Abstract

The supercapacitor has been widely seen as one of the most promising emerging energy storage devices, by which electricity is converted from chemical energy and stored. Two-dimensional (2D) metal oxides/hydroxides (TMOs/TMHs) are revolutionizing the design of high-performance supercapacitors because of their high theoretical specific capacitance, abundance of electrochemically active sites, and feasibility for assembly in hierarchical structures by integrating with graphitic carbon, conductive polymers, and so on. The hierarchical structures achieved can not only overcome the limitations of using a single material but also bring new breakthroughs in performance. In this article, the research progress on 2D TMOs/TMHs and their use in hierarchical structures as supercapacitor materials are reviewed, including the evolution of supercapacitor materials, the configurations of hierarchical structures, the electrical properties regulated, and the existence of advantages and drawbacks. Finally, a perspective covering directions and challenges related to the development of supercapacitor materials is provided.

Keywords: two-dimensional nanosheets, transition metal oxide and hydroxide, hierarchical structure, integration, supercapacitor

Introduction

Global warming and the rapid depletion of fossil fuels are driving the development of sustainable and renewable energy. At present, the renewable energy sources of wind, tidal, geothermal, and solar energy have been researched and utilized (Yuksel and Ozturk, 2017; Cranmer et al., 2018; Mo et al., 2018; Song et al., 2018). However, these energy sources are highly dependent on nature, which is variable and unpredictable. Hence, an energy storage system is essential for efficiently collecting this natural energy, and, meanwhile, allows the energy to be rapidly exported in the form of stable electric energy. In recent years, the supercapacitor is becoming popular as a kind of energy storage device that is not only efficient and practical but also convenient and environmental friendly (Lukatskaya et al., 2016; Salanne et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017).

The supercapacitor is also known as a Faraday quasi capacitor or electrochemical capacitor. It stores charges through a reversible redox reaction at the interface between electrode materials and electrolyte, unlike a traditional capacitor, it offers higher specific capacity and energy density (Simon and Gogotsi, 2010; Kate et al., 2018). Compared with a secondary battery, the supercapacitor possesses overwhelming advantages in terms of a shorter charging time and a long cycle life and, higher power density (Staaf et al., 2014; Zhao and Sun, 2018). Therefore, the supercapacitor is a kind of energy storage device that is intermediate between a traditional capacitor and a secondary battery that can be regarded as a complementary device between a battery and a traditional capacitor and can meet the needs of human beings for new energy.

The structural configuration of a supercapacitor mainly consists of electrode material, a diaphragm, electrolyte, and collecting fluid (Muzaffar et al., 2019). The energy storage is mainly from the charge transfer process at the interface of electrode and electrolyte, so the electrode material is the key factor in the performance of the supercapacitor. At present, there are three prevailing types of electrode materials under research, namely carbon materials [e.g., graphene (Liu et al., 2010), carbon nanotubes (Shang et al., 2015), activated carbon (Gamby et al., 2001; Jin et al., 2016), and porous carbon (Bu et al., 2017)], conducting polymer materials [e.g., polyaniline (PANI) (Lim et al., 2015; Lyu et al., 2019), polypyrrole (PPy) (Huang et al., 2015), polythiophene (PTh) (Ambade et al., 2017), and poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) (Liu et al., 2008)], and TMOs/TMHs [RuO2 (Sugimoto et al., 2003), MnO2 (Song et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2018), MoO3 (Brezesinski et al., 2010; Hanlon et al., 2014), Nb2O5 (Augustyn et al., 2013), V2O5 (Qi et al., 2018), Ni(OH)2 (Ida et al., 2008; Fu et al., 2014), and Co(OH)2 (Ji et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2014)]. In particular, carbon material is the most widely used electrode material due to its diversity and abundance as a resource. The capacitance over a carbon-based supercapacitor electrode is achieved through pure electrosorption of the electrical double-layer; thus, the structure of the electrode material will not collapse with the insertion and withdrawn of electrolyte ions during the charging and discharging processes. This leads to superior cycle stability, extending to tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of cycles (Frackowiak and Beguin, 2001; Liu et al., 2014). However, the energy density of carbon-based supercapacitors is low due to the storage mechanism, which rarely meets the needs of practical application. In contrast, conducting polymer electrode materials achieve high charge density by a reversible redox reaction of elements doping/dedoping, thus realizing large electric energy storage (Snook et al., 2011). However, the conducting polymer skeleton is prone to expanding and shrinking in the charging–discharging process, leading to low cycle stability (González et al., 2016). In addition, most of the conducting polymer materials are dense structures with limited interfaces, which restricts the amount of electrode material that is able to fully contact with the electrolyte and results in relatively low power density.

It is noteworthy that TMOs/TMHs exhibit potential for the fabrication of supercapacitor electrodes due to their high theoretic capacity and ultrahigh power density (Yuan et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015; Zhang H. et al., 2015; Nguyen and Montemor, 2019). The energy storage can be achieved by either electrosorption or reversible redox reactions (Lee et al., 2010). Normally the valance state would change accompany with the charging–discharging process. Hence, for comparison, TMOs/TMHs have exhibited higher powder density and stability than traditional carbon and conducting polymer materials. Although problems arise from their narrow working voltage window, low conductivity, and small reaction area, these can be solved by structural engineering and composition, such as by controlling dimensionality and morphology (Zhu et al., 2014; Najafpour et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015; Yue and Liang, 2015; Yu et al., 2015).

In this review, we summarize the recent progress in 2D TMOs/TMHs as supercapacitor electrode material. Further, 2D transition metal oxide/hydroxide-based hierarchical structures are covered. The different technical strategies in design and synthesis for optimizing the conductivity, structural stability, surface physical, and chemical properties, and structural morphology of the hierarchical composites are also detailed. A supercapacitor electrode with high specific capacitance, good rate capability, and excellent cycle stability can be obtained by tuning the electrochemical properties of the electrode materials. Finally, a perspective covering directions and challenges related to the development of supercapacitor materials is provided.

Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Oxides/Hydroxides

Transition metal oxides/hydroxides (TMOs/TMHs) are the most representative active electrochemical pseudocapacitor materials and are widely known for their high theoretical capacitance, abundance in nature, and high energy density (Jiang et al., 2012). However, poor intrinsic conductivity and other shortcomings have limited their performance as supercapacitor materials. Hence, 2D ultrathin TMOs/TMHs have been widely studied and applied in supercapacitors due to their advantages of high specific surface area and improved planar electronic conductivity (Gao et al., 2014; Liu W. et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2018). Most importantly, the atomic thickness shortens the ion diffusion path and reduces ion diffusion resistance.

So far, there are two main strategies, that is, “top-down” and “bottom-up” methods, for obtaining 2D TMOs/TMHs (Sun et al., 2017; Mei et al., 2018), as shown in Table 1. “Top-down” mainly refers to the chemical or mechanical exfoliation of layered bulk materials, such as by mechanical exfoliation and liquid-phase exfoliation (Coleman et al., 2011; Rui et al., 2013; Zhang Y. Z. et al., 2015; Peng et al., 2017; Zavabeti et al., 2017; Tao et al., 2019). It is reported that MoO3, MnO2, and RuO2 nanosheets, etc., can be made at a large scale by ultrasonic exfoliation in ethanol/water and can be applied to solid-state symmetrical supercapacitors (Dutta et al., 2019). A liquid-phase exfoliation method with the aid of lithium (Li) intercalation and de-intercalation was developed for the preparation of quasi-layered VO2 ultrathin nanosheet (Liu et al., 2012). The underlying mechanism is the insertion of Li ions to break the chemical bonds of the layers. Subsequent replacement of Li ions by larger molecules and ultrasonic treatment can result in a dispersed VO2 ultrathin nanosheet. The “bottom-up” synthetic protocol starts from appropriate design at the atomic or molecular level by the aid of technologies, such as self-assembly (Sun J. et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2017), chemical vapor deposition (Lee and Sung, 2012; Liu et al., 2015), directional connection, and topological chemical transformation of layered intermediates (Liu et al., 2016; Wen et al., 2017; Bao et al., 2018), to synthesize a 2D nanostructure. For instance, five atomic layer thickness Co(OH)2 ultrathin nanosheet was synthesized by the orientation connection method and was assembled into an asymmetric vertical all-solid-state flexible supercapacitor with excellent specific capacitance and cycle stability (Gao et al., 2014). For non-layered 2D materials, Qiu and Zheng, for the first time, successfully observed the in-situ transformation of metal oxides from 3D nanoparticles as intermediate products to 2D oxide nanoflakes by LBNL's in-situ liquid-phase transmission electron microscopy technology, revealing the new evolution strategy of 3D to 2D materials at the atomic level, and also paving the way to obtaining ultrathin nanostructures from non-layered materials (Yang et al., 2019).

Table 1.

Summary and comparison between top-down and bottom-up strategies for the fabrication of 2D TMOs/TMHs and their pros and cons.

| Strategy | Method | 2D TMOs/TMHs | References | Pros and cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top-down | Mechanical cleavage | MnO2 | Peng et al., 2017; Dutta et al., 2019 | Easy operation; Only applicable for layered structure materials |

| MoO3 | Dutta et al., 2019 | |||

| RuO2 | Dutta et al., 2019 | |||

| Ti5NbO14 | Zhang et al., 2010 | |||

| Liquid-phase exfoliation | V2O5 | Rui et al., 2013 | ||

| VO2 | Liu et al., 2012 | |||

| MoO3 | Zhang Y. Z. et al., 2015 | |||

| Bottom-up | Self-assembly | TiO2 | Sun J. et al., 2014 | Applicable for both layered and non-layered structure materials; Can be produced at large scale; Harsh synthetic conditions; Difficult to obtain high-quality 2D crystals. |

| ZnO | Sun et al., 2017 | |||

| Co3O4 | Hu et al., 2017 | |||

| WO3 | Sun J. et al., 2014 | |||

| Chemical vapor deposition | TiO2 | Lee and Sung, 2012 | ||

| WO3 | Liu et al., 2015 | |||

| Directional connection | SnO2 | Wang C. et al., 2012 | ||

| CeO2 | Yu et al., 2010 | |||

| Co(OH)2 | Gao et al., 2014 | |||

| Topological chemical transformation | WO3 | Liu et al., 2016 | ||

| Nb2O5 | Wen et al., 2017 | |||

| ZnCo2O4 | Bao et al., 2018 | |||

| Cobalt nickel oxide | Yang et al., 2019 |

2D TMOs/TMHs-Based Hierarchical Engineering for Supercapacitor Materials

Although great efforts have been put into the development of 2D TMOs/TMHs for supercapacitor electrodes, challenges still exist when using a single electrode material. The drawback lies in low actual capacitance, limited improvement of energy density, and the poor rate capability caused by low conductivity, which have restricted the performance of such supercapacitors in practical applications (Jiang et al., 2012; Mahmood et al., 2019). In order to overcome the limitations of single electrode materials, it is necessary to combine 2D TMOs/TMHs with other low-dimensional nanomaterials to construct hierarchical nanostructures, which can not only optimize the configuration to overcome the agglomeration of 2D nanosheets but also complement and enhance the performance of different electrode materials so as to realize effective improvement of the performance for the supercapacitor device (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the use of TMOs/TMHs nanosheets to form 2D TMOs/TMHs-based hierarchical structures for a supercapacitor with expected performance promotion.

TMOs/TMHs Hierarchical Structures

The engineering of hierarchical structures by hybridizing different TMOs/TMHs is regarded as an efficient strategy to combine the advantages of different materials (Wu et al., 2013; Dinh et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2016, 2018; Ouyang et al., 2019). The function of this kind of hierarchical structure can be generally summarized as overcoming the drawbacks of the individual components and preventing agglomeration of nanosheets. Thus, capacitance performance is predominantly enhanced because of the expected synergistic effect. Hierarchical structures with different morphologies can be formed through self-assembly (Huang et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2018), layer stacking (Zhu et al., 2012), and heterostructure core-shell engineering (Li et al., 2014; Sun Z. et al., 2014; Ho and Lin, 2019), which also have significant effects on the energy density and stability of the supercapacitors.

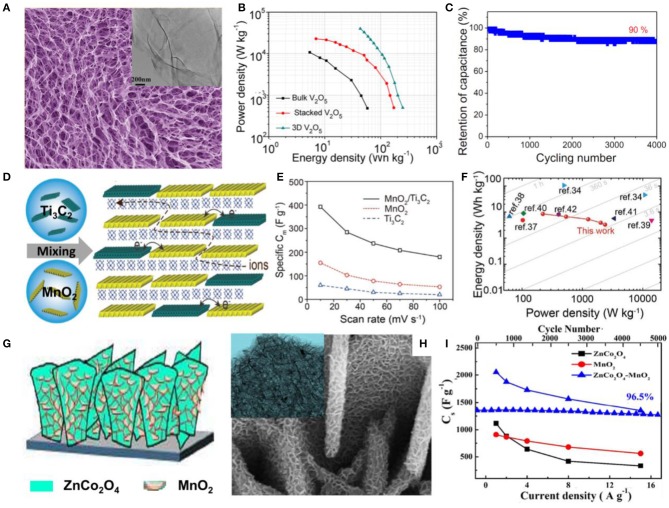

A 3D V2O5 architecture was constructed by using ultrathin V2O5 nanosheets as building blocks with a thickness of 4 nm via a freeze-drying process (Zhu et al., 2013). Due to the benefits of its porous and ultrathin nature, as well as the 3D interpenetrating structure, a high surface area and shortened diffusion length were expected, thus enabling such a supercapacitor electrode to exhibit high capacitance, high energy density, and excellent stability (Figures 2A–C). A flexible film-like supercapacitor was fabricated via a vacuum filtration method by integrating MnO2 and Ti3C2 nanoflakes as the electrode, as shown in Figure 2D (Liu Y. et al., 2017). With the aid of good solubility, similar two-dimensional geometry, the high theoretical capacity of MnO2, and the good conductivity of Ti3C2, the composite electrode exhibited good capacitance performance with a high mass-specific capacitance of 305 F/g at a current density of 1 A/g. The fabricated symmetrical flexible supercapacitor device exhibited a maximum energy density of 8.3 Wh/kg, and the power density could reach 2,376 W/kg (Figures 2E,F). Characterizations and deeper understanding of the interaction between the stacked hierarchical structure and electrochemical performance revealed that the layered stacking structure is more conducive to improve the electrochemical performance of the electrode compared with traditional capacitors.

Figure 2.

(A) FESEM images of the 3D V2O5 architecture constructed from nanosheets (inset: TEM image of a nanosheet). (B) Power density and energy density of three electrodes. (C) Cycling performance of the 3D V2O5 architecture (Zhu et al., 2013). (D) Schematic drawing of the fabrication of the MnO2/Ti3C2 hybrid film, with molecular sheets stacked in a randomly interstratified manner. (E) Rate capability of the hybrid MnO2/Ti3C2 electrode compared with neat MnO2 and Ti3C2 electrodes. (F) Performance comparison of the MnO2/Ti3C2 hybrid with other reported materials on a Ragone plot (Liu W. et al., 2017). (G) Schematic of the coating of ZnCo2O4 nanoflakes with MnO2 nanosheets. (H) FESEM images and (inset) TEM images of ZnCo2O4 nanoflakes coated with MnO2 nanosheets. (I) Variation in Cs with respect to current density and cycling performance at 15 A/g for electrodes (Gao et al., 2017).

Forming a heterostructure or core-shell structures has been adopted as an efficient strategy for offering a large surface area for more Faradaic reaction sites and high conductivity to accelerate the charge transfer and therefore to improve the electrochemical performances of nanocomposites. For instance, a ZnCo2O4-MnO2 heterostructure on Ni foam was shown to be an active electrode material with a porous nanostructure, providing a considerably large electroactive area, and exhibited ideal capacitive behavior, with a maximum Cs of 2,057 F/g at a current density of 1 A/g and cycling stability of 96.5% after 5,000 cycles (Kumbhar and Kim, 2018) (Figures 2G–I). Unique core-shell arrays of CoFe2O4@MnO2 on nickel foam were also studied as an electrode material for a supercapacitor. Compared to the individual CoFe2O4 and MnO2 nanosheets, the composite electrode exhibited much higher specific area capacitance of 3.59 F/cm2 (≈1,995 F/g) at a current density of 2 mA/cm2 and a smaller semicircle in EIS, indicating faster ion insertion/extraction during electrochemical reactions, which can all be attributed to the hierarchical core-shell nanostructure. The asymmetric supercapacitor assembled using a CoFe2O4@MnO2 electrode had maximum energy density and maximum power density of 37 Wh/kg and 4,800 W/kg, respectively, with long-term cycling stability (91.4% retention after 2,250 cycles) (Gao et al., 2017).

Besides, mixed dimensional hierarchical structures have also been reported. For instance, a hybrid of NiCo2O4-MoS2 consisting of 2D NiCo2O4 nanosheets and 1D MoS2 nanowires were grown on a 3D Ni foam network, forming mixed-dimensional hierarchical structures, as shown in Figures 3A–C. During the growth process, NiCo2O4 nanosheets intertwined on the Ni surface, providing sites for MoS2 nanowires, while a higher concentration of S2− lead to thinner nanowires. These features enable a high specific surface area and a shortened diffusion path for ions and electrons, which lead to the enhancement of the electron/ion transfer rate in the electrodes (Wen et al., 2018). The assembled supercapacitor device delivered a maximum energy density of 18.4 Wh/kg and a power density of 1200.2 W/kg with excellent stability (specific capacitance retention of 98.2% after 8,000 cycles) (Figures 3D,E).

Figure 3.

(A) Schematic illustration of the synthesis procedure of a MoS2 nanowires/NiCo2O4 nanosheets composite. (B) SEM images of the NiCo2O4 nanosheets supported on Ni foam. (C) SEM images of the composite supported on Ni foam. (D) Ragone plot and (E) cycling performance of the composite (Wen et al., 2018).

TMOs/TMHs/Carbon-Based Hierarchical Structures

Graphene, described as the “famous star” among carbon materials (Gong et al., 2016), it is an excellent two-dimensional scaffold upon which to construct composite materials with 2D TMOs/TMHs because its large surface area and the huge amount of cross-linking of the conjugated π-bond structure endow it with superior conductivity (in-plane carrier mobility up to 200,000 cm2v−1s−1) and physical structure stability (high mechanical strength and flexibility) (Novoselov et al., 2012). The electronic conduction and mechanical stability of the hierarchical structure formed are improved by the synergistic effect of the two components (Stankovich et al., 2006). Hence, a supercapacitor with excellent performance is expected due to the improved electrochemical reaction rate and cycle stability.

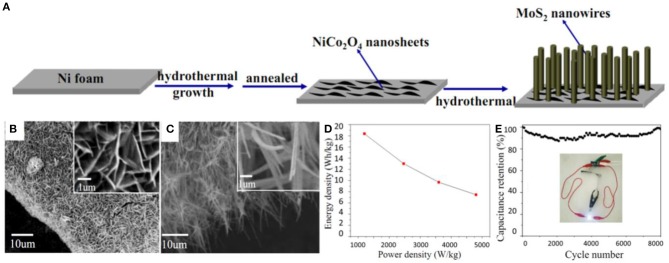

At present, a large amount of progress has been made in the preparation of high-performance energy storage materials by combining TMOs/TMHs with graphene. The application of pseudocapacitive V2O5 nanosheets and graphene in all-solid-state flexible thin-film supercapacitors (ASSTFSs) has been reported (Bao et al., 2014). By rationally integrating the two components, electron transfer was accelerated, and diffusion paths were shortened, leading to strong electrochemical performance, with a capacitance of 11,718 μF/cm2 at 0.2 A/m2, an energy density of 1.13 μW h/cm2 at a power density of 10.0 μW/cm2, and excellent long-term cycling stability for 2,000 charge–discharge cycles (Figure 4). The superior electrochemical performance thoroughly demonstrated the merit of a hierarchical architecture combining pseudocapacitive V2O5 nanosheets and graphene.

Figure 4.

(A) Schematic illustration of the flexible ASSTFS. (B) SEM images of the as-obtained V2O5 nanosheet/graphene nanocomposite. (C) The first four cycles of a galvanostatic charge–discharge curve of the as-fabricated ASSTFS at a current density of 2.5 A/m2. (D) Long-term cycling stability investigation of the ASSTFS after repeated bending/extension for 500 cycles (Bao et al., 2014).

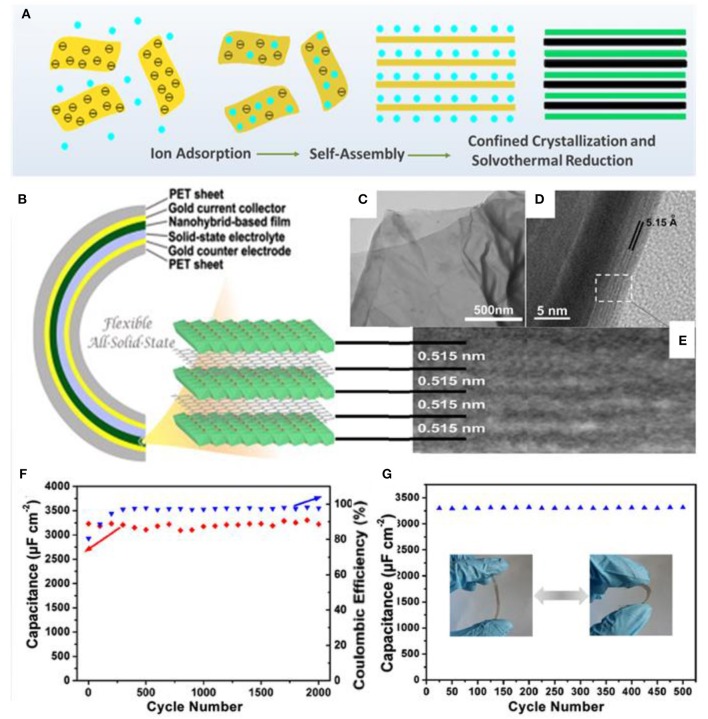

The Xie, group for the first time, fabricated a flexible all-solid-state thin-film pseudocapacitor using β-Ni(OH)2/graphene hybrid nanosheets as electrode materials via a layer-by-layer method (Xie et al., 2013). The assembly process of the β-Ni(OH)2/graphene hybrid includes electrostatic interaction between GO and Ni2+, interlayer Ni2+ diffusion, and confined (NiOH)2 crystallization, as well as simultaneous reduction of graphene (Figures 5A–E). The combination of highly conductive graphene and pseudocapacitive β-Ni(OH)2 guarantees high specific capacitance and excellent stability for this novel energy storage material. The fabricated all-solid-state thin-film pseudocapacitor exhibits a high volumetric specific capacitance of 660.8 F/cm and good cycling ability, as well as excellent flexibility with negligible degradation after 200 bending cycles (Figures 5F,G). Meanwhile, the ultrathin configuration of the hybrid nanosheets endows superior mechanical properties for the as-fabricated device, which can be regarded as a feasible energy supply for the exploitation of flexible electronics.

Figure 5.

(A) Schematic illustration of the layer-by-layer formation mechanism of β-Ni(OH)2/graphene nanohybrids. (B) Schematic illustration of the flexible all-solid-state thin-film supercapacitor with pseudocapacitive β-Ni(OH)2/graphene nanohybrids as active materials. (C) TEM image of the as-prepared nanohybrids, confirming the nanosheet morphology. (D) Cross-sectional HR-TEM images and (E) enlarged view of the HR-TEM image of the curled fringe of the nanohybrid sheet. (F) Long-term cycling stability of the flexible ASSTFS based on the nanohybrids (98.2% for the 2,000th cycle). (G) Cycling stability of the flexible ASSTFS measured after repeated bending/extension deformation (Xie et al., 2013).

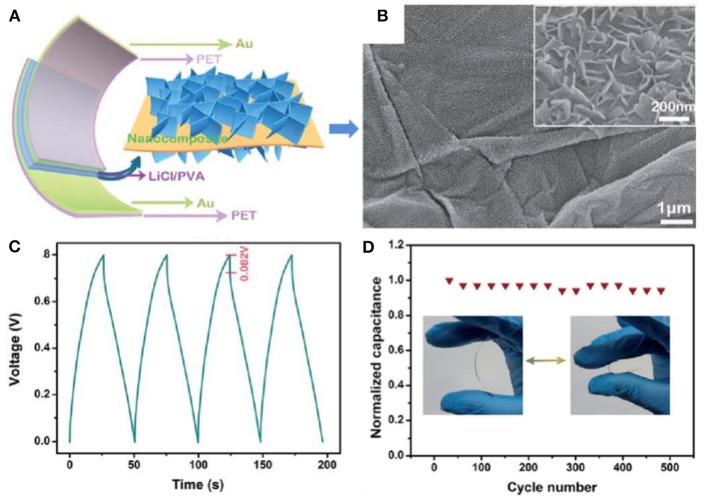

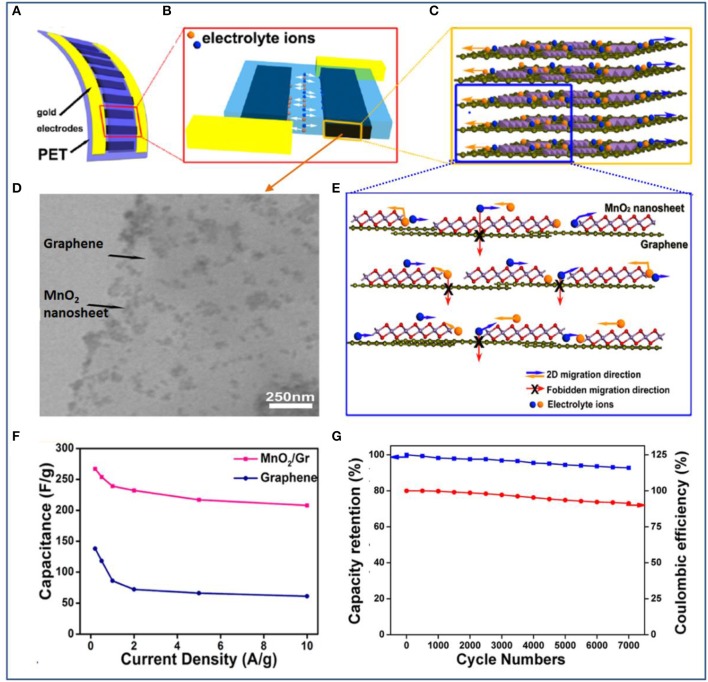

Following the all-solid-state planar configuration, the Xie group developed a quasi-2D ultrathin MnO2/graphene hybrid for fabricating a novel and high-performance planar supercapacitor (Peng et al., 2013). To make the best of the designed planar structure, a vacuum filtration method is adopted to produce films with controllable thickness and transferability. These hybrid 2D δ-MnO2/graphene thin films can be transferred onto a range of substrates such as PET, quartz, glass, and silicon wafer. By filling with a gel electrolyte of PVA/H3PO4, an all-solid-state planar supercapacitor is fabricated (Figures 6A,B). Owing to the planar peculiarity of both graphene and δ-MnO2 nanosheets, more electrochemically active surfaces for absorption/desorption of electrolyte ions were introduced, and charge transport was accelerated at the hybridized interlayer during the charging and discharging processes (Figures 6C–E). The device exhibited high specific capacitances of 267 F/g at a current density of 0.2 A/g and 208 F/g at 10 A/g and excellent rate capability and cycling stability (capacitance retention of 92% after 7,000 cycles) (Figures 6F,G).

Figure 6.

(A) Schematic illustration of an ultraflexible planar supercapacitor constructed with a hybrid film as the working electrode, a current collector, and a gel electrolyte on a plastic polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate. (B) The planar supercapacitor unit, showing that the 2D hybrid thin film functions as two symmetric working electrodes. (C) The hybrid thin film was formed by stacking layers of chemically integrated quasi-2D δ-MnO2 nanosheets and graphene sheets. (D) TEM image of the 2D hybrid structure with δ-MnO2 nanosheets integrated on graphene surfaces. (E) Schematic description of the 2D planar ion transport favored within the 2D δ-MnO2/graphene hybrid structures. (F) Comparison of specific capacitance values for the supercapacitors based on hybrids and based on graphene. (G) Capacitance retention (blue) and Coulombic efficiency (red) of the planar supercapacitor device based on hybrids over 7,000 charge/discharge cycles (Peng et al., 2013).

In addition to these pioneering and representative research studies, numerous reports on the integration of TMOs/TMHs with graphene to prepare high-performance electrode materials for supercapacitors have revealed the general functions of the hierarchical structures (Wang G. et al., 2012; Mahmood et al., 2019; Nguyen and Montemor, 2019). The incorporation of graphene improves the conductivity of the pseudocapacitor electrode material and the constraints of the low specific capacitance of the graphene as a double-layer capacitor electrode material, and the advantages of the two are superimposed to achieve a substantial improvement in the capacitance performance, which is a feasible strategy for improving the electrochemical performance of the TMO/TMH electrode material.

TMOs/TMHs/Conducting Polymer Hierarchical Structures

Conducting polymer has become an important electrode material for pseudocapacitors due to the advantages of large capacity, good conductivity, facile synthesis, and low cost (Kalaji et al., 1999). In the past few years, conducting polymers have attracted increasing attention due to their great potential in supercapacitors. However, the conductive polymer-based electrode still suffers the drawbacks of low stability and poor mechanical properties, which restrict its application in fabricating supercapacitor devices (Liu et al., 2019). In terms of countermeasures, an inorganic-organic composite combination can improve the mechanical properties, electrochemical properties, and stability. Organic-inorganic composite electrode materials with excellent performance can be prepared to improve the specific capacitance and cycle stability of the electrode materials of supercapacitors.

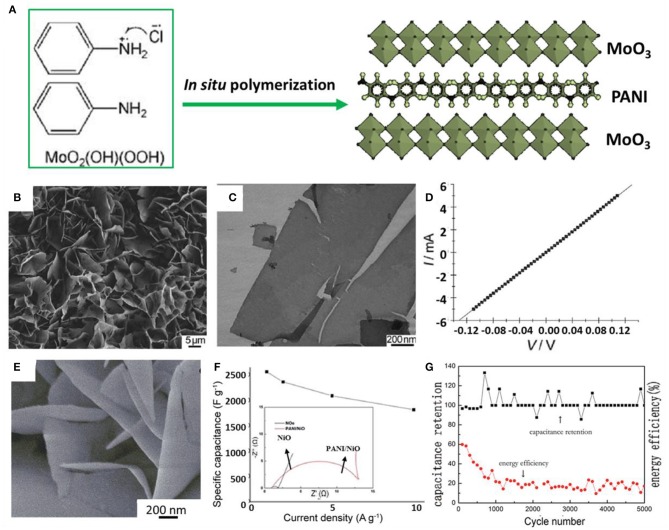

As a representative conducting polymer, polyaniline (PANI) has frequently been used to combine with TMOs/TMHs to fabricate hierarchical structural hybrids for supercapacitor materials. As reported earlier, MoO3/PANI nanocomposites have been synthesized by a simple in-situ synthesis method using molybdenum oxide precursor precipitation and aniline monomer as raw materials, as shown in Figures 7A–C (Zheng et al., 2011). The PANI polymer chains are assembled between oxide layers, which cause the nanocomposite to exhibit a flexible layered hierarchical structure. The electrical properties of metal oxides as active supercapacitor materials are greatly improved, which gives them excellent conductivity (Figure 7D). The outstanding performance was inferred to derive from the robust bonding through in-situ polymerization. Hence, nanocomposites prepared by in-situ reaction at the molecular level have significantly improved specific capacity and cycle stability, making them very suitable for the electrochemical energy storage application.

Figure 7.

(A) Representation of the simultaneous reaction mechanism of hybrid PANI/MoO3 nanocomposites. (B) SEM images and (C) TEM images of the prepared hybrid PANI/MoO3 nanosheets. (D) I–V characteristics of the hybrid nanosheet (Zheng et al., 2011). (E) SEM images of the PANI/NiO electrode. (F) Specific capacity of the PANI/NiO electrode in different current densities and (inset) EIS curves. (G) Capacitance retention and energy efficiency curves of the PANI/NiO electrode produced in the best condition (Sun et al., 2016).

A PANI-NiO composite on nickel foam that was used as a supercapacitor electrode and was fabricated via a binder-free in-situ approach showed high specific capacitance (2,565 F/g at a current density of 1 A/g) and excellent cycling stability (with a high retention of 100% for almost 5,000 cycles) (Sun et al., 2016). The flower-like hierarchical structures offer a structural benefit enabling high levels of redox (Figures 7E–G). Detailed studies revealed that the Ni foam was the current collector and Ni source for in-situ deposition of NiO, establishing a steadier bonding between collector and active material. PANI that was deposited directly onto the electrode supported the structure and prevented the functional space structure from being destroyed and collapsing during the charging–discharging process. The resultant impressive cycling stability shows considerable potential for commonly used energy storage devices with long service lives.

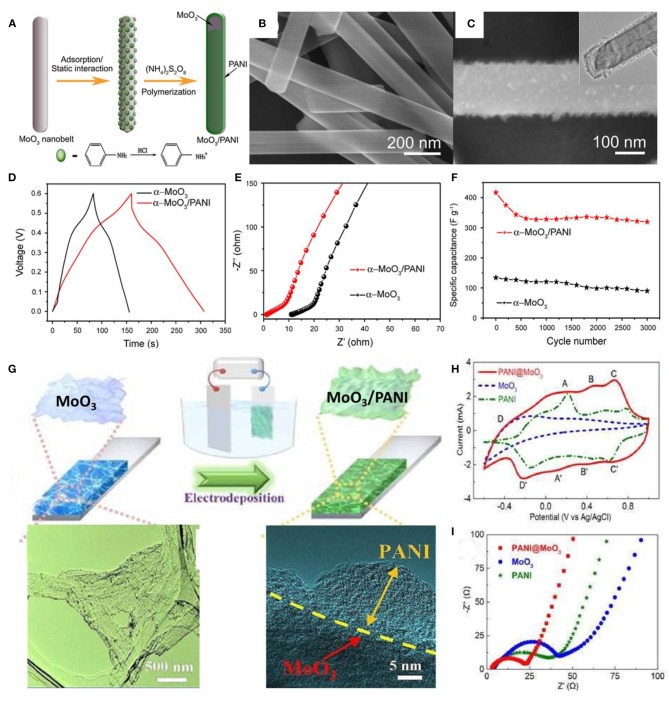

Post-functionalization of TMOs/TMHs with PANI through polymerization provides the hybrid core-shell or sandwich hierarchical configurations. For example, adsorption of benzene amine on MoO3 nanobelts and further polymerization lead to the formation of coaxial heterostructure nanobelts of MoO3/PANI, which exhibited lower electric resistance than MoO3 nanobelts and pure PANI (Figures 8A–F). The supercapacitors achieved high specific capacitances of 714 F/g at a scan rate of I mV/s and 632 F/g at a current density of 1 A/g (Jiang et al., 2014).

Figure 8.

(A) Schematic illustration of the formation of the MoO3/PANI coaxial heterostructure nanobelts. (B) SEM images of the original α-MoO3 nanobelts. (C) SEM images and (inset) TEM images of the as-synthesized MoO3/PANI coaxial heterostructure nanobelts. (D) A comparison of the galvanostatic charge–discharge curves of the two comparative materials at a current density of 2 A/g. (E) EIS spectra comparison and (F) cycling performance at a scan rate of 50 mV/s of the two comparative materials (Jiang et al., 2014). (G) Schematic illustration for the synthesis process of 3D MoO3/PANI hybrid nanosheet network film. (H) CV curves of MoO3, PANI, and 3D MoO3/PANI hybrid nanosheet network films in the potential range from −0.6 to 1 V at a scanning rate of 50 mV/s. (I) Nyquist plots of the MoO3, PANI, and 3D MoO3/PANI hybrid nanosheet network films (Zhang et al., 2017).

In order to overcome the low stability of conducting polymers as electrode material, a porous structure is usually introduced to guard against swelling and shrinking. In the case of a MoO3/PANI hybrid (Zhang et al., 2017), 3D MoO3 networks are formed through a freeze-drying process, in which the ice acts as a self-sacrificial template, and the different nanosheets are connected by van der Waals and hydrogen bonds. The final 3D MoO3/PANI hybrid networks were achieved by further electropolymerization of PANI onto the MoO3 surface (Figure 8G). Electrochemical impedance characteristics (EIS) measurements demonstrated good electrical conductivity and ion diffusion behavior (Figures 8H,I). The intrinsic structural advantages and the synergetic interaction of the 3D networks make such a hierarchical configuration a promising structure for supercapacitor materials.

It can be seen from the above work that preparing inorganic-organic composite electrode materials by combining 2D TMOs/TMHs with conductive polymers can effectively improve the cycling, mechanical properties, and specific capacitance of the electrode, which can be used as an effective and feasible scheme for improving the electrochemical performance of the electrode of a supercapacitor.

Summary and Perspectives

A 2D TMOs/TMHs-based hierarchical structure combines the advantages of planar conductivity and a large specific surface area, making it an ideal candidate for the assembly of high-performance supercapacitors. To this end, finding new configurations with a hierarchical structure will guide the fabrication of supercapacitor materials with further-improved electrochemical performances. Besides TMOs/TMHs hierarchical structures, the integration of TMOs/TMHs with graphene or conductive polymer to form hierarchical structures has directed the recent steps forward in supercapacitor materials. In TMOs/TMHs-based hierarchical structures, graphene and conductive polymer are the key components for constructing flexible supercapacitors. By optimizing the TMOs/TMHs nanosheet orientation and stacking, electrons/ion transport channels were created, and performance was enhanced in the hierarchical energy storage devices. In summary, hierarchical structures form the prospective blueprint for fabricating high-performance supercapacitors by regulating morphologies and electronic properties.

Although great efforts have been put into supercapacitor materials in terms of the development of novel materials, synthetic technology, and structure engineering, a few problems remain at present. For instance, in TMOs/TMHs/graphene hierarchical structures, the weak interaction forces between capacitive TMOs/TMHs and graphene at the heterostructure interface have been an impediment to improving electrochemical performance. However, very recently, graphene was demonstrated to eliminate the boundary effect and enable electron behavior of the hybrid comparable with that of a single crystal without grain boundary. It is believed that this discovery may inspire fresh research into hierarchical structures using graphene as a component. Given the advantages of conductive polymer, rational design and synthesis of new types of conductive polymers with higher conductivity and stability are highly desirable, as this would pave the way for next-generation supercapacitors with superior flexibility and performance.

Besides assembling hierarchical structures for improvement of supercapacitor performance, attention could be paid to developing new 2D electroactive materials, such as the newly emerging 2D transition metal carbides/nitrides (MXenes), which possess extremely high intrinsic electronic/ionic conductivity. High intercalation capacitance (~1,000 F cm−3) in aqueous electrolytes make these promising electrode materials for the future. Meanwhile, supercapacitor performance is also dependent on the voltage window, which is strictly limited by the electrolyte. Thus, a possible way forward is to increase the working voltage by using green electrolytes with a high electronic conductivity and voltage window, such as ionic liquid electrolytes.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China for Youths (Grant Nos. 21701057, 21601067, 21905147), the Jiangsu Postdoctoral Research Foundation (Grant No. 1701109B), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2017M611708), and the Scientific Research Startup Foundation of Jiangsu University (Grant No. 16JDG063).

References

- Ambade R. B., Ambade S. B., Shrestha N. K., Salunkhe R. R., Lee W., Bagde S. S., et al. (2017). Controlled growth of polythiophene nanofibers in TiO2 nanotube arrays for supercapacitor applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 172–180. 10.1039/C6TA08038C [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Augustyn V., Come J., Lowe M. A., Kim J. W., Taberna P. L., Tolbert S. H., et al. (2013). High-rate electrochemical energy storage through Li+ intercalation pseudocapacitance. Nat. Mater. 12, 518–522. 10.1038/nmat3601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao J., Wang Z., Liu W., Xu L., Lei F., Xie J., et al. (2018). ZnCo2O4 ultrathin nanosheets towards the high performance of flexible supercapacitors and bifunctional electrocatalysis. J. Alloys Compd. 764, 565–573. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.06.085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bao J., Zhang X., Bai L., Bai W., Zhou M., Xie J., et al. (2014). All-solid-state flexible thin-film supercapacitors with high electrochemical performance based on a two-dimensional V2O5∙H2O/graphene composite. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 10876–10881. 10.1039/c3ta15293f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brezesinski T., Wang J., Tolbert S. H., Dunn B. (2010). Ordered mesoporous α-MoO3 with iso-oriented nanocrystalline walls for thin-film pseudocapacitors. Nat. Mater. 9, 146–151. 10.1038/nmat2612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu Y., Sun T., Cai Y., Du L., Zhuo O., Yang L., et al. (2017). Compressing carbon nanocages by capillarity for optimizing porous structures toward ultrahigh-volumetric-performance supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 29:1700470. 10.1002/adma.201700470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J. N., Lotya M., O'Neill A., Bergin S. D., King P. J., Khan U., et al. (2011). Two-dimensional nanosheets produced by liquid exfoliation of layered materials. Science 331, 568–571. 10.1126/science.1194975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranmer A., Baker E., Liesiö J., Salo A. (2018). A portfolio model for siting offshore wind farms with economic and environmental objectives. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 267, 304–314. 10.1016/j.ejor.2017.11.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh T. M., Achour A., Vizireanu S., Dinescu G., Nistor L., Armstrong K., et al. (2014). Hydrous RuO2/carbon nanowalls hierarchical structures for all-solid-state ultrahigh-energy-density micro-supercapacitors. Nano Energy 10, 288–294. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2014.10.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S., Pal S., De S. (2019). Mixed solvent exfoliated transition metal oxides nanosheets based flexible solid state supercapacitor devices endowed with high energy density. New J. Chem 43, 12385–12395. 10.1039/C9NJ03233A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Huang Y., Chen M., Chen X., Li C., Zhou S., et al. (2018). Self-assembly of 3D hierarchical MnMoO4/NiWO4 microspheres for high-performance supercapacitor. J. Alloys Compd. 763, 801–807. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.06.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frackowiak E., Beguin F. (2001). Carbon materials for the electrochemical storage of energy in capacitors. Carbon 39, 937–950. 10.1016/S0008-6223(00)00183-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Song J., Zhu Y., Cao C. (2014). High-performance supercapacitor electrode based on amorphous mesoporous Ni(OH)2 nanoboxes. J. Power Sources 262, 344–348. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gamby J., Taberna P. L., Simon P., Fauvarque J. F., Chesneau M. (2001). Studies and characterisations of various activated carbons used for carbon/carbon supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 101, 109–116. 10.1016/S0378-7753(01)00707-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Cao S., Cao Y. (2017). Hierarchical core-shell nanosheet arrays with MnO2 grown on mesoporous CoFe2O4 support for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 240, 31–42. 10.1016/j.electacta.2017.04.062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S., Sun Y., Lei F., Liang L., Liu J., Bi W., et al. (2014). Ultrahigh energy density realized by a single-layer β-Co (OH)2 all-solid-state asymmetric supercapacitor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 12789–12793. 10.1002/anie.201407836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X., Liu G., Li Y., Teoh W. Y. (2016). Functionalized-graphene composites: fabrication and applications in sustainable energy and environment. Chem. Mater. 28, 8082–8118. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b01447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González A., Goikolea E., Barrena J. A., Mysyk R. (2016). Review on supercapacitors: technologies and materials. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 58, 1189–1206. 10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.249 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon D., Backes C., Higgins T. M., Hughes M., O'Neill A., King P., et al. (2014). Production of molybdenum trioxide nanosheets by liquid exfoliation and their application in high-performance supercapacitors. Chem. Mater. 26, 1751–1763. 10.1021/cm500271u [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K. C., Lin L. Y. (2019). A review of electrode materials based on core–shell nanostructures for electrochemical supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 3516–3530. 10.1039/C8TA11599K [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Xiao X., Jin H., Li T., Chen M., Liang Z., et al. (2017). Rapid mass production of two-dimensional metal oxides and hydroxides via the molten salts method. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–9. 10.1038/ncomms15630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M., Zhang Y., Li F., Zhang L., Ruoff R. S., Wen Z., et al. (2014). Self-assembly of mesoporous nanotubes assembled from interwoven ultrathin birnessite-type MnO2 nanosheets for asymmetric supercapacitors. Sci. Rep. 4:3878. 10.1038/srep03878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Tao J., Meng W., Zhu M., Huang Y., Fu Y., et al. (2015). Super-high rate stretchable polypyrrole-based supercapacitors with excellent cycling stability. Nano Energy 11, 518–525. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2014.10.031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z. H., Song Y., Feng D. Y., Sun Z., Sun X., Liu X. X. (2018). High mass loading MnO2 with hierarchical nanostructures for supercapacitors. ACS Nano 12, 3557–3567. 10.1021/acsnano.8b00621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ida S., Shiga D., Koinuma M., Matsumoto Y. (2008). Synthesis of hexagonal nickel hydroxide nanosheets by exfoliation of layered nickel hydroxide intercalated with dodecyl sulfate ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 14038–14039. 10.1021/ja804397n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X., Hallam P. M., Houssein S. M., Kadara R., Lang L., Banks C. E. (2012). Printable thin film supercapacitors utilizing single crystal cobalt hydroxide nanosheets. RSC Adv. 2, 1508–1515. 10.1039/C1RA01061A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F., Li W., Zou R., Liu Q., Xu K., An L., et al. (2014). MoO3/PANI coaxial heterostructure nanobelts by in situ polymerization for high performance supercapacitors. Nano Energy 7, 72–79. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2014.04.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Li Y., Liu J., Huang X., Yuan C., Lou X. W. (2012). Recent advances in metal oxide-based electrode architecture design for electrochemical energy storage. Adv. Mater. 24, 5166–5180. 10.1002/adma.201202146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Tian K., Wei L., Zhang X., Guo X. (2016). Hierarchical porous microspheres of activated carbon with a high surface area from spores for electrochemical double-layer capacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 15968–15979. 10.1039/C6TA05872H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaji M., Murphy P. J., Williams G. O. (1999). The study of conducting polymers for use as redox supercapacitors. Synth. Met. 102, 1360–1361. 10.1016/S0379-6779(98)01334-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kate R. S., Khalate S. A., Deokate R. J. (2018). Overview of nanostructured metal oxides and pure nickel oxide (NiO) electrodes for supercapacitors: a review. J. Alloys Compd. 734, 89–111. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.10.262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumbhar V. S., Kim D. H. (2018). Hierarchical coating of MnO2 nanosheets on ZnCo2O4 nanoflakes for enhanced electrochemical performance of asymmetric supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 271, 284–296. 10.1016/j.electacta.2018.03.147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Cho M. S., Kim I. H., Nam J. D., Lee Y. (2010). RuOx/polypyrrole nanocomposite electrode for electrochemical capacitors. Synth. Met. 160, 1055–1059. 10.1016/j.synthmet.2010.02.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. J., Sung Y. M. (2012). Synthesis of anatase nanosheets with exposed (001) facets via chemical vapor deposition. Cryst. Growth Des. 12, 5792–5795. 10.1021/cg301317j [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Hu Z., Peng J., Wu C., Yang Y., Feng F., et al. (2014). Ultrahigh infrared photoresponse from core–shell single-domain-VO2/V2O5 heterostructure in nanobeam. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 1821–1830. 10.1002/adfm.201302967 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim Y., Yoon J., Yun J., Kim D., Hong S. Y., Lee S. J., et al. (2015). Correction to biaxially stretchable, integrated array of high performance microsupercapacitors. ACS Nano 9, 6634–6634. 10.1021/acsnano.5b02991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Yu Z., Neff D., Zhamu A., Jang B. Z. (2010). Graphene-based supercapacitor with an ultrahigh energy density. Nano Lett. 10, 4863–4868. 10.1021/nl102661q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Zhang L., Wu H. B., Lin J., Shen Z., Lou X. W. D. (2014). High-performance flexible asymmetric supercapacitors based on a new graphene foam/carbon nanotube hybrid film. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 3709–3719. 10.1039/C4EE01475H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Zhong M., Li J., Pan A., Zhu X. (2015). Few-layer WO3 nanosheets for high-performance UV-photodetectors. Mater. Lett. 148, 184–187. 10.1016/j.matlet.2015.02.088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Yao T., Tan X., Liu Q., Wang Z., Shen D., et al. (2012). Room temperature intercalation-deintercalation strategy towards VO2 (B) single layers with atomic thickness. Small 8, 3752–3756. 10.1002/smll.201201552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Yan J., Guang Z., Huang Y., Li X., Huang W., et al. (2019). Recent advancements of polyaniline-based nanocomposites for supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 424, 108–130. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.03.094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R., Cho S. I., Lee S. B. (2008). Poly(3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene) nanotubes as electrode materials for a high-powered supercapacitor. Nanotechnology 19:215710. 10.1088/0957-4484/19/21/215710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Wang Z., Su Y., Li Q., Zhao Z., Geng F. (2017). Molecularly stacking manganese dioxide/titanium carbide sheets to produce highly flexible and conductive film electrodes with improved pseudocapacitive performances. Adv. Energy Mater. 7:1602834 10.1002/aenm.201602834 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Liang L., Xiao C., Hua X., Li Z., Pan B., et al. (2016). Promoting photogenerated holes utilization in pore-rich WO3 ultrathin nanosheets for efficient oxygen-evolving photoanode. Adv. Energy Mater. 6:1600437 10.1002/aenm.201600437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zhou T., Zheng Y., He Z., Xiao C., Pang W. K., et al. (2017). Local electric field facilitates high-performance Li-ion batteries. ACS Nano 11, 8519–8526. 10.1021/acsnano.7b04617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukatskaya M. R., Dunn B., Gogotsi Y. (2016). Multidimensional materials and device architectures for future hybrid energy storage. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–13. 10.1038/ncomms12647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu W., Yu M., Feng J., Yan W. (2019). Facile synthesis of coral-like hierarchical polyaniline micro/nanostructures with enhanced supercapacitance and adsorption performance. Polymer 162, 130–138. 10.1016/j.polymer.2018.12.037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood N., De Castro I. A., Pramoda K., Khoshmanesh K., Bhargava S. K., Kalantar-Zadeh K. (2019). Atomically thin two-dimensional metal oxide nanosheets and their heterostructures for energy storage. Energy Storage Mater. 16, 455–480. 10.1016/j.ensm.2018.10.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mei J., Liao T., Sun Z. (2018). Two-dimensional metal oxide nanosheets for rechargeable batteries. J. Energy Chem. 27, 117–127. 10.1016/j.jechem.2017.10.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Z., Xu H., Chen Z., She X., Song Y., Wu J., et al. (2018). Self-assembled synthesis of defect-engineered graphitic carbon nitride nanotubes for efficient conversion of solar energy. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 225, 154–161. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.11.041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muzaffar A., Ahamed M. B., Deshmukh K., Thirumalai J. (2019). A review on recent advances in hybrid supercapacitors: design, fabrication and applications. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 101, 123–145. 10.1016/j.rser.2018.10.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Najafpour M. M., Hołynska M., Salimi S. (2015). Applications of the “nano to bulk” Mn oxides: Mn oxide as a Swiss army knife. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 285, 65–75. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T., Montemor M. D. F. (2019). Metal oxide and hydroxide–based aqueous supercapacitors: from charge storage mechanisms and functional electrode engineering to need-tailored devices. Adv. Sci. 6:1801797. 10.1002/advs.201801797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoselov K. S., Fal V. I., Colombo L., Gellert P. R., Schwab M. G., Kim K. (2012). A roadmap for graphene. Nature 490, 192–200. 10.1038/nature11458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang Y., Huang R., Xia X., Ye H., Jiao X., Wang L., et al. (2019). Hierarchical structure electrodes of NiO ultrathin nanosheets anchored to NiCo2O4 on carbon cloth with excellent cycle stability for asymmetric supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 355, 416–427. 10.1016/j.cej.2018.08.142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L., Peng X., Liu B., Wu C., Xie Y., Yu G. (2013). Ultrathin two-dimensional MnO2/graphene hybrid nanostructures for high-performance, flexible planar supercapacitors. Nano Lett. 13, 2151–2157. 10.1021/nl400600x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X., Guo Y., Yin Q., Wu J., Zhao J., Wang C., et al. (2017). Double-exchange effect in two-dimensional MnO2 nanomaterials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 5242–5248. 10.1021/jacs.7b01903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi R., Nie J., Liu M., Xia M., Lu X. (2018). Stretchable V2O5/PEDOT supercapacitors: a modular fabrication process and charging with triboelectric nanogenerators. Nanoscale 10, 7719–7725. 10.1039/C8NR00444G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui X., Lu Z., Yu H., Yang D., Hng H. H., Lim T. M., et al. (2013). Ultrathin V2O5 nanosheet cathodes: realizing ultrafast reversible lithium storage. Nanoscale 5, 556–560. 10.1039/C2NR33422D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salanne M., Rotenberg B., Naoi K., Kaneko K., Taberna P. L., Grey C. P., et al. (2016). Efficient storage mechanisms for building better supercapacitors. Nat. Energy 1, 1–10. 10.1038/nenergy.2016.70 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y., Wang C., He X., Li J., Peng Q., Shi E., et al. (2015). Self-stretchable, helical carbon nanotube yarn supercapacitors with stable performance under extreme deformation conditions. Nano Energy 12, 401–409. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2014.11.048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simon P., Gogotsi Y. (2010). Materials for electrochemical capacitors, in Nanoscience and Technology, 320–329. 10.1142/9789814287005_0033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snook G. A., Kao P., Best A. S. (2011). Conducting-polymer-based supercapacitor devices and electrodes. J. Power Sources 196, 1–12. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2010.06.084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song M. S., Lee K. M., Lee Y. R., Kim I. Y., Kim T. W., Gunjakar J. L., et al. (2010). Porously assembled 2D nanosheets of alkali metal manganese oxides with highly reversible pseudocapacitance behaviors. J. Phy. Chem. C 114, 22134–22140. 10.1021/jp108969s [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Shi Y., Li G., Shen Z., Hu X., Lyu Z., et al. (2018). Numerical analysis of the heat production performance of a closed loop geothermal system. Renew Energy 120, 365–378. 10.1016/j.renene.2017.12.065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staaf L. G. H., Lundgren P., Enoksson P. (2014). Present and future supercapacitor carbon electrode materials for improved energy storage used in intelligent wireless sensor systems. Nano Energy 9, 128–141. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2014.06.028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stankovich S., Dikin D. A., Dommett G. H., Kohlhaas K. M., Zimney E. J., Stach E. A., et al. (2006). Graphene-based composite materials. Nature 442, 282–286. 10.1038/nature04969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto W., Iwata H., Yasunaga Y., Murakami Y., Takasu Y. (2003). Preparation of ruthenic acid nanosheets and utilization of its interlayer surface for electrochemical energy storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 4092–4096. 10.1002/anie.200351691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B., He X., Leng X., Yang J., Zhao Y., Suo H., et al. (2016). Flower-like polyaniline–NiO structures: a high specific capacity supercapacitor electrode material with remarkable cycling stability. RSC Adv. 6, 43959–43963. 10.1039/C6RA02534J [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Li W., Zhang B., Li G., Jiang L., Chen Z., et al. (2014). 3D core/shell hierarchies of MnOOH ultrathin nanosheets grown on NiO nanosheet arrays for high-performance supercapacitors. Nano Energy 4, 56–64. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2013.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Liao T., Dou Y., Hwang S. M., Park M. S., Jiang L., et al. (2014). Generalized self-assembly of scalable two-dimensional transition metal oxide nanosheets. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–9. 10.1038/ncomms4813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Liao T., Kou L. (2017). Strategies for designing metal oxide nanostructures. Sci. China Mater. 60, 1–24. 10.1007/s40843-016-5117-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tao P., Yao S., Liu F., Wang B., Huang F., Wang M. (2019). Recent advances in exfoliation techniques of layered and non-layered materials for energy conversion and storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 23512–23536. 10.1039/C9TA06461C [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Du G., Stahl K., Huang H., Zhong Y., Jiang J. Z. (2012). Ultrathin SnO2 nanosheets: oriented attachment mechanism, nonstoichiometric defects, and enhanced lithium-ion battery performances. J. Phys. Chem. C. 116, 4000–4011. 10.1021/jp300136p [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Wu X., Yuan X., Liu Z., Zhang Y., Fu L., et al. (2017). Latest advances in supercapacitors: from new electrode materials to novel device designs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 6816–6854. 10.1039/C7CS00205J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Zhang L., Zhang J. (2012). A review of electrode materials for electrochemical supercapacitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 797–828. 10.1039/C1CS15060J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Guo J., Wang T., Shao J., Wang D., Yang Y. W. (2015). Mesoporous transition metal oxides for supercapacitors. Nanomater 5, 1667–1689. 10.3390/nano5041667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen P., Ai L., Liu T., Hu D., Yao F. (2017). Hydrothermal topological synthesis and photocatalyst performance of orthorhombic Nb2O5 rectangle nanosheet crystals with dominantly exposed (010) facet. Mater. Des. 117, 346–352. 10.1016/j.matdes.2017.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen S., Liu Y., Zhu F., Shao R., Xu W. (2018). Hierarchical MoS2 nanowires/NiCo2O4 nanosheets supported on Ni foam for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 428, 616–622. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.09.189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H. B., Pang H., Lou X. W. D. (2013). Facile synthesis of mesoporous Ni0.3Co2.7O4 hierarchical structures for high-performance supercapacitors. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 3619–3626. 10.1039/c3ee42101e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Sun X., Zhang N., Xu K., Zhou M., Xie Y. (2013). Layer-by-layer β-Ni (OH)2/graphene nanohybrids for ultraflexible all-solid-state thin-film supercapacitors with high electrochemical performance. Nano Energy 2, 65–74. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2012.07.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q., Lv Y., Dong C., Sreeprased T. S., Tian A., Zhang H., et al. (2015). Three-dimensional micro/nanoscale architectures: fabrication and applications. Nanoscale 7, 10883–10895. 10.1039/C5NR02048D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Zeng Z., Kang J., Betzler S., Czarnik C., Zhang X., et al. (2019). Formation of two-dimensional transition metal oxide nanosheets with nanoparticles as intermediates. Nat. Mater. 18, 970–976. 10.1038/s41563-019-0415-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Qiu W., Wang F., Zhai T., Fang P., Lu X., et al. (2015). Three dimensional architectures: design, assembly and application in electrochemical capacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 15792–15823. 10.1039/C5TA02743H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T., Lim B., Xia Y. (2010). Aqueous-phase synthesis of single-crystal ceria nanosheets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 4484–4487. 10.1002/anie.201001521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan C., Wu H. B., Xie Y., Lou X. W. (2014). Mixed transition-metal oxides: design, synthesis, and energy-related applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 1488–1504. 10.1002/anie.201303971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y., Liang H. (2015). Hierarchical micro-architectures of electrodes for energy storage. J. Power Sources 284, 435–445. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2015.03.069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuksel Y. E., Ozturk M. (2017). Thermodynamic and thermoeconomic analyses of a geothermal energy based integrated system for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energ. 42, 2530–2546. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.04.172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zavabeti A., Ou J. Z., Carey B. J., Syed N., Orrell-Trigg R., Mayes E. L., et al. (2017). A liquid metal reaction environment for the room-temperature synthesis of atomically thin metal oxides. Science 358, 332–335. 10.1126/science.aao4249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Gao L., Gong Y. (2015). Exfoliated MoO3 nanosheets for high-capacity lithium storage. Electrochem. Commun. 52, 67–70. 10.1016/j.elecom.2015.01.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Wang Y., Ma X., Zhang H., Hou S., Zhao J., et al. (2017). Three dimensional molybdenum oxide/polyaniline hybrid nanosheet networks with outstanding optical and electrochemical properties. New J. Chem. 41, 10872–10879. 10.1039/C7NJ02151H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Chu J., Li C., Chen H., Li Q. (2010). A facile route to synthesize the Ti5NbO14 nanosheets by mechanical cleavage process J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 93, 536–540. 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2009.03405.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Z., Wang Y., Cheng T., Lai W. Y., Pang H., Huang W. (2015). Flexible supercapacitors based on paper substrates: a new paradigm for low-cost energy storage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 5181–5199. 10.1039/C5CS00174A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G., Li J., Jiang L., Dong H., Wang X., Hu W. (2012). Synthesizing MnO2 nanosheets from graphene oxide templates for high performance pseudosupercapacitors. Chem. Sci. 3, 433–437. 10.1039/C1SC00722J [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Sun X. (2018). Molecular layer deposition for energy conversion and storage. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 899–914. 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b00145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Xu Y., Jin D., Xie Y. (2011). Polyaniline-intercalated molybdenum oxide nanocomposites: simultaneous synthesis and their enhanced application for supercapacitor. Chem. Asian J. 6, 1505–1514. 10.1002/asia.201000770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M., Xiao X., Li L., Gu P., Dai X., Tang H., et al. (2018). Hierarchically nanostructured transition metal oxides for supercapacitors. Sci. China Mater. 61, 185–209. 10.1007/s40843-017-9095-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X., Ye Y., Yang Q., Geng B., Zhang X. (2016). Hierarchical structures composed of MnCo2O4@MnO2 core–shell nanowire arrays with enhanced supercapacitor properties. Dalton Trans. 45, 572–578. 10.1039/C5DT03780H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G., Xi C., Xu H., Zheng D., Liu Y., Xu X., et al. (2012). Hierarchical NiO hollow microspheres assembled from nanosheet-stacked nanoparticles and their application in a gas sensor. RSC Adv. 2, 4236–4241. 10.1039/c2ra01307j [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Cao L., Wu Y., Gong Y., Liu Z., Hoster H. E., et al. (2013). Building 3D structures of vanadium pentoxide nanosheets and application as electrodes in supercapacitors. Nano Lett. 13, 5408–5413. 10.1021/nl402969r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Li L., Liu J., Wang H., Wang T., Zhang Y., et al. (2018). Structural directed growth of ultrathin parallel birnessite on β-MnO2 for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitors. ACS Nano 12, 1033–1042. 10.1021/acsnano.7b03431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Cao C., Tao S., Chu W., Wu Z., Li Y. (2014). Ultrathin nickel hydroxide and oxide nanosheets: synthesis, characterizations and excellent supercapacitor performances. Sci. Rep. 4:5787. 10.1038/srep05787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]