Abstract

Conceivably, upregulation of myo-inositol oxygenase (MIOX) is associated with altered cellular redox. Its promoter includes oxidant-response elements, and we also discovered binding sites for XBP1, a transcription factor of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response. Previous studies indicate that MIOX’s upregulation in acute tubular injury is mediated by oxidant and ER stress. Here, we investigated whether hyperglycemia leads to accentuation of oxidant and ER stress while these boost each other’s activities, thereby augmenting tubulointerstitial injury/fibrosis. We generated MIOX-overexpressing transgenic (MIOX-TG) and MIOX knockout (MIOX-KO) mice. A diabetic state was induced by streptozotocin administration. Also, MIOX-KO were crossbred with Ins2Akita to generate Ins2Akita/KO mice. MIOX-TG mice had worsening renal functions with kidneys having increased oxidant/ER stress, as reflected by DCF/dihydroethidium staining, perturbed NAD-to-NADH and glutathione-to-glutathione disulfide ratios, increased NOX4 expression, apoptosis and its executionary molecules, accentuation of TGF-β signaling, Smads and XBP1 nuclear translocation, expression of GRP78 and XBP1 (ER stress markers), and accelerated tubulointerstitial fibrosis. These changes were not seen in MIOX-KO mice. Interestingly, such changes were remarkably reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice and, likewise, in vitro experiments with XBP1 siRNA. These findings suggest that MIOX expression accentuates, while its deficiency shields kidneys from, tubulointerstitial injury by dampening oxidant and ER stress, which mutually enhance each other’s activity.

Introduction

Diabetes is a well-described metabolic disorder in which hyperglycemia adversely affects the homeostasis of multiple organs in humans, and the commonly encountered lesions include microangiopathy, neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy (1–4). The latter, i.e., diabetic nephropathy (DN), has been exhaustively investigated, in terms of its pathogenetic mechanisms, in various animal model and cell culture systems (5–10). In this regard, the studies carried out over the last few decades suggest that all cells of the kidney, namely, glomerular podocytes, endothelial and mesangial cells, tubular epithelia, interstitial fibroblasts, and vascular endothelia, are known to be variably affected by hyperglycemia (8,11–16). The major focus in these studies had been to explore the pathogenetic mechanisms pertaining to the “glomerular” compartment, while the “tubulointerstitium” received much less attention (14,17–20).

Among the various pathogenetic mechanisms, reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been regarded as common denominators in the signaling cascade relevant to the pathogenesis of DN, and a majority of the publications refer to ROS in the context of glomerular pathology and a few also address the subject matter of “diabetic tubulopathy” (1,14,15,17–22). ROS can be generated as a result of perturbations either in the mitochondrial homeostasis or NADPH oxidase system (1,21–23). In this regard, it should be noted that increased activity of the polyol pathway leads to an altered redox state of pyridine nucleotides (NADPH-to-NADP+ and NAD+-to-NADH ratios). The key enzymes that are operative in the polyol pathway include aldose reductase and sorbitol dehydrogenase that are expressed in the “tubules” and modulate renal osmoregulation (24) (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Akin to the polyol pathway seems to be another pathway, i.e., the glucuronate-xylulose (G-X) pathway, in which perturbations in the NADPH-to-NADP+ and NAD+-to-NADH ratios are anticipated with consequential redox imbalance and oxidant stress in the “tubular” compartment (25) (Supplementary Fig. 1B). In this G-X pathway, exogenous or endogenous myo-inositol (MI) is catabolized by MI oxygenase (MIOX) to glucuronic acid, which is channeled subsequently into d-xylulose-5-phosphate (Supplementary Fig. 1B).

MIOX is a 32 kDa cytosolic enzyme expressed in the renal proximal tubules, and it is upregulated in states of hyperglycemia (26–28). Previous studies suggest that phosphorylation of MIOX’s serine/threonine residues enhances its enzymatic activity (27). Interestingly, MIOX promoter includes osmotic-, carbohydrate-, sterol-, oxidant-and antioxidant-response elements, and thus its transcription is modulated by organic osmolytes, high glucose, fatty acids, and oxidant stress (25–29). Since oxidant stress or ROS are regarded as central to the pathogenesis of DN, it is imperative to assess the lineal contribution of MIOX toward ROS-mediated injury in the renal tubulointerstitial compartment. The impetus to evaluate MIOX’s status in tubulointerstitial injury comes from the observations made in animal models of obesity and acute kidney injury (AKI) where MIOX upregulation was noted to be associated with increased cellular oxidant stress, especially confined to the tubular compartment (29,30). Moreover, a clinical study on patients with renovascular complications reported an association of type 1 diabetes with polymorphism of MIOX gene, which underscores its clinical significance in the pathobiology of DN (31), although a comprehensive analysis of the events responsible for the MIOX-ROS–mediated tubulointerstitial injury in DN needs to be included in experimental animal models. Besides ROS, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetes, obesity, AKI, and chronic kidney disease (7,9,32–35). Whether MIOX worsens ER stress in DN remains to be explored. Of note, our laboratory has reported that MIOX upregulation accelerates the ER stress in a tunicamycin mice model of chemical-induced acute tubular injury (36).

In view of the above observations, it is conceivable that cellular burden of both the oxidant and ER stress together accelerates the progression of DN in states of high-glucose ambience associated with MIOX upregulation. This contention is the subject matter of this seminal investigation with emphasis on the delineation of mechanisms relevant to the progression of tubulointerstitial injury, i.e., diabetic tubulopathy, using comprehensive in vitro and in vivo model systems; the latter includes MIOX mutant mice.

Research Design and Methods

Generation of MIOX Transgenic, Knockout, and Double Mutant Mice

Generation of mice with overexpression of MIOX (MIOX-transgenic [MIOX-TG]) and MIOX knockout (MIOX-KO) has previously been described (30). Also, heterozygous Ins2Akita mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were mated with MIOX-KO to generate double mutant mice, MIOX-KO/Ins2Akita. The reagents were purchased from the vendors listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Animal Experimental Models and Renal Functional Studies

Eight-week-old male mice of various strains, i.e., wild type (WT) C57BL/6J, MIOX-TG, and MIOX-KO mice, were batched into control and streptozotocin (STZ) groups (n = 6). The latter received an intraperitoneal injection of STZ (150 mg/kg). After 1 week, mice with blood glucose levels >250 mg/dL were considered diabetic, and they were sacrificed after 4 months. Similarly, 8-week-old Ins2Akita and Ins2Akita/KO mice were sacrificed after 4 months. At the time of sacrifice, blood and urine samples and kidneys were collected. Serum creatinine and urea levels were estimated using QuantiChrom Creatinine Assay Kit and QuantiChrom Urea Assay Kit. Urinary albumin and creatinine concentrations were measured using Exocell kits to calculate albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). Serum cystatin C and urinary KIM-1 levels were measured using ELISA assay kits. For albuminuria, SDS-PAGE analyses were also performed. The kidney cortices were processed for various other studies. All procedures used in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Northwestern University.

Cell Culture Experiments and Generation of Stable Transfectants

A full-length MIOX cDNA was generated by RT-PCR using sense (5′-TCGTGATAAGCTTATGAAGGTC GATGTGG-3′) and antisense (5′-ATCACACGGGATCCTCACCAGCTCAGGGT-3′) primers. HindIII and BamH1 sites (underlined) were introduced. Amplified PCR product was digested with respective restriction enzymes and cloned into pcDNA3.1. Transfection of pcDNA into human kidney (HK)-2 cells and generation of stable transfectants were performed as previously described (14). MIOX-overexpressing cells were used for various experiments as follows: ∼2 × 105 cells were seeded onto 55 cm2 culture dishes and maintained to achieve ∼80% confluency. Following trypsinization, ∼1 × 105 cells were plated on the 2.2 cm2 coverslips for morphological studies. Additional experiments included treatment of cells with high d-glucose (HG) (30 mmol/L) for 24 h or N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) (1 mmol/L) for 6 h. l-glucose was used as an osmotic control. For gene disruption studies, cells were grown in the presence of 50 μmol/L XBP1 siRNA.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

For localization of the expression of proteins, immunofluorescence (IMF) studies were carried out on cells and kidney tissues (14,20,29,30). Briefly, HK-2 cells were seeded (1 × 105) on the 2.2 cm2 coverslips. They were subjected to various treatments and subsequently processed for IMF using primary and secondary antibodies and TO-PRO-3 iodide (TOPO) red dye as a nuclear marker. For renal expression studies, 4-μm-thick cryostat sections were prepared. They were air dried, washed with PBS, and incubated with primary and secondary antibodies. The cells or tissues were examined using an ultraviolet microscope. The experiments were performed in quadriplicates on kidney tissues harvested from four individual mice/cell culture experiments of each group.

Immunohistochemical Studies

Kidney slices (4–5 mm thick) were prepared. After dehydration, the slices were embedded in paraffin. Sections were prepared (4 μmol/L thick) and mounted on glass slides. Sections were air-dried, deparaffinized, hydrated, subjected to antigen retrieval, and used for detection of XBP1 (14,30). The experiments were performed in quadriplicates on kidney tissues harvested from four individual mice of each group.

Immunoblot Analysis of Relevant Proteins

The details of immunoblotting procedures are given in previous publications (14,29). Briefly, kidney cortices were diced into 1 mm3 fragments and homogenized in a radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. After centrifugation, the supernatants with equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. They were incubated with primary and secondary antibodies, and the autoradiograms were prepared using ECL Western Blotting Detection Kit (Amersham). The immunoblots were performed on the lysates isolated from four different animals individually, and the lysates were not pooled. The blots depicted in various figures are representative of the data of four individual mouse kidneys from each group.

MIOX Enzymatic Activity Assay and MI Concentration

MIOX activity was carried out as described previously (20,26,29). The MI concentration in kidney cortices was measured using a Megazyme assay kit as per manufacturer instructions. Approximately 20 mg kidney tissue was homogenized in 400 μL PBS followed by centrifugation at 10,000g for 5 min at room temperature. Supernatant was collected, and 100 μL sample was incubated in a reaction mixture containing 100 μL ATP, 400 μL H2O, 100 μL solution 1 (provided in the kit, pH 7.5) and 20 μL hexokinase at 22°C for 15 min. To this supernatant-reaction mixture, 1 mL solution 4 (pH 9.5), 500 μL NAD/ iodonitrotetrazolium chloride, and 20 μL diaphorase were added. After 3 min, first absorbance (A1) was measured at optical density 492 nm (OD492 nm). Ten minutes later, 20 μL MI dehydrogenase was added, and second absorbance (A2) was measured at OD492 nm. The concentration of MI in the sample was calculated as follows: C = (2.26 × 180.16/19900 × 1 × 0.1) × A2 −A1, where C is concentration. Finally, the concentration in the kidney sample was calculated as follows: Cinositol/weightsample × 100 and expressed as mg/100 g. Likewise, the MI concentration in 100 μL serum was calculated and expressed as milligrams per deciliter.

Assessment of Oxidant Stress and Determination of GSH-to-GSSG and NAD+-to-NADH Ratios

For oxidant stress, kidney tissues and HK-2 cells that had undergone various treatments were stained with 10 μmol/L of either 2′-7′-dichlorofluroescein diacetate (DCF-DA) or dihydroethidium (DHE) dye and then photographed and evaluated as previously described (29,30). Glutathione (GSH)-to-glutathione disulfide (GSSG) ratio was measured using GSH assay kit (Cayman Chemical) (30). NAD+-to-NADH ratio was determined by using a colorimetric assay kit (Abcam). Twenty milligrams of kidney cortex were homogenized in 400 μL extraction buffer supplied in the kit and then centrifuged at 10,000g for 5 min at 4°C. Supernatant was collected, and it was passed through a 10 kDa spin column (ab93349; Abcam). For total NAD estimation, samples were left at 4°C. For NADH estimation, NAD+ was decomposed by incubating 200 μL sample at 60°C for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by placing the samples on ice. Samples were briefly spun to remove precipitates. The reaction was set up by using 50 μL standard or sample, 100 μL NAD cycling mix (98 μL NAD cycling buffer and cycling enzyme) (37). Samples were incubated at 22°C for 5 min for the conversion of NAD to NADH. Ten microliters of developer was added to the samples, and they were left at 22°C. Readings (OD450 nm) were recorded for 1–4 h. Concentration was measured using a standard curve.

TUNEL Assay

HG-induced DNA damage was assessed by TUNEL procedure (14,29). In brief, tissue sections were deparaffinized, hydrated with decreasing concentrations of ethanol, and then digested with proteinase K (240 units/mL; Promega, Madison, WI) for 15 min at 37°C. After washing the sections with PBS twice, nicked DNA was enzymatically labeled with a fluorescent nucleotide probe (Roche). Slides were coverslip mounted with a drop of mounting media and photographed using an ultraviolet microscope.

Nuclear Protein Isolation for In Vitro Gel Shift Assay

HK-2 cells transfected with empty vector or MIOX pcDNA were subjected to HG (30 mmol/L) ambience, and in a separate experiment they were concomitantly treated with XBP siRNA. Cells were washed with cold PBS, scraped from the culture dishes, and pelleted by centrifugation at 4°C. They were used for nuclear protein isolation (27,29). Isolated nuclear extracts were used for gel shift assay to determine the binding of XBP1 transcription factor to MIOX promoter. Detailed in silico analysis (TRANSFAC, version 8.3) of MIOX promoter revealed a putative binding site for XBP1. In view of this, a complementary double-stranded oligo having the putative binding site for XBP1 in the MIOX promoter was custom synthesized. The sequence for XBP1 oligo was as follows: 5′-CCTGGCCACGCTCCAAGACG-3′ (−992 to −988). The underlined sequence is the predicted binding site for XBP1. The oligo was labeled with ATP [γ-32]. Binding reaction was performed in a volume of 20 μL containing 1× binding buffer for 15 min at 37°C. The reaction mixture was subjected to nondenaturing 7.5% PAGE to assess DNA-protein interactions. The gels were air-dried and autoradiograms developed.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Details of chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay have previously been described (27,29). Briefly, ∼30 mg renal cortical tissue was pulverized in the presence of liquid nitrogen. After cross-linking of DNA and proteins with formaldehyde, the DNA was sonicated to generate 200–1,000 base pair fragments. The sample was centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000g at 4°C, and the supernatant was used for immunoprecipitation with XBP1 antibody. DNA-protein-antibody complex was digested with proteinase K, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation to isolate the pure DNA. The DNA was subjected to quantitative PCR analyses. Primers used for ChIP PCR encompassed the XBP1-binding region of MIOX promoter (−152 to −1). Their sequences were as follows: 5′-AGGAAGGAGCATGGTCACTT (sense) and 5′-CCTGAGGGAGCAGT CACCCG-3′ (antisense). Amplification of target amplicon was reflected as a single primary peak in the melt curve, and secondary peaks of nonspecific PCR products were not discernible. Results of quantitative PCR were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCp method, and crossing point (Cp) values were normalized with input samples. The extent of binding of XBP1 with MIOX promoter was expressed as x-fold enrichment compared with the control sample. Mouse IgG served as a negative control.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism (version 7.01). The significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Dunn multiple comparisons. Results were expressed as mean ± SD of six samples in each variable.

Data and Resource Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

MIOX has been reported to be upregulated in diabetic states, and conceivably its overexpression leads to perturbations in the kidney homeostasis and thereby renal injury (14,27,29). Here, we describe key events and conceivable mechanisms that lead to various renal pathophysiologic disturbances in different strains of mice with variable expression of MIOX, i.e., C57BL/6J (WT), MIOX-TG, and MIOX-KO, and in mice involved in rescuing of renal injury, i.e., Ins2Akita versus Ins2Akita/KO. The rationale for using an additional well-established genetic mouse model of type 1 diabetes, i.e., Ins2Akita, was to assess whether or not tubulointerstitial injury can be rescued in these mice when they are crossbred with MIOX-KO mice.

Alleviation of Renal Dysfunctions Following MIOX Gene Disruption

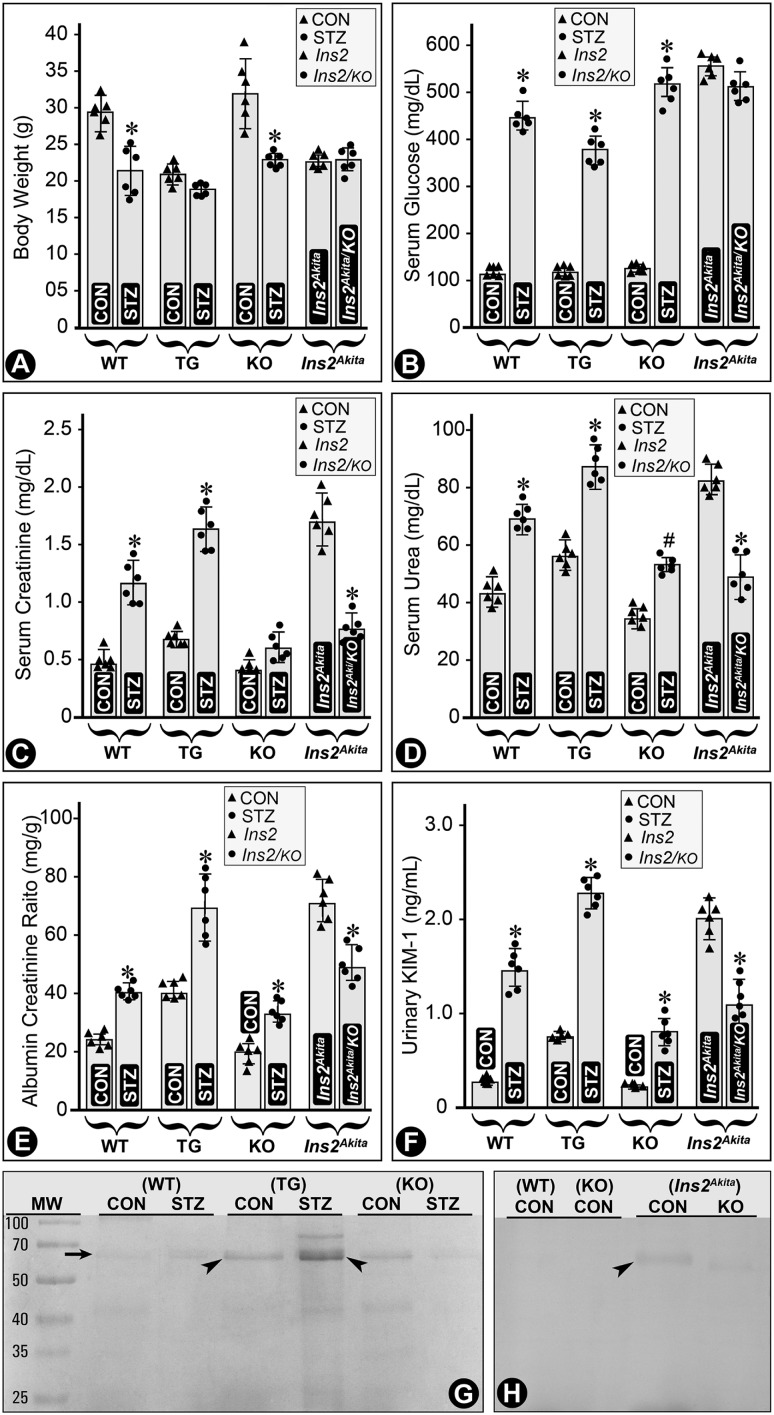

MIOX-TG and Ins2Akita mice had relatively low body weights, and they were further decreased in mice in a STZ-induced diabetic state (Fig. 1A). The blood glucose levels were high in all strains of mice following induction of diabetes and in Akita mice, and they did not change appreciably in the double mutant (Ins2Akita/KO) mice (Fig. 1B). Serum creatinine and urea levels remained low with a slight increase in diabetic MIOX-KO mice (Fig. 1C and D). Ins2Akita/KO mice had overtly decreased levels of creatinine and urea as compared with Ins2Akita mice (Fig. 1C and D). Parallel changes were observed for the ACR and cystatin C levels in various strains of mice (Fig. 1E and Supplementary Fig. 2). Urinary KIM-1 levels increased in diabetic WT, MIOX-TG, and MIOX-KO mice, with the highest being in the MIOX-TG mice (Fig. 1F). The Ins2Akita mice also had high levels of KIM-1, and they decreased significantly in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 1F). SDS-PAGE analyses of urine samples showed notable excretion of albumin in control MIOX-TG mice, which significantly increased in diabetic MIOX-TG mice (Fig. 1G, arrow and arrowheads). The Ins2Akita mice had mild excretion of albumin, but it was significantly reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 1H, arrowhead). Here, it is worth mentioning that under basal conditions (nondiabetic) no discernible differences in renal morphological features were observed among various strains of mice, i.e., WT, MIOX-TG, and MIOX-KO (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Status of body weight and renal functional parameters in mice with variable expression of MIOX in diabetic state. The MIOX-TG mice had lower body weight compared with WT and KO mice, and it was further decreased in diabetic state induced by STZ administration (A). The blood glucose levels were high in all the strains of mice following STZ induction of diabetes and in Ins2Akita mice (B). The serum creatinine and urea levels remained low, and they increased slightly in diabetic MIOX-KO mice (C and D). The serum creatinine and urea levels in Ins2Akita/KO mice decreased considerably compared with Ins2Akita mice. Similar changes were observed in urine ACR (E). Urinary KIM-1 levels were high in diabetic WT, MIOX-TG, MIOX-KO, and Ins2Akita mice, and they decreased significantly in Ins2Akita/KO mice (F). SDS-PAGE analyses of urine samples revealed a moderate excretion of albumin in the control MIOX-TG mice, and it increased considerably in diabetic state (G, arrow and arrowheads). The Ins2Akita mice had mild but notable excretion of albumin, and it was considerably reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (H, arrowhead). The SDS-PAGE analyses are representative of urine samples collected from four individual mice of each group. *P < 0.01; #P < 0.05. (n = 6 for bar graph data.) CON, control.

Hyperglycemia Accentuates MIOX Expression and Activity With Decreased Serum Levels of MI

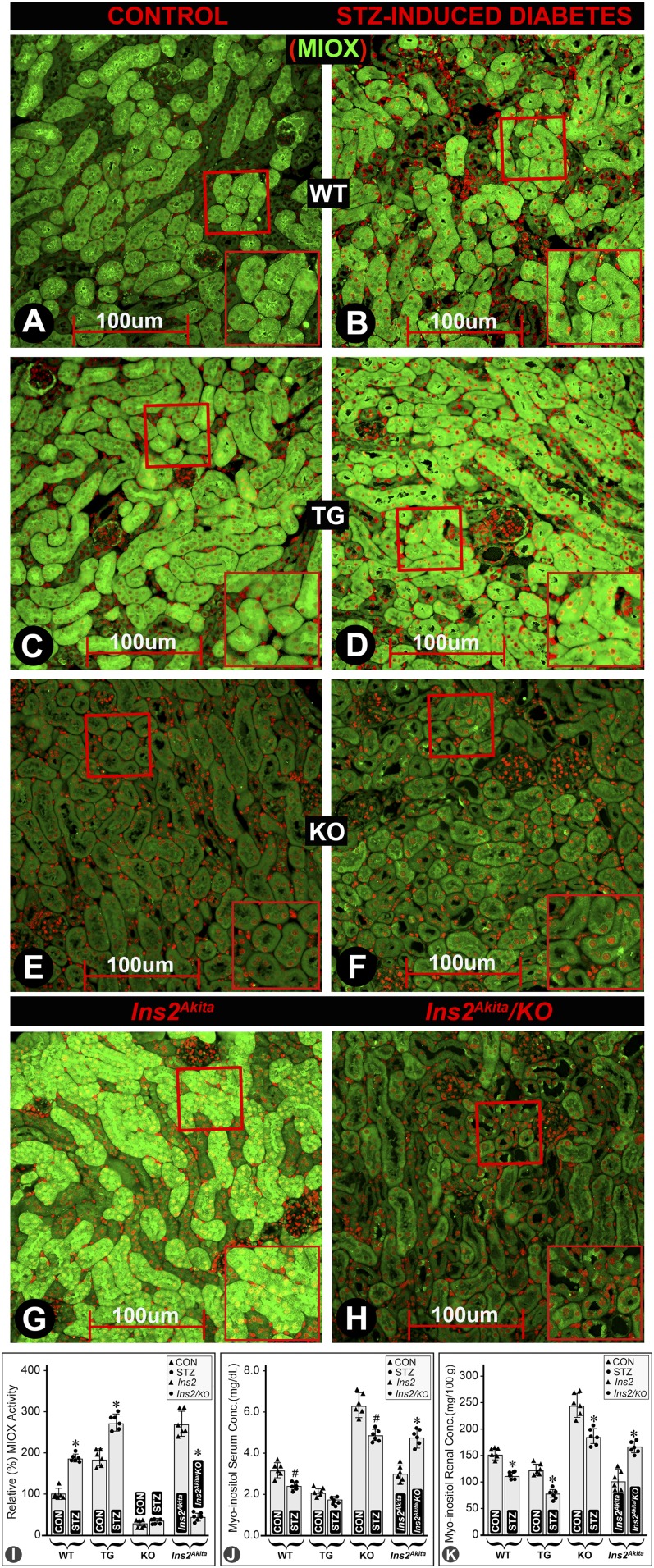

Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed an increased expression of MIOX in diabetic WT mice (Fig. 2B vs. Fig. 2A). Renal cortical tubules had a basal expression of MIOX, which increased in diabetic MIOX-TG mice (Fig. 2D vs. Fig. 2C). Minimal expression of MIOX was observed in MIOX-KO mice (Fig. 2E and F). A marked expression of MIOX was seen in Ins2Akita mice, which was notably reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 2H vs. Fig. 2G). Likewise, immunoblotting experiments revealed similar changes in MIOX expression pattern among different strains of mice (Supplementary Fig. 4). Basal enzymatic activity of MIOX was discernible in WT, MIOX-TG, and Ins2Akita mice (Fig. 2I). MIOX activity was high in MIOX-TG mice, and it notably increased in a diabetic state. MIOX activity was relatively high in Ins2Akita mice, and it was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 2I). The MI concentration was very high both in serum and kidney cortices of MIOX-KO mice, and it was reduced to varying degrees in diabetic WT, MIOX-TG, and MIOX-KO mice (Fig. 2J and K). MI concentration was low both in serum and kidney cortices of Ins2Akita mice, and it notably increased in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 2J and K).

Figure 2.

Expression of MIOX, its enzyme activity, and MI levels in diabetic state in various strains of mice. An increased expression of MIOX was observed in renal cortical tubules of diabetic WT mice (B vs. A). A notable basal expression of MIOX was seen in MIOX-TG mice, which was increased further in diabetic state (D vs. C). An insignificant background expression of MIOX was observed in MIOX-KO mice (E and F). A marked expression of MIOX was noted in Ins2Akita mice, which was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (H vs. G). The MIOX activity increased both in WT and in MIOX-TG mice considerably in diabetic state, and it was notably higher in the MIOX-TG mice (I). The MIOX activity was relatively high in Ins2Akita mice, and it was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (I). The MI concentration was relatively high both in the serum and kidney cortices of MIOX-KO mice, compared with WT and MIOX-TG mice (J and K). It was reduced in diabetic WT, MIOX-TG, and MIOX-KO mice. The MI concentration was low both in the serum and in the kidney cortices of Ins2Akita mice, and it was significantly increased in Ins2Akita/KO mice (J and K). Each IMF image is representative of four individual mouse kidneys of a given group. Insets depict higher magnification of the photomicrographs. *P < 0.01; #P < 0.05. (n = 6 for bar graph data.) CON, control; Conc., concentration.

Modulation of ROS Generation by MIOX Expression Profile in Diabetic State

Oxidant stress is regarded as one of the major denominators in the pathogenesis of DN (38). In view of this biologic precept and the association of increased MIOX expression with oxidant stress in models of AKI (30), we assessed the status of ROS in various strains of mice. An increased 2’-7’-dichlorofluroescein diacetate (DCF-DA)–associated fluorescence was observed in the tubular cytosolic compartment in diabetic WT mice (Fig. 3B vs. Fig. 3A). In MIOX-TG mice, the fluorescence could be seen in the nondiabetic mice, and it markedly increased in diabetic MIOX-TG mice (Fig. 3D vs. Fig. 3C). MIOX-KO mice had a mild increase of DCF-associated fluorescence in a hyperglycemic state (Fig. 3F vs. Fig. 3E). Ins2Akita mice had a notably high DCF-associated fluorescence under basal conditions, and it decreased in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 3H vs. Fig. 3G). The status of mitochondrial ROS was evaluated using DHE, and the perturbations were similar to those seen for cytosolic ROS. Both WT and MIOX-KO mice had minimal DHE-associated fluorescence (Fig. 3I and M). However, basal DHE reactivity was readily noticeable in MIOX-TG mice and it increased markedly in a hyperglycemic state (Fig. 3L vs. Fig. 3K). Ins2Akita mice also had a notable DHE-associated fluorescence, and it was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 3P vs. Fig. 3O). These redox perturbations were also reflected in other oxidant stress parameters. NOX4 expression increased in a hyperglycemic state—highest in diabetic MIOX-TG mice while low in MIOX-KO mice (Fig. 3Q, upper panel). The Ins2Akita mice also had marked NOX4 expression, which was mitigated in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 3Q, lower panel). Similarly, under basal control conditions, the NAD+-to-NADH and GSH-to-GSSG ratios were quite high in WT and MIOX-KO mice and relatively low in MIOX-TG and Ins2Akita mice (Fig. 3R and S). The ratios were decreased in a diabetic state and were even lower in diabetic MIOX-TG mice. Both NAD+-to-NADH and GSH-to-GSSG ratios were low in Ins2Akita mice kidneys, and they were increased in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 3R and S), suggesting that MIOX-KO mice normally are shielded from oxidant stress and MIOX gene disruption exerts a rescuing effect.

Figure 3.

Effect of MIOX expression profile on the generation of ROS and parameters reflective of cellular redox in diabetic mice. An increased fluorescence of DCF-DA staining was observed in diabetic WT mice, suggesting an enhanced generation of ROS in the cytosolic compartment of the renal tubules (B vs. A). Mild fluorescence was seen in MIOX-TG mice, and it increased in diabetic state (D vs. C). MIOX-KO mice had minimal DCF-associated fluorescence, and a mild increase was observed in diabetic state (F vs. E). The Ins2Akita mice had a marked DCF-associated fluorescence, and it was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (H vs. G). Likewise, similar perturbations in the mitochondrial ROS, as reflected by DHE-associated fluorescence, were observed. Both WT and MIOX-KO mice revealed minimal DHE-associated fluorescence under basal control conditions (I and M). However, basal DHE fluorescence was readily notable in MIOX-TG mice, and it increased markedly in hyperglycemic state (L vs. K). Also, Ins2Akita mice had a marked DHE fluorescence, and it was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (P vs. O). The NOX4 protein expression increased in hyperglycemic state, and the highest increase was observed in diabetic MIOX-TG mice (Q, upper panel). A marked protein expression of NOX4 was seen in Ins2Akita mice, which was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Q, lower panel). The NAD+-to-NADH and GSH-to-GSSG ratios were high in WT and MIOX-KO mice and relatively low in MIOX-TG and Ins2Akita mice (R and S). The ratios were decreased in diabetic state, and this decrease was highly accentuated in MIOX-TG mice. Both the NAD+-to-NADH and GSH-to-GSSG ratios were low in the kidneys of Ins2Akita mice, and they were significantly increased in Ins2Akita/KO mice (R and S). Each IMF image is representative of four individual mouse kidneys of a given group. Insets depict higher magnification of the photomicrographs. *P < 0.01; #P < 0.05. (n = 6 for bar graph data). CON, control.

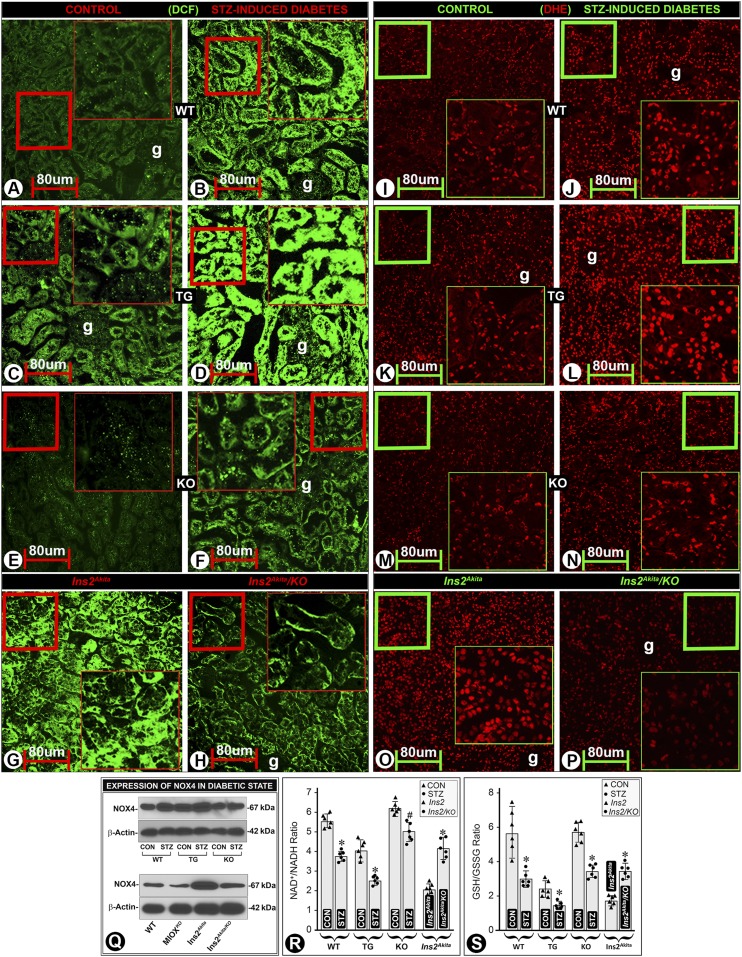

MIOX Overexpression Leads to an Increased Generation of ROS in HK-2 Cells

To establish the notion that ROS generation is directly related to MIOX overexpression, we subjected HK-2 cells transfected with MIOX pcDNA to HG (30 mmol/L) ambience. Transfection led to an increased DHE fluorescence under low glucose (LG) (5 mmol/L) ambience, which increased tremendously under HG (Fig. 4A–D). DHE fluorescence was related to ROS generation, since NAC treatment reduced the fluorescence (Fig. 4E and F). A mild fluorescence was observed in cells subjected to LG or HG ambience with l-glucose, and it increased slightly following MIOX pcDNA transfection (Fig. 4G–J). These changes were confirmed by flow cytometric analyses (Fig. 4K–P). The quantitation revealed an increase in the mean fluorescence intensity in cells subjected to HG ambience but more so in cells overexpressing MIOX, while it was notably reduced following NAC treatment (Fig. 4Q).

Figure 4.

Effect of up- and downregulated MIOX expression on the generation of ROS in HK-2 cells under HG ambience. Under LG ambience (5 mmol/L), a mild basal DHE-associated fluorescence was observed, and it increased in cells transfected with MIOX pcDNA (B vs. A). Under HG ambience (30 mmol/L), the fluorescence increased (D vs. C). NAC treatment reduced the intensity of fluorescence (E and F), suggesting that DHE-associated fluorescence was related to the ROS generation. The cells treated with l-glucose had minimal fluorescence (panels G and I), and it increased slightly with MIOX pcDNA transfection (panels H and J). Flow cytometric analyses confirmed the results obtained by DHE fluorescence (panels K–P). The mean fluorescence intensity increased in MIOX-overexpressing cells, which was reduced with the NAC treatment (Q), suggesting that the MIOX overexpression accentuates oxidant stress under HG ambience. Insets depict higher magnification of the photomicrographs. *P < 0.01. (n = 6 for bar graph data.) EMP-VE, empty vector.

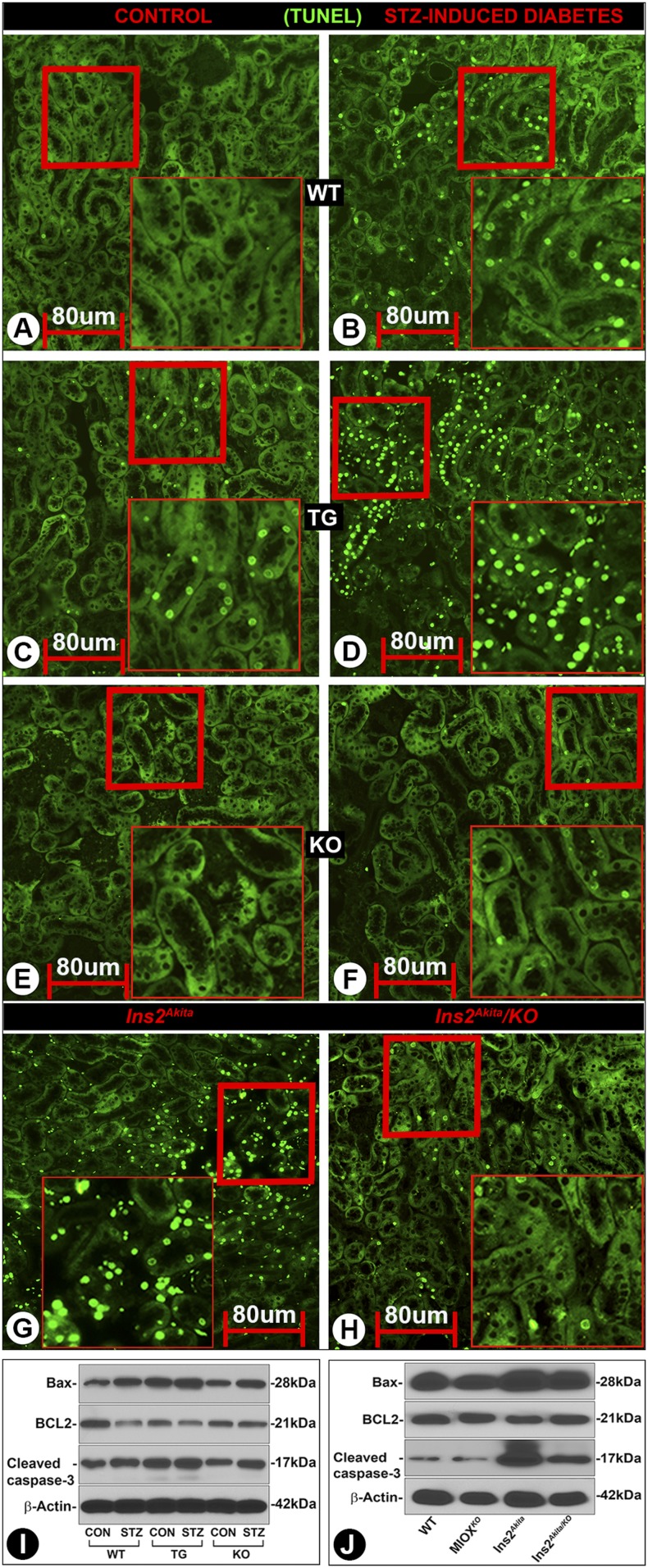

MIOX Overexpression Accentuates, While MIOX Gene Ablation Mitigates, Tubular Apoptosis in Diabetic State

ROS-induced DNA damage (apoptosis) was assessed by the TUNEL method. An increased apoptosis was observed in diabetic WT mice (Fig. 5B vs. Fig. 5A). It was highly accentuated in diabetic MIOX-TG mice (Fig. 5D vs. Fig. 5C). Minimal apoptosis was observed in diabetic or nondiabetic MIOX-KO mice (Fig. 5E and F). Fulminant apoptosis was observed in Ins2Akita mice, which was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 5G and H). Parallel changes were observed in the executionary molecules of apoptosis. An increased expression of Bax and cleaved caspase-3 was observed in diabetic WT mice, while Bcl2 was decreased (Fig. 5I). Bax and cleaved caspase-3 basal expression was relatively high in MIOX-TG mice and increased further in a diabetic state, while Bcl2 was reduced. Interestingly, basal expression of Bax and cleaved caspase-3 was high in Ins2Akita mice and was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 5J).

Figure 5.

Status of tubular cell apoptosis with changes in the MIOX expression profile in diabetic state. An increased tubular cell apoptosis was observed in diabetic WT mice compared with control (B vs. A). It was accentuated in diabetic MIOX-TG mice (D vs. C). No significant apoptosis was noted in MIOX-KO mice (E and F). The Ins2Akita mice revealed marked apoptosis, which was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (G and H). Immunoblot analyses revealed an increased expression of Bax and cleaved caspase-3 in kidneys of diabetic WT mice, while the Bcl2 expression was reduced (I). Basal expression of Bax and cleaved caspase-3 was relatively high in MIOX-TG mice, and it was accentuated in diabetic state. A mild to moderate increased expression of Bax and cleaved caspase-3 was noted in diabetic MIOX-KO mice, while no significant change in the Bcl2 expression was observed. A high expression of Bax and cleaved caspase-3 was seen in Ins2Akita mice, while that of Bcl2 was relatively low. These perturbations in Bax, Bcl2, and cleaved caspase-3 were notably reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (J). Insets depict higher magnification of the photomicrographs. Each IMF image and immunoblot is representative of four individual mice kidneys of a given group. CON, control.

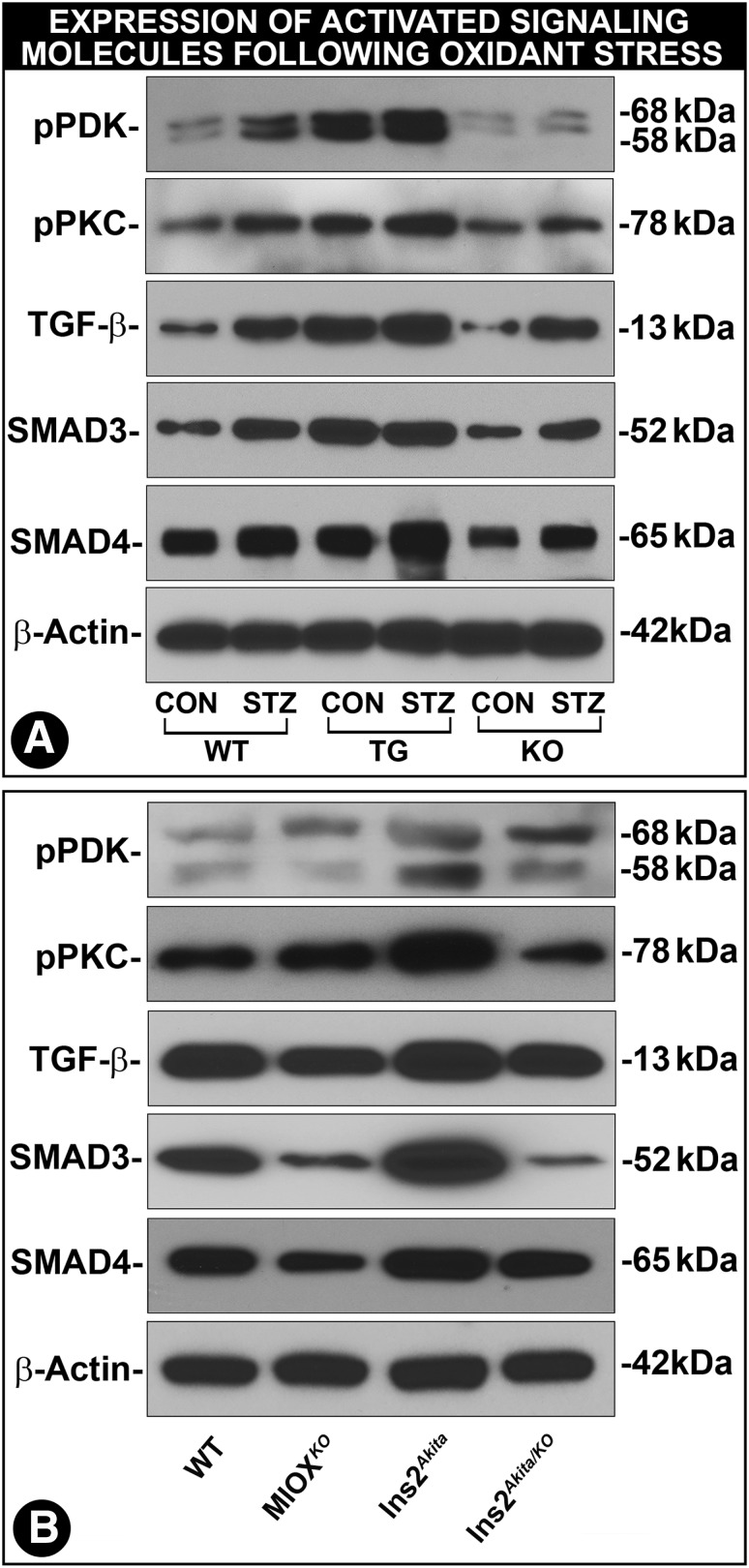

Perturbations in Kinase-Mediated Cellular Signaling Events Associated with MIOX Expression Profile

The foremost upstream kinase of TGF-β signaling would conceivably be phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK-1), a master kinase that regulates the activity of other kinases (39). Its activity increases following phosphorylation under the influence of growth factors and plausibly also by MIOX-induced oxidant stress (40). An increased expression of phosphorylated (p)PDK-1 was observed in kidneys of diabetic WT, MIOX-TG, and MIOX-KO mice, with the highest being in diabetic MIOX-TG mice (Fig. 6A). The pPDK-1 expression was also high in Ins2Akita mice and low in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 6B). PDK-1 phosphorylates a number of kinases, including PKC, and renders them catalytically active (41). The pPKC expression paralleled that of pPDK-1 (Fig. 6A and B). PKC is upregulated in diabetic states, and it modulates the expression of TGF-β (42,43). TGF-β expression was highest in diabetic MIOX-TG and Ins2Akita mice, and it was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 6B). Both Smad3 and Smad4 exhibited changes similar to those seen in the upstream kinases and TGF-β (Fig. 6A and B). These observations suggested that the entire spectrum of signaling cascade is modulated by the overexpression of MIOX, most likely via augmentation of oxidant stress.

Figure 6.

Modulation of kinase-mediated cellular signaling by MIOX expression profile in various strains of mice in diabetic state. An increased expression of pPDK-1 in kidneys of diabetic WT, MIOX-TG, and MIOX-KO mice was observed (A). The highest increased expression of pPDK-1 was observed in diabetic MIOX-TG mice. It was also relatively high in kidneys of Ins2 Akita mice, and it was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (B). Expression of pPKC paralleled that of pPDK-1 (A and B). An increased expression of TGF-β was seen in diabetic WT, MIOX-TG, and MIOX-KO mice. The highest upregulation of TGF-β was observed in diabetic MIOX-TG mice. The TGF-β expression was also high in kidneys of Ins2Akita mice, and it was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (B). Both Smad3 and Smad4 revealed changes in their expression parallel to those seen in upstream kinases (A and B). These findings suggest that MIOX overexpression accentuates kinase signaling possibly via augmentation of MIOX-mediated oxidant stress. Each immunoblot is representative of four individual mice kidneys of a given group. CON, control.

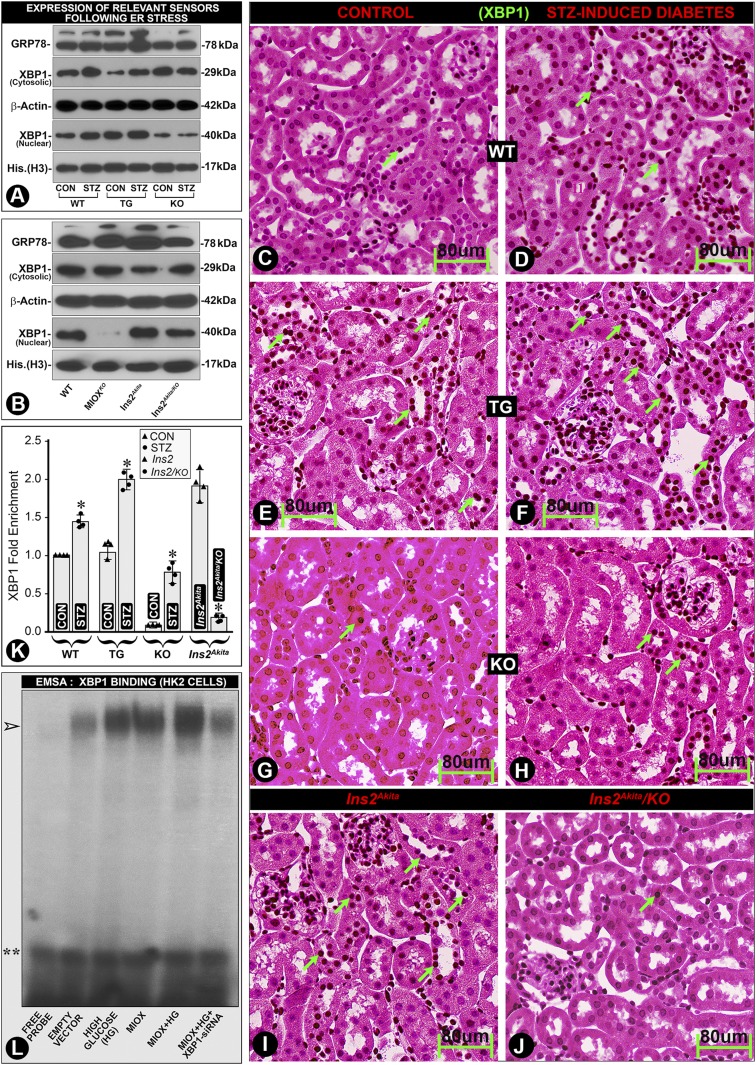

Modulation of ER Stress Sensors by MIOX Overexpression

Recent reports indicate a role of ER stress in the pathogenesis of DN (33,44). In this regard, two key ER sensors, i.e., X-Box Binding Protein 1 (XBP1), a transcription factor, and 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78), a chaperone, were investigated. An accentuated renal expression of XBP1 (nuclear) and GRP78 in diabetic MIOX-TG mice was observed, suggesting that MIOX augments ER stress (Fig. 7A). The GRP78 expression was high in Ins2Akita mice, and it was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 7B). Our in silico analysis revealed the presence of XBP1-binding motifs in the MIOX promoter. XBP1 expression paralleled that of GRP78 with MIOX overexpression in the cytosolic fraction in diabetic WT and MIOX-TG mice, but more so in the nuclear fraction, suggesting cytoplasm-to-nuclear translocation (Fig. 7A). XBP1 nuclear translocation was readily seen in Ins2Akita mice, and it was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 7B). Immunohistochemistry procedures also showed a marked nuclear translocation/localization in renal tubules of diabetic MIOX-TG and Ins2Akita mice, and it was notably reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 7F vs. Fig. 7E and J vs. Fig. 7I, arrows). These observations suggest a possible intertwined and a cyclical-feedback relationship of MIOX and XBP1 in the progression of diabetic tubulopathy. Such an increased DNA-protein interaction in states of MIOX overexpression was also reflected in the ChiP assays where a marked XBP1 enrichment was seen in diabetic MIOX-TG and Ins2 Akita mice, which was remarkably reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice, suggesting that these in vivo interactions are reduced by MIOX gene disruption (Fig. 7K). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays also revealed increased DNA-protein interaction under HG ambience, which was augmented by MIOX overexpression, as indicated by the increased intensity of the band (Fig. 7L, arrowhead, lane five). XBP1 siRNA reduced these DNA-protein interactions, as reflected by decreased intensity of the band (Fig. 7L, arrowhead, lane six).

Figure 7.

Modulation of ER stress sensors by MIOX overexpression under HG ambience. A slight increased expression of GRP78 was observed in kidneys of diabetic WT and MIOX-KO mice, and it was highly accentuated in diabetic MIOX-TG mice (A). The GRP78 expression was also high in Ins2Akita mice, and it was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (B). The XBP1 expression paralleled that of GRP78. A notable increase in the cytoplasmic/nuclear expression of XBP1 was observed in diabetic WT and MIOX-TG mice (A). Minimal nuclear translocation of XBP1 was observed in MIOX-KO mice (A). A significant nuclear translocation of XBP1 was seen in Ins2Akita mice, which was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (B). Immunohistochemistry revealed minimal XBP1 nuclear localization (dark brown nuclei) in WT mice, and it increased in hyperglycemic state (D vs. C, green arrows). MIOX-TG mice revealed a notable XBP1 nuclear staining, and it markedly increased in diabetic state (F vs. E). Minimal nuclear translocation of XBP1 was observed in MIOX-KO mice (H vs. G). There was a remarkable XBP1 nuclear reactivity in Ins2Akita mice, which was reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (J vs. I, green arrows). ChiP assays confirmed the renal nuclear enrichment of XBP1 following its translocation in various strains of mice (K). The DNA-protein interactions were also confirmed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) in HK-2 cells. An increased intensity of the band was observed under HG ambience and following MIOX pcDNA transfection, and the intensity was further accentuated with the combined treatment (L, lanes 3–5, arrowhead). Intensity of the band was reduced by XBP1 siRNA treatment (panel L, last lane to the right). Double asterisks indicate free probe. Each immunohistochemistry image is representative of four individual mice kidneys of a given group. *P < 0.01. (n = 4 for bar graph data.) His., histone.

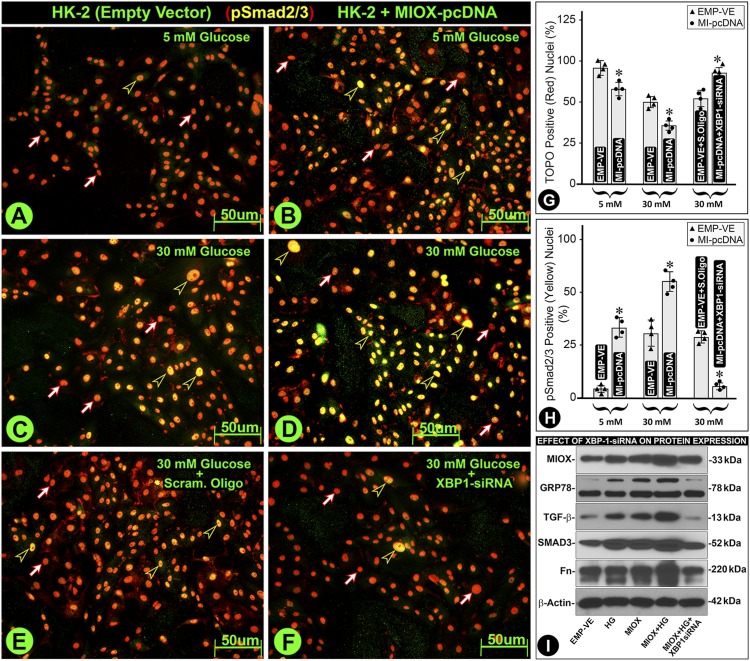

Role of XBP1 in the Modulation of Signaling Molecules Relevant to Extracellular Matrix Pathobiology in HK-2 Cells

To tease out the intricate interrelationship between MIOX and XBP1 relevant to ER stress and TGF-β–initiated fibrogenesis, we performed in vitro experiments. Downstream of TGF-β is the activation of pSmad2/3, which translocates into the nucleus and binds to the promoter of extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules and thereby causing fibrosis (45). Under LG (5 mmol/L) ambience, minimal pSmad2/3 translocation was observed, since 95% nuclei retained TOPO red dye fluorescence (Fig. 8A, red-white arrows, and Fig. 8G). A marked pSmad2/3 translocation was observed under HG (30 mmol/L) ambience, and it was augmented in MIOX-overexpressing cells (Fig. 8C and D, black-yellow arrowheads, and Fig. 8H). The yellow color of nuclei indicates colocalization of dye TOPO (red) and anti-pSmad2/3 antibody (green). Treatment of XBP1 siRNA decreased pSmad2/3 nuclear translocation, as highlighted by reduced population of yellow-colored nuclei (Fig. 8F, black-yellow arrowheads). Parallel results were observed in immunoblotting studies (Fig. 8I). Interestingly, the increased expression of fibronectin (Fn) was notably reduced with XBP1 siRNA, suggesting that ER and oxidant stress together may contribute to the increased de novo synthesis of ECM molecules under HG ambience in MIOX-overexpressing cells (Fig. 8I).

Figure 8.

Role of XBP1 in the modulation of signaling molecules relevant to ECM pathobiology in HK-2 cells. Under LG (5 mmol/L) ambience, there was a minimal nuclear translocation of pSmad2/3, and most of the nuclei without translocation stained red with TOPO dye (A, red-white arrows). With the MIOX pcDNA transfection, a certain degree of nuclear translocation of pSmad2/3 was observed, and the nuclei stained yellow (B, black-yellow arrowheads). The yellow color is due to the combination of red dye and anti-Smad antibody conjugated with fluorescein (green). A notable translocation of pSmad2/3 was observed under HG (30 mmol/L) ambience, which was accentuated in MIOX-overexpressing cells (C and D, black-yellow arrowheads). Treatment of MIOX-overexpressing HK-2 cells with XBP1 siRNA led to a notable decrease in the pSmad2/3 nuclear translocation, as indicated by the reduced population of yellow-colored nuclei (panel F, black-yellow arrowheads). The quantitation of pSmad2/3 nuclear translocation (red nuclei vs. yellow nuclei) is included in G and H. The treatment of XBP1 siRNA also affected the upstream molecules involved in oxidant stress, i.e., MIOX; ER stress, i.e., GRP78; and signaling molecules relevant to the induction of fibrosis, i.e., TGF-β and Smad2/3 (I). The increased expression of these molecules under HG ambience was dampened by the XBP1 siRNA. Also, the increased expression of Fn was notably reduced with XBP1 siRNA, suggesting that ER and oxidant stress together contribute to the changes in the ECM molecules. Each IMF image and immunoblot is representative of four individual cell culture experiments of a given group. *P < 0.01. (n = 4 for bar graph data.) EMP-VE, empty vector; Scram, scrambled oligo.

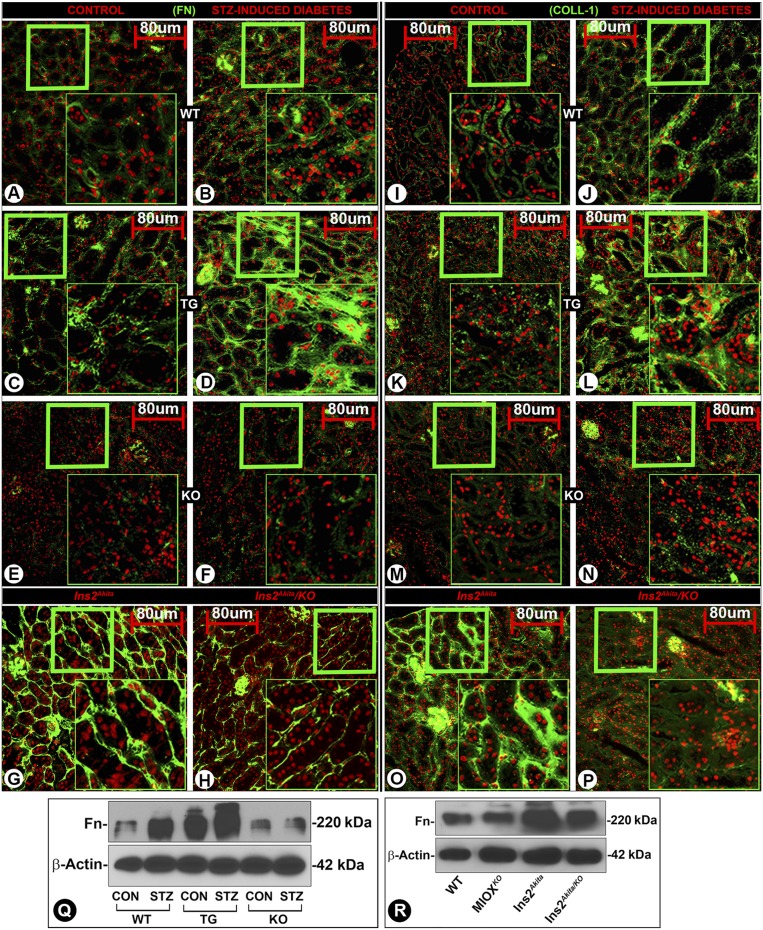

MIOX Overexpression in Diabetic State Accentuates Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis

A mild increased renal expression of Fn and Collagen-1 (Coll-1) was observed in diabetic WT mice (Fig. 9B and J), whereas a markedly increased expression was noted in diabetic MIOX-TG mice (Fig. 9D and L). MIOX-KO mice had minimal expression of ECM proteins (Fig. 9E, F, M, and N). Parallel changes were observed in the Fn expression by immunoblot analyses (Fig. 9Q). A high expression of Fn and Coll-1 was observed in the tubulointerstitium of Ins2Akita mice (Fig. 9G and O), and it was notably reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 9H and P). Likewise, parallel changes were observed in the expression of Fn by immunoblotting (Fig. 9R). These observations suggested that MIOX overexpression primes the exacerbation of tubulointerstitial injury, conceivably by induction of oxidant and ER stress, and modulation of signaling events leading to increased synthesis of ECM proteins.

Figure 9.

Accentuation of ECM proteins’ synthesis and renal fibrosis in various strains of mice with MIOX overexpression. A minimal expression of Fn or Coll-1 was observed in kidneys of WT mice (A and I), and a mild increase was seen in diabetic state (B and J). The MIOX-TG mice had mild expression of ECM in the tubulointerstitial compartment of the kidney (C and K), while it was highly accentuated in diabetic state (D and L). The MIOX-KO had minimal expression of ECM proteins (E, F, M, and N). Parallel changes in the Fn expression were observed in WT, MIOX-TG, and MIOX-KO mice by immunoblot methods (Q). The Ins2Akita mice heavily expressed both of the ECM proteins, i.e., Fn and Coll-1, in the tubulointerstitial compartment (G and O), and these were considerably reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (H and P). Parallel changes were observed in the expression of Fn in Ins2Akita and Ins2Akita/KO mice by Western blotting procedures (R). Insets depict higher magnification of the photomicrographs. Each IMF image and immunoblot is representative of four individual mice kidneys of a given group. CON, control.

Discussion

This investigation is based on the notion that MIOX expression modulates outcome of tubulointerstitial injury in diabetic state by regulating various signaling pathways, and our results attest to this contention and yield a glimpse at the relevant mechanisms.

At the outset, a germane question relates to body homeostasis pertinent to renal pathophysiology in various strains of mice. Among them, MIOX-TG mice had the lowest body weight, which decreased further in diabetic state (Fig. 1), which may due to the deficiency of MI. In this regard, MI supplementation has been reported to exert a growth-promoting effect in other systems (46). Such dietary supplemental experiments relating to kidney pathobiology need to be performed, which would be the subject matter of future investigations. In addition, MIOX-TG diabetic mice had greater worsening of renal functions, as reflected in the serum creatinine, cystatin C, and urea levels; ACR and urinary protein excretion; and KIM-1 concentration. Such deterioration of renal functions has been observed in MIOX-TG mice in other forms of chemical injuries (30,36), which was thought to be due to the oxidant stress induced by MIOX overexpression. Since oxidant stress is well-known in the progression of DN, it is likely that excessive generation of ROS played a role in worsening of renal injury. Here, it is reasonable to assume that MIOX gene disruption (MIOX-KO) would ameliorate renal injury. This notion is supported by the results in double mutant (MIOX-KO × Ins2Akita) mice where renal derangements were notably lessened. Of note, Ins2Akita/KO mice had minimal expression/activity of MIOX and high tissue and serum MI levels, suggesting that MIOX deficiency rescues from injury, while hyperglycemia-induced increased MIOX expression in diabetic MIOX-TG mice worsens renal homeostasis (Fig. 2). Here, it is conceivable that MI deficiency worsens the renal homeostasis, as elegantly surmised by Chang et al. (28). Nevertheless, the data included in results also suggest that other factors, e.g., oxidant stress, play a significant role in the progression of renal injury, as described in cisplatin-induced AKI models (30,47).

Interestingly, ROS-mediated perturbations were confined to proximal tubules where MIOX is expressed (Fig. 3). Potential sources of ROS generation include mitochondrial respiratory chain, polyol pathway, advanced glycation end products, NADH/NADPH, and possibly the G-X pathway (15,21,22,30,38). ROS are capable of oxidizing proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and DNA, including mitochondrial DNA, thereby causing cellular dysfunctions. The nephron segment that is most adversely affected is the proximal tubule for many reasons. First, 90% of filtered glucose is taken up by them, which is mediated by transporters like SGLT2 and GLUT2 (48). As a consequence, there is increased glycolysis with excessive generation of ROS via various mechanisms. Secondly, the proximal tubules are enriched with mitochondria that are involved in the generation of ATP via oxidative phosphorylation in the respiratory chain complex. With the increased load on this complex, there will be excessive leakage of electrons at various levels of respiratory chain with excessive generation of superoxide anion (O2−) (15,21,22). Thirdly, NAD(P)H oxidase has been identified in the proximal tubules, i.e., NOX4 (49). NAD(P)H oxidase catalyzes the generation of O2− by reducing molecular O2 using either NADPH or NADH. Fourthly, the proximal tubular mitochondria do not synthesize glutathione but derive it with the aid of organic anion carriers (49,50). Lastly, the upregulation of MIOX may lead to changes in NAD+-to-NADH ratio and perturbations in cellular redox via the G-X pathway (Supplementary Fig. 1). Since MIOX promoter includes oxidant response elements, oxidant stress would lead to cyclic upregulation of MIOX and a relentless oxidant stress (27). In view of the above, it is likely that proximal tubules have an enhanced vulnerability to oxidant stress. Apparently, tubular expression of MIOX and its cyclical upregulation following hyperglycemia make the matter worse. This contention is supported by our studies describing increased oxidant stress in diabetic MIOX-TG mice, as highlighted by DCF staining that detects H2O2 (Fig. 3). Also, a reduction of DCF staining in kidneys of Ins2Akita/KO mice strengthens our contention. The major source of O2− is the respiratory chain, and it would reflect mitochondrial status, detected by DHE staining. DHE is seen as nuclear fluorescence, since the oxidized DHE intercalates into the DNA (51,52). Like DCF, the DHE staining was also markedly increased in diabetic MIOX-TG mice, while reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice (Fig. 3). Of note, ROS generation by mitochondria is influenced by NADH and FADH2 in the cytosol, since they serve as electron donors to the mitochondrial respiratory complex (15). On the other hand, the O2− generated in the mitochondria readily translocates into the cytosol (53), meaning thereby that the biology of ROS generation in these compartments is intertwined. Another potential source of ROS generation identified in our study was the NADPH oxidase system (49). An increased expression of tubular NOX4 in MIOX-TG and Ins2Akita mice, while notably reduced in Ins2Akita/KO mice, would be in line with the above assertion (Fig. 3). Other perturbations where MIOX seems to augment ROS-mediated cellular injury include altered ratios of NAD+ to NADH and GSH to GSSG (Fig. 3). During glycolysis, glucose is metabolized into pyruvate with the conversion of NAD+ to NADH; the latter serves as an electron donor (15,21). Also, glucose is handled via polyol pathway where NAD+ is converted to NADH (54,55). With the increased availability of glucose and augmented activity of various pathways, an increased consumption of NAD+, its deficiency, and altered NAD+-to-NADH ratio would be anticipated. Likewise, altered GSH-to-GSSG ratio, a measure of oxidant stress, has been reported in DN (56,57). Here, it is conceivable that an altered ratio may be because MIOX per se contributes, to a certain extent, to the depletion of GSH via reducing NADPH levels (58). Nevertheless, it is known that GSH protects the cell by neutralizing the ROS, and excessive amounts of ROS in the cellular pool would be anticipated to cause notable deficiency of GSH and thereby an altered ratio (58). Also, hyperglycemia associated with increased activity of glutathione peroxidase and low levels of dicarboxylate and 2-oxoglutarrate would also contribute to GSH deficiency in diabetic tubulopathy (50). To address the issue that MIOX per se can cause generation of ROS, cell culture experiments were performed (Fig. 4). HK-2 cells transfected with MIOX pcDNA had increased DHE fluorescence at LG ambience, which was augmented at HG ambience. It was reduced by N-acetylcysteine treatment, suggesting that DHE fluorescence is related to mitochondrial ROS. These morphologic findings were also supported by flow cytometric analyses (Fig. 4). One of the well-described hyperglycemia-induced ROS-mediated damages is apoptosis, which is associated with changes in the profile of Bax and cleaved caspase-3 (15). ROS facilitate the release of cytochrome C from mitochondria with increased permeabilization of their outer membrane, formation of apoptosomes, caspase 3/8 activation, and tubular apoptosis (49,59). The accentuated expression of Bax and cleaved caspase-3 in MIOX-TG mice indicates that these alterations are related to MIOX-mediated increased oxidant stress. The fact that these perturbations were normalized in Ins2Akita/KO mice would support the contention that augmented apoptosis is related to the increased ROS generation (Fig. 5).

Besides apoptosis, ROS can initiate the activation of various signaling kinases, e.g., PKC, followed by induction of growth-promoting cytokines, i.e., TGF-β, leading to tubulointerstitial injury/fibrosis (60). Other signaling cascades that are also ROS activated include PKB/Akt and PDK-1, although studies describing their role in ROS-mediated induction following hyperglycemia are limited (40,49,61). The fact that we observed increased expression of pPDK-1 in diabetic MIOX-TG strongly suggests that hyperglycemia/MIOX-induced ROS generation modulates pPDK-1 expression (Fig. 6). Moreover, reduction of pPDK-1 expression in MIOX-KO and Ins2Akita/KO mice would suggest that the MIOX expression profile is intricately involved in the activation of pPDK and the parallel downstream events, including pPKC, increased TGF-β expression, and Smads’ activation. This indicates that the entire signaling cascade initiated by pPDK-1 is operational, which would lead to tubulointerstitial injury/fibrosis (Fig. 6).

Conceivably, oxidative damage to proteins leads to their inappropriate folding and ER stress; the latter also plays a role in the pathogenesis of DN (33,34). That there was an increased renal expression of GRP78, an important chaperone in unfolded protein response, and an increased nuclear translocation of XBP1, a key transcription factor of unfolded protein response, in the tubular compartment of diabetic MIOX-TG, would suggest that they are afflicted by ER stress (Fig. 7). Moreover, normalization of these changes to baseline in Ins2Akita/KO mice and minimal nuclear translocation of XBP1 in MIOX-KO mice would suggest that ER stress accentuated by MIOX overexpression plays a role in the pathogenesis of diabetic tubulopathy (Fig. 7). The relevance of MIOX in ER stress is further strengthened by the discovery of XBP1-binding elements in MIOX promoter, suggesting a reciprocal relationship between MIOX and XBP1 in which they can regulate each other. Also, XBP1 can regulate the signaling cascade that leads to tubulointerstitial fibrosis, since MIOX-overexpressing cells had an increased expression of TGF-β, Smad3, and Fn under HG ambience, while significantly decreasing with the XBP1 siRNA treatment (Fig. 8). The observation that XBP1 siRNA also dampened pSmad2/3 nuclear translocation strongly suggests that the molecules that are an integral part of ER stress response also modulate the signaling cascade that downstream regulate the synthesis of ECM proteins like Fn or collagen-1 (Coll-1) (Fig. 8).

The most downstream event of hyperglycemia-induced injury is increased synthesis of ECM proteins, leading to interstitial fibrosis (15,18,20,42,62). Likewise, we observed slightly increased expression of Fn/Coll-1 in diabetic WT mice (Fig. 9). An interesting finding was marked increased expression of Fn/Coll-1 in diabetic MIOX-TG, attributable to MIOX overexpression and a multitude of downstream signaling events. The most important finding of this investigation was the remarkably reduced expression of Fn/Coll-1 in the tubulointerstitial compartment in Ins2Akita/KO mice compared with Ins2Akita mice (Fig. 9).

In summary, this investigation highlights that MIOX overexpression worsens the outcome of DN, possibly by accentuating the activity of oxidant and ER stress processes, while its gene ablation ameliorates tubulointerstitial injury. Finally, it is quite conceivable that these processes may mutually boost the actions of each other, which would accelerate the progression of diabetic tubulopathy (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors thank K.S. Pabhu (The Pennsylvania State University) for allowing them to adapt Supplementary Fig. 1B (25).

Funding. This study was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH, grant DK60635.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. I.S. designed and performed the experiments. F.D., Y.L., and Y.S.K. wrote and edited the manuscript. I.S. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/db20-4567/suppl.11965356.

References

- 1.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 2001;414:813–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheetz MJ, King GL. Molecular understanding of hyperglycemia’s adverse effects for diabetic complications. JAMA 2002;288:2579–2588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reusch JE. Diabetes, microvascular complications, and cardiovascular complications: what is it about glucose? J Clin Invest 2003;112:986–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LeRoith D, Taylor SI, Olefsky JM. Diabetes Mellitus: A Fundamental and Clinical Text. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott William & Wilkins, 2004, p. 1–1540 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma K. Obesity and diabetic kidney disease: role of oxidant stress and redox balance. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016;25:208–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raj DS, Choudhury D, Welbourne TC, Levi M. Advanced glycation end products: a Nephrologist’s perspective. Am J Kidney Dis 2000;35:365–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kato M, Wang M, Chen Z, et al. An endoplasmic reticulum stress-regulated lncRNA hosting a microRNA megacluster induces early features of diabetic nephropathy. Nat Commun 2016;7:12864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badal SS, Danesh FR. New insights into molecular mechanisms of diabetic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;63(Suppl. 2):S63–S83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brosius FC III, Kaufman RJ. Is the ER stressed out in diabetic kidney disease? J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;19:2040–2042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peti-Peterdi J, Kang JJ, Toma I. Activation of the renal renin-angiotensin system in diabetes--new concepts. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23:3047–3049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fioretto P, Mauer M. Histopathology of diabetic nephropathy. Semin Nephrol 2007;27:195–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallipattu SK, He JC. The podocyte as a direct target for treatment of glomerular disease? Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2016;311:F46–F51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu J, Lee K, Chuang PY, Liu Z, He JC. Glomerular endothelial cell injury and cross talk in diabetic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2015;308:F287–F297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhan M, Usman IM, Sun L, Kanwar YS. Disruption of renal tubular mitochondrial quality control by Myo-inositol oxygenase in diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;26:1304–1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanwar YS, Sun L, Xie P, Liu FY, Chen S. A glimpse of various pathogenetic mechanisms of diabetic nephropathy. Annu Rev Pathol 2011;6:395–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenzel UO, Fouqueray B, Biswas P, Grandaliano G, Choudhury GG, Abboud HE. Activation of mesangial cells by the phosphatase inhibitor vanadate. Potential implications for diabetic nephropathy. J Clin Invest 1995;95:1244–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang SCW, Leung JCK, Lai KN. Diabetic tubulopathy: an emerging entity. Contrib Nephrol 2011;170:124–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forbes JM, Harris DC, Cooper ME. Report on ISN forefronts, Melbourne, Australia, 4-7 October 2012: tubulointerstitial disease in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 2013;84:653–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert RE. Proximal tubulopathy: prime mover and key therapeutic target in diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes 2017;66:791–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma I, Tupe RS, Wallner AK, Kanwar YS. Contribution of myo-inositol oxygenase in AGE:RAGE-mediated renal tubulointerstitial injury in the context of diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2018;314:F107–F121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giacco F, Brownlee M. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ Res 2010;107:1058–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kashihara N, Haruna Y, Kondeti VK, Kanwar YS. Oxidative stress in diabetic nephropathy. Curr Med Chem 2010;17:4256–4269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ying W. NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH in cellular functions and cell death: regulation and biological consequences. Antioxid Redox Signal 2008;10:179–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cowley BD Jr., Ferraris JD, Carper D, Burg MB. In vivo osmoregulation of aldose reductase mRNA, protein, and sorbitol in renal medulla. Am J Physiol 1990;258:F154–F161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prabhu KS, Arner RJ, Vunta H, Reddy CC. Up-regulation of human myo-inositol oxygenase by hyperosmotic stress in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 2005;280:19895–19901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nayak B, Xie P, Akagi S, et al. Modulation of renal-specific oxidoreductase/myo-inositol oxygenase by high-glucose ambience. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:17952–17957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nayak B, Kondeti VK, Xie P, et al. Transcriptional and post-translational modulation of myo-inositol oxygenase by high glucose and related pathobiological stresses. J Biol Chem 2011;286:27594–27611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang HH, Chao HN, Walker CS, Choong SY, Phillips A, Loomes KM. Renal depletion of myo-inositol is associated with its increased degradation in animal models of metabolic disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2015;309:F755–F763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tominaga T, Dutta RK, Joladarashi D, Doi T, Reddy JK, Kanwar YS. Transcriptional and translational modulation of myo-inositol oxygenase (Miox) by fatty acids: implications in renal tubular injury induced in obesity and diabetes. J Biol Chem 2016;291:1348–1367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dutta RK, Kondeti VK, Sharma I, Chandel NS, Quaggin SE, Kanwar YS. Beneficial effects of myo-inositol oxygenase deficiency in cisplatin-induced AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;28:1421–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang B, Hodgkinson A, Millward BA, Demaine AG. Polymorphisms of myo-inositol oxygenase gene are associated with Type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications 2010;24:404–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunard R, Sharma K. The endoplasmic reticulum stress response and diabetic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2011;300:F1054–F1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan Y, Lee K, Wang N, He JC. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetic nephropathy. Curr Diab Rep 2017;17:17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hummasti S, Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation in obesity and diabetes. Circ Res 2010;107:579–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shu S, Zhu J, Liu Z, Tang C, Cai J, Dong Z. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is activated in post-ischemic kidneys to promote chronic kidney disease. EBioMedicine 2018;37:269–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tominaga T, Sharma I, Fujita Y, Doi T, Wallner AK, Kanwar YS. myo-Inositol oxygenase accentuates renal tubular injury initiated by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2019;316:F301–F315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamaguchi F, Ohshima T, Sakuraba H. An enzymatic cycling assay for nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate using NAD synthetase. Anal Biochem 2007;364:97–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forbes JM, Coughlan MT, Cooper ME. Oxidative stress as a major culprit in kidney disease in diabetes. Diabetes 2008;57:1446–1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang KJ, Shin S, Piao L, et al. Regulation of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) by Src involves tyrosine phosphorylation of PDK1 and Src homology 2 domain binding. J Biol Chem 2008;283:1480–1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prasad N, Topping RS, Zhou D, Decker SJ. Oxidative stress and vanadate induce tyrosine phosphorylation of phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1). Biochemistry 2000;39:6929–6935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newton AC. Regulation of the ABC kinases by phosphorylation: protein kinase C as a paradigm. Biochem J 2003;370:361–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iglesias-De La Cruz MC, Ruiz-Torres P, Alcamí J, et al. Hydrogen peroxide increases extracellular matrix mRNA through TGF-beta in human mesangial cells. Kidney Int 2001;59:87–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ha H, Yu MR, Choi YJ, Lee HB. Activation of protein kinase c-delta and c-epsilon by oxidative stress in early diabetic rat kidney. Am J Kidney Dis 2001;38(Suppl. 1):S204–S207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhandary B, Marahatta A, Kim HR, Chae HJ. An involvement of oxidative stress in endoplasmic reticulum stress and its associated diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2012;14:434–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meng XM, Tang PM, Li J, Lan HY. TGF-β/Smad signaling in renal fibrosis. Front Physiol 2015;6:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamaguchi Y, Kanzaki H, Miyamoto Y, et al. Nutritional supplementation with myo-inositol in growing mice specifically augments mandibular endochondral growth. Bone 2019;121:181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deng F, Sharma I, Dai Y, Yang M, Kanwar YS. myo-Inositol oxygenase expression profile modulates pathogenic ferroptosis in the renal proximal tubule. J Clin Invest 2019;129:5033–5049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mather A, Pollock C. Glucose handling by the kidney. Kidney Int Suppl 2011;120:S1–S6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ratliff BB, Abdulmahdi W, Pawar R, Wolin MS. Oxidant mechanisms in renal injury and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016;25:119–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lash LH. Mitochondrial glutathione in diabetic nephropathy. J Clin Med 2015;4:1428–1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bucana C, Saiki I, Nayar R. Uptake and accumulation of the vital dye hydroethidine in neoplastic cells. J Histochem Cytochem 1986;34:1109–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carter WO, Narayanan PK, Robinson JP. Intracellular hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion detection in endothelial cells. J Leukoc Biol 1994;55:253–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sena LA, Chandel NS. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell 2012;48:158–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu J, Jin Z, Zheng H, Yan LJ. Sources and implications of NADH/NAD(+) redox imbalance in diabetes and its complications. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2016;9:145–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan LJ. Redox imbalance stress in diabetes mellitus: role of the polyol pathway. Animal Model Exp Med 2018;1:7–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kakkar R, Mantha SV, Radhi J, Prasad K, Kalra J. Antioxidant defense system in diabetic kidney: a time course study. Life Sci 1997;60:667–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Winiarska K, Drozak J, Wegrzynowicz M, Fraczyk T, Bryla J. Diabetes-induced changes in glucose synthesis, intracellular glutathione status and hydroxyl free radical generation in rabbit kidney-cortex tubules. Mol Cell Biochem 2004;261:91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes 2005;54:1615–1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ott M, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S. Role of cardiolipin in cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Cell Death Differ 2007;14:1243–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shah SV, Baliga R, Rajapurkar M, Fonseca VA. Oxidants in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:16–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Han F, Xue M, Chang Y, et al. Triptolide suppresses glomerular mesangial cell proliferation in diabetic nephropathy is associated with inhibition of PDK1/Akt/mTOR pathway. Int J Biol Sci 2017;13:1266–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mason RM, Wahab NA. Extracellular matrix metabolism in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003;14:1358–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]