of a living donor kidney transplant and had a viral load of >10,000 copies/ml that had still not reached its peak at time of biopsy, but with positive SV40 biopsy staining (pre peak biopsy). Both patients were in the 3rd and 4th decade of life respectively. Clinical characteristics of the transplant atlas cohort participants are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

COVID-19 AKI Cohort Study (COV-AKI)

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic at the University of Michigan Medical Center a protocol to capture urine samples from SARS-CoV-2 patients was established to allow cell and molecular biology studies of the kidney manifestations in COVID-19. Patients are offered participation in the study upon admission to the hospital and throughout their hospital course. 50ml of a spot random urine sample is procured specifically for the study, immediately transported to the research laboratory on ice and processed for cell and molecular studies and participants are prospectively followed thereafter.

COVID-19 associated AKI (COV-AKI) was studied in urine derived PTEC from a male patient in the 5th decade of his life who had received a combined pancreas and kidney transplant two decades ago. The patient was diagnosed with COVID-19 eleven days before sample collection. Serum creatinine at time of collection was 2.3 mg/dl compared to baseline of 1.6 mg/dl. Urinalysis was significant for proteinuria, but with no RBCs on microscopy. No urinary sediment analysis was available at time of sample procurement. At the time of COVID-19 diagnosis the patient’s immunosuppression was reduced to dual immunosuppression with tacrolimus and prednisone with mycophenolate mofetil withhold. His kidney function returned to baseline 17 days after admission, 6 days after sample collection (Supplementary Figure 1).

Kidney biopsy sample processing for single cell

Single cell transcriptomes were generated with 2–3 mg of the biopsy core samples from 44 CryoStor® (Stemcell Technologies) preserved DKD, 7 LD and 3 BKVN samples. Tissue processing and single cell isolation were performed following our published protocol26. Briefly, the tissue samples were thawed at room temperature and dissociated to single cells using Liberase™ TL (research grade, Roche) at 37°C. Single cell samples were immediately transferred to the University of Michigan Advanced Genomics Core facility for further processing.

Urine cell preparation for scRNAseq in patients with COVID-19

Urine single cell preparation followed the protocol by Arazi et al. with various modifications27. Briefly, COV-AKI urine was filtered through a 30 μm strainer into 50 ml tubes and centrifuged at 200 × g at 4°C for 10 minutes. After removing and storing the supernatant the cell pellet was washed once with 1 ml cold X-VIVO™10 medium (Cat#: 04–743Q, Lonza) and centrifuged in 1.5 ml tubes for 5 minutes at 200 × g at 4°C. The resulting cell pellet was then suspended in 50 μl DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with HEPES and 10% (v/v) FBS and 50,000 cells were immediately loaded onto the 10X Genomics Chromium single cell droplet-based RNAseq platform. Next generation sequencing was carried out on a NovaSeq6000 (Illumina) machine to generate about 200 million reads per sample. All procedures were performed following biosafety precautions as directed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the University of Michigan guidelines.

scRNAseq data generation and analysis

Individual cell barcoding, reverse RNA transcription, library generation and single cell sequencing using Illumina were all performed using the 10X Genomics protocol26. The output from the sequencer was first processed by CellRanger, the proprietary 10X Chromium single cell gene expression analysis software (https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-geneexpression/software/pipelines/latest/what-is-cell-ranger). Data analyses were performed on the CellRanger output data files using the Seurat 3 R package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Seurat/index.html). As a quality control step, cells with less than 500 or greater than 5000 genes per cell were filtered out, with the lower cut off as a threshold for cell viability and the higher cut off to remove cell duplets. This study used a cutoff of < 50% mitochondrial reads per cell as an additional threshold for cell viability. A combined analysis of the single cell datasets generated from the different sample sources (LD and DKD) was followed by downstream analysis steps including normalization, scaling based on sample mRNA count and mitochondrial RNA content, dimensionality reduction PCA (Principal component analysis) and UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection), sample integration using Harmony algorithm28, standard unsupervised clustering, and the discovery of differentially expressed cell type specific markers29. For cell type annotation we used publicly available resources including published literature, Kidney Interactive Transcriptome (http://humphreyslab.com/SingleCell/), Human Protein Atlas (HPA) (https://www.proteinatlas.org), the Epithelial Systems Biology Laboratory (ESBL) (https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/), scRNAseq data and Immgen (https://www.immgen.org/). The same analysis processes were used for the BKVN and COV-AKI samples except that no Harmony-based integration step was performed. Further functional analyses were focused on PTEC with ACE2 (ACE2+) and without ACE2 (ACE2−) mRNA expression in the different samples studied.

Identification of differentially expressed ACE2+ co-regulated gene signatures

Differentially expressed genes were identified between ACE2+ and ACE2− PTEC in DKD, BKVN, and COV-AKI samples using the FindAllMarkers Seurat function. For DKD and BKVN signatures, all genes with adjusted p-value < 0.05 and found in at least 10% of cells were selected. Due to the comparatively small number of cells in COV-AKI sample, ACE2+ co-regulated genes that passed a nominal uncorrected p-value threshold of 0.05 and were found in at least 10% of cells were selected (Supplementary Tables 2–5).

Overlap of differentially expressed ACE2+ co-regulated gene signatures with SARS-CoV-2 relevant gene sets:

SARS-CoV-2 relevant gene sets were compiled from multiple published sources: 1) Bojkova_proteome is a list of differentially expressed proteins in Caco-2 cell line following SARS-Cov-2 infection (p < 0.05 at any time point)30; 2) Bojkova_translatome is a list of proteins with differential translatome kinetics following SARS-CoV-2 infection (p < 0.05 at any time point)30; 3) Gordon_interactome is a set of host proteins identified as physically interacting with SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins in HEK-293T cells31 ; 4) Zhou_interactome is a literature-curated list of genes related to diverse coronaviruses17; 5) Blanco-Melo_A459 is a list of differentially expressed genes in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in human alveolar adenocarcinoma cells32 ; 6) Blanco-Melo_NHBE is a list of differentially regulated genes in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in normal human bronchial epithelial cells32. ACE2 was removed from ACE2+ co-expressed gene sets before computing overlaps. P-values were computed using the hypergeometric test with a count of 20,000 genes used as background.

Functional network analysis

To determine the biological processes and pathways in the ACE2+ differentially expressed gene sets, functional network clustering of the PTEC gene functional network from GIANT 2.033, 34. This network was generated through regularized Bayesian integration of 61,400 publicly available expression, physical interaction and other omics experiments to generate a fully connected weighted graph representing functional relationships in biological pathways in PTEC. Community clustering in the network was performed to identify tightly connected sets of genes using HumanBase.io module detection function35 (flatironinstitute.org/module). The network was clustered with each set of ACE2+ differentially expressed genes: DKD differentially expressed genes, BKVN differentially expressed genes, the overlap of these two gene sets (DKD_BK_overlap, Supplementary Table 6), and ACE2+ differentially expressed genes in PTEC from the COV-AKI sample (Supplementary Table 5). For DKD and BKVN signatures, all genes with adjusted p-value < 0.05 and found in at least 10% of cells were selected. Due to the comparatively small number of cells in COV-AKI sample, ACE2+ co-regulated genes that passed a nominal uncorrected p-value threshold of 0.05 and were found in at least 10% of cells were selected. The Gene Ontology enrichment outputs are Supplementary Tables 7–10 and can be interactively explored at hb.flatironinstitute.org/covid-kidney.

Statistical analysis of clinical associations

Spearman correlation were used to evaluate the association of the steady state average PTEC specific gene expression levels of ACE2 and age at time of biopsy for the 44 DKD samples. The Mann-Whitney non parametric test was applied to evaluate the gender and treatment difference of ACE2 expression in the DKD cohort.

Study approval

All studies of the DKD population were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive under protocol 13-DK-N151. Transplant biopsies were obtained after review and approval of the Transplant Transcriptomic Atlas study under HUM00150968; DKD kidney biopsies gene expression analysis was performed under HUM00002468; Covid19 urine samples were obtained after review and approval under HUM00004729, all reviewed by the University of Michigan IRBMED.

Data Access

LD, BKVN and COV-AKI single cell data sets are searchable at NephroCell.miktmc.org. Owing to ethical considerations and privacy protection concerns, and to avoid identifying individual study participants in vulnerable populations, the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases has stipulated that individual-level gene expression and genotype data from the American Indian DKD study cannot be made publicly available.

A dynamic user-friendly interface at HumanBase (hb.flatironinstitute.org/covid-kidney) is available for researchers to explore the functional networks of gene expression signatures.

Results

We studied ACE2 expression and viral infection associated processes through scRNASeq and functional network analysis (Figure 1).

Cohort studied for SARS-CoV-2 receptor expression and regulation:

Kidney cell expression profiles were obtained from early DKD (n=44), LD (n=7), and BKVN (n=3) kidney biopsies and a urine sample from a COV-AKI patient. Baseline clinical characteristics for the DKD cohort are provided in Table 1, for BKVN in Supplementary Table 1, for COV-AKI in Supplementary Figure 1, with further details in methods.

scRNAseq based definition of SARS-CoV-2 receptor expression in kidney tissue

First, we defined the expression pattern of ACE2 among the cell populations obtained by the scRNAseq analysis in the 44 DKD and 7 LD biopsies. In a combined analysis of the two data sets with a resolution (clustering granularity) of 0.6, 17 cell clusters were defined (Figures 2A and 2B UMAP plots) with 15 clusters populated by cells from both sample sources, indicating presence of cells with comparable identity in both sample sources (Supplementary Figure 3). The 15 cell clusters covered the entire spectrum of kidney cell types found along the nephron and tissue resident immune cells.

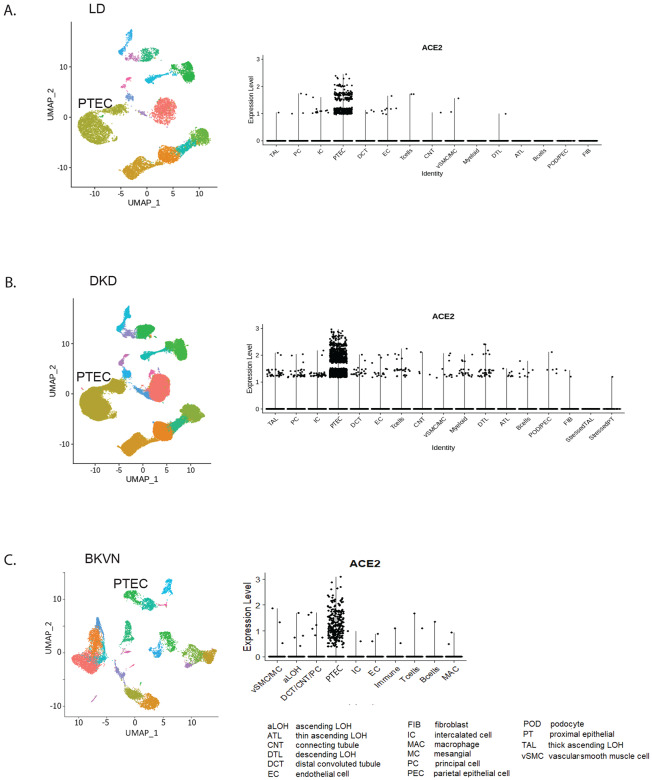

Figure 2. Unsupervised clustering of cells from living donor, DKD and BK re-activated kidney biopsies.

UMAP plots showing the distributions in unsupervised clustering of (A) 13,055 living donor kidney cells into 15 clusters; (B) was 85,872 cells by from DKD is into 17 clusters; (C) cells from BKVN into the 10 preprint clusters. The violin plots for each data set showing the specific expression of ACE2 in proximal tubular epithelial cells (PTEC) are shown to the right of the corresponding UMAP plots.

Next, to understand pathways activated in viral infection DKD biopsy PTEC DKD were compared to the corresponding cells in BKVN with BKVN scRNAseq signatures obtained before, at and after peak of BK viremia. The combined analysis of the three BKVN samples resulted in 10 clusters from 15135 cells. Unlike LD, we observed prominent immune cell clusters in the BKVN data set (Figure 2C UMAP plot) with cells assigned to PTEC clusters contributing only ~10% to the total cell population.

The violin plots in Figure 2 show a highly restricted, cell-type specific mRNA expression of ACE2 in the PTEC cell cluster consistently across LD, DKD and BKVN samples (Figure 2). Expression level differences of ACE2, TMPRSS2 and CTSL before, at and after peak are shown in supplementary Figure 2.

Defining ACE2+ expression signatures shared with SARS-CoV-2 host factors

To define the functional context of ACE2 expression signatures in kidney disease, we first identified gene expression programs specifically co-activated with the SARS-CoV-2 receptor expression. To this end the expression profiles of ACE2+ PTEC were compared to the ACE2-PTEC cell population in both DKD and BKVN. The resulting gene expression signatures (with p-value adjusted Bonferroni cutoff of 0.05 and expressed in at least 10% of cells) identified sets of genes whose expression is specifically induced in ACE2+ cells in LD (Supplementary Table 2), DKD (Supplementary Table 3) and BKVN (Supplementary Table 4). Critically, we then focused on identifying shared gene expression programs in ACE2+ PTEC in both DKD and BKVN samples (Supplementary Table 6).

We also analyzed the overlap of the ACE2+ signatures with SARS-CoV-2-implicated genes and ACE2 signature genes from multiple publicly available, independent studies and found significant shared components across SARS-CoV-2 datasets (Table 2). Specifically, genes associated with ACE2+ expression in DKD were also significantly enriched among host proteins identified to interact with SARS-CoV-2 proteins33, host genes upregulated in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells30, 32, and host proteins previously reported to interact with multiple coronaviruses17. Such cellular proteins could represent cellular targets of viral infection (permissive factors), cellular responses to viral infection (restriction factors), or a mix. A robust overlap between the ACE2+ DKD and BKVN expression signatures and both SARS-CoV-2-related interactome and differentially expressed gene sets were observed, supporting the activation of a related gene program in SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Functionally characterizing shared proximal tubule ACE2 co-regulated gene programs

To functionally characterize these ACE2+ expression signatures, we projected these genes onto networks that represent pathways active in normal PTEC. Intuitively, the HumanBase functional network is constructed by probabilistically integrating a large compendium of thousands of public omics datasets (including expression, protein-protein interaction and motifs) to represent how likely it is that two genes act together in biological processes that function in PTEC33, 34. We clustered genes differentially expressed in ACE2+ vs ACE2− PTEC of the DKD kidneys in this functional network (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table 7). The resulting modules contain key processes of tubular function and failure, including renal tubule development and ion transport, general cellular processes such as cell cycle control and translational regulation, as well as disease signals including inflammatory pathway activation (IL-2 production, JAK/STAT signaling, and Wnt signaling). Importantly, we also identify key processes important to both immune response and viral entry and life cycle, including viral entry, viral gene transcription and translation, endomembrane organization, endosomal transport, and RNA metabolism (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table 7). Immune processes were significantly enriched across multiple modules and encompassed processes including innate immune responses (secretion and response to interferons alpha, beta, and gamma), cytokine production, macrophage activation. The robust activation of immune-related functions links ACE2+ (vs ACE2−) PTEC to these key elements of DKD pathophysiology. Focusing on the program involved in response to viral infection, we find that indeed, many of these modules are also shared with ACE2+ (vs ACE2−) PTEC in BKVN (Supplementary Figure 4, Supplementary Table 8). The congruence between the DKD and BKVN signals at both gene and functional process levels supports the robustness of this ACE2+ molecular signature and suggests that at least some of the programs related to establishment of productive viral infection and to innate immune responses seen in BKVN are also present in the DKD ACE2+ PTEC even without an active viral infection (Figure 3B, Supplementary Table 9). We hypothesize that some of these expression programs could be permissive to viral infection, along with the upregulation of ACE2 receptor.

Figure 3. Functional summary of ACE2+ expression signature.

ACE2+ co-expression signatures were used for community clustering in a PTEC-specific functional network to identify enriched processes and pathways specific to (a) ACE2+ co-expression signatures from DKD biopsy samples and (b) ACE2+ co-expressed genes shared between DKD and BK virus reactivation transplant biopsy samples.

Association of ACE2 mRNA expression in PTEC with clinical features

We then assessed differential ACE2 expression in PTEC in DKD compared to LD and found a significant overexpression of ACE2 steady state mRNA levels in DKD (adjusted p-value < 11.79 e-23; in cells with normalized read count >= 1.25) (Figure 3A). We focused on cells with ACE2 expression above 1.25 to exclude the ambient ACE2 mRNA expression (~ 1 normalized read count) observed in most cell types as seen in Figure 2. Importantly, proteases thought to be permissive for coronavirus infection including ANPEP, BSG, CTSL, DPP4, ENPEP, FURIN and TMPRSS2 appear to co-express with ACE2 in PTEC (Figure 4A, B). The expression levels of ACE2 transcripts in PTEC did not show a significant association with baseline DKD participant characteristics (age/gender, Figure 4C and D) or treatment exposures to renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors (Figure 4E–G).

Figure 4. (A and B) ACE2 and related proteases expression in proximal cells.

Dot plot showing the expression of proteases in DKD (in red) and LD (in blue) PTEC. Grey color denotes moderate expression (which in the was cell the by size the is dot of cells expressing gene. in Proteases were grouped into two based on the overall expression pattern in proximal cells (expression in < or >= 30% of the cells) Panel A depicts moderate (<30% of cells) and panel B widely (>=30% of cells) expressed proteases with maximal expression of ACE2 and ANPEP in DKD compared to living donor in contrast to FURIN, TMPRSS2, BSG, CTSL, DPP4 and ENPEP with higher expression in LD.

(C-G) Clinical Associations of ACE expression in proximal tubular epithelial cells in DKD.

Proximal Tubular expression of ACE2 in Female vs. Male (C) correlation with Age (D), and in relationship to exposure to any Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone-System Blockers (E); Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (F); Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors(G).

Transcriptional profile in urine derived proximal tubular epithelial cells in COVID-19

Finally, the PTEC cellular response in COVID-19 was assessed using urinary scRNAseq analysis constrained to PTEC gene expression clusters. Single cell data analysis of the cells isolated from the urine of a SARS-CoV-2 infected patient yielded 273 cells that passed our quality control threshold. Unsupervised clustering of these cells produced three kidney cell clusters, including PTEC, and two immune cell clusters (Figure 5A and B). 42% of the cells in the PTEC cluster showed ACE2 expression. In addition to ACE2, proteases including ANPEP, BSG, CTSL, DPP4, ENPEP, FURIN and TMPRSS2 were expressed in PTEC from the COV-AKI sample (Figure 5C, Supplementary Table 5). BSG and ANPEP were found to be expressed in all proximal cells identified (Figure 5C). Supplementary Table 11 provides the PTEC markers identified in COV-AKI. Notably, genes nominally upregulated in ACE2+ vs ACE2− COV-AKI urine derived PTEC (Supplementary Table 10) significantly overlap the ACE2+ DKD and BKVN kidney biopsy disease signature (p-value =7.7×10–7). Examining the ACE2+ co-expressed functional network in the COV-AKI PTEC cell population identified a signature enriched for viral processes (Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 5. Single cell analysis of cells isolated from the urine of patient with covid19 related acute kidney injury.

(A) Umap plot showing the 5 clusters identified from 273 cells. (B) Heatmap showing enriched markers identified in the 5 clusters identify cell types. (C) Expression of SARS-CoV-2 associated proteases, ACE2, ANPEP, BSG, CTSL, ENPEP, FURIN No and the 5 identified cell types.

Discussion

With the pandemic spread of COVID-19 and the increased COVID-19 morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes and kidney disease it is imperative to define the underlying mechanism of the excessive risk in patients with diabetes and rapidly develop protective strategies for risk reduction. Autopsy studies of patients with COVID-19 are consistent with direct viral infection of the kidney and that even within the kidney12, 36, expression of molecules that mediate viral entry may be cell type-specific12. Susceptibility to viral entry may be enhanced by DKD associated changes in SARS-CoV-2 receptor expression in kidney tissue.

Our study set out to establish the cell population within the kidney expressing ACE2 and associated SARS-CoV-2 receptors mRNA in healthy individuals and in patients with DKD and viral associated kidney diseases. ACE2 intra-renal gene expression was localized narrowly to PTEC in surveillance kidney biopsies obtained from LD and in research kidney biopsies from patients with DKD. PTEC are the prime localization of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the kidney36, supporting the link between receptor expression and cellular toxicity in kidneys, as well. In contrast to findings in other cell types, little co-expression of ACE2 with TMPRSS2 co-receptor used for SARS-CoV-2 viral entry was observed, suggesting other cell surface proteases may be associated with viral infection and uptake in the kidney12, 36.

Despite the fact that none of the diabetic patients in this study were infected with SARS-CoV-2 at the time of biopsy, our pathway analysis showed that processes including infection, protein processing and antigen presentation were enriched in high versus low ACE2 expressing PTEC in DKD. The results from this analysis suggest that ACE2 is co-expressed with a set of genes also having functions in viral entry, establishment of viral replication, and innate immunity.

A key finding of our study is that ACE2+ proximal tubule cells of patients with DKD had significantly higher ACE2 mRNA levels than those of LDs. These higher ACE2 levels may make these cells more permissive to initial viral entry and subsequent increased cellular cytotoxicity in DKD, especially as viral replication and processing machinery also appear to be upregulated in the ACE2+ PTEC. This includes genes involved in endomembrane transport and lysosomal compartments, which we hypothesize could facilitate viral entry and exit, and proteins that interact with viral transcription and translation. It is intriguing that a number of the ACE2+ signature genes interact with predicted or demonstrated SARS-CoV-2 anti-host defense response proteins31, including M (suppresses type1 interferon response and refine cytokine responses)37, 38, N (inhibit autophagy and apoptosis of infected cells)39, Orf3a (modulates IL-1B)40, and Nsp6 (inhibits phagosome expansion and targeting of viral products to lysosome)41. These interactions may simply reflect an element of the functional host response program to cellular stress in DKD. However, if these interactions also involve negative functional regulation of host-defense proteins, ACE2+ proximal tubule cells could be impaired in their ability to mount an appropriate host response, providing one explanation of their observed vulnerability to infection to SARS-CoV-2.

The inflammatory signals observed in the DKD and BKVN PTEC are expected in the context of chronic kidney disease as reported previously by studies in this and other DKD patient populations42, 43. However, these data also could support the hypothesis that this inflammatory state could be maladaptive for a response to viral infection. Recent work on lung epithelial cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 has shown a blunted interferon response despite robust cytokine production still being present32; a potential hallmark of SARS-CoV-2 pathology. If a comparably asymmetric inflammatory response is already present in DKD kidney tissue, viral infection could amplify the pre-existing inappropriate stress response, increasing cytopathology and enabling further viral propagation. If ACE2 upregulation is indeed correlated with a cellular inflammatory state that permits enhanced viral pathogenesis and replication in multiple organ systems, this linkage could provide an evolutionary driving factor to select ACE2 for viral entry.

The PTEC specific ACE2+ networks observed in DKD, BKVN and COV-AKI allow for a wide range of exploratory studies to generate starting points for functional evaluation. Given the urgent need for novel therapeutic options, intersecting the ACE2 regulatory networks with the complex landscape of interactions between drugs and the gene signature defined here can help to identify therapeutic targets for further study. We identified ACE2+ co-regulated genes annotated in DrugBank44 as targets of medications regularly taken by patients with DKD. For example, insulin (INSR, in M5 in Figure 3B) and the IGF-1 receptor (IGF1R, in M3 in Figure 3B) are overexpressed in ACE2+ PTEC as is DPP4 (in M5 in Figure 3B), a protease associated with entry of other coronaviruses and a key factor in glucose metabolism, targeted by DPP4 inhibitors already in clinical use. These interactions suggest that the ACE2+ co-expression signature may be influenced by a number of commonly used drugs and can form the starting points for further mechanistic and epidemiological studies.

As data emerged on the role of ACE2 as a receptor for SARS-CoV-2, significant concerns were raised about risks of RAAS inhibitors frequently prescribed in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney diseases. Based on animal models RAAS inhibitors were predicted to increase ACE2 levels raising the potential concern for higher COVID-19 morbidity and mortality22, 45, 46. However, our findings in the DKD cohort do not support the animal model data and do not provide any evidence of transcriptional upregulation of ACE2 mRNAs in PTEC by RAAS inhibition. In parallel, a series of case control, database and Electronic Health Record studies did not find an association of RAAS inhibitors with poor outcomes in three independent cohorts of patients with COVID19 and RAAS exposures47–49, consistent with our scRNAseq studies.

ACE2 gene expression studies of kidney tissue to date have been inconclusive concerning regulation in kidney disease50–53. A strength of our study is the definition of the ACE2 expression to the cellular context of PTEC in distinct infectious and non-infectious kidney diseases. As PTEC mass is lost in kidney disease, the cellular resolution of the receptor expression achieved by scRNAseq is critical to detect the increased receptor load per cell versus the average receptor expression level across all cells obtained in analyses of bulk renal biopsies to date. The PTEC dominant ACE2 scRNAseq expression data presented here match the immunohistochemical tissue distribution pattern in the human protein atlas54 (https://www.proteinatlas.org/, Supplementary Figure 6), but given the limited sensitivity of scRNAseq, do not rule out low level expression in other renal cell types.

An important element of this study is the confirmation of ACE2 and associated genes and modules in PTEC derived from a COV-AKI sample. The association of ACE2 expression with proteins involved in innate immune response and viral entry and replication provides an intriguing hypothesis for how SARS-CoV-2 can cause increased cytopathology in ACE2+ cells. However, these findings have to be considered exploratory, as they are based on a small population of PTEC which have lost their structural kidney tissue context in a single patient with COV-AKI. Confirmation of these findings in a larger cohort of COVID-19 patients and ideally from kidney tissue is needed.

Our study is also limited by focusing on mRNA levels, which only capture one of several levels of regulation of ACE2 function. For this reason, our analyses focused on the definition of co-regulation networks to capture the change in transcriptional programs as a functional read out and not protein activity directly. However, as noted above, our mRNA findings for ACE2 are consistent with protein expression specificity from the Human Protein Atlas.

Based on these considerations, further experimental validation of the predicted regulation and therapeutic interventions are critical next steps. Experimental model systems of kidney SARS-CoV-2 toxicity are currently under development, including human kidney organoid systems which do express ACE2 in the correct functional context55 (nephrocell.miktmc.org,).

In summary, our work identifies the regulation and associated cellular machinery of ACE2 and associated SARS-CoV-2 co-receptors in PTECs in kidney health, metabolic and viral disease. The SARS-CoV-2 receptor associated networks are now available to seed further research into urgently needed therapeutic strategies for COVID-19.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Serum creatinine (mg/dl) time course across COVID-19 related illness and hospitalization in a kidney pancreas transplant recipient.

Supplementary Figure 2: Violin plot showing the expression of ACE2, TMPRSS2 and CTSL in the three BKVN samples.

Supplementary Figure 3: UMAP plot showing the distribution of the cells in the 17 clusters resulting from the unsupervised clustering of the scRNA-seq data from DKD (red) and LD biopsies (blue).

Supplementary Figure 4: Functional summary of ACE2+ expression signature for BKVN.

Supplementary Figure 5: Functional summary of ACE2+ expression signature from COIVD-19 patient.

Supplementary Figure 6: ACE2 immunostaining in human kidney tissue.

Supplementary Table 1: Clinical characteristics of BKVN cohort.

Supplementary Table 2: Differential expression gene list between ACE2+ and ACE2− PTEC in LD.

Supplementary Table 3: Differential expression gene list between ACE2+ and ACE2− PTEC in DKD.

Supplementary Table 4: Differential expression gene list between ACE2+ and ACE2− PTEC in BKVN.

Supplementary Table 5: Differential expression gene list between ACE2+ and ACE2− PTEC in COV-AKI.

Supplementary Table 6: Overlap of differentially expressed genes in DKD and BKVN.

Supplementary Table 7: The Gene Ontology enrichments for network modules of ACE2+ differentially expressed genes in DKD.

Supplementary Table 8: The Gene Ontology enrichments for network modules of ACE2+ differentially expressed genes in BKVN.

Supplementary Table 9: The Gene Ontology enrichments outputs for the network modules of ACE2+ differentially expressed genes overlapping in DKD and BKVN.

Supplementary Table 10: The Gene Ontology enrichments for network modules of ACE2+ differentially expressed genes in COV-AKI.

Supplementary Table 11: PTEC-specific markers in the COV-AKI sample.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Ms. Lois Jones, RN, Mr. Enrique Diaz, RN, Ms. Bernadine Waseta, and Ms. Camille Waseta for performing the studies in the diabetes cohort and the University of Michigan Advanced Genomics Core for providing expert technical assistance with single cell processing and sequencing.

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK069062) to HCL and RGN and (DK083912, DK082841, DK020572, DK092926) to RGK, by the extramural research program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases R24 DK082841 ‘Integrated Systems Biology Approach to Diabetic Microvascular Complications’ and P30 DK081943 ‘University of Michigan O’Brien Kidney Translational Core Center’ to MK, via ‘Kidney Precision Medicine Project’ (KPMP, funded by the following grants from the NIDDK: U2C DK114886, UH3DK114861, UH3DK114866, UH3DK114870, UH3DK114908, UH3DK114915, UH3DK114926, UH3DK114907, UH3DK114920, UH3DK114923, UH3DK114933, and UH3DK114937, with U2C DK114886 and UH3 DK114907) to MK and OGT, via the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative ‘Human Cell Atlas Kidney Seed Network’ to MK and OGT and by JDRF 5-COE-2019-861-S-B ‘JDRF and M-Diabetes Center of Excellence at the University of Michigan’ to MK. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

For the Kidney Precision Medicine Project

American Association of Kidney Patients, Tampa, FL: Richard Knight

Beth Israel Deaconess, Boston, MA: Stewart Lecker, Isaac Stillman

Boston University, Boston, MA: Sushrut Waikar,

Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA: Gearoid Mcmahon, Astrid Weins, Samuel Short

Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA: Nir Hacohen, Paul Hoover

Case Western Reserve, Cleveland, OH: Mark Aulisio

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH: Leslie Cooperman, Leal Herlitz, John O’toole, Emilio Poggio, John Sedor, Stacey Jolly

Columbia University, New York, NY: Paul Appelbaum, Olivia Balderes, Jonathan Barasch, Andrew Bomback, Pietro A. Canetta, Vivette D. D’Agati, Krzysztof Kiryluk, Satoru Kudose, Karla Mehl, Jai Radhakrishnan, Chenhua Weng

Duke University, Durham, NC: Laura Barisoni

European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Heidelberg, Germany: Theodore Alexandrov

Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN: Tarek Ashkar, Daria Barwinska, Pierre Dagher, Kenneth Dunn, Michael Eadon, Michael Ferkowicz, Katherine Kelly, Timothy Sutton, Seth Winfree

John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Steven Menez, Chirag Parikh, Avi Rosenberg, Pam Villalobos, Rubab Malik, Derek Fine, Mohammed Atta, Jose Manuel Monroy Trujillo,

Joslin Diabetes Center, Boston, MA: Alison Slack, Sylvia Rosas, Mark Williams

Mount Sinai, New York, NY: Evren Azeloglu, Cijang (John) He, Ravi Iyengar, Jens Hansen

Ohio State University, Columbus, OH: Samir Parikh, Brad Rovin

Pacific Northwest National Laboratories, Richland, WA: Chris Anderton, Ljiljana Pasa-Tolic, Dusan Velickovic, Jessica Lukowski

Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation, Dallas, TX: George (Holt) Oliver

Patient Partners: Joseph Ardayfio, Jack Bebiak, Keith Brown, Taneisha Campbell, Catherine Campbell, Lynda Hayashi, Nichole Jefferson, Robert Koewler, Glenda Roberts, John Saul, Anna Shpigel, Edith Christine Stutzke, Lorenda Wright, Leslie Miegs, Roy Pinkeney

Princeton University, Princeton, NJ: Rachel Sealfon, Olga Troyanskaya

Providence Medical Research Center, Providence Health Care, Spokane, WA: Katherine Tuttle

Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA: Dejan Dobi, Yury Goltsev

University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA: Blue Lake, Kun Zhang

University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA: Maria Joanes, Zoltan Laszik, Andrew Schroeder, Minnie Sarwal, Tara Sigdel

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI: Ulysses Balis, Victoria Blanc, Oliver He, Jeffrey Hodgin, Matthias Kretzler, Laura Mariani, Rajasree Menon, Edgar Otto, Jennifer Schaub, Becky Steck, Chrysta Lienczewski, Sean Eddy

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Michele Elder, Daniel Hall, John Kellum, Mary Kruth, Raghav Murugan, Paul Palevsky, Parmjeet Randhawa, Matthew Rosengart, Sunny Sims-Lucas, Mary Stefanick, Stacy Stull, Mitchell Tublin

University of Washington, Seattle, WA: Charles Alpers, Ian de Boer, Ashveena Dighe, Jonathan Himmelfarb, Robyn Mcclelland, Sean Mooney, Stuart Shankland, Kayleen Williams, Kristina Blank, Jonas Carson, Frederick Dowd, Zach Drager, Christopher Park

UT Health San Antonio, Center for Renal Precision Medicine, San Antonio, TX: Kumar Sharma, Guanshi Zhang, Shweta Bansal, Manjeri Venkatachalam,

UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX: Asra Kermani, Simon Lee, Christopher Lu, Tyler Miller, Orson Moe, Harold Park, Kamalanathan Sambandam, Francisco Sanchez, Jose Torrealba, Toto Robert, Miguel Vazquez, Nancy Wang

Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO: Joe Gaut, Sanjay Jain, Anitha Vijayan

Yale University, New Haven, CT: Randy Luciano, Dennis Moledina, Ugwuowo Ugochukwu, Francis Perry Wilson, Sandy Alfano

References

- 1.Muniyappa R, Gubbi S. COVID-19 Pandemic, Corona Viruses, and Diabetes Mellitus. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shahid Z, Kalayanamitra R, McClafferty B, et al. COVID-19 And Older Adults: What We Know. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020; n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emami A, Javanmardi F, Pirbonyeh N, et al. Prevalence of Underlying Diseases in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Acad Emerg Med 2020; 8: e35–e35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.South AM, Diz DI, Chappell MC. COVID-19, ACE2, and the cardiovascular consequences. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2020; 318: H1084–H1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pal R, Bhansali A. COVID-19, diabetes mellitus and ACE2: The conundrum. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2020; 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye M, Wysocki J, William J, et al. Glomerular Localization and Expression of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 and Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme: Implications for Albuminuria in Diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17: 3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drucker DJ. Coronavirus infections and type 2 diabetes-shared pathways with therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muus C, Luecken MD, Eraslan G, et al. Integrated analyses of single-cell atlases reveal age, gender, and smoking status associations with cell type-specific expression of mediators of SARS-CoV-2 viral entry and highlights inflammatory programs in putative target cells. bioRxiv 2020: 2020.2004.2019.049254. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding Y, He L, Zhang Q, et al. Organ distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in SARS patients: implications for pathogenesis and virus transmission pathways. The Journal of Pathology 2004; 203: 622–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henry BM, Lippi G. Chronic kidney disease is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Int Urol Nephrol 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, et al. Kidney impairment is associated with in-hospital death of COVID-19 patients. medRxiv 2020: 2020.2002.2018.20023242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farkash EA, Wilson AM, Jentzen JM. Ultrastructural Evidence for Direct Renal Infection with SARS-CoV-2. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020: ASN.2020040432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gheblawi M, Wang K, Viveiros A, et al. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 Receptor and Regulator of the Renin-Angiotensin System. Circ Res 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia HP, Look DC, Shi L, et al. ACE2 receptor expression and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection depend on differentiation of human airway epithelia. J Virol 2005; 79: 14614–14621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuba K, Imai Y, Ohto-Nakanishi T, et al. Trilogy of ACE2: A peptidase in the renin-angiotensin system, a SARS receptor, and a partner for amino acid transporters. Pharmacol Ther 2010; 128: 119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo J, Huang Z, Lin L, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and Cardiovascular Disease: A Viewpoint on the Potential Influence of Angiotensin‐Converting Enzyme Inhibitors/Angiotensin Receptor Blockers on Onset and Severity of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection. 2020; 9: e016219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou L, Niu Z, Jiang X, et al. Systemic analysis of tissue cells potentially vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection by the protein-proofed single-cell RNA profiling of ACE2, TMPRSS2 and Furin proteases. bioRxiv 2020: 2020.2004.2006.028522. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar A, Faiq MA, Pareek V, et al. Relevance of enriched expression of SARS-CoV-2 binding receptor ACE2 in gastrointestinal tissue with pathogenesis of digestive symptoms, diabetes-associated mortality, and disease recurrence in COVID-19 patients. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Diao B, Wang C, Wang R, et al. Human Kidney is a Target for Novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection. 2020: 2020.2003.2004.20031120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020; 181: 271–280.e278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glowacka I, Bertram S, Müller MA, et al. Evidence that TMPRSS2 Activates the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Protein for Membrane Fusion and Reduces Viral Control by the Humoral Immune Response. J Virol 2011; 85: 4122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perico L, Benigni A, Remuzzi G. Should COVID-19 Concern Nephrologists? Why and to What Extent? The Emerging Impasse of Angiotensin Blockade. Nephron 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al Heialy S, Hachim MY, Senok A, et al. Regulation of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in obesity: implications for COVID-19. bioRxiv 2020: 2020.2004.2017.046938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Looker HC, Mauer M, Saulnier P-J, et al. Changes in Albuminuria But Not GFR are Associated with Early Changes in Kidney Structure in Type 2 Diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019; 30: 1049–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delanaye P, Radermecker RP, Rorive M, et al. Indexing glomerular filtration rate for body surface area in obese patients is misleading: concept and example. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2005; 20: 2024–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menon R, Otto EA, Hoover P, et al. Single cell transcriptomics identifies focal segmental glomerulosclerosis remission endothelial biomarker. JCI Insight 2020; 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arazi A, Rao DA, Berthier CC, et al. The immune cell landscape in kidneys of patients with lupus nephritis. Nat Immunol 2019; 20: 902–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korsunsky I, Millard N, Fan J, et al. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nature Methods 2019; 16: 1289–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stuart T, Butler A, Hoffman P, et al. Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell 2019; 177: 1888–1902.e1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bojkova D, Westhaus S, Costa R, et al. Sofosbuvir Activates EGFR-Dependent Pathways in Hepatoma Cells with Implications for Liver-Related Pathological Processes. Cells 2020; 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon DE, Jang GM, Bouhaddou M, et al. A SARS-CoV-2-Human Protein-Protein Interaction Map Reveals Drug Targets and Potential Drug-Repurposing. bioRxiv 2020: 2020.2003.2022.002386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanco-Melo D, Nilsson-Payant BE, Liu W-C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 launches a unique transcriptional signature from in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo systems. bioRxiv 2020: 2020.2003.2024.004655. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong AK, Krishnan A, Troyanskaya OG. GIANT 2.0: genome-scale integrated analysis of gene networks in tissues. Nucleic Acids Res 2018; 46: W65–W70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greene CS, Krishnan A, Wong AK, et al. Understanding multicellular function and disease with human tissue-specific networks. Nat Genet 2015; 47: 569–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krishnan A, Zhang R, Yao V, et al. Genome-wide prediction and functional characterization of the genetic basis of autism spectrum disorder. Nat Neurosci 2016; 19: 1454–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su H, Yang M, Wan C, et al. Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ng DK, Robertson CC, Woroniecki RP, et al. APOL1-associated glomerular disease among African-American children: a collaboration of the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) and Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network (NEPTUNE) cohorts. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017; 32: 983–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siu KL, Kok KH, Ng MH, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus M protein inhibits type I interferon production by impeding the formation of TRAF3.TANK.TBK1/IKKepsilon complex. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 16202–16209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le Sage V, Cinti A, Amorim R, et al. Adapting the Stress Response: Viral Subversion of the mTOR Signaling Pathway. Viruses 2016; 8: 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siu K-L, Yuen K-S, Castaño-Rodriguez C, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus ORF3a protein activates the NLRP3 inflammasome by promoting TRAF3-dependent ubiquitination of ASC. The FASEB Journal 2019; 33: 8865–8877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cottam EM, Whelband MC, Wileman T. Coronavirus NSP6 restricts autophagosome expansion. Autophagy 2014; 10: 1426–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nair V, Komorowsky CV, Weil EJ, et al. A molecular morphometric approach to diabetic kidney disease can link structure to function and outcome. Kidney Int 2018; 93: 439–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmid H, Boucherot A, Yasuda Y, et al. Modular activation of nuclear factor-kappaB transcriptional programs in human diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 2006; 55: 2993–3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wishart DS, Knox C, Guo AC, et al. DrugBank: a comprehensive resource for in silico drug discovery and exploration. Nucleic Acids Res 2006; 34: D668–D672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghosal S, Mukherjee JJ, Sinha B, et al. The effect of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers on death and severity of disease in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A meta-analysis. medRxiv 2020: 2020.2004.2023.20076661. [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Simone G, Mancusi C. Speculation is not evidence: antihypertensive therapy and COVID-19. European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mehra MR, Desai SS, Kuy S, et al. Cardiovascular Disease, Drug Therapy, and Mortality in Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 48.Mancia G, Rea F, Ludergnani M, et al. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Blockers and the Risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reynolds HR, Adhikari S, Pulgarin C, et al. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitors and Risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mizuiri S, Ohashi Y. ACE and ACE2 in kidney disease. World J Nephrol 2015; 4: 74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rao S, Lau A, So H-C. Exploring diseases/traits and blood proteins causally related to expression of ACE2, the putative receptor of 2019-nCov: A Mendelian Randomization analysis. medRxiv 2020: 2020.2003.2004.20031237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reich HN, Oudit GY, Penninger JM, et al. Decreased glomerular and tubular expression of ACE2 in patients with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease. Kidney Int 2008; 74: 1610–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ye M, Wysocki J, Naaz P, et al. Increased ACE 2 and Decreased ACE Protein in Renal Tubules From Diabetic Mice. 2004; 43: 1120–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015; 347: 1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harder JL, Menon R, Otto EA, et al. Organoid single cell profiling identifies a transcriptional signature of glomerular disease. JCI Insight 2019; 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Serum creatinine (mg/dl) time course across COVID-19 related illness and hospitalization in a kidney pancreas transplant recipient.

Supplementary Figure 2: Violin plot showing the expression of ACE2, TMPRSS2 and CTSL in the three BKVN samples.

Supplementary Figure 3: UMAP plot showing the distribution of the cells in the 17 clusters resulting from the unsupervised clustering of the scRNA-seq data from DKD (red) and LD biopsies (blue).

Supplementary Figure 4: Functional summary of ACE2+ expression signature for BKVN.

Supplementary Figure 5: Functional summary of ACE2+ expression signature from COIVD-19 patient.

Supplementary Figure 6: ACE2 immunostaining in human kidney tissue.

Supplementary Table 1: Clinical characteristics of BKVN cohort.

Supplementary Table 2: Differential expression gene list between ACE2+ and ACE2− PTEC in LD.

Supplementary Table 3: Differential expression gene list between ACE2+ and ACE2− PTEC in DKD.

Supplementary Table 4: Differential expression gene list between ACE2+ and ACE2− PTEC in BKVN.

Supplementary Table 5: Differential expression gene list between ACE2+ and ACE2− PTEC in COV-AKI.

Supplementary Table 6: Overlap of differentially expressed genes in DKD and BKVN.

Supplementary Table 7: The Gene Ontology enrichments for network modules of ACE2+ differentially expressed genes in DKD.

Supplementary Table 8: The Gene Ontology enrichments for network modules of ACE2+ differentially expressed genes in BKVN.

Supplementary Table 9: The Gene Ontology enrichments outputs for the network modules of ACE2+ differentially expressed genes overlapping in DKD and BKVN.

Supplementary Table 10: The Gene Ontology enrichments for network modules of ACE2+ differentially expressed genes in COV-AKI.

Supplementary Table 11: PTEC-specific markers in the COV-AKI sample.