Abstract

Background:

The adult mammalian heart has limited regenerative capacity, mostly due to postnatal cardiomyocyte (CM) cell cycle arrest. In the last two decades, numerous studies have explored CM cell cycle regulatory mechanisms to enhance myocardial regeneration post myocardial infarction (MI). Pyruvate kinase muscle isozyme 2 (Pkm2) is an isoenzyme of the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase. The role of Pkm2 in CM proliferation, heart development and cardiac regeneration is unknown.

Methods:

We investigated the effect of Pkm2 in CM through models of loss (CM-specific Pkm2 deletion during cardiac development) or gain using CM-specific Pkm2 modified mRNA (CMSPkm2 modRNA) to evaluate Pkm2 function and regenerative affects post-acute or -chronic MI in mice.

Results:

Here, we identify Pkm2 as an important regulator of the CM cell cycle. We show that Pkm2 is expressed in CMs during development and immediately after birth but not during adulthood. Loss of function studies show that CM-specific Pkm2 deletion during cardiac development resulted in significantly reduced CM cell cycle, CM numbers and myocardial size. In addition, using CMSPkm2 modRNA, our novel CM-targeted strategy, following acute or chronic MI resulted in increased CM cell division, enhanced cardiac function and improved long-term survival. We mechanistically show that Pkm2 regulates the CM cell cycle and reduces oxidative stress damage through anabolic pathways and β-catenin.

Conclusions:

We demonstrate that Pkm2 is an important intrinsic regulator of the CM cell cycle and oxidative stress and highlight its therapeutic potential using CMSPkm2 modRNA as a gene delivery platform.

Keywords: cardiomyocytes proliferation, anabolic metabolism, cardiac regeneration

INTRODUCTION

The mammalian heart has a short window of regenerative capacity immediately after birth via CM cell division 1; however, this capacity is lost one week after birth 1. Recent studies showed that Hippo 2-5 or NRG1-ERBB2-ERBB4 6, 7 pathways activate β-catenin, which induces CM cell division. In parallel, other recent work demonstrated that increased oxidative stress in the early postnatal window is associated with a shift from glycolytic to oxidative metabolism and plays pivotal roles in CM cell cycle arrest. Importantly, inhibition of oxidative stress in postnatal CMs leads to reduce oxidative DNA damage and curtailed cell cycle arrest 8-10. To date, however, it is unclear whether these seemingly unrelated nodal CM cell division pathways are interlinked. Therefore, we set out to identify an upstream regulator of both β-catenin and oxidative stress pathways in CMs. We hypothesized that glycolytic enzymes involved in regulating oxidative stress and β-catenin may act as nodal regulators of the CM cell cycle. Of these 18 glycolytic enzymes, only one is known to interact with β-catenin. The dimer form of the glycolytic enzyme Pyruvate Kinase Muscle Isozyme M2 (Pkm2) has been extensively studied in cancer cells 11-15. We know dimer Pkm2 directly interacts with β-catenin in prostate cancer cells 13 and promotes metabolic flux into the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), activation of which results in less oxidative DNA damage in a cervical cancer cell line 15. Accordingly, we hypothesized that Pkm2 may play a central role in CM cell division during development and immediately after birth and could also be a therapeutically effective target to enhance myocardial regeneration. Pkm2 and its alternatively splicing mRNA Pkm1 are both produced by the PKM gene 11, 16. Pkm2 and Pkm1 modulate the conversion of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) to pyruvate and Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) 17-20. Pkm1 is active and expressed in adult tissues, like muscle and brain, that consistently need high levels of energy 21, 22 while Pkm2 is expressed in most cell types at varying levels 19, 23. Pkm2, which is enzymatically slower than Pkm1, reduces pyruvate kinase activity and promotes the alternate anabolic glycolytic pathway, i.e. the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), which prevents oxidative stress 14, 24-26. To date, Pkm2 studies in cardiac development during adulthood and after injury are limited but suggest that Pkm2 may be induced in adult CMs under stress conditions 27-30. The role of Pkm2 in CM cell cycle regulation remains unknown.

In this paper, we examine the role of Pkm2 in CMs during normal embryonic and postnatal development as well as following injury. Using gain and loss of function models, we demonstrate that Pkm2 activates two separate and synergistic enzymatic and non-enzymatic pathways in CMs to induce the CM cell cycle and cardiac regeneration post injury.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Data sharing statement.

All modified mRNA (modRNA) vectors containing any genes of interest in this paper will be made available to investigators. My institution and I will adhere to the NIH Grants Policy on Sharing of Unique Research Resources including the “Sharing of Biomedical Research Resources: Principles and Guidelines for Recipients of NIH Grants and Contracts” issued in December 1999. http://ott.od.nih.gov/NewPages/Rtguide_final.html. Specifically, material transfers would be made with no more restrictive terms than in the Simple Letter Agreement or the UBMTA and without reach through requirements. Should any intellectual property arise which requires a patent, we would ensure that the technology remains widely available to the research community in accordance with the NIH Principles and Guidelines document 66.

Methods and Materials.

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will be been made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure that been presented in this manuscript.

Mice.

All animal procedures were performed under protocols approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). CFW or Rosa26mTmG mice strains, male and female, were used. Different modRNAs (100 or 150 μg/heart) were injected directly into the myocardium during open chest surgery. 3 to 8 animals were used for each experiment. For long-term survival, (8-10-week-old) CFW mice treated with CMSLuc or CMSPkm2 modRNAs (n=10) post MI induction were allowed to recover for 6 months in the animal facility. Deaths were monitored and documented. Tamoxifen-inducible CM-restricted deletion of Pkm2 (CMSKO-Pkm2) was generated by crossing Pkm2flox/flox (purchased from Jackson Laboratories (B6;129S-Pkmtm1.1Mgvh/J)) to Tnnt2MerCreMer/+ mice (made by Dr. Chen-Leng Cai, a co-author on this manuscript). Tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in sesame oil at 10 mg/ml as stock solution. To induce Cre nuclear translocation, tamoxifen was administered to mice by intraperitoneal (IP) injection for two consecutive days (E9-E10) (24h interval between administrations) at 0.05 mg/g body weight/day for embryonic stages. The tissues were harvested on E18 for analysis. Mouse husbandry was carried out according to the protocol approved by the IACUC at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Oligonucleotide sequences for genotyping these mouse lines: Tnnt2-F-AGGAACATGAAATCCAGGGTGGCT, Tnnt2-R-GTTCAGCATCCAACAAGGCACTGA; Pkm2-F-CCTTCAGGAAGACAGCCAAG, Pkm2-R – AGTGCTGCCTGGAATCCTCT.

modRNA synthesis.

ModRNAs were transcribed in vitro from plasmid templates (see complete list of open reading frame sequences used to make modRNA in Table S1). Using a customized ribonucleotide blend of anti-reverse cap analog, 3 ´-O-Me-m7G(5’)ppp(5’)G (6 mM, TriLink Biotechnologies), guanosine triphosphate (1.5 mM, Life Technology), adenosine triphosphate (7.5 mM, Life Technology), cytidine triphosphate (7.5 mM, Life Technology) and N1-Methylpseudouridine-5’-Triphosphate (7.5 mM, TriLink Biotechnologies) as described previously in our recent protocol paper 31. mRNA was purified using the Megaclear kit (Life Technology) and treated with antarctic phosphatase (New England Biolabs), followed by re-purification using the Megaclear kit. mRNA was quantitated by Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific), precipitated with ethanol and ammonium acetate and resuspended in 10 mM TrisHCl, 1 mM EDTA.

modRNA transfection.

In vivo modRNA transfection was done, as described previously in our recent method paper 32, using sucrose citrate buffer containing 20μl of sucrose in nuclease-free water (0.3g/ml) and 20μl of citrate (0.1M pH=7; Sigma) mixed with 20μl of different modRNA concentrations in saline to a total volume of 60μl. The transfection mixture was directly injected (3 individual injections, 20μl each) into the myocardium. For in vitro transfection, we used RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer’s recommendations.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical significance was determined by Unpaired two-tailed t-test, One-way ANOVA, Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test, One-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc test or Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test for survival curves, as detailed in respective figure legends. p-Value<0.05 was considered significant. All graphs represent average values, and values were reported as mean ± standard error of the mean. Unpaired two-tailed t-test was based on assumed normal distributions. To quantify the number of CD31 luminal structures, we used WGA, OHG, CD45, CD3 or positive TUNEL, BrdU, ki67, pH3 or Aurora B CMs, with results acquired from at least 3 heart sections/heart, in numbers of mice as mentioned in respective figure legends.

Detailed methods are available in Supplemental Information.

RESULTS

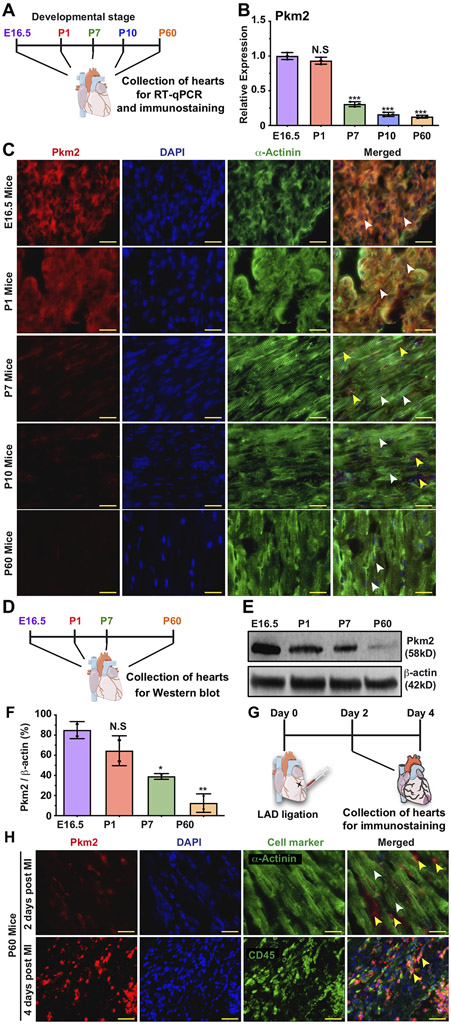

First, we evaluated Pkm splice variants (Pkm2 and Pkm1) for their expression during cardiac development, adulthood and post-injury (Figure 1, Figure S1&2). Figure S1 shows that embryonic hearts uniquely express both Pkm2 and Pkm1 in high amounts, as compared to embryonic kidneys or lungs, organs known to express high levels of Pkm2 20, 27. Both CMs and non-CMs express Pkm2 (Figure 1C, please see complete list of antibodies used in this study in Table S2), though its expression levels significantly decline in P7 (Figure 1A-F). In adulthood, however, Pkm2 expression in adult CMs is very low (Figure 1). We demonstrate, in agreement with previous studies 28, 30, that after ischemic injury (e.g. MI), Pkm2 expression rises moderately in CMs (1.8-fold increase, p≤0.05) and, importantly, significantly in non-CMs, including leucocytes (7-fold, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure S2C and Figure 1G&H, please see complete list of primer sequences for qPCR used in this study in Table S3).

Figure 1. Pkm2 expression in CMs during different stages of heart development and post MI.

A. Experimental timeline for Pkm2 qRT-PCR and immunostaining with Pkm2 and α-Actinin (CM marker) at different stages of mouse heart development. B. Relative expression of Pkm2 measured by qRT-PCR in mice hearts (E16.5, P1, P7, P10 or P60, n=3). C. Representative images of Pkm2 expression at different stages of mouse heart development. D. Experimental plan for Pkm2 western blot analysis at different stages of mouse heart development. E. Western blot Pkm2. F. Quantitative analysis of e (n=2). G. Experimental plan for immunostaining Pkm2 and α-Actinin or CD45 (leukocyte marker) at different time points post MI. H. Representative images of Pkm2 expression at different time points post MI. White arrowheads point to CMs. Yellow arrowheads point to non-CMs. One-way ANOVA, Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test for B&F. ***, P<0.001, **, P<0.01, *, P<0.05, N.S, Not Significant. Scale bar = 25μm.

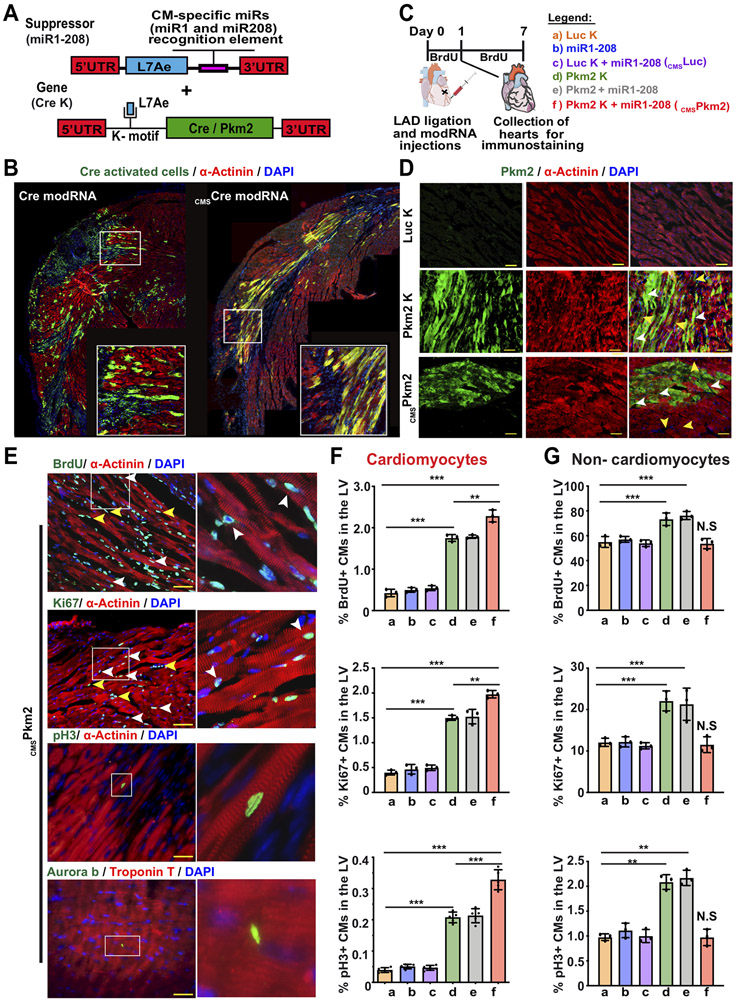

Next, we wanted to determine if restoring Pkm2 levels in postnatal CMs can induce their cell cycle in vitro and post MI. For Pkm2 upregulation in CMs, we used our previously described modified mRNA (modRNA) technology that enables highly efficient, transient, local, non-immunogenic gene delivery to cardiac cells, including CMs, in vitro and in vivo 31-34. We used Luciferase (Luc) modRNA as a control gene for Pkm2 modRNA because they are similarly sized (~1.6Kb) and Luc has no biological function in mice. Pkm2 delivery with modRNA technology might also boost Pkm2 expression in non-CMs, thereby increasing their cellular division and possibly promoting undesired effects, such as elevation in fibrosis and immune response, or preventing CM cell division after MI 35. In order to avoid these effects and to test Pkm2’s ability to boost CMs’ cell cycle and cardiac regenerative capacity, we developed a unique circuit modRNA, termed the (cmsmodRNA) system, which leads to CM-specific modRNA delivery. This system is based on two distinct modRNA constructs (Figure 2 A&B and Figure S3&4). The first contains L7Ae, an archaeal ribosomal protein that regulates the translation of genes containing a kink-turn motif (K-motif), a specific binding site for L7Ae 36, 37. L7Ae protein suppresses translation of the designed modRNA gene of interest by binding to the K-motif upstream of the modRNA sequence when the two constructs are co-transfected into the cell. We achieved CM specificity by adding a CM-specific microRNA recognition element to the 3’UTR of the L7Ae gene. We prevented L7Ae translation in CMs that abundantly and mostly exclusively express those miRs, thereby allowing the gene of interest modRNA to translate strictly in CMs (Figure 2 A&B and Figure S3&4). Since a number of groups have shown that miR1-1 (miR-1)38 and miR-208a (miR-208) 39 are expressed exclusively in CMs, we designed an L7Ae modRNA that contains both miR-1 and miR-208 recognition elements (miR-1-208) and used Pkm2 (Pkm2-K), nuclear GFP (nGFP-K) and Cre recombinase (Cre-K) modRNAs that contain a K-motif. In neonatal CMs in vitro and our mouse MI model in vivo, transfecting Pkm2-K or nGFP-K resulted in translating the gene of interest in both CMs and non-CMs. However, during co-transfection with miR-1-208, the gene of interest was exclusively translated in CMs, i.e. not in non-CMs (e.g. endothelial or smooth muscle cells) (Figure 2B and Figure S5). In vivo, intramyocardial delivery of Cre K modRNA in our MI model using Rosa26 reporter mice (Rosa26mTmG) resulted in GFP expression in CMs and non-CMs covering ~50% of the LV; however, co-transfecting Cre-K with miR-1-208 (CMSCre) labeled only CMs covering ~20% of the LV (Figure 2B-D and Figure S4A&B). In addition, no Cre-Lox recombination could be seen in the spleen, lung or liver following intramyocardial delivery of CMSCre modRNA (Figure S4C). Importantly, as L7Ae is a foreign protein in mice, we thought it might induce an immune response. We therefore evaluated CD45, CD3 or TUNEL expression 7 days post MI in hearts injected with modRNA with or without L7Ae. Our data indicate that L7Ae did not elevate immune cell infiltration or cell death following MI (Figure S6). We hypothesize that because the heart already contains high levels of inflammation and cell death post MI, adding L7Ae did not change these processes.

Figure 2. Transient and exclusive Pkm2 expression in CMs, delivered using CMSPkm2 modRNA, increases cell cycle markers in postnatal CMs.

A. Experimental design to evaluate the CMSmodRNA expression tool using Rosa26mTmG mice, which were transfected with either Cre modRNA alone or CMSCre modRNA immediately post MI. Seven days later, hearts were collected and stained for GFP, α-Actinin and DAPI. B. Representative images of Rosa26mTmG adult mouse heart 7 days post MI and delivery of either Cre modRNA alone or CMSCre modRNA. C. Experimental timeline for evaluating cmsPkm2 modRNA expression (day 1) and effect (day 7) on cell cycle markers (Brdu, Ki67 and pH3) in CMs and non-CMs. D. Representative images of Pkm2 expression in CMs and non-CMs 1 day post MI and delivery of Luc K, Pkm2 K or CMSPkm2 modRNA. E. Representative images of cycle markers (BrdU, Ki67, pH3 and Aurora B) expression in CMs 7 days post MI and delivery of CMSPkm2 modRNA. F&G. Quantification of cell cycle markers in CMs (F) or non-CMs (G) 7 days post MI (n=3). One-way ANOVA, Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test for F&G. ***, P<0.001, **, P<0.01, N.S, Not Significant. Scale bar = 50μm (D) and 25μm (E).

We initially tested Pkm2 modRNA kinetics and its capacity to increase cell cycle markers in CMs, in vitro. We show that Pkm2 modRNA increased protein expression for at least eight days and elevated CM cell cycle marker expression and overall numbers in Pkm2-transfected neonatal rats, in comparison with Luc modRNA controls, three or seven days post transfection, respectively (Figure S7). In vivo, directly injecting Pkm2 modRNA into the myocardium raised Pkm2 levels in CMs and other cardiac cells (Figure S8). Pkm2 pharmacokinetics in vivo lasted eight to 12 days (Figure S9) with markedly more Pkm2 protein in the LV two days after Pkm2 modRNA delivery (Figure S8D). To test Pkm2 modRNA’s effects on the cell cycle in the context of MI, we intramyocardially delivered Luc-K, miR1-208, Luc-K+miR1-208 (CMSLuc), Pkm2-K, Pkm2+miR1-208 or Pkm2-K+miR1-208 (CMSPkm2). Seven days post transfection we measured cell cycle markers in CMs and non-CMs in the LV (Figure 2C). Pkm2-K or Pkm2+miR1-208 modRNA increased cell cycle markers in both CMs and non-CMs more than Luc modRNA (P<0.001, Figure 2E-F). However, CMSPkm2 modRNA only induced ki67- or pH3-positive CMs (P<0.001), with no significant effect on non-CM cell cycle markers. Live imaging of neonatal

CMs showed CM cell division after co-transfection with CMSPkm2 modRNA and CMSnGFP modRNA but not CMSLuc modRNA CMSnGFP modRNA (Movie S1). Further, Pkm2’s effect on cell cycle markers was very prominent in the injected area post MI but subtler in both the injected areas of non-infarcted hearts and remote, uninjured areas (Figure S9).

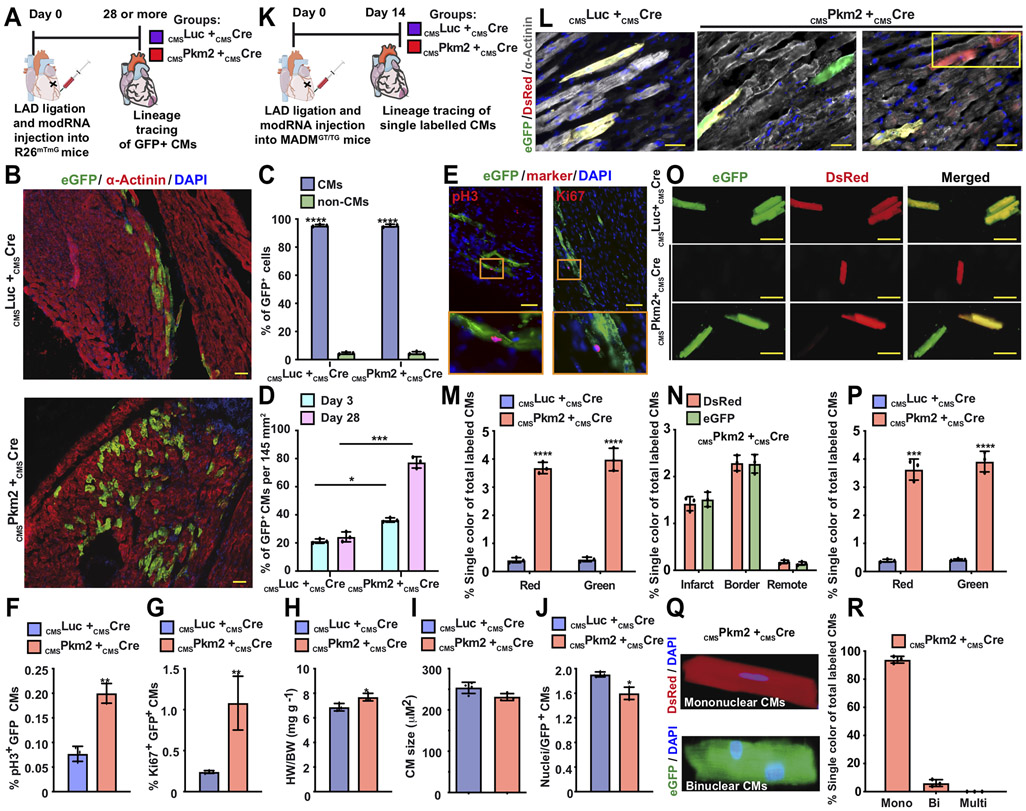

To evaluate if Pkm2’s enhancing effects on cell cycle marker expression can lead to successful CM cell division post MI, we used a lineage-tracing model that combines CMSmodRNAs and a Rosa26mTmG mouse model, mixing CMSPkm2 or CMSLuc with CMSCre modRNA to generate permanently GFP-labeled CMs (Figure 3A-J). We traced the fate and properties of transfected CMs and their progeny over time (including after either CMSPkm2 or CMSLuc modRNAs was no longer expressed). The number of labeled CMs with CMSPkm2 + CMSCre modRNAs was significantly higher than control CMSLuc + CMSCre modRNAs three and 28 days after MI (Figure 3D). This suggests that CMSPkm2 modRNA induces cell division in preexisting CMs and mimics the intrinsic regeneration process observed in mice one day after birth 1. Importantly, 28 days after CMSPkm2 + CMSCre modRNAs treatment, GFP+ CMs showed elevated expression of cell cycle markers such as pH3 and Ki67 (Figure 3E-G), long after Pkm2 was no longer expressed. Heart weight to body weight ratio was significantly increased (Figure 3H), while both GFP+ CMs size (Figure 3I) and nuclei numbers/cell (Figure 3J) were smaller in mice treated with CMSPkm2 + CMSCre modRNAs compared to control.

Figure 3. Lineage tracing models show that transient Pkm2 expression increase CM cell division and suppress postnatal CM cell-cycle arrest.

A. Experimental timeline used for cardiac lineage tracing in R26mTmG mice B. Representative images of transfected CMs and their progeny (GFP+, α-Actinin+) 28 days post MI. C. Quantification of GFP+ CMs 3 or 28 days post MI (n=3). D. Transfection efficiency (%GFP+) of CMs or non-CMs 28 days post MI (n=3). E. Representative images of GFP+ CMs, pH3+ or Ki67+ 28 days post MI. F&G. Quantification of GFP+ pH3+ (F. n=3) or GFP+ Ki67+ CMs (G. n=3) 28 days post transfection with CMSLuc or CMSPkm2 with CMSCre modRNA in MI model. H-J. Ratio of heart to body weight (H. n=3), relative cross-sectional area of GFP+ CMs (I. n=3) and number of nuclei in GFP+ CMs (J. n=3) in hearts 28 days post MI and delivery of CMSPkm2 in cardiac lineage tracing model using R26mTmG mice. K. Experimental timeline to trace proliferating CMs using MADM mice L. Representative images of single-color- (Green (eGFP+/DsRed−), Red (eGFP−/DsRed+)) or double-color- (Yellow (eGFP+/DsRed+) labeled CMs 14 days post MI and injection of CMSLuc or cmsPkm2 with CMSCre modRNA in a MADM MI mouse model. M. Quantification of single-color CMs (Red or Green) amongst total labeled CMs 14 days post MI (n=5). N. Distribution of single-color CMs in the heart 14 days post MI (n=3, infarct, border or remote area). O. Representative images of isolated CMs from MADM mice 14 days post MI and modRNA injection. P. Quantification of isolated single-color CMs 14 days post MI (n=3). Q&R. Representative image (Q) and quantification (R, n=3, mono, bi or multi) of single-color CM nucleation 14 days post MI. Unpaired two-tailed t-test or Two-way ANOVA to analyze the data in C&D. ****, P<0.0001, ***, P<0.001, **, P<0.01, *, P<0.05, N.S, Not Significant. Scale bar = 50μm (B&L) or 5μm to E&O.

Because higher CM numbers can be a result of improved CM survival and to rigorously assess CM division in vivo, we used a second lineage-tracing model based on Cre-recombinase-dependent mosaic analysis with double markers (MADM) mice. As previously shown 40, 41, this system validates successful CM cell division by evaluating single-color CMs among total labeled CMs. Similar to our strategy in the Rosa26mTmG lineage-tracing model, either CMSPkm2 or CMSLuc modRNAs were intramyocardially delivered into heterozygous MADM-ML-11GT/TG mice. Fourteen days post MI and modRNA delivery, we collected hearts and determined the single-color percentage of total labeled CMs. CMSPkm2 + CMSCre modRNAs significantly increased (P ≤ 0.0001) the single-color percentage of total labeled CMs, mostly in the border zone and infarct, 14 days post MI in comparison with control CMSLuc + CMSCre modRNAs (Figure 3K-R). In addition, 14 days post MI and CMSPkm2 + CMSCre modRNA delivery, isolated adult CMs show notably higher (P ≤ 0.001) single-color percentage of total labeled CMs, mostly mononuclear, in comparison with control (Figure 3M&P). We also used our cardiac MADM model in chronic MI, injecting modRNA 15 days after MI. Our results (Figure S10) indicate, similar to the acute MI data, that CMSPkm2 + CMSCre modRNA markedly raises (P ≤ 0.001) the single-color percentage of total labeled CMs in the heart, in comparison with control. Thus, using two independent CM cell division lineage-tracing models, we conclusively show that Pkm2 activates CM cell division in vivo. Note that our CMSmodRNA platform allowed us to employ two separate CM cell division lineage-tracing models without needing to cross with CM-specific Cre-expressing mice, so that our approach facilitates faster and less expansive analysis of CM cell division in vivo.

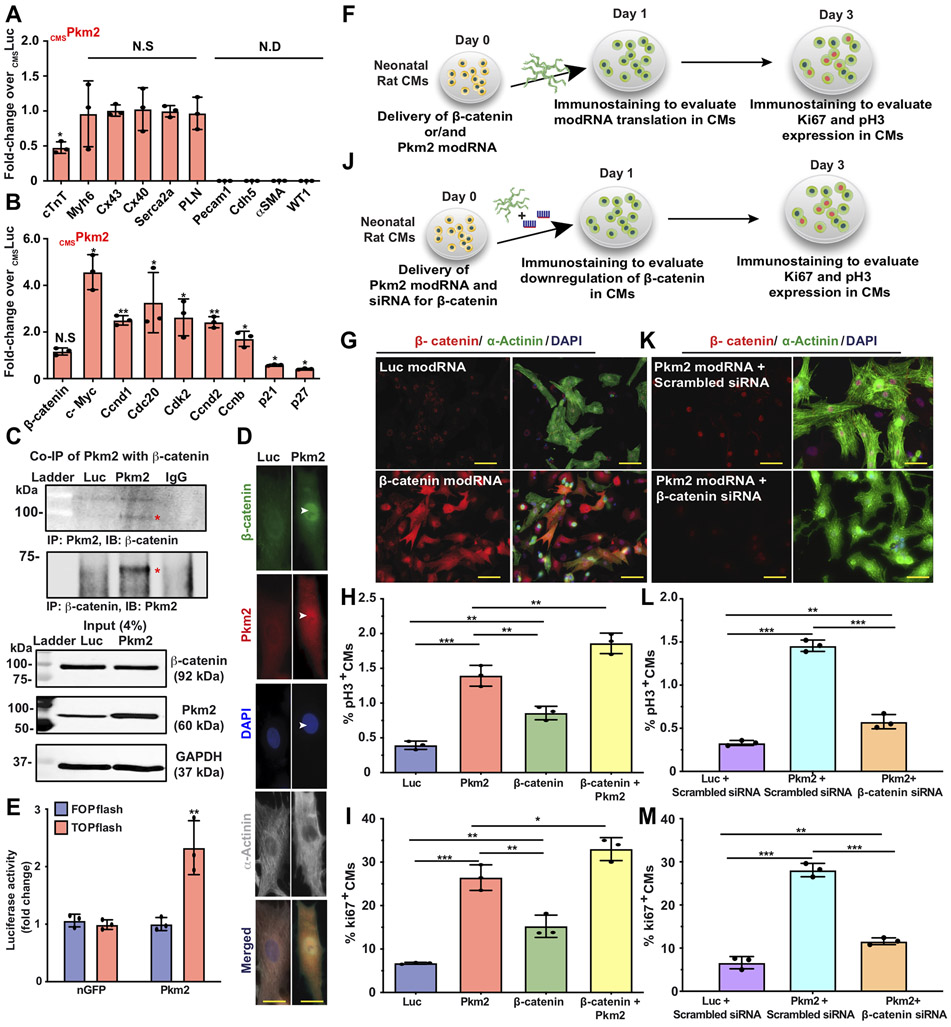

Based on its a) expression during development but not after birth, b) ability to induce postnatal CM cell division post MI and c) known role controlling both β-catenin and anabolic pathways in cancer cells, we wanted to investigate Pkm2’s ability to increase β-catenin and anabolic pathway activity in postnatal CMs after MI. More specifically, we evaluated the gene expression of Pkm2 transfected postnatal CMs after MI. Because adult CMs are challenging to FACS sort due to CM size and rapid cell death after isolation, we used magnetic beads to sort transfected adult CMs. For this process, we designed a CM-specific inactive human CD25 (CMSihCD25) modRNA based on truncated human CD25 (the only extracellular domain of the human IL2 receptor) that can be expressed on the surface of transfected adult CMs without compromising their cell activity (due to lack of intracellular domain), thereby allowing us to distinguish them from non-transfected CMs. In this way, we were able to use anti-hCD25 magnetic beads, which are not cross-reactive with mouse CD25, to sort transfected adult CMs (Figure S11) and evaluate their gene expression using qRT-PCR. Two days after MI and intramyocardial delivery of either CMSPkm2 or CMSLuc together with CMSihCD25 modRNAs, we measured changes in gene expression. Our results showed that isolated cells were enriched for CM markers with significantly lower Troponin T expression but little to no change in Myh6 expression, cardiac gap junction channels (Cx43 and Cx40) or genes associated with CM contractility (Serca2a and PLN, Figure 4A). Importantly, adult CMs expressing Pkm2 had elevated β-catenin downstream targets Cyclin D1 and c-Myc (Figure 4B) and cell cycle-promoting genes (Cdc20, Cdk2 and Ccnd2, Ccnb1) but fewer cell cycle inhibitors (p21 and p27) compared to control (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Pkm2 directly interacts with β-catenin, upregulates its downstream targets (Cyclin D1 and C-Myc) and increases expression of cell-cycle-promoting genes and cell cycle markers in postnatal CMs.

A&B. 2 days post MI and administration of cmsLuc or cmsPkm2 modRNAs with cmsihCD25, adult CMs were isolated using magnetic beads (please see method in Suppl. Fig. 13). A. qRT-PCR analysis to validate purity of isolated CMs, CM-specific markers and functional cardiac genes (n=3). B. Gene expression comparisons of β-catenin downstream target genes and expression of cell-cycle-promoting genes or cell-cycle inhibitors post cmsLuc or cmsPkm2 modRNA delivery into adult CMs (n=3). C. Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and input control to evaluate Pkm2’s direct interaction with β-catenin in P3 rat neonatal CMs post Luc or Pkm2 modRNA transfection (n=2). D. Immunostaining of rat neonatal CM after Luc or Pkm2 modRNA delivery shows co-localized β-catenin and Pkm2 in the CM nucleus. E. Stabilizing β-catenin induced its interaction with TCF/LEF transcription factors in the nucleus, which in turn induced the expression of target genes (e.g cyclin D1. c-Myc) that can be measured by TOPflash (Luciferase reporter with TCF binding DNA sequence). Fopflash has mutant TCF binding DNA sequence (Fopflash), used as control. Quantitative TOPflash or Fopflash following delivery of nGFP (control) or Pkm2 modRNA (n=3). F. Experimental plan for evaluating overexpression of β-catenin alone or with Pkm2 modRNA and studying its effect on the expression of cell cycle genes in P3 neonatal rat CMs. G. Representative images of β-catenin expression 1 day post Luc or β-catenin modRNA transfection in vitro (co-stained α-Actinin and DAPI). H&I. Quantification of cell cycle markers (Ki67, pH3) in neonatal rat CMs 3 days after transfection of Luc, Pkm2 or β-catenin modRNA alone or combined Pkm2 and β-catenin modRNAs (n=3). J. Experimental timeline used to evaluate the role of β-catenin in CMs post Pkm2 modRNA delivery. K. Representative images of β-catenin inhibition by siRNA in CMs after Pkm2 modRNA delivery. L&M. Quantification of cell cycle markers (Ki67, pH3) in neonatal rat CMs 3 days after transfection with Luc or Pkm2 modRNA with scrambled siRNA or Pkm2 modRNA with siRNA for β -catenin (n=3). One-way ANOVA, Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test for A&B, H&I, L&M. Unpaired two-tailed t-test for E. ***, P<0.001, **, P<0.01, *, P<0.05, N.S, Not Significant. Scale bar = 10μm (D) and 25μm (G&K).

Having shown that Pkm2 overexpression increases cell cycle markers and β-catenin downstream signaling, and because Pkm2 has been shown to interact directly with β-catenin in prostate cancer cells, we performed a co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay (Figure 4C), which revealed that Pkm2 directly interacts with β-catenin in CMs. We also showed β-catenin and Pkm2 co-localization in the CM nuclei (Figure 4D). In addition, we performed a TOPFlash luciferase assay to track β-catenin/TCF activity and demonstrated that Pkm2 modRNA increased β-catenin activation in neonatal rat CMs in vitro (Figure 4E).

To better understand the β-catenin pathway’s role in the Pkm2-induced CM cell cycle, we made β-catenin modRNA and transfected it, alone or with Pkm2, into neonatal rat CMs in vitro. Our results reveal significantly elevated cell cycle markers in CMs three days after delivery of each gene alone, in comparison with Luc modRNA; however, Pkm2 modRNA generated significantly (P ≤ 0.001) higher cell marker expression in CMs than β-catenin (Figure 4F-I), thereby suggesting that the β-catenin pathway is not the only pathway Pkm2 uses to promote CM cell division. Also, we show that adding Pkm2 modRNA to β-catenin increased cell cycle marker expression in CMs, indicating a synergistic effect between the two genes (Figure 4H&I). To further decipher the role of β-catenin in the Pkm2-induced CM cell cycle, we transfected rat neonatal CMs with Pkm2 modRNA concomitantly with β-catenin knockdown (Figure 4J-M). Our results show the β-catenin pathway is important for inducing cell cycle marker expression in CMs (Figure 4L&M). Yet even without β-catenin, Pkm2 raises cell cycle marker expression in CMs, in comparison with control, again suggesting a parallel pathway that increases CM cell division and is independent from the β-catenin pathway (Figure 4L&M).

As Pkm2 plays a role in activating the anabolic pathway PPP by elevating G6pd, the rate-limiting enzyme of PPP, in a human lung cancer cell line 42, we wanted to discover if Pkm2 overexpression in CMs upregulates G6pd and thus alters anabolic metabolism. To investigate this, we transfected neonatal rat CMs with Luc or Pkm2 modRNA and collected the cells two days later (Figure S12A). Western blot analysis showed increased G6pd after Pkm2 modRNA in comparison with control. (Figure S12B&C). In addition, we used 13C isotopic tracers to investigate metabolic flux by adding 13C glucose to the media of neonatal rat CMs six hours after Pkm2 or Luc modRNA delivery and collecting samples to test glycolysis (after 10 minutes), TCA cycle (two hours) or PPP (18 hours). Our results show elevated PPP and increased ribonucleotide synthesis; the latter has previously been shown to be important for inducing cell division, as ribonucleotides are the building blocks of nucleic acid needed to DNA synthesis 43 (Figure S12D).

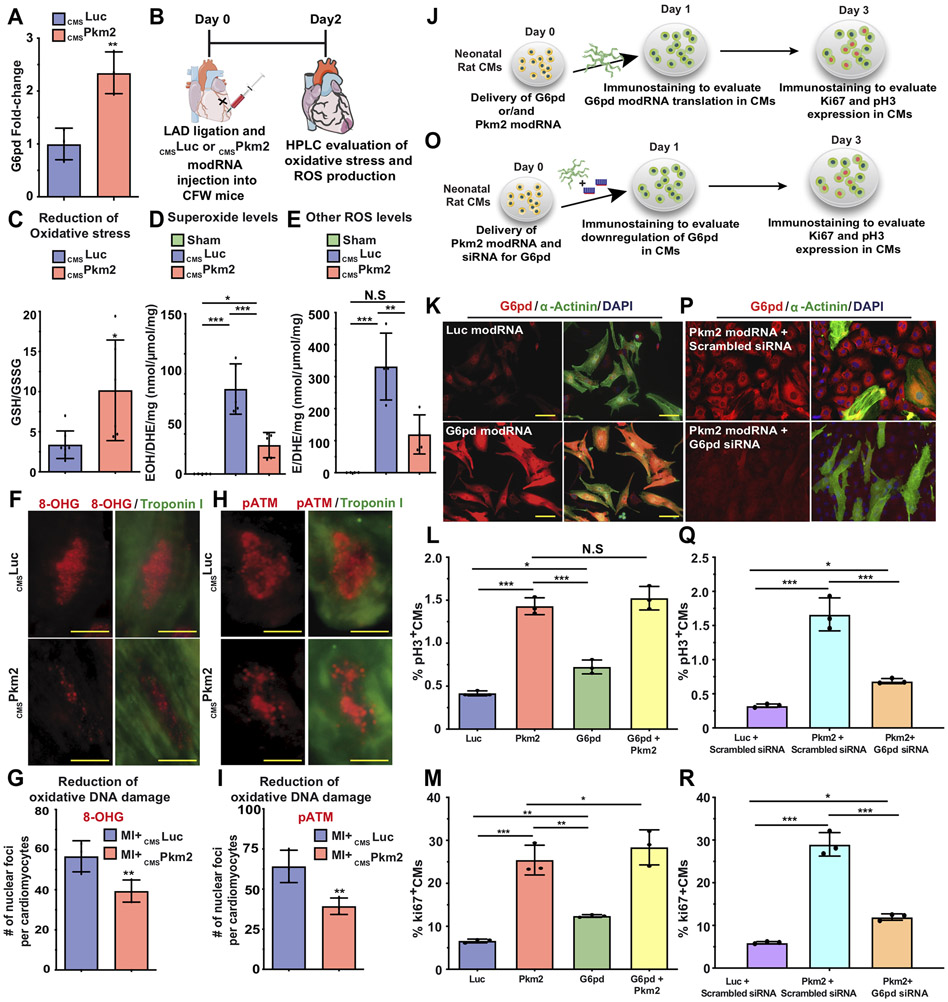

Since the oxidative branch of the PPP is a major source of NADPH, we investigated whether Pkm2 overexpression to CMs increases NADPH production. Indeed, our results show that Pkm2 modRNA raises NADPH production and reduces the NADP/NADPH ratio (Figure S12E). As PPP activation is associated with reduced oxidative stress, ROS production and oxidative DNA damage, we explored how intramyocardial delivery of CMSLuc or CMSPkm2 modRNA influenced these processes and elevated G6pd post MI (Figure 5). Two days after MI, we transfected CMs with either Pkm2 or Luc and showed the firPkm2-transfected CMs have higher G6pd expression (Figure 5A, isolation method described in Figure S11). HPLC measurements of oxidative stress (GSH/GSSG ratio, Figure 5B&C), superoxide and other ROS (Figure 5D&E) as well as immunostaining of 8-OHG (Figure 5F&G) or pATM (Figure 5H&I) all show less oxidative stress, ROS production and oxidative DNA damage two days post MI and intramyocardial delivery of CMSPkm2, in comparison with control.

Figure 5. Pkm2 upregulates the anabolic enzyme G6pd, which reduces oxidative stress, ROS production and oxidative damage and leads to increased expression of cell cycle markers in postnatal CMs.

A. qPCR comparisons of G6pd expression 2 days post MI and administration of cmsLuc or cmsPkm2 modRNAs with cmsihCD25, when adult CMs were isolated using magnetic beads (please see method in Suppl. Fig. 13). B. Experimental timeline used to evaluate reduced oxidative stress or ROS production post MI and delivery of cmsLuc or cmsPkm2 modRNA. C. HPLC quantification of GSH/GSSG ratio (n=6). D&E. HPLC quantification of superoxide probe dihydroethidium (DHE) in 2-hydroxyethidium (D. n=5, EOH) or ethidium (E. n=4, E) 2 days post MI and cmsLuc or cmsPkm2 modRNA injection or sham operation. F. Representative images of 8-OHG foci frequency in CMs 2 days post MI and transfection with either CMSLuc or CMSPkm2 modRNA (co-stained α-Actinin and DAPI). G. Quantitative analysis of F (n=3). H. Representative images of pATM foci frequency in CMs 2 days post MI and transfection with CMSLuc or CMSPkm2 modRNA. I. Quantitative analysis of H (n=3). J. Experimental plan for evaluating overexpression of G6pd alone or with Pkm2 modRNA and studying its effect on the expression of cell cycle genes in P3 neonatal rat CMs. K. Representative images of G6pd expression 1 day post Luc or G6pd modRNAs transfection in vitro (co-stained α-Actinin and DAPI). L&M. Quantification of cell cycle markers (Ki67, pH3) in neonatal rat CMs 3 days after transfection of Luc, Pkm2 or G6pd modRNA alone or combined Pkm2 and G6pd modRNAs (n=3). O. Experimental timeline used to evaluate the role of G6pd in CMs post Pkm2 modRNA delivery. P. Representative images of G6pd inhibition by siRNA in CMs post Pkm2 modRNA delivery. Q&R. Quantification of cell cycle markers (Ki67, pH3) in neonatal rat CMs 3 days after transfection with Luc or Pkm2 modRNA with scrambled siRNA or Pkm2 modRNA with siRNA for G6pd (n=3). One-way ANOVA, Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test for L&M, Q&R. Unpaired two-tailed t-test for A, C-E, G and I. ***, P<0.001, **, P<0.01, *, P<0.05, N.S, Not Significant. Scale bar = 5μm (D) and 25μm (G&K).

To evaluate G6pd and the role of anabolic pathway activation in the CM cell cycle, we made G6pd modRNA and transfected it, alone or with Pkm2, into neonatal rat CMs in vitro. Our results reveal significantly more cell cycle markers in CMs three days after delivery of each gene alone, in comparison with Luc modRNA; however, Pkm2 modRNA generated significantly (P ≤ 0.01) higher expression of cell cycle markers in CMs than did G6pd (Figure 5J-M), thereby suggesting, similar to our β-catenin results (Figure 5H&I), that the G6pd pathway is not the only pathway that Pkm2 enhances to promote the CM cell cycle. Also, we show that adding Pkm2 modRNA to G6pd increased expression of the cell cycle marker Ki67 in CMs, indicating a possible synergistic effect between the two genes (Figure 5M). To further decipher the role of G6pd in Pkm2-induced cell division in CMs, we transfected rat neonatal CMs with Pkm2 modRNA concomitantly with G6pd knockdown (Figure 5O-R). Our results indicate that G6pd and the anabolic pathway PPP are important for inducing cell cycle marker expression in CMs (Figure 5Q&R). Yet even with less G6pd, Pkm2 increased cell cycle marker expression in CMs as compared to control, suggesting again another pathway, parallel to but independent from β-catenin, that increases CM cell division (Figure 5Q&R). In sum, and as Figure 5 illustrates, we were able to show that Pkm2’s anabolic enzymatic activity in CMs changes glucose flux and raises anabolic PPP. Upregulating the PPP reduces oxidative stress, ROS production and oxidative DNA damage, which in turn increase CM cell division.

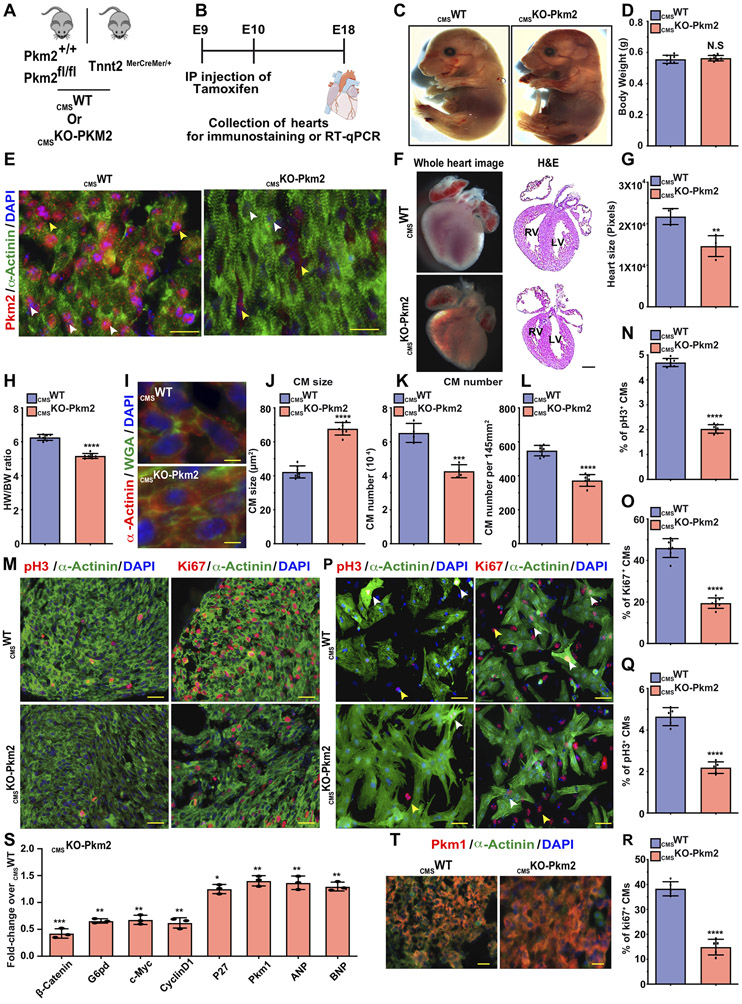

Our data suggest that Pkm2 has at least two independent mechanisms of action that may influence CM cell division: one is the enzymatic anabolic pathway (G6pd and PPP) and the other is the non-enzymatic β-catenin pathway. As both pathways are important for CM cell division and because Pkm2 is highly expressed during development but not in adulthood, we wanted to evaluate its role in embryonic CM cell division and cardiac development. We generated inducible CM-specific Pkm2 knockout (CMSKO-Pkm2, Figure 6A) mice. We crossed either Pkm2fl/fl or Pkm2+/+ with Tnnt2MerCreMer/+ mice to generate either CMSKO-Pkm2 or CMSWT mice, respectively. Both CMSKO-Pkm2 and CMSWT mice received tamoxifen injections at E9 and E10 to flox out Pkm2 during cardiac development in CMSKO-Pkm2 mice (Figure 6B). Because most CMSKO-Pkm2 mice (>95%) died immediately after birth, we collected and evaluated hearts at E18. The E18 CMSKO-Pkm2 and CMSWT mice were similar in size (Figure 6C&D). As expected, no Pkm2 expression was seen in CMs from CMSKO-Pkm2 hearts (Figure 6E); additionally, we observed significantly smaller hearts with thinner ventricular walls compared to control CMSWT hearts (Figure 6F&G). The heart weight/body weight ratio was ~17% lower in CMSKO-Pkm2 mice than in CMSWT mice (Figure 6H). Wheat agglutinin (WGA) staining showed that CMs from CMSKO-Pkm2 hearts were ~36% larger (Figure 6I&J), were ~25% fewer in number (Figure 6K&L) and showed ~54% less expression of cell cycle markers (Fig. 6M-O) in comparison with CMs from CMSWT hearts. Moreover, in vitro CMs isolated from E18 CMSKO-Pkm2 hearts showed ~59% lower expression of cell cycle markers than CMs isolated from E18 CMSWT hearts (Fig. 6P-R). Gene expression comparison between CMSKO-Pkm2 hearts and CMSWT hearts shows that lack of Pkm2 in CMs during development results in significantly lower Pkm2 downstream targets β-catenin, G6pd, c-Myc and Ccnd1 (Figure 6S). Yet, cell cycle inhibitor (P27), cardiac hypertrophy markers ANP and BNP, Pkm1 mRNA and protein are all upregulated (Figure 6S&T). We also tested if Pkm2 modRNA can rescue and restore cell cycle marker expression in CMs. Accordingly, we isolated CMs from CMSKO-Pkm2 and transfected them with Luc or Pkm2 modRNA. Three days post transfection with Pkm2 modRNA, CMSKO-Pkm2 CM showed significantly (P ≤ 0.001) elevated cell cycle markers in comparison to Luc modRNA (Figure S13). Taken together, our data suggest that Pkm2 expression in CMs is required for CM cell division and proper heart development.

Figure 6. Loss of function study of Pkm2 expression in CMs during heart development reduces heart size, increases CM size, lowers total CM number and limits CM cell division capacity.

A. Experimental plan for generating inducible CMSWT (Pkm2+/+, (B6129SF2/J) littermates expressing Cre exclusively in CMs) or CMSKO-Pkm2 mice. B. Experimental timeline for evaluating the effect of CMSKO-Pkm2 on CM cell division and heart development. C. Representative images of E18 CMSWT or CMSKO-Pkm2 mice and evaluation of body weight (D. n=7). E. Representative images of Pkm2 and α-Actinin immunostaining as well as whole heart H&E staining F. Evaluation of heart size (G. n=4) and heart weight to body weight ratio (H. n=7) of E18 CMSWT or CMSKO-Pkm2. Representative images of WGA (I.) and quantification thereof (J. n=7). Quantification of CM numbers isolated from heart (K. n=4) or counted per section (L. n=7) in E18 CMSWT or CMSKO-Pkm2 mice. M. Representative images of pH3+ or Ki67+ CMs in E18 CMSWT or CMSKO-Pkm2 hearts. Quantification of pH3+ (N. n=7) or ki67+ (O. n=7) CMs in E18 CMSWT or CMSKO-Pkm2 hearts. P. Representative images of pH3- or Ki67-positive CMs in isolated CMs from E18 CMSWT or CMSKO-Pkm2 hearts. Quantification of pH3+ (Q. n=5) or ki67+ (R. n=5) CMs isolated from E18 CMSWT or CMSKO-Pkm2 hearts. S. Relative gene expression measured by qRT-PCR comparing E18 CMSWT or CMSKO-Pkm2 hearts (n=3). T. Representative images of Pkm1 expression in E18 CMSWT or CMSKO-Pkm2 hearts. White arrowheads point to CMs. Yellow arrowheads point to non-CMs. Unpaired two-tailed t-test for (D, G, H, J-L, N, O, Q, R and S). ****, P<0.0001, ***, P<0.001, **, P<0.01, *, P<0.05, N.S, Not Significant. Scale bar = 25μm (E and T), 5μm (I), 50μm (M&P).

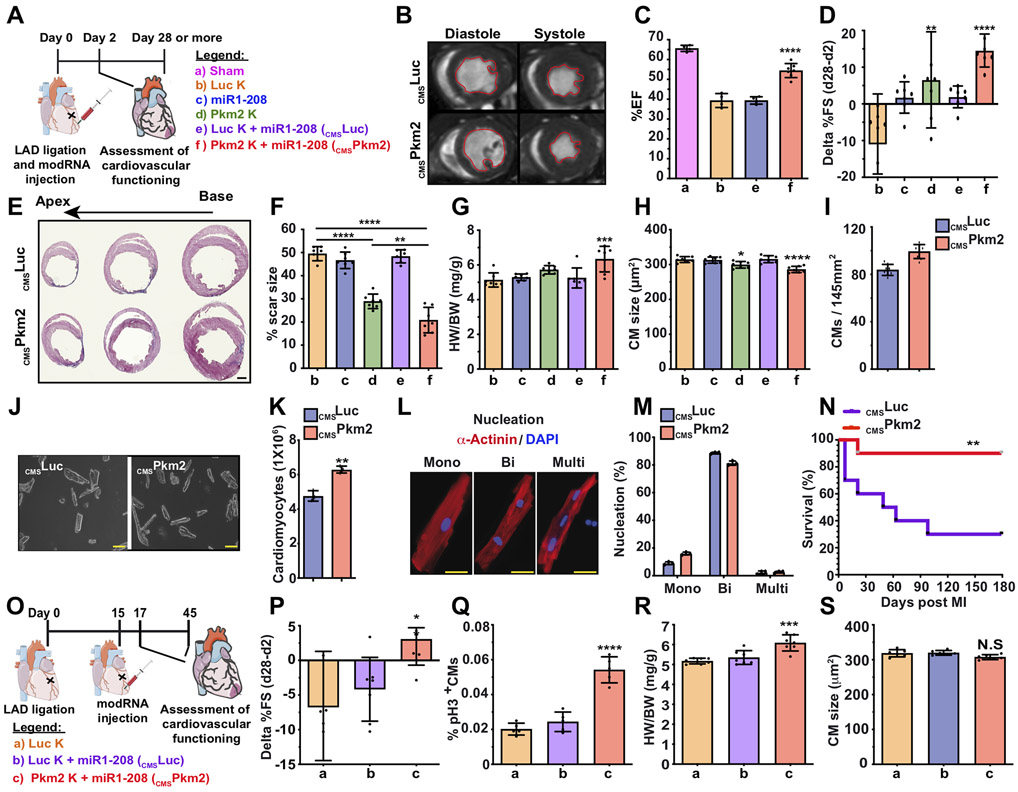

As Pkm2 may promote CM survival after transplantation 29, and based on the totality of our data, we propose that CMSPkm2 modRNA may prevent cardiac remodeling and improve heart function post MI. We used our double-blind, long-term mouse MI model and tested the effect of CMSPkm2 modRNA 28 days post MI (Figure 7A). MRI and echo studies revealed that CMSPkm2 significantly increased the ejection fraction percentage (Figure 7B&C and Movies S2&S3), and the percentage fractioning delta shortened between day 2 (baseline, Figure S14A&B) and day 28 post MI (Figure 7D). While left ventricular internal diameter end systole (LVIDs) showed little change, the left ventricular internal diameter end diastole (LVIDd) was much larger in CMSPkm2 mice than in controls 28 days post MI (Figure S14C&D). Further, 28 days post MI, Pkm2 or CMSPkm2 expression significantly increased left ventricular end diastolic or systolic posterior wall thickness (Figure S14E&F) and reduced cardiac scar formation (Figure 7E&F, for baseline sham please see Figure 14SG). CMSPkm2 intramyocardial delivery did not cause any abnormality (e.g. angioma, edema) in cardiac tissue (Figure 7E&F). Note that CMSPkm2 produced smaller scars than Pkm2 modRNA, indicating that delivering Pkm2 delivery exclusively to CMs has superior beneficial effects. CMSPkm2 also produced notably higher heart weight to body weight ratios with smaller CMs and increased capillary density compared to control (Figure 7G&H and Figure S14H-J). Further, CMSPkm2 significantly raised CM numbers in the heart without elevating the number of nuclei per CM and increased the mononuclear fraction compared to control (Figure 7J-M). Importantly, mice treated with CMSPkm2 modRNAs immediately after MI had significantly better long-term survival than those treated with CMSLuc control (Fig. 7N). We next used our chronic MI mouse model to evaluate CMSPkm2 modRNA’s ability to reverse cardiac remodeling. In this model, we delivered modRNA intramyocardially 15 days post MI and then tracked ongoing cardiac remodeling (Figure 7O). Our results show significantly improved cardiac function (Figure 7P), increased expression of the CM cell cycle marker pH3 (Figure 7Q) and higher heart weight to body weight ratios (Figure 7R), with no significant change in CM size (Figure 7S). Taken together, our data reveal that CMSPkm2 modRNA has clear therapeutic effects on CMs: it induces the CM cell cycle during cardiac development and after chronic or acute MI, increases angiogenesis, extends CM survival and reduces both CM apoptosis and oxidative stress to prevent or reverse cardiac remodeling post MI (Figure S15).

Figure 7. Gain of function study of Pkm2 expression in CMs improves cardiac function and outcome after acute or chronic MI.

A. Experimental timeline to evaluate cardiac function and outcome in an acute MI mouse model. B. MRI assessments of left ventricular systolic function 1 month post MI. Images depict left ventricular chamber (outlined in red) in diastole and systole. C. Percentage of ejection fraction for the experiments in B. (a, n=3; b, n=4; e, n=4; f, n=7). D. Echo evaluation of delta in percentage of fractioning shorting differences between day 2 (baseline) and day 28 post MI (n=7). E. Representative masson trichrome staining to evaluate scar size 28 days post MI. F-I. Quantification of scar size (F. n=7), heart weight to body weight ratio (G. n=7), CM size (H. n=7) and CM numbers per section (I. n=8) measured 28 days post MI. Representative images of CM numbers isolated from heart after treatments with CMSLuc or CMSPkm2 28 days post MI. (J.) and quantification of the experiment in J. (K. n=3). L. Representative images of nuclei of isolated CMs (mono, bi or multi). M. Quantification of the experiment in L. (n=3). N. Long-term post-MI survival curve for mice injected with cmsLuc or cmsPkm2 modRNAs (n=10). O. Experimental timeline to evaluate cardiac function and outcome in a chronic MI mouse model. P. Echo evaluation of delta in percentage of fractioning shorting differences between day 17 (baseline) and day 45 post MI (n=7). Q-S. Quantification of pH3+ CMs in the heart (Q. n=5), heart weight to body weight ratio (R. n=7) or CM size (S. n=7) in the heart with different treatments 45 days post MI. White arrowheads point to CMs. Yellow arrowheads point to non-CMs. One-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc test for (C&D, F-I and P-S), Unpaired two-tailed t-test for (J, K and M), Mantel-Cox log-rank test (N). ****, P<0.0001, ***, P<0.001, **, P<0.01, *, P<0.05, N.S, Not Significant. Scale bar = 1mm (E), 50μm (K), 10μm (L).

DISCUSSION

Reactivating CM proliferation is crucial to successful cardiac regeneration. Both newts and zebrafish have high levels of cardiac regeneration via activation of endogenous CM cell division 44-47. Also, in fetal mice and pigs, induction of CM cell division leads to cardiac regeneration 48-50. Studies in vitro and in vivo have shown that after injury, adult mammalian CMs can divide, an ability that can be stimulated by upregulating pro-proliferative genes 2, 3, 6, 7, 48, 49, 51-57. Other studies have shown that reactivating adult CMs cell cycle re-entry is possible via proteins 6, 56, 58 or viruses 59-61 and in transgenic mouse models of pro-proliferative genes 2, 5, 7, 51, 53, 54, 62. Using proteins to induce the cell cycle is challenging due to their very short half-life, the difficulty of local administration, the lack of CM specificity and their inability to deliver intranuclear genes, such as transcription factors. The cardiac-specific adeno-associated virus (cmsAAV) vector, while not immunogenic and relatively safe, has a very long, sustained expression time that may lead to uncontrolled increases in CM size as well as cardiac hypertrophy and arrhythmia 53. Although transgenic mice can be used as a model to study genes specifically in CMs, in transient or permanent conditions, this method is not clinically relevant for gene delivery 54. The challenges posed by these current approaches emphasize the need for a safe, local, transient, efficient and controlled method to deliver genes exclusively to CMs.

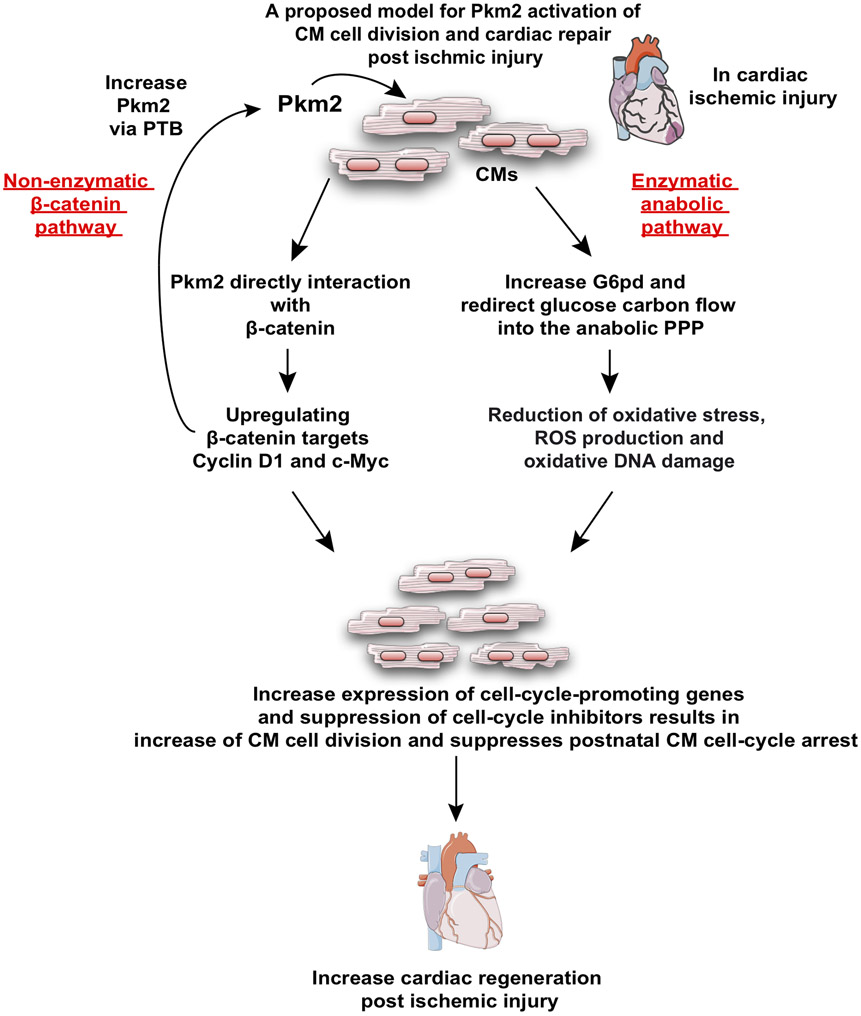

In the current report, we demonstrate that Pkm2, which functions upstream of two nodal CM cell cycle regulatory pathways, is necessary and sufficient for inducing the CM cell cycle. On one hand, Pkm2 has a non-enzymatic function that directly interacts with β-catenin in CM nuclei, inducing β-catenin and upregulating its downstream targets Cyclin D1 and C-Myc (Figure 4). On the other hand, Pkm2 has an enzymatic function that elevatess G6pd and redirects glucose carbon flow into the PPP anabolic pathway (Figure S12). PPP elevation results in decreased ROS production and oxidative DNA damage that suppresses postnatal CM cell-cycle arrest (Figure 5). Identifying a single gene (Pkm2) that governs both pivotal pathways in CMs may uncover a potential therapeutic approach for inducing CM cell division and regenerating the injured myocardium.

Overall, and as may be inferred from other cardiac studies 28-30, our data suggest that endogenous Pkm2 upregulation in CMs in response to ischemic injury is very limited in the adult heart and is insufficient to induce meaningful CM proliferation. Here we show that ectopic Pkm2 gene expression specifically in CMs promotes both their cell division and cardiac regeneration. Importantly, we show (Figure S16) that previously identified CM proliferation pathways, including β-catenin, caERBB2 and Yap, may induce Pkm2 expression in neonatal CMs. Moreover, we show that Pkm2 is positively regulated by the β-catenin c-Myc, but not Cyclin D1. More specifically, we show that polypyrimidine tract binding protein-1 (PTB), which is a target of c-Myc 63, induces Pkm2 expression. These results suggest there is a positive feedback loop between Pkm2 and c-Myc that contributes to the CM cell cycle and cardiac regeneration. Moreover, our findings link the known CM cell cycle pathways (NRG1-ERBB signaling, Hippo-YAP signaling, hypoxia and reduced ROS production) as NRG1-ERBB and Hippo-YAP signaling upregulate Pkm2 and thereby reduce ROS production in CM and increase their cell cycle (Figure S16 and Figure 8).

Figure 8. A proposed model for Pkm2 enzymatic (via G6pd) and non-enzymatic (via β-catenin) mechanisms of action that promote CM cell division, suppress postnatal CM cell-cycle arrest and increase cardiac regeneration post ischemic injury.

Our newly designed CM-specific delivery platform (Figure 2) overcomes cell-targeting challenges and opens up new therapeutic opportunities for cardiac disease and regeneration. CM-specific delivery using AAV is limited due to its long-term gene expression (up to 11 months), which can have detrimental effects on cardiac regeneration 54, 64. Recently, Gabisonia et al. showed that cardiac AAV6-miR-199a in infarcted pigs stimulated CM cell division, but uncontrolled, long-term expression of this pro-proliferative gene eventually resulted in cardiac arrhythmia that led to sudden cardiac death 64. By contrast, modRNA is a transient (expression lasts for 8-12 days), controlled, dose dependent gene delivery method. Thus far, however, modRNA delivery has only been used for upregulating in vivo paracrine factors such as VEGF-A 33, IGF1 65 and mutated human FSTL1 66 to propagate cardiac vascularization, protection or regeneration, respectively. Since these factors act by binding to their cognate receptors on the cell surface, they are good candidates to study in a non-cell-specific system. Our newly designed system facilitates CMSmodRNA gene delivery for both intracellular and intranuclear genes of interest. By developing CM-specific modRNA, we enable multiple platforms for the cardiovascular field. We were also able to introduce new lineage-tracing models using MADM mice (MADM-ML-11GT/TG) and our CM-specific delivery of Cre (Figure 3), which is much faster and more cost effective than a previously proposed MADM model 40 and may be used by others to evaluate the roles of different genes of interest in inducing CM cell division in vivo. In this way, our current project is a proof of principle study showing that short burst of CM proliferation either immediately or two weeks post MI may induce cardiac regeneration in a mouse model (Figure 7 and Figure S14). Future work should seek further development of CM-targeted modRNA delivery for clinical applications to induce CM cell cycle and cardiac regeneration.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective:

What Is New?

We developed novel therapeutic cardiomyocyte-specific modRNA that allows transient expression of any gene of interest exclusively in cardiomyocytes.

We established that Pkm2 expression is downregulated during mammalian heart development, which coincides with the mammalian heart regeneration window.

We identified Pkm2 as a previously unknown inducer of cardiomyocyte proliferation in vitro and in vivo.

We demonstrated that Pkm2 interacts with β-catenin and activates both G6pd and the pentose phosphate pathway to provide nucleotides for DNA synthesis and reduce oxidative stress post-myocardial infarction (MI).

We showed that cardiomyocyte-specific Pkm2 modRNA expression induces cardiac regeneration post-MI.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

The cardiomyocyte-specific modRNA expression platform can be used for gene delivery in clinical applications to treat heart diseases.

The identification of Pkm2, a previously unrecognized inducer of cardiomyocyte proliferation and inhibitor of oxidative stress in the heart post MI, shows the gene regulates multiple processes and has a pleiotropic beneficial effect on the heart after MI.

Our cardiomyocyte-specific modRNA expression platform will enable the development of a new class of therapeutics for different diseases beyond cardiology. The gene can be delivered therapeutically to specific cells or organs undergoing disease states.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge Nishat Sultana, Yoav Hadas, Jason Kondrat and Lu Zhang for their help with this manuscript.

FUNDING SOURCES

This work was funded by a cardiology start-up grant awarded to the Zangi laboratory and also by NIH grant R01 HL142768-01. A.M.S. is supported by the British Heart Foundation.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Pkm

Pyruvate kinase muscle

- CM

cardiomyocyte

- modRNA

modified mRNA

- LV

Left ventricle

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- LAD

Left anterior descending artery

- Luc

Luciferase

- LVID

Left ventricular internal diameter

- EF

Ejection fraction

- FS

Fractional Shortening

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

L.Z. and A.M. are inventors of a Utility Patent Application (Cell-specific expression of modrna, WO2018053414A1), which covers the results in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Porrello ER, Mahmoud AI, Simpson E, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Olson EN and Sadek HA. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science. 2011;331:1078–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heallen T, Zhang M, Wang J, Bonilla-Claudio M, Klysik E, Johnson RL and Martin JF. Hippo pathway inhibits Wnt signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science. 2011;332:458–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin Z, von Gise A, Zhou P, Gu F, Ma Q, Jiang J, Yau AL, Buck JN, Gouin KA, van Gorp PR, Zhou B, Chen J, Seidman JG, Wang DZ and Pu WT. Cardiac-specific YAP activation improves cardiac function and survival in an experimental murine MI model. Circ Res. 2014;115:354–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morikawa Y, Heallen T, Leach J, Xiao Y and Martin JF. Dystrophin-glycoprotein complex sequesters Yap to inhibit cardiomyocyte proliferation. Nature. 2017;547:227–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xin M, Kim Y, Sutherland LB, Murakami M, Qi X, McAnally J, Porrello ER, Mahmoud AI, Tan W, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Sadek HA, Bassel-Duby R and Olson EN. Hippo pathway effector Yap promotes cardiac regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13839–13844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bersell K, Arab S, Haring B and Kuhn B. Neuregulin1/ErbB4 signaling induces cardiomyocyte proliferation and repair of heart injury. Cell. 2009;138:257–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Uva G, Aharonov A, Lauriola M, Kain D, Yahalom-Ronen Y, Carvalho S, Weisinger K, Bassat E, Rajchman D, Yifa O, Lysenko M, Konfino T, Hegesh J, Brenner O, Neeman M, Yarden Y, Leor J, Sarig R, Harvey RP and Tzahor E. ERBB2 triggers mammalian heart regeneration by promoting cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:627–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakada Y, Canseco DC, Thet S, Abdisalaam S, Asaithamby A, Santos CX, Shah AM, Zhang H, Faber JE, Kinter MT, Szweda LI, Xing C, Hu Z, Deberardinis RJ, Schiattarella G, Hill JA, Oz O, Lu Z, Zhang CC, Kimura W and Sadek HA. Hypoxia induces heart regeneration in adult mice. Nature. 2017;541:222–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puente BN, Kimura W, Muralidhar SA, Moon J, Amatruda JF, Phelps KL, Grinsfelder D, Rothermel BA, Chen R, Garcia JA, Santos CX, Thet S, Mori E, Kinter MT, Rindler PM, Zacchigna S, Mukherjee S, Chen DJ, Mahmoud AI, Giacca M, Rabinovitch PS, Aroumougame A, Shah AM, Szweda LI and Sadek HA. The oxygen-rich postnatal environment induces cardiomyocyte cell-cycle arrest through DNA damage response. Cell. 2014;157:565–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura W, Xiao F, Canseco DC, Muralidhar S, Thet S, Zhang HM, Abderrahman Y, Chen R, Garcia JA, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Ashour AM, Asaithamby A, Liang H, Xing C, Lu Z, Zhang CC and Sadek HA. Hypoxia fate mapping identifies cycling cardiomyocytes in the adult heart. Nature. 2015;523:226–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong N, De Melo J and Tang D. PKM2, a Central Point of Regulation in Cancer Metabolism. Int J Cell Biol. 2013;2013:242513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu S and Le H. Dual roles of PKM2 in cancer metabolism. Acta biochimica et biophysica Sinica. 2013;45:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang W, Xia Y, Ji H, Zheng Y, Liang J, Huang W, Gao X, Aldape K and Lu Z. Nuclear PKM2 regulates beta-catenin transactivation upon EGFR activation. Nature. 2011;480:118–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Feng G, Bao G, Xu G, Sun Y, Li W, Wang L, Chen J, Jin H and Cui Z. Nuclear translocation of PKM2 modulates astrocyte proliferation via p27 and -catenin pathway after spinal cord injury. Cell cycle. 2015;14:2609–2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar B and Bamezai RN. Moderate DNA damage promotes metabolic flux into PPP via PKM2 Y-105 phosphorylation: a feature that favours cancer cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2015;42:1317–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noguchi T, Inoue H and Tanaka T. The M1- and M2-type isozymes of rat pyruvate kinase are produced from the same gene by alternative RNA splicing. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13807–13812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong G, Mao Q, Xia W, Xu Y, Wang J, Xu L and Jiang F. PKM2 and cancer: The function of PKM2 beyond glycolysis. Oncology letters. 2016;11:1980–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riganti C, Gazzano E, Polimeni M, Aldieri E and Ghigo D. The pentose phosphate pathway: an antioxidant defense and a crossroad in tumor cell fate. Free radic biol med. 2012;53:421–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Israelsen WJ, Dayton TL, Davidson SM, Fiske BP, Hosios AM, Bellinger G, Li J, Yu Y, Sasaki M, Horner JW, Burga LN, Xie J, Jurczak MJ, DePinho RA, Clish CB, Jacks T, Kibbey RG, Wulf GM, Di Vizio D, Mills GB, Cantley LC and Vander Heiden MG. PKM2 isoform-specific deletion reveals a differential requirement for pyruvate kinase in tumor cells. Cell. 2013;155:397–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Israelsen WJ and Vander Heiden MG. Pyruvate kinase: Function, regulation and role in cancer. Semin cell dev biol. 2015;43:43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaneton B and Gottlieb E. Rocking cell metabolism: revised functions of the key glycolytic regulator PKM2 in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munoz ME and Ponce E. Pyruvate kinase: current status of regulatory and functional properties. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;135:197–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng X, Boyer L, Jin M, Mertens J, Kim Y, Ma L, Ma L, Hamm M, Gage FH and Hunter T. Metabolic reprogramming during neuronal differentiation from aerobic glycolysis to neuronal oxidative phosphorylation. eLife. 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo W and Semenza GL. Pyruvate kinase M2 regulates glucose metabolism by functioning as a coactivator for hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2011;2:551–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazurek S Pyruvate kinase type M2: a key regulator of the metabolic budget system in tumor cells. Int J biochem cell biol. 2011;43:969–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC and Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dayton TL, Gocheva V, Miller KM, Israelsen WJ, Bhutkar A, Clish CB, Davidson SM, Luengo A, Bronson RT, Jacks T and Vander Heiden MG. Germline loss of PKM2 promotes metabolic distress and hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes & development. 2016;30:1020–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rees ML, Subramaniam J, Li Y, Hamilton DJ, Frazier OH and Taegtmeyer H. A PKM2 signature in the failing heart. Biochem biophys res commun. 2015;459:430–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi J, Yang X, Yang D, Li Y and Liu Y. Pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2 expression correlates with survival of cardiomyocytes after allogeneic rat heterotopic heart transplantation. Pathol Res Pract. 2015;211:12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams AL, Khadka V, Tang M, Avelar A, Schunke KJ, Menor M and Shohet RV. HIF1 mediates a switch in pyruvate kinase isoforms after myocardial infarction. Physiol genom. 2018;50:479–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kondrat J, Sultana N and Zangi L. Synthesis of Modified mRNA for Myocardial Delivery. Methods mol biol. 2017;1521:127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sultana N, Magadum A, Hadas Y, Kondrat J, Singh N, Youssef E, Calderon D, Chepurko E, Dubois N, Hajjar RJ and Zangi L. Optimizing Cardiac Delivery of Modified mRNA. Mol ther. 2017;25:1306–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zangi L, Lui KO, von Gise A, Ma Q, Ebina W, Ptaszek LM, Spater D, Xu H, Tabebordbar M, Gorbatov R, Sena B, Nahrendorf M, Briscoe DM, Li RA, Wagers AJ, Rossi DJ, Pu WT and Chien KR. Modified mRNA directs the fate of heart progenitor cells and induces vascular regeneration after myocardial infarction. Nature biotechnology. 2013;31:898–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zangi L, Oliveira MS, Ye LY, Ma Q, Sultana N, Hadas Y, Chepurko E, Spater D, Zhou B, Chew WL, Ebina W, Abrial M, Wang QD, Pu WT and Chien KR. Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Receptor-Dependent Pathway Drives Epicardial Adipose Tissue Formation After Myocardial Injury. Circulation. 2017;135:59–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ieda M, Tsuchihashi T, Ivey KN, Ross RS, Hong TT, Shaw RM and Srivastava D. Cardiac fibroblasts regulate myocardial proliferation through beta1 integrin signaling. Dev Cell. 2009;16:233–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamma T and Ferre-D’Amare AR. Structure of protein L7Ae bound to a K-turn derived from an archaeal box H/ACA sRNA at 1.8 A resolution. Structure. 2004;12:893–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wroblewska L, Kitada T, Endo K, Siciliano V, Stillo B, Saito H and Weiss R. Mammalian synthetic circuits with RNA binding proteins for RNA-only delivery. Nat biotech. 2015;33:839–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao Y, Samal E and Srivastava D. Serum response factor regulates a muscle-specific microRNA that targets Hand2 during cardiogenesis. Nature. 2005;436:214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams AH, Liu N, van Rooij E and Olson EN. MicroRNA control of muscle development and disease. Curr opinion cell biol. 2009;21:461–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali SR, Hippenmeyer S, Saadat LV, Luo L, Weissman IL and Ardehali R. Existing cardiomyocytes generate cardiomyocytes at a low rate after birth in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:8850–8855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohamed TMA, Ang YS, Radzinsky E, Zhou P, Huang Y, Elfenbein A, Foley A, Magnitsky S and Srivastava D. Regulation of Cell Cycle to Stimulate Adult Cardiomyocyte Proliferation and Cardiac Regeneration. Cell. 2018;173:104–116 e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salani B, Ravera S, Amaro A, Salis A, Passalacqua M, Millo E, Damonte G, Marini C, Pfeffer U, Sambuceti G, Cordera R and Maggi D. IGF1 regulates PKM2 function through Akt phosphorylation. Cell cycle. 2015;14:1559–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fairbanks LD, Bofill M, Ruckemann K and Simmonds HA. Importance of ribonucleotide availability to proliferating T-lymphocytes from healthy humans. Disproportionate expansion of pyrimidine pools and contrasting effects of de novo synthesis inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29682–29689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bader D and Oberpriller JO. Repair and reorganization of minced cardiac muscle in the adult newt (Notophthalmus viridescens). J morphol. 1978;155:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Major RJ and Poss KD. Zebrafish Heart Regeneration as a Model for Cardiac Tissue Repair. Drug discov today Dis models. 2007;4:219–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poss KD, Wilson LG and Keating MT. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Science. 2002;298:2188–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh BN, Koyano-Nakagawa N, Garry JP and Weaver CV. Heart of newt: a recipe for regeneration. J cardiovasc transl res. 2010;3:397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leone M, Magadum A and Engel FB. Cardiomyocyte proliferation in cardiac development and regeneration: a guide to methodologies and interpretations. Am J physiol Heart circ physiol. 2015;309:H1237–H1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heo JS and Lee JC. beta-Catenin mediates cyclic strain-stimulated cardiomyogenesis in mouse embryonic stem cells through ROS-dependent and integrin-mediated PI3K/Akt pathways. J cell biochem. 2011;112:1880–1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu W, Zhang E, Zhao M, Chong Z, Fan C, Tang Y, Hunter JD, Borovjagin AV, Walcott GP, Chen JY, Qin G and Zhang J. Regenerative Potential of Neonatal Porcine Hearts. Circulation. 2018;138:2809–2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beigi F, Schmeckpeper J, Pow-Anpongkul P, Payne JA, Zhang L, Zhang Z, Huang J, Mirotsou M and Dzau VJ. C3orf58, a novel paracrine protein, stimulates cardiomyocyte cell-cycle progression through the PI3K-AKT-CDK7 pathway. Circ Res. 2013;113:372–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Engel FB, Schebesta M, Duong MT, Lu G, Ren S, Madwed JB, Jiang H, Wang Y and Keating MT. p38 MAP kinase inhibition enables proliferation of adult mammalian cardiomyocytes. Genes & development. 2005;19:1175–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee HG, Chen Q, Wolfram JA, Richardson SL, Liner A, Siedlak SL, Zhu X, Ziats NP, Fujioka H, Felsher DW, Castellani RJ, Valencik ML, McDonald JA, Hoit BD, Lesnefsky EJ and Smith MA. Cell cycle re-entry and mitochondrial defects in myc-mediated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and heart failure. PloS one. 2009;4:e7172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liao HS, Kang PM, Nagashima H, Yamasaki N, Usheva A, Ding B, Lorell BH and Izumo S. Cardiac-specific overexpression of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 increases smaller mononuclear cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2001;88:443–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ozhan G and Weidinger G. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in heart regeneration. Cell Regen. 2015;4:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuhn B, del Monte F, Hajjar RJ, Chang YS, Lebeche D, Arab S and Keating MT. Periostin induces proliferation of differentiated cardiomyocytes and promotes cardiac repair. Nat Med. 2007;13:962–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heallen T, Morikawa Y, Leach J, Tao G, Willerson JT, Johnson RL and Martin JF. Hippo signaling impedes adult heart regeneration. Development. 2013;140:4683–4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wei K, Serpooshan V, Hurtado C, Diez-Cunado M, Zhao M, Maruyama S, Zhu W, Fajardo G, Noseda M, Nakamura K, Tian X, Liu Q, Wang A, Matsuura Y, Bushway P, Cai W, Savchenko A, Mahmoudi M, Schneider MD, van den Hoff MJ, Butte MJ, Yang PC, Walsh K, Zhou B, Bernstein D, Mercola M and Ruiz-Lozano P. Epicardial FSTL1 reconstitution regenerates the adult mammalian heart. Nature. 2015;525:479–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ebelt H, Zhang Y, Kohler K, Xu J, Gajawada P, Boettger T, Hollemann T, Muller-Werdan U, Werdan K and Braun T. Directed expression of dominant-negative p73 enables proliferation of cardiomyocytes in mice. J mol cell cardiol. 2008;45:411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Engel FB. Cardiomyocyte proliferation: a platform for mammalian cardiac repair. Cell cycle. 2005;4:1360–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eulalio A, Mano M, Dal Ferro M, Zentilin L, Sinagra G, Zacchigna S and Giacca M. Functional screening identifies miRNAs inducing cardiac regeneration. Nature. 2012;492:376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mahmoud AI, Kocabas F, Muralidhar SA, Kimura W, Koura AS, Thet S, Porrello ER and Sadek HA. Meis1 regulates postnatal cardiomyocyte cell cycle arrest. Nature. 2013;497:249–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang W, Zheng Y, Xia Y, Ji H, Chen X, Guo F, Lyssiotis CA, Aldape K, Cantley LC and Lu Z. ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of PKM2 promotes the Warburg effect. Nat cell biol. 2012;14:1295–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gabisonia K, Prosdocimo G, Aquaro GD, Carlucci L, Zentilin L, Secco I, Ali H, Braga L, Gorgodze N, Bernini F, Burchielli S, Collesi C, Zandona L, Sinagra G, Piacenti M, Zacchigna S, Bussani R, Recchia FA and Giacca M. MicroRNA therapy stimulates uncontrolled cardiac repair after myocardial infarction in pigs. Nature. 2019; 569:418–422. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1191-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang CL, Leblond AL, Turner EC, Kumar AH, Martin K, Whelan D, O’Sullivan DM and Caplice NM. Synthetic chemically modified mrna-based delivery of cytoprotective factor promotes early cardiomyocyte survival post-acute myocardial infarction. Mol pharmaceut. 2015;12:991–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Magadum A, Singh N, Kurian AA, Sharkar MTK, Chepurko E and Zangi L. Ablation of a Single N-Glycosylation Site in Human FSTL 1 Induces Cardiomyocyte Proliferation and Cardiac Regeneration. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2018;13:133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tarnavski O, McMullen JR, Schinke M, Nie Q, Kong S and Izumo S. Mouse cardiac surgery: comprehensive techniques for the generation of mouse models of human diseases and their application for genomic studies. Physiol genom. 2004;16:349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Engel FB, Hauck L, Cardoso MC, Leonhardt H, Dietz R and von Harsdorf R. A mammalian myocardial cell-free system to study cell cycle reentry in terminally differentiated cardiomyocytes. Circ res. 1999;85:294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Magadum A, Ding Y, He L, Kim T, Vasudevarao MD, Long Q, Yang K, Wickramasinghe N, Renikunta HV, Dubois N, Weidinger G, Yang Q and Engel FB. Live cell screening platform identifies PPARdelta as a regulator of cardiomyocyte proliferation and cardiac repair. Cell Res. 2017;27:1002–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gorski PA, Kho C and Oh JG. Measuring Cardiomyocyte Contractility and Calcium Handling In Vitro. Methods mol biol. 2018;1816:93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saupe KW, Spindler M, Tian R and Ingwall JS. Impaired cardiac energetics in mice lacking muscle-specific isoenzymes of creatine kinase. Circ res. 1998;82:898–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Buescher JM, Antoniewicz MR, Boros LG, Burgess SC, Brunengraber H, Clish CB, DeBerardinis RJ, Feron O, Frezza C, Ghesquiere B, Gottlieb E, Hiller K, Jones RG, Kamphorst JJ, Kibbey RG, Kimmelman AC, Locasale JW, Lunt SY, Maddocks OD, Malloy C, Metallo CM, Meuillet EJ, Munger J, Noh K, Rabinowitz JD, Ralser M, Sauer U, Stephanopoulos G, St-Pierre J, Tennant DA, Wittmann C, Vander Heiden MG, Vazquez A, Vousden K, Young JD, Zamboni N and Fendt SM. A roadmap for interpreting (13)C metabolite labeling patterns from cells. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2015;34:189–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goncalves MD, Hwang SK, Pauli C, Murphy CJ, Cheng Z, Hopkins BD, Wu D, Loughran RM, Emerling BM, Zhang G, Fearon DT and Cantley LC. Fenofibrate prevents skeletal muscle loss in mice with lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E743–E752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fernandes DC, Wosniak J Jr., Pescatore LA, Bertoline MA, Liberman M, Laurindo FR and Santos CX. Analysis of DHE-derived oxidation products by HPLC in the assessment of superoxide production and NADPH oxidase activity in vascular systems. Am J physiol Cell physiol. 2007;292:C413–C422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ray PD, Huang BW and Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell Signal. 2012;24:981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.