Abstract

Background:

Despite great technical advances in imaging, such as multidetector computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), diagnosing pancreatic solid lesions correctly remains challenging, due to overlapping imaging features with benign lesions. We wanted to evaluate functional MRI to differentiate pancreatic tumors, peritumoral inflammatory tissue, and normal pancreatic parenchyma by means of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI)-, diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI)-, and intravoxel incoherent motion model (IVIM) diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI)-derived parameters.

Methods:

We retrospectively analyzed 24 patients, each with histopathological diagnosis of pancreatic tumor, and 24 patients without pancreatic lesions. Functional MRI was acquired using a 1.5 MR scanner. Peritumoral inflammatory tissue was assessed by drawing regions of interest on the tumor contours. DCE-MRI, IVIM and DKI parameters were extracted. Nonparametric tests and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were calculated.

Results:

There were statistically significant differences in median values among the three groups observed by Kruskal–Wallis test for the DKI mean diffusivity (MD), IVIM perfusion fraction (fp) and IVIM tissue pure diffusivity (Dt). MD had the best results to discriminate normal pancreas plus peritumoral inflammatory tissue versus pancreatic tumor, to separate normal pancreatic parenchyma versus pancreatic tumor and to differentiate peritumoral inflammatory tissue versus pancreatic tumor, respectively, with an accuracy of 84%, 78%, 83% and area under ROC curve (AUC) of 0.85, 0.82, 0.89. The findings were statistically significant compared with those of other parameters (p value < 0.05 using McNemar’s test). Instead, to discriminate normal pancreas versus peritumoral inflammatory tissue or pancreatic tumor and to differentiate normal pancreatic parenchyma versus peritumoral inflammatory tissue, there were no statistically significant differences between parameters’ accuracy (p > 0.05 at McNemar’s test).

Conclusions:

Diffusion parameters, mainly MD by DKI, could be helpful for the differentiation of normal pancreatic parenchyma, perilesional inflammation, and pancreatic tumor.

Keywords: diffusion, magnetic resonance imaging, pancreatic cancer, perfusion

Introduction

Diagnosis of pancreatic cancer remains challenging, due to overlapping imaging features with benign lesions notwithstanding great advances with multidetector computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).1,2 However, a proper detection and characterization of pancreatic lesions is mandatory because the prognosis is linked to tumor type and grade,3 and correct staging on accurate imaging; in fact, a pancreatic cancer that infiltrates lymphatic vessels can be manifest as infiltration of peripancreatic tissue. This local invasion can determine underestimation of real extension and grade of the disease.4 Thus, an imaging modality that provides higher tumor conspicuity would be desirable to improve staging and clinical outcomes.5,6 Quantitative analysis of perfusion parameters by using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) has been considered. Moreover, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is another magnetic resonance modality that is able to objectively and quantitatively assess perfusion and diffusion to aid detection of malignancies.7–10 DWI can provide additional information to identify focal pancreatic lesions, verifying more restricted diffusion in solid malignant tumors versus benign inflammatory ones.11–14 However, the diffusion-weighted signal and the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values can be influenced both by molecular diffusion and by microcirculation, or blood perfusion, and, therefore, ADC values may be polluted from perfusion effects, reducing the ADC reliability to characterize pancreatic lesions.15,16 Microcirculation or perfusion effects can be separated by diffusion water motion biexponential curve fit analysis with the intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) model.15–19

Previous studies with the IVIM approach have demonstrated that the reduced ADC in pancreatic adenocarcinomas (PDACs) possibly relates to a difference in perfusion fraction (fp), which is reduced in PDACs;18 therefore, fp is the best factor among DWI-derived parameters to differentiate pancreatitis from PDACs.19 Until now, however, there have been only a few studies in which the value of IVIM was explored to differentiate malignant pancreatic tumors from benign lesions. Moreover, the conventional DWI model is based on the hypothesis that water diffusion motion follows a Gaussian behavior.16,17 However, due to the presence of microstructures, water diffusion motion exhibits non-Gaussian behavior,20 and Jensen and coworkers suggested a non-Gaussian diffusion model, known as diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI).20 This model showed better performance than conventional ADC in tumor detection and staging.21–27

The purpose of this study was to assess MRI capability in the differentiation of pancreatic tumors, peritumoral inflammatory tissue, and normal pancreatic parenchyma by means of DCE-MRI-, DKI-, and IVIM-derived parameters.

Materials and methods

Study population

The ethical local review board of the National Cancer Institute of Naples Pascale Foundation approved this retrospective study (deliberation no. 482/2014) and written informed consent for each patient was obtained. We searched the surgical database at our institution from January 2014 to October 2017 and selected 42 patients with pancreatic cancer who underwent surgical resection. The inclusion criteria for the study population were as follows: (a) patients who had pathologically proven pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas; (b) patients who had undergone both DCE-MRI and DWI; (c) patients who had less than a 1-month interval between imaging and pathologic diagnosis; and (d) availability of diagnostic quality pictures of the cut sections of the resected specimens in patients who underwent surgical resection for matching of imaging and pathology findings. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) conflict between the imaging-based diagnosis and the pathologically confirmed diagnosis; (b) limitation of pathologic imaging correlation owing to poor image quality; and (c) no available DCE-MRI and DWI.

Thirty-seven patients with pancreatic adenocarcinomas during the study period were selected. Among them, 13 patients were excluded for the following reasons: (a) 8 patients had no available DCE-MRI and DWI study; and (b) 5 patients had more than a 1-month interval between imaging and pathologic diagnosis. Thus, the study group consists of 24 patients [14 men and 10 women, median age 71 years (age range, 53–85 years)]. Characteristics of the study group are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients (24 pancreatic cancer and 24 control group patients).

| Description | Numbers (%)/range |

|---|---|

| Pancreatic cancer patients (n = 24) | |

| Sex | Men 14 (58.3%) |

| Women 10 (41.7%) | |

| Age | 71 years (range, 53–85 years) |

| Histotype | Adenocarcinoma 100% (24/24) |

| Location | |

| Head | 14 (58.3%) |

| Body/tail | 10 (41.6%) |

| Largest diameter | 28.0 mm; range 12–52 mm |

| Control group patients (n = 24) | |

| Sex | Men 13 (54.2 %) |

| Women 11 (45.8%) | |

| Age | 56 years; range, 33–78 years |

| Previous neoplastic history | |

| Yes | 9 (37.5%); colorectal cancer (100%) |

| No | 15 (62.5%); hepatic benign lesions |

| Previous Chemotherapy | No one |

| Previous history of pancreatitis | No one |

We also searched the radiological database of our institute during the study period and selected a control group of patients without pancreatic lesions, confirmed by imaging and without history of increased amylases and carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19–9), to reduce spectrum bias. A total of 24 patients [13 men, 11 women; median age, 56 years (age range, 33–78 years)] that underwent DCE-MRI and DWI upper abdomen studies were enrolled. Characteristics of the study control group are summarized in Table 1.

Lesion confirmation: reference standard

A pathologist specialized in pancreatic diseases performed histopathologic analysis of resected specimens. Twenty-four patients with pathologically proven pancreatic adenocarcinomas who underwent surgical resection (mean tumor size, 28.0 mm; range 12–52 mm) constituted the study group. Lesion confirmation was based on the pathologic diagnosis of surgically resected pancreatic specimens. Ductal adenocarcinoma composed of epithelial neoplastic cells embedded in a fibrous stroma. Neoplastic cells expressed a specific pattern of immunohistochemically detectable markers: cytokeratins (cytokeratin 7, 8, 13, 18, and 19) and CA19–9.

MR protocol

The MR protocol consisted of morphological and functional imaging, including DCE-MRI and DWI sequences. Imaging was performed with a 1.5 T scanner (MAGNETOM Symphony, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a phased-array body coil. Patients were placed in a supine, head-first position. A free-breathing axial single-shot echo-planar DWI pulse sequence was performed with tridirectional diffusion gradients with b values of 0, 50, 100, 150, 400, 800, and 1000 s/mm2. With regards the DCE-MR imaging, we obtained 1 sequence before and 120 sequences (without any delay) after intravenous injection of 2 ml/kg of a positive, gadolinium-based paramagnetic contrast medium (Gadobutrol Gd-DTPA, Bayer Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany). The contrast medium was injected using a Spectris Solaris® EP MR pump (MEDRAD Inc., Indianola, PA), with a flow rate of 2 ml/s, followed by a 10 ml saline flush at the same rate. DCE-MRI T1-weighted time-resolved angiography with stochastic trajectories (TWIST) three-dimensional (3D) axial images were acquired to improve temporal resolution (3 s). MRI sequence parameters were reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

MRI sequence parameters.

| Sequence | Orientation | TR/TE/FA (ms/ms/deg.) | FOV (mm2) | Acquisition matrix | Slice thickness/gap (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HASTE T2-w | Axial | 1500/90/180 | 380 × 380 | 320 × 320 | 5/0 |

| FLASH T1-w In-out phase | Axial | 160/4.87/70 | 285 × 380 | 192 × 256 | 5/0 |

| FLASH T1-w out phase | Axial | 178/2.3/80 | 325 × 400 | 416 × 412 | 3/0 |

| DWI | Axial | 7500/91/90 | 340 × 340 | 192 × 192 | 3/0 |

| VIBE T1-w | Axial | 4.89/2.38/10 | 325 × 400 | 320 × 260 | 3/0 |

| TWIST T1-w Pre- and postcontrast-agent injection | Axial | 3.01/1.09/25 | 300 × 300 | 256 × 256 | 2/0 |

AT, acquisition time; deg., degree; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; FA, flip angle; FLASH, fast low-angle shot; FOV, field of view; HASTE, half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo; TE, echo time; TR, repetition time; VIBE, volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination; -w, weighted.

MR image analysis

Two expert radiologists, in consensus, simultaneously avoiding encircling any distortion artifacts, manually drew regions of interest (ROIs). One radiologist with over 20 years of clinical experience, and one with 8 years of clinical experience in interpreting abdominal MR imaging studies drew ROIs on DCE images with virtual ‘fat suppression’ obtained, subtracting the precontrast from the postcontrast image and then verifying these on the DWI image at the highest b value. For patients with pancreatic cancer, the tumor was contoured slice by slice to obtain the neoplastic volume of interest and we also selected four regions of interest in the contours of the tumor, according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines version 3.2017, for pathologic analysis of margins,28 to obtain the median value of peritumoral inflammatory tissue. For the pancreatic head cancer we drew ROIs inside the superior mesenteric margin (SMA margin) corresponding to the soft tissue directly adjacent to the proximal 3–4 cm of the superior mesenteric artery, and posterior margin corresponding to the tissue between the posterior caudad aspect of the pancreatic head that merges with the SMA margin. For distal lesions, we drew ROIs inside the proximal pancreatic margin corresponding to the pancreatic body along the plane of the section, and the anterior and posterior peripancreatic margin corresponding to the tissue between the tumor and adjacent soft tissue.1,28 For patients without pancreatic cancer, we selected four ROIs in the pancreas parenchyma (head, neck, body, and tail) to obtain the median value of pancreatic parenchyma tissue. Features have been computed pixel by pixel to obtain the median value of ROIs.

DCE-MRI features

For each voxel, eight time-intensity-curve shape descriptors were computed using an approach previously reported in:29 maximum signal difference (MSD), the time to peak (TTP), the wash-in slope (WIS), the wash-out slope (WOS), the wash-in intercept (WII), the wash-out intercept (WOI), the WOS/WIS ratio, and the WOI/WII ratio.

DCE-MRI parameters were obtained using in-house prototype software developed in MATLAB R2007a (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, US).

DWI features

Per each voxel, six features were extracted from DWI data using the monoexponential model, the DKI model and the IVIM model;7,8,15,16,30–38

DWI signal decay is most commonly analyzed using the monoexponential model:15,16

| (1) |

where Sb is the MRI signal intensity with diffusion weighting b, S0 is the nondiffusion-weighted signal intensity.

For a voxel with a large vascular fraction, the MRI data decay can deviate from a monoexponential form, in particular showing a fast decay in the range of low b values generated by the IVIM effect.15,16,32 Thus, in addition to the monoexponential model, a biexponential model was used to estimate the IVIM-related parameters of pseudodiffusivity (Dp, also indicated by D*), fp and tissue pure diffusivity (Dt) using the VARiable PROjection approach:38

| (2) |

Moreover, DKI was included in the analysis to obtain the final fitted images [MD and mean of diffusional kurtosis (MK)].

Multi-b diffusion-weighted images were obtained fitting voxel by voxel, using the diffusion kurtosis signal decay Equation (3) by a two-variable linear least-squares algorithm as used in previous study:20

| (3) |

In this equation, D is a corrected Dt; and K is the excess diffusion kurtosis coefficient. K describes the degree that molecular motion deviates from the perfect Gaussian distribution.

The difference between D and ADC is that D is a corrected form of ADC for use in non-Gaussian circumstances.

The parameters of conventional DWI (ADC), IVIM [fp, Dt, pseudodiffusivity (Dp)] and DKI (MK and MD) were obtained from the multi-b DWI data with all measured b values using the prototype postprocessing software Body Diffusion Toolbox (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as the median ± standard deviation (SD). All parameters subdivided into the three groups (normal pancreatic parenchyma, peritumoral inflammatory tissue, pancreatic tumor) were compared with each other using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test. The Kruskal–Wallis test was also performed to assess differences statistically significant of the extracted parameters between head and body/tail region of the pancreas.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were calculated to characterize each parameter value for evaluating the capability to differentiate pancreatic tumors versus peritumoral inflammatory tissue or pancreatic parenchyma tissue. The optimal cut-off values (obtained according to the maximal Youden index = sensitivity + specificity − 1), the corresponding sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy were calculated. McNemar’s test was used to verify statistically significant difference accuracy among parameters. Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Statistics Toolbox of MATLAB R2007a (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, US) was used to perform statistical analysis.

Results

Table 3 reports the median value and SD value for pancreatic tumor, peritumoral inflammatory tissue and pancreatic parenchyma tissue.

Table 3.

Median and standard deviation (SD) value for each extracted MR parameter in three groups: normal pancreatic parenchyma, peritumoral inflammatory tissue, pancreatic tumor.

| MSD (AU) | TTP (AU) | WOS (AU) | WOI (AU) | WIS (AU) | WII (AU) | WOS_WIS (AU) | WOI/WII (AU) | ADC (× 10−6 mm2/s) | MK (× 10−3) | MD (× 10−6 mm2/s) | Fp (× 10−1%) | Dt (× 10−6 mm2/s) | Dp (× 10−5 mm2/s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal pancreatic parenchyma tissue | Median | 39.20 | 36.25 | −0.42 | 60.27 | 3.75 | 35.95 | −0.03 | 1.04 | 1397.50 | 1193.85 | 2843.20 | 225.00 | 1263.00 | 135.60 |

| SD | 31.99 | 19.93 | 17.81 | 48.96 | 17.84 | 58.94 | 13.85 | 4.06 | 309.75 | 1393.73 | 728.35 | 90.42 | 357.21 | 57.30 | |

| Peritumoral inflammatory tissue | Median | 38.07 | 30.00 | −1.65 | 61.68 | 13.14 | 35.72 | −0.01 | −0.56 | 1429.90 | 1237.40 | 3211.10 | 277.10 | 1119.50 | 172.30 |

| SD | 30.65 | 20.63 | 19.87 | 48.86 | 20.17 | 66.95 | 13.57 | 5.32 | 521.65 | 409.80 | 1966.28 | 154.64 | 525.72 | 87.07 | |

| Pancreatic cancer | Median | 42.70 | 25.00 | −1.10 | 38.43 | 20.91 | 15.47 | −0.01 | −0.94 | 1196.50 | 1399.30 | 1849.50 | 144.20 | 1018.60 | 112.80 |

| SD | 27.60 | 18.58 | 52.06 | 84.78 | 25.49 | 97.71 | 3.31 | 10.40 | 281.18 | 384.69 | 603.95 | 81.53 | 328.62 | 56.62 | |

| p value at Kruskal–Wallis test | 0.71 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.10 | 0.57 | 0.15 | 0.82 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0.02 |

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; AU, Arbitrary unit; Dp, pseudodiffusivity; Dt, tissue pure diffusivity; fp, perfusion fraction; MD, mean diffusivity; MK, mean of diffusional kurtosis; MSD, maximum signal difference; SD, standard deviation; TTP, time to peak; WII, wash-in intercept; WIS, wash-in slope; WOS, wash-out slope; WOI, wash-out intercept.

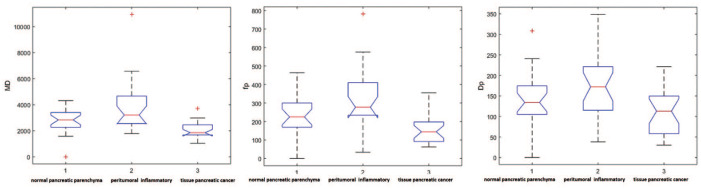

There were statistically significant differences in median values among the three groups observedusing the Kruskal–Wallis test for MD, fp, and Dp, while there were no significant differences among these groups for dynamic parameters (see also Figure 1). WIS showed no statically significant difference for median values in three groups (p value = 0.06): 3.75 ± 17.84 in pancreatic parenchyma tissue; 13.14 ± 20.17 in peritumoral inflammatory tissue; and 20.91 ± 25.49 in pancreatic tumor. MD had a median value of 2843.20 ± 728.35 × 10−3 mm2/s in normal pancreatic parenchyma while had a median value of 3211.10 ± 796.28 × 10−3 mm2/s for peritumoral inflammatory tissue and of 1849.50 ± 603.95 × 103 mm2/s in pancreatic tumor. fp had a median value of 22.50 ± 9.04% in normal pancreatic parenchyma, while having a median value of 27.71 ± 15.46% for peritumoral inflammatory tissue, and 14.42 ± 8.15% in pancreatic tumor. Dp had a median value of 135.60 ± 57.30 × 10−5 mm2/s in normal pancreatic parenchyma while had a median value of 172.30 ± 87.07 × 10−5 mm2/s for peritumoral inflammatory tissue and of 112.80 ± 56.6 × 10−5 mm2/s in pancreatic tumor.

Figure 1.

Boxplot of WIS, MD, fp and Dp parameters.

Dp, pseudodiffusivity; fp, perfusion fraction; MD, mean diffusivity; WIS, wash-in slope.

No statistically significant differences were observed in median values of extracted parameters between head and body/tail region of the pancreas using the Kruskal–Wallis test (p value > 0.05).

Table 4 reports the diagnostic accuracy of MRI-extracted parameters in discriminating normal pancreatic parenchyma plus peritumoral inflammatory tissue versus pancreatic tumor. The bolded parameters having high accuracy and area under ROC curve (AUC) are WOI, WII, ADC, MD, fp, and Dp, showing an accuracy ⩾ 65% and AUC > 0.6. MD had the best results with an accuracy of 84% (p value < 0.05 using McNemar’s test) and AUC = 0.85.

Table 4.

Diagnostic accuracy of MRI-extracted parameters.

| AUC | SEN | SPEC | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | Cut off | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discriminating normal pancreatic parenchyma plus peritumoral inflammatory tissue versus pancreatic tumor | |||||||

| MSD | 0.45 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 95.51 |

| TTP | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.72 | 0.41 | 0.59 | 25.01 |

| WOS | 0.51 | 0.78 | 0.35 | 0.70 | 0.44 | 0.63 | −5.88 |

| WOI | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.50 | 0.66 | 48.83 |

| WIS | 0.35 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.68 | −44.80 |

| WII | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.50 | 0.66 | 33.47 |

| WOS/WIS | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0.36 | 0.47 | 0.08 |

| WOI/WII | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.73 | 0.43 | 0.60 | −0.92 |

| ADC | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.49 | 0.65 | 1330.97 |

| MK | 0.40 | 0.76 | 0.30 | 0.68 | 0.39 | 0.60 | 996.76 |

| MD | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.70 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.84 | 2168.31 |

| fp | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.88 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 199.85 |

| Dt | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.42 | 0.56 | 1253.63 |

| Dp | 0.70 | 0.93 | 0.39 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 68.92 |

| Discriminating normal pancreatic parenchyma versus peritumoral inflammatory tissue or pancreatic tumor | |||||||

| MSD | 0.50 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 104.04 |

| TTP | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.44 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 38.01 |

| WOS | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.74 | 0.54 | −1.57 |

| WOI | 0.60 | 0.86 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.85 | 0.53 | 33.56 |

| WIS | 0.43 | 0.82 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.76 | 0.46 | −5.19 |

| WII | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.76 | 0.50 | 0.76 | 0.68 | 36.70 |

| WOS/WIS | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.80 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.28 |

| WOI/WII | 0.63 | 0.73 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.82 | 0.63 | 0.17 |

| ADC | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.40 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 1331.67 |

| MK | 0.47 | 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 996.76 |

| MD | 0.58 | 0.86 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.86 | 0.56 | 2214.80 |

| fp | 0.55 | 0.82 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.82 | 0.53 | 167.83 |

| Dt | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 1147.04 |

| Dp | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.26 | 0.39 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 68.92 |

Diagnostic accuracy of MRI-extracted parameters in discriminating normal pancreatic parenchyma plus peritumoral inflammatory tissue versus pancreatic tumor, and in discrimination of normal pancreatic parenchyma versus peritumoral inflammatory tissue or pancreatic tumor. Parameters having high accuracy and AUC are in bold type.

ACC, accuracy; AUC, area under curve; Dp, pseudodiffusivity; Dt, tissue pure diffusivity; fp, perfusion fraction; MD, mean diffusivity; MK, mean of diffusional kurtosis; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MSD, maximum signal difference; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; SEN, sensitivity; SPEC, specificity; TTP, time to peak; WII, wash-in intercept; WIS, wash-in slope; WOS, wash-out slope; WOI, wash-out intercept.

Table 4 also reports the diagnostic accuracy of MR-extracted parameters in discriminating normal pancreatic parenchyma versus peritumoral inflammatory tissue or pancreatic tumor. The parameters having high accuracy and AUC are again emphasized in bold. WII and WOI/WII showed an accuracy ⩾ 63% and AUC ⩾ 0.6. There were no statistically significant differences (p value > 0.05 using McNemar’s test) between parameter accuracy, however DCE-MRI WII had the highest accuracy (68%) and AUC (0.60).

Table 5 reports the diagnostic accuracy of MR-extracted parameters in discriminating normal pancreatic parenchyma versus pancreatic tumor and those with high accuracy and AUC are bolded. WII, MD, fp, and Dp showed an accuracy > 70% and AUC > 0.6. MD had the best accuracy of 78% (p value < 0.05 using McNemar’s test) and AUC of 0.82.

Table 5.

Diagnostic accuracy of MRI-extracted parameters.

| To discriminate normal pancreatic parenchyma versus pancreatic tumor |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | SEN | SPEC | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | Cut off | |

| MSD | 0.47 | 0.14 | 0.96 | 0.75 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 92.21 |

| TTP | 0.54 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 31.02 |

| WOS | 0.51 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.56 | −1.54 |

| WOI | 0.68 | 0.86 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.79 | 0.67 | 30.87 |

| WIS | 0.36 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.51 | −44.80 |

| WII | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 33.49 |

| WOS/WIS | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.17 |

| WOI/WII | 0.59 | 0.77 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.64 | −0.92 |

| ADC | 0.61 | 0.55 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 1330.99 |

| MK | 0.42 | 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 997.00 |

| MD | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 2168.48 |

| fp | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 167.81 |

| Dt | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 1197.58 |

| Dp | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 0.69 | 68.91 |

| Discriminating normal pancreatic parenchyma versus peritumoral inflammatory tissue | |||||||

| MSD | 0.53 | 0.73 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.58 | 30.24 |

| TTP | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 38.01 |

| WOS | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.58 | −1.63 |

| WOI | 0.53 | 0.27 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.60 | 105.40 |

| WIS | 0.50 | 0.82 | 0.35 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 0.58 | −5.20 |

| WII | 0.52 | 0.73 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.58 | 8.50 |

| WOS/WIS | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.28 |

| WOI/WII | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.18 |

| ADC | 0.43 | 0.73 | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 1139.20 |

| MK | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 1.00 | 0.56 | 600.80 |

| MD | 0.35 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.49 | – | 0.49 | 1479.50 |

| fp | 0.30 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.51 | 33.76 |

| Dt | 0.54 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 1147.04 |

| Dp | 0.39 | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 1.00 | 0.56 | 67.22 |

| Discriminating peritumoral inflammatory tissue versus pancreatic tumor | |||||||

| MSD | 0.43 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.52 | 0.54 | 95.53 |

| TTP | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 25.00 |

| WOS | 0.51 | 0.83 | 0.35 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.59 | −5.88 |

| WOI | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 48.84 |

| WIS | 0.34 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.51 | 1.00 | 0.52 | −44.80 |

| WII | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 33.47 |

| WOS/WIS | 0.53 | 0.91 | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.71 | 0.57 | −1.74 |

| WOI/WII | 0.47 | 1.00 | 0.09 | 0.52 | 1.00 | 0.54 | −30.07 |

| ADC | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 1330.97 |

| MK | 0.38 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | − | 0.50 | 367.20 |

| MD | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.94 | 0.83 | 2168.31 |

| fp | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 199.85 |

| Dt | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.78 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 1253.63 |

| Dp | 0.74 | 0.61 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 154.83 |

Diagnostic accuracy of MRI-extracted parameters in discriminating normal pancreatic parenchyma versus pancreatic tumor, of normal pancreatic parenchyma versus peritumoral inflammatory tissue, and of peritumoral inflammatory tissue versus pancreatic tumor. Parameters having high accuracy and AUC are in bold type.

ACC, accuracy; AUC, area under curve; Dp, pseudodiffusivity; Dt, tissue pure diffusivity; fp, perfusion fraction; MD, mean diffusivity; MK, mean of diffusional kurtosis; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MSD, maximum signal difference; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; SEN, sensitivity; SPEC, specificity; TTP, time to peak; WII, wash-in intercept; WIS, wash-in slope; WOS, wash-out slope; WOI, wash-out intercept.

Moreover, Table 5 reports the diagnostic accuracy of MR-extracted parameters in discrimination of normal pancreatic parenchyma versus peritumoral inflammatory tissue. There were no statistically significant differences between parameter accuracy (p value > 0.05 using McNemar’s test); however, DCE-MRI WOI/WII had the best accuracy (67%) and AUC (0.67).

Finally, Table 5 reports the diagnostic accuracy of MR-extracted parameters in discriminating peritumoral inflammatory tissue versus pancreatic tumor. WII, MD, fp, and Dp showed an accuracy ⩾ 72% and AUC > 0.6. MD had the best accuracy at 83% (p value < 0.05 at McNemar test) and AUC of 0.89.

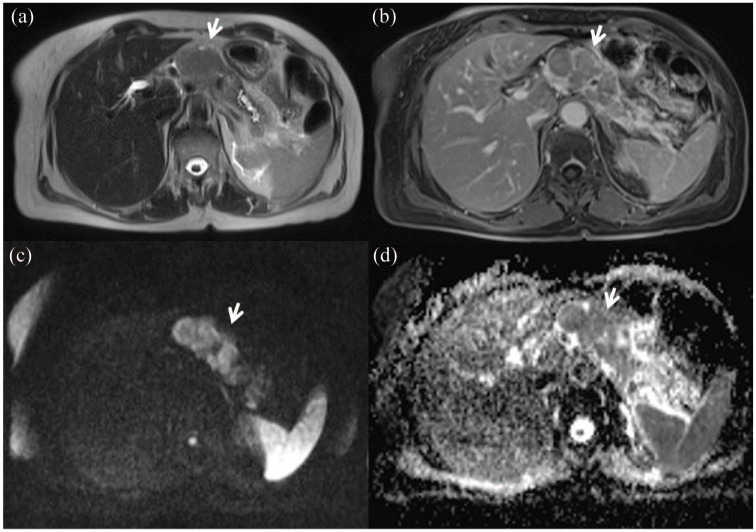

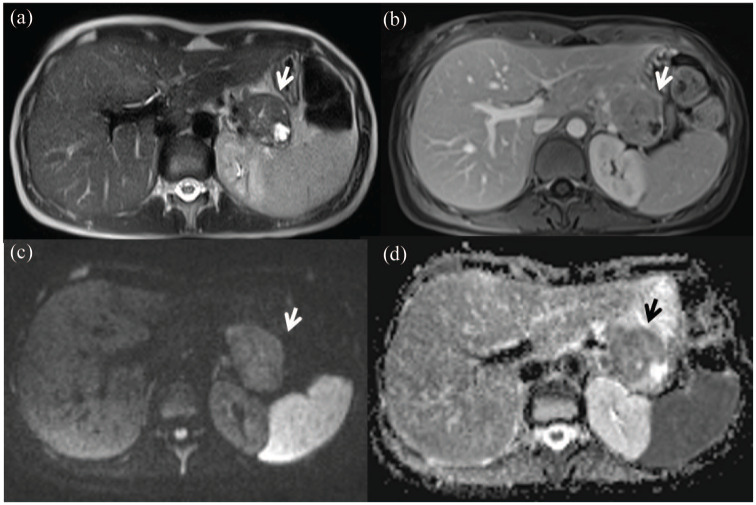

Figures 2 and 3 show representative cases of pancreatic tumor with hyperintense signal on T2-weighted sequence, isohypointense signal during the portal phase of the contrast study, restricted diffusion on DWI at b = 1000 s/mm2 and hypointense signal on the ADC map.

Figure 2.

Female, 43 years, body pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

The lesion shows hyperintense signal in T2-w sequence: (a) HASTE T2-w in axial plane with isohypointense signal during portal phase of contrast study; (b) VIBE FS in axial plane. In DWI (c) b = 1000 s/mm2; the lesion shows restricted diffusion with hypointense signal on the ADC map (d).

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; HASTE, half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo; T2-w, T2 weighted; VIBE FS, volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination fat saturated.

Figure 3.

Female, 45 years, tail pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

The lesion shows hyperintense signal in T2-w sequence (a) HASTE T2-w in axial plane with isohypointense signal during portal phase of contrast study; (b) VIBE FS in axial plane. In DWI (c) b = 1000 s/mm2; the lesion shows restricted diffusion with hypointense signal on the ADC map (d).

ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; HASTE, half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo; T2-w, T2 weighted; VIBE FS, volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination fat saturated.

Discussion

DCE-MRI accuracy in the evaluation of pancreatic cancer remains unclear. In pancreatic adenocarcinoma, poorly represented microvascular components could be clarified by vessel functional impairment often observed in tumors, and by the presence of a prominent stromal matrix that embeds vessels. In addition, activated pancreatic stellate cells yield increasing fibrous stroma in tumor central areas, compressing blood vessels, leading to changes in vascularity and perfusion.39,40 Several studies evaluated the feasibility of DCE-MRI for the characterization of solid pancreatic diseases.39,40–9

Kim and colleagues39 evaluated 24 patients with pancreatic cancers; 8 with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs), 3 with chronic pancreatitis, and 10 with a normal pancreas. They showed that Ktrans [transfer constant by extravascular extracellular space (EES) to plasma], kep (transfer constant by plasma versus EES), and iAUC (initial AUC) values in patients with pancreatic cancer were significantly lower than in patients with a normal pancreas. In addition, kep values of PNETs and normal pancreas and Ktrans, kep, and iAUC values of pancreatic cancers and PNETs differed significantly. Bali and colleagues40 evaluated 28 patients with surgically resectable pancreatic lesions. They showed that Ktrans values were significantly lower in primary malignant tumors compared with benign lesions and nontumoral pancreatic tissue; plasma volume fraction was significantly higher in primary malignant tumors compared with nontumoral pancreatic tissue. Sensitivity and specificity for fibrosis detection were 65% and 83%, and 76% and 83% for the Ktrans one-compartment two-compartment models, respectively.

We evaluated semiquantitative descriptors of the contrast-agent time course such as MSD, TTP, WIS, WOS, WII, WOI, the WOS/WIS ratio, and the WOI/WII ratio. Our findings showed that there were no differences among three groups for dynamic parameters except a statistically nonsignificant difference for WIS comparable with Ktrans.30

Diffusion parameters can be assessed by DWI.38 The IVIM approach allows separating blood volume fraction (perfusion) by diffusion and microstructural information.35,36 Several studies reported that IVIM is a promising tool in pancreatic cancer.20,41,42 Kang and colleagues41 evaluated the diagnostic performance of ADC- and IVIM-derived parameters to distinguish pancreatic tumors, chronic pancreatitis, and normal pancreas and to characterize intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs). They reported that incoherent microcirculation (Dfast) and fp values of PDACs were significantly lower than those of normal pancreas, chronic pancreatitis, and NETs. In differentiating PDACs from NETs, fp and Dfast showed a significant difference. Malignant IPMNs had significantly lower ADC and slow component of diffusion values, while benign IPMNs had significantly higher Dfast and fp values. In ROC analysis, fp showed the highest ROC AUC in distinguishing malignant from benign IPMNs.41 They concluded that perfusion might be a more important factor than diffusion in discriminating PDAC from normal pancreas, chronic prostatitis and NETs. In addition, fp showed the highest AUC by ROC analysis in differentiating malignant from benign IPMNs among ADC- and IVIM-derived parameters.41 Klau and colleagues42 investigated the correlation between IVIM-derived parameters and histologically determined microvascularity in PDACs and PNETs. They showed that blood volume fraction fp was significantly lower in PDACs compared with PNETs, and that the Dt was significantly higher in PDAC.42

In our study, we evaluated ADC and the IVIM-related parameters (Dp, fp and Dt), so the kurtosis coefficient that is linked to the deviation of tissue diffusion from a Gaussian model, and the Dt with the correction of non-Gaussian bias by DKI. Recently, DKI was used to assess therapy response in different kinds of tumors.43–45 According to our results, there was a statistically significant difference in median values among the three groups observed by Kruskal–Wallis test for MD, fp and Dp. In our study, the perfusion-related factors of PDAC, fp and Dp, and MD of DKI, differed from those seen in patients with normal pancreatic parenchyma and in peritumoral tissue, and showed better diagnostic performance than did ADC. Although the differential diagnosis of PDAC and normal pancreatic parenchyma is usually considered straightforward, overlap in imaging features can make this differentiation difficult. Therefore, the significantly different perfusion-related factors of PDAC and normal pancreatic parenchyma might be helpful for determining the most accurate diagnosis. Increased fp and MD in peritumoral inflammation seem to suggest that DWI-derived parameters fit in the anticipated physiologic phenomena. Our results support the hypothesis that the kurtosis effect could have a better performance in differentiating pancreatic tumors, peritumoral inflammatory tissue, and normal pancreatic parenchyma, although our data were acquired with a maximum b value of 1000 s/mm2. In general, in brain applications, very high b values are recommended for the assessment of a non-Gaussian kurtosis effect;1,20 while in abdominal applications, for the lower signal-to-noise ratio and lower T2-relaxation times, very high b values are not usually applied. Recently, various authors have shown that kurtosis effects could be detectable in abdominal and whole-body applications also using, as maximum, b values of 800 s/mm2 or less at 3T.1,7,24,27 We applied multiple b values with a maximum of 1000 s/mm2 that, coupled with the use of a parallel imaging factor, resulted in images with acceptable signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) at 1.5T.

Some limits in our study must be highlighted. First, the retrospective nature of this study. A larger number of patients will be needed to confirm our results. We believe further studies with a larger study population are warranted for its validation. Second, we did not assess the interobserver variability regarding the drawing of ROIs. However, we used median values both for DCE-MRI and for DWI-derived parameters. Third, we used only 4 b values < 200 s/mm2 to estimate IVIM diffusion parameters, which could be seen as a weakness; however, we used a robust algorithm, the VARiable PROjection approach, superior to the conventional Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm for curve fitting and diffusion parameters estimation of intravoxel incoherent motion method.

Conclusion

IVIM and DKI-derived parameters could be helpful in the discrimination of normal pancreatic parenchyma tissue, perilesional inflammation, and pancreatic tumor. Overall, MD of DKI is the parameter that allows the best classification among normal pancreatic parenchyma tissue, perilesional inflammation, and pancreatic tumor.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest statement: Robert Grimm is an employee of Siemens Healthcare.

ORCID iD: Roberta Fusco  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0469-9969

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0469-9969

Contributor Information

Vincenza Granata, Radiology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori – IRCCS – Fondazione G. Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Roberta Fusco, Department of Radiology, Istituto Nazionale Tumori Fondazione G. Pascale, via Mariano Semmola, Naples 80131, Italy.

Mario Sansone, Department of Electrical Engineering and Information Technologies (DIETI), University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy.

Roberto Grassi, Radiology Unit, Università della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Naples, Italy.

Francesca Maio, Radiology Unit, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy.

Raffaele Palaia, Hepatobiliary Surgical Oncology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori – IRCCS – Fondazione G. Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Fabiana Tatangelo, Diagnostic Pathology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori – IRCCS – Fondazione G. Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Gerardo Botti, Diagnostic Pathology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori – IRCCS – Fondazione G. Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Robert Grimm, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Bayern, Germany.

Steven Curley, Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA.

Antonio Avallone, Abdominal Oncology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori – IRCCS – Fondazione G. Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Francesco Izzo, Hepatobiliary Surgical Oncology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori – IRCCS – Fondazione G. Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

Antonella Petrillo, Radiology Unit, ‘Istituto Nazionale Tumori – IRCCS – Fondazione G. Pascale’, Naples, Italy.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67: 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Granata V, Fusco R, Catalano O, et al. Multidetector computer tomography in the pancreatic adenocarcinoma assessment: an update. Infect Agent Cancer 2016; 11: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brennan DD, Zamboni GA, Raptopoulos VD, et al. Comprehensive preoperative assessment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma with 64-section volumetric CT. Radiographics 2007; 27: 1653–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fukukura Y, Shindo T, Hakamada H, et al. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the pancreas: optimizing b-value for visualization of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Eur Radiol 2016; 26: 3419–3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baek JH, Lee JM, Kim SH, et al. Small (<3cm) solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas at multiphasic multidetector CT. Radiology 2010; 257: 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Casneuf VF, Delrue L, Van Damme N, et al. Noninvasive monitoring of therapy-induced microvascular changes in a pancreatic cancer model using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with P846, a new low-diffusible gadolinium-based contrast agent. Radiat Res 2011; 175: 10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kartalis N, Lindholm TL, Aspelin P, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of pancreas tumors. Eur Radiol 2009; 19: 1981–1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Inan N, Arslan A, Akansel G, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging in the differential diagnosis of cystic lesions of the pancreas. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 191: 1115–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Choi SY, Kim SH, Kang TW, et al. Differentiating mass-forming autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma on the basis of contrast-enhanced MRI and DWI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2016; 206: 291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang Y, Miller FH, Chen ZE, et al. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of solid and cystic lesions of the pancreas. RadioGraphics 2011; 31: E47–E64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee SS, Byun JH, Park BJ, et al. Quantitative analysis of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the pancreas: usefulness in characterizing solid pancreatic masses. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008; 28: 928–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ma C, Guo X, Liu L, et al. Effect of region of interest size on ADC measurements in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Imaging 2017; 17: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muraoka N, Uematsu H, Kimura H, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient in pancreatic cancer: characterization and histopathological correlations. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008; 27: 1302–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ma C, Liu L, Li J, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) measurements in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a preliminary study of the effect of region of interest on ADC values and interobserver variability. J Magn Reson Imaging 2016; 43: 407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, et al. Separation of diffusion and perfusion in intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging. Radiology 1988; 168: 497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, et al. MR imaging of intravoxel incoherent motions: application to diffusion and perfusion in neurologic disorders. Radiology 1986; 161: 401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koh DM, Collins DJ, Orton MR. Intravoxel incoherent motion in body diffusion-weighted MRI: reality and challenges. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011; 196: 1351–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lemke A, Laun FB, Klauss M, et al. Differentiation of pancreas carcinoma from healthy pancreatic tissue using multiple b-values: comparison of apparent diffusion coefficient and intravoxel incoherent motion derived parameters. Invest Radiol 2009; 44: 769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Klauss M, Lemke A, Grünberg K, et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion MRI for the differentiation between mass forming chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Invest Radiol 2011; 46: 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jensen JH, Helpern JA. MRI quantification of non-Gaussian water diffusion by kurtosis analysis. NMR Biomed 2010; 23: 698–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sun K, Chen X, Chai W, et al. Breast cancer: diffusion kurtosis MR imaging-diagnostic accuracy and correlation with clinical-pathologic factors. Radiology 2015; 277: 46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Suo S, Chen X, Wu L, et al. Non-Gaussian water diffusion kurtosis imaging of prostate cancer. Magn Reson Imaging 2014; 32: 421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nogueira L, Brandão S, Matos E, et al. Application of the diffusion kurtosis model for the study of breast lesions. Eur Radiol 2014; 24: 1197–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosenkrantz AB, Sigmund EE, Winnick A, et al. Assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma using apparent diffusion coefficient and diffusion kurtosis indices: preliminary experience in fresh liver explants. Magn Reson Imaging 2012; 30: 1534–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van Cauter S, Veraart J, Sijbers J, et al. Gliomas: diffusion kurtosis MR imaging in grading. Radiology 2012; 263: 492–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raab P, Hattingen E, Franz K, et al. Cerebral gliomas: diffusional kurtosis imaging analysis of microstructural differences. Radiology 2010; 254: 876–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rosenkrantz AB, Sigmund EE, Johnson G, et al. Prostate cancer: feasibility and preliminary experience of a diffusional kurtosis model for detection and assessment of aggressiveness of peripheral zone cancer. Radiology 2012; 264: 126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology on Pancreatic Cancer. Version 3., http://www.nccn.org. (2017) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29. Fusco R, Petrillo A, Petrillo M, et al. Use of tracer kinetic models for selection of semi-quantitative features for DCE-MRI data classification. Appl Magn Reson 2013; 44: 1311–1324. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Luciani A, Vignaud A, Cavet M, et al. Liver cirrhosis: intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging—pilot study. Radiology 2008; 249: 891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wirestam R, Borg M, Brockstedt S, et al. Perfusion-related parameters in intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging compared with CBV and CBF measured by dynamic susceptibility contrast MR technique. Acta Radiol 2001; 42: 123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moteki T, Horikoshi H. Evaluation of hepatic lesions and hepatic parenchyma using diffusion-weighted echo-planar MR with three values of gradient b-factor. J Magn Reson Imaging 2006; 24: 637–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Callot V, Bennett E, Decking UKM, et al. In vivo study of microcirculation in canine myocardium using the IVIM method. Magn Reson Med 2003; 50: 531–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yao L, Sinha U. Imaging the microcirculatory proton fraction of muscle with diffusion-weighted echo-planar imaging. Acad Radiol 2000; 7: 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Granata V, Fusco R, Catalano O, et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) in diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) for hepatocellular carcinoma: correlation with histologic grade. Oncotarget 2016; 7: 79357–79364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fusco R, Sansone M, Petrillo A. A comparison of fitting algorithms for diffusion-weighted MRI data analysis using an intravoxel incoherent motion model. MAGMA 2017; 30: 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Granata V, Fusco R, Catalano O, et al. Early assessment of colorectal cancer patients with liver metastases treated with antiangiogenic drugs: the role of intravoxel incoherent motion in diffusion-weighted imaging. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0142876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fusco R, Sansone M, Petrillo A. The use of the Levenberg–Marquardt and variable projection curve-fitting algorithm in intravoxel incoherent motion method for DW-MRI data analysis. Appl Magn Reson 2015; 46: 551–558. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim JH, Lee JM, Park JH, et al. Solid pancreatic lesions: characterization by using timing bolus dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging assessment–a preliminary study. Radiology 2013; 266: 185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bali MA, Metens T, Denolin V, et al. Tumoral and nontumoral pancreas: correlation between quantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging and histopathologic parameters. Radiology 2011; 261: 456–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kang KM, Lee JM, Yoon JH, et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion weighted MR imaging for characterization of focal pancreatic lesions. Radiology 2014; 270: 444–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Klau M, Mayer P, Bergmann F, et al. Correlation of histological vessel characteristics and diffusion-weighted imaging intravoxel incoherent motion-derived parameters in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Invest Radiol 2015; 50: 792–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen Y, Ren W, Zheng D. Diffusion kurtosis imaging predicts neoadjuvant chemotherapy responses within 4 days in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015; 42: 1354–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yu J, Xu Q, Song JC, et al. The value of diffusion kurtosis magnetic resonance imaging for assessing treatment response of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Eur Radiol 2017; 27: 1848–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Goshima S, Kanematsu M, Noda Y, et al. Diffusion kurtosis imaging to assess response to treatment in hypervascular hepatocellular carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015; 204: W543–W549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]