Abstract

Have the magnitude and correlates of residential displacement changed during the early twenty-first century in response to the foreclosure and eviction crises and escalating natural hazard disasters? We consider this possibility against the backdrop of past research on other causes of displacement. Our components approach to the concept encourages definitions of varied emphasis and scope. These definitions are operationalized with reason-for-move data from seven waves of the American Housing Survey conducted between 2001 and 2013. We document fluctuations in the relatively small share of mobile households who move involuntarily but detect no clear upward trend over time. Analysis of householder characteristics associated with displacement indicates that many longstanding disparities between advantaged and disadvantaged statuses persist, although they tend to be modest in size. Paradoxically, such patterns may contribute to a perception of displacement as random or unpredictable, further heightening public concern about the issue.

Keywords: displacement, residential mobility, housing insecurity, foreclosure, natural disaster, eviction

1. Introduction

Despite the obvious wealth and prosperity of the United States, many Americans have experienced growing economic insecurity during recent decades. This insecurity is evident in a variety of domains, including employment, income, health care, and retirement (Kalleberg 2011; Sullivan et al. 2000; Western et al. 2012). Hacker (2006) blames the trend on an historic shift in the locus of risk, with households now expected to take greater responsibility for their own well-being in the face of corporate and governmental retreat from the provision of collective ‘social insurance’. The risk shift identified by Hacker highlights the extent to which various forms of insecurity are interrelated, at both the aggregate and individual levels. Across metropolitan areas, for example, mortgage foreclosure rates tend to be higher in precarious labor markets (Dwyer & Lassus 2015). And unforeseen events, such as job loss or a medical problem requiring expensive treatment, can quickly destabilize a family’s residential situation (Pollack & Lynch 2009; Robertson et al. 2008).

As these illustrations suggest, housing figures prominently in the connections between different types of economic insecurity. Although housing insecurity is often viewed as a result of prolonged unemployment or a dip in income, it may be antecedent to them; consider how excessive housing costs constrain savings and increase debt. Beyond cost burden (Desmond 2018), some of the more common manifestations of housing insecurity are overcrowding, doubling up, and frequent moves, also known as hypermobility (Myers et al. 1996; Schafft 2006; Wiemers 2014). Here we focus on residential displacement, which—aside from literal homelessness (Lee et al. 2010)—arguably constitutes the most extreme, traumatic type of housing insecurity. Being displaced can disrupt household members’ social networks, reduce their access to jobs and services, increase material hardship, and undermine health and family functioning, among a range of potential negative outcomes (Allen 2013; Desmond & Gershenson 2016; Desmond & Kimbro 2015; Fried 1966; Hartman 1964; Kingsley et al. 2009).

Displacement refers to involuntary mobility, when a household must leave a dwelling unit against its will.1 The foreclosure crisis of the mid-2000s (Been et al. 2011; Hall et al. 2015a; Immergluck 2009, 2015) and Desmond’s (2016) ongoing efforts to document and account for the ubiquity of eviction have prompted widespread interest in displacement. However, the phenomenon is far from new, first receiving scholarly scrutiny during the 1960s as a byproduct of urban renewal and freeway construction projects (Anderson 1967; Estrada 2005; Wilson 1966). Subsequent studies, cited below, have examined involuntary changes of address due to housing market disinvestment, gentrification, and other processes of urban decline and redevelopment. While smaller-scale disasters such as home fires are often overlooked as proximate causes of displacement, the rising frequency of larger climate-related disasters is generating a new round of displacement investigations (Elliott 2015; Fussell & Harris 2014; Myers et al. 2008).

Awareness that forced moves may now originate from a greater variety of sources and events than in the past partially explains the heightened attention devoted to the displacement concept: it is being applied more broadly. For us, the critical issue is whether the actual prevalence of displacement has expanded as well. Do the early 2000s constitute a ‘perfect storm’ during which old and new causes of displacement converged or intensified? If accurate, this scenario could have implications for the individual- and household-level characteristics associated with involuntary movement. Conventional wisdom holds that renters, racial minorities, older people, and members of lower-income or educational groups tend to be overrepresented among the ranks of the displaced. But the current relevance of the traditional profile should not be assumed. One reason for such caution is that the less selective nature of natural hazards like hurricanes, wildfires, and flooding—along with the elevated likelihood of foreclosure among homeowners—might narrow or even reverse longstanding demographic and socioeconomic disparities in vulnerability to displacement.

The purpose of the present paper is to provide an empirical update on residential displacement during the early 21st century. We begin by discussing the meaning of displacement, our ‘components’ approach to the concept, and the evolution of its scope through successive eras of research on the larger forces and householder characteristics conducive to it. We then use reason-for-move data from the 2001–2013 waves of the American Housing Survey to address three questions at a national scale. First, what impact do different operational definitions have on estimates of displacement? Second, how consistent are these estimates within the study period, which was anchored by the Great Recession and featured substantial volatility? Is there any evidence of an upward trend in displacement, as ‘perfect storm’ speculation would suggest? And third, does the vulnerability of the disadvantaged still hold? That is, do the attributes of households and their members that best predicted displacement in the past continue to do so, or have new attributes emerged as influential? Alternatively, the strength of all household correlates may have weakened since 2001 if the risk of displacement became more evenly spread throughout the population.

2. Background

2.1. Defining the concept

Theoretical models of residential mobility regard moving as the culmination of a voluntary decision-making process, bounded by income, in which household members seek a dwelling and neighborhood that best suit their life cycle needs (Lee & Hall 2009; Rossi 1955; Speare et al. 1975). By contrast, most definitions of displacement emphasize its forced nature. A displaced household has not chosen to move but must do so anyway because of circumstances beyond its control that render the dwelling unaffordable, unavailable, or uninhabitable (Desmond & Shollenberger 2015; Dolbeare 1978; Grier & Grier 1980; Newman & Owen 1982). This absence of choice seems clear when the roots of displacement are external, a function of housing market conditions. As an illustration, local supply-demand imbalances can lead to abandonment, demolition, condominium conversion, or other displacement-generating actions taken by a private party (e.g., a landlord or real estate investor). In addition to market dynamics, dwellings become perilous when damaged or destroyed by natural hazards or human-influenced disasters, which have not always been considered causes of displacement in the research literature but should be. While such disasters are typically viewed as random, due to bad luck, the outcome is identical: the affected occupants must move.

Government actions operate in a similar fashion. At the municipal level, code enforcement might compel tenants to vacate particular buildings (Hartman et al. 1974). Moreover, local officials could use condemnation and the power of eminent domain to clear a larger site for public use (roads, government offices, utilities, etc.) or for redevelopment by a for-profit entity (Carpenter & Ross 2009; Center for Urban Research and Learning 2019). Although incumbent households are typically entitled to fair compensation, they lack the option of staying put. The main point is that residential displacement occurs in response to public sector (or public-private) projects as well as ‘natural’ housing market dynamics, and that these projects are beyond a household’s ability to prevent even when all prior conditions of occupancy have been satisfied (Hartman et al. 1981).

Recent research has broadened the notion of displacement to encompass moves prompted by eviction and mortgage foreclosure (Hartman & Robinson 2003; Martin & Niedt 2015). This usage seems consistent with the absence-of-choice principle that lies at the heart of the concept. However, some purists disagree, regarding the usage as too loose. Their assertion is that true displacement is only possible when contractual obligations are being met. Accordingly, neither eviction nor foreclosure would qualify as displacement if a household has fallen into arears on its payments (Freeman & Braconi 2004; Newman & Owen 1982). Scholars who support such a position imply that the household’s exit from the dwelling is due to a prior voluntary but erroneous decision about what constitutes a manageable rent level or set of mortgage terms.

Rather than accept or reject that contention, we pursue a components approach to defining displacement. Our analysis relies on multiple displacement rates, some that include eviction and/or foreclosure and others that do not. In response to the first research question, common sense leads us to expect that the more components incorporated in a specific rate, the higher it will be. Private actions are hypothesized to exceed those by government as a source of forced moves, given the widespread occurrence of the former in community contexts experiencing either disinvestment or reinvestment. We also anticipate that eviction and mortgage foreclosure will add significant increments to displacement for the years in which the American Housing Survey measures them. More generally, our strategy is to break out the contributions of different sources of involuntary mobility, then combine them in various ways. This flexible strategy acknowledges a lack of consensus on the precise meaning of displacement.

Despite the inclusive character of our approach, we have omitted some seemingly forced moves from consideration. ‘Imposed’ mobility represents one excluded type, such as when a person’s continued employment hinges on accepting a job transfer to a distant city. The key difference here is that the person feels pressure to move yet retains options: she or he might decide to stay put residentially by seeking another position in the local labor market. In addition to employment-related motivations, imposed mobility can result from life cycle events—marriage, divorce, the death of a spouse—which limit the role played by purely residential preferences (Clark 2016; Rossi 1955; Sell 1983).

Moves due to moderate changes in housing affordability also strike us as potentially ambiguous. Many households would find it impossible to afford a doubling of their monthly rent or mortgage payment, but housing cost increases are typically less dramatic than that. Rather, leaving one’s dwelling unit may entail a complex judgment based on the perceived acceptability of the new rent level relative to the current unit’s features and those available elsewhere. Our concern is that when budgetary preferences come into play, mobility can be hard to define as completely involuntary. This is especially true with the relevant item in the AHS data, which identifies wanting a lower rent or a less expensive house to maintain as the reason for moving.

Two final usages of the displacement concept are not incorporated in the present analysis. From an international perspective, displaced people must physically relocate, but their main reasons for doing so—fleeing armed conflict, ethnic persecution, or sustained human rights violations—differ from those of most interest in U.S. residential displacement scholarship (Dunn 2017; UN High Commissioner for Refugees 2018). (Natural or human-made disasters constitute an area of definitional overlap.) Although internal displacement is on the rise (Norwegian Refugee Council 2002), most displaced persons are forced to move long distances, often departing their homeland for refugee status in other countries.

A second omitted usage refers to non-spatial dimensions of displacement that may occur in the absence of an involuntary change of address. In gentrification research, for instance, incumbent residents who stay put often report feeling disconnected as long-time neighbors are replaced by newcomers whose values, tastes, and service priorities come to dominate the area (Atkinson 2015; Davidson and Lees 2010; Hyra 2015; cf Kearns & Mason 2013). Such social, cultural, and political manifestations of displacement certainly have meaning. However, the nature of the data at our disposal preclude their study.

2.2. Conducive forces

Displacement has periodically surfaced as an important topic in research and policy circles since the mid-1900s. The cyclical nature of its emergence aligns both with general housing market dynamics and unforeseen events conducive to displacement. Early work treated displacement as a function of two distinct market conditions, each reflecting a state of disequilibrium between supply and demand. Beginning in the mid-1940s, rapid suburban growth, deindustrialization, fiscal stress, declining municipal services, and racial compositional change contributed to an era of prolonged residential disinvestment and population decline in older northeastern and midwestern cities (Beauregard 2003, 2009; Bradbury et al. 1982; Squires 1994; Sugrue 1996). These cities soon possessed a surplus of substandard housing units with limited profit potential. Rather than undertake expensive repairs or continue to make burdensome mortgage payments on such units, many landlords and property owners opted to ‘walk away’—abandoning a building still in use—or to have the structure demolished, in either case leaving its occupants no choice but to move (Marcuse 1986; Sternlieb & Burchell 1973; National Urban League 1972). Contemporary evidence suggests that abandonment and demolition remain significant causes of displacement by private action and that they now have a wider geographic reach (Dewar & Thomas 2013; US Department of Housing and Urban Development 2014).

Concerns about involuntary mobility eventually shifted from disinvestment to market contexts in which the demand for housing exceeds supply. Displacement first became linked with this type of market imbalance when the initial wave of gentrification unfolded during the 1970s (Gale 1986; Laska & Spain 1980; Palen & London 1984; Sumka 1979; US Department of Housing and Urban Development 1981). Even today, the potential for longtime residents to be forced out of gentrifying neighborhoods attracts considerable attention. A vast literature speculates about the factors that have fueled the gentrification process, ranging from an inadequate supply of affordable housing to political economic forces to shifts in lifestyles and cultural preferences (Brown-Saracino 2010; Lees et al. 2008, 2010; Smith 1982; Zukin 1987). Together, these factors are believed to draw advantaged home seekers to areas inhabited by lower-status incumbents, who in turn face pressure from multiple mechanisms of displacement. The most obvious mechanisms are major rent or property tax increases, but tenure conversion, building renovation, expensive repairs prompted by code violations, and landlord neglect or harassment can also put residents at risk of being displaced (Chum 2015; Atkinson 2004).

As the shortage of affordable housing has assumed crisis proportions, supply-demand disequilibrium has spread beyond gentrifying neighborhoods. Desmond and his colleagues (Desmond 2012, 2018; Desmond & Shollenberger 2015) attribute the substantial number of forced moves experienced by renter households in low-income communities to wage stagnation, cuts in federal and local housing assistance, and the competition-induced scarcity of habitable units. In such settings, a heavy rent burden makes poor residents especially vulnerable to displacement by eviction and to further residential instability, given the poor-quality replacement housing in which they often land (Desmond et al. 2015). The equivalent of mass eviction occurs when mobile home parks close (Sullivan 2017a). Although some households own their trailers, they do not typically control the land on which the trailers sit (MacTavish et al. 2006; Sullivan 2018). Thus, the termination of a lease—combined with the cost and difficulties involved in relocating a mobile home—can result in the occupants not only being evicted but losing their property. Sullivan’s (2017b) study of park closures in metropolitan Houston shows that the closures have been concentrated on the city’s periphery, where permanent (i.e., immobile) affordable housing development is taking place.

We maintain that government efforts to address various types of market disequilibrium may exacerbate displacement rather than reduce it. According to one estimate, the federal urban renewal program sponsored slum clearance activities that forced at least one million people—disproportionately African American—to move between 1949 and 1965 (Anderson 1967; also see Gans 1962; Teaford 2000; Wilson 1966). The development of the interstate freeway system had a similar impact, with inhabitants of minority neighborhoods again bearing the brunt (Estrada 2005; Highsmith 2009; Rose & Mohl 2012). In both instances, some moved voluntarily or received relocation assistance, but many did not.

More recently, federal policy has shifted toward the building of mixed-income communities on the former sites of public housing projects, which were demolished to make way for the new construction. A key rationale for this kind of redevelopment, supported by HUD’s HOPE VI initiative, is that housing project dwellers will ultimately benefit: once returned to their original locations, they will be able to take advantage of the opportunities available in a revitalized, socioeconomically diverse environment (Cisneros & Engdahl 2009; Chaskin & Joseph 2015). However, evidence from multiple studies indicates that only about one-fifth of the project residents complete the roundtrip (Goetz 2013). A non-trivial share of the remainder meets some component of our displacement definition.

In addition to market dynamics and government intervention, events regularly contribute to involuntary mobility. The sorts of events we have in mind constitute shocks to housing security and may operate at either the household or contextual levels, or both. Mortgage foreclosure represents such an event for homeowners, increasing markedly in frequency over a several-year span and peaking in 2010 (Martin & Niedt 2015; Immergluck 2015). The deregulation of the banking industry set the stage for this increase, encouraging the issuance of subprime loans to lower-income applicants with weak credit histories and inaccurate expectations about how rapidly their new homes would appreciate. Blacks and Latinos were overrepresented among the roughly 6.7 million foreclosures completed between 2006 and 2013, as were minority and racially mixed neighborhoods (CoreLogic 2017; Hall et al. 2015a,b; Rugh 2015; Rugh & Massey 2010). Whenever they occur, virtually all completed foreclosures force a move because the housing unit is put up for auction or repossessed by the lender. Renters are affected as well, unaware that the mortgage on their apartment building is in default until they are evicted without cause by the new property owner (Been & Glashausser 2009; Pelletiere & Wardrip 2008).

Disasters are another type of event that can lead to displacement, either of a single household (in the case of a home fire) or of thousands impacted by a large-scale natural hazard (e.g., flooding). Contrary to popular perception, we should not consider hazard-generated disasters rare. A study by Elliott (2015) found that the average American household lived in an area that experienced 33 such disasters and associated property damages of over $60 million from 1995 through 2000 (also see Elliott & Howell 2017). Since then, disaster events linked to climate change—including hurricanes, tropical storms, tornados, wildfires, droughts, blizzards, and severe thunderstorms—have become even more frequent (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2012).

Their apparently random character suggests that these disaster events might serve a ‘leveling’ function, narrowing socioeconomic, racial, and other disparities commonly reported in the displacement literature. Yet available evidence tells us a different story (for reviews, see Fothergill et al. 1999; Fothergill & Peek 2004). Poor people and minorities tend to be concentrated in substandard residences in high-risk locations, and they have a harder time obtaining post-disaster assistance or permission to reoccupy a damaged rental unit than more advantaged individuals do (Elliott 2015; Fussell & Harris 2014; Morrow-Jones & Morrow-Jones 1991). As a result, they are disproportionately likely to wind up in mass shelters or FEMA emergency housing, assuming they manage to avoid literal homelessness.

2.3. Trends in displacement

One common-sense insight from the preceding review is that the magnitude of residential displacement at a particular historical moment depends upon how many different types of forces are actively producing involuntary moves. In line with that insight, the 2001–2013 period covered by our analysis could be considered a ‘perfect storm’ for the United States. Disinvestment, gentrification, and government actions continued to displace households just as they long had, and they were augmented by a severe shortage of affordable housing (boosting the risk of eviction) and surges in mortgage foreclosures and natural hazard disasters. This convergence of forces speaks to our second research question. It implies an upward trend in displacement during the post-2000 era, although the Great Recession and especially the foreclosure crisis could produce an uneven rather than a monotonic trajectory. The availability of American Housing Survey data for most components of displacement makes monitoring changes within the time span of interest relatively straightforward.

However, any comparisons of prevalence between contemporary displacement and its manifestations decades ago will pose significant challenges. With respect to the impact of urban renewal, central city disinvestment, and incipient gentrification from the 1950s through the 1970s, for example, an inability to distinguish truly forced moves from those at least partly preference-driven complicates inferences about displacement from the ballpark numbers assembled at the time (Cicin-Sain 1980; Marcuse 1986). Past research was also largely local in nature, focusing on selected cities or neighborhoods where pressures toward involuntary mobility were believed to be intense (e.g., Freeman & Braconi 2004; Hodge 1981; Newman & Wyly 2006; Schill & Nathan 1983). An even bigger problem, alluded to earlier, concerns differences across studies in the way that displacement has been defined and measured (compare Lee & Hodge 1984; Newman & Owen 1982; US Department of Housing and Urban Development 1979, 1981). Unfortunately, the American Housing Survey—first fielded in 1973—lacks the necessary degree of comparability over its first few decades of existence due to occasional changes in sample design, the wording of mobility questions, and the temporal window to which these questions referred. Hence, we limit our attention to the survey’s recent waves.

2.4. Who is vulnerable?

As a rule, a household’s vulnerability to displacement should be shaped in predictable fashion by those characteristics that define its members’ position in the stratification system. Yet events have the potential to narrow traditional disparities in displacement between advantaged and disadvantaged statuses. Hence, our third question asks whether the same householder characteristics that mattered in the past continue to be relevant or whether new ones have emerged. Among the attributes of interest, housing tenure stands out. Unlike owners, renters possess few contractual protections against being displaced: they remain vulnerable to eviction, landlord neglect and harassment, deteriorating neighborhood conditions, and the sale or conversion of their unit to other uses (Desmond 2012; Fussell & Harris 2014; Newman & Wyly 2006; Sternlieb et al. 1974). However, the rise in mortgage foreclosures during the early 2000s could weaken or reverse the relationship between tenure and displacement, depending on how the latter is defined. So could the frequency of mobile home park closures since the residents often own their trailers.

Another correlate of displacement identified in past studies is socioeconomic status (Desmond 2018; Fothergill & Peek 2004; Gale 1986). Resource disadvantages underpin this connection. Low-income households and those receiving government aid are less able than their better-off counterparts to weather unexpected financial changes due to the loss of a job or expensive medical treatment. They also have greater difficulty affording legal representation should threats to housing security arise. Even with rent vouchers (of which there are rarely enough) and other forms of assistance in hand, poor people tend to wind up in poor neighborhoods where substandard housing, safety issues, and service deficits may prompt forced moves. Limited educational attainment further raises the odds of displacement, making ‘paperwork’ such as a rental agreement or mortgage application harder to master. In general, empirical support for a negative relationship between measures of socioeconomic standing and displacement is abundant (Atkinson 2004; Clark 2016; Hodge 1981; Morrow-Jones & Morrow-Jones 1981; Schill & Nathan 1983). But the greater likelihood of renting among lower-status households hints that SES could indirectly influence displacement via tenure. Consistent with this possibility, few investigations show significant effects for both income and tenure when they are included in the same analysis.

Beyond the socioeconomic variables, we examine a handful of demographic characteristics that logic and evidence suggest heightens the chances of displacement. With respect to age, older people appear more vulnerable than younger ones to moving against their will, most notably in gentrifying neighborhoods (Grier & Grier 1980; Henig 1981; Newman & Wyly 2006; US Department of Housing and Urban Development 1979). Fixed incomes, combined with rising rents and property taxes in such areas, can force them out. Alternatively, some seniors wish to voluntarily leave declining neighborhoods but become ‘locked in’, their eventual departure the result of property abandonment, fire, demolition, or other manifestations of disinvestment.

According to Desmond (2012), the sex of the householder could be another important predictor of displacement (also see Atkinson 2004; Fothergill et al. 1996; Newman & Wyly 2006). Compared to men, the women in his study of Milwaukee renters bear the brunt of evictions. They tend to work part-time and for lower pay, and their incomes do not provide an adequate cushion to absorb unforeseen expenses. Because women are typically the custodial parents of their children, such expenses are not uncommon. Female headship also implicates marital status as a displacement antecedent. Independent of gender, singlehood—being divorced, separated, widowed, or never married—may mean fewer back-up resources if some ‘shock’ event reduces an individual’s employability or income.

At first glance, race-ethnicity qualifies as a major risk factor: African Americans and Latinos are overrepresented across most types of displacement. Due to a legacy of discriminatory government policies and unequal treatment by housing market gatekeepers (e.g., real estate agents, banks, mortgage companies, landlords), black and Latino households often face precarious residential circumstances (Elliott 2015; Fothergill et al. 1999; Goetz 2013; Hall et al. 2015a,b; Rugh 2015; Rugh & Massey 2010; Sumka 1979). Their concentration in segregated lower-income neighborhoods makes them vulnerable to a range of displacement-conducive forces, including disinvestment, predatory lending, and gentrification. We should note, however, that support for the greater likelihood of minority than white displacement is descriptive and bivariate in nature. In an analysis of Panel Study of Income Dynamics data from the 1970s, Newman and Owens (1982) found no significant effect of minority status on involuntary mobility with other respondent and housing characteristics controlled. Inconclusive results for race come from other studies as well (Gale 1986; LeGates & Hartman 1981; Newman & Wyly 2006; Schill & Nathan 1983). This mixed record suggests that nonracial attributes such as socioeconomic status may mediate the association between being black or Latino and experiencing a forced move.

An unresolved issue related to ethnoracial group membership concerns whether not being a U.S. citizen elevates the odds of displacement. Non-citizens without legal documentation or who are less assimilated in terms of English proficiency or housing market navigational skills strike us as quite vulnerable, but few displacement studies directly examine citizenship (Newman & Wyly 2006). Rugh and Hall (2016) suggest that the detention of undocumented immigrants could lead to a decline in household income and ultimately to eviction or foreclosure, among other outcomes (also see Chaudry et al. 2010). Likewise, little attention has been devoted to the presence of children. In the rental sector, households containing children may be viewed as problematic by landlords, making eviction more likely (Desmond 2012; Desmond et al. 2013; Lundberg & Donnelly 2019). Why? Because kids can be noisy, increase wear and tear on the unit, and attract unwanted attention, e.g., from the police (if they get into trouble) or from housing inspectors (due to complaints about lead-based paint, mold, or other health hazards).

Landlords may also consider a household problematic if one or more of its members has a physical or cognitive disability. The Americans with Disabilities Act requires that ‘reasonable accommodations’ be made in the accessibility and design of a rental unit and the rules governing its use (US Department of Housing and Urban Development 2019). Disabled tenants might seek informal assistance for meeting their needs as well. Beyond any potential discriminatory treatment at the hands of landlords, people with disabilities are on average less educated, more likely to be unemployed, and poorer than their counterparts in the population at large (American Psychological Association 2019). We suspect that these socioeconomic disparities play a major role in any heightened likelihood of displacement associated with disability status.

The preceding review points to different assessments about various sets of predictors. In line with past work, we expect measures of socioeconomic status and older age to be consistently related to displacement throughout the 2001–2013 study period, the former in a negative direction and the latter in a positive one. Contingent influences are anticipated for two other widely-cited predictors: the strength and sign of the association between tenure (renting) and forced mobility will depend on whether mortgage foreclosure is incorporated in the definition of displacement, while SES should mediate the oft-reported impact of being black or Latino. Finally, good reasons exist to believe that women, single people, non-citizens, and households with children or disabled members are disproportionately represented among displacees. However, the evidence on these characteristics is too sparse to state firm hypotheses.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data source

Our examination of recent patterns and predictors of residential displacement makes use of the American Housing Survey (AHS), a data collection effort sponsored by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development and conducted by the Census Bureau for over 45 years. We draw upon the seven national surveys carried out during 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, and 2013 to obtain estimates of displacement prevalence. (Surveys of selected metropolitan areas have been undertaken by HUD as well.) The national surveys feature a panel design that covers essentially the same housing units from one survey year to the next and provides a representative picture of the housing stock throughout the metropolitan and nonmetropolitan United States. Our interest is in the large majority of units that are occupied by households. However, because the AHS sampling frame comprises not only occupied units but vacant ones, occupant households are unlikely to perfectly represent households in general, let alone the entire American population. Mindful of this caution, we focus on those units occupied by households at the time of each survey, a number that ranges from 39,102 to 58,525 in six of the seven years.

The one outlier year is 2011, when a major revision of the AHS expanded the sample to cover 29 metropolitan areas in addition to the nation as a whole. This design change increased the N of occupied units to over 130,000. To ensure that the much larger 2011 sample does not affect the precision of estimates being compared, we have selected a random subsample (without replacement) of 46,500 occupied units using Stata 15’s sample command. The size of our 2011 subsample conforms closely to the mean N of observations (~46,100) across the 2001–2009 and 2013 national surveys. Moreover, the characteristics of the subsample households are similar to such characteristics in other years. We apply the AHS household-adjusted weighting variable, labeled WEIGHT in the technical documentation, to all seven years of data (Watson 2007). This variable begins with a ‘pure’ weight—the inverse of a housing unit’s probability of selection when the original sample was drawn—then controls for changes to the sample over time, such as units being removed or added. Most units have seven WEIGHT values, one for each survey wave from 2001 through 2013. Ideally, the weights should reduce standard errors and improve the representativeness of results. But the relevance of such benefits to our analysis is likely diminished by its exclusive focus on units in which households reside. For more information on the sample design and weighting procedures of the AHS, see https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs.html.

3.2. Displacement measures

To answer our research questions about displacement prevalence and trends, we create measures of displacement from retrospective interview items in the AHS recent mover module. Nested within the surveys’ panel design, this module pertains only to persons 16 years or older who are new occupants of a unit since the last wave of data was collected two years prior. A household is considered mobile if it includes at least one such person. In most cases, all occupants are new because one intact household has replaced another. A knowledgeable adult, whom we refer to as the focal householder, serves as the respondent for the entire household. Note that the AHS module captures households who have recently moved into the sample of housing units covered by the survey but does not follow those who have left the sample. This fact informs our strategy of pursuing descriptive and multivariate analyses that treat the 2001–2013 surveys as separate cross-sections of mobile households.

We distinguish between recent mover households who report being displaced during the preceding 24-month window and those who do not, based on the focal householder’s response to a series of interview items about reasons for moving. (Multiple reasons could be reported.) The retrospective nature of these items requires that householders remember the details of a move which could have occurred up to two years earlier. Fortunately, displacement is a rare and significant life event, which we believe increases the chances of accurate recall.2 The reason-for-move items allow us to identify five types or components of displacement: (1) private action, including moves that result from a person or company taking over the housing unit, the owner moving in, condominium conversion, or closure for repairs; (2) government action, when the household is forced to move because a governmental entity acquires the property for public use via condemnation and eminent domain; (3) disaster loss due to fire or natural hazard; (4) eviction from a rental unit; and (5) mobility prompted by mortgage foreclosure.

Besides breaking the five components out separately, we combine them into three summary measures of increasing scope. The first summary measure indicates if a household has been displaced by private action, government action, or disaster loss. Because these reasons for moving are available for all seven survey years, we refer to them collectively as our base displacement measure. Our second or expanded summary measure adds another reason, eviction, which was first incorporated in the 2005 AHS and appears in all survey waves since then. The third summary measure, labeled full displacement, comprises the four previous components plus foreclosure. Due to the limited availability of foreclosure as a reason for moving in the AHS (only included in 2011 and 2013), the full measure cannot be used to make any definitive statements regarding trends in displacement. However, it can be compared with the base and expanded summary measures at a couple of time points to evaluate the extent to which estimates of displacement prevalence are affected by the way that displacement is defined. It also allows us to shed recent light on our third research question, about the association between householder characteristics and the likelihood of being displaced.

Dichotomous versions of the three summary measures and their five components form the building blocks of our study. Beyond their value in the individual-level analysis of displacement predictors, we employ them to construct two types of displacement rates. The first rate, which reflects the percentage of mobile householders experiencing different forms of displacement, benefits from its frequent usage in the research literature. The second rate refers to displacement risk among the population of all householders, not just mobile ones. Consequently, the magnitude of this rate tends to be quite small—a fraction of 1%—making variation difficult to discern. We have therefore decided to follow precedent, emphasizing the initial rate (for mobile householders) but briefly exploring the second rate.

The AHS data on displacement have undeniable strengths: they provide a national-level picture of the phenomenon over time, they cover owners as well as renters, and they differentiate among multiple reasons for being displaced. At the same time, they are limited in important ways. For example, the restriction of the survey to conventional housing units in the US excludes any households who have been forced to move onto the streets, into emergency shelters or other group quarters, or out of the country. Moreover, the survey items on residential mobility ask only about the last move made by a household in the prior 24 months, even if it moved multiple times. Thus, various forms of housing instability—such as informal evictions (Desmond & Shollenberger 2015), hypermobility, and brief spells of doubling up or homelessness—may be missed. The relatively advantaged status of the displaced households in the AHS sample is worth noting as well, given that they had secured housing by the time of their interview. We suspect that the cumulative effect of these limitations is to downwardly bias estimates of both overall and involuntary mobility.

3.3. Householder characteristics

In line with our third research question, we examine several householder and household characteristics that the literature suggests are related to displacement. Previous tenure is represented by a set of three dummy variables that reflect tenure prior to the move: owner, renter, and non-payer, with owner serving as the reference category in regression analyses. We do not show the non-payer category in tabular results due to its small size (2% of householders experiencing full displacement). Indicators of socioeconomic standing include poverty status and highest level of educational attainment. Poverty status is a binary variable indicating whether household income falls below the federally-defined poverty line. Four dummy variables capture the focal householder’s educational attainment: less than high school, high school graduate, some college, and college graduate and above (reference).

Five demographic attributes are also evaluated as potential correlates of displacement. Age is captured with three dummy variables: less than 25 years old (reference), 25 to 64 years old, and 65 years or older. Sex indicates if the focal householder is male or female. We use four dummy variables to measure marital status: married (reference), divorced or separated, widowed, and never married. Race/ethnicity consists of white (reference), Hispanic, black, and Asian/other categories. Lastly, we represent citizenship with three dummy variables: native citizen (reference), naturalized citizen, and non-citizen.

The final portion of our regression analysis incorporates three understudied predictors of displacement that are only available in the 2011 and 2013 AHS waves. All three have been converted to binary-coded form. The first variable indicates whether the focal householder has any children under 18 who are present in the housing unit. The second is a binary indicator of disability, coded 1 if the householder has any of the following: hearing disability, sight disability, memory disability, walking disability, can’t care for themselves on their own, or can’t run their own errands. We also include a dichotomous measure of whether the household receives any form of government assistance such as welfare, food stamps, social security, SSI, or other (i.e. unemployment or veteran payments).

In addition to householder characteristics, our regression models control for the housing unit’s region of the country and metropolitan status. We rely on census-defined regions: Northeast (reference), Midwest, South, and West. Metropolitan status is operationalized via three dummy variables: central city of a metro area (reference), non-central city within a metro area, and non-metro location. Although these two variables are used as controls, we do not present them in our results.

4. Results

4.1. Narrow versus broad estimates

Our first research question concerns the sensitivity of estimates of residential displacement to the way that the phenomenon is operationally defined. Table 1 presents base, expanded, and full displacement rates using two different denominators (total households and mobile households). We focus on the 2011 and 2013 waves of the AHS because they are the only survey years for which all components of displacement are available. Regardless of denominator, the rate of displacement increases in magnitude with the addition of eviction (expanded rate) and foreclosure (full rate). As shown in the first and third columns, however, overall risk remains very low. One percent or fewer of all households were displaced during the two years prior to interview, even when the numerator includes both eviction and mortgage foreclosure. Among mobile households (second column), 1.9% experienced displacement in the 2011 window as measured by the base rate. However, the incorporation of eviction and foreclosure yields a full rate of 4.3%, over two times greater than the base rate. Somewhat smaller proportional gains accompany the broadening of displacement definitions in 2013 (fourth column). The 2013 base, expanded, and full rates all exceed their 2011 counterparts by substantial amounts, with 5% of the mobile households reporting at least one form of displacement in the previous two years.

Table 1.

Summary Displacement Rates for all Households and Mobile Households, 2011 and 2013

| Type of Rate | 2011 |

2013 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Households | Mobile Households | All Households | Mobile Households | |

| Base | .43 | 1.89 | .82 | 3.57 |

| Expanded | .56 | 2.48 | .93 | 4.09 |

| Full | .96 | 4.28 | 1.15 | 5.04 |

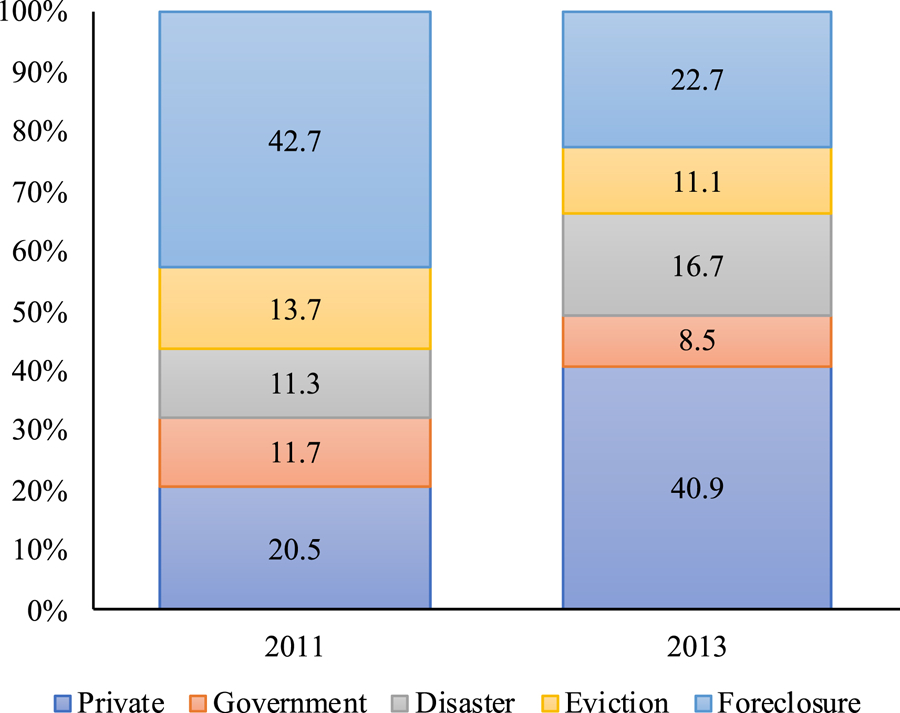

The relative contribution of each component or type of displacement to the full rate is visually conveyed in Figure 1. Approximately two-fifths of the 2011 displaced households in the AHS sample were forced to move because of foreclosure (top band in the vertical bar), a share which exceeds that for private action (bottom band) by a wide margin (42.7 vs. 20.5%). In 2013, the positions of these two components have reversed so that involuntary moves caused by private action nearly double those due to foreclosure (40.9% vs. 22.7%). Private action moves also make up the largest component of the base displacement rate depicted in the lowest three bands. The disaster component is the other big gainer besides private action, accounting for only 11.3% of all displacement moves in 2011 but 16.7% by 2013. Both eviction and government action make smaller contributions to displacement at the latter time point than the former; they rank fourth and fifth, respectively, based on the shares shown in the 2013 vertical bar.

Figure 1.

Component Contributions to Fill Displacement, 2011 and 2013

Although the base, expanded, and full rates all appear miniscule, one should not lose sight of the extremely large number of mobile households to which they apply. For 2013, that number is around 25.9 million. When adjustments are made for sampling weights and household size, we estimate that 2.5 million different individuals experienced base displacement during the 24 months before the 2013 survey, being forced to move by private or government action or disaster loss. The human impact of displacement is even greater under the full definition, which adds eviction and foreclosure to the base components. With appropriate adjustments, the 5% of mobile households in the 2013 wave reporting any type of displacement translates into 3.6 million persons. In short, small rates can be deceptive, masking a more impressive magnitude with respect to the sheer numbers of people affected.

4.2. Patterns over time

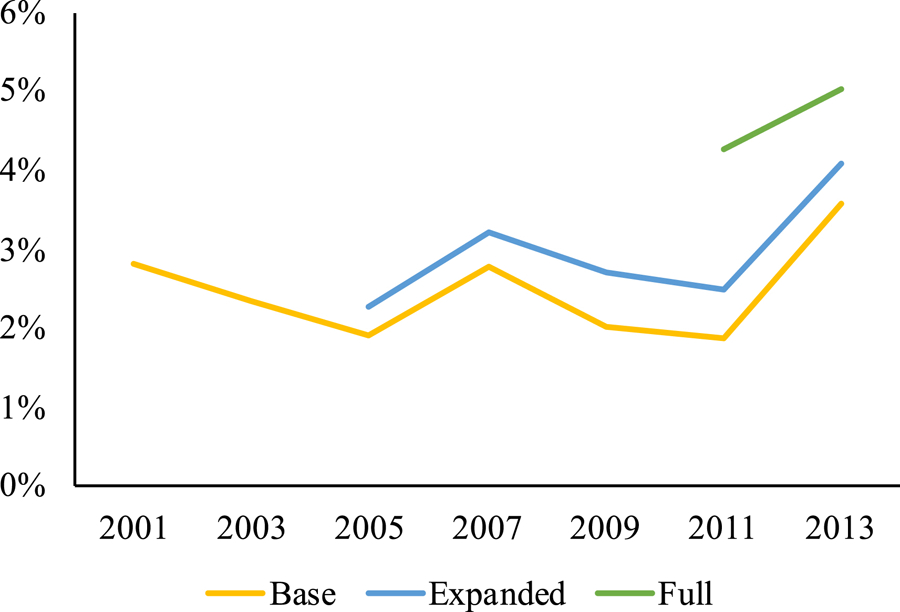

The second question that our research addresses is about displacement patterns from 2001 through 2013 and the possibility of an upward shift in magnitude within that period as multiple types of displacement converge or become more common. The curves in Figure 2 depict changes in the base, expanded, and full rates for mobile households across multiple time points; the base rate is the only one covering the entire study period. While the 2013 base rate does in fact exhibit the highest magnitude (3.6%), much variation occurs prior to that point. A period of decline (2001–2005) is followed by an increase from 2005 through 2007. The base rate then returns to its 2005 level in 2011, only to rise sharply by 2013.3 Unpacking the base rate reveals that disaster displacement is responsible for a larger share of all involuntary moves in 2013 (roughly one-fourth) than in 2001 (less than one-fifth). Despite some ups and downs, private action retains its position as the principal contributor to displacement among the components included in the base measure. It also accounts for most of the marked gain in that rate between 2011 and 2013.

Figure 2.

Summary Displacement Rates for Mobile Households, 2001–2013

The expanded rate (with eviction added) parallels the path of the base rate but at a higher level. After 2007 the gap between the two rates widens, indicative of the growing role played by eviction in forced mobility. The full rate, which adds foreclosure, climbs from 2011 to 2013 but not as dramatically as the base and expanded rates do. This discrepancy reflects a major decrease in the foreclosure component of displacement, from 1.8% to 1.1% of total moves. Such a decrease is not surprising since the 2013 window aligns with the aftermath of the Great Recession and the housing crisis. Completed mortgage foreclosures, which topped out at nearly 1.2 million in 2010, had fallen to 680,000 three years later (CoreLogic 2017).

Does the general trend line observed in the base and expanded displacement rates persist for most kinds of mobile householders? According to Table 2, the answer is yes. The boxed entries in the table identify the highest base rates across 24 socioeconomic and demographic categories of AHS focal householders. Poor householders (fourth row) illustrate the most common pattern, applicable to 20 of the categories. The base rate for the poverty category peaks in 2013 after attaining its second and third highest levels in 2001 and 2007, respectively. Secondary or tertiary ‘bumps’ can be observed for 19 householder categories in 2001 and 15 categories in 2007. These years also contain the peak rates for the four remaining categories. When we shift to the expanded displacement rate, available from 2005 forward, 2013 again represents the modal year in terms of magnitude (see Table A1 of the online appendix).

Table 2.

Base Displacement Rates for Mobile Householders by Characteristic, 2001–2013

| Characteristic | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous Tenure | |||||||

| Owner | 1.75 | 1.57 | 1.31 | 2.17 | 1.77 | .93 |

3.32 |

| Renter | 3.48 | 3.27 | 2.51 | 3.15 | 2.19 | 2.13 | 4.01 |

| Poverty Status | |||||||

| Non-Poor | 2.59 | 2.38 | 1.86 | 2.57 | 1.86 | 1.60 |

3.33 |

| Poor | 4.27 | 3.58 | 2.77 | 3.68 | 2.92 | 2.28 | 6.03 |

| Education | |||||||

| College Grad + | 2.43 | 1.72 | 1.66 | 2.22 | 1.05 | .88 |

3.08 |

| Some College | 2.78 | 2.41 | 1.86 | 2.34 | 2.05 | 1.77 | 4.06 |

| High School | 2.69 | 2.91 | 2.35 | 2.78 | 2.60 | 2.24 | 4.20 |

| < High School | 3.92 | 3.85 | 2.53 |

4.66 |

3.39 | 2.79 | 4.61 |

| Age | |||||||

| < 25 Years | 1.44 | 1.98 | 1.26 | 1.76 | 1.53 | 1.42 |

2.13 |

| 25–64 Years | 3.13 | 2.68 | 2.09 | 2.85 | 2.18 | 1.82 | 4.10 |

| 65 Years + | 3.39 | 2.84 | 3.11 | 4.06 | 2.23 | 1.49 | 4.42 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 2.58 | 2.23 | 2.03 | 2.32 | 2.02 | 1.52 |

3.96 |

| Female | 3.17 | 2.95 | 2.01 | 3.21 | 2.13 | 1.96 | 3.72 |

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Married | 2.59 | 2.46 | 1.68 | 2.47 | 1.93 | 1.97 |

3.45 |

| Divorced/Separated | 3.75 | 2.62 | 2.55 | 3.10 | 2.32 | 1.72 | 4.83 |

| Widowed |

4.87 |

4.81 | 2.88 | 3.78 | 2.45 | 1.15 | 4.45 |

| Never Married | 2.37 | 2.39 | 2.02 | 2.76 | 2.04 | 1.58 |

3.61 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 2.44 | 2.50 | 1.84 | 2.32 | 1.89 | 1.48 |

3.82 |

| Hispanic | 3.31 | 2.43 | 1.78 | 2.37 | 2.20 | 1.49 | 3.78 |

| Black | 4.02 | 3.50 | 2.93 |

5.28 |

2.75 | 2.86 | 4.23 |

| Asian/Other |

3.70 |

1.63 | 2.37 | 2.12 | 1.98 | 2.34 | 3.38 |

| Citizenship | |||||||

| Native Citizen | 2.91 | 2.69 | 2.03 | 2.83 | 1.99 | 1.75 |

3.96 |

| Naturalized Citizen | 2.32 | 1.76 | 2.11 | 2.36 | 1.77 | 1.34 | 3.06 |

| Non-Citizen | 2.58 | 1.97 | 1.90 | 2.35 | 2.92 | 1.89 | 3.29 |

| All Householders | 2.81 | 2.36 | 1.92 | 2.79 | 2.03 | 1.89 | 3.57 |

In general, our results appear at odds with the ‘perfect storm’ scenario. Although the base and expanded rates each consist of multiple components, those components have not ‘added up’ to produce a monotonic increase in displacement prevalence among mobile households during the study period.4 Rather, variability is evident in both the total and category-specific versions of the rates, which have risen between some survey years and fallen between others.

4.3. Predicting displacement

In response to our final research question, we examine focal householder characteristics potentially associated with residential displacement. Logistic regression models are estimated where binary indicators of experiencing base, expanded, or full displacement constitute the dependent variables. Models have been run for every two-year window in which each type of displacement measure is available to assess the consistency of results over time. Although not shown in the tables, all models include controls for the householder’s region of residence and metropolitan status.

To evaluate the role played by various householder attributes throughout the 2001–2013 period, we begin with base displacement as the dependent variable. Table 3 rank orders the householder characteristics according to the number of survey waves in which they predict the likelihood of base displacement (i.e., moving involuntarily because of private or government action or disaster). As can be seen in the odds ratios in the top half of the table, any level of educational attainment short of college graduation (less than high school, high school graduate, some college), renting rather than owning, and middle and late adulthood (ages 25–64 and 65+ relative to young adults under 25) significantly boost the likelihood of displacement among mobile households in three or four of the seven survey years. Moreover, these predictors operate in the direction suggested by previous research.

Table 3.

Significant Predictors from Logistic Regression of Base Displacement on Householder Characteristics, 2001–2013

| Characteristic | Year(s) Significant/Odds Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < High School | 2003 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 |

| 2.09** | 1.83** | 3.30*** | 4.36** | |

| Previous Renter | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2011 |

| 1.92*** | 2.08*** | 1.91*** | 2.08* | |

| High School | 2003 | 2009 | 2011 | |

| 1.57* | 2.83*** | 3.48*** | ||

| 25–64 Years | 2001 | 2003 | 2013 | |

| 2.61*** | 1.62* | 2.65*** | ||

| 65 Years + | 2005 | 2007 | 2013 | |

| 2.70** | 2.65* | 2.87** | ||

| Poor | 2001 | 2013 | ||

| 1.51* | 1.94*** | |||

| Some College | 2009 | 2011 | ||

| 2.16** | 2.30* | |||

| Black | 2005 | 2007 | ||

| 1.53* | 1.79*** | |||

| Asian/Other | 2001 | |||

| 2.05** | ||||

| Non-Citizen | 2001 | |||

| 0.54* | ||||

| Divorced/Separated | 2013 | |||

| 1.37* | ||||

| Naturalized Citizen | 2001 | |||

| 0.45* | ||||

p <0.05

p <0.01

p <0.001

Predictors in the bottom half of the table only achieve statistical significance in one or two years, yet most still conform to directional expectations. For example, the odds of displacement are greater for poor than non-poor households and for blacks, Asians, and divorced, separated, or widowed householders in scattered years than for their white or married reference categories. But the lower odds associated with being foreign born (non-citizen or naturalized citizen) defy easy explanation. We have also conducted logistic regression analyses during the 2005–2013 period using expanded displacement as the dependent variable (adding eviction to the base measure). The pattern of results for base displacement in Table 3 holds for the expanded displacement measure as well (see Table A2 in the online appendix). In general, relatively few householder characteristics are significantly related to either type of displacement across a majority of survey years.

Table 4 presents 2011 and 2013 models with full displacement as the outcome. Recall that these are the only two survey waves in which mortgage foreclosure is included as a reason for moving and for which all relevant householder characteristics are available as predictors. Notably, the odds ratios in the first row suggest that renting instead of owning one’s residence significantly reduces vulnerability to being displaced. This seemingly counterintuitive result reflects the dominance of foreclosure—a component affecting homeowners—when the dependent variable is operationalized as full displacement. As expected, any level of education below completion of college makes displacement more likely among mobile households.5 So does poverty, though significantly only in 2013. Age also matters and, as with base displacement, its impact extends beyond senior citizens. Compared to young adults under 25, focal householders in the 25–64 age category have a greater displacement likelihood in both the 2011 and 2013 models. For seniors, the odds ratio achieves significance only in 2013.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression of Full Displacement on Householder Characteristics, 2011 and 2013

| 2011 |

2013 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | OR | SE | OR | SE |

| Previous Tenure (Renter) | .56 | (.10)*** | .73 | (.09)* |

| Poverty Status (Poor) | 1.41 | (.30) | 1.51 | (.21)** |

| Education (ref. College Grad +) | ||||

| Some College | 2.24 | (.54)*** | 1.32 | (.17)* |

| High School | 2.65 | (.67)*** | 1.45 | (.22)* |

| < High School | 3.83 | (1.23)*** | 1.69 | (.31)** |

| Age (ref. < 25 Years) | ||||

| 25–64 Years | 2.29 | (.78)* | 2.39 | (.48)*** |

| 65 Years + | 1.80 | (.87) | 2.12 | (.64)* |

| Sex (Female) | 1.24 | (.22) | .85 | (.09) |

| Marital Status (ref. Married) | ||||

| Divorced/Separated | .80 | (.18) | 1.28 | −.17 |

| Widowed | 1.01 | (.43) | .83 | (.22) |

| Never Married | .85 | (.17) | 1.01 | (.13) |

| Race/Ethnicity (ref. White) | ||||

| Hispanic | 1.29 | (.32) | .89 | (.15) |

| Black | 1.81 | (.41)** | .97 | (.15) |

| Asian/Other | 1.65 | (.59) | 1.19 | (.27) |

| Citizenship (ref. Native Citizen) | ||||

| Naturalized Citizen | .85 | (.27) | .85 | (.18) |

| Non-Citizen | .94 | (.29) | .76 | (.16) |

| Children Present (yes) | 1.22 | (.22) | 1.12 | (.13) |

| Disability (yes) | 1.88 | (.45)** | 1.42 | (.19)** |

| Government Assistance (yes) | .94 | (.21) | 1.29 | −.18 |

| N | 10,106 | 12,036 | ||

p <0.05

p <0.01

p <0.001

Despite the higher odds of being displaced among blacks (relative to whites) in the 2011 wave, membership in a racial-ethnic minority group does not consistently increase displacement. The odds ratio for black householders falls short of significance in the model for 2013, and the Hispanic and Asian indicator variables show no association with displacement in either year. Like race, neither a householder’s sex, marital status, or citizenship influences the likelihood of displacement in the manner that existing literature would lead us to anticipate. The results for three understudied characteristics, available in the AHS since 2011, are reported in the last few rows of Table 3. Of these characteristics, disability status is the only one that reaches a conventional level of statistical significance. Among mobile householders, having sight, hearing, memory, ambulatory, or other challenges in daily life boosts the odds of being forced to move, even with SES controlled. To the best of our knowledge, no previous investigation has documented this empirical link between disability and displacement.

The unanticipated sign taken by tenure highlights the pivotal role played by the renting versus owning distinction in displacement research. It also raises the question of whether the householder characteristics that influence the likelihood of being displaced are similar or different for mobile renters and owners. In a supplementary analysis (reported in Table A3 of the online appendix), we have rerun the Table 4 logistic regression models separately for renter and owner subsamples. Comparison of the 2013 tenure-specific models indicates that, of the predictors statistically significant in either model, most operate in the same direction. Among both renters and owners, living in poverty, not graduating from college, falling in the middle-adult (25–64) ages, having a disability, and receiving government assistance all increase the risk of displacement. However, only the age variable achieves significance irrespective of tenure. The 2011 tenure models yield similar findings, plus a new one for race. African American renters are significantly more likely to have experienced a forced move compared to their white counterparts, but the odds ratio for black owners (although not significant) takes the opposite sign.

Thus far, our regression-based effort to account for displacement has focused on the particular characteristics of householders that exhibit significant odds ratios. A final empirical issue concerns overall goodness of fit: how well do all of the characteristics perform together in predicting involuntary mobility? To address this, we calculate McFadden’s pseudo-R2, a common fit statistic with values from 0 to 1. It equals .064 and .034 respectively for the 2011 and 2013 full displacement models in Table 4, and it falls in the .032–.122 range when those models are disaggregated by tenure. For the seven models of base displacement summarized in Table 3, the McFadden statistic averages .036 and never exceeds .046 in magnitude. Pseudo-R2s are not equivalent to an OLS regression R2 so their meaning must be interpreted cautiously. Nevertheless, it is clear that the householder characteristics examined here provide a modest improvement at best over an intercept-only model in their ability to predict which movers are likely to be displaced.

5. Conclusion

Residential displacement—moving against one’s will—serves as an apt reminder of the economic insecurity to which a growing number of Americans are exposed. Our study advances displacement scholarship on both conceptual and empirical fronts. We consider multiple definitions of the phenomenon in recognition of how its meaning has broadened over time. This facilitates the development of a components approach that incorporates different combinations of forces conducive to displacement. Despite their limitations and probable downward bias, the AHS national data allow us to examine prevalence estimates and trends during the 2001–2013 period of interest. Finally, we evaluate the contemporary salience of a series of household and individual attributes traditionally associated with the likelihood of being displaced. Each step in the investigation is motivated by the possibility of a ‘perfect storm’ scenario, when conditions converge to produce higher levels of displacement across a wider variety of socioeconomic and demographic groups, in effect shrinking disparities between them.

Our overarching conclusion is that the early 2000s do not achieve perfect storm stature. To be sure, the absolute magnitude of displacement has been far from trivial, with a conservative estimate of 3.6 million people moving involuntarily in the 24-month window prior to the 2013 survey wave. This kind of movement can culminate in negative employment, health, and social network outcomes, not to mention further residential instability. However, relatively few moves qualify as forced, even under the most inclusive operational definition used here. While the base, expanded, and full displacement rates display some ups and downs between 2001 and 2013, they do so within a narrow range and never exceed 5% of mobile households. The longer historical view offered by a handful of pre-2000 national studies (Lee & Hodge 1984; Newman & Owen 1982; US Department of Housing and Urban Development 1979, 1981)—and their somewhat higher estimates—reinforce the ‘ordinary’ character of recent displacement, at least in terms of magnitude.

One difference during the current era is the contribution of mortgage foreclosure, which substantially boosts displacement in 2011 and 2013 (the only two years that the AHS lists foreclosure as a reason for moving). Foreclosure stands out because its frequent occurrence reverses the direction of the tenure effect, although we are not sure that such a reversal would take place earlier in the study period even if the full displacement measure were available.6 Private actions and natural disasters also account for larger shares of forced mobility by 2013, the former even exceeding foreclosure in relative importance. Despite the shifting components of displacement, many householder characteristics are associated with the phenomenon much as they have been in the past. Vulnerability to being displaced is greater not only among renters (without foreclosure included) but among poor and less educated householders. The influence of race is modest in our regression models, yet African Americans still exhibit the highest base and expanded displacement rates of all racial-ethnic groups in nearly every survey year (Tables 2 and A1). So do persons 65 years and older among age groups. Having a disability, a previously overlooked characteristic, is associated with higher odds of displacement as well.

Perhaps the simplest interpretation of the results for householder attributes is that events such as the Great Recession, the foreclosure crisis, and natural hazard disasters have done little to democratize the chances of displacement: many longstanding disparities between advantaged and disadvantaged statuses appear resilient. Qualifying such a view, however, is the underwhelming predictive power of these attributes, both individually and collectively. While they may be statistically significant, their ability to identify substantively meaningful differences in displacement risk across groups remains limited. This unpredictability holds for all recent movers and when mobile renters and owners are examined separately. Moreover, we suspect that it has consequences ‘on the ground.’ Modest disparities of the sort documented by our research could lead to the perception that displacement is essentially random, fueling uncertainty and concern. Such a dynamic might help explain why public interest in the topic is rising in the face of low displacement rates and differentials.

Perceived randomness—the belief that just about anyone could be forced to move regardless of their characteristics—extends beyond displacement to other forms of housing insecurity. Our educated guess is that many Americans know at least one relative, friend, or acquaintance who has struggled with a high housing cost burden, been hypermobile (frequently changing addresses), doubled up with another household, or spent a night in an emergency shelter. Anxiety about residential circumstances can thus emerge vicariously, not only through direct experience. We should also recall, as discussed in the introduction, that housing insecurity does not exist in a vacuum. Rather, it reflects a deeper erosion of economic well-being that has accompanied the withdrawal of institutional supports captured by Hacker’s (2006) risk shift thesis. While this trend has hit non-affluent and marginalized segments of the U.S. population harder than others, members of the middle class have been affected as well. Households who face a real or imagined threat of forced mobility (or of any kind of housing insecurity) may struggle to maintain stable employment, pay their bills, secure adequate health care, and plan for retirement.

The reciprocal connections among these domains complicate efforts to address residential displacement from a policy perspective. So do descriptive studies (like ours) that provide a useful overview of the problem but lack the rigorous quasi-experimental designs needed to develop evidence-based programs and interventions. More helpful is a detailed road map for reducing the likelihood of displacement drawn up by Hartman and colleagues (1982) almost 40 years ago. The strategies that they described target specific causes of forced moves, ranging from disinvestment to government action to gentrification. Recently, a universal housing voucher program has been proposed to deal with eviction (Desmond 2016). While reasonable ideas abound, we believe that their successful implementation depends upon a sustained effort to dramatically increase the number of decent, affordable housing units. This fundamental step would begin to rectify the supply-demand imbalances underlying many components of displacement. Unfortunately, whether the political or fiscal will exists for such an initiative—or whether it would work without attention to other dimensions of economic insecurity—remains far from clear.

Acknowledgement:

Support for this research has been provided by the Population Research Institute at Penn State, which receives infrastructure funding (P2CHD041025) and funding for family demography training (T32HD007514) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content of the article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix

Table A1.

Expanded Displacement Rates for Mobile Householders by Characteristic, 2005–2013

| Characteristic | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous Tenure | |||||

| Owner | 1.54 | 2.36 | 2.20 | 1.16 |

3.87 |

| Renter | 2.94 | 3.77 | 3.11 | 2.68 | 4.66 |

| Poverty Status | |||||

| Non-Poor | 2.08 | 2.84 | 2.44 | 1.79 |

3.82 |

| Poor | 3.75 | 5.04 | 4.23 | 3.72 | 7.05 |

| Education | |||||

| College Grad + | 1.72 | 2.26 | 1.28 | 1.05 |

3.38 |

| Some College | 2.22 | 2.87 | 2.84 | 2.09 | 4.46 |

| High School | 2.64 | 3.26 | 3.43 | 2.75 | 5.15 |

| < High School | 3.53 | 5.69 | 4.91 | 4.14 | 5.74 |

| Age | |||||

| < 25 Years | 1.71 | 2.15 | 1.93 | 1.63 |

2.57 |

| 25–64 Years | 2.42 | 3.32 | 2.96 | 2.28 | 4.68 |

| 65 Years + | 3.41 | 4.43 | 3.18 | 2.37 | 5.42 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 2.33 | 2.56 | 2.74 | 1.73 |

4.53 |

| Female | 2.41 | 3.87 | 2.86 | 2.62 | 4.33 |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 1.91 | 2.80 | 2.47 | 2.10 |

3.86 |

| Divorced/Separated | 3.15 | 3.54 | 3.36 | 2.59 | 5.75 |

| Widowed | 3.49 | 4.47 | 2.91 | 2.95 | 5.36 |

| Never Married | 2.35 | 3.32 | 2.81 | 1.95 | 4.16 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 2.26 | 2.79 | 2.54 | 1.77 |

4.40 |

| Hispanic | 2.03 | 2.64 | 3.28 | 1.97 | 4.27 |

| Black | 3.26 |

5.92 |

3.63 | 4.18 | 4.64 |

| Asian/Other | 2.36 | 2.29 | 2.25 | 2.29 |

4.64 |

| Citizenship | |||||

| Native Citizen | 2.42 | 3.36 | 2.70 | 2.21 |

4.58 |

| Naturalized Citizen | 2.35 | 2.37 | 2.17 | 1.75 | 3.65 |

| Non-Citizen | 1.98 | 2.45 |

3.96 |

2.22 | 3.59 |

| All Householders | 2.26 | 3.22 | 2.72 | 2.48 |

4.09 |

Table A2.

Significant Predictors from Logistic Regression of Expanded Displacement on Householder Characteristics, 2005–2013

| Characteristic | Year(s) Significant/Odds Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < High School | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 |

| 2.08** | 2.13*** | 3.60*** | 4.49*** | 1.48* | |

| Poor | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2013 | |

| 1.58** | 1.43* | 1.55* | 1.90*** | ||

| High School | 2005 | 2009 | 2011 | ||

| 1.51* | 2.88*** | 3.28*** | |||

| Some College | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | ||

| 2.42*** | 2.20* | 1.34* | |||

| 65 Years + | 2005 | 2007 | 2013 | ||

| 2.00* | 2.54* | 2.76** | |||

| Previous Renter | 2005 | 2007 | 2011 | ||

| 1.90*** | 1.48* | 2.06* | |||

| 25–64 Years | 2007 | 2009 | 2013 | ||

| 1.79* | 1.89* | 2.39*** | |||

| Female | 2007 | ||||

| 1.36* | |||||

| Divorced/Separated | 2013 | ||||

| 1.43* | |||||

| Black | 2007 | ||||

| 1.57** | |||||

p <0.05

p <0.01

p <0.001

Table A3.

Logistic Regression of Full Displacement on Householder Characteristics by Previous Tenure Status, 2011 and 2013

| Characteristic | 2011 |

2013 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner |

Renter |

Owner |

Renter |

|||||

| OR | SE | OR | SE | OR | SE | OR | SE | |

| Poverty Status (Poor) | 1.93 | (.71) | 1.10 | (.30)** | 1.38 | (.37) | 1.56 | (.27)** |

| Education (ref. College Grad +) | ||||||||

| Some College | 2.00 | (.74) | 2.20 | (.73)* | 1.57 | (.34)* | 1.36 | (.23) |

| High School | 2.40 | (.94)* | 2.78 | (.92)** | 1.94 | (.52)* | 1.33 | (.26) |

| < High School | 2.30 | (1.12) | 4.52 | (1.87)*** | 2.74 | (.87)** | 1.42 | (.32) |

| Age (ref. < 25 Years) | ||||||||

| 25–64 Years | 5.74 | (4.78)* | 1.72 | (.70) | 3.60 | (1.59)** | 1.93 | ** |

| 65 Years + | 4.33 | (4.50) | 1.93 | (1.09) | 2.89 | (1.65) | 1.90 | (.69) |

| Sex (Female) | 0.91 | (.24) | 1.38 | (.33) | 1.07 | (.19) | 0.77 | (.10)* |

| Marital Status (ref. Married) | ||||||||

| Divorced/Separated | 0.51 | (.18) | 1.14 | (.35) | 1.47 | (.32) | 1.16 | (.20) |

| Widowed | 0.87 | (.77) | 1.25 | (.63) | 0.44 | (.18)* | 1.36 | (.47) |

| Never Married | 0.67 | (.26) | 1.05 | (.30) | 1.10 | (.29) | 0.95 | (.15) |

| Race/Ethnicity (ref. White) | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 1.58 | (.59) | 1.12 | (.17) | 0.81 | (.27) | 0.89 | (.17) |

| Black | 0.65 | (.40) | 2.05 | (.55)** | 1.61 | (.43) | 0.74 | (.13) |

| Asian/Other | 0.91 | (.60) | 1.99 | (.91) | 1.32 | (.46) | 1.07 | (.32) |

| Citizenship (ref. Native Citizen) | ||||||||

| Naturalized Citizen | 1.45 | (.63) | 0.62 | (.30) | 1.10 | (.39) | 0.66 | (.19) |

| Non-Citizen | 2.31 | (1.09) | 0.66 | (.28) | 1.00 | (.41) | 0.72 | (.18) |

| Children Present (yes) | 1.71 | (.49) | 0.96 | (.23) | 1.31 | (.27) | 1.00 | (.14) |

| Disability (yes) | 2.80 | (1.02)** | 1.60 | (.51) | 2.04 | (.46)** | 1.15 | (.20) |

| Government Assistance (yes) | 0.70 | (.23) | 1.18 | (.37) | 1.19 | (.28) | 1.46 | (.24)* |

| N | 2,974 | 6,714 | 3,646 | 7,856 | ||||

p <0.05

p <0.01

p <0.001

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Endnotes

Involuntary mobility and forced moves are used as synonyms for displacement throughout the text.

Social desirability might also shape the focal householder’s survey responses in unpredictable ways. An admission that one has been displaced could prove stigmatizing and thus bias the reporting of this type of mobility in a downward direction. Or, to the contrary, citing forces beyond one’s control could offer cognitive relief for an unwanted move and encourage over-reporting of displacement. The AHS data do not permit us to assess the degree to which these pressures on the respondent balance each other out.

Throughout this span, the actual number of displacees in ‘peak’ years (2001, 2007, 2013) ranges between 2 and 2.5 million people while dipping below 1.5 million in the ‘valleys’ (2005, 2011).

Partial corroboration of this pattern is provided by a recent report from the Princeton Eviction Lab, which shows only minor fluctuations from 2000 through 2016 in the percentage of renter households nationally who have been evicted. The report can be accessed online at https://evictionlab.org/national-estimates/.

In further analysis of the 2011 and 2013 survey data, we have estimated the predicted probability of full displacement associated with each level of educational attainment when the coefficients for all other variables in Table 3 are set at their means. The 2011 probabilities climb steadily from a low of 2.3% for a college graduate to 6.9% for a householder who has not completed high school. Predicted probabilities based on the 2013 wave follow the same monotonic path but within a more restricted range.

As recently as 2005, completed foreclosures numbered less than 300,000 annually, in contrast to roughly 1 million per year during the 2008–2011 peak (CoreLogic 2017).

References

- Allen Ryan. 2013. Postforeclosure mobility for households with children in public schools. Urban Affairs Review 49(1):111–140. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. 2019. Disability and socioeconomic status. Washington, DC: APA; Accessed at https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/disability.html. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Martin. 1967. The federal bulldozer: A critical analysis of urban renewal, 1949–1962. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson Rowland. 2004. The evidence on the impact of gentrification: New lessons for the urban renaissance? European Journal of Housing Policy 4(1):107–131. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson Rowland. 2015. Losing one’s place: Narratives of neighborhood change, market injustice and symbolic displacement. Housing, Theory and Society 32(4):373–388. [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard Robert A. 2003. Voices of decline: The postwar fate of U.S. cities. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard Robert A. 2009. Urban population loss in historical perspective: United States, 1820–2000. Environment and Planning A 41(3):514–528. [Google Scholar]

- Been Vicki, Chan Sewen, Ellen Ingrid Gould, and Madar Josiah R. 2011. Decoding the foreclosure crisis: Causes, responses, and consequences. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 30(2):388–396. [Google Scholar]

- Been Vicki, and Glashausser Allegra. 2008. Tenants: Innocent victims of the nation’s foreclosure crisis. Albany Government Law Review 2(1):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury Katherine L., Downs Anthony, and Small Kenneth A. 1982. Urban decline and the future of American Cities. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Saracino Japonica(ed.). 2010. The gentrification debates. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]