Abstract

In cells asparagine/N-linked glycans are added to glycoproteins co-translationally, in an attachment process that supports proper folding of the nascent polypeptide. We find that following pruning of N-glycan by the amidase PNGase F, the principle influenza vaccine antigen and major viral spike protein hemagglutinin (HA), spontaneously re-attached N-glycan to its de-N-glycosylated positions when the amidase was removed from solution. This reaction, which we term N-glycanation, was confirmed by site-specific analysis of HA glycoforms by mass spectrometry prior to PNGase F exposure, during exposure to PNGase F, and after amidase removal. Iterative rounds of de-N-glycosylation followed by N-glycanation could be repeated at least 3 times, and was observed for other viral glycoproteins/vaccine antigens, including the envelope glycoprotein (Env) from HIV. Covalent N-glycan reattachment was non-enzymatic as it occurred in the presence of metal ions that inhibit PNGase F activity. Rather, N-glycanation relied on a non-covalent assembly between protein and glycan, formed in the presence of the amidase, where linearization of the glycoprotein prevented retention and subsequent N-glycanation. This reaction suggests that under certain experimental conditions, some glycoproteins can organize self-glycan addition, highlighting a remarkable self-assembly principle that may prove useful for re-engineering therapeutic glycoproteins such as influenza HA or HIV Env, where glycan sequence and structure can markedly affect bioactivity and vaccine efficacy.

Keywords: deglycosylation, amidase, N-glycanation, spontaneous, N-glycan, reattachment, NXS/T sequon, glycoprotein, test tube, self-organizing

Introduction

Asparagine (Asn) N-glycosylation is a universally conserved post-translational modification, occurring in all three domains of life - eukaryotes, bacteria and archaea1–3. In metazoans and many eukaryotes, N-glycans are formed as β-linkages between acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and asparaginyl residues within NXS/T sequons2–4. Energetically, the attachment process is largely driven by enzymatic cleavage of a high energy GlcNAc-phosphate bond within an oligosaccharide donor molecule5–7. But glycan attachment is also co-translational and thermodynamic modeling predicts coupling between folding of the nascent polypeptide chain and N-glycan addition8–10. In this study, we uncovered a previously unrecognized reaction that experimentally highlights a link between protein structure and the formation of the GlcNAc-β-Asn linkages.

After treating the principle vaccine influenza vaccine antigen and major viral spike glycoprotein hemagglutinin (HA) with PNGase F, an amidase that catalyzes the cleavage of the N-linked bond converting Asn to Asp11–14, we found that the de-N-glycosylated HA spontaneously transitioned back to its native N-glycanated state when PNGase F was removed from solution. Transitioning between these two states was non-enzymatic and could be cycled repeatedly. During this process, reattachment occurred at the same PNGase F-deaminated positions and was preceded by non-covalent retention of the cleaved glycan. If HA was linearized to destroy protein conformation, then both retention and subsequent reattachment of N-glycan was prevented. N-glycanation was also observed for HIV envelope glycoprotein (Env), an unrelated viral glycoprotein/vaccine antigen15, 16. This new reaction, which we term N-glycanation, suggests that under certain experimental conditions, aspects of three-dimensional protein structure may serve to modulate and organize N-glycan addition. Moreover, N-glycanation points a potential means of re-engineering glycan sequences of therapeutic glycoproteins in the test tube, such as influenza HA or HIV Env, where glycan structure and sequence regulates bioactivity and vaccine efficacy17–21.

Materials and Methods

Recombinant proteins

All proteins were expressed in 293F cells using pVRC8400, a plasmid containing the CMV IE Enhancer/Promoter, HTLV-1 R Region and Splice Donor site, and the CMV IE Splice Acceptor site upstream of the open reading frame22 The soluble trimeric configurations of the trimerized HA ectodomains from A/New Caledonia/20/1999 (H1N1); A/Indonesia/5/2005 (H5N1); and A/Wisconsin/67/2005 (H3N2) were expressed in 293F cells and purified using a combination of affinity and size exclusion chromatography as described previously22–24. In this study we focused on the H1 HA trimer, referred throughout as HA trimer. The hemagglutinin trimers from H3N2 and H5N1 are denoted H3 and H5. To prevent aggregation of the trimers, they were co-transfected with influenza strain matched-neuraminidase (NA)22. For experiments with trimers bearing terminal sialyl-oligosaccharide (SA), they were purified with the Y98F substitution that prevents SA binding but maintains the structural integrity of the binding site23, 25. The gp120 core of HIV Env from clade B virus (strain HT593.1) was expressed and purified on a 17b antibody column, as described previously15, 16. Fetal bovine fetuin was obtained from Sigma (Cat#F2379, Sigma).

Spontaneous reformation of PNGase F substrate by influenza HA

Purified influenza H1 HA trimer was first de-N-glycosylated under non-denaturing conditions using commercial PNGase F tagged with a chitin-binding domain (CBD) (Remove-iT® PNGase F, Cat# P0706S, New England BioLabs) (=CBD-PNGase F) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (0.72 mg/mL HA, 40 000 units/mL CBD-PNGase F, 50 mM Na3PO4, pH 7.5; 24 h incubation at 37°C). Chitin magnetic beads (Cat# E8036S, New England BioLabs) equilibrated CBD binding buffer (500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCI, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8) were incubated with the deglycosylation reaction (1 hr at 4°C, RotoFlex Plus Tube Rotator, Argos Technologies) and then applied to deplete CBD-PNGase from solution via separation on a magnetic column (NEB cat. S1509), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. To ensure separation of HA and CBD-PNGase F, the reaction was further separated on a Superdex 200 10/300 size exclusion column (SEC) using an automated FPLC system (Acta pure 2L, GE). Each step (input, de-N-glycosylation, post-PNGase F removal) was visualized by SDS PAGE where gels were stained with GelCode Blue (Thermo Scientific, MA). To visualize protein glycan, the gels were also stained using the periodate-acid Schiff (PAS) reagent method using a commercially available glycoprotein staining kit (Pierce™ Glycoprotein Staining Kit, ThermoFisher). To confirm spontaneous reformation of PNGase F substrate, cycles of CBD-PNGase F exposure and removal were performed on the same HA preparation using the same conditions.

The above experiments were performed with recombinant HA trimer in which the terminal sialyl-oligosaccharide (SA) of its glycan chains was cleaved by co-expression with neuraminidase, a procedure that prevents in solution aggregation of the trimers due to HA lectin activity for SA, the receptor for influenza virus22, 25. To perform the procedure with terminal SA present, we generated Y98F HA a mutation which prevents SA-binding but maintains the integrity of the HA receptor binding site (RBS)25. In this case, we monitored HA deglycosylation and then PNGase F substrate reformation by western blotting with SNA-lectin, as described previously26, 27. Briefly, SDS PAGE was performed as above and the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose (Trans-Blot® SD Semi-Dry Transfer Cell, BioRad) and the blots were then blocked in Odyssey® Blocking buffer (cat. 927–40100, LI-COR). The blots were then incubated with biotinylated SNA (cat. B-1305, Vector Labs; 2 μg/ml in blocking buffer), washed 3x in PBS, and then incubated with streptavidin-conjugated IRDye800CW (cat. 926–32230, LI-COR; 1/5000 in blocking buffer). The blots were then washed 3x with PBS and developed on Odyssey® CLx Imaging System (LI-COR).

Proteome Analysis of Hemagglutinin A by LC-MS

Gel bands for HA at each stage (Pre-treated, CBD-PNGase F treated, and after amidase removal; for the latter, we ensured separation from CBD-PNGase F, using chitin affinity beads followed by SEC) were excised, cut into smaller pieces and transferred into 1.5 mL tubes. Gel bands were destained with 500 μL 50% acetonitrile/50% 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 8.1, mixed at 850 RPM for 10 min at room temperature (RT). Buffer was removed using a gel loading pipet tip and the process was repeated until no further stain was removed. Bands were washed and hydrated with 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 8.1 for 5 min, mixed at 850 RPM at RT and subsequently dehydrated with 100% acetonitrile for 5 min at 850 RPM at RT. Bands were reduced with 10 mM DTT 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 8.1, incubated 30 min mixing at 1000 RPM at 37 °C, dehydrated with 100% acetonitrile (5 min, 1000 RPM, RT) and then alkylated with 30 mM iodoacetamide 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate 30 min at 1000 RPM at RT in the dark. Prior to trypsin digestion, gel bands were dehydrated with 100% acetonitrile 5 min at 1000 RPM at 37 °C. Trypsin was diluted to 14 ng/μL in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, added to each gel band in sufficient volume to cover each gel piece (~ 50 μL) and incubated overnight at 850 RPM and 37°C (~ 16 h). On the next day, a second volume of 14 ng/μL trypsin solution was added to cover the bands (~50 μL) and incubated 1 h at 850 RPM and 37 °C. After collecting the supernatant, three subsequent extractions with 50% acetonitrile / 50% 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate were performed to extract the peptide bands. For each extraction step, the solvent was incubated for 10 min at 850 RPM at RT. The peptide bands were further treated with 100% acetonitrile until completely dehydrated. All of the acetonitrile supernatants were added to the peptide extracts, frozen and dried by vacuum centrifugation. Dried peptide extracts were resuspended in 40 μL 3% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid and desalted using a 3 punch Empore C18 packed StageTip. StageTips were washed and equilibrated with 50 μL 90% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA followed by 50 μL 0.1% TFA prior to use. Samples were loaded onto StageTips, washed with 2 × 50 μL 0.1% TFA and then eluted with 2 × 30 μL 40 % acetonitrile/0.1%TFA. Desalted peptide extracts were transferred to HPLC vials, frozen, dried using vacuum centrifugation and stored at −80 °C until LC-MS/MS analysis.

LC MS/MS analysis

Samples were resuspended in 10 μL 3% acetonitrile/5% acetic acid, mixed and centrifuged briefly (~30s) and analyzed on a QExactive mass spectrometer (Thermo) equipped with a Proxeon Easy-nLC 1200 and a custom built nanospray source (James A. Hill Instrument Services). MS acquisition was performed using Xcalibur software version 3.0.63. Samples were injected (40% of sample) onto a 75 μm ID PicoFrit column (New Objective) manually packed to 20 cm with Reprosil-Pur C18 AQ 1.9 μm media (Dr. Maisch) and heated to 50 °C. MS source conditions were set as follows: spray voltage 2000, capillary temperature 250, S-lens RF level 50. A single Orbitrap MS scan from 300 to 1800 m/z at a resolution of 70 000 with AGC set at 3e6 was followed by up to 12 MS/MS scans at a resolution of 17 500 with AGC set at 5e4. MS/MS spectra were collected with normalized collision energy of 25 and isolation width of 2.5 amu. Dynamic exclusion was set to 20 s and peptide match was set to preferred. Mobile phases consisted of 3% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid as solvent A, 90% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid as solvent B. Flow rate was set to 200 nL/min throughout the gradient, 2% - 6% B in 1 min, 6% - 30% B in 84 min, 30% - 60% B in 9 min, 60% - 90% B in 1 min with a hold at 90% B for 5 min.

MS data were searched against a UniProt database containing human reference proteome sequences downloaded from the UniProt web site on October 17, 2014 with redundant sequences removed using Byonic™ software v2.16.11 (Protein Metrics). A set of common laboratory contaminant proteins (150 sequences) and the expressed Hemagglutinin A H1 sequence were appended to this database. Search parameters: cleavage residues RK, fully specific termini, 1 missed cleavage, QTOF/HCD fragmentation, 20 ppm precursor and fragment tolerance. Fixed modifications: carbamidomethylation at cysteine. Variable modifications: N-term Gln -> pyroGlu, N-term Glu -> pyroGlu, ammonia-loss, deamidation, oxidation of methionine and tryptophan, dethiomethyl methionine, decarbamidomethyl cysteine, C-term sodiation, and 38 N-linked glycan common biantennary modifications. Spectra were further searched against a decoy database and the database match threshold was set to 1% FDR at the protein level. The specific sugar units are based on the known biosynthesis of N-linked sugars as the MS and MS/MS alone does not distinguish/identify the specific HexNAc, Hexose, Deoxyhexose, etc. that are present.

Precursor masses of identified unmodified and modified peptides, including all identified glycoforms, were extracted using XCalibur Qualbrowser software (Thermo) 3.0.63. Peak height intensity for each precursor m/z in the extracted ion chromatogram (XIC) was tabulated and used to estimate the relative peptide abundance in each sample. The intensity values were normalized for the amount of HA in each lane using a non-glycosylated HA peptide, IDGSGYIPEAPR. To estimate glycan reoccupancy, the MS response for each detected glycoform was divided by the normalized MS response for the corresponding peptide in the pre-treatment samples. The in-gel digestion LC-MS workflow is described in Figure S1.

To evaluate glycan re-occupancy, the following calculations were made. The HA gel bands were designated as Band 1 (Pre-treatment), Band 2 (PNGase F treated) and Band 3 (after amidase removal) (Figure S1). The normalized intensity MS signal for each glycosylated form of the peptide (e.g., [+1445], [+1607], [+1769], etc.) identified in Band 2 (when detected or signal given as 0) was divided by the corresponding MS signal in Band 1 (equation 1). The same calculation was performed for Band 3 (equation 2). This was calculated for each HA peptide identified using Byonic that contained a consensus N-linked glycosylation consensus motif (NXS/T).

| Eq. 1 |

| Eq. 2 |

These resulting ratios demonstrate the loss and subsequent re-attachment of glycans to each peptide as compared to those in Band 1, or untreated HA. A complete work through for this glycan analysis pipeline is presented in Figure S1.

Assaying for non-covalent glycan complex formation

De-N-glycosylation of HA was performed under non-denaturing conditions using commercially available PNGase F (no affinity tag) (Cat # P0705L, New England BioLabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (0.72 mg/mL HA, 40 000 units/ml PNGase F, 50 mM Na3PO4, pH 7.5; 24 h incubation at 37°C). We then separated the same reaction mixture by SDS PAGE or by blue native PAGE as previously described28. The gels were then stained with Gel Code Blue to detect protein or the PAS reagent method to detect glycan, as described above. To ensure that the PAS signal could be precisely compared with the Gel Code Blue signal, the Gel Code blue stain was applied first, then removed (microwave 2 min), following which time the PAS staining for glycan was applied.

N-glycanation during size exclusion chromatography

To test if the non-covalently bound amidase-liberated carbohydrate reformed PNGase F substrate when physically separated from the amidase, the HA-PNGase F de-N-glycosylation reaction was immediately separated by SEC (no pre-in solution depletion using affinity beads) using a Superdex 200 10/300 size exclusion column which would separate free-glycan from HA and also HA away from PNGase F. The separated HA was then separated by SDS PAGE and re-exposed to PNGase F. These products were then evaluated by SDS PAGE with Gel Code Blue and PAS-staining.

Conformational requirements for N-glycanation

To evaluate the contribution of conformational protein structure to non-covalent interactions with amidase-liberated glycan and the subsequent N-glycanation, we heat-denatured HA (100˚C for 30 min), and then deglycosylated with PNGase F. The substrates and products of the PNGase F deglycosylation reaction were first evaluated by native PAGE with GelCode Blue and PAS staining. The corresponding capacity for N-glycanation was evaluated by separating the denatured HA + PNGase F by SEC and monitoring the input and output HA by SDS-PAGE. To further explore this, we mixed HA trimer with heat denatured HA, deglycosylated the protein mixture together and then removed the PNGase F by SEC and analyzed the fractions by SDS PAGE.

N-glycanation in the presence of Mn2+

Given that N-glycanation could be also achieved on the size exclusion column (Superdex 200 10/300), we applied SEC to assay for N-glycanation in the presence of 1 mM Mn2+, where this metal ion concentration has been reported to inhibit the catalytic activity of PNGase F29. The purpose of this experiment was to rule out enzymatic contribution of PNGase F to the glycan reattachment process. For this, we obtained a commercial PNGase F prep that did not contain metal ion chelators (Agilent, cat. GKE-5016B) and performed the 24 h deglycosylation procedure on HA (as described earlier) but now in 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0 ± MnCl2. After confirming the inhibitory activity of Mn2+ (SDS PAGE with Gel Code Blue stain), we repeated the HA deglycosylation by PNGase F within 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, but in the absence of Mn+2. This reaction was then separated into two samples: 1) control deglycosylated HA and 2) deglycosylated HA that was then adjusted to 1 mM MnCl2. We then then performed SEC where the FPLC system and column was pre-equilibrated with either 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0 (for control sample) or 50 mM Tris, 1 mM MnCl2, pH 8.0 (for Mn2+ adjusted sample). In both cases, we observed a single peak on the chromatogram corresponding to HA trimer, which was then collected and evaluated by evaluated by SDS PAGE with Gel Code Blue stain.

N-glycanation in other viral glycoproteins / vaccine antigens

We used the SEC protocol to assay for N-glycosylation by other viral surface glycoproteins including distantly related H3 and H5 influenza trimers and also the unrelated glycoprotein HIV Env. The glycoprotein fetal bovine fetuin was also evaluated in parallel. Following PNGase F glycosylation and amidase separation by SEC (Superdex 200 10/300), we analyzed the pre-and post-treated glycoproteins by SDS PAGE with Gel Code Blue stain or PAS reagent method to detect glycan.

Results

N-glycanation as initially identified by SDS PAGE

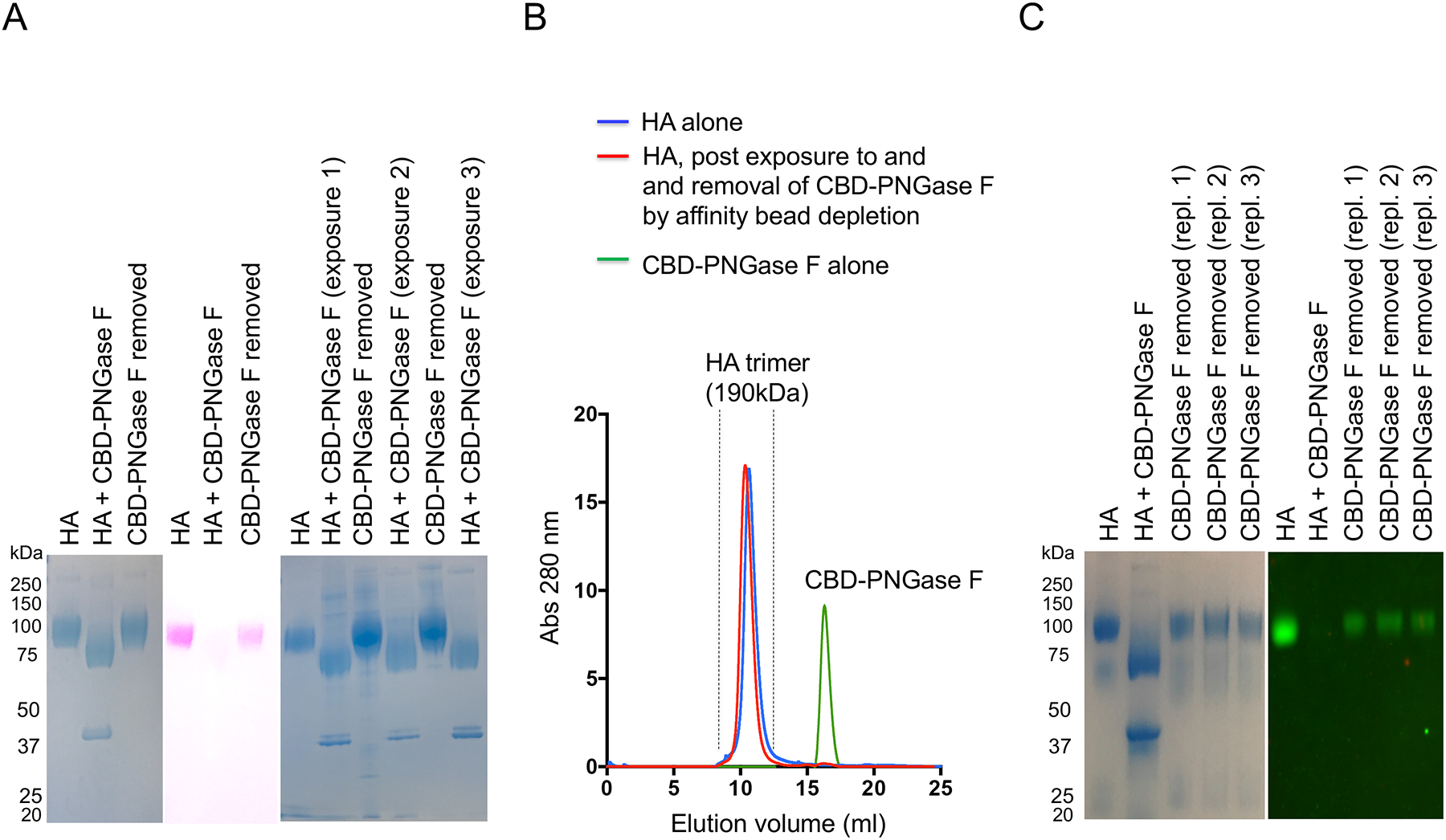

HA is a trimeric protein, assembled from protomers of ~65 kDa, which also bear the added mass of N-glycosylation13, 30. Protein N-glycans, including those of HA, have traditionally been analyzed following PNGase F de-N-glycosylation of denatured glycoprotein substrate11–14, 30, 31. We found that pruning HA with PNGase F under non-denaturing conditions resulted in a decrease in molecular mass of ~30 kDa and loss of detection using a specific stain for glycans (Figure 1A). We then removed the amidase from solution with magnetic chitin beads (PNGase F was affinity tagged with a chitin binding domain = CBD-PNGase). Amidase removal by this method was completed in less than two hours and the input/output forms of HA were immediately evaluated by SDS PAGE. Following removal of the amidase, we observed that HA returned to native electrophoretic mobility, reacquired sensitivity to glycan staining by the periodate-acid Schiff (PAS) reagent, and reacquired sensitivity to CBD-PNGase F (Figure 1A). Indeed, the same HA substrate could be passed through multiple cycles of de-N-glycosylation followed by electrophoretic recovery (Figure 1A), indicating a highly repeatable process in which CBD-PNGase F substrate was first enzymatically cleaved and then reformed. To further ensure that CBD-PNGase F had been separated from HA by our magnetic beads, we fractionated the mixture by size column chromatography (SEC) under non-denaturing conditions using a Superdex 200 10/300 column which resolves the size difference between these two proteins (Figure 1B). SEC revealed that both input the HA and the HA with reacquired CBD-PNGase F sensitivity had trimeric size (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. N-Glycanation as initially identified as spontaneous reformation of amidase substrate following cleavage by PNGase F, a reaction that could be cycled indefinitely.

(A) HA was de-N-glycosylated using chitin binding domain (CBD)-PNGase F, which when removed by magnetic chitin protein beads was concomitant with recovery in HA’s electrophoretic mobility (GelCode Blue staining), glycan stain (PAS) (pink), and reacquired sensitivity to CBD-PNGase F (three iterative cycles of de-N-glycosylation by amidase exposure + recovery after amidase removal are shown). (B) HA and ‘glycan recovered HA’ were also further separated by SEC (Superdex 200 10/300 column). (C) The recombinant HA was co-expressed with NA to cleave terminal SA, to prevent aggregation in solution. To assess the reformation of amidase substrate when terminal SA was present, Y98F HA trimer was used (GelCode Blue stain and western blot using SNA to detect SA).

The above experiments were performed with recombinant HA that was co-expressed with neuraminidase to cleave terminal sialyl-oligosaccharide (SA) on HA. This prevents in solution aggregation of HA trimers, as HA has lectin activity for SA22, 25. To perform experiments in the presence of SA, we used Y98F HA, wherein this mutation attenuates binding to SA25. We found that the amidase-cleaved N-glycans also reappeared on Y98F HA when the amidase was removed from solution (Figure 1C).

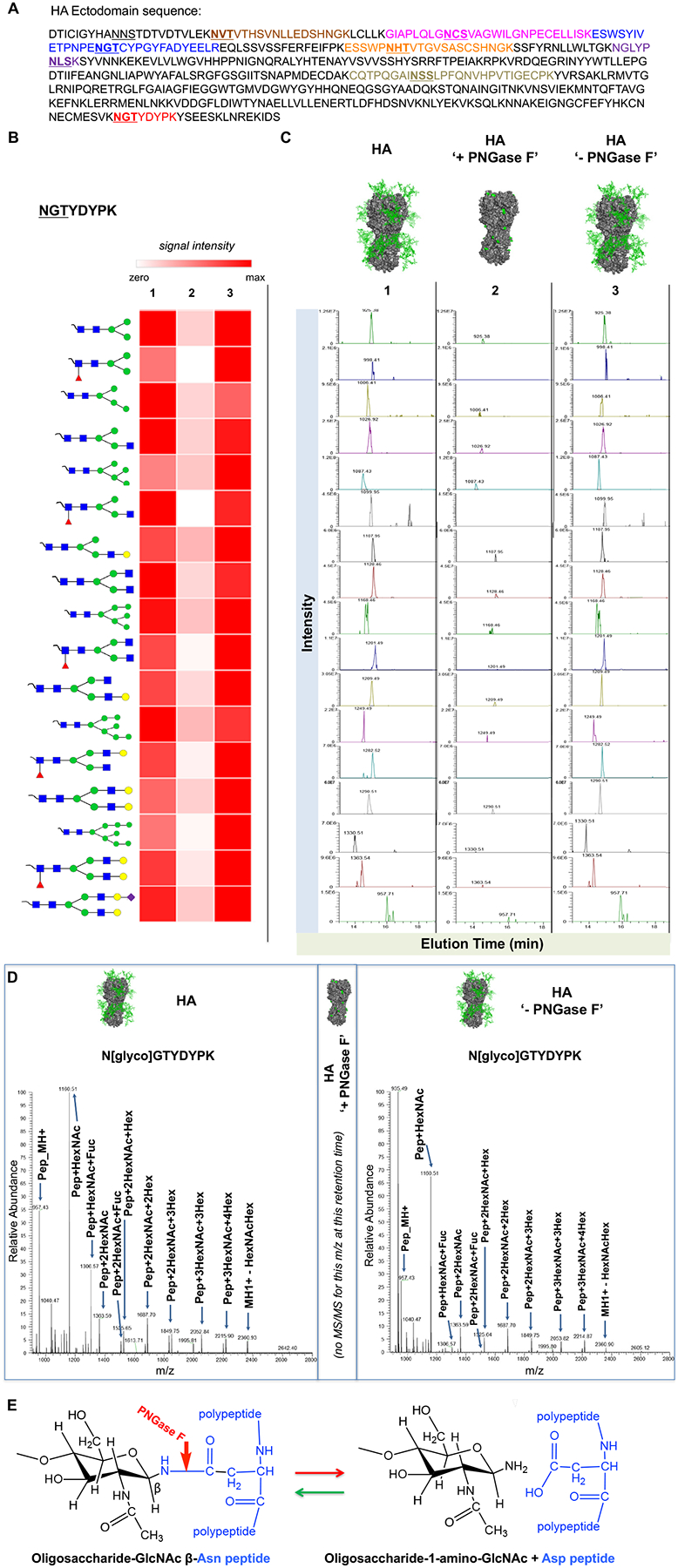

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) reveals cleavage and reattachment of N-linked glycans

To test whether covalent N-glycan reattachment occurred during non-denaturing sample handling post-PNGase F digestion and removal, we employed LC MS/MS to profile tryptic digests of HA protein at each stage of the reaction (pre-amidase exposure, post amidase exposure, and post-amidase removal; Figure 2, S2–S9, Table S1). As before, we ensured separation from CBD-PNGase F, using chitin affinity beads followed by SEC (Figure 1B). Over 90% of the amino acid sequence of HA was identified in the tryptic peptides, covering seven of the eight NXS/T sequons within HA (Figure S2). Prior to amidase treatment, N-linked glycan structures were detected at all seven of these sites (Figure 2B,C, Figures S3–S9). The eighth sequon is near the N-terminus of the protein and was not detected at either the peptide or glycopeptide level. Glycan structures varied from simple inner core structures (e.g. GlcNAc2Man3 +/−Fuc) to higher order sequences, including high mannose-type, hybrid-type and complex biantennary structures (Figure 2B,C, Figures S3–S9). We found that exposure to PNGase F under non-denaturing conditions efficiently removed the entire carbohydrate moiety at six of the seven measured NXS/T sites Asn residue was identified as Asp by LC-MS/MS. However, for the peptide, NGLYPNLSK, deamidated Asn (Asp) was not observed in the presence of PNGase F, suggesting that glycans were not efficiently cleaved from this peptide by the amidase (Figure S9). Based on this observation, we inferred the absence of glycans on this peptide. It was not until we performed an in-depth search against the 38 common N-linked glycan library that we confirmed that this peptide was indeed glycosylated, but not effectively de-N-glycosylated by PNGase F. However, glycans reappeared on the de-N-glycosylated peptides of the other six peptides bearing the NXS/T sequons, with compositions indistinguishable by MS (Figures 2B,C, S4–S9). These findings, along with the ability to repeatedly de-N-glycosylate the N-glycanated species using PNGase F, indicated that reattachment occurred at the same Asn residue. The HA was purified following co-expression with neuraminidase to prevent in-solution aggregation of the HA trimer22, 25, and as a result, only trace levels of terminal SA were detected.

Figure 2. N-glycans reattach to the same former glycosylation-site peptides of HA and have similar carbohydrate compositions.

(A) Amino acid sequence of HA, with potential N-linked glycosylation sites underlined. Bolded underlines indicate glycosites observed in glycopeptides and as deamidated peptides following digestion with PNGase F. In-gel trypsin digests of HA isolated at each stage of the glycanation reaction separated by SDS PAGE (before, post-de-N-glycosylation and post-PNGase F removal) were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. (B) Relative MS intensity heatmap of the 17 detected glycoforms of HA peptide NGTYDYPK identified [before (1), de-N-glycosylation in presence of PNGase F (2) and post-PNGase F removal (3)]. Relative intensities were adjusted for total amount of HA in the sample. (C) Extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) of the precursor masses for each of the corresponding glycan structures shown in A. The mass spectra corresponding to the data shown in panels B and C are shown in Figure S3 and results for the other six glycopeptides are presented in Figures S4–S9. (D) MS/MS Spectra of Glycopeptide N[glyco]GTYDYPK before PNGase F treatment (left), and after PNGase F and glycan reattachment. For both conditions, the site of attachment of the glycan ([HexNAc(4)Hex(5)Fuc(1)], mass of adduct = 1768.6, MW glycopeptide = 2725.1) was confirmed by the MS/MS spectra of the doubly charged precursor of the (M+2H)2+ of the glycopeptide = 1363.543. As indicated in the center of (D), no MS/MS was obtained for this m/z at or near this retention time during exposure to PNGase F. (E) Proposed reaction scheme for glycan reattachment by reverse hydrolysis.

HA forms a non-covalent complex with PNGase F liberated glycan, prior to N-glycanation

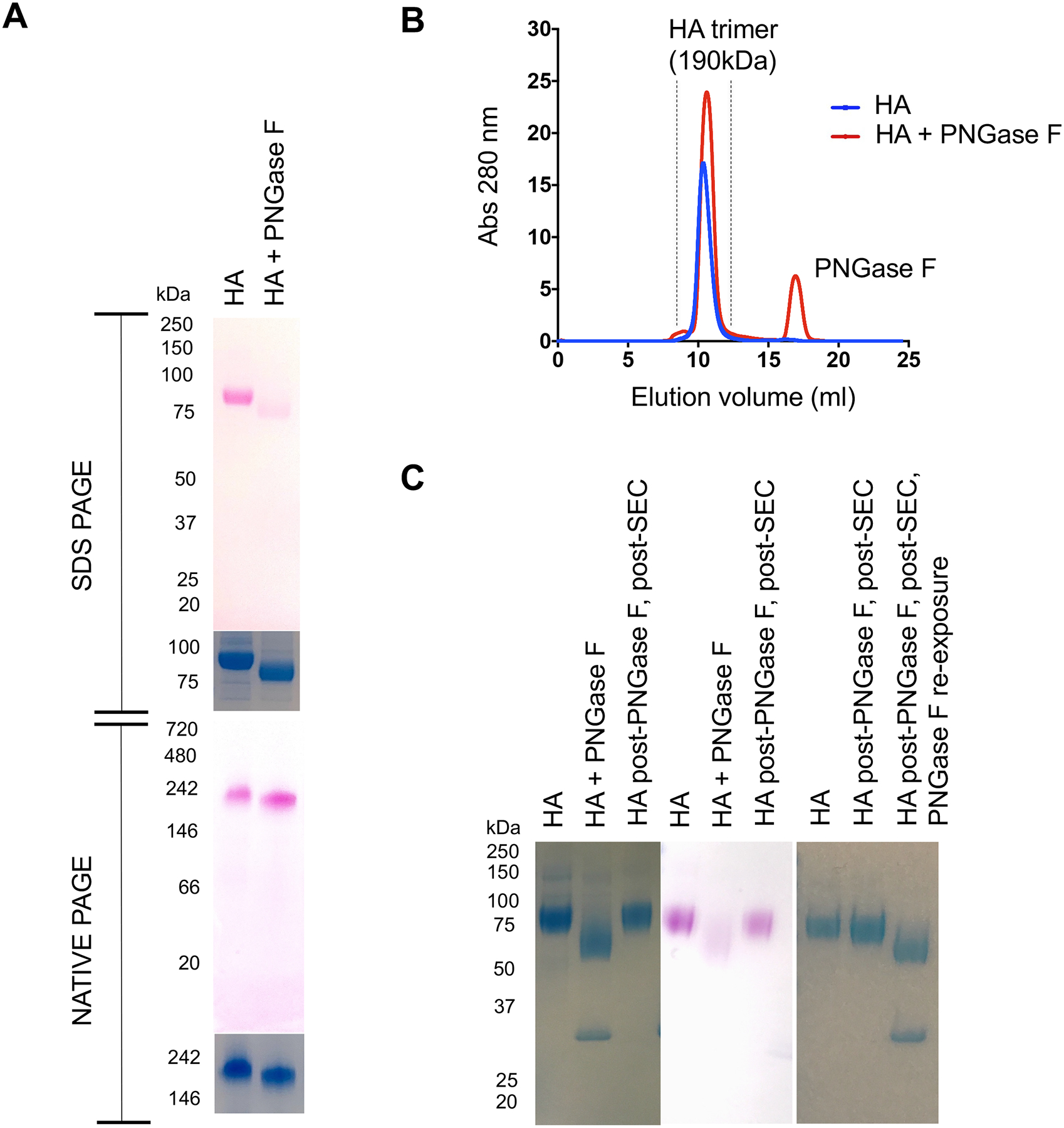

Our LC-MS/MS analyses indicated that glycans reattached to the same de-N-glycosylated peptides during N-glycanation, and the glycan structures observed after reattachment were indistinguishable by mass spectrometry from those observed prior to initial release (Figure 2B–D). We surmised this could not occur if amidase-liberated glycan diffused freely away from the de-N-glycosylated HA. To evaluate this, we treated HA with PNGase F and then performed side-by-side SDS versus native PAGE following de-N-glycosylation. As previously observed, HA underwent de-N-glycosylation, as marked by the marked decrease in PAS staining in the SDS PAGE readout, indicating loss of carbohydrate (Figure 3A). However, when the same preparation was separated by native PAGE, PAS staining was not diminished, although a small downward shift in apparent MW was observed. These data suggested that the loss of glycan signal was SDS-dependent and that the glycans cleaved from HA remained non-covalently associated with HA in presence of PNGase F.

Figure 3. N-glycanation is preceded by non-covalent retention of cleaved N-glycan.

(A) HA was de-N-glycosylated by PNGase F and the mixture was separated by SDS PAGE or native PAGE without prior removal of PNGase F. The gels were stained with PAS to mark glycan (pink) and also GelCode Blue for protein. (B) To further define non-covalent retention of N-glycan following cleavage by PNGase F, the HA+ PNGase F de-N-glycosylation reaction was immediately separated by SEC (Superdex 200 10/300 column; in this case no chitin beads affinity beads to pre-remove the amidase from solution). (C) HA product of this SEC was then analyzed for N-glycanation by SDS-PAGE (GelCode blue for protein, PAS to mark glycan and re-exposure to PNGase F to mark reformation of amidase substrate).

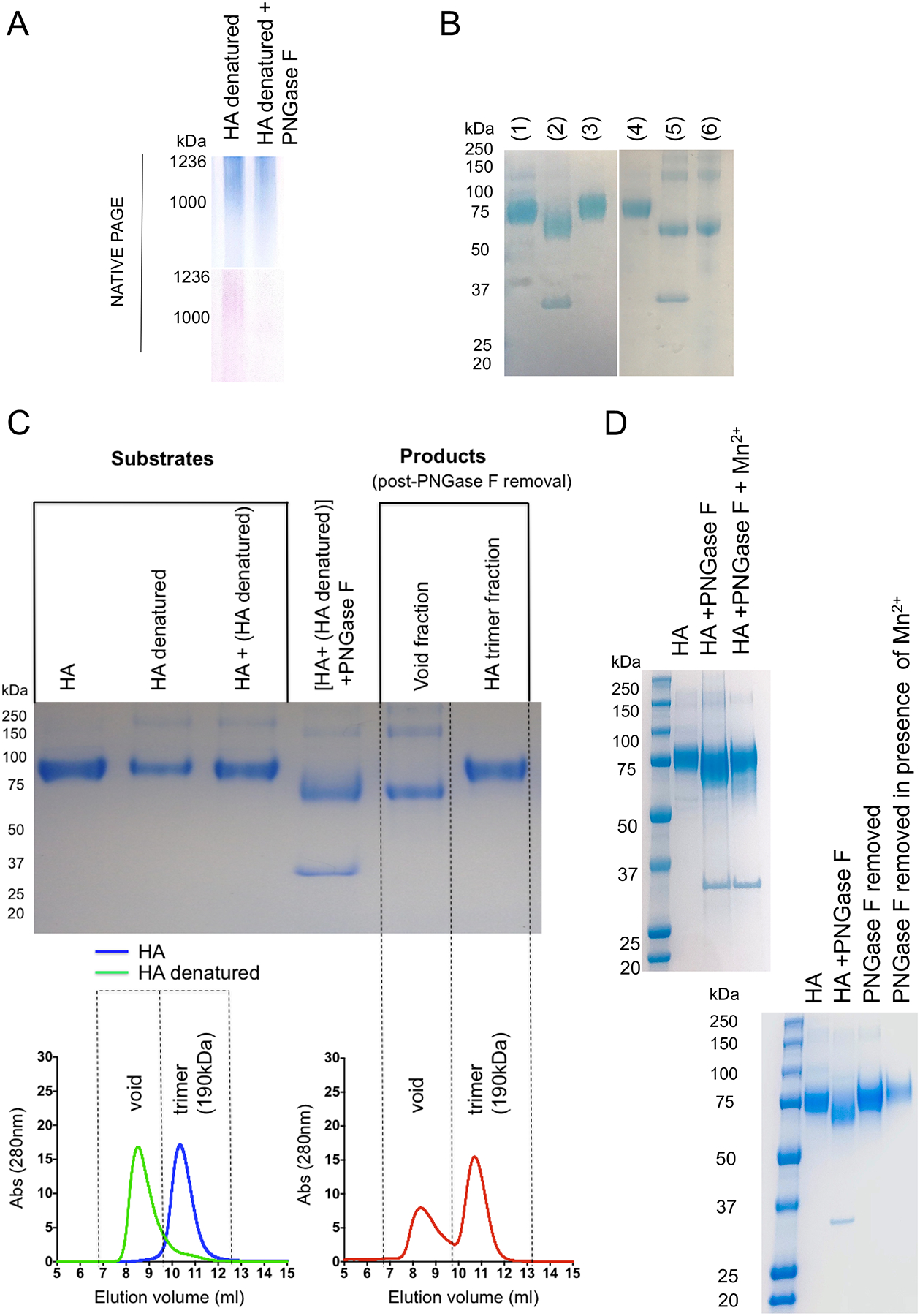

To further test for complex formation, we separated the HA-PNGase F reaction by SEC immediately, without the prior use of magnetic beads for in solution removal of the amidase. HA underwent concomitant N-glycanation during this chromatography: trimeric HA emerged, displaying a reacquired SDS-resistant glycan signal and reacquired sensitivity to PNGase F (Figure 3B,C). If HA was heat inactivated (100°C for 30 min) to provide amidase with denatured substrate, then N-glycan was no longer retained by HA, as indicated by PAS staining in the native PAGE readout (Figure 4A). Moreover, the denatured HA failed to undergo N-glycanation, as evaluated by de-N-glycosylation followed by separation of the HA-PNGase F reaction by SEC (Figure 4B). This suggested conformational control over the retention and reattachment of N-glycan at the deaminated NXS/T sequons. To further explore this, we mixed HA trimer with heat denatured HA then N-de-glycosylated the protein mixture together. The reaction components were then immediately separated by SEC, wherein the heat denatured versus trimeric forms of HA could also be resolved by the size exclusion column used (Figure 4C). We found that only the native HA underwent N-glycanation during the chromatography and the denatured HA remained de-N-glycosylated (Figure 4C). This occurred despite the steric accessibility of NXS/T sequons in both forms of HA (as evaluated by the starting sensitivity of both trimeric HA and heat inactivated HA to PNGase F; Figure 4B,C).

Figure 4. A non-enzymatic but conformational requirement for glycan retention and N-glycanation.

(A) If HA was denatured (100°C for 30 min), it no longer retained glycan in the presence of PNGase F, as marked by native PAGE followed by GelCode Blue stain for protein (blue) and PAS stain for glycan (pink). (B) Heat denatured HA also no longer served as substrate for N-glycanation, as evaluated by de-N-glycosylation by PNGase F followed by SEC and SDS PAGE and GelCode Blue staining. Lanes 1–3 are for a control N-glycanation reaction (1= HA; 2= HA + PNGase F; 3 = HA recovered post PNGase F treatment and post separation by SEC). Lanes 4–6 denote the same reaction except with heat denatured HA as substrate (4= HA; 5 = HA + PNGase F; 6 = HA recovered post PNGase F treatment and post separation by SEC). (C) Denatured HA was mixed with folded trimeric HA and the mixture was de-N-glycosylated by PNGase F and the capacity for N-glycanation was evaluated by SDS PAGE (GelCode Blue stain) before and after separation by SEC (Superdex 200 10/300 column). Both HA and denatured HA could be separated by SEC. Both HA forms also underwent de-N-glycosylation together (shift in MW in the SDS PAGE readout), but only denatured HA fraction remained de-N-glycosylated after chromatographic separation from the amidase. HA recovered from the trimeric elution volume on SEC had now required the glycan. (D) Upper gel: we confirm Mn2+ as an inhibitor of deglycosylation activity by PNGase F. The deglycosylation reaction was performed at 37°C for 24 h in the presence/absence of Mn2+ (all in absence of metal ion chelators) and visualized by SDS PAGE with GelCode Blue stain). Lower gel: N-glycanation in the presence of Mn2+. HA was deglycosylated by PNGase F in the absence of metal ion chelators (50nM Tris, pH 8.0) and then adjusted (treated) or not adjusted (control) to 1 mM MnCl2. The control and treated reactions were then separated by SEC where the column and FPLC system was pre-equilibrated in 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0 ± MnCl2. In both cases a single peak corresponding to the HA trimer was collected and then visualized by SDS PAGE with GelCode Blue stain.

N-glycanation in the presence of Mn2+

To control for enzymatic/PNGase F contribution to N-glycanation, we also performed the reaction in the presence of 1 mM Mn2+, which has been reported to inhibit the catalytic activity of this amidase29. We both confirmed Mn2+ as an inhibitor of PNGase F activity and also found that N-glycanation was not inhibited by 1 mM Mn2+ (Figure 4D).

N-glycanation by other viral glycoproteins / vaccine antigens

We found that N-glycanation also occurred for H3 and H5 trimers, which bear highly divergent amino acid sequences, but not structures32 (Figure S10). N-glycanation was also observed for the unrelated HIV Env, but not for fetal bovine fetuin, a well-described glycoprotein substrate ‘standard’ for PNGase F12 (Figure S10). To confirm this difference, we performed the deglycosylation/N-glycanation procedure on a mixture of fetuin and HA. We found that within this mixture, only the latter underwent N-glycanation following removal of PNGase F (Figure S10), suggesting that fetuin may lack the protein conformational features needed to support this reaction.

Discussion

Protein N-glycans, including those of HA, have traditionally been analyzed following de-N-glycosylation by N-glycanases under denaturing conditions11–14, 31. However, we found that following de-N-glycosylation under non-denaturing conditions, influenza HA spontaneously reversed this action and reformed the N-linkage when the N-glycanase was removed from solution. Reattachment to the Asp at de-N-glycosylated NXS/T positions was inferred by the repeated susceptibility to de-N-glycosylation by PNGase F (and the known consensus site required by deglycosidases) and our LC-MS/MS analysis demonstrated that glycans reattached to the same sequon-bearing peptide fragments of HA. Importantly this was a non-enzymatic activity as N-glycanation also occurred in the presence of metal ions that inhibit catalysis by PNGase F29. Rather, glycan reattachment was preceded by non-covalent association of the cleaved glycans, and both steps required folded protein substrate to proceed. Protein folding has long been predicted to support N-glycosylation within cells3, 8, 10, 33, 34. This new reaction, we term N-glycanation, suggests that under certain experimental conditions, some glycoproteins are capable of self-organizing the addition of their own glycans.

Spontaneous glycation of protein can proceed through the Maillard reaction in which a reducing sugar can react with the primary amino group provided by Lys35, 36. However, this process normally happens slowly, requiring high temperature to accelerate. By contrast, we observed rapid reformation of PNGase F substrate at room temperature, where the magnetic bead separation was performed in less than two hours, and for N-glycanation using SEC only, the separation between PNGase F and HA occurred within the first 20 minutes of the chromatography. Moreover, de-N-glycosylation followed by reformation of amidase substrate could be cycled repeatedly through iterative rounds of amidase exposure and removal, suggesting a two-state system in which N-linked glycan linkages were broken and then reformed. Normally, PNGase F catalyzes the hydrolysis of the amide bond of β-aspartylglycosylamine, liberating glycosylamine11–14. This reaction can also undergo reverse hydrolysis, a well-established principle where glycoside reactions are reversed so that the glycosidases, including N-glycanases, now catalyze synthesis (Asp back to Asn-glycan)37–39. However, we observed reformation of GlcNAc-β-Asn linkages from the deaminated positions when the N-glycanase was removed from solution, suggesting a different, glycosidase-independent, mechanism driving glycan reattachment.

Importantly, we found that N-glycanation was preceded by and also required the non-covalent retention of amidase-liberated glycans. This retention occurred in the presence of PNGase F and was disrupted by the addition of SDS. Free diffusing N-glycan would be unlikely to support a spontaneous reattachment process and consequently, we hypothesized that intramolecular complexing near or at the de-N-glycosylated sequon could greatly lower the activation barrier to reattachment, potentially through reverse hydrolysis. We further hypothesized that if this non-covalent assembly was meaningful for N-glycanation, then the amidase-cleaved glycan should not separate from de-N-glycosylated HA if the PNGase F + HA mixture were immediately separated by SEC (i.e. no pre-in solution depletion of PNGase F using magnetic beads). In support of these hypotheses, we found that cleaved N-glycan could not be separated from HA after exposure to PNGase F – rather N-glycanation occurred during the chromatographic separation from PNGase F. These data suggested that non-covalent association between de-N-glycosylated HA and released glycans was a precursor step for N-glycanation, which is likely a simple chemical process. The fact that denatured HA was unable to both retain glycan in the presence of PNGase F and then undergo N-glycanation, supports this conclusion and suggests that there was conformational control over glycan retention, aided by specific surface features that bind/trap carbohydrate. The observed differential capacity of glycoproteins to perform N-glycanation (HA vs HIV Env vs fetuin) may reflect differences in this conformational requirement.

While the chemical details of N-glycanation remain undefined, this reaction identifies a remarkable macromolecular-self organizing capability wherein a complex glycan array, normally generated by multiplexed activity of cellular biosynthetic enzymes, can be deconstructed and then reconstructed in simple test tube reactions, in the absence of cellular energy. This self-organizing activity also suggests potential utility in re-engineering some protein glycan sequences in vitro, a long-sought goal for glycoprotein therapies40, 41, including influenza and HIV vaccine development, where differential glycosylation of HA (the principle antigen for the seasonal flu vaccine) and also HIV Env can markedly affect bioactivity vaccine efficacy17–21.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Glycopeptide analysis workflow

Figure S2. Spectral coverage of HA

Figure S3. MS glycoforms of Asn497 during N-glycanation

Figure S10. N-glycanation by other viral glycoproteins/vaccine antigens.

Figure S4. MS intensity heat map for glycopeptide CQTPQGAINSSLPFQNVHPVTIGECPK during N-glycanation.

Figure S5. MS intensity heat map for glycopeptide NVTVTHSVNLLEDSHNGK during N-glycanation.

Figure S6. MS intensity heat map for glycopeptide GIAPLQLGNCSVAGWILGNPECELLISK during N-glycanation.

Figure S7. MS intensity heat map for glycopeptide ESSWPNHTVTGVSASCSHNGK during N-glycanation.

Figure S8. MS heat map for glycopeptide ESWSYIVETPNPENGTCYPGYFADYEELR during N-glycanation.

Figure S9. MS intensity heat map for glycopeptide NGLYPNLSK during N-glycanation.

Table S1. List of common N-glycans

Acknowledgments

D.L. was supported by NIH grants (2P30AI060354-11, R01AI137057-01, DP2DA042422, R01AI124378), the Harvard University Milton Award, The Gilead Research Scholars Program and Strategic Initiatives from the Ragon Institute. This work was also made possible by an ENDHIV Catalytic Grant to DL and SAC. IS was supported by a Molecular Biophysics Training grant (T32 GM008320). The authors thank Dr. C.A. Lingwood (Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto) for helpful advice on these findings.

Footnotes

Deposition of Mass Spectrometry Data

The original mass spectra, Byonic results, and the sequence database used for searches may be downloaded from MassIVE (http://massive.ucsd.edu).

The dataset is directly accessible via ftp://massive.ucsd.edu/MSV000084019

References

- [1].Schwarz F, and Aebi M (2011) Mechanisms and principles of N-linked protein glycosylation. Curr Opin Struc Biol 21, 576–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Moremen KW, Tiemeyer M, and Nairn AV (2012) Vertebrate protein glycosylation: diversity, synthesis and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13, 448–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mitra N, Sinha S, Ramya TN, and Surolia A (2006) N-linked oligosaccharides as outfitters for glycoprotein folding. form and function. Trends Biochem Sci 31, 156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Aebi M (2013) N-linked protein glycosylation in the ER, Biochim Biophys Acta 1833, 2430–2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lu H, Fermaintt CS, Cherepanova NA, Gilmore R, Yan N, and Lehrman MA (2018) Mammalian STT3A/B oligosaccharyltransferases segregate N-glycosylation at the translocon from lipid-linked oligosaccharide hydrolysis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 115, 9557–9562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chang MM, Imperiali B, Eichler J, and Guan Z (2015) N-Linked Glycans Are Assembled on Highly Reduced Dolichol Phosphate Carriers in the Hyperthermophilic Archaea Pyrococcus furiosus. PloS one 10, e0130482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Taguchi Y, Fujinami D, and Kohda D (2016) Comparative Analysis of Archaeal Lipid-linked Oligosaccharides That Serve as Oligosaccharide Donors for Asn Glycosylation. J Biol Chem 291, 11042–11054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shental-Bechor D, and Levy Y (2009) Folding of glycoproteins: toward understanding the biophysics of the glycosylation code. Curr Opin Struc Biol 19, 524–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lu D, Yang C, and Liu Z (2012) How hydrophobicity and the glycosylation site of glycans affect protein folding and stability: a molecular dynamics simulation. J Phys Chem B 116, 390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Shental-Bechor D, and Levy Y (2008) Effect of glycosylation on protein folding: a close look at thermodynamic stabilization. Proc Nat Acad Sci 105, 8256–8261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lazar IM, Deng J, Ikenishi F, and Lazar AC (2015) Exploring the glycoproteomics landscape with advanced MS technologies. Electrophoresis 36, 225–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Morelle W, Faid V, Chirat F, and Michalski JC (2009) Analysis of N- and O-linked glycans from glycoproteins using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Methods Mol Biol 534, 5–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].de Vries RP, de Vries E, Bosch BJ, de Groot RJ, Rottier PJ, and de Haan CA (2010) The influenza A virus hemagglutinin glycosylation state affects receptor-binding specificity. Virology 403, 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cao L, Diedrich JK, Kulp DW, Pauthner M, He L, Park SR, Sok D, Su CY, Delahunty CM, Menis S, Andrabi R, Guenaga J, Georgeson E, Kubitz M, Adachi Y, Burton DR, Schief WR, Yates Iii JR, and Paulson JC (2017) Global site-specific N-glycosylation analysis of HIV envelope glycoprotein. Nat Commun 8, 14954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kwon YD, Finzi A, Wu X, Dogo-Isonagie C, Lee LK, Moore LR, Schmidt SD, Stuckey J, Yang Y, Zhou T, Zhu J, Vicic DA, Debnath AK, Shapiro L, Bewley CA, Mascola JR, Sodroski JG, and Kwong PD (2012) Unliganded HIV-1 gp120 core structures assume the CD4-bound conformation with regulation by quaternary interactions and variable loops. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 109, 5663–5668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhou T, Lynch RM, Chen L, Acharya P, Wu X, Doria-Rose NA, Joyce MG, Lingwood D, Soto C, Bailer RT, Ernandes MJ, Kong R, Longo NS, Louder MK, McKee K, O’Dell S, Schmidt SD, Tran L, Yang Z, Druz A, Luongo TS, Moquin S, Srivatsan S, Yang Y, Zhang B, Zheng A, Pancera M, Kirys T, Georgiev IS, Gindin T, Peng HP, Yang AS, Program NCS, Mullikin JC, Gray MD, Stamatatos L, Burton DR, Koff WC, Cohen MS, Haynes BF, Casazza JP, Connors M, Corti D, Lanzavecchia A, Sattentau QJ, Weiss RA, West AP Jr., Bjorkman PJ, Scheid JF, Nussenzweig MC, Shapiro L, Mascola JR, and Kwong PD (2015) Structural Repertoire of HIV-1-Neutralizing Antibodies Targeting the CD4 Supersite in 14 Donors. Cell 161, 1280–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hutter J, Rodig JV, Hoper D, Seeberger PH, Reichl U, Rapp E, and Lepenies B (2013) Toward animal cell culture-based influenza vaccine design: viral hemagglutinin N-glycosylation markedly impacts immunogenicity. J Immunol 190, 220–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].de Vries RP, Smit CH, de Bruin E, Rigter A, de Vries E, Cornelissen LA, Eggink D, Chung NP, Moore JP, Sanders RW, Hokke CH, Koopmans M, Rottier PJ, and de Haan CA (2012) Glycan-dependent immunogenicity of recombinant soluble trimeric hemagglutinin. J Virol 86, 11735–11744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhou Q, and Qiu H (2019) The Mechanistic Impact of N-Glycosylation on Stability, Pharmacokinetics, and Immunogenicity of Therapeutic Proteins. J Pharm Sci 108, 1366–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bajic G, Maron MJ, Adachi Y, Onodera T, McCarthy KR, McGee CE, Sempowski GD, Takahashi Y, Kelsoe G, Kuraoka M, and Schmidt AG (2019) Influenza Antigen Engineering Focuses Immune Responses to a Subdominant but Broadly Protective Viral Epitope. Cell Host Microbe 25, 827–835 e826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Eggink D, Goff PH, and Palese P Guiding the immune response against influenza virus hemagglutinin toward the conserved stalk domain by hyperglycosylation of the globular head domain. J Virol 88, 699–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Weaver GC, Villar RF, Kanekiyo M, Nabel GJ, Mascola JR, and Lingwood D (2016) In vitro reconstitution of B cell receptor-antigen interactions to evaluate potential vaccine candidates. Nat Protoc 11, 193–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Whittle JR, Wheatley AK, Wu L, Lingwood D, Kanekiyo M, Ma SS, Narpala SR, Yassine HM, Frank GM, Yewdell JW, Ledgerwood JE, Wei CJ, McDermott AB, Graham BS, Koup RA, and Nabel GJ (2014) Flow cytometry reveals that H5N1 vaccination elicits cross-reactive stem-directed antibodies from multiple Ig heavy-chain lineages. J Virol 88, 4047–4057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sangesland M, Kazer SW, Ronsard L, Bals J, Boyoglu-Barnum S, Yousif AS, Barnes R, Feldman J, Quirindongo-Crespo M, McTamney PM, Rohrer D, Lonberg N, Chackerian B, Graham BS, Kanekiyo M, Shalek AK, Lingwood D (2019) Germline-encoded affinity for cognate antigen enables vaccine amplification of a human broadly neutralizing response against influenza virus., Immunity 51, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Villar RF, Patel J, Weaver GC, Kanekiyo M, Wheatley AK, Yassine HM, Costello CE, Chandler KB, McTamney PM, Nabel GJ, McDermott AB, Mascola JR, Carr SA, and Lingwood D (2016) Reconstituted B cell receptor signaling reveals carbohydrate-dependent mode of activation. Sci Rep 6, 36298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Deng X, Zhang J, Liu Y, Chen L, and Yu C (2017) TNF-alpha regulates the proteolytic degradation of ST6Gal-1 and endothelial cell-cell junctions through upregulating expression of BACE1. Sci Rep 7, 40256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jones MB, Oswald DM, Joshi S, Whiteheart SW, Orlando R, and Cobb BA (2016) B-cell-independent sialylation of IgG. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 113, 7207–7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wittig I, Braun HP, and Schagger H (2006) Blue native PAGE. Nat Protoc 1, 418–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mussar KJ, Murray GJ, Martin BM, and Viswanatha T (1989) Peptide: N-glycosidase F: studies on the glycoprotein aminoglycan amidase from Flavobacterium meningosepticum. J Biochem Biophys Methods 20, 53–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhang S, Sherwood RW, Yang Y, Fish T, Chen W, McCardle JA, Jones RM, Yusibov V, May ER, Rose JK, and Thannhauser TW (2012) Comparative characterization of the glycosylation profiles of an influenza hemagglutinin produced in plant and insect hosts. Proteomics 12, 1269–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lazar IM, Lee W, and Lazar AC (2013) Glycoproteomics on the rise: established methods, advanced techniques, sophisticated biological applications. Electrophoresis 34, 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Paules C, and Subbarao K (2017) Influenza. Lancet 390, 697–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Xu C, and Ng DT (2015) Glycosylation-directed quality control of protein folding. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16, 742–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Helenius A, and Aebi M (2004) Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Ann Rev Biochem 73, 1019–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhang Q, Ames JM, Smith RD, Baynes JW, and Metz TO (2009) A perspective on the Maillard reaction and the analysis of protein glycation by mass spectrometry: probing the pathogenesis of chronic disease. J Proteome Res 8, 754–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Rabbani N, Ashour A, and Thornalley PJ (2016) Mass spectrometric determination of early and advanced glycation in biology. Glycoconj J 33, 553–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zeuner B, Jers C, Mikkelsen JD, and Meyer AS (2014) Methods for improving enzymatic trans-glycosylation for synthesis of human milk oligosaccharide biomimetics. J Agric Food Chem 62, 9615–9631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lee JY, Park TH (2002) Enzymatic in vitro glycosylation using peptide-N-glycosidase F. Enz. Microb. Tech 30, 716–720. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Park SJ, Lee JY, and Park TH (2003) In Vitro Glycosylation of Peptide (RKDVY) and RNase A by PNGase F. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol 13, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Gupta SK, and Shukla P (2018) Glycosylation control technologies for recombinant therapeutic proteins. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102, 10457–10468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lalonde ME, and Durocher Y (2017) Therapeutic glycoprotein production in mammalian cells. J Biotechnol 251, 128–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Glycopeptide analysis workflow

Figure S2. Spectral coverage of HA

Figure S3. MS glycoforms of Asn497 during N-glycanation

Figure S10. N-glycanation by other viral glycoproteins/vaccine antigens.

Figure S4. MS intensity heat map for glycopeptide CQTPQGAINSSLPFQNVHPVTIGECPK during N-glycanation.

Figure S5. MS intensity heat map for glycopeptide NVTVTHSVNLLEDSHNGK during N-glycanation.

Figure S6. MS intensity heat map for glycopeptide GIAPLQLGNCSVAGWILGNPECELLISK during N-glycanation.

Figure S7. MS intensity heat map for glycopeptide ESSWPNHTVTGVSASCSHNGK during N-glycanation.

Figure S8. MS heat map for glycopeptide ESWSYIVETPNPENGTCYPGYFADYEELR during N-glycanation.

Figure S9. MS intensity heat map for glycopeptide NGLYPNLSK during N-glycanation.

Table S1. List of common N-glycans