Abstract

Objective

COVID-19 has caused a global healthcare crisis with increasing number of people getting infected and dying each day. Different countries have tried to control its spread by applying the basic principles of social distancing and testing. Healthcare professionals have been the frontline workers globally with different opinions regarding the preparation and management of this pandemic. We aim to get the opinion of healthcare professionals in United Kingdom regarding their perceptions of preparedness in their workplace and general views of current pandemic management strategy.

Method

A questionnaire survey, drafted using Google Forms, was distributed among healthcare professionals working in the National Health Service (NHS) across the United Kingdom. The study was kept open for the first 2 weeks of April 2020.

Results

A total of 1007 responses were obtained with majority of the responses from England (n = 850, 84.40%). There were 670 (66.53%) responses from doctors and 204 (20.26%) from nurses. Most of the respondents (95.23%) had direct patient contact in day to day activity. Only one third of the respondents agreed that they felt supported at their trust and half of the respondents reported that adequate training was provided to the frontline staff. Two-thirds of the respondents were of the view that there was not enough Personal Protective Equipment available while 80% thought that this pandemic has improved their hand washing practice. Most of the respondents were in the favour of an earlier lockdown (90%) and testing all the NHS frontline staff (94%).

Conclusion

Despite current efforts, it would seem this is not translating to a sense of security amongst the UK NHS workforce in terms of how they feel trained and protected. It is vital that healthcare professionals have adequate support and protection at their workplace and that these aspects be actively monitored.

Keywords: COVID-19, Healthcare professionals (HCPs), Personal protective equipment (PPE), National Health Service (NHS)

Highlights

-

•

Only one third of the respondents felt supported at their trust.

-

•

Only half of the respondents reported that adequate training had been provided to frontline staff.

-

•

Two third of the respondents thought there was not enough Personal Protective Equipment available.

-

•

Nearly 90% were in favour of earlier lockdown and testing all the frontline NHS staff for COVID-19.

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), since its outbreak in Wuhan [1], has sent shockwaves across the globe. World Health Organization (WHO) announced a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 30 January 2020 [2] followed by declaring it as a ‘pandemic’ on 11 March 2020 [3]. At present no treatment or vaccine is available for COVID- 19, with only recent proposals emerging for vaccine development [4]. The number of people getting infected and those dying are increasing day by day. As of 12th May 2020 4,193,302 people have been infected and 286,613 have died in 187 countries across the globe [5] while in United Kingdom(UK) 223,060 have been infected with 32,065 deaths [6].

As this pandemic accelerates across the globe, healthcare systems have been put under tremendous strain. For the same reason the strategy adopted globally has been to ‘flatten the curve’ in order to avoid the overburdening of the healthcare system and preventing its collapse [7]. This has been implemented in the form of social distancing and lockdowns. In such dire situations the key is not only to treat the infected but equally essential is to ensure healthcare professionals (HCPs) involved in the care of the patients have a safe working environment. Protection of HCPs is of prime importance because of the risk of infecting other members of the team, patients [8], and indeed family members. Currently 5.7% of the NHS workforce is off sick or in self-isolation [9] with resultant workforce depletion; of more concern is the number of HCP deaths [10], with ethnicity recently questioned as a risk factor. Preventing the spread of infection among medical personnel and then to the patients depends upon the appropriate training and use of the personal protective equipment (PPE) – facemasks, respirators, goggles, face shields, gowns and aprons. Due to the imbalance between the demand and supply, a critical shortage of PPE is expected even in the most developed countries.

Opinions in the UK regarding the shortage of PPE for HCPs, timing of lockdown and testing for COVID-19 have been divided [11,12]. We aimed to get the opinion of HCPs regarding the situation in their respective hospitals along with their opinion on the timings of the lockdown and testing for COVID-19 in UK.

2. Method

2.1. Questionnaire

A 13-item questionnaire was drafted using the Google Forms electronic survey. A combination of forced choice (yes/no) and multiple-choice selections (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree) was used. All questions were mandatory.

The questionnaire collected data regarding region of work, role and direct patient contact. Respondents were asked five questions regarding their trust preparation for the pandemic: whether they felt supported at their trust, availability of adequate facilities (specialist beds, specified isolated areas) to treat COVID-19 patients, availability of enough PPE, whether there was enough local guidance regarding the pandemic and if sufficient local training was provided. Further two questions were related to their daily source of information regarding this pandemic and if it has improved their hand washing practice. Three general questions regarding their views of the pandemic included Britain's preparedness for this pandemic, timing of the lockdown and testing of the frontline NHS staff were asked.

The survey questionnaire is available in the supplementary data appendix.

2.2. Setting

The questionnaire was distributed across the UK to the HCPs working in the NHS through NHS emails, local hospital WhatsApp groups and social media (Facebook and Twitter). In order to reduce bias of the result at a specific point, the survey was kept open for 2 weeks from 01 April 2020 to ascertain the results over the whole period.

2.3. Ethical considerations

NHS research ethics committee approval was not required as this was a study of HCPs who agreed to participate in the online questionnaire. All participants were informed that the information they provide would be confidential and would not be used in a manner to allow identification of the individual responses.

The study has been reported in line with the STROCSS criteria [13].

3. Results

3.1. Respondents

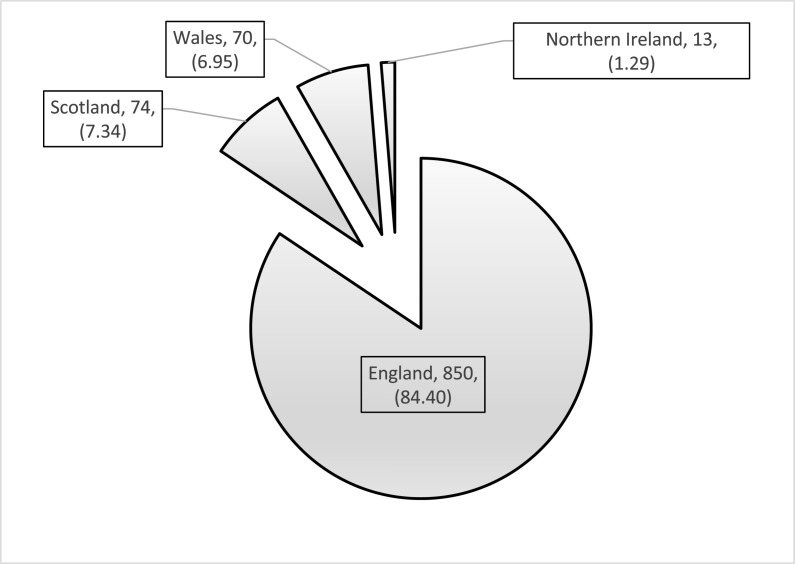

There were a total of 1007 responses. Majority of respondents (n = 850, 84.40%) were from England followed by Scotland (n = 74, 7.34%), Wales (n = 70, 6.95%) and Northern Ireland (n = 13, 1.29%) (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Regional distribution (n, %).

3.2. Role

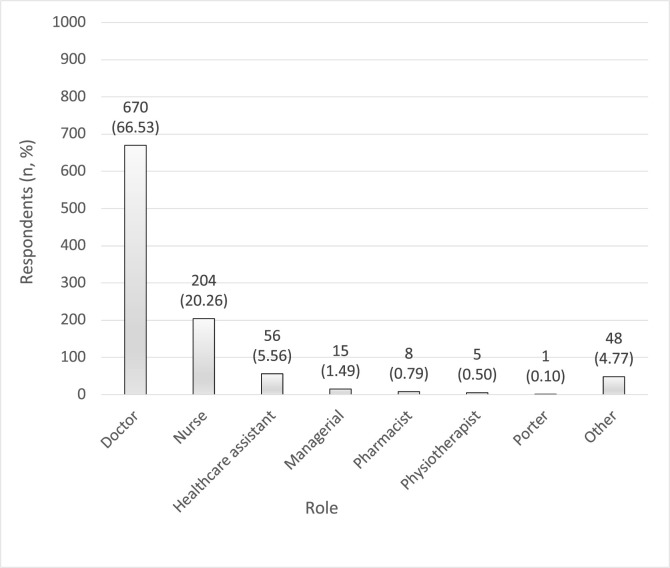

66.53% (n = 670) of the respondents were doctors, 20.26% (n = 204) nurses and 5.56% (n = 56) healthcare assistants (Fig. 2 ). 95.23% (n = 959) of the respondents had direct patient contact in daily routine.

Fig. 2.

Role of respondents (n, %).

3.3. Hospital situation

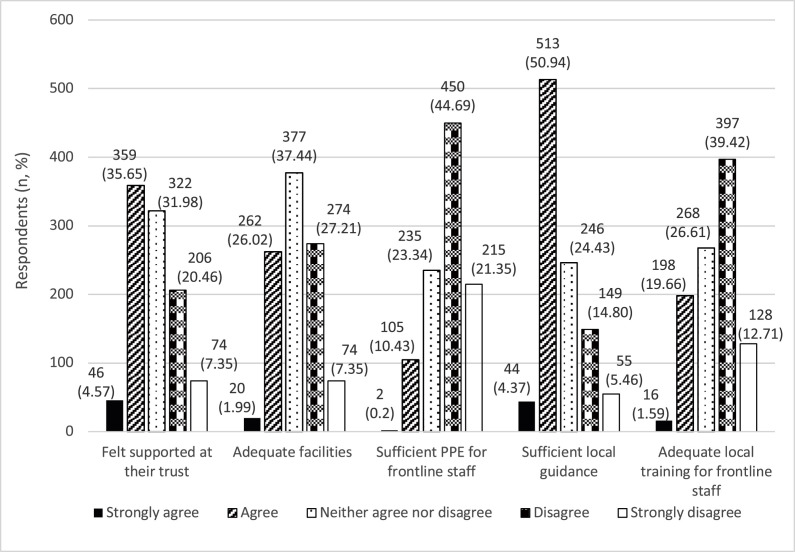

A total of 40.21% (n = 405) respondents “felt supported at their trust” and 27.80% (n = 280) did not while 31.98% (n = 322) remained neutral (neither agreed nor disagreed). With regards to the “availability of adequate facilities (specialist beds, specified isolated areas) in their trust”, 34.55% (n = 348) were of the view that such facilities were not available while only 28% (n = 282) were in agreement regarding their availability. Two-third of the respondents (n = 665, 66.03%) did not think that “adequate PPE were available to the frontline staff”. Nearly half of the respondents (n = 557, 55.31%) were of the view that there was “enough local guidance available at their trust” while approximately the same (n = 525, 52.13%) responded that “sufficient local training was not provided to the frontline staff” (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Hospital situation (n, %).

A comparison of the responses based on geographical location (Table 1 ), indicated respondents from England felt least supported at their trust (30.00%) whilst a larger percentage from Scotland felt maximally supported (56.75%). 39.18% of the respondents from Scotland thought adequate specialist facilities were available at their trust as compared to 28.57% from Wales and 27.17% from England. A third of the respondents from Scotland (32.43%) thought adequate PPE was not available while in other regions nearly two-third of the respondents were not happy with the availability of PPE (Northern Ireland: 61.53%, England: 68.11%, Wales: 77.14%). Scotland had the highest percentage of the respondents who were happy with the local guidance available (74.32%).

Table 1.

Hospital situation responses based on Geographical Location {n (%)}.

(SA: strongly agree, A: agree, N: neither agree nor disagree, D: disagree, SD: strongly disagree).

| RESPONSE | ENGLAND 850 (84.40) | SCOTLAND 74 (7.34) | WALES 70 (6.95) | NORTHERN IRELAND 13 (1.29) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FELT SUPPORTED | SA | 41 (4.82) | 2 (2.70) | 3 (4.28) | 0 (0) |

| A | 281 (33.05) | 40 (54.05) | 32 (45.71) | 6 (46.15) | |

| N | 273 (32.11) | 25 (33.78) | 18 (25.71) | 6 (46.15) | |

| D | 188 (22.11) | 7 (9.45) | 10 (14.28) | 1 (7.69) | |

| SD | 67 (7.88) | 0 (0) | 7 (10.00) | 0 (0) | |

| ADEQUATE SPECIALIST FACILITIES | SA | 18 (2.11) | 1 (1.35) | 1 (1.42) | 0 (0) |

| A | 213 (25.05) | 28 (37.83) | 19 (27.14) | 2 (15.38) | |

| N | 315 (37.05) | 36 (48.64) | 20 (28.57) | 6 (46.15) | |

| D | 243 (28.58) | 7 (9.45) | 19 (27.14) | 5 (38.46) | |

| SD | 61 (7.17) | 2 (2.70) | 11 (15.71) | 0 (0) | |

| SUFFICIENT PPE | SA | 2 (0.23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| A | 84 (9.88) | 14 (18.91) | 7 (10.00) | 0 (0) | |

| N | 185 (21.76) | 36 (48.64) | 9 (12.85) | 5 (38.46) | |

| D | 392 (46.11) | 18 (24.32) | 33 (47.14) | 7 (53.84) | |

| SD | 187 (22.00) | 6 (8.10) | 21 (30.00) | 1 (7.69) | |

| SUFFICIENT LOCAL GUIDANCE | SA | 40 (4.70) | 3 (4.05) | 1 (1.42) | 0 (0) |

| A | 417 (49.05) | 52 (70.27) | 36 (51.42) | 8 (61.53) | |

| N | 213 (25.05) | 14 (18.91) | 14 (20.00) | 5 (38.46) | |

| D | 129 (15.17) | 4 (5.40) | 16 (22.85) | 0 (0) | |

| SD | 51 (6.00) | 1 (1.35) | 3 (4.28) | 0 (0) | |

| ADEQUATE LOCAL TRAINING | SA | 14 (1.64) | 1 (1.35) | 1 (1.42) | 0 (0) |

| A | 167 (19.64) | 18 (24.32) | 12 (17.14) | 1 (7.69) | |

| N | 208 (24.47) | 35 (47.29) | 20 (28.57) | 5 (38.46) | |

| D | 346 (40.70) | 18 (24.32) | 26 (37.14) | 7 (53.84) | |

| SD | 115 (13.52) | 2 (2.70) | 11 (15.71) | 0 (0) | |

Responses regarding the hospital situation between different HCPs were comparable (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Hospital situation responses based on Healthcare professionals {n (%)}.

(SA: strongly agree, A: agree, N: neither agree nor disagree, D: disagree, SD: strongly disagree, HCA: Healthcare assistants, MISCELLANEOUS includes managers, pharmacists, physiotherapists, porters and others).

| RESPONSE | DOCTORS 670 (66.53) | NURSES & HCAs 260 (25.81) | MISCELLANEOUS 77 (7.64) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FELT SUPPORTED | SA | 26 (3.88) | 15 (5.76) | 5 (6.49) |

| A | 223 (33.28) | 109 (41.92) | 27 (35.06) | |

| N | 207 (30.89) | 86 (33.07) | 29 (37.66) | |

| D | 155 (23.13) | 42 (16.15) | 9 (11.68) | |

| SD | 59 (8.80) | 8 (3.07) | 7 (9.09) | |

| ADEQUATE SPECIALIST FACILITIES | SA | 11 (1.64) | 7 (2.69) | 2 (2.59) |

| A | 170 (25.37) | 75 (28.84) | 17 (22.07) | |

| N | 250 (37.31) | 94 (36.15) | 33 (42.85) | |

| D | 189 (28.20) | 67 (25.76) | 18 (23.37) | |

| SD | 50 (7.46) | 17 (6.53) | 7 (9.09) | |

| SUFFICIENT PPE | SA | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.38) | 0 (0) |

| A | 63 (9.40) | 40 (15.38) | 2 (2.59) | |

| N | 170 (25.37) | 51 (19.61) | 14 (18.18) | |

| D | 296 (44.17) | 121 (46.53) | 33 (42.85) | |

| SD | 140 (20.89) | 47 (18.07) | 28 (36.36) | |

| SUFFICIENT LOCAL GUIDANCE | SA | 26 (3.88) | 10 (3.84) | 8 (10.38) |

| A | 347 (51.79) | 136 (52.30) | 30 (38.96) | |

| N | 167 (24.92) | 62 (23.84) | 17 (22.07) | |

| D | 95 (14.17) | 37 (14.23) | 17 (22.07) | |

| SD | 35 (5.22) | 15 (5.76) | 5 (6.49) | |

| ADEQUATE LOCAL TRAINING | SA | 10 (1.49) | 3 (1.15) | 3 (3.89) |

| A | 136 (20.29) | 52 (20.00) | 10 (12.98) | |

| N | 172 (25.67) | 67 (25.76) | 29 (37.66) | |

| D | 272 (40.59) | 100 (38.46) | 25 (32.46) | |

| SD | 80 (11.94) | 38 (14.61) | 10 (12.98) | |

3.4. Personal practice

For “daily source of information regarding the COVID-19 pandemic”, nearly half of the respondents (n = 558, 55.41%) used multiple sources (daily hospital emails, news, social media, Gov.uk, friends and family and other health professionals) while a quarter (n = 249, 24.73%) relied on daily hospital emails (Table 3 ). 80.73% (n = 813) of the respondents thought that this “outbreak has improved their hand washing practice” (Table 4 ).

Table 3.

Daily source of information (n, %).

| Daily source of information | Respondents (n, %) |

|---|---|

| Daily hospital emails | 249 (24.73) |

| News | 97 (9.63) |

| Social media | 42 (4.17) |

| Gov.uk | 29 (2.88) |

| Friends and family | 4 (0.40) |

| Health professionals | 28 (2.78) |

| All of the above | 558 (55.41) |

Table 4.

Hand washing practice (n, %).

| Hand washing improved | Respondents (n, %) |

|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 412 (40.91) |

| Agree | 401 (39.82) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 135 (13.41) |

| Disagree | 49 (4.87) |

| Strongly disagree | 10 (0.99) |

3.5. General management of the pandemic

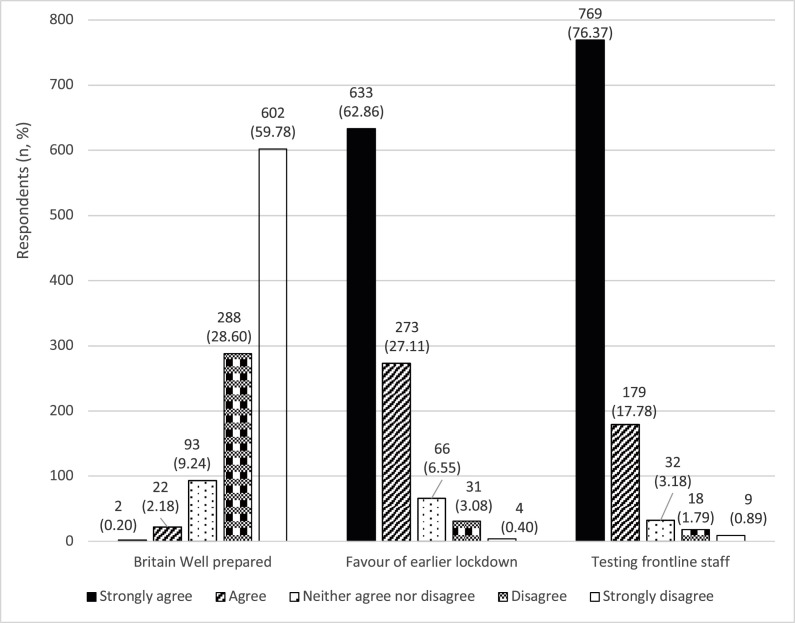

When asked if “Britain was well prepared for this pandemic”, majority (n = 890, 88.38%) of the respondents were not in agreement . Similarly, most of the respondents (n = 906, 89.97%) thought that an “earlier lockdown would have helped much better”. With regards to “testing the frontline staff for COVID-19”, 94.14% (n = 948) recommended in favour of it (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

General management of the pandemic (n, %).

4. Discussion

The survey gives a broad overview of HCPs’ views regarding the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. A key point to highlight is that 95% of the respondents are those who have direct patient contact in day to day activities and so are key frontline staff. They are the ones who are at constant risk.

It is vitally important that HCPs feel supported and protected at their workplace in this crisis and they have a safe working environment. A number of HCPs have lost their lives in the current COVID-19 crisis. As of 20th April 2020, Government figures stand at 49 deaths for HCPs while 102 deaths had been reported in news [10,14] which according to the latest figures have increased to 201 [15]. This may have bearing on the mental health and morale of the HCPs as well [16]. Our survey showed that only 40% of the respondents felt supported at their trust in the current crisis. The causation of this can be multifactorial which were beyond the scope of this survey.

UK PPE guidelines published on 2nd April 2020 [17] recommends use of gowns instead of aprons, mandatory eye protection and guidance on the use of FFP3 masks with further updates on 9th April 2020 [18]. The daily media briefing emphasises that millions of pieces of PPE are being made available to health workers in the UK. This is in line with the Health & Safety Executive's directive on PPE, including the employer's duty in the provision and use of these [19]. The emphasis here is of course on the risk of contamination from air-borne pathogens [20]. Currently this consists of guidelines stratified according to the level of exposure with the maximal protection level consisting of full body coverage and wearing of N95 respirator (e.g. FFP3) masks. The key regulations (Personal Protective Equipment at Work Regulations 1992) [21] surrounding the use of PPE in this crisis hinge on (i) proper assessment to assess fitness for purpose (ii) provision of instructions on safe use (iii) ensuring correct usage by employees. There has been a lot of concern regarding the availability of adequate PPE for the frontline staff [12]. Guidance in itself offers no protection till the resources are available for implementation of such guidelines and adequate training provided. Two-third of the respondents in our survey did not think that adequate PPE was available while approximately 50% did not receive adequate local training. A survey (snapshot over 24 h) carried out by the Royal College of Physicians [22] in the first week of April revealed 78% respondents could access PPE. A similar survey by the Royal College of Surgeons [23] in the second week of April demonstrated that a third of the surgeons and trainees did not believe that they have adequate PPE supply and about 57% thought that there have been shortages of PPE in the last 30 days preceding the survey.

The General Medical Council's (GMC) guidance on safety revolves primary around patient safety. From a generic standpoint, the area relating to doctors' health alludes to suspecting oneself of having a communicable condition and responding to it appropriately. Trainees have been asked to not undertake activities beyond their competence, with an overview maintained by the relevant postgraduate dean [24], though there is a recognition that there will be an increasing need for trainees to support local healthcare systems. It would not be unreasonable to consider that it is not within the GMC's remit to advise on PPE, but they are engaged with the national directives, having produced an advisory webpage in this respect, dealing with doctors' wellbeing, protection in both the inpatient and outpatient setting, and maintaining standards of practice during the pandemic [25].

Similar to the GMC, the Nursing Medical Council (NMC) clearly recognises the concerns around the availability and usage of appropriate PPE and have outlined key principles in their Code and Standards statement [26]. The Royal College of Nursing have also recognised ongoing concerns regarding PPE shortage in line with the responses in this survey [27].

Recommendations from the WHO [28] were “to use every possible tool to suppress the transmission of the virus” meaning isolating cases, contact tracing and testing. In the early phase of this pandemic in UK, initial contact tracing was started but on 12 March 2020 it was decided to stop community case-finding and contact tracing [11] despite a report published on 9 March 2020 [29] had suggested that biggest impact on cases and deaths would be from social distancing and protection of vulnerable groups. Another report published on 16 March 2020 had suggested that in worst case scenario 250,000 people would die in UK [30]. A lockdown was finally imposed on the 23rd March 2020. Was it already too late? In our survey a staggering 88.38% (890/1007) of the respondents were not happy with Britain's preparation and 89.97% (906/1007) were in the favour of an earlier lockdown.

Another issue which has been the highlighted is testing of NHS frontline staff for COVID-19 [31]. This is essential not only from health and safety point of view but also from the workforce point of view because the last thing one would want in such a situation is key workers being off sick. A survey by the Royal College of Physicians [22] reported around 18% of the respondents off work either due to sickness or isolation. Government figures suggested 5.7% of the hospital doctors were off sick or absent because of Covid-19 [9]. Many of them may have been isolating due to contact rather than actual symptoms so would not qualify for testing. In our survey 94.14% (948/1007) were in favour of testing the frontline staff.

This was a large scale national study of HCPs who gave a broad overview of the COVID-19 situation during the study period. Most of the findings of the study are parallel to what has been reported in news. Limitations of the study include that reasoning of the respondents’ reply was not asked and bias may have been present depending upon the geographical region. Even with these limitations, we believe the findings of our study provide a meaningful insight into the concerns of the HCPs.

5. Conclusion

Despite current national efforts, it would seem this is not translating to a sense a security amongst the UK NHS workforce in terms of how they feel trained and protected. It is vital that HCPs have adequate support and protection at their workplace. Employers have a legal responsibility to provide these. Importance of increasing the access to PPE and testing needs to be highlighted.

Funding

No funding.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed

Data statement

The survey respondents were assured raw data would remain confidential and would not be shared or used to identify the individual responses.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Muhammad Rafaih Iqbal: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Arindam Chaudhuri: Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

No conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the healthcare professionals who participated in the survey.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.042.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Lu H., Stratton C.W., Tang Y.W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(4):401–402. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sohrabi C., Alsafi Z., O'Neill N., Khan M., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID- 19) Int. J. Surg. 2020;76:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 Available from.

- 4.University of Oxford Oxford COVID-19 vaccine programme opens for clinical trial recruitment 27 March 2020. http://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2020-03-27-oxford-covid-19-vaccine-programme-opens-clinical-trial-recruitment Available from.

- 5.Johns Hopkins University of Medicine Coronavirus resource center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html Available from.

- 6.Gov.uk Number of coronavirus (COVID-19) cases and risk in the UK. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/coronavirus-covid-19-information-for-the-public Available from.

- 7.Wang X., Zhang X., He J. Challenges to the system of reserve medical supplies for public health emergencies: reflections on the outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) epidemic in China. Biosci Trends. 2020;14(1):3–8. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wax R.S., Christian M.D. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d'anesthésie. 2020;67(5):568–576. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01591-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Booth R. 05 April 2020. Number of NHS Doctors off Sick ‘may Be Nearly Triple the Official Estimate’ the Guardian. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook T., Kursumovic E., Lennane S. 2020. Exclusive: Deaths of NHS Staff from Covid-19 Analysed. HSJ. April) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward H. The Guardian; 15 April 2020. We Scientists Said Lock Down. But Politicians Refused to Listen. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doctors Still Facing Potentially 'fatal' Consequences of Treating Patients without Adequate Covid-19 Protection. warns BMA [press release]; 31.03.2020. BMA. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agha R., Abdall-Razak A., Crossley E., Dowlut N., Iosifidis C., Mathew G. STROCSS 2019 Guideline: strengthening the reporting of cohort studies in surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2019;72:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.11.002. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marsh S. The Guardian; 20 April 2020. Doctors, Nurses, Porters, Volunteers: the UK Health Workers Who Have Died from Covid-19. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riches C. 09 May 2020. Coronavirus Crisis: Health Worker Heroes Death Toll Passes 200. Express. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberg N., Docherty M., Gnanapragasam S., Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gov.uk New personal protective equipment (PPE) guidance for NHS teams 02 April 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-personal-protective-equipment-ppe-guidance-for-nhs-teams Available from.

- 18.Govuk Recommended PPE for healthcare workers 09 April 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/879107/T1_poster_Recommended_PPE_for_healthcare_workers_by_secondary_care_clinical_context.pdf Available from.

- 19.Health and Safety Executive. Personal protective equipment (PPE) at work. https://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/indg174.pdf Available from.

- 20.Health and Safety Executive. Risk at work - personal protective equipment (PPE) https://www.hse.gov.uk/toolbox/ppe.htm Available from.

- 21.legislation.gov.uk The personal protective equipment at work regulations 1992. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1992/2966/contents/made Available from.

- 22.Royal College of Physicians COVID-19 and its impact on NHS workforce. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/news/covid-19-and-its-impact-nhs-workforce Available from.

- 23.Royal College of Surgeons of England Survey results: PPE and testing for clinicians during COVID-19. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/news-and-events/news/archive/ppe-and-testing-covid-survey-results/ Available from.

- 24.General Medical Council Supporting the Covid-19 response: guidance regarding medical education and training. https://www.gmc-uk.org/news/news-archive/guidance-regarding-medical-education-and-training-supporting-the-covid-19-response Available from.

- 25.General Medical Council Coronavirus: your frequently asked questions. https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-hub/covid-19-questions-and-answers#Leadership Available from.

- 26.Nursing Medical Council: NMC statement on personal protective equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic. https://www.nmc.org.uk/news/news-and-updates/nmc-statement-on-personal-protective-equipment-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/ Available from.

- 27.Royal College of Nursing: personal protective equipment: use and availability during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.rcn.org.uk/news-and-events/news/half-of-nursing-staff-under-pressure-to-work-without-ppe-reveals-rcn Available from.

- 28.World Health Organization: WHO-China joint mission on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/who-china-joint-mission-on-coronavirus-disease-2019-(covid-19 Available from.

- 29.Gov.uk Potential impact of behavioural and social interventions on a Covid-19 pandemic in the UK. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/874290/05-potential-impact-of-behavioural-social-interventions-on-an-epidemic-of-covid-19-in-uk-1.pdf Available from.

- 30.Ferguson N. Imperial College COVID-19 response team; 2020. Report 9: Impact of Non-pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) to Reduce COVID-19 Mortality and Healthcare Demand. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gov.uk Government to extend testing for coronavirus to more frontline workers. https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-of-health-and-social-care Available from.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.