Abstract

Salmonella enterica is the leading foodborne pathogen associated with outbreaks involving low-moisture foods (LMFs). However, the genes involved in Salmonella’s long-term survival on LMFs remain poorly characterized. In this study, in-shell pistachios were inoculated with Tn5-based mutant libraries of S. Enteritidis P125109, S. Typhimurium 14028s, and S. Newport C4.2 at approximate 108 CFU/g and stored at 25°C. Transposon sequencing analysis (Tn-seq) was then employed to determine the relative abundance of each Tn5 insertion site immediately after inoculation (T0), after drying (T1), and at 120 days (T120). In S. Enteritidis, S. Typhimurium, and S. Newport mutant libraries, the relative abundance of 51, 80, and 101 Tn5 insertion sites, respectively, was significantly lower at T1 compared to T0, while in libraries of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium the relative abundance of 42 and 68 Tn5 insertion sites, respectively, was significantly lower at T120 compared to T1. Tn5 insertion sites with reduced relative abundance in this competition assay were localized in DNA repair, lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis and stringent response genes. Twelve genes among those under strong negative selection in the competition assay were selected for further study. Whole gene deletion mutants in ten of these genes, sspA, barA, uvrB, damX, rfbD, uvrY, lrhA, yifE, rbsR, and ompR, were impaired for individual survival on pistachios. The findings highlight the value of combined mutagenesis and sequencing to identify novel genes important for the survival of Salmonella in low-moisture foods.

Keywords: Salmonella, mutants, survival, low-moisture foods, desiccation, transposon-sequencing

Introduction

Low-moisture foods (LMFs) have low water activity (Aw), generally below 0.6, and thus are not conducive to microbial growth (Beuchat et al., 2013). However, the ability of certain foodborne pathogens to persist on LMFs for long periods has rendered these commodities important vehicles for outbreaks of foodborne illness (Beuchat et al., 2013; Finn et al., 2013a). LMFs have been associated with numerous outbreaks, having led to 7,315 cases of foodborne illnesses and 63 deaths worldwide between 2007 and 2012 (Farakos and Frank, 2014). In the United States, an estimated 83% of LMF-associated multistate foodborne outbreaks between 2007 and 2018 have involved Salmonella (Centers for Disease Control Prevention [CDC], 2019). Examples of extensively investigated foodborne salmonellosis outbreaks involving LMFs include the 2008–2009 peanut butter outbreak that resulted in 714 cases, 171 hospitalizations and 9 deaths (Centers for Disease Control Prevention [CDC], 2009), and a pistachio-associated salmonellosis outbreak in 2016 (Centers for Disease Control Prevention [CDC], 2016).

The food safety concerns of Salmonella-contaminated LMFs are accentuated by the fact that most LMFs are considered ready-to-eat foods and have a relatively long shelf life. Moreover, Salmonella contaminating LMFs exhibits unusually high tolerance to other stressors including heat and exposure to bile salts and sanitizers (Gruzdev et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2016). Thus, preventive control and inactivation strategies that may be effective against Salmonella contaminating high-moisture foods may be less effective on LMFs. Furthermore, salmonellosis outbreaks associated with LMFs can span several months because Salmonella can survive and remain infectious on LMFs for long periods of time (Isaacs et al., 2005; Centers for Disease Control Prevention [CDC], 2009). Indeed, several studies have demonstrated Salmonella’s capacity to persist in the absence of growth on a diverse array of LMFs (Kimber et al., 2012; Beuchat and Mann, 2014; Hokunan et al., 2016). However, the molecular mechanisms and genetic determinants mediating long-term survival of Salmonella on LMFs are still poorly understood.

Findings from previous studies have suggested that the immediate response of Salmonella to desiccation involves accumulation of compatible solutes such as glycine betaine and trehalose (Csonka and Hanson, 1991; Li et al., 2012; Finn et al., 2013a). Transcriptome analyses of Salmonella under desiccation on abiotic surfaces suggested that long-term survival involved complex metabolic and cellular processes (Gruzdev et al., 2012a; Li et al., 2012; Finn et al., 2013b; Maserati et al., 2017). Processes and traits found to be upregulated under desiccation included potassium influx, the stress-induced sigma factors (rpoE and rpoS), Fe-S cluster, fatty acid and amino acid metabolism, stress response, and virulence (Gruzdev et al., 2012a; Finn et al., 2013a; Maserati et al., 2017, 2018). In addition, genes involved in propanoate metabolism, the citrate cycle, and lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis were downregated in Salmonella on milk chocolate, powdered milk, black pepper, and dried pet foods (Crucello et al., 2019). Formation of thin aggregative fimbriae and cell filamentation were implicated in desiccation tolerance of Salmonella (Mattick et al., 2000; White et al., 2006; Maserati et al., 2017). Most of these studies tested desiccation tolerance of Salmonella over relatively short periods of time on dry abiotic surfaces such as plastic, stainless steel, and paper, which may not be representative of the mechanisms employed by Salmonella to survive on LMFs.

The objective of the current study was to identify genetic determinants required for survival of Salmonella on LMFs. Mutant libraries created by random Tn5 insertion in the genomes of isolates from three Salmonella serovars were selected for both short and long-term survival on in-shell pistachios, followed by transposon-sequencing analysis to identify genetic determinants required for survival. The role of a subset of 12 genes identified via this combined mutagenesis and sequencing approach was then directly investigated by assessing the capacity of single-gene deletion (SGD) mutants to survive on pistachios.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Salmonella strains used in this study included Salmonella enterica sv Typhimurium strain 14028s, isolated from 4-week-old chickens in 1960 (Jarvik et al., 2010); Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 strain P125109, a clinical strain associated with a poultry outbreak in the United Kingdom (Toro et al., 2016); and Salmonella Newport strain C4.2, isolated from a tomato field in Virginia, United States (de Moraes et al., 2018). Single gene deletion (SGD) mutants of S. Typhimurium strain 14028s harbor a kanamycin (SGD-KanR) or chloramphenicol (SGD-CmR) resistance gene, oriented in the antisense and sense direction, respectively, in regard to the deleted gene (Porwollik et al., 2014). The strains were preserved at −80°C in Luria-Bertani broth (LB; Becton, Dickinson & Co. Sparks, MD, United States) containing 20% glycerol (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, United States). Bacterial cultures were grown in LB or on LB agar containing 1.2% agar (Becton, Dickinson & Co.) at 37°C for 24 h unless indicated otherwise. When necessary, growth media were supplemented with 60 μg/ml kanamycin (LB + Kan; Fisher Scientific) or 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol (LB + Cm, Acros Organics, NJ, United States).

Construction of Tn5 Mutant Libraries

The methods for construction of the barcoded Tn5 libraries were previously described (de Moraes et al., 2017, 2018). In brief, a library of Tn5 insertion mutants was constructed for each strain with a mini-Tn5 derivative into which we inserted an N18 random barcode using PCR. This derivative was integrated into the genome using the EZ-Tn5 <T7/KAN-2> promoter insertion kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI, United States). Mapping of barcoded transposons to specific locations in the genome was performed as described (de Moraes et al., 2017).

Negative Selection of Mutant Libraries for Survival on Pistachios

Frozen stocks of mutant libraries were thawed on ice and 1 ml was transferred into two separate 30 ml LB + Kan in 50-ml centrifuge tubes (Becton, Dickinson & Co.) and incubated at 37°C with shaking for 12 h. The cultures were washed twice in 5 ml sterile deionized water (dH2O), and combined to yield 10 ml of cell suspension, to be used as inoculum. In-shell pistachios were obtained from a commercial source and analyzed for total aerobic counts and Salmonella before use. For inoculation, 200 g of pistachios were weighed into sterile Whirl-Pak stomacher bags (5441 ml, Nasco, Fort Atkinson, WI, United States) and inoculated at 4% volume per weight by transferring 8 ml of the cell suspension in a series of four additions of 2 ml into the bag, each addition followed by vigorous shaking by hand for 30 sec. The inoculated pistachios were dried in a Nalgene polypropylene desiccator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) containing drierite desiccant (W.A. Hammond Drierite Co. Ltd., Xenia, OH, United States) for 24 h, at which time the Aw approximated that of uninoculated nuts. After drying, the nuts were placed into several 50 ml centrifuge tubes (VWR Int., Radnor, PA, United States), capped tightly, and stored at 25°C in the dark.

Salmonella from the inoculated pistachios were recovered immediately after inoculation, after drying, and then after various times of storage up to 120 days. In each case, 10 g of nuts (approximate 10 pistachios) were transferred into 20 ml LB + Kan in 532-ml Whirl-Pak bags (Nasco). The bag was vigorously hand-massaged for 1 min and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. For enumerations, 100 μl of the rinsate was serially diluted in dH2O and appropriate dilutions were plated on LB + Kan agar plates, followed by incubation at 37°C for 24 h. The remainder of the mixtures of pistachios and LB + Kan was incubated statically at 37°C for 12 h to amplify the pistachio-associated Salmonella populations, shaken manually for 30 s, and 1 ml of the resulting suspension was transferred into a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube (Fisher Scientific) and centrifuged at 15,000 × g, 25°C for 2 min. The pellets were then preserved at −80°C. The population of Salmonella in the enriched mixture was enumerated as described. The experiment was conducted in three independent trials with duplicate samples processed per trial.

Library DNA Preparation, Sequencing, and Data Analysis

The methods for library DNA preparation, sequencing and data analysis were previously described (de Moraes et al., 2017, 2018). In brief, bacteria were recovered and grown in LB + Kan. Bacteria were pelleted and lysed. The lysate was used as template for PCR using primers directly flanking the N18 barcode. The frequency of each barcode was determined by Illumina sequencing of 20 bases (and is shown for all three Salmonella Tn5 libraries in Supplementary Tables 1A–C). The aggregated abundances for the input and output libraries were statistically analyzed using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014), and the log2-fold changes and FDRs were reported.

Assessment of the Survival of SGD Mutants on Pistachios

Single-gene deletion mutants of S. Typhimurium 14028s were constructed previously (Porwollik et al., 2014). The mutants were grown in 30 ml of LB + Kan in 50-ml conical tubes (VWR Int.) at 37°C for 24 h with shaking. The cultures were pelleted, washed twice in dH2O, and used to inoculate 50 g of in-shell pistachios at 4% volume per weight as described above. The inoculated nuts were dried and stored as described above. For Salmonella enumerations from the inoculated pistachios immediately after inoculation, after drying and after 30, 65, 85, and 110 days of storage, 2 g of nuts (approximate 2 pistachios) were transferred into 5-ml dH2O in a 15-ml conical tube (Becton, Dickinson & Co). The mixtures were vortexed at high speed for 60 s, and appropriate dilutions of the liquid were plated on LB + Kan agar, followed by incubation at 37°C for 24 h. The experiment was conducted in two independent trials with duplicate samples per trial. For mutants that showed significantly higher reduction compared to the wild-type strain, corresponding mutants with the same gene deletion harboring a chloramphenicol resistance gene oriented in the antisense direction (Porwollik et al., 2014) were also tested for survival on pistachios, with enumerations performed on LB + Cm.

Statistical Analysis

The numbers of colony forming units (CFU) from the survival assays were entered into an Excel 2013 spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, United States), log transformed, exported to SigmaPlot 14.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, United States), and plotted against time to generate survival curves. Comparisons of log reductions between the populations of the wild-type bacteria and the SGD mutants on pistachios at different time points during storage were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Tukey’s test used to compare multiple means (α, 0.05).

Results and Discussion

Survival of Salmonella Wild-Type Strains and Random Mutant Libraries on Pistachios

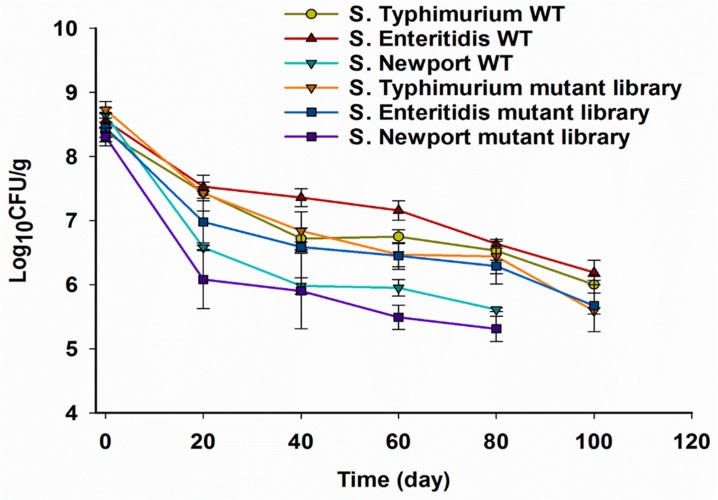

In the current study, we inoculated pistachios with higher numbers of Salmonella than are likely to contaminate LMFs in real life, in order to be able to adequately detect changes during survival and to identify mutants with relevant differences in persistence. The population of Salmonella (wild-type strains and mutant libraries) on pistachios immediately after inoculation was approximate 8.5 log CFU/g. The Aw of pistachios before inoculation, immediately after inoculation and after drying was 0.25, 0.43, and 0.32, respectively, with no significant changes in Aw during storage (data not shown). We noted differences in survival among the three strains that were employed. The population of S. Typhimurium 14028s and S. Enteritidis P125109 wild-type strains on pistachios was reduced by 1 log CFU/g after drying, with further reductions by 1.5 log CFU/g after storage for 120 days (Figure 1). A higher reduction of 2 log CFU/g was observed in the population of S. Newport C4.2 after drying, and the population was below 6 log CFU/g after 30 days of storage (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Survival of Salmonella wild-type (WT) strains and Tn5 mutant libraries on in-shell pistachios. Pistachios were inoculated, dried and stored, and populations of Salmonella were enumerated as described in section “Materials and Methods” immediately after inoculation, after drying, and periodically during storage. Data represent averages from three independent trials with duplicate samples per trial. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 6). Enumerations of S. Newport C4.2 on pistachios were discontinued when the population was less than 6 log CFU/g.

The observed survival of S. Typhimurium 14028s and S. Enteritidis P125109 on pistachios in this study corroborates findings from a previous study that reported reductions in the population of Salmonella on pistachios by approximate 1 and 1.4 log after drying and during storage at 24°C for 120 days, respectively (Kimber et al., 2012). The noticeably lower survival of S. Newport strain C4.2 on pistachios is quite unusual for Salmonella. Different S. Newport strains have been implicated in LMF-associated Salmonella outbreaks and, unlike the Newport strain we used, their desiccation tolerance was found to be comparable to S. Typhimurium and Enteritidis (Kirk et al., 2004; Gruzdev et al., 2012b; Centers for Disease Control Prevention [CDC], 2014). However, salmonellosis outbreaks involving strains of serovar Newport tend to be associated with fruit and vegetables (de Moraes et al., 2018). Indeed, functional analysis of the S. Newport C4.2 genome revealed unique adaptations to persistence in plants that are not shared by strains of other serotypes, including S. Typhimurium 14028s (de Moraes et al., 2018). Therefore, the poor survival of S. Newport strain C4.2 in LMFs may reflect trade-offs in this particular strain for adaptations related to plant colonization or perhaps temperate prophage induction under drying stress.

Overall, the survival of wild-type strains was slightly (0.3–0.5 log CFU/g) higher than observed with their respective mutant libraries strains, presumably because some mutants in the libraries are less fit, but this difference was not significant (Figure 1). Both the parental strain and the mutant library of S. Newport C4.2 declined markedly relative to the others, with population levels declining to <6 log CFU/g after 30 days of storage (Figure 1). Mutant libraries need to consist of more than 106 distinct mutants in order for the complexity of the library to be maintained and for profiles of mutant fitness to be determined. For this reason, survival assessments of S. Newport C4.2 and its mutant library were discontinued after 30 days.

Mutant library populations recovered from the inoculated pistachios immediately after inoculation (T0), after drying for 1 day (T1d) and after 120 days of storage (T120d) were grown in LB + Kan at 37°C for 12 h. This was done to facilitate detachment of strongly adhering cells, resuscitation of injured cells, and extraction of genomic DNA at sufficient concentration for sequencing.

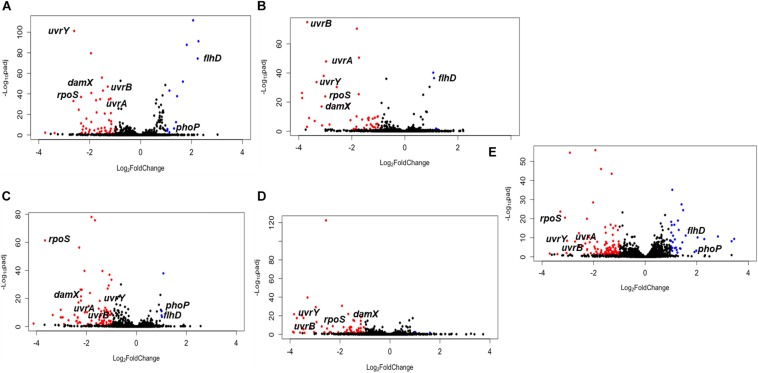

Tn5 Insertion Mutants Under Selection in Salmonella

The raw data of barcode counts and the genome positions of Tn5 insertions used for DESeq2 analysis are reported for all three genomes in the order Typhimurium, Enteritidis, Newport, in Supplementary Table 1. The plots of the relative abundance of Tn5 insertion sites (TIS) in mutant libraries that were selected on pistachios are shown in Figure 2. TIS with a significant change (P < 0.05) in abundance at T1d relative to T0, or T120d relative to T1d, and with at least a two-fold change (log2FC ≥ |1|) were considered to be selected, and thus the corresponding locus was considered to have a putative role in survival. In principle, TIS in mutants impaired for survival would be negatively selected (log2FC ≤ −1, P < 0.05), as the mutants would have a lower relative abundance on pistachios after drying or storage when compared to the input mutant pools. The corresponding gene would thus have a role in enhancing survival under the experimental conditions. Conversely, for TIS mutants that have higher relative abundance (log2FC ≥ 1, P < 0.05), the corresponding gene would have a role in reducing survival under the experimental conditions, or might not be required at all. For example, a mutant might be more fit than the wild type if the mutation stops the production of determinants not needed for survival under the tested conditions.

FIGURE 2.

The relative abundance of mutants after selection in pistachios. (A) S. Enteritidis P125109 mutant library on pistachios after drying for 1 day (T1d) relative to immediately after inoculation (T0); (B) S. Enteritidis P125109 mutant library on pistachios at 120 days of storage (T120d) relative to T1d; (C) S. Typhimurium 14028s mutant library on pistachios at T1d relative to T0; (D) S. Typhimurium 14028s mutant library on pistachios at T120d relative to T1d; (E) S. Newport C4.2 mutant library on pistachios at T1d relative to T0. Red dots indicate significant (P < 0.05) reduction by at least two-fold, blue dots indicate significant (P < 0.05) increase by at least two-fold, and black dots indicate non-significant and/or less than two-fold change in abundance. Data represent the average of three independent trials and duplicate samples per trial (n = 6). Some genes that are consistently under selection and discussed in the text are annotated.

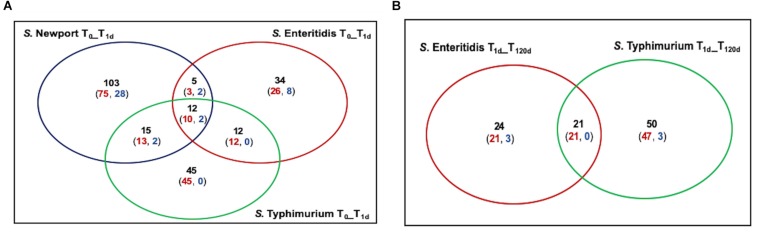

The most extensive selection occurred in the S. Newport C4.2 mutant library after drying (T1d versus T0) with selection of 135 TIS, of which 101 and 34 were negatively and positively selected, respectively (Figure 3A). This was particularly interesting in light of the above-discussed finding that this strain was markedly more impaired in survival on the dry pistachios than the other two strains (Figure 1). In mutant libraries of S. Enteritidis P125109 and S. Typhimurium 14028s, 63 and 84 TIS were selected, respectively, with the majority (51 and 80 TIS, respectively) being negatively selected (Figure 3A). Further storage of inoculated pistachios at 25°C for 120 days resulted in further selection of 45 and 71 TIS in the mutant libraries of S. Enteritidis P125109 and S. Typhimurium 14028s, respectively (Figure 3B). Overall, higher selection occurred during drying than during storage for all mutant libraries, suggesting that drying imposed the highest desiccation-related selection pressure.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of mutants under selection among the three Salmonella serovars. Insertion sites with significant (P < 0.05) differences by at least two-fold in relative abundance are shown in panel (A) after drying (T1d) compared to immediately after inoculation (T0), and (B) at 120 days of storage (T120d) compared to T1d. Black font indicate numbers of distinct Tn5 insertion sites with significant (P < 0.05) change by at least two-fold. Red and blue indicate mutants with a reduction and an increase in relative abundance, respectively.

Salmonella enterica genomes are generally syntenic in over 90% of their genome, with over 95% sequence identity (de Moraes et al., 2018). Concentrating on those part of the genomes shared by at least two of the three strains, the genes disabled by Tn5 insertions that were significantly changed (P < 0.05) in at least two libraries during drying and storage are listed in Table 1. Although the majority of these genes were strain-specific, 53 were significantly changed in at least two mutant libraries while 12 were changed (10 negatively and 2 positively) after drying in all three mutant libraries (Figure 3A). A few of the genes that were selected in two mutant libraries but not in the third one were absent in one specific library (6 in S. Newport C4.2 library, 2 in S. Enteritidis P125109 library, and 1 in S. Typhimurium 14028s library) (Table 1). The genes that were negatively selected in all three mutant libraries during drying included uvrA, uvrB, uvrY, rpoS, hupA, sspA, yifE, rbsR, damX, and STM14_2365, while phoP and flhD insertions were positively selected in all three libraries (Table 1). Similarly, 21 genes were negatively selected during storage in both the S. Enteritidis P125109 and S. Typhimurium 14028s mutant libraries (Figure 3B). With the sole exception of the insertion in hupA, genes that were negatively selected in all three mutant libraries during drying continued to be further negatively selected during dry storage (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Genes under selection in at least two different serovars.

| Log2 fold change Tinput_Toutput |

|||||

| S. Newport T0_T1d | S. Enteritidis T0_T1d | S. Typhimurium T0_T1d | S. Enteritidis T1d_T120d | S. Typhimurium T1d_T120d | |

| DNA repair mechanism | |||||

| STM14_5112 (uvrA)* | −2.56 | −1.18 | −1.41 | −2.97 | −3.16 |

| STM14_0926 (uvrB)* | −2.57 | −1.29 | −1.48 | −3.68 | −4.70 |

| STM14_4752 (uvrD) | NC** | NC | NC | −1.37 | −1.33 |

| STM14_2365 (uvrY)* | −2.32 | −2.61 | −2.22 | −3.88 | −3.52 |

| STM14_3289 (recN) | NC | NC | NC | −1.03 | −1.51 |

| STM14_4509 (recG) | −1.5 | NC | NC | −1.39 | −1.25 |

| STM14_4196 (Dam) | −3.11 | NC | −2.35 | NC | NC |

| STM14_2414 (Dcm) | −1.26 | NC | −1.2 | NC | −1.56 |

| Osmolarity response | |||||

| STM14_1317 (mdoG) | 3.45 | NC | 1.08 | NC | NC |

| STM14_1318 (mdoH) | 3.35 | NC | 1.01 | NC | NC |

| STM14_4217 (ompR) | NC | NC | NC | −1.81 | −3.84 |

| STM14_4216 (envZ) | NC | NC | NC | −2.14 | −3.73 |

| Lipopolysaccharide biogenesis | |||||

| STM14_2576 (rfbP) | NC | −2.25 | −2.95 | NC | NC |

| STM14_2579 (rfbN) | ND | −2.00 | −3.03 | −1.24 | −1.18 |

| STM14_2588 (rfbC) | NC | −1.37 | −2.41 | NC | NC |

| STM14_2590 (rfbD) | NC | −1.82 | −2.28 | NC | NC |

| STM14_4479 (rfaL) | NC | −1.67 | −2.25 | NC | NC |

| STM14_4478 (rfaJ) | NC | −1.38 | −2.35 | NC | NC |

| STM14_4783 (rfaH) | −1.55 | −2.14 | NC | NC | NC |

| Transcriptional regulators | |||||

| STM14_1409 (phoP) | 1.35 | 1.31 | 1.01 | NC | NC |

| STM14_3397 (emrR) | NC | NC | NC | −1.54 | −2.52 |

| STM14_3526 (rpoS)* | −3.29 | −2.64 | −3.66 | −3.33 | −2.63 |

| STM14_5011 (hupA) | −2.37 | −1.24 | −1.66 | NC | NC |

| STM14_5249 (nsrR) | −1.17 | NC | −1.42 | NC | −1.65 |

| STM14_2873 (lrhA) | −1.03 | NC | −1.25 | −1.29 | −1.28 |

| STM14_5242 (hfq) | −2.25 | NC | NC | −1.36 | −2.42 |

| Stringent response | |||||

| STM14_4991 (rpoC) | −1.29 | NC | −1.32 | NC | NC |

| STM14_4506 (rpoZ) | NC | −1.19 | −1.08 | NC | −1.72 |

| STM14_3564 (relA) | −1.13 | NC | −1.17 | NC | −1.28 |

| STM14_4033 (sspA)* | −2.18 | −1.59 | −1.86 | −1.08 | −3.77 |

| Others | |||||

| STM14_0896 (gpmA) | −1.97 | NC | −2.90 | NC | NC |

| STM14_1106 (aroA) | −1.24 | −1.02 | NC | NC | NC |

| STM14_1370 (fabF) | −1.55 | NC | −1.39 | NC | NC |

| STM14_2056 (rnb) | −1.94 | −1.41 | ND*** | −1.82 | ND |

| STM14_2341 (flhD) | 1.01 | 2.24 | 1.02 | 1.10 | NC |

| STM14_3527 (nlpD) | NC | −1.75 | −2.19 | −1.73 | NC |

| STM14_4039 (yhcB) | ND | −2.03 | −2.07 | NC | −3.88 |

| STM14_4694 (yifE)* | −2.02 | −1.73 | −2.22 | −2.05 | −3.46 |

| STM14_1755 (rnfD) | −1.71 | NC | −1.2 | NC | NC |

| STM14_4683 (rbsR)* | −1.55 | −1.48 | −1.80 | −1.13 | −1.92 |

| STM14_4682 (rbsK) | −1.34 | NC | −1.36 | NC | −1.47 |

| STM14_3566 (barA) | NC | −1.95 | −1.08 | −3.06 | −2.56 |

| STM14_4197 (damX)* | −1.24 | −1.94 | −2.24 | −3.00 | −1.74 |

| Hypothetical proteins | |||||

| STM14_4207 | 2.03 | 1.66 | NC | NC | NC |

| STM14_4197.J | ND | ND | −2.48 | ND | −3.85 |

| STM14_1261 | ND | NC | NC | −2.57 | −2.94 |

| STM14_2365.RJ* | −2.92 | −2.34 | −1.91 | −3.61 | −3.46 |

| Intergenic regions | |||||

| Intergen_1718 (2033472…2033683) | 1.05 | 2.27 | NC | 1.07 | NC |

| Intergen_2515 (3086724…3086785) | ND | −2.43 | −3.03 | −3.87 | NC |

| Intergen_3017 (3653422…3653601) | −1.84 | NC | −1.98 | NC | NC |

| Intergen_3018 (3654880…3654976) | ND | −2.34 | −2.32 | −3.69 | −3.04 |

| Intergen_3020 (3656644…3657107) | −4.48 | NC | −1.3 | NC | NC |

| Intergen_3365 (4120085…4120190) | −1.86 | ND | −2.08 | ND | 2.73 |

∗Bold type denotes genes impacted in all three libraries. ∗∗NC denotes genes or intergens that did not change significantly (Log2FC < | 1 | and P < 0.05). ∗∗∗ND denotes Tn5 integrations that were absent in the corresponding mutant library and thus not assayed.

Genes Putatively Important for Survival of Salmonella on Pistachios

Several genes appeared to be important for the survival of Salmonella on pistachios. Some of the genes encoded hypothetical proteins while others were implicated in DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, and osmolarity responses. These genes are categorized based on their molecular functions and discussed below.

DNA Recombination and Repair Mechanisms

Tn5 localization in several genes involved in DNA recombination and repair, including uvrA, uvrB, uvrD, recN, recG, dam, and dcm, was significantly underrepresented (P < 0.05) in the Salmonella mutant populations from the dried or stored pistachios, suggesting that the corresponding mutants were impaired for survival on this dry product (Table 1). These observations suggested that Salmonella undergoes DNA damage in low-moisture conditions, with survival requiring functional DNA repair systems. UvrA, UvrB and UvrD proteins are central components of the highly conserved nucleotide excision repair (NER) systems in prokaryotes (Kisker et al., 2013). The UvrA-UvrB complex identifies conformational changes induced by DNA lesions, a prerequisite for subsequent steps in NER, and facilitates the recruitment of UvrC, UvrD, DNA polymerase I and DNA ligase for DNA base repair (Truglio et al., 2004; Kisker et al., 2013). On the other hand, RecG, RecN, and UvrD are involved in recombinational repair of DNA damage that often involves double-stranded DNA breaks (Kuzminov, 2011). DNA adenine methyltransferase (Dam) and DNA cytosine methyltransferase (Dcm) are responsible for the majority of methylated DNA bases in Escherichia coli and Salmonella (Marinus and Løbner-Olesen, 2014). The importance of Dam in DNA mismatch repair, induction of the SOS response, and oxidative stress tolerance has been extensively documented and discussed (Chatti et al., 2012; Marinus and Løbner-Olesen, 2014; Stephenson and Brown, 2016).

Interestingly, uvrA, uvrB and uvrY were selected during both drying and storage, while dam and dcm were only selected during drying, and uvrD, recN and recG were only selected during storage (Table 1). This differential selection of DNA repair genes suggests that the NER pathway and methylation-directed DNA repair systems were especially important for repair of DNA damage during drying, when viability was also most markedly impacted. The findings agree with data from proteomic analysis of Salmonella under desiccation on glass beads which revealed significant abundance of DnaJ and UvrD, proteins involved in DNA repair, compared to cells in the non-desiccated inoculum suspension (Maserati et al., 2018). In addition, a Salmonella dam mutant exhibited significantly impaired survival on plastic petri plates (Mandal and Kwon, 2017). On the other hand, none of the DNA recombination and repair genes that appear to be important for survival in the current study were differentially expressed in transcriptome analyses of Salmonella under low-moisture conditions (Gruzdev et al., 2012a; Li et al., 2012; Finn et al., 2013b; Maserati et al., 2017). It is worthy of note that these transcriptome studies employed Salmonella on desiccated abiotic surfaces such a glass beads, plastics and stainless steel, in contrast to desiccation on pistachios in the current study. Moreover, a gene can be constitutively or transiently expressed and still be important for a phenotype. Thus, some genes that are important for desiccation tolerance of Salmonella may not be differentially expressed under desiccation.

The induction of DNA damage in response to desiccation has been reported in other bacteria, including Deinococcus radiodurans, Sinorhizobium meliloti, Bradyrhizobium japonicum, and spores of Bacillus subtilis (Dose et al., 1992; Tanaka et al., 2004; Cytryn et al., 2007; Humann et al., 2009). The exact causes of DNA damage under desiccation remain poorly understood, but may include covalent modifications and intracellular accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Humann et al., 2009). Moreover, it is not clear if desiccation-induced DNA repair causes adaptive mutations in Salmonella that confer higher tolerance to desiccation. For example, exposure of Listeria monocytogenes to sublethal acidic pH selected for point mutations in rpsU, encoding ribosomal protein S21, that conferred significantly higher tolerance to lethal acidic pH and other stressors (Metselaar et al., 2015). Therefore, the potential of desiccation-induced DNA damage as an adaptive desiccation survival strategy needs to be investigated.

Lipopolysaccharide Biogenesis

Several genes involved in LPS biogenesis including rfbP, rfbN, rfbC, rfbD, rfaL, rfaJ, and rfaH were found to be important for survival of Salmonella on pistachios (Table 1). RfbP, RfbN, RfbC, and RfbD are involved in O-antigen synthesis while RfaL, RfaJ, and RfaH mediate LPS core synthesis (Schnaitman and Klena, 1993). Previous studies reported that mutations in LPS biosynthesis genes significantly impaired survival of Salmonella on polystyrene petri dishes and formica melamine resin laminate under ambient conditions (Garmiri et al., 2008; Mandal and Kwon, 2017). Furthermore, LPS is a known virulence determinant of Salmonella and plays important roles in swarming motility, host invasion and oxidative stress tolerance (Toguchi et al., 2000; Thomsen et al., 2003; Choi and Groisman, 2013; Bogomolnaya et al., 2014).

Transcriptional Regulators and Stringent Response

Tn5 insertions in several transcriptional regulators, including rpoS, lrhA, nsrR, hupA, and emrR, appeared to result in impaired survival of Salmonella on pistachios, by approximate two- to eight-fold during drying, storage, or both (Table 1). Localization in rpoS had the greatest impact on survival with approximate eight-fold reduction (log2FC = −3) in relative abundance in all libraries during drying, and further reduction by eight-fold during storage (Table 1). The rpoS gene encodes the alternative sigma factor RpoS, a global regulator of stress-induced genes, virulence determinants and several metabolic processes in Gram-negative bacteria (Ibañez-Ruiz et al., 2000; Lévi-Meyrueis et al., 2014). The impaired survival on pistachios of Salmonella mutants with Tn5 localization in rpoS suggests that certain genes important for survival may be under RpoS control.

Regulation of RpoS intracellular levels is essential for homeostasis in Gram-negative bacteria (Hengge-Aronis, 2002). LrhA, a LysR homolog, is an important regulator of RpoS and other cellular functions such as flagellar synthesis, chemotaxis and NADH-dependent electron transport (Tran et al., 1997; Lehnen et al., 2002; Peterson et al., 2006). Deletion of lrhA in E. coli resulted in pleiotropic stationary phase defects due to decreased RpoS levels (Gibson and Silhavy, 1999). Mutants with Tn5 insertions in lrhA showed reduced survival during drying and storage in at least two mutant libraries (Table 1). Interestingly, RpoS regulation by LrhA is dependent on the small RNA (sRNA) chaperone Hfq (Peterson et al., 2006), and in the current study Salmonella mutants with Tn5 insertions in hfq showed reduced survival during storage (Table 1). These findings suggest that RpoS and its regulation are important for survival of Salmonella on LMFs. Interestingly, previous studies did not identify rpoS, lrhA, hfq and the other transcriptional regulators detected in the current study as important survival determinants in Salmonella under desiccation (Gruzdev et al., 2012a; Li et al., 2012; Finn et al., 2013b; Maserati et al., 2017).

Localization of Tn5 in rpoC and rpoZ impaired survival of Salmonella on pistachios (Table 1). RpoC and RpoZ make up the β’ and ω subunits of the RNA polymerase and are both involved in the stringent response in E. coli (Igarashi et al., 1989; Yamamoto et al., 2018). Mutational studies have shown that the RpoC and RpoZ subunits bind to the alarmone ppGpp which signals the induction of the stringent response in E. coli, and the RNA polymerase without these subunits failed to bind to ppGpp (Igarashi et al., 1989; Ross et al., 2013; Zuo et al., 2013). In the current study, insertion of Tn5 in ppGpp synthase, relA and the stringent starvation protein A (sspA) impaired survival of Salmonella on pistachios (Table 1). These observations suggest that Salmonella contaminating LMFs are starved and require stringent response genes for survival.

Osmolarity Response

Salmonella must be able to detect osmolarity changes in the environment in order to survive under desiccation. The EnvZ/OmpR two-component system is a well-characterized phosphorelay signal transduction system that mediates osmotic stress responses in Gram-negative bacteria (Cai and Inouye, 2002). In the current study, Salmonella mutants with Tn5 insertions in envZ and ompR were impaired for long-term survival on pistachios (Table 1). Under osmotic stress, EnvZ (inner cytoplasmic membrane-bound histidine kinase) phosphorylates OmpR in the cytoplasm (Cai and Inouye, 2002). Phosphorylated OmpR serves as a pleiotropic transcriptional regulator of outer membrane porin genes such as ompC and ompF and several other genes, including ssrA and ssrB that form a two-component regulator of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI-2) genes and hilC which is a known SPI-1 regulator (Lee et al., 2000; Oropeza and Calva, 2009; Cameron and Dorman, 2012). OmpC, OmpF and other membrane porins modulate membrane permeability in Gram-negative bacteria in response to environmental stress (van der Heijden et al., 2016). Therefore, failure to activate the EnvZ/OmpR two-component system in Salmonella mutants with Tn5 insertions in envZ and ompR was likely responsible for impaired survival on pistachios.

In the S. Newport C4.2 and S. Typhimurium 14028s mutant libraries, mdoH and mdoG, encoding osmoregulated periplasmic glucans (Opgs) OpgH and OpgG, respectively (Bohin, 2000), were positively selected during drying but not during storage of inoculated pistachios (Table 1). OpgH and OpgG are believed to catalyze the addition of glucosyl branches to a glucose backbone to form highly branched oligosaccharides that accumulate in the periplasmic space of most Proteobacteria, in response to low-osmolarity environments (Bohin, 2000; Lequette et al., 2004). However, the effect of Opgs on desiccation tolerance has remained elusive. In the current study, inactivation of mdoH and mdoG appears to be advantageous to survival of Salmonella in the LMF model that was investigated.

Other Genes and Intergenic Regions

Impaired survival of Salmonella on pistachios was associated with localization of Tn5 in several additional genes (nlpD, rnfD, rbsR, rbsK, barA, gpmA, aroA, fabF, and rnb) encoding proteins with various known functions as well as several other genes (yhcB, yifE, STM14_4207, STM14_4197.J, STM14_1261, and STM14_2365.RJ) encoding putative or hypothetical proteins (Table 1). Of these, only nlpD has been previously reported to be putatively involved in Salmonella desiccation tolerance (Gruzdev et al., 2012a).

Localization of Tn5 in six intergenic regions in Salmonella was associated with impaired survival on pistachios (Table 2). BLAST analysis suggested that these regions are conserved in diverse serotypes of Salmonella. Five of these intergenic regions were flanked by genes in which Tn5 insertions were also correlated with either impaired (e.g., rpoS, nlpD, dam, damX, hdfR) or enhanced (flhD) survival (Table 2). However, mutants with Tn5 localized in aroK and hofQ, flanking one of these intergenic regions, were present in the mutant libraries but were not selected in this model system. This may indicate that any phenotype may map inside the intergenic region

TABLE 2.

Genes flanking the six intergenic regions under selection in Salmonella on pistachios.

| Intergenic regions | Gene flanking at 5′ | Gene flanking at 3′ |

| Intergen_1718 | Flagella transcriptional regulator (flhD) | Hypothetical protein (STM14_2343) |

| Intergen_2215 | Alternative sigma factor (rpoS) | Murein hydrolase activator (nlpD) |

| Intergen_3017 | DNA adenine methyltransferase (dam) | Putative cell division protein (damX) |

| Intergen_3018 | Putative cell division protein (damX) | 3-dehydroquinate synthase (STM14_4198) |

| Intergen_3020 | Shikimate kinase gene (aroK) | DNA uptake porin gene (hofQ) |

| Intergen_3365 | HTH-type transcriptional regulator gene (hdfR) | Macrodomain ori organization protein encoding gene (maoP). |

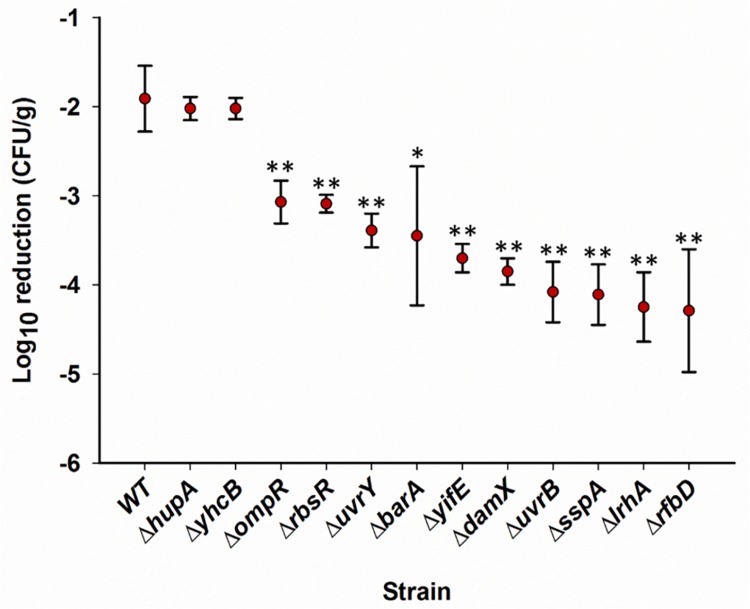

Survival of Single Gene Deletion Mutants on Pistachios

Further phenotype evaluation on pistachios was done using individual gene knockout mutants (Porwollik et al., 2014). Genes for this analysis were selected from the Tn5 data (Table 1) based on a significant (P < 0.05) reduction of at least two-fold in relative abundance after drying at T1d versus T0 and T120d versus T1d in at least two strains. These mutants included ΔrbsR, ΔdamX, ΔrfbD, ΔlrhA, ΔuvrB, ΔhupA, ΔyhcB, ΔompR, ΔbarA, ΔuvrY, ΔyifE, and ΔsspA, and mutants in six of these genes (uvrB, uvrY, sspA, damX, rbsR, and yifE) were negatively selected in all three libraries at T1d versus T0 (Table 1).

The wild-type Salmonella and the SGD mutants inoculated on pistachios ranged from 8.23 to 8.79 log CFU/g, with reductions by approximate 1 log CFU/g after drying for 1 day. After storage of inoculated pistachios at 25°C, most of the individual single gene deletion mutants, chosen for further study of their potential positive role of the deleted gene in survival, showed impairment in survival at all time points (Supplementary Table 2). At 110 days, 10 of the 12 SGD mutants showed significantly (P < 0.05) impaired survival with population reductions exceeding those of the wild-type strain by more than 100-fold for mutants ΔrfbD, ΔlrhA, ΔuvrB, and ΔsspA (Figure 4). In contrast, survival of two SGD mutants, ΔhupA and ΔyhcB, was similar to that of the parental strain throughout the 110 days (Figure 4). This is in contrast to the negative selection of Tn5 mutations in these genes when in competition with other Salmonella in a library. One possible reason for this difference in phenotype may be that these mutants compete less effectively when bacteria with a wild-type phenotype are present but are not impaired when surviving alone on pistachios. Alternatively, a Tn5 insertion may alter the function of a gene rather than eliminate it, or may have different polar effects on a neighboring CDS, compared to a whole gene deletion. Overall, the phenotypes of 10 of 12 SGD mutants tested for a positive role in survival corroborated the findings from the transposon sequencing analysis of the mutant libraries. These experiments were performed using gene knockouts with a kanamycin resistant cassette (Porwollik et al., 2014). Similar data were obtained with the chloramphenicol-resistant derivatives of these SGD mutants (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Survival of individual single-gene deletion mutants on in-shell pistachios. Pistachios were inoculated with single strains, dried and stored. Populations of Salmonella were enumerated as log10CFU/g, as described in “Materials and Methods”, immediately after inoculation, after drying, and periodically during storage. The difference between the population immediately after inoculation and at 110 days of storage is plotted for each mutant. Data represent averages from two independent trials with duplicate samples processed per trial. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 4). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.005, based on two tailed Student’s t-test. Supplementary Table 2 contains data for all time points.

Most of the genes identified by mutagenesis to be important for survival in the current study were not identified in previous studies that used differentially expressed RNAs or proteins as an assay to investigate the molecular basis of survival of Salmonella (Gruzdev et al., 2012a; Li et al., 2012; Finn et al., 2013b; Maserati et al., 2017). One explanation for some of these differences may be that we have measured the effect of mutation on survival directly, whereas the levels of RNA or protein do not necessarily correlate with the importance of the respective gene for survival (Price et al., 2013). This is supported by the finding that deletion of some genes that were previously reported to be differentially expressed in Salmonella under low-moisture conditions did not impact survival (Gruzdev et al., 2012a; Finn et al., 2013b). Another explanation may be that the previous studies primarily tested survival of Salmonella on abiotic surfaces and for shorter period of time. Thus, Salmonella may deploy different desiccation survival strategies depending on other factors in the environment.

Conclusion

In the current study, we have integrated transposon mutagenesis and sequence analysis to identify novel determinants important for survival of Salmonella on pistachios, employed as a model of low-moisture food (LMF). Our findings suggest that DNA recombination and repair, osmolarity regulation, lipopolysaccharide biogenesis, stringent response, and stress-induced sigma factors are some of the mechanisms employed by Salmonella to survive on LMFs. Elucidation of the molecular basis of the survival of Salmonella on LMFs may aid the development of improved detection and inactivation strategies, thereby reducing the food safety burden associated with contamination of LMFs.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Author Contributions

MM, VJ, and SK conceived the study. VJ, MM, SP, and WC performed the experiments and analyzed the data. VJ drafted the manuscript. SK, MM, and SP revised the manuscript. JF, MM, and SK secured the funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Benjamin Henson and Duncan Matthews for assisting with survival assessments.

Footnotes

Funding. VJ, JF, and SK were partially supported by the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) North America Food Microbiology Committee. ILSI North America is a public, nonprofit science foundation that provides a forum to advance understanding of scientific issues related to the nutritional quality and safety of the food supply. ILSI North America receives support primarily from its industry membership. MM, SP, and WC were supported by U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture grants 2015-67017-23360 and 2017-67015-26085; NIFA Hatch grant CA-D-PLS-2327-H, NIFA-BARD award 2017-67017-26180, and NIH grant AI 139557.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00726/full#supplementary-material

References

- Beuchat L. R., Komitopoulou E., Beckers H., Betts R. P., Bourdichon F., Fanning S., et al. (2013). Low-water activity foods: increased concern as vehicles of foodborne pathogens. J. Food Prot. 76 150–172. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuchat L. R., Mann D. A. (2014). Survival of Salmonella on dried fruits and in aqueous dried fruit homogenates as affected by temperature. J. Food Prot. 77 1102–1109. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogomolnaya L. M., Aldrich L., Ragoza Y., Talamantes M., Andrews K. D., McClelland M., et al. (2014). Identification of novel factors involved in modulating motility of Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium. PloS One 9:e111513. 10.1371/journal.pone.0111513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohin J. P. (2000). Osmoregulated periplasmic glucans in Proteobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 186 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S. J., Inouye M. (2002). EnvZ-OmpR interaction and osmoregulation in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 277 24155–24161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron A. D. S., Dorman C. J. (2012). A fundamental regulatory mechanism operating through OmpR and DNA topology controls expression of Salmonella pathogenicity islands SPI-1 and SPI-2. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002615. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention [CDC] (2009). Multistate outbreak of Salmonella infections associated with peanut butter and peanut butter-containing products—United States, 2008–2009. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 58 85–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention [CDC] (2014). Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella Infections Linked to Organic Sprouted Chia Powder. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/newport-05-14/index.html. (accessed on September 24, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention [CDC] (2016). Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella Montevideo and Salmonella Senftenberg Infections Linked to Wonderful Pistachios (Final Update). Available at https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/montevideo-03-16/index.html (accessed on October 19, 2019)∗ [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention [CDC] (2019). Reports of Selected Salmonella Outbreak Investigations. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/outbreaks.html. (accessed on October 23, 2019)∗ [Google Scholar]

- Chatti A., Messaoudi N., Mihoub M., Landoulsi A. (2012). Effects of hydrogen peroxide on the motility, catalase and superoxide dismutase of dam and/or seqA mutant of Salmonella Typhimurium. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 28 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J., Groisman E. A. (2013). The lipopolysaccharide modification regulator PmrA limits Salmonella virulence by repressing the type three-secretion [sic] system Spi/Ssa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 9499–9504. 10.1073/pnas.1303420110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crucello A., Furtado M. M., Chaves M. D. R., Sant’Ana A. S. (2019). Transcriptome sequencing reveals genes and adaptation pathways in Salmonella Typhimurium inoculated in four low water activity foods. Food Microbiol. 82 426–435. 10.1016/j.fm.2019.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csonka L. N., Hanson A. D. (1991). Prokaryotic osmoregulation: genetics and physiology. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 45 569–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cytryn E. J., Sangurdekar D. P., Streeter J. G., Franck W. L., Chang W. S., Stacey G., et al. (2007). Transcriptional and physiological responses of Bradyrhizobium japonicum to desiccation-induced stress. J. Bacteriol. 189 6751–6762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Moraes M. H., Becerra S. E., Salas G. I., Desai P., Chu W., Porwollik S., et al. (2018). Genome-wide comparative functional analyses reveal adaptations of Salmonella sv. Newport to a plant colonization lifestyle. Front. Microbiol. 9:877. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Moraes M. H., Desai P., Porwollik S., Canals R., Perez D. R., Chu W., et al. (2017). Salmonella persistence in tomatoes requires a distinct set of metabolic functions identified by transposon insertion sequencing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83:e03028-16. 10.1128/AEM.03028-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dose K., Bieger-Dose A., Labusch M., Gill M. (1992). Survival in extreme dryness and DNA-single-strand breaks. Adv. Space Res. 12 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farakos S. M. S., Frank J. F. (2014). “Challenges in the control of foodborne pathogens in low-water activity foods and spices,” in The Microbiological Safety of Low Water Activity Foods and Spices, eds Gurtler J. B., Doyle M. P., Kornacki J. L. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Finn S., Condell O., McClure P., Amézquita A., Fanning S. (2013a). Mechanisms of survival, responses, and sources of Salmonella in low-moisture environments. Front. Microbiol. 4:331 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn S., Händler K., Condell O., Colgan A., Cooney S., McClure P., et al. (2013b). ProP is required for the survival of desiccated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium cells on a stainless steel surface. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 4376–4384. 10.1128/AEM.00515-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmiri P., Coles K. E., Humphrey T. J., Cogan T. A. (2008). Role of outer membrane lipopolysaccharides in the protection of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium from desiccation damage. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 281 155–159. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson K. E., Silhavy T. J. (1999). The LysR homolog LrhA promotes RpoS degradation by modulating activity of the response regulator SprE. J. Bacteriol. 181 563–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruzdev N., McClelland M., Porwollik S., Ofaim S., Pinto R., Saldinger-Sela S. (2012a). Global transcriptional analysis of dehydrated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 7866–7875. 10.1128/AEM.01822-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruzdev N., Pinto R., Sela S. S. (2012b). Persistence of Salmonella enterica during dehydration and subsequent cold storage. Food Microbiol. 32 415–422. 10.1016/j.fm.2012.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruzdev N., Pinto R., Sela S. (2011). Effect of desiccation on tolerance of Salmonella enterica to multiple stresses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77 1667–1673. 10.1128/AEM.02156-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengge-Aronis R. (2002). Signal transduction and regulatory mechanisms involved in control of the sigma(S) (RpoS) subunit of RNA polymerase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66 373–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokunan H., Koyama K., Hasegawa M., Kawamura S., Koseki S. (2016). Survival kinetics of Salmonella enterica and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli on a plastic surface at low relative humidity and on low–water activity foods. J. Food Prot. 79 1680–1692. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-16-081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humann J. L., Ziemkiewicz H. T., Yurgel S. N., Kahn M. L. (2009). Regulatory and DNA repair genes contribute to the desiccation resistance of Sinorhizobium meliloti Rm1021. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 446–453. 10.1128/AEM.02207-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibañez-Ruiz M., Robbe-Saule V., Hermant D., Labrude S., Norel F. (2000). Identification of RpoS (sigma S)-regulated genes in Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 182 5749–5756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi K., Fujita N., Ishihama A. (1989). Promoter selectivity of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: omega factor is responsible for the ppGpp sensitivity. Nucleic Acids Res. 17 8755–8765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs S., Aramini J., Ciebin B., Farrar J. A., Ahmed R., Middleton D., et al. (2005). An international outbreak of salmonellosis associated with raw almonds contaminated with a rare phage type of Salmonella Enteritidis. J. Food Prot. 68 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvik T., Smillie C., Groisman E. A., Ochman H. (2010). Short-term signatures of evolutionary change in the Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium 14028 genome. J. Bacteriol. 192 560–567. 10.1128/JB.01233-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber M. A., Kaur H., Wang L., Danyluk M. D., Harris L. J. (2012). Survival of Salmonella, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and Listeria monocytogenes on inoculated almonds and pistachios stored at -19, 4, and 24°C. J. Food Prot. 75 1394–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk M. D., Little C. L., Lem M., Fyfe M., Genobile D., Tan A., et al. (2004). An outbreak due to peanuts in their shell caused by Salmonella enterica serotypes Stanley and Newport- sharing molecular information to solve international outbreaks. Epidemiol. Infect. 132 571–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisker C., Kuper J., Van Houten B. (2013). Prokaryotic nucleotide excision repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5:a012591. 10.1101/cshperspect.a012591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzminov A. (2011). Homologous recombination-experimental systems, analysis, and significance. EcoSal Plus 4:10.1128/ecosallus.7.2.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A. K., Detweiler C. S., Falkow S. (2000). OmpR regulates the two-component system SsrA-SsrB in Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. J. Bacteriol. 182 771–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnen D., Blumer C., Polen T., Wackwitz B., Wendisch V. F., Unden G. (2002). LrhA as a new transcriptional key regulator of flagella, motility and chemotaxis genes in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 45 521–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lequette Y., Odberg-Ferragut C., Bohin J. P., Lacroix J. M. (2004). Identification of mdoD and mdoG paralog which encodes a twin-arginine-dependent periplasmic protein that controls osmoregulated periplasmic glucan backbone structures. J. Bacteriol. 186 3695–3702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Meyrueis C., Monteil V., Sismeiro O., Dillies M.-A., Monot M., Jagla B., et al. (2014). Expanding the RpoS/σS-Network by RNA sequencing and identification of σS-controlled small RNAs in Salmonella. PLoS One 9:e96918. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Bhaskara A., Megalis C., Tortorello M. L. (2012). Transcriptomic analysis of Salmonella desiccation resistance. Foodborne Pathogens Dis. 9 1143–1151. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M. I., Huber W., Anders S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal R. K., Kwon Y. M. (2017). Global Screening of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium genes for desiccation survival. Front. Microbiol. 8:1723. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinus M. G., Løbner-Olesen A. (2014). DNA methylation. EcoSal Plus 6:10.1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maserati A., Fink R. C., Lourenco A., Julius M. L., Diez-Gonzalez F. (2017). General response of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium to desiccation: a new role for the virulence factors sopD and sseD in survival. PLoS One 12:e0187692. 10.1371/journal.pone.0187692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maserati A., Lourenco A., Diez-Gonzalez F., Fink R. C. (2018). iTRAQ-Based global proteomic analysis of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium in response to desiccation, low water activity, and thermal treatment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84:e0393-18. 10.1128/AEM.00393-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick K. L., Jørgensen F., Legan J. D., Cole M. B., Porter J., Lappin-Scott H. M., et al. (2000). Survival and filamentation of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis PT4 and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104 at low water activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 1274–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metselaar K. I., den Besten H. M., Boekhorst J., van Hijum S. A., Zwietering M. H., Abee T. (2015). Diversity of acid stress resistant variants of Listeria monocytogenes and the potential role of ribosomal protein S21 encoded by rpsU. Front. Microbiol. 6:422. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oropeza R., Calva E. (2009). The cysteine 354 and 277 residues of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi EnvZ are determinants of autophosphorylation and OmpR phosphorylation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 292 282–290. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01502.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C. N., Carabetta V. J., Chowdhury T., Silhavy T. J. (2006). LrhA regulates rpoS translation in response to the Rcs phosphorelay system in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188 3175–3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porwollik S., Santiviago C. A., Cheng P., Long F., Desai P., Fredlund J., et al. (2014). Defined single-gene and multi-gene deletion mutant collections in Salmonella enterica sv Typhimurium. PLoS One. 9:e99820. 10.1371/journal.pone.0099820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M. N., Deutschbauer A. M., Skerker J. M., Wetmore K. M., Ruths T., Mar J. S., et al. (2013). Indirect and suboptimal control of gene expression is widespread in bacteria. Mol. Syst. Biol. 9:660. 10.1038/msb.2013.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross W., Vrentas C. E., Sanchez-Vazquez P., Gaal T., Gourse R. L. (2013). The magic spot: a ppGpp binding site on E. coli RNA polymerase responsible for regulation of transcription initiation. Mol. Cell 50 420–429. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnaitman C. A., Klena J. D. (1993). Genetics of lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in enteric bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57 655–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. F., Hildebrandt I. M., Casulli K. E., Dolan K. D., Marks B. P. (2016). Modeling the effect of temperature and water activity on the thermal resistance of Salmonella Enteritidis PT 30 in wheat flour. J. Food Prot. 79 2058–2065. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-16-155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson S. A., Brown P. D. (2016). Epigenetic influence of Dam methylation on gene expression and attachment in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Front. Public Health 4:131. 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M., Earl A. M., Howell H. A., Park M. J., Eisen J. A., Peterson S. N., et al. (2004). Analysis of Deinococcus radiodurans’s transcriptional response to ionizing radiation and desiccation reveals novel proteins that contribute to extreme radioresistance. Genetics 168 21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen L. E., Chadfield M. S., Bispham J., Wallis T. S., Olsen J. E., Ingmer H. (2003). Reduced amounts of LPS affect both stress tolerance and virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Dublin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 228 225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toguchi A., Siano M., Burkart M., Harshey R. M. (2000). Genetics of swarming motility in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium: critical role for lipopolysaccharide. J. Bacteriol. 182 6308–6321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro M., Retamal P., Ayers S., Barreto M., Allard M., Brown E. W., et al. (2016). Whole-genome sequeincing analysis of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis isolates in Chile provides insights into possible transmission between gulls, poultry, and humans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82 6223–6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran Q. H., Bongaerts J., Vlad D., Unden G. (1997). Requirement for the proton-pumping NADH dehydrogenase I of Escherichia coli in respiration of NADH to fumarate and its bioenergetic implications. Eur. J. Biochem. 244 155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truglio J. J., Croteau D. L., Skorvaga M., DellaVecchia M. J., Theis K., Mandavilli B. S., et al. (2004). Interactions between UvrA and UvrB: the role of UvrB’s domain 2 in nucleotide excision repair. EMBO J. 23 2498–2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heijden J., Reynolds L. A., Deng W., Mills A., Scholz R., Imami K., et al. (2016). Salmonella rapidly regulates membrane permeability to survive oxidative stress. MBio 7 1238–1216. 10.1128/mBio.01238-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A. P., Gibson D. L., Kim W., Kay W. W., Surette M. G. (2006). Thin aggregative fimbriae and cellulose enhance long-term survival and persistence of Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 188 3219–3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K., Yamanaka Y., Shimada T., Sarkar P., Yoshida M., Bhardwaj N., et al. (2018). Altered distribution of RNA polymerase lacking the omega subunit within the prophages along the Escherichia coli K-12 genome. MSystems 3:e0172-17. 10.1128/mSystems.00172-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y., Wang Y., Steitz T. A. (2013). The mechanism of E. coli RNA polymerase regulation by ppGpp is suggested by the structure of their complex. Mol. Cell 50 430–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.