Abstract

OPREVENT2 was a multilevel, multicomponent (MLMC) adult obesity prevention that sought to improve access and demand for healthier food and physical activity opportunities in six Native American communities in the Southwest and Midwest. OPREVENT2 worked with worksites, food stores, schools (grades 2–6), through social media and mailings, and with a local community action committee (CAC), in each of the three intervention communities, and was implemented in six phases. We conducted a process evaluation to assess implementation of each intervention component in terms of reach, dose delivered and fidelity. Implementation of each component was classified as high, medium or low according to set standards, and reported back at the end of each phase, allowing for improvements. The school and worksite components were implemented with high reach, dose delivered and fidelity, with improvement over time. The school program had only moderate reach and dose delivered, as did the social media component. The CAC achieved high reach and dose delivered. Overall, study reach and dose delivered reached a high implementation level, whereas fidelity was medium. Great challenges exist in the consistent implementation of MLMC interventions. The detailed process evaluation of the OPREVENT2 trial allowed us to carefully assess the relative strengths and limitations of each intervention component.

Introduction

Obesity and related chronic diseases disproportionately affect Native American populations [1–7]. Multiple determinants exist for these high disease rates, at many levels, including historical treatment of Native American communities, living on isolated reservations with poor food access and sedentary behaviors. Most Native American reservations are rural, with a high proportion of households at or below the federal poverty level [8]. Rural Native American communities tend to have reduced access to paved roads, public transportation and supermarkets, and the retail food sources that are present in Native American reservations tend to carry a limited range of foods [9]. Even when on-reservation stores stock healthier foods and beverages, their price point tends to be higher than less healthy items [10, 11]. In Native American reservations, the built environment has been associated with low physical activity levels [12] and few resources are available for the development of recreation facilities and parks. Physical inactivity is more prevalent among Native American adults as compared to non-Hispanic whites [13–15]. Although physical activity is a strong part of Native American culture, levels waned as reservations became a way of life.

A large body of research has focused on obesity prevention trials in Native populations. The majority has centered on children in the school setting [16–18] such as the Pathways study, with most demonstrating modest success in changing individual behavior and the school environment, but no impact on obesity [19, 20] or the community or household environment [19, 21, 22]. This suggests that a more comprehensive approach to obesity prevention is needed to effectively reduce obesity among Native populations.

Multi-level, multi-component (MLMC) interventions work to address the complex determinants of obesity [23] by combining environmental, educational and policy strategies [24–28]. Most prior MLMC studies have focused on children and many show reduction in obesity risk in urban settings [26, 27, 29–31]. To date, only a few MLMC intervention trials have focused on attenuating obesity among Native American tribal communities—Obesity Prevention and Evaluation of InterVention Effectiveness in NaTive North Americans [32] and the current follow-up study called OPREVENT2 [32, 33]. Both studies focus on adults including children as change agents for families; include several intervention settings (food stores, worksites, schools and community media); and aim to reduce obesity by improving access, demand and consumption of healthier foods and beverages as well as increasing physical activity. The results from OPREVENT were modest, showing limited impacts on diet and psychosocial factors and no change to obesity [32]. The impact results from OPREVENT2 are not yet available.

However, given that process evaluations [34–37] can provide useful insights for contextualizing impact results and aiding the implementation of future trials, this paper explores the challenges and lessons learned from OPREVENT2. We have consistently utilized process evaluation—most often defined in terms of ‘reach’, the amount of target audience that participates in the intervention; ‘dose delivered’, the number of units delivered by interventionists; ‘dose received’, the extent to which the target audience actively engages in and receives intervention activities; ‘fidelity’ the quality of program delivery and extent to which it is delivered as planned; and ‘context’ the larger sociopolitical and environmental factors that may influence the intervention—in our previous trials in Baltimore City [38, 39] and in native communities around North America [37, 40]. For instance, process evaluation results of B’More Healthy Communities for Kids (BHCK) has shown a moderate reach of interventions to children in corner stores, and lower reach in winter months [38]. Both weather concerns and safety conditions limited opportunities staff and targeted youth could safely visit stores, thus decreasing opportunities for exposure to the intervention. On the other hand, social media activities of BHCK had high reach, dose delivered and fidelity—as these activities relied less on external factors such as weather and the presence of customers in stores [38, 41]. Additionally, our Baltimore work suggested that targeted mailings increased dose received and fidelity, as well as aided participant retention [38]. Process evaluation results from previous native trials also aided the design and implementation of OPREVENT2 such that minor changes like laminating and affixing all shelf labels in a more sturdy fashion, and major structural interventions, like the policy component, were included [37, 40].

Process evaluation findings of the OPREVENT pilot trial indicated low reach and exposure of the intervention. In particular, the physical activity component was underdeveloped, and reach was low due to lack of exposure to the community media utilized. OPREVENT2 sought to address some of those limitations. The purpose of this study assesses the implementation of the OPREVENT2 MLMC intervention by addressing the following questions:

How well was each OPREVENT2 intervention component implemented in terms of reach, dose delivered and fidelity, compared with set standards and across components?

What were the challenges and lessons learned during implementation? How best to balance limited resources in complex MLMC interventions?

Was intensity and integration of components sufficient to achieve desired impacts on diet, physical activity and obesity?

Materials and methods

Setting

OPREVENT2 took place in six rural Native American communities, located in the Midwestern and Southwestern regions of the US. Eligible communities had at least 500 households and at least: one worksite with 5+ employees, one elementary school and one food store located in the community. Multiple layers of approvals were received, including school board, chapter/tribal resolution, the local tribal Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Indian Health Services IRB and by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health IRB.

OPREVENT2 intervention trial

OPREVENT2 intervened simultaneously in multiple levels of the food and physical activity environments in six Native American communities, using a group randomized controlled design (Fig. 1). The six communities were randomized to intervention (n = 3) or comparison/delayed intervention (n = 3). OPREVENT2 study evaluation participants included 600 NA adults who lived in these six communities.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of the OPREVENT2 intervention.

The underlying theories that informed this work include social cognitive theory and the social ecological model [42–47], and sought to impact multiple community institutions at the same time, in order to modify both supply of healthier choices and demand for those choices. The study protocol is described in detail elsewhere [48].

The OPREVENT2 intervention was based on the OPREVENT1 pilot and formative research [32]. For OPREVENT2, extensive additional formative research, piloting of intervention materials/strategies in two new communities and a series of community workshops were conducted to develop and refine intervention strategies. Multiple community workshops were held in each of the intervention communities to review OPREVENT1 materials and approaches, leading to decisions about which materials should be retained, modified or scrapped, and which additional materials should be developed.

The OPREVENT2 intervention was delivered in six phases over an 18-month period (June 2017 to December 2018) with each phase lasting approximately 2–4 months. Each phase had a different theme that related to specific promoted behaviors, foods/beverages and physical activities (Table I).

Table I.

Phases and activities of the OPREVENT2 intervention

| Phase | Educational messages/promoted foods | Phase specific giveaways | Policy and environmental changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. OPREVENT2 Coming Soon |

|

Note pads, magnets |

|

| 2. Choose Wisely |

|

Water bottles, reusable shopping bags |

|

| 3. Make a Plan, Set a Goal |

|

Lunch bags, water bottles |

|

| 4. One Step at a Time |

|

Pedometers, Cloth workout towels, frisbees |

|

| 5. Make it Count, Make it Last |

|

Portion plates, jar openers, personal fans, seed packets |

|

| 6. Live Life in a Good Way/ Celebrating the New You |

|

|

|

All intervention components were implemented simultaneously (Table I), except for the school component, which had a delayed start associated with the beginning of the school year.

Description of intervention components

Food store component

The food store component aimed to increase supply and demand for healthier foods and beverages in the intervention communities by working in large and small retail food stores within each community. Intervention strategies included providing stocking sheets and working with store managers to stock healthier options, point of purchase promotions (shelf labels, posters) and educational interactive sessions (including taste tests) for customers.

Worksite component

The worksite component sought to increase opportunities for physical activity and healthier dietary choices among working NA adults. Five of the largest worksites in each community were selected (typically, tribal government offices, casinos, schools). Intervention activities in worksites included a multiphase team pedometer challenge, coffee/water station makeover and posting of educational materials. The emphasis on PA was increased in this component based on the OPREVENT1 experience.

School component

The school component supported children to become change agents in their homes to improve healthy eating and physical activity behaviors for adults in their households. Teachers were trained to deliver separate curricula for grades 2–6 (16–20 lessons per grade), including culturally appropriate stories, in-class activities and take-home activities. The school program was intended to be conducted in one full academic year, with flexibility given to teachers in terms of when to teach it. Teachers could opt to teach 1–2 lessons/week, or less frequently, but on their own schedule—a lesson learned from OPREVENT1.

Social media/mailing component

We sought to reinforce key messages delivered in the different intervention components, and increase awareness of OPREVENT2 activities in their communities via a social media and mailing component of the intervention. Regular posts were made on the ‘OPREVENT’ Facebook and Instagram accounts, which were intended to engage with community members, with content such as recipes and notification of intervention and other community activities. A Twitter account aimed to reach a more general audience of policymakers and others more interested in NA issues. Targeted mailings of selected intervention materials were conducted for all households in the intervention evaluation sample (N = 300), 1–2 times per intervention phase.

Policy component

Called the Community Action Committee (CAC), a group of local stakeholders was organized to troubleshoot the OPREVENT2 intervention, determine strategies for sustainability, and develop initiatives (ideally, policy changes) to improve the food and physical activity environments in each intervention community. This component was specifically added based on the experience of the OPREVENT1 pilot.

Process evaluation

The OPREVENT2 process evaluation assessed reach, dose delivered and fidelity of each component [33]. The study team developed a priori implementation standards (Table II) based on previous experience with implementation of our other trials in NA communities [37, 40] and in Baltimore [38]. At the beginning of each phase (starting with Phase 2), research team members met to discuss progress, assess how well standards were being met, and adjust delivery of the intervention. Some adjustments were made to the intervention standards as delivery progressed, and the standards presented are the final set (Table II).

Table II.

Description of sample OPREVENT2 high standards per component

| Intervention component | Sample reach (set standard) | Sample dose delivered (set standard) | Sample Fidelity (set standard) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food stores |

|

|

|

| Worksites |

|

|

|

| Schools | No. of schools participating per community (≥1) | No. of times interventionist visits school per week (≥1) | None |

| Social media |

|

|

|

| Community action committee |

|

|

No. of environmental changes in each community per quarter (≥1) |

The following definitions were used:

Reach: The number of individuals in the intended target audience who participated at any level in the intervention component. Reach was measured at the individual (e.g. store customer) and institutional (e.g. food store) levels.

Dose delivered: Number of units (e.g. number of posters, minutes) of each intervention component provided by OPREVENT2 interventionists.

Fidelity: Assessed intervention component implementation based on reactions to or level of engagement with a program component (e.g. # likes on a Facebook post, stocking of promoted foods in stores).

Process evaluation training and reporting

Due to the remote and rural nature of the six study communities, as well as limited resources, process evaluation data were primarily collected by the same NA field staff members who delivered the intervention. The initial certification for process data collection included 7–8 h of training, role-play and supervised practice. Additionally, booster trainings were held before each phase to trouble shoot problems experienced in the phase prior and train on the new phase-specific process evaluation components.

Instruments

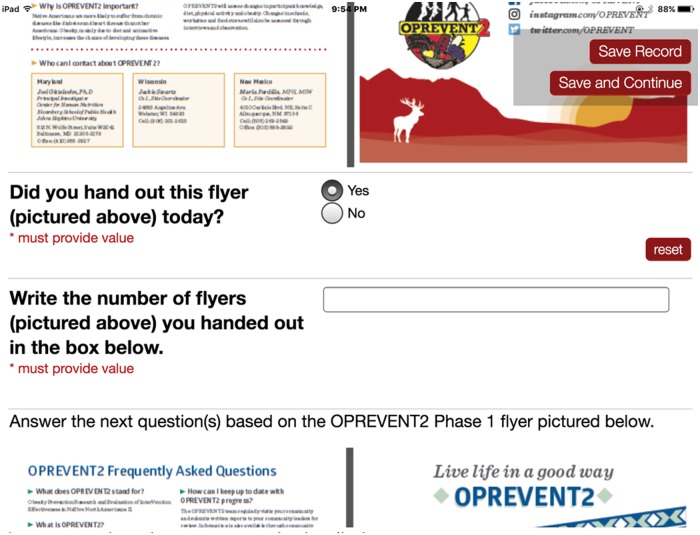

Interventionist visits: Process data were collected on iPads using RedCAP [49, 50]. An OPREVENT2 process evaluation virtual form was designed and updated at the beginning of each intervention phase, with materials for the new phase added. Each time an interventionist visited one of the intervention sites (e.g. food store, worksite, school) or conducted a CAC meeting, a phase and intervention site specific process form was completed to indicate what was performed during the visit. Each intervention item (e.g. poster, shelf label) had its own thumbnail graphic to aid in identification (Fig. 2). OPREVENT2 process evaluation data was encrypted, uploaded and stored on a secure central server.

Fig. 2.

Sample RedCAP process evaluation display screen.

Social media: Facebook, Instagram and Twitter process evaluation data were derived from online tracking platforms such as Facebook Insights, Iconosquare and Twitter Analytics by two social media interventionists on a weekly, monthly or phase basis depending on the specific standard under consideration. Data were recorded in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

Mailing data: Mailings were sent out of the main office at the university. Records were kept as to the number of mailings sent out, what was included in each mailing, and number of returns.

Score development/data analysis

Implementation scores were developed for each process evaluation construct (reach, dose delivered, fidelity), for each intervention component, by phase. Phase 1 was an introductory phase, and was never intended to entail a complete implementation of all intervention components. The means for phases 2–6 were used to calculate an overall score per intervention component. Overall study reach, dose delivered and fidelity were also determined. First, we identified the percentage met of each set standard by dividing the individual process measure by the set standard, and multiplying it by 100. Then, we averaged all the scores within each process evaluation construct, and classified them as high, medium or low in comparison to the set standard. High intervention delivery was defined as a process evaluation construct at ≥100% of the set standard, while medium was defined as 50–99.9%, and low as <50%. All process data were entered and analysed in Microsoft Excel. This analysis was based on methods developed in previous process evaluation research by the study team [38].

Results

Summary

Food stores, worksites, CAC and mailings had the highest levels of implementation quality, as these components achieved overall implementation scores of ≥100%. The social media and school components received an overall moderate level of implementation. No components achieved an overall low implementation score. Overall, study reach, dose delivered and fidelity achieved a high implementation level. Process evaluation results for reach, dose delivered and fidelity by phase separated by study component can be found in Figs 3–5, respectively. The school component is not included in these figures, due to challenges in timing with the phases for the rest of the OPREVENT2 intervention.

Fig. 3.

Average percent of the set standard met for all reach process evaluation data for each OPREVENT2 intervention component, by phase.

Fig. 4.

Average percent of the set standard met for all dose delivered process evaluation data for each OPREVENT2 intervention component, by phase.

Fig. 5.

Average percent of the set standard met for all fidelity process evaluation data for each OPREVENT2 intervention component, by phase.

Food stores

The food store component was implemented with high reach, dose delivered and fidelity throughout the intervention, and implementation scores generally increased over time.

Worksites

The worksite component was implemented with high reach and high dose delivered. Fidelity was medium.

Schools

Reach, dose delivery and fidelity of the school component were low to moderate. On average, 50% of the lessons were completed across participating grades, with grades 2–4 having the highest participation, with less grade 5 and 6 participation across schools in all communities.

Community action committees

The CAC reach and dose delivered were high throughout the OPREVENT2 intervention implementation. However, no fidelity measures were calculated for this component, which is addressed later in this paper.

Social media

The social media component was implemented with moderate to high dose delivered, but low reach and fidelity. Dose and reach scores declined as the intervention progressed.

Mailings

The mailings were implemented with high reach, dose delivered and fidelity overall. No mailings were sent for phase 6.

Discussion

This paper presents the first detailed process evaluation of all components of a MLMC obesity prevention trial in rural NA communities. We used our process evaluation to monitor and provide feedback to the research team on how well each component was being delivered, which allowed for improvements to program components; a strategy we have used successfully in other trials [38]. The CACs and social media/mailings were new additions to our work with NA communities [32].

A large challenge that affected all components of the OPREVENT2 intervention was a funding shortage that lasted four months (during phases 3 and 4). During that time, we had to lay off half of the field staff. In addition, phases 3 and 4 took place during winter months, with many activities cancelled due to dangerous weather conditions. The remaining staff did their best to deliver the intervention but we were short-handed and short on good weather. We extended the length of phases 3 and 4 to accommodate staffing levels, but there was still a lack of team member presence in the communities at that time. Reach, dose and fidelity were calculated by phase—so extending the length of each phase allowed us to reach our standards, but meant fewer opportunities for engagement with community members on a weekly or monthly basis.

Food stores

The study intervention team had substantial previous experience implementing food stores intervention in NA communities [37, 51]. We found that regular engagement with store owners/managers was crucial. Challenges existed in one setting where a small food store owner was planning to sell the business, and limited involvement of our project within the store itself. Our study team were flexible, and conducted interactive sessions outside the store entrance, in a nearby laundromat and at community meetings. In another setting, there were >15 retail food stores, and we had to focus our resources on just five that were reported as the most commonly used by our evaluation sample. Staffing shortages meant that while delivery standards were met, planned biweekly visits did not occur with the same frequency, and relationships deteriorated. In some stores, our posters and shelf labels were taken down. Fidelity of food stores remained well over the high-standard, even during phases 3 and 4, indicating that store owners were still able to stock promoted food items.

Worksites

The study team had also conducted substantial intervention activities in worksites, supporting the overall strong implementation of this component observed [32]. The coffee station make-over was well-implemented, and well-received—but was not maintained in about half the worksite after the team’s contributions were completed. Despite an emphasis on physical activity in this component for a longer duration, engagement in this component decreased over time. This was mainly due to decreasing interest and participation in the pedometer challenge activities, a trend that has been observed in other pedometer interventions [52], but also due to staff shortages. A small cadre of avid walkers in each community maintained their walking programs under the JUST MOVE IT© program [53].

School curriculum

This component of the OPREVENT2 program proved the most challenging to implement due to logistical constraints, overextended teacher schedules and job duties, diminishing returns of take-home activities, competing priorities and limited time and resources. For instance, in one Midwestern community, one of the two elementary schools that agreed to participate never initiated the program, while, in the other school, the program was implemented in grades 2–4 only. While both Southwestern community schools initiated the school program, one teacher had to discontinue the curriculum due to personal reasons in one school, which led to a lower participation rate. Additionally, several of the Southwestern schools received poor ‘grades’ from the state, and had to focus all of their resources on the three R’s. This meant that few teachers completed the process evaluation forms and made tracking of this component difficult. Of those that did implement the school component, some teachers stated that they enjoyed teaching and students enjoyed participating in the school curriculum. Yet, others mentioned time constraints that prevented them from completing the lessons, and noted students and their families’ loss of interest in take-home activities. Additionally, staff were not able to follow-up with the teachers in each school on a monthly basis, as planned. In the end, a detailed implementation assessment was conducted at the end of the school year only. These findings have implications for future programs, including the need to provide guidance on how to adapt the school curriculum to a particular community setting (e.g. potentially as an afterschool program) and active monitoring by team staff.

CAC

The CAC policy component was successfully implemented with overall high reach and dose delivered. However, CAC also proved challenging to implement. In the beginning, the field team struggled with low and inconsistent participation, and challenges with representation. In the end, in one setting, very high reach was obtained by tying the CAC meetings to regular community meetings, but this provided little time for discussion and action—thus, reach was maximized at the cost of dose delivered. Achieving enactment of policies and environmental changes (an indicator of fidelity) was not feasible in the one-year timeframe of the CAC without consistent involvement of community stakeholders, given the sovereignty of NA communities and the need to not disrupt the rest of the OPREVENT2 intervention. Due to the readiness of community members, the CAC meetings focused mainly on discussions about the importance of promoting healthy environments and discussing promising strategies for promoting healthy food and physical activity environments. The study team felt they were never able to establish CACs that developed environmental changes as a coalition, as originally envisioned. Due in part to ongoing changes in CAC participants, the purpose of the CAC was continually re-discussed. Promoting sustainability of programs is a challenge in NA communities, and future research should focus on building and supporting community champions, and other strategies [54].

Social media

The inclusion of a social media component was also new for our research team. Our formative research had indicated that increasing numbers of NA community members used social media (especially Facebook) regularly, and our experience using social media to promote an urban food environment intervention had been successful [40]. However, we found our OPREVENT2 social media accounts generated little involvement and few responses from community members. The social media accounts were intended to support ongoing research activities and highlight the accomplishments of community members. However, community members did not commonly comment on and/or follow our accounts. In addition, field staff raised concerns about putting photos of community members on social media accounts, which meant that social media posts were not always personalized to the target audience. This may have reduced reach and fidelity. Finally, the managers of the social media were based at the main study office in Baltimore, and not in the field interacting with community members. This meant that there were less opportunities for photos to be taken, a lag time between when photos that were taken and when they would be sent to us to be posted on social media, and less in-person promotion of our social media accounts with our target audience. Lack of networking on social media with target audience could also be another reason. It was difficult to figure out who on social media were our target NA community members and therefore hard to network/interact with them via our social media accounts.

Mailings

Implementation of targeted mailings was high overall, with a lapse in the final phase due to staff turnover at JHSPH. Mailings were also a new approach, and were intended to ensure that our evaluation sample in the intervention communities were exposed to visual materials. This approach has been successful in other trials with Native communities [51]. Community members who received the mailings expressed appreciation to our field staff.

Challenges with implementation of MLMC interventions

The study team experienced many challenges in the implementation of this complex MLMC intervention. In addition to the specific circumstances related to each component and described above, challenges existed in terms of the great distances involved, bad weather conditions, and staffing shortages which limited field time.

We can view the variation in implementation in two contrasting ways. First, where we failed to meet the high standards for any component, this could be considered a failure. On the other hand, when a particular component did not meet implementation standards, this was often a sign of particular circumstances in a community. The study team struggled at times with the concept of pushing our external implementation standards on communities. This then could also be viewed as a successful implementation because it was adapted to local circumstances. Future research is needed to determine the best strategies to balance flexibility with implementation standards.

Given the intensity of implementation for the various OPREVENT2 intervention components described, what can we conclude? Despite the many challenges experienced, based on relatively high reach, dose and fidelity overall, the study team feels this was a relatively strong and ‘fair’ implementation of the program. Study impacts (or lack thereof) can be associated with the overall intervention. Many components of the OPREVENT2 intervention have been tried and tested by our team and others previously (e.g. food store, school and worksite components). On the other hand, other components of the intervention were new to our team (CAC, social media, mailings), and potentially could be delivered better in a future trial. The use of standards for implementation is crucial both for the monitoring and ongoing improvement of MLMC intervention trials, and also for planning future trials that use these intervention strategies.

A further challenge faced by the team was the use of RedCAP on iPads in rural communities. Due to the lack of WiFi in rural communities, consistent uploading of data was challenging, but ultimately all data were received. Ultimately, using the electronic data collection saved time and costs, but when working in communities with limited WiFi access, special considerations will need to be made.

Limitations

The OPREVENT2 trial implementation had several limitations. Much of the work that is needed to maintain positive relationships with communities are difficult to capture as part of process evaluation, yet can have a large impact on the success of interventions. We found some settings within communities (such as schools) were not always ready for specific intervention components. This context needs to be documented and communicated to other investigators to enhance transferability. Cost-effectiveness was not studied due to limited resources; but this is an important aspect of whether an intervention can be sustained. We worked with each intervention community to build sustainability. For example, we helped communities identify members who would help take over the maintenance of point-of-purchase promotions like posters and shelf labels, as well as individuals to co-lead CAC meetings. Sustainability is a strong focus of the OPREVENT2 intervention in round 2 (delayed intervention) communities. Future research should more closely include cost-effectiveness of such interventions to understand the resources are needed to achieve particular outcomes, and to enhance sustainability.

Conclusions

OPREVENT2 is one of few studies to report on the process evaluation of a complex multilevel intervention to reduce obesity in Native communities. Our findings reinforce the importance of using process evaluation to provide ongoing monitoring and feedback to the intervention team. Conducting a detailed process evaluation required our team to develop and use standards to help assess how well specific components are being implemented, and to target areas of improvement. Ongoing attention to program implementation undoubtedly led to a better implementation for the overall program, and to many lessons learned.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank tribal authorities, health staff, school administration and staff and food store owners and managers in the six tribal communities in Wisconsin and New Mexico for their participation in this intervention trial.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL122150 to J.G.).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States. With Special Feature on Socioeconomic Status and Health. Hyattsville, 2012. [PubMed]

- 2. Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Peregoy JA. . Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2011. Vital Health Stat. 2012. [PubMed]

- 3. Singh GK, Siahpush M, Hiatt RA. et al. Dramatic increases in obesity and overweight prevalence and body mass index among ethnic-immigrant and social class groups in the United States, 1976–2008. J Community Health 2011; 36: 94–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yu CH, Zinman B.. Type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in aboriginal populations: a global perspective. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007; 78: 159–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barnes PM, Adams PF, Powell-Griner E. . Health Characteristics of the American Indian or Alaska Native Adult Population: United States, 2004–2008 Hyattsville: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010, 1–23. [PubMed]

- 6. Harris R, Nelson LA, Muller C. et al. Stroke in American Indians and Alaska Natives: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015; 105: e16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jacobs-Wingo JL, Espey DK, Groom AV. et al. Causes and disparities in death rates among urban American Indian and Alaska Native Populations, 1999–2009. Am J Public Health 2016; 106: 906–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. 2014. Available at: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. Accessed: 5 September 2019.

- 9. Gittelsohn J, Rowan M.. Preventing diabetes and obesity in American Indian communities: the potential of environmental interventions. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 93: 1179S–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kumar G, Jim-Martin S, Piltch E. et al. Healthful nutrition of foods in Navajo Nation stores: availability and pricing. Am J Health Promot 2016; 30: 501–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee T. 7 foods that cost more on the rez, and one junk food that costs less. Indian County Media Network. 2016. Available at: https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/culture/health-wellness/7-foods-that-cost-more-on-the-rez-and-one-junk-foodthat-costs-less/. Accessed: 5 September 2019.

- 12.Does the Built Environment Influence Physical Activity? Washington, D.C. 2005. Available at: http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/sr/sr282.pdf. Accessed: 5 September 2019.

- 13. Foulds HJ1, Warburton DE, Bredin SS.. A systematic review of physical activity levels in Native American populations in Canada and the United States in the last 50 years. Obes Rev 2013; 14: 593–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yurgalevitch SM, Kriska AM, Welty TK. et al. Physical activity and lipids and lipoproteins in American Indians ages 45–74. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998; 30: 543–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ho L, Gittelsohn J, Sharma S. et al. Food-related behavior, physical activity, and dietary intake in First Nations– a population at high risk for diabetes. Ethn Health 2008; 13: 335–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Hollis-Neely T. et al. Fruit and vegetable intake in African Americans income and store characteristics. Am J Prev Med 2005; 29: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharma S, Cao X, Arcan C. et al. Assessment of dietary intake in an inner-city African American population and development of a quantitative food frequency questionnaire to highlight foods and nutrients for a nutritional invention. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2009; 60: 155–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gittelsohn J, Kumar M.. Preventing childhood obesity and diabetes: is it time to move out of the school? Diabetes 2007; 76: 485–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gittelsohn J, Park S.. School and Community-Based Interventions In: Freemark M. (ed). Pediatr Obes Etiol Pathog Treat. New York, NY: Humana Press, 2010, 315–36. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Economos C, Hyatt R, Goldberg J. et al. A community-based environmental change intervention reduces BMI z-scores in children: shape up Somerville first year results. Prev Med 2004; 2: S108–36. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sallis J, Cervero R, Ascher W. et al. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu Rev Public Health 2006; 27: 297–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives. Dev Psychol 1986; 22: 723–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ewart-Pierce E, Mejía Ruiz MJ, Gittelsohn J.. “Whole-of-Community” obesity prevention: a review of challenges and opportunities in multilevel, multicomponent interventions. Curr Obes Rep 2016; 5: 361–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morland K, Diez Roux AV, Wing S.. Supermarkets, other food stores, and obesity: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Prev Med 2006; 30: 333–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Powell LM, Auld MC, Chaloupka FJ. et al. Associations between access to food stores and adolescent body mass index. Am J Prev Med 2007; 33: S301–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gibson DM. The neighborhood food environment and adult weight status: estimates from longitudinal data. Am J Public Health 2011; 101: 71–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Powell LM, Slater S, Mirtcheva D. et al. Food store availability and neighborhood characteristics in the United States. Prev Med (Baltim) 2007; 44: 189–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Franco M, Diez Roux AV, Glass TA. et al. Neighborhood characteristics and availability of healthy foods in Baltimore. Am J Prev Med 2008; 35: 561–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Steinberger J, Daniels SR.. Obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in children: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the atherosclerosis, hypertension, and obesity in the Young Committee (Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young) and Circulation 2003; 107: 1448–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Israel BA. et al. Fruit and vegetable access differs by community racial composition and socioeconomic position in Detroit, Michigan. Ethn Dis 2006; 16: 275–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Daroszewski EB. Dietary fat consumption, readiness to change, and ethnocultural association in midlife African American women. J Community Health Nurs 2004; 21: 63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Redmond LC, Jock B, Gadhoke P. et al. OPREVENT (Obesity Prevention and Evaluation of InterVention Effectiveness in NaTive North Americans): design of a multilevel, multicomponent obesity intervention for native American adults and households. Curr Dev Nutr 2019; 3: 81–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Steckler AB, Linnan L.. Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Folta SC, Kuder JF, Goldberg JP. et al. Changes in diet and physical activity resulting from the shape up Somerville community intervention. BMC Pediatr 2013; 13: 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gittelsohn J, Dennisuk LA, Christiansen K. et al. Development and implementation of Baltimore Healthy Eating Zones: a youth-targeted intervention to improve the urban food environment. Health Educ Res 2013; 28: 732–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Joseph S, Stevens AM, Ledoux T. et al. Rationale, design, and methods for process evaluation in the childhood obesity research demonstration project. J Nutr Educ Behav 2015; 47: 560–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rosecrans AM, Gittelsohn J, Ho LS. et al. Process evaluation of a multi-institutional community-based program for diabetes prevention among First Nations. Health Educ Res 2007; 23: 272–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ruggiero CF, Poirier L, Trude ACB. et al. Implementation of B’More Healthy Communities for Kids: process evaluation of a multi-level, multi-component obesity prevention intervention. Health Educ Res 2018; 33: 458–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee SH, Goedkoop S, Yong R. et al. Development and implementation of the Baltimore Healthy Carry-outs Feasibility Trial: process evaluation results. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Curran S, Gittelsohn J, Anliker J. et al. Process evaluation of a store-based environmental obesity intervention on two American Indian Reservations. Health Educ Res 2005; 20: 719–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Loh H, Schwendler T, Trude ACB. et al. Implementation of social media strategies within a multi-level childhood obesity prevention intervention: process Evaluation Results. Inquiry 2018; 55:004695801877918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977; 84: 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kremers SP, de Bruijn GJ, Visscher TLS. et al. Environmental influences on energy balance-related behaviors: a dual-process view. Int. J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2006; 3: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rimal RN, Real K.. Perceived risk and efficacy beliefs as motivators of change: use of the risk perception attitude (RPA) framework to understand health behaviors. Hum. Commun. Res 2003; 29: 370–99. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rimal RN. Perceived risk and self-efficacy as motivators: understanding individuals’ long-term use of health information. J Commun 2001; 51: 633–54. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stokols D. Establishing and maintaining healthy environments. Toward a social ecology of health promotion. Am Psychol 1992; 47: 6–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A. et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1988; 15: 351–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gittelsohn J, Jock B, Redmond L. et al. OPREVENT2: design of a multi-institutional intervention for obesity control and prevention for American Indian adults. BMC Public Health 2017; 17: 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R. et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42: 377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL. et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software partners. J Biomed Inform 2019; 95: 103208.[Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gittelsohn J, Kim EM, He S. et al. A food-store based environmental intervention is associated with reduced BMI and improved psychosocial factors and food-related behaviors on the Navajo Nation. J Nutr 2013; 143: 1494–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cai X, Qiu SH, Yin H. et al. Pedometer intervention and weight loss in overweight and obese adults with Type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med 2016; 33: 1035–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Healthy Native Communities Partnership. JUST MOVE IT. Available at: http://hncpartners.org/just-move-it.html. Accessed: 29 April 2020.

- 54. Fleischhacker S, Byrd R, Hertel AL.. Advancing native health in North Carolina through tribally led community changes. NC Med J 2014; 75: 409–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]