Abstract

Background:

Prospective population-based studies of psychiatric comorbidity following trauma and severe stress exposure in children are limited.

Aims:

To examine incident psychiatric comorbidity following stress disorder diagnoses in Danish school age children using Danish national health care system registries.

Methods:

Children (6–15 years) with a severe stress or adjustment disorder (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision) between 1995–2011 (n = 11,292) were followed prospectively for an average of 5.8 years. Incident depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorder diagnoses were examined relative to an age- and sex-matched comparison cohort (n = 56,460) using Cox proportional hazards regression models. Effect modification by sex was examined through stratified analyses.

Results:

All severe stress and adjustment disorder diagnoses were associated with increased rates for all incident outcome disorders relative to the comparison cohort. For instance, adjustment disorders were associated with higher rates of incident depressive (rate ratio 6.8; 95% CI: 6.0, 7.7), anxiety (rate ratio 5.3; 95% CI: 4.5, 6.4) , and behavior disorders (rate ratio 7.9; 95% CI: 6.6, 9.3). Similarly, PTSD was also associated with higher rates of depressive (rate ratio 7.4; 95% CI: 4.2, 13), anxiety (rate ratio 7.1; 95% CI: 3.5, 14) , and behavior disorder (rate ratio 4.9; 95% CI: 2.3, 11) diagnoses. There was no evidence of sex-related differences.

Conclusions:

Stress disorders varying in symptom constellation and severity are associated with a range of incident psychiatric disorders in children. Transdiagnostic assessments within a longitudinal framework are needed to characterize the course of post-trauma or severe stressor psychopathology.

INTRODUCTION

Trauma and severe stressors are highly prevalent among children (1, 2) and are frequently associated with multiple psychiatric conditions (2). However, the limited extant epidemiologic research on incident psychiatric comorbidity in children exposed to trauma or severe stressors is currently subject to three limitations. First, research examining psychiatric morbidity following the experience of a traumatic event has been dominated by a focus on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (1, 3). A substantial proportion of individuals who experience traumatic events do not develop PTSD but may develop other stress-related disorders (3). Within the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), five stress-related diagnoses, including PTSD, are used for identifying post-trauma or severe stressor sequelae based on the type and duration of symptoms. Studies with adults indicate that individuals who develop PTSD following trauma have increased risk for other mental disorders compared to those exposed to trauma who do not develop PTSD (4). Less is known about incident mental disorders in individuals who do not develop PTSD but instead develop other stress related diagnoses. Second, there is no population-based study examining a range of stress disorders and incident psychopathology in children. Limited available evidence from studies of children who have experienced trauma, suggests comparable levels of functional impairment across a range of symptom constellations (5-7). Also, consistent with findings with adult samples, studies with children suggests that stress disorders are often comorbid with other psychiatric disorders, most commonly depression, anxiety, and behavior disorders, and substance use disorders in older adolescents (2). However, these findings are largely based on clinical treatment-seeking samples. Because psychiatric comorbidity is correlated with seeking treatment, clinical samples are not representative of the relations among trauma or severe stressor, stress disorders, and other psychiatric disorders in the general population (8). Third, available data from population-based studies with children and adolescents are also subject to biases due to their cross-sectional nature (e.g., reverse causation), utilization of a subset of a population (e.g., selection bias), and limitations in age range (focusing mostly on adolescents), and type of diagnoses examined (1, 2). Thus, longitudinal population-based data of children experiencing trauma or severe stressors and the course of incident psychiatric disorders can inform future intervention and prevention research. For instance, if stress disorders, including those requiring less severe or fewer symptoms (e.g., adjustment disorder) or a shorter duration of symptoms (e.g., acute stress disorder) for diagnosis increase the risk of incident disorders at rates comparable to more severe disorders (e.g., PTSD), then intervention or prevention research aimed at reducing the burden of incident comorbid psychiatric disorders would need to examine outcomes across a broad array of stress disorders. Accordingly, the aims of this study were to examine the association between all ICD-10 severe stress disorders and a range of incident depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorders in a population-based prospective longitudinal sample of children and adolescents. Additionally, given the well-established sex-related differences stress reactions in adults, particularly following trauma exposure (3), we examined effect modification of these associations by sex.

METHODS

Participants

Of the 1,698,654 Danish-born residents of Denmark, between the ages of 6 and 15 years in the period between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 2011, this study included all children diagnosed with a severe stress disorder in either the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register (DPCRR) or the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) (9). Given the developmentally distinct manifestations of traumatic stress reactions for very young children (infants – age 5 years) (7), we focus on school-aged (6–15 years) children and adolescents. We included children and adolescents through 15 years of age, as this marks the end of compulsory primary education in Denmark. Findings related to older adolescents and adults have been previously published (4). Stress cohort members had to receive at least one incident stress disorder diagnosis during the study period. The year 1995 was chosen as the start of the study period because ICD-10 coding was implemented in 1994 and the inclusion of outpatient clinic visits in the psychiatric registry in Denmark was implemented in 1995. We excluded anyone with a diagnosis between January 1, 1994 and December 31, 1994 from the study because persons who were diagnosed in 1994 may have been living with the disorder before receiving the diagnosis that year (i.e., prevalent cases). Prevalent cases may differ from incident cases with respect to disorder etiology, clinical course, and survival (10). For instance, prevalent cases are affected by factors associated with disorder maintenance and survival. Thus, prevalent cases were removed from the cohort and the current analyses to ensure that only newly occurring cases of stress disorders were examined. In total, 11,292 children received a first severe stress or adjustment disorder diagnosis between 1995 and 2011. A general population comparison cohort of children was created by individually matching children who had not received a stress disorder diagnosis at the time that their matched stress cohort member was diagnosed (n = 56,460). Members of the comparison cohort were individually matched to stress cohort members by sex and age at the matched index date at a ratio of 5 to 1 (11, 12). Of note, this cohort was designed such that if a member of the comparison cohort were diagnosed with a stress disorder after their match index date they were removed from the comparison cohort and designated to the appropriate stress disorder group with five new non-stress disorder diagnosed comparison group members then selected to match that participant. Diagnostic validation processes have been the subject of prior studies and suggest that diagnoses (e.g., affective disorders, stress disorders) in the registries have high validity compared to computer-generated diagnoses or independent reassessment (13).

Predictor and outcome variables

We obtained data from national Danish medical longitudinal registers. The 10-digit Civil Registration number, a unique identifier assigned to all residents of Denmark, was used to retrieve and merge data for each individual for the creation of the cohort.

Predictors.

The predictors in our analyses were five ICD-10 stress diagnoses: (i) Acute stress reaction (diagnosed in the immediate aftermath of an event; ICD-10 code F43.0), (ii) PTSD (diagnosed following a traumatic event and a specified period of symptom maintenance; ICD-10 code F43.1), (iii) Adjustment disorder (diagnosed following a stressful event and specified period of non-recovery; ICD-10 code F43.2), and two additional diagnoses (iv) Other reactions to severe stress (ICD-10 code F43.8), and (v) Reactions to severe stress unspecified (ICD-10 code F43.9) are used for those who are experiencing symptoms following a traumatic or severe stressor but they do not meet the full diagnostic criteria for one of the aforementioned disorders. We obtained diagnostic data from the DPCRR, which records data on patients who were admitted to a psychiatric inpatient hospital, received outpatient clinic psychiatric care, or received treatment at a psychiatric emergency department. Diagnostic data were also obtained from the DNPR, which contains patient data from outpatient clinics, somatic hospitals, and emergency rooms. Registries include data since 1995 including treatment dates and up to 20 diagnoses per treatment entry for patients. Our prior validation study of the stress diagnoses in registries showed good validity for acute stress reaction, other reactions to severe stress, and unspecified reactions to severe stress and showed high validity for PTSD and adjustment disorder (13).

Outcomes.

The primary outcomes in the present study were incident diagnoses of depressive disorders (ICD-10 codes F32, F33, and F34.1, which include major depression and dysthymia), anxiety disorders (ICD-10 codes F40 and F41, which include phobic anxiety and generalized anxiety disorders), and behavior disorders including Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ICD-10 code F90), conduct disorders (ICD-10 code F91), and disorders of social functioning with onset specific to childhood and adolescence (ICD-10 code F94). Our study outcomes were similar to those examined in the literature and a recent longitudinal study (14) examining the impact of early life stressors on later psychopathology. However, substance use related disorders were not included due to the low incidence rates in our sample in this developmental period.

Analyses

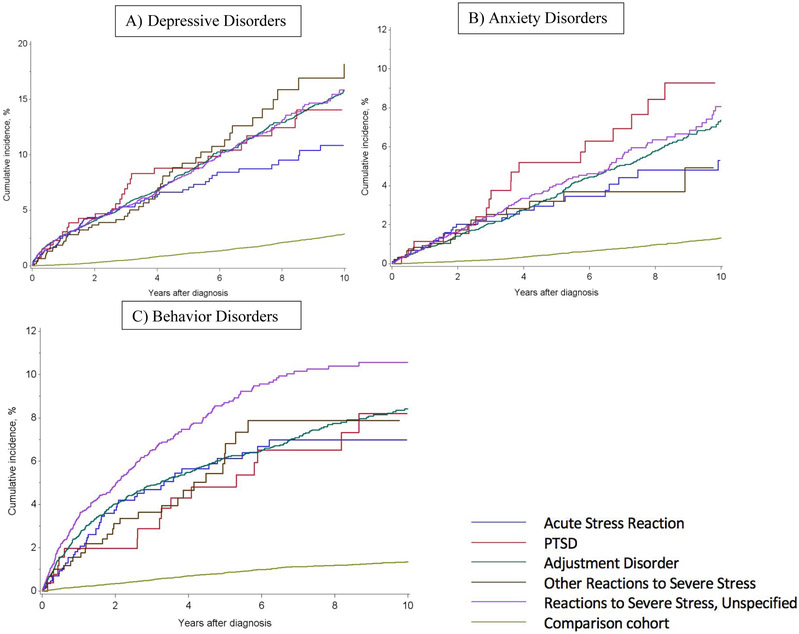

We conducted descriptive and stratified analyses to examine demographic characteristics and psychiatric disorders across categories of stress diagnoses at baseline (i.e. at the time of the initial stress diagnosis). We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to examine associations of severe stress or adjustment diagnoses with each outcome (i.e. depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorders). For each analysis of incident disorders only children free of the outcome diagnoses at baseline (e.g., depressive disorders) were included in the analyses, and the model controlled for other disorders at baseline (i.e. anxiety and behavior disorder diagnoses). Cumulative incidence curves were plotted to examine the occurrence of new-onset depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorders following the initial stress diagnosis (or the index date among the comparison cohort). Incidence curves were plotted for a 10-year period following an initial stress diagnosis due to some small cell sizes in the subsequent follow up period. We also examined the number of incident diagnoses following stress disorder diagnoses, and time to incident psychiatric disorder diagnoses. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Boston University, the Danish Health and Medicines Authority, and Danish Data Protection Agency (record no. 2012-41-0841).

RESULTS

Table 1 displays descriptive data and rates of psychiatric disorders at the time of the initial diagnosis for the stress cohort and the comparison cohort. Sixty three percent of the stress diagnosis cohort members were girls and 73% of the children were between the ages of 12–15 years. The proportions of children with comorbid baseline psychopathology differed across the stress disorder groups. Depressive disorders were most prevalent among children diagnosed with an adjustment disorder (5.2%). Depressive (4.2%) and behavior disorders (7.4%) were most common among children with PTSD. Additionally, 14% of children diagnosed with PTSD, 13% diagnosed with Adjustment disorder, and 10% diagnosed with Reaction to severe stress unspecified had one or more psychiatric diagnoses at baseline, other than their stress-related diagnoses. Cumulative incidence curves (Figure 1) show that children in the stress cohort had a higher incidence of depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorders following their severe stress or adjustment diagnoses than did members of the comparison cohort following their matched index date over the course of the study. On average children in the stress cohort were followed for 5.8 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Stress Disorders and Comparison Cohorts of Children (6-15 years) in Denmark, 1995–2011.

| Stress Cohort (N = 11,292) |

ASR (N = 931) |

PTSD (N = 285) |

Adjustment Disorder (N = 6,183) |

ORSS (N = 656) |

RSSU (N = 3,237) |

Comparison Cohort (N = 56,460) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex % (N) | |||||||

| Female | 63 | 69 | 60 | 62 | 61 | 65 | 63 |

| Male | 37 | 31 | 40 | 38 | 39 | 35 | 37 |

| Age group % (N) | |||||||

| 6–11 years | 27 | 23 | 31 | 26 | 37 | 29 | 27 |

| 12–15 years | 73 | 77 | 69 | 74 | 63 | 71 | 73 |

| Baseline psychiatric diagnoses (%) | |||||||

| Depressive disorder diagnoses | 4.3 | 2.7 | 4.2 | 5.2 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 0.1 |

| Anxiety disorder diagnoses | 1.5 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 0.1 |

| Behavior disorder diagnoses | 6.1 | 4.7 | 7.4 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 0.9 |

| 1+ psychiatric disorders | 11 | 8.3 | 14 | 13 | 8.5 | 10 | 1.1 |

| Follow-up time (person-time years) | |||||||

| 0 to < 1 | 12 | 14 | 8.8 | 11 | 20 | 11 | 12 |

| 1 to < 5 | 41 | 43 | 25 | 39 | 47 | 46 | 41 |

| 5 to <10 | 27 | 22 | 38 | 27 | 22 | 30 | 27 |

| 10+ | 19 | 21 | 28 | 23 | 11 | 13 | 19 |

| Average duration of follow-up (person-time in years) | 5.8 | 5.7 | 7.5 | 6.2 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 5.8 |

Notes: ASR = Acute Stress Reaction. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. ORSS = Other reactions to severe stress. RSSU = Reactions to severe stress unspecified.

Figure 1.

Cumulative Incidence Curves for Psychiatric Diagnoses following Stress Diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision), Denmark, 1995-2011. A) Depressive Disorders; B) Anxiety Disorders, and C) Behavior Disorders

Results from the Cox proportional hazards regression models (Table 2) indicate that each of the stress disorders is associated with higher rates of depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorders. For example, the rate of depressive disorders among children diagnosed with an adjustment disorder was 6.8 (95% CI: 6.0, 7.7) relative to the control comparison group. All other stress disorders also had strong associations with each type of incident psychiatric disorder. We examined proportions of incident psychiatric comorbidity (Supplemental Table 1). Across all stress disorders, a greater proportion of children were diagnosed with incident comorbid psychiatric disorders, with rates of two or more incident diagnoses ranging between 3.0% – 5.3%, with an average of 4.4% for the full stress cohort, compared to 0.5% in the comparison cohort. With respect to time to incident psychiatric comorbidity for each type of disorder (Supplemental Table 2), for the full stress cohort an incident depressive disorder was diagnosed 3.9 years after a baseline stress disorder, and incident anxiety and behavior disorders were diagnosed 4.5 and 2.5 years later, respectively. In the comparison cohort incident depressive disorders were diagnosed 5.9 years from baseline, and incident anxiety and behaviors disorders were diagnosed 6.3 years and 3.8 years later, respectively.

Table 2.

Associations between Baseline Stress Disorders and Incident Psychiatric Comorbidity in Children (6–15 years), Denmark, 1995–2011.

| Depressive Disorders | Anxiety Disorders | Behavior Disorders | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) | |

| Stress cohort | |||

| Acute stress reaction | 5.7 (4.0, 8.1) | 8.3 (4.6, 15) | 6.0 (3.9, 9.2) |

| PTSD | 7.4 (4.2, 13) | 7.1 (3.5, 14) | 4.9 (2.3, 11) |

| Adjustment disorder | 6.8 (6.0, 7.7) | 5.3 (4.5, 6.4) | 7.9 (6.6, 9.3) |

| Other reactions to severe stress | 11 (6.5, 18) | 6.9 (3.3, 15) | 7.1 (4.0, 13) |

| Reactions to severe stress unspecified | 6.7 (5.6, 8.1) | 6.2 (4.7, 8.0) | 8.4 (6.8, 11) |

| Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) | |

| Boys | |||

| Acute stress reaction | 4.6 (2.1, 10) | - | 5.0 (2.4, 8.8) |

| PTSD | - | - | - |

| Adjustment disorder | 6.1 (4.6, 8.1) | 7.1 (4.9, 10) | 6.3 (5.0, 8.0) |

| Other reactions to severe stress | 15 (4.8, 45) | - | 10 (4.4, 22) |

| Reactions to severe stress unspecified | 9.8 (6.2, 16) | 8.3 (4.6, 15) | 8.7 (6.4, 12) |

| Girls | |||

| Acute stress reaction | 6.0 (4.1, 8.9) | - | 7.4 (4.0, 13) |

| PTSD | - | - | - |

| Adjustment disorder | 7.0 (6.1, 8.0) | 4.9 (4.0, 6.0) | 10 (7.8, 13) |

| Other reactions to severe stress | 9.9 (5.6, 17) | - | 5.0 (2.2, 12) |

| Reactions to severe stress unspecified | 6.2 (5.0, 7.6) | 6.0 (4.4, 8.0) | 8.4 (6.2, 11) |

Notes: CI = confidence interval; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder

Full stress cohort models are adjusted for age, sex, and baseline depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorders.

Sex stratified models are adjusted for age and baseline depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorders.

Results not presented when fewer than five incident psychiatric disorder cases were identified.

We also examined effect modification by sex in the associations between stress disorders and incident psychiatric disorders (Table 2). Small cell sizes (<5) limited calculation of estimates of associations between stress disorders and incident psychiatric diagnoses in some cases. With respect to all incident diagnoses, the pattern across boys and girls was similar. For instance, for anxiety disorders, relative to comparison controls, boys with a baseline diagnosis of reaction to severe stress unspecified had a hazard ratio of 8.3 (95% CI: 4.6, 15) and girls had a hazard ratio of 6.0 (95% CI: 4.4, 8.0). The hazard ratio for the association between adjustment disorder and behavior disorders for boys was 6.3 (95% CI: 5.0, 8.0) whereas the hazard ratio for girls was 10 (95% CI: 7.8, 13). Overall, there was no evidence of possible effect modification by sex on the multiplicative scale.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge this is the first prospective longitudinal population-based study of school-aged children and adolescents examining rates of incident psychiatric disorders following diagnosis of a range of stress disorders. At baseline, our study sample had a higher proportion of girls diagnosed with a stress disorder than boys, and most children with stress disorder diagnoses were older (12–15 years). These findings are consistent with existing data indicating a higher prevalence of PTSD among women relative to men in adult samples (3), and in the limited available findings from another population-based study of U.S. adolescents, using the National Comorbidity Survey Replication – Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) (1). A greater proportion of older children in the stress cohort had stress disorder diagnoses than younger children. This may represent the developmental course of stress disorders such that symptoms may emerge or worsen in adolescence. This may also be consistent with other population-based data showing an increase in rates of potentially traumatic events with increasing age, although this study could not assess this directly (2). At baseline, across the full stress cohort, behavior disorders were most common, followed by depressive disorders.

Regardless of the type of stress disorder diagnosis, the rates for all three types of incident comorbid disorders – anxiety, depressive, and behavior disorders – were elevated compared to the comparison cohort, which includes children who may have experienced trauma or severe stress but had no stress or adjustment disorder diagnoses. Thus, severe stress disorders in childhood may confer a transdiagnostic diathesis for a range of mental disorders rather than disorder-specific risk. These findings are also consistent with multiple adult samples, including adults in this stress cohort (4, 15). Etiological research suggests that regulatory mechanisms (e.g., stress- and immune-related) are affected by traumatic and stressful events and play a role in disease risk for multiple psychiatric disorders (16). This is consistent with a population-based cross-sectional study of U.S. adolescents using NCS-A data examining trauma and other severe stressors that found an increased risk for a range of psychiatric comorbidities in adolescents (2), and our findings that children in the stress cohort were more likely to be diagnosed with a greater number of incident psychiatric diagnoses.

To the extent that stress disorders represent a range in ICD disorder severity based on the number and types of symptoms (e.g. children who do not meet criteria for PTSD are diagnosed with another less severe stress disorder such as an adjustment disorder), our findings also suggest that being diagnosed with a more or less severe stress disorder is not differentially associated with risk for future diagnoses. For instance, in our sample, children across all stress diagnoses had comparable risk for all incident psychopathology. One possible explanation for this finding is that the structure of PTSD may differ across developmental stages and the criteria may be more representative of adult manifestations (17, 18) and hence, diagnostic specificity across stress diagnoses may not be comparable to adult samples. For instance, studies with children have found that exposure to trauma (19) or severe stressors (2) exhibit a broad range of disorders. However, adult studies have also reported similar findings wherein individuals diagnosed with PTSD and those with subthreshold PTSD symptoms (i.e., those who suffer from posttraumatic stress symptoms but do not meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD) present with comparable functional impairment and risk for incident psychiatric comorbidity (4, 20, 21), and also other deleterious outcomes such as risk for re-traumatization, suicidality, and all-cause mortality (4). An alternate explanation stems from evidence suggesting that symptom severity rather than the total number of symptoms or specific symptom constellation required for an ICD diagnosis is associated with individual functional impairment (7). In addition to symptom severity, the impact of trauma or severe stressors on a range of psychological or biological outcomes (for instance the multiple domains of functioning proposed within the National Institute of Mental Health’s Research Domain Criteria framework) maybe associated with future psychopathology. Finally, individual variations in the latency of symptom development may also impact the course of psychopathology. In our study, findings related to time to incident psychopathology indicate that psychiatric comorbidity was evident earlier in the stress cohort relative to the comparison cohort. Future research needs to examine whether differences in the time to incident psychopathology diagnoses represent a natural disorder course (i.e. manifestation of pathophysiology following trauma or severe stressor exposure), or an artifact of how diagnoses are made (i.e., symptoms of incident disorders may be recognized sooner as part of a post-trauma or severe stress presentation and less so in the absence of a traumatic or severe stressor related disorder).

With respect to sex-related findings, our study did not identify a pattern of differences, which is consistent with findings from the NCS-A, indicating no differences in psychiatric outcomes between adolescent boys and girls who had experienced a range of childhood adversities (2). It is possible that sex-related differences noted in adult samples become more clearly established later in the life course.

It is notable that the unpredictable nature of most traumatic events and severe stressors makes data collection for stress studies uniquely challenging, and extensive primary data collection is often prohibitive in terms of the cost and time involved. Thus, a majority of studies tend to be retrospective, focus on an index trauma or severe stressor and/or PTSD, rather than a range of posttraumatic diagnoses or reactions. Thus, the use of prospectively collected longitudinal data from a large unselected sample that draws from the full country population is a methodological strength of this study. In addition to this strength, our study has important limitations that should be kept in mind when evaluating our results. First, this sample only includes patients who had a stress diagnosis diagnosed by a mental health professional. It is possible that children diagnosed by a general practitioner, who may present with a less severe presentation, were under sampled in the stress cohort. Second, given the health care and social support systems for Danish individuals (i.e. tax-supported universal health care that enables all members to receive health care at no cost) relative to other countries with available population-based studies of children (e.g., NCS-A in the U.S.), and the lack of racial/ethnic variability in our sample, our study findings need to be replicated in other samples and countries. Third, despite the large sample size, the frequency of certain stress disorders (e.g., PTSD) in our study were low relative to other population-based studies (1). Accordingly, some of the cell sizes for sex-related stratified analyses were too small to reliably examine associations. These associations need to be examined further in future research. Within the current sample, PTSD is a rare mental disorder and thus the strength of bias from exposure misclassification in observed associations will be driven by specificity. A previous validation study of stress diagnoses in the DPCRR found that no one in the comparison cohort had PTSD (13), indicating that specificity is 100 percent. Non-differential misclassification of PTSD with perfect specificity is expected to have limited impact on validity. Fourth, this study does not include data on traumatic events or severe stressors preceding, or subsequent to, stress disorder diagnoses. Causal pathways for incident psychiatric disorders may occur through stress disorders or through unmeasured traumatic events, severe stressors or other mechanisms. Future studies accounting for traumatic events or severe stressors and psychiatric diagnoses are necessary.

Results from this study suggest a need to examine a broad range of posttraumatic or severe stress reactions using a transdiagnostic multidimensional approach, akin to the Research Domain Criteria framework proposed by the National Institute of Mental Health. One option is to use person-centered approaches (e.g., latent class or latent profile analyses) that identify homogenous subsets of individuals based on their post-trauma or severe stressors diagnoses or symptoms, other relevant indicators (e.g., sex, symptom severity, functional impairment, latency of symptom development), and characteristics of the trauma or severe stressor history itself (e.g., chronicity of stressors or revictimization, (2, 22-24), timing of trauma or severe stressor exposure (24), and type of trauma or severe stressor (2)), within a larger heterogeneous sample. For instance, one study using this approach, examined psychopathology outcomes in a sample of 815 adults at age 20 following exposure to “early social stress” (perinatal through age 5), found support for two broad latent dimensions of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, rather than disorder-specific vulnerability (14). With respect to treatment implications, our study findings lend support to the increasing attention towards developing transdiagnostic, rather than disorder-specific, assessment and treatment models (19, 25). Etiologically relevant operationalization of traumatic or severe stress reactions via multidimensional clinical outcomes within a longitudinal framework are necessary first steps to diagnostic clarity, which is central to prevention and intervention efforts.

In conclusion, this prospective population-based study contributes to the literature on the longitudinal course of a broad range of stress-related diagnoses in school-age children. We show that the rate of incident depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorders are comparable across a range of stress disorders. Future research within a longitudinal framework, particularly in diverse samples, is needed to examine transdiagnostic approaches in the course of post-trauma psychopathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Jaimie Gradus, Timothy L. Lash, and Henrik Toft Sørensen were funded by R01MH109507, R01MH110453, and R21MH094551.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: None

Contributor Information

Archana Basu, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, 677 Huntington Avenue, Kresge Building, Boston, MA, USA 02115..

Dóra Körmendiné Farkas, Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark.

Tammy Jiang, Department of Epidemiology, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Karestan C. Koenen, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Timothy L. Lash, Department of Epidemiology, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Henrik Toft Sørensen, Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark.

Jaimie L. Gradus, Department of Epidemiology, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Hill ED, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(8):815–30 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky A, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:1151–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gradus JL. Prevalence and prognosis of stress disorders: a review of the epidemiologic literature. Clin Epidemiol. 2017;9:251–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gradus JL, Antonsen S, Svensson E, Lash TL, Resick PA, Hansen JG. Trauma, comorbidity, and mortality following diagnoses of severe stress and adjustment disorders: a nationwide cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182(5):451–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrion VG, Weems CF, Ray R, Reiss AL. Toward an empirical definition of pediatric PTSD: the phenomenology of PTSD symptoms in youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(2):166–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim BN, Kim JW, Kim HW, Shin MS, Cho SC, Choi NH, et al. A 6-month follow-up study of posttraumatic stress and anxiety/depressive symptoms in Korean children after direct or indirect exposure to a single incident of trauma. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(8):1148–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen JA, Scheeringa MS. Post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis in children: challenges and promises. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(1):91–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen P, Cohen J. The clinician's illusion. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41(12):1178–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Adelborg K, Sundbøll J, Laugesen K, Ehrenstein V, et al. The Danish Healthcare System and Epidemiological Research:From healthcare contacts to database records. Clinical Epidemiology. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heide-Jorgensen U, Adelborg K, Kahlert J, Sorensen HT, Pedersen L. Sampling strategies for selecting general population comparison cohorts. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:1325–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(8):541–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Svensson E, Lash TL, Resick PA, Hansen JG, Gradus JL. Validity of reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorder diagnoses in the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Registry. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conway CC, Raposa EB, Hammen C, Brennan PA. Transdiagnostic pathways from early social stress to psychopathology: a 20-year prospective study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh K, McLaughlin KA, Hamilton A, Keyes KM. Trauma exposure, incident psychiatric disorders, and disorder transitions in a longitudinal population representative sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;92:212–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danese A SJL. Psychoneuroimmunology of Early-Life Stress: The Hidden Wounds of Childhood Trauma? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(1):99–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao X, Wang L, Cao C, Zhang J, Elhai JD. PTSD Latent Classes and Class Transitions Predicted by Distress and Fear Disorders in Disaster-Exposed Adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayer L, Danielson CK, Amstadter AB, Ruggiero K, Saunders B, Kilpatrick D. Latent classes of adolescent posttraumatic stress disorder predict functioning and disorder after 1 year. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(4):364–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Andrea W, Ford J, Stolbach B, Spinazzola J, van der Kolk BA. Understanding interpersonal trauma in children: why we need a developmentally appropriate trauma diagnosis. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(2):187–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Friedman MJ, Ruscio AM, Karam EG, Shahly V, et al. Subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder in the world health organization world mental health surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(4):375–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall RD, Olfson M, Hellman F, Blanco C, Guardino M, Struening EL. Comorbidity, impairment, and suicidality in subthreshold PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(9):1467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams ZW, Moreland A, Cohen JR, Lee RC, Hanson RF, Danielson CK, et al. Polyvictimization: Latent profiles and mental health outcomes in a clinical sample of adolescents. Psychol Violence. 2016;6(1): 145–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cater AK, Andershed AK, Andershed H. Youth victimization in Sweden: prevalence, characteristics and relation to mental health and behavioral problems in young adulthood. Child abuse & neglect. 2014;38(8):1290–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pratchett LC, Yehuda R. Foundations of posttraumatic stress disorder: does early life trauma lead to adult posttraumatic stress disorder? Dev Psychopathol. 2011;23(2):477–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gutner CA, Galovski T, Bovin MJ, Schnurr PP. Emergence of Transdiagnostic Treatments for PTSD and Posttraumatic Distress. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(10):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.