Abstract

Species of the genus Wynnea are collected in association with a subterranean mass generally referred to as a sclerotium. This is one of the few genera of the Sarcoscyphaceae not associated with plant material – wood or leaves. The sclerotium is composed of hyphae of both Armillaria species and Wynnea species. To verify the existence of Armillaria species in the sclerotia of those Wynnea species not previously examined and to fully understand the structure and nature of the sclerotium, molecular data and morphological characters were analyzed. Using nuclear ITS rDNA sequences the Armillaria species co-occurring with Wynnea species were identified from all examined material. These Armillaria symbionts fall into two main Armillaria groups – the A. gallica-nabsnona-calvescens group and the A. mellea group. Divergent time estimates of the Armillaria and Wynnea lineages support a co-evolutionary relationship between these two fungi.

Keywords: Armillaria, symbiosis, sclerotium, Wynnea

INTRODUCTION

Sclerotia are dense aggregations of tissue produced by some fungi. The distribution of sclerotia across the Fungi has been reviewed by Smith et al. (2015). It is assumed that sclerotia aid in survival of fungi under challenging environmental conditions (Smith et al. 2015, Willetts 1971) and in some cases the sclerotia directly or indirectly provide carbohydrates to support subsequent growth of spore producing structures. Sclerotia-forming fungi are found among ecologically and phylogenetically diverse groups of fungi. In the Pezizales, only a few species have been reported to produce sclerotia (Smith et al. 2015).

Sclerotia of species of the genus Wynnea (Ascomycota, Pezizales, Sarcoscyphaceae) were first reported by Thaxter (1905), who mentioned that ascomata of species of W. americana arose from a mass of fungal tissue that he referred to as a sclerotium. Kar & Pal (1970) and Waraitch (1976) reported that collections from India of W. macrotis arose from buried sclerotia. Bosman (1998) described irregular, stellate sclerotia in W. sparassoides and Zhuang (2003) mentioned irregularly-shaped sclerotia in some collections of W. macrospora. Similar structures were observed in collections of W. gigantea from Brazil. All recognized species have been found with sclerotial structure except for W. sinensis. In this case the lack of sclerotia is likely due to it being overlooked when collecting apothecia.

Among the Sarcoscyphaceae these species of Wynnea, along with species of Geodina, are the only taxa seemingly not associated with woody plant material or leaves (Denison 1965, Pfister 1979, Li & Kimbrough 1996, Angelini et al. 2018). Berkeley listed wood as the substrate in the original description of W. macrotis but this likely is the result of faulty collection information (Pfister 1979).

The ecological and life history function of these sclerotia has not been addressed. Thaxter (1905) speculated that its purpose may be to supply moisture and nutriment to the developing apothecia. The nature of the sclerotium has been questioned since Thaxter’s day. Nagasawa (1984) first reported that Armillaria species were associated with sclerotia of W. gigantea (probably either W. macrotis or W. sinensis based on our studies) and this association was confirmed further by Fukuda et al. (2003) who detected A. cepistipes in sclerotia of W. americana using molecular methods. This refers most probably to W. macrospora based on our unpublished phylogenetic study. The co-occurrence of Armillaria species with the Wynnea species to form these sclerotial masses suggests a complex interaction.

The present study was initiated to determine whether this Armillaria – Wynnea association was present across all Wynnea species. We used nuclear rDNA ITS sequences to identify the Armillaria species associated with sclerotia from five Wynnea species. The symbiotic relationship between Wynnea species and their respective Armillaria symbionts was examined using molecular phylogenetic analyses of nuclear 18S, 28S and ITS rDNA sequences for Wynnea and ITS for Armillaria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling

The source of Armillaria symbionts (whether from sclerotia, basidiomata or fungal cultures) with voucher information and GenBank accession numbers are given in Table 1. The GenBank sequences of those Armillaria species that are not associated with sclerotia that were included in this study are also presented in Table 1. Eleven herbarium specimens from five Wynnea species were included in the molecular phylogenetic analyses. Table 2 lists GenBank numbers for the sequences derived from ascomata.

Table 1.

Collections used in the molecular phylogenetic analyses, with voucher information and GenBank accession numbers. The * indicates the DNA sequence was derived from sclerotia of the respective taxa. New GenBank numbers are in bold.

| Species | Strain or specimen no. | Origin | Source tissue | ITS GenBank accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armillaria sp. | FH 00445985 | West Virginia USA | Wynnea americana* | MK271361 |

| FH 00445981 | New York, USA | Wynnea americana* | MK271360 | |

| CUP 063481 | New York, USA | Wynnea americana* | MK271359 | |

| F C0239599 | Costa Rica | Wynnea americana* | MK271358 | |

| F C0240179 | Pennsylvania, USA | Wynnea americana* | MK271357 | |

| FH s. n. | Brazil | Wynnea gigantea* | MK271362 | |

| FH ACM624 | Brazil | Wynnea gigantea* | MK281619 | |

| NYBG 00449607 | Guatemala | Wynnea gigantea* | MK281620 | |

| FH 00445975 | Guizhou Prov., China | Wynnea macrospora* | MK281621 | |

| FH 00940720 | China | Wynnea macrospora* | MK599142 | |

| CUP 2684 | Japan | Wynnea macrotis* | MK281622 | |

| NYBG 02480090 | West Virginia USA | Wynnea sparassoides* | MK281623 | |

| JLF1498b | Virginia, USA | Entoloma abortivum | FJ940731 | |

| A. calvescens | ST17A | Michigan, USA | Basidioma | AY213560 |

| ST3 | Quebec, Canada | Basidioma | AY213559 | |

| ST17B | Michigan, USA | Basidioma | AY213561 | |

| ST18 | Michigan, USA | Basidioma | AY213562 | |

| A. cepistipes | S20 | British Columbia, Canada | Basidioma | AY213582 |

| M110 | British Columbia, Canada | Basidioma | AY213581 | |

| W113 | Washington, USA | Basidioma | AY213583 | |

| A. gallica | ST22B | Michigan, USA | Basidioma | AY213570 |

| ST22A | Michigan, USA | Basidioma | AY213569 | |

| ST23 | Wisconsin, USA | Basidioma | AY213571 | |

| NA17 | Japan | - | AB510872 | |

| NBRC31621 | Japan | Galeola sp. | AB716752 | |

| HKAS85517 | Xinjiang Prov., China | Basidioma | KT822312 | |

| HKAS51692 | Sichuan Prov., China | Basidioma | KT822269 | |

| A. gallica (China3) | s. n. | Ji’an, China | Polyporus umbellatus* | KP162334 |

| A. gallica (China4) | s. n. | Lijiang, China | Polyporus umbellatus* | KP162319 |

| A. gemina | ST8 | New York, USA | Basidioma | AY213555 |

| ST11 | West Virginia, USA | Basidioma | AY213558 | |

| ST9B | New York, USA | Basidioma | AY213557 | |

| ST9A | New York, USA | Basidioma | AY213556 | |

| A. mellea | ST5B | Virginia, USA | Multisporous | AY213585 |

| ST5A | Virginia, USA | Multisporous | AY213584 | |

| ST21 | New Hampshire, USA | Multisporous | AY213587 | |

| ST20 | Wisconsin, USA | Basidioma | AY213586 | |

| HKAS86588 | Japan | Single Spore | KT822246 | |

| TNS-F-70421 | Yamagata, Oguni, Japan | - | MF095794 | |

| MEX100 | Estado de Mexico, Coatepec Harinas, Mexico | - | JX281808 | |

| A. nabsnona | C21 | Idaho, USA | Basidioma | AY509175 |

| ST16 | Alaska, USA | Multisporous | AY509178 | |

| A. ostoyae | ST2 | Washington, USA | Basidioma | AY213553 |

| ST1 | New Hampshire, USA | Multisporous | AY213552 | |

| 2002_66_03 | Japan | - | AB510896 | |

| 89_03B_09 | Japan | - | AB510861 | |

| HKAS86580 | Jilin Prov., China | Single Spore | KT822311 | |

| A. ostoyae (China1) | s. n. | Hailin, China | Polyporus umbellatus* | KP162333 |

| A. ostoyae (China5) | s. n. | A’ba, China | Polyporus umbellatus* | KP162328 |

| A. puiggarrii | PPg 85-63.1 | Mexico | - | FJ664608 |

| A. sinapina | ST13B | Michigan, USA | Multisporous | AY509170 |

| ST12 | Washington, USA | Basidioma | AY509169 | |

| ST13A | Michigan, USA | Multisporous | AY509169 | |

| A. sinapina (Japan1) | ArHA1 | Takausutyou Asahikawa, Hokkaido, Japan | Polyporus umbellatus* | AB300716 |

| A. sinapina (Japan2) | ArHH1 | Sanbusigaiti Hurano, Aza Hokkaido, Japan | Polyporus umbellatus* | AB300717 |

| A. sinapina (Japan3) | ArSF1 | Fujinomiya city, Shizuoka Pref., Japan | Polyporus umbellatus* | AB300718 |

| A. sinapina (China2) | ArHe1 | Henan Prov., China | Polyporus umbellatus* | AB300721 |

| A. sinapina (China6) | ArST1 | Shaanxi Prov., China | Polyporus umbellatus* | AB300719 |

| A. sinapina (China7) | ArSB1 | Shaanxi Prov., China | Polyporus umbellatus* | AB300720 |

| Desarmillaria tabescens | 00i-99 | Georgia, USA | - | AY213590 |

| 00i-210 | Georgia, USA | - | AY213589 | |

| At-Mu.S2 | South Carolina, USA | - | AY213588 |

Table 2.

Collections used in the molecular phylogenetic analyses in Fig. 2, with voucher information and GenBank accession numbers.

| Species | Fungarium/Collection | Geographic origin, year and collector |

GenBank accession no. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSU | ITS | LSU | |||

| Wynnea americana | FH 00445985 | USA, WV, 1977, H. Barnhart | MK335789 | MK335780 | MK335799 |

| F C0239599 | Costa Rica, 1993, G.M. Mueller (4561) | MK335788 | MK335779 | MK335800 | |

| FH 00445978 | NY, USA, no date, K. T. Hodge | MK592785 | MK599141 | MK599148 | |

| NYBG 02480091 | PA, USA, 1907, O.E. Jennings | - | - | MK599149 | |

| Wynnea gigantea | FH s. n. | Brazil, 1993, R.T. Guerreiro & R.M.B. Silverira | MK335790 | MK335781 | MK335801 |

| FH ACM624 | Brazil, 2013, A.C. Magnago | MK335791 | MK335782 | MK335802 | |

| NYBG 00449607 | Guatamala, 1971, A.L. Welden | MK335792 | MK335783 | - | |

| Wynnea macrospora | FH 00445975 | China, Guizhou,1984, M.H. Liu | MK335793 | MK335784 | MK335803 |

| FH 00940720 | China, Suchuan, 1997, D.S. Hibbet & Z. Wang | MK335794 | MK335785 | - | |

| Japan, 1963, K. Tubaki | |||||

| Wynnea macrotis | CUP 2684 | MK335795 | MK33578 | MK335804 | |

| Wynnea sparassoides | NYBG 02480090 | WV, USA, 1982, C.T. Rogerson | MK335796 | MK335787 | MK335805 |

DNA isolation

To isolate DNA of the symbiont a small piece from the central part of sclerotium was excised from dried herbaria specimen and ground in an Eppendorf tube using a Fastprep FP120 Cell Disruptor (BIO101, CA, USA). Genomic DNA was isolated using the DNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, Germantown, Maryland) according to the modified protocol of Costa & Roberts (2014). This method also was used for DNA isolation from ascomata of the five Wynnea species. An alternative method, as follows, was used to isolate DNA from suspected hyphae of Armillaria species. Small pieces of hyphae from the chambers of sclerotia of W. americana (F C0239599) and W. sparassoides (NYBG 02480090 ) were picked out under a microscope and placed in PCR tubes. DNA was extracted by an Extract-N-Amp Plant PCR kit (Sigma-Aldrich) following Haelewaters et al. (2015).

PCR and sequencing

The ITS rDNA regions of Armillaria species were amplified using the Armillaria-specific primers ARM1 and ARM2 (Schulze et al. 1997) or AR1 and AR2 (Lochman et al. 2004). For material that proved to be problematic, internal primers ITS2 and ITS3 (White et al. 1990) were employed. Ascomatal samples of Wynnea species were amplified for SSU, LSU, and ITS. The SSU region was amplified using primers NS1, NS2, NS4, NS8 (White et al. 1990), SL122 and SL344 (Landvik et al. 1996). The 5′ end of the LSU rDNA region was amplified using the primers LR0R, LR5, LR3 and LR3R (Moncalvo et al. 2000; http://www.biology.duke.edu/fungi/mycolab/primers.htm). Amplification of the ITS region used the primers ITS1F (Gardes & Bruns 1993), ITS2, ITS3 and ITS4 (White et al. 1990). Wynnea-specific ITS primers (forward primer ITS1-WYF (5′-GATCATTRGCCGARAGCG-3′) located in ITS1 region and reverse primer ITS4-WYR (5′-CACGGTCGGM CRCGRRCG-3′) or ITS4-WYR2 (5′-GATATGCTTAAGTTCAGCGG-3′) located in ITS2 region were developed and employed.

For each 25 μL PCR reaction 2 μL of diluted genomic DNA (1/10 and 1/100 dilutions) and 1.25 μL DMSO was included. The SSU, LSU and ITS rDNA were amplified using Econo Taq DNA polymerase (Lucigen, Middleton, WI). A modified touch-down PCR program was used with cycling parameters as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 10 cycles including denaturation at 95 °C for 60 s, annealing at 62 °C (decreasing 1 °C each cycle or every three cycles) for 60 s and extension at 72 °C for 60 s, then 35 cycles with denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 52 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 60 s, final extension at 72 °C for 7 min and hold at 12 °C. All PCR reactions were done in a Peltier Thermal cycler PTC-200 (MJ research, Watertown, MA). PCR products were purified either directly or after band excision using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Germantown, Maryland) or Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen, Germantown, Maryland), and then sequenced as described in Hansen et al. (2005). Sequencher v. 4.6 (GeneCodes, Ann Arbor, Michigan) was used to edit and assemble the DNA sequences obtained.

Sequence analysis

Alignments of the Armillaria and Wynnea sequences were done using the MAFFT webserver (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server, Katoh & Standley 2013) with the default settings, and then manually optimized in MEGA v. 6.0 (Tamura et al. 2013) as necessary. The full alignment is available from TreeBASE under accession no. 23751. The best-fit evolutionary model for each dataset was determined using jModelTest v. 0.1 (Posada 2008). Phylogenetic trees and support values were determined from Bayesian inference analyses using MrBayes v. 3.1.2 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003) and Maximum-Likelihood (ML) analyses using RAxML-HPC2 on Abe through the Cipres Science Gateway (www.phylo.org; Miller et al. 2010). Clade robustness was assessed using a bootstrap (BS) analyses with 1 000 replicates (Felsenstein 1985). Branches that received Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP) and bootstrap support for ML (ML-BS) greater than or equal to 0.95 of BPP and 80 % of ML-BS were considered as significant. Flammulina velutipes (GenBank #EF595854) and Hymenopellis radicata (GenBank #DQ241780) were used as the outgroup species in the phylogenetic analyses of the Armillaria species and Cookeina tricholoma (SSU:AF006311; LSU:AY945860; ITS:KY649459) and Microstoma floccosum (SSU:AF006313; LSU:DQ220370;ITS: AF394046) were used in the Wynnea analyses.

Divergence time estimation

Divergence time estimates for the Armillaria and Wynnea lineages used the ITS DNA sequence data set from the molecular phylogenetic analyses (Table 1, Fig. 1). The secondary calibration strategy implemented by Renner (2005) was applied here to infer the time to Most Recent Common Ancestor (tMRCA). Molecular dating from Koch et al. (2017) indicated the initial radiation of the genus Armillaria to be 50.81 MYA. We applied this node age to calibrate the same node in our analysis. The BEAST v. 1.8.2 (Drummond et al. 2012) software package was used for both initial and secondary tMRCA analyses. The following parameter settings were used: (i) GTR+G model was chosen as the best substitution model by jModelTest; (ii) a relaxed lognormal model (Ree & Smith 2008) was employed for molecular clock analysis; (iii) tree prior was set to Yule speciation; (iv) the length of Markov Chain was set to 50 M generations with parameters sampled every 1 000 generations. A burn-in value of 10 % was selected in Tracer v. 1.6 (Drummond et al. 2012) where the Effective Sample Size (ESS) was >200 and convergence among runs was reached. Two independent Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analyses were performed for each analysis. After discarding the burn-in and combination using LogCombiner v. 1.8.2 (in BEAST v. 1.8.2 package), Tracer v. 1.6 (Drummond et al. 2012) was used to calculate the mean, upper and lower bounds of the 95 % highest posterior density interval (95 % HPD) for divergence times. Tree topologies were interpreted in Treeannotator (in BEAST v. 1.8.2 package) and viewed in FigTree v. 1.4.2 (Rambaut 2008).

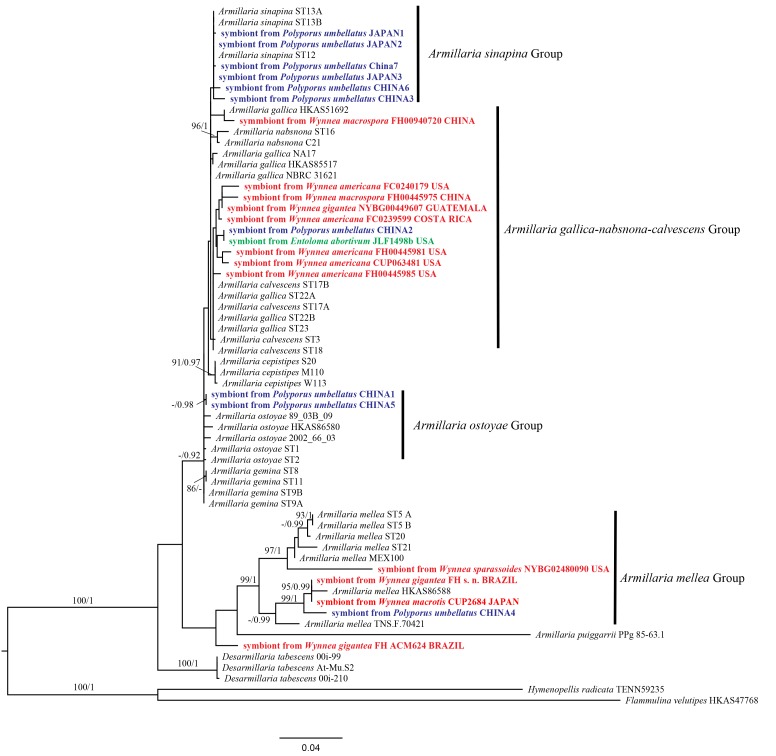

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationships among symbionts from sclerotia of Wynnea species and species of Armillaria. The tree topology was inferred from analysis of ITS rDNA sequence data using Maximum Likelihood (ML) methods. Hymenopellis radicata and Flammulina velutipes were used as outgroups. The branch support values are indicated on the branches, as ML bootstrap ≥ 80 % and Bayesian posterior probabilities ≥ 0.95 respectively.

Morphological examination of the sclerotia

Dried specimens were prepared for microscopic examination by rehydrating a small portion of sclerotium in water for at least two hours. The sample was sectioned with median sections 25 to 30 μm thick using a freezing microtome. Sections were placed on a microscope slide and mounted in water.

RESULTS

Molecular identification of Armillaria sp. associated with Wynnea sp.

The ITS rDNA sequences from Wynnea sclerotia were identified as species of Armillaria based on DNA sequence similarity searching methods with BLAST (NCBI, https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). As shown in Fig. 1 all of the Wynnea symbionts analyzed belong to the genus Armillaria and were associated with one of two main Armillaria groups: the A. gallica-nabsnona-calvescens group or the A. mellea group. All symbionts from W. americana and W. macrospora were placed in the A. gallica-nabsnona-calvescens group while those from W. macrotis and W. sparassoides fell into the A. mellea group (supported by 0.99 BPP). Of the three symbionts from W. gigantea, FH s.n. from Brazil was associated with the A. mellea group but the symbiont from the Guatemala collection belonged to the A. gallica-nabsnona-calvescens group (Fig. 1). A second Brazilian collection (FH ACM624) represents an independent lineage outside of the A. mellea group.

There was no correlation between sequence similarity of the Wynnea symbionts and their geographic origin (Fig. 1). The symbiont from Eastern Asia W. macrospora (FH 00445975, China) showed highest similarity to the symbiont from Eastern North America (symbiont from W. americana FC 0240179). The symbiont of W. macrotis from Japan (CUP 2684) was more closely related to symbionts of W. gigantea from South America (FH s. n. and FH ACM624, Brazil) and W. sparassoides from USA (NYBG 02480090).

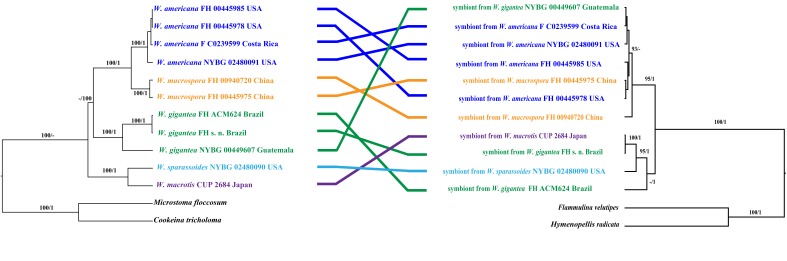

Symbiotic relationship between Armillaria and Wynnea

When compared with the phylogenetic tree of Wynnea inferred from combined nuclear SSU, ITS and LSU sequences, significant relationships between Wynnea and Armillaria were revealed (Fig. 2). In the phylogenetic tree of Wynnea, the 4 specimens of W. americana, from eastern North America and Costa Rica, were sister to the two W. macrospora specimens from eastern Asia. The symbionts from each of these species pairs were all shown to belong to the A. gallica-nabsnona-calvescens group. The same situation was found in another phylogenetically related species pair, W. sparassoides from eastern North America and W. macrotis, from eastern Asia. Symbionts from this species pair belong to the A. mellea group. In contrast, the three symbionts from W. gigantea were placed in three different lineages; the W. gigantea s. n. symbiont from Brazil was placed in the A. mellea group, the symbiont from the Guatemalan collection of W. gigantea was in the A. gallica-nabsnona-calvescens group and the Brazilian collection, FH ACM624 was in an independent lineage (Figs 1 and 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of phylogenetic trees of Wynnea and Armillaria species indicating co-evolutionary relationships. Left: Phylogeny of Wynnea produced from Bayesian analysis based on combined SSU, ITS and LSU rDNA sequences with Cookeina tricholoma and Microstoma floccosum as outgroups. Right: Phylogeny of Armillaria produced from Bayesian analysis based on ITS rDNA sequences with Flammulina velutipes and Hymenopellis radicata as outgroups. The branch support values from the analyses are indicated on the branches, as Maximum Likelihood bootstrap ≥ 80 % and Bayesian posterior probabilities ≥ 0.95 respectively. Lines between the two phylogenetic trees indicate the symbiont from a sclerotium and the corresponding apothecium.

Divergence time estimation

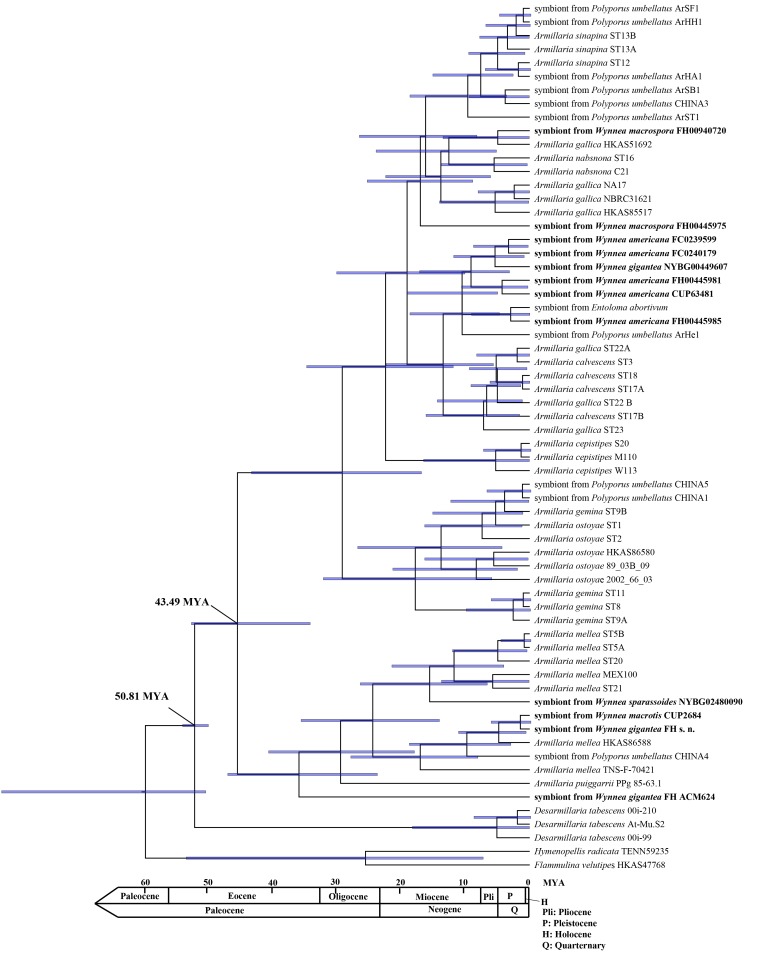

The age of the ancestor of the genus Armillaria was estimated at 50.81 MYA by Koch et al. (2017) for the armillarioid clade. This largely is in agreement with the results of Coetzee et al. (2011). Based on this age, an ITS DNA sequence dataset consisting of species within the genus Armillaria, including those now placed in the genus Desarmillaria, and symbionts from Wynnea species was constructed and analyzed for divergence time estimations. The divergence time of the A. mellea group was estimated as 43.49 MYA (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Chronogram and estimated divergence times of Armillaria generated from molecular clock analysis using the ITS DNA sequence data. Chronogram obtained from BEAST using the Armillaria divergence time, 50.81 MYA, from Koch et al. (2017) as the calibration point. The divergence time of the A. mellea group is estimated at 43.49 MYA. Blue bars denote the 95 % highest posterior density (HPD) intervals of the posterior probability distribution of node ages.

Morphological and molecular examination of the sclerotial structure

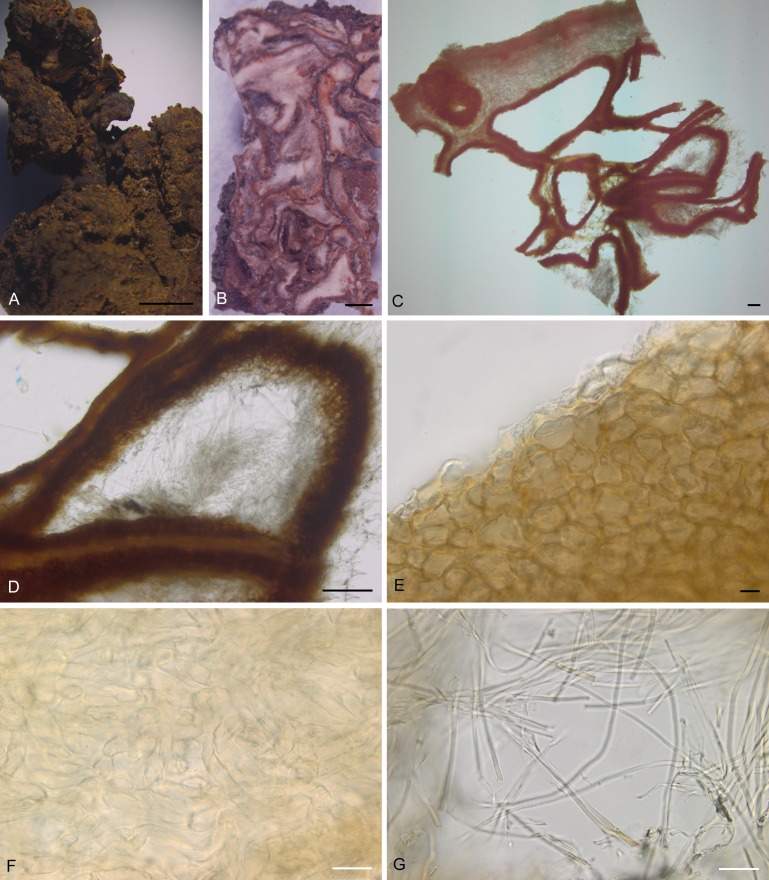

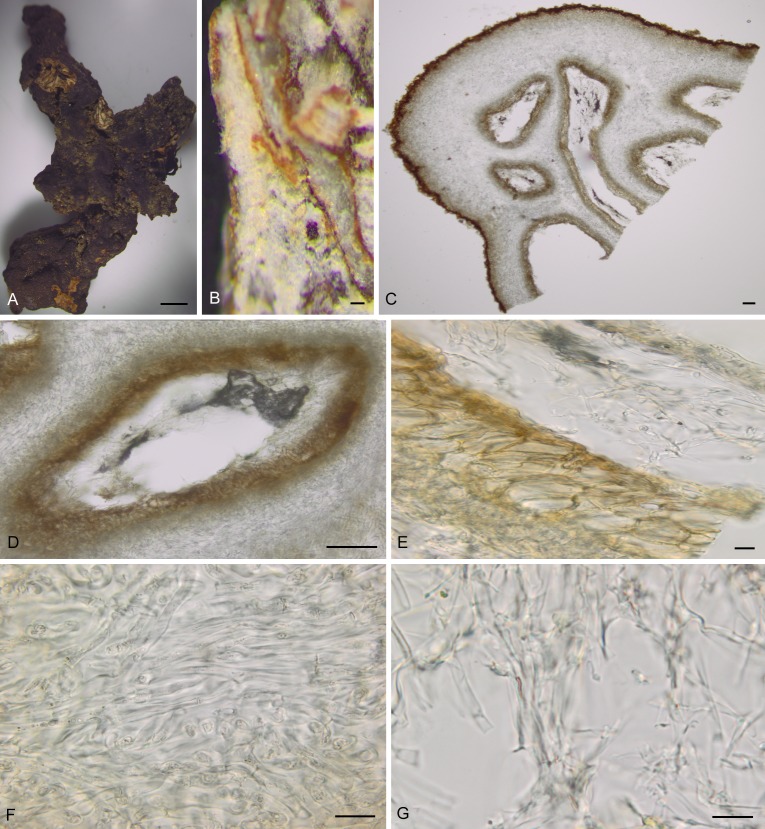

Sections were made from the sclerotia of W. americana Costa Rica collection (F C0239599) and W. sparassoides WV-USA collection (NYBG 02480090) (Figs 4A and 5A) and chambers were observed in sclerotia of these two species (Figs 4B–D, 5B–D). Detailed examination of the structure of the chambers showed that the outer layers (Figs 4E, 5E) resemble the outer excipulum of the apothecia and the inner layers (Figs 4F, 5F) resemble the medullary excipulum of the apothecia, indicating that these two parts of the sclerotia were likely derived from the Wynnea.

Fig. 4.

Morphological characters of Wynnea americana (F C0239599). A. Partial view of a sclerotium. B. Internal part of sclerotium. C. Cross section of a sclerotium, freezing microtome section at 30 μm. D. Chambered structure. E. Outer layer of the chambered structure. F. Inner layer of the chambered structure. G. Whitish hyphae in the chamber. Bars: A, B = 0.5 mm; C, D = 100 μm; E–G = 10 μm. All mounted in water.

Fig. 5.

Morphological characters of Wynnea sparassoides (NYBG 02480090). A. Partial view of a sclerotium. B. Internal part of sclerotium. C. Cross section of a sclerotium, freezing microtome section at 30 μm. D. Chambered structure. E. Outer layer of the chambered structure. F. Inner layer of the chambered structure. G. Whitish hyphae in the chamber. Bars: A, B = 0.5 mm; C, D = 100 μm; E, F, and G = 10 μm. All mounted in water.

Within the chamber, there were tangles of thin hyphae, about 1 μm wide and whitish (Figs 4G, 5G). Using the specific PCR primers for Armillaria indicated that these hyphae in the chambers were those of Armillaria species.

Rhizomorphs were also directly observed in the sclerotia of W. americana (NY-USA, CUP 063481 and Costa Rica, F C0239599) and W. sparassoides (WV-USA, NYBG 02480090). Figures 4A and 5A show that these rhizomorphs penetrate into the sclerotia. BLAST results of the ITS sequences amplified from rhizomorphs showed these rhizomorphs were from Armillaria species.

DISCUSSION

Ecology of Armillaria and relationship with other fungi

Species of the basidiomycete genus Armillaria are an important component of the fungi in forest ecosystems worldwide where they are responsible for root rot disease (Tsykun et al. 2012). At present, about 70 Armillaria species are known (Volk & Burdsall 1995). The individual Armillaria species differ in ecological behavior, geographical distribution and host preference (Shaw & Kile 1991). Based on data from France, England and Italy, Guillaumin et al. (1993) characterized 142 species from 30 plant families as hosts of Armillaria species. This indicates both high diversity and interactions of Armillaria species.

Armillaria species can act as either host or parasite in interactions with other fungi (Baumgartner et al. 2011). Choi et al. (2002) reported that the sclerotia of Polyporus umbellatus (as Grifola umbellata) had a symbiotic relationship with A. mellea. Kikuchi & Yamaji (2010) indicated that all the sclerotial samples of P. umbellatus had rhizomorphs of Armillaria species adherent to and penetrating them. In order to compare our findings with those of P. umbellatus, we included ITS sequences of Armillaria sp. (Table 1) from the sclerotia of P. umbellatus collected in Japan and China (Kikuchi & Yamaji 2010). As shown in Fig. 1 the P. umbellatus symbionts fell into four Armillaria groups: A. sinapina, A. gallica-nabsnona-calvescens, A. ostoyae and A. mellea. The symbionts from W. americana, W. macrospora and the W. gigantea the collection from Guatemala (Fig. 1) also fell within the A. gallica-nabsnona-calvescens group. Species identification of the symbionts in the A. gallica-nabsnona-calvescens group is difficult because these species are morphologically similar and their ITS rDNA sequences are not divergent enough for species assignment (Antonín et al. 2009).

In the Polyporus – Armillaria association, Armillaria was thought to be parasitic on the Polyporus host. On the other hand, Armillaria was reported to be parasitized by Entoloma abortivum (Basidiomycota, Entolomataceae), which caused misshapen Armillaria fruiting bodies, carpophoroids (Czederpiltz et al. 2001). In our study, we also included one Armillaria ITS sequence from the Entoloma association and results indicated that the Armillaria associated with Entoloma was also placed in the A. gallica-nabsnona-calvescens group.

Armillaria mellea was found to be the symbionts of W. sparassoides, W. macrotis and W. gigantea sclerotia in the present study and one of the symbionts of Polyporus umbellatus (China4). These Armillaria taxa were different taxa than those found to be associated with W. americana and W. macrospora, Entoloma and the nine other Polyporus specimens included (Fig. 1). Fukuda et al. (2003) reported that A. mellea was identified from W. gigantea (probably either W. macrotis or W. sinensis according to our unpublished study) and A. cepistipes was identified from W. americana (the Japanese material of W. americana is now known to be W. macrospora), which is in accordance with our results. This broadens our knowledge of the association of Armillaria species with other fungi. In this case Wynnea species, Ascomycota, are associated with members of two Armillaria groups and mirrors the situation observed in P. umbellatus but in this case the association is across fungal phyla.

Function of sclerotia and its association with Armillaria

Sclerotia are reported to help fungi to survive challenging conditions such as extremes of temperature, desiccation, starvation and toxic chemicals (Willetts 1971, Smith et al. 2015). Many of the sclerotium-forming fungi are plant pathogens where sclerotia may function in relationship to host-parasite interaction (Coley-Smith & Cooke 1971). Sclerotia are highly variable in their morphology and putatively serve as a resource-storage (Smith et al. 2015).

The structure of the sclerotia in Wynnea species is fundamentally different than that of most sclerotia. The chambered structure of the sclerotia from W. americana was first reported and illustrated by Thaxter (1905). Korf (1972) stated that in W. americana the sclerotium was a tangled mass of rhizomorphs. Pfister (1979) also described rhizomorphs on the outside of the sclerotium in some collections of W. americana. Nagasawa (1984) presented the structure of W. gigantea (possibly W. sinensis or W. macrotis based on our unpublished phylogenetic study) showing cross sections of the sclerotia. In all of these cases the sclerotium is loosely constructed and composed of two elements. Our molecular results demonstrate that the whitish hyphae inside of the chambers and the rhizomorphic tangle outside the sclerotia are hyphae of Armillaria species. The outer surface and the walls of the chambers of the sclerotia are morphologically similar to the excipular tissues of the Wynnea ascomata.

To date, all the Wynnea species have been collected with sclerotia except W. sinensis in which it seems to have been overlooked when the ascomata were collected. In this study, Armillaria species were identified from all the sampled sclerotia using molecular phylogenetic techniques. Based on the knowledge obtained to date, we assume that W. sinensis also forms sclerotia with Armillaria species.

Wynnea gigantea seems to be the only species whose sclerotia have no chambered structure. Amplification of both Wynnea and Armillaria ITS sequences using specific primers or cloned sequences indicated that the sclerotia of W. gigantea also included Armillaria hyphae even though chambers were not formed.

Species of Wynnea and Geodina are the only genera in the family Sarcoscyphaceae that are not directly associated with wood or other plant material. The substrate association of Geodina, a fungus known from only a few collections, remains a mystery since all collections have been made from soil. The association with Armillaria explains the unique habit of Wynnea species. But the nature of the symbiosis among the species of Wynnea and Armillaria is still uncertain. Fresh samples carefully collected will be helpful to illustrate this interesting association. The ecology and life history of Wynnea species cannot be fully understood without understanding sclerotial function. We do surmise that the Wynnea species are parasitic on Armillaria species as seems to be the case in Polyporus umbellatus (Xing et al. 2017).

Sclerotia are known in other members of the Pezizomycetes. These are constructed, so far as is known, of a single fungus and are primarily assumed to be survival structures.

Divergence time estimated

Dating the divergence time of the A. mellea group based on ITS sequences was determined to be 43.49 MYA which is older than the 31 MYA divergence time estimated by Koch et al. (2017) who used a combined ITS, LSU and EF1α dataset. This might be because LSU and EF1α genes are more conserved and thus have slower evolutionary rates than that of the ITS rDNA region.

Our divergence time estimate for Wynnea species (manuscript in preparation) is 73.23 MYA and predates the 50.81 MYA Armillaria ancestor. The divergence times for the Wynnea and Armillaria species indicate that there is a deep evolutionary relationship between Armillaria species and Wynnea species. This relationship might be involved in diversification of these species.

CONCLUSIONS

The fact that all species of Wynnea, thus far known, are associated with Armillaria species points to an interwoven life history and evolution among these fungi. To date, Wynnea species, have not been found on wood or plant parts and though seemingly occurring on soil, suggestive of a mycorrhizal habit, no member of the Sarcoscyphaceae has been implicated in such mycorrhizal relationships. Although definitive answers to the question of the role of these sclerotia are not at hand, it seems likely that as in the case of Armillaria species and Polyporus umbellatus, the Wynnea species may indeed be parasitic on the Armillaria species. The fidelity of the association across taxa and geographical ranges point to a specific dependency on each other.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully thank the curators of BPI, CUP, F, HKAS, HMAS, NYBG, TNS-F for loan of collections used in this study and Genevieve E. Tocci at FH for dealing with specimens. We are especially grateful to A.C. Magnago for providing Brazilian collections. Funding for this research were provided by an NSF Grant to Donald H. Pfister (DEB-0315940), and a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 31401929) and the China Scholarship Council (CSC) to Feng Xu.

REFERENCES

- Angellini C, Medardi G, Alvarado P. (2018). Contribution to the study of neotropical discomycetes: a new species of the genus Geodina (Geodina salmonicolor sp. nov.) from the Dominican Republic. Mycosphere 9: 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Antonín V, Tomšovský M, Sedlák P, et al. (2009). Morphological and molecular characterization of the Armillaria cepistipes – A. gallica complex in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Mycological Progress 8: 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner K, Coetzee MP, Hoffmeister D. (2011). Secrets of the subterranean pathosystem of Armillaria. Molecular Plant Pathology 12: 515–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman TE. (1998). What does the red-backed vole have to do with Wynnea sparassoides and Wynnea americana in North America? McIlvainea 13: 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Choi KD, Kwon JK, Shim JO, et al. (2002). Sclerotia development of Grifola umbellata. Mycobiology 30: 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee MP, Bloomer P, Wingfield MJ, et al. (2011). Paleogene radiation of a plant pathogenic mushroom. PloS One 6: e28545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley-Smith JR, Cooke RC. (1971). Survival and germination of fungal sclerotia. Annual Review of Phytopathology 9: 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Costa CM, Roberts RP. (2014). Techniques for improving the quality and quatity of DNA extracted from herbarium specimens. Phytoeuron 48: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Czederpiltz DL, Volk TJ, Burdsall HJ. (2001). Field observations and inoculation experiments to determine the nature of the carpophoroids associated with Entoloma abortivum and Armillaria. Mycologia 93: 841–851. [Google Scholar]

- Denison WC. (1965). Central American Pezizales. I. A new genus of the Sarcoscyphaceae. Mycologia 57: 649–656. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, et al. 2012. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Molecular Biology and Evolution 29: 1969–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985). Confidence-delimitation on phylogenies - an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M, Nakashima E, Hayashi K, et al. (2003). Identification of the biological species of Armillaria associated with Wynnea and Entoloma abortivum using PCR-RFLP analysis of the intergenic region (IGR) of ribosomal DNA. Mycological Research 107: 1435–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardes M, Bruns TD. (1993). ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes – application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Molecular Ecology 2: 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaumin JJ, Mohammed C, Anselmi N, et al. (1993). Geographical distribution and ecology of the Armillaria species in western Europe. European Journal of Forest Pathology 23: 321–341. [Google Scholar]

- Haelewaters D, Gorczak M, Pfliegler WP, et al. (2015). Bringing Laboulbeniales into the 21st century: enhanced techniques for extraction and PCR amplification of DNA from minute ectoparasitic fungi. IMA Fungus 6: 363–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen K, Lobuglio K, Pfister DH. (2005). Evolutionary relationships of the cup-fungus genus Peziza and Pezizaceae inferred from multiple nuclear genes: RPB2, beta-tubulin, and LSU rDNA. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 36: 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar AK, Pal KP. (1970). The Pezizales of Eastern India. Canadian Journal of Botany 48: 145–146. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi G, Yamaji H. (2010). Identification of Armillaria species associated with Polyporus umbellatus using ITS sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA. Mycoscience 51: 366–372. [Google Scholar]

- Koch RA, Wilson AW, Séné O, et al. (2017). Resolved phylogeny and biogeography of the root pathogen Armillaria and its gasteroid relative, Guyanagaster. BMC Evolutionary Biology 17: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf RP. (1972). Synoptic key to the genera of the Pezizales. Mycologia 64: 937–994. [Google Scholar]

- Landvik S, Shailer NFJ, Eriksson OE. (1996). SSU rDNA sequence support for a close relationship between the Elaphomycetales and the Eurotiales and Onygenales. Mycoscience 37: 237–241. [Google Scholar]

- Li LT, Kimbrough JW. (1996). Spore ontogeny in species of Phillipsia and Wynnea (Pezizales). Canadian Journal of Botany 74: 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman J, Sery O, Mikes V. (2004). The rapid identification of European Armillaria species from soil samples by nested PCR. FEMS Microbiology Letters 237: 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T. (2010). Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees, in Proceedings of the Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), 14 Nov. 2010, New Orleans, LA: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Moncalvo JM, Lutzoni FM, Rehner SA, et al. (2000). Phylogenetic relationships of agaric fungi based on nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Systematic Biology 49: 278–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa E. (1984). Sclerotia of Wynnea gigantea. Reports of the Tottori Mycological Institute 22: 80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister DH. (1979). A monograph of the genus Wynnea (Pezizales, Sarcoscyphaceae). Mycologia 71: 144–159. [Google Scholar]

- Posada D. (2008). jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Molecular Biology and Evolution 25: 1253–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A. (2008). FigTree 1.4.2. Institute of Evolutionary Biology, Univ. Edinburgh, Edinburgh: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/ [Google Scholar]

- Ree RH, Smith SA. (2008). Maximum likelihood inference of geographic range evolution by dispersal, local extinction, and cladogenesis. Systematic Biology 57: 4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner SS. (2005). Relaxed molecular clocks for dating historical plant dispersal events. Trends in Plant Science 10: 550–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck P. (2003). MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19: 1572–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze S, Bahnweg G, Moller, et al. (1997). Identification of the genus Armillaria by specific amplification of an rDNA-ITS fragment and evaluation of genetic variation within A. ostoyae by rDNA-RFLP and RAPD analysis. Forest Pathology 27: 225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw CG, Kile GA. (1991). Armillaria root disease. Agricultural Handbook No. 691. USDA Forest Service, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- Smith ME, Henkel TW, Rollins JA. (2015). How many fungi make sclerotia? Fungal Ecology 13: 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, et al. (2013). MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaxter R. (1905). A new American species of Wynnea. Botanical Gazette 39: 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- Tsykun T, Rigling D, Nikolaychuk V, et al. (2012). Diversity and ecology of Armillaria species in virgin forests in the Ukrainian Carpathians. Mycological Progress 11: 403–414. [Google Scholar]

- Volk TJ, Burdsall HH. (1995). A nomenclatural study of Armillaria species. Synopsis Fungorum 8. Fungiflora: Oslo, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Waraitch KS. (1976). New species of Aleuria and Wynnea from India. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 67: 533–536. [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, et al. (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: PCR Protocol: a guide to methods and applications (Innes MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, eds). Academic Press, USA: 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Willetts HJ. (1971). The survival of fungal sclerotia under adverse environmental conditions. Biological Reviews 46: 287–407. [Google Scholar]

- Xing X, Men J, Guo S. (2017). Phylogenetic constraints on Polyporus umbellatus - Armillaria associations. Scientific Reports 7: 4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang WY. (2003). Notes on Wynnea (Pezizales) from Asia. Mycotaxon 87: 131–136. [Google Scholar]