To the editor:

Renal involvement, in the form of acute kidney injury, hematuria, and/or proteinuria, is common in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).1 Postmortem renal histology has shown acute tubular injury, microvascular thrombi, and inflammation2, 3, 4, 5; collapsing focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis has been reported in live patient biopsies.6 The pathogenesis of renal injury remains unclear. Direct viral cytopathic injury is possible, due to expression of viral receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on tubular epithelial cells. Indirect immunologic and/or prothrombotic infection-related effects may also be at play. Using electron microscopy, putative virions have been described in tubular epithelial cells,2 , 4 , 5 endothelial cells,3 and podocytes.6 We performed electron microscopy on 3 biopsies from live patients with COVID-19, from different centers, and found images similar to those reported in the literature (Figure 1 a, e, f, and i). Consultation among renal pathologists, electron microscopists, and virologists led to the conclusion that the intracellular structures represented clathrin-coated vesicles and microvesicular bodies, whereas the extracellular structures represented extruded microvesicles from microvesicular bodies and degenerate microvilli (Figure 1c, d, and h). Examination of biopsies taken in 2019, preceding the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), revealed identical structures (Figure 1b, g, and j). Microvesicular bodies and clathrin-coated vesicles are both part of the endosomal pathway. Microvesicular bodies may fuse with lysosomes and autophagosomes, leading to variable appearances. Clathrin-coated vesicles arise from clathrin-coated pits; their clathrin coat resembles a crown on electron microscopy. Electron microscopy has an important role to play in elucidating the pathogenesis of COVID-19, along with identification of viral RNA or proteins, but images need to show features that are clearly distinct from viral look-a-like subcellular structures.

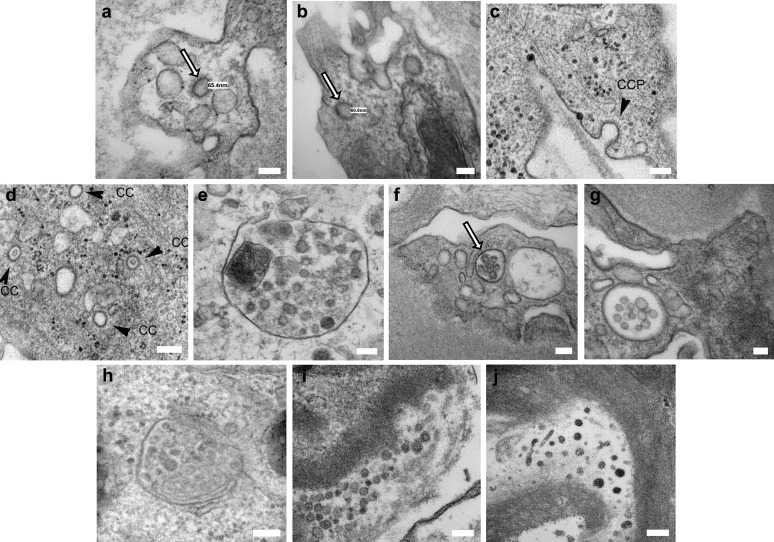

Figure 1.

(a) Transplant patient 2 weeks post-positive nasal swab for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2), with graft dysfunction and borderline for T cell–mediated rejection on biopsy; endothelial cell containing a clathin-coated vesicle with a “corona,” 65 nm in diameter (white arrow; bar = 100 nm, original magnification×20,000). (b) Transplant patient biopsied in August 2019 with graft dysfunction and borderline for T cell–mediated rejection on biopsy, showing an endothelial cell containing identical structures (white arrow; bar = 100 nm; original magnification ×20,000). (c) Clathrin-coated pits (CCP; arrowhead) at the plasma membrane (renal proximal tubular epithelial cells; bar = 100 nm). (d) Clathrin-coated intracytoplasmic vesicles (CC; arrowheads; renal proximal tubular epithelial cells; bar = 100 nm). (e) Native renal biopsy from a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and collapsing focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis; podocyte containing a microvesicular body/autophagosome (bar = 100 nm, original magnification ×98,000). (f) Same patient as (a); microvesicular body in a podocyte (white arrow; bar = 100 nm, original magnification ×15,000). (g) Same patient as (b); microvesicular body in a podocyte (bar = 100 nm, original magnification ×15,000). (h) Microvesicular body typical for adult human cell lines in culture (HeLa cells; bar = 200 nm). (i) Same patient as (e); extracellular structures along the glomerular basement membrane with “corona” 42 to 70 nm in diameter, likely either extruded microvesicles or degenerate microvilli (bar = 200 nm, original magnification ×68,000). (j) Patient with a native renal biopsy from December 2019 showing extracellular structures similar to those in (i) in an ischemic glomerulus (bar = 200 nm, original magnification ×68,000). To optimize viewing of this image, please see the online version of this article at www.kidney-international.org.

References

- 1.Cheng Y., Luo R., Wang K. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97:829–838. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diao B., Wang C., Wang R. Human kidney is a target for novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. medRxiv2020. Available at: Accessed April 3, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Varga S., Flammer A., Steiger P. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su H., Yang M., Wan C. Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int. 2020;98:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farkash E, Wilson A, Jentzen J. Ultrastructural evidence for direct renal infection with SARS-CoV-2 [e-pub ahead of print]. J Am Soc Nephrol. 10.1681/ASN.2020040432. Accessed May 6, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Kissling S., Rotman S., Gerber C. Collapsing glomerulopathy in a COVID-19 patient. Kidney Int. 2020;98:228–231. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]