This cross-sectional study characterizes otolaryngologist participation and performance in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System in 2017.

Key Points

Question

How did otolaryngologists perform in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) for Medicare in 2017?

Findings

This cross-sectional study found that in 2017, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services required 6512 active otolaryngologists to participate in the MIPS; among these, 68.6% received bonuses for exceptional performance and 10.3% incurred penalties for failure to participate. The proportion of otolaryngologists earning bonuses for exceptional performance varied by reporting affiliation (individual: 56.5%; group: 67.6%; alternative payment model: 97.1%).

Meaning

Most otolaryngologists participating in the 2017 MIPS received performance bonuses, although variation exists within the field.

Abstract

Importance

The Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) for Medicare is the largest pay-for-performance program in the history of health care. Although the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the MIPS in 2017, the participation and performance of otolaryngologists in this program remain unclear.

Objective

To characterize otolaryngologist participation and performance in the MIPS in 2017.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cross-sectional analysis of otolaryngologist participation and performance in the MIPS from January 1 through December 31, 2017, using the publicly available CMS Physician Compare 2017 eligible clinician public reporting database.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The number and proportion of active otolaryngologists who participated in the MIPS in 2017 were determined. Overall 2017 MIPS payment adjustments received by participants were determined and stratified by reporting affiliation (individual, group, or alternative payment model [APM]). Payment adjustments were categorized based on overall MIPS performance scores in accordance with CMS methodology: penalty (<3 points), no payment adjustment (3 points), positive adjustment (between 3 and 70 points), or bonus for exceptional performance (≥70 points).

Results

In 2017, CMS required 6512 of 9526 (68.4%) of active otolaryngologists to participate in the MIPS. Among these otolaryngologists, 5840 (89.7%) participated; 672 (10.3%) abstained and thus incurred penalties (−4% payment adjustment). The 6512 participating otolaryngologists reported MIPS data as individuals (1990 [30.6%]), as groups (3033 [46.6%]), and through CMS-designated APMs (964 [14.8%]). The majority (4470 of 5840 [76.5%]) received bonuses (maximum payment adjustment, +1.9%) for exceptional performance, while a minority received only a positive payment adjustment (1006 of 5840 [17.2%]) or did not receive an adjustment (364 of 5840 [6.2%]). Whereas nearly all otolaryngologists reporting data via APMs (936 of 964 [97.1%]) earned bonuses for exceptional performance, fewer than 70% of otolaryngologists reporting data as individuals (1124 of 1990 [56.5%]) or groups (2050 of 3033 [67.6%]) earned such bonuses. Of note, nearly all otolaryngologists incurring penalties (658 of 672 [97.9%]) were affiliated with groups.

Conclusions and Relevance

Most otolaryngologists participating in the 2017 MIPS received performance bonuses, although variation exists within the field. As CMS continues to reform the MIPS and raise performance thresholds, otolaryngologists should consider adopting measures to succeed in the era of value-based care.

Introduction

The Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula was enacted in 1997 to annually update Medicare reimbursement for all physicians.1 While intended to limit growth of Medicare spending, the SGR proved unsustainable in practice and required repeated Congressional overrides to avoid considerable fee cuts. In 2015, Congress passed the bipartisan Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), which replaced the SGR with the value-based Quality Payment Program.2,3 With few exceptions,4 clinicians serving Medicare patients are required to participate in the Quality Payment Program through 1 of 2 tracks: (1) the default track—the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), or (2) an advanced alternative payment model (APM), such as certain types of accountable care organizations (ACOs).5

The MIPS launched in 2017, with more than 1 million clinicians reporting data to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).6 This value-based reimbursement system is intended to individualize clinician fee updates based on performance scores. Clinicians may report MIPS data to CMS as individuals, within groups, or via nonadvanced APMs through several different submission mechanisms (eg, electronic health records or CMS-qualified registries).

The CMS bases MIPS scoring on 4 weighted categories (Table 1): quality, promoting interoperability (formerly “advancing care information”), improvement activities (formerly “clinical practice improvement activities”), and cost.7,8 The CMS subsequently translates performance scores to Medicare Part B payment rate adjustments, which are applied 2 years forward. For example, clinicians received payment rate adjustments in 2019 based on MIPS performance in 2017.

Table 1. Description of Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Category Scoring Metrics.

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Quality |

|

| Promoting interoperabilitya |

|

| Improvement activities |

|

| Cost |

|

Abbreviation: CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Titled “advanced care information” in 2017.

In January 2019, CMS released summary MIPS results from 2017.6,9,10 The first year served as a transition year during which CMS sought to incentivize participation in the MIPS by setting relatively modest performance thresholds (eg, 3 points to avoid penalties). As a result, the vast majority (93.0%) of clinicians received positive payment adjustments (maximum, +1.9%) in 2019. A minority (5.0%) of clinicians elected not to participate and were subject to the maximum penalty (−4.0%). In August 2019, CMS released individual clinician scores from 2017, allowing for more detailed analysis of clinician-level performance.11,12

CMS continues to raise MIPS performance thresholds and payment adjustments. In 2020, clinicians are required to score at least 45 points to avoid penalties (maximum possible, −9%) and at least 85 points to earn bonuses for exceptional performance (maximum possible, +9%).4 However, the influence of MIPS on specialists, such as otolaryngologists, remains unclear.13,14 Understanding how otolaryngologists perform in the MIPS is important to guide policy and practice. We therefore sought to examine otolaryngologist performance in the inaugural year of the MIPS.

Methods

Study Cohort

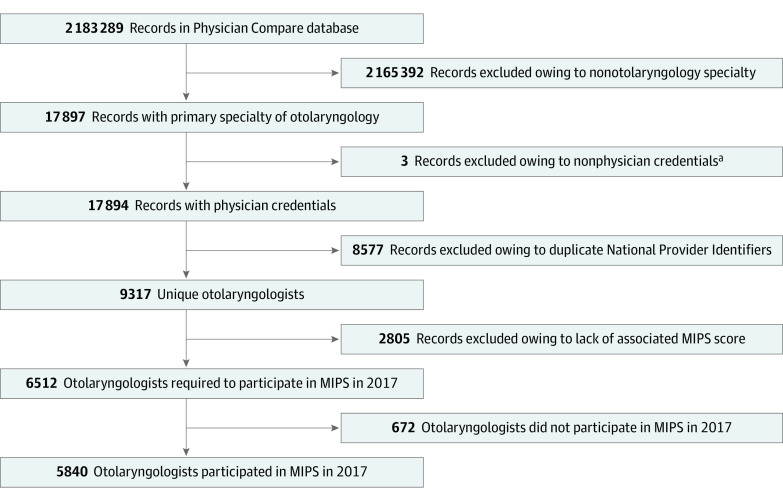

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of otolaryngologist performance in the 2017 MIPS performance period, which was January 1 to December 31, 2017. To identify otolaryngologists required to participate in the MIPS in 2017, we first identified all otolaryngologists serving Medicare beneficiaries as of September 3, 2019, using the publicly available CMS Physician Compare National Downloadable File (Figure 1).15 We classified all clinicians whose primary specialty was listed as otolaryngology within the database as otolaryngologists, excluding those clinicians with nonphysician credentials (eg, physician assistant). We excluded duplicate listings—present for clinicians with multiple practice locations—on the basis of National Provider Identifiers, which are unique for each clinician. Using National Provider Identifiers, we then cross-linked identified otolaryngologists to the publicly available CMS Physician Compare 2017 eligible clinician public reporting database,16 which contains individual clinician MIPS performance scores in 2017.

Figure 1. Construction of Otolaryngologist Cohort Required to Participate in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) in 2017.

aNonphysician credentials include physician assistant degree.

MIPS Participation and Reporting Affiliation

We first estimated the proportion of otolaryngologists required to participate in the MIPS in 2017 as the number of otolaryngologists in our study cohort divided by the number of active otolaryngologists in 2017. We extracted the number of active otolaryngologists in 2017 from the American Association of Medical Colleges 2018 Physician Specialty Data Report.17 Based on overall scores reported within the 2017 MIPS clinician performance database,16 we then categorized otolaryngologists as participants (overall score, >0 points) or nonparticipants (overall score, 0 points).

We then categorized otolaryngologists by their reporting affiliations (individual, group, APM, or other) listed within the 2017 MIPS clinician performance database.16 The APM category includes clinicians participating in APMs who were not exempted from MIPS (eg, clinicians participating in an ACO who received fewer than 50% of their Medicare Part B payments via the ACO).18 Clinicians participating in advanced APMs5,18—defined as models requiring more than nominal performance-based financial risk)—were exempted from MIPS participation. The “other” category included otolaryngologists who requested that CMS re-review their MIPS scores for suspected errors or who selected the minimum participation option (eg, “pick your pace,” available only in 2017).14 We extracted practice sizes for otolaryngologists reporting as individuals, groups, and APM participants from the CMS Physician Compare National Downloadable File.15 We excluded otolaryngologists who fell in the “other” category or selected the minimum participation option from stratified analysis, as CMS did not provide reporting affiliations for these clinicians. We also excluded otolaryngologists with undisclosed practice sizes from our stratified analysis.

MIPS Performance Categories

For clinicians reporting as individuals or within groups, the quality performance category comprised the majority (60%) of MIPS overall scores in 2017. The CMS determined quality scores based on clinician performance on CMS-approved, clinician-selected quality measures (eg, rates of appropriate antibiotic therapy for acute otitis externa [Table 1]). The CMS evaluated quality performance on a curve and calculated scores based on the 6 quality measures on which clinicians score highest.10

The promoting interoperability (25%) and improvement activities (15%) categories accounted for the remainder of MIPS overall scores for clinicians reporting as individuals or groups in 2017. To score in the promoting interoperability category, CMS required clinicians to participate in at least 4 of the 5 following activities: e-prescribing, providing patient access to electronic medical records, requesting or accepting electronic summaries of care, sending electronic summaries of care, and performing an electronic health record security risk analysis.19 The CMS additionally awarded bonus points to clinicians who participated in prespecified activities, such as reporting clinical data via registries. To score in the improvement activities category, CMS required clinicians to participate in up to 4 of more than 90 prespecified activities focused on practice goals, such as health equity, care coordination, and population health management.19

Two technical points merit clarification. First, performance category weighting differed for APM participants by APM type.20 Second, CMS began weighting cost into overall MIPS performance scores in 2018. Cost measures include both episodic and total risk-adjusted Medicare Part A and B spending per attributed beneficiary.

MIPS Performance Scores and Payment Adjustments

We first categorized payment adjustments received by otolaryngologists in accordance with CMS methodology6 as follows: penalty (overall MIPS performance score, <3 points), no payment adjustment (overall MIPS performance score, 3 points), positive adjustment (overall performance MIPS score, >3 and <70 points), or bonus for exceptional performance (overall MIPS performance score, ≥70 points). We then extracted otolaryngologist scores in each 2017 MIPS performance category (eTable in the Supplement): quality, promoting interoperability, and improvement activities.

Statistical Analyses

We used descriptive statistics to characterize otolaryngologist participation, reporting affiliation, and performance in the MIPS in 2017. We examined otolaryngologist performance with respect to payment adjustment, category scores, and overall score, stratified by reporting affiliation and practice size. We performed all analyses in Stata, version 15.0 (StataCorp) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp) between September 3 and November 30, 2019. Institutional review board approval was not required per institutional policy, as this research does not contain animal or human clinical data. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Results

MIPS Participation and Reporting Affiliation

During the 2017 performance period, CMS required more than two-thirds of active otolaryngologists (6512 of 9526 [68.4%]) to participate in the MIPS. The vast majority (5840 of 6512 [89.7%]) participated, and a minority (672 of 6512 [10.3%]) abstained. Otolaryngologists who participated in advanced APMs (eg, the Next Generation ACO model) or fell below the low-volume threshold (billed ≤$30 000 in Medicare Part B allowed charges or served ≤100 Medicare Part B beneficiaries) were exempted from participation.21

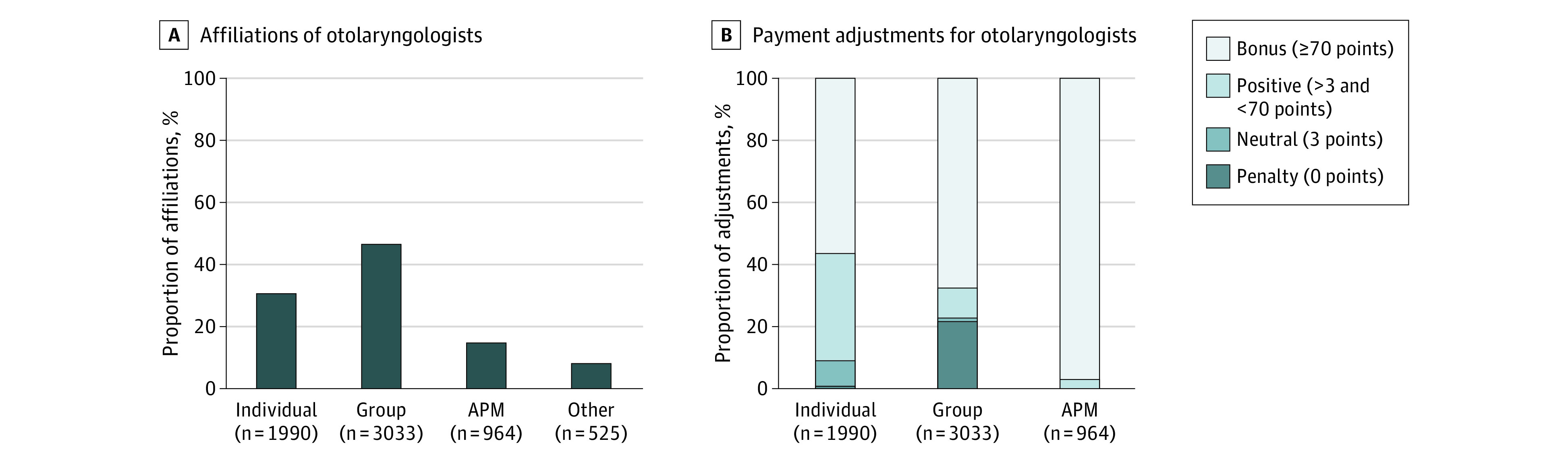

Among the 6512 otolaryngologists required to participate in the MIPS, nearly one-third (1990 [30.6%]) reported data as individuals and nearly one-half (3033 [46.6%]) reported data as groups (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% (964 [14.8%]) participated in MIPS through APMs. The CMS did not provide reporting affiliations for 525 (8.1%) of otolaryngologists in our study cohort.

Figure 2. Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Reported Affiliations and Payment Adjustments for Otolaryngologists, 2017.

A, MIPS reporting affiliation of otolaryngologists in 2017. “Other” category includes clinicians requesting that Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) re-review their MIPS scores for potential errors and clinicians selecting the minimum participation option (eg, “pick your pace,” available only in 2017). The CMS did not provide reporting affiliations for either type of clinician. B, Stacked bar chart comparing MIPS payment adjustments for otolaryngologists in 2017, stratified by reporting affiliation. The 2017 payment adjustments were implemented in 2019. Scores between 0 and 3 points were not possible. APM indicates alternative payment model.

MIPS Performance

In 2017, more than three-quarters of otolaryngologists participating in the MIPS (4470 of 5840 [76.5%]) received bonuses for exceptional performance (Figure 1). The remainder either received a positive payment adjustment (1006 of 5840 [17.2%]) or did not receive an adjustment (364 of 5840 [6.2%]). A minority (672 of 6512 [10.3%]) of otolaryngologists incurred penalties (eg, −4% payment adjustment) for failure to participate in the MIPS.

Payment adjustments varied by reporting affiliation (Figure 2B). Whereas nearly all otolaryngologists reporting data via APMs (936 of 964 [97.1%]) earned bonuses for exceptional performance, fewer than 70% of otolaryngologists reporting data as individuals (1124 of 1990 [56.5%]) or groups (2050 of 3033 [67.6%]) earned such bonuses. Furthermore, nearly all otolaryngologists incurring penalties (658 of 672 [97.9%]) were affiliated with groups.

This variation in payment adjustments reflected differences in overall MIPS performance scores by reporting affiliation (Table 2). Otolaryngologists reporting via APMs earned higher overall scores (median [interquartile range (IQR)], 91.7 [85.9-97.0] points; maximum possible, 100 points) than those reporting as individuals (median [IQR], 74.7 [23.8-88.3] points). This difference was largely driven by higher performance scores in the quality category (median [IQR], APM: 93.9 [86.7-98.8] points; individual: 68.1 [25.0-86.6] points; maximum possible, 100 points). While those reporting within groups had a similar median overall score (92.0 points) compared with those reporting via APMs, group participants had a much wider range (IQR, 15.0-100.0 points). Otolaryngologists reporting via APMs additionally consistently earned higher performance scores with minimal variation in both the promoting interoperability (median [IQR], APM: 89.8 [71.0-97.4] points; individual: 87.0 [0-100.0] points; group: 100.0 [0-100.0] points; maximum possible, 100 points) and improvement activity (median [IQR], APM: 40.0 [40.0-40.0] points; individual: 40.0 [20.0-40.0] points; group: 40.0 [0-40.0] points; maximum possible, 40 points) categories. Of note, clinicians of all reporting affiliations—individual, group, and APM—were able to achieve the maximum score possible within each category and overall.

Table 2. Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Performance Category and Overall Scores for Otolaryngologists in 2017, Stratified by Reporting Affiliation.

| Affiliation | No. | Median, IQR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality (60%)a,b | Promoting interoperability (25%)a,b | Improvement activities (15%)a,b | Overall (100%)b | ||

| Individual | 1990 | 68.1 (25.0-86.6) | 87.0 (0-100.0) | 40.0 (20.0-40.0) | 74.7 (23.8-88.3) |

| Group | 3033 | 91.4 (0-100.0) | 100.0 (0-100.0) | 40.0 (0-40.0) | 92.0 (15.0-100.0) |

| APMc | 964 | 93.9 (86.7-98.8) | 89.8 (71.0-97.4) | 40.0 (40.0-40.0) | 91.7 (85.9-97.0) |

Abbreviations: APM, alternative payment model; IQR, interquartile range; MSSP, Medicare Shared Savings Program.

Parenthetical percentages denote category weight for determination of overall score. Category weights differed for APM participants and by APM type.

The maximum possible score for the improvement activities category was 40 points; the maximum quality, improvement activities, and overall scores were 100 points.

APMs are models of payment in which financial risk is accepted for care provided. Examples includeMSSP accountable care organization and Next Generation Accountable Care Organization models.

Among otolaryngologists reporting as individuals or groups, performance in the MIPS varied by practice size (Table 3). Otolaryngologists in small practices (eg, <15 physicians) earned among the lowest overall performance scores (median [IQR], individual: 71.2 [16.3-86.1] points; group: 9.0 [0-92.3] points). These otolaryngologists accounted for the majority of those reporting as individuals (1370 of 1956 [70.0%]) and the plurality of those reporting as groups (1123 of 2983 [37.6%]). Low performance was primarily driven by low quality (median [IQR], individual: 63.1 [15.0-83.5] points; group: 0 [0-96.3] points) and improvement activities (median [IQR], individual: 85.0 [0-99.0] points; group: 0 [0-93.0] points) scores. Of note, otolaryngologists reporting as individuals from within large practices (eg, >500 clinicians) earned low overall performance scores (median [IQR], 59.4 [6.7-82.7] points) as well. In contrast, otolaryngologists reporting via APMs earned consistently higher overall performance scores whether reporting from small practices (<15 clinicians; median [IQR], 85.9 [82.4-88.9] points) or large practices (>500 clinicians; median [IQR], 95.9 [88.4-98.5] points).

Table 3. Otolaryngologists’ 2017 Merit-Based Incentive Payment System Performance, Stratified by Practice Sizea.

| Clinicians, No. | No. (%) | Median (IQR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality | Advanced care information | Improvement activities | Final | ||

| Individual | |||||

| <15 | 1370 (70.0) | 63.1 (15.0-83.5) | 85.0 (0-99.0) | 40.0 (0-40.0) | 71.2 (16.4-86.1) |

| 15-50 | 313 (16.0) | 77.9 (56.9- 90.7) | 90.0 (0-100.0) | 40.0 (20.0-40.0) | 80.3 (53.5-90.2) |

| 51-100 | 68 (3.5) | 78.0 (59.1-86.2) | 100.0 (92.0-100.0) | 40.0 (40.0-40.0) | 85.3 (71.1-91.2) |

| 101-500 | 163 (8.3) | 78.5 (56.0-92.7) | 90.0 (0-100.0) | 40.0 (40.0-40.0) | 81.3 (64.7-92.4) |

| >500 | 42 (2.1) | 55.6 (5.0-80.2) | 86.0 (0-99.0) | 40.0 (0-40.0) | 59.4 (6.7-82.7) |

| Group | |||||

| <15 | 1123 (38.4) | 0 (0-96.3) | 0 (0-93.0) | 0 (0-40.0) | 9.0 (0-92.3) |

| 15-50 | 376 (11.5) | 91.6 (76.0-100.0) | 99.0 (73.0-100.0) | 40.0 (40.0-40.0) | 91.8 (75.0-96.5) |

| 51-100 | 251 (8.1) | 70.0 (44.8-93.1) | 100.0 (96.0-100.0) | 40.0 (40.0-40.0) | 81.0 (66.9-95.9) |

| 101-500 | 643 (21.8) | 100.0 (89.2-100.0) | 100.0 (100.0-100.0) | 40.0 (40.0-40.0) | 100.0 (92.5-100.0) |

| >500 | 590 (20.2) | 97.9 (89.4-100.0) | 100.0 (100.0-100.0) | 40.0 (40.0-40.0) | 98.4 (93.0-100.0) |

| Alternative payment model | |||||

| <15 | 191 (20.2) | 97.7 (88.5-98.2) | 56.1 (54.3-76.2) | 40.0 (40.0-40.0) | 85.9 (82.4-88.9) |

| 15-50 | 92 (9.2) | 92.7 (86.5-97.6) | 87.1 (71.1-96.9) | 40.0 (40.0-40.0) | 91.3 (85.6-96.0) |

| 51-100 | 45 (4.5) | 88.9 (84.5-96.2) | 89.8 (71.0-97.8) | 40.0 (40.0-40.0) | 91.2 (84.5-95.4) |

| 101-500 | 241 (25.4) | 95.8 (87.5-100.0) | 96.4 (79.1-100.0) | 40.0 (40.0-40.0) | 94.1 (89.5-98.6) |

| >500 | 388 (40.7) | 96.4 (86.5-100.0) | 95.9 (76.1-97.4) | 40.0 (40.0-40.0) | 95.9 (88.4-98.5) |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services–designated practice size denotes number of clinicians within organization.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that CMS required more than two-thirds of active otolaryngologists to participate in the MIPS in 2017. The majority of these otolaryngologists did participate, reporting data as individuals or groups; a small proportion participated via APMs. Although the majority of participating otolaryngologists received payment bonuses for exceptional performance in 2017, there was significant variation within the field. Whereas nearly all otolaryngologists reporting via APMs received bonuses for exceptional performance, a lower proportion of otolaryngologists reporting as individuals or groups received bonuses. Otolaryngologists reporting as individuals or groups from small practices earned lower overall scores in particular.

To our knowledge, our study is the first of otolaryngologist participation and performance in the MIPS and of value-based reimbursement programs. Although much remains unknown about clinician performance in the MIPS, our results are broadly consistent with preliminary results released by CMS and analogous studies of radiologists and dermatologists.6,14,22 These analyses indicate that physicians performed well overall in the inaugural year of the MIPS, in which CMS set low scoring thresholds to encourage participation. Furthermore, performance in the field of radiology varied in a similar manner, with APM participants earning high scores while physicians in small practices fared worse overall.14

Although otolaryngologists fared well in the MIPS in 2017, past performance may not guarantee future success. The CMS has continued to raise both performance thresholds and financial stakes following this transitional year. In 2020, clinicians must earn at least 45 points (vs 3 points in 2017) to avoid penalties and 85 points (vs 70 points in 2017) to earn bonuses for exceptional performance. Payment adjustments range from −9% to +9% (vs −4% to +4% in 2017), although CMS anticipates that the maximum bonus will be lower owing to MACRA budget-neutrality requirements.23 These rules may prove particularly problematic for the field of otolaryngology, as more than half of all otolaryngologists belong to solo or small group practices.24

There are several strategies these otolaryngologists should consider to enhance MIPS performance moving forward. First, otolaryngologists may join MIPS virtual groups, which were introduced by CMS in 2018 and permit data pooling by up to 10 clinicians from similar practices.25 Forming virtual groups may help otolaryngologists improve quality category scores by reducing performance variation and fulfilling minimum case requirements. Second, otolaryngologists could begin participating in clinical data registries to earn bonus points while fulfilling requirements for the promoting interoperability category.10 Registry data from the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) suggest that many otolaryngologists have already adopted this strategy. Between 2017 and 2020, the number of clinicians participating in the AAO-HNSF clinical data registry nearly tripled from approximately 700 to more than 2000.26 Third, otolaryngologists in solo or small group practices could seek employment by or affiliation with hospital-based health systems or large physician group organizations that are well positioned to deliver value-based care.27

Organizations participating in APMs may be particularly attractive for otolaryngologists seeking to perform well in the MIPS. These organizations already possess the care management infrastructure necessary to report quality data and satisfy requirements for promoting interoperability and improvement activities.28,29 Furthermore, these organizations have valuable experience with CMS pay-for-performance schemes, such as expertise quality measure selection and process improvements.30 Finally, otolaryngologists joining these organizations may be exempted from quality reporting altogether. For example, consider otolaryngologists employed by organizations participating in track 1 of the Medicare Shared Savings Program, which does not require ACOs to assume downside financial risk and has been the most popular track to date.31 These otolaryngologists are not required to report MIPS quality data because CMS scores ACO quality largely based on primary care–focused measures.32

As otolaryngologists endeavor to perform under the MIPS, CMS should consider policy reforms to better ensure that the program promotes high-value specialty care. For instance, although CMS began awarding bonus points to small practices (<15 clinicians) in 2018, this reward is relatively modest (maximum overall, 2.7 points ).33 Our findings suggest that CMS should consider offering additional relief to small practices navigating the transition to value-based care. In addition, CMS should work with the AAO-HNSF to accelerate the development of additional quality measures relevant to the practice of otolaryngology.13 In 2017, the AAO-HNSF was the primary steward for 6 of 271 quality measures included in the MIPS; in 2019, 8 of 268 quality measures were unique to otolaryngologists.19 The CMS recently finalized plans to collaborate with clinicians and specialty societies in the creation of MIPS Value Pathways, which may help meaningfully link quality reporting to physician practice.34 Finally, CMS should provide otolaryngologists reporting “bottomed-out” quality measures (eg, referral to an otologist for acute or chronic dizziness)35 the opportunity to retroactively report alternative measures. Without such reform, otolaryngologists will automatically receive minimum scores (3 of 10 possible points for each bottomed-out measure) simply because not enough clinicians reported these measures.10

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. We may underestimate the proportion of otolaryngologists required to participate in the MIPS in 2017, as our study cohort does not include otolaryngologists who stopped serving Medicare beneficiaries prior to September 3, 2019 (eg, recently retired otolaryngologists). However, this would likely comprise a small subset of otolaryngologists with practice patterns of lesser relevance to future MIPS performance. Additionally, our performance analysis excludes individuals who requested CMS re-review their MIPS scores for suspected errors and may therefore not be generalizable to all otolaryngologists, although this excluded cohort was small. Third, the present analysis is limited to 2017 MIPS performance, which may lack generalizability as the program continues to evolve (eg, following inclusion of the cost performance category).

Conclusions

CMS required more than two-thirds of active otolaryngologists to participate in the inaugural year (2017) of the MIPS. The majority of otolaryngologists participated and earned bonuses for exceptional performance, although there was substantial variation within the field. As CMS continues to reform the MIPS and raise performance thresholds, otolaryngologists should consider adopting measures to succeed in the era of value-based care.

eTable. Summary of Major Changes to MIPS From 2017 to 2020

References

- 1.Aaron HJ. Three cheers for logrolling—the demise of the SGR. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):1977-1979. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1504076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McWilliams JM. MACRA: big fix or big problem? Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(2):122-124. doi: 10.7326/M17-0230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nuckols TK. With the merit-based incentive payment system, pay for performance is now national policy. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(5):368-369. doi: 10.7326/M16-2947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CY 2020 Medicare Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System and Ambulatory Surgical Center Payment System Final Rule (CMS-1717-FC). Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/cy-2020-medicare-hospital-outpatient-prospective-payment-system-and-ambulatory-surgical-center-0

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services The Quality Payment Program. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/quality-payment-program

- 6.Verma S. Quality Payment Program (QPP) year 1 performance results. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/blog/quality-payment-program-qpp-year-1-performance-results

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS)—scoring 101 guide for the 2017 performance period. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/74/MIPS%20Scoring%20101%20Guide_Remediated%202018%2001%2017.pdf

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS)—101 user guide for the 2018 performance period. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/307/2018%20MIPS%20101%20User%20Guide_Remediated_2018%2012%2017.pdf

- 9.Quality Insights CMS releases 2017 Quality Payment Program performance results. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://qppsupport.org/News/CMS-Releases-2017-Quality-Payment-Program-Performa.aspx

- 10.Rathi VK, McWilliams JM. First-year report cards from the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS): what will be learned and what next? JAMA. 2019;321(12):1157-1158. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quality Insights 2017 MIPS scores are now available on Physician Compare. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://qppsupport.org/News/2017-MIPS-Scores-Are-Now-Available-on-Physician-Co.aspx

- 12.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2017 Quality Payment Program reporting experience. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/491/2017 QPP Experience Report.pdf

- 13.Rathi VK, Naunheim MR, Varvares MA, Holmes K, Gagliano N, Hartnick CJ. The Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS): a primer for otolaryngologists. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159(3):410-413. doi: 10.1177/0194599818774033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenkrantz AB, Duszak R Jr, Golding LP, Nicola GN. The Alternative Payment Model pathway to radiologists’ success in Merit-Based Incentive Payment System. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(4):525-533. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Physician Compare national downloadable file. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://data.medicare.gov/Physician-Compare/Physician-Compare-National-Downloadable-File/mj5m-pzi6

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Physician Compare 2017 individual EC public reporting—measures. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://data.medicare.gov/Physician-Compare/Physician-Compare-2017-Individual-EC-Public-Report/93x5-v9gz

- 17.Association of American Medical Colleges 2018 Physician specialty data report. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-largest-specialties-2017

- 18.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMS). Accessed April 16, 2020. https://qpp.cms.gov/apms/advanced-apms?py=2017

- 19.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Explore measures & activities. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/explore-measures/quality-measures

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services MIPS Alternative Payment Models (APMs). Accessed April 16, 2020. https://qpp.cms.gov/apms/mips-apms

- 21.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services MIPS participation fact sheet. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://qpp.cms.gov/resource/2017 MIPS determination segments

- 22.Gronbeck C, Feng PW, Feng H. Participation and performance of dermatologists in the 2017 Merit-Based Incentive Payment System. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(4):466-468. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 42 CFR parts 403, 409, 410, 411, 414, 415, 416, 418, 424, 425, 489, and 498. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2019-24086.pdf

- 24.American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 13th socioeconomic survey. May 2014. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.entnet.org/sites/default/files/AAOHNS_2014_Socioeconomic_Survey.pdf

- 25.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Individual or group participation. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/individual-or-group-participation

- 26.American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery About Reg-ent. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.entnet.org/about-reg-ent

- 27.Miller LE, Rathi VK, Naunheim MR. Implications of private equity acquisition of otolaryngology physician practices. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(2):97-98. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.3738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Academy of Family Physicians Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Alternative Payment Models (APMs), or MIPS APMs. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.aafp.org/practice-management/payment/medicare-payment/mips-apms.html

- 29.Navathe AS, Liao JM. MIPS APMs in the Quality Payment Program [published online October 31, 2018]. Health Aff (Millwood). doi: 10.1377/hblog20181030.290056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Report to Congress—Alternative Payment Models & Medicare Advantage. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Advantage/Plan-Payment/Downloads/Report-to-Congress-APMs-and-Medicare-Advantage.pdf

- 31.Mechanic R, Gaus C. Medicare Shared Savings Program produces substantial savings: new policies should promote ACO growth [published online September 11, 2018]. Health Aff (Millwood). doi: 10.1377/hblog20180906.711463 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Quality measurement methodology and resources. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/quality-measurement-methodology-and-resources.pdf

- 33.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS)—scoring 101 guide for year 2 (2018). Accessed April 16, 2020. https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/179/2018%20MIPS%20Scoring%20Guide_Final.pdf

- 34.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs). Accessed April 16, 2020. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/mips-value-pathways

- 35.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2017 quality benchmarks. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/78/2017 - Quality Benchmarks.zip

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Summary of Major Changes to MIPS From 2017 to 2020