Abstract

This article describes the rapid mitigation strategies in addressing the rising number of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases in Singapore. Learning from the severe acute respiratory syndrome experience in 2003, early preparation started in January 2020 when Wuhan was declared as the epicentre of the epidemic. The government had constructed a three-pronged approach which includes travel, healthcare and community measures to curb the spread of COVID-19.

Keywords: Covid-19, Pandemic, Mitigating strategies, Rapid response

Highlights

-

•

This article describes the preparations and rapid mitigation strategies in addressing the rocketing number of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases in Singapore.

-

•

The government had constructed a three-pronged approach which includes travel, healthcare and community measures to curb the spread of COVID-19.

-

•

Careful and thoughtful planning with successive rapid executions were necessary to balance the profound impact of the socio-economic activities and the healthcare system.

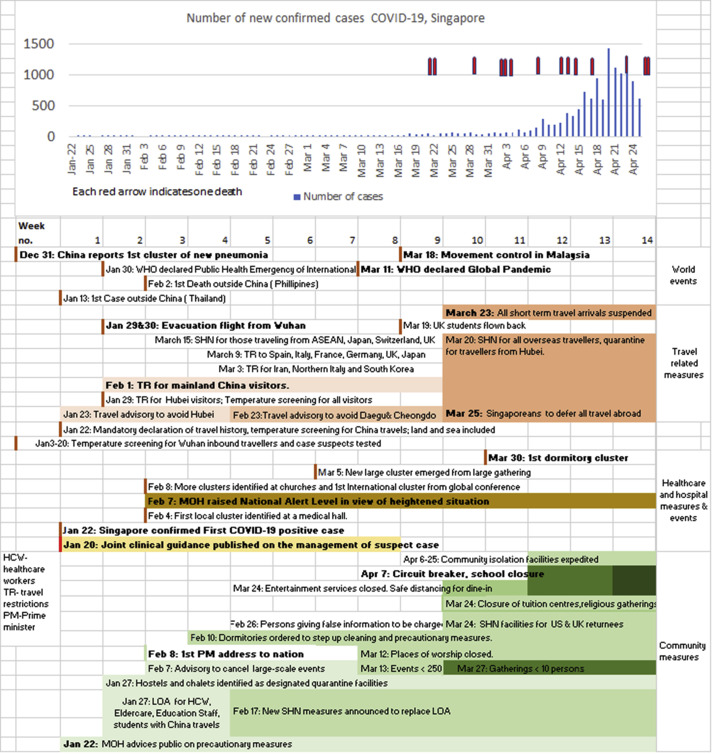

Singapore confirmed its first coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) case on January 22, 2020. At the time of writing, the cumulative number of cases in Singapore had exceeded 22,000. This article describes the preparations and rapid mitigation strategies in addressing the rocketing number of COVID-19 cases in the country (see Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Timeline of events and measures taken at various levels. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; WHO = World Health Organization; SHN = Stay-Home-Notice; MOH = Ministry of Health; LOA = leave of absence.

Travel-related measures

Learning from the painful severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) experience in 2003, early preparation started in January 2020 when Wuhan city was declared as the epidemic epicentre. Border control measures were placed as early as January 2 when the Ministry of Health (MOH) issued a health advisory and implemented temperature screening for passengers arriving from Wuhan. This was gradually tightened with restrictions extended to Hubei province and then mainland China in conjunction with declaration of the outbreak as a ‘Public Health Emergency of International Concern’ on January 30. On Singapore's end, the public was advised successively against outbound travel to Hubei, China and subsequently Daego and Cheongdo counties in South Korea as cases in these regions multiplied. Expatriation of Singaporeans from Wuhan was carried out with stringent quarantine and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 testing measures.1

Bilateral agreements were also made with the Malaysian government in February to align screening protocols at land borders. A joint field epidemiology training network to share surveillance data was activated. This had led to identification of the first international cluster in Singapore resulting from a global business conference. Stricter travel controls in Singapore and worldwide were imperative as early studies had confirmed that the mean R0 for COVID-19 is around 3.28.2

By early March, travel restrictions were extended to Iran, South Korea, Japan, Italy, Spain, France, Germany and the United Kingdom. These restrictions were implemented before the World Health Organization announced COVID-19 as a ‘pandemic’ on March 11. Further enhancement took place when Stay-Home-Notice (SHN) was issued to all overseas travellers on March 20. All travel restrictions and ‘isolation’ orders were capped at the standard 14 days based on the COVID-19 incubation period.

Healthcare and hospital measures

At the healthcare level, the MOH and National Centre for Infectious Diseases jointly developed guidelines on management of case suspects, which were disseminated to hospitals, physicians and laboratories in January.3 After the first confirmed case, contact tracing yielded two more positive cases in Singapore, while Malaysia had their first three cases from Singapore's index case. Vigorous contact tracings were conducted through activity mapping, analytic tools, surveillance footages, door-to-door enquiries with the help of the Singapore Police Force and smartphone application (TraceTogether).4 Coupled with the antibody laboratory tests developed by Duke-NUS Medical School, the link between Singapore's two largest COVID-19 clusters in February was uncovered.5

Fever surveillance among healthcare workers was implemented, in which all healthcare workers, including clinical and non-clinical employees, were to report temperature twice daily. Employees having a temperature of 37.5 °C and higher would be required to seek immediate medical attention and not report to work. This strategy was used to identify potentially infected healthcare workers early during the SARS outbreak in 2003.6

Community measures

At the community level, the MOH raised public awareness on the importance of personal hygiene, handwashing, wearing of masks, civic mindedness and health-seeking behaviours. Timely dissemination of reliable information to the public was proven effective in the previous SARS outbreak to dissipate anxieties.7 When the national alert level was raised to the second highest level, the government regularly updated the public on precautionary measures, containment efforts and assurance of national supplies.

As early as February 17, stricter SHN has replaced leave of absence (LOA). SHN law enforcement requires residents and long-term pass holders travelling from high-risk places to stay home mandatorily at all times, monitor their health and use contactless delivery for their food and daily essentials. Previously, persons on LOA were able to briefly leave their residential properties for food, groceries and ‘important personal matters’. Revocation of permanent resident status, cancellation of work passes, fines and jail sentences were among the outcomes of those breaching the laws.

Closure of places commenced from places of worship to entertainment services and tuition centres. Business continuity plans for companies kicked off with staggering of work hours at workplaces. Food and beverage industries were advised to comply with safe distancing measures. As part of crowd-limiting measures, fixed seats in eateries, buses and trains were marked as not to be occupied. Fines were imposed for failure in abiding by safe distancing—serving as a reminder and deterrent to the public.

As the number of cases rose rapidly, reciprocating measures were implemented promptly. The announcement of the circuit breaker (partial lockdown with elevated safe distancing measures and movement restriction in public and private places) on April 4 suspended non-essential services and led to school closures. This endeavour corresponded to lockdowns and movement restrictions in many other countries.8 As the measure did not show satisfying results in the initial two weeks, a four-week extension of this order was announced on April 21 along with tighter community measures such as closure of more work premises and controlled access to crowded places.

Singapore saw the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases surge in early April 2020 after the identification of several foreign worker dormitory clusters. These workers were housed in mega-dormitories with a capacity of up to 13,000 occupants, where they lived in close proximity and shared communal facilities. They also gathered in large groups at workplaces and public spaces during rest days. The high-density living between the 180,000 workers meant that they were always at risk of promoting transmissions. A special taskforce was formed to curb the spread in dormitories and to ensure the workers' well-being. The taskforce locked down dormitories with infection clusters, isolated those symptomatic and moved some of the workers to new accommodations. Strict hygiene measures, sanitization and safe distancing measures were adopted. Medical support was deployed to these dormitories for early and extensive testing, isolation and treatment.

Several quarantine and isolation facilities have been repurposed as early as January to contain the ever-increasing number of cases, but these facilities were inadequate. Many public venues worldwide have been converted to isolation facilities for patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 as the demand exceeded hospitals' surge capacity.9 Resorts and convention centres (with a combined capacity of more than 10,000 at the time of writing) have been converted to house stable patients with mild symptoms of COVID-19. The healthcare workforce has also been deployed to these community facilities. As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to rise, the government has been working relentlessly on another makeshift facility at a shipping terminal with the capacity for 15,000 patients and will be sourcing other avenues, including cruise ships.

With the current circuit breaker in place, the highest number of cases per day was 1426. Ever since the peak, the mean number of cases dropped to 681 at the time of writing. Local community cases and cases among foreign workers in dormitories peaked at 116 and 1371, respectively, per day and dropped to an average of 9 and 658 cases, respectively, per day.10

While some would debate on the tardiness of certain measures being implemented, we opined that careful and thoughtful planning with successive rapid executions has been carried out to balance the profound impact of the socio-economic activities and the healthcare system.

Author statements

Ethical approval

None required.

Funding

Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Ministry of Health or the SingHealth Institution.

Competing interests

None declared.

References

- 1.Ng O.T., Marimuthu K., Chia P.Y., Koh V., Chiew C.J., De Wang L. SARS-CoV-2 infection among travelers returning from Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(15):1476–1478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y., Gayle A.A., Wilder-Smith A., Rocklöv J. The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. J Travel Med. 2020 Mar 13;27(2):taaa021. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health Singapore. MOH steps up precautionary measures in response to increase in cases of novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan- 20 January 2020. (https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/moh-steps-up-precautionary-measures-in-response-to-increase-in-cases-of-novel-coronavirus-pneumonia-in-wuhan). Accessed 8 May 2020.

- 4.The Strait Times. A guide to Singapore's Covid-19 contact-tracing system- 28 March 2020. (https://www.straitstimes.com/multimedia/a-guide-to-singapores-covid-19-contact-tracing-system). Accessed 8 May 2020.

- 5.Singapore General Hospital. Test developed by Duke-NUS helps find link between two COVID-19 clusters- 26 February 2020. (https://www.sgh.com.sg/news/academic-medicine/test-developed-by-duke-nus-helps-find-link-between-two-covid-19-clusters-). Accessed 8 May 2020.

- 6.Gopalakrishna G., Choo P., Leo Y.S., Tay B.K., Lim Y.T., Khan A.S. SARS transmission and hospital containment. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(3):395. doi: 10.3201/eid1003.030650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quah S.R., Hin-Peng L. Crisis prevention and management during SARS outbreak, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):364. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau H., Khosrawipour V., Kocbach P., Mikolajczyk A., Schubert J., Bania J. The positive impact of lockdown in Wuhan on containing the COVID-19 outbreak in China. J Travel Med. 2020 May 18;27(3):taaa037. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen S., Zhang Z., Yang J., Wang J., Zhai X., Bärnighausen T. Fangcang shelter hospitals: a novel concept for responding to public health emergencies. Lancet. 2020;395:1305–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30744-3. Published Online April 2, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health Singapore. Covid -19 situation report. (https://www.moh.gov.sg/covid-19/situation-report). Accessed 8 May 2020.