Abstract

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has attracted extensive attention in recent years as a noninvasive and locally targeted cancer treatment approach. Nanoparticles have been used to improve the solubility and pharmacokinetics of the photosensitizers required for PDT; however, nanoparticles also suffer from many shortcomings including uncontrolled drug release and low tumor accumulation. Herein, we describe a novel biodegradable nanoplatform for the delivery of the clinically used PDT photosensitizer benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid ring A (BPD-MA) to tumors. Specifically, the hydrophobic photosensitizer BPD was covalently conjugated to the amine groups of a dextran-b-oligo (amidoamine) (dOA) dendron copolymer, forming amphiphilic dextran-BPD conjugates that can self-assemble into nanometer-sized micelles in water. To impart additional imaging capabilities to these micelles, superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) were encapsulated within the hydrophobic core to serve as a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agent. The use of a photosensitizer as a hydrophobic building block enabled facile and reproducible synthesis and high drug loading capacity (~30%, w/w). Furthermore, covalent conjugation of BPD to dextran prevents the premature release of drug during systemic circulation. In vivo studies show that the intravenous administration of dextran-BPD coated SPION nanoparticles results in significant MR contrast enhancement within tumors 24 h postinjection and PDT led to a significant reduction in the tumor growth rate.

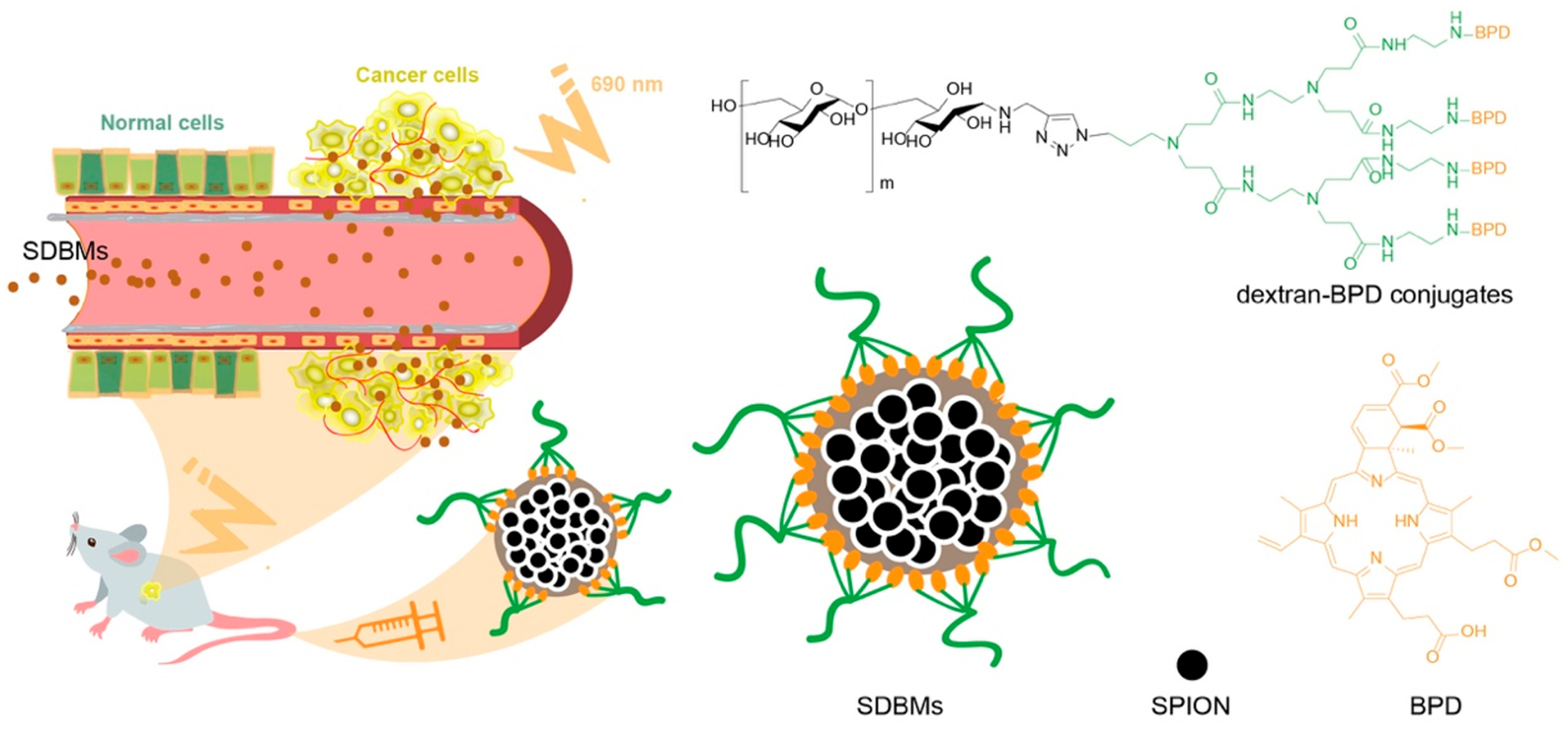

Graphical Abstarct

INTRODUCTION

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an FDA-approved cancer treatment. PDT combines photosensitizers (PS) with nonionizing light to generate singlet oxygen to kill cancer cells in the illuminated area.1 FDA approved PS (e.g., Photofrin, Protoporphyrin IX, BPD-MA) are small compounds whose application is constrained by their poor solubility and unfavorable pharmacokinetics.2–4 Moreover, limitations in tumor selectivity after systemic administration of these drugs can result in undesirable side effects in vivo upon illumination.2–4 For example, damage of normal lung and other thoracic organs during PDT for lung cancer can result from the delivery of illumination over large areas that consist of both tumor and normal tissue in conjunction with limitations in photosensitizer selectivity for the tumor.5–8 Therefore, developing innovative strategies to improve the delivery of PS to tumors and enhance the efficacy of PDT has been a long-sought goal.

It is expected that PDT can be improved by formulating PS into nanoparticulate platforms, due to the favorable pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and solubility of nanoparticles compared with free photosensitizers.9,10 Furthermore, if photosensitizers and imaging agents are combined into a single formulation at the nanoscale level, the formed theranostic agents could provide important insight into the localization of the drug and pathological process longitudinally.11 Currently, a wide range of nanoparticle platforms including micelles, dendrimers, liposomes, polymersomes, and silica nanoparticles, have been explored as carriers for the delivery of PS.9,12–17 Among the many nanoparticulate systems, polymeric micelles are particularly attractive due to their facile synthesis, relatively small size, and ability to solubilize hydrophobic drugs and imaging agents.18–21 In most cases, the PS-loaded polymeric micelles are formed by encapsulating PS within the hydrophobic core of polymeric micelles via noncovalent interactions. However, while these polymeric micelles are able to overcome certain limitations associated with the current PS, the uncontrolled drug release upon systemic injection still remains a major concern. For example, protoporphyrin IX (PpIX)-loaded poly(ethylene glycol)-polycaprolactone (PEG–PCL) micelles exhibited ~50% PpIX leakage in serum after intravenous administration.17 PDT with these micelles did not lead to a significant reduction in tumor volume even at a high dose (40 mg PpIX/kg).16 To address this concern, we developed a new method to prepare biodegradable polymeric micelles whereby the PS is covalently linked to the micelle (Figure 1).

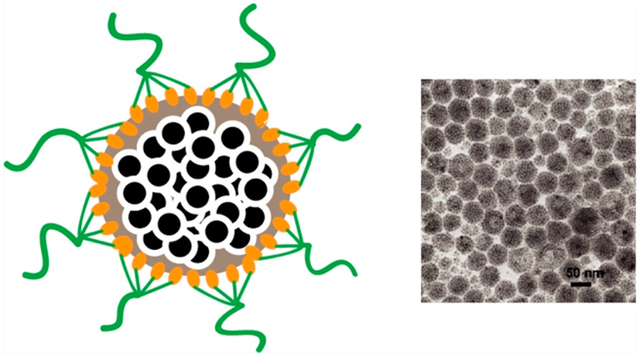

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of self-assembled SPION loaded dextran-BPD micelles (SDBMs) for photodynamic therapy. Micelles were formed through the coassembly of the small hydrophobic SPIONs and the dextran-BPD conjugates. Due to amphiphilic property of dextran-BPD, the dextran-BPD conjugates were able to coat onto the densely packed SPION core.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis of Dextran-BPD Conjugates.

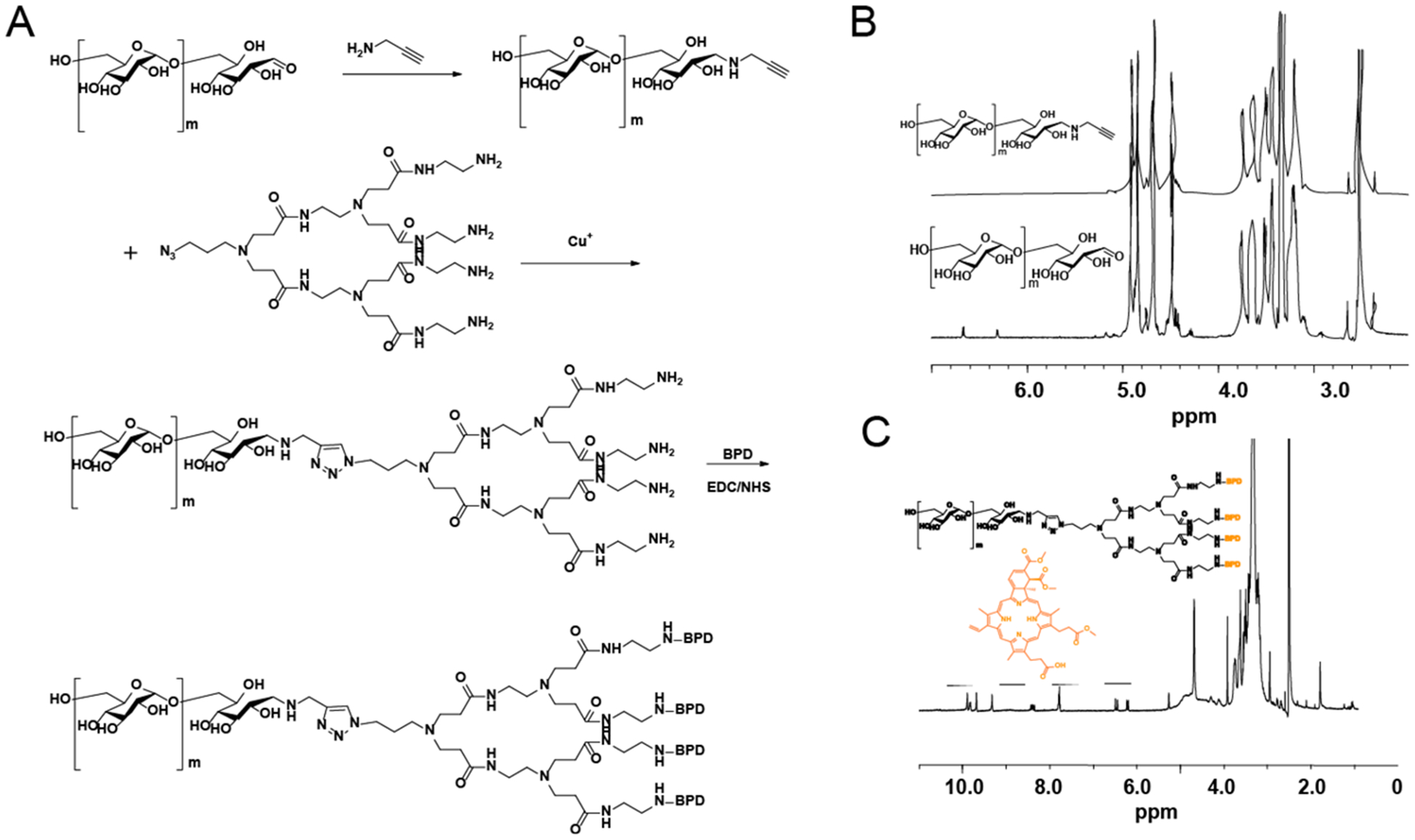

The hydrophobic photosensitizer BPD was covalently linked to the amine terminal of the copolymer, dextran-b-oligo (amidoamine) (dOA) dendron (Figure 2A). To prepare dextran-b-dOA, dextran-alkynyl was first prepared by amination of dextran terminal aldehyde with propargylamine in the presence of sodium cyanoborohydride (NaCNBH3). Then, the click reaction between dextran-alkynyl and azide (N3)-dOA (Figures S1 and S2) was conducted in the presence of CuSO4 and sodium ascorbate at 45 °C. Finally, the dextran-BPD conjugates were prepared by conjugation of BPD to the periphery amine groups of dOA, according to the EDC/NHS method. 1H NMR (Figure 2B) confirmed that α-alkyne dextran was successfully synthesized, as indicated by the disappearance of the characteristic resonances of the anomeric proton peaks of the reducing end group at 6.7 and 6.3 ppm. The successful coupling of BPD onto dextran-dOA was also confirmed by the appearance of aromatic protons of BPD from 6–10 ppm in 1H NMR (Figure 2C). The degree of conjugation for BPD in the dextran-BPD conjugates was further determined by a UV–vis spectrophotometer. It was calculated that ~3 BPD molecules were conjugated onto each dextran, resulting in a ~ 30% (w/w) drug loading content. Due to π−π stacked self-aggregation among hydrophobic PS molecules, dextran-BPD conjugates are amphiphilic in nature allowing for the facile formation of micelles.

Figure 2.

Synthesis and characterization of dextran-BPD. (A) The synthetic pathway to prepare the liner-dendritic dextran-BPD. (B) 1H NMR of dextran and dextran-alkyne. (C) 1H NMR of dextran-BPD.

Synthesis and Characterization of SPIO-Loaded Dextran-BPD micelles.

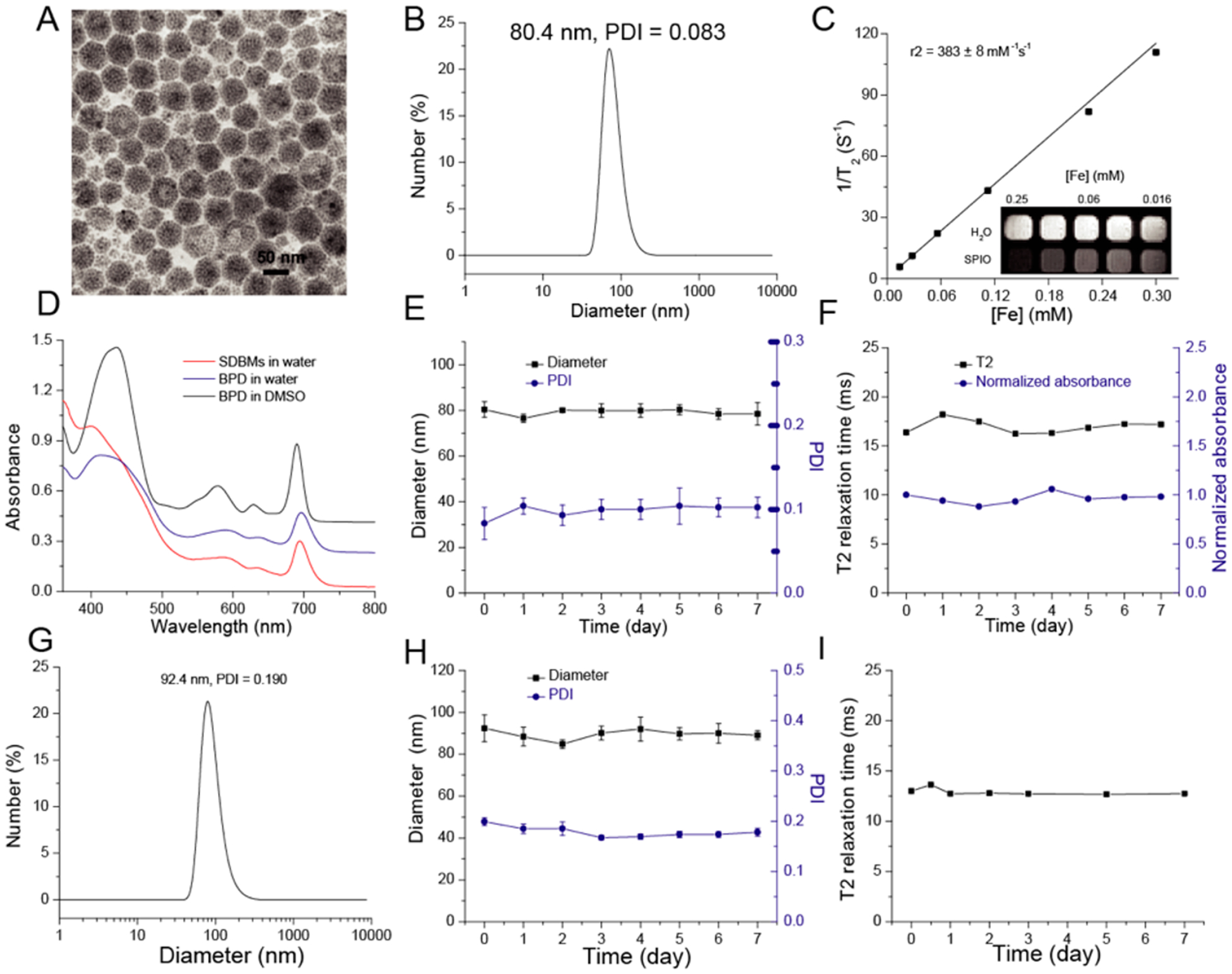

To add imaging capabilities to therapeutic micelles, we synthesized a dual-functional nanoplatform consisting of photosensitizer BPD and magnetic contrast agent SPIONs, with well-aligned phototherapeutic and diagnostic properties. SPION-loaded dextran-BPD mi celles (SDBMs) were prepared based on an oil in water microemulsion method.16 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images revealed that the small hydrophobic SPION (~10 nm in diameter) were densely packed within the micelle cores, which had overall diameters around 60 nm (Figure 3A). The average hydrodynamic diameter was approximately 80.4 nm measured by DLS (PDI < 0.1; Figure 3B), which is larger than measured by TEM, likely due to the hydration of surface coated dextran in the aqueous solution. SDBMs possessed an r2 value of 383 mM−1 s−1 (Figure 3C), which is much higher than r2 value of commercial dextran-coated SPION (Ferumoxytol r2:55.26 mM−1 s−1). Moreover, since tens of SPIONs can be densely packed within one single micelle, the SPION-loaded micelles can generate a relaxivity that is amplified by another ~10-fold or more on a per micelle basis, compared to common dextran-coated SPION (Figure S3A, S3B), which only contain several iron-core nanoparticles (Figure S3A, inset). Therefore, SDBMs are highly sensitive for noninvasive MR imaging. In addition, the synthetic method is simple and cost-effective since all components were included in the starting materials prior to micelle formation, which allows for precise control over nanoparticle synthesis.

Figure 3.

Characterization of the SDBMs. (A) TEM image of the SDBMs. (B) DLS of the SDBMs in water. (C) Magnetic resonance (MR) relaxometry measurements of the SDBMs. MR phantom image (inset) of the SDBMs at various concentrations was also collected. (D) UV spectrum of the SDBMs and free BPD at BPD concentration of 10 μg/mL. (E) The SDBMs were incubated in water, at 4 °C, and diameter and PDI were recorded as a function of time. (F) The SDBMs were incubated in water, at 4 °C, and relaxometry measurements and UV absorbance were recorded as a function of time. (G) DLS of the SDBMs in DMEM. (H) The SDBMs were incubated in DMEM with 10% serum, at 37 °C, and diameter PDI were recorded as a function of time. (F) The SDBMs were incubated in DMEM with 10% serum, at 37 °C, and relaxometry measurements was recorded as a function of time.

To evaluate the optical properties of the BPD encapsulated in SDBMs, the absorbance and fluorescence spectrum were acquired. As shown in Figure 3D, the absorption of BPD within SDBMs was similar to that of free BPD in water and DMSO, indicating that BPD remains intact following the synthetic procedure. However, the fluorescence intensity of SDBMs was much higher than that of free BPD in water (Figure S4). This may be due to the high degree of BPD aggregation when BPD is suspended in water, leading to a highly quenched state.

Next, the stability of SDBMs was evaluated under different conditions, i.e, in water at 4 °C and DMEM with 10% FBS at 37 °C. There was no observable change in the hydrodynamic diameter and PDI (Figure 3E) or in the T2 relaxation time (Figure 3F) of the micelles in water at 4 °C for at least 1 week, indicating that there is no aggregation or precipitation of the nanoparticles over this time period. In addition, there was no significant change in the UV-absorption spectrum or any detectable dissociation of the BPD from the nanoparticles under the same conditions (Figure 3F). Meanwhile, there was an initial increase in the hydrodynamic diameter of the micelles from ~80.4 to ~92.4 nm (Figure 3G) when the micelles were incubated in DMEM for a week at 37 °C, most likely due to opsonization and formation of a protein corona, but there was no significant change in the hydrodynamic diameter and PDI thereafter (Figure 3H). There was also no change in the T2 relaxation time (Figure 3I), further indicating that there is no aggregation and that the prepared SDBMs could be stable in circulation after systemic administration.

Cellular Uptake of Micelles.

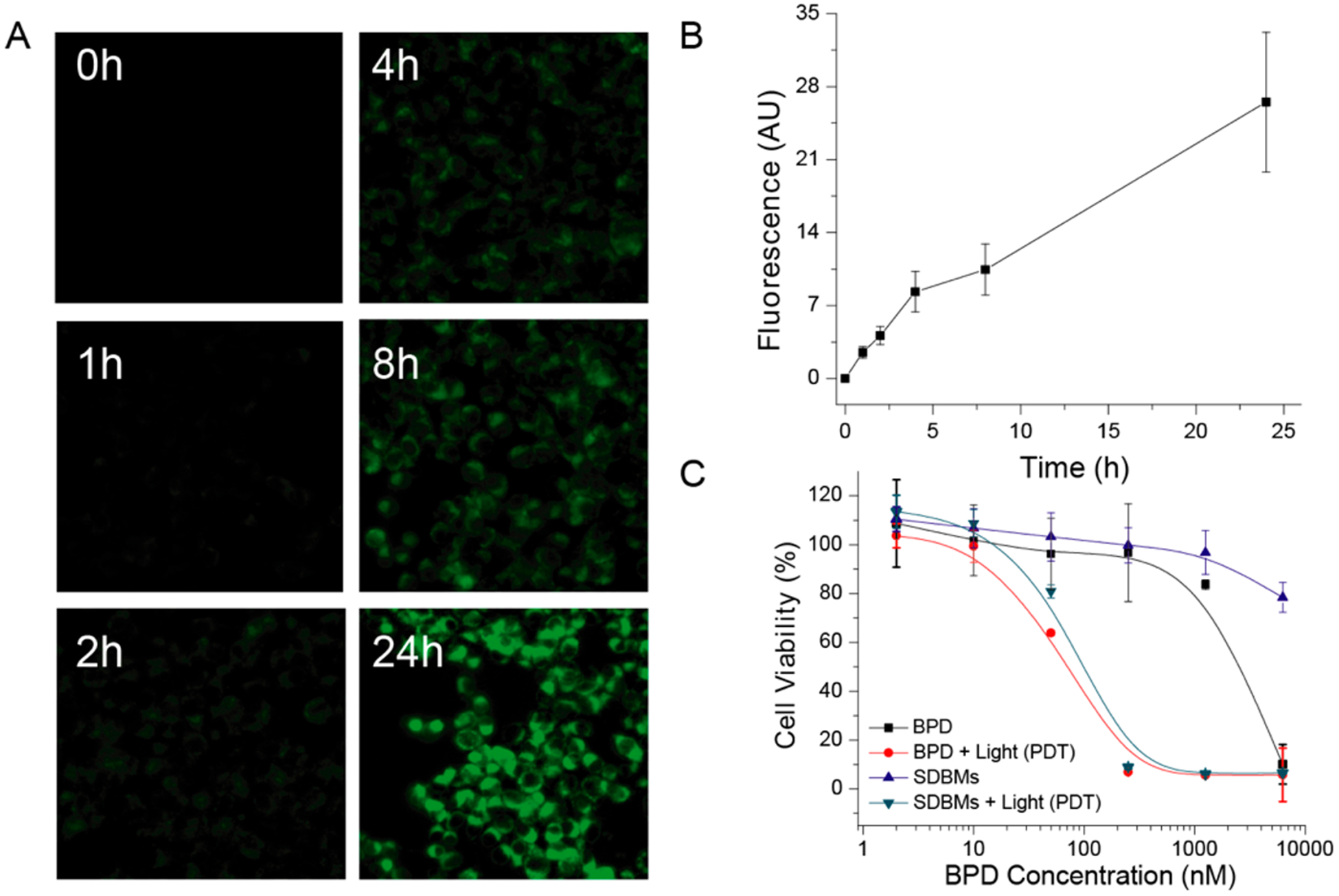

In order to determine the optimal micellar incubation time for PDT, cellular uptake of SDBMs by 4T1 cells was evaluated over time using fluorescence microscopy. As seen in Figure 4A,B, over the course of 4 h, the fluorescence intensity did not change considerably; however, the SDBMs did show a dramatic increase in fluorescence intensity from 8 to 24 h. This is indicative of micelle uptake and/or possibly BPD release within the endosomal/lysosomal compartments. Based on this result, the optimal micelle incubation time was chosen to be 24 h for further PDT studies in 4T1 cells.

Figure 4.

(A) Optical images of 4T1 cancer cells incubated with the SDBMs over time. (B) Quantitative analysis of optical images. (C) Cell viability of 4T1 cells after PDT with free BPD and the SDBMs with and without application of light. 690 nm laser light at 5 J/cm2 was used for PDT.

In Vitro Toxicity of Micelles.

Although most SDBM components (SPION, dextran, and BPD) are currently used in the clinic, it is still important to evaluate the toxicity of multifunctional micelles in their final form, for clinical translation. Therefore, we evaluated the toxicity of multifunctional micelles on 4T1 cells. Minimal cytotoxicity was observed with SDBMs in the absence of light delivery, for all micelle doses that were tested (up to a BPD concentration of 6250 nM; Figure 4C). In contrast, with PDT, the cell viability decreased with increasing concentrations of the micelles. The half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) were determined to be 100 nM, which was only slightly higher than that of free BPD (72 nM), further suggesting that the BPD are likely released from the SDBMs in the intracellular environment. Overall, the SDBMs did not cause dark toxicity at doses of ≤1250 nM but were highly effective in the presence of illumination to produce PDT-mediated cellular damage.

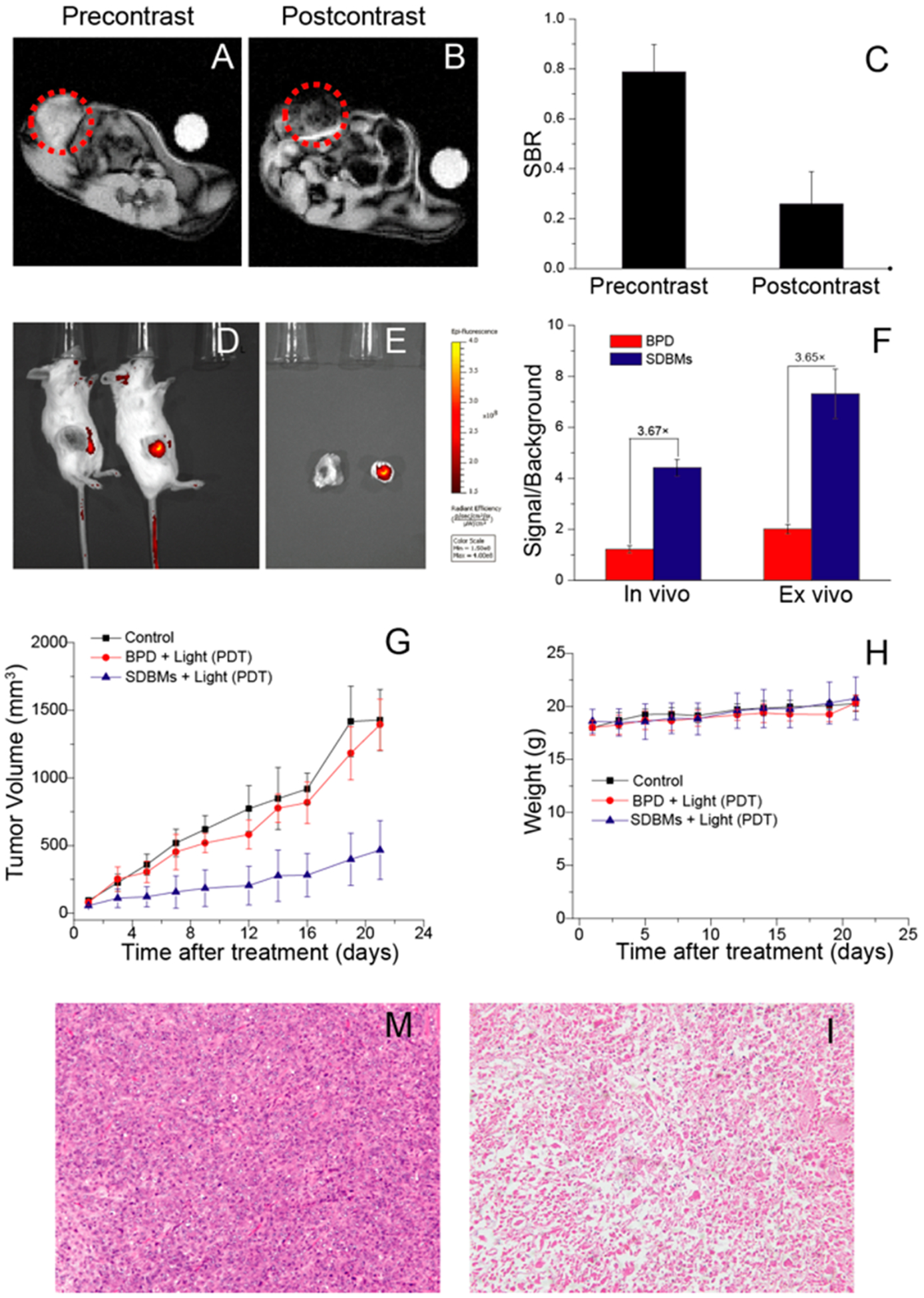

In Vivo Imaging.

The accumulation of the SDBMs within tumors was confirmed by MR contrast in mice bearing 4T1 orthotopic breast tumors. T2-weighted axial MR images were acquired precontrast and 24 h after intravenous (i.v.) injection of the SDBMs at a dose of 20 mg Fe/kg body weight. Passive accumulation of the SDBMs within tumors via EPR effect was identified by a loss in signal (i.e., hypointensity) in the tumor in the postcontrast images (Figure 5A,B). The MR signal in the tumor was also analyzed quantitatively (Figure 5C), with water as background. The postinjection SBR was ~3 times lower than the preinjection SBR. This phenomenon was further confirmed by fluorescence imaging of the tumor-bearing mice and of the excised tumors (Figure 5D,E). The tumor fluorescence signal in mice that received SDBMs was 3.7-times higher than mice that received free dye, 24 h postinjection (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

SDBMs-enhanced imaging and in vivo tumor response. (A and B) T2-weighted magnetic resonance images in the axial plane prior to injection (precontrast, A) and 24 h after intravenous injection (postcontrast, B) of the SDBMs. Tumor location is indicated by dotted red circle. (C) Quantitative analysis of MR images. Signal-to-background ratio (SBR) measurements were made using the tumor and the water as background. Preinjection versus postinjection SBR measurements are shown (n = 3 mice; columns represent SBR with error bars as standard deviation). (D) In vivo fluorescent images of mice with 4T1 orthotopic tumor 24 h post administration of free BPD or the SDBMs at a BPD concentration of 2.5 mg kg−1 body weight (n = 3). (E) Fluorescent images of excised tumors 24 h post administration of free BPD or the SDBMs. (F) Semiquantitative analysis of tumor fluorescence from D and E. (G) In vivo tumor response study after i.v. injection of PBS (control), free BPD, and the SDBMs at a BPD concentration of 2.5 mg kg−1 body weight. The PDT conditions for the in vivo study were as follows: wavelength: λ = 690 nm. Fluence rate: 75 mW/cm2. Fluence: 135 J/cm2. (E) Body weight changes of tumor-bearing mice after different treatments. (M and I) H&E stained tumor sections excised from 4T1 tumor bearing mice following 22 d treatment with (M) PBS, (I) the SDBMs. The images of tumor were obtained by a Zeiss microscope at low magnification (20×).

Antitumor Activity of Micelles.

The therapeutic efficacy of the SDBMs as a PDT agent was also evaluated in vivo using a 4T1 syngeneic orthotopic tumor model. At 7 days postinoculation of tumor cells, when the tumors had reached a size of approximately 50 mm3, the mice were divided into 3 groups (n = 5 per group): (1) untreated control; (2) BPD + light (PDT); (3) the SDBMs + light (PDT). The mice were given an intravenous injection of BPD or the SDBMs at an equivalent dose of 2.5 mg/kg BPD. At 24 h after injection, all mice were illuminated at the tumor site (690 nm, 75 mW/cm2, 135 J/cm2) and tumor size was subsequently measured on a daily basis. The mice treated with free BPD showed little therapeutic efficacy in comparison with the control group, likely due to free BPD having a short circulation time in bloodstream and a short retention time in tumor tissue. However, tumor growth in the SDBMs group was significantly slower than tumor-bearing animals that received PDT in combination with free BPD (Figure 5G), likely due to its improved pharmacokinetics compared with free BPD. These data suggest that a micellar drug delivery platform based on dextran-b-dOA dendron can improve tumor accumulation of photosensitizer and in turn enhance the therapeutic effect. There was no observable weight loss in any of the treatment groups (Figure 5H). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the tumor sections from the SDBM-treated group revealed PDT-induced cell killing and tissue damage with SDBMs, compared with the untreated group (Figure 5M,I).

Although SDBM-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging may serve as a useful oncologic imaging technique prior to PDT, it may not be useful for some specific types of cancer (i.e., lung cancer). In this case, dextran-BPD micelles can be formed without SPIONs. Dextran-BPD micelles without SPIONs still assume a spherical structure as evidenced in TEM (Figure S5A). The mean diameter is approximately 34 nm by DLS (Figure S5B). To evaluate the PDT efficacy of these micelles, the human lung cancer cell line H460 was incubated at 37 °C with either free BPD or dextran-BPD micelles at various BPD concentrations. As shown in Figure S5C, there was no observable phototoxicity or dark toxicity of dextran-BPD micelles and free BPD, indicating excellent biocompatibility. However, cytotoxicity was significantly increased when H460 lung cancer cells incubated with dextran-BPD micelles were illuminated with 690 nm light. Cell viability dramatically decreased, demonstrating a dose-dependent cytotoxicity that was similar to that found for free BPD after laser irradiation. The IC50 for the dextran-BPD (505 nM) -mediated PDT is slightly higher than for PDT with free BPD (324 nM), which is consistent with our above observation. To further evaluate the PDT efficacy of dextran-BPD micelles in vivo, tumor response studies were performed with a H460 mouse xenograft tumor model (Figure S5D). PDT with dextran-BPD micelles showed improved anticancer efficacy compared to that of free BPD. Thus, the dextran-b-BPD micelles could accumulate in tumor effectively through the EPR effect.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we have successfully developed an innovative nanotherapeutic platform based on dextran-b-dOA dendron-BPD for enhanced BPD delivery in vivo, which incorporate a T2-weighted MR contrast agent and a therapeutic photosensitizer within a single nanoformulation. The prepared SDBMs were stable in vitro and in physiological conditions. With SPION incorporation, the formulation offers functionality as a novel combination regimen by providing both imaging and therapeutic capabilities for treating cancers. Moreover, independent of MR imaging, the dextran-BPD conjugate itself can also be used to increase the efficacy of PDT in cases where MRI guidance is not necessary or appropriate. Furthermore, this platform could also be employed to deliver other photosensitizers, anticancer agents, imaging agents, etc., and thus offers a promising approach for intelligent drug delivery. In summary, this theranostic agent offers a unique opportunity and tremendous potential for monitoring and treating cancers with direct clinically translational impact.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials.

Dextran (Dex, molecular weight: 5 kDa) was purchased from Pharmacosmos A/S (Denmark). Methyl acrylate, ethylenediamine, copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO4·5H2O, 99%), and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethyllaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC·HCl) was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, U.S.A.). Sodium cyanoborohydride (NaCNBH3), sodium azide (NaN3, 99%), propargylamine (98%), and sodium L-ascorbate (NaAsc, 99%) were purchased from Acros Organics (New Jersey, U.S.A.). BPD-MA was purchased from The United States Pharmacopeial Convention (Rockville, MD, U.S.A.). Toluene, anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and anhydrous trimethylamine (TEA) were used as received. Monoazido dendritic oligoamine G2 (N3-dOA) was synthesized according to a previous report.22 Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPION) were prepared by thermal decomposition as previously described. Cell culture medium (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium), penicillin, streptomycin and heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco Life Technologies, Inc. (Grand Island, NY, U.S.A.). All other reagents and solvents were used as received. All of the buffer solutions were prepared with deionized water.

Synthesis of α-Alkyne Dextran.

α-Alkyne dextran was synthesized from dextran and propargylamine in the presence of NaCNBH3, as described in the literature.23 Briefly, Dextran (5.0 g, 1.0 mmol) was dissolved in acetate buffer (20 mM, pH 5.0, 2% (w/v)) at 50 °C. Then propargylamine (5.5 g, 100 mmol) and sodium cyanoborohydride (6.3 g, 100 mmol) were added under stirring. After stirring for 96 h at 50 °C, the solution was concentrated and then extensive dialyzed (MWCO 3.5 kDa) against milli-Q water for 72 h. The product was further freeze-dried to give sponge-like powder (4.2 g, yield: 84%).

Synthesis of Dex-dOA.

Dex-dOA conjugate was prepared by click reaction between an alkyne functionalized Dex-alkynyl and an azide end-functionalized dendritic oligoamine N3-dOA. Briefly, Dex-alkynyl (500 mg, 100 μmol), N3-dOA (117 mg, 150 μmol), and CuSO4·5H2O (2.5 mg, 10 μmol) were dissolved in DMSO (5 mL) in a Schlenk tube. Then the reaction mixture was degassed by three freeze-pump- thaw cycles. The sodium ascorbate powder (NaAsc, 3.9 mg, 20 μmol) was added under the protection of N2 flow after two freeze–thaw cycles. Next, the reaction mixture was left under the nitrogen atmosphere and stirred at 45 °C for 72 h. The solution was further purified by extensive dialysis to remove excess oligoamine, CuSO4, and sodium ascorbate with aqueous EDTA solution and milli-Q water, followed by lyophilization to get the final product (480 mg, yield: 83%).

Synthesis of Dex-dOA-BPD (Dex-BPD).

The hydrophobic BPD-MA was chemically conjugated to Dextran-dOA through EDC/NHS coupling reaction. Briefly, BPD (60 mg, 83 μmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DMSO (2 mL), EDC·HCl (32 mg, 166 μmol) and NHS (19 mg, 165 μmol, 2 molar equiv of carbonyl groups) were then added to the solution to activate the carbonyl groups of BPD at 25 °C on a rocker table for 0.5 h. Next, dextran-dOA (80 mg, 13.8 μmol) in anhydrous DMSO (3 mL) was mixed with the above solution, and then the mixture was vigorously stirred at room temperature for 24 h. Afterward, the reaction mixture was dialyzed (MWCO 3.5 kDa) against DMSO to remove excess BPD, EDC and NHS, and was further dialyzed against water to remove DMSO. Finally, the product was freeze-dried to give a greenish powder. (85 mg, yield: 71%).

The degree of conjugation for BPD in the Dex-BPD conjugate was determined using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (Varian, 100 Bio). The synthesized Dex-BPD conjugates were dissolved in DMSO and the BPD concentration in the conjugates was quantified by the measurement of the UV absorbance intensity at 690 nm for BPD, according to the standard calibration curve of free BPD in DMSO.

Preparation of SPION Loaded Dex-BPD Micelles (SDBMs).

SDBMs were prepared using a slightly modified oil in water microemulsion method. Briefly, 4 mg of Dex-BPD was dissolved in 200 μL of DMSO, with the addition of SPIO (1 mg based on the Fe concentration in toluene) in 50 μL of toluene, and then vortexed at 50 °C until Dex-BPD and SPIO were fully dissolved. Next, the mixture was added into a glass vial containing 2 mL of water dropwise (1 mL/min) under gentle stirring, followed by sonication until the solution became homogeneous. The nanoparticles were further allowed to self-assemble overnight with continuously stirring in a dark environment, while the glass vial was left open to evaporate the toluene. Dialysis was performed in 5 L of water overnight to remove DMSO. The formed SDBMs were centrifuged at 2000g for 15 min, and then purified by passing through a MACS (25 LD columns, Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) column. The optical properties of synthesized nanoparticles were characterized by UV-absorption spectroscopy (Varian, 100 Bio). The hydrodynamic diameter and morphology were measured by Dynamic Light Scattering (Malvern, Zetasizer, Nano-ZS) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (JEOL 1010), respectively. The transverse relaxivity (r2) of nanoparticles was evaluated by Relaxometry (Bruker, mq60 NMR analyzer).

SDBMs Stability Studies.

Synthesized SDBMs were stored in water at 4 °C as well as incubated in DMEM at 37 °C for the stability study. Measurement of micellar structural integrity was acquired by monitoring the hydrodynamic diameter over the course of 1 week by dynamic light scattering. In addition, the optical stability of BPD for the micelles were measured over the same period of time by UV-absorption spectroscopy. The peak absorbance intensity at 690 nm of each sample was normalized to the corresponding absorbance at time zero. Furthermore, aliquots taken from the sample were tested at predetermined intervals for the determination magnetic properties via T2.

MRI Phantom Imaging.

After determining the iron concentration of SDBMs using ICP-OES, relaxometry measurements of a series of dilutions of the SDBMs were performed in T2 mode (Varian, 4.7 T). A plastic 120-well plate (MR phantom) was used to test the T2 hypointensity. Results indicated that abnormalities appear darker during MR imaging, which is associated with the synthesized SDBMs on a 4.7 T magnet.

Cell Culture.

The mouse breast cancer cell line 4T1 (ATCC) and nonsmall lung cancer cell line H460 were cultured and maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 U/mL streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Cellular Uptake Measured by Fluorescence Microscopy.

To evaluate the possibility of SDBMs for potential photodynamic therapy, the cellular uptake behavior of SDBMs was determined by fluorescence microscopy. The 4T1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of ~5 × 105 cells per well in 2 mL of DMEM and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h. After removing culture medium, the cells were incubated for different times with SDBMs at a BPD concentration of 5 μg/mL in DMEM. After incubation for a predetermined time at 37 °C, cells were washed three times with cold PBS and subsequently analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. All microscopy images were acquired with an Olympus IX81 motorized inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a back-illuminated EMCCD camera (Andor), an X-cite 120 excitation source (EXFO), and Sutter excitation and emission filter wheels. The relative intensity of BPD signal from each digital image was processed using ImageJ software.

In Vitro PDT Study.

To study PDT-mediated cell cytotoxicity, in vitro cytotoxicity properties of free BPD and Dex-BPD/SPIONs were characterized by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay in 4T1 cells, following the established procedure [17]. Briefly, cells harvested during their logarithmic growth phase were seeded in 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One, Alphen a/d Rijn, The Netherlands) at ~5 × 103 cells per well. The 4T1 cells were incubated in 100 μL of DMEM cell culture medium at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 environment for 24 h. The diluted free BPD and Dex-BPD/SPIONs were added to the wells at six different concentrations ranging from 6250 nM to 2 nM (6250 nM, 1250 nM, 250 nM, 50 nM, 10 nM, and 2 nM). The cells were illuminated with light delivered through microlens-tipped fibers (Pioneer, Bloomfield, CT) at a power density of 5 mW/cm2 from a diode laser (B&W. Tek, Inc., λ = 690) for 1000 s. Light emitted from the fiber was measured by a power meter (LabMaster, Coherent, Auburn CA) and laser power was adjusted to produce the desired power density.

After irradiation, the 4T1 cells grew for an additional 24 h in DMEM before adding 10 μL of 5 mg/mL MTT assay stock solution to each well and incubating for 4 h. The formazan was dissolved by adding 100 μL of detergent to each well and then incubated for another 4 h. Finally, the plates were shaken for 1 min and absorbance of formazan product was measured on a Tecan plate reader (Tecan) at 570 nm. Cell viability was calculated using the following equation:

An internal negative control was prepared by keeping a portion of the wells covered during illumination to assess dark cytotoxicity.

In vitro cytotoxicity of free BPD and Dex-BPD micelles against H460 cells were also assessed as described above.

Animal Studies.

All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania and facilities are AAALAC accredited. Imaging and PDT experiments were conducted with approximately 6-week old female BALBC/cAnNCr mice (Charles River Laboratory, Charles River, MS, U.S.A.). For tumor propagation, mice were anesthetized by isoflurane, and then injected subcutaneously with 4T1 cells in the right mammary fat pad (1 × 106 cells in 0.05 mL of PBS). PDT was additionally studied of H460 tumors, propagated in female nu/nu nude mice by the subcutaneous injection of H460 cells in the back left flank (2 × 106 cells in 0.1 mL of PBS).

Dex-BPD/SPIONs micelles were administered to 4T1-bearing mice at a dose of 20 mg/kg via tail vein injection and imaged by MRI 24 h after injection. Mice were entered in the study at a tumor size of ~100 mm3. Imaging parameters for preinjection and postinjection (gems, TR200, TE3, 1 avr) were matched and confirmed by an attending radiologist. Imaging analysis were performed on preinjection and postinjection images to compare the mean Dex-BPD/SPIONs micelles at the tumor site.

Optical imaging was also utilized to image tumors in mice injected with either free BPD or Dex-BPD/SPIONs micelles. Tumors were excised at 24 h following drug administration, rinsed 3X in water and imaged by the IVIS 200 imaging system (Xenogen). All images were processed with the IVIS software.

PDT was performed of tumors ~50 mm3 in size. Mice were randomly assigned to three groups of five mice each and injected with either free BPD or Dex-BPD/SPIONs micelles at 24 h before light delivery (690 nm). A 1 cm diameter region of uniform light intensity was provided by a diode laser (B&W Tek, Inc.), delivered through microlens-tipped fibers (Pioneer). The intensity of the laser output was monitored and adjusted (LabMaster power meter; Coherent) to produce a fluence rate of 75 mW/cm2 at the tumor surface. The laser output was held constant for 30 min until a total fluence of 135 J/cm2 was delivered. During PDT mice were anesthetized mice via inhalation of isoflurane in medical air (Vet Equip anesthesia machine).

After PDT, tumor volume was monitored every other day by caliper measurement of tumor length (major axis of the tumor) and width (minor axis of the tumor). The weight of the mice was also monitored post-treatment. Tumor volume was calculated as

Tumor growth curves were plotted as the average tumor volume for each treatment group as a function of time after PDT.

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E).

Processing, staining, and evaluation of the tumor were carried out by the Cancer Histology Core within the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health R01NS100892 (ZC), R01CA175480 (ZC), R01CA181429 (AT), P01CA087971 (TB; project 4), and R01CA085831 (TB).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.9b00676.

dOA synthesis, ferumoxytol characterization, and in vitro and in vivo studies based on dextran-BPD micelles (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Castano AP, Mroz P, and Hamblin MR (2006) Photodynamic therapy and anti-tumour immunity. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 535–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Mitsunaga M, Ogawa M, Kosaka N, Rosenblum LT, Choyke PL, and Kobayashi H (2011) Cancer cell-selective in vivo near infrared photoimmunotherapy targeting specific membrane molecules. Nat. Med 17, 1685–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Ormond AB, and Freeman HS (2013) Dye Sensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Materials 6, 817–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Fernandez JM, Bilgin MD, and Grossweiner LI (1997) Singlet oxygen generation by photodynamic agents. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 37, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Grossman CE, Pickup S, Durham A, Wileyto EP, Putt ME, and Busch TM (2011) Photodynamic therapy of disseminated non-small cell lung carcinoma in a murine model. Lasers Surg. Med 43, 663–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Schouwink H, Rutgers ET, van der Sijp J, Oppelaar H, van Zandwijk N, van Veen R, Burgers S, Stewart FA, Zoetmulder F, and Baas P (2001) Intraoperative photodynamic therapy after pleuropneumonectomy in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: dose finding and toxicity results. Chest 120, 1167–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Friedberg JS, Culligan MJ, Mick R, Stevenson J, Hahn SM, Sterman D, Punekar S, Glatstein E, and Cengel K (2012) Radical pleurectomy and intraoperative photodynamic therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann. Thorac. Surg 93, 1658–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Friedberg JS, Mick R, Stevenson J, Metz J, Zhu T, Buyske J, Sterman DH, Pass HI, Glatstein E, and Hahn SM (2003) A phase I study of Foscan-mediated photodynamic therapy and surgery in patients with mesothelioma. Ann. Thorac. Surg 75, 952–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Shi J, Kantoff PW, Wooster R, and Farokhzad OC (2017) Cancer nanomedicine: progress, challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17, 20–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, FarokHzad OC, Margalit R, and Langer R (2007) Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol 2, 751–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Cheng Z, Al Zaki A, Hui JZ, Muzykantov VR, and Tsourkas A (2012) Multifunctional nanoparticles: cost versus benefit of adding targeting and imaging capabilities. Science 338, 903–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Mokwena MG, Kruger CA, Ivan MT, and Heidi A (2018) A review of nanoparticle photosensitizer drug delivery uptake systems for photodynamic treatment of lung cancer. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther 22, 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lanzilotto A, Kyropoulou M, Constable EC, Housecroft CE, Meier WP, and Palivan CG (2018) Porphyrin-polymer nanocompartments: singlet oxygen generation and antimicrobial activity. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 23, 109–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Jin CS, and Zheng G (2011) Liposomal nanostructures for photosensitizer delivery. Lasers Surg. Med 43, 734–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Qian J, Wang D, Cai F, Zhan Q, Wang Y, and He S (2012) Photosensitizer encapsulated organically modified silica nanoparticles for direct two-photon photodynamic therapy and in vivo functional imaging. Biomaterials 33, 4851–4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Yan L, Amirshaghaghi A, Huang D, Miller J, Stein JM, Busch TM, Cheng Z, and Tsourkas A (2018) Protoporphyrin IX (PpIX)-Coated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle (SPION) Nanoclusters for Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater 28, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Yan L, Miller J, Yuan M, Liu JF, Busch TM, Tsourkas A, and Cheng Z (2017) Improved Photodynamic Therapy Efficacy of Protoporphyrin IX-Loaded Polymeric Micelles Using Erlotinib Pretreatment. Biomacromolecules 18, 1836–1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Blanco E, Kessinger CW, Sumer BD, and Gao J (2009) Multifunctional micellar nanomedicine for cancer therapy. Exp. Biol. Med. (London, U. K.) 234, 123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Xu JS, Zeng F, Wu H, Hu CP, and Wu SZ (2014) Enhanced Photodynamic Efficiency Achieved via a Dual-Targeted Strategy Based on Photosensitizer/Micelle Structure. Biomacromolecules 15, 4249–4259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Tian JW, Zhou JF, Shen Z, Ding L, Yu JS, and Ju HX (2015) A pH-activatable and aniline-substituted photosensitizer for near-infrared cancer theranostics. Chem. Sci 6, 5969–5977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Gibot L, Lemelle A, Till U, Moukarzel B, Mingotaud AF, Pimienta V, Saint-Aguet P, Rols MP, Gaucher M, Violleau F, Chassenieux C, and Vicendo P (2014) Polymeric Micelles Encapsulating Photosensitizer: Structure/Photodynamic Therapy Efficiency Relation. Biomacromolecules 15, 1443–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Zhang Y, Chen J, Xiao C, Li M, Tian H, and Chen X (2013) Cationic dendron-bearing lipids: investigating structure-activity relationships for small interfering RNA delivery. Biomacromolecules 14, 4289–4300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kuang H, Wu S, Xie Z, Meng F, Jing X, and Huang Y (2012) Biodegradable amphiphilic copolymer containing nucleobase: synthesis, self-assembly in aqueous solutions, and potential use in controlled drug delivery. Biomacromolecules 13, 3004–3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.