Coronavirus (COVID-19) was first detected in November 2019 (Chan et al. 2020). The infection spread quickly in Wuhan (the capital of the Chinese province of Hubei) and then throughout China and other countries including the Russian Federation (RF) and Republic of Belarus (RB). In early May, more than 190,000 Russians and 20,168 Belarusian were infected (Johns Hopkins University 2020).

Russia and Belarus were part of the former Soviet Union and have a similar culture—a single written language and common religion; also, there are close economic and political relations. However, Russia and Belarus have chosen different strategies in fighting COVID-19.

Russia has taken a path similar to most European countries—strict quarantine (self-isolation), movement restriction, social distancing, mandatory use of personal protective equipment including masks and gloves, public event bans, as well as border and air traffic closures. In comparison, Belarus has not endorsed quarantine and has proceeded with “life as usual” without closing borders, businesses, restaurants, museums, cinemas, schools, or universities. It has imposed a 2-week quarantine of Belarusian citizens who came from countries with the coronavirus epidemic.

Pandemic-related conditions are linked to negative economic consequences effecting living conditions at all levels (Atkeson 2020; Baker et al. 2020) and increased mental health incidents. Evidence about the psychological impact of coronavirus points to conditions of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and suicide (Galea et al. 2020; Sorokin et al. 2020; Wan 2020) as well as confusion, anger, fear, boredom, stigma, and stress over the loss of life-sustaining resources (Brooks et al. 2020; Pakpour and Griffiths 2020). Substance use, especially tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and prescription drugs, tends to be increased as a means of coping and self-medication (Brooks et al. 2020; Slaven et al. 2017). We hypothesized COVID-19-related fear, stress, anxiety, and substance use among Russian and Belarusian university students are significantly linked to their background characteristics and country methods used to control infection.

Setting, Instruments, and Sample

The Qualtrics software platform was used for this online survey. The main data collection instrument was the seven-item Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) (Ahorsu et al. 2020). The levels of agreement with FCV-19S statements were evaluated by a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher total scores correspond with more COVID-19 fear. Two questions were added to the scale to determine COVID-19 impact on university student studies, social life, and family relations. The influence of COVID-19 on student substance use including tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and prescription drugs was examined as well. The survey instrument was translated to Russian and back translated to English by three English-speaking lecturers from universities in Russia and Belarus to ensure uniform content and vocabulary. The translation method used is consistent with that described by the World Health Organization for research purposes (WHO 2020). After translating to Russian, the instrument was tested on a sample Russian and Belarusian students. The scale evidenced high reliability (Reznik et al. 2020). For this study, all statistical analyses are being conducted using SPSS, version 25.

Results

This survey included 939 participants, 76.1% (n = 715) from Russia and 23.9% (n = 224) from Belarus, 80.8% (n = 757) female and 19.2% (n = 180) male. The mean age of the respondents is 21.8 years (SD = 5.4). Table 1 provides background characteristics of the survey respondents.

Table 1.

Student demographic characteristics

| Russia (n = 715) |

Belarus (n = 224) |

Total (n = 939) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, % (n) | |||

| Male | 19.4 (138) | 18.5 (41) | 19.2 (180) |

| Female | 80.6 (576) | 81.5 (181) | 80.8 (757) |

| Age | *** | *** | |

| Mean (SD) | 22.4 (5.8) | 20.0 (3.2) | 21.8 (5.4) |

| Median | 21.0 | 19.0 | 20.0 |

| Range | (17–60) | (17–46) | (17–60) |

| Religious, % (n) | *** | *** | |

| Not religious | 43.4 (307) | 27.3 (60) | 39.5 (367) |

| Religious | 56.6 (401) | 72.7 (160) | 60.5 (561) |

| Major field of study, % (n) | *** | *** | |

| Medicine | 22.9 (160) | 95.4 (209) | 40.2 (369) |

| Psychology | 52.0 (364) | 0.9 (2) | 39.8 (366) |

| Other (education, social work, journalism, etc.) | 25.1 (176) | 3.7 (8) | 20.0 (184) |

| Health status, % (n) | *** | *** | |

| Healthy | 94.2 (851) | 85.1 (188) | 92.0 (839) |

| Had contact with people who infected the COVID-19 | 2.5 (17) | 10.4 (23) | 4.4 (40) |

| Were infected or/and sick with the COVID-19 | 3.3 (23) | 4.5 (10) | 3.6 (33) |

| Quarantine limitations % (n) | *** | *** | |

| Quarantine or strict self- isolation with limitations of social contacts | 61.0 (422) | 34.5 (76) | 54.6 (498) |

| Self-isolation with the ability to move and social contacts | 30.2 (209) | 44.1 (97) | 33.6 (306) |

| Without limitations | 8.8 (61) | 21.4 (47) | 11.8 (108) |

***p < 0.001 (χ2 test and t test for age)

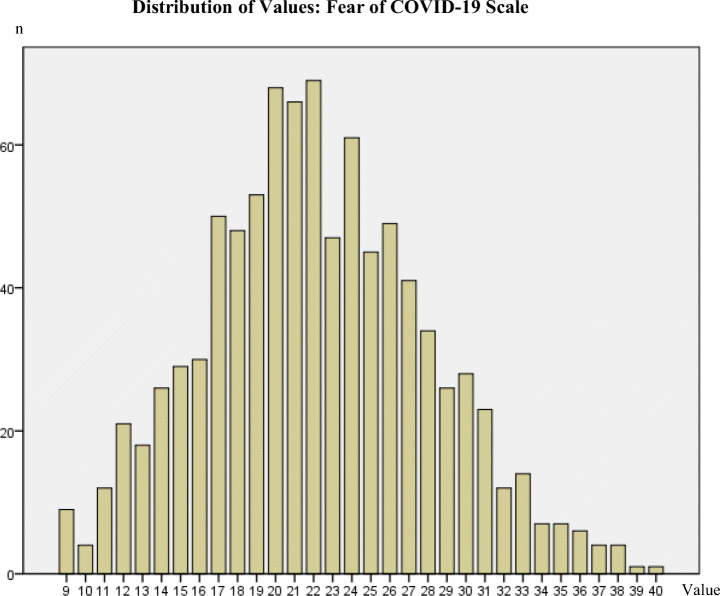

For the total sample, mean value of the FCV-19S is 22.2 (SD = 5.9), median = 22.0, with a range of 9 to 40. The scale used shows good Cronbach’s Alpha measure of internal consistency or reliability (0.803). Based on the distribution of the results, we gradated the fear values ranging from 9 to 40 to represent the following levels: Low—9 to 19 scores (n = 300); Medium—20 to 24 scores (n = 311); and, High—25–40 scores (n = 302). Figure 1 shows the total distribution of the fear values. A weak correlation was found between the age of the respondents and fear (r = − 0.130; p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of values: fear of COVID-19 Scale

No significant difference was found regarding COVID-19 fear based on student country status—Russia or Belarus. Data from both countries about COVID-19 fear show: females have a significantly higher level than males (t909 = 2.709; p = 0.007); and, religious students report a higher level than those of secular status (t900 = 2.132; p = 0.033). One-way ANOVA shows that quarantine/self-isolations restrictions significantly impact fear values (F2,894 = 18.920; p < 0.001) regardless of country surveyed.

Student substance use rates, at least once during the month before COVID-19, were 31.1% tobacco, 58.2% alcohol, 1.7% cannabis, 1.5% Ritalin or similar substances, 13.8% pain relievers, and 6.5% sedatives. Males more than females use tobacco (i.e., cigarettes) (47.6% vs. 27.2%; p < 0.001) and cannabis, which are prohibited in both countries (4.6% vs. 1.0%; p = 0.002). Females more than males use pain relievers (15.9% vs. 5.2%; p = 0.001). Secular more than religious students use cigarettes (40.8% vs. 24.4%; p < 0.001), alcohol (62.9% vs. 54.8%; p < 0.017), cannabis (4.0% vs. 0.2%, p < 0.001), and sedatives (9.4% vs. 4.3%; p =0.003). Russian students, compared to those from Belarus, use more tobacco (33.9% vs. 21.0%; p = 0.001) and pain relievers (16.0% vs. 5.6%; p < 0.001). Those who reported last month substance use before COVID 19 report their use increased as a COVID-19 consequence. Among substance users, the following increases were reported: 35.6% tobacco, 29.6% alcohol, 27.3% cannabis, 16.7% Ritalin or similar substance, 18.2% pain relievers, and 23.5% sedatives. Russian and Belarusian students under quarantine/strict self-isolation conditions had a significantly higher rate of alcohol use than those not restricted (34.3% vs. 24.6%; p = 0.017).

Respondents who reported increased tobacco and alcohol use had higher fear scores (cigarettes smoking t257 = 2.503; p = 0.013; and alcohol use t495 = 2.512; p = 0.012). Also, respondents who reported increased alcohol use, compared to those who did not, had higher levels of depression (67.2% vs. 51.6%; p = 0.005), exhaustion (46.5% vs. 35.2%; p = 0.026), loneliness (65.1% vs. 48.8%; p = 0.002), nervousness (73.2% vs. 53.4%; p < 0.001), and anger (55.9% vs. 41.2; p = 0.004). Last month binge drinking because of COVID-19 was reported by 7.1% of the survey respondents—Russian more than Belarusian (8.2% vs. 2.7%; p = 0.009), male more than female (18.0% vs. 4.5%; p < 0.001), and secular more than religious (10.3% vs. 5.0%; p = 0.005) students. No significant differences were found linking binge drinking to fear.

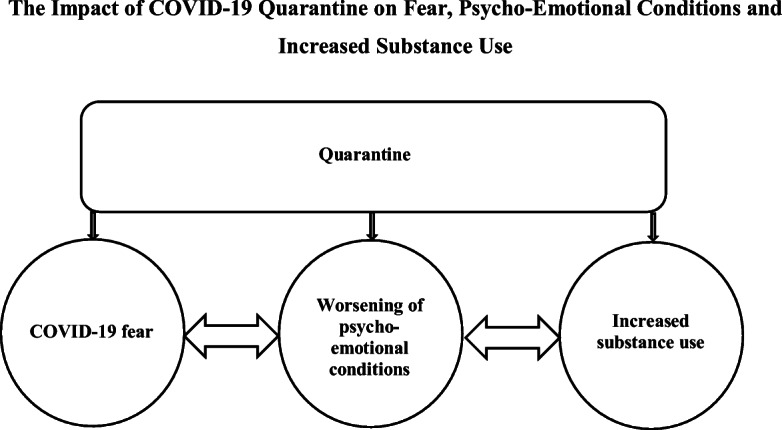

Russian students, compared to those from Belarus, were more inclined to report being depressed (52.9% vs. 41.8%; p = 0.008), exhausted (40.1% vs. 23.9%; p < 0.001), nervous (57.3% vs. 42.9%; p = 0.001), and angry (44.7% vs. 28.5%; p < 0.001) due to COVID-19. Students from both countries, students in quarantine/strict self-isolation conditions, compared to those not, felt more depressed (55.8% vs. 44.4%; p = 0.001), exhausted (42.9% vs. 29.5%; p < 0.001), lonely (56.3% vs. 41.7%; p < 0.001), nervous (60.4% vs. 45.9%; p < 0.001), and angry (45.2% vs. 36.4%; p = 0.012) due to COVID-19. Table 2 shows the distribution of COVID-19 fear level responses to students’ physical and emotional conditions. Figure 2, based on study results, shows the path of COVID-19 quarantine to fear, psycho-emotional conditions, and increased substance use.

Table 2.

Distribution of COVID-19 fear level responses to students physical and emotional conditions

| Level of COVID-19 Fear | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| During the last month, because of COVID-19, felt more | Low (n = 300) |

Medium (n = 311) |

High (n = 302) |

| Depressed, % (n) | 29.1 (82)*** | 49.0 (141)*** | 71.3 (196)*** |

| Exhausted, % (n) | 19.4 (54)*** | 33.6 (98)*** | 55.5 (152)*** |

| Lonely, % (n) | 33.6 (94)*** | 49.7 (146)*** | 64.9 (179)*** |

| Nervous, % (n) | 35.0 (100)*** | 53.8 (163)*** | 71.4 (205)*** |

| Angry, % (n) | 25.8 (73)*** | 41.4 (121)*** | 56.2 (150)*** |

***p < 0.001 (χ2 test)

Fig. 2.

The impact of COVID-19 quarantine on fear, psycho-emotional conditions and increased substance use

Discussion

Studies show pandemic, such as COVID-19 increases psychological stress; and, the consequences of quarantine lead to emotional disturbance, depression, irritability, insomnia, anger, and emotional exhaustion among other health and mental health conditions (Brooks et al. 2020; Sorokin et al. 2020). Present findings are consistent with those of prior studies and evidence that students who are religious tend to have a higher level of fear than those who are secular. This outcome is contrary to the belief that religiosity is a protective factor that helps a person overcome difficult life circumstances and promotes psychological well-being (Howell et al. 2019; Koenig 2015). However, studies of religiosity in Russia and Belarus show it may be declarative in nature to a large extent and not accompanied by regular religious practice such as attending church on a regular basis and receiving communion (prayers, church visits, religious observance of restrictions, etc.) (Tikhomirov 2017; Zabaev et al. 2018).

Present study results, based on multiple psychological, mental health, and substance use factors evidence the impact of quarantine. Overall, university students from Belarus where there is less quarantine/self-isolation restrictions report more positive psycho-emotional conditions and less substance use than those from Russia. In addition, it is worth noting that the official Belarusian media are more cautious in covering the pandemic and tend to downplay its scope and consequences compared to Russia, where there is an overabundance of often controversial information about COVID-19 (Sorokin et al. 2020; Zogg 2020).

Limitations

The present study has limitations. For example, an online survey makes it difficult to generate random samples since the respondents are only those who use the Internet. Such sampling weakens generalizability of the study findings, and survey participants do not have the opportunity to ask clarifying questions.

The relationship between fear and university student age is weak; however, this remains an issue for further study. Also, more than 80% of those surveyed were women meaning additional research should be based on more equal representation of gender status and include study across academic disciplines for comparison purposes.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of the original authors of “The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation” (Daniel Kwasi Ahorsu, Chung-Ying Lin, Vida Imani, Mohsen Saffari, Mark D. Griffiths and Amir H. Pakpour). Also, Drs. Toby and Mort Mower are acknowledged for their generous support of the Ben Gurion University of the Negev–Regional Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research (RADAR) Center.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahorsu, D. K., Lin, C. Y., Imani, V., Saffari, M., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. Retrieved from. 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Atkeson, A. (2020). What will be the economic impact of COVID-19 in the US? Rough estimates of disease scenarios (No. w26867). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Baker, S. R., Farrokhnia, R. A., Meyer, S., Pagel, M., & Yannelis, C. (2020). How does household spending respond to an epidemic? Consumption during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic (No. w26949). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JFW, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KKW, Chu H, Yang J, Tsoi HW. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea, S., Merchant, R. M., & Lurie, N. (2020). The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine. Retrieved from. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Howell AN, Carleton RN, Horswill SC, Parkerson HA, Weeks JW, Asmundson GJ. Intolerance of uncertainty moderates the relations among religiosity and motives for religion, depression, and social evaluation fears. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2019;75(1):95–115. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins University (JHU) (2020). COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE). Retrieved from: https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6.

- Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: a review and update. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine. 2015;29(3):19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakpour, A. H., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). The fear of CoVId-19 and its role in preventive behaviors. Journal of Concurrent Disorders Retrieved from http://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/39561/1/1313636_Griffiths.pdf.

- Reznik, A., Gritsenko, V., Konstantinov, V., Khamenka, N., & Isralowitz, R. (2020). COVID-19 fear in Eastern Europe: validation of the fear of COVID-19 scale. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. Retrieved from. 10.1007/s11469-020-00283-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Slaven M, Shaw E, Chow E, Smith PA, Wolt A. The effect of medical cannabis on alcohol and tobacco use in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Journal of Pain Management. 2017;10(4):407–413. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin, M. Y., Kasyanov, E. D., Rukavishnikov, G. V., Makarevich, O. V., Neznanov, N. G., Lutova, N. B., & Mazo, G. E. (2020). Structure of anxiety associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in the Russian-speaking sample: results from on-line survey. medRxiv. Retrieved from. 10.1101/2020.04.28.20074302.

- Tikhomirov DA. Features of religiousness of Moscow students. Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes. 2017;3:177–191. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, W. (2020). The coronavirus pandemic is pushing America into a mental health crisis. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/05/04/mental-health-coronavirus/.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2020). Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/.

- Zabaev I, Mikhaylova Y, Oreshina D. Neither public nor private religion: the Russian Orthodox Church in the public sphere of contemporary Russia. Journal of Contemporary Religion. 2018;33(1):17–38. doi: 10.1080/13537903.2018.1408260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zogg, B. (2020). Europe’s Outlier: Belarus and COVID-19. Retrieved from https://isnblog.ethz.ch/politics/europes-outlier-belarus-and-covid-19.