Abstract

Purpose

To explore patients’ perspectives and experiences living with glaucoma and identify important benefits and risks that patients consider before electing for new glaucoma treatments, such as minimally invasive glaucoma surgical (MIGS) devices.

Design

Semi-structured, in-person qualitative interviews with patients seen at the Johns Hopkins Wilmer Eye Institute.

Participants

Adults older than 21 years of age who were suspected or diagnosed with ocular hypertension or mild to moderate primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) (and thus eligible for treatment with a MIGS procedure) presenting to a glaucoma clinic in Baltimore, Maryland, between May and December 2016.

Method

We conducted in-person interviews with patients recently diagnosed with ocular hypertension or POAG. We focused on considerations patients take into account when deciding between different treatments. We used the framework approach to code and analyze the qualitative data. Considerations of special interest to us were those that can be translated into outcomes (or endpoints) in clinical trials.

Main outcome measures

Patients’ perspectives concerning outcomes that matter to them when managing ocular hypertension or POAG.

Results

Ten male and fifteen female patients participated in our study. The median participant age was 69 years (range 47 – 82 years). We identified outcomes that patients expressed as important, which we grouped into four thematic categories: (1) limitations in performing specific vision-dependent activities of daily living; (2) problems with general visual function or perceptions; (3) treatment burden, including ocular adverse events; and (4) intraocular pressure (IOP). All 25 participants expressed some concerns with their ability to perform vision-dependent activities, such as reading and driving. Most (23/25) participants had an opinion about IOP, and among those currently taking ocular hypotensive eye drops, all recognized the relationship between eye drops and IOP.

Conclusion

We have identified outcomes that matter to patients who are deciding between different treatments for ocular hypertension and POAG, such as the ability to drive or maintain mobility outside the home. These outcomes will be important in future evaluations of new treatments for glaucoma.

PRÉCIS

We conducted qualitative, semi-structured interviews with patients recently diagnosed with glaucoma to better understand patients experiencing living with glaucoma and explore what matters to people who are in the process making treatment decisions.

INTRODUCTION

Primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) is a common eye disease defined by a characteristic pattern of optic nerve damage with an associated loss of vision.1–3 POAG not only causes loss of peripheral vision but also central vision and even loss of light perception. Reducing elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) may slow the progression of POAG.4 Management strategies aim to control or lower IOP include topical medications, laser treatment, incisional surgery (e.g., trabeculectomy), and, more recently, implantation of minimally invasive glaucoma surgical (MIGS) devices.1

Patients have unique perspectives about glaucoma and perspectives about its treatment. Because clinicians, researchers, and regulators such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) play critical roles in communicating the benefits and risks of treatment, it is important that patients’ preferences are taken into account.5,6 Patients’ preferences, once identified, for example, can potentially be incorporated into the development, evaluation, and labeling of medical products.7,8

Qualitative research methods are one systematic approach to identify patients’ preferences. Sackett (1997) considers methods, such as interviewing patients seeking care for a particular condition one-on-one, as “the best source of data on individuals’ values and experiences in health care.”9 The objective of this study is to explore what matters to patients recently diagnosed with ocular hypertension or mild to moderate POAG through a series of qualitative, semi-structured interviews. Understanding how people experience glaucoma informs design of future evaluations of interventions, such as the selection of outcomes (or endpoints) to measure and comparison groups to include in trials.

METHODS

Study Design Overview

We conducted a qualitative study using semi-structured, one-on-one, in-person interviews with patients presenting to the Wilmer Eye Institute (“Wilmer”) in Baltimore, Maryland, from May to December 2016. We used the Framework Approach to analyze the qualitative data, which involves inductively deriving patterns (“themes”) from the narrative experiences and views of the participants.10,11 The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH) Institutional Review Board approved this study (JHSPH IRB #6987). We obtained consent from all participants and collected data in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.12

Setting, Participants, and Recruitment

Eligible participants were English-speaking adults older than 21 years of age who were suspected of having or diagnosed with mild to moderate POAG (and thus eligible for treatment with a MIGS procedure) in at least one eye who were seen in the glaucoma clinic between May and December 2016 at Wilmer. Diagnosis was based on a visual field test, using the Humphrey VF 24–2 SITA-Standard testing. We excluded patients with angle-closure glaucoma and those who had received glaucoma surgery (trabeculectomy or placement of a glaucoma drainage device) previously. We did not exclude patients if they had other ophthalmic diseases such as cataract or age-related macular degeneration.

Given the objective of this study, we used convenience sampling methods to recruit participants. Two ophthalmologists from Wilmer referred any patient meeting the eligibility criteria. The interviewer (JL) contacted referred patients by phone approximately 1 week before their next eye appointment. The interviewer scheduled in-person interviews with patients who agreed to participate. All interviews were in English, were 1 hour or less in duration, one-on-one, and took place in a private meeting room at Wilmer immediately before or after each patient’s clinic appointment. In appreciation of participant’s time, the interviewer provided each person with a parking voucher. We conducted interviews until reaching we reached saturation, i.e., when no new views or ideas emerged from the interviews.13

For participants who consented to participating in the study, we extracted from their medical records information on visual acuity (measured in habitual distance correction, without pinhole enhancement) and visual field testing at the visit closest to the date of interview, glaucoma diagnosis, history of IOP-lowering eye drops use, and comorbidities such as cataract and age-related macular degeneration.

Interview Guide

Through a series of teleconferences, we engaged with experts from the FDA, the American Glaucoma Society, clinical trialists, and patients with glaucoma to determine important topics that could generate information pertaining to patients’ preferences for treatment. We constructed an interview guide that explored three areas related to treatment decision-making, with an emphasis on new modalities such as MIGS procedures: (1) “living with glaucoma”, (2) “understanding (new) treatment choices available”, and (3) “getting treatment for glaucoma” (Appendix 1). We updated key questions on the guide iteratively during the course of the interviewing to improve clarity based on responses of prior patients.

Data Collection

The interviewer (JL) is a qualitative research methodologist with experience in ocular and vision research. The interviewer obtained oral informed consent. The interviewer used the interview guide to direct discussion towards identifying outcomes related to benefits and risks that may be perceived as important to participants without giving them the list of key questions. Participants could diverge from questions on the interview guide and discuss issues that were important to them. Additionally, to give participants time to feel comfortable with the process and the interviewer, the interviewer did not ask sensitive questions (e.g. role in the community, impact on family) until later in the interviews. Interviews were audio-recorded and then professionally transcribed verbatim. We did not collect, record, or transcribe protected health information in the interviews.

Data Analysis

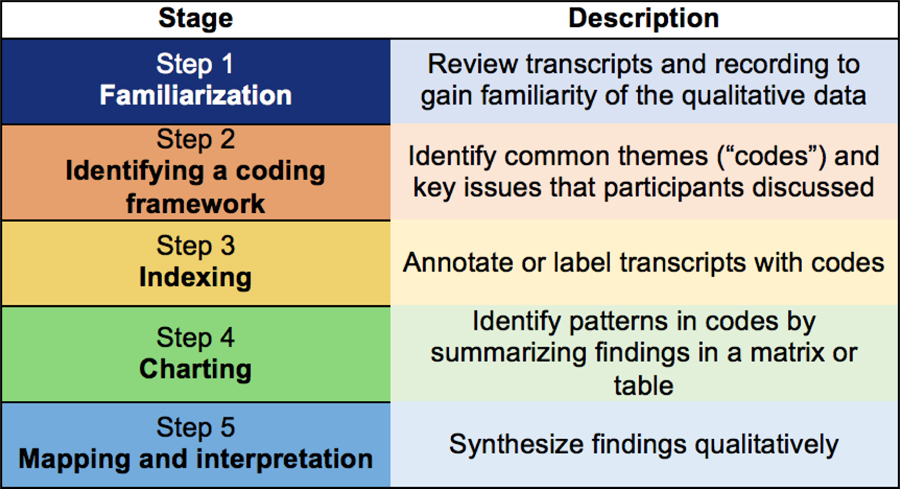

We tabulated participant characteristics. We analyzed transcripts using Atlas.ti software (version 7.5.12; Scientific Software Development GmbH) and the Framework Approach, a qualitative research methodology leveraging both deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis (Figure 1).14

Figure 1.

Summary of the coding process

The interviewer re-read transcripts in their entirety and compared them with the audio-recorded interviews to ensure accuracy (Familiarization). He conducted preliminary coding after each interview to develop a coding scheme (Framework) based on study aims and the qualitative data: some codes were derived from a glaucoma-specific item bank “framework” (e.g., ocular surface symptoms);15 other codes were developed inductively from the patients’ own words (e.g., reducing frequency of eye drops taken). Independent from the interviewer, a research assistant (KM) and a glaucoma specialist (AB) who were not present during the interview also reviewed and re-coded the transcripts using the finalized coding framework (Indexing). The team met regularly to review raw data, disagreements in coding, emerging minor themes not in the original framework, and analytic notes.

We summarized the participants’ narratives and organized this information in a matrix format, where each row represented a participant and each column represented a code (Charting). We looked for patterns and exemplary quotes across responses. Finally, we grouped the codes into thematic categories reflecting outcomes that could be evaluated in future glaucoma clinical trials.16,17

RESULTS

We reached saturation after conducting one-on-one interviews with 25 participants (10 men and 15 women). Most participants (17/25, 68%) were older than 65 years of age, without cataract (15/25, 60%), and did not have AMD (24/25, 95%). Patients with significant visual impairment (logMAR VA >0.4) attributable to non-glaucomatous ocular pathology were excluded from this study. We did include patients with comorbid age-related cataracts (no more than 2+ nuclear sclerosis in either eye). Four participants had the following additional diagnoses: amblyopia arising from childhood strabismus (logMAR VA 0.88 in the affected eye, 0.00 in the fellow eye), mild age-related macular degeneration (logMAR VA 0.18 OU); history of macular hole repair (logMAR VA 0.18 in the affected eye, 0.00 in the fellow eye); history of retinal detachment repair and macular hole repair (logMAR VA 0.40 in the affected eye, 0.00 in the fellow eye).

Most participants were diagnosed with mild (12/25, 48%) or moderate (8/25, 32%) POAG. We report mean deviation and pattern standard deviation in visual field testing in Table 1; the median time between the most recent visual test and the interview was 80 days (interquartile range: 0 – 140 days). The majority of participants (19/25, 76%) were currently taking IOP lowering eye drops at the time of the interview.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 25 participants interviewed

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 15 (60) |

| Male | 10 (40) |

| Age, median (range) | 69 (47 to 82) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Black | 12 (48) |

| White | 9 (36) |

| Asian | 3 (12) |

| Others | 1 (4) |

| Visual acuity* - mean logMAR, (SD; range) | |

| Better eye | 0.03 (0.06; 0 to 0.18) |

| Worse eye | 0.17 (0.19; 0 to 0.88) |

| Visual field - MD, mean dB (SD; range) | |

| Better eye | −1.68 (2.92; −7.74 to 2.51) |

| Worse eye | −5.08 (3.54; −11.55 to 0.53) |

| Visual field - PSD, mean dB (SD; range) | |

| Better eye | 2.47 (1.49; 1.16 to 7.89) |

| Worse eye | 5.75 (3.50; 1.67 to 12.68) |

| Glaucoma diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Ocular hypertension | 5 (20) |

| Mild primary open angle glaucoma | 12 (48) |

| Moderate primary open angle glaucoma | 8 (32) |

| Use of IOP-lowering eye drops, n (%) | |

| Currently on eye drops | 19 (76) |

| Formerly on eye drops | 4 (16) |

| Never on eye drops | 2 (8) |

| History of selective laser trabeculoplasty, n (%) | |

| Yes | 4 (16) |

| No | 21 (84) |

| Cataract/Lens status, n (%) | |

| Phakic without cataract, both eyes | 7 (28) |

| Pseudophakic, both eyes | 5 (20) |

| Pseudophakic, one eye | 3 (12) |

| Cataract, both eyes | 10 (40) |

| Age-related macular degeneration diagnosis, n (%) | |

| No | 24 (96) |

| Yes | 1 (4) |

visual acuity measured in habitual distance correction (with or without corrective lenses, using the patient’s own correction) without pinhole enhancement; SD= standard deviation; MD = Mean Deviation; PSD = Pattern Standard Deviation

We identified outcome domains that were important to participants. We grouped the domains into four thematic categories, related to: (1) limitations in performing specific vision-dependent activities of daily living; (2) problems with general visual function or perceptions; (3) burden of medical treatment, including ocular adverse events; and (4) intraocular pressure.

1. Outcomes related to limitations in performing specific vision-related activities of daily living (e.g. reading, driving, and navigating physically)

All 25 participants living with ocular hypertension or POAG expressed some concerns with their ability to perform vision-dependent activities. Almost all (24/25, 96%) participants discussed concerns with difficulty performing routine tasks such as reading and mobility.

1.1. Patients noticed how their reading ability worsened since first being diagnosed with glaucoma.

Difficulty reading fine print was a common complaint, and most (24/25, 96%) participants complained of having “bad” eyesight. Oftentimes, participants brought materials closer to their eyes in order to make out words. Participants commented that doing so resulted in decreased reading speed.

“To me, glaucoma means that my vision is going, or is narrowing down to where I can only see certain aspects in front of me clearly…there was a time I could read [everything in front of me] and now I got to read it closer and I got to read it slower to get an understanding of what I’m reading.” (Participant 7)

“There was a time I could take this [piece of paper] and read it. I could read it, right? But now I have to take my time and focus on each word to make an understanding of what I’m reading.” (Participant 18)

“Now it’s hard for me sometimes to see words unless I put the [news]paper real close, and I can see for distance sometimes. My eyesight is bad.” (Participant 8)

Difficulty reading had prevented some participants from doing what they were able to do in the past, which may also have affected the roles they play in the family and in the community, their participation at social gatherings, or how they carried out daily activities.

“[I]f we’re having Bible study or something like that…I’d rather for somebody else to read--the print is so small.” (Participant 15)

“When reading the ATM computer screen, sometimes you got to focus a little bit, about five, ten second to read everything. You cannot read immediately on the screen.” (Participant 23)

1.2. Patients described modifying their driving habits when they have trouble seeing off to the side.

Most (22/25, 88%) of the participants we interviewed were still driving. Participants expressed frustration over having to modify their driving habits. They mentioned this as a safety concern.

“I’m particularly now conscious that if I have to turn left, I have to actually turn [my head] where you normally wouldn’t normally have to turn as much as I turn. But I’m sort of trying to compensate for the lack of peripheral vision. So that’s, I think, particularly the issue. (Participant 13)

“When we’re driving, sometimes I see that one lane has become two lanes, or something like that. So that’s why I went to see my family doctor.” (Participant 23)

Participants who drive also noted that difficulty driving is sometimes more pronounced at night. This may be due to glare from streetlights and other vehicles (see 2.3). One participant noted that visual symptoms were the reason why they stopped driving altogether.

“When I drive at night, [the glare] is first an annoyance and then more of a concern because I’ve realized that this is a safety issue…and if I have to drive somebody else, then it makes me even more nervous.” (Participant 13)

“My problem I have with driving is at night. I can see but not as far, and bright lights—I hate that. I hate lights that—car lights coming to me. I can see, but it narrows [my field of vision]…the lights are blinding me.” (Participant 18)

“I’ll tell you why I stopped driving too is that street lights and the headlights, they were like streamers and that’s one of the reasons I stopped driving at night.” (Participant 15).

1.3. Patients experienced difficulties navigating inside and outside their home.

More than half (15/25, 60%) of the participants we interviewed brought up concerns about their ability to move around inside the home, outside the home, or both. Inside the home, a common obstacle for participants were stairs:

“I used to run up [the stairs in my house] but I’m a little slow now…as protection, I come down a little slow. I hold on to the banister and come down a little slow.” (Participant 4)

“Well, I’m a little more cautious. You know, I want to be sure that I know where the stairs are, you know, just a little cautious with that.” (Participant 10)

“I do what my grandson tells me, “Hold the railing, Grandma.” (Participant 16)

Participants who had trouble moving around inside the home made minor modifications such as adding nightlights or adding grips and other features to stairwells, bedrooms, and bathrooms. Others adapted to improve their awareness of their surrounding and moved furniture that may have served as impediments.

“I’ve learned to put my hand out to guide me so I don’t walk into the wall or nothing like that” (Participants 15)

“Once you are aware [of your surroundings], half [of] the problem—I mean, half [of] the danger is gone.” (Participant 25)

Participants described how moving outside the home is difficult because terrains are less familiar and can change depending on the season. For example, two patients noted how it was more difficult to ambulate where sidewalks and streets may be uneven or covered by rain and snow.

“I like to see where I am going…The winter is hard on the body. Walking over the ice and stuff to get the bus…you gotta step up on it [or lest] you slide down to the street.” (Participant 4)

“We were outside, and I think I slipped on gravel, onto the pavement. Now that’s something where had there been better lighting, I might well have seen [the uneven surface].” (Participant 22).

2. Outcomes related to perception of vision

Most (23/25, 92%) of the participants whom we interviewed expressed concerns that the quality of their vision may be changing after they were diagnosed with ocular hypertension or POAG. These changes included loss of peripheral vision, blurry vision, difficulties seeing in very bright or very dim conditions.

2.1. Patients noticed that they cannot see off to the side when looking straight ahead.

We observed that participants were able to differentiate between central and side (peripheral vision); some had begun noticing loss of side vision.

“Right now with both eyes open I see no difference. The only thing is if I close my one eye, the only way I can do is if I close my one eye and I bring my hand over and this hand over, okay, I can see right to there. But if I close this hand, I can see over there. So I know that bringing my hand in, I can see that I have a little bit of loss, nasally.” (Participant 21)

“If you can’t see if somebody standing on your side and you can’t see it. Yeah, that might be a sign of you losing your sight.” (Participant 11)

2.2. Patients described loss of peripheral vision as seeing through a fog or blur.

Perception with visual field loss is a complex process where the brain must fill in missing pieces. We limited our interviews to POAG suspects and people with mild to moderate POAG who have not experienced severe loss of vision; yet, several participants described having distorted or blurry vision.

“Sometimes it’s kind of foggy. Depends on where I’m looking at, but usually the left side” (Participant 8)

“Well, the problematic is on the peripheral…it’s blurry and hard to see or distinguish…” (Participant 18)

2.3. Patients noticed that extreme lighting conditions—either very bright light or very dim environments—have affected how much they can see.

About two thirds (17/25, 68%) of the participants described how different lighting conditions can make seeing or performing other tasks more difficult than before they had been diagnosed with ocular hypertension or POAG.

“…the biggest thing was being outside with the light. The brightness seemed to be the thing that stood out to me as the most bothersome aspect (of having glaucoma).” (Participant 1)

“…bright lights-- I hate car lights coming to me. I can see, but it narrows [how much I can see] because the lights are blinding me. “(Participant 18)

“In dim light, I notice I’m not seeing as clear as I can.” (Participant 19)

2.4. Patients reported difficulties gauging how far away an object might be.

About a third (9/25, 36%) of the participants noted some problems with depth perception, the ability to judge how far away an object is or to see objects in three dimensions. As described earlier, some participants expressed difficulties navigating stairs because they cannot see the steps. Others described similar issues, such as running into doors.

“I fell a couple years ago with one [mis]step, but I think it was mostly because it was in front of a glass door and I was looking for the door.” (Participant 12)

“I was going out the door and somebody called me and I reached back for the door, and it was one of them hospital doors that shut on its own…” (Participant 18)

“The loss of depth is pathetic. It’s pretty ridiculous. [You think] your brain will adjust. It doesn’t…. I rode horses, and I skied but I was not doing all the stuff that I typically used to do before because I just couldn’t predict the space where I was going to go.” (Participant 2)

2.5. Patients also described color vision defects, such as colors appearing dull and faded.

A few (5/25, 20%) participants discussed concerns with a distortion of color perception leading to an acquired loss of color vision. This may also be related to loss of contrast sensitivity, which is the ability to discern between subtle differences in patterns and shading.

“Everything seems a little gray, and like I say, narrowed down…Yeah, it seems a little gray. See, when I take my glasses off, it’s still a little gray.” (Participant18)

For one participant, vision is linked not only to how much she can see; it is the quality of that vision and whether she can still see color.

“[Loss of vision is] zero (vision), but it wasn’t zero, because you could see colors and things moving.” (Participant 20)

3. Outcomes related to treatment burden

About half (14/25, 56%) of the participants we interviewed found treatment, usually glaucoma eye drops, to be inconvenient. Common adverse events that participants experienced included teary eyes, red eyes, and changes in eye color.

3.1. Patients described having to take IOP-lowering eye drops as a “nuisance”

“[D]rops are a nuisance, but I try to do it… sometimes I forget, and then I have to call my daughter.” (Participant 20)

“Normal situation is you don’t take any eye drops. So I’m taking eye drops, and I hope someday I should be able to live normally, but I don’t think so.” (Participant 25)

“[Referring to eye drops] anytime you do something other than normal, it’s a little bit of an inconvenience.” (Participant 10)

Not all participants, however, were averse to eye drops: some compared glaucoma eye drops to other medications they were taking and did not mind adding glaucoma eye drops.

“I take heart medicine to control my heart rate. So I have to take that every day. So it’s not a big-- I don’t find glaucoma eye drops to be a big deal.” (Participant 13)

“Eye drops are not a big deal. I mean, I can still see. I mean, I can’t complain about anything, really.” (Participant 9)

“My eye drops are my religion.” (Participant 19)

We observed that some participants did not understand the purpose of the glaucoma eye drops.

“I’ll take them until they tell me to stop or whatever, because I don’t really know what the eye drops are about. I don’t know what they’re supposed to do to my eye or how they’re supposed to help my eye or anything.” (Participant 18)

“The idea as far as I know is to put the eye drops in my eye at night and say my prayers” (Participant 20)

3.2. Patients described dissatisfaction with how eye drops are administered

When participants found eye drops to be troublesome to self-administer, they relied on family members and other caretakers. Participants had trouble due to lack of dexterity; others had trouble keeping eyes opened.

“If I can’t find that right spot, I get my grandson or his girlfriend to put them in every night.” (Participant 8)

“I had some hard times when I had to use it which did not really fit well with my schedule…(because) when you put them on you had to sit down for some time before you could do something.” (Participant 16)

We observed that cost of glaucoma eye drops was not a source of dissatisfaction or burden for many participants interviewed. Patients described how their insurance often covered the eye drops.

“Cost was never a concern because two things. One, I have very good insurance. And two, it’s my eyes so, no.” (Participant 2)

“Cost [of the eye drops] wasn’t the concern. The concern was, as I said to you before, I just didn’t want to be medicated.” (Participant 24)

3.3. Patients experienced adverse events due to IOP-lowering eye drops, including discomfort and dry or teary eyes.

Some participants were concerned with the adverse effects experienced when taking eye drops. The participants we interviewed described mostly reactions that occurred on the ocular surface.

“I kind of had a reaction, redness and that sort of thing” (Participant 5)

“It’s very insidious [referring to the redness/rash]… [my eye] itched like hell…Itching is a synonym for hurting, for pain…” (Participant 16)

“I never had to take eye drops before. I did realize that they’re just like pills that they can have bad side effects, you know…So I’m drinking coffee and there’s this foreign taste.” (Participant 17)

“I noticed my eyes were red all the time. Like really, really red all the time. It just looked like I was, you know, always drunk or something like that.” (Participant 7)

3.4. Patients reported concerns over eye drops altering the color of their eyes

Two participants were concerned with how certain glaucoma eye drops (e.g., prostaglandin analogs) can change the color of their eye. They described how the color of their eyes were tied to their identify and self-perception.

“I’m concerned that my color of my eyes will be changed, because I have blue eyes… I like blue eyes. I have always had blue eyes. It’s part of me. It’s on my passport…” (Participant 16)

“I feel like <laughs> when you get to be like-- your whole body is changing when you’re 60, and it’s like I don’t want it changing my eye color too. Everything else is changing by itself. I want to keep my eye color the same…” (Participant 1)

4. Outcomes related to intraocular pressure

Finally, all participants (25/25, 100%) discussed controlling IOP as an outcome of treatment; however, understanding what IOP is and why it is being controlled was variable among the participants we interviewed.

4.1. IOP is not something that patients associate with noticeable functional changes

“As opposed to things like arrhythmia…[which] you can feel… IOP is not a visible every day constant reminder of the glaucoma.” (Participant 5)

“The pressure was not really affecting me in any way. I didn’t feel that much changed, except when you come to the hospital and they measure the pressure and they said I have [high] pressure.” (Participant 6)

4.2. Not all patients with glaucoma have elevated IOP

We observed that even participants who did not have elevated IOP were aware of IOP.

“My eye pressure’s always been normal. I’ve never used eye drops…I’m not sure and I don’t think the doctor knows necessarily why or how it happened. It just happened.” (Participant 22)

“You hear people get glaucoma because of high eye pressures. Well, I don’t have high eye pressures.” (Participant 10)

“I mean you don’t feel it, you don’t know that you have it, there’s nothing different happens.” (Participant 3)

4.3. Patients are aware that IOP may be related to glaucoma

Not all participants understood what IOP is, but they were aware that IOP is related to their glaucoma and the treatment they were currently receiving at the glaucoma clinic.

“If this pressure is being relieved with the eye drops they don’t have to do surgery.” (Participant 20)

“[IOP is] pressure that could, if not treated, as worst case scenario, result in blindness.” (Participant 5)

“I only know is that if it don’t -- if it’s not under control, I could lose my vision.” (Participant 17).

“IOP is really important. I mean, that’s the whole reason I’m here, right?…It’s like blood pressure. You can’t tell. You have to have it checked somehow.” (Participant 1)

4.4. There are misconceptions concerning IOP and glaucoma

Additionally, we observed misconceptions concerning the relationship between IOP and glaucoma. For example, participants may have believed that their IOP measurement determined whether or not they had glaucoma.

“Well the pressure is what determines you to be a glaucoma patient and that’s just like high blood pressure.” (Participant 15)

“The number, if it’s a higher number, it goes down low and you feel like it’s getting better. ‘Cause it’s like your sugar.” (Participant 4)

“I know that [glaucoma] is cancer of the eye.” (Participant 20)

DISCUSSION

From patients who, as a collective, have a range of perspectives, we found that many of the outcomes experienced by patients with ocular hypertension or POAG are related to: (1) limitations in performing vision-dependent activities of daily living; (2) problems with visual functions or perceptions; (3) burden of medical treatment; and (4) IOP. The development, evaluation, and labeling of new interventions for glaucoma could potentially benefit from inclusions of these types of outcomes.

Our findings extend the existing body of qualitative research involving patients with ocular hypertension or mild to moderate POAG. Previous qualitative research on the experience of patients living glaucoma has looked predominantly at barriers to glaucoma screening or medication adherence, rather than preferences or quality of life.18–20 Several interview-based studies also examined the impact of glaucoma on daily life. These studies, which recruited between 16 and 28 participants from the United Kingdom or Turkey, focused on management of severe forms of POAG in patients who have already experienced noticeable loss of vision. The investigators recommended more attention towards reducing environmental and social causes of impairment;21 highlighted the importance of cultural and religious practices in helping patients cope;22 and urged future researchers to recognize patient education as a management strategy for glaucoma.23

Our study design adopted a holistic approach to glaucoma treatment by focusing on the individual rather than the disease. We recognize that information which participants shared with us during interviews do not necessarily represent physiological consequences of glaucoma; rather, they are outcomes experienced by patients who have glaucoma. Thus, it is possible that patients have other vision-impairing comorbidities such as cataract or that their inability to perform certain activities of daily tasks may be due to aging.

Our patient-centric approach adds to ongoing disease-centric efforts identify important outcomes for glaucoma research. For example, a Delphi survey of glaucoma specialists in the United Kingdom and Europe reached consensus on IOP, visual field defects, and anatomic outcomes (such as retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness and optic nerve head morphology) as core outcomes for glaucoma effectiveness trials.24 We observed that not all participants whom we interviewed expressed glaucoma in terms of physiological or anatomical changes, and among those who did, all noted that IOP is not something they can feel or measure at home. Similarly, studies leveraging psychophysical tests or factor analysis of visual disability questionnaires have identified common problems encountered by patients with POAG (e.g., the ability to drive).23,25–27 By using a qualitative approach, we provide contextual evidence grounded in information provided by patients to explain what those outcomes really mean to patients. For example, our participants described how being able to drive a car at night is different from being able to drive during the day.

Patient perspectives concerning the outcomes of glaucoma treatment varied. Throughout our interviews with POAG patients, it was clear that many participants have internalized IOP as a number that must be monitored and controlled. While a physiological outcome such as IOP can help expedite the development and evaluation of new interventions, it makes sense not to ignore what else keeps patients functioning and feeling optimal. Almost all participants described how noticing changes in driving habits or reading abilities led to their decision to seek care and treatments that would preserve their ability to perform vision-dependent activities. Others emphasized how treatment must not alter the color or appearance of their eyes. It is possible that some patients may have other co-existing eye conditions such as cataract, which may have influenced their opinions.

The convenience sampling approach enabled us to purposely identify people seeking treatment for glaucoma who were willing to talk about their experience. All participants were able to travel to Baltimore to take part in the study. Consistent with other qualitative studies which used this approach,21 participants were inquisitive and proactive, allowing us to reach a saturation of ideas after 25 interviews. While the representativeness of our findings may be more reflective of the sample studied, our goal was to generate a list of key outcomes that can be validated by others.

Notably, many of the outcomes that participants described (such as the ability to drive a car or reading fine print), are not outcomes that have been measured consistently in MIGS studies.7,8 Clinical trials often focus on demonstrating efficacy in controlled environments using design attributes that have evolved to ensure expeditious, clear answers to narrowly framed research questions.28 Furthermore, the outcomes selected in clinical trials and other research on glaucoma are considerably variable.29,30 This is concerning because trials focusing on surrogate measures (such as IOP) or biomarkers alone raise questions regarding the applicability of the findings to real-world medical practice. Ideally, incorporation of outcomes that capture function, treatment burden and visual perceptions from patients’ point of view should be considered in future clinical trials.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful for feedback which we received from the AGS PROM for MIGS Working Group and the FDA/Cross-CERSI Project on MIGS.

FUNDING

This project was made possible by Grant Number U01FD005942 from the FDA, which supports the Johns Hopkins Center of Excellence in Regulatory Sciences. The mention of commercial products, their sources, or their use in connection with material reported herein is not to be construed as either an actual or implied endorsement of such products by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). JTL was supported by the Epidemiology and Biostatistics of Aging Training Program, Grant Number T32 AG000247 from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. This manuscript was prepared when JTL was a research assistant at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States government.

Appendix 1. Example Interview Guide

| Major domains and example prompts & directing of discussion |

|---|

| 1. Introduction & general discussion |

| [Explain the purpose of the interview] |

| Could you tell me about yourself and what does “having glaucoma” mean to you? |

| When did you find out you had glaucoma? How did you find out? |

| How did your doctor explain to you that you had glaucoma/elevated IOP? |

| 2. Getting treatment for glaucoma |

| Tell me about what kind of treatment you had for elevated IOP and glaucoma? |

| How long was your treatment? Are you still on treatment? [What kind of treatment?] |

| What do you think were your greatest needs as you are going through treatment? |

| Why did you/did you not choose surgery? |

| Would you consider a minimally invasive procedure? |

| Has getting treatment impacted or restricted your lifestyle in any way? |

| What’s the worst thing about your glaucoma treatment? What do you find the most annoying? inconvenient? |

| Tell me about how getting treatment may impact or restrict your current lifestyle? |

| 3. Understanding the treatment choices available |

| How do you talk to your [doctor/family/friend] about glaucoma? |

| Do you believe that you knew what to expect in terms of what life was going to be like as you were deciding to get glaucoma treatment or treatment to lower your IOP? What were you expecting from your [eye drops, surgery, laser, MIGS, etc] treatment? |

| Are there aspects of your glaucoma treatment that you feel that you didn’t understand? |

| Where do you get information about your glaucoma? Where do you get information about treatment options for glaucoma? |

| Do you look for health information online, e.g. YouTube videos, forums and chatrooms? |

| Are there areas concerning your glaucoma treatment for which you would have liked more information? [More information about side-effects and adverse events?] |

| 4. Living with glaucoma |

| How does your glaucoma impact you emotionally? How do you feel about your glaucoma in the long run? |

| What are you not able to do now that you were able to do before you were diagnosed with glaucoma? |

| In what way has glaucoma affected how you perceive yourself? |

| What things have changed for you as a person since developing glaucoma? |

| In what ways does your glaucoma affect your social life? Do you feel you are missing out from social occasions? From leisure activities because of your glaucoma? |

| In what way has glaucoma impacted your family? Your friendships? |

| What is your biggest concern about having glaucoma? |

| What are some worries or fears about your glaucoma? |

| When you think of glaucoma, what things are on your mind? |

| How has glaucoma affected your role in the community? |

| What sort of visual symptoms do you experience because of your glaucoma? |

| Have you experience any eye pain? Blurry vision? Difficulty seeing? |

| Tell me about your eye pain, blurry vision, difficulties seeing… |

| Do you have any physical limitations? |

| Think about the last time you travelled? Can you describe how glaucoma affected this? |

| [General discussion about “having glaucoma,” elevated IOP or living with the disease.] |

| 5. Other |

| How does glaucoma affect you at work? Financially? |

| What unwanted adverse events have you experienced because of your treatment? |

| How do different lighting conditions affect your vision? |

| Do you have other needs or concerns about your glaucoma treatment that we have not addressed? |

| Are there other aspects of living with glaucoma that you would like to discuss? |

| What do you think the ideal glaucoma treatment should have? |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health IRB (#6987). We obtained consent from all participants and we followed all participant data collection methods in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

MEETING PRESENTATIONS

2018 Meeting of the American Glaucoma Society; New York City, New York

CONFLICT OF INTERST

No conflicting relationship exists for any author

REFERENCES

- 1.American Academy of Ophthalmology. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Preferred Practice Patterns. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology 2010; http://one.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/primary-openangle-glaucomapppeoctober-2010. Accessed November 18, 2015.

- 2.Friedman DS, Wolfs RC, O’Colmain BJ, et al. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122(4):532–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90(3):262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medeiros FA. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in glaucoma clinical trials. Br J Ophthalmol 2015;99(5):599–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarver M, Eyldelman M. Incorporating Patients’ Perspectives. Glaucoma Today 2017; http://glaucomatoday.com/2017/04/incorporating-patients-perspectives. Accessed April 15, 2018.

- 6.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry patient preference information –voluntary submission, review in premarket approval applications, humanitarian device exemption applications, and de novo requests, and inclusion in decision summaries and device labeling. 2016.

- 7.Le JT, Viswanathan S, Tarver ME, Eydelman M, Li T. Assessment of the Incorporation of Patient-Centric Outcomes in Studies of Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgical Devices. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016;134(9):1054–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui QN, Singh K, Spaeth GL. From the Patient’s Point of View, How Should Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgeries Be Evaluated? Am J Ophthalmol 2016;172:xii–xiv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sackett DL, Wennberg JE. Choosing the best research design for each question. BMJ 1997;315(7123):1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ 1995;311(6996):42–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research In: Bryman A, Burgess R, eds. Analysing qualitative data. London: Routledge; 1993:173–194. [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014;89(9):1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuper A, Lingard L, Levinson W. Critically appraising qualitative research. BMJ 2008;337:a1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320(7227):114–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khadka J, McAlinden C, Craig JE, Fenwick EK, Lamoureux EL, Pesudovs K. Identifying content for the glaucoma-specific item bank to measure quality-of-life parameters. J Glaucoma 2015;24(1):12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saldanha IJ, Dickersin K, Wang X, Li T. Outcomes in Cochrane systematic reviews addressing four common eye conditions: an evaluation of completeness and comparability. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, Califf RM, Ide NC. The ClinicalTrials.gov results database--update and key issues. N Engl J Med 2011;364(9):852–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park MH, Kang KD, Moon J, Korean Glaucoma Compliance Study G. Noncompliance with glaucoma medication in Korean patients: a multicenter qualitative study. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2013;57(1):47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacey J, Cate H, Broadway DC. Barriers to adherence with glaucoma medications: a qualitative research study. Eye (Lond) 2009;23(4):924–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordmann JP, Denis P, Vigneux M, Trudeau E, Guillemin I, Berdeaux G. Development of the conceptual framework for the Eye-Drop Satisfaction Questionnaire (EDSQ) in glaucoma using a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green J, Siddall H, Murdoch I. Learning to live with glaucoma: a qualitative study of diagnosis and the impact of sight loss. Soc Sci Med 2002;55(2):257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iyigun E, Tastan S, Ayhan H, Coskun H, Kose G, Mumcuoglu T. Life Experiences of Patients With Glaucoma: A Phenomenological Study. J Nurs Res 2017;25(5):336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glen FC, Crabb DP. Living with glaucoma: a qualitative study of functional implications and patients’ coping behaviours. BMC Ophthalmol 2015;15:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ismail R, Azuara-Blanco A, Ramsay CR. Consensus on Outcome Measures for Glaucoma Effectiveness Trials: Results From a Delphi and Nominal Group Technique Approaches. J Glaucoma 2016;25(6):539–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crabb DP, Smith ND, Glen FC, Burton R, Garway-Heath DF. How does glaucoma look?: patient perception of visual field loss. Ophthalmology 2013;120(6):1120–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson P, Aspinall P, Papasouliotis O, Worton B, O’Brien C. Quality of life in glaucoma and its relationship with visual function. J Glaucoma 2003;12(2):139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson P, Aspinall P, O’Brien C. Patients’ perception of visual impairment in glaucoma: a pilot study. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83(5):546–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherman RE, Davies KM, Robb MA, Hunter NL, Califf RM. Accelerating development of scientific evidence for medical products within the existing US regulatory framework. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017;16(5):297–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saldanha IJ, Lindsley K, Do DV, et al. Comparison of Clinical Trial and Systematic Review Outcomes for the 4 Most Prevalent Eye Diseases. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017;135(9):933–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ismail R, Azuara-Blanco A, Ramsay CR. Outcome Measures in Glaucoma: A Systematic Review of Cochrane Reviews and Protocols. J Glaucoma 2015;24(7):533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]