Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The major clinical obstacle that limits the long-term benefits of treatment with osimertinib (AZD9291 or TAGRISSO™) in patients with EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the development of acquired resistance. Therefore, effective strategies that can overcome osimertinib acquired resistance are urgently needed. Our efforts in this direction have identified LBH589 (panobinostat), a clinically used HDAC inhibitor, as a potential agent in overcoming osimertinib resistance.

METHODS:

Cell growth and apoptosis in vitro were evaluated by measuring cell numbers and colony formation and by detecting annexin V-positive cells and protein cleavage, respectively. Drug effects on tumor growth in vivo were assessed with xenografts in nude mice. Alterations of tested proteins in cells were monitored with Western blotting. Gene knockout was achieved using CRISPR/Cas9 technique.

RESULTS:

The combination of LBH589 and osimertinib synergistically decreased the survival of different osimertinib-resistant cell lines including those harboring C797S mutation with greater inhibition of cell colony formation and growth. The combination enhanced the induction of apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant cells. Importantly, the combination effectively inhibited the growth of osimertinib-resistant xenograft tumors in nude mice. Mechanistically, the combination of LBH589 and osimertinib enhanced the elevation of Bim in osimertinib-resistant cells. Knockout of Bim in osimertinib-resistant cells substantially attenuated or abolished apoptosis enhanced by the LBH589 and osimertinib combination. These results collectively support a critical role of Bim elevation in the induction of apoptosis of osimertinib-resistant cells by this combination.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our findings thus provide strong preclinical evidence in support of the potential for LBH589 to overcome osimertinib resistance in the clinic.

Keywords: LBH589, HDAC, osimertinib, acquired resistance, EGFR, apoptosis, lung cancer

Precis:

The major clinical obstacle that limits the long-term benefits of treatment with osimertinib in patients with EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer is the development of acquired resistance. This study provides strong preclinical evidence in support of the potential for HDAC inhibition to overcome osimertinib resistance in the clinic.

INTRODUCTION

Targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase with small molecule EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) represents a major advance in the targeted therapy of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) carrying activating EGFR mutations. Hence, the development of EGFR-TKIs progressed rapidly from the initial 1st generation (e.g., gefitinib and erlotinib) to 2nd generation (e.g., afatinib) and now 3rd generation (e.g., osimertinib; also named AZD9291 or TAGRISSO™) agents1. However, the major challenge in the clinic is the emergence of acquired resistance in patients to these EGFR-TKIs, limiting the long-term benefit to patients1.

Approximately 60% of cases with resistance to 1st generation EGFR-TKI treatment are caused by acquisition of the T790M resistance mutation2–4. To overcome T790M-induced resistance, osimertinib and other 3rd generation EGFR-TKIs were developed, which selectively and irreversibly inhibit EGFR harboring the common “sensitive” mutations, 19del and L858R, and the resistant T790M mutation while sparing wild-type EGFR. Among them, osimertinib is now an FDA-approved drug for NSCLC patients with activating EGFR mutations (first-line) or those who have become resistant to 1st generation EGFR-TKIs through the T790M mutation (second-line). Nonetheless, all patients unavoidably develop resistance to osimertinib, resulting in eventual treatment failure in the clinic5, 6. Therefore, overcoming resistance to osimertinib and other 3rd generation EGFR-TKIs is a highly desirable goal in the clinic.

Histone deacetylases (HDACs), consisting of 18 potential HDACs grouped into four classes in human, reverse chromatin acetylation and alter transcription of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes by removing acetyl groups from the ɛ-amino lysine residues on histone tails. HDACs are frequently overexpressed in several types of malignancies and tightly associated with cancer development, thus representing another attractive target for cancer therapy7. Multiple HDAC inhibitors have been developed that exhibit powerful antitumor abilities. Some of these agents, including the pan-HDAC inhibitors, vorinostat (SAHA) and panobinostat (LBH589), are now FDA-approved anticancer drugs8. Several previous studies have demonstrated that the combination of an EGFR-TKI (e.g., gefitinib or erlotinib) with an HDAC inhibitor (e.g., MS-275, SAHA, LBH589, MPT0E028 or YF454A) enhanced effects including the induction of apoptosis and inhibition of growth of glioblastoma, pancreatic cancer, head and neck cancer and lung cancer cells9–20. However, whether the combination of osimertinib with an HDAC inhibitor exerts enhanced effects against EGFR-mutant NSCLC cell lines with acquired resistance to osimertinib has not been well studied and thus is the focus of this study. We found that osimertinib in combination with LBH589 synergistically decreased the survival and enhanced induction of apoptosis of several osimertinib-resistant NSCLC cell lines. This enhanced growth-inhibitory effect was validated in vivo using mouse xenograft models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

LBH589 was provided by Novartis (Basel, Switzerland). Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA; also called vorinostat or zolinza) was purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX). EGFR antibody (sc-71034) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). p-EGFR (Y1065) and p-EGFR (Y1173) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc (#2234; Beverly, MA) and AbboMax (#600–290; San Jose, CA), respectively. The sources for other agents and antibodies were the same as described previously21.

Cell lines and cell culture

The osimertinib-resistant cell lines PC-9/AR, PC-9/GR/AR, PC-9/3M and HCC827/AR (see Table 1) and culture conditions were the same as described previously21. PC-9/GR/AR/Bim-KO cell lines were generated by infecting PC-9/GR/AR cells with lentiviruses carrying CRISPR/Cas9 and SgBim at the same time for 48 hours followed with puromycin selection for another 5 days as described previously22. Single cell clones were picked for screening for Bim knockout using Western blotting.

Table 1.

Osimertinib-resistant EGFR mutant NSCLC cell lines used in this study

| Resistant cell line | EGFR mutations | MET alteration | Resistance mechanisms | parental line |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line osimertinib resistance | ||||

| HCC827/AR | 19del | Amplification | MET amplification | HCC827 |

| PC-9/AR | 19del | None | Unknown | PC-9 |

| Second-line osimertinib resistance | ||||

| PC-9/GR/AR | 19del, T790M | None | Unknown | PC-9/GR |

| PC-9/3M | 19del, T790M, C797S | None | C797S | PC-9 |

Cell survival and apoptosis assays

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and treated the next day with the tested agents. After a given time period of treatment, viable cells were determined using sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay as described previously23. Combination index (CI) for drug interaction (e.g., synergy) was calculated using CompuSyn software (ComboSyn, Inc.; Paramus, NJ). Cell apoptosis was detected with an annexin V/7-AAD apoptosis detection kit (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. PARP was detected by Western blot analysis as an additional indicator of apoptosis.

Western blot analysis

Preparation of whole-cell protein lysates and Western blot analysis were the same as described previously21, 24.

Colony formation assays

The effects of the given drug treatments on colony formation in 12-well plates were assessed as previously described25.

Animal xenograft and treatments

Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Emory University and conducted as described previously21. The treatments include vehicle control, osimertinib (10 mg/kg/day, 5 days/week, og), LBH589 (10–5 mg/kg/day; ip) and their combination. Tumor volumes were measured using caliper measurements and calculated with the formula V = (length × width2)/2. At the end of the treatments, mice were weighed and euthanized with CO2 asphyxia. The tumors were then removed, weighed, and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences in tumor sizes or weights between two groups was analyzed with two-sided unpaired Student’s t tests when the variances were equal. Data were examined as suggested by the same software to verify that the assumptions for use of the t tests held. Differences among multiple treatment were analyzed with one-way ANOVA. Results were considered to be statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

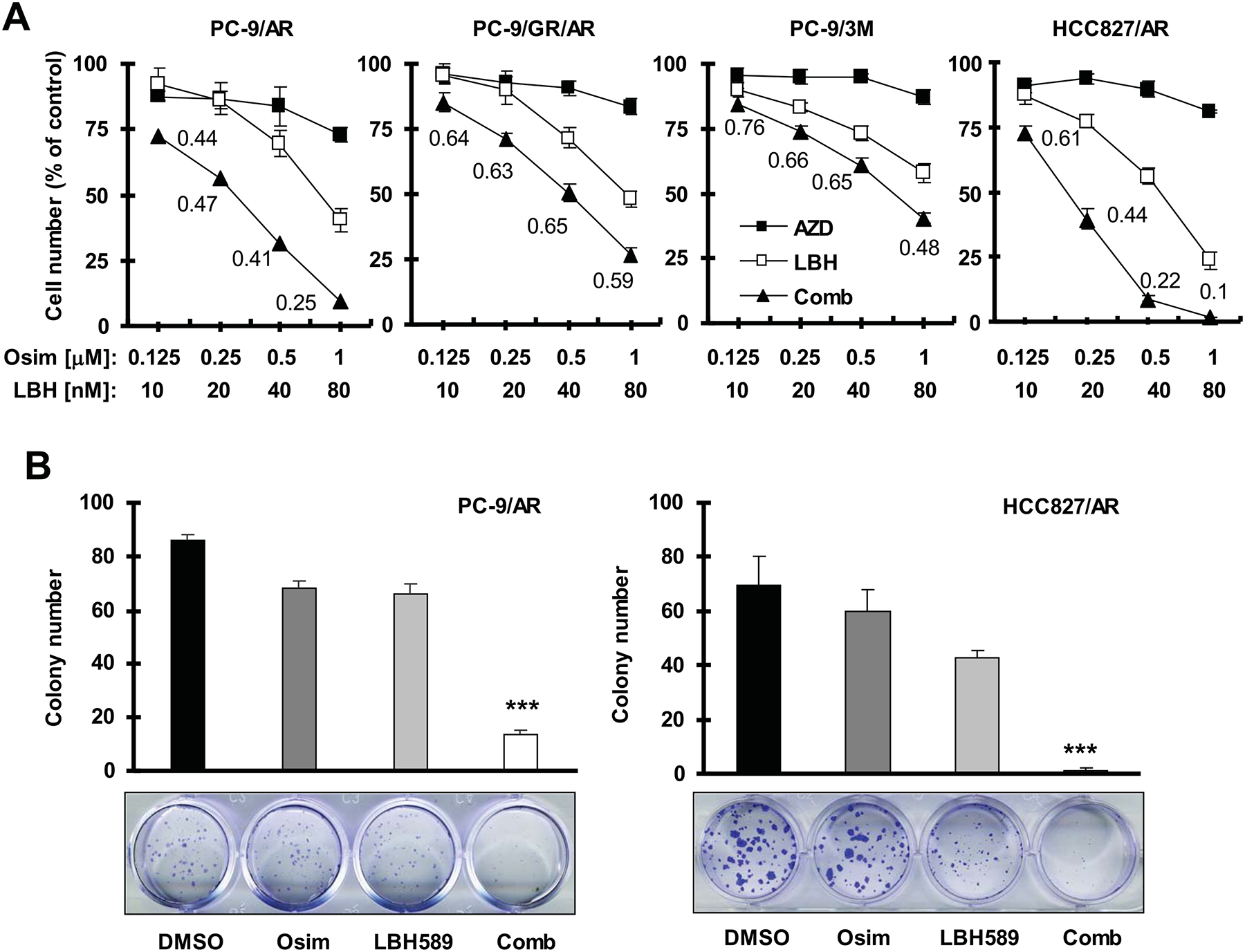

Osimertinib combined with LBH589 synergistically decreases the survival of different EGFR-mutant NSCLC cell lines with acquired resistance to AZD9291 and inhibits colony formation and growth

We first determined the effect of osimertinib combined with LBH589 on the growth of different osimertinib-resistant EGFR-mutant NSCLC cell lines including PC-9/AR, PC-9/GR/AR, PC-9/3M and HCC827/AR with varied resistance mechanisms (Table 1). Combinations of osimertinib and LBH589 in varied concentrations were more active than either agent alone in decreasing the survival of these cell lines. CIs were all < 1, indicating synergistic effects on decreasing the survival of these cell lines (Fig. 1A). In a different assay to measure cell colony formation and growth, we found that the combination of osimertinib and LBH589 was also significantly more effective than either single agent in suppressing the formation and growth of colonies in two representative osimertinib-resistant cell lines (Fig. 1B). Therefore, osimertinib, when combined with LBH589, effectively inhibits the growth of these osimertinib-resistant cell lines.

Fig. 1. The combination of LBH589 and osimertinib synergistically decreases the survival (A) and inhibits colony formation and growth (B) of osimertinib-resistant EGFR-mutant NSCLC cell lines.

A, The indicated cell lines seeded in 96-well plates were treated the next day with the given concentrations of AZD9291 alone, LBH589 alone or their combinations. After 72 hours, cell numbers were estimated using the SRB assay. The numbers inside the graphs are CIs for the given combinations. B. The indicated cell lines were seeded in 12-well cell culture plates. On the second day, the cells were treated with fresh medium containing DMSO, 5 nM (PC-9/AR) or 8 nM (HCC827/AR) LBH589 alone, 200 nM osimertinib alone and LBH589 plus osimertinib and the treatment was repeated every 3 days for a total of 12 days. The data are means ± SDs of four replicates (A) or triplicate (B) determinations. *** P < 0.001 at least compared with other treatments. Osim, osimertinib.

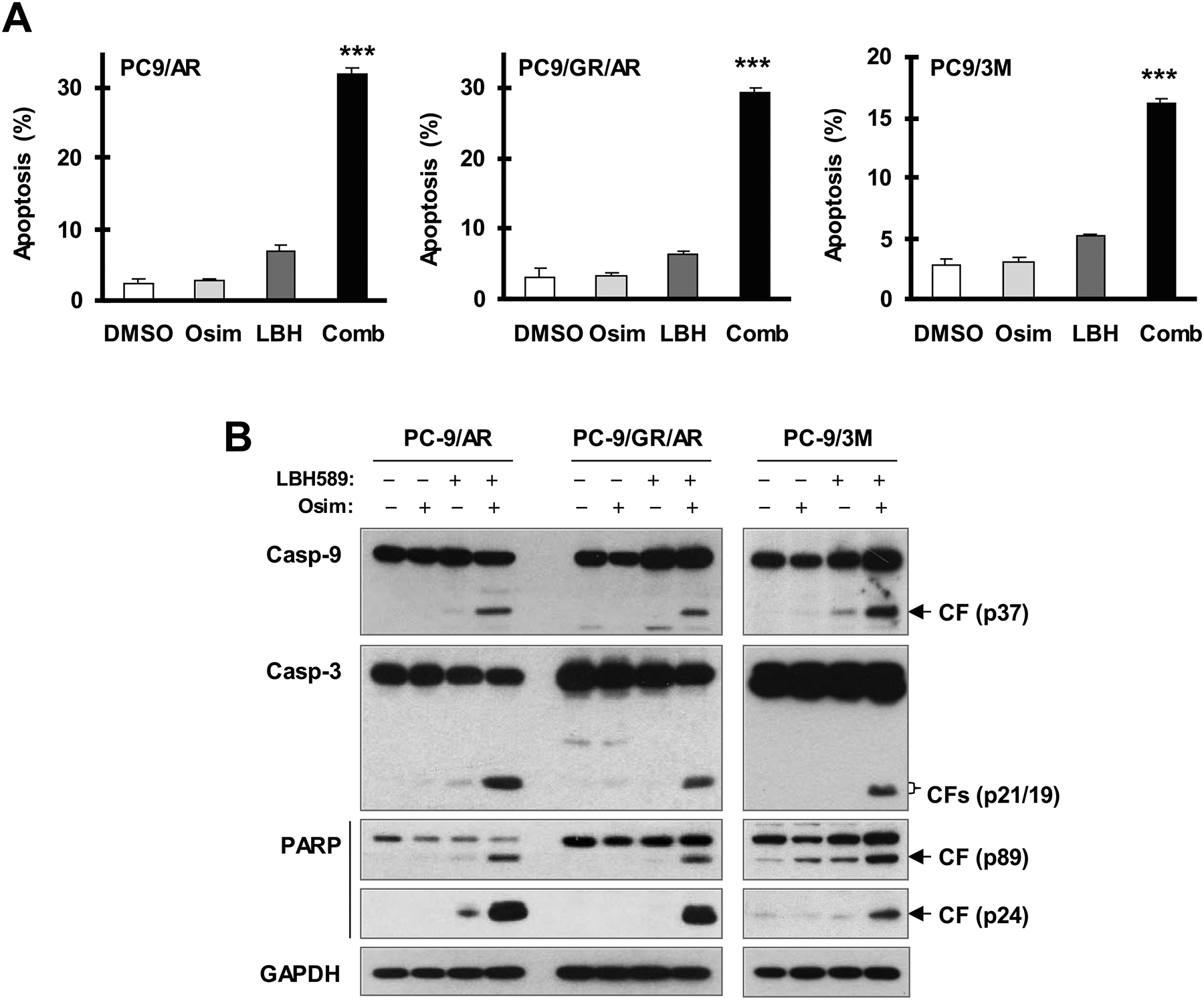

The combination of osimertinib and LBH589 enhances the induction of apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant cell lines

We then determined whether the combination of osimertinib and LBH589 augments the induction of apoptosis in these osimertinib-resistant cell lines. By measuring the proportion of annexin-V positive cells with flow cytometry, we found that the combination was much more potent than either agent alone in inducing apoptosis in PC-9/AR, PC-9/GR/AR and PC-9/3M cells (Fig. 2A). Similarly, we detected much higher levels of cleaved PARP, caspase-3 and caspase-9 in osimertinib-resistant cell lines exposed to the combination of osimertinib and LBH589 than in those treated with either agent alone (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these results show that osimertinib combined with LBH589 augments the induction of apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant cell lines.

Fig. 2. The combination of LBH589 and osimertinib enhances induction of apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant EGFR-mutant NSCLC cell lines.

The indicated cell lines were exposed to DMSO, 40 nM (PC-9/AR and PC-93M) or 60 nM (PC-9/GR/AR) LBH589, 0.5 μM osimertinib or LBH589 plus osimertinib for 48 h (A) or 40 h (B) and then harvested for detection of apoptosis with annexin V/flow cytometry (A) and for detection of PARP and caspase cleavage with Western blotting (B). The data in A are means ± SDs of triplicate determinations. *** P < 0.001 at least compared with other treatments. CF, cleaved form; Osim, osimertinib.

Osimertinib combined with LBH589 enhances Bim elevation through inhibiting its protein degradation in osimertinib-resistant cells

To gain insights into the molecular mechanism by which the combination of osimertinib and LBH589 enhances the induction of apoptosis, we compared the effects of the combination with those of each single agent alone on the levels of p-EGFR, p-Akt, p-ERK and several proteins critical for the regulation of apoptosis. We found that the combination of osimertinib and LBH589 induced higher levels of Bim in comparison with each agent alone with no apparent effects on Mcl-1, Bcl-1 and Bax levels in both PC-9/AR and PC-9/GR/AR cells. The combination was also more effective than each single agent in decreasing the levels of p-EGFR (Y1173), p-Akt and p-ERK in these resistant cell lines (Fig. 3A). The enhanced effect of the combination on increasing Bim levels occurred early at 4 h and was sustained for up to 24 h (Fig. 3B). Again, we did not see effects of the combination on decreasing Mcl-1 levels spanning the testes time points (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. The combination of LBH589 and osimertinib enhances Bim elevation (A and B) accompanied with augmented suppression of ERK and Akt (A) through stabilizing Bim protein (C) in osimertinib-resistant cells.

A and B, The indicated cell lines were exposed to 0.5 μM osimertinib alone, 40 nM LBH589 alone or their combination for 8 h (A) or for different times as indicated (B) and then harvested for preparation of whole-cell protein lysates and subsequent Western blot analysis. C, PC-9/GR/AR cells were treated with DMSO, 40 nM LBH589, 0.5 μM osimertinib or LBH589 and osimertinib combination for 8 h followed by addition of 10 μg/ml CHX. At the indicated times post CHX, the cells were harvested for preparation of whole-cell protein lysates and subsequent Western blot analysis. Band intensities were quantified by NIH image J software and Bim levels presented as a percentage of levels at 0 time post CHX treatment. Osim, osimertinib.

We recently reported that p-ERK suppression is associated with suppression of Bim phosphorylation and Bim stabilization induced by osimertinib in sensitive EGFR-mutant NSCLC cells21. We therefore asked whether the combination of osimertinib and LBH589 enhances Bim stabilization, resulting in enhanced Bim elevation in osimertinib-resistant cells. CHX assay showed that Bim was degraded more slowly in PC-9/GR/AR cells treated with the osimertinib and LBH589 combination than in those exposed to DMSO control, AZD9291 or LBH589 (Fig. 3C). This result suggests that the combination of osimertinib and LBH589 slows down Bim degradation in osimertinib-resistant cells. Interestingly, we did not see enhanced effects of the combination on suppressing phosphorylation of both Bim and Mcl-1 (Fig. 3A).

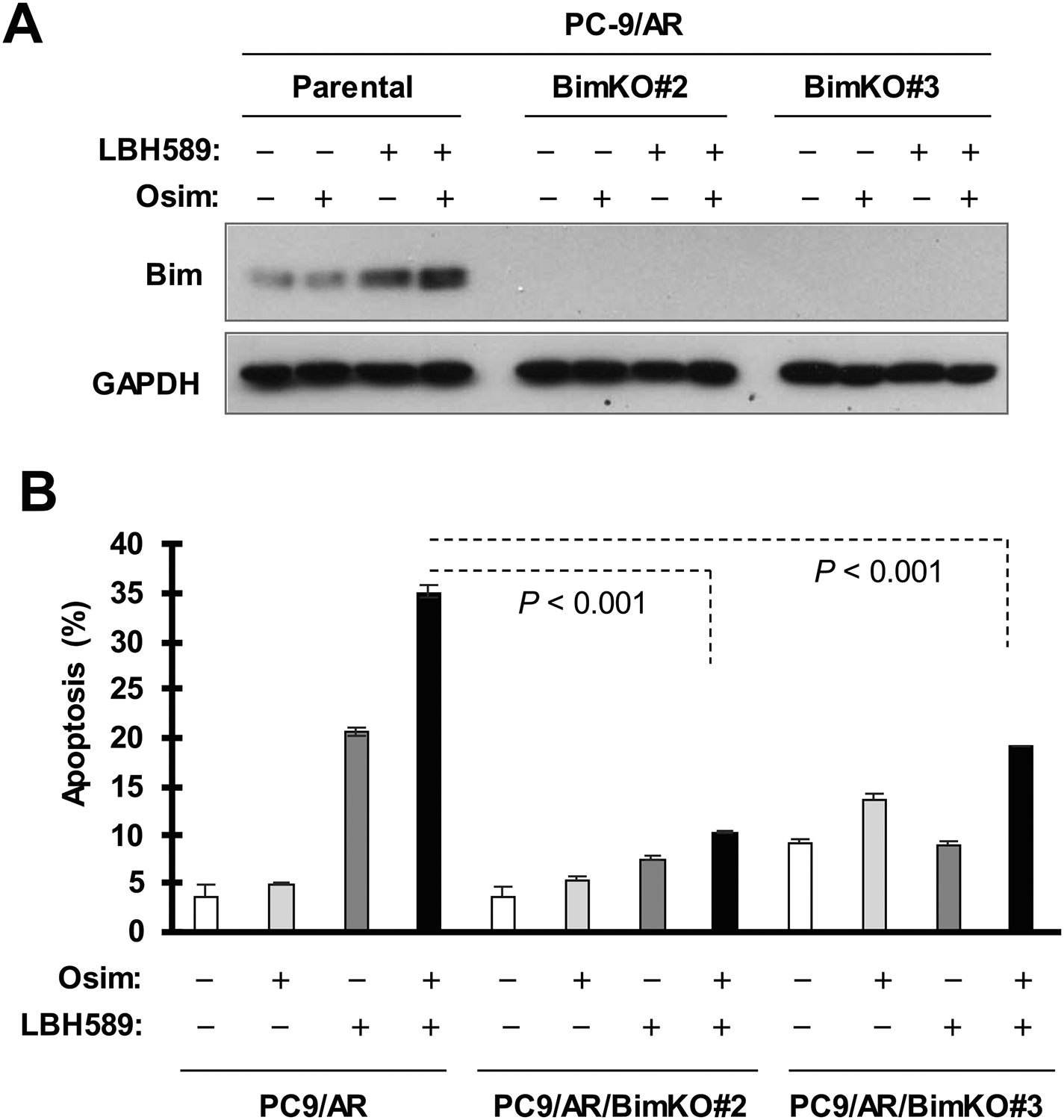

Bim knockout in osimertinib-resistant cells confers resistance to the combination of osimertinib and LBH589

We next determined whether enhanced Bim elevation plays a critical role in mediating the augmented induction of apoptosis by osimertinib and LBH589 combination. We knocked out Bim using the CRISPR/cas9 technique in PC-9/AR cells and then determined cell response to the combination of osimertinib and LBH589. Bim knockout in two Bim KO cell lines was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 4A). In comparison with the effect in PC-9/AR parental cells, the apoptosis-inducing effects of the osimertinib and LBH589 combination in PC-9/AR/BimKO#2 and PC-9/AR/BimKO#3 were significantly compromised as assessed by flow cytometry for annexin V-positive cells (Fig. 4B). Collectively, these results suggest that Bim elevation is a critical event that mediates the enhanced induction of apoptosis by the combination of osimertinib and LBH589.

Fig. 4. Bim knockout compromises the ability of the LBH589 and osimertinib combination to enhance the induction of apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant cells.

The indicated cell lines were exposed to 0.5 μM osimertinib alone, 40 nM LBH589 alone or their combination for 40 h (A) or 48 h (B) and then harvested for detection of Bim (A) and for measurement of apoptotic cells with Annexin V/flow cytometry (B). The data in B are means ± SDs of duplicate determinations. Osim, osimertinib.

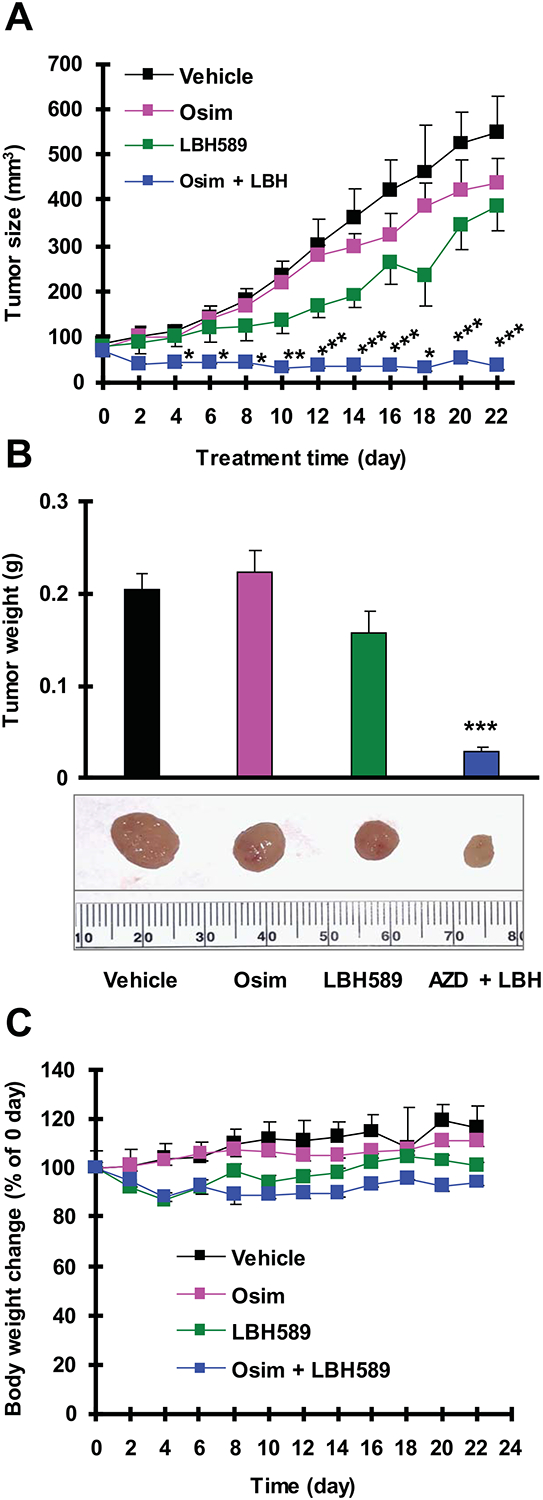

The combination of osimertinib and LBH589 effectively inhibits the growth of osimertinib-resistant xenografts in nude mice

Finally, we determined whether the combination of osimertinib and LBH589 exerts enhanced inhibitory effect against the growth of osimertinib-resistant tumor in vivo. The combination of osimertinib and LBH589 significantly inhibited the growth of PC-9/AR xenografts compared with vehicle control, LBH589 alone or osimertinib alone by evaluating both tumor size (Fig. 5A) and weight (Fig. 5B). Treatment with LBH589 at 10 mg/kg initially decreased body weight. When the dose was reduced to 5 mg/kg on day 7, we observed that the body weights of the mice were not further reduced. A similar observation was made with the combination of osimertinib and LBH589 (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that the combination can be tolerated by mice if we modulate the dose of LBH589.

Fig. 5. The combination of LBH589 and osimertinib effectively inhibits the growth of PC-9/AR xenografts in vivo.

PC-9/AR xenografts were treated (once a day for 5 days/week) with vehicle control, osimertinib, LBH589 and their combination starting on the same day after grouping for 3 weeks. Tumor sizes (A) were measured as indicated. Each measurement is mean ± SEM (n = 6). At the end of the treatment, the mice were sacrificed to remove tumors, which were weighed (B). Mouse body weights were also compared (C). * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001 at least compared with all other groups. Osim, osimertinib.

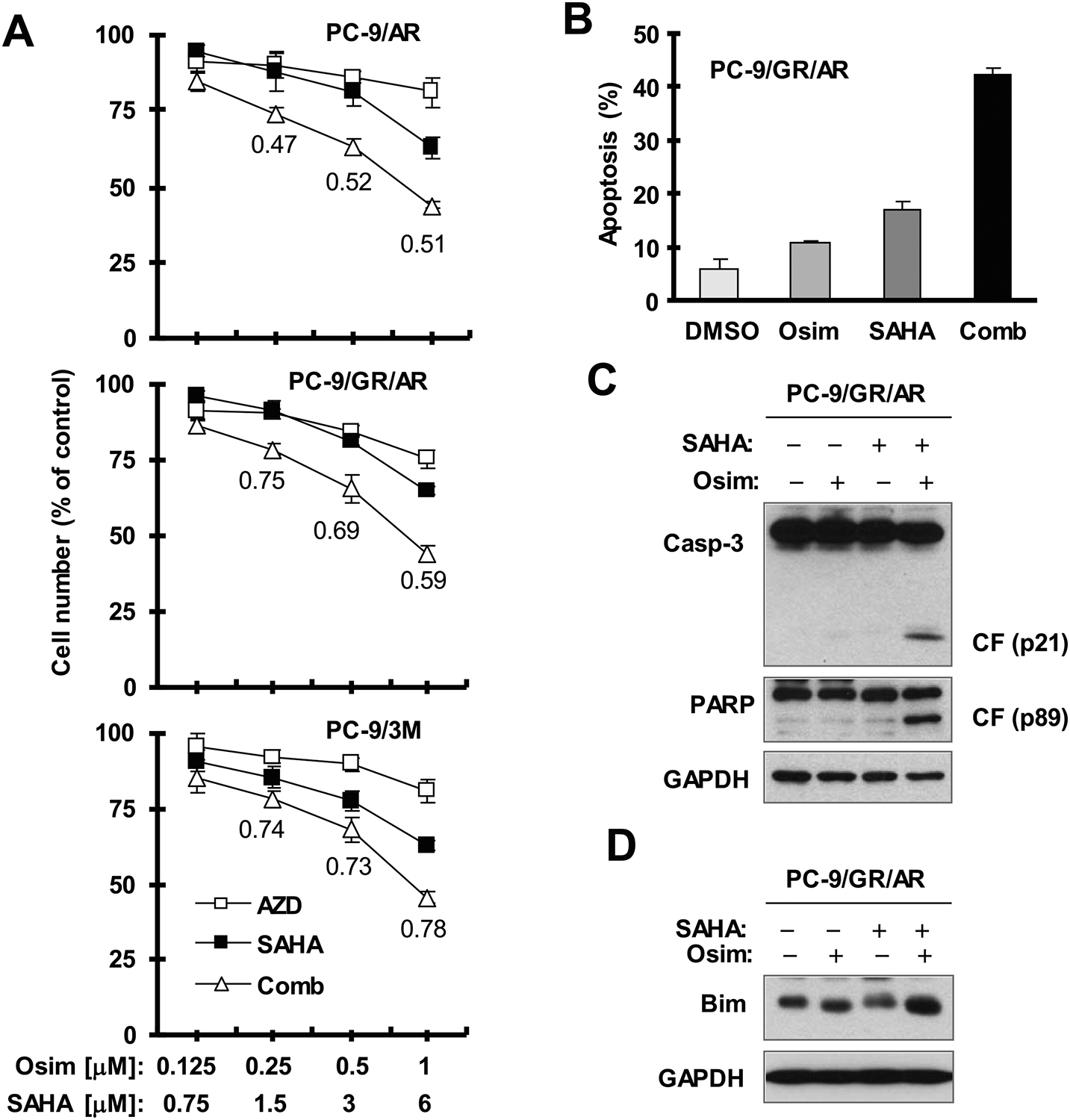

SAHA, another HDAC inhibitor, functions similarly to LBH589 in synergistically decreasing the survival and enhancing apoptosis of different osimertinib-resistant NSCLC cell lines

To explore whether other HDAC inhibitors exert similar effects as LBH589 in overcoming osimertinib resistance, we further compared the effects of osimertinib on cell survival and apoptosis in the absence and presence of SAHA, another clinically-used HDAC inhibitor. We found that the combination of SAHA and osimertinib synergistically decreased the survival of different osimertinib-resistant cell lines, with CIs of < 1 (Fig. 6A). Moreover, the combination of SAHA and osimertinib was more active than each agent alone in inducing apoptosis as assessed by evaluating annexin V-positive cells (Fig. 6B) and cleavage of PARP and caspase-3 (Fig. 6C), indicating the enhancement of apoptosis induction. Furthermore, the combination was also much more potent than either agent alone in elevating Bim levels (Fig. 6D). Hence, SAHA exerts similar effects as LBH589 in synergistically decreasing the survival and enhancing the apoptosis of osimertinib-resistant NSCLC cells with augmented effect on elevating Bim levels.

Fig. 6. The combination of SAHA and osimertinib synergistically decreases the survival (A) and induces apoptosis (B) of osimertinib-resistant NSCLC cell lines.

A, The indicated cell lines seeded in 96-well plates were treated the next day with the given concentration of osimertinib alone, SAHA alone or their combinations. After 72 hours, cell numbers were estimated using the SRB assay. The numbers inside the graphs are CIs for the given combinations. B-D. PC-9/GR/AR cells were exposed to DMSO, 6 μM SAHA, 0.5 μM osimertinib or SAHA plus osimertinib for 48 h (B), 40 h (C) or 12 h (D) and then harvested for detection of apoptosis with annexin V/flow cytometry (B) and for detection of different proteins with Western blotting (C and D). The data in B are means ± SDs of duplicate determinations. CF, cleaved form; Osim, osimertinib.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the combination of osimertinib with the pan-HDAC inhibitor, LBH589, effectively inhibited the growth of different osimertinib-resistant cells and tumors, demonstrating the potential of LBH589 in overcoming acquired resistance to osimertinib. Notably, this combination was also effective in decreasing the survival and inducing apoptosis of PC-9/3M cells, which carry the C797S resistance mutation that is a newly defined mechanism for the emergence of acquired resistance to osimertinib and accounts for 20–30% of osimertinib-resistant cases in the clinic26 in addition to 19del and T790M mutations. Given the lack of effective options for the treatment of resistant tumors with triple mutations of EGFR at 19del, T790M and C797S, our findings are of particular significance in terms of treating C797S-induced osimertinib resistance.

Osimertinib, when combined with LBH589, enhanced apoptosis in the tested osimertinib-resistant cell lines. These data suggest that augmented induction of apoptosis is an important mechanism accounting for the enhanced antitumor activity against osimertinib-resistant cells and tumors by the combination of osimertinib and LBH589. Bim elevation is a key mechanism underlying osimertinib-induced apoptosis in sensitive EGFR-mutant NSCLC cells as we recently demonstrated21. In this study, augmented elevation of Bim was observed in the tested osimertinib-resistant cell lines exposed to the osimertinib and LBH589 combination, suggesting a possible role of Bim elevation in mediating the enhanced induction of apoptosis by the combination. Direct evidence in support of this notion came from the finding that Bim knockout in PC-9/AR cells protected the cells from undergoing apoptosis induced by the combination of osimertinib and LBH589.

ERK phosphorylates Bim protein, facilitating its degradation27–30. Osimertinib inhibits ERK-dependent Bim phosphorylation and delays Bim degradation, leading to Bim elevation in sensitive EGFR-mutant NSCLC cells21. In this study, the combination of osimertinib and LBH589 had enhanced effects on decreasing the levels of p-ERK while increasing Bim levels. Moreover, the combination of osimertinib and LBH589 slowed down Bim degradation as measured by CHX chase assay, indicating the stabilization of Bim. Hence, it is reasonable to conclude that the combination of osimertinib and LBH589 enhances the elevation of Bim expression through suppression of its degradation. However, we did not see enhanced effect of the combination on decreasing Bim phosphorylation at S69. Beyond Bim stabilization, osimertinib also decreases Mcl-1 levels through facilitating ERK-mediated protein degradation in sensitive EGFR mutant NSCLC cells or in osimertinib-resistant NSCLC cells when combined with MEK inhibition21. In the current study, the combination of LBH589 and osimertinib did suppress Mcl-1 phosphorylation and decrease Mcl-1 levels as well. Therefore, it is likely that enhanced Bim elevation caused by the combination of LBH589 and osimertinib is independent of ERK suppression.

Beyond LBH589, SAHA, another pan-HDAC inhibitor, exerted similar effects as LBH589 in synergizing with osimertinib in decreasing survival, elevating Bim and enhancing apoptosis of osimertinib-resistant NSCLC cells, showing potential to overcome osimertinib acquired resistance. We thus reasonably speculate that LBH589’s activity in synergizing with osimertinib in enhancing Bim-dependent apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant cells and suppressing the growth of osimertinib-resistant tumors is likely associated with its HDAC-inhibitory activity. Bim deletion polymorphism, which occurs at a frequency of 21% in East Asians but is absent in African and European populations, has been associated with resistance to osimertinib17, 31. It was reported that HDAC inhibition (e.g., with SAHA) combined with osimertinib overcomes Bim deletion polymorphism-mediated osimertinib resistance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer17. Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that LBH589 combined with osimertinib may also be effective in overcoming osimertinib resistance caused by Bim deletion polymorphism.

In conclusion, the current study has identified HDAC inhibition as a potential strategy for overcoming acquired resistance to osimertinib caused by varied mechanisms including C797S mutation. Given that both LBH589 and SAHA are approved anti-cancer drugs, our findings thus provide strong preclinical rationale for testing this potential strategy for overcoming osimertinib acquired resistance in the clinic and warrant further study to fully understand the underlying molecular mechanisms. In addition to the pan-HDAC inhibitors as tested in this study, there are other isoform-specific HDAC inhibitors under development7, 32, whether these inhibitors have advantage over the pan-HDAC inhibitors on overcoming acquired resistance to osimertinib in terms of efficacy and safety is also worthy of further study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful to Dr. A. N. Hata for providing PC-9/3M cell line. We also thank Dr. Anthea Hammond in our department for editing the manuscript. TKO and SSR and SYS are Georgia Research Alliance Distinguished Cancer Scientists.

Funding support: This study was supported in part by NIH/NCI R01 CA223220 (to SYS) and UG1 CA233259 (to SSR and SYS), Emory University Winship Cancer Institute lung cancer pilot fund (to S-Y. S.) and Lee Foundation Award to the Winship Lung Cancer Program for supporting the pilot project (to SSR and SYS).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosures: SSR is on consulting/advisory board for AstraZeneca, BMS, Merck, Roche, Tesaro and Amgen. TKO is on consulting/advisory board for Novartis, Celgene, Lilly, Sandoz, Abbvie, Eisai, Takeda, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MedImmune, Amgen, AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim. Other people made no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Russo A, Franchina T, Ricciardi GRR, et al. Third generation EGFR TKIs in EGFR-mutated NSCLC: Where are we now and where are we going. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;117: 38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tartarone A, Lerose R. Clinical approaches to treat patients with non-small cell lung cancer and epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor acquired resistance. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2015;9: 242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juchum M, Gunther M, Laufer SA. Fighting cancer drug resistance: Opportunities and challenges for mutation-specific EGFR inhibitors. Drug Resist Updat. 2015;20: 10–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Remon J, Moran T, Majem M, et al. Acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer: A new era begins. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40: 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Govindan R Overcoming resistance to targeted therapy for lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372: 1760–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramalingam SS, Yang JC, Lee CK, et al. Osimertinib As First-Line Treatment of EGFR Mutation-Positive Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017: JCO2017747576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Seto E. HDACs and HDAC Inhibitors in Cancer Development and Therapy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClure JJ, Li X, Chou CJ. Advances and Challenges of HDAC Inhibitors in Cancer Therapeutics. Adv Cancer Res. 2018;138: 183–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witta SE, Gemmill RM, Hirsch FR, et al. Restoring E-cadherin expression increases sensitivity to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2006;66: 944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruzzese F, Leone A, Rocco M, et al. HDAC inhibitor vorinostat enhances the antitumor effect of gefitinib in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck by modulating ErbB receptor expression and reverting EMT. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226: 2378–2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakagawa T, Takeuchi S, Yamada T, et al. EGFR-TKI resistance due to BIM polymorphism can be circumvented in combination with HDAC inhibition. Cancer Res. 2013;73: 2428–2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen MC, Chen CH, Wang JC, et al. The HDAC inhibitor, MPT0E028, enhances erlotinib-induced cell death in EGFR-TKI-resistant NSCLC cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4: e810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee TG, Jeong EH, Kim SY, Kim HR, Kim CH. The combination of irreversible EGFR TKIs and SAHA induces apoptosis and autophagy-mediated cell death to overcome acquired resistance in EGFR T790M-mutated lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;136: 2717–2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park SJ, Kim SM, Moon JH, et al. SAHA, an HDAC inhibitor, overcomes erlotinib resistance in human pancreatic cancer cells by modulating E-cadherin. Tumour Biol. 2016;37: 4323–4330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liffers K, Kolbe K, Westphal M, Lamszus K, Schulte A. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors Resensitize EGFR/EGFRvIII-Overexpressing, Erlotinib-Resistant Glioblastoma Cells to Tyrosine Kinase Inhibition. Target Oncol. 2016;11: 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greve G, Schiffmann I, Pfeifer D, Pantic M, Schuler J, Lubbert M. The pan-HDAC inhibitor panobinostat acts as a sensitizer for erlotinib activity in EGFR-mutated and -wildtype non-small cell lung cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2015;15: 947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanimoto A, Takeuchi S, Arai S, et al. Histone Deacetylase 3 Inhibition Overcomes BIM Deletion Polymorphism-Mediated Osimertinib Resistance in EGFR-Mutant Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23: 3139–3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu W, Lu W, Chen G, et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylases sensitizes EGF receptor-TK inhibitor-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer cells to erlotinib in vitro and in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174: 3608–3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Citro S, Bellini A, Miccolo C, Ghiani L, Carey TE, Chiocca S. Synergistic antitumour activity of HDAC inhibitor SAHA and EGFR inhibitor gefitinib in head and neck cancer: a key role for DeltaNp63alpha. Br J Cancer. 2019;120: 658–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buendia Duque M, Pinheiro KV, Thomaz A, et al. Combined Inhibition of HDAC and EGFR Reduces Viability and Proliferation and Enhances STAT3 mRNA Expression in Glioblastoma Cells. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;68: 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi P, Oh YT, Deng L, et al. Overcoming Acquired Resistance to AZD9291, A Third-Generation EGFR Inhibitor, through Modulation of MEK/ERK-Dependent Bim and Mcl-1 Degradation. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23: 6567–6579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian G, Yao W, Zhang S, et al. Co-inhibition of BET and proteasome enhances ER stress and Bim-dependent apoptosis with augmented cancer therapeutic efficacy. Cancer Lett. 2018;435: 44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun SY, Yue P, Dawson MI, et al. Differential effects of synthetic nuclear retinoid receptor-selective retinoids on the growth of human non-small cell lung carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57: 4931–4939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi P, Oh YT, Zhang G, et al. Met gene amplification and protein hyperactivation is a mechanism of resistance to both first and third generation EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer treatment. Cancer Lett. 2016;380: 494–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Hawk N, Yue P, et al. Overcoming mTOR inhibition-induced paradoxical activation of survival signaling pathways enhances mTOR inhibitors’ anticancer efficacy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7: 1952–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murtuza A, Bulbul A, Shen JP, et al. Novel Third-Generation EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Strategies to Overcome Therapeutic Resistance in Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79: 689–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ley R, Balmanno K, Hadfield K, Weston C, Cook SJ. Activation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway promotes phosphorylation and proteasome-dependent degradation of the BH3-only protein, Bim. J Biol Chem. 2003;278: 18811–18816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ley R, Ewings KE, Hadfield K, Cook SJ. Regulatory phosphorylation of Bim: sorting out the ERK from the JNK. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12: 1008–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ley R, Ewings KE, Hadfield K, Howes E, Balmanno K, Cook SJ. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 are serum-stimulated “Bim(EL) kinases” that bind to the BH3-only protein Bim(EL) causing its phosphorylation and turnover. J Biol Chem. 2004;279: 8837–8847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luciano F, Jacquel A, Colosetti P, et al. Phosphorylation of Bim-EL by Erk1/2 on serine 69 promotes its degradation via the proteasome pathway and regulates its proapoptotic function. Oncogene. 2003;22: 6785–6793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Wang S, Li B, et al. BIM Deletion Polymorphism Confers Resistance to Osimertinib in EGFR T790M Lung Cancer: a Case Report and Literature Review. Target Oncol. 2018;13: 517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah RR. Safety and Tolerability of Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibitors in Oncology. Drug Saf. 2019;42: 235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]