Abstract

Urogenital schistosomiasis is a parasitic disease caused by S. haematobium which is endemic in tropical and sub-tropical areas but is increasingly diagnosed in temperate non-endemic countries due to migration and international travels. Early identification and treatment of the disease are fundamental to avoid associated severe sequelae such as bladder carcinoma, hydronephrosis leading to kidney failure and reproductive complications. Radiologic imaging, especially through ultrasound examination, has a fundamental role in the assessment of organ damage and follow-up after treatment. Imaging findings of urinary tract schistosomiasis are observed mainly in the ureters and bladder. The kidneys usually appear normal until a late stage of the disease.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Infection, Bladder, Kidney, Schistosoma

Introduction

Schistosomiasis is a parasitic disease caused by trematodes belonging to the Schistosoma genus. In terms of impact, this parasitic disease is second only to malaria. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that more than 207 million people are affected in the endemic areas, of which 85% live in Africa, and about 200,000 deaths every year are due to this infection and its complications, such as urinary bladder cancer, kidney failure and haematemesis [1]. This condition has been increasingly diagnosed also in non-endemic areas, such as Europe, following the growth of international travels and recent migration flows from Sub-Saharan Africa [2]. The prevalence of the infection in migrants from Sub-Saharan countries is about 20% [2, 3]. Schistosoma infection can result into two main clinical diseases: the urogenital form caused by S. haematobium and the hepato-intestinal one caused by S. mansoni, S. japonicum, S. mekongi, S. intercalatum and S. guineensis [1, 4].

The life cycle of Schistosoma spp. requires snails living in fresh waters in endemic areas acting as intermediate host. Cercariae, the infective stage of the parasite, are released from the intermediate host into fresh water and can penetrate the skin and mucous membrane of humans bathing in infested waters. After skin penetration, the cercariae become schistosomulae, which migrate through several tissues and stages to their residence in the veins. According to the Schistosoma species, adult worms dwell in the venous plexus of the bladder or rectal venules (S. haematobium) or in the superior mesenteric veins (other species). Adult worms can live for several years, producing eggs, which are released in the small venules and move progressively towards the lumen of the bladder and ureters (S. haematobium) or intestine (other species) and are finally eliminated with urine or faeces, respectively. The life cycle is completed if the human urine or faeces containing the eggs reach a lake or a river infested by the intermediate host. The eggs hatch in the water and release miracidia, which is the infective stage for the snails.

Clinical manifestations in the early stage can be related to dermatitis caused by larvae penetration of the skin. Dermatitis may be followed by bronchopulmonary and gastrointestinal manifestations associated with weight loss, eosinophilia and fever (Katayama disease). Chronic manifestations of the infection are caused by the diffuse granulomatous immune response induced by the eggs, which remain in part trapped in the urogenital and hepato-intestinal tissues. In urogenital schistosomiasis, on which this article is focused, frequent symptoms are dysuria, suprapubic pain, haematuria, and haemospermia (lower urinary tract symptoms or LUTS) mimicking cystitis or prostatitis. Usually, macroscopic haematuria is the first sign that shows about 3 months after infection and may persist for years. Of note, clinical genitourinary symptoms may be absent for years [1–4]. The infection can also have a retrograde diffusion, causing urethral dysfunction, dilatation and fibrosis that can favour the formation of urinary calculi [5–10]. The infection can also spread to the genital tract, which can lead to infertility and promote other sexually transmitted infections [11]. The diagnosis can be confirmed through the demonstration of the eggs in the urine [12]. Treatment of urogenital schistosomiasis is based on the use of praziquantel, which may be able to reverse, completely or partially, urogenital lesions within 3 to 6 months [13–15].

Ultrasound findings

The use of ultrasound (US) examination in the diagnosis of Schistosoma infection is accepted worldwide [13, 16, 17]. US exam plays a central role in the diagnosis and follow-up of this infection and its complications, allowing to assess the presence and degree of organ involvement. Considering that schistosomiasis can also be completely asymptomatic in the advanced stage, US can be the first finding revealing the diagnosis [15, 18]. US-detectable alterations have been seen in about 34% and 83% of asymptomatic and symptomatic Sub-Saharan migrants with urogenital schistosomiasis, respectively [14]. In 1996, the use of US in schistosomiasis was standardized by a group of experts convened by the WHO to enable the comparison of data obtained in different endemic foci. The standardized protocol, called Niamey protocol, provides scores for urogenital and hepato-intestinal schistosomiasis, indicating the degree of organ damage in affected subjects. The global S. haematobium score, developed for urogenital schistosomiasis, is given by the sum of two intermediate scores: the ‘urinary bladder intermediate score’ (which measures the irregularity of the bladder wall, the parietal thickening, the presence of masses or pseudo-polypoid formations and the distortion of the bladder form) and the ‘upper urinary tract intermediate score’ (which evaluates the ureteral and pelvic dilation) (Table 1) [17]. Niamey protocol has been largely used in endemic areas to map the impact of schistosomiasis and monitor the effectiveness of mass antiparasitic treatment and also, in a less extent, in non-endemic areas in the setting of travel and migration medicine. Some authors have proposed some modifications to make it simpler: for example, Akpata et al. underlined the various errors that can lead to an underestimation/non-diagnosis (such as insufficient bladder filling or, on the contrary, a lack of emptying before analysing the dilatation of the upper tract), which suggests a simplification of the protocol to be used easily also by non-radiologists [16, 18–20]. This protocol allows an optimal US evaluation of vesicoureteral disease in point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) assessment [19, 20]. This is not completely valid for the assessment of renal disease, as explained below. Even though the Niamey protocol has several limitations and has not been developed for use in a non-endemic setting, it can be used for a systematic evaluation of patients with suspected or confirmed schistosomiasis, allowing a quantitative assessment of the severity of organ damage and measurement of the effect of treatment during follow-up and reducing inter-observer variability.

Table 1.

Practical scheme of Niamey protocol [17]

| Urinary bladder | |

| Shape | |

| Normal | 0 |

| Round | 1 |

| Bladder wall | |

| Wall irregularity | |

| Absent | 0 |

| Focal | 1 |

| Multifocal | 2 |

| Wall thickening (< 5 mm) | |

| Absent | 0 |

| Focal | 1 |

| Multifocal | 2 |

| Mass (> 10 mm) | |

| Absent | 0 |

| Single | 2 |

| Multiple | Number of masses (= n) + 2 |

| Pseudopolyp | |

| Absent | 0 |

| Single | 2 |

| Multiple | Number of pseudopolyp (= n) + 2 |

| Urinary bladder Intermediate Score | |

| 0–1 | Schistosomiasis unlikely |

| = 2 | Schistosomiasis likely |

| ≥ 3 | Schistosomiasis very likely |

| Ureters | |

| Right ureter | |

| Not visualized | 0 |

| Dilated/visualized at proximal or distal third | 3 |

| Grossly dilated/entirely visualized | 4 |

| Left ureter | |

| Not visualized | 0 |

| Dilated/visualized at proximal or distal third | 3 |

| Grossly dilated/entirely visualized | 4 |

| Renal pelvis | |

| Right pelvis | |

| Not dilated/fissure < 1 cm | 0 |

| Moderately dilated with conserved parenchyma | 6 |

| Marked hydronephrosis with compressed parenchyma | 8 |

| Left pelvis | |

| Not dilated/fissure < 1 cm | 0 |

| Moderately dilated with conserved parenchyma | 6 |

| Marked hydronephrosis with compressed parenchyma | 8 |

Bladder

The pathogenesis of alterations in the bladder is due to the granulomatous inflammatory reaction triggered by the deposition of the S. haematobium eggs. The inflammatory area generally begins at the submucosal level of the bladder base, which leads to haematuria. Chronic inflammation of the urothelium leads to the formation of pseudopolyps, calcifications, bladder ulcers and fibrosis that are essential steps for squamous metaplasia or leucoplakia, which leads to high risk of squamous cell carcinoma [21]. In the advanced stage, there is also an alteration in bladder continence as intramural fibrosis and destruction of muscle groups lead to contraction of the bladder neck with failure to release the detrusor, causing vesicoureteral reflux, hydronephrosis and renal failure [8]. The role of US is undoubtedly in detecting early bladder alterations, such as the increase in parietal thickness and the formation of endoluminal protrusions (in particular, trigone hypertrophy) which create an exophytic mass between the two orifices, even if these findings are then analysed by cystoscopy with a possible biopsy intervention (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) [7]. The Niamey protocol also provides a quantization of the post-voiding residue, although multiple studies have confirmed that the sense of incomplete emptying is a better indicator of the presence of schistosome infection compared with the residue [13–15, 18–21]. The calcification of the bladder wall is classically compared with the ‘foetal head in the pelvis’, which is actually better appreciated using radiological images and particularly computed tomography (CT) (Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9). The presence of hyperechoic areas within the bladder wall may suspect the presence of tiny calcifications, which have to be confirmed with CT. In fact, CT is clearly superior in detecting calcifications and the extent of the disease, even if it is usually needed only in a minority of very complicated cases (which may require surgical procedure). It also has to be remembered that Schistosoma infection increases the risk for a possible development of squamous cell carcinoma [7]. Therefore, it is fundamental to implement the diagnosis and follow-up with diagnostic imaging because it has been estimated that squamous cell carcinoma is responsible for almost half of bladder cancers in endemic countries [21]. The US and CT aspects of the tumour are often unspecific; especially when there is a parietal thickness, a nodule, or an endoluminal protrusion that does not regress after more than 6 months of praziquantel therapy, an expansive lesion is suspected. In this case, cystoscopy with histological analysis is mandatory [18]. An interesting aspect highlighted by Yosry et al. is the difference in the presentation of bladder carcinomas in patients with Schistosoma infection compared with those who are not affected; they never affect the bladder trine probably because of the lack of tissue in the submucosa where eggs can be laid [22]. Generally, carcinomas are single nodular masses of low grade, without the involvement of locoregional lymph nodes or distant metastases, while the ulcerative and papillary lesions are less frequent [7].

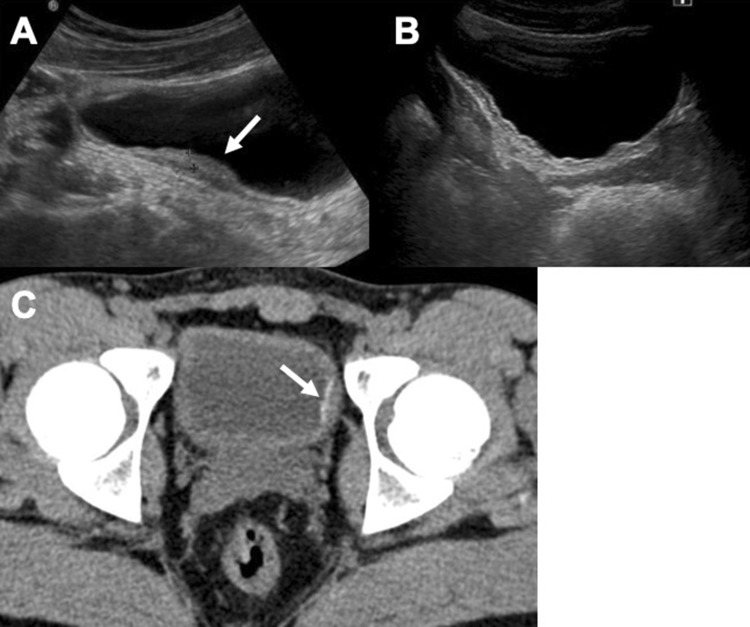

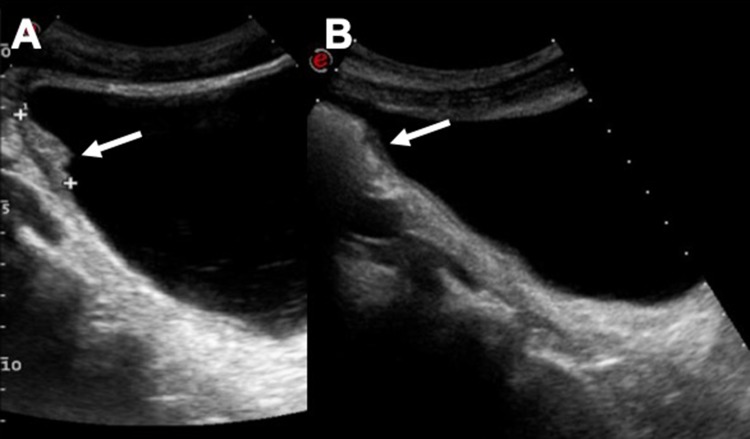

Fig. 1.

Vesical parietal thickening (arrow—a) and follow-up US control after 1 month of therapy (b). Image C shows a CT control after therapy. A small tiny calcification of the left bladder wall is still perceptible (arrow)

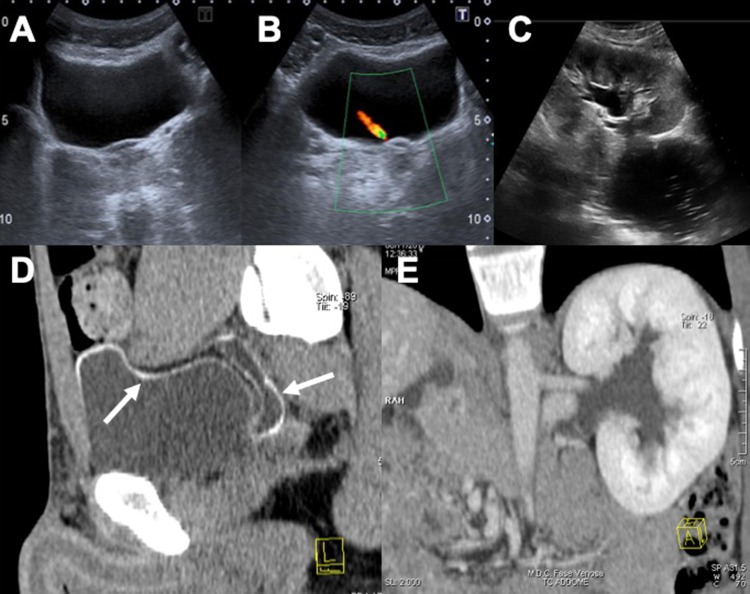

Fig. 2.

US scans in a, b show a focal nodular thickening of the bladder in a young Sub-Saharan man with haematuria (arrows). US follow-up after 3 months (c) and 5 months of therapy

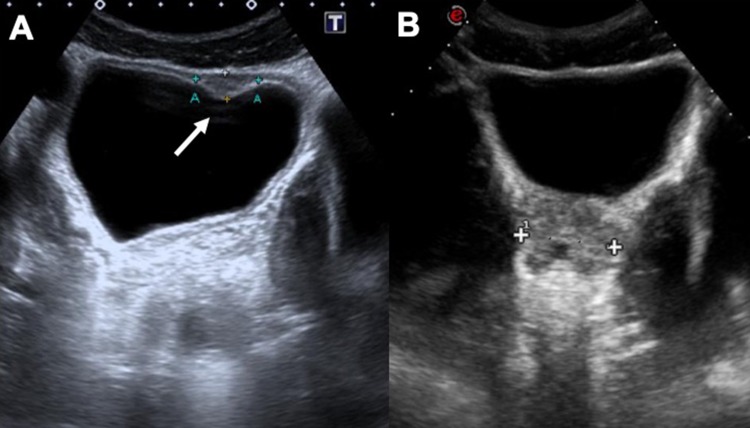

Fig. 3.

Ultrasound suprapubic examination of a young man from Africa shows a nodular thickening of the bladder (arrow—a). The US follow-up control after 14 months does not show any parietal alteration (b)

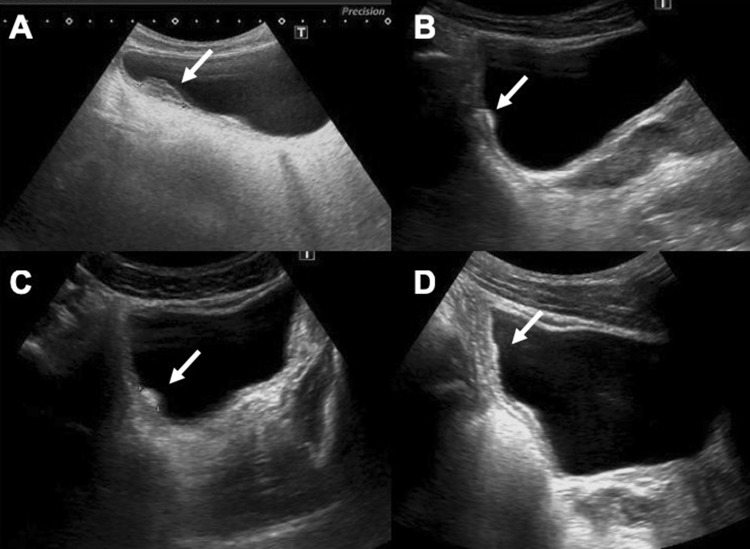

Fig. 4.

Trilaminar aspect of the bladder walls (arrows, axial scan a; sagittal scan b) which remains even after vesical emptying (c, d)

Fig. 5.

Vesical parietal thickening (arrow—a) and follow-up US control after 4 months of therapy (b)

Fig. 6.

US and CT study of the bladder in a 24-year-old male from Senegal: the CT axial image demonstrates better the thin wall calcifications (arrows—a and b). CT follow-up after 20 months revealed a minimal increase in the thickness of parietal calcifications (c)

Fig. 7.

US images in a, b show a mild hyperechogenicity of the bladder wall associated with stages 1–2 hydronephrosis (c). CT sagittal reconstruction (d) demonstrates the bladder wall calcifications that extend also to the dilated ureter (arrow). Figure e is a para-coronal CT reconstruction that confirms the hydronephrosis

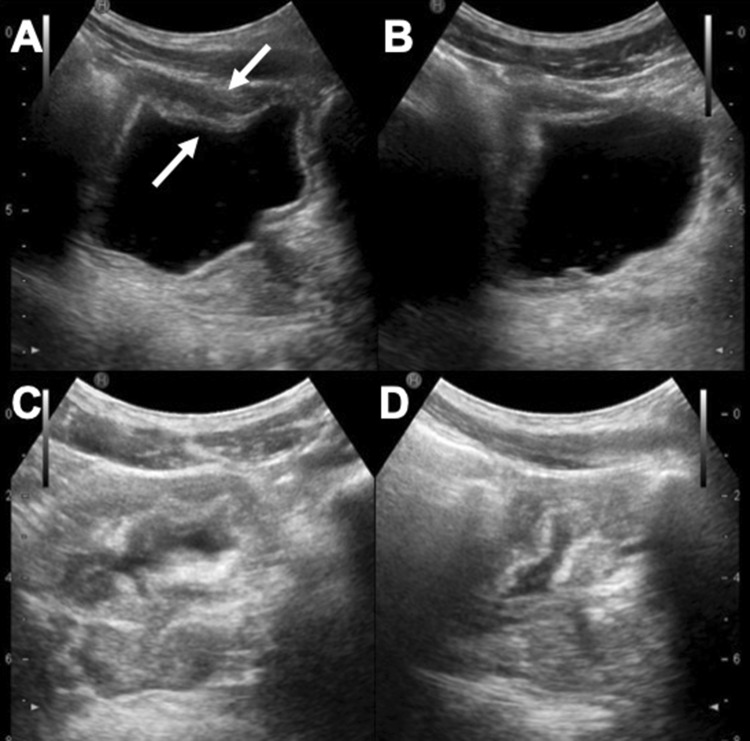

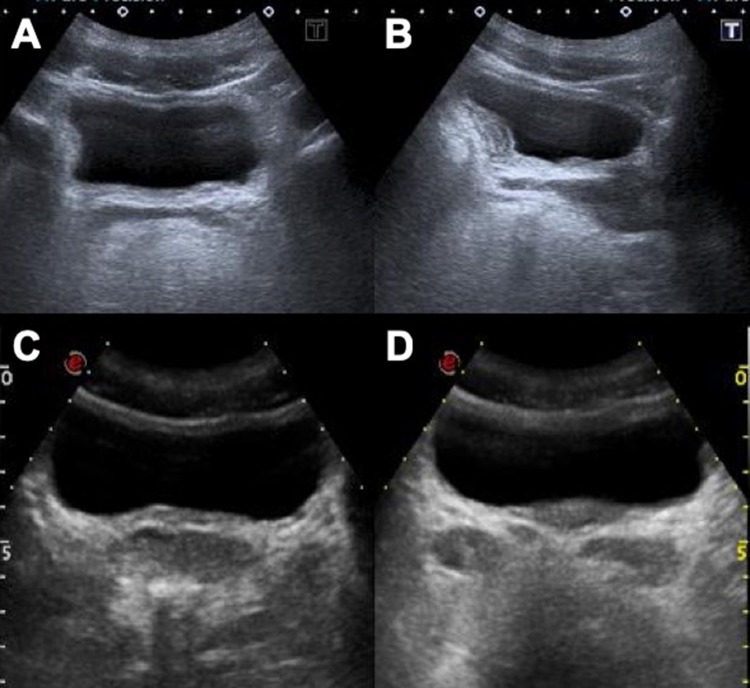

Fig. 8.

Diffuse parietal thickening of the bladder in a young Sub-Saharan man before (a, b) and after 14 months of treatment (c, d)

Fig. 9.

US scan in a shows a diffused hyperechogenicity of the bladder wall’s submucosa, confirmed in the CT study (b, c). Axial CT scan highlights also an early hydronephrosis with two big calculi

Ureter

The ureter is involved in more than 65% of cases. Usually, the initial alteration is a dilatation caused by ureteral dysfunction and not by direct tissue damage, and it is generally unilateral. In the more advanced stage, there is ureteral fibrosis and parietal calcification with gradual luminal stenosis (Fig. 7) [7]. Usually, fibrosis starts from the intravesical segment of the ureter or 1–2 cm above the orifice in 80% of cases. The fibrotic alterations increase to affect the entire ureter up to the kidney [7, 21–23]. With US, the dilation is easily identified (distal or proximal), and it is possible to estimate the severity of organ damage. Even the ureter may be affected by the deposition of fine calcifications, initially sporadic, which can then coalesce, giving a pathognomonic pattern with parallel linear images and circular patterns on axial CT images [7]. Vesicoureteral reflux is an early complication of schistosomiasis caused by oedema of the bladder mucosa. Other complications, such as cystic urethritis and cystic pyelitis, cause visible air bubble-like filling defects in the ureter and renal pelvis that are easily identified with CT. These signs, connected with a significative clinic, are highly suggestive for Schistosoma infection [7, 19–23]. The renal pelvis is involved in the late stage, and Niamey protocol gives information (such as the diameters of the pelvis) that is not helpful in demonstrating the real damage and loss of function of the kidney, as explained below.

Kidney

The Niamey protocol cannot be applied for the evaluation of renal parenchyma, which is sporadically affected or otherwise completely normal also in the advanced stage of the disease. Its deterioration appears to be because of the progressive and chronic obstruction of the lower urinary tract and vesicoureteral reflux (Fig. 10). However, different types of glomerulonephritis have been described in Schistosoma infection as a consequence of immune complexes containing worms’ antigens deposited in the glomeruli. Also, amyloidosis may occur in prolonged infection [7, 24]. They cannot be recognized by US, and even if they are completely non-specific, they are better identified, especially with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Despite these imaging methods, the diagnosis is based on renal biopsy [19, 24, 25]. The parenchymal alterations, which demonstrate the real damage of the organ, are the assessment of cortical thickness, the corticalization of renal calyces and the presence of focal parenchymal damage [7].

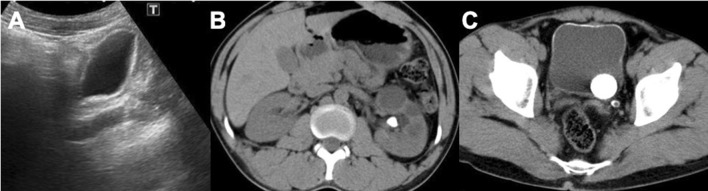

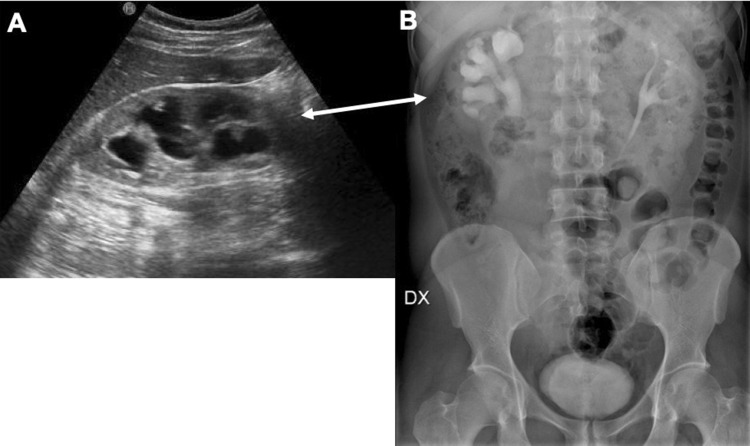

Fig. 10.

US imaging (a) shows stage 2 hydronephrosis of the right kidney, confirmed also with urography (b) in a young male patient from Africa

Genitals

From a recent review, it has emerged that male genital organs are already involved in the early stage of the infection in 58% of patients [26, 27]. The most common involvement is chronic prostatitis, which can lead to fibrosis and calcification of the gland (Fig. 11). There may also be involvement of the seminal vesicles with haemospermia, qualitative changes in the ejaculation, dilatation of the ejaculatory ducts caused by distal fibrosis and hydrocele [27, 28]. At initial US evaluation with a suprapubic and transrectal approach, it is possible to demonstrate prostate alterations with calcified hyperechoic areas, dilatation and thinning of the seminal vesicles’ walls (Figs. 12, 13, 14). The testicles’ involvement can also be easily identified with oedema and parenchymal alterations that can mimic a tumour as a heterogeneous hypoechoic mass with increased vascularization at colour Doppler examination, as described by Soans et al. [29]. MRI can better characterize these findings, although the prostate can be completely normal. There might be pseudonodular deformations in the peripheral zone which can mimic carcinoma. In their work, Soans et al. described a hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images in the seminal vesicles as a demonstration of dilations, cystic formations and haemorrhages with the surrounding inflammatory tissue [29].

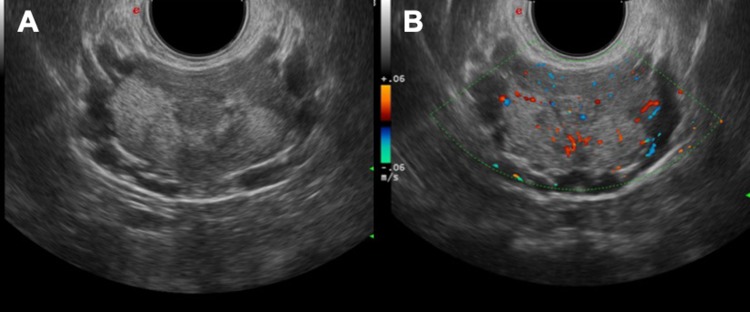

Fig. 11.

US study with transrectal approach demonstrates inflammatory areas (a) with hypervascularisation of the prostate gland (b)

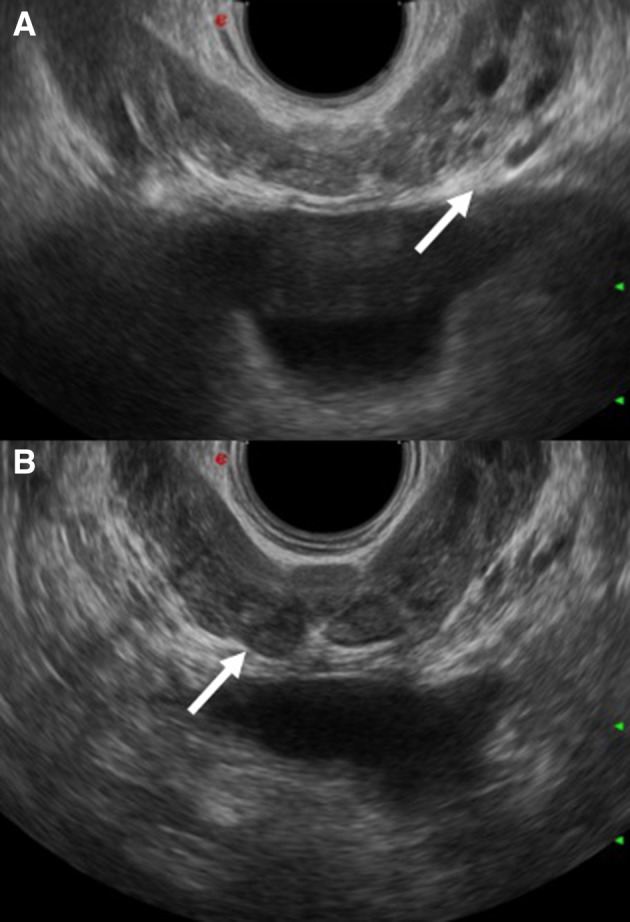

Fig. 12.

Examples of prostate parenchymal calcifications (a), granulomatous flogosis (b) and pseudonodular inflammation of the gland (c) due to Schistosoma infection

Fig. 13.

a and b show ectasia of the seminal vesicles in two male patients affected by chronic schistosomiasis (arrows)

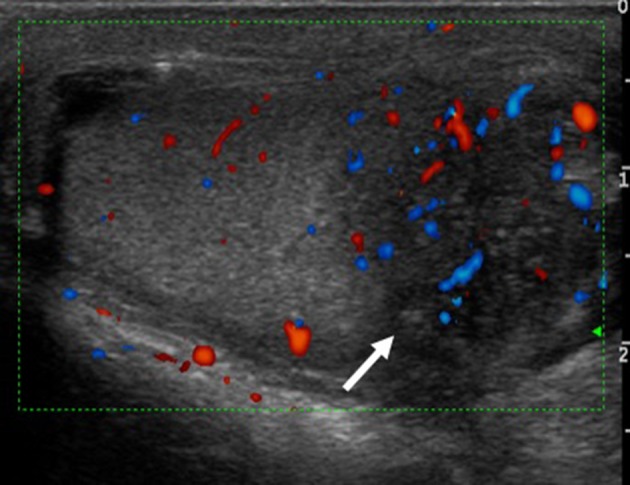

Fig. 14.

Chronic epididymitis in a young male patient: the arrow shows a mild increase in vascularization at the Doppler study. This finding is non-specific but falls within the possible manifestations of genitourinary schistosomiasis

Female genital involvement is less frequent, but sometimes there are hypertrophic/ulcerative lesions in the vagina or cervical uterus. These alterations can be completely non-specific and, therefore, can be mistaken for other manifestations of sexually transmitted diseases [30]. Rarely, there is involvement of the uterus, tube and ovary, with some repercussions at the reproductive level. In various studies, there is growth retardation in children born by untreated mothers. However, specific abnormalities caused by Schistosoma infection have not been highlighted yet [10]. It is clear, however, that gynaecological and foetal US examinations have a key role in identifying complications at this level [31, 32].

All these rare alterations can mimic other diseases, in particular genitourinary tuberculosis [16]. Using US examination, it is possible to demonstrate that the involvement of the upper urinary tract is due to the bladder’s alterations in Schistosoma infection. However, in tuberculosis, the renal papillae are already affected in the initial stages (visible with hypoechoic alteration). In this case, only bacteriological, parasitological and serological examinations allow an accurate differential diagnosis [16].

It is known that the extension of the infection to the genital apparatus is a condition that facilitates superinfection, with a high risk of HIV transmission. In fact, urogenital Schistosoma infection is endemic in the same areas where there is a higher prevalence of human immunodeficiency probably because of the fact that Schistosoma facilitates viral replication. Early identification and treatment of the disease are fundamental to prevent other infections, multi-infective sequelae and later reproductive complications [7].

Conclusion

Schistosomiasis is a parasitic disease with various manifestations, especially in the genitourinary tract. US plays a central role in the evaluation of patients (usually migrants or travellers) with schistosomiasis even in non-endemic countries to evaluate the presence and severity of organ involvement and to assess the response to treatment.

US helps the radiologist and urologist in identifying bladder lesions that are not responsive to therapy to direct the patient to a targeted cystoscopy. Therefore, US examination is a valid diagnostic tool, and it has to be used in endemic (and non-endemic) countries when there is a clinical epidemiological suspicion of Schistosoma infection. Niamey protocol can still be used for a systematic evaluation of patients with suspected or confirmed schistosomiasis, allowing a quantitative assessment of the severity of organ damage and measurement of the effect of treatment during follow-up and reducing inter-observer variability.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Diletta Cozzi, Email: dilettacozzi@gmail.com.

Elena Bertelli, Email: elena.bertelli3@gmail.com.

Elena Savi, Email: elena.savi121@gmail.com.

Silvia Verna, Email: silvia.verna90@gmail.com.

Lorenzo Zammarchi, Email: lorenzo.zammarchi@unifi.it.

Marta Tilli, Email: marta.tilli@hotmail.it.

Francesca Rinaldi, Email: francescarinaldi16@yahoo.it.

Silvia Pradella, Email: pradella3@yahoo.it.

Simone Agostini, Email: agostinis@aou-careggi.toscana.it.

Vittorio Miele, Email: vmiele@sirm.org.

References

- 1.Colley DG, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, King CH. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2014;383:2253–2264. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61949-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lingscheid T, Kurth F, Clerinx J, Marocco S, Trevino B, Schunk M, et al. Schistosomiasis in European travelers and migrants: analysis of 14 years TropNet Surveillance data. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(2):567–574. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chitsulo L, Engels D, Montresor A, Savioli L. The global status of schistosomiasis and its control. Acta Trop. 2000;77(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(00)00122-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buonfrate D, Gobbi F, Marchese V, Postiglione C, Badona-Monteiro G, Giorli G, et al. Extended screening for infectious diseases among newly-arrived asylum seekers from Africa and Asia, Verona province, Italy, April 2014 to June 2015. Eurosurveill. 2018 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.16.17-00527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scarlata F, Giordano S, Romani A, Marasa L, Lipani G, Infurnari L, Titone L. Urinary schistosomiasis: remarks on a case. Infez Med. 2005;13(4):259–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barsoum RS. Schistosomiasis and the kidney. Semin Nephrol. 2003;23:34–41. doi: 10.1053/snep.2003.50003a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shebel HM, Elsayes KM, Abou El Atta HM, Elguindy YM, El-Diasty TA. Genitourinary schistosomiasis: life cycle and radiologic-pathologic findings. Radiographics. 2012;32(4):1031–1046. doi: 10.1148/rg.324115162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu GY, Halim MH. Schistosomiasis: progress and problems. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6(1):12–19. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corachan M. Schistosomiasis and international travel. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(4):446–450. doi: 10.1086/341895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martínez S, Restrepo CS, Carrillo JA, et al. Thoracic manifestations of tropical parasitic infections: a pictorial review. Radiographics. 2005;25(1):135–155. doi: 10.1148/rg.251045043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poggensee G, Feldmeier H. Female genital schistosomiasis: facts and hypotheses. Acta Trop. 2001;79(3):193–210. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(01)00086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bichler KH, Savatovsky I, Naber KG, Bischop MC, Bjerklund-Johansen TE, Botto H, et al. EAU guidelines for the management of urogenital schistosomiasis. Eur Urol. 2006;49(6):998–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richter J, Botelho MC, Holtfreter MC, Akpata R, El Scheich T, Neumayr A, et al. Ultrasoundassessment of schistosomiasis. Z Gastroenterol. 2016;54(7):653–660. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-107359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yong MK, Beckett CL, Leder K, Biggs BA, Torresi J, O’Brien DP. Long-term follow-up of schistosomiasis serology post-treatment in Australian travelers and immigrants. J Trav Med. 2010;17(2):89–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tilli M, Gobbi F, Rinaldi F, Testa J, Caligaris S, Magro P, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of urogenital schistosomiasis in Italy in a retrospective cohort of immigrants from South-Saharan Africa. Infection. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s15010-019-01270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akpata R, Neumayr A, Holtfreter MC, Krantz I, Singh DD, Mota R, et al. The WHO ultrasonography protocol for assessing morbidity due to Schistosoma haematobium. Acceptance and evolution over 14 years. Syst Rev Parasitol Res. 2015;114(4):1279–1289. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4389-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richter J (2000) Ultrasound in Schistosomiasis. A practical guide to the standardized use of ultrasonography for the assessment of schistosomiasis-related morbidity. In: Second international workshop, October 22–26 1996, Niamey, Niger. Revised and updated. Geneva: World Health Organization

- 18.Barda B, Coulibaly JT, Hatz C, Keiser J. Ultrasonographic evaluation of urinary tract morbidity in school-aged and preschool-aged children infected with Schistosoma haematobium and its evolution after praziquantel treatment: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(2):e0005400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King CL, Malhotra I, Mungai P, Wamachi A, Kioko J, Muchiri E, Ouma JH. Schistosoma haematobium-induced urinary tract morbidity correlated with increased tumor necrosis factor -alpha and diminished interleukin-10 production. J Infect Dis. 2001;184(9):1176–1182. doi: 10.1086/323802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wamachi AN, Mayadev JS, Mungai PL, Magak PL, Ouma JH, Magambo JK, et al. Increased ratio of tumor necrosis factor-alpha to interleukin-10 production is associated with Schistosoma haematobium-induced urinary-tract morbidity. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(11):2020–2030. doi: 10.1086/425579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalaf I, Shokeir A, Shalaby M. Urologic complications of genitourinary schistosomiasis. World J Urol. 2012;30(1):31–38. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0751-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yosry A. Schistosomiasis and neoplasia. Contrib Microbiol. 2006;13:81–100. doi: 10.1159/000092967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe K, Muhoho ND, Mutua WR, Kiliku FM, Awazawa T, Moji K, Aoki Y. Assessment of voiding function in inhabitants infected with Schistosoma haematobium. J Trop Pediatr. 2011;57(4):263–268. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmq027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duarte DB, Vanderlei LA, de Azevedo Bispo RK, Pinheiro ME, da Silva Junior GB, De Francesco Daher EF. Acute kidney injury in Schistosomiasis: a retrospective cohort of 60 patients in Brazil. J Parasitol. 2014;101:244–247. doi: 10.1645/13-361.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross AG, Bartley PB, Sleigh AC, Olds GR, Li Y, Williams GM, et al. Schistosomiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(16):1212–1220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vilana R, Corachàn M, Gascòn J, Valls E, Bru C. Schistosomiasis of the male genital tract: transrectal sonographic findings. J Urol. 1997;158(4):1491–1493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kayuni S, Lampiao F, Makaula P, Juziwelo L, Lacourse EJ, Reinhard-Rupp J, et al. A systematic review with epidemiological update of male genital schistosomiasis (MGS): a call for integrated case across the health system in sub-Saharan Africa. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2018;23(4):e00077. doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2018.e00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murdoch DR. Hematospermia due to schistosome infection in travelers. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(8):1086. doi: 10.1086/374246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soans B, Abel C. Ultrasound appearance of schistosomiasis of the testis. Australas Radiol. 1999;43(3):385–387. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1673.1999.433685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldsmith PC, Leslie TA, Sams V, Bryceson AD, Allason-Jones E, Dowd PM. Lesions of the schistosomiasis mimicking warts on the vulva. BMJ. 1993;307:556–557. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6903.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimberly HH, Murray A, Mennicke M, Liteplo A, Lew J, Bohan JS, et al. Focused maternal ultrasound by midwives in rural Zambia. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010;36:1267–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ben-Chetrit E, Lachish T, Mørch K, Atias D, Maguire C, Schwartz E. Schistosomiasis in pregnant travelers: a case series. J Travel Med. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jtm.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]