Abstract

Fusarium chlamydosporum represents a well-defined morpho-species of both phytopathological and clinical importance. Presently, five phylo-species lacking Latin binomials have been resolved in the F. chlamydosporum species complex (FCSC). Naming these phylo-species is complicated due to the lack of type material for F. chlamydosporum. Over the years a number of F. chlamydosporum isolates (which were formerly identified based on morphology only) have been accessioned in the culture collection of the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute. The present study was undertaken to correctly identify these ‘F. chlamydosporum’ isolates based on multilocus phylogenetic inference supported by morphological characteristics. Closer scrutiny of the metadata associated with one of these isolates allowed us to propose a neotype for F. chlamydosporum. Phylogenetic inference revealed the presence of nine phylo-species within the FCSC in this study. Of these, eight could be provided with names supported by subtle morphological characters. In addition, a new species, as F. nodosum, is introduced in the F. sambucinum species complex and F. chlamydosporum var. fuscum is raised to species level, as F. coffeatum, in the F. incarnatum-equiseti species complex (FIESC).

Keywords: chlamydospores, clinical isolates, morphology, mycotoxin, new taxa, systematics

INTRODUCTION

Fusarium chlamydosporum represents a well-defined morpho-species (Gerlach & Nirenberg 1982, Leslie & Summerell 2006, O’Donnell et al. 2009, 2018) of both phytopathological and clinical importance (Leslie & Summerell 2006, O’Donnell et al. 2009). This species is characterised by its difficulty in forming sporodochia (requires exposure to UV-light; Gerlach & Nirenberg 1982), abundant and rapid formation of large chlamydospores, production of 3–5-septate macroconidia (i.e. sporodochial conidia), 0–2-septate microconidia (i.e. aerial conidia) and the production of a bright pink to dark wine-red pigment on various culture media (Wollenweber & Reinking 1925, 1935, Reinking & Wollenweber 1927, Gerlach & Nirenberg 1982, Leslie & Summerell 2006). Wollenweber & Reinking (1925) first introduced this species, isolated from the exterior of the pseudostem of Musa sampientum, collected in Tela, Honduras. They further classified this species as a member of the section Sporotrichiella, which also included F. poae and F. sporotrichioides at that time. Presently, various unnamed phylo-species (FCSC 1–5) and F. nelsonii (O’Donnell et al. 2009, 2018) constitute the F. chlamydosporum species complex (FCSC), sister to the F. aywerte (FASC; Laurence et al. 2016), F. incarnatum-equiseti (FIESC) and F. sambucinum (FSAMSC) species complexes (O’Donnell et al. 2013).

Fusarium chlamydosporum is commonly isolated from soils and grains in arid and semi-arid regions (Burgess & Summerell 1992, Kanaan & Bahkali 1993, Sangalang et al. 1995), and from plant material displaying disease symptoms that include crown rot (Du et al. 2017), blight (Satou et al. 2001), damping-off (Engelbrecht et al. 1983, Lazreg et al. 2013) and stem canker (Fugro 1999). This species has also been implicated in human and animal fusarioses (Kiehn et al. 1985, Martino et al. 1994, Segal et al. 1998, Kluger et al. 2004, Azor et al. 2009, O’Donnell et al. 2009) and together with members of the FIESC, account for approximately 15 % of fusarioses in the USA (O’Donnell et al. 2009). As with most Fusarium spp. associated with human fusarioses (Al-Hatmi et al. 2016), treatment of F. chlamydosporum infection is complicated due to multidrug-resistance, but amphotericin B and posaconazole have been shown to be effective (Pujol et al. 1997, Azor et al. 2009). In addition, several strains of F. chlamydosporum are known to produce the mycotoxins beauvericin, butanolide, moniliformin, trichothecene (Rabie et al. 1978, 1982, Marasas et al. 1984, O’Donnell et al. 2018), other secondary metabolites such as chlamydosporol (Savard et al. 1990), chitinase (Mathivanan et al. 1998), cellulase (Qin et al. 2010), and other unnamed compounds (Soumya et al. 2018, Wang et al. 2018). Recently, Soumya et al. (2018) isolated and characterised the red pigment produced by F. chlamydosporum in culture, and found that this long-chain hydrocarbon with unsaturated groups possess cytotoxicity towards human breast adenocarcinoma cells MCF-7, and could be exploited in cancer therapeutics as well as in the cosmetic industry.

The first critical multilocus phylogenetic study to include a large number of F. chlamydosporum isolates by O’Donnell et al. (2009) revealed four phylo-species (FCSC 1–4) within a group of clinical and environmental isolates initially identified as F. chlamydosporum, one of which included the ex-type of F. nelsonii (as FCSC 4; O’Donnell et al. 2009). Following this study, O’Donnell et al. (2018) identified a fifth phylo-species that was able to produce the mycotoxins beauvericin, butanolide and moniliformin. However, both studies refrained from providing names to the four unnamed phylo-species (FCSC 1–3 & 5) as no type material was available for F. chlamydosporum s. str. to serve as reference point. Over the years, a number of F. chlamydosporum isolates (which were formerly identified based on morphology only) have been accessioned in the culture collection (CBS) of the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute (WI), Utrecht, The Netherlands. However, given the paucity of key informative morphological features of especially Fusarium spp. (Nirenberg 1990, Lombard et al. 2019), the present study was undertaken to correctly identify these ‘F. chlamydosporum’ isolates based on multilocus phylogenetic inference supported by morphological characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates

Fusarium isolates (Table 1), initially identified and treated as F. chlamydosporum, were obtained from the culture collection (CBS) of the WI in Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Table 1.

Details of Fusarium strains included in the phylogenetic analyses.

| Species | Culture accession1 | Host/substrate | Origin | GenBank accession | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cmdA | rpb1 | rpb2 | tef1 | Reference | |||||

| F. acacia-mearnsii | NRRL 26755 = CBS 110255 = MRC 5122 | Acacia mearnsii | South Africa | − | KM361640 | KM361658 | AF212449 | O’Donnell et al. (2000), Aoki et al. (2015) | |

| F. armeniacum | NRRL 6227 = ATCC 36781 = FRC R-5319 = MRC 1783 | Fescue hay | USA | − | JX171446 | JX171560 | HM744692 | O’Donnell et al. (2013), Yli-Mattila et al. (2011) | |

| NRRL 29133 = CBS 485.94 = NRRL 26847 = NRRL 26908 | Unknown | Australia | − | − | HQ154448 | HM744659 | Yli-Mattila et al. (2011) | ||

| NRRL 31970 = FRC R-1957 | Soil | Australia | − | − | HQ154453 | HM744664 | Yli-Mattila et al. (2011) | ||

| NRRL 43641 | Horse eye | USA | GQ505398 | HM347192 | GQ505494 | GQ505430 | O’Donnell et al. (2009, 2010) | ||

| F. asiaticum | NRRL 13818 = CBS 110257 = FRC R-5469 = MRC 1963 = NRRL 31547T | Hordeum vulgare | Japan | − | JX171459 | JX171573 | AF212451 | O’Donnell et al. (2000, 2013) | |

| F. atrovinosum | CBS 445.67 = BBA 10357 = DSM 62169 = IMI 096270 = NRRL 26852 = NRRL 26913T | Triticum aestivum | Australia | MN120693 | MN120713 | − | MN120752 | Present study | |

| CBS 130394 | Human leg | USA | MN120694 | MN120714 | MN120734 | MN120753 | Present study | ||

| NRRL 13444 | Soil | Australia | GQ505373 | JX171454 | GQ505467 | GQ505403 | O’Donnell et al. (2000, 2013) | ||

| NRRL 34013 | Human toenail | USA | GQ505378 | − | GQ505472 | GQ505408 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 34015 | Human eye | USA | GQ505380 | − | GQ505474 | GQ505410 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 34016 | Human leg | USA | GQ505381 | HM347170 | GQ505475 | GQ505411 | O’Donnell et al. (2009, 2010) | ||

| NRRL 34021 | Human lung | USA | GQ505385 | − | GQ505479 | GQ505415 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 34023 | Human finger | USA | GQ505387 | − | GQ505481 | GQ505417 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 43627 | Human bronchial lavage | USA | GQ505392 | − | GQ505487 | GQ505423 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 43630 | Human sputum | USA | GQ505395 | − | GQ505490 | GQ505426 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| F. aywerte | NRRL 25410T | Soil | Australia | KU171417 | JX171513 | JX171626 | KU171717 | O’Donnell et al. (2013), Brown & Proctor (2016) | |

| RBG5743 | Soil | Australia | − | KP083273 | KP083278 | KP083250 | Laurence et al. (2016) | ||

| F. boothii | NRRL 26916 = ATCC 24373 = CBS 316.73 = IMI 160243 = NRRL 26855T | Zea mays | South Africa | − | KM361641 | KM361659 | AF212444 | O’Donnell et al. (2000), Aoki et al. (2015) | |

| F. brachygibbosum | NRRL 34033 | Human foot | USA | GQ505388 | HM347172 | GQ505482 | GQ505418 | O’Donnell et al. (2009, 2010) | |

| F. cerealis | NRRL 25491 = CBS 589.93 | Iris hollandica | Netherlands | − | MG282371 | MG282400 | AF212465 | O’Donnell et al. (2000), Waalwijk et al. (2018) | |

| F. chlamydosporum | CBS 145.25 = NRRL 26912NT | Musa sapientum | Honduras | MN120695 | MN120715 | MN120735 | MN120754 | Present study | |

| CBS 615.87 = NRRL 28578 | Colocasia esculenta | Cuba | GQ505375 | JX171526 | GQ505469 | GQ505405 | O’Donnell et al. (2009, 2013) | ||

| CBS 677.77 = NRRL 36539 | Soil | Solomon Islands | GQ505391 | MN120716 | GQ505486 | GQ505422 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 32521 | Human | USA | GQ505376 | − | GQ505470 | GQ505406 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 34012 | Human toe | USA | GQ505377 | − | GQ505471 | GQ505407 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 34014 | Human sinus | USA | GQ505379 | − | GQ505473 | GQ505409 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 34017 | Human sinus | USA | GQ505382 | − | GQ505476 | GQ505412 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 34018 | Human arm | USA | GQ505383 | − | GQ505477 | GQ505413 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 34019 | Human eye | USA | GQ505384 | − | GQ505478 | GQ505414 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 34022 | Human sinus | USA | GQ505386 | − | GQ505480 | GQ505416 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 43628 | Human finger | USA | GQ505393 | − | GQ505488 | GQ505424 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 43629 | Human blood | USA | GQ505394 | HM347186 | GQ505489 | GQ505425 | O’Donnell et al. (2009, 2010) | ||

| NRRL 43632 | Human eye | USA | GQ505396 | − | GQ505492 | GQ505428 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 43633 | Human sinus | USA | GQ505397 | − | GQ505493 | GQ505429 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 45992 | Human leg | USA | GQ505399 | − | GQ505495 | GQ505431 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| NRRL 52797 | Scirtothrips dorsalis | India | − | JF741015 | JF741190 | JF740865 | O’Donnell et al. (2012) | ||

| F. coffeatum | CBS 635.76 = BBA 62053 = NRRL 20841T | Cynodon lemfuensis | South Africa | MN120696 | MN120717 | MN120736 | MN120755 | Present study | |

| CBS 430.81 = NRRL 28577 | Grave stone | Romania | MN120697 | − | MN120737 | MN120756 | Present study | ||

| F. culmorum | NRRL 25475 = CBS 417.86 = FRC R-8504 = IMI 309344 | Hordeum vulgare | Denmark | − | JX171515 | JX171628 | AF212463 | O’Donnell et al. (2000, 2013) | |

| F. graminearum | NRRL 31084 = CBS 123657 | Zea mays | USA | − | JX171531 | JX171644 | HM744693 | O’Donnell et al. (2013), Yli-Mattila et al. (2011) | |

| NRRL 36905 | Triticum aestivum | USA | − | KM361646 | KM361664 | DQ459742 | Starkey et al. (2007), Aoki et al. (2015) | ||

| F. humicola | CBS 124.73 = ATCC 24372 = IMI 128101 = NRRL 25535T | Soil | Pakistan | MN120698 | MN120718 | MN120738 | MN120757 | Present study | |

| CBS 491.77 = NRRL 36495 | Soil | Kuwait | GQ505390 | MN120719 | GQ505485 | GQ505421 | O’Donnell et al. (2009) | ||

| F. lacertarum | NRRL 20423 = ATCC 42771 = CBS 130185 = IMI 300797T | Lizard skin | India | GQ505505 | JX171467 | JX171581 | GQ505593 | O’Donnell et al. (2009, 2013) | |

| CBS 127131 | Soil | USA | MN120699 | MN120720 | MN120739 | MN120758 | Present study | ||

| NRRL 43680 | Contact lens fluid | USA | − | − | EF470046 | EF453007 | O’Donnell et al. (2007) | ||

| F. langsethiae | NRRL 53409 | Hordeum vulgare | Finland | − | − | HQ154455 | HM744667 | Yli-Mattila et al. (2011) | |

| NRRL 53411 | Avena sativa | Finland | − | − | HQ154457 | HM744669 | Yli-Mattila et al. (2011) | ||

| NRRL 53417 | Avena sativa | Finland | − | KT597713 | HQ154460 | HM744672 | Yli-Mattila et al. (2011), Rocha et al. (2015) | ||

| NRRL 53436 | Hordeum vulgare | Russia | − | − | HQ154476 | HM744688 | Yli-Mattila et al. (2011) | ||

| NRRL 54940 | Avena sativa | Norway | − | JX171550 | JX171662 | − | O’Donnell et al. (2013) | ||

| F. lunulosporum | NRRL 13393 = BBA 62459 = CBS 636.76 = FRC R-5822 = IMI 322097T | Citrus paradisi | South Africa | − | KM361637 | KM361655 | AF212467 | O’Donnell et al. (2000), Aoki et al. (2015) | |

| F. microconidium | CBS 119843 = MRC 8391 | Unknown | Unknown | MN120700 | MN120721 | − | MN120759 | Present study | |

| F. nelsonii | CBS 119876 = FRC R-8670 = MRC 4570T | Plant debris | South Africa | MN120701 | MN120722 | MN120740 | MN120760 | Present study | |

| CBS 119877 = MRC 8520 | Unknown | Unknown | MN120702 | MN120723 | MN120741 | MN120761 | Present study | ||

| F. nodosum | CBS 200.63 | Arachis hypogaea | Portugal | MN120703 | MN120724 | MN120742 | MN120762 | Present study | |

| CBS 201.63T | Arachis hypogaea | Portugal | MN120704 | MN120725 | MN120743 | MN120763 | Present study | ||

| CBS 698. 74 | Arundo donax | France | MN120705 | MN120726 | MN120744 | MN120764 | Present study | ||

| CBS 119844 = BBA 62170 = MRC 1798 | Unknown | Unknown | MN120706 | MN120727 | − | MN120765 | Present study | ||

| CBS 131779 | Triticum aestivum | Iran | − | − | MN120745 | MN120766 | Present study | ||

| F. oxysporum | CBS 144143T | Solanum tuberosum | Germany | MH484771 | − | MH484953 | MH485044 | Lombard et al. (2019) | |

| F. peruvianum | CBS 511.75T | Gossypium sp. | Peru | MN120707 | MN120728 | MN120746 | MN120767 | Present study | |

| F. poae | NRRL 66297 | − | − | MG282363 | MG282392 | − | Waalwijk et al. (2018) | ||

| NRRL 13714 = MRC 2181 | Triticum aestivum | Canada | − | JX171458 | JX171572 | − | O’Donnell et al. (2013) | ||

| F. pseudograminearum | NRRL 28062 = CBS 109956 = FRC R-5291 = MAFF 237835T | Hordeum vulgare | Australia | − | JX171524 | JX171637 | AF212468 | O’Donnell et al. (2000, 2013) | |

| F. sibiricum | NRRL 53429 | Avena sativa | Russia | − | − | HQ154471 | HM744683 | Yli-Mattila et al. (2011) | |

| NRRL 53430T | Avena sativa | Russia | − | − | HQ154472 | HM744684 | Yli-Mattila et al. (2011) | ||

| NRRL 53431 = CBS 140945 | Avena sativa | Russia | − | − | HQ154473 | HM744685 | Yli-Mattila et al. (2011) | ||

| F. spinosum | CBS 122438 | Galia melon | Brazil (via Netherlands) | MN120708 | MN120729 | MN120747 | MN120768 | Present study | |

| NRRL 43631 | Human leg | USA | − | HM347187 | GQ505491 | GQ505427 | O’Donnell et al. (2009, 2010) | ||

| F. sporodochiale | CBS 199.63 = MUCL 6771 | Termitary | Unknown | MN120709 | MN120730 | MN120748 | MN120769 | Present study | |

| CBS 220.61 = ATCC 14167 = MUCL 8047 = NRRL 20842T | Soil | South Africa | MN120710 | MN120731 | MN120749 | MN120770 | Present study | ||

| F. sporotrichioides | CBS 462.94 | Glycosmis citrifolia | Austria | MN120711 | MN120732 | MN120750 | MN120771 | Present study | |

| NRRL 3299 = ATCC 24631 = CBS 119840 = FRC T-423 = MRC 1768 | Zea mays | France | − | JX171444 | GQ915498 | GQ915514 | Proctor et al. (2009), O’Donnell et al. (2013) | ||

| NRRL 29977 | Unknown | Yugoslavia | − | KT597711 | HQ154451 | HM744662 | Yli-Mattila et al. (2011), Rocha et al. (2015) | ||

| NRRL 52928 | Unknown | Turkey | − | − | JF741195 | JF740870 | O’Donnell et al. (2012) | ||

| NRRL 52934 | Unknown | Turkey | − | − | JF741201 | JF740876 | O’Donnell et al. (2012) | ||

| NRRL 53434 | Avena sativa | Russia | − | − | HQ154475 | HM744687 | Yli-Mattila et al. (2011) | ||

| F. tjaynera | NRRL 66246 = RBG5367T | Triodia microstachya | Australia | − | KP083268 | KP083279 | KP083266 | Laurence et al. (2016) | |

| NRRL 66247 = RBG5366 | Sorghum intrans | Australia | − | − | − | KP083266 | Laurence et al. (2016) | ||

| F. venenatum | NRRL 22196 = BBA 65031 | Zea mays | Germany | − | JX171494 | JX171607 | − | O’Donnell et al. (2013) | |

| FIESC 24 | CBS 101138 = BBA 70869 | Phaseolus vulgaris | Turkey | MN120712 | MN120733 | MN120751 | MN120772 | Present study | |

| NRRL 52777 | Eurygaster sp. | Turkey | − | JF741006 | JF741171 | JF740845 | O’Donnell et al. (2012) | ||

| NRRL 25080 | Nilaparvata lugens | China | − | − | JF741041 | JF740711 | O’Donnell et al. (2012) | ||

| Fusarium sp. | NRRL 13338 | Soil | Australia | GQ505372 | JX171447 | JX171561 | GQ505402 | O’Donnell et al. (2009, 2013) | |

1ATCC: American Type Culture Collection, USA; BBA: Biologische Bundesanstalt für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Berlin-Dahlem, Germany; CBS: Westerdijk Fungal Biodiverity Institute (WFBI), Utrecht, The Netherlands; DSM: Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany; FRC: Fusarium Research Center, Penn State University, Pennsylvania; IMI: International Mycological Institute, CABI-Bioscience, Egham, Bakeham Lane, UK; MRC: National Research Institute for Nutritional Diseases, Tygerberg, South Africa; MAFF: Genetic Resources Center, National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO), NARO Genebank, Microorganism Section, Japan; MUCL: Mycothéque de l’Université Catholique de Louvian, Belgium; NRRL: Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection, USA; RBG: Royal Botanic and Domain Trust, Sydney, Australia. T Ex-type culture; NTNeotype.

DNA isolation, PCR and sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted from 7-d-old isolates grown at 24 °C on potato dextrose agar (PDA; recipe in Crous et al. 2019) using the Wizard® Genomic DNA purification Kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Partial gene sequences were determined for the calmodulin (cmdA), RNA polymerase largest (rpb1) & second largest subunit (rpb2), and translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1), using PCR protocols and primer pairs described elsewhere (O’Donnell et al. 1998, 2009, 2010, Lombard et al. 2019). Integrity of the sequences was ensured by sequencing the amplicons in both directions using the same primer pairs as were used for amplification. Consensus sequences for each locus were assembled in Geneious R11 (Kearse et al. 2012). All sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank (Table 1).

Phylogenetic analyses

Initial analyses based on pairwise alignments and BLASTN searches on the Fusarium-MLST (www.wi.knaw.nl/fusarium/), Fusarium-ID (http://isolate.fusariumdb.org/guide.php; Geiser et al. 2004) and NCBI’s GenBank (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) databases were done using rbp2 and tef1 partial sequences. Based on these comparisons, sequences of relevant Fusarium species/strains were retrieved (Table 1) and alignments of the individual loci were determined using MAFFT v. 7.110 (Katoh et al. 2017) and manually corrected where necessary. Three independent phylogenetic algorithms, Maximum Parsimony (MP), Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI), were employed for phylogenetic analyses. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted of the individual loci and then as a multilocus sequence dataset that included partial sequences of the four genes determined here.

For BI and ML, the best evolutionary models for each locus were determined using MrModeltest v. 2 (Nylander 2004) and incorporated into the analyses. MrBayes v. 3.2.1 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003) was used for BI to generate phylogenetic trees under optimal criteria for each locus. A Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm of four chains was initiated in parallel from a random tree topology with the heating parameter set at 0.3. The MCMC analysis lasted until the average standard deviation of split frequencies was below 0.01 with trees saved every 1 000 generations. The first 25 % of saved trees were discarded as the ‘burn-in’ phase and posterior probabilities (PP) were determined from the remaining trees.

The ML analyses were performed using RAxML-NG v. 0.6.0 (Kozlov et al. 2018) to obtain another measure of branch support. The robustness of the analysis was evaluated by bootstrap support (BS) with the number of bootstrap replicates automatically determined by the software. For MP, analyses were done using PAUP (Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony, v. 4.0b10; Swofford 2003) with phylogenetic relationships estimated by heuristic searches with 1 000 random addition sequences. Tree-bisection-reconnection was used, with branch swapping option set on ‘best trees’ only. All characters were weighted equally and alignment gaps treated as fifth state. Measures calculated for parsimony included tree length (TL), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI) and rescaled consistence index (RC). Bootstrap (BS) analyses (Hillis & Bull 1993) were based on 1 000 replications. Alignments and phylogenetic trees derived from this study were uploaded to TreeBASE (S24459; www.treebase.org).

Morphological characterisation

All isolates were characterised following the protocols described by Leslie & Summerell (2006) and Lombard et al. (2019) using PDA, oatmeal agar (OA, recipe in Crous et al. 2019), synthetic nutrient-poor agar (SNA; Nirenberg 1976) and carnation leaf agar (CLA; Fisher et al. 1982). Colony morphology, pigmentation, odour and growth rates were evaluated on PDA after 7 d at 24 °C using a 12/12 h light/dark cycle with near UV and white fluorescent light. Colour notations were done using the colour charts of Rayner (1970). Micromorphological characters were examined using water as mounting medium on a Zeiss Axioskop 2 plus with Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) optics and a Nikon AZ100 dissecting microscope both fitted with Nikon DS-Ri2 high definition colour digital cameras to photo-document fungal structures. Measurements were taken using the Nikon software NIS-elements D v. 4.50 and the 95 % confidence levels were determined for the conidial measurements with extremes given in parentheses. For all other fungal structures examined, only the extremes are presented. To facilitate the comparison of relevant micro- and macroconidial features, composite photo plates were assembled from separate photographs using PhotoShop CSS.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic analyses

Approximately 500—650 bases were determined for cmdA and tef1, 1 845 bases for rpb1 and 1 800 bases for rpb2. Sequence comparisons of the rpb2 and tef1 gene regions generated in this study against those in the Fusarium-MLST, Fusarium-ID and GenBank databases revealed that only 14 isolates belonged to the FCSC. Of the remaining 9 isolates, three were identified as members of the F. incarnatum-equiseti species complex (FIESC) and six belonged in the F. sambucinum species complex (FSAMSC).

For the BI and ML analyses, a K80 model for cmdA, a GTR+I+G model for rbp1, an HKY+G+I model for rpb2 and an HKY+G for tef1 were selected and incorporated into the analyses. The ML tree topology confirmed the tree topologies obtained from the BI and MP analyses, and therefore, only the ML tree is presented.

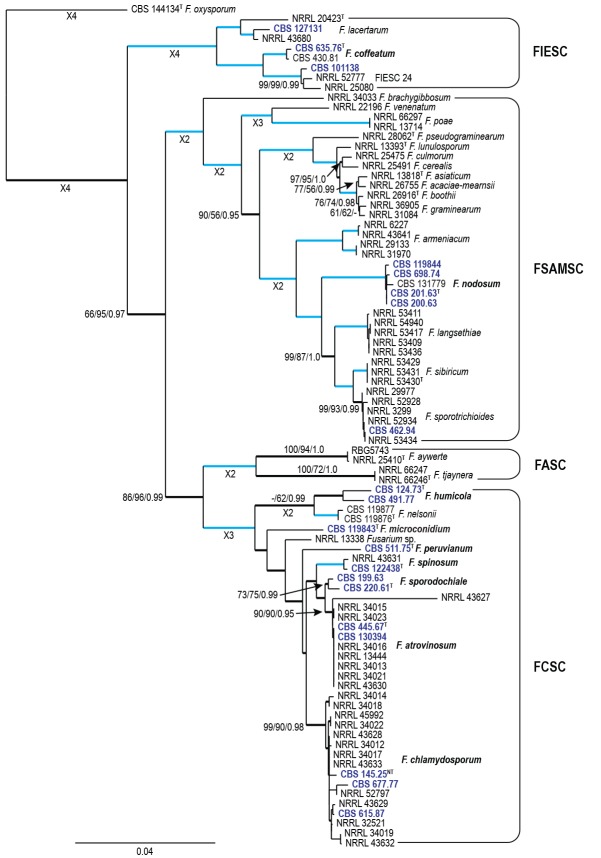

The combined four loci sequence dataset included 85 ingroup taxa with F. oxysporum (CBS 144134) as outgroup taxon. The dataset consisted of 4 875 characters including gaps. Of these characters, 3 267 were constant, 289 parsimony-uninformative and 1 319 parsimony-informative. The BI lasted for 18.8 M generations, and the consensus tree and posterior probabilities (PP) were calculated from 281 350 trees left after 93 782 were discarded as the ‘burn-in’ phase. The MP analysis yielded 1 000 trees (TL = 3 742; CI = 0.590; RI = 0.911; RC = 0.538) and a single best ML tree with -InL = -24632.989217 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The ML consensus tree inferred from the combined cmdA, rpb1, rpb2 and tef1 sequence alignment. Thickened branches indicate branches present in the ML, MP and Bayesian consensus trees. Blue thickened lines indicate branches with full support (ML & MP BS = 100, PP = 1.0) with support values of other branches indicated at the branches. The tree is rooted to Fusarium oxysporum (CBS 144143). The scale bar indicates 0.04 expected changes per site. Isolates in dark blue were preserved in the CBS collection as F. chlamydosporum. Species complexes are indicated on the right following O’Donnell et al. (2013) and Laurence et al. (2016). Neo- and ex-types are indicated as T and NT, respectively.

In the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1), the isolates thought to represent F. chlamydosporum clustered in three species complexes that included the FCSC, FIESC and FSAMSC. Three isolates clustered in the FIESC; CBS 127131 clustered in the F. lacertarum clade, CBS 635.76 (ex-type of F. chlamydosporum var. fuscum) clustered in the FIESC 28 clade, and CBS 101138 clustered in the FIESC 24 clade (O’Donnell et al. 2009, Wang et al. 2019). Six isolates clustered within the FSAMSC clade, of which CBS 462.94 clustered within the F. sporotrichioides clade. The remaining five isolates (CBS 200.63, 201.63, 698.74, 119844 & 131779) formed a highly-supported (ML- & MP-BS = 100, PP = 1.0) clade closely related but distinct from the F. langsethiae, F. sibiricum and F. sporotrichioides clades. Fourteen isolates clustered in the FCSC clade, of which three isolates (CBS 145.25, 615.87 & 677.77) clustered in the FCSC 1 (sensu O’Donnell et al. 2009), two (CBS 445.67 & 130394) in FCSC 2 (sensu O’Donnell et al. 2009), and one (CBS 122438) in FCSC 3 (sensu O’Donnell et al. 2009). Two isolates (CBS 199.63 & 220.61) formed a well-supported (ML-BS = 73, MP-BS = 75, PP = 0.99) distinct clade, sister to the FCSC 2 clade. Both isolates CBS 511.75 & 119843 formed two unique single lineages with the last four isolates (CBS 124.73, 491.77, 119876 & 119877) forming a distinct unique and supported (MP-BS = 62, PP = 0.99) clade in the FCSC.

Taxonomy

The following species are recognised as new within the FCSC and FSAMSC based on phylogenetic inference and morphological comparisons. In addition, F. chlamydosporum var. fuscum is raised to species level, as F. coffeatum, in the FIESC based on the placement of the ex-type strain in the phylogenetic inference and a neotype is designated for F. chlamydosporum. The single lineage represented by NRRL 13338 is not treated here, as the strain was not available to us at the time of this study.

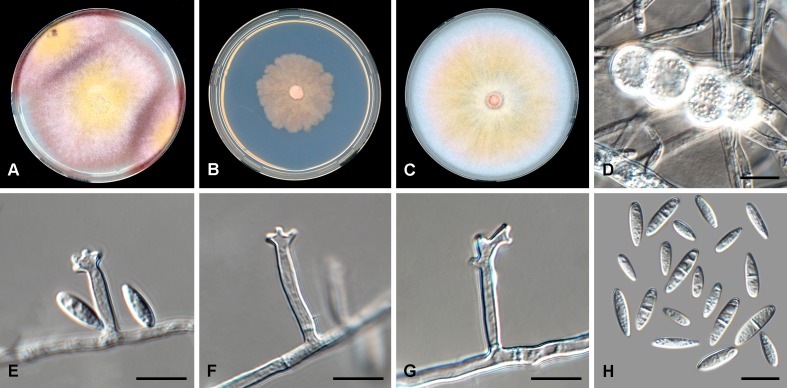

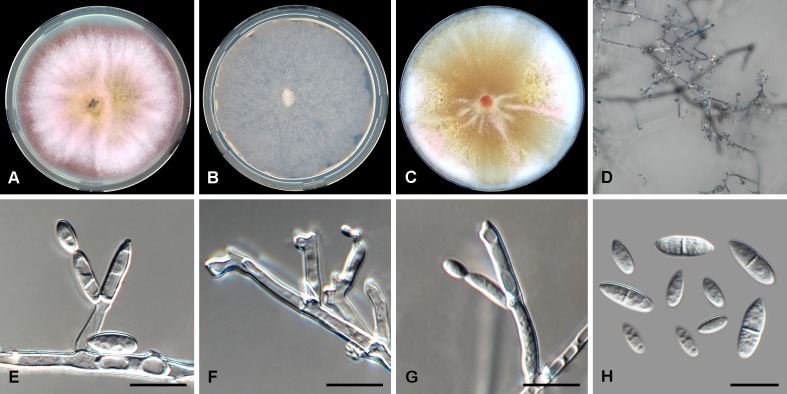

Fusarium atrovinosum L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB831559. Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fusarium atrovinosum (CBS 445.67). A. Colony on PDA. B. Colony on SNA. C. Colony on OA. D. Chlamydospores on SNA. E–G. Polyphialides on aerial mycelium. H. Aerial conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Etymology: Named after the dark wine-red (dark vinaceous) reverse colouration of the PDA on which this fungus is grown.

Diagnosis: Only producing 0–1-septate aerial conidia (i.e. microconidia) on rarely branched polyphialides in culture with abundant chlamydospores.

Typus: Australia, from Triticum aestivum, 1961, W.L. Gordon (holotype CBS-H 24015 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 445.67 = BBA 10357 = DSM 62169 = IMI 096270 = NRRL 26852 = NRRL 26913).

Conidiophores carried on aerial mycelium 20–40 μm tall, unbranched or rarely irregularly or sympodially branched, bearing a terminal single phialide or whorl of 2–3 phialides; aerial phialides polyphialidic, subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 9–23 × 2–4 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the phialide tips, hyaline, fusiform to ellipsoidal to obovoid, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1(–2)-septate; 0-septate conidia: 7–11(–15) × 2–4(–5) μm (av. 9 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: (11–)13–17(–20) × 4–6 μm (av. 15 × 5 μm); 2-septate conidia: (12–)14–18(–20) × 4–5 μm (av. 16 × 5 μm). Sporodochia not observed. Chlamydospores abundant, globose to subglobose, thick-walled, smooth to slightly verrucose, 12–22 μm diam, formed terminally or intercalarily in chains of three or more.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PDA reaching 90 mm at 24 °C after 7 d. Colony surface greyish rose to vinaceous to buff in the centre, with abundant aerial mycelium, dense, woolly to cottony. Odour absent. Reverse livid red to dark vinaceous. On SNA, colonies membranous to woolly, white to pale rosy buff, with abundant sporulation on the surface giving a powdery appearance; reverse pale rosy buff. On CLA, aerial mycelium abundant, white, lacking sporodochia on the carnation leaf pieces. On OA, colonies woolly to cottony, buff in the centre becoming rosy vinaceous towards margins, appearing powdery.

Notes: Fusarium atrovinosum represents the clade FCSC 2 sensu O’Donnell et al. (2009). This species is closely related to F. chlamydosporum, F. spinosum and F. sporodochiale and can be distinguished from these three species by the lack of monophialides on the aerial mycelium. Additionally, F. atrovinosum did not produce any sporodochia on the carnation leaf pieces but did produce abundant chlamydospores, further distinguishing it from F. sporodochiale.

Fusarium chlamydosporum Wollenw. & Reinking, Phytopathology 15: 156. 1925.

Synonyms: Fusarium sporotrichioides var. chlamydosporum (Wollenw. & Reinking) Joffe, Mycopath. Mycol. Appl. 53: 211. 1974.

Dactylium fusarioides Gonz. et al., Boln. Real Soc. Españ. Hist. Nat., Biol. 27: 280. 1928.

Fusarium fusarioides (Gonz., et al.) C. Booth, The genus Fusarium: 88. 1971.

Fusarium sporotrichioides subsp. minus (Wollenw.) Riallo, Fungi of the genus Fusarium: 196. 1950.

Fusarium sporotrichiella var. sporotrichioides Bilai, Fusarii: 277. 1955.

Pseudofusarium purpureum Matsush., Microfungi Solomon Isl. Papua-New Guinea (Osaka): 47. 1971.

Neotypus: Honduras, Tela, from pseudostem of Musa sapientum, H.W. Wollenweber & O.A. Reinking [neotype CBS 145.25 designated here (as metabolic inactive specimen), culture ex-neotype CBS 145.25 = NRRL 26912; MBT387601].

Descriptions and illustrations: Reinking & Wollenweber (1927), Wollenweber & Reinking (1925, 1935).

Notes: A letter from C.L. Shear (dated 23 January 1925) addressed to Prof. dr J. Westerdijk, director of the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (now WI), indicated that CBS 145.25 (as no. 871) is F. chlamydosporum (as “F. chlamydosporum n. sp.”) isolated from banana collected in Tela, Honduras. He further confirmed that this isolate was identified by H.W. Wollenweber and O.A. Reinking. However, it is not clearly indicated whether this isolate represents the ex-type. Therefore, based on the matching geography, host and date, we designate this isolate as neotype of F. chlamydosporum.

Fusarium coffeatum L. Lombard & Crous, stat. et. nom. nov. MycoBank MB831560.

Basionym: Fusarium chlamydosporum var. fuscum Gerlach, Phytopath. Z. 90: 41. 1977.

Etymology: Name refers to the characteristic coffee-brown pigmentation produced in cultures of this fungus.

Descriptions and illustrations: Gerlach (1977), Gerlach & Nirenberg (1982).

Notes: Gerlach (1977) and Gerlach & Nirenberg (1982) distinguished F. chlamydosporum var. fuscum from F. chlamydosporum var. chlamydosporum based on the beige to coffee-brown pigmentation in culture of the former variety, compared to the red pigment produced by the latter. Phylogenetic inference and sequence comparisons with the Fusarium databases and GenBank, showed that the ex-type (CBS 635.76; Fig. 1) of F. chlamydosporum var. fuscum belongs in the FIESC, clustering in the yet unnamed FIESC 28 clade (Wang et al. 2019). Therefore, this variety is raised to species level with a new name as the name F. fuscum is already occupied.

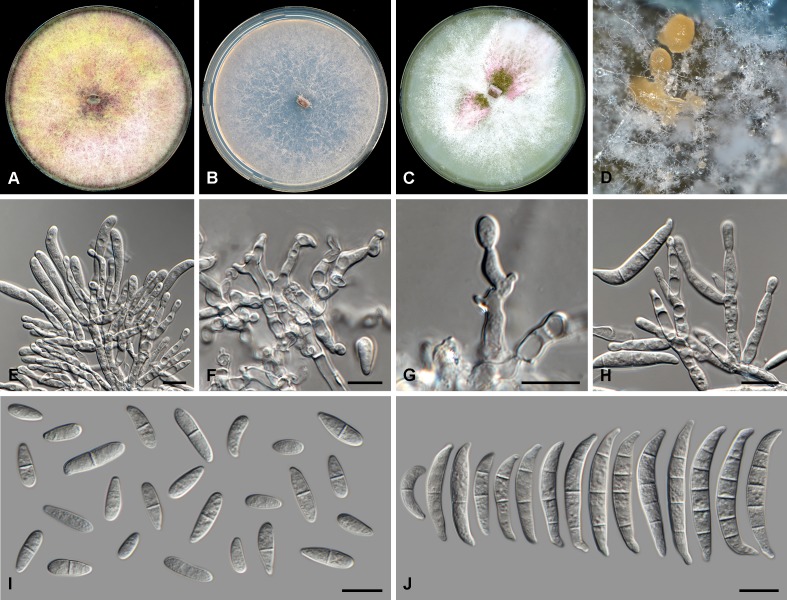

Fusarium humicola L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB83156. Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Fusarium humicola (CBS 124.73). A. Colony on PDA. B. Colony on SNA. C. Colony on OA. D. Sporodochia on carnation leaf pieces. E. Sporodochial conidiophores. F. Conidiophores on aerial mycelium. G. Polyphialides. H. Monophialides. I. Aerial conidia. J. Sporodochial conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Etymology: Named after the substrate, soil, from which the majority of the isolates of this species were isolated.

Diagnosis: Sporodochial conidia mostly straight but slightly curved at both ends; aerial conidia mostly 0–1-septate; chlamydospores not formed.

Typus: Pakistan, from soil, date unknown, S.I. Ahmed (holotype CBS-H 24016 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 124.73 = ATCC 24372 = IMI 128101 = NRRL 25535).

Conidiophores borne on aerial mycelium 40–120 μm tall, verticillately branched, rarely unbranched, bearing a terminal single phialide or whorl of 2–3 phialides; aerial phialides mono- and polyphialidic, subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 10–35 × 3–6 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, ellipsoidal to obovoid, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–3-septate; 0-septate conidia: (6–)7–11(–16) × (2–)3–5(–6) μm (av. 9 × 4 μm); 1-septate conidia: (10–)11–15(–18) × 4–6 μm (av. 13 × 5 μm); 2-septate conidia: (15–)16–18(–19) × 4–5 μm (av. 17 × 5 μm); 3-septate conidia: (17–)18–24(–26) × 4–6 μm (av. 21 × 5 μm). Sporodochia pale luteous to pale salmon, formed sparsely on carnation leaves. Sporodochial conidiophores verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thin-walled stipe bearing apical whorls of 2–4 monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 10–25 × 3–5 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, mostly straight with dorsiventrally curved apical and basal cells, tapering towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt and distinctly foot-like basal cell, 3–5-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 3-septate conidia: (30–)34–40(–44) × 4–6 μm (av. 37 × 5 μm); 4-septate conidia: (33–)37–45(–50) × 4–6 μm (av. 41 × 5 μm); 5-septate conidia: (43–)47–55(–59) × 4–6(–7) μm (av. 51 × 5 μm). Chlamydospores not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PDA reaching 75–85 mm at 24 °C after 7 d. Colony surface fulvous to ochreous in the centre becoming vinaceous to livid red towards the margin, with moderate aerial mycelium, dense, woolly to cottony. Odour absent. Reverse dark vinaceous to vinaceous. On SNA reaching 45–60 mm at 24 °C after 7 d, colonies membranous, greyish rose to rosy vinaceous, margin entire to undulate; reverse greyish rose to rosy vinaceous. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant pale luteous to pale salmon sporodochia forming on the carnation leaves. On OA, colonies reaching 90 mm at 24 °C after 7 d, membranous to cottony, centre rosy vinaceous to greyish rose becoming honey to buff towards the margins; margins entire, reverse honey to buff.

Additional material examined: Kuwait, from soil, date unknown, A.F. Moustafa, CBS 491.77.

Notes: Fusarium humicola is closely related to F. nelsonii in the FCSC. Fusarium nelsonii produces more strongly curved and smaller sporodochial conidia (20–42 × 4–6 μm; Marasas et al. 1998) than those of F. humicola (30–59 × 4–6 μm overall). Additionally, F. humicola did not produce any chlamydospores, even after 4 wk on SNA, whereas F. nelsonii produces these rapidly and abundantly (Leslie & Summerell 2006).

Fusarium microconidium L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB831562. Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Fusarium microconidium (CBS 119843). A. Colony on PDA. B. Colony on SNA. C. Colony on OA. D. Aerial mycelium with conidiophores on SNA. E–G. Mono- and polyphialides on aerial mycelium. H. Aerial conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Etymology: Named after the only conidial form, microconidia (i.e. aerial conidia), produced in culture.

Diagnosis: Only producing 0–1-septate aerial conidia (i.e. microconidia) in culture and no sporodochial conidia (i.e. macroconidia) or chlamydospores.

Typus: Unknown, unknown collector, date and substrate, deposited by W.F.O. Marasas (holotype CBS-H 24017 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 119843 = MRC 8391 = KSU 11396).

Conidiophores borne on aerial mycelium, 20–40 μm tall, irregularly or sympodially branched or unbranched, bearing a terminal single phialide or whorl of 2–4 phialides; aerial phialides mono- and polyphialidic, subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 11–26 × 2–5 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; monophialides carried singly directly on aerial mycelium; polyphialides borne on branched conidiophores; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, fusiform to ellipsoidal to obovoid, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: (6–)7–11(–13) × 4–5(–6) μm (av. 9 × 4 μm); 1-septate conidia: (11–)13–15(–16) × 4–6 μm (av. 14 × 5 μm). Sporodochia and chlamydospores not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PDA reaching 90 mm at 24 °C after 7 d. Colony surface rose to rosy vinaceous to pale luteous in the centre, with abundant aerial mycelium, dense, woolly to cottony. Odour absent. Reverse livid red to dark vinaceous. On SNA, colonies membranous to woolly, white to pale rosy buff, with abundant sporulation on the surface giving a powdery appearance; reverse pale rosy buff. On CLA, aerial mycelium abundant, white, lacking sporodochia on the carnation leaf pieces. On OA, colonies membranous to cottony, white to buff with rosy flames towards margins, appearing wet.

Notes: Fusarium microconidium represents a unique single lineage in the FCSC. This species is distinguished from other species in the FCSC based on the production of predominantly aseptate aerial conidia (i.e. microconidia) and lack of sporodochia and chlamydospores.

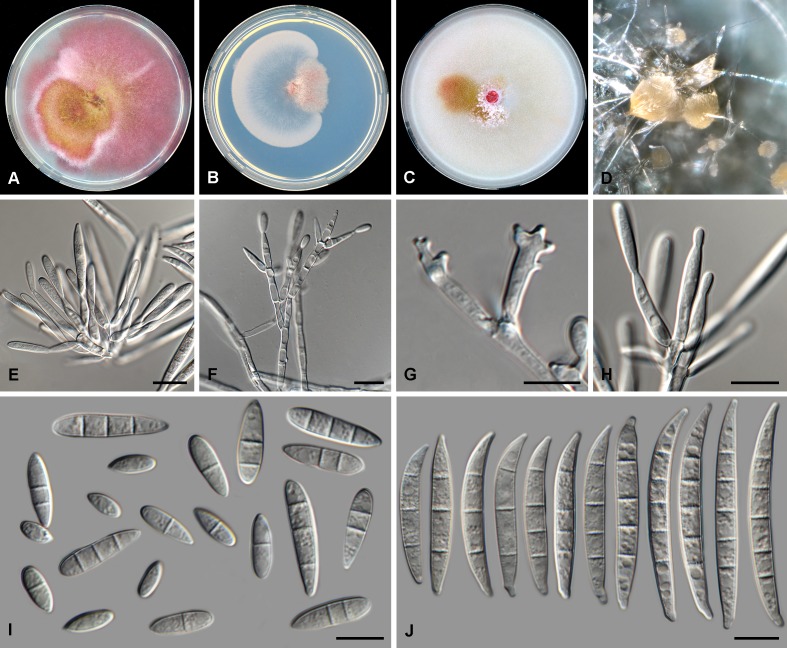

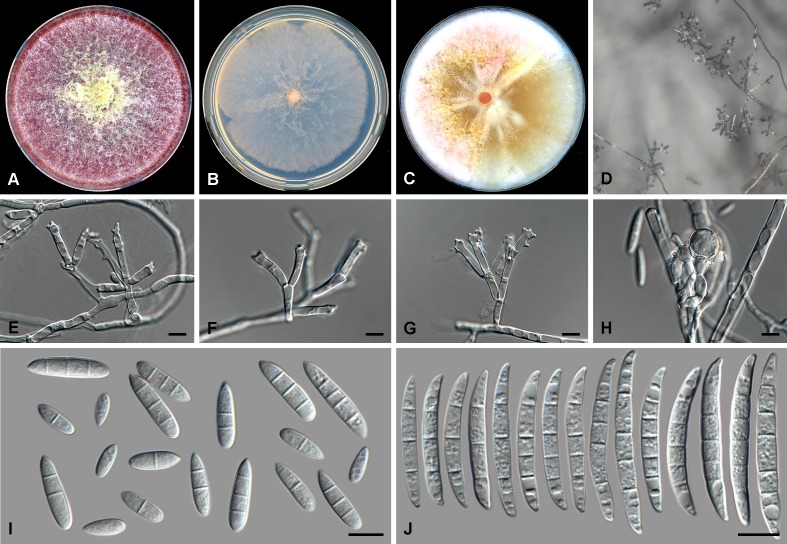

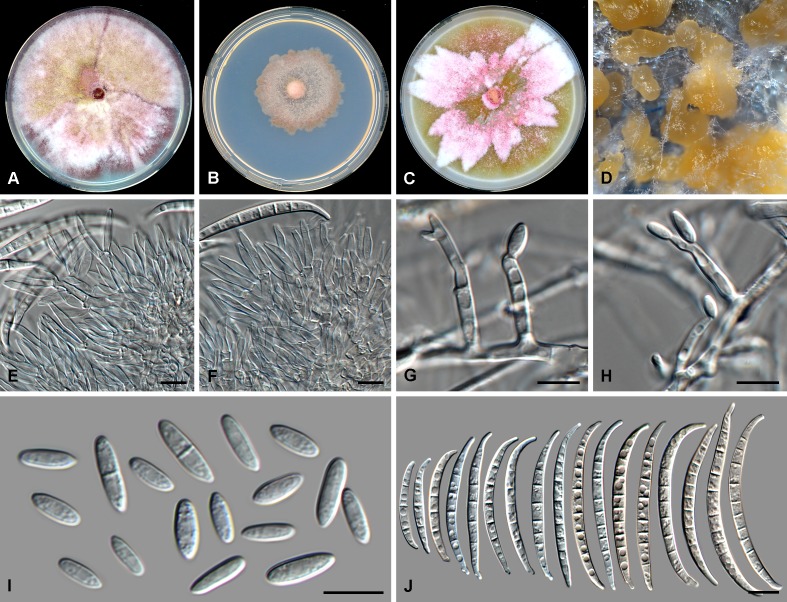

Fusarium nodosum L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB831653. Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Fusarium nodosum (CBS 201.63). A. Colony on PDA. B. Colony on SNA. C. Colony on OA. D. Sporodochia on carnation leaf pieces. E. Sporodochial conidiophores. F, G. Polyphialides on aerial mycelium. H. Monophialides on aerial mycelium. I. Aerial conidia. J. Sporodochial conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Etymology: Named after the knotted appearance of the polyphialidic aerial conidiophores.

Diagnosis: Rarely producing globose aerial conidia (micro-conidia).

Typus: Portugal, Lisbon, stored seed of Arachis hypogaea, 19 Dec. 1961, C.M. Baeta Neves (holotype CBS-H 24018 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 201.63).

Conidiophores borne on aerial mycelium, 10–65 μm tall, irregularly or sympodially branched or rarely unbranched, bearing a terminal single phialide or whorl of 2–4 phialides; aerial phialides mono- and polyphialidic, subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 10–22 × 3–4 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the phialide tips, hyaline, ellipsoidal to obovoid, rarely globose, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–1-septate; 0-septate conidia: (6–)9–13(–15) × 4–5 μm (av. 11 × 4 μm); 1-septate conidia: (11–)13–19(–21) × 2–4 μm (av. 16 × 5 μm). Sporodochia pale luteous to pale orange, formed abundantly on carnation leaves. Sporodochial conidiophores verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thin-walled stipe bearing apical whorls of 2–4 monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 10–21 × 3–5 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, curved dorsiventrally, broadening in the upper third, tapering towards both ends, with a blunt to papillate, curved apical cell and a blunt and distinctly foot-like basal cell, (1–)3–5-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 1-septate conidia: (24–)26–36(–38) × 4–6 μm (av. 31 × 5 μm); 2-septate conidia: (21–)24–30(–32) × 4–6 μm (av. 27 × 5 μm); 3-septate conidia: (26–)28–36(–40) × 5–7 μm (av. 32 × 6 μm); 4-septate conidia: (34–)36–42(–50) × (4–)5–7 μm (av. 39 × 6 μm); 5-septate conidia: (37–)40–44(–47) × 5–7 μm (av. 42 × 6 μm). Chlamydospores not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PDA reaching 90 mm at 24 °C after 7 d. Colony surface rose to rosy vinaceous to sulphur yellow, with abundant aerial mycelium, dense, woolly to cottony. Odour absent. Reverse livid red to rose. On SNA, colonies membranous to woolly, white to pale rosy buff, with abundant sporulation on the surface giving a powdery appearance; reverse pale rosy buff. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant pale luteous to pale orange sporodochia forming on the carnation leaves. On OA, colonies membranous to cottony, white to rosy buff, with abundant sporulation on substrate giving a powdery appearance.

Additional materials examined: France, Cassis, stem of Arundo donax, Oct. 1974, W. Gams, CBS 698.74. Iran, Golestan, Kalaleh, from wheat, M. Davari, CBS 131779. Portugal, Lisabon, stored seed of Arachis hypogaea, 19 Dec. 1961, C.M. Baeta Neves, CBS 200.63. Unknown locality, substrate and date, W.F.O. Marasas, CBS 119844 = BBA 62170 = MRC 1798.

Notes: Fusarium nodosum is closely related to F. armeniacum, F. langsethiae, F. sibiricum and F. sporotrichioides in the FSAMSC. Fusarium armeniacum characteristically does not produce polyphialidic conidiogenous cells (Burgess et al. 1993), distinguishing this species from F. nodosum. The remaining three species readily produce abundant globose aerial conidia (i.e. microconidia), which were rarely seen for F. nodosum.

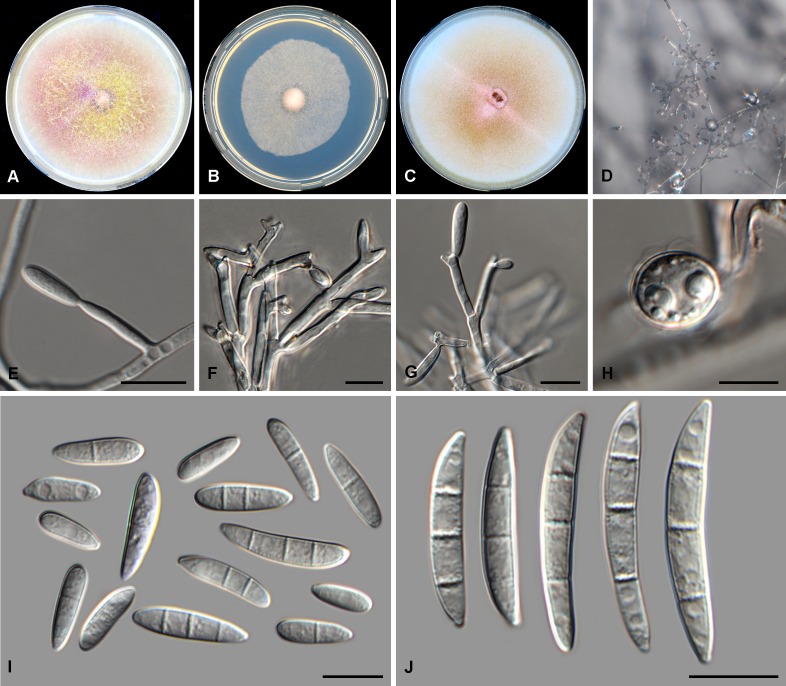

Fusarium peruvianum L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB831564. Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Fusarium peruvianum (CBS 511.75). A. Colony on PDA. B. Colony on SNA. C. Colony on OA. D. Aerial mycelium with conidiophores on SNA. E–G. Mono- and polyphialides on aerial mycelium. H. Chlamydospores. I. Ellipsoidal to obovoid aerial conidia. J. Falcate aerial conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Etymology: Named after Peru, from where this fungus was collected.

Diagnosis: Producing both falcate (i.e. macroconidia) and ellipsoidal to obovoid (i.e. microconidia) aerial conidia on predominantly polyphialidic conidiogenous cells borne on aerial mycelium, lacking sporodochia, but readily producing chlamydospores.

Typus: Peru, from Gossypium sp. seedling, date unknown, J.H. van Emden (holotype CBS-H 24019 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 511.75).

Conidiophores borne on aerial mycelium, 10–85 μm tall, irregularly or sympodially branched, rarely unbranched, bearing a terminal whorl of 2–4 phialides; aerial phialides polyphialidic, rarely monophialidic, subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 14–28 × 2–5 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, of two types: (a) ellipsoidal to obovoid, 0–3(–4)-septate; 0-septate conidia: (9–)10–14(–15) × (3–)4–6 μm (av. 12 × 5 μm); 1-septate conidia: (12–)13–17(–19) × 4–6 μm (av. 15 × 5 μm); 2-septate conidia: 17–21(–24) × 5–7 μm (av. 19 × 6 μm); 3-septate conidia: (18–) 19–23(–26) × (5–)6(–7) μm (av. 21 × 6 μm); 4-septate conidia: 28 × 6 μm; (b) falcate, fusiform to falcate, straight or gently dorsiventrally curved, with an indistinct papillate to notched basal cell, 3–4(–5)-septate; 3-septate conidia: (29–)33–39(–41) × 4–6 μm (av. 36 × 5 μm); 4-septate conidia: (32–)37–45(–51) × 4–6 μm (av. 41 × 5 μm); 5-septate conidia: (40–)41–49(–50) × 5–6 μm (av. 45 × 5 μm). Sporodochia not observed. Chlamydospores abundant, formed singly or in pairs, carried terminally or intercalarily, globose to subglobose, 10–25 μm diam, thick-walled, smooth to slightly verrucose.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PDA reaching 90 mm at 24 °C after 7 d. Colony surface fulvous to ochreous in the centre becoming coral to vinaceous towards the margin, with abundant aerial mycelium, dense, woolly to cottony, sometimes granular due to abundant sporulation on medium surface. Odour absent. Reverse livid red to dark vinaceous. On SNA, colonies membranous to woolly, white, with abundant sporulation on the surface giving a powdery appearance; reverse colourless. On CLA, white aerial mycelium abundant, lacking sporodochia on carnation leaves. On OA, colonies cottony, ochreous to luteous in the centre with pale rosy vinaceous to rose flames, with abundant sporulation on substrate giving a powdery appearance.

Notes: Fusarium peruvianum represents the second unique single lineage in the FCSC. This species can be distinguished from other species in the FCSC based on the formation of falcate aerial conidia (i.e. macroconidia) on all substrates examined. Furthermore, F. peruvianum produced 4-septate obovoid aerial conidia (i.e. microconidia), a characteristic not observed for any of the other species in the FCSC studied here.

Fusarium spinosum L. Lombard, Houbraken & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB831565. Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Fusarium spinosum (CBS 122438). A. Colony on PDA. B. Colony on SNA. C. Colony on OA. D. Aerial mycelium with conidiophores on SNA. E. Monophialide on aerial mycelium. F, G. Polyphialides on aerial mycelium. H. Chlamydospore. I. Ellipsoidal to obovoid aerial conidia. J. Falcate aerial conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the “thorny” appearance of the polyphialides borne on the aerial mycelium.

Diagnosis: Only producing 3-septate, falcate aerial conidia (i.e. macroconidia) in culture, lacking sporodochia.

Typus: Brazil, from Galia melon imported into the Netherlands, 2007, J. Houbraken (holotype CBS-H 24020 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 122438).

Conidiophores borne on aerial mycelium 8–55 μm tall, irregularly or sympodially branched or unbranched, bearing a lateral single phialide or terminal whorl of 2–4 phialides; aerial phialides mono- and polyphialidic, subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 10–35 × 3–6 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; monophialides carried singly directly on aerial mycelium; polyphialides borne on branched conidiophores; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, of two types: (a) fusiform to ellipsoidal to obovoid, straight to slightly curved, smooth- and thin-walled, 0–3-septate; 0-septate conidia: 11–17(–21) × 3–5 μm (av. 14 × 4 μm); 1-septate conidia: (12–)13–19(–24) × 3–5 μm (av. 16 × 4 μm); 2-septate conidia: (17–)18–22(–28) × 4–6 μm (av. 20 × 5 μm); 3-septate conidia: (19–)20–22(–29) × 4–6 μm (av. 21 × 5 μm); (b) falcate, slightly dorsiventrally curved, 3-septate, with an indistinct papillate to notched basal cell, (22–)24–32(–36) × 4–6 μm (av. 28 × 5 μm). Sporodochia not observed. Chlamydospores abundant, globose to subglobose, thick-walled, smooth to slightly verrucose, 12–24 μm diam, borne terminally or carried intercalarily, single or in chains.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PDA reaching 90 mm at 24 °C after 7 d. Colony surface rose to rosy vinaceous to pale luteous in the centre, with abundant aerial mycelium, dense, woolly to cottony. Odour absent. Reverse fulvous to ochreous with rosy vinaceous flames. On SNA, colonies membranous to woolly, white to pale rosy buff, with abundant sporulation on the surface giving a powdery appearance; reverse pale rosy buff. On CLA, aerial mycelium abundant, white, lacking sporodochia on the carnation leaf pieces. On OA, colonies membranous to cottony, white to buff with rosy flames towards margins, with powdery appearance due to abundant sporulation on medium surface.

Notes: Fusarium spinosum represents the FCSC 3 sensu O’Donnell et al. (2009). This species is distinguished from other species in the FCSC by only forming 3-septate, falcate aerial conidia (i.e. macroconidia).

Fusarium sporodochiale L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB831566. Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Fusarium sporodochiale (CBS 220.61). A. Colony on PDA. B. Colony on SNA. C. Colony on OA. D. Sporodochia on carnation leaf pieces. E, F. Sporodochial conidiophores. G, H. Mono- and polyphialides on aerial mycelium. I. Aerial conidia. J. Sporodochial conidia. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Etymology: Named after the abundant sporodochia this species produces on carnation leaf pieces.

Diagnosis: Producing up to 10-septate sporodochial conidia (i.e. macroconidia) and aseptate, rarely 1-septate aerial conidia (i.e. microconidia).

Typus: South Africa, Gauteng, Johannesburg, from soil, 29 May 1955, D. Ordman (holotype CBS H-12681 designated here, culture ex-type CBS 220.61 = ATCC 14167 = MUCL 8047 = NRRL 20842).

Conidiophores borne on aerial mycelium, 10–35 μm tall, irregularly or sympodially branched or unbranched, bearing a lateral single phialide or terminal whorl of 2–4 phialides; aerial phialides polyphialidic, rarely monophialidic, subulate to subcylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, 11–23 × 2–4 μm, periclinal thickening inconspicuous or absent; aerial conidia forming small false heads on the tips of the phialides, hyaline, fusiform to ellipsoidal to obovoid, smooth- and thin-walled, aseptate, rarely 1-septate; 0-septate conidia: (7–)8–12(–13) × 2–4(–5) μm (av. 10 × 3 μm); 1-septate conidia: 11–17(–21) × 3–5 μm (av. 14 × 3 μm). Sporodochia pale luteous to pale orange, formed abundantly on carnation leaves and on media surfaces. Sporodochial conidiophores verticillately branched and densely packed, consisting of a short, smooth- and thin-walled stipe bearing apical whorls of 2–4 monophialides; sporodochial phialides subulate to subcylindrical, 11–25 × 2–4 μm, smooth- and thin-walled, sometimes showing a reduced and flared collarette. Sporodochial conidia falcate, slightly to strongly dorsiventrally curved, tapering towards both ends, with an elongated, strongly curved apical cell and a blunt and distinct foot-like basal cell, (1–)5–6(–10)-septate, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled; 3-septate conidia: (31–)32–40(–42) × 4–5 μm (av. 36 × 4 μm); 4-septate conidia: (38–)41–49(–53) × 3–5 μm (av. 45 × 5 μm); 5-septate conidia: (45–)50–58(–61) × 4–6(–7) μm (av. 54 × 5 μm); 6-septate conidia: (51–)54–63(–71) × 4–6 μm (av. 59 × 5 μm); 7-septate conidia: (52–)56–66(–72) × 4–6 μm (av. 61 × 5 μm) ; 8-septate conidia: (56–)57–63(–72) × 4–6 μm (av. 61 × 5 μm). Chlamydospores not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PDA reaching 85–90 mm at 24 °C after 7 d. Colony surface rose to rosy vinaceous to sulphur yellow, with abundant aerial mycelium, dense, woolly to cottony. Odour absent. Reverse livid red to dark vinaceous. On SNA, colonies woolly, surface and reverse pale rosy buff. On CLA, aerial mycelium sparse with abundant pale luteous to pale orange sporodochia forming on the carnation leaves and surrounding medium surface. On OA, colonies membranous with cottony, rosy buff flames of aerial mycelium, with abundant sporulation.

Additional material examined: Germany, Berlin, from a termitary, date unknown, W. Kerner, CBS 199.63 = MUCL 6771.

Notes: Fusarium sporodochiale is a morphologically unique member of the FCSC, as this species can produce up to 10-septate sporodochial conidia (i.e. macroconidia). Additionally, the apical cell of the sporodochial conidia of F. sporodochiale is more elongated than those noted for F. chlamydosporum (Leslie & Summerell 2006) or any other species in this complex. A unique feature of this species is the abundance of sporodochia formed, not only on the carnation leaf pieces, but also on the medium surface.

DISCUSSION

A key component of modern taxonomic studies of the genus Fusarium is multilocus phylogenetic inference due to the numerous cryptic species now known to be present in the various species complexes. Therefore, the availability of type material plays a vital role in providing stability to a dynamic taxonomic system as is seen in Fusarium literature today. The FCSC is no exception as at least four unnamed phylo-species have been identified in the past (O’Donnell et al. 2009, 2018), which were initially identified as F. chlamydosporum.

Phylogenetic inference in this study resolved four additional phylo-species to the five already resolved by O’Donnell et al. (2009, 2018), of which three could be provided with names (F. humicola, F. microconidium and F. peruvianum) here, and one single lineage (NRRL 13338) initially treated as F. nelsonii (O’Donnell et al. 2009), remaining to be named. Neotypification of F. chlamydosporum in this study has allowed us to provide names for the remaining unnamed phylo-species: FCSC 1 = F. chlamydosporum; FCSC 2 = F. atrovinosum; FCSC 3 = F. spinosum; FCSC 5 = F. sporodochiale.

The ex-neotype strain (CBS 145.25) of F. chlamydosporum was found in this study to have deteriorated since 1925, and produced only a few aerial conidia (i.e. microconidia) on CLA, and none on PDA, SNA or OA. The same was observed for strains CBS 615.87 and CBS 677.77, indicating that strains of this species could deteriorate quickly during long-term storage. Booth (1971) also studied the (now) ex-neotype of F. chlamydosporum and concluded that this species is a nomen confusum as he was unable to distinguish it from F. camptoceras at that time. Gerlach & Nirenberg (1982) accepted F. chlamydosporum as a distinct species and rejected Booth’s (1971) argument. However, Marasas et al. (1998) provided an emended description for F. camptoceras, clearly distinguishing it from F. chlamydosporum. The F. chlamydosporum clade (FCSC 1) included for the most part clinical isolates, but also isolates obtained from plants (banana and taro), thrips and soil (Table 1), indicating that this species has a broad ecological range. The remaining clinical isolates clustered in the F. atrovinosum (eight isolates) and F. spinosum (one isolate) clades. Both these latter species also included isolates obtained from plants and soil, reflective of a possible broader ecological range. The number of clinical isolates in each of these three species may not be a true reflection of their ecology, as this only represents the sample of sequence data available in public databases such as GenBank, FUSARIUM-ID and Fusarium MLST.

Isolates CBS 511.75, CBS 119843 and NRRL 13338 were resolved as single lineages in this study. All three these single lineages were also resolved in the individual analyses of the four loci used in this study (results not shown). Therefore, we introduced the names F. microconidium (CBS 119843) and F. peruvianum (CBS 511.75) for two of these single lineages, with a name pending for NRRL 13338 following morphological analysis.

Pairwise sequence comparisons of the tef1 and rpb2 sequences of MRC 35 (MH582448 & MH582208, respectively) and MRC 117 (MH582447 & MH 582074, respectively), identified by O’Donnell et al. (2018) as FCSC 5, with those of the ex-type of F. sporodochiale (CBS 220.61) showed 99 % sequence similarity for both loci compared to the 96 % similarity found with the neo/ex-type isolates of F. atrovinosum (CBS 445.67), F. chlamydosporum (CBS 145.25) and F. spinosum (CBS 122438), which were the closest phylogenetic neighbours. Therefore, we are able to link both CBS 220.61 and CBS 199.63 to FCSC 5 in this study. The tef1 and rpb2 sequences for both MRC 35 and MRC 117 were not available at the time, and could therefore not be included in this study.

To our knowledge, the ex-type strain of F. chlamydosporum var. fuscum (CBS 635.76; Gerlach 1977) has not yet been included in any phylogenetic study until now. However, it was surprising to observe its placement in the FIESC, clustering with CBS 430.81, an isolate known to represent the phylo-species FIESC 28 (O’Donnell et al. 2009). As no Latin name has yet been assigned to FIESC 28, we decided to raise this variety to species level with a new name, F. coffeatum. Two additional isolates preserved as F. chlamydosporum in the CBS culture collection also clustered within the FIESC. Isolate CBS 127131 proved to belong in the F. lacertarum clade, whereas CBS 101138 clustered within the FIESC 24 clade (O’Donnell et al. 2009). Both these isolates failed to produce sporodochia on CLA under UV-illumination, but produced abundant aerial conidia (i.e. microconidia), chlamydospores and a dark red pigmentation on the various media used here, similar to those associated with F. chlamydosporum. These characteristics probably resulted in the erroneous identification of these isolates.

Several isolates also clustered within the FSAMSC, with CBS 462.94 falling within the F. sporotrichioides clade. This isolate also failed to produce sporodochia on CLA but produced abundant aerial conidia (i.e. microconidia) and the characteristic red pigment in culture. However, no chlamydospores were observed. Either this isolate has been misidentified or became contaminated with F. sporotrichioides over time. The remaining four “F. chlamydosporum” isolates (CBS 200.63, CBS 201.63, CBS 698.74 & CBS 119844) formed a highly supported clade, distinct from the F. armeniacum, F. langsethiae, F. sibiricum and F. sporotrichioides clades, and were named as F. nodosum. The F. nodosum clade also included an isolate (CBS 131779) previously identified as F. sporotrichioides (Davari et al. 2013). It is not clear why these isolates were initially preserved in the CBS culture collection under the name F. chlamydosporum. The most noticeable overlapping character observed for these isolates with F. chlamydosporum, was the production of dark red pigments on PDA. These isolates all readily produced abundant sporodochia on CLA and no chlamydospores were found.

The FCSC now includes nine phylo-species, for which eight were provided with Latin binomials in this study. Although subtle morphological differences could be found among these eight newly named taxa, phylogenetic inference using the recommended Fusarium identification gene regions rpb1, rpb2 and tef1 should be used for accurate identification (O’Donnell et al. 2015).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the technical staff, A. van Iperen, D. Vos-Kleyn and Y. Vlug for their valuable assistance with cultures.

REFERENCES

- Al-Hatmi AMS, Hagen F, Menken SBJ, et al. (2016). Global molecular epidemiology and genetic diversity of Fusarium, a significant emerging group of human opportunists from 1958 to 2015. Emerging Microbes & Infections 5: e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki T, Vaughan MM, McCormick SP, et al. (2015). Fusarium dactylidis sp. nov., a novel nivalenol toxin-producing species sister to F. pseudograminearum isolated from orchard grass (Dactylis glomerata) in Oregon and New Zealand. Mycologia 107: 409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azor M, Gené J, Cano J, et al. (2009). Less-frequent Fusarium species of clinical interest: correlation between morphological and molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 47: 1463–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth C. (1971). The genus Fusarium. Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew, Surrey, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Brown DW, Proctor RH. (2016). Insights into natural products biosynthesis from analysis of 490 polyketide synthases from Fusarium. Fungal Genetics and Biology 89: 37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess LW, Forbes GA, Windels C, et al. (1993). Characterization and distribution of Fusarium acuminatum subsp. armeniacum subsp. nov. Mycologia 15: 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess LW, Summerell BA. (1992). Mycogeography of Fusarium: survey of Fusarium species in subtropical and semi-arid grassland soils from Queensland, Australia. Mycological Research 96: 780–784. [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Verkley GJM, Groenewald JZ, et al. (eds) (2019). Fungal Biodiversity. Westerdijk Laboratory Manual Series. Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Davari M, Wei SH, Babay-Ahari A, et al. (2013). Geographic differences in trichothecene chemotypes of Fusarium graminearum in the northwest and north of Iran. World Mycotoxin Journal 6: 137–150. [Google Scholar]

- Du YX, Chen FR, Shi NN, et al. (2017). First report of Fusarium chlamydosporum causing banana crown rot in Fujian Province, China. Plant Disease 101: 1048. [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht MC, Smit WA, Knox-Davies PS. (1983). Damping-off of rooibos tea, Aspalathus linearis. Phytophylactica 15: 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher NL, Burgess LW, Toussoun TA, et al. (1982). Carnation leaves as a substrate and for preserving cultures of Fusarium species. Phytopathology 72: 151–153. [Google Scholar]

- Fugro PA. (1999) A new disease of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) in India. Journal of Mycology and Plant Pathology 29: 264. [Google Scholar]

- Geiser DM, Jiménez-Gasco M, del M, Kang S, et al. (2004). FUSARIUM-ID v. 1.0: A DNA sequence database for identifying Fusarium. European Journal of Plant Pathology 110: 473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach W. (1977). Drei neue varietäten von Fusarium merismoides, F. larvarum und F. chlamydosporum. Phytopathologische Zeitschrift 90: 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach W, Nirenberg H. (1982). The genus Fusarium – a pictorial atlas. Mitteilungen aus der Biologischen Bundesanstalt für Land- und Forstwirtschaft Berlin-Dahlem 209: 1–406. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis DM, Bull JJ. (1993). An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Systematic Biology 42: 182–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kanaan YM, Bahkali AH. (1993). Frequency and cellulolytic activity of seed-borne Fusarium species isolated from Sausi Arabian cereal cultivars. Zeitschrift fuür Pflanzenkrankheiten und Pflanzenschutz 100: 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD. (2017). MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Briefings in Bioinformatics doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, et al. (2012). Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28: 1647–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn TE, Nelson PE, Bernard EM, et al. (1985). Catheter-associated fungemia caused by Fusarium chlamydosporum in a patient with lymphocytic lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 21: 501–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov AM, Darriba D, Flouri T, et al. (2018). RaxML-NG: A fast, scalable, and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. bioRxiv doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/447110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger EK, Della Torre PK, Martin P, et al. (2004). Concurrent Fusarium chlamydosporum and Microsphaeropsis arundinis infections in a cat. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 6: 271–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurence MH, Walsh JL, Shuttleworth LA, et al. (2016). Six novel species of Fusarium from natural ecosystems in Australia. Fungal Diversity 77: 349–366. [Google Scholar]

- Lazreg F, Belabid L, Sanchez J, et al. (2013). First report of Fusarium chlamydosporum causing damping-off disease on Aleppo pine in Algeria. Plant Disease 97: 1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie JF, Summerell BA. (2006). The Fusarium Laboratory Manual. Blackwell Publishing, Ames. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard L, Sandoval-Denis M, Lamprecht S, et al. (2019). Epitypification of Fusarium oxysporum – clearing the taxonomic chaos. Persoonia 43: 1–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marasas WFO, Nelson PE, Toussoun TA. (1984). Toxigenic Fusarium species: Identity and mycotoxicology. The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Marasas WFO, Rheeder JP, Logrieco A, et al. (1998). Fusarium nelsonii and F. musarum: Two new species in section Arthrosporiella related to F. camptoceras. Mycologia 90: 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Martino P, Gastaldi R, Raccah R, et al. (1994). Clinical patterns of Fusarium infections in immunocompromised patients. Journal of Infection 28: 7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathivanan N, Kabilan V, Murugesan K. (1998). Purification, characterization, and antifungal activity of chitinase from Fusarium chlamydosporum, a mycoparasite to groundnut rust, Puccinia arachidis. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 44: 646–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirenberg HI. (1976). Unterschungen über die morphologische und biologische Differenzierung in der Fusarium-Sektion Liseola. Mitteilungen der Biologischen Bundesanstalt für Land- und Forstwirtschaft Berlin-Dahlem 169: 1–117. [Google Scholar]

- Nirenberg HI. (1990). Recent advances in the taxonomy of Fusarium. Studies in Mycology 32: 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Nylander JAA. (2004). MrModeltest v. 2. Programme distributed by the author. Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Sarver BAJ, Brandt M, et al. (2007). Phylogenetic diversity and microsphere array-based genotyping of human pathogenic fusaria, including isolates from the multistate contact lens-associated U.S. keratitis outbreaks of 2005 and 2006. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 45: 2235–2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Gueidan C, Sink S, et al. (2009). A two-locus DNA sequence database for typing plant and human pathogens within the Fusarium oxysporum species complex. Fungal Genetics and Biology 46: 936–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Humber RA, Geiser DM, et al. (2012). Phylogenetic diversity of insecticolous fusaria inferred from multilocus DNA sequence data and their molecular identification via FUSARIUM-ID and Fusarium MLST. Mycologia 104: 427–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Kistler HC, Cigelnik E, et al. (1998). Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing Panama disease of banana: Concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95: 2044–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Kistler HC, Tacke BK, et al. (2000). Gene genealogies reveal global phylogeographic structure and reproductive isolation among lineages of Fusarium graminearum, the fungus causing wheat scab. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97: 7905–7910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, McCormick SP, Busman M, et al. (2018). Marasas et al. 1984 “Toxigenic Fusarium species: Identity and mycotoxicology” revisited. Mycologia 110: 1058–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Rooney AP, Proctor RH, et al. (2013). Phylogenetic analyses of RPB1 and RPB2 support a middle Cretaceous origin for a clade comprising all agriculturally and medically important fusaria. Fungal Genetics and Biology 52: 20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Sutton DA, Rinaldi MG, et al. (2009). Novel multilocus sequence typing scheme reveals high genetic diversity of human pathogenic members of the Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti and F. chlamydosporum species complexes within the United States. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 47: 3851–3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Sutton DA, Rinaldi MG, et al. (2010). Internet-accessible DNA sequence database for identifying fusaria from human and animal infections. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 48: 3708–3718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Ward TJ, Robert VARG, et al. (2015). DNA sequence-based identification of Fusarium: Current status and future directions. Phytoparasitica 43: 583–595. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor RH, McCormick SP, Alexander NJ, et al. (2009). Evidence that a secondary metabolic biosynthetic gene cluster has grown by gene relocation during evolution of the filamentous fungus Fusarium. Molecular Microbiology 74: 1128–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol I, Guarro J, Gené J, et al. (1997). In vitro antifungal susceptibility of clinical and environmental Fusarium spp. strains. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 39: 163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, He H, Li N, et al. (2010). Isolation and characterization of a thermostable cellulase-producing Fusarium chlamydosporum. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 26: 1991–1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rabie CJ, Lübben A, Louw AI, et al. (1978). Moniliformin, a mycotoxin from Fusarium fusarioides. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 26: 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabie CJ, Marasas WFO, Thiel PG, et al. (1982). Moniliformin production and toxicity of different Fusarium species from southern Africa. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 43: 517–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner RW. (1970). A mycological colour chart. CMI and British Mycological Society, Kew, Surrey, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Reinking OA, Wollenweber HW. (1927). Tropical fusaria. The Philippine Journal of Science 32: 103–253. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha LO, Laurence MH, Proctor RH, et al. (2015). Variation in type A trichothecene production and trichothecene biosynthetic genes in Fusarium goolgardi from natural ecosystems of Australia. Toxins 7: 4577–4594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. (2003). MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19: 1572–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangalang AE, Burgess LW, Backhouse D, et al. (1995). Mycogeography of Fusarium species in soils from tropical, arid and Mediterranean regions of Australia. Mycological Research 99: 523–528. [Google Scholar]

- Satou M, Ichinoe M, Fukumoto F, et al. (2001). Fusarium blight of kangaroo paw (Anigozanthos spp.) caused by Fusarium chlamydosporum and Fusarium semitectum. Journal of Phytopathology 149: 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Savard ME, Miller JD, Salleh B, et al. (1990). Chlamydosporol, a new metabolite from Fusarium chlamydosporum. Mycopathologia 110: 177–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal BH, Walsh TJ, Liu JM, et al. (2009). Invasive infection with Fusarium chlamydosporum in a patient with aplastic anemia. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 36: 1772–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumya K, Murthy KN, Sreelatha GL, et al. (2018). Characterization of a red pigment from Fusarium chlamydosporum exhibiting selective cytotoxicity against human breast cancer MCF-7 cell lines. Journal of Applied Microbiology 125: 148–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkey DE, Ward TJ, Aoki T, et al. (2007). Global molecular surveillance reveals novel Fusarium head blight species and trichothecene toxin diversity. Fungal Genetics and Biology 44: 1191–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. (2003). PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), v. 4.0b10. Computer programme. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Waalwijk C, Taga M, Zheng S-L, et al. (2018). Karyotype evolution in Fusarium. IMA Fungus 9: 13–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MM, Chen Q, Diao YZ, et al. (2019). Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti complex in China. Persoonia 43: 70–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z-F, Zhang W, Xiao L, et al. (2018). Characterization and bioactive potentials of secondary metabolites from Fusarium chlamydosporum. Natural Product Research DOI: 10.1080/14786419.2018.1508142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollenweber HW, Reinking OA. (1925). Aliquot fusaria tropicalia nova vel revisa. Phytopathology 15: 155–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wollenweber HW, Reinking OA. (1935). Die Fusarien, ihre Beschreibung, Schadwirkung und Bekampfung. Paul Parey, Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Yli-Mattila T, Ward TJ, O’Donnell K, et al. (2011). Fusarium sibiricum sp. nov., a novel type A trichothecene-producing Fusarium from northern Asia closely related to F. sporotrichioides and F. langsethiae. International Journal of Food Microbiology 147: 58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]