Abstract

Heme proteins are ideal systems to investigate vibrational energy flow at the atomic level. Upon photoexcitation, a large amount of excess vibrational energy is selectively deposited on heme due to extremely fast internal conversion. This excess energy is redistributed to the surrounding protein moiety and then to water. Vibrational energy flow in myoglobin (Mb) was examined using picosecond time-resolved anti-Stokes ultraviolet resonance Raman (UVRR) spectroscopy. We used the Trp residue directly contacting the heme group as a selective probe for vibrationally excited populations. Trp residues were placed at different position close to the heme by site-directed mutagenesis. This technique allows us to monitor the excess energy on residue-to-residue basis. Anti-Stokes UVRR measurements for Mb mutants suggest that the dominant channel for energy transfer in Mb is the pathway through atomic contacts between heme and nearby amino acid residues as well as that between the protein and solvent water. It is found that energy flow through proteins is analogous to collisional exchange processes in solutions.

Keywords: Vibrational energy transfer, Heme protein, Time-resolved anti-Stokes ultraviolet resonance Raman scattering, Atomic contacts

Introduction

Energy flow in proteins is fundamentally important to protein function. In solutions, the excess vibrational energy deposited at solute molecules is exchanged to solvent molecules through dynamic collisions with the first solvation shell, and then through sequential collisions with the higher layer of solvating molecules (Iwata and Hamaguchi 1997; Mizutani and Kitagawa 2001). The vibrational energy is transferred in the protein in analogy to the environment in solutions. Real-time observation of energy flow with a spatial resolution at the atomic level gives us a definitive understanding of the energy exchange process in proteins. To draw a microscopic picture of energy flow, one approach is to excite a specific group and to probe energy redistribution in the surroundings.

Heme proteins are ideal molecules for microscopically observing energy flow in proteins. Vibrational excess energy as large as about 25,000 cm−1 is selectively deposited on the heme group immediately after photoexcitation, resulting from extremely fast internal conversion occurring within 100 fs via the Soret transition (Champion and Lange 1980). The heme group acts as an impulsive heat source in the protein. Subsequent vibrational energy dissipation processes have been elucidated using ultrafast spectroscopic studies. It has been revealed that the energy of the vibrationally excited heme is redistributed to its surroundings with time constants of a few picoseconds (Franzen et al. 1995; Gao et al. 2006; Koyama et al. 2006; Lim et al. 1996; Mizutani and Kitagawa 1997; Ye et al. 2003) and that the released energy from the heme group is dissipated from the protein into solvent water with a time constant of less than 20 ps (Genberg et al. 1989; Lian et al. 1994). Although the timescales of energy relaxation of heme and energy release to solvent water have been characterized, experimental difficulties have limited our understandings of the vibrational energy flow processes in the protein.

A technique is needed for observing vibrational energy flow processes in a protein molecule. To address this need, we have developed a technique using picosecond time-resolved anti-Stokes ultraviolet resonance Raman (UVRR) spectroscopy. To monitor transient excess vibrational energy redistributed from heme, we observe temporal evolution of the anti-Stokes Raman intensities of the amino acid residue at a specific site in a protein moiety. Because the electronic transition of Trp is located in the UV region, Raman bands of Trp are highly sensitive due to the resonance effect under UV excitation conditions (Harada and Takeuchi 1986). Anti-Stokes scattering can be generated from vibrationally excited molecules, and thus the anti-Stokes Raman intensities directly reflect the vibrationally excited populations. Time-resolved measurements of the anti-Stokes intensities of UVRR bands of the probe Trp residue after photoexcitation of the heme group allow us site-selective detection of the vibrational energy at the level of a single amino acid residue.

In a proof-of-principle report, we have succeeded in direct detection of energy flow into and from a Trp residue located near the heme in cytochrome c by monitoring anti-Stokes Raman intensities of the single intrinsic Trp residue in the protein as a spectroscopic probe of vibrationally excited populations (Fujii et al. 2011). The observation demonstrated that this technique is an optimal tool for elucidation of vibrational energy flow in the protein moiety. We next investigated the temporal behavior of the vibrationally excited populations of the probe Trp residue at the different positions in the protein and carried out temporal and spatial mapping of vibrational energy flow in the protein. The three-dimensional crystal structure of the protein has been refined to high resolution, and thus distance and orientation of the probe amino acid residue against the heme group can be definitely identified. Myoglobin (Mb) is a relatively small protein, whose three-dimensional structure has been determined even for a number of mutants with specific residues replaced by Trp. Combining our spectroscopic technique with site-directed mutagenesis, we are able to map vibrational energy flow in a protein with a spatial resolution at a single amino acid residue. By changing positions of the probe residue along the similar direction from heme by amino acid substitution to Trp, we have explored the distance dependence of the energy flow in Mb (Fujii et al. 2014). It was found that observed temporal evolutions of the anti-Stokes Raman intensities of the probe Trp residues at the different positions were qualitatively consistent with classical thermal diffusion. However, the experimental data do not exactly fit the Boltzmann factor calculated using the classical two-boundary thermal transport model. We have also examine a pathway of the vibrational energy flow in Mb by monitoring temporal evolutions of the anti-Stokes Raman intensities of the Trp residues contacting the heme group (Kondoh et al. 2016; Yamashita et al. 2018). In this short review, we summarize our investigations of the role of atomic contacts in vibrational energy transfer in Mb.

Importance of atomic contacts in vibrational energy flow in Mb

We have constructed an apparatus for observing picosecond time-resolved UVRR spectra to detect ultrafast changes in the protein moiety. Details of our apparatus have been described elsewhere (Mizuno et al. 2007; Mizuno and Mizutani 2015; Mizutani 2017; Sato and Mizutani 2005). For picosecond time-resolved anti-Stokes Raman measurements, a pump pulse at 405 nm was used to photo-excite the heme, and a probe pulse at 230 nm was utilized to monitor UVRR scattering by Trp. The cross-correlation time between the pump and probe pulses was 3.6 ps. The measurements were conducted at room temperature.

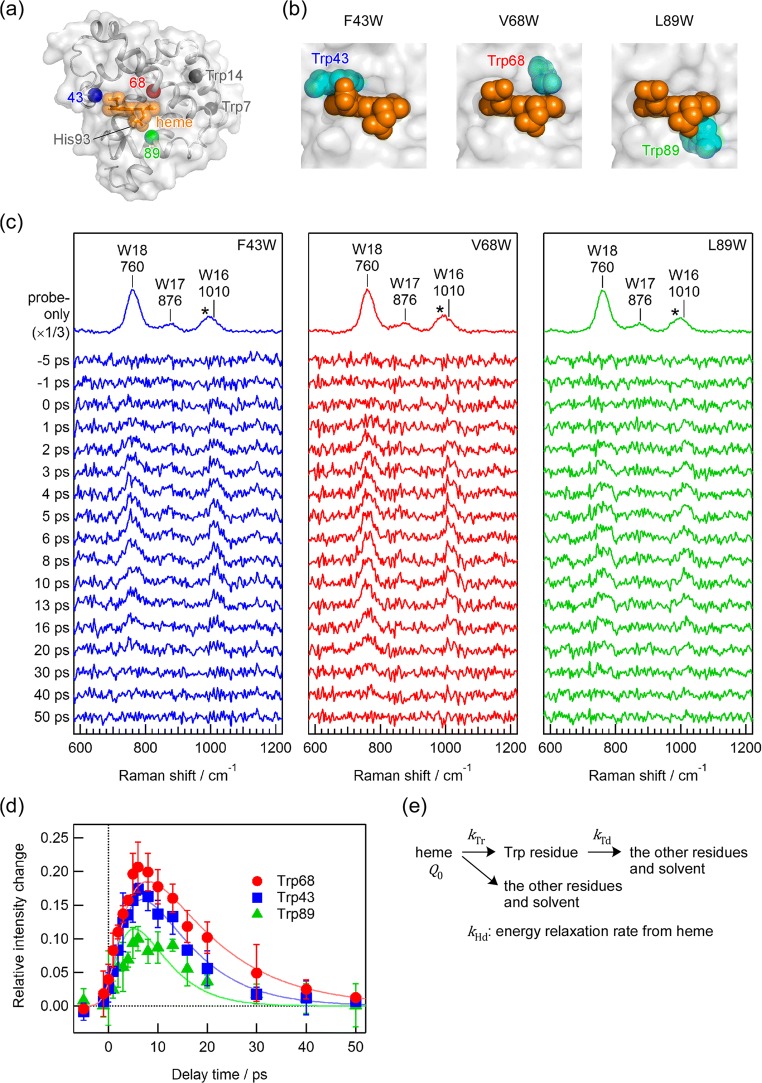

The crystallographic structure of wild-type sperm whale Mb (Kachalova et al. 1999) is shown in Fig. 1a. To investigate energy flow in Mb, we selected three amino acid positions adjacent to the heme group, and prepared three Mb mutants, F43W, V68W, and L89W. Crystallographic structures of the F43W (Watanabe et al. 2007), V68W (Olson et al. 2007), and L89W (Liong et al. 2001) mutants have been determined, which are very close to that of wild-type Mb. Side chains of the Trp43, Trp68, and Trp89 in each Mb mutant directly contact the heme group as shown in Fig. 1b. Based on the coordinate of the iron atom of the heme group and the center of mass including the main chain atoms of each Trp residue, distances from the heme group to Trp43, Trp68, and Trp89 in the mutants are 7.4, 6.4, and 6.4 Å, respectively.

Fig. 1.

a Crystallographic structure of wild-type sperm whale Mb (Protein Data Bank entry 1BZ6). The protein backbone structure is represented as a gray ribbon superimposed with a gray surface. Orange spheres represent atoms in the heme group. Gray spheres are the α-carbons in two intrinsic Trp residues, Trp7 and Trp14. Blue, red, and green spheres indicate α-carbons of amino acid residues at 43, 68, and 89th positions, respectively, each of which was substituted to the probe Trp residue. b Structures around the heme group in the Mb mutants; F43W (left, Protein Data Bank entry 2E2Y), V68W (middle, Protein Data Bank entry 2OH9), and L89W (right, Protein Data Bank entry 1CH3). Orange and cyan spheres of each panel represent the heme group and the probe Trp residue, respectively. c Picosecond time-resolved anti-Stokes UVRR spectra of F43W (left), V68W (middle), and L89W (right), which were obtained using the 405 nm pump and 230 nm probe pulses. In each panel, the top trace is the anti-Stokes UVRR spectrum without pump-pulse irradiation. The other traces are time-resolved difference spectra generated by subtracting the spectrum without pump-pulse irradiation from each time-resolved spectrum. The self-absorption effect was corrected using the intensity of the sulfate ion band at 983 cm−1 indicated as an asterisk. The accumulation time for obtaining each spectrum was 82 min. d Temporal evolutions of photoinduced intensity changes in the anti-Stokes W18 bands for Trp43 (blue squares), Trp68 (red circles), and Trp89 (green triangles). Solid lines are the best fits to the Eq. (1). e Model to analyze the temporal evolutions of anti-Stokes UVRR intensities. (Adapted with permission from Kondoh et al. (2016) J Phys Chem Lett 7:1950–1954, Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society)

Figure 1c depicts picosecond time-resolved anti-Stokes UVRR spectra of the F43W, V68W, and L89W Mb mutants in the ferric form following photoexcitation of heme. The top trace in each panel is an anti-Stokes Raman spectrum for each mutant without pump-pulse irradiation. Anti-Stokes Raman bands at 760, 876, and 1010 cm−1 were observed, which are assigned to the in-phase indole ring breathing (W18), benzene ring deformation and in-plane N − H bending (W17), and out-of-phase indole ring breathing (W16) modes of Trp, respectively, based on the mode assignments reported previously (Harada and Takeuchi 1986). The band intensities of the top trace reflect the thermally equilibrated populations in vibrationally excited states at room temperature. The other traces in each panel of Fig. 1c are time-resolved anti-Stokes UVRR difference spectra obtained by subtracting the spectrum without pump-pulse irradiation from that with pump-pulse irradiation. The intensity correction for the self-absorption effect and drift in laser power was performed using the intensity of the 983 cm−1 band due to sulfate ion marked by asterisks, which is added as an internal intensity standard of the Raman intensity. The band intensities in the three panels have been normalized using the intensity of W18 band in the spectrum without pump-pulse irradiation for each mutant. Positive anti-Stokes UVRR bands for the W18 and W16 modes were observed at positive delay times in the difference spectra of the three mutants.

Observed intensity changes in anti-Stokes bands of the probe Trp residue arise from two possibilities: one is the change in vibrationally excited populations, and the other is the changes in the cross section due to changes in protein structure. We estimated the contribution of the changes in the cross sections by measuring time-resolved Stokes UVRR spectra of the three mutants. It was found that photoinduced intensity changes in the Stokes Raman bands were significantly smaller than those in anti-Stokes bands. This result suggests that the changes observed in the anti-Stokes UVRR intensities are likely due to the energy flow at the probe Trp residue rather than changes in the protein structure.

Wild-type sperm whale Mb possesses two intrinsic Trp residues, Trp7 and Trp14. These residues are also included in the mutants. Distances from heme to Trp7 and Trp14 are 22 and 17 Å, respectively, which are much longer than the distances between heme and the introduced Trp residues. In the spectra for the wild-type Mb, the photoinduced intensity changes were negligibly weak. Therefore, the positive bands in the difference anti-Stokes spectra of the mutants in Fig. 1c are ascribed to the increased vibrationally excited populations in Trp43, Trp68, and Trp89.

To examine the vibrationally excited populations at Trp43, Trp68, and Trp89, we compared temporal evolutions of the W18 band intensity in the time-resolved difference spectra, as shown in Fig. 1d. At the three positions, we observed an increase of the anti-Stokes intensity over 6–8 ps followed by decay within 50 ps. The intensity increase corresponds to the increase of the vibrationally excited populations of the probe Trp residue resulting from the vibrational energy transfer from the photoexcited heme. The observed intensity decay is due to the decrease of the vibrationally excited populations at the probe Trp residue arising from the energy release to the surroundings from the probe Trp residue. The similar temporal behavior indicates that the vibrational energy is transferred with similar rates at the three Trp positions in Mb. Temporal evolutions of anti-Stokes intensities of the W16 band of the three probe Trp residues were similar to those of the W18 band.

The heme group is covalently bound to the polypeptide chain through the proximal His93 residue (Fig. 1a). The distances from heme to Trp43, Trp68, and Trp89 along the main chain are significantly different. The buildup time of the vibrationally excited population depends on the Trp positions in the amino acid sequence if the excess vibrational energy from heme to the probe Trp residues is transferred through the main chain. However, the observed result did not show this. The three Trp residues all contact the heme group. The similar rates of energy transfer from heme to the probe Trp residues as shown in Fig. 1d suggest that the vibrational energy is transferred not through the covalent linkage from heme to the main chain via His93 but through atomic contacts between the heme group and the residues.

The amplitudes of the photoinduced anti-Stokes intensity changes decreased in the order Trp68, Trp43, and Trp89, indicating that the amount of transient vibrational energy at each Trp residue is different. Based on the crystallographic structure of the mutants (Liong et al. 2001; Olson et al. 2007; Watanabe et al. 2007), we discuss the energy flow rate into and out of the probe Trp residues. First, the extent of heme-Trp contacts was estimated to examine energy flow into the Trp residue. The number of atomic contacts between heme and each Trp residue is similar for Trp43 and Trp89, whereas it is smaller for Trp68. We predicted that the larger the extent of the contacts, the faster the rate of energy flow into the probe Trp residue, leading to an increase of the anti-Stokes intensities. The observation was opposite to the prediction. We next investigated the protein environment surrounding each probe Trp residue using the values of the solvent accessible surface area (SASA). Trp68 and Trp43 are located inside the protein, whose SASA values including atoms in the main chain are 2.9 and 5.1 Å2, respectively. In contrast, Trp89 faces solvent water. The SASA value for Trp89 is 12.7 Å2. It is noted that the observed amplitudes of the anti-Stokes intensity changes are inversely correlated with the SASA values. Solvent water is known to be a good acceptor of excess vibrational energy (Gao et al. 2006; Koyama et al. 2006; Park et al. 2009; Sagnella and Straub 2001). The larger the SASA values, the larger the energy dissipation rate from the Trp residue to water, which would decrease the amplitude of the anti-Stokes intensity changes.

A model to reproduce the observed temporal evolutions of the anti-Stokes intensity changes of the probe Trp bands is described in Fig. 1e. We quantitatively analyzed the temporal evolutions of the anti-Stokes intensity changes IaS(t) using a biexponential function as follows:

| 1 |

where Q0 is the amount of initial excess vibrational energy deposited into heme, kHd is the energy relaxation rate of heme, kTr is the energy flow rate from heme into the probe Trp residue, kTd is the energy flow rate out of the Trp residue, and A is a constant. The temporal profiles were reproducible within error range using a minimalist model in which only the parameter kTd was allowed to adopt different values and that the other parameters Q0, kHd, kTr, and A were common. The parameter kHd−1 was calculated to be 4.69 ± 1.0 ps, consistent with the time constant of the vibrational cooling of heme in Mb reported previously (Lim et al. 1996; Mizutani and Kitagawa 1997). The parameter kTd−1 for Trp68 was found to be 13.5 ± 3.0 ps, whereas that for Trp43 was 9.0 ± 1.8 and that for Trp89 was 4.70 ± 0.8 ps. Therefore, the observed difference in the amplitudes of the anti-Stokes intensity changes for the three probe Trp residues could be explained simply by the difference in the rates of energy release from the probe Trp residues. As solvent water acts as the acceptor of the vibrational energy, transient vibrational energy is less populated at the amino acid residue with high accessibility to solvent. We established that atomic contacts play a key role in vibrational energy flow from the heme group to the protein moiety, as well as from an amino acid residue to solvent water.

Channel of vibrational energy flow in Mb

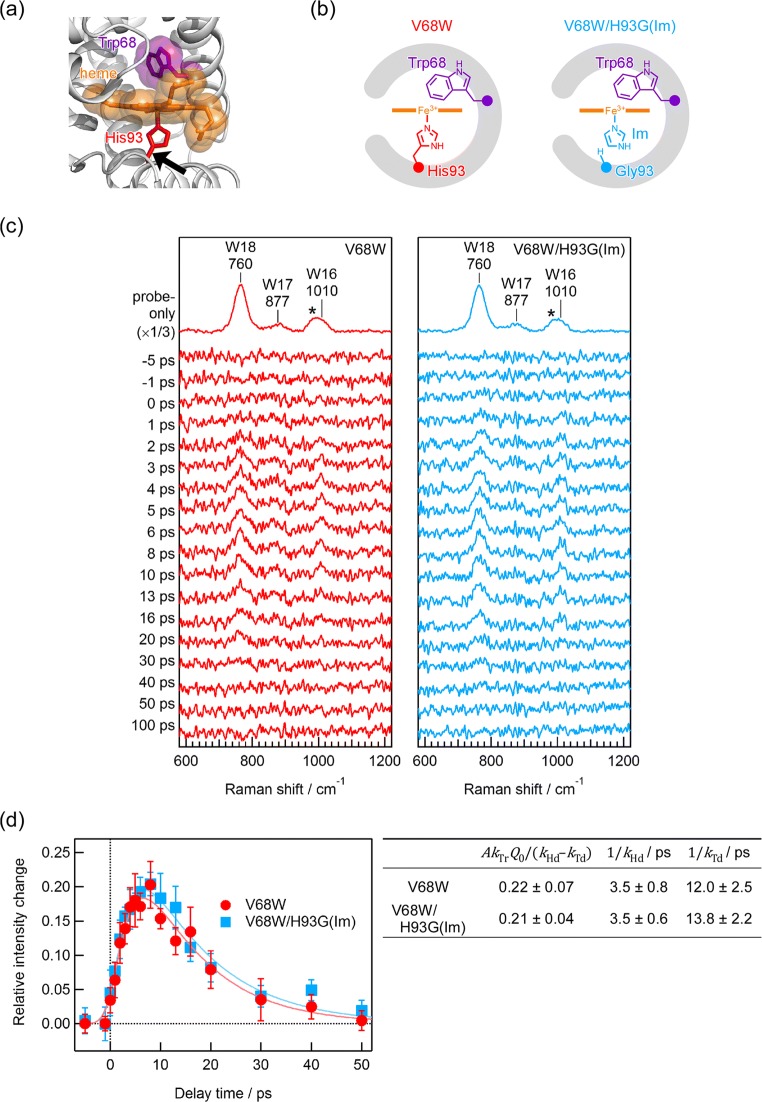

We next examined the contribution of atomic contacts and covalent bonds to the pathway of the vibrational energy transfer by comparing the temporal evolutions of the photoinduced anti-Stokes UVRR intensity changes of the probe Trp68 residue in the proteins with and without the covalent linkage between heme and the protein backbone. In Mb, the heme group is covalently bound to the polypeptide chain through the proximal His93 residue (Fig. 2a). Two protein samples were prepared as shown in Fig. 2b. One is the V68W Mb mutant, in which the covalent bond is intact. The other is the V68W/H93G(Im) mutant. Substitution from His93 to Gly removes the covalent bond between the heme group and the protein, but added imidazole binds to the heme to mimic the side chain of the missing His.

Fig. 2.

a Crystallographic structure of the V68W Mb mutant (Protein Data Bank entry 2OH9). The protein backbone structure is represented as a gray ribbon. The heme group and the side chains of Trp68 and His93 are shown as sticks and translucent spheres colored orange, purple, or red, respectively. A black arrow implies a position to cleave a covalent bond between the heme group and polypeptide chain. b Schematic protein structures of the Mb mutants; V68W (left) and V68W/F93G(Im) (right). For the V68W/F93G(Im) mutant, His93 is replaced by Gly, and imidazole was added to occupy a cavity generated resulting from the amino acid replacement. c Picosecond time-resolved anti-Stokes UVRR spectra of V68W (left) and V68W/F93G(Im) (right), which were obtained using the 405 nm pump and 230 nm probe pulses. In each panel, the top trace is the anti-Stokes UVRR spectrum without pump-pulse irradiation. The other traces are time-resolved difference spectra generated by subtracting the spectrum without pump-pulse irradiation from each time-resolved spectrum. The self-absorption effect was corrected using the intensity of the sulfate ion band at 983 cm−1 indicated as an asterisk. The accumulation time for obtaining each spectrum was 120 min. d Temporal evolutions of photoinduced intensity changes in the anti-Stokes W18 bands of Trp68 for V68W (red circles) and V68W/F93G(Im) (blue squares). Solid lines are the best fits to the Eq. (1). Fitting parameters were also shown in the right panel. (Adapted with permission from Yamashita S, Mizuno M, Tran DP, Dokainish H, Kitao A, Mizutani Y (2018) J Phys Chem B 122:5877–5884, Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society)

Figure 2 c shows picosecond time-resolved anti-Stokes UVRR spectra of the V68W and V68W/H93G(Im) mutants. The top trace in each panel represents the anti-Stokes UVRR spectrum of the two mutants in thermal equilibrium at room temperature. The others are time-resolved difference spectra upon photoexcitation of heme. Positive bands due to the W18, W17, and W16 modes appeared at the positive delay times. Both for the time-resolved spectra, positive anti-Stoke bands are predominantly attributed to the probe Trp68 residue.

We plotted the photoinduced intensity changes in the anti-Stokes W18 bands of the two proteins against the delay times as shown in Fig. 2 d. The temporal evolution was similar in each case. Fitting the data to Eq. (1), we found that obtained fitting parameters kHd, kTd, and AkTrQ0/(kHd − kTd) showed little difference between the two proteins, so the energy flow rates kHd, kTr, and kTd are almost unchanged with and without the covalent linkage from the heme group to the polypeptide chain.

Similar energy flow rates from heme to its surroundings in the two mutants indicate that the covalent linkage between heme and the polypeptide chain via His93 makes little contribution to the energy flow rates in the protein. The excess vibrational energy from heme flows through some other channel. We compared the three-dimensional structures of the protein using molecular dynamics simulations, since there is no crystallographic structure of the V68W/H93G(Im) mutant. The simulation showed that the V68W/H93G(Im) mutant has very similar backbone structure to the V68W mutant, but it possesses two stable forms with different orientations of the imidazole ring ligated to heme. The Trp has a very similar position relative to the heme in both proteins. Accordingly, the van der Waals atomic contacts between heme and its surroundings are dominant channel for the vibrationally energy transfer from heme.

It is known that the NδH group of His93 is hydrogen-bonded to the main chain carbonyl group of Ser92 in Mb (Shiro et al. 1994). In the V68W/H93G(Im) mutant, the ligated imidazole is hydrogen-bonded to Ser92 similarly to His93 with an intact covalent linkage. Although there may be a contribution of the hydrogen bond to the vibrational relaxation of heme, a single hydrogen bond is unlikely to be a dominant channel for vibrational energy from heme to the protein moiety.

In addition, the simulated SASA values of the interior Trp68 residue in the V68W and V68W/H93G(Im) mutants were very similar. The energy transfer rate from the Trp residue is correlated with the SASA value. The average SASA values of Trp68 in the simulation trajectories were similar for both proteins, consistent with the finding that the energy transfer rates were also very close.

Mechanism of energy flow in protein

The packing density inside a native protein is high (Tsai et al. 1999), which led to the hypothesis that covalent and hydrogen bonds as well as nonbonded contacts play key roles in vibrational energy flow in proteins. We experimentally demonstrated that atomic contacts are dominant channel for vibrational energy flow from heme to the nearby amino acid residue, and then from the residue to solvent water as shown schematically in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Schematic drawing of the vibrational energy flow in Mb. Green and blue areas indicate protein structure and water solvent, respectively. Orange, purple, and gray sticks represent the heme group, probe Trp residue, and proximal His residue, respectively. Red arrows display dominant pathways of vibrational energy flow in Mb; energy flow from the heme group to the probe Trp residue and that from the Trp residue to water solvent

The packing density within proteins is not uniform, and there are regions of low density (Enright and Leitner 2005; Liang and Dill 2001). Anisotropy of structural change (Brinkmann and Hub 2016) and energy flow (Fujii et al. 2014) likely result from the inhomogeneity of the packing density inside the protein. The role of packing and nonbonded contacts in energy flow identified by our study would further indicate anisotropic energy flow arising from variation in protein packing.

Energy flow in biomolecules has been studied in numerous systems using a variety of computational approaches to disclose the contributions of the through-bond and through-space transport mechanisms. A nonequilibrium molecular dynamics simulation on postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95) showed that van der Waals interactions are the main component in energy transduction, and electrostatic interactions are much less important (Ota and Agard 2005). The importance of side chain contributions to energy transfer was highlighted by another simulation that showed significant heat transfer between residues within close contacts in the folded structure (Martinez et al. 2011). An energy network analysis of PSD-95 showed energy efficiently migrates not only through covalent bonds but also through neighboring side chains in the folded structure, but the side chain interactions make no contribution to the energy transfer in the unfolded protein (Ribeiro and Ortiz 2015). Stock and coworkers exhibited that the energy flow is correlated with the functionally important long-range interaction in the RNA-aptamer domain of guanine-sensing riboswitch (Nguyen et al. 2009). They also found pathways for energy transport via hydrogen bonds between residues distantly positioned in the sequence of the 35-residue villin headpiece subdomain (Buchenberg et al. 2016; Leitner et al. 2015). Recently, Leitner and coworkers discussed the rates of vibrational energy transfer for short-range polar contacts, such as hydrogen bonds, as well as at interface in biomolecules in the thermal equilibrium (Leitner et al. 2019; Reid et al. 2018). They mentioned that analyzing energy transfer across the van der Waals contact using molecular dynamics simulation is challenging because of the small energy conductivity. Therefore, the results of our study can stimulate further theoretical investigations of the mechanism of vibrational energy flow in proteins. Comprehensive studies both of real-time observations using our UVRR methods and molecular dynamics simulations for vibrational energy flow in various heme proteins will shed light to uncover the microscopic processes of the energy transfer in condensed phases.

Conclusion

Vibrational energy flow in Mb was studied by monitoring the time-resolved anti-Stokes UVRR scattering of a specific Trp residue contacting heme, which can be used as a probe of transient vibrational excited populations in the protein. Our observations established the importance of atomic contacts both between the heme group and amino acid residues and between the residues to solvent water for vibrational energy flow in Mb. Measurements of anti-Stokes UVRR spectra of the Mb samples with and without the covalent linkage between heme and the protein backbone provided direct experimental evidence that the channel through the covalent bond is negligible, and that vibrational energy transfer from heme to adjacent residues occurs through van der Waals contacts. The vibrational energy in the protein is transferred by a process analogous to collisional energy exchange processes in solution. Insights obtained through experimental and theoretical studies on proteins provide a general understanding of vibrational energy transfer in condensed phases.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Masato Kondoh (present at University of Tsukuba) and Mr. Satoshi Yamashita both for preparation and time-resolved anti-Stokes UVRR measurements of the Mb mutants. We also thank Professor Akio Kitao, Dr. Kazuhiro Tekemura, Dr. Duy Phuoc Tran, and Dr. Hisham Dokainish at Tokyo Institute of Technology for providing data of molecular dynamics simulations for the Mb mutants.

Funding information

This work was supported by Morino Foundation for Molecular Science to M.M. and MEXT-KAKENHI grant number JP25104006 and JSPS-KAKENHI grant number JP26288008 to Y.M.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Brinkmann LUL, Hub JS. Ultrafast anisotropic protein quake propagation after CO photodissociation in myoglobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:10565–10570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603539113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchenberg S, Leitner DM, Stock G. Scaling rules for vibrational energy transport in globular proteins. J Phys Chem Lett. 2016;7:25–30. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b02514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion PM, Lange R. On the quantitation of light emission from cytochrome c in the low quantum yield limit. J Chem Phys. 1980;73:5947–5957. doi: 10.1063/1.440153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enright MB, Leitner DM. Mass fractal dimension and the compactness of proteins. Phys Rev E. 2005;71:011912. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.011912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzen S, Bohn B, Poyart C, Martin JL. Evidence for sub-picosecond heme doming in hemoglobin and myoglobin - a time-resolved resonance Raman comparison of carbonmonoxy and deoxy species. Biochemistry. 1995;34:1224–1237. doi: 10.1021/bi00004a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii N, Mizuno M, Mizutani Y. Direct observation of vibrational energy flow in cytochrome c. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:13057–13064. doi: 10.1021/jp207500b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii N, Mizuno M, Ishikawa H, Mizutani Y. Observing vibrational energy flow in a protein with the spatial resolution of a single amino acid residue. J Phys Chem Lett. 2014;5:3269–3273. doi: 10.1021/jz501882h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Koyama M, El-Mashtoly SF, Hayashi T, Harada K, Mizutani Y, Kitagawa T. Time-resolved Raman evidence for energy 'funneling' through propionate side chains in heme 'cooling' upon photolysis of carbonmonoxy myoglobin. Chem Phys Lett. 2006;429:239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2006.07.085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Genberg L, Bao Q, Gracewski S, Miller RJD. Picosecond transient thermal phase grating spectroscopy: a new approach to the study of vibrational energy relaxation processes in proteins. Chem Phys. 1989;131:81–97. doi: 10.1016/0301-0104(89)87082-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harada I, Takeuchi H. Raman and ultraviolet resonance Raman spectra of proteins and related compounds. In: Clark RJH, Hester RE, editors. Spectroscopy of biological systems. Chichester: Wiley; 1986. pp. 113–175. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata Koichi, Hamaguchi Hiro-o. Microscopic Mechanism of Solute−Solvent Energy Dissipation Probed by Picosecond Time-Resolved Raman Spectroscopy. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 1997;101(4):632–637. doi: 10.1021/jp962010l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kachalova GS, Popov AN, Bartunik HD. A steric mechanism for inhibition of CO binding to heme proteins. Science. 1999;284:473–476. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5413.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondoh M, Mizuno M, Mizutani Y. Importance of atomic contacts in vibrational energy flow in proteins. J Phys Chem Lett. 2016;7:1950–1954. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama M, Neya S, Mizutani Y. Role of heme propionates of myoglobin in vibrational energy relaxation. Chem Phys Lett. 2006;430:404–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2006.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner DM, Buchenberg S, Brettel P, Stock G. Vibrational energy flow in the villin headpiece subdomain: master equation simulations. J Chem Phys. 2015;142:075101. doi: 10.1063/1.4907881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner DM, Pandey HD, Reid KM. Energy transport across interfaces in biomolecular systems. J Phys Chem B. 2019;123:9507–9524. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b07086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian T, Locke B, Kholodenko Y, Hochstrasser RM. Energy flow from solute to solvent probed by femtosecond IR spectroscopy: malachite green and heme protein solutions. J Phys Chem. 1994;98:11648–11656. doi: 10.1021/j100096a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Dill KA. Are proteins well-packed? Biophys J. 2001;81:751–766. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(01)75739-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim M, Jackson TA, Anfinrud PA. Femtosecond near-IR absorbance study of photoexcited myoglobin: dynamics of electronic and thermal relaxation. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:12043–12051. doi: 10.1021/jp9536458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liong EC, Dou Y, Scott EE, Olson JS, Phillips GN., Jr Waterproofing the heme pocket. Role of proximal amino acid side chains in preventing hemin loss from myoglobin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9093–9100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008593200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez L, Figueira ACM, Webb P, Polikarpov I, Skaf MS. Mapping the intramolecular vibrational energy flow in proteins reveals functionally important residues. J Phys Chem Lett. 2011;2:2073–2078. doi: 10.1021/jz200830g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno Misao, Mizutani Yasuhisa. ACS Symposium Series. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 2015. Protein Response to Chromophore Isomerization in Microbial Rhodopsins Revealed by Picosecond Time-Resolved Ultraviolet Resonance Raman Spectroscopy: A Review; pp. 329–353. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno M, Hamada N, Tokunaga F, Mizutani Y. Picosecond protein response to the chromophore isomerization of photoactive yellow protein: selective observation of tyrosine and tryptophan residues by time-resolved ultraviolet resonance Raman spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:6293–6296. doi: 10.1021/jp072939d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani Y. Time-resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy and application to studies on ultrafast protein dynamics. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2017;90:1344–1371. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.20170218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani Y, Kitagawa T. Direct observation of cooling of heme upon photodissociation of carbonmonoxy myoglobin. Science. 1997;278:443–446. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani Y, Kitagawa T. A role of solvent in vibrational energy relaxation of metalloporphyrins. J Mol Liq. 2001;90:233–242. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7322(01)00126-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PH, Derreumaux P, Stock G. Energy flow and long-range correlations in guanine-binding riboswitch: a nonequilibrium molecular dynamics study. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:9340–9347. doi: 10.1021/jp902013s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JS, Soman J, Phillips GN., Jr Ligand pathways in myoglobin: a review of Trp cavity mutations. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:552–562. doi: 10.1080/15216540701230495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota N, Agard DA. Intramolecular signaling pathways revealed by modeling anisotropic thermal diffusion. J Mol Biol. 2005;351:345–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S-M, Nguyen PH, Stock G. Molecular dynamics simulation of cooling: heat transfer from a photoexcited peptide to the solvent. J Chem Phys. 2009;131:184503. doi: 10.1063/1.3259971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid KM, Yamato T, Leitner DM. Scaling of rates of vibrational energy transfer in proteins with equilibrium dynamics and entropy. J Phys Chem B. 2018;122:9331–9339. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b07552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro AAST, Ortiz V. Energy propagation and network energetic coupling in proteins. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:1835–1846. doi: 10.1021/jp509906m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagnella DE, Straub JE. Directed energy "funneling" mechanism for heme cooling following ligand photolysis or direct excitation in solvated carbonmonoxy myoglobin. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:7057–7063. doi: 10.1021/jp0107917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, Mizutani Y. Picosecond structural dynamics of myoglobin following photodissociation of carbon monoxide as revealed by ultraviolet time-resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14709–14714. doi: 10.1021/bi051732c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiro Y, Iizuka T, Marubayashi K, Ogura T, Kitagawa T, Balasubramanian S, Boxer SG. Spectroscopic study of ser92 mutants of human myoglobin: hydrogen bonding effect of ser92 to proximal his93 on structure and property of myoglobin. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14986–14992. doi: 10.1021/bi00254a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Taylor R, Chothia C, Gerstein M. The packing density in proteins: standard radii and volumes. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:253–266. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Nakajima H, Ueno T. Reactivities of oxo and peroxo intermediates studied by hemoprotein mutants. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:554–562. doi: 10.1021/ar600046a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita S, Mizuno M, Tran DP, Dokainish H, Kitao A, Mizutani Y. Vibrational energy transfer from heme through atomic contacts in proteins. J Phys Chem B. 2018;122:5877–5884. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b03518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X, et al. Investigations of heme protein absorption line shapes, vibrational relaxation, and resonance Raman scattering on ultrafast time scales. J Phys Chem A. 2003;107:8156–8165. doi: 10.1021/jp0276799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]