Abstract

Maternal depression is a risk factor for the development of problem behavior in children. Although food insecurity and housing instability are associated with adult depression and child behavior, how these economic factors mediate or moderate the relationship between maternal depression and child problem behavior is not understood. The purpose of this study was to determine whether food insecurity and housing instability are mediators and/or moderators of the relationship between maternal depression when children are age 3 and children’s problem behaviors at age 9 and to determine whether these mechanisms differ by race/ethnicity. We used data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. Food insecurity and housing instability at age 5 were tested as potential mediators and moderators of the relationship between maternal depression status at age 3 and problem behavior at age 9. A path analysis confirmed our hypothesis that food insecurity and housing instability partially mediate the relationship between maternal depression when children are age 3 and problem behavior at age 9. However, housing instability was only a mediator for externalizing problem behavior and not internalizing problem behavior or overall problem behavior. Results of the moderation analysis suggest that neither food insecurity nor housing instability were moderators. None of the mechanisms explored differed by race/ethnicity. While our findings stress the continued need for interventions that address child food insecurity, they emphasize the importance of interventions that address maternal mental health throughout a child’s life. Given the central role of maternal health in child development, additional efforts should be made to target maternal depression.

Keywords: Child problem behavior, Maternal depression, Food insecurity, Housing instability

Introduction

Child problem behavior, which may be internalizing (e.g., anxious, depressive) or externalizing (e.g., aggressive, hyperactive, noncompliant), negatively impacts the child’s adult health and economic outcomes (Delaney & Smith, 2012; Knapp, King, Healey, & Thomass, 2011). Maternal depression, one of the most common and debilitating disorders among women with children in the U.S., is associated with impaired behavioral outcomes for children from infancy through childhood and into adulthood (Augustine & Crosnoe, 2010; Trapolini, McMahon, & Ungerer, 2007). Children of mothers with depression have more problem behaviors than those with mothers who have never been depressed (Turney, 2012).

The adverse impact of a mother’s mental health on her children’s functioning probably occurs through multiple mechanisms in the child’s environment that may mediate or moderate the effect of maternal depression on children, such as maternal behaviors, parental social support, and economic stressors (Bodovski & Youn, 2010; Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; K. Turney, 2011; Valdez, Abegglen, & Hauser, 2013). Although the effects of maternal depression may be more consequential for families with hostile maternal behaviors, limited parental support, and low economic resources, it is also possible that that these mechanisms are influenced by maternal depression, which may contribute to a child’s negative outcomes. Low socioeconomic status (SES) and its associated stressors may contribute to depression (Heflin & Iceland, 2009). Although this has traditionally been a direction of focus in the sociological literature, depression itself may also increase family economic hardship (Frank & Koss, 2005; Garg, Toy, Tripodis, Cook, & Cordelia, 2015; Merikangas et al., 2007), which is associated with increased child problem behaviors (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997). Although one study using mediation suggests that economic hardship alone explains approximately 20% of the relationship between maternal depression and child problem behavior (Turney, 2012), few studies have examined the stressful context of economic hardship as a potential mediator of this relationship. Even in the context of moderation, although SES has been studied, there has not been an examination of specific aspects of economic wellbeing as potential moderators of the relationship between maternal depression and child problem behavior (Trapolini et al., 2007; K. Turney, 2011).

Material hardship is a consumption-based indicator of economic wellbeing, which captures sources of income other than earnings and assesses concrete instances of unmet material needs, such as food and housing (Zilanawala & Pilkauskas, 2012). In 2014, around 14.0% of U.S. households were food insecure, and 26.1% and 22.4% of Black and Hispanic households, respectively, were food insecure (Coleman-Jensen, Rabbitt, Gregory, & Sing, 2015). There are also racial/ethnic disparities with regard to housing, including home ownership (Kuebler & Rugh, 2013). Although maternal depression is associated with an increased odds of food insecurity and housing instability, and these are in turn associated with increased child problem behavior (Curtis, Corman, Noonan, & Reichman, 2014; Garg et al., 2015; Hanson & Olson, 2012; Jelleyman & Spencer, 2008), these prevalent factors of material hardship have not been examined as potential mediators or moderators of the relationship between maternal depression and child problem behavior.

Prior work of ours (unpublished), indicates that maternal depression in early childhood (e.g., age 3) increases the likelihood of greater problem behaviors in later childhood (e.g., age 9) and suggests that the impact of maternal depression does not attenuate over this time period. We conceptualize this relationship from a social ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), in which child wellbeing is influenced by proximal and distal spheres of influence known as the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem. In maternal depression, the framework would posit that children’s wellbeing is proximally influenced by their home environment, which contains principal sources of caregiving and support. In this microsystem, parents’ mental health, responsiveness, and children’s regular interactions with their parents and siblings influence children’s behavior over time. Structural conditions of the environment, such as housing and food, may be placed in the exosystem, as a stable characteristic of the neighborhoods in which families live.

Yet, we argue that these material hardships may also exist across different systems, and be malleable by parental mental health and behaviors. Moreover, these hardships have a direct influence on the child’s access to objects and tasks that stimulate them cognitively and emotionally (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). This latter conceptualization has important implications for interventions because it implies that food insecurity and housing are less stable than previously thought, and it places these conditions as more proximally related to children’s wellbeing. Thus, rather than targeting behavioral change as the mechanism of influence between maternal depression and child outcomes among housing and food insecure families, the target would expand to include the direct interplay between behavioral and material resources. These interventions will require more than psychological supports for affected families, such as multi-component population health interventions.

Purpose of the Study

In this study, we will examine the role of material hardship in the form of housing instability and food insecurity, and their effect on the association between maternal depression and child problem behaviors. We extend previous work by examining the roles of food insecurity and housing instability as mediators and/or moderators of the relationship between maternal depression when children are age 3 and problem behavior at age 9 and determining whether these mechanisms differ by race/ethnicity. Our hypotheses are as follows:

Maternal depression when children are age 3 will have a negative effect on their problem behaviors at age 9, but this effect will only be observed among families who are food insecure and housing unstable (moderation).

Maternal depression when children are age 3 will have an indirect effect on their problem behaviors at age 9 via food insecurity and housing instability at age 9 (mediation).

Tests of moderation and mediator analysis will differ based on race/ethnicity.

Method

Data Source and Sample

The Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) is a longitudinal cohort study of 4898 infants born in 1998–2000 in 20 U.S. cities (Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel, & McLanahan, 2001). Most children in the study were born into “fragile families” with unmarried mothers at high risk of living in economically disadvantaged conditions. Interviews were conducted with families at birth and ages 1, 3, 5, and 9, each corresponding to the Birth survey and Year 1,3, 5, and 9 surveys. Information was collected on factors related to the physical and mental health of the focal child. Families whose child was deceased or formally/legally adopted at the time of a survey wave were not eligible to participate in that survey wave or any wave thereafter. Those families who, as part of a collaborative study, were not selected randomly for participation at baseline were ineligible to participate in any survey follow-ups. We conducted analyses on data from families in the FFCWS who participated in the Year 9 survey on behavior (N=3,630).

Measures

Child Problem Behavior

The primary outcome of interest was children’s problem behavior when they were age 9. Primary caregivers participating in the FFCWS rated aspects of their child’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors by completing slightly shortened questionnaires consisting of 65 questions based on Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) scales (T. M. Achenbach, 1991, 1992). These are established, reliable, and valid measures of children’s problem behaviors (Nakamura, Ebesutani, Bernstein, & Chorpita, 2009). The primary caregiver was the mother if she lived with the child at least half of the time; otherwise the father or another adult who met the same residency qualification was considered the primary caregiver. At Year 9, 92% of primary caregivers were biological mothers.

For each CBCL item, the primary caregiver indicated whether the statement was not true (0), somewhat or sometimes true (1), or very/often true (2). We used a continuous variable of internalizing, externalizing, and overall behaviors. The internalizing behavior scale (possible range: 0-62) includes most items from the CBCL anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed , and somatic complaints subscales. The externalizing behavior scale (possible range: 0-68) includes most items from the CBCL aggressive behavior and rule-breaking behavior subscales. Overall problem behavior (range: 0-130) is the sum of the internalizing and externalizing behavior scores.

Maternal Depression

The primary exposure of interest was maternal depression status when their child was age 3. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF), developed by the World Health Organization, identifies individuals who likely have had a major depressive episode (MDE) in the previous year according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria (Kessler, Wittchen, Abelson, & et al., 1998). In the completion of this form, mothers were asked two stem questions: if they had feelings of depression (e.g., dysphoric mood) or if they were unable to enjoy normally pleasurable things (e.g., anhedonia) at some time during the previous year. Mothers who experienced one or both of these conditions for at least half of the day, every day, over a 2-week period were asked seven additional questions regarding depressive symptoms. Mothers who reported at least three of these additional symptoms were considered to have experienced depressive symptoms when their child was age 3.

Food Insecurity

The Children’s Food Security Scale (CFSS) is composed of eight child-referenced questions of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s 18-item Food Security Module (Nord & Bickel, 2002). Per USDA guidelines, households with CFSS scores of 2 or more are classified as having children that were food insecure (Nord & Bickel, 2002). We used this to determine whether any child in the household was food insecure in the previous year (dichotomous variable); of note, it does not assess the food security status of individual children. This is a conservative assessment, since even a single affirmative response to the CFSS questions may be concerning for the wellbeing of children (Miller, Nepomnyaschy, Ibarra, & Garasky, 2014).

Housing Instability

We measured housing instability, as others have done, with questions about homelessness risk (Curtis et al., 2014). We used housing instability survey status at Years 3 and 5, where a mother was considered housing unstable if any of the following conditions were met (dichotomous variable): she (1) had an affirmative response to the interview question “In the past 12 months, were you evicted from your home or apartment for not paying the rent or mortgage?”; (2) reported having moved three or more times since the Year 3 survey; or (3) had a positive response to questions about living with family or friends without paying rent, or living with an adult other than a spouse or partner; we considered this being “doubled-up,” which is another important measure that helps to capture precarious housing status.

Additional Variables

Variables that may be associated with both maternal depression and children’s problem behavior were included in our adjusted analyses. Since nearly all children in the sample live with their mother, we followed previous investigators and included many of the mothers’ characteristics (Turney, 2011, 2012). Because a relatively small number of mothers reported poor health at Year 3, we combined the fair/poor categories and compared them to a combined category of excellent/very good/good health (dichotomous variable). A continuous measure of age of the mother (in years) at the time of childbirth and whether the mother was foreign-born was included. We included her relationship history with the child’s biological father at the Year 3 survey, as has been done previously (categories included married or cohabiting, non-residential romantic relationship, separated or divorced, just friends, or no relationship; Meadows, McLanahan, & Brooks-Gunn, 2007). Although data on child race/ethnicity was not available in the FFCWS, maternal race/ethnicity was available, allowing us to compare children born to women of these racial/ethnic groups: non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, other. We included whether the child’s sex was female, the birth was paid for by Medicaid, or if the child had a low birth weight (less than 2,500 grams), since these variables are associated with poor physical, mental, and behavioral health outcomes (Gray, Indurkhya, & McCormick, 2004). We included maternal education (less than high school diploma, high school diploma or GED, or postsecondary education) and maternal household poverty category at the Year 3 survey, measured as a percent of the federal poverty line (FPL) of the year preceding the interview. Poverty categories included: 0-49%, 50-99%, 100-199%, 200-299%, and 300%+ of the FPL. We included a continuous variable for the number of children in the household at Year 3, which includes the focal child participating in the FFCWS.

Data Analyses

To test for moderation (Hypothesis 1), we ran unadjusted and adjusted unweighted models to test if food and housing insecurity status moderate the relationship between maternal depression and children’s behavioral problems (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Food insecurity and housing instability were tested as potential moderators of the relationship between maternal depression status at Year 3 and children’s problem behavior at Year 9 (Baron & Kenny, 1986). We added interaction terms of food and housing status at age 3 with maternal depression status at age 3 to the unadjusted and adjusted unweighted models. If an interaction term was significant, this would indicate that the difference in children’s problem behavior score was different across food and housing status, between those children whose mothers were depressed at Year 3 and those whose mothers were not depressed, and we would estimate these differences.

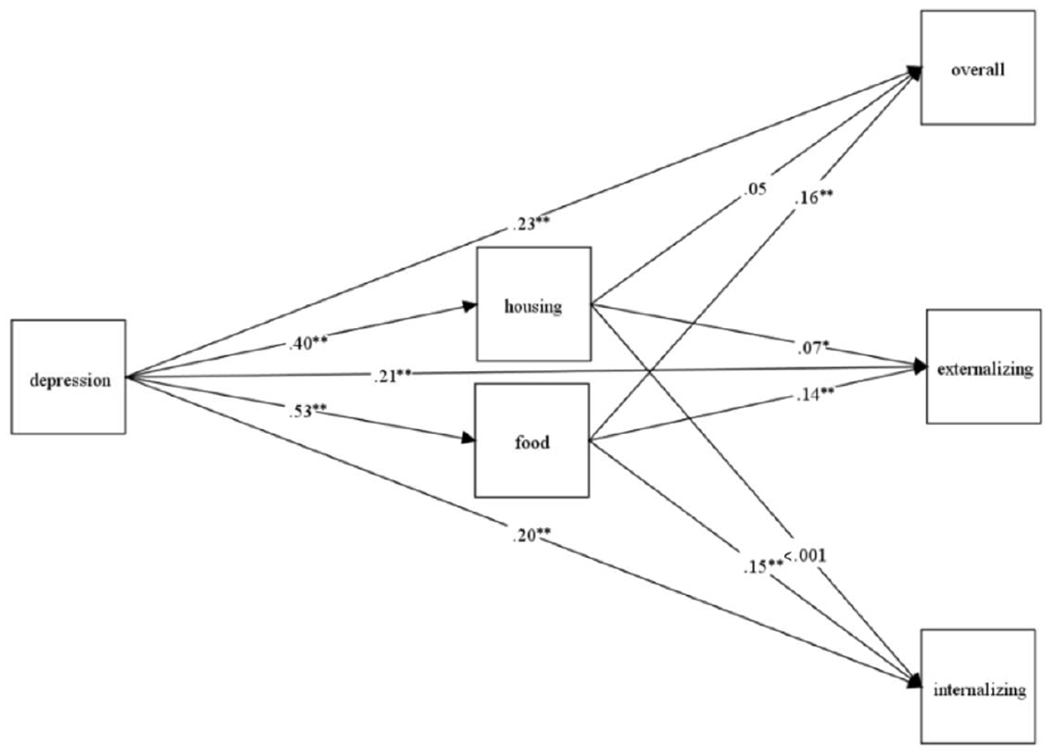

To test for mediation (Hypothesis 2), we conducted a just-identified path analysis in Mplus Version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017) to test a single model of the direct effects of maternal depression at Year 3 on children’s behavior at Year 9, as well as the indirect effect of maternal depression at Year 3 on children’s behavior at Year 9 through food insecurity and housing instability at Year 5 (see Figure 1). Just-identified path analyses are a common approach to test path models, but their goodness of fit indices are not interpretable because they fit the data perfectly (Reichardt, 2001; Tomarken & Waller, 2003). Thus, goodness of fit indices are not reported. We used the built-in procedures in Mplus to accommodate the categorical mediators. Missing data was handled with Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML). We include the standardized model results.

Figure 1.

The figure shows the just-identified path analysis between maternal depression, food and housing status, and children’s behavior problems.

* p < .05. ** p <.01.

To test if the moderation and mediator analyses differed based on race/ethnicity (Hypothesis 3), the statistical tests of moderation were reproduced in each racial/ethnic subgroup and results compared to determine whether the moderation differed by race/ethnicity. If we found significant interactions, we would account for these in our mediation analysis.

Results

Preliminary Results

To determine whether to utilize maternal depression status at Year 1 in our analyses, we added maternal depression at Year 1 and an interaction term of maternal depression at Year 1 and Year 3 to adjusted models of children’s problem behavior at Year 9 on maternal depression at Year 3. In these models, maternal depression at Years 1 and 3 was significantly associated with children’s problem behaviors at Year 9, with very similar magnitudes of association, and the interaction term between both years was not statistically significant. Based on this examination, we decided to only include maternal depression status at Year 3 in our analyses.

In total, 58 (1.7%) children experienced both food insecurity and housing instability at age 5. Among these 58 children, 27 mothers had depression. At Year 5, of those who experienced housing instability, 22% were also food insecure, and of those who experienced food insecurity, 17% also experienced housing instability. Table 1 includes the prevalence of food insecurity and housing instability at Year 5 across child, maternal, and household variables. Prevalence of food insecurity and housing instability was similar across child sex, and prevalence of food insecurity was highest among Black, non-Hispanic and Hispanic children. A high prevalence of food insecurity at age 5 was found among those children whose mother was depressed (19%), whose mother reported being in fair or poor health (17%), and whose household income was less than 50% of the FPL at year 3 (17%). About 12% of children whose mother was depressed at Year 3 experienced housing instability.

Table 1.

Prevalence of food insecurity and housing instability among Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study children

| Variable | Food Insecurity (y.5), n (%) | Housing Instability (y.5), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal depression (y.3) | 141(19) | 98(12) |

| Female (b.) | 155(9) | 141(8) |

| Male (b.) | 210(11) | 140(7) |

| Race/ethnicity (b.) | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 190(11) | 136(7) |

| Hispanic | 106(11) | 75(8) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 59(8) | 57(7) |

| Other | 8(7) | 13(10) |

| Fair or poor maternal health (y.3) | 82(17) | 65(13) |

| Maternal education (y.3) | ||

| Post-secondary education | 80(1) | 72(1) |

| High school diploma or GED | 104(11) | 61(6) |

| Less than high school | 180(13) | 147(10) |

| Medicaid birth (b.) | 232(13) | 168(9) |

| Foreign-born mother (b.) | 56(11) | 27(5) |

| Household income (y.3) | ||

| 0-49% FPL | 145(17) | 80(10) |

| 50-999% FPL | 99(14) | 66(9) |

| 100-199% FPL | 77(9) | 86(9) |

| 200-299% FPL | 27(6) | 26(5) |

| 300%+ FPL | 15(2) | 21(3) |

| Low birthweight (b.) | 42(12) | 36(10) |

| Maternal relationship with father: Not married or cohabiting (y.3) | 25(11) | 21(9) |

Note. y.5 = Year 5; Year 5 N=3001; y.3 = Year 3; baseline = b.; FPL= Federal Poverty Line.

Primary Findings

Moderation

Table 2 includes unadjusted and adjusted unweighted models that examine food and housing status as potential moderators of the relationship between maternal depression status at Year 3 and child internalizing, externalizing, and overall problem behavior at Year 9. In the adjusted analysis, which accounted for multiple child, maternal, and household factors, neither food nor housing significantly interacted with maternal depression status. This was also true when we examined potential moderation within each race/ethnicity subgroup (non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, other).

Table 2.

Odds ratios and associated 95% confidence intervals in ordinal logistic regressions of the impact of exposure to maternal depression at Year 3 (y. 3) on Year 9 (y.9) children’s problem behavior scores in the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study by food insecurity and housing instability status at Year 3 (y.3).

| Internalizing Behavior (y.9) | Externalizing Behavior (y.9) | Overall Behavior (y.9) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |

| Food Insecure (y. 3) | 1.64 (1.08, 2.51) | 1.95 (0.97, 3.93) | 2.07 (1.35, 3.16) | 1.69 (0.84, 3.39) | 2.06 (1.35, 3.15) | 1.97 (0.98, 3.95) |

| Food Secure (y. 3) | 1.61 (1.45, 1.93) | 1.64 (1.26, 2.14) | 1.72 (1.44, 2.06) | 1.64 (1.26, 2.14) | 1.80 (1.51, 2.15) | 1.76 (1.35, 2.30 |

| Housing Unstable (y. 3) | 1.93 (1.30, 2.87) | 1.46 (0.65, 3.31) | 2.00 (1.34, 2.96) | 1.22 (0.54, 2.76) | 2.13 (1.43, 3.16) | 1.35 (0.60, 3.05) |

| Housing Stable (y. 3) | 1.78 (1.49, 2.07) | 1.69 (1.30, 2.20) | 1.80 (1.53, 2.12) | 1.70 (1.31, 2.20) | 1.96 (1.67, 2.31) | 1.83 (1.41, 2.38) |

Adjusted model controls for child (gender, race/ethnicity, low birthweight status, Medicaid birth status), maternal (self-reported health at Year 3, educational attainment, age at childbirth, foreign-born status, relationship with child’s biological father at Year 3), and household (income at Year 3, number of children at Year 3) factors. Food insecurity status at Year 3 is included in the adjusted model examining housing instability interaction; housing instability status at Year 3 is included in the adjusted model examining food insecurity interaction.

Mediation

In the just-identified path analysis, depression at Year 3 directly and positively predicted child problem behaviors at Year 9 for externalizing problem behaviors (β=.21, SE =.05, z =.4.65, p <.0001), internalizing problem behaviors (β=.20, SE =.05, z =4.43, p <.0001), and overall problem behaviors (β= .23, SE = 05, z =5.04, p <.0001). Depression at Year 3 also directly predicted housing instability (β=.40, SE =.07, z =5.82, p <.0001) and food insecurity at Year 5 (β =.53, SE =.06, z =8.40, p <.0001). The indirect effect of depression at Year 3 on externalizing problem behaviors at Year 9 was significant through food insecurity (β=.07, SE =.02, z =4.54, p <.0001) and housing instability at Year 5 (β=.03, SE = 01, z =2.04, p <042). The indirect effect of depression at Year 3 on internalizing behaviors at Year 9 was significant through food insecurity (β=.08, SE =.02, z =5.52, p <.0001) but not housing instability at Year 5 (β=.02, SE = 01, z =1.29, p <.197). The indirect effect of depression at Year 3 on overall problem behavior at Year 9 was significant through food insecurity (β=.08, SE =.02, z =5.35, p <.0001) but not housing instability at Year 5 (β< .001, z = 05, SE = 02, p <.963).

Discussion

We conceptualize the relationship between maternal depression and children’s problem behaviors from a social ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), where the children’s wellbeing is most proximally influenced by their home environment, a microsystem, which contains principal sources of caregiving and support, particularly parents’ mental health. Structural conditions of the environment and neighborhoods, including hardships with housing and food, are characteristics of the macrosystem, as well as part of the microsystem, given their influence on parents’ responsiveness and children’s access to positive cognitive and emotional stimulation and stability (Hanson & Olson, 2012; Melchior et al., 2009).

We found that food and housing insecurities at Year 5 partly explained the relationship between maternal depression at Year 3 and child problem behavior at Year 9. Specifically, food insecurity and housing instability at Year 5 mediated this relationship for externalizing problem behavior at Year 9. As for the relationship between maternal depression and internalizing or overall problem behavior, only food insecurity at Year 5 mediated this relationship. Therefore, food insecurity and housing instability appear to partially explain how maternal depression can impact children’s problem behavior at a later time. Our conceptualization has important implications for interventions because it implies that food insecurity is proximally related to children’s wellbeing and development. Rather than targeting behavioral change, the target would expand to include a multi-phase and multi-component population health interventions beyond psychological supports to increase stability to vulnerable families. Furthermore, safety net programs that provide financial assistance to families (e.g., cash payments or subsidized housing, child care, or food) aim to alleviate the short-term effects of economic instability in families, particularly for children in low-income families; these programs can be difficult to access and retention can be low (Golden & Olivia, 2013). Policies and programs that assist families experiencing child food insecurity should be expanded to include increasing access to food options in communities through school food programs and resources, particularly for those that have a disproportionate number of children experiencing food insecurity.

Previous literature suggests that housing instability may contribute to a chaotic environment and increase children’s risk of developing problem behavior and learning problems (Deater-Deckard et al., 2009; Rumbold et al., 2012). In our study, although maternal depression increased the likelihood of housing instability, housing instability did not predict children’s problem behavior for internalizing or overall problem behavior. Several factors may have led to this finding. There is no standardized measure of housing instability, and the timing of and social support associated with housing instability may be an important aspect of its impact on child behavior. One study found that moves before age 4 increased problem behaviors at age 4, but moves between ages 5 and 8 did not produce the same effects (Taylor, Matthew, & Edwards, 2012). Mothers who are doubled-up report having more people to rely upon for childcare and other support, and this maternal social support and child supervision could provide a positive protective environment for the child (Letiecq, Anderson, & Koblinsky, 1998).

Although our findings stress the continued need for interventions that address hardships within the microsystems and macrosystems (e.g., food and housing insecurities), there remains a need for interventions that address maternal mental health. Additional efforts should be made to target maternal depression and enable access to treatment of depressive symptoms. In our study, maternal depression had a negative impact on future children’s problem behavior, regardless of food and housing status. This suggests that interventions that aim to improve children’s behavior outcomes should target maternal depression in families of varied economic circumstances. Because our findings found no differences by race/ethnicity, we suggest that interventions should aim to target all families, regardless of race/ethnicity. Although our study focused on the effect of maternal depression on economic instability, economic instability itself may increase the risk of maternal depression. Addressing economic circumstances may also lower the risk of maternal depression, thereby improving children’s health outcomes.

There are several limitations to this study. Attrition makes it a challenge to conclude definitively that our findings are representative of the baseline sample of the FFCWS, and it may have resulted in the large standard errors we identified when using the weighted data. With our modeling approach, we were unable to test the extent to which food insecurity and housing instability mediated the association between maternal depression at Year 3 and children’s problem behavior at Year 9. Although primary caregiver assessments of behavior may carry a bias, they were the only available assessments that were significantly associated with maternal depression when the children were age 3 (our previous work indicated that teacher and child self-assessments revealed no significant relationship between maternal depression status when children were age 3 and children’s behaviors at age 9). The CIDI-SF does not diagnosis an MDE, is not a lifetime measure of depression, and it does not make a distinction between respondents with major depressive disorder, MDEs that occur as part of a bipolar disorder, or MDEs that occur in the course of psychotic disorders. Despite this, it has been used widely in epidemiologic studies and is a useful tool to examine whether a mother experienced an MDE in the year prior to the Year 3 survey wave. The CFSS is a measure of food security for all children in a household, and we are unable to determine whether the focal children experienced food insecurity, but we feel food insecurity status can be cautiously generalized to all the children within a household.

This study advances our understanding of the associations between maternal depression, children’s problem behavior, food insecurity, and housing instability. Consistent with prior research, this study demonstrates a link between maternal depression and children’s problem behavior over time (Augustine & Crosnoe, 2010; Trapolini, McMahon, & Ungerer, 2007). This study adds that food insecurity and housing instability may mediate a portion of the association between maternal depression before children attend school and their problem behavior once they are in school. Findings suggest that interventions and government programs that are invested in promoting healthy child outcomes and family wellbeing among vulnerable families should focus on the mental health needs of the family as well as the food insecurities and housing instability families may face.

Acknowledgements and funding information

The Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award numbers R01HD36916, R01HD39135, and R01HD40421, as well as a consortium of private foundations. Dr. Guerrero was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the NIH under award numbers R25GM083252 and T32GM008692, as well as the Department of Medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Funding: The Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award numbers R01HD36916, R01HD39135, and R01HD40421, as well as a consortium of private foundations. Dr. Guerrero was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the NIH under award numbers R25GM083252 and T32GM008692, as well as the Department of Medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist, 4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM (1992). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist, 2-3 and 1992 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine JM, & Crosnoe R (2010). Mothers’ depression and educational attainment and their children’s academic trajectories. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(3), 274–290. doi: 10.1177/0022146510377757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodovski K, & Youn MJ (2010). Love, discipline and elementary school achievement: The role of family emotional climate. Social Science Research, 39(4), 585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory C, & Sing A (2015). Household Food Security in the United States in 2014. U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, ERR-194. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MA, Corman H, Noonan K, & Reichman NE (2014). Maternal depression as a risk factor for family homelessness. American Journal of Public Health, 104(9), 1664–1670. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2014.301941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Mullineaux PY, Beekman C, Petrill SA, Schatschneider C, & Thompson LA (2009). Conduct problems, IQ, and household chaos: A longitudinal multiinformant study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(10), 1301–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney L, & Smith JP (2012). Childhood health: Trends and consequences over the life course. Future of Children, 22(1), 43–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, & Brooks-Gunn J (1997). Consequences of Growing Up Poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Frank RG, & Koss C (2005). Mental Health and Labor Markets Productivity Loss and Restoration. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Cook J, & Cordella N (2015). Influence of maternal depression on household food insecurity for low-income families. Academic Pediatrics, 15(3), 305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden O (2013). Early Lessons from the Work Support Strategies Initiative: Planning and Piloting Health and Human Services Integration in Nine States. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, & Gotlib IH (1999). Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review, 106(3), 458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray RF, Indurkhya A, & McCormick MC (2004). Prevalence, stability, and predictors of clinically significant behavior problems in low birth weight children at 3, 5, and 8 years of age. Pediatrics, 114(3), 736–743. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1150-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson KL, & Olson CM (2012). Chronic health conditions and depressive symptoms strongly predict persistent food insecurity among rural low-income families. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 23(3), 1174–1188. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heflin CM, & Iceland J (2009). Poverty, material hardship, and depression. Social Science Quarterly, 90(5), 1051–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelleyman T, & Spencer N (2008). Residential mobility in childhood and health outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62(7), 584–592. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.060103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Wittchen H-U, Abelson J, et al. (1998). Methodological studies of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in the US National Comorbidity Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 7, 33–55. doi: 10.1002/mpr.33 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp M, King D, Healey A, & Thomass C (2011). Economic outcomes in adulthood and their associations with antisocial conduct, attention deficit and anxiety problems in childhood. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 14(3), 137–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuebler Μ, & Rugh JS (2013). New evidence on racial and ethnic disparities in homeownership in the United States from 2001 to 2010. Social Science Research, 42(5), 1357–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letiecq BL, Anderson EA, & Koblinsky SA (1998). Social support of homeless and housed mothers: A comparison of temporary and permanent housing arrangements. Family Relations, 47(4), 415–421. doi: 10.2307/585272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows SO, McLanahan SS, & Brooks-Gunn J (2007). Parental depression and anxiety and early childhood behavior problems across family types. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(5), 1162–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior M, Caspi A, Howard LM, Ambler AP, Bolton H, Mountain N, & Moffitt TE (2009). Mental health context of food insecurity: A representative cohort of families with young children. Pediatrics, 124(4), E564–E572. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Ames M, Cui L, Stang PE, Ustun TB, Von Korff M, & Kessler RC (2007). The impact of comorbidity of mental and physical conditions on role disability in the US adult household population. Archives of General Psychiatiy, 64(10), 1180–1188. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DP, Nepomnyaschy L, Ibarra GL, & Garasky S (2014). Family structure and child food insecurity. American Journal of Public Health, 104(7), e70–76. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998-2017). Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura BJ, Ebesutani C, Bernstein A, & Chorpita BF (2009). A psychometric analysis of the Child Behavior Checklist DSM-oriented scales. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31, 178–189. doi: 10.1007/sl0862-008-9119-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord M, & Bickel G (2002). Measuring children’s food security in US households, 1995-1999, Food Assistance and Nutrition Research Report No. 25. US Dept of Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- Nord M, & Bickel G (2002). Measuring Children’s Food Security in U.S. Households, 1995-99, FANRR-25. USDA. [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt CS (2002). The priority of just-identified, recursive models. Psychological Methods, 7(3), 307–315. https://doi.Org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.3.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, & McLanahan SS (2001). Fragile Families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review, 23(4/5), 303–326. doi: 10.1016/S0190-7409(01)00141-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbold AR, Giles LC, Whitrow MJ, Steele EJ, Davies CE, Davies MJ, & Moore VM (2012). The effects of house moves during early childhood on child mental health at age 9 years. BMC Public Health, 12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M, & Edwards B (2012). Housing and Children’s Wellbeing and Development: Evidence from a National Longitudinal Study. Family Matters, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, & Waller NG (2003). Potential problems with “well fitting” models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 578–598. https://doi.Org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapolini T, McMahon CA, & Lingerer JA (2007). The effect of maternal depression and marital adjustment on young children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviour problems. Child Care Health and Development, 33(6), 794–803. doi: 10.1111/j.l365-2214.2007.00739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turney K (2011). Chronic and proximate depression among mothers: Implications for child wellbeing. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(1), 149–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turney K (2011). Labored love: Examining the link between depression and parenting behaviors among mothers. Social Science Research, 40, 399–524 . doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turney K (2012). Pathways of disadvantage: Explaining the relationship between maternal depression and children’s problem behaviors. Social Science Research, 41(6), 1546–1564. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez CR, Abegglen I, & Hauser CT (2013). Fortalezas Familiares Program: Building sociocultural and family strengths in Latina women with depression and their families. Family Process, 52(3), 378–393. doi: 10.1111/famp.l2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilanawala A, & Pilkauskas NV (2012). Material hardship and child socioemotional behaviors: Differences by types of hardship, timing, and duration. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(4), 814–825. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]