It remains unclear whether severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) can be shed into breastmilk and transmitted to a child through breastfeeding. Recent investigations have found no evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in human breastmilk, but sample sizes were small.1, 2, 3 We examined milk from two nursing mothers infected with SARS-CoV-2. Both mothers were informed about the study and gave informed consent. Ethical approval for this case study was waived by the Ethics Committee of Ulm University and all samples were anonymised.

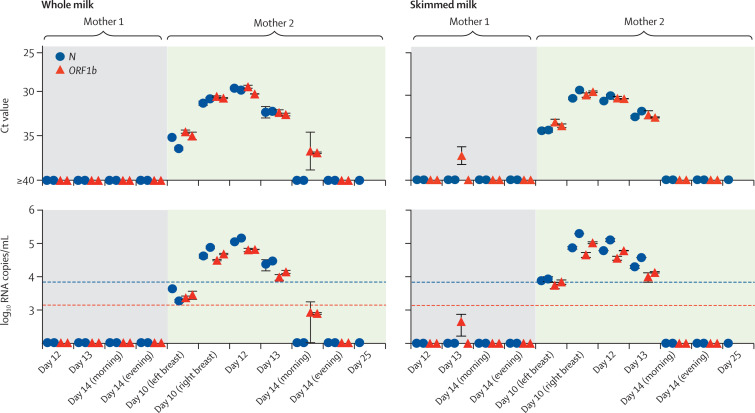

Clinical data and the timecourse of infection in the two mothers is shown in figure 1 . After feeding and nipple disinfection, milk was collected with pumps and stored in sterile containers at 4°C or −20°C until further analysis. We determined viral loads using RT-qPCR for SARS-CoV-2 N and ORF1b-nsp14 genes4 in both whole and skimmed milk (obtained after removal of the lipid fraction). Further details of sample storage and processing are provided in the appendix. Following admission and delivery (day 0), four samples from Mother 1 tested negative (figure 2 ). By contrast, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in milk from Mother 2 at days 10 (left and right breast), 12, and 13. Samples taken subsequently were negative (figure 2). Ct values for SARS-CoV-2 N peaked at 29·8 and 30·4 in whole milk and skimmed milk, respectively, corresponding to 1·32 × 105 copies per mL and 9·48 × 104 copies per mL (mean of both isolations). Since milk components might affect RNA isolation and quantification, viral RNA recovery rates in milk spiked with serial dilutions of a SARS-CoV-2 stock were determined. We observed up to 89·2% reduced recovery rate in whole milk and 51·5% in skimmed milk (appendix), suggesting that the actual viral loads in whole milk of Mother 2 could be even higher than detected.

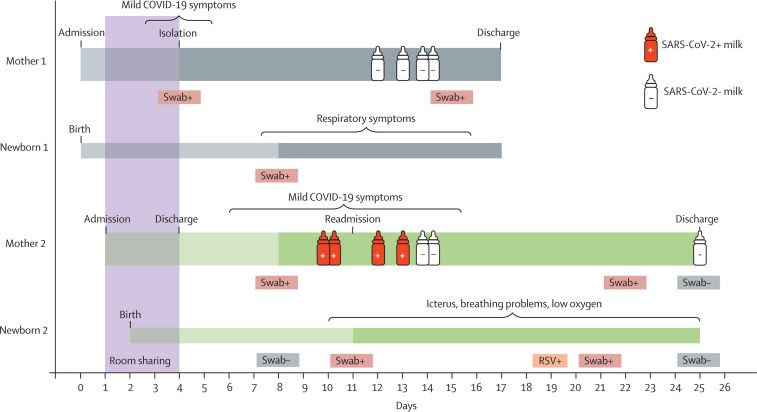

Figure 1.

Timecourse of SARS-CoV-2 infection of two mothers with newborn children

After delivery, Mother 1 developed mild COVID-19 symptoms and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Following spatial isolation of Mother 1 with her newborn (Newborn 1), Newborn 1 subsequently tested positive and developed respiratory problems, but both Mother 1 and Newborn 1 recovered. Mother 2 was admitted to the same hospital and room as Mother 1 and Newborn 1. Upon delivery, Mother 2 and Newborn 2 were brought back to the same room as Mother 1 and Newborn 1, and they stayed in the same room until Mother 1 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and isolated. Mother 2 and Newborn 2 were discharged on day 4. Mother 2 developed mild COVID-19 symptoms shortly thereafter and began wearing a surgical mask at all times of the day. Mother 2 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on day 8. 3 days later, Newborn 2 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and was readmitted to hospital because of newborn icterus and severe breathing problems. The child received phototherapy with blue light and ventilation therapy. Newborn 2 tested positive for RSV and SARS-CoV-2 at later timepoints. Mother 1 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 again on day 22, 13 days after first being diagnosed. RT-qPCR analysis of breastmilk samples from both mothers revealed SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the milk of Mother 2 on days 10–13 (red bottles), whereas samples from Mother 1 were negative (white bottles). Dark shading indicates time from first SARS-CoV-2 positive oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal swabs. Brackets indicate duration of COVID-19 symptoms. SARS-CoV-2=severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. RSV=respiratory syncytial virus.

Figure 2.

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in breastmilk from an infected mother

SARS-CoV-2 RNA was isolated from whole and skimmed breastmilk obtained at different timepoints and analysed by RT-qPCR, using primer sets targeting SARS-CoV-2 N and ORF1b genes. Samples and viral RNA standard were run in duplicates, and isolation and RT-qPCR were repeated in two independent assays. RNA in breastmilk from Mother 2 on day 25 was only isolated once and only analysed by RT-qPCR for SARS-CoV-2 N. Symbols at baseline indicate no amplification (or Ct>36·5 and no amplification in one replicate). Blue dashed line denotes quantification threshold for N (160 copies per reaction; Ct 34·2) and red dotted line for ORF1b (32 copies per reaction; Ct 35·9). Values below these lines but above baseline indicate amplification in both replicates, but no reliable quantification. Values shown represent mean (SD) from duplicates. SARS-CoV-2=severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Ct=cycle threshold.

We detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA in milk samples from Mother 2 for 4 consecutive days. Detection of viral RNA in milk from Mother 2 coincided with mild COVID-19 symptoms and a SARS-CoV-2 positive diagnostic test of the newborn (Newborn 2). Mother 2 had been wearing a surgical mask since the onset of symptoms and followed safety precautions when handling or feeding the neonate (including proper hand and breast disinfection, strict washing, and sterilisation of milk pumps and tubes). However, whether Newborn 2 was infected by breastfeeding or other modes of transmission remains unclear. Further studies of milk samples from lactating women and possible virus transmission via breastfeeding are needed to develop recommendations on whether mothers with COVID-19 should breastfeed.

This online publication has been corrected. The corrected version first appeared at thelancet.com on September 10, 2020

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests. RG, CC, and JAM contributed equally. This work was supported by the EU's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Fight-nCoV, 101003555 to JM) and the German Research Foundation (CRC 1279 to SS, FK, and JM; and MU 4485/1-1 to JAM)

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Lackey KA, Pace RM, Williams JE. SARS-CoV-2 and human milk: what is the evidence? medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.07.20056812. published online April 20. (preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang N, Che S, Zhang J. Breastfeeding of infants born to mothers with COVID-19: a rapid review. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.13.20064378. published April 19. (preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L, Li Q, Zheng D, Jiang H. Clinical characteristics of pregnant women with Covid-19 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009226. published April 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu DKW, Pan Y, Cheng SMS. Molecular diagnosis of a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) causing an outbreak of pneumonia. Clin Chem. 2020;66:549–555. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.