Abstract

Aim: In patients with hyperlipidemia, intolerance to statins presents a challenge in reducing the risk of events associated with cardiovascular disease. This phase 3, randomized, double-blind trial in Japanese patients with statin intolerance aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of evolocumab vs. ezetimibe in lowering low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C).

Methods: This study was conducted in a 12-week, double-blind period followed by an open-label extension designed to characterize 1 year of evolocumab treatment. Statin intolerance was defined as failure of two or more statins due to myalgia, myositis, or rhabdomyolysis. Eligible patients were randomized at 2:2:1:1 into four groups: 420 mg evolocumab every 4 weeks (Q4W) + oral placebo daily, 140 mg evolocumab every 2 weeks (Q2W) + oral placebo daily, subcutaneous (SC) placebo Q4W + 10 mg ezetimibe daily, and SC placebo Q2W + 10 mg ezetimibe daily.

Results: Sixty-one patients were randomized to evolocumab (n = 40) or ezetimibe (n = 21). For the co-primary endpoints of percent change from the baseline in mean LDL-C to the mean of weeks 10 and 12 and to week 12, the evolocumab-ezetimibe treatment differences were −39.4% (95% CI, −47.2% to −31.5%) and −40.1% (95% CI, −48.7% to −31.6%), respectively (adjusted p < 0.0001). The most common adverse events were diarrhea (9.5%) and nasopharyngitis (12.5%) in the ezetimibe and evolocumab groups, respectively, during the double-blind period and nasopharyngitis (29%) during the open-label extension.

Conclusion: Evolocumab was superior to ezetimibe in reducing LDL-C during the 12-week double-blind period in this population of Japanese patients with statin intolerance, with efficacy and safety results maintained for 1 year.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02634580

Keywords: Statin intolerance, Cardiovascular disease, PCSK9 inhibitor

Introduction

Observational studies have shown that statin intolerance—primarily owing to muscle-related side effects—occurs in approximately 10% of patients, in Western countries1) and Japan2). Statin nonadherence is associated with increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD)-related events3). Therefore, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C)-lowering therapy in patients at high risk of ASCVD with statin intolerance is necessary for whom ASCVD prevention is a priority. Ezetimibe monotherapy can be effective in lowering LDL-C, but the magnitude of benefit is modest at 19%4). Therefore, the major unmet need among Japanese people with hypercholesterolemia and statin intolerance is an effective lipid-lowering therapy that does not cause muscle-related side effects associated with statins.

The proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor evolocumab reduced LDL-C by 35%–40% compared with ezetimibe in Western patients with statin intolerance5–7) and reduced the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in a broad, secondary prevention clinical trial8). Evolocumab added to statin therapy has reduced LDL-C in Japanese patients with hypercholesterolemia by approximately 60%–70%9–11). To date, no trial has reported the efficacy and safety of evolocumab among Japanese patients with statin intolerance.

The GAUSS-4 trial was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of evolocumab vs. ezetimibe in Japanese patients with hyperlipidemia and statin intolerance.

Methods

Study Design

This double-blind, randomized, multicenter, phase 3 study randomized patients to evolocumab or ezetimibe at 30 sites in Japan. This study was conducted in a 12-week, double-blind period followed by an open-label extension period designed to characterize the safety and efficacy of 52 weeks of evolocumab treatment. Eligible patients were randomized at 2:2:1:1 into four groups: 420 mg evolocumab every 4 weeks (Q4W) + oral placebo daily, 140 mg evolocumab every 2 weeks (Q2W) + oral placebo daily, subcutaneous (SC) placebo Q4W + 10 mg ezetimibe daily, and SC placebo Q2W + 10 mg ezetimibe daily. Randomization was stratified by screening the LDL-C level (< or ≥ 180 mg/dL) and baseline statin use (yes or no). Randomization was performed using an interactive voice/web response system.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice regulations/guidelines of the International Council for Harmonisation. The protocol was approved by institutional review boards for all sites, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Patients

Eligible patients were men and women, aged 20–80 years and Japanese by self-identification, for whom at least two statins failed because of myalgia (muscle pain, ache, or weakness without creatinine kinase [CK] elevation), myositis (muscle symptoms with increased CK levels), or rhabdomyolysis (defined as CK > 10 × upper limit normal [ULN]). At least one statin treatment failure must be at or below the following dosages: 10 mg atorvastatin, 10 mg pravastatin, 20 mg fluvastatin, 2.5 mg rosuvastatin, 5 mg simvastatin, and 1 mg pitavastatin. For patients who developed rhabdomyolysis, treatment failure of only one statin at any dose was acceptable. Symptoms must be resolved or have improved when statin was discontinued or the dose was reduced. Patients must meet the LDL-C threshold based on their management category in the 2012 Japan Atherosclerosis Society Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Prevention of ASCVD in Japan12). Fasting triglycerides must be ≤ 400 mg/dL (4.5 mmol/L) at screening. Major exclusion criteria included moderate to severe heart failure; uncontrolled cardiac arrhythmia; symptomatic coronary artery disease within 3 months before screening; recently diagnosed or poorly controlled diabetes, hypertension, or hyper-/hypothyroidism; known active infection or major hematologic, renal, hepatic, metabolic, gastrointestinal, or endocrine dysfunction; systemic steroid use; pregnancy or lactation; and previous exposure to any PCSK9 inhibitor.

Study Treatment

Patients on low or atypical (dose schedule: every other day) statin therapy were required to have a stable dose for at least 4 weeks before screening and throughout the double-blind and open-label extension periods of the study. Before randomization, patients received one SC placebo injection to assess the tolerability of drug delivery via this method. Patients received placebo or evolocumab SC injections at the clinical site or in home setting during the 12-week double-blind period. Patients randomized to evolocumab received daily oral placebo, and those randomized to 10 mg ezetimibe daily received SC placebo Q4W or Q2W for 12 weeks. After 12 weeks through the end of the 1-year study, all patients received open-label evolocumab + standard of care (SOC) in accordance with local guidelines. Patients self-injected evolocumab throughout this period, and ezetimibe was no longer given as part of the trial but could have been continued as part of SOC. During the open-label extension, patients received a dosing regimen of evolocumab that matches that of evolocumab or SC placebo group to which they were randomized. All lipid and inflammatory marker results from posttreatment to week 24 were blinded until the unblinding of the clinical database.

Endpoints

Co-primary endpoints were the percent change from the baseline in LDL-C to the mean of weeks 10 and 12 and to week 12. Co-secondary endpoints at weeks 10 and 12 and at week 12 were divided into tiers 1 and 2. Tier 1 endpoints included the change from the baseline in LDL-C, the achievement of LDL-C < 70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L), and the percent change from the baseline in total cholesterol, apolipoprotein B (ApoB), and non-high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (non-HDL-C). Tier 2 endpoints included the percent change from the baseline in lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)], triglycerides, and HDL-C. The safety endpoints included adverse events (AEs), changes in safety-related key laboratory parameters, and the presence of anti-evolocumab antibodies.

Assays

Lipid concentrations were analyzed at a centralized laboratory (Medpace Reference Laboratories). For all analyses related to LDL-C, unless specified otherwise, a reflexive approach was used. When the calculated LDL-C was< 40 mg/dL or triglycerides were > 400 mg/dL, the calculated LDL-C was replaced with ultracentrifugation LDL-C from the same blood sample, if available. Patients were assessed for anti-evolocumab antibodies using the enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay by a central laboratory (Eurofins).

Statistical Analysis

Sample Size

The planned sample size for the double-blind comparison was 60 patients, of whom 40 were for evolocumab (n = 20 at Q2W and n = 20 at Q4W) and 20 were for ezetimibe (n = 10 at Q2W and n = 10 at Q4W). The primary analysis required the two-sided tests of each co-primary endpoint to be significant at a level of 0.05. Assuming that 5% of randomized patients do not receive any study drug and with a common SD of approximately 20%, the planned sample size provided at least 93% power to detect a treatment effect of at least 20% reduction for each of the co-primary endpoints in testing the superiority of evolocumab over ezetimibe, based on a two-sided t-test with a significance level of 0.05. This case provided at least 85% (93%×93%) power to detect significant treatment effects of the co-primary endpoints.

Double-Blind Period

The primary analysis of the 12-week doubleblind period was conducted using the full analysis set (all randomized patients who received at least one dose of the study drug). For the co-primary efficacy endpoints, a repeated-measure linear-effect model was used to compare the efficacies of evolocumab (Q2W and Q4W groups were pooled) and ezetimibe (pooled). The model included terms of treatment group, stratification factor of screening LDL-C level, scheduled visit, and the interaction of treatment group with scheduled visit. Missing values were not imputed when the repeated-measure linear-effect model is used because missing data can be handled using the behavior of the observed data. For the co-secondary endpoints, the statistical model and testing of the tier 1 endpoints were similar to the primary analysis of the co-primary endpoints. For tier 2 endpoints, the same analysis model as that for tier 1 was used, and the testing was conducted via a union-intersection test. Multiplicity adjustment was performed for the co-primary and co-secondary endpoints in the primary analysis via sequential testing and by using Hochberg and fallback procedures to preserve the family-wise type 1 error rate at 0.05. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Efficacy was assessed in prespecified subgroups based on baseline characteristics and randomization stratification factors. AEs during the double-blind period were coded using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 20.1. Patient incidences of AEs and other safety events were summarized descriptively by the treatment group.

Open-Label Extension Period

Long-term efficacy and safety analyses were performed on the open-label extension period analysis set (all patients who received at least one dose of evolocumab during the open-label extension period), and the analyses were descriptive. Safety analyses were reported for the open-label extension period, and AEs were coded using MedDRA version 21.0. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Patient Disposition

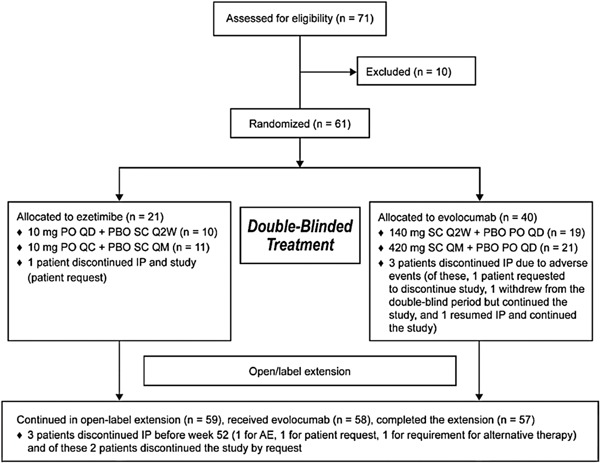

A total of 61 patients were randomized (evolocumab, n = 40; ezetimibe, n = 21) (Fig. 1). The first patient was enrolled in February 2016, and the last patient completed treatment in May 2018. During the double-blind period, four patients discontinued the investigational product (one patient in the ezetimibe group due to patient request and three patients in the evolocumab group due to AEs). Of the four patients, two (5%, one ezetimibe, one evolocumab) discontinued the study by request, one (evolocumab group) resumed the investigational product and continued in the study, and one (evolocumab group) discontinued the double-blind period but remained on the study. Fifty-eight patients (95%) completed the 12-week double-blind period. Although 59 patients entered the extension, only 58 received evolocumab and were included in the open-label extension analysis set. During the extension, three patients discontinued the investigational product (one for AE, one by patient request, and one due to requirement for alternative therapy); two of the three patients discontinued the study by request. Thus, 57 patients (97%) completed the extension. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics did not differ between treatment groups (Table 1). Overall, the mean age was 64.4 (SD, 10.6) years, and 51% of patients were female. The overall baseline LDL-C was 189.0 (SD, 53.9) mg/dL (4.9 [SD, 1.4] mmol/L). The stratification factor of screening LDL-C < or ≥ 180 mg/dL was split evenly overall and within treatment groups; 77% of patients were not taking statins at baseline, and this proportion was similar within treatment groups. Most patients (57%) were categorized as high risk in the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) criteria, and 33% had two or more cardiovascular risk factors. Medical history on statin intolerance was collected for all patients: 3.3% were intolerant to one statin, 73.8% to two statins, 16.4% to three statins, and 6.6% to four or more statins. Most patients (98%) had neither a family history of muscular symptoms nor a family history of muscular symptoms with statins. Rhabdomyolysis was the most severe muscle-related side effect in three (4.9%) patients. A total of nine (15%) patients reported non-muscle-related statin intolerance, and the most common neurocognitive symptom that led to the diagnosis of such intolerance was fatigue (n = 3, 4.9%). Rosuvastatin and atorvastatin were the most commonly reported statins associated with muscle intolerance, reported in approximately 74% and 61% of patients, respectively. The characteristics of statin intolerance (muscle-related and non-muscle-related) were similar across the treatment groups.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of Patient Disposition

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; IP, investigational product; PBO, placebo; PO, peroral; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks; QD, daily; SC, subcutaneous; SOC, standard of care.

Table 1. Baseline Demographic, Clinical, and Treatment Characteristics.

| Ezetimibe | Evolocumab | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 21) | (N = 40) | (N = 61) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 61.8 (11.9) | 65.8 (9.8) | 64.4 (10.6) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 10 (47.6) | 21 (52.5) | 31 (50.8) |

| Screening LDL-C level,§ n (%) | |||

| < 180 mg/dL | 11 (52.4) | 19 (47.5) | 30 (49.2) |

| ≥ 180 mg/dL | 10 (47.6) | 21 (52.5) | 31 (50.8) |

| Statin use,§ n (%) | 6 (28.6) | 8 (20.0) | 14 (23.0) |

| LDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 181.9 (56.1) | 192.8 (53.0) | 189.0 (53.9) |

| Triglycerides, mean (SD), mg/dL | 161.7 (95.9) | 149.6 (59.8) | 153.8 (73.7) |

| Non-HDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 214.1 (56.3) | 222.7 (52.8) | 219.8 (53.7) |

| HDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 63.4 (15.5) | 59.4 (20.1) | 60.8 (18.6) |

| Total cholesterol, mean (SD), mg/dL | 277.5 (61.0) | 282.2 (56.1) | 280.5 (57.3) |

| ApoB, mean (SD), mg/dL | 126.8 (25.0) | 139.5 (28.6) | 135.1 (27.9) |

| ApoA1, mean (SD), mg/dL | 163.9 (24.6) | 156.6 (33.0) | 159.1 (30.3) |

| Lp(a), median (Q1, Q3), nmol/L | 28.0 (19.0, 52.0) | 37.0 (16.5, 79.0) | 30.0 (17.0, 71.0) |

| hsCRP, mean (SD), mg/dL | 0.8 (1.1) | 2.0 (3.6) | 1.6 (3.0) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | |||

| NCEP high risk | 10 (47.6) | 25 (62.5) | 35 (57.4) |

| CAD | 7 (33.3) | 17 (42.5) | 24 (39.3) |

| Cerebrovascular or peripheral artery disease | 1 (4.8) | 10 (25.0) | 11 (18.0) |

| Current cigarette smoking | 1 (4.8) | 3 (7.5) | 4 (6.6) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 4 (19.0) | 7 (17.5) | 11 (18.0) |

| Hypertension | 12 (57.1) | 23 (57.5) | 35 (57.4) |

| ≥ 2 cardiovascular risk factors | 7 (33.3) | 13 (32.5) | 20 (32.8) |

| Metabolic syndrome without diabetes mellitus | 7 (33.3) | 14 (35.0) | 21 (34.4) |

| Intolerance to statins (number of statins per patient), n (%) | |||

| 1 | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (3.3) |

| 2 | 17 (81.0) | 28 (70.0) | 45 (73.8) |

| 3 | 3 (14.3) | 7 (17.5) | 10 (16.4) |

| ≥ 4 | 0 | 4 (10.0) | 4 (6.6) |

| Worst muscle-related side effect for any statin, n (%) | |||

| Myalgia | 12 (57.1) | 25 (62.5) | 37 (60.7) |

| Myositis | 7 (33.3) | 14 (35.0) | 21 (34.4) |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 2 (9.5) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (4.9) |

To convert LDL-C, HDL-C, total cholesterol, and non-HDL-C values from mg/dL to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259; triglycerides values from mg/dL to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0113; and hsCRP values from mg/L to nmol/L, multiply by 9.524. When the calculated LDL-C was < 40 mg/dL or triglycerides were > 400 mg/dL, calculated LDL-C was replaced with ultracentrifugation LDL-C from the same blood sample, if available.

Randomization stratification factor

Abbreviations: ApoA1, apolipoprotein A1; ApoB, apolipoprotein B; CAD, coronary artery disease; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); NCEP, National Cholesterol Education Program.

Efficacy

Double-Blind Period

The percent changes from the baseline in LDL-C to the mean of weeks 10 and 12 were −20.3% (SE, 2.6) with ezetimibe and −59.8% (SE, 2.5) with evolocumab; those to week 12 were −19.0% (SE, 3.0) and −59.5% (SE, 2.7), respectively. The co-primary endpoint treatment differences were −39.4% (95% CI, −47.2% to −31.5%) to the mean of weeks 10 and 12 and −40.1% (95% CI, −48.7% to −31.6%) to week 12 (adjusted p < 0.0001) (Table 2). Patients receiving evolocumab experienced statistically significant difference in percent changes from baseline in total cholesterol, non-HDL-C, ApoB, and Lp(a) compared with those receiving ezetimibe (all adjusted p < 0.001). No statistically significant differences existed between evolocumab and ezetimibe for percent changes in triglycerides and HDL-C. No patients with ezetimibe had an LDL-C of < 70 mg/dL; 22 (56%) and 20 (53%) patients with evolocumab had an LDL-C of < 70 mg/dL at the mean of weeks 10 and 12 and at week 12, respectively.

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Efficacy Endpoints With Ezetimibe as Reference Group.

| Treatment Difference to Mean of Weeks 10 and 12 | Treatment Difference to Week 12 | Adjusted p Value§ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-primary endpoints (LDL-C), Least squares mean % (95% CI) | −39.35 (−47.23, −31.48) | −40.14 (−48.68, −31.60) | < 0.0001 |

| p value§§ | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |

| Secondary endpoints, Least squares mean % (95% CI) | |||

| Total cholesterol | −25.44 (−30.80, −20.08) | −25.83 (−31.63, −20.04) | < 0.0001 |

| p value§§§ | < 0.0001 | ||

| Non-HDL-C | −33.53 (−40.38, −26.68) | −33.44 (−40.94, −25.94) | < 0.0001 |

| p value§§§ | < 0.0001 | ||

| ApoB | −35.67 (−42.30, −29.04) | −36.60 (−43.98, −29.22) | < 0.0001 |

| p value§§§ | < 0.0001 | ||

| Triglycerides | 3.49 (−11.15, 18.13) | 11.79 (−7.29, 30.87) | 0.27 |

| p value§§§§ | 0.27 | ||

| Lp(a) | −31.13 (−41.83, −20.43) | −31.21 (−43.57, −18.84) | < 0.0001 |

| p value§§§§ | < 0.0001 | ||

| HDL-C | 7.96 (1.78, 14.14) | 5.59 (−0.82, 12.00) | 0.091 |

| p value§§§§ | 0.03 | ||

When the calculated LDL-C was < 40 mg/dL or triglycerides were > 400 mg/dL, calculated LDL-C was replaced with ultracentrifugation LDL-C from the same blood sample, if available.

Adjusted p value is based on a combination of sequential testing, the Hochberg procedure, the fallback procedure to control the overall significance level for all primary and secondary endpoints. Each individual adjusted p value is compared to 0.05 to determine statistical significance.

Repeated-measures model, which includes treatment group, stratification factor of screening LDL-C level (from IVRS), scheduled visit, and the interaction of treatment with scheduled visit as covariates.

Least significant unadjusted p value of the co-secondary endpoints, using the repeated-measures model.

The unadjusted joint p value using the union-intersection test.

Abbreviations: ApoB, apolipoprotein B; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; IVRS, interactive voice response system; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a).

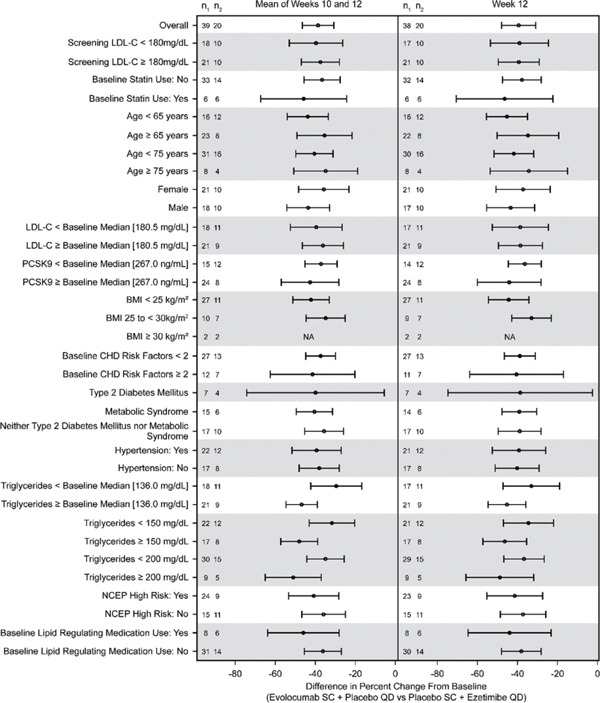

Efficacy results for the co-primary endpoints were similar between patients receiving Q2W and Q4W dosing frequencies. The co-primary endpoint results were consistent across subgroups based on baseline patient characteristics, including the randomization stratification factors of LDL-C < or ≥ 180 mg/dL and statin use, age category, sex, baseline LDL-C concentration, PCSK9, body mass index, number of coronary heart disease risk factors, NCEP high risk status, glucose tolerance status (type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, or neither), hypertension, or use of lipid-lowering medication (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Supplemental Fig. 1.

Forest Plot of Treatment Differences in Percent Change from the Baseline in LDL-C at the Mean of Weeks 10 and 12 and at Week 12—Subgroup Analyses

When the calculated LDL-C was < 40 mg/dL or triglycerides were > 400 mg/dL, calculated LDL-C was replaced with ultracentrifugation LDL-C from the same blood sample, if available. Least squares mean differences and 95% CI are from the repeated-measure model. No imputation is used for missing values. n1 = number of patients receiving evolocumab in the subgroup of interest with an observed value at the mean of weeks 10 and 12 or at week 12; n2 = number of patients receiving ezetimibe in the subgroup of interest with an observed value at the mean of weeks 10 and 12 or at week 12.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NCEP, National Cholesterol Education Program; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; QD, daily; SC, subcutaneous.

Open-Label Extension

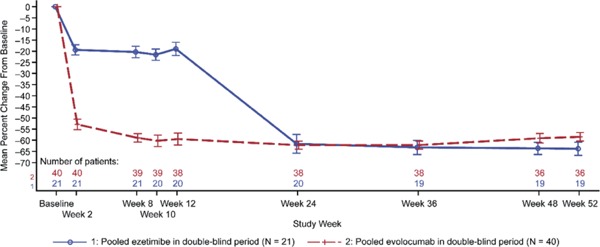

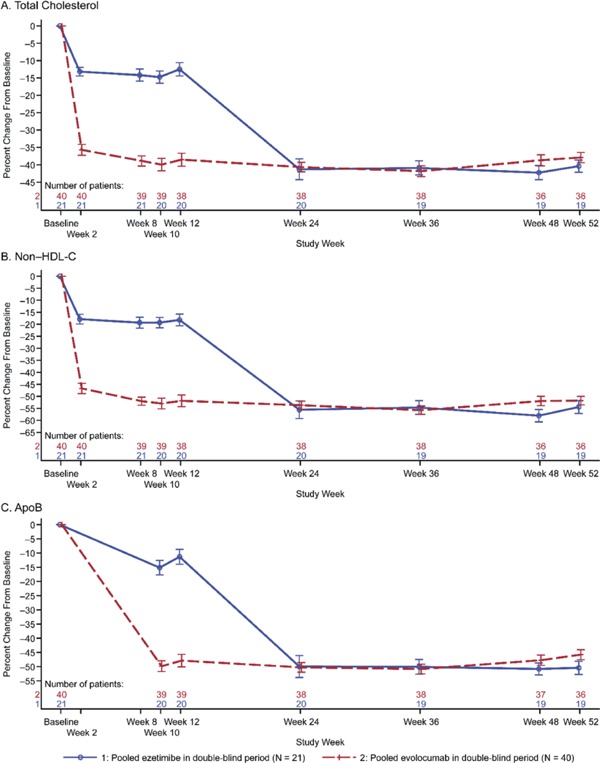

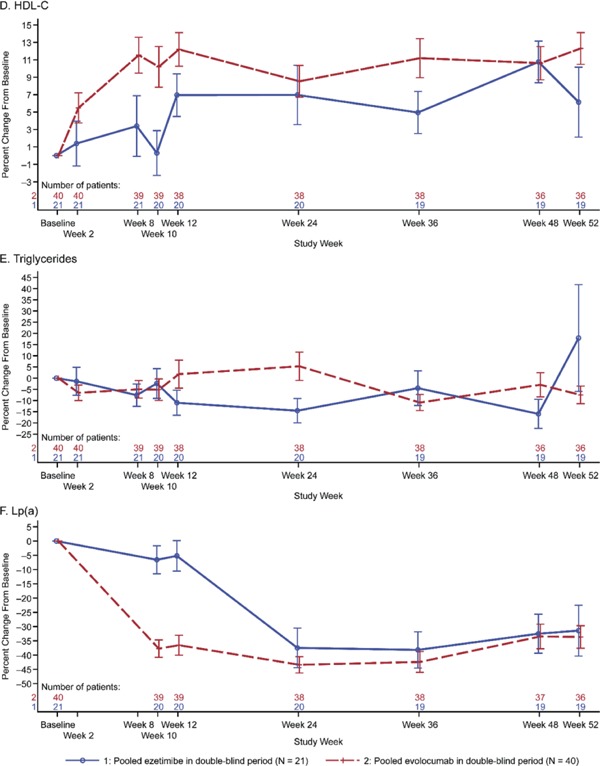

The percent change in LDL-C from baseline to week 24 was −62.0% (SD, 14.0) and was consistent through week 52 (−60.3% [SD, 12.2]) (Fig. 2). For total cholesterol, non-HDL-C, ApoB, HDL-C, LP (a), and triglycerides, the percent changes from baseline to open-label extension visits were consistent throughout the study (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Plot of Mean Percent Change from the Baseline in LDL-C by Scheduled Visit and Treatment Group

Abbreviation: LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

When the calculated LDL-C was < 40 mg/dL or triglycerides were > 400 mg/dL, calculated LDL-C was replaced with ultracentrifugation LDL-C from the same blood sample, if available. Vertical lines represent the standard error around the mean. Plot is based on observed data, and no imputation is used for missing values.

Supplemental Fig. 2-1.

Plot of Mean Percent Change from the Baseline by Scheduled Visit and Treatment Group. A, Total Cholesterol; B, Non-HDL-C; C, ApoB; D, HDL-C; E, Triglycerides; F, Lp(a)

Vertical lines represent the standard error around the mean. Plot is based on observed data, and no imputation is used for missing values.

Abbreviations: ApoB, apolipoprotein B; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a).

Supplemental Fig. 2-2.

Plot of Mean Percent Change from the Baseline by Scheduled Visit and Treatment Group. A, Total Cholesterol; B, Non-HDL-C; C, ApoB; D, HDL-C; E, Triglycerides; F, Lp(a)

Vertical lines represent the standard error around the mean. Plot is based on observed data, and no imputation is used for missing values.

Abbreviations: ApoB, apolipoprotein B; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a).

Safety

The incidences of treatment-emergent AEs were 61.9% and 57.5% with ezetimibe and evolocumab, respectively, in the double-blind period and 79.3% with evolocumab + SOC in the open-label extension (Table 3). During the double-blind period, the most common AEs were diarrhea (9.5%) in the ezetimibe group and nasopharyngitis (12.5%) and pharyngitis (10.0%) in the evolocumab group. During the openlabel extension, the most common AE was nasopharyngitis (29%). Overall, 5% of patients in both groups experienced grade ≥ 3 AEs during the double-blind period; the same rate was observed among all patients in the open-label extension. No patients experienced grade ≥ 4 AEs. In the double-blind period, two patients on ezetimibe (9.5%) experienced serious AEs (SAEs; acute myocardial infarction and osteoarthritis) vs. none with evolocumab. In the open-label extension, four patients (6.9%) experienced SAEs (myocardial ischemia, mass, lung neoplasm malignant, and transient ischemic attack; none of these events were considered related to treatment, and all patients were randomized to evolocumab in the double-blind period). In the double-blind period, no patients on ezetimibe and two patients (5%) on evolocumab discontinued the investigational product due to treatment-emergent AEs (one for muscle weakness and one for cough). In the open-label extension, one patient (1.7%) discontinued because of an AE (abnormal hepatic function). Treatment-related AEs were reported in three patients (14.3%) in the ezetimibe group and seven patients (17.5%) in the evolocumab group during the double-blind period and in seven patients (12.1%) during the open-label extension. No patients experienced treatment-emergent elevated alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, or bilirubin during the open-label extension; one patient—who had elevated CK at baseline—experienced CK > 10 × ULN at ≥ 1 visit after study initiation (during the open-label extension). No deaths occurred at any point of the study. No binding or neutralizing antidrug antibodies were detected during the study.

Table 3. Patient Incidence of Treatment-Emergent AEs.

| Double-blind Period Through Week 12 |

Open-label Extension, Evolocumab + SOC (N = 58) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ezetimibe (N = 21) |

Evolocumab (N = 40) |

||

| Study drug exposure, mean (SD), mo | 2.68 (0.50) | 2.74 (0.30) | 9.10 (0.79) |

| All treatment-emergent AEs, n (%) | 13 (61.9) | 23 (57.5) | 46 (79.3) |

| Grade ≥ 3 | 1 (4.8) | 2 (5.0) | 3 (5.2) |

| SAEs | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (6.9) |

| Leading to discontinuation of IP | 0 | 2 (5.0)§ | 1 (1.7) |

| Treatment-related | 3 (14.3) | 7 (17.5) | 7 (12.1) |

| Most commonly reported AEs, n (%) | |||

| Nasopharyngitis | 1 (4.8) | 5 (12.5) | 17 (29.3) |

| Pharyngitis | 0 | 4 (10.0) | 2 (3.4) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (9.5) | 2 (5.0) | 3 (5.2) |

| Injection site pain | 1 (4.8) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (1.7) |

| Cough | 1 (4.8) | 2 (5.0) | 2 (3.4) |

| Hypertension | 0 | 2 (5.0) | 3 (5.2) |

| Abdominal distension | 0 | 2 (5.0) | 0 |

N = number of patients who were randomized and received investigational product in the full analysis set for the double-blind period, or the number of patients who continued in the open-label extension period of the study and received evolocumab

AEs were coded using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 20.1 during the double-blind period, and version 21.0 during the open-label period.

Assessed as nonserious.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; IP, investigational product; SAE, serious adverse event; SOC, standard of care.

Discussion

In this double-blind, ezetimibe-controlled study in Japanese patients unable to tolerate an effective dose of a statin, treatment with 12 weeks of evolocumab was superior to that with ezetimibe in reducing LDL-C and improving other lipid parameters of interest, including non-HDL-C, ApoB, and Lp(a). During the 1-year open-label all evolocumab extension, the reduction in LDL-C from baseline at week 12 was maintained through week 52. Treatment with 12 weeks of evolocumab was also superior to ezetimibe in achieving LDL-C < 70 mg/dL. AEs with evolocumab were similar to those with ezetimibe, including the patient incidence and severity of AEs, the incidence of AEs leading to treatment discontinuation, and the incidence of SAEs. No trends indicative of abnormalities in clinically important treatment-related laboratory parameters were observed, and no evidence of anti-evolocumab antibodies existed.

The study populations in GAUSS-4 were similar to the earlier studies5–7), with slight differences: the mean age was slightly older (64 years) than prior studies (58–62 years) and the percentage of patients with two or more CVD risk factors was slightly lower (33% compared with 48% in GAUSS-3). However, the percentage with high risk by NCEP criteria was approximately 60% in all four studies. For the baseline statin history, the proportion of patients with rhabdomyolysis as the worst muscle-related side effect was 5% in GAUSS-4, compared with 2% in GAUSS-2 and 6% after statin rechallenge in GAUSS-3. We note that while GAUSS-2 and GAUSS-3 required intolerance to two or more statins, GAUSS-4 allowed patients with intolerance to a single statin in the case of rhabdomyolysis, which may have increased the observed rate compared with the other two studies. GAUSS-4 had a much smaller sample size (n = 61) than GAUSS (n = 160), GAUSS-2 (n = 307) and GAUSS-3 phase B (n = 218); thus, the estimate of rhabdomyolysis rate is further variable given the low incidence (three patients in total in GAUSS-4).

Efficacy, in terms of the treatment difference between ezetimibe and evolocumab, was similar in the four GAUSS studies: −39% to −40% reduction in LDL-C in GAUSS-4 compared with −36% to −38% in GAUSS-3, −37% to −39% in GAUSS-2, and −26% to −41% in GAUSS. Safety results were also similar across the studies with no notable differences between the ezetimibe and evolocumab groups. GAUSS-4 had a similar design to GAUSS-2 5 (i.e., a practical definition of statin intolerance without a placebo-controlled statin rechallenge). However, the efficacy and safety results for GAUSS-2 and GAUSS-4 were similar to that for the GAUSS-3 trial, which did include a placebo-controlled statin rechallenge5–7). The GAUSS-4 trial, combined with its open-label extension, also demonstrated efficacy and safety similar to that of the broad statin-intolerance subgroup of the OSLER studies13). Finally, the GAUSS-4 study demonstrated a safety profile similar to that of the YUKAWA randomized studies and Japan-only subgroup of the OSLER studies9–11). Similarly, the PCSK9 inhibitor alirocumab had been demonstrated superior to ezetimibe in the ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE trial, with a mean treatment difference of −30%14). PCSK9 inhibitors were also well tolerated in the clinical practice setting in a small chart review study15). Thus, the results of the present study add to the body of evidence for the use of PCSK9 inhibitors in populations with statin intolerance (Alonso et al.16)) and supplement the established evidence for the efficacy and safety of these medicines in the Japanese population17).

The limitations of the study include a small study population and a lack of statin rechallenge in the study design for objectively identifying statin-intolerant patients.

Conclusion

Evolocumab was superior to ezetimibe in reducing LDL-C in this population of Japanese patients with hypercholesterolemia and statin intolerance, thereby demonstrating a favorable benefit: risk profile. These results were similar to those observed in non-Japanese patients with statin intolerance in the GAUSS-2 study.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Amgen Inc. We thank the investigators who participated in the study (Suppl Appendix). Tim Peoples, MA, ELS, of Amgen Inc. and Wanda Krall, PhD, on behalf of Amgen Inc., assisted the authors in writing the manuscript.

Qualified researchers may request data from Amgen clinical studies. Complete details are available at the following: https://wwwext.amgen.com/science/clinical-trials/clinical-data-transparencypractices/

Conflict of Interest

Shinji Koba reports speaker's honoraria from MSD and Takeda.

Ikuo Inoue reports honoraria from Sanofi.

Kouji Kajinami reports unrestricted research grants (modest) from Daiichi-Sankyo, Takeda, Astellas, Dainippon-Sumitomo, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bayer, Fujifilm, Central Medical, and St. Jude Medical; research grant (modest) from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Marcoli Cyrille, Chen Lu, and Hyoe Inomata are employees of Amgen Inc. and hold Amgen Inc. stock.

Junichiro Shimauchi is an employee of Amgen Astellas Biopharma K.K.

Supplemental Appendix

List of investigators and sites

| Principal Investigator | Site |

|---|---|

| Shinji Koba | Showa University Hospital, Tokyo |

| Toshiyuki Sugiura | Sugiura Clinic, Saitama |

| Kenshi Fujii | Sakurabashi Watanabe Hospital, Osaka |

| Minoru Nozaki | Medical Corporation Shirayurikai Swing Nozaki Clinic, Tokyo |

| Arihiro Kiyosue | Tokyo-Eki Center Building Clinic, Tokyo |

| Hiroki Kamata | Medical Corporation Kuon-kai Kamata Medical Clinic, Iwate |

| Tatsuyuki Sato | Sato Hospital, Miyagi |

| Yasuaki Teshima | Medical Corporation Sanaikai Ikeda Memorial Hospital, Fukushima |

| Nobuyoshi Higa | Okinawa Tokushukai Medical Corporation Chubu Tokushukai Hospital, Okinawa |

| Kouji Kajinami | Kanazawa Medical University Hospital, Ishikawa |

| Yusuke Fujino | New Tokyo Heart Clinic, Chiba |

| Koh Ono | Kyoto University Hospital, Kyoto |

| Tatsuro Ishida | Kobe University Hospital, Hyogo |

| Yoshiro Maezawa Previously: Koutaro Yokote, Minoru Takemoto |

Chiba University Hospital, Chiba |

| Koin Watanabe Previously: Daisuke Yabe |

Kansai Electric Power Hospital, Osaka |

| Mamoru Nanasato Previously: Haruo Hirayama |

Japanese Red Cross Nagoya Daini Hospital, Aichi |

| Takahiro Saeki Previously: Akio Chikata, Satoru Sakagami |

National Hospital Organization Kanazawa Medical Center, Ishikawa |

| Kenichi Tsujita | Kumamoto University Hospital, Kumamoto |

| Yasuki Kihara | Hiroshima University Hospital, Hiroshima |

| Ikuo Inoue | Saitama Medical University Hospital, Saitama |

| Hideki Ishii | Nagoya University Hospital, Aichi |

| Hiroshi Nakane Previously: Jiro Kitayama |

National Hospital Organization Fukuoka-Higashi Medical Center, Fukuoka |

| Mitsuru Ohishi | Kagoshima University Hospital, Kagoshima |

| Yasushi Ishigaki | Iwate Medical University Hospital, Iwate, |

| Kazunori Iwade | National Hospital Organization Yokohama Medical Center, Kanagawa |

| Masao Kuwada | SMC the Yamatokai Foundation Central Clinic affiliated clinic of Higashiyamato Hospital, Tokyo |

| Toshinori Higashikata | Komatsu Municipal Hospital, Ishikawa |

| Ryoichi Ishibashi | Kimitsu Chuo Hospital, Chiba |

| Toshiyuki Takahashi | Koga General Hospital, Ibaraki |

| Toshiaki Kadokami | Saiseikai Futsukaichi Hospital, Fukuoka |

References

- 1). Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, Yau C, Bégaud B: Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients--the PRIMO study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther, 2005; 19: 403-414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Nagar SP, Rane PP, Fox KM, Meyers J, Davis K, Beaubrun A, Inomata H, Qian Y, Kajinami K: Treatment patterns, statin intolerance, and subsequent cardiovascular events among Japanese patients with high cardiovascular risk initiating statin therapy. Circ J, 2018; 82: 1008-1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Riaz H, Khan AR, Khan MS, Rehman KA, Alansari SAR, Gheyath B, Raza S, Barakat A, Luni FK, Ahmed H, Krasuski RA: Meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized controlled trials on the prevalence of statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol, 2017; 120: 774-781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Pandor A, Ara RM, Tumur I, Wilkinson AJ, Paisley S, Duenas A, Durrington PN, Chilcott J: Ezetimibe monotherapy for cholesterol lowering in 2,722 people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Intern Med, 2009; 265: 568-580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Sullivan D, Olsson AG, Scott R, Kim JB, Xue A, Gebski V, Wasserman SM, Stein EA: Effect of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9 on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in statin-intolerant patients: the GAUSS randomized trial. JAMA, 2012; 308: 2497-2506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Stroes E, Colquhoun D, Sullivan D, Civeira F, Rosenson RS, Watts GF, Bruckert E, Cho L, Dent R, Knusel B, Xue A, Scott R, Wasserman SM, Rocco M: Anti-PCSK9 antibody effectively lowers cholesterol in patients with statin intolerance: the GAUSS-2 randomized, placebocontrolled phase 3 clinical trial of evolocumab. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2014; 63: 2541-2548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Nissen SE, Stroes E, Dent-Acosta RE, Rosenson RS, Lehman SJ, Sattar N, Preiss D, Bruckert E, Ceska R, Lepor N, Ballantyne CM, Gouni-Berthold I, Elliott M, Brennan DM, Wasserman SM, Somaratne R, Scott R, Stein EA: Efficacy and tolerability of evolocumab vs ezetimibe in patients with muscle-related statin intolerance: the GAUSS-3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 2016; 315: 1580-1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Honarpour N, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, Kuder JF, Wang H, Liu T, Wasserman SM, Sever PS, Pedersen TR, FOURIER Steering Committee Investigators : Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med, 2017; 376: 1713-1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Hirayama A, Honarpour N, Yoshida M, Yamashita S, Huang F, Wasserman SM, Teramoto T: Effects of evolocumab (AMG 145), a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9, in hypercholesterolemic, statin-treated Japanese patients at high cardiovascular risk--primary results from the phase 2 YUKAWA study. Circ J, 2014; 78: 1073-1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Kiyosue A, Honarpour N, Kurtz C, Xue A, Wasserman SM, Hirayama A: A phase 3 study of evolocumab (AMG 145) in statin-treated Japanese patients at high cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol, 2016; 117: 40-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Hirayama A, Yamashita S, Inomata H, Kassahun H, Cyrille M, Ruzza A, Yoshida M, Kiyosue A, Ma Y, Teramoto T: One-year efficacy and safety of evolocumab in Japanese patients- a pooled analysis from the openlabel extension OSLER studies. Circ J, 2017; 81: 1029-1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ishibashi S, Birou S, Daida H, Dohi S, Egusa G, Hiro T, Hirobe K, Iida M, Kihara S, Kinoshita M, Maruyama C, Ohta T, Okamura T, Yamashita S, Yokode M, Yokote K, Japan Atherosclerosis Society : Executive summary of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) guidelines for the diagnosis and prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases in Japan -2012 version. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2013; 20: 517-523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Cho L, Dent R, Stroes ESG, Stein EA, Sullivan D, Ruzza A, Flower A, Somaratne R, Rosenson RS: Persistent Safety and Efficacy of Evolocumab in Patients with Statin Intolerance: a Subset Analysis of the OSLER Open-Label Extension Studies. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther, 2018; 32: 365-372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Moriarty PM, Thompson PD, Cannon CP, Guyton JR, Bergeron J, Zieve FJ, Bruckert E, Jacobson TA, Kopecky SL, Baccara-Dinet MT, Du Y, Pordy R, Gipe DA, Investigators OA : Efficacy and safety of alirocumab vs ezetimibe in statin-intolerant patients, with a statin rechallenge arm: The ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE randomized trial. J Clin Lipidol, 2015; 9: 758-769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Davidson ER, Snider MJ, Bartsch K, Hirsch A, Li J, Larry J: Tolerance of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors in patients with selfreported statin intolerance. J Pharm Pract, 2018; 897190018799218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Alonso R, Cuevas A, Cafferata A: Diagnosis and Management of Statin Intolerance. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2019; 26: 207-215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Kinoshita M, Yokote K, Arai H, Iida M, Ishigaki Y, Ishibashi S, Umemoto S, Egusa G, Ohmura H, Okamura T, Kihara S, Koba S, Saito I, Shoji T, Daida H, Tsukamoto K, Deguchi J, Dohi S, Dobashi K, Hamaguchi H, Hara M, Hiro T, Biro S, Fujioka Y, Maruyama C, Miyamoto Y, Murakami Y, Yokode M, Yoshida H, Rakugi H, Wakatsuki A, Yamashita S, Committee for E, Clinical Management of A : Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) Guidelines for Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases 2017. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2018; 25: 846-984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]