Highlights

-

•

Due to COVID-19, compliance of manufactured respirators with standards seems to be placed in the second plan.

-

•

Personal protective equipments (PPE), such as respirators, causes carbon dioxide re-breathing in healthcare workers.

-

•

Even when resting, both expiratory and inspiratory carbon dioxide levels increase significantly with the use of PPE.

-

•

It should be kept in mind that healthcare workers may experience symptoms related to hypercapnia during their use of PPE.

Dear Editor,

It is reported that the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) can be transmitted via droplets and contact to infected surfaces [1]. Healthcare workers who undertake the follow-up and treatment of these infected patients use personal protective equipment (PPE) such as filtering facepiece respirators (FFRs; type of FFRs used in this study is FFP2 respirators and it is approximately equivalent of N95 respirators) and surgical masks, which are recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), to prevent contamination [2]. These FFP-2 respirators must therefore be close fitting to prevent air leakage. However, the risk of carbon dioxide retention due to re-breathing in healthcare workers who use a FFP-2 respirators for a long time with minimal air leakage is not clear [3]. In our study, it was aimed to evaluate changes in end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) and ventilation parameters in healthcare workers while wearing PPE in COVID-19 outbreak.

After obtaining ethics committee approval (date April 2, 2020 and 07/270 numbered, Mersin University, Turkey) and receiving written informed consents, a total of 12 healthy male healthcare workers between the ages of 25–40, using PPE in the COVID-19 outbreak, were included in the study. Data of the participants regarding age (30.0 ± 2.87), body mass index (BMI, mean value 24.3 kg/m2) and smoking status (n = 6) were recorded. Participants were monitored via Capnostream™ 20 bedside monitor (Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA) which can measure nasal EtCO2, fractional inspired carbon dioxide (FiCO2), respiratory rate (RR), peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) and heart rate (HR).

Before the PPE was worn, EtCO2, FiCO2, RR, SpO2 and HR values of the participants were recorded for 5 min without any physical activity (baseline measurements). Subsequently, the FFP-2 respirator without exhalation valve (3 M Aura™ 9320+, Minneapolis, US) was worn with a surgical mask and same parameters of the participants were recorded during 30 min in resting position. After wearing the PPE, the measurements of the participants with baseline values up to 30 min were statistically analyzed. p ˂ 0.05 value was considered statistically significant. Participants were also questioned for the presence of symptoms that may occur due to hypercapnia.

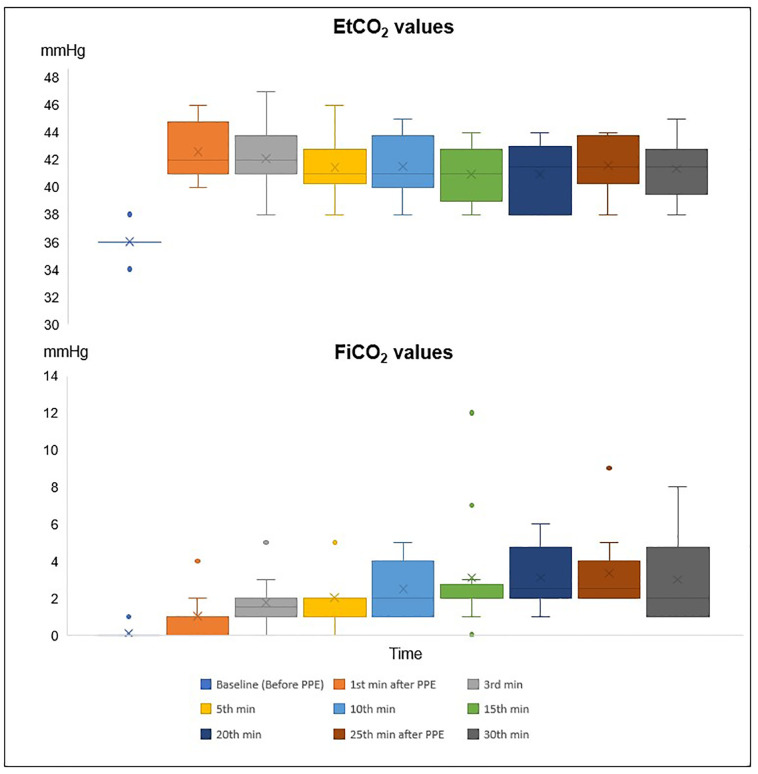

EtCO2 values of the participants measured in all time periods by nasal route after wearing PPE were found to be statistically significantly higher than before wearing PPE (baseline) (p ˂ 0.003) (Fig. 1 ). All FiCO2 measurements from the 10th minute after the PPE was worn by the participants were statistically significantly higher than baseline FiCO2 value (p ˂ 0.005) (Fig. 1). In comparisons with RR, HR, SpO2 or smoking status, we could not find a statistically significant difference.

Fig. 1.

Variations of EtCO2 and FiCO2 measurements during 30 min.

EtCO2: end tidal carbon dioxide pressure, FiCO2: fractional inspired carbon dioxide.

In our study, none of the participants had symptoms which may be due to hypercapnia. However, in a published case, a healthy intensivist who wore FFP-2 respirator to perform a percutaneous tracheostomy in a patient with multidrug resistant tuberculosis and showed symptoms of dyspnea, tachycardia and tremor at 30th minutes of procedure [4]. Meanwhile, the intensivist's EtCO2 level measured at the mouth by hand-held capnometry was 6.3 kPa (47.25 mmHg). In this published case report, the authors thought that symptoms developed due to hypercapnia [4].

There are several limitations in the current report. First, the depth of breathing and tidal volume was not measured to avoid air leakage. Second, the effects of FFP-2 respirators on airway resistance and flow have not been evaluated. Likewise, the differences in exercise and rest were not compared.

In conclusion, it was observed that the use of FFP-2 respirator with a surgical mask cover was significantly increasing the EtCO2 and FiCO2 values of healthcare workers without any disease while resting position. Further studies are needed on the safety of devices used by healthcare workers, especially PPE which is extensively used in outbreaks.

Author statement

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Levent Özdemir, Mustafa Azizoğlu and Davud Yapıcı. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Levent Özdemir and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Levent Özdemir:Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition.Mustafa Azizoğlu:Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - review & editing, Resources.Davud Yapıcı:Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Resources, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Paules C.I., Marston H.D., Fauci A.S. Coronavirus infections—more than just the common cold. JAMA. 2020;323(8):707–708. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization World Health Organization; 2020. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and considerations during severe shortages: interim guidance. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331695 6 April 2020. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 3.Johnson A.T. Respirator masks protect health but impact performance: a review. J Biol Eng. 2016;10:4. doi: 10.1186/s13036-016-0025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher S.J., Clark M., Stanley P.J. Carbon dioxide re-breathing with close fitting face respirator masks. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:910. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]