Abstract

A new SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) belonging to the genus Betacoronavirus has caused a pandemic known as COVID-19. Among coronaviruses, the main protease (Mpro) is an essential drug target which, along with papain-like proteases catalyzes the processing of polyproteins translated from viral RNA and recognizes specific cleavage sites. There are no human proteases with similar cleavage specificity and therefore, inhibitors are highly likely to be nontoxic. Therefore, targeting the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro enzyme with small molecules can block viral replication. The present study is aimed at the identification of promising lead molecules for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro enzyme through virtual screening of antiviral compounds from plants. The binding affinity of selected small drug-like molecules to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro were studied using molecular docking. Bonducellpin D was identified as the best lead molecule which shows higher binding affinity (−9.28 kcal/mol) as compared to the control (−8.24 kcal/mol). The molecular binding was stabilized through four hydrogen bonds with Glu166 and Thr190 as well as hydrophobic interactions via eight residues. The SARS-CoV-2 Mpro shows identities of 96.08% and 50.65% to that of SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro respectively at the sequence level. At the structural level, the root mean square deviation (RMSD) between SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and SARS-CoV Mpro was found to be 0.517 Å and 0.817 Å between SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro. Bonducellpin D exhibited broad-spectrum inhibition potential against SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro and therefore is a promising drug candidate, which needs further validations through in vitro and in vivo studies.

Abbreviations: ACE-2, Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2; BLAST, Basic Local Alignment Search; cLogP, partition coefficient between N-octanol and water; HBA, hydrogen bond acceptor; HBD, hydrogen bond donor; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus; Mpro, main protease; MW, molecular weight; PDB, Protein Data Bank; RMSD, root mean square deviation; ROF, rule of five; SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

Keywords: Molecular docking, Antiviral properties, Phytochemicals, Medicinal plants, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Binding affinity, SARS-CoV-2 Mpro

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are positive-sense RNA enveloped viruses which derive their name from the crown-like spikes on their surface and they belong to Coronaviridae family. They are classified into four main subgroups- alpha, beta, gamma, and delta depending on their genomic structure [1]. Alpha- and beta coronaviruses cause respiratory infections in humans and gastroenteritis in other mammals [2,3]. Until the last year, only six different coronaviruses causing infection in humans were known. Four of this (HCoV-NL63, HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43 and HKU1) cause mild common cold-type symptoms in healthy individuals and the other two which caused epidemics in the last two decades. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) caused a SARS epidemic in 2002–2003 with a 10% mortality rate. Likewise, the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) caused a disastrous pandemic in 2012 leading to 37% mortality [1]. All coronaviruses infecting humans usually known to have intermediate hosts such as bats or rodents [4]. Previous outbreaks of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV involved civet cats and dromedary camels for their direct transmission to humans [1]. A new coronavirus caused an outbreak of the pulmonary disease in Wuhan (the capital of Hubei province in China) in December 2019 and has since spread across different parts of the world [5,6]. Since its RNA genome shows about 82% identity to that of the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV), the new virus has been termed as SARS-CoV-2 [7]. However, both these viruses belong to the same clade of the genus Betacoronavirus [5,6]. The SARS-CoV-2 caused a disease known as COVID-19. At the initial outbreak, cases were linked to the Huanan seafood and animal market in Wuhan but active human-to-human transmission caused exponential growth in the number of reported cases. The World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed the outbreak a pandemic on March 11, 2020. There have been >170,000 cumulative cases worldwide accounting for approximately 3.7% case-fatality rate as of March 15, 2020 [8].

Due to the close similarity to SARS-CoV, the biochemical interactions and the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 are highly likely to be similar [1]. The virus entry into the host cell is mainly mediated through the binding of the SARS spike (S) protein to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor on the cell surface [9]. Among coronaviruses, the main protease (Mpro, also called 3CLpro) has emerged as the best-described drug target [10]. The polyproteins that are translated from the viral RNA are processed by this enzyme together with the papain-like protease(s) [11]. The Mpro recognizes and acts remarkably on eleven cleavage sites typically Leu-Gln↓(Ser,Ala,Gly) on the large polyprotein 1ab (replicase 1ab) of approximately 790 kDa. Blocking the activity of this enzyme would help in inhibiting viral replication. There are no reported human proteases with a similar cleavage specificity and therefore, inhibitors against this enzyme are less probable to be toxic [8]. The three dimensional X-ray crystal structure of this enzyme in complex with α-ketoamide inhibitor 13b (O6K) was recently solved by Zhang et al. [8] (PDB ID: 6Y2F) which offers an opportunity for structure-based drug design against the enzyme target. Understanding the relevance of the steady rise in the number of infected and death cases in recent time from COVID-19 and lack of effective therapeutic interventions such as drugs and vaccines, computer-aided drug design is an important strategy to be sought after. This rational based drug design will reduce the cost and time incurred in the drug discovery process. Structure-based drug design primarily relies on molecular docking to identify lead molecules against the target proteins from chemical libraries [12,13]. Compared to the synthetic inhibitors plant based-drugs have less toxicity and much safer to use. The natural products such as traditional medicines and plant-derived compounds (phytochemicals) are the rich sources of promising antiviral drugs [14]. Around 44% of the approved antiviral drugs between 1981 and 2006 were derived from natural products [15]. The plant extracts have been extensively used and screened for drug molecules to evaluate theirs in vitro antiviral activities. Few examples of medicinal plants with proven antiviral activities include Phyllanthus amarus Schum. and Thonn which blocks human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) replication both in vitro and in vivo [16]; Azadirachta indica Juss. (Neem) shows in vitro and in vivo inhibition properties against Dengue virus type-2 (DENV-2) [17]; Geranium sanguineum L. significantly inhibits the replication of Herpes simplex virus type-1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) in vitro [18]; Acacia nilotica L. possesses activity against Hepatitis C virus (HCV) in vitro etc. [19].

In the present study, we have screened small drug-like molecules from a dataset of phytochemicals possessing antiviral activities using drug-like filters and toxicity studies. The selected molecules were evaluated for their binding affinity to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro enzyme using molecular docking. The sequences and structures of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro were compared with SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro. The identified lead molecules were further examined for their broad-spectrum inhibition potential against SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Ligand preparation

The information about a set of thirty-eight phytochemicals from medicinal plants with antiviral activities was retrieved through literature search [14]. The summary of the selected phytochemicals (class, plant source and antiviral activity) is provided in Suppl. Table 1. The two-dimensional structures of the phytochemicals were generated using Chemsketch and modelled into 3D using open Babel and the structure optimization was carried out with an MMFF94 force field [20] using our previously defined protocol [21]. These optimized structures were used for virtual screening. A set of twelve FDA approved antiviral drugs such as Raltegravir (CID54671008), Dolutegravir (CID54726191), Nelfinavir (CID64143), Lopinavir (CID92727), Zidovudine (CID35370), Nevirapine (CID4463), Simeprevir (24873435), Boceprevir (CID10324367), Zanamivir (CID60855), Oseltamivir (CID65028), Acyclovir (CID135398513) and Ganciclovir (CID135398740) were retrieved from PubChem database [22].

2.2. Screening of small drug-like molecules

The phytochemicals were screened based on physicochemical properties obeying Lipinski's rule of five (ROF) filters [23] and further tested for in silico toxicity studies such as mutagenicity, tumorigenicity, reproductive effects and irritancy. The physicochemical properties of the phytochemicals were determined using DataWarrior program version 4.6.1 [24].

2.3. Receptor preparation

The three-dimensional structures of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro were retrieved from Protein Data Bank (PDB) (http://www.rcsb.org/) using PDB IDs:6Y2F, 3TNT and 5WKK at a resolution of 1.95 Å, 1.59 Å and 1.55 Å respectively. The receptors were prepared for molecular docking using our previously defined protocol [25]. The binding sites were defined by choosing grid boxes of suitable dimensions around the bound co-crystal ligand. The grid box dimensions for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro are represented in Table 1 .

Table 1.

The grid box dimensions selected for molecular docking studies.

| Target enzyme | Grid box dimension |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of grid points (npts) | Center (xyz coordinates) | Grid point spacing (Å) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro | 60 × 60 × 60 | 11.476, −1.396. 21.127 | 0.375 |

| SARS-CoV Mpro | 65 × 65 × 65 | 22.803, 40.132, −10.620 | 0.375 |

| MERS-CoV Mpro | 65 × 65 × 65 | −16.001, 25.308, 10.579 | 0.375 |

2.4. Determination of sequence percentage identity, multiple sequence alignment and pairwise structural clustering

The sequence percentage identity of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro to SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro was determined using a standard protein Basic Local Alignment Search (BLASTp) tool (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE=Proteins). Multiple sequence alignment of the three sequences were performed using CLUSTAL W algorithm [26]. Pairwise structural clustering of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro was analyzed using UCSF Chimera tool [27].

2.5. Validation of docking method

To check the suitability of molecular docking parameters and algorithm to reproduce the native binding poses, a redocking experiment was performed using the co-crystal compound.

2.6. Molecular docking

Molecular docking was executed using AutoDock4.2 software [28]. Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm was used for performing molecular docking studies and the docking parameters were chosen from our previously defined protocol [21]. A total number of fifty independent docking runs were performed for each compound. The conformational clustering of the poses was performed by considering a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of <2.0 Å. The most favourable binding poses of the compounds were analyzed by choosing the lowest free energy of binding (ΔG) and the lowest inhibition constant (Ki) which is calculated using the following equation (Eq. (1)):

| (1) |

where ∆G is the binding energy in kcal/mol, R is the universal gas constant (1.987 calK−1 mol−1) and T is the temperature (298.15 K).

A stable complex is formed between a protein and ligand which exhibits more negative free energy of binding and low Ki indicates high potency of an inhibitor [29,30]. The hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions between the compounds and the target enzymes were studied using LigPlot+ v 1.4.5 [31].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Selection of phytochemicals for the study

A total of 38 bioactive phytochemicals possessing antiviral activities were selected for the study. These compounds were chosen based on the previous reports of their potent antiviral effects against various pathogenic viruses such as adenovirus, influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, human cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, poliovirus, varicella-zoster virus etc. (Suppl. Table 1). The compound set consists of different classes of phytochemicals including active flavonoids (N = 14), active organic acids (N = 5), active alkaloids (N = 5), active essential oils (N = 3), active stilbenes (N = 6) and other phytoconstituents (N = 5). The three-dimensional structures the compounds were modelled and optimized. A list of these phytochemicals is enumerated in Table 2 . These optimized structures were used further for virtual screening and molecular docking studies.

Table 2.

List of phytochemicals selected for virtual screening.

| Class | Phytochemicals | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | Cmpd1 | (+)-Catechin |

| Cmpd2 | (−)-Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) | |

| Cmpd3 | (−)-Epicatechin gallate (ECG) | |

| Cmpd4 | (−)-Epigallocatechin (EGC) | |

| Cmpd5 | Rutin | |

| Cmpd6 | 5,7-dimethoxyflavaN-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | |

| Cmpd7 | 5,7,3′-trihydroxy-flavaN-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | |

| Cmpd8 | Genistein | |

| Cmpd9 | Baicalein | |

| Cmpd10 | Orientin | |

| Cmpd11 | Vitexin | |

| Cmpd12 | Chrysosplenol C | |

| Cmpd13 | Quercetin 3-rhamnoside (Q3R) | |

| Cmpd14 | Luteoforol | |

| Organic acids | Cmpd15 | 3,4-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid |

| Cmpd16 | 3,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid | |

| Cmpd17 | Raoulic acid | |

| Cmpd18 | Caffeic acid | |

| Cmpd19 | Chlorogenic acid | |

| Alkaloids | Cmpd20 | Naphthoindozidine alkaloid |

| Cmpd21 | 7-demethoxytylophorine | |

| Cmpd22 | 7-demethoxytylophorine N-oxide | |

| Cmpd23 | Sophoridine | |

| Cmpd24 | Lycorine | |

| Essential oils | Cmpd25 | Himachalol |

| Cmpd26 | α-himachalene | |

| Cmpd27 | β-himachalene | |

| Stilbenes | Cmpd28 | Resveratrol |

| Cmpd29 | Balanocarpol | |

| Cmpd30 | Shegansu B | |

| Cmpd31 | Gnetupendin B | |

| Cmpd32 | Gnetin D | |

| Cmpd33 | Isorhapontigenin | |

| Others | Cmpd34 | Caesalmin B |

| Cmpd35 | Bonducellpin D | |

| Cmpd36 | Chrysophanic acid (1,8-dihydroxy-3-methylanthraquiN) | |

| Cmpd37 | Emodin | |

| Cmpd38 | Hippomanin A |

3.2. Screening of small drug-like molecules

From a total of 38 phytochemicals, 10 compounds (four active flavonoids, two active alkaloids, two active essential oils and two other phytoconstituents) were found to be orally bioactive with respect to ROF criterion (Molecular weight (MW) ≤500, cLogP (partition coefficient between n-octanol and water) ≤5, number of hydrogen bond donors (HBD) ≤5 and number of hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) ≤10 [23]) without any significant toxicity issues such as being non-mutagenic, non-tumourigenic, non-irritant and no adverse effects on reproductive health (Table 3 ). These drug-like compounds were further taken for molecular docking studies. The drug-attrition rate in preclinical and clinical trials is quite high due to the poor pharmacokinetic studies [25] and therefore initial screening of these drug-like molecules can increase the chances of passing through the clinics.

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties of the compounds (asterisk indicates the compounds which passed the toxicity studies). a: Molecular weight, b: Partition coefficient between n-octanol and water, c: Hydrogen bond acceptor, d: Hydrogen bond donor, N: None, H: High, L: Low.

| Compounds | MWa (Da) | clogPb | HBAc | HBDd | Mutagenic | Tumourigenic | Reproductive effective | Irritant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd1* | 290.270 | 1.5087 | 6 | 5 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd2 | 458.374 | 2.0543 | 11 | 8 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd3 | 442.375 | 2.4 | 10 | 7 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd4 | 306.269 | 1.163 | 7 | 6 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd5 | 610.519 | −1.2573 | 16 | 10 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd6* | 462.449 | 0.7178 | 10 | 4 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd7 | 450.395 | −0.1793 | 11 | 7 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd8 | 270.239 | 1.6272 | 5 | 3 | H | H | H | N |

| Cmpd9* | 270.239 | 2.3357 | 5 | 3 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd10 | 448.379 | −0.4237 | 11 | 8 | H | N | N | N |

| Cmpd11 | 432.380 | −0.078 | 10 | 7 | H | N | N | N |

| Cmpd12 | 360.317 | 2.1238 | 8 | 3 | H | N | N | N |

| Cmpd13 | 448.379 | 0.5798 | 11 | 7 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd14* | 290.270 | 1.6348 | 6 | 5 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd15 | 516.454 | 0.7977 | 12 | 7 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd16 | 516.454 | 0.7977 | 12 | 7 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd17 | 370.575 | 8.2146 | 2 | 1 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd18 | 180.159 | 0.7285 | 4 | 3 | H | H | H | N |

| Cmpd19 | 354.310 | −0.7685 | 9 | 6 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd20 | 353.460 | 3.5777 | 4 | 0 | N | H | N | H |

| Cmpd21 | 363.456 | 4.0868 | 4 | 0 | L | H | N | N |

| Cmpd22 | 379.455 | 3.1134 | 5 | 0 | L | H | N | N |

| Cmpd23* | 248.369 | 1.7074 | 3 | 0 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd24* | 287.314 | 1.2078 | 5 | 2 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd25* | 222.370 | 3.5349 | 1 | 1 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd26 | 204.356 | 4.3321 | 0 | 0 | N | N | N | L |

| Cmpd27* | 204.356 | 4.4247 | 0 | 0 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd28 | 228.246 | 2.8295 | 3 | 3 | H | N | H | N |

| Cmpd29 | 470.476 | 3.3075 | 7 | 6 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd30 | 514.528 | 4.6839 | 8 | 5 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd31 | 380.395 | 3.884 | 6 | 5 | N | N | H | N |

| Cmpd32 | 470.476 | 4.4782 | 7 | 6 | N | N | H | N |

| Cmpd33 | 258.272 | 2.7595 | 4 | 3 | N | N | H | N |

| Cmpd34* | 388.458 | 2.5856 | 6 | 1 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd35* | 404.457 | 1.7335 | 7 | 2 | N | N | N | N |

| Cmpd36 | 254.240 | 2.6859 | 4 | 2 | H | N | N | H |

| Cmpd37 | 270.239 | 2.3402 | 5 | 3 | H | H | H | H |

| Cmpd38 | 634.454 | 0.0527 | 18 | 11 | N | N | N | N |

| Control | 594.687 | 1.7119 | 12 | 4 | N | N | N | N |

3.3. Comparative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro at the sequence and structural level

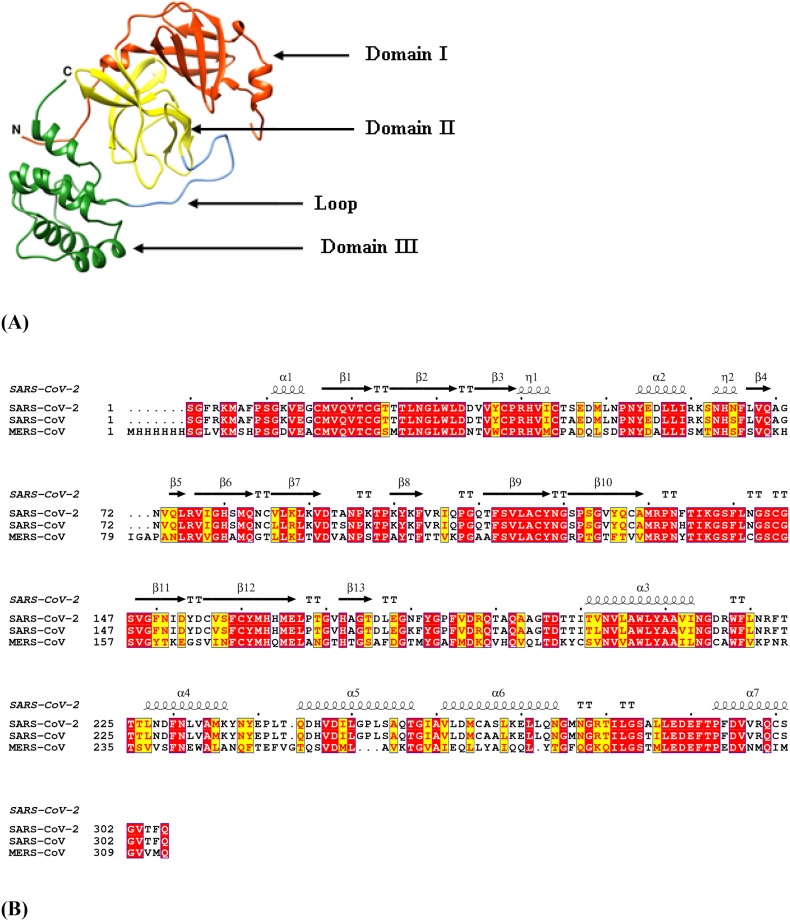

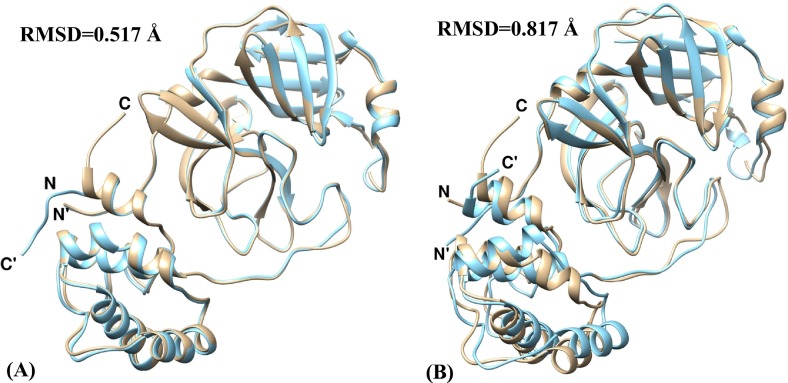

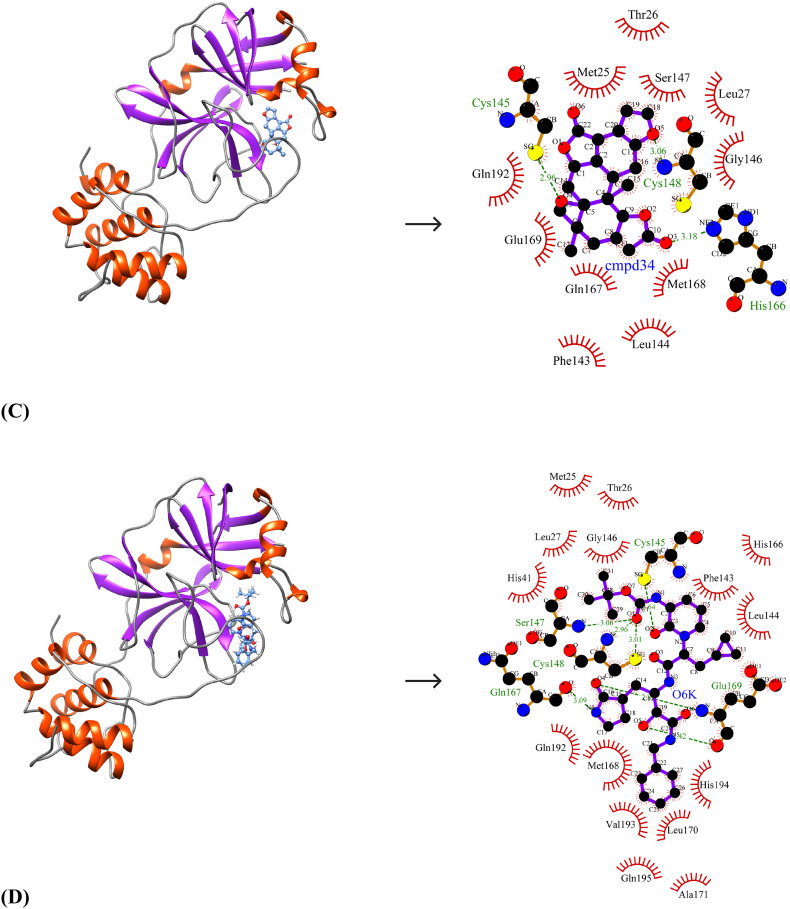

The primary sequences of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro was compared with that of SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro and it was found that SARS-CoV-2 Mpro shares identity percentages of 96.08 and 50.65 with that of SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro respectively (Table 4 ). The MSA results show the conservation of residues in the three domains-I (residues 1–99), II (residues 100–182) and III (residues 199–306) of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro enzyme which includes catalytic dyad residues His41-Cys145 located in a cleft between domains I and II along with canonical oxyanion hole residues Gly143, Ser144 and Cys145 (Fig. 1 ). Domains I and II have a typical chymotrypsin-like two-β-barrel fold. Domain III possesses a globular structure consisting of five α-helices which is connected to Domain II by a loop of residues 183–198 [32]. The pairwise structural imposition of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and SARS-CoV Mpro yields an RMSD value of 0.517 Å while an RMSD value of 0.817 Å was obtained when SARS-CoV-2 Mpro was superimposed on MERS-CoV Mpro (Fig. 2 ). This indicates that SARS-CoV-2 Mpro is structurally more close to SARS-CoV Mpro as compared to MERS-CoV Mpro. This comparative study at the sequence and structural level can be exploited for the design of broad-spectrum inhibitors which can block viral infection in host cells.

Table 4.

Standard Protein BLAST result using SARS-CoV-2 Mpro as a query sequence.

| Subject sequence | Maximum score | Total score | Query coverage | E value | Percent identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV Mpro | 623 | 623 | 100% | 0.0 | 96.08% |

| MERS-CoV Mpro | 322 | 322 | 100% | 1e−114 | 50.65% |

Fig. 1.

Sequence and structural analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. (A) three-dimensional structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro consists of three domains-I (orange-red), II (yellow) and III (forest green) where domain II and III are connected by a loop (cornflower blue), (B) Multiple Sequence alignment (MSA) of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro. The red box with white characters indicates strict identity whereas yellow box with red characters corresponds to semi-conserved residues. The secondary structure elements such as α-helices and 310-helices (η) are displayed as squiggles and β-strands and strict β-turns are rendered as arrows and TT letters respectively. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 2.

Structural clustering- (A) SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (tan) and SARS-CoV Mpro (cyan), (B) SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (tan) and MERS-CoV Mpro (cyan). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.4. Binding interaction studies of drug-like molecules with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro

The molecular docking protocol and algorithm was validated through the redocking experiment. The redocking result of co-crystal compound (6OK) shows an RMSD value of 3.603 Å between the docked and native co-crystal position. This small deviation indicates that the docking protocols and parameters used in the study can reliably estimate the biological conformations of the compounds [33].

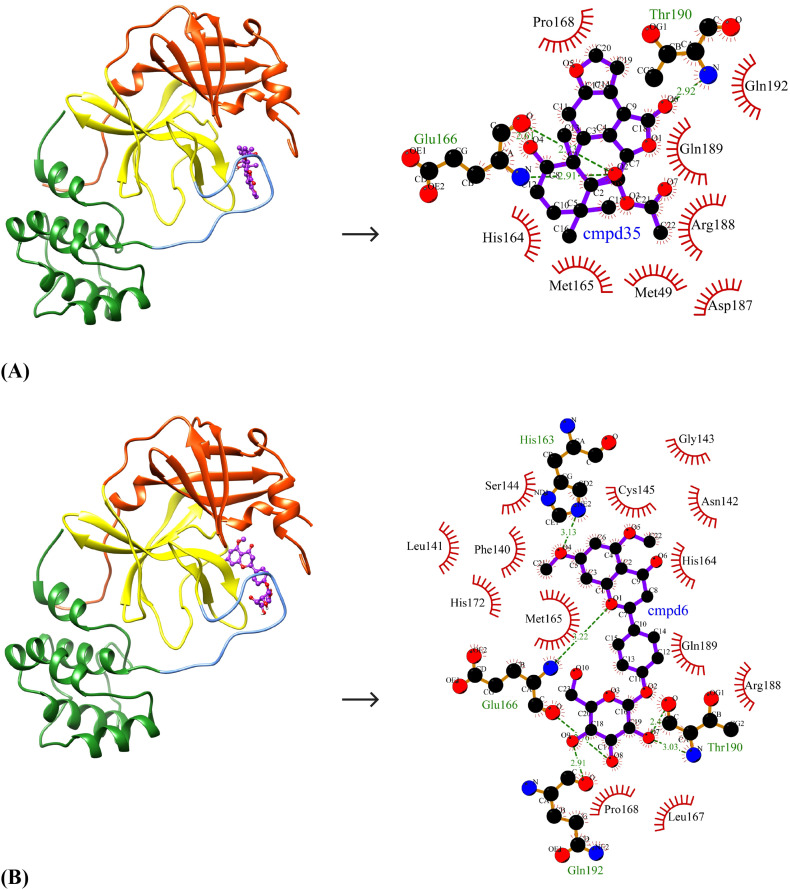

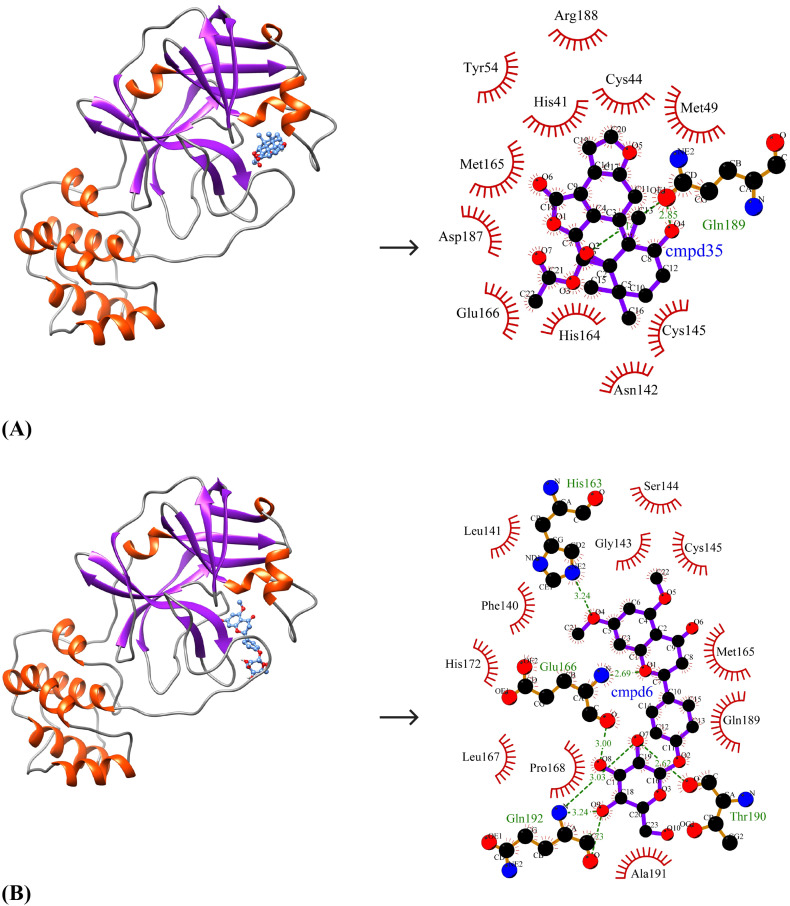

The ten selected drug-like small molecules were docked into the active site pocket of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. The molecular docking results are shown in Table 5 . The docking scores were bench-marked using the standard inhibitor, α-ketoamide 13 b (6OK). The α-ketoamide 13 b is a broad-spectrum inhibitor with an IC50 value of 0.67 ± 0.18 μM, 0.90 ± 0.29 μM and 0.58 ± 0.22 μM respectively against purified recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro [8]. On comparing the binding energies and inhibition constants with that of the standard inhibitor, we have shortlisted three lead molecules viz., Bonducellpin D, 5,7-dimethoxyflavanone-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside and Caesalmin B. Bonducellpin D and Caesalmin B are terpenoids isolated from the seeds of traditional Chinese medicinal plant Caesalpinia minax and exhibit in vitro inhibitory activities against Parainfluenza-3 (PI-3) virus. [34] The flavonoid 5,7-dimethoxyflavanone-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside has previously been reported to have antiviral activity against PI-3 [35]. The molecular interactions of LigPLot results are represented in Table 6 . The best-ranked lead molecule i.e., Bonducellpin D interacts with the enzyme target with a binding energy of −9.28 kcal/mol and inhibition constant of 156.75 nM. Bonducellpin D establishes four hydrogen bonds with residues Glu166 and Thr190 and hydrophobic interactions via eight residues (Met49, His164, Met165, Pro168, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189 and Gln192) (Fig. 3A). The second lead molecule i.e., 5,7-dimethoxyflavanone-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside interacts with the target enzyme with a binding energy of −9.23 kcal/mol and inhibition constant of 170.31 nM. This interaction is strengthed by the establishment of five hydrogen bonds with residues Glu166, Thr190 and Gln192 and with the involvement of thirteen residues (Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His164, Met165, Leu167, Pro168, His172, Arg188 and Gln189) contributing to hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 3B). The third lead molecule- Caesalmin B interacts with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with a binding energy of −8.82 kcal/mol and inhibition constant of 342.79 nM. The molecular interaction is facilitated through four hydrogen bonds with residues Glu166, Thr190 and Gln192 and hydrophobic interactions via ten residues (His41, Met49, Tyr54, Cys145, His164, Met165, Leu167, Asp187, Arg188 and Glu189) (Fig. 3C). The standard inhibitor interacts with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with a binding energy of −8.24 kcal/mol and inhibition constant of 905.88 nM. The binding interaction is mediated through four hydrogen bonds with residues Asn142, Cys145 and Glu166, and hydrophobic interactions via fourteen residues (Thr26, His41, Phe140, Leu141, Gly143, Ser144, His163, His164, Met165, Pro168, Asp187, Gln189, Thr190 and Gln192) (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, the residues His41 and Cys145 which form catalytic dyad residues are also found interacting with the inhibitor. Thus all the three lead molecules have better binding affinity to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro compared to the standard inhibitor.

Table 5.

Molecular docking result for selected compounds and control against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

| Compounds | Name | Structure | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Inhibition constant (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd1 | (+)-Catechin |  |

−7.86 | 1720 |

| Cmpd6 | 5,7-dimethoxyflavaN-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside |  |

−9.23 | 170.31 |

| Cmpd9 | Baicalein |  |

−6.51 | 16,950 |

| Cmpd14 | Luteoforol |  |

−7.02 | 7100 |

| Cmpd23 | Sophoridine |  |

−6.76 | 11,120 |

| Cmpd24 | Lycorine |  |

−7.67 | 2380 |

| Cmpd25 | Himachalol |  |

−7.00 | 7390 |

| Cmpd27 | β-himachalene |  |

−5.80 | 55,970 |

| Cmpd34 | Caesalmin B |  |

−8.82 | 342.79 |

| Cmpd35 | Bonducellpin D |  |

−9.28 | 156.75 |

| Control | α-ketoamide 13b |  |

−8.24 | 905.88 |

Table 6.

LigPlot analysis for top three lead compounds along with the control against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

| Compounds | Name | Hydrogen bonds | Hydrophobic interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd35 | Bonducellpin D | O2…..O(Glu166) (2.83 Å) O2…..N(Glu166) (2.91 Å) O4…..O(Glu166) (2.61 Å) O6…..N(Thr190) (2.92 Å) |

Met49, His164, Met165, Pro168, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189 and Gln192 (N = 8) |

| Cmpd6 | 5,7-dimethoxyflavaN-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | O8…..O(Glu166) (2.76 Å) O1…..N(Glu166) (3.22 Å) O7…..N(Thr190) (3.03 Å) O7…..N(Thr190) (2.44 Å) O9…..O(Gln192) (2.91 Å) |

Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143 Ser144, Cys145, His164, Met165, Leu167, Pro168, His172, Arg188 and Gln189 (N = 13) |

| Cmpd34 | Caesalmin B | O2…..N(Glu166) (3.32 Å) O2…..O(Glu166) (2.46 Å) O6…..N(Thr190) (3.01 Å) O6…..NE2(Gln192) (2.87 Å) |

Met49, His41, Tyr54, Cys145, His164, Met165, Leu167, Asp187, Arg188 and Glu189 (N = 10) |

| Control | α-ketoamide 13b | N23…..OD1(Asn142) (2.83 Å) O37…..SG(Cys145) (3.31 Å) O41…..N(Glu166) (3.12 Å) O40…..N(Glu166) (2.98 Å) |

Thr26, His41, Gly143, Phe140, Leu141, Ser144, His163, His164, Met165, Pro168, Asp187, Gln189, Thr190 and Gln192 (N = 14) |

Fig. 3.

Binding poses and molecular interactions between lead compounds and SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. (A) Bonducellpin D, (B) 5,7-dimethoxyflavanone-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside, (C) Caesalmin B, (D) α-ketoamide 13b (Control). The binding poses display the target enzyme in ribbon form with structural domains-I (orange-red), II (yellow) and III (forest green) where domain II and III are connected by a loop (cornflower blue) and the bound compounds are rendered as ball-and-stick (purple). The molecular interactions show hydrogen bonds as green dashed lines and hydrophobic interactions as semi-arcs with red eyelashes. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.5. Binding interaction studies of the lead compounds with SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro

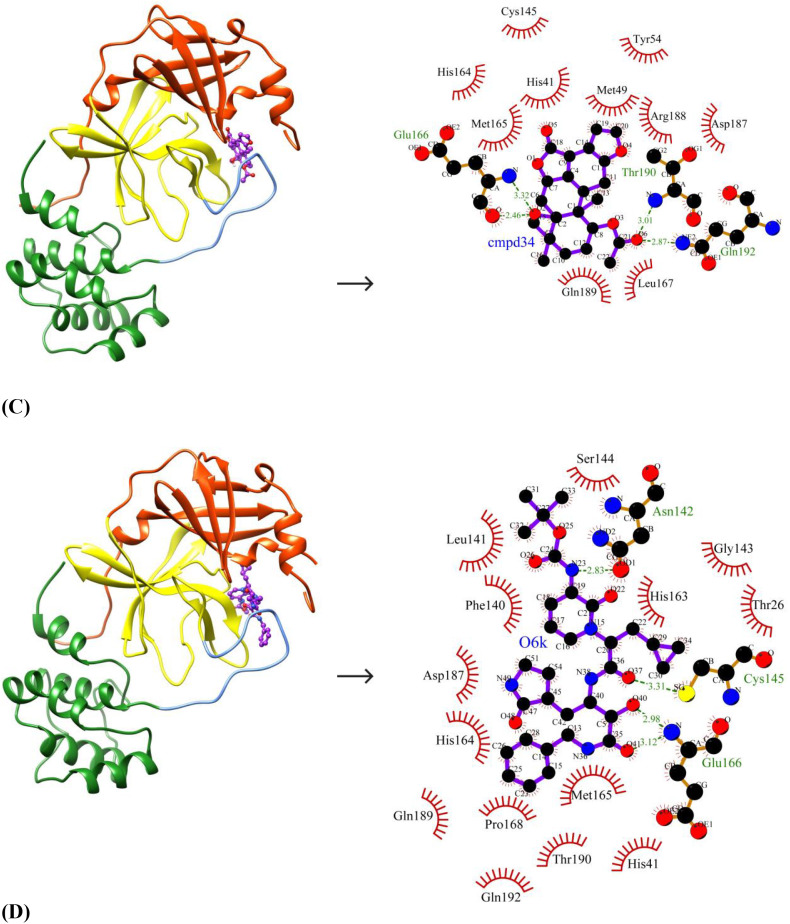

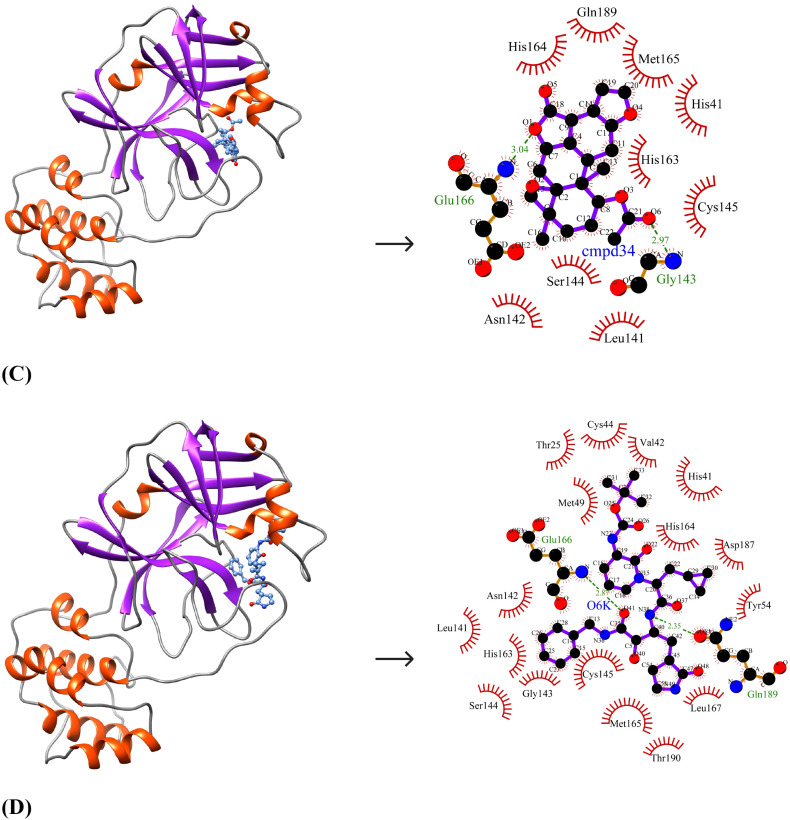

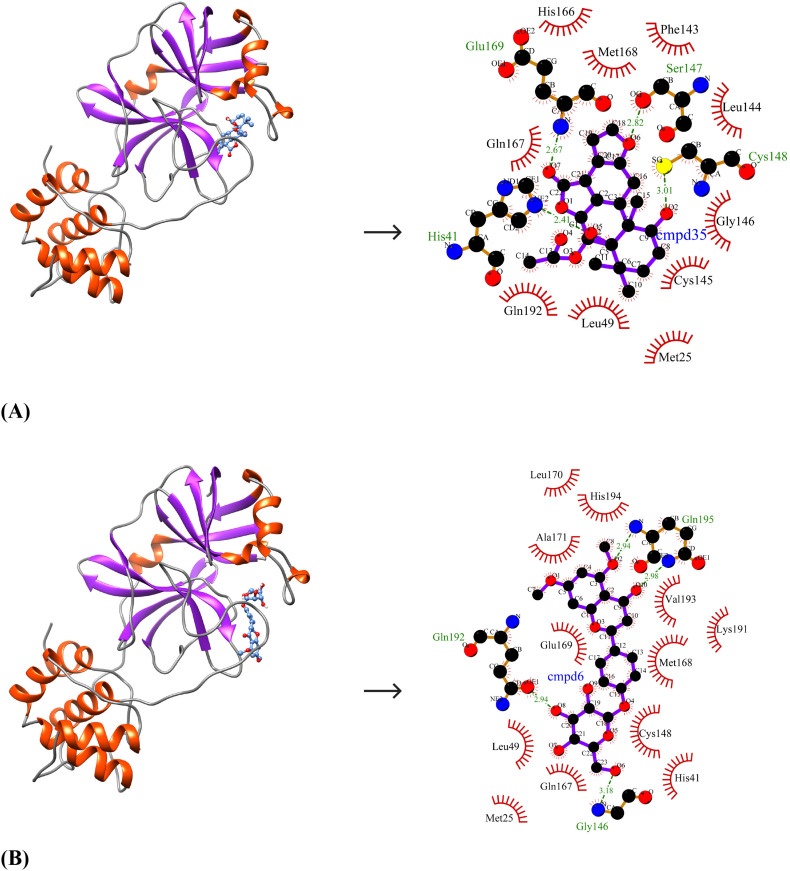

Due to the close similarity of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro to SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro at the structural level, the identified lead molecules may have broad-spectrum inhibitory activity and therefore, the binding affinities of the lead molecules against the other two target enzymes were studied. The binding energies and inhibition constants of the compounds against SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro are shown in Table 7 . The best-ranked lead molecule i.e., Bonducellpin D exhibits binding energies and inhibition constants of −8.64 kcal/mol and 467.11 nM; −8.93 kcal/mol and 284.86 nM against SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro respectively. It binds to SARS-CoV Mpro by establishing two hydrogen bonds with Gln189 and hydrophobic interacting residues include His41, Cys44, Met49, Tyr54, Asn142, Cys145, His164, Met165, Glu166, Asp187 and Arg188 (N = 11) (Fig. 4A). Bonducellpin D also shows good molecular interaction with MERS-CoV Mpro using four hydrogen bonds with residues His41, Ser147, Cys148 and Glu169 and residues such as Met25, Leu49, Phe143, Leu144, Cys145, Gly146, His166, Gln167, Met168 and Gln192 (N = 10) participate in hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 5A). With binding energies and inhibition constants of −8.94 kcal/mol and 282.15 nM; −8.55 kcal/mol and 539.13 nM against SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro respectively, the second lead molecule i.e., 5,7-dimethoxyflavanone-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside also shows broad-spectrum antiviral activities. 5,7-dimethoxyflavanone-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside shows favourable interactions with SARS-CoV Mpro through seven hydrogen bonds with His163, Glu166, Thr190 and Gln192 and hydrophobic interactions via residues Phe140, Leu141, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, Met165, Leu167, Pro168, His172, Gln189 and Ala191 (N = 11) (Fig. 4B). It also exhibits good binding to MERS-CoV Mpro through four hydrogen bonds via residues Gly146, Gln192 and Gln195 and the interaction is further strengthened through hydrophobic interactions via Met25, His41, Leu49, Cys148, Gln167, Met168, Glu169, Leu170, Ala171, Lys191, Val193 and His194 (N = 12) (Fig. 5B). The third lead compound- Caesalmin B shows binding energies and inhibition constants of −8.71 kcal/mol and 412.24 nM; −9.49 kcal/mol and 111.50 nM against SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro respectively. Caesalmin B shows optimum binding to SARS-CoV Mpro by forming two hydrogen bonds with residues Gly143 and Glu166 and hydrophobic interactions via residues His41, Leu141, Asn142, Ser144, Cys145, His163, His164, Met165 and Gln189 (N = 9) (Fig. 4C). It also exhibits good binding to MERS-CoV Mpro by establishing three hydrogen bonds with residues Cys145, Cys148 and His166 and hydrophobic interactions via residues Met25, Thr26, Leu27, Phe143, Leu144, Gly146, Ser147, Gln167, Met168, Glu169 and Gln192 (N = 11) (Fig. 5C). The control shows binding energies and inhibition constants of −8.62 kcal/mol and 482.81 nM; −11.36 kcal/mol and 4.75 nM against SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro respectively. The interaction between the control and SARS-CoV Mpro is mediated through two hydrogen bonds with Glu166 and Gln189 and hydrophobic interactions through residues-Thr25, His41, Val42, Cys44, Met49, Tyr54, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His163, His164, Met165, Leu167, Asp187 and Thr190 (N = 17) (Fig. 4D). It also shows good binding to MERS-CoV Mpro which involves seven hydrogen bonds with Cys145, Ser147, Cys148, Gln167 and Glu169 and hydrophobic interactions via residues Met25, Thr26, Leu27, His41, Phe143, Leu144, Gly146, His166, Met168, Leu170, Ala171, Gln192, Val193, His194 and Gln195 (N = 15) (Fig. 5D).

Table 7.

Molecular docking results for top 3 leads and control against SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro.

| SARS-CoV Mpro |

MERS-CoV Mpro |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | Name | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Inhibition constant (nM) | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Inhibition constant (nM) |

| Cmpd35 | Bonducellpin D | −8.66 | 467.11 | −8.93 | 284.86 |

| Cmpd6 | 5,7-dimethoxyflavaN-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | −8.94 | 282.15 | −8.55 | 539.13 |

| Cmpd34 | Caesalmin B | −8.71 | 412.24 | −9.49 | 111.50 |

| control | α-ketoamide 13b | −8.62 | 482.81 | −11.36 | 4.75 |

Fig. 4.

Binding pose and molecular interaction between lead compounds and SARS-CoV Mpro. (A) Bonducellpin D, (B) 5,7-dimethoxyflavanone-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside, (C) Caesalmin B, (D) α-ketoamide 13b (Control). The binding poses represent the target enzyme as ribbon where helices, sheets and loops are indicated by orange-red, purple and grey respectively and the bound compounds as ball-and-stick (cornflower blue). The molecular interactions are represented by the green dashed lines for hydrogen bonds and semi-arcs with red eyelashes for hydrophobic interactions. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 5.

Molecular interaction between lead compounds and MERS-CoV Mpro. (A) Bonducellpin D, (B) 5,7-dimethoxyflavanone-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside, (C) Caesalmin B, (D) α-ketoamide 13b (Control). The binding poses represent the target enzyme as ribbon where helices, sheets and loops are indicated by orange-red, purple and grey respectively and the bound compounds as ball-and-stick (cornflower blue). The molecular interactions are represented by the green dashed lines for hydrogen bonds and semi-arcs with red eyelashes for hydrophobic interactions. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.6. Comparison of binding affinity of the lead molecules with FDA-approved antiviral drugs

The binding energies and inhibition constants of the phytochemicals with the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro enzyme were compared with that of a set of twelve FDA approved antiviral drugs-a) Viral integrase inhibitors (Raltegravir and Dolutegravir) b) HIV-1 protease inhibitors (Nelfinavir and Lopinavir) c) HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors (Zidovudine and Nevirapine) d) HCV NS3/NS4B protease inhibitors (Simeprevir and Boceprevir) e) Neuraminidase inhibitors (Zanamivir and Oseltamivir) and f) HSV-1 thymidine kinase inhibitors (Acyclovir and Ganciclovir) (Suppl. Table 2). The results show that the binding energies and inhibition constant values of the phytochemicals were lower as compared to the majority of the approved antiviral drugs except for Nelfinavir (−9.54 kcal/mol), Boceprevir (−9.3 kcal/mol) and Simeprevir (−11.1 kcal/mol) which indicates that these phytochemicals have higher binding affinity to the target enzyme as compared to the antiviral drugs.

4. Conclusion

With the exponential increase in the mortality rate and lack of therapeutic interventions for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans, the discovery of novel drug molecules is crucial. SARS-CoV-2 Mpro is a well-characterized drug target and its recent structural elucidation through X-ray crystallography has opened an avenue for structure-based drug design. Herein, we have explored a small library of phytochemicals with previously reported antiviral properties for the identification of small molecular inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro using a computational approach. We identified three lead molecules- Bonducellpin D, 5,7-dimethoxyflavanone-4′-O-β-d-glucopyranoside and Caesalmin B which exhibit higher binding affinities as compared to the control. These lead molecules also demonstrate broad-spectrum antiviral activities against SARS-CoV Mpro and MERS-CoV Mpro. The current findings need further validations through in vitro and in vivo studies for developing into drug candidate molecules.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgement

The author ABG would like to thank the Department of Basic Sciences and Social Sciences for providing the necessary facilities for the research work. The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for its funding of the research through the research group project #RG-1438-015.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117831.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary tables

References

- 1.Rabi F.A., Al Zoubi M.S., Kasasbeh G.A., Salameh D.M., Al-Nasser A.D. SARS-CoV-2 and coronavirus disease 2019: what we know so far. Pathogens. 2020;9:231. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9030231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.-L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;17:181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou P., Fan H., Lan T., Yang X.-L., Shi W.-F., Zhang W., Zhu Y., Zhang Y.-W., Xie Q.-M., Mani S., et al. Fatal swine acute diarrhoea syndrome caused by an HKU2-related coronavirus of bat origin. Nature. 2018;556:255–258. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0010-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan Y., Zhao K., Shi Z.-L., Zhou P. Bat coronaviruses in China. Viruses. 2019;11:210. doi: 10.3390/v11030210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.-R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.-L., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.-M., Wang W., Song Z.-G., Hu Y., Tao Z.-W., Tian J.-H., Pei Y.-Y., et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorbalenya A.E., Baker S.C., Baric R.S., de Groot R.J., Drosten C., Gulyaeva A.A., Haagmans B.L., Lauber C., Leontovich A.M., Neuman B.W., Penzar D., Perlman S., Poon L.L.M., Samborskiy D.V, Sidorov I.A., Sola I., Ziebuhr J., C.S.G. of the I.C. on T. of Viruses The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L., Lin D., Sun X., Curth U., Drosten C., Sauerhering L., Becker S., Rox K., Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science (80-.) 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuba K., Imai Y., Rao S., Gao H., Guo F., Guan B., Huan Y., Yang P., Zhang Y., Deng W., et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus--induced lung injury, Nat. Med. 2005;11:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwani P., Mesters J.R., Hilgenfeld R. Coronavirus main proteinase (3CLpro) structure: basis for design of anti-SARS drugs. Science (80-. ) 2003;300:1763–1767. doi: 10.1126/science.1085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilgenfeld R. From SARS to MERS: crystallographic studies on coronaviral proteases enable antiviral drug design. FEBS J. 2014;281:4085–4096. doi: 10.1111/febs.12936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meng X.-Y., Zhang H.-X., Mezei M., Cui M. Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr. Comput. Aided. Drug Des. 2011;7:146–157. doi: 10.2174/157340911795677602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sethi A., Joshi K., Sasikala K., Alvala M. Drug Discov. Dev. Adv. IntechOpen; 2019. Molecular docking in modern drug discovery: principles and recent applications. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu A.-L., Du G.-H. Diet. Phytochem. Microbes. Springer; 2012. Antiviral properties of phytochemicals; pp. 93–126. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman D.J., Cragg G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Notka F., Meier G., Wagner R. Concerted inhibitory activities of Phyllanthus amarus on HIV replication in vitro and ex vivo. Antivir. Res. 2004;64:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parida M.M., Upadhyay C., Pandya G., Jana A.M. Inhibitory potential of neem (Azadirachta indica Juss) leaves on dengue virus type-2 replication. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002;79:273–278. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serkedjieva J., Ivancheva S. Antiherpes virus activity of extracts from the medicinal plant Geranium sanguineum L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1998;64:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rehman S., Ashfaq U.A., Riaz S., Javed T., Riazuddin S. Antiviral activity of Acacia nilotica against hepatitis C virus in liver infected cells. Virol. J. 2011;8:220. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halgren T.A. Merck molecular force field. I. Basis, form, scope, parameterization, and performance of MMFF94. J. Comput. Chem. 1996;17:490–519. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199604)17:5/6<490::AID-JCC1>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurung A.B., Bhattacharjee A., Ali M.A. Exploring the physicochemical profile and the binding patterns of selected novel anticancer Himalayan plant derived active compounds with macromolecular targets. Informatics Med. Unlocked. 2016;5:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim S., Thiessen P.A., Bolton E.E., Chen J., Fu G., Gindulyte A., Han L., He J., He S., Shoemaker B.A., Wang J., Yu B., Zhang J., Bryant S.H. PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D1202–D1213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipinski C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004;1:337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sander T., Freyss J., Korff M. von, Rufener C. DataWarrior: an open-source program for chemistry aware data visualization and analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015;55:460–473. doi: 10.1021/ci500588j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gurung A.B., Ali M.A., Bhattacharjee A., AbulFarah M., Al-Hemaid F., Abou-Tarboush F.M., Al-Anazi K.M., Al-Anazi F.S.M., Lee J. Molecular docking of the anticancer bioactive compound proceraside with macromolecules involved in the cell cycle and DNA replication. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016;15 doi: 10.4238/gmr.15027829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., Ferrin T.E. UCSF chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du X., Li Y., Xia Y.-L., Ai S.-M., Liang J., Sang P., Ji X.-L., Liu S.-Q. Insights into protein-ligand interactions: mechanisms, models, and methods. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:144. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adejoro I.A., Waheed S.O., Adeboye O.O. Molecular docking studies of Lonchocarpus cyanescens triterpenoids as inhibitors for malaria. J. Phys. Chem. Biophys. 2016;6:398–2161. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laskowski R.A., Swindells M.B. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:2778–2786. doi: 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xue X., Yu H., Yang H., Xue F., Wu Z., Shen W., Li J., Zhou Z., Ding Y., Zhao Q., et al. Structures of two coronavirus main proteases: implications for substrate binding and antiviral drug design. J. Virol. 2008;82:2515–2527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02114-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Januar H.I., Dewi A.S., Marraskuranto E., Wikanta T. In silico study of fucoxanthin as a tumor cytotoxic agent. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2012;4:56. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.92733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang R.-W., Ma S.-C., He Z.-D., Huang X.-S., But P.P.-H., Wang H., Chan S.-P., Ooi V.E.-C., Xu H.-X., Mak T.C.W. Molecular structures and antiviral activities of naturally occurring and modified cassane furanoditerpenoids and friedelane triterpenoids from Caesalpinia minax. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002;10:2161–2170. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orhan D.D., Özçelik B., Özgen S., Ergun F. Antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral activities of some flavonoids. Microbiol. Res. 2010;165:496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables