Abstract

Black foot disease is a common and destructive root disease of grapevine caused by a multitude of cylindrocarpon-like fungi in many viticultural areas of the world. This study identified 12 cylindrocarpon-like fungal species across five genera associated with black foot disease of grapevine and other diverse root diseases of fruit and nut crops in the Central Valley Region of California. Morphological observations paired with multi-locus sequence typing of four loci, internal transcribed spacer region of nuclear rDNA ITS1–5.8S–ITS2 (ITS), beta-tubulin (TUB2), translation elongation factor 1-alpha (TEF1), and histone (HIS), revealed 10 previously described species; Campylocarpon fasciculare, Dactylonectria alcacerensis, D. ecuadoriensis, D. macrodidyma, D. novozelandica, D. torresensis, D. valentina, Ilyonectria capensis, I. liriodendri, I. robusta, and two new species, Neonectria californica sp. nov., and Thelonectria aurea sp. nov. Phylogenetic analyses of the ITS+TUB2+TEF1 combined dataset, a commonly employed dataset used to identify filamentous ascomycete fungi, was unable to assign some species, with significant support, in the genus Dactylonectria, while all other species in other genera were confidently identified. The HIS marker was essential either singly or in conjunction with the aforementioned genes for accurate identification of most Dactylonectria species. Results from isolations of diseased plant tissues revealed potential new host associations for almost all fungi recovered in this study. This work is the basis for future studies on the epidemiology and biology of these important and destructive plant pathogens.

Keywords: black foot disease, Nectriaceae, new taxa, systematics

INTRODUCTION

Fungal genera with cylindrocarpon-like asexual morphs are cosmopolitan and may be isolated from soils as saprobes colonizing dead or dying plant material, as latent pathogens or endophytes, or as pathogens causing cankers and root rots of herbaceous and woody plant hosts (Samuels & Brayford 1994, Seifert et al. 2003, Halleen et al. 2004, 2006, Chaverri et al. 2011, Agustí-Brisach & Armengol 2013, Carlucci et al. 2017). The asexual genus Cylindrocarpon (Sordariomycetes, Hypocreales, Nectriaceae) was described in 1913 with Cylindrocarpon cylindroides as the type species and has been linked to the sexual genus Neonectria (Rossman et al. 1999, Mantiri et al. 2001), which is very closely related to Corinectria (González & Chaverri 2017). Booth (1966) first subdivided the genus Cylindrocarpon into four informal morphological groups based on the shape and septation of macroconidia and the presence/absence of microconidia and chlamydospores in culture. Based on Booth’s classification, Rossman et al. (1999) transferred all reference strains of all Nectria groups with cylindrocarpon-like asexual morphs into the genus Neonectria. Three of Booth’s groups correlate strongly with the three clades proposed by Mantiri et al. (2001) based on phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial 18S rDNA sequences.

Asexual morphs in the Neonectria coccinea/galligena-group (clade I in Mantiri et al. 2001) comprise Booth’s Cylindrocarpon group 1 (including the type specimen for the genus Neonectria; Neonectria ramulariae): macroconidia are 3–7(–9)-septate, cylindrical, generally straight, sometimes curved towards rounded ends, cultures generally produce microconidia but lack chlamydospores, with a few exceptions. Asexual morphs in the Neonectria mammoidea/veuillotiana-group (clade II in Mantiri et al. 2001) were placed in Booth’s Cylindrocarpon group 2: macroconidia are (3–)5–7(–9)-septate, fusiform to slightly curved with rounded ends, cultures generally lack microconidia and chlamydospores. Asexual morphs in the Neonectria radicicola-group (clade III in Mantiri et al. 2001) comprised Booth’s Cylindrocarpon group 3 which are characterized by 1–3-septate macroconidia, cylindrical, straight to slightly curved, apical cell bent slightly to one side, and cultures typically produce microconidia and chlamydospores.

Subsequent molecular studies have shown that Neonectria/Cylindrocarpon species clustered into a monophyletic group based on phylogenetic analyses of the mitochondrial 18S ribosomal subunit (Mantiri et al. 2001, Brayford et al. 2004). Both sets of authors indicated that distinct subclades existed within Neonectria, likely representing a generic complex, however neither described any new genera at that time. Halleen et al. (2004) noticed great cultural and morphological variation among cylindrocarpon-like isolates collected from symptomatic and asymptomatic grapevine rootstocks in nurseries and vineyards in Australia, France, New Zealand, and South Africa. Phylogenetic analyses of three loci (ITS, 28S ribosomal large subunit, and TUB2) segregated cylindrocarpon-like asexual morphs from grapevines that produced curved macroconidia that are (1–)3–5(–6)-septate (average four septa), with microconidia and chlamydospores rarely produced in culture, as a unique lineage distant to Neonectria, which they described as Campylocarpon, based on C. fasciculare. Additionally, that study provided the first phylogenetic evidence that cylindrocarpon-like fungi were not monophyletic. This was the first formal taxonomic revision of divergent cylindrocarpon-like asexual morphs from the genus Cylindrocarpon.

A detailed study on the taxonomy and phylogenetic position of cylindrocarpon-like asexual morphs was performed by Chaverri et al. (2011), whereby they described three new genera: (i) Ilyonectria (clade III Mantiri et al. 2001/Booth’s group 3): Ilyonectria species are generally characterized as producing cylindrical to straight to slightly bent macroconidia with 1–3 septa (rarely more than three septa), with rounded ends and a prominent basal hilum, microconidia are ellipsoidal with a prominent basal hilum, and abundant chlamydospores either singly or in chains; (ii) Rugonectria (clade II Mantiri et al. 2001/Booth’s group 2): Rugonectria species are characterized as producing fusarium-like macroconidia that are (3–)5–7(–9)-septate and tapered towards the ends, microconidia are ovoid to cylindrical and no chlamydospores; (iii) Thelonectria (clade II Mantiri et al. 2001/Booth’s group 2): Thelonectria species typically produce fusiform to curved macroconidia that are (3–)5–7(–9)-septate (average five septa), often broadest at upper third, with rounded apical cells and flattened or rounded basal cells, microconidia and chlamydospores are rarely produced in culture. Chaverri et al. (2011) also established Neonectria s. str. (clade I Mantiri et al. 2001/Booth’s group 1), which typically produces cylindrical, generally straight, sometimes with slight curve towards the ends that are 3–7(–9)-septate (average five septa), with rounded ends and an inconspicuous hilum, microconidia are ellipsoidal to oblong, and chlamydospores may be produced by some species. These warranted revisions have helped to stabilize the taxonomy and to highlight the expansive biological and phylogenetic diversity within cylindrocarpon-like fungi.

More recently, phylogenetic studies have revealed Ilyonectria and Thelonectria to be paraphyletic (Cabral et al. 2012a, b, Salgado-Salazar et al. 2016). Lombard et al. (2014) resolved the paraphyletic nature of Ilyonectria by establishing the genus Dactylonectria. Dactylonectria differs morphologically from other cylindrocarpon-like fungi by producing abundant macro- and microconidia with chlamydospores found rarely in culture. Macroconidia of Dactylonectria are cylindrical, straight to slightly curved with 1–4 septa with the apical cell or apex typically bent slightly to one side, microconidia are ellipsoidal to ovoid, aseptate to 1-septate. Salgado-Salazar et al. (2016) established Cinnamomeonectria, Macronectria, and Tumenectria as segregate genera based on phylogenetic and morphological data resolving the paraphyly of Thelonectria. In 2017, Aiello et al. described the monotypic genus, Pleiocarpon, which was the sister taxon to Thelonectria.

To date at least 24 species of cylindrocarpon-like fungi have been associated with black foot disease of grapevine (Lombard et al. 2014, Úrbez-Torres et al. 2014) throughout the main viticultural regions of the world including Europe (Rego et al. 2000, Alániz et al. 2007), the near East (Mohammadi et al. 2009), Oceania (Halleen et al. 2004, Whitelaw-Weckert et al. 2007), South Africa (Halleen et al. 2004), and North and South America (Petit & Gubler 2005, Auger et al. 2007, Petit et al. 2011, Úrbez-Torres et al. 2014). Symptoms of the disease include grapevine roots with necrotic root crowns, reduced root biomass, root rot, sunken root lesions, xylem necrosis, vascular streaking, and general decline of the canopy. Infected vines are often stunted with short internodes and leaves that appear scorched by water stress, eventually the entire vine is killed (Scheck et al. 1998), resulting in costly economic losses due to removal and replanting of new vines. In many instances, black foot disease of grapevine is found in plants suffering stress conditions in the root system including poor planting (J rooting) and poor soil conditions such as poor water drainage (Petit & Gubler 2013).

Beside the rather well-characterized black foot disease of grapevine, only a few additional root diseases of woody crops have been attributed to cylindrocarpon-like fungi and the biology and diversity of these fungi within fruit and nut crops remain overall poorly studied. A few species have been associated with root rot symptoms of avocado (Persea americana) in Italy (Vitale et al. 2012), apple (Malus domestica) in Portugal (Cabral et al. 2012a) and South Africa (Tewoldemedhin et al. 2011), kiwifruit (Actinidia chienensis) in Turkey (Erper et al. 2013), loquat (Eriobotrya japonica) in Spain (Agustí-Brisach et al. 2016), olive (Olea europeae) in California (Úrbez-Torres et al. 2012), and walnut (Juglans regia) in Spain (Mora-Sala et al. 2018). Additionally, species of Ilyonectria have been reported to cause cold storage rot of Prunus spp. in California (Marek et al. 2013) and Canada (Traquair & White 1992), raising concerns among nurseries and growers. Synergistic interactions of cylindrocarpon-like fungi with nematodes and other fungi coupled with predisposing abiotic factors have been associated with Prunus replant disease in California (Bhat et al. 2011).

The aims of the present study were to elucidate the diversity and identity of cylindrocarpon-like species associated with black foot disease of grapevine and root rot symptoms in other perennial crops including almond, cherry, kiwi, olive, peach, pistachio, and walnut in California. Morphological observations coupled with multi-locus sequence typing will allow for accurate species diagnosis and potentially unveil new fungal species and host associations in the most productive agroecosystems within the Central Valley of California.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant sampling and fungal isolation

Between 2014 and 2018, rotted roots from declining grapevines and various fruit and nut trees throughout the Central Valley Region of California were sampled for disease diagnosis. Common symptoms included poor growth and eventually wilting and collapse of entire plants. Roots of declining plants showed necrotic lesions, dark vascular streaking as well as root rot characterized by black discoloration of the root cortex, epidermis, and vascular tissues. Main perennial crops that were surveyed included almond (Prunus dulcis), cherry (Prunus avium), grape (Vitis vinifera), kiwi (Actinidia deliciosa), peach (Prunus persica), pistachio (Pistacia vera), olive (Olea europaea), and walnut (Juglans regia). On average, 2–3 symptomatic plants per vineyard and orchard were sampled. Fungal isolates were recovered from 10–12 necrotic root pieces (4 × 4 × 2 mm) per sample that were surface disinfested in 0.6 % sodium hypochlorite for 30 s, rinsed in two serial baths of sterile deionized water for 30 s, and plated on 2 % potato dextrose agar (PDA, Difco, Detroit, Michigan, USA.) plates amended with tetracycline (1 mg L−1). Petri dishes were incubated at 25 °C in the dark for up to 14 d. Fifty-five isolates with morphological characters of cylindrocarpon-like anamorphs, namely colonies with slow to medium growth with more-or-less consistent margin expansion, yellow to brown in color, were recovered in culture, from symptomatic plants in the Central Valley. All isolates were subsequently hyphal-tip purified to fresh PDA dishes for phylogenetic and morphological analyses. All isolates collected for this study are detailed in Table 1 and are maintained in the culture collection of the Department of Plant Pathology at Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center, Parlier, University of California, Davis, USA.

Table 1.

Fungal isolates used in this study and GenBank accession numbers.

| Species | Isolatea | Host | Geographic origin |

GenBank Accession No.b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | TEF1 | TUB2 | HIS | ||||

| Campylocarpon fasciculare | CBS 112613 | Vitis vinifera | South Africa | AY677301 | JF735691 | AY677221 | – |

| KARE1889 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400278 | MK409922 | MK409845 | – | |

| KARE1890 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400279 | MK409923 | MK409846 | – | |

| KARE1891 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400280 | MK409924 | MK409847 | – | |

| KARE1892 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400281 | MK409925 | MK409848 | – | |

| KARE1893 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400282 | MK409926 | MK409849 | – | |

| KARE1894 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400283 | MK409927 | MK409850 | – | |

| KARE1895 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400284 | MK409928 | MK409851 | – | |

| Campylocarpon pseudofasciculare | CBS 112679 | Vitis vinifera | South Africa | AY677306 | JF735692 | AY677214 | – |

| Dactylonectria alcacerensis | CBS 129087 | Vitis vinifera | Portugal | JF735333 | JF735819 | AM419111 | JF735630 |

| Cy133 | Vitis vinifera | Spain | JF735331 | JF735817 | JF735459 | JF735628 | |

| Cy134 | Vitis vinifera | Spain | JF735332 | JF735818 | JF735629 | JF735629 | |

| KARE413 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400304 | MK409948 | MK409871 | MK409906 | |

| KARE417 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400305 | MK409949 | MK409872 | MK409907 | |

| KARE418 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400306 | MK409950 | MK409873 | MK409908 | |

| Dactylonectria amazonica | MUCL55430 | Rhizoplane, Piper sp. | Ecuador | MF683706 | MF683664 | MF683643 | MF683685 |

| MUCL55433 | Root, Piper sp. | Ecuador | MF683707 | MF683665 | MF683644 | MF683686 | |

| Dactylonectria anthuriicola | CBS 129085 | Anthurium sp. | The Netherlands | JF735302 | JF735768 | JF735430 | – |

| Dactylonectria ecuadoriensis | MUCL55424 | Rhizoplane, Piper sp. | Ecuador | MF683704 | MF683662 | MF683641 | MF683683 |

| MUCL55205 | Root, Piper sp. | Ecuador | MF683700 | MF683658 | MF683637 | MF683679 | |

| MUCL55226 | Root, Cyathea lasiosora | Ecuador | MF683703 | MF683661 | MF683640 | MF683682 | |

| MUCL55432 | Rhizoplane, Socratea exorrhiza | Ecuador | MF683702 | MF683660 | MF683639 | MF683681 | |

| MUCL55431 | Rhizoplane, Carludovica palmata | Ecuador | MF683701 | MF683659 | MF683638 | MF683680 | |

| MUCL55425 | Rhizoplane, Piper sp. | Ecuador | MF683705 | MF683663 | MF683642 | MF683684 | |

| KARE2108 | Olea europaea | San Joaquin Co., CA, USA | MK400316 | MK409960 | MK409883 | MK409918 | |

| KARE2110 | Olea europaea | San Joaquin Co., CA, USA | MK400317 | MK409961 | MK409884 | MK409919 | |

| KARE2113 | Olea europaea | San Joaquin Co., CA, USA | MK400318 | MK409962 | MK409885 | MK409920 | |

| KARE2114 | Olea europaea | San Joaquin Co., CA, USA | MK400319 | MK409963 | MK409886 | MK409921 | |

| Dactylonectria estremocencis | CBS 129085 | Vitis vinifera | Portugal | JF735320 | JF735806 | JF735448 | JF735617 |

| CPC 13539 | Picea glauca | Canada | JF735330 | JF735816 | JF735458 | JF735627 | |

| Dactylonectria hispanica | CBS 142827 | Pinus halepensis | Spain | KY676882 | KY676870 | KY676876 | KY676864 |

| Cy228 | Ficus sp. | Portugal | JF735301 | JF735767 | JF735429 | JF735578 | |

| Dactylonectria macrodidyma | CBS 112615 | Vitis vinifera | South Africa | AY677284 | JF735833 | AY677229 | JF735647 |

| Cy123 | Vitis vinifera | CA, USA | JF735341 | JF735837 | JF735470 | JF735648 | |

| Cy139 | Vitis sp. | Portugal | AM419071 | JF735839 | AM419106 | JF735650 | |

| KARE423 | Prunus dulcis | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400300 | MK409944 | MK409867 | MK409902 | |

| KARE2109 | Olea europaea | San Joaquin Co., CA, USA | MK400301 | MK409945 | MK409868 | MK409903 | |

| KARE2039 | Vitis vinifera | Stanislaus Co., CA, USA | MK400302 | MK409946 | MK409869 | MK409904 | |

| KARE2127 | Pistacia vera | Tulare Co., CA, USA | MK400303 | MK409947 | MK409870 | MK409905 | |

| Dactylonectria novozelandica | CBS 113552 | Vitis vinifera | New Zealand | JF735334 | JF735822 | AY677237 | JF735633 |

| Cy115 | Vitis vinifera | CA, USA | JF735335 | JF735823 | JF735460 | JF735634 | |

| Cy116 | Vitis vinifera | CA, USA | AJ875322 | JF735824 | JF735461 | JF735635 | |

| KARE192 | Prunus avium | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400307 | MK409951 | MK409874 | MK409909 | |

| KARE474 | Prunus avium | Kern Co., CA, USA | MK400308 | MK409952 | MK409875 | MK409910 | |

| KARE2036 | Vitis vinifera | Stanislaus Co., CA, USA | MK400309 | MK409953 | MK409876 | MK409911 | |

| KARE2037 | Vitis vinifera | Stanislaus Co., CA, USA | MK400310 | MK409954 | MK409877 | MK409912 | |

| KARE2038 | Vitis vinifera | Stanislaus Co., CA, USA | MK400311 | MK409955 | MK409878 | MK409913 | |

| KARE2125 | Pistacia vera | Tulare Co., CA, USA | MK400312 | MK409956 | MK409879 | MK409914 | |

| KARE2126 | Pistacia vera | Tulare Co., CA, USA | MK400313 | MK409957 | MK409880 | MK409915 | |

| Dactylonectria polyphaga | MUCL55209 | Root, Costus sp. | Ecuador | MF683689 | MF683647 | MF683626 | MF683668 |

| MUCL54802 | Root, Asplenium sp. | Ecuador | MF683698 | MF683656 | MF683635 | MF683677 | |

| Dactylonectria torresensis | CBS 129086 | Vitis vinifera | Portugal | JF735362 | JF735870 | JF735492 | JF735681 |

| Cy118 | Vitis vinifera | CA, USA | JF735354 | JF735859 | JF735483 | JF735670 | |

| Cy120 | Vitis vinifera | CA, USA | AJ875320 | JF735860 | AJ875320 | JF735671 | |

| KARE1173 | Pistacia vera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400298 | MK409942 | MK409865 | MK409900 | |

| KARE1174 | Pistacia vera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400299 | MK409943 | MK409866 | MK409901 | |

| Dactylonectria valentina | CBS 142826 | Ilex aquifolium | Spain | KY676881 | KY676869 | KY676875 | KY676863 |

| KARE2111 | Olea europaea | San Joaquin Co., CA, USA | MK400314 | MK409958 | MK409881 | MK409916 | |

| KARE2112 | Olea europaea | San Joaquin Co., CA, USA | MK400315 | MK409959 | MK409882 | MK409917 | |

| Dactylonectria vitis | CBS 129082 | Vitis vinifera | Portugal | JF735303 | JF735769 | JF735431 | JF735580 |

| Ilyonectria capensis | CBS 132815 | Protea sp. | South Africa | JX231151 | JX231119 | JX231103 | — |

| KARE1920 | Prunus persica | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400330 | MK409974 | MK409897 | — | |

| KARE1921 | Prunus persica | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400331 | MK409975 | MK409898 | — | |

| Ilyonectria crassa | CBS 139.30 | Lilium sp. | The Netherlands | JF735275 | JF735723 | JF735393 | — |

| Ilyonectria destuctans | CBS 264.65 | Cyclamen persicum | Sweden | AY677273 | JF735695 | AY677256 | — |

| Ilyonectria europaea | CBS 129078 | Vitis vinifera | Portugal | JF735294 | JF735756 | JF735421 | — |

| Ilyonectria liriodendri | CBS 110.81 | Liriodendron tulipifera | Yolo Co., CA, USA | DQ178163 | JF735696 | DQ178170 | — |

| KARE84 | Prunus avium | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400322 | MK409966 | MK409889 | — | |

| KARE85 | Prunus avium | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400323 | MK409967 | MK409890 | — | |

| KARE88 | Prunus avium | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400324 | MK409968 | MK409891 | — | |

| KARE97 | Prunus avium | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400325 | MK409969 | MK409892 | — | |

| KARE1206 | Actinidia deliciosa | Tulare Co., CA, USA | MK400326 | MK409970 | MK409893 | — | |

| KARE1207 | Actinidia deliciosa | Tulare Co., CA, USA | MK400327 | MK409971 | MK409894 | — | |

| KARE2046 | Juglans regia | Tulare Co., CA, USA | MK400328 | MK409972 | MK409895 | — | |

| KARE2049 | Juglans regia | Tulare Co., CA, USA | MK400329 | MK409973 | MK409896 | — | |

| Ilyonectria mors-panacis | CBS 306.35 | Panax quinquefolium | Canada | JF735288 | JF735746 | JF735414 | — |

| Ilyonectria palmarum | CBS 135754 | Howea fosteriana | Italy | HF937431 | HF922614 | HF922608 | — |

| Ilyonectria robusta | CBS 308.35 | Panax quinquefolium | Canada | JF735264 | JF735707 | JF735377 | — |

| KARE1740 | Olea europaea | Glenn Co., CA, USA | MK400320 | MK409964 | MK409887 | — | |

| KARE1741 | Olea europaea | Glenn Co., CA, USA | MK400321 | MK409965 | MK409888 | — | |

| Ilyonectria venezuelensis | CBS 102032 | Unknown | Venezuela | AM419059 | JF735760 | AY677255 | — |

| Nectria balansae | CBS 125119 | Living woody vine | French Guiana | HM484857 | HM484848 | HM484874 | — |

| Nectria cinnabarina | A.R. 4477 | Aesculus sp. | France | HM484548 | HM484527 | HM484606 | — |

| Neonectria californica | KARE1838/CBS 145774 | Pistacia vera | Madera Co., CA, USA | MK400332 | MK409976 | MK409899 | — |

| Neonectria ditissima | CBS 226.31 | Fagus sylvatica | Fresno Co., CA, USA | JF735309 | JF735783 | DQ789869 | — |

| Neonectria lugdunensis | CBS 125485 | Populus fremontii | USA | KM231762 | KM231887 | KM232019 | — |

| Neonectria major | CBS 240.29 | Alnus incana | Norway | JF735308 | JF735782 | DQ789872 | — |

| Neonectria neomacrospora | CBS 324.61 | Abies concolor | Netherlands | JF735312 | HM364352 | DQ789875 | — |

| Neonectria obtusispora | CBS 183.36 | Solanum tuberosum | Germany | AM419061 | JF735796 | AM419085 | — |

| Neonectria ramulariae | CBS 151.29 | Malus sylvestris | England | JF735313 | JF735791 | JF735438 | — |

| Thelonectria acrotyla | G.J.S. 90-171 | Unknown | Venezuela | JQ403329 | JQ394751 | JQ394720 | — |

| Thelonectria amamiensis | MAFF 239819 | Pinus luchuensis | Japan | JQ403337 | KJ022348 | JQ394727 | — |

| MAFF 239820 | Pinus luchuensis | Japan | JQ403338 | KJ022349 | JQ394720 | — | |

| Thelonectria aurea | KARE1830/CBS 145584 | Olea europaea | Glenn Co., CA, USA | MK400285 | MK409929 | MK409852 | — |

| KARE98 | Prunus avium | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400286 | MK409930 | MK409853 | — | |

| KARE1831 | Olea europaea | Glenn Co., CA, USA | MK400287 | MK409931 | MK409854 | — | |

| KARE1832 | Olea europaea | Glenn Co., CA, USA | MK400288 | MK409932 | MK409855 | — | |

| KARE1833 | Olea europaea | Glenn Co., CA, USA | MK400289 | MK409933 | MK409856 | — | |

| KARE1834 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400290 | MK409934 | MK409857 | — | |

| KARE1835 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400291 | MK409935 | MK409858 | — | |

| KARE1836 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400292 | MK409936 | MK409859 | — | |

| KARE1837 | Vitis vinifera | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400293 | MK409937 | MK409860 | — | |

| KARE1839 | Pistacia vera | Madera Co., CA, USA | MK400294 | MK409938 | MK409861 | — | |

| KARE1840 | Pistacia vera | Madera Co., CA, USA | MK400295 | MK409939 | MK409862 | — | |

| KARE1841 | Pistacia vera | Madera Co., CA, USA | MK400296 | MK409940 | MK409863 | — | |

| KARE1923 | Prunus persica | Fresno Co., CA, USA | MK400297 | MK409941 | MK409864 | — | |

| Thelonectria blackeriella | BF142 | Vitis vinifera | Italy | KX778711 | — | KX778702 | — |

| Thelonectria diademata | A.R. 4765 | Unknown | Argentina | NR_137784 | JQ394736 | JQ394700 | — |

| Thelonectria gongylodes | G.J.S. 04-171 | Acer sp. | Tennessee, USA | JQ403318 | JQ394744 | JQ394710 | — |

| Thelonectria nodosa | G.J.S. 04-155 | Thuja canadiensis | Tennessee, USA | JQ403317 | JQ394743 | JQ394709 | — |

| Thelonectria olida | CBS 215.67 | Asparagus officinalis | Germany | KJ021982 | — | KM232024 | — |

| Thelonectria stemmata | C.T.R. 71-19 | Unknown | Jamaica | JQ403312 | JQ394739 | JQ394704 | — |

| Thelonectria torulosa | A.R. 4764 | Unknown | Argentina | JQ403309 | KJ022389 | JQ394701 | — |

| Thelonectria trachosa | CBS 112467 | Bark of conifer | Scotland | KF529842 | KF569860 | KF569869 | — |

| Thelonectria truncata | G.J.S. 04-357 | Unknown | Tennessee, USA | JQ403319 | JQ394745 | KJ022324 | — |

| MAFF241521 | Unknown | Japan | JQ403339 | KJ022325 | JQ394757 | — | |

| Thelonectria veuillotiana | G.J.S. 92-24 | Fagus sylvatica | France | JQ403335 | JQ394755 | JQ394725 | — |

| CBS 132341 | Eucalyptus sp. | Azores Island | JQ403305 | JQ394734 | JQ394698 | — | |

aIsolates in bold represent ex-type specimens.

bGenBank accessions in bold were produced in this study.

Phylogenetic analyses

Total genomic DNA was isolated from mycelium scraped with a sterile scalpel from the surface of 14-d-old PDA cultures using the DNeasy Plant Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California), following the manufacturer’s instructions. All PCR reactions utilized AccuPower™ PCR Premix (Bioneer, Alameda, California), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Amplification of ribosomal DNA (rDNA), including the intervening internal transcribed spacer regions and 5.8S rDNA (ITS1–5.8S–ITS2), using the primer set ITS1 and ITS4 followed the protocol of White et al. (1990). Amplification of translation elongation factor 1-α (TEF1) fragments utilized the primer set CYLEF-1 and CYLEF-R2 (Crous et al. 2004, Cabral et al. 2012a), histone gene (HIS) fragments utilized CYLH3F and CYLH3R (Crous et al. 2004) (only for Dactylonectria isolates), and beta-tubulin (TUB2) utilized primers T1 and CYLTUB1R (O’Donnell & Ciglek 1997, Crous et al. 2004), with a slightly modified PCR program for TEF1 and TUB2: [initial denaturation (94 °C, 5 min) followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (94 °C, 30 s), annealing (58 °C for TEF1 and 62 °C for TUB2, 30 s), extension (72 °C, 60 s), and a final extension (72 °C, 10 min)]. PCR products were visualized on a 1.5 % agarose gel (120 V for 25 min) stained with GelRed® (Biotium, Fremont, California), following the manufacturer’s instructions, to confirm presence and size of amplicons, purified via Exonuclease I and recombinant Shrimp Alkaline Phosphatase (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, California), and sequenced bidirectionally on an ABI 3730 Capillary Electrophoresis Genetic Analyzer (College of Biological Sciences Sequencing Facility, University of California, Davis).

Forward and reverse nucleotide sequences were assembled, proofread, and edited in Sequencher v. 5 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, Michigan) and deposited in GenBank (Table 1). Homologous sequences with high similarity from type isolates and non-type isolates (n = 31 and n = 32, respectively; Table 1) were included for phylogenetic reference utilizing the BLASTn function in NCBI including the curated database TrunkDiseaseID.org (Lawrence et al. 2017). Multiple sequence alignments were performed in MEGA v. 6 (Tamura et al. 2013) and manually adjusted where necessary in Mesquite v. 3.10 (Maddison & Maddison 2016). Alignments were submitted to TreeBASE under accession number S22859. Phylogenetic analyses were performed for each individual locus, for four different three-gene combinations (ITS+TEF1+TUB2; ITS+TEF1+HIS; ITS+TUB2+HIS; and TEF1+TUB2+HIS) and a four-gene (ITS+TEF1+TUB2+HIS) concatenated dataset. Each dataset was analyzed using two different optimality search criteria, maximum parsimony (MP) and maximum likelihood (ML) in PAUP v. 4.0b162 and GARLI v. 0.951 (Swofford 2003, Zwickl et al. 2006), respectively. For MP analyses, heuristic searches with 1 000 random sequence additions were implemented with the Tree-Bisection-Reconnection algorithm, gaps were treated as missing data. Bootstrap analyses with 1 000 replicates using a heuristic search with simple sequence addition were used to produce majority-rule consensus trees to estimate branch support. For ML analyses, MEGA was used to infer a model of nucleotide substitution for each dataset, using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). ML analyses were conducted according to the best fit model of nucleotide substitution using default parameters in GARLI. Branch stability was determined by 1 000 bootstrap replicates. Sequences of Nectria cinnabarina isolate A.R. 4477 and N. balansae isolate CBS 125119 served as the outgroup taxa in all analyses except for the analyses of HIS where Dactylonectria estremocensis isolates CBS 129085 and CPC 13539 served as the outgroup taxon.

Morphology

Mycelial plugs (5-mm-diam) were taken from the margin of selected, actively growing cultures based on phylogenetic results and transferred to triplicate 90-mm-diam Petri dishes containing 2 % PDA and incubated at room temperature (24 +/− 1 °C) under natural photoperiod in April 2018 for up to 21 d. Radial growth was measured on day 7 and 14 by taking two measurements perpendicular to each other. Assessments of colony color (Rayner 1970) and morphology were made on day 14. Conidiophores (n = 20), macro- and microconidial dimensions (n = 30), phialides (n = 20), and chlamydospores (n = 20) were measured at 400 × and 1 000 × magnification from approximately 10-d-old synthetic low-nutrient agar (SNA; Nirenberg 1976) cultures, incubated as above, by excising a 1 cm3 SNA cube and placing on a glass microscope slide followed by placing a glass coverslip (no stain was applied, thus the native pigments of each fungal species was preserved) and observed with a Leica DM500B microscope (Leica microsystems CMS GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). Morphological measurements are represented by the mean in the center with minima and maxima rounded to the nearest half micron in parentheses, respectively. The optimal temperature for growth was determined using strains KARE1838 and KARE1830. A 5-mm mycelial plug taken from the margin of an actively growing colony was placed in the center of triplicate 90-mm-diam PDA Petri dishes. Cultures were incubated at temperatures of 10–30 °C in 5 °C increments in the dark and radial growth was measured as above.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic analyses

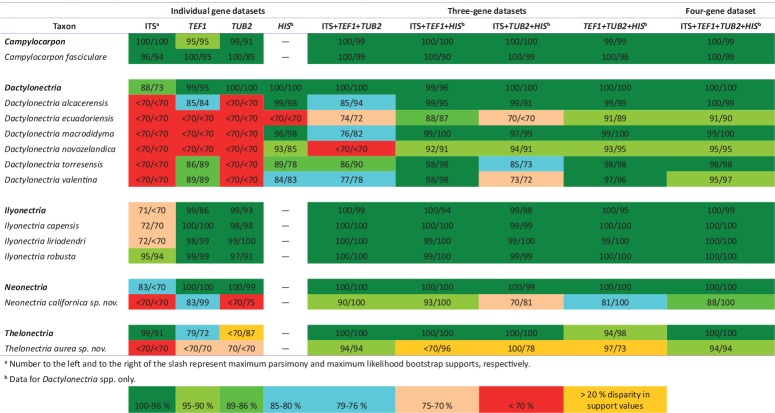

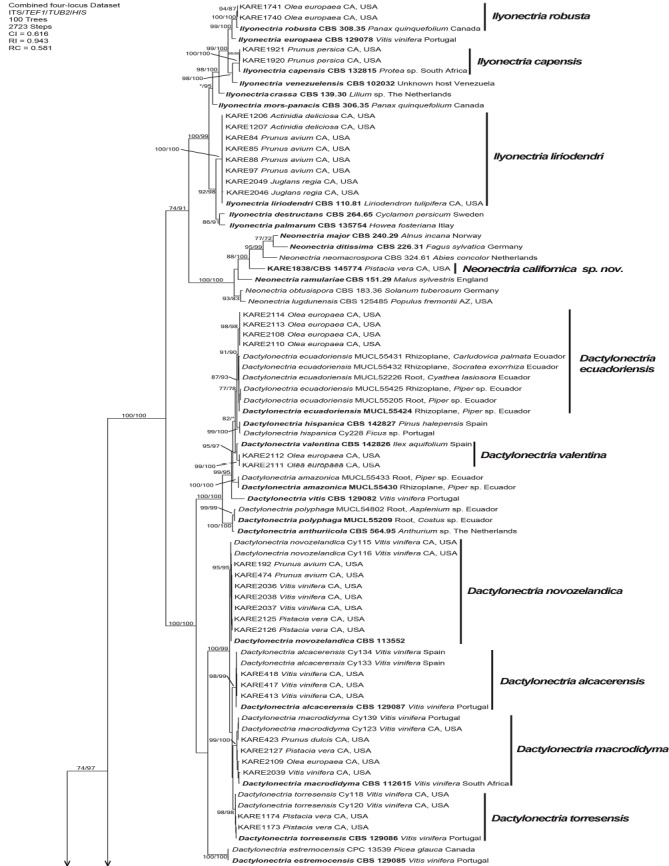

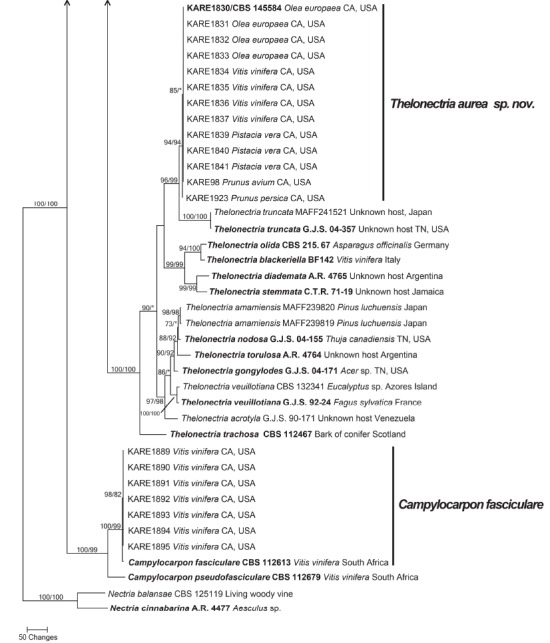

For delimiting the taxonomy of cylindrocarpon-like fungi, 118 strains were included in the alignment. The alignment parameters and unique site patterns of the different gene regions, gene combinations, and phylogenetic methods analyzed are presented in Table 2. The clade support values for genus/species identifications based on the different gene regions, gene combinations, and phylogenetic methods are plotted in a heat map in Table 3. The ITS, TEF1, and TUB2 individual phylogenies displayed low to moderate resolution of species boundaries within the genera Dactylonectria, Neonectria, and Thelonectria (Table 3), while TEF1 and TUB2 confidently identified Campylocarpon fasciculare and Ilyonectria capensis, I. liriodendri, and I. robusta. The HIS phylogeny strongly to moderately (≥ 84 % / ≥ 78 %, MP and ML bootstrap supports, respectively) supported all species in Dactylonectria, with the exception of D. ecuadoriensis (<70 % / < 70 %) (Table 3). The analysis of the four different three-gene dataset combinations yielded varying levels of support for Dactylonectria species. The ITS+TEF1+HIS and TEF1+TUB2+HIS datasets produced the strongest levels of support (≥ 88 % / ≥ 87 %) for six Dactylonectria species including four members of the former ‘macrodidyma’ species-complex (D. alcacerensis, D. macrodidyma, D. novozelandica, and D. torresensis) and two species that are closely related to D. vitis (D. ecuadoriensis and D. valentina). Furthermore, the clade supports from the four-gene analyses (ITS+TEF1+TUB2+HIS; Fig. 1) did not differ as compared to the aforementioned two three-gene analyses (ITS+TEF1+HIS and TEF1+TUB2+HIS; Table 3). The analysis of the datasets ITS+TEF1+TUB2 and ITS+TUB2+HIS provided variable support for four Dactylonectria species in the ‘macrodidyma’ species-complex and for the closely related species D. ecuadoriensis and D. valentina (Table 3). The commonly employed ITS+TEF1+TUB2 dataset was able to confidently identify (100 % / 100 %) three Ilyonectria species (I. capensis (two isolates), I. liriodendri (eight isolates), and I. robusta (two isolates), a monotypic lineage that clusters in Neonectria, with no apparent type or non-type association, close to N. neomacrospora CBS 324.61, the ex-type specimens of N. major CBS 240.29 and N. ditissima CBS 226.31. This lineage thus represented a potentially novel phylogenetic species, hereinafter identified as Neonectria californica sp. nov. (Table 3; Fig. 1), and 13 isolates clustered in the recently proposed genus Thelonectria with no apparent type or non-type association. Therefore these 13 isolates are hereinafter identified as Thelonectria aurea sp. nov. (Table 3; Fig. 1), which is closely related to T. truncata. The use of only two genes in any combination failed to properly support T. aurea (Table 3), however the three-gene combination as mentioned above robustly separates the two lineages (Fig. 1). The commonly employed dataset ITS+TEF1+TUB2 was unable to robustly identify several species in Dactylonectria, providing only low to moderate support for, D. ecuadoriensis (74 % / 72 %), D. macrodidyma (76 % / 82 %), D. valentina (77 %/78 %), and no support for D. novozelandica (< 70 % / < 70 %), (Table 3).

Table 2.

Statistical information on phylogenetic datasets analyzed in this study.

| Individual gene datasets | Three-gene datasets | Four-gene dataset | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| ITS | TEF1 | TUB2 | HISa | ITS+TEF1+TUB2 | ITS+TEF1+HISa | ITS+TUB2+HISa | TEF1+TUB2+HISa | ITS+TEF1+TUB2+HISa | |

| Aligned characters (gaps included) | 629 | 795 | 750 | 541 | 2174 | 1965 | 1920 | 2086 | 2715 |

| Equally most parsimonious trees retained | 100 | 100 | 100 | 6 | 100 | 36 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Tree length | 507 | 946 | 988 | 175 | 2543 | 1682 | 1704 | 2185 | 2723 |

| Consistency index (CI) | 0.659 | 0.636 | 0.613 | 0.771 | 0.606 | 0.637 | 0.631 | 0.615 | 0.616 |

| Retention index (RI) | 0.955 | 0.950 | 0.941 | 0.963 | 0.942 | 0.948 | 0.945 | 0.941 | 0.943 |

| Rescaled Consistency index (RC) | 0.629 | 0.604 | 0.577 | 0.743 | 0.571 | 0.604 | 0.596 | 0.579 | 0.581 |

| Constant characters | 414 | 408 | 368 | 425 | 1190 | 1247 | 1207 | 1201 | 1615 |

| Parimony-uninformative characters | 30 | 77 | 59 | 15 | 166 | 122 | 104 | 151 | 181 |

| Parsimony-informative characters | 185 | 310 | 323 | 101 | 818 | 596 | 609 | 734 | 919 |

| Nucleotide substitution model | TN93+G | HKY+G | GTR+G+I | TN93+G | Assigned accordingly | Assigned accordingly | Assigned accordingly | Assigned accordingly | Assigned accordingly |

| Log likelihood of most likely tree | -3291.744 | -5448.788 | -5518.968 | -1539.751 | -15443.408 | -10781.305 | -11019.718 | -13306.448 | -17539.415 |

a Only includes Dactylonectria spp.

Table 3.

Clade support values plotted as a heat map for individual and combined datasets for species recovered in this study.

Fig. 1.

One of 100 equally most parsimonious trees generated from maximum parsimony analysis of the four-gene (ITS+TEF1+TUB2+HIS) combined dataset. Numbers in front and after the slash represent parsimony and likelihood bootstrap values from 1 000 replicates, respectively. Values represented by an asterisk were less than 70 % for the bootstrap analyses. The scale bar indicates the number of nucleotide changes.

Morphology

Morphological characteristics of the fungal isolates recovered were similar to the descriptions of species in the genera Campylocarpon, Dactylonectria, Ilyonectria, Neonectria, and Thelonectria (Halleen et al. 2004, Chaverri et al. 2011, Lombard et al. 2014). Morphological characteristics of novel taxa are reported in the taxonomy section below.

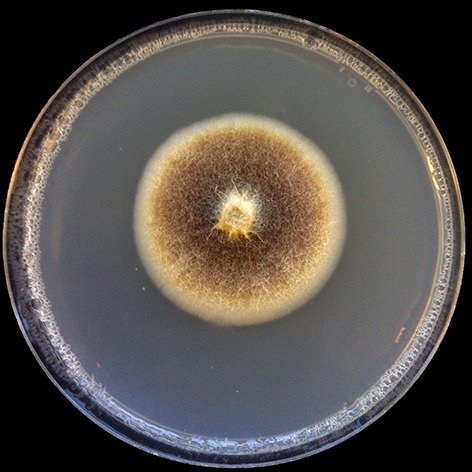

Despite several media tested (PDA and SNA), no isolates molecularly identified as Campylocarpon fasciculare produced spores. Campylocarpon fasciculare isolate KARE1890 colonies after 14 d average 43.8 mm on PDA. Center of colony on PDA is livid red to dark vinaceous, with copious aerial hyphae, the inner margin is pale luteous and the outer margin is smooth, submerged, and white to off-white. Fascicles of hyphae extend from the colony center (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Culture morphology of Campylocarpon fasciculare (KARE1890) recovered in this study.

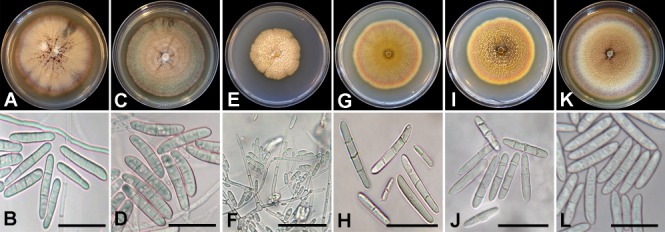

Dactylonectria alcacerensis isolate KARE417 colonies after 14 d average 73.5 mm on PDA, fast-growing with mostly even margin expansion (Fig. 3A). Center of colony on PDA is buff with felty appearance with radial furrows and small sporulation centers and a flat, submerged, and violet colored inner margin and coral colored outer margin. Conidiophores (60.5–)88(–124.5) μm, simple or complex, long, slender, arising from aerial hyphae, also as sporodochial pulvinate domes of slimy masses on SNA. Phialides (27.5–)51(–88.5) μm long, wider at the base (1.5–)2.5(–3.5) μm and tapering toward the apex (1.5–)1.5(–2) μm. Macroconidia cylindrical, straight to slightly bent toward the apical cell, 1–3-septate (Fig. 3B); 1-septate conidia (9.5–)14.5(–29.1) × (2.5–)3.5(–5.5) μm; 2-septate conidia (23–)29(–34) × (3.5–)5(–6.5) μm; 3-septate conidia (28.5–)36.5(–44) × (4–)5.5(–8) μm. Microconidia elliptical (5.5–)8.5(–15.5) × (2.5–)3(–4) μm. Chlamydospores not observed on SNA.

Fig. 3.

Culture morphology and conidia of Dactylonectria species recovered in this study. A–B. Dactylonectria alcacerensis (KARE417). C–D. Dactylonectria ecuadoriensis (KARE2113). E–F. Dactylonectria macrodidyma (KARE423). G–H. Dactylonectria novozelandica (KARE474). I–J. Dactylonectria torresensis (KARE1173). K–L. Dactylonectria valentina (KARE2111). Scale bars = 20 μm.

Dactylonectria ecuadoriensis isolate KARE2113 colonies after 14 d average 72.2 mm on PDA, fast-growing with even margin expansion (Fig. 3C). Center of colony on PDA is buff with copious glaucous blue green felty aerial hyphae and a smooth, submerged, pale violet mostly entire, margin. Conidiophores (27.5–)22(–82.5) μm, simple or complex, long, slender, arising from aerial hyphae, also as sporodochial pulvinate domes of slimy masses on SNA. Phialides (11.5–)25.5(–41.5) μm long, wider at the base (2–)2.5(–3.5) μm and tapering toward the apex (1.5–)2(–2.5) μm. Macroconidia cylindrical to slightly bent 1(–3)-septate (Fig. 3D); 1-septate (22.5–)25(–28.5) × (4–)5(–6.5) μm; 2-septate (24.5–)28.5(–32.5) × (4.5–)5(–5.5) μm, and 3-septate (31.5–)36(–41) × (5.5–)6.5(–7). Microconidia elliptical, not common, (5.5–)7.5(–8.5) × (2.5–)3(–4) μm. Chlamydospores not observed on SNA.

Dactylonectria macrodidyma isolate KARE423 colonies after 14 d average 46.5 mm on PDA, medium-growing with slight uneven margin expansion (Fig. 3E). Center of colony on PDA is buff with copious felty aerial hyphae and a flat honey margin, submerged, with fairly even growth. Conidiophores (51–)82(–121) μm, simple or complex, long, slender, arising from aerial hyphae, also as sporodochial pulvinate domes of slimy masses on SNA. Phialides (26–)50.5(–85) μm long, wider at the base (1.5–)2(–2.5) μm and tapering toward the apex (1–)1.5(–2) μm. Macroconidia cylindrical 1(–3)-septate (Fig. 3F); 1-septate (8.5–) 12(–15.5) × (2–)3(–3) μm; 2–3-septate conidia uncommon. Microconidia elliptical, copious, (4–)5.5(–8) × (1.5–)2(–2.5) μm. Chlamydospores not observed on SNA.

Dactylonectria novozelandica isolate KARE474 colonies after 14 d average 62.2 mm on PDA, medium-growing with even margin expansion (Fig. 3G). Center of colony on PDA is ochreous to coral with felty aerial hyphae and amber to apricot margin, flat and submerged. Conidiophores (42–)89(–148.5) μm, arise from long, slender, aerial hyphae, also as sporodochial pulvinate domes of slimy masses on SNA. Phialides (18.5–)32(–49.5) μm, wider at the base (2–)2.5(–3) μm and tapering toward the apex (1.5–)2(–3) μm. Macroconidia cylindrical, 1–3-septate (Fig. 3H); 1-septate conidia (8–)12(–17.5) × (2–)2.5(–3.5) μm; 2-septate conidia (23–)27(–34) × (3–)4(–4.5) μm; 3-septate conidia (28.5–) 34(–46.5) × (3.5–)4.5(–6) μm. Microconidia elliptical, (7–)9.5(–11.5) × (2–)3(–4) μm. Chlamydospores not observed on SNA.

Dactylonectria torresensis isolate KARE1173 colonies after 14 d average 59.7 mm on PDA, medium-growing with even margin expansion (Fig. 3I). Center of colony on PDA is ochreous to umber with copious coral to apricot aerial hyphae and luteous margin, flat and submerged. Conidiophores (58.5–) 94(–127) μm, simple or complex, long, slender, arising from aerial hyphae, also as sporodochial pulvinate domes of slimy masses on SNA. Phialides (29.5–)59(–126) μm, wider at the base (2–)2.5(–3.5) μm and tapering toward the apex (1.5–)2(–2.5) μm. Macroconidia cylindrical, (1–)3-septate (Fig. 3J); 1-septate conidia (13–)26.5(–37) × (3.5–)5(–7) μm; 2-septate conidia (21–)31.5(–35.5) × (3–)5(–6) μm; and 3-septate conidia (32.5–) 35.5(–38) × (3.5–)5(–6.5) μm. Microconidia elliptical, aseptate, (7–)10(–15) × (2–)2.5(–3.5) μm. Chlamydospores not observed on SNA.

Dactylonectria valentina isolate KARE2111 colonies after 14 d average 79.5 mm on PDA, fast-growing with even margin expansion (Fig. 3K). Center of colony on PDA is buff to honey with copious purple felty aerial hyphae with a flat and submerged flesh-colored margin. Conidiophores (34–)50.5(–79.5) μm, simple or complex, long, slender, arising from aerial hyphae, also as sporodochial pulvinate domes of slimy masses on SNA. Phialides (16.5–)27(–42) μm, wider at the base (1.5–) 2.5(–3.5) μm and tapering toward the apex (1.5–)2(–2) μm. Macroconidia cylindrical, (1–)3-septate (Fig. 3L); 1-septate conidia (19.5–)23.5(–28) × (3.5–)4.5(–5) μm; 2-septate conidia (24.5–)27.5(–31) × (4.5–)5(–5.5) μm; and 3-septate conidia (25.5–)40(–39) × (4–)5(–6.5) μm. Microconidia elliptical, aseptate, (5.5–)9.5(–14.5) × (2–)2.5(–3.5) μm. Chlamydospores not observed on SNA.

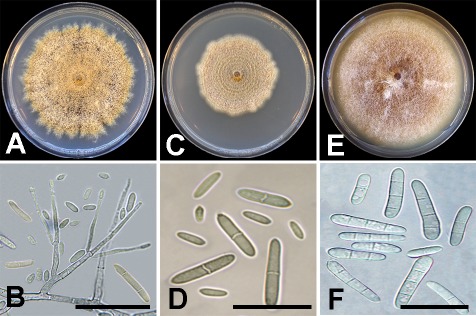

Ilyonectria capensis isolate KARE1920 colonies after 14 d average 75.8 mm on PDA, fast-growing with uneven margin (Fig. 4A). Center of colony on PDA is honey to buff with abundant aerial hyphae and a hazel margin, slightly raised and uneven. Conidiophores (36–)70.5(–109.5) μm, simple or complex, long, slender, arising from aerial hyphae, also as sporodochial pulvinate domes of slimy masses on SNA. Phialides (16–)24.5(–43.5) μm, wider at the base (1.5–)2(–2.5) μm and tapering toward the apex (1.5–)1.5(–2) μm. Macroconidia cylindrical, straight to slightly bent toward the apical cell, 0–1(–3)-septate (Fig. 4B); 0–1-septate conidia (9.5–)12(–14) × (1.5–)2(–2.5) μm; 2–3-septate conidia rarely observed. Microconidia predominating, aseptate, ovoid to ellipsoid, (4.5–)6(–9.5) × (2–) 2.5(–4) μm. Chlamydospores not observed on SNA.

Fig. 4.

Culture morphology and conidia of Ilyonectria species recovered in this study. A–B. Ilyonectria capensis (KARE1920). C–D. Ilyonectria liriodendri (KARE1207). E–F. Ilyonectria robusta (KARE1741). Scale bars: B = 30 μm; D and F = 20 μm.

Ilyonectria liriodendri isolate KARE1207 colonies after 14 d average 50.3 mm on PDA, medium-growing with some unevenness (Fig. 4C). Center of colony on PDA is buff with felty aerial hyphae and buff margin, flat and submerged. Conidiophores (29–)63(–88) μm, long, slender, mainly from aerial hyphae, and as sporodochial pulvinate domes of slimy masses on SNA. Phialides (13.5–)21.5(–32.5) μm, wider at the base (1.5–)2(–3) μm and tapering at the apex (1–)1.5(–2) μm. Macroconidia cylindrical, straight to slightly bent toward the apical cell, 1–3-septate (Fig. 4D); 1-septate conidia (11.5–)17 (–24.5) × (2–)3(–3.5) μm; 2-septate conidia (11.5–)15.5(–20.5) × (2.5–)3(–4.5) μm; 3-septate conidia (13–)18.5(–24) × (2.5–)3.5(–4.5) μm. Microconidia abundant, aseptate, elliptical, (4.5–)6(–8) × (1.5–)2(–3) μm. Chlamydospores globose to subglobose, (7.5–)13.5(–19) × (6.5–)12(–15.5) μm, mostly smooth some appear rough with deposits, thick-walled, formed singly or more commonly in short chains of up to four to five, becoming brown with age.

Ilyonectria robusta isolate KARE1741 colonies after 14 d average 82 mm on PDA, medium-growing with even margin expansion (Fig. 4E). Center of colony on PDA is rust-colored with abundant felty aerial hyphae with a buff margin, flat and submerged. Conidiophores (54–)77.5(–112.5) μm, long, slender, mainly from aerial hyphae, also as sporodochial pulvinate domes of slimy masses on SNA. Phialides (13.5–)21.5(–32.5) μm, wider at the base (1.5–)2(–3) μm and tapering at the apex (1–)1.5(–2) μm. Macroconidia cylindrical, straight to slightly bent to one side near the apical cell, (1–)3-septate (Fig. 4F); 1-septate conidia (11.5–)17(–24.5) × (2–)3(–3.5) μm; 2-septate conidia (11.5–) 15.5(–20.5) × (2.5–)3(–4.5) μm; 3-septate conidia (13–)18.5(–24) × (2.5–)3.5(–4.5) μm. Microconidia abundant, aseptate, elliptical, (4.5–)6(–8) × (1.5–)2(–3) μm. Chlamydospores globose to subglobose, (6.5–)10.5(–14) × (6–)9(–12.5) μm, mostly smooth some appear rough with deposits, thick-walled, mostly occurring in concatenated chains of up to four to five, becoming golden-brown with age. No sexual morphs were observed on PDA nor SNA after 60 d.

Taxonomy

Morphological comparisons coupled with multi-locus phylogenetic analyses (MP and ML) of the combined multi-locus dataset identified two distinct and well-supported lineages for which no apparent species names exist. Thus, we propose the following new species binomials to properly circumscribe these unique species that were isolated from diseased roots of perennial fruit and nut crops in this study.

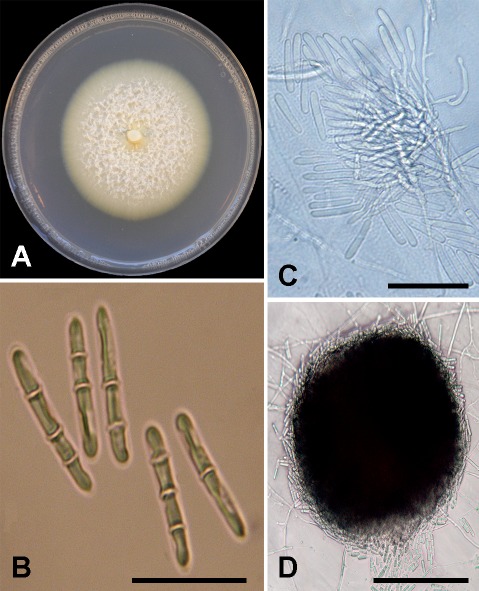

Neonectria californica D.P. Lawr. & Trouillas, sp. nov. MycoBank MB829442. Figs 1, 5.

Fig. 5.

Neonectria californica sp. nov. (holotype BPI 910947, ex-type culture CBS 145774). A. Fourteen-day-old PDA culture. B. Macroconidia. C. Conidiophores. D. Sporodochial pulvinate dome of slimy masses of macroconidia. Scale bars: B–C = 30 μm; D = 65 μm.

Etymology: californica, named after the State of California, where the ex-type strain was collected.

Sexual morph: Undetermined. Asexual morph: Conidiophores simple or complex. Simple conidiophores short and sparsely branched, (30–)62.5(–86.5) μm long terminating in a whorl of phialides. Phialides monophialidic, cylindrical, tapering toward the apex, (12–)19(–29) μm long, (1.5–)2.5(–2.5) μm wide at the base, and (1.5–)1.5(–1.5) μm wide at the apex. Macroconidia on SNA produced predominately in sporodochial pulvinate domes of slimy masses, (1–)3-septate, generally cylindrical, smooth-walled, some slightly curved, slightly wider at the base, with rounded end cells; 1-septate conidia (17.5–)20(–22.5) × (2.5–) 3.5(–4.5) μm; 2-septate conidia (18–)21.5(–23.5) × (2.5–)3.5(–4) μm; 3-septate conidia (21–)23.5(–27.5) × (3–)3.5(–4.5) μm. Microconidia and chlamydospores not observed on SNA.

Culture characteristics: Colonies after 14 d average 55.3 mm on PDA, medium-growing with even margin expansion. Center of colony on PDA is white with abundant floccose aerial hyphae producing a cottony texture with a flat and submerged off-white margin with sparse aerial hyphae emerging directly behind the advancing front. Optimal growth temperature was 20 °C.

Host: Pistacia vera.

Distribution: Madera County, California, USA.

Specimen examined: USA, California, Madera County, isolated from symptomatic roots (necrotic lesions and black discoloration of the root cortex, epidermis, and vascular tissues) of Pistacia vera, 13 Jun. 2017, F.P. Trouillas (holotype BPI 910947, culture ex-type CBS 145774).

Notes: Phylogenetic analyses of the ITS+TEF1+TUB2 combined three-gene dataset suggests that N. neomacrospora, N. ditissima, and N. major are the closest relatives of N. californica. Neonectria ditissima, N. major, and N. neomacrospora produce microconidia (Castlebury et al. 2006, Schmitz et al. 2017), whereas N. californica does not. Macroconidia of N. ditissima, N. major, and N. neomacrospora range from 3–8 -septate, whereas only 3-septate macroconidia were observed for N. californica.

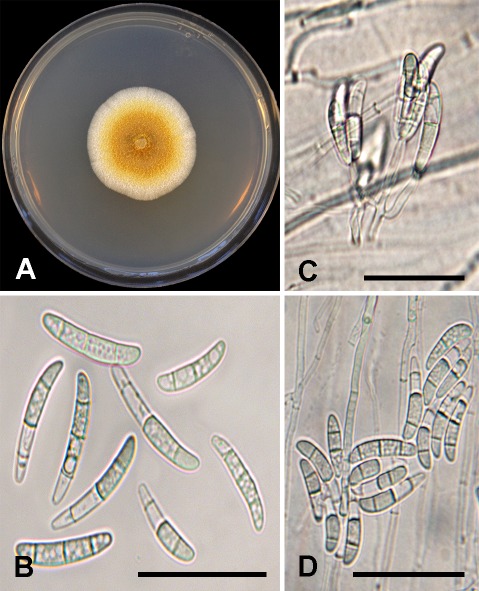

Thelonectria aurea D.P. Lawr. & Trouillas, sp. nov. MycoBank MB829441. Figs 1, 6.

Fig. 6.

Thelonectria aurea sp. nov. (holotype BPI 910948, ex-type culture CBS 145584). A. Fourteen-day-old PDA culture. B. Macroconidia. C. Conidiophores and conidia. D. Macroconidia. Scale bars: B = 35 μm; C–D = 30 μm.

Etymology: aurea, named after the golden color of the colony produced on PDA.

Sexual morph: Undetermined. Asexual morph: Phialides mostly emerge directly from hyphae some are borne apically on irregularly branching groups of cells, cylindrical to slightly swollen, (11–)15(–18.5) μm long, (2–)2(–2.5) μm wide at the base and (1.5–)1.5(–2.5) μm towards the apex. Macroconidia on SNA produced predominately in concentric rings of slimy pulvinate masses, 3-septate, cylindrical to slightly fusiform with curved or rounded end cells, (24–)31(–37) × (4–)4.5(–5.5) μm, most segments have internal spherical occlusions. Microconidia and chlamydospores not observed on SNA.

Culture characteristics: Colonies after 14 d average 37.4 mm on PDA, medium- to slow-growing with even margin expansion. Center of colony on PDA is pure yellow to amber with some aerial hyphae and margin of colony is white and flat with sparse aerial hyphae emerging directly behind the advancing front. Optimal growth temperature was 25 °C.

Hosts: Olea europaea, Pistacia vera, Prunus avium, Prunus persica, and Vitis vinifera.

Distribution: Glenn, Fresno, and Madera Counties, California, USA.

Specimen examined: USA, California, Glenn County, isolated from symptomatic roots (necrotic lesions and black discoloration of the root cortex, epidermis, and vascular tissues) of Olea europaea, 13 Apr. 2017, F.P. Trouillas (holotype BPI 910948, culture ex-type CBS 145584).

Additional material examined: USA, California, Fresno County, isolated from symptomatic roots (necrotic lesions and black discoloration of the root cortex, epidermis, and vascular tissues) of Prunus persica (peach), 19 Sept. 2017, M.T. Nouri (KARE1923).

Notes: Thelonectria aurea clusters in a well-supported clade closely related to T. truncata and distantly related to members of the T. coronata and T. veuillotiana complexes. Thelonectria aurea only produced three-septate conidia which were on average, (31 × 4.5 μm), shorter than the minimum length reported for T. truncata three-septate conidia, (40.5–)46.9(–71.4) μm (Salazar-Salgado et al. 2012), thereby morphologically distinguishing the two taxa.

DISCUSSION

This study represents the first comprehensive molecular phylogeny to elucidate the identity and diversity of cylindrocarpon-like fungi associated with black foot disease of grapevine and root rot symptoms in other diverse economically important perennial fruit and nut crops in California. Multi-locus sequence typing along with morphological studies unveiled the identity of 10 previously described pathogenic cylindrocarpon-like species associated with diseased roots of perennial crops in California. These included Campylocarpon fasciculare, grape; Dactylonectria alcacerensis, grape; D. ecuadoriensis, olive; D. macrodidyma, almond, grape, pistachio, and olive; D. novozelandica, cherry, grape, and pistachio; D. torresensis, pistachio; D. valentina, olive; Ilyonectria capensis, peach; I. liriodendri, cherry, kiwi, and walnut; and I. robusta, olive. All associations except C. fasciculare on grape (Halleen et al. 2004, Correia et al. 2013, Akgul et al. 2014), D. novozelandica on grape (Cabral et al. 2012a, b), and I. liriodendri on kiwi (Erper et al. 2011) are reported from California, to the best of our knowledge, for the first time.

Morphological assessments revealed that Dactylonectria and Ilyonectria conidia are very similar in terms of shape, septation, and dimensions amongst and within both genera as noted in previous studies (Cabral et al. 2012a, b, Lombard et al. 2014). Both colony and conidial morphology have been extensively used to delimit fungal species associated with black foot disease of grapevine (Halleen et al. 2004, Petit & Gubler 2005, Schroers et al. 2008), some with limited success. For example, Halleen et al. (2004) noticed cultural and conidial differences amongst a collection of fungi isolated from asymptomatic and black foot affected grapevines from nurseries and vineyards in major viticultural areas of the world including Australia, France, New Zealand, and South Africa. Results of morphological observations revealed that Campylocarpon with large robust macroconidia that are mostly 3–4-septate, cylindrical, and slightly to moderately curved could be easily distinguished from those of I. destructans (formerly C. destructans) and D. macrodidyma (formerly C. macrodidymum/I. macrodidyma). Furthermore, Halleen et al. (2004) stated that molecularly determined I. destructans isolates were morphologically indistinguishable from previously described I. destructans isolates (Booth 1966, Samuels & Brayford 1990) and thus distinguishable from D. macrodidyma macroconidia which are characterized as 1–3(–4)-septate, straight or sometimes slightly curved, cylindrical or typically minutely widening toward the tip, with apical cell typically slightly bent to one side. Petit & Gubler (2005) revealed that the cylindrocarpon-like fungi I. destructans and D. macrodidyma (previously known as Cylindrocarpon macrodidymum/Ilyonectria macrodidyma) associated with black foot disease in California were genetically distinct based on three separate loci (ITS, mitochondrial small subunit, and TUB2), however morphological comparisons of the two species could not distinguish them confidently. The statistical analysis by Petit & Gubler (2005) revealed that D. macrodidyma conidia were significantly larger than those of I. destructans, but the mean values of conidial dimensions were similar and their distributions largely overlapped, therefore they determined that conidial characters were unable to properly disentangle these two species (which have been shown to reside in different genera), which is in strong accord with Cabral et al. (2012)a, b and Lombard et al. (2014) who strongly suggests that molecular data are necessary to obtain a confident species diagnosis when working with species in the genera Dactylonectria and Ilyonectria.

Several gene fragments namely, ITS, TEF1, and TUB2, have been used extensively in molecular phylogenetic analyses of plant pathogenic ascomycetes either as single-gene or combined multi-gene analyses. However, some serious conflicts were disclosed in this study by comparing the commonly employed three-gene dataset, ITS+TEF1+TUB2, versus other three-gene combinations (Table 3) and the four-gene dataset (ITS+TEF1+TUB2+HIS) in relation to accurate identification of Dactylonectria species. In this study, the three-gene analyses of ITS+TEF1+TUB2 provided low to moderate support for D. ecuadoriensis (74 % / 72 %), D. macrodidyma (76 % / 82 %), D. valentina (77 % / 78 %), and no support for D. novozelandica (<70 %/<70 %). Similarly, Úrbez-Torres et al. (2014) recovered Dactylonectria isolates from black foot disease associated grapevines in British Columbia, Canada, however their identity remains unresolved, based on the analysis of the three-gene dataset (ITS+TEF1+TUB2).

The HIS locus has been shown to be a powerful marker for species delimitation especially within cylindrocarpon-like asexual morphs (Cabral et al. 2012a, b) by resolving the former ‘macrodidyma’ species-complex into four very closely related lineages (Cabral et al. 2012b) and close relatives of D. vitis described from Ecuador (D. ecuadoriensis) and Spain (D. valentina), respectively (Gordillo et al. 2017, Mora-Sala et al. 2018). Results from this study corroborate the increased accuracy of Dactylonectria species identification by incorporating the HIS locus into multi-locus analyses that include TEF1 and TUB2 data (Cabral et al. 2012a, b).

These results strongly suggest that the previous identifications of Dactylonectria macrodidyma (former Cylindrocarpon macrodidymum/Ilyonectria macrodidyma) isolates associated with black foot disease of grapevine (Petit & Gubler 2005, Petit et al. 2011, Úrbez-Torres et al. 2014) and olive root rot (Úrbez-Torres et al. 2012), at least in North America, are uncertain. Most of the aforementioned studies were conducted before the utility of HIS was widely realized; therefore, the species diversity of Dactylonectria in North America has likely been underestimated. For instance, Cabral et al. (2012a, b) revealed that isolates previously identified as “Cylindrocarpon marcrodidymum”, from black foot affected vines in California, indeed comprised three phylogenetic species recognized in the ‘macrodidyma’ species-complex (i.e. D. macrodidyma, D. novozelandica, and D. torresensis). The current study has revealed that the fourth species in the ‘macrodidyma’ species-complex, D. alcacerensis, is also present in California vineyards. All previously reported isolates/species in this complex, in North America, will need to be re-examined with the addition of the HIS locus to refine and confirm their species identity. Similarly, the identification of Cylindrocarpon destructans (i.e. Ilyonectria destructans/radicicola), originally identified as the causal agent of black foot disease (Maluta & Larignon 1991), in North America are likely erroneous. Cylindrocarpon destructans isolates previously identified from French and Portuguese vineyards were later shown to actually be I. liriodendri, based on morphological and molecular data (Halleen et al. 2006). The same results have also been reported from vineyards in Spain, (Alaniz et al. 2009), Australia (Whitelaw-Weckert et al. 2007), Uruguay (Abreo et al. 2010), and in California (Petit & Gubler 2007). Therefore, all previously collected isolates of C. destructans (syn. C. radicicola), at least in North America, should be re-examined in order to confirm their identity.

Like Halleen et al. (2004) we noticed morphological variation in appearances of cultures and micro-morphological assessments of conidia for some cylindrocarpon-like fungal isolates. A single isolate (KARE1838), now referred to as N. californica and a group of 13 isolates (KARE98, KARE1830–KARE1837, KARE1839–KARE1841, and KARE1923), now referred to as T. aurea, were also evaluated morphologically and phylogenetically. Colony morphology, macroconidial characteristics, and lack of microconidia and chlamydospore production of isolate KARE1838 resembled members of the genus Neonectria (Booth 1966, Rossman et al. 1999, Chaverri et al. 2011). Neonectria californica clustered strongly in the genus Neonectria based on the three-gene combined analyses (ITS+TEF1+TUB2) with no evidence of systematic error. Typically, Neonectria species produce straight, cylindrical, 5-septate macroconidia with rounded end cells, microconidia or chlamydospores but not both. Neonectria species are known from temperate regions generally associated with woody substrata and may cause cankers, and are rarely found in the soil (Chaverri et al. 2011), which may explain why we only recovered a single isolate of N. californica associated with symptomatic pistachio tree roots. The closest relatives of N. californica (i.e. N. neomacrospora, N. major, and N. ditissima) have been associated with bark cankers of broad-leaf or coniferous trees in Europe and in North America (Castlebury et al. 2006). Neonectria ditissima has been shown to be highly pathogenic to apple and pear trees causing cankers that limit the longevity and productivity of orchards (Castlebury et al. 2006). Therefore, it is likely that the new species, N. californica, recovered in this study may be an opportunistic pathogen of woody substrates including plant roots. Future pathogenicity trials will test this hypothesis.

Members of the genus Thelonectria are cosmopolitan and abundant in temperate, subtropical, and tropical regions including the Mediterranean-like climate in California with mild to cool, wet, winter seasons and hot and dry during the summer months. Thelonectria aurea resembles other Thelonectria species except that only 3-septate macroconidia were observed, whereas many other Thelonectria species produce, on average, 5-septate macroconidia with rounded end cells that may superficially resemble Campylocarpon species (Chaverri et al. 2011). This has led some authors to speculate that these two genera are closely related (Halleen et al. 2004). Indeed, Lombard et al. (2015) provided strong evidence that the cylindrocarpon-like genera Dactylonectria, Ilyonectria, and Neonectria were more closely related to each other than to either Campylocarpon or Thelonectria. Chaverri et al. (2011) stated that the only morphological differences between Campylocarpon and Thelonectria were the number of septa in macroconidia with four in Campylocarpon and five in Thelonectria, however this has now been shown to be an inadequate diagnostic character for these fungi as T. lucida, T. trachosa, and T. truncata have been reported to produce 3-sepatate macroconidia (Salgado-Salazar et al. 2012), and now too T. aurea. Molecular phylogenetic analyses easily separate these two genera based on DNA data.

Thelonectria species have been collected mainly from the bark of recently killed or dying broad-leaf and coniferous trees often causing small cankers and rarely occurring in the soil (Chaverri et al. 2011). However, Thelonectria aurea isolates recovered in this study were routinely isolated from symptomatic root rots of diverse fruit trees including almond, cherry, olive, peach, pistachio, and including grapevine. Until now, T. blackeriella, from Italy was the only reported Thelonectria species known to cause black foot disease in grapevines (Carlucci et al. 2017). However, Petit et al. (2011) reported an isolate of undetermined identity belonging to the “Neonectria mammoidea group” (now Thelonectria) based on DNA sequences of ITS and TUB2 from symptomatic grapevines in Canada and New York, USA. BLASTn analyses suggest that this undetermined species is T. olida or a close relative, which is, interestingly, sister to T. blackeriella. Thelonectria aurea seems to have a broad host range as suggested by the isolation of this fungus from five different perennial cropping systems in central California.

This study has resulted in several new putative fungal-host associations across diverse perennial crops in California. This is particularly alarming as some of these associations may likely represent emerging or re-emerging threats to sustainable crop production in California. Future pathogenicity trials will attempt to elucidate the virulence, host ranges, and host preferences as several cylindrocarpon-like species were isolated from different host plants, thereby contributing to a better understanding of cylindrocarpon-like fungal ecology and natural history.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the California Cherry Board, the California Pistachio Research Board, and the Almond Board of California for financial support.

REFERENCES

- Abreo ES, Martínez L, Bettucci L, et al. (2010). Morphological and molecular characterization of Campylocarpon and Cylindrocarpon spp. associated with black foot disease of grapevines in Uruguay. Australasian Plant Pathology 39: 446–452. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello D, Polizzi G, Crous PW, et al. (2017). Pleiocarpon gen. nov. and a new species of Ilyonectria causing basal rot of Strelitzia reginae in Italy. IMA Fungus 8: 65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Adawi AO, Barnes I, Khan IA, et al. (2014). Clonal structure of Ceratocystis manginecans populations from mango wilt disease in Oman and Pakistan. Australasian Plant Pathology 43: 393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Agustí-Brisach C, Armengol J. (2013). Black-foot disease of grapevine: an update on taxonomy, epidemiology and management strategies. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 1: 245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Akgül DS, Savaş NG, Önder S, et al. (2014). First report of Campylocarpon fasciculare causing black foot disease of grapevine in Turkey. Plant Disease 98: 1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaniz S, Armengol J, León M, et al. (2009). Analysis of genetic and virulence diversity of Cylindrocarpon liriodendri and C. macrodidymum associated with black foot disease of grapevine. Mycological Research 113: 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaniz S, León M, Vicent A, et al. (2007). Characterization of Cylindrocarpon species associated with black foot disease of grapevine in Spain. Plant Disease 91: 1187–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger J, Esterio M, Pérez I. (2007). First report of black foot disease of grapevine caused by Cylindrocarpon macrodidymum in Chile. Plant Disease 91: 470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat RG, Schmidt LS, Browne GT. (2011). Quantification of Cylindrocarpon sp. in roots of almond and peach trees from orchards affected by Prunus replant disease. Phytopathology 101: S15. [Google Scholar]

- Booth C. (1966). The genus Cylindrocarpon. Mycological Papers 104: 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Brayford D, Honda BM, Mantiri FR, et al. (2004). Neonectria and Cylindrocarpon: the Nectria mammoidea group and species lacking microconidia. Mycologia 96: 572–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral A, Groenewald JZ, Rego C, et al. (2012a). Cylindrocarpon root rot: multi-gene analysis reveals novel species within the Ilyonectria radicicola species complex. Mycological Progress 11: 655–688. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral A, Rego C, Nascimento T, et al. (2012b). Multi-gene analysis and morphology reveal novel Ilyonectria species associated with black foot disease of grapevines. Fungal Biology 116: 62–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci A, Francesco LO, Mostert L, et al. (2017). Occurrence fungi causing black foot on young grapevines and nursery rootstock plants in Italy. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 56: 10–39. [Google Scholar]

- Castlebury LA, Rossman AY, Hyten AS. (2006). Phylogenetic relationships of Neonectria/Cylindrocarpon on Fagus in North America. Botany 84: 1417–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chaverri P, Salgado C, Hirooka Y, et al. (2011). Delimitation of Neonectria and Cylindrocarpon (Nectriaceae, Hypocreales, Ascomycota) and related genera with cylindrocarpon-like anamorphs. Studies in Mycology 68: 57–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia KC, Câmara MP, Barbosa MA, et al. (2013). Fungal trunk pathogens associated with table grape decline in North-eastern Brazil. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 52: 380–387. [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Groenewald JZ, Risède JM, et al. (2004). Calonectria species and their Cylindrocladium anamorphs: species with sphaeropedunculate vesicles. Studies in Mycology 50: 415–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erper I, Agustí-Brisach C, Tunali B, et al. (2013). Characterization of root rot disease of kiwifruit in the Black Sea region of Turkey. European Journal of Plant Pathology 136: 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- González CD, Chaverri P. (2017). Corinectria, a new genus to accommo-date Neonectria fuckeliana and C. constricta sp. nov. from Pinus radiata in Chile. Mycological Progress 16: 1015–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Gordillo A, Decock C. (2017). Cylindrocarpon-like (Ascomycota, Hypocreales) species from the Amazonian rain forests in Ecuador: additions to Campylocarpon and Dactylonectria. Cryptogamie Mycologie 38: 409–35. [Google Scholar]

- Halleen F, Fourie PH, Crous PW. (2006). A review of black foot disease of grapevine. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 45: 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Halleen F, Schroers HJ, Groenewald JZ, et al. (2004). Novel species of Cylindrocarpon (Neonectria) and Campylocarpon gen. nov. associated with black foot disease of grapevines (Vitis spp.). Studies in Mycology 50: 431–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence DP, Travadon R, Nita M, et al. (2017). TrunkDiseaseID.org: A molecular database for fast and accurate identification of fungi commonly isolated from grapevine wood. Crop Protection 102: 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard L, Van der Merwe NA, Groenewald JZ, et al. (2014). Lineages in Nectriaceae: re-evaluating the generic status of Ilyonectria and allied genera. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 1: 515–532. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard L, Van der Merwe NA, Groenewald JZ, et al. (2015). Generic concepts in Nectriaceae. Studies in Mycology 80: 189–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP, Maddison DR. (2015). Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 3.04. http://mesquiteproject.org. [Google Scholar]

- Maluta DR, Larignon P. (1991). Pied-Noir: Mieux vaut prevenir. Viticulture 11: 71–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mantiri FR, Samuels GJ, Rahe JE, et al. (2001). Phylogenetic relationships in Neonectria species having Cylindrocarpon anamorphs inferred from mitochondrial ribosomal DNA sequences. Canadian Journal of Botany 79: 334–340. [Google Scholar]

- Marek S, Yaghmour MA, Bostock RM. (2013). Fusarium spp., Cylindrocarpon spp., and environmental stress in the etiology of a canker disease of cold-stored fruit and nut tree seedlings in California. Plant Disease 97: 259–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi H, Alaniz S, Banihashemi Z, et al. (2009). Characterization of Cylindrocarpon liriodendri associated with black foot disease of grapevine in Iran. Journal of Phytopathology 157: 642–645. [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Sala B, Cabral A, León M, et al. (2018). Survey, identification, and characterization of cylindrocarpon-like asexual morphs in Spanish forest nurseries. Plant Disease 102: 2083–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirenberg HI. (1976). Untersuchungen über die morphologische und biologische Differenzierung in der Fusarium-Sektion Liseola. Mitt Biol Bundesanst Land-Forstw Berlin-Dahlem 169: 1–117. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Cigelnik E. (1997). Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungus Fusarium are nonorthologous. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 7: 103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit E, Barriault E, Baumgartner K, et al. (2011). Cylindrocarpon species associated with black-foot of grapevine in northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 62: 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Petit E, Gubler WD. (2005). Characterization of Cylindrocarpon species, the cause of black foot disease of grapevine in California. Plant Disease 89: 1051–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit E, Gubler WD. (2007). First report of Cylindrocarpon liriodendri causing black foot disease of grapevine in California. Plant Disease 91: 1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit EL, Gubler WD. (2013). Black foot disease. In: Grape Pest Management, third edition (Bettiga LJ, ed). University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, USA: 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner RW. (1970). A mycological colour chart. CMI and British Mycological Society, Kew, Surrey, England. [Google Scholar]

- Rego C, Oliveira H, Carvalho A, et al. (2000). Involvement of Phaeoacremonium spp. and Cylindrocarpon destructans with grapevine decline in Portugal. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 39: 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman AY, Samuels GJ, Rogerson CT, et al. (1999). Genera of the Bionectriaceae, Hypocreaceae and Nectriaceae (Hypocreales, Ascomycetes). Studies in Mycology 42: 1–248. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz S, Charlier A, Chandelier A. (2017). First report of Neonectria neomacrospora on Abies grandis in Belgium. New Disease Reports 36: 17. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado-Salazar C, Rossman A, Samuels GJ, et al. (2012). Multigene phylogenetic analyses of the Thelonectria coronata and T. veuillotiana species complexes. Mycologia 104: 1325–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado-Salazar C, Rossman AY, Chaverri P. (2016). The genus Thelonectria (Nectriaceae, Hypocreales, Ascomycota) and closely related species with cylindrocarpon-like asexual states. Fungal Diversity 80: 411–455. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels GJ, Brayford D. (1994). Species of Nectria (sensu lato) with red perithecia and striate ascospores. Sydowia 46: 75–161. [Google Scholar]

- Scheck HJ, Vasquez SJ, Gubler WD, et al. (1998). First report of black-foot disease, caused by Cylindrocarpon obtusisporum, of grapevine in California. Plant Disease 82: 448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroers HJ, Žerjav M, Munda A, et al. (2008). Cylindrocarpon pauciseptatum sp. nov., with notes on Cylindrocarpon species with wide, predominantly 3-septate macroconidia. Mycological Research 112: 82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert KA, McMullen CR, Yee D, et al. (2003). Molecular differentiation and detection of ginseng-adapted isolates of the root rot fungus Cylindrocarpon destructans. Phytopathology 93: 1533–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. (2003). PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony. (*and other methods). Version 4.0b10. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, et al. (2013). MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewoldemedhin YT, Mazzola M, Mostert L, et al. (2011). Cylindrocarpon species associated with apple tree roots in South Africa and their quantification using real-time PCR. European Journal of Plant Pathology 129: 637–651. [Google Scholar]

- Traquair JA, White GP. (1992). Cylindrocarpon rot of fruit trees in cold storage. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 14: 310–314. [Google Scholar]

- Úrbez-Torres JR, Haag P, Bowen P, et al. (2014). Grapevine trunk diseases in British Columbia: incidence and characterization of the fungal pathogens associated with black foot disease of grapevine. Plant Disease 98: 456–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Úrbez-Torres JR, Peduto F, Gubler WD. (2012). First report of Ilyonectria macrodidyma causing root rot of olive trees (Olea europaea) in California. Plant Disease 96: 1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale A, Aiello D, Guarnaccia V, et al. (2012). First report of root rot caused by Ilyonectria (= Neonectria) macrodidyma on avocado (Persea americana) in Italy. Journal of Phytopathology 160: 156. [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, et al. (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications (MA Innis, DH Gelfand, JJ Sninsky, et al., eds): 315–322. San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitelaw-Weckert MA, Nair NG, Lamont R, et al. (2007). Root infection of Vitis vinifera by Cylindrocarpon liriodendri in Australia. Australasian Plant Pathology 36: 403–406. [Google Scholar]

- Zwickl DJ. (2006). Genetic algorithm approaches for the phylogenetic analysis of large biological sequence datasets under the maximum likelihood criterion. Ph.D. dissertation. Department of Integrative Biology, University of Texas-Austin, USA. [Google Scholar]