Abstract

The results of analysis of CCD photometric observations for seven Hungaria asteroids are reported: 3873 Roddy, 7187 Isobe, (7247) 1991 TD1, 8348 Bhattacharyya, (25332) 1999 KK6, (30311) 2000 JS10, and (67175) 2000 BA19. Of this group, 3873 Roddy and 7187 Isobe, are considered to be new discoveries of small binary (DP < 10 km) systems. This brings the total of known Hungaria binaries to 16. (7247) 1991 TD1 also resembles a binary object, but there are concerns with this conclusion because the second period is almost commensurate with an Earth day. It is a low-amplitude object with ambiguous period solutions. 8348 Bhattacharyya may be an example of an asteroid with a spin axis nearly in the ecliptic plane, which results in low amplitude lightcurves that are difficult to analyze. (25332) 1999 KK6 showed some evidence of a binary nature but it is more likely due to a trait of Fourier analysis. (30311) 2000 JS10 is another example where the Fourier analysis may have been led astray. (67175) 2000 BA19 also shows signs of a secondary period, but of 275 h. This would make it one of small number of objects that show two periods, one of ~2.2-2.5 h, and the other of 200 h or more.

CCD photometric observations of seven asteroids were made at the Palmer Divide Observatory (PDO) from 2012 June to September. The lightcurves for each presented some unusual features that gave reason to believe that, in five cases, the object might be binary. For two of those, the evidence is sufficient to consider them new binary discoveries. The strength of the evidence for the others is not, however, to the point where one can make any claims with certainty. At the very least, these candidates warrant high-precision photometry at future observations to confirm, refine, or refute the results given here. The other cases presented some challenges during analysis that make them good case studies for those doing asteroid photometry and period analysis.

Background

See the introduction in Warner (2010) for a discussion of equipment used in 2012, analysis software and methods, and overview of the lightcurve plot scaling. The “Reduced Magnitude” in the plots is Johnson V or Cousins R (indicated in the Y-axis title) corrected to unity distance by applying −5*log (rΔ) with r and Δ being, respectively, the Sun-asteroid and Earth-asteroid distances in AU. The magnitudes were normalized to the phase angle given in parentheses, e.g., alpha(6.5°), using G = 0.15 unless otherwise stated.

For the sake of brevity in the following discussions on specific asteroids, only some of the previously reported results are referenced. For a more complete listing, the reader is referred to the asteroid lightcurve database (LCDB, Warner et al., 2009). The on-line version allows direct queries that can be filtered a number of ways and the results saved to a text file. A set of text files, including the references with bibcodes, is also available for download at http://www.minorplanet.info/lightcurvedatabase.html. Readers are strongly encouraged to obtain, when possible, the original references listed in the LCDB for their work.

Individual Asteroids

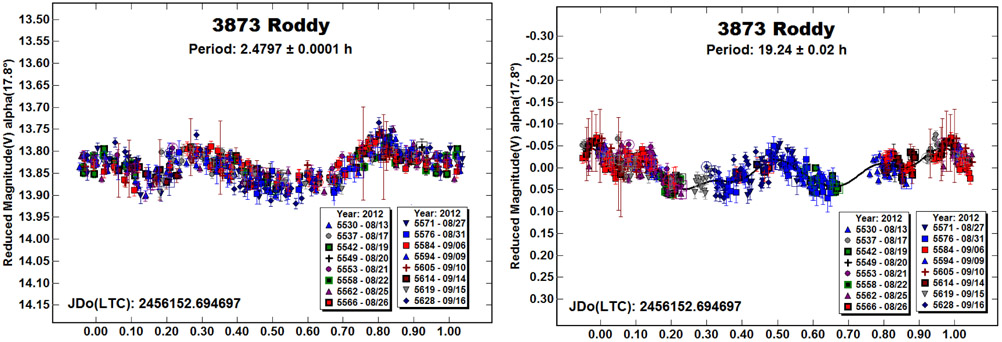

3873 Roddy.

This Hungaria asteroid was previously observed at PDO in 2005 (Warner, 2006), 2007 (Warner, 2008a), 2009 (Warner, 2009), and 2010 (Warner, 2011b). The results from each data set was a period of ~2.479 h. Data from the 2007 apparition gave unconfirmed indications that the asteroid was binary and the orbital period was about 48 h. This was based, however, on only two nights where either an eclipse or occultation was supposedly seen. The phase angle bisector longitude (LPAB) at the time was about 356°. The LPAB during the 2012 apparition was similar, ~322°, and so the asteroid was followed for a greater amount of time than usual to see if evidence of a binary could be found.

Analysis of the 2012 data set of more than 400 observations found good indications of a second period of 19.24 ± 0.02 h. On the assumption that this is a binary, the lightcurve gives evidence of a satellite with the estimated size ratio of the pair is Ds/Dp = 0.27 ± 0.02.

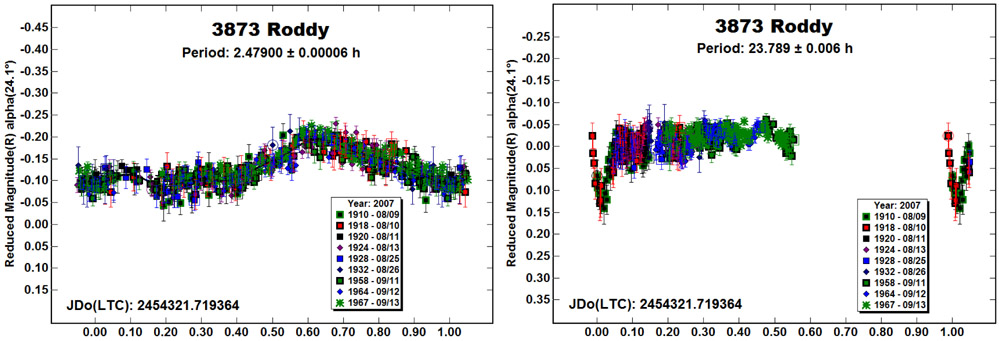

Using these results as a guideline, the data from 2007 were reanalyzed. Figure 2 shows the results. This gave P1 = 2.47900 ± 0.00006 h, in good agreement with the period found from the 2012 analysis. However, the data could not be fit to a period of about 19.3 h. Instead, the only reasonable solution was one 23.8 h. An additional concern is that the two “events” in the 2007 data are at the beginning of the evening runs. There do not appear to be any issues with the early data of those sessions, e.g., the comp star averages don’t show ill behavior and a test star in the field near the asteroid shows a “flat curve.” Still, the 2007 data should be viewed with at least some suspicion.

Figure 2.

The lightcurves for 3873 Roddy based on data obtained in 2007.

From the five apparitions observed so far, the short period seems to be well-defined and in no doubt. Obviously, the two secondary periods presented here cannot both be right. Another curiosity is the significant difference in the shape of the “primary” period lightcurve between the two apparitions even though the viewing aspects and phase angles were fairly similar. High-quality observations are strongly encouraged in the future.

7178 Isobe.

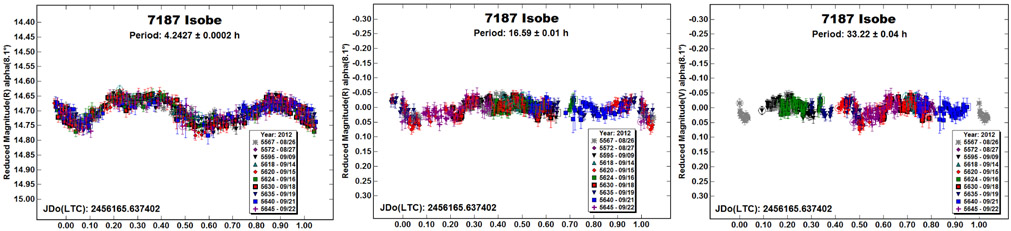

Previous apparitions worked at PDO include 2004, 2007, and 2011. The period was first reported to be 2.440 h (Warner, 2005a) or 2.58 h (Warner, 2008b) but follow up analysis of all data sets after the 2011 apparition (Warner, 2011c) determined that a better solution was 4.243 h. The observations in 2012 showed indications of a satellite, leading to a somewhat extended campaign in search of convincing evidence. On the assumption of there being a satellite, Figure 3, using the data from 2012, shows the primary rotation lightcurve with a period of 4.2427 ± 0.0002 h, amplitude 0.09 ± 0.01 mag (top) and two possible solutions for the secondary period. Of the two, the longer solution, P = 33.22 ± 0.04 h, seems a little more probable since the “events” are about equally spaced in the overall curve, i.e., about 0.5 rotation apart. If real, the satellite is probably tidally-locked to its orbital period. Based on the analysis of the 2012 data, the earlier data sets were analyzed anew.

Figure 3.

7187 Isobe lightcurves from 2012. The left-hand plot is the rotation of the purported primary. The middle plot shows the shorter possible solution for the satellite, which is probably tidally-locked to its orbital period. The right-hand plot shows the longer solution with a possible near total eclipse around 0.55 rotation phase.

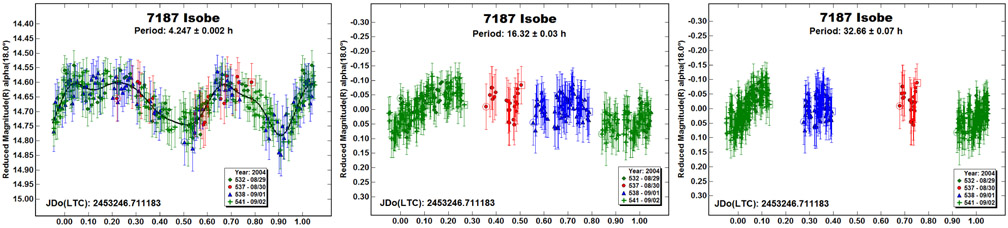

The 2004 apparition (Figure 4, LPAB ~353°) also showed signs of a satellite. The primary period was 4.246 ± 0.001 h. The two secondary periods were 16.34 ± 0.03 h and 32.66 ± 0.07 h. Given the noisy data, on the order of ± 0.1 mag, and smaller data, set the agreement with the 2012 results is reasonably good.

Figure 4.

7187 Isobe lightcurves from 2004. The data were on the order of ± 0.1 mag and the coverage of the longer secondary period not as complete as in other apparitions. This may have led to the slight disagreement with results from the other apparitions.

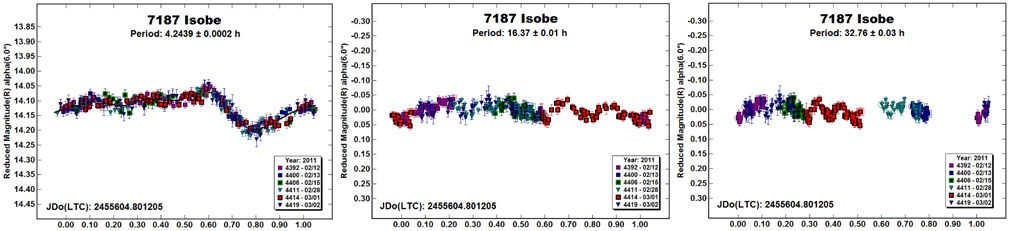

The results from 2007 (Figure 5, LPAB ~83°) and 2011 (Figure 6, LPAB ~149°) are in good agreement with 2012 for the primary period. The two longer periods are somewhat shorter than found in 2012. This could be due to a lack of coverage, both overall and of multiple instances of supposed events.

Figure 5.

7187 Isobe lightcurves from 2007. This longer second period lightcurve shows what is commonly attributed to a tidally-locked satellite with mutual events (about 0.1 and 0.6 rotation phase).

Figure 6.

7187 Isobe lightcurves from 2011.

Overall, it is likely that this asteroid is a binary. Given the apparent observation of events at varying values of LPAB, the obliquity of the spin axis of the primary is somewhat low and so high-quality observations at future apparitions have a good chance of helping confirm the nature of the asteroid.

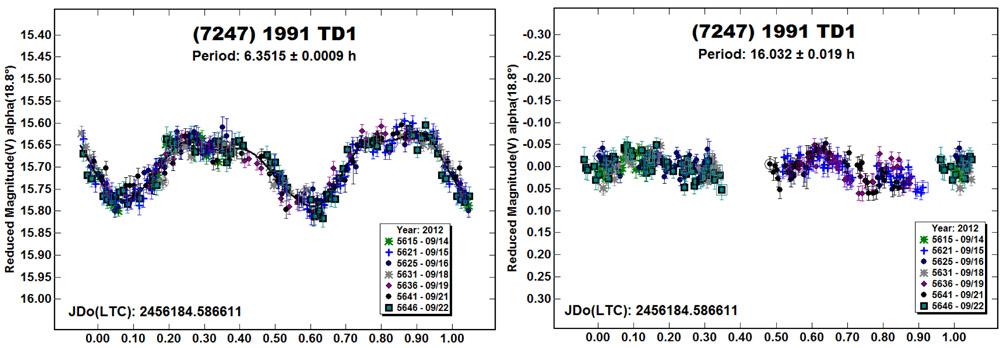

(7247) 1991 TD1.

This was the first apparition of observations at PDO for this Hungaria asteroid. No entries for it were found in the LCDB. Since the untreated lightcurve seemed to have some minor deviations, a search for a second period was made. The result was a very weak solution of 16.032 h. However, there are many concerns with this solution, the primary one being that it is almost exactly commensurate with an Earth day and so observations every other night cover almost the exact same part of the lightcurve. The alternate sides of the curve have the same shape, meaning that a period of 8 h or 12 h would fit about as well (Harris, private communications). These anomalies might be systematic errors tied to the location in the sky, the flat field, or other errors. However, a field star of about the same brightness and near the asteroid was measured and it did not show the variations found in the secondary lightcurve of the asteroid. At best, this can be said to be a good candidate for future follow-up.

8348 Bhattacharyya.

This Hungaria was worked at PDO in 2007 (Warner, 2008a) under the designation 1988 BX. At that time, a period of 38.6 h with an amplitude of 0.1 mag was reported. It was given a U = 1 (probably wrong) rating in the LCDB. Data were obtained in 2012 August and September with the hope of finding a more definitive rotation period. Fortune was not kind. The LPAB in 2007 was about 3° while in 2012 it was about 333°. Since the longitudes differed by only 30 degrees, it was likely that the amplitude of the lightcurve would be similar in both case, and it was. The low amplitude could mean that the object is not very elongated, but that conclusion awaits observations at another apparition, when the LPAB is near about 90° or 270°.

The 2012 data fit a period of 19.58 h better than one of 39.8 h, which was found when trying to duplicate the results from the 2007 apparition. Figure 8 shows the 2007 data forced to a period in the range of 19-21 h as well as the 2012 data phased to 19.58 h and 39.8 h. These support the shorter period but are hardly conclusive. Observations at future apparitions, especially at significantly different longitudes, are encouraged.

Figure 8.

The lightcurves for 8348 Bhattacharyya. At left is a plot of the 2007 data with a period of 19.60 h. The middle plot is of the 2012 data with a period of 19.58 h. The right-hand plot attempted to plot the 2012 data to a period near the 38.6 h period reported in Warner, 2008a.

(25332) 1999 KK6.

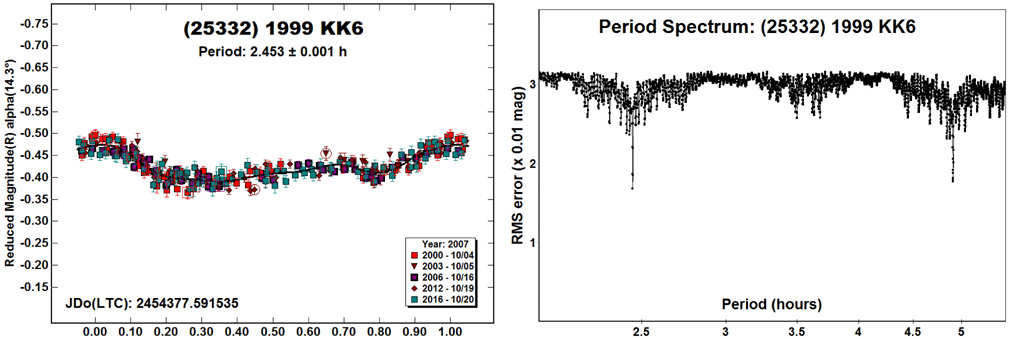

The 2012 apparition was the second one at which this Hungaria was observed at PDO. The first time was in 2007 (Warner, 2008b) when a period of 2.4531 h was reported but also that one of 4.9062 h was possible (see Figure 9). It’s of some interest that a period search of the 2007 data from 2-5 hours using steps of 0.01 h shows almost no trace of the 2.45 h solution while one at 4.9 h stands out, but not nearly as much as in Figure 10. This shows the need to assure that the step sizes in a Fourier analysis don’t allow “skipping over” what may the true solution.

Figure 9.

The lightcurve for (25332) 1999 KK6 in 2007. There was no evidence of a satellite found. The period spectrum (right) shows a strong preference for a solution of 2.453 h, which does not fit with the 2012 data.

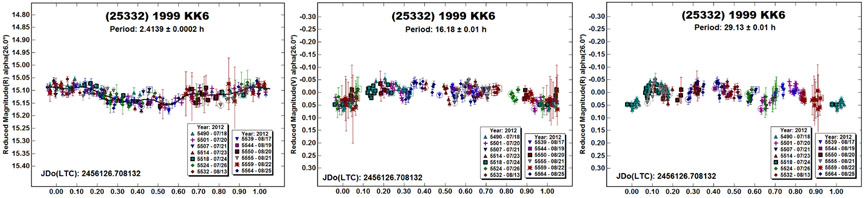

Figure 10.

The lightcurves for (25332) 1999 KK6 in 2012 when using 4th order Fourier fits. If 6th order fits were used, the long period solutions changed to different, non-commensurate values, indicating that the analysis was finding false periods within the noise of the data. This makes this asteroid an unlikely binary candidate.

The revised analysis of the 2007 data set was prompted by hints of a secondary period in the 2012 data, initial analysis of which found a period of about 4.8 h, but the fit was not particularly good, thus the attempts to find a second period. Those lead to a period of 2.414 h as well as two possible solutions for a second period (Figure 10), 16.18 h or 29.13 h, or almost exactly a 9:5 ratio. Of the two secondary solutions, the shorter one shows something that might be expected of a tidally-locked satellite, i.e., the 0.07 mag broad bowing of the curve, although is asymmetric in shape. Attempts to find a solution near the double period were not productive.

All this was done with 6th order fits in the Fourier analysis. However, when 4th order fits were tried, while the primary period did not change significantly, the secondary periods did. More important, the new values were not commensurate with the original ones. As demonstrated by Harris et al. (2012), such changes are often indicative that the analysis is locking on to random noise in the data and the resulting periods cannot be trusted. For all the ways that the secondary plots from the 2012 data might seem plausible, they are more likely false and merely serve to “dust the dirt off” the single period curve. This is all the more likely given the sometimes noisy and sparse data due to the asteroid moving through crowded star fields.

Despite the likely probability that this is a single body, it should remain a “target of interest” at future apparitions.

(30311) 2000 JS10.

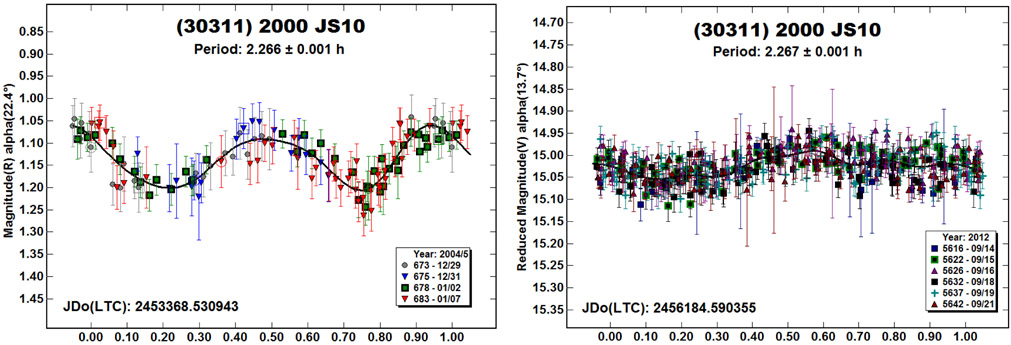

Previous observations and analysis at PDO (Warner, 2005b) found a period of 2.266 h and amplitude 0.15 mag. These make the asteroid a good binary candidate and, if for no other reason, it was observed in 2012 to provide additional data for spin axis modeling. Figure 11 shows the lightcurves from 2004 and 2012. A check of the 2004 data found no significant traces of a secondary period. With amplitude of 0.15 mag, the odds of a bimodal solution were favored over that of a monomodal. This served as a guide, but not hard rule, when analyzing the 2012 data.

Figure 11.

The lightcurve for (25332) 1999 KK6 in 2007. There was no evidence of a satellite found. The period spectrum (right) shows a strong preference for a solution of 2.453 h, which does not fit with the 2012 data.

Analysis of the 2012 data found a period in almost perfect agreement with the earlier result, but with a lower amplitude of only 0.06 mag. This favors having the spin axis near the LPAB at that time, i.e., about 350°, or its +180° solution of 170°.

An attempt was made to look for a secondary period in the 2012 data, despite it being noisy due to the asteroid moving through crowded star fields. A weak solution was found at about 13.7 h. However, this is very close to an integral multiple of the 2.267 h period and, as outlined in the discussion on (25332) 1999 KK6, is likely the result of the Fourier analysis locking onto noise in the data. Subtracting that faint noise would, naturally, appear to make the lightcurve for the shorter solution appear better.

Since this is a binary candidate, observations are encouraged at future apparitions but the analysis should not be influenced by these results. Independent confirmation, not a self-fulfilling conclusion, is what’s required.

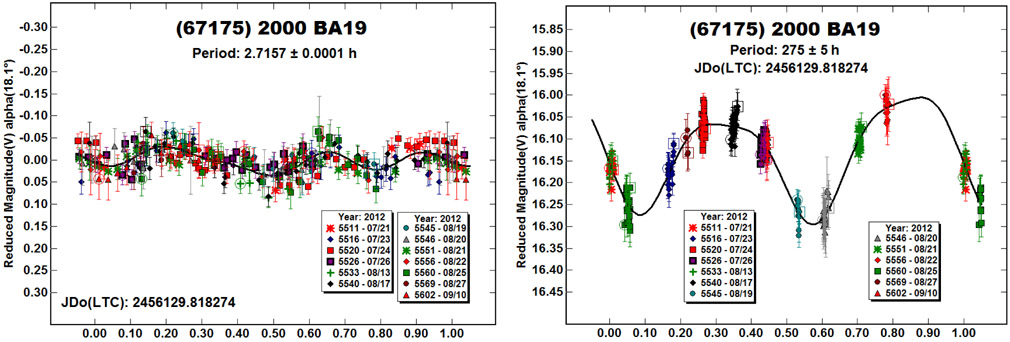

(67175) 2000 BA19.

This is the first apparition at which this Hungaria was observed at PDO. No entries could be found in the LCDB. The lightcurve with a short period of 2.7157 h and amplitude of about 0.07 mag, is typical for a primary in a small binary system. However, what is not typical is the apparent large amplitude (0.29 mag) secondary lightcurve with a period of 275 h. At least two other asteroids have shown similar characteristics, 8026 Johnmckay (P1: 2.2981 h, P2. 372 h; Warner, 2011a) and (218144) 2002 RL66 (P1: 2.49 h, P2: 588 h; Warner et al., 2010).

Jacobson and Scheeres (2012, and references therein) have explored the theoretical evolution of asynchronous binaries and found that one possible track, where the primary is synchronous, the secondary asynchronous, and the system has a high mass ratio (> ~0.2), may account for these three unusual cases. Given the long secondary periods, the chances of recording mutual events with standard photometry, even if deep enough, are exceedingly poor. Therefore, confirmation of these objects may be a long time coming, if ever at all. One hope is that Adaptive Optics (AO) or speckle photometry might be able to isolate the two bodies. The author has been in contact with Jacobson and there are plans to try to obtain AO observations of these candidates when/if the opportunity allows.

Conclusion

Analysis of data obtained at PDO in 2012 and reanalysis of earlier observations indicates that two asteroids, 3783 Roddy and 7187 Isobe, are probably binary asteroids. Three other objects showed some signs of a satellite but these are better attributed to traits in Fourier analysis giving false leads. There is an expression, “When you hear hoof beats, don’t think zebras,” meaning that one should always keep the rule of Occam’s Razor in mind: the simplest answer is usually the right one. This doesn’t mean that one shouldn’t investigate when there are even just faint hoof beats, but he should have an open mind and a good dose of skepticism when doing so.

The case of (67175) 2000 BA19, where it may be a member of a rare form of binary asteroids, provides some cautionary lessons. The first is that data should always be placed on at least an internal system with as stable a zero point as possible. Otherwise, the temptation can be (as seen in the past) to mask long period variations by forcing the zero points of individual sessions on the assumption of a shorter period.

There are many ways to achieve this goal. Even one of ± 0.05 mag stability can go a long way towards unveiling new discoveries. In some cases, however, a level of 0.01-0.02 mag is required. This is especially true when trying to coax evidence of a satellite from a lightcurve. So far, deviations of 0.05 mag are about the current limit for reliably detecting mutual events. It may not be possible to go much lower than this without finding too many “zebras.”

The second important lesson is that it is dangerous to presume. When a long period asteroid is found, there is a temptation to minimize the number of data points obtained each night so that other objects can be observed. As the number of data points goes down, the need for well-calibrated data goes up – significantly. Small errors in measurements can lead to large errors in the final solution. More to the point, however, is that getting too few data points may hide a short period riding on top of the long period roller coaster. As a result, the additional evidence to confirm objects such as 2000 BA19 may be forever lost. Balancing the two needs is one of the more difficult aspects of asteroid photometry.

Figure 1.

The lightcurves for 3873 Roddy during the 2012 apparition. The left-hand plot shows the rotation of the primary of a purported binary system. The right-hand plot shows the result after subtracting the top lightcurve.

Figure 7.

The lightcurves for (7247) 1991 TD1. Given the amplitude that is approaching 0.2 mag, a bimodal lightcurve for the “primary” is preferred, though still not absolute. See the text for a discussion of the secondary lightcurve. In short, the evidence for the asteroid being binary is far from sufficient.

Figure 12.

The lightcurve for (67175) 2000 BA19. The left-hand plot shows what appears to be a short period component superimposed on the long period lightcurve. Calibrated data, i.e., on at least an internal standard, are required to handle this type of object.

Table I.

Observing circumstances. The phase angle (α) is given at the start and end of each date range.

| # | Name | mm/dd/(20)yy | Pts | Phase | LPAB | BPAB | Period | P.E. | Amp | A.E. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3873 | Roddy | 08/09–09/13/07 | 472 | 24.1,18.1 | 356 | 31 | 2.47900 | P | 0.00006 | 0.11 | 0.01 |

| 3873 | Roddy | 08/13–09/16/12 | 405 | 17.7,22.1 | 322 | 31 | 2.4797 | P | 0.0001 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| 7187 | Isobe | 08/29–09/02/04 | 289 | 18.0,17.1 | 353 | 19 | 4.247 | P | 0.002 | 0.18 | 0.02 |

| 7187 | Isobe | 11/11–12/16/07 | 258 | 27.5,18.6 | 83 | 28 | 4.2431 | P | 0.0001 | 0.15 | 0.01 |

| 7187 | Isobe | 02/12–03/02/11 | 234 | 6.1,15.0 | 149 | −10 | 4.2437 | P | 0.0003 | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| 7187 | Isobe | 08/26–09/21/12 | 507 | 8.0,20.0 | 333 | 13 | 4.2427 | P | 0.0002 | 0.09 | 0.01 |

| 7247 | 1991 TD1 | 09/14–09/22/12 | 311 | 18.7,21.1 | 336 | 17 | 6.3515 | P | 0.0009 | 0.17 | 0.01 |

| 8348 | Bhattacharyya | 09/05–10/03/07 | 413 | 22.7,21.2* | 3 | 28 | 19.60 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | |

| 8348 | Bhattacharyya | 08/26–09/10/12 | 337 | 14.9,18.7 | 333 | 21 | 19.58/39.83 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.10 | 0.01 | |

| 25332 | 1999 KK6 | 10/04–10/20/07 | 235 | 14.3,14.0* | 14 | 16 | 2.453/4.906 | 0.001 | 0.08 | 0.01 | |

| 25332 | 1999 KK6 | 07/18–08/25/12 | 206 | 26.0,26.1* | 315 | 36 | 2.4139 | P | 0.0002 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| 30311 | 2000 JS10 | 09/14–09/21/12 | 395 | 13.7,13.9 | 352 | 25 | 2.267 | 0.001 | 0.06 | 0.01 | |

| 67175 | 2000 BA19 | 07/21–09/10/12 | 239 | 18.1,23.4* | 320 | 21 | 2.7157 | P | 0.0001 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

An asterisk (*) indicates the phase angle reached a minimum during the period and started to increase. LPAB and BPAB are each the average phase angle bisector longitude and latitude. A ‘P’ in the period column means the value is for the presume primary in a binary system. See the text for details regarding the second period. If two periods are given, the solution was ambiguous, with either being about equally likely.

Acknowledgements

Funding for observations at the Palmer Divide Observatory is provided by NASA grant NNX10AL35G, by National Science Foundation grant AST-1032896.

References

- Harris AW, Pravec P, and Warner BD (2012). “Looking a gift horse in the mouth: Evaluation of wide-field asteroid photometric surveys.” Icarus 221, 226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson S and Scheeres D (2012). “Formation of the Asynchronous Binary Asteroids.” in Proceedings for the 43rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. LPI Contribution No. 1659, id.2737. [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2005a). “Lightcurve analysis for asteroids 242, 893, 921, 1373, 1853, 2120, 2448 3022, 6490, 6517, 7187, 7757, and 18108.” Minor Planet Bul. 32, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2005b). “Asteroid lightcurve analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory - winter 2004-2005.” Minor Planet Bul. 32, 54–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2006). “Asteroid lightcurve analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory - late 2005 and early 2006.” Minor Planet Bul. 33, 58–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2008a). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory - June - October 2007.” Minor Planet Bul. 35, 56–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2008b). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory: September-December 2007.” Minor Planet Bul. 35, 67–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2009). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory: 2009 March – June.” Minor Planet Bul. 36, 172–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2010). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory: 2010 March – June.” Minor Planet Bul. 37, 161–165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD, Pravec P, Kusnirak P, and Harris AW (2010). “A Tale of Two Asteroids: (35055) 1984 RB and (218144) 2002 RL66.” Minor Planet Bul. 37, 109–111. [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2011a). “A Quartet of Known and Suspected Hungaria Binary Asteroids.” Minor Planet Bul. 38, 33–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2011b). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory: 2010 September-December.” Minor Planet Bul. 38, 82–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2011c). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory: 2010 December- 2011 March.” Minor Planet Bul. 38, 142–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD, Harris AW, and Pravec P (2009) “The Asteroid Lightcurve Database.” Icarus 202, 134–146. [Google Scholar]