Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

We have addressed comments from the reviewers and made the following changes The type of sampling is specified as opportunistic sampling and was adopted for convenience by sampling camels from diverse geographical locations as they converge at specific water drinking points. Otherwise it will be challenging to conduct daily sampling of camels considering that camel owners are nomadic pastoralists with busy lifestyles characterized by long distance movements together with their animals and other belongings. Other minor changes include; Throughout the article, “disease pathogens” was changed to read to “pathogens”, Absolute fractions in the results section of the abstract were removed, Edits such as rephrasing some statements was done, e.g. “unpredictable rainfalls” was changed to “unpredictable rainfall”; “short and long rains” to “short and long wet seasons”, Table 3 (Biting flies were trapped…) is edited as follows; new column inserted showing the number days sampled; column heading “Fly density per trap/day” changed to “Daily fly captures”, New addition; Figure 5: Pairwise alignment of 16S rRNA sequences of “ Candidatus Anaplasma Camelii” amplified from camel blood sample 60D with GenBank-retrieved nucleotide sequence (KF843824) showed 100% identity. N is ambiguous nucleotide. The following citations have been added to the current version; Rahola et al., 2011, Nelson, 1963, Moore and Messina, 2010, Vanhollebeke et al., 2006, Truc et al., 2013

Abstract

Background: Major constraints to camel production include pests and diseases. In northern Kenya, little information is available about blood-borne pathogens circulating in one-humped camels ( Camelus dromedarius) or their possible transmission by the camel haematophagous ectoparasite, Hippobosca camelina, commonly known as camel ked or camel fly. This study aimed to: (i) identify the presence of potentially insect-vectored pathogens in camels and camel keds, and (ii) assess the potential utility of keds for xenodiagnosis of camel pathogens that they may not vector.

Methods: In Laisamis, northern Kenya, camel blood samples (n = 249) and camel keds (n = 117) were randomly collected from camels. All samples were screened for trypanosomal and camelpox DNA by PCR, and for Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, Brucella, Coxiella, Theileria, and Babesia by PCR coupled with high-resolution melting (PCR-HRM) analysis.

Results: In camels, we detected Trypanosoma vivax (41%), Trypanosoma evansi (1.2%), and “ Candidatus Anaplasma camelii” (68.67%). In camel keds, we also detected T. vivax (45.3%), T. evansi (2.56%), Trypanosoma melophagium (1/117) (0.4%), and “ Candidatus Anaplasma camelii” (16.24 %). Piroplasms ( Theileria spp. and Babesia spp.), Coxiella burnetii, Brucella spp., Ehrlichia spp., and camel pox were not detected in any samples.

Conclusions: This study reveals the presence of epizootic pathogens in camels from northern Kenya. Furthermore, the presence of the same pathogens in camels and in keds collected from sampled camels suggests the potential use of these flies in xenodiagnosis of haemopathogens circulating in camels.

Keywords: Camelus dromedarius, Hippobosca camelina, haemopathogens, xenodiagnosis, high-resolution melting analysis

Introduction

Camels are the most valuable livestock for pastoralist farmers living in arid and semi-arid lands (ASALs) in Kenya ( Mochabo et al., 2005). Among other benefits, they provide milk, meat, transport, and income through sale of animal products ( Faye, 2014; Oryan et al., 2008). There are no other livestock species that have such versatile uses to pastoralists living in ASALs ( Faye, 2014). Over three million one-humped camels are estimated to be in northern Kenya ( FAOSTAT, 2015; KNBS, 2010), which represents the third largest camel population in Africa after Somalia and Sudan ( Lamuka et al., 2017). Camels are resilient to harsh conditions of ASAL regions characterized by long periods of drought, scarcity of vegetation and water, and unpredictable rainfall. However, camel pests and diseases are the major constraints to camel production ( Higgins, 1985; Kassa et al., 2011; Mochabo et al., 2005). Additionally, the constant association between camels and humans, co-herding of livestock species, and communal watering of animals, as well as sharing of water troughs by the domestic and wild animals, exacerbate the spread of zoonotic diseases, which poses a great risk to public health among livestock and humans in Kenya’s north ( Bengis et al., 2002; Kazoora et al., 2014; Lamuka et al., 2017; Younan & Abdurahman, 2014). Thus, there is a need for constant surveillance of infectious agents circulating within the camel herds in order to guide control and treatment of these diseases.

Camels are vertebrate hosts of various haematophagous arthropods including Hippobosca spp. (also known as keds or hippoboscids), horse flies, stable flies, Lyperosia spp., and ticks ( Higgins, 1985). In addition to the direct effects such as blood loss, annoyance, and painful feeding bites, these biting pests can be vectors of infectious pathogens ( Baldacchino et al., 2013; Higgins, 1985; Young et al., 1993). Biting flies such as tabanids and Stomoxys have been implicated in the transmission of viruses (including bluetongue and Rift Valley fever viruses), rickettsiae (e.g. Anaplasma, Coxiella), Bacillus anthracis, and protozoa ( Besnoitia besnoiti, Haemoproteus metchnikovii, Trypanosoma theileri, Trypanosoma evansi, Trypanosoma equiperdum, Trypanosoma vivax, Trypanosoma congolense, Trypanosoma simiae, Trypanosoma brucei) in their specific vertebrate hosts (reviewed by Baldacchino et al., 2013).

Hippoboscids (keds) are obligate haematophagous ectoparasites of mammals and birds. They belong to the family Hippoboscidae within the superfamily Hippoboscoidae ( Petersen et al., 2007; Rahola et al., 2011). This family of haematophagous dipterans is divided into three subfamilies, Lipopteninae, Ornithomyinae, and Hippoboscinae ( Rani et al., 2011). Hippoboscidae and Glossinidae (tsetse; i.e. the definitive vector of African trypanosomes) belong to the same superfamily Hippoboscoidae, which is characterized by adenotrophic viviparity ( Petersen et al., 2007). Members of Hippoboscidae act as vectors of several infectious agents including protozoa, bacteria, helminths, and viruses ( Rahola et al., 2011). Hippobosca camelina is the predominant ectoparasite of camels in northern Kenya. This haematophagous fly acquires blood meals mainly from camels for its nourishment and reproduction. The role of keds in disease transmission is not well established. Furthermore, as primarily long-term camel blood-feeders, they may have potential in xenosurveillance of pathogens within camel herds that they may not transmit. Therefore, this study was undertaken to (i) detect the presence of infectious viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and rickettsial pathogens, particularly those responsible for zoonoses, in camels and hippoboscids associated with them, and (ii) study the potential utility of hippoboscids in xenodiagnosis.

Methods

Study area

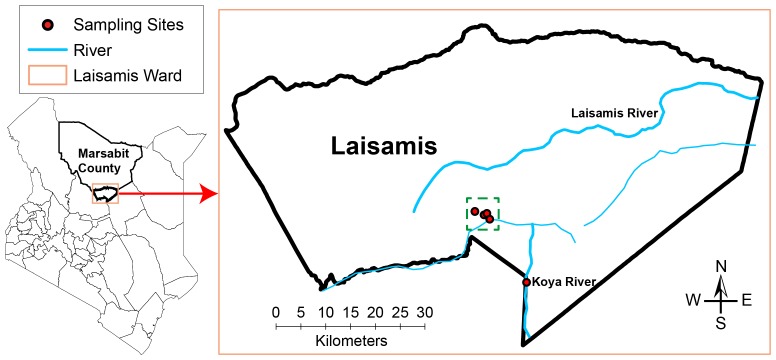

The study was carried out in Laisamis (1° 36' 0" N 37° 48' 0" E, 579 m above sea level) located in Marsabit County, northern Kenya ( Figure 1). The County of Marsabit in Kenya has a total area of 70,961km 2 and occupies the extreme part of northern Kenya (Source: County Commissioner’s Office, Marsabit, 2013). Area of the Laisamis sub-County that consists of four County Assembly Wards is 20,290 km 2 with a population of 84,056 people consisting of about 41,240 males and 42,871 females ( KNBS, 2013). Laisamis electoral ward, one of the four County Assembly Wards of Laisamis sub-County in Marsabit County, has an area of 3,885 km 2. A total population of 203,320 camels was reported in Marsabit County, where our present study was conducted ( SSFR, 2017).

Figure 1. A map of Kenya showing the study sites in Laisamis, Marsabit County, Kenya.

Camel blood samples were collected from camel herds during the day, shortly after drinking water from the wells dug along Koya semi-permanent river (circle filled in red), whereas camel keds were collected from the same herds later at night when these camels returned to their temporary settlements shown on the map by circles (filled in red) inside a dotted green square.

Weather conditions

The average temperature in Laisamis is 26.5°C (19°C – 30°C; March is the warmest month, whereas July is the coldest month of the year). About 413 mm of precipitation falls annually, the average rainfall amounts and rain days differ between years. Long wet seasons occur mostly during April - June, while short wet seasons are experienced in October - December. On the other hand, short dry seasons occur between January and March, whereas long dry spells are experienced between July and September ( SSFR, 2017). However, unpredictable and irregular climatic patterns are becoming more common, with no rainfall in some years leading to frequent droughts in the arid and semi-arid regions of northern Kenya.

Study design and sample collection

This field study was cross-sectional in design and involved opportunistic sampling of camels from diverse geographical locations as they converge at specific water drinking points. Daily sampling of camels found along the river was convenient strategy considering that camel owners are nomadic pastoralists with busy lifestyles characterized by long distance movements together with their animals and other belongings.

Due lack of historical data on camel diseases in Laisamis sub-County, there was no basis for calculation of the sample sizes, thus we collected as many samples as possible during the sampling duration.

We did not have data on the total number of camel herds kept by the pastoralist community whose main occupation at 87% is livestock herding ( SSFR, 2017). We defined camel herd as a group of camels that spend significant amount of time together by living, feeding, or migrating together. Camels in each herd ranged from 8 – 90 camels.

Camel blood samples

In September 2017, 249 clinically healthy dromedary camels of both sexes (203 females and 46 males) were sampled in Laisamis sub-County, along Koya River (01° 23’ 11” N, 37° 57' 11.7" E). Koya River was selected as sampling site as it contains permanent watering points. Sampling was preferred in dry season of September when the camel ked densities are highest in contrast to the wet season. We sampled all camels in each and every herd at water drinking points for five consecutive days.

About 5 mL of camel blood was drawn from jugular vein into a heparinised vacutainer and immediately preserved in liquid nitrogen at -196°C for transportation to molecular biology laboratories at the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology ( icipe, Nairobi) for analysis.

Collection of camel keds, H. camelina

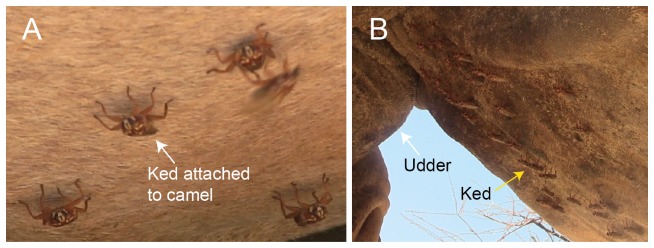

Camel keds closely associate and move with their host as they firmly attach to the hairs on camel’s skin using tarsal claws. These blood feeders are mainly observed on the underbelly ( Figure 2), although they can be found on other parts of the body such as the neck and hump. Since we observed that keds are best collected under the cover of darkness at night, we collected blood samples at the water drinking point, then later in the evening followed the same camel herds for fly collection. Flies were collected off camels from four sites (Sarai – 01° 30’ 33.2” N, 037° 52’ 34.4” E; Sarai Maririwa/Kilakir – 01° 35’ 20.5” N, 037° 48’ 39.7” E; Lapikutuk Lelembirikany’ – 01° 30’ 42.9” N, 037° 52’ 53.5” E; Noldirikany’ – 01° 30’ 04.2” N, 037° 54' 50.7" E) by handpicking using spotlights that were briefly switched on and off in order to locate flies on the camels. Camel keds were randomly collected from 21 sampled camel herds in 5 days and we aimed to collect all camel flies found on the camel’s body in all sampled herds. Freshly collected camel keds were preserved in absolute isopropanol and transported to icipe for molecular screening of infectious agents. Morphological identification of camel keds was done through comparison with known hippoboscid collections at the Zoology museum of the University of Cambridge (UK), and the Natural History Museum in London. DNA barcoding of COI gene to resolve species of keds was unsuccessful possibly because these flies are little studied and have poor representation in the databases.

Figure 2. Hippobosca camelina flies infesting camels.

These ectoparasites are mostly found on the belly of the host as shown in A & B. Over 30 flies were found concentrated on a small section of underbelly of the camel next to the udder. These flies mostly infest the underbelly and occasionally on the other parts of the camel’s body where they are not prone to disturbance by the host.

Collection of other biting flies

In order to determine occurrence of tsetse flies and other species of haematophagous biting flies found in Laisamis sub-County and Koya, we deployed monoconical traps, using cow urine and acetone as attractants. Three traps were deployed per site on daily basis from 09:00 - 18:00 next to livestock pens and near watering points along Laisamis River. The inter-trap distance was at least 100 meters. Daily trap collections were pooled, fly species sorted, counted, and then the flies were preserved in 50 mL Falcon tubes half-filled with absolute ethanol for later morphological identification.

Ethical approval

This study was undertaken in strict adherence to experimental guidelines and procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at icipe (REF: IACUC/ICIPE/003/2018). All efforts were made to minimize pain and discomfort during sampling. For instance, camel keepers, with whom camels were familiar, were allowed to restrain their camels for sample collection. Samples were collected after receiving informed verbal consent from camel keepers. All camel keepers were neither able to read nor write, thus verbal rather than the written consent was adopted as the pragmatic approach.

DNA extraction

Each H. camelina fly was surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol and allowed to air dry for 10 min on a paper towel on top a clean bench. Individual flies were placed into a clean 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes containing sterile 250 mg of zirconia beads with 2.0 mm diameter (Stratech, UK) and ground in liquid nitrogen in a Mini-Beadbeater-16 (BioSpec, Bartlesville, OK, USA) for 3 min. Genomic DNA was extracted from camel keds and camel blood samples using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Detection of pathogen DNA

Detection of Coxiella burnetii, Anaplasma spp., Ehrlichia spp., Brucella spp., and piroplasms belonging to Theileria and Babesia genera employed PCR followed by DNA fragment analysis based on high-resolution melting (HRM) analysis ( Šimenc & Potočnik, 2011) in a Rotor-Gene Q thermocycler (Qiagen, German). Coxiella burnetii DNA was screened for using primers ( Table 1) targeting the IS1111 gene ( Tokarz et al., 2009). Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species were detected by PCR amplification using genus-specific primers ( Table 1). In detection of Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species, the PCR-HRM target for 16S rRNA lies within the longer 16S rRNA region, thus the 1000 bp barcode region (amplified by conventional PCR) instead of 16S rRNA HRM products were sequenced. Babesia and Theileria spp. DNAs were amplified using primers RLB-F1 and RLB-R1 ( Table 1) targeting the hypervariable V4 region of 18S rRNA genes ( Georges et al., 2001). The PCRs were carried out in 10 μL reaction volumes, containing 2.0 μL of 5× HOT FIREPol EvaGreen HRM mix (no ROX) (Solis BioDyne, Estonia), 0.5 μL of 10 pmol of each primer, 6.0 μL PCR water and 1.0 μL of template DNA. For Brucella spp., the reactions were carried out in 10 μL reaction volumes, containing 2.0 μL of 5× HOT FIREPol EvaGreen HRM mix (no ROX) (Solis BioDyne, Estonia), and 0.5 μL of 10 pmol of each primer of three primers; Brucella arbutus forward primer, B. melitensis forward primer, and Brucella spp. universal reverse primer targeting the IS711 gene ( Probert et al., 2004), 5.5 μL PCR water and 1.0 μL of template DNA. PCR amplification was preceded by an initial enzyme activation at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 10 cycles at 94°C for 20 sec, step-down annealing from 63.5°C with decrements of 1°C after each cycle for 25 sec, and primer extension step at 72°C for 30 sec; then 25 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 25 sec, annealing at 50.5°C for 20 sec, and extension at 72°C for 30 sec followed by a final elongation at 72°C for 7 min. Immediately after PCR, HRM profiles of amplicons were obtained by increasing temperature gradually from 75 to 90°C at 0.1°C/2 sec increments. Changes in fluorescence with time (dF/dT) were plotted against changes in temperature (°C).

Table 1. Primers for amplification of target genes for detection of disease-causing camel pathogens.

Primers sequences were sent to inqaba biotec™ (Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa) for synthesis.

| Primer name | 5’to 3’ sequence | Target

organism |

Target gene | Product

size (bp) |

References for primers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS1111F

IS1111F |

GTA ATA TCC TTG GGC GTT GAC G

ATC TAC GCA TTT CAC CGC TAC AC |

C. burnetii |

Coxiella 16S

rRNA |

242 | ( Doosti et al., 2014) |

|

AnaplasmaJV

F

AnaplasmaJV R |

CGGTGGAGCATGTGGTTTAATTC

CGRCGTTGCAACCTATTGTAGTC |

Anaplasma spp. |

Anaplasma

16S rRNA |

300 | ( Mwamuye et al., 2017) |

|

EhrlichiaJV F

EhrlichiaJV R |

GCAACCCTCATCCTTAGTTACCA

TGTTACGACTTCACCCTAGTCAC |

Ehrlichia spp. |

Ehrlichia 16S

rRNA |

300 | ( Mwamuye et al., 2017) |

| EHR16SD

1492R |

GGTACCYACAGAAGAAGTCC

GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT |

Ehrlichia & Anaplasma spp. | 16S rRNA | 1000 | (

Parola

et al., 2000;

Reysenbach et al., 1992) |

| RLB F

RLB R |

GAGGTAGTGACAAGAAATAACAATA

TCTTCGATCCCCTAACTTTC |

Theileria &

Babesia spp. |

Theileria &

Babesia 18S rRNA |

450 | |

| CMLVC18LF

CMLVC18LR |

GCGTTAACGCGACGTCGTG

GATCGGAGATATCATACTTTACTTTAG |

Camel pox virus | C18L gene | 243 | ( Balamurugan et al., 2009) |

|

B. arbutus F

B. melitensis F Brucella IS711T R |

GCGCTCAGGCTGCCGACGCAA

GCGGCTTTTCTATCACGGTATTC GGGTAAAGCGTCGCCAGAAG |

Brucella spp | IS711 | ( Probert et al., 2004) | |

| ITS1_CF

ITS1_BR |

CCGGAAGTTCACCGATATTG

TTGCTGCGTTCTTCAAC- GAA |

Trypanosoma

spp. |

ITS1 | 250-720 | ( Njiru et al., 2005) |

| ILO 7957F

ILO 8091R |

GCCACCACGGCGAAAGAC

TAATCAGTGTGGTGTGC |

T. evansi | RoTat 1.2 | 488 | ( Urakawa et al., 2001) |

Screening of pathogenic animal African trypanosomes and camelpox virus was done by PCR in a ProFlex thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). Trypanosome DNA was amplified by targeting trypanosomal internal transcribed spacer region using the following universal primer sets described by Njiru et al. (2005); ITS1_CF and ITS1_BR ( Table 1) in 10 µL PCR volumes containing 0.1 units of Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland), 2 µL of 5× HF buffer, 0.2 µL of 10 mM dNTPs, 0.2 µL of 10 mM of each primer and 6.3 µL of nuclease free water. The PCR conditions were as follows: 98°C for 1 min, 40 cycles of 98°C for 30 sec, 61°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 45 sec, with a final elongation step of 7 min at 72°C. Camelpox virus C18L gene was amplified using CMLV C18LF and CMLV C18LR primers described by Balamurugan et al. (2009). The PCRs were carried out in a 10-µL reaction mixtures containing 5.0 µL of DreamTaq Green PCR master mix (2×) (Thermo Scientific), 0.5 µL of 10 mM of each primer, 1.0 µL of DNA template, and 3.0 µL of nuclease-free water. The PCR thermocycling conditions included; initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 58°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec followed with a final elongation of 72°C for 5 min. The PCR amplicons were electrophoresed on 1.5% ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel and visualized under ultraviolet light.

DNA purification and sequencing

Representative positive samples producing distinct amplicons with expected band sizes relative to the known positive DNA controls were selected for amplification in larger PCR reaction volumes (30-μL). The PCR amplicons were separated by electrophoresis in ethidium bromide-stained 1.5% agarose gels and visualized under ultraviolet light. The target bands were excised and gel purified using QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The purified amplicons were sent to Macrogen Inc. (Netherlands) for Sanger sequencing.

Since it is not possible to resolve the trypanozoon species using ITS1 primers, which give 480-bp PCR product sizes ( Njiru et al., 2005), two samples positive for Trypanozoon, one from camel and the other from hippoboscid, were amplified using ILO 7957F and ILO 8091R primers ( Table 1) targeting RoTat 1.2 VSG gene described by Urakawa et al. (2001).

To identify the Anaplasma species associated with the HRM peaks observed, amplicons of two samples positive for Anaplasma spp., one from camels and one from camel ked, were selected for sequencing using AnaplasmaJVF and AnaplasmaJVR targeting 300-bp of Anaplasma 16S rRNA genes. These primers could not resolve Anaplasma to species level. To resolve the Anaplasma to species level, a longer 1000-bp fragment of Anaplasmataceae 16S rRNA gene was further amplified by conventional PCR using published primers EHR16SD and 1492R ( Parola et al., 2000; Reysenbach et al., 1992, Table 1), and sequenced. The PCR amplifications were performed in a ProFlex PCR system (Applied Biosystems by life technologies) with the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 15 min; two cycles of 95°C for 20 sec, 58°C for 40 sec, and 72°C for 90 sec; three cycles of 95°C for 20 sec, 57°C for 30 sec, 35 cycles of 95°C for 20 sec, 56°C for 40 sec and 72°C for 90 sec, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min ( Bastos et al., 2015).

Sequences obtained in the study were deposited in GenBank database with the following accession numbers: short 16S rRNA of Anaplasma spp. in camel (MN306317) and camel ked (MN306316); full length 16S rRNA of “ Candidatus Anaplasma camelii” (MN306315), T. vivax ITS1 in camel (MK880188), and camel ked (MK880189); RotTat 1.2 VSG gene of T. evansi in camel (MK867833) and camel ked (MK867832).

Data analysis

Data on sampled camels and hippoboscids were entered into Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, version 12.3.1. Georeferenced data of the sampling sites and administrative boundaries data from Kenya Open Data in shapefile data format, were loaded into the ArcMap component of ArcGIS 10.6 software. The component was then used to design and generate the map layout of the sampling sites.

Using the MAFFT plugin in Geneious Prime 2019.1.1 software version (created by Biomatters) ( Kearse et al., 2012), all study nucleotide sequences were edited and aligned with related sequences identified by querying in the GenBank nr database using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool ( www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

Results

Detections of pathogens

Out of 249 camel samples screened, 102 (40.96%) tested positive for trypanosomes by ITS1 PCR ( Table 2). All trypanosome positive samples were infected with T. vivax showing an expected band of 250 bp and confirmed by amplicon sequencing. Mixed infections with T. vivax (250-bp band) and T. evansi (480-bp band) were detected in three camels (1.2%).

Table 2. Summary of selected pathogens detected in camels and Hippobosca camelina.

| Pathogen | Prevalence in

camels ( n = 249) |

Prevalence in

H. camelina ( n = 117) |

|---|---|---|

| Trypanosoma vivax | 102 (41%) | 53 (45.3%) |

| Trypanosoma evansi | 3 (1.2%) | 3 (2.56%) |

| Trypanosoma melophagium | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.85%) |

| “ Candidatus Anaplasma camelii” | 171 (68.67%) | 19 (16.24%) |

Out of 117 H. camelina samples, 53 (45.30%) were infected with trypanosomes, all of which had T. vivax. Three flies (2.56%) had mixed infections with T. evansi and T. vivax. Additionally, one fly had double infection of T. vivax and Trypanosoma sp. amplicon of about 400 bp. The 400 bp Trypanosoma sp. was sequenced using the ITS1 marker and shared 98.14% identity with Trypanosoma melophagium (GenBank accession HQ664851) that was sequenced from Melophagus ovinus, sheep ked, in Croatia. Figure 3 shows pairwise alignment of T. melophagium sequence from this study and that from GenBank.

Figure 3. Pairwise alignment of ITS1 sequences of T. melophagium.

ITS1 sequence of T. melophagium in study sample H63 was aligned with highly identical sequence (HQ664851) from GenBank. At position 32, there is a nucleotide change from C in the sequence from GenBank to Y in the sequence from this study.

In total 98% of all monoconical trap catches were Stomoxys calcitrans, with the remaining 2% consisting of Tabanidae and H. camelina ( Table 3). None of the traps caught tsetse (0%) in all sampling locations.

Table 3. Biting flies were trapped using monoconical traps with cow urine and acetone as attractants.

Daily trap collections were pooled, fly species sorted, counted, and preserved in absolute ethanol for transportation to the Nairobi-based laboratories at icipe. Majority of the fly collections comprised of Stomoxys calcitrans. Tsetse flies (genus Glossina) were absent in all traps.

| Sampling site | Day | *Daily fly captures | Sex (M = male; F = female) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Kula pesa

01° 35’ 44.9” N, 037° 48’ 35.8” E |

Day 1 | 12 | 12 F – Stomoxys calcitrans |

| Day 2 | 8 | 5 F –

S. calcitrans;

1 M & 2 F – Hippobosca camelina |

|

| Day 3 | 4 | 3 F –

S. calcitrans;

1 F – H. camelina |

|

| Day 4 | 12 | 9 F & 1 M -

S. calcitrans;

1 F – Tabanus spp.; 1 M – H. camelina |

|

| Day 5 | 5 | 4 F –

S. calcitrans;

1 F – H. camelina |

|

| Day 6 | 11 | 1 M & 9 F –

S. calcitrans;

1 M – H. camelina |

|

| Day 7 | 8 | 6 M & 2 F – S. calcitrans | |

|

Soweto

01° 35’ 43.1” N, 037° 48’ 35.7” E |

Day 1 | 2 | 2 F – S. calcitrans |

| Day 2 | 9 | 2 M & 7 F – S. calcitrans | |

| Day 3 | 7 | 1 M & 6 F – S. calcitrans | |

| Day 4 | 7 | 2 M & 4 F –

S. calcitrans;

1 F – H. camelina |

|

| Day 5 | 2 | 2 F – S. calcitrans | |

| Day 6 | 9 | 9 F – S. calcitrans | |

| Day 7 | 0 | Biting flies count = 0

(Only house flies were trapped) |

|

|

Naigero

01° 35’ 49.7” N, 037° 49’ 58.1” E |

Day 1 | 33 | 8 M & 25 F – S. calcitrans |

| Day 2 | 14 | 2 M & 12 F – S. calcitrans |

*Daily fly captures: represent pools of three trap catches per site per day.

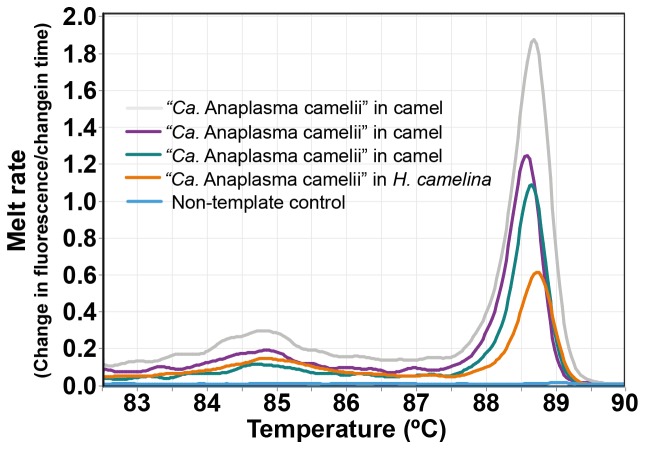

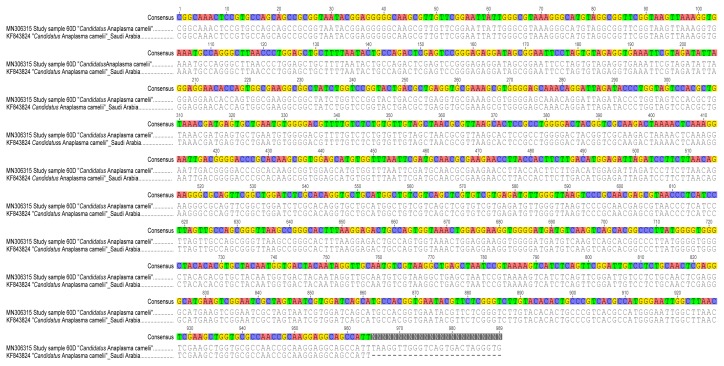

“Candidatus Anaplasma camelii” was detected in 68.67% ( n = 171/249) of dromedary camels and 16.24% ( n = 19/117) of H. camelina ( Figure 4). Though the 300-bp Anaplasma 16S rRNA sequences could not resolve the Anaplasma spp. to species level, analysis of the 1000-bp 16S rRNA nucleotide sequence showed 100% identity with “ Candidatus Anaplasma camelii” sequenced from camels in Saudi Arabia (GenBank accession numbers KF843824-KF843825) and Iran (GenBank accession KX765882) ( Figure 5). Piroplasms ( Theileria spp. and Babesia spp.), C. burnetii, Ehrlichia spp., Brucella spp., and camel pox were not detected either in camels or keds collected from them.

Figure 4. Melt curves of amplification of 16S rRNA of “ Candidatus Anaplasma camelii” in camels and camel keds.

Figure 5. Pairwise alignment of 16S rRNA sequences of “ Candidatus Anaplasma Camelii” amplified from camel blood sample 60D with GenBank-retrieved nucleotide sequence (KF843824) showed 100% identity.

N is ambiguous nucleotide.

Discussion

We report the occurrence of similar blood-borne pathogens in dromedary camels and in H. camelina flies collected from the same herds. The high infection rates of pathogens in camels ( T. vivax = 41%, T. evansi = 1.2%, and Anaplasma spp. = 68.67%) and flies ( T. vivax = 45.3%, T. evansi = 2.56%, and Anaplasma spp. = 16.24%) suggest the potential of these camel biting flies in disease transmission as well in diagnosis of haemopathogens found in camels. Thus, our findings show T. vivax as the most predominant species causing trypanosomiasis in camels sampled in September 2017 from Koya and its surroundings. Similarly, we recorded high fly infection rates of 45.3% caused by the same parasite, T. vivax. These high T. vivax infection rates could be attributed to mechanical transmission by several biting flies such as Tabanus spp. and Stomoxys species ( Baldacchino et al., 2013) that were collected in this study using monoconical traps ( Table 3). We hypothesize that camels are initially infected with trypanosomes when nomadic pastoralists occasionally move their livestock into distant neighbouring tsetse-infested regions in search of pasture and water, and thereafter maintenance of pathogen transmission among camels continues throughout the year via mechanical transmission in the process of bloodmeal acquisition by biting flies such as camel hippoboscids.

Tsetse flies were not caught despite repeated attempts to trap them in major sampling sites using monoconical traps with cow urine and acetone ( Table 3). This ASAL region in Marsabit south is generally arid, hot, and dry (low humidity) with poor vegetation cover that presumably renders it uninhabitable for tsetse flies. However, by using robust landscape and climatic data modeling, Marsabit has generally been predicted as a region with potential risk of tsetse infestation ( Moore & Messina, 2010).

Currently, little is known about the prevalence and transmission of vector-borne diseases of livestock in northern Kenya, mostly because these animals belong to the marginalized poor nomadic pastoralists whose economic welfare is neglected. Thus, information about T. vivax in Kenyan camels is scarce. However, T. vivax has been reported in camels in Sudan, Ethiopia, and Nigeria ( Fikru et al., 2015; Mbaya et al., 2006; Mossaad et al., 2017). The pathogenicity of T. vivax infection in camels is not well understood, but it is known to be pathogenic to cattle, sheep, equines, and goats ( Galiza et al., 2011). Our finding of a high trypanosome infection rate (40.96%) in camels, consisting predominantly of T. vivax, suggests that infected camels could act as parasite reservoirs for other susceptible and often co-herded livestock species in the region.

Trypanosoma evansi infection rates of 1.2% in camels reported in this study is much lower than earlier reports of up to 46% infections in other regions of Kenya ( Ngaira et al., 2004; Njiru et al., 2004). These regional variations in prevalence of T. evansi infection could result from seasonal disease outbreaks, variations in the micro-climatic conditions, disease stability in endemic zones, and the presence of competent insect-vectors, among other factors, including differences in the study designs and time lapse. Our study design has key limitations in comparative studies because sampling was not done during wet season, thus the relationship between seasonality versus prevalence of haemoparasites and vector density could not be established. Trypanosoma evansi is considered the most important protozoan pathogen of dromedary camels in Kenya ( Njiru et al., 2004) and has been reported to infect horses and donkeys in other parts of the world ( Desquesnes et al., 2013). Additionally, cases of atypical T. evansi infections have been reported in humans (reviewed in Truc et al., 2013) and was specifically attributed to frameshift mutations of apolipoprotein L-I in one of the patients ( Vanhollebeke et al., 2006), thus resulting into lack of immunity against African animal trypanosomes.

“ Candidatus Anaplasma camelii” infection, which we report here for the first time in Kenyan camels, was the most prevalent (68.67%) amongst all detected pathogens in this study. This emergent Anaplasma pathogen was recently detected in 35.85% of Moroccan dromedary camels ( Ait Lbacha et al., 2017). Anaplasma sp. isolated from Kenyan camels was 100% identical to the GenBank-retrieved “ Candidatus Anaplasma Camelii” 16S rRNA nucleotide sequences from Saudi Arabia and Iran dromedary camels, hence suggesting a common origin of this pathogen ( Figure 5). High prevalence of camel anaplasmosis could be attributed to ticks (the definitive vector of Anaplasma) that were present on 100% of camels, and in addition, biting flies such as Stomoxys calcitrans promote mechanical transmission ( Scoles et al., 2005). Although previous studies could not prove the ability of cattle keds ( Hippobosca rufipes) to transmit Anaplasma marginale ( Potgieter et al., 1981), it is possible that in the process of bloodmeal acquisition, camel keds, Hippobosca camelina, could mechanically transmit anaplasmosis via contaminated mouthparts (unpublished study; authors from the present study). The clinical role of “ Candidatus Anaplasma camelii” in camels is uncertain, but oedema has been observed in infected camels ( Ait Lbacha et al., 2017).

The high prevalence of “ Candidatus Anaplasma camelii” in healthy dromedary camels indicates the possible role of camels as reservoir hosts for maintaining its circulation. Further research is needed to determine the zoonotic potential of this tick-borne pathogen. This is important because cases of human infection with Anaplasma platys and Ehrlichia canis, that are closely related to the emergent “ Candidatus Anaplasma camelii” pathogen, have been reported ( Arraga-Alvarado et al., 2014; Doudier et al., 2010). This possibly zoonotic pathogen of camels ( Lbacha et al., 2017) should stimulate the need for increased surveillance by veterinary and public health partners to mitigate spread of infection to humans and other animals.

We detected T. vivax, T. evansi, T. melophagium, and Anaplasma species in Hippobosca camelina. Detection of identical haemopathogens in H. camelina flies as well as in camels from which they were collected suggests that this fly could play role in the transmission of infectious agents amongst its bloodmeal hosts. The ability of H. camelina as efficient flier facilitates fast movements on the host or between camel hosts, hence increasing its chances of acquiring infected bloodmeal that could transmitted to the next host following interrupted feeding. Various hippoboscid species have been implicated in transmission of pathogens ( Rahola et al., 2011). For instance, Hippobosca longipennis is thought to transmit the larva of filarial nematode Acanthocheilonema dracunculoides to hyenas and domestic dogs ( Nelson, 1963; Rani et al., 2011). Louse flies, Melophagus ovinus, play a role in the transmission of Bartonella spp. among ruminants ( Halos et al., 2004). Another louse fly known as Icosta americana is suspected to transmit West Nile virus in North America ( Farajollahi et al., 2005). Further studies are needed to determine the vectorial competence of H. camelina in the transmission of pathogens.

Potential role of H. camelina in xenodiagnosis

Our findings consistently show that the blood-borne pathogens detected in camels are also present in H. camelina collected from them (i.e. sampled camels). It is likely that when keds bite camel hosts to acquire bloodmeals, they also take up haemopathogens if the camel is infected.

H. camelina acquires bloodmeals from camels for nutrition and reproduction. Adult stage of keds are obligate blood-feeding ectoparasites of camels that hardly leave their host, unless disturbed and even then, they quickly find the next host. Keds have claspers for firm attachment to the skin hairs of the host during feeding or resting. These flies that prefer to always remain on the vertebrate host, preferentially attach to specific body parts, commonly on the underbelly ( Figure 2) of the camel, near or on the udder, or the perineal region where they are not easily disturbed during bloodmeal acquisition ( Higgins, 1985). These features of camel keds make them good candidates for xenosurveillance and they can be collected easily for molecular screening to detect pathogens acquired from naturally infected camels in the process of feeding. Screening of camel keds for indirect detection of pathogens present in camels, from which they were collected, will save on time and cost. Collection of keds off camels was much easier and required relatively less time than blood sampling. We employed six field assistants to restrain each camel for blood collection, veterinary personnel who collected blood samples, and additional three assistants to carry cool boxes and consumables, ensure accurate labeling of samples and storage, and recording of baseline data. On the other hand, only about four field assistants were needed to collect keds from camel herds, resulting in >50% reduction in labour costs and the required human resource. Fly collection also took shorter time as it was not necessary to restrain camels. Importantly, this xenosurveillance detection provides a less invasive approach than the currently available painful blood collection procedures that pose huge risk to the handlers as camels could occasionally cause severe and even fatal injuries through bites ( Abu-Zidan et al., 2012) or by kicking with their legs. In a similar indirect pathogen detection approach, previous reports showed the utility of mosquitoes in xenosurveillance of human pathogens ( Grubaugh et al., 2015).

Additionally, a novel Trypanosoma sp. closely related to Trypanosoma melophagium was detected in one camel ked, H. camelina (1/117) , but not in camels. This host-specific parasite of sheep, called T. melophagium, has never been reported to cause camel infections. Interestingly, T. melophagium is known to be solely transmitted by wingless sheep ked called Melophagus ovinus ( Gibson et al., 2010). We conducted a survey of sheep keds among small ruminants in our study area in northern Kenya and found that they are absent in the region (unpublished study; authors from the present study). Thus, molecular detection of T. melophagium in a single camel-specific ked that was collected from camel raises an interesting question about the origin of this parasite. H. camelina acquired contamination possibly from T. melophagium-infected vertebrate host through bloodmeal. Further studies are needed to determine the vectorial competence of H. camelina in transmission of T. melophagium.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest the potential role of H. camelina in xenodiagnosis for detection of haemopathogens in camels, thus bypassing the need to obtain blood samples via jugular venipuncture for pathogen detection. Further studies to profile additional blood-borne pathogens including viral diseases occurring both in camels and H. camelina that fed on them, will be crucial for supporting usage of hippoboscids in xenomonitoring of camel diseases.

Data availability

Underlying data

16S r RNA of Anaplasma sp. in camel, Accession number MN306316: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MN306316

16S r RNA of Anaplasma sp. in camel ked, Accession number MN306317: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MN306317

16S rRNA of Candidatus Anaplasma camelii, Accession number MN306315: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MN306315

T. vivax ITS1 in camel, Accession number MK880188: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MK880188

T. vivax ITS1 in camel ked, Accession number MK880189: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MK880189

RotTat 1.2 VSG gene of T. evansi in camel, Accession number MK867833: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MK867833

RotTat 1.2 VSG gene of T. evansi camel ked, Accession number MK867832: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MK867832

Figshare: Detection of Anaplasma and Trypanosomes in camels and camel keds, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10050587 ( Kidambasi et al., 2019).

This project contains the following underlying data:

-

-

Raw HRM Rotor-Gene Q data files of Anaplasma spp. amplification in camels and camel keds. HRM data files can be accessed using Rotor-gene Q software.

-

-

Gel visualization images of resolved PCR amplicons for detection of African trypanosomes in camels and camel keds.

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero "No rights reserved" data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all camel farmers from Laisamis who consented to sampling of their camels and for actively participating in community engagement sessions. We thank the following community field assistants for restraining camels during sample collection; Galtumo Lordagos, Ogoga Kaldale, Lmachungwan Galgitele, Ltulusuan Letoiye, Moika Naparakwo, Fereiti Bargul, and Ali Baltor. John Ng’iela of icipe’s Animal Health Theme provided invaluable support during field studies. Winny Cherono ( icipe) generated map of Kenya showing sampling sites.

Funding Statement

This work was supported through the DELTAS Africa Initiative grant # DEL-15-011 to THRiVE-2. The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)’s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust grant # 107742/Z/15/Z and the UK government. This research study received supplementary funding from the International Foundation for Science (IFS), Stockholm, Sweden, through an IFS grant # B/5925-1 to JLB; and from Cambridge-Africa Alborada Fund 2017/18 and The Global Challenges Research Fund - Pump-Priming Fund (GCRF grant #G100049/17588) awarded to MC and JLB. Additional support was obtained from icipe institutional funding from the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and the Kenyan Government. MC is a Wellcome Trust Investigator.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 2; peer review: 2 approved]

References

- Abu-Zidan FM, Eid HO, Hefny AF, et al. : Camel bite injuries in United Arab Emirates: a 6 year prospective study. Injury. 2012;43(9):1617–1620. 10.1016/j.injury.2011.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ait Lbacha H, Zouagui Z, Alali S, et al. : “ Candidatus anaplasma camelii” in one-humped camels ( Camelus dromedarius) in Morocco: a novel and emerging anaplasma species? Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:1. 10.1186/s40249-016-0216-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arraga-Alvarado CM, Qurollo BA, Parra OC, et al. : Case report: Molecular evidence of Anaplasma platys infection in two women from Venezuela. A J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91(6):1161–1165. 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balamurugan V, Bhanuprakash V, Hosamani M, et al. : A polymerase chain reaction strategy for the diagnosis of camelpox. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2009;21(2):231–237. 10.1177/104063870902100209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldacchino F, Muenworn V, Desquesnes M, et al. : Transmission of pathogens by Stomoxys flies (Diptera, Muscidae): a review. Parasite. 2013;20:26, 13. 10.1051/parasite/2013026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos AD, Mohammed OB, Bennett NC, et al. : Molecular detection of novel Anaplasmataceae closely related to Anaplasma platys and Ehrlichia canis in the dromedary camel ( Camelus dromedarius). Vet Microbiol. 2015;179(3–4):310–4. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengis RG, Kock RA, Fischer J: Infectious animal diseases: the wildlife/livestock interface. Rev Sci Tech. 2002;21(1):53–65. 10.20506/rst.21.1.1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desquesnes M, Dargantes A, Lai DH, et al. : Trypanosoma evansi and surra: a review and perspectives on transmission, epidemiology and control, impact, and zoonotic aspects. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:321237. 10.1155/2013/321237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doosti A, Arshi A, Sadeghi M: Investigation of Coxiella burnetii in Iranian camels. Comp Clin Path. 2014;23(1):43–46. 10.1007/s00580-012-1567-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doudier B, Olano J, Parola P, et al. : Factors contributing to emergence of Ehrlichia and Anaplasma spp. as human pathogens. Vet Parasitol. 2010;167(2–4):149–154. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT: Food and Agriculture Organization statistical database.2015. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Farajollahi A, Crans WJ, Nickerson D, et al. : Detection of West Nile virus RNA from the louse fly Icosta americana (Diptera: Hippoboscidae). J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2005;21(4):474–476. 10.2987/8756-971X(2006)21[474:DOWNVR]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faye B: The Camel Today: Assets and Potentials. Anthropozoologica. 2014;49(2):167–176. 10.5252/az2014n2a01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fikru R, Andualem Y, Getachew T, et al. : Trypanosome infection in dromedary camels in Eastern Ethiopia: Prevalence, relative performance of diagnostic tools and host related risk factors. Vet Parasitol. 2015;211(3–4):175–181. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiza GJ, Garcia HA, Assis AC, et al. : High mortality and lesions of the central nervous system in trypanosomosis by Trypanosoma vivax in Brazilian hair sheep. Vet Parasitol. 2011;182(2–4):359–363. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges K, Loria GR, Riili S, et al. : Detection of haemoparasites in cattle by reverse line blot hybridisation with a note on the distribution of ticks in Sicily. Vet Parasitol. 2001;99(4):273–286. 10.1016/s0304-4017(01)00488-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson W, Pilkington JG, Pemberton JM: Trypanosoma melophagium from the sheep ked Melophagus ovinus on the island of St Kilda. Parasitology. 2010;137(12):1799–804. 10.1017/S0031182010000752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubaugh ND, Sharma S, Krajacich BJ, et al. : Xenosurveillance: a novel mosquito-based approach for examining the human-pathogen landscape. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(3):e0003628. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halos L, Jamal T, Maillard R, et al. : Role of Hippoboscidae flies as potential vectors of Bartonella spp. infecting wild and domestic ruminants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(10):6302–6305. 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6302-6305.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins AJ: Common ectoparasites of the camel and their control. Br Vet J. 1985;141(2):197–216. 10.1016/0007-1935(85)90153-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassa T, Eguale T, Chak H: Prevalence of camel trypanosomosis and its vectors in Fentale district, South East Shoa Zone, Ethiopia. Veterinarski Arhiv. 2011;81(5):611–621. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Kazoora HB, Majalija S, Kiwanuka N, et al. : Prevalence of Mycobacterium bovis skin positivity and associated risk factors in cattle from western Uganda. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2014;46(8):1383–1390. 10.1007/s11250-014-0650-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, et al. : Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–1649. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidambasi K, Masiga DK, Villinger J, et al. : Detection of Anaplasma and Trypanosomes in camels and camel keds. figshare.Dataset.2019. 10.6084/m9.figshare.10050587.v1 [DOI]

- KNBS, Kenya National Bureau of Statistics: Kenya 2009 population and housing census. Vol II: Population and household distribution by socio-economic characteristics. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Government of Kenya.2010. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- KNBS, Kenya National Bureau of Statistics: County Government of Marsabit County Integrated Development Plan, 2013-2017. 2013;16–18. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Lamuka PO, Njeruh FM, Gitao GC, et al. : Camel health management and pastoralists’ knowledge and information on zoonoses and food safety risks in Isiolo County, Kenya. Pastoralism. 2017;7(1):20 10.1186/s13570-017-0095-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mbaya AW, Ibrahim UI, Apagu ST: Trypanosomosis of The Dromedary Camel ( Camelus dromedarius) and its Vectors in The Tsetse-free Arid Zone of North Eastern Nigeria. Niger Vet J. 2006;31(3):195–200. 10.4314/nvj.v31i3.68975 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mochabo KO, Kitala PM, Gathura PB, et al. : Community perceptions of important camel diseases in Lapur Division of Turkana District, Kenya. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2005;37(3):187–204. 10.1023/b:trop.0000049301.15826.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore N, Messina J: A landscape and climate data logistic model of tsetse distribution in Kenya. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11809. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossaad E, Salim B, Suganuma K, et al. : Trypanosoma vivax is the second leading cause of camel trypanosomosis in Sudan after Trypanosoma evansi. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10(1):176. 10.1186/s13071-017-2117-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwamuye MM, Kariuki E, Omondi D, et al. : Novel Rickettsia and emergent tick-borne pathogens: A molecular survey of ticks and tick-borne pathogens in Shimba Hills National Reserve, Kenya. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2017;8(2):208–218. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson GS: Dipetalonema dracunculoides (Cobbold 1870), from the dog in Kenya: with a note on its development in the louse-fly, Hippobosca longipennis. J Helmint. 1963;37(3):235–240. 10.1017/S0022149X00003825 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ngaira JM, Njagi EN, Ngeranwa JJ, et al. : PCR amplification of RoTat 1.2 VSG gene in Trypanosoma evansi isolates in Kenya. Vet Parasitol. 2004;120(1–2):23–33. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njiru ZK, Constantine CC, Ndung'u JM, et al. : Detection of Trypanosoma evansi in camels using PCR and CATT/T. evansi tests in Kenya. Vet Parasitol. 2004;124(3–4):187–199. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njiru ZK, Constantine CC, Guya S, et al. : The use of ITS1 rDNA PCR in detecting pathogenic African trypanosomes. Parasitol Res. 2005;95(3):186–192. 10.1007/s00436-004-1267-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oryan A, Valinezhad A, Bahrami S: Prevalence and pathology of camel filariasis in Iran. Parasitol Res. 2008;103(5):1125–1131. 10.1007/s00436-008-1104-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parola P, Roux V, Camicas JL, et al. : Detection of ehrlichiae in African ticks by polymerase chain reaction. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94(6):707–708. 10.1016/S0035-9203(00)90243-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen FT, Meier R, Kutty SN, et al. : The phylogeny and evolution of host choice in the Hippoboscoidea (Diptera) as reconstructed using four molecular markers. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2007;45(1):111–122. 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potgieter FT, Sutherland B, Biggs HC: Attempts to transmit Anaplasma marginale with Hippobosca rufipes and Stomoxys calcitrans. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1981;48(2):119–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probert WS, Schrader KN, Khuong NY, et al. : Real-time multiplex PCR assay for detection of Brucella spp., B. abortus, and B. melitensis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(3):1290–1293. 10.1128/jcm.42.3.1290-1293.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahola N, Goodman SM, Robert V: The Hippoboscidae (Insecta: Diptera) from Madagascar, with new records from the "Parc National de Midongy Befotaka". Parasite. 2011;18(2):127–40. 10.1051/parasite/2011182127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani PA, Coleman GT, Irwin PJ, et al. : Hippobosca longipennis--a potential intermediate host of a species of Acanthocheilonema in dogs in northern India. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:143. 10.1186/1756-3305-4-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reysenbach AL, Giver LJ, Wickham GS, et al. : Differential amplification of rRNA genes by polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58(10):3417–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoles GA, Broce AB, Lysyk TJ, et al. : Relative efficiency of biological transmission of Anaplasma marginale (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) by Dermacentor andersoni (Acari: Ixodidae) compared with mechanical transmission by Stomoxys calcitrans (Diptera: Muscidae). J Med Entomol. 2005;42:668–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šimenc J, Potočnik U: Rapid differentiation of bacterial species by high resolution melting curve analysis. Appl Biochem Micro+. 2011;47(3):256–263. 10.1134/S0003683811030136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SSFR, Smart Survey Final Report: Laisamis and North Horr Survey Zones, Marsabit County 18 th– 29 thJanuary 2017. 2017. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Tokarz R, Kapoor V, Samuel JE, et al. : Detection of tick-borne pathogens by MassTag polymerase chain reaction. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;9(2):147–52. 10.1089/vbz.2008.0088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truc P, Büscher P, Cuny G, et al. : Atypical human infections by animal trypanosomes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(9):e2256. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urakawa T, Verloo D, Moens L, et al. : Trypanosoma evansi: cloning and expression in Spodoptera frugiperda [correction of fugiperda] insect cells of the diagnostic antigen RoTat1.2. Exp Parasitol. 2001;99(4):181–9. 10.1006/expr.2001.4670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhollebeke B, Truc P, Poelvoorde P, et al. : Human Trypanosoma evansi infection linked to a lack of apolipoprotein L-I. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(26):2752–2756. 10.1056/NEJMoa063265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younan M, Abdurahman O: Milk and Meat from the Camel: Handbook on Products and Processing.Z. Farah A. Fischer (Editors), vdf Hochschulverlag AG, ETH Zuerich, Zuerich/Singen, Switzerland.2014;67–76. ISBN 372812527X. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Young KE, Franklin AB, Ward JP: Infestation of northern spotted owls by hippoboscid (Diptera) flies in northwestern California. J Wildl Dis. 1993;29(2):278–83. 10.7589/0090-3558-29.2.278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]