Abstract

Harmful use of alcohol has serious effects on public health and is considered a significant risk factor for poor health. mHealth technology promotes health behavior change and enhances health through increased social opportunities for encouragement and support. It remains unknown whether these types of applications directly influence the health status of young people in reducing harmful levels of alcohol consumption. The purpose of this systematic review is to examine current evidence on the effectiveness of mHealth technology use in positively influencing alcohol-related behaviors of young people without known alcohol addiction. Relevant articles published from 2005 to January 2017 were identified through electronic searches of eight databases. Studies with interventions delivered by mHealth (social networking sites, SMS and mobile phone applications) to young people aged 12–26 years were included. Outcome measures were alcohol use, reduction in alcohol consumption or behavior change. Eighteen studies met the inclusion criteria. Interventions varied in design, participant characteristics, settings, length and outcome measures. Ten studies reported some effectiveness related to interventions with nine reporting a reduction in alcohol consumption. Use of mHealth, particularly text messaging (documented as SMS), was found to be an acceptable, affordable and effective way to deliver messages about reducing alcohol consumption to young people. Further research using adequately powered sample sizes in varied settings, with adequate periods of intervention and follow-up, underpinned by theoretical perspectives incorporating behavior change in young people’s use of alcohol, is needed.

Keywords: Mhealth, young people, behavior change, alcohol, text messages

Introduction

Globally, harmful use of alcohol has serious effects on public health including liver cirrhosis, cancers and injuries and is considered by the World Health Organization as a significant risk factor for poor health (World Health Organization [WHO] 2015). In 2012, 5.9% of global deaths (3.3 million) were attributed to alcohol consumption (WHO, 2015). Adolescents and young people are more vulnerable to alcohol-related harm than older people. Early initiation and episodes of heavy drinking, more typical of young people, are associated with greater risk of dependence and abuse at later ages and are predictors of poor health later in life (WHO, 2014). The direct and indirect effects of excessive alcohol consumption are of significant public health concern and include lost productivity, physical and mental health problems, increases in crime and violence, motor vehicle accidents and health-care costs. In the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 24.9% of people aged 12 years and over reported binge drinking in the last month (five drinks for males or four drinks for females on any one occasion).

There are a number of evidence-based prevention programs and strategies that can assist young people in reducing binge drinking and the risk of harm and long-term consequences (Vogl, et al. 2009, Fraeyman, et al. 2012, Mason, et al. 2014, Wright, et al. 2016). The use of text messaging has shown some effectiveness in helping young people reflect on their alcohol consumption and in setting goals to reduce their consumption including limiting the number of drinks on one occasion, in one week or the number of risky drinking occasions per month (Carrà et al., 2015; Flaudias et al., 2015; Haug et al., 2013; Jander, Crutzen, Mercken, Candel, & de Vries, 2016; Suffoletto et al., 2016; Weitzel, Bernhardt, Usdan, Mays, & Glanz, 2007). This shift has come about as a direct result of young people’s increasing use of technologies to connect, belong, share and communicate with their peers (Spring, Gotsis, Paiva, & Spruijt-Metz, 2013). The flexibility of mobile platforms (mhealth) provides an opportunity to reach a large number of people at a specific time, has revolutionized the ability to monitor people’s behavior in ‘real-time’ and is commonplace in personal health education (Maher, Ryan, Kernot, Podsiadly, & Kennihan, 2016).

Maher and colleagues (2016) assert that text messaging can be used effectively to promote health behavior change and enhance health through increased social opportunities for encouragement and support. In this context, behavior change is regarded as a reduction in incidence or prevalence of risky alcohol intake amongst young people without known alcohol addiction (Michie, van Stralen, & West, 2011). Text messages are commonly used as forums for advice seeking and sharing of struggles (Cavello et al., 2012; Maher et al., 2016). It remains unknown whether these types of applications can support young people in their decision-making about alcohol consumption or in minimizing risky drinking (Quanbeck, Chih, et al. 2014). Previous systematic reviews have focused on adult populations with alcohol dependence/alcohol-use disorders (Fowler, 2016, Donoghue, Patton, Phillips, Deluca, & Drummond, 2014, Quanbeck, Chih, et al. 2014) and substance abuse more generally (Kazemi et al., 2017). They found that while mobile technology can provide an effective way to administer health interventions, it remained unclear which features of this technology were most effective in preventing risky alcohol consumption and whether those features would be effective in adolescent and younger populations (Fowler, Holt, & Joshi, 2016). This review fills a gap in the literature by examining the effectiveness of mHealth interventions designed specifically to reduce risky alcohol consumption and decrease binge drinking amongst young people without known alcohol addiction.

Interactive technologies addressing alcohol use and behavior change

Smartphones and other interactive technologies allow young people to maintain interpersonal communications with their friends and can be used as a support tool for reducing their alcohol use (Way, Mason, Benotsch, Kim, & Snipes, 2013). In 2010, over 30,000 mobile applications (Apps) had been developed for smartphones covering medicine, driving, education, health research, communication and patient care outcomes (Luxton, McCann, Bush, Mishkind, & Reger, 2011). Few of these Apps address risky alcohol consumption, despite the known benefits of social support in the treatment of alcohol misuse as well as the cost-effectiveness and potential utility of them as tools to reduce problematic drinking (Cohn, Hunter-Reel, Hagman, & Mitchell, 2011; Johnson, Scott-Sheldon, Huedo-Medina, & Carey, 2011; Luxton et al., 2011). The use of Apps is growing in popularity, with some evidence of their usefulness for young people. In a study by Milward et al. (2016), young people aged 18–30 years reported liking the information, feedback and monitoring provided in Apps designed to help reduce harmful drinking.

Gold et al. (2011) used Short Message Service (SMS)/text messaging to educate young people about sexual health and found this was an effective way to disseminate health promotion messages. However, it was unclear if this intervention actually changed health-behavior (Gold et al., 2011). Weaver, Horyniak, Jenkinson, Dietze, and Lim (2013) found that while young people regularly download health-related Apps, their effectiveness remains inconclusive and little is known about their quality and influence over young people’s behavior.

Aim

The purpose of this systematic review of the literature is to examine current evidence on the effectiveness of mHealth technology use in reducing harmful alcohol-related behaviors among young people without known alcohol addiction. Studies included in this review were interventions delivered by mobile technology that aimed to reduce alcohol consumption in non-clinical populations.

Methods

Relevant articles published from 2005 up to, and including, January 2017 where identified through electronic searches of CINAHL, Cochrane, Medline, PsycInfo, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Sociological Abstracts (Proquest). The following search terms and associated wildcard variants were used; Adolescents, young people, youth, young adult and emerging adults, design, Apps, mobile phones, smart phones, SMS, text, hand held devices, application, health, health behavior, alcohol drinking/or binge drinking, alcohol intoxication, influence, intervention, accessibility. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Search terms.

| Mobile Phone Applications | Alcohol Use | |

|---|---|---|

| MeSH terms | Cell phones, Computers, Handheld, Text messaging, Mobile Applications | Alcohol drinking, Alcoholic beverages, Alcoholic intoxication, Alcoholism, Drinking behaviour, Binge drinking, Beer, Wine |

| Textwords | mobile phone* mobile device* cellphone* cell phone* smartphone* smart phone* handheld device* hand held device* iphone* android* SMS MMS text message* |

alcohol* drunk* drink* (binge* excess* heav*,hazard*,binge*,harmful, problem*) intoxicat* |

Selection of studies

A stepped process was used for study selection. The search identified 1,926 articles.

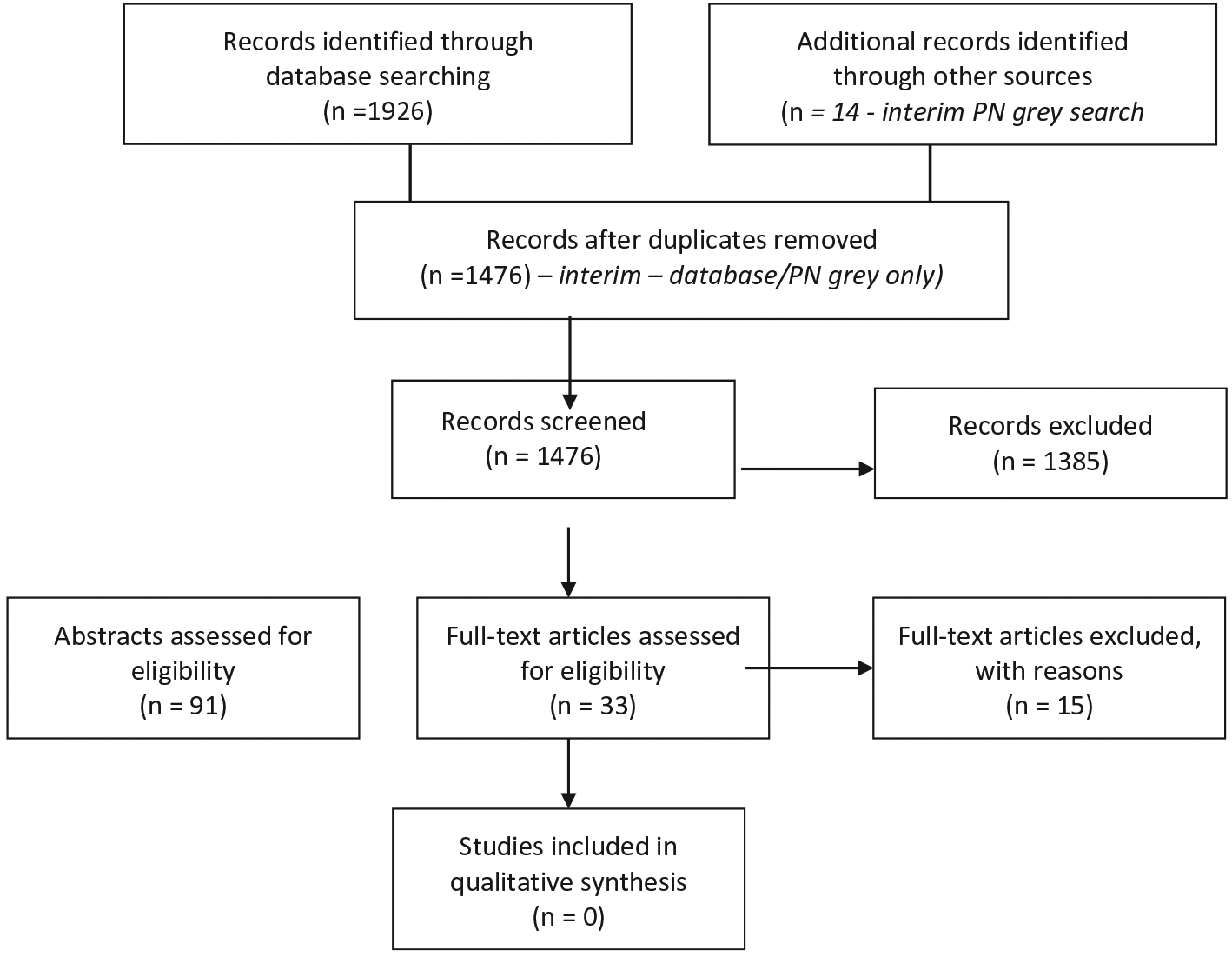

After removing duplicates, 1,476 titles were reviewed by four of the authors (DW, KG, AH & IP) based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Ninety-one abstracts were then reviewed for eligibility and examined against the inclusion/exclusion criteria, leaving 33 full-text articles. Reading of reference lists by the authors resulted in no further inclusions. Authors read the full text of these articles. A further 15 manuscripts were excluded for the following reasons: previous substance abuse (Renner, Natalie, Varsha, & Ross, 2012; Kashdan, Ferssizidis, Collins, & Muraven, 2010); study protocol (Renner et al., 2012; Suffoletto, Callaway, Kristan, Monti, & Clark, 2013); intervention development (Hospital et al., 2016); the primary focus was not alcohol (Irvine et al., 2012; Kazemi, Cochran, Kelly, Cornelius, & Belk, 2014; Reid et al., 2009; Shrier, Rhoads, Fredette, & Burke, 2014); and participants did not meet age criteria and were not considered young people (Kool, Smith, Raerino, & Ameratunga, 2014). Finally, three articles were excluded as they were systematic reviews of online alcohol interventions, designed to decrease alcohol use problematic substance abuse (Tait & Christensen, 2010); and research evidence underpinning online programs for alcohol use (White et al., 2010). Overall, 18 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA process and Table 2 for description of studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Table 2.

Design of Included Studies

| Citation | Sample | Study design | Intervention type | Intervention description | Model or theoretical basis | Duration | Outcome measures | Follow-up | Results | Strengths | Limitations/comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balsa et al. (2014) | 359 adolescents in 9th and 10th grade in 10 private schools; Uruguay | Evaluation | Website SMS and email messages | 2-h workshop, access to website (COLOKT) with weekly updates, resources forums, surveys, 8 emails and 7 SMS | None stated | 3 months | Demographics, Socio Economic Status, social networks, internet use, alcohol use, knowledge and misperceptions | Participation influenced by prior heavy alcohol use and time Periodic reminders sent by email and SMS improved participation Participation could be improved with longer, mandatory intervention | Explores actions associated with participation | Low participation rate Not generalisable Self-reporting No control group Alcohol consumption not measured at follow-up | |

| Bannink et al. (2014) | 1702 adolescents aged 15–16 years; Holland | 3-armed Cluster RCT Ehealth4Ut h n=533 Ehealth4Ut h +consultation n=554 Control n= 615 | Tailored web-based messages | 45 min baseline questionnaire to assess health risk behavior and well-being Tailored web-based messages based on questionnaire with links to resources Motivational interviewing | None stated | 9 months | At baseline and follow-up: Health behaviors measured included frequency and amount of alcohol consumption and becoming drunk Follow-up only: emotional and behavioral problems using Youth Self-Report | 4 months | No difference between groups in alcohol consumption Ethnicity and gender did not effect alcohol consumption | RCT Large sample size | Not generalizable Self-reporting Potential overlap between intervention and control groups |

| Carra et al. (2015) | 590 young people aged 18–24; Italy | Quasi-experiment al study, pre and post-test design without control group | App | Participants downloaded App D-ARIANNA on their phone, were contacted after 14 days to report binging Questionnaire | Substance Use Risk Profile Scale | 2 weeks | Compare binge drinking 2 weeks before and after using the app Risk factors; cannabis use, recent binging, interest in discos and parties, smoking, male, drinking onset < 17, parental alcohol misuse, younger age, peer influence, impulsivity Protective factors; volunteering, school proficiency | 2 weeks | e-health App D-ARIANNA effective reducing binge drinking (37% vs 18%) Convenient and affordable for young people | Large sample size representative sample D-ARIANNA encouraged awareness of negative consequence s of risky drinking and helped deliver preventative messages | Lack of control group Short follow-up time Not generalizable Hawthorne observer effect Self-reporting |

| Crockett et al. (2013) | 522 young people aged 12–16; Australia | Evaluation using Qualitative methods | SMS | Stage I- every 4 weeks 20 people asked about appropriateness of questions, relevance and reach. Next round of SMS adjusted Stage 2- end of the project, 19 participated, focus group included | Participator y Learning in Action model | 5 months | Qualitative study asked about; recruitment methods, effectiveness of SMS to learn about issues, content, relevance and impact of the messages | Every 4 weeks and at 5 months | Messages effective for content, timing, language, relevance Stage l- only 9/ 20 understood the messages about alcohol Participants gained new knowledge Stage2- SMS technology effective and appropriate | Participatory design Messages forwarded to family and friends | Small number in evaluation Hard to evaluate alcohol component only Quantitative measures would add rigor SMS is an effective tool for health messages; convenient, cost effective, anonymous, accessible and relevant for young people otherwise hard to reach |

| Flaudias et al. (2015) | 651 students, mean age 22.2; France | Ecological study with 3 groups Facebook, Paired Facebook, Control | Website Facebook and SMS | Pre and post-test survey questionnaire with control over three periods. | None stated | 3 months Then 2 years | Period 1 (registration); alcohol consumption during festive moments. Period 2 (3 months later); alcohol consumption, ‘party representations’. Period 3; same questions plus an SMS of 10 propositions to test memory. | 3 months | Significant reduction in association of alcohol with festive ‘moments’ in Facebookers and Paired Facebookers and amount of alcohol consumed, but not the control group | Positive behavioral outcome observed | Control group uncompensated (less motivated). Participants had to be receptive to preventative messages |

| Fraeyman et al. (2012) | 3,500 college and university students; Belgium | Evaluation Mixed methods Questionna ire and 5 focus groups (n = 34) | Website | Website contained Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) questionnaire, Personal feedback, refer to counsellor | Theoretical Model of Change | 1 year | Questionnaire; demographics, participation, problematic alcohol use Focus groups discussed experiences, Impressions and effects of the website | None | Intervention positively received, willingness to seek help in high- risk group, motivated to think more about alcohol use | Good sample size | Intervention did not motivate students to change behavior |

| Gajecki et al. (2014) | 1932 university students; Sweden | RCT 3 groups Promillekoll (n = 643) PartyPlann er (n = 640) Control group (n = 649) | Apps | Promillekoll user registers alcohol consumption in real- time with display of current eBAC (blood alcohol concentration) | Webbased interventio ns shown to reduce student’s alcohol intake. | Baseline assessment follow-up question naire at 7 weeks | quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption (DDQ), eBAC, weight, gender Widmark formula used The AUDIT determined problematic drinking and severity Self-report data were collected to assess app usage. | 7 weeks | Promillekoll, associated with more drinking occasions in 1 week. eBAC feedback alone not effective in reducing consumption. Males more affected by increase in drinking frequency. PartyPlanner, no impact on drinking | Smart phone applications can make brief interventions available to large numbers Control group was used | Difficult to compare apps as they differed in design and presentation and the Promillekoll app had been previously available for 5 months. Attrition rates in the two intervention groups differed significantly and this influenced results. |

| Haug et al. (2013) | 364 students aged 16–19; Switzerland | A longitudinal pre and poststudy design (1) non-risk, (2) low-risk, (3) high-risk, |

Web and SMS | Individual feedback about drinking pattern compared to age and gender norms Tailored SMS over 3 months to each risk group Generalised Estimating Equation analyses examined longitudinal outcome criteria | Automated computer program | 12 weeks | Presence and frequency of risky drinking over 30 days (0–2, >2) Number of standard drinks in typical week, Maximum number drinks on an occasion in 30 days Alcohol-related problems in last 3 months | 3 months | High completion (94%) Statistically significant decrease in number of persons with at least one RSOD occasion in study period (76% vs 68%), decrease in number of persons with more than two occasions in the last months | Study group included young people from lower educational backgrounds | No control group Statistical uncertainty |

| Jander et al. (2016) | 2,649 students aged 15–19; Holland | Cluster RTC Intervention 1622 Control n = 1027 | Web based computer game | Baseline assessment collected demographic data and alcohol use A computer game was played where students received tailored motivational messages to discourage future drinking Follow-up questionnaire | The I-Change Model; attitude, social norms, perceived pressure, self-efficacy | Three game sessions | Binge drinking Excessive drinking Weekly consumption | 4 months | Reduced binge drinking in 15 and 16 year olds Interaction effect found between excessive drinking and education level and between weekly drinking and age. No significant subgroup effect for both interaction effects Prolonged use of intervention associated with stronger effects for binge drinking | Large sample size Target group consulted in development of intervention | Low adherence rate (31%) Intervention and control groups differed on baseline drinking |

| Mason et al. (2014) | 18 students aged 18–23 years; United States | RCT Interventio n n= 10, Control n = 8 | SMS | Baseline assessment Participants received four to six tailored SMS messages daily for 4days, each requiring a response. Follow-up after intervention Additional support could be requested | Motivation al interviewin g principles and social network counselling | 4 days | Substance use; 10-item AUDIT; 12-item Drinking Expectancy Questionnaire; Readiness to change | 1 month | Readiness to change increased for intervention group, decreased for control group. Nonsignificant trends suggested increased confidence to change drinking behavior and intention to reduce alcohol use in intervention group | Focus on problem drinkers | Small sample size (pilot study) small response rate (8%) may reflect self-selection bias short follow-up period (1 month) intervention and control groups differed on baseline drinking |

| Moore et al. (2013) | Study 1; 82 University students and non-students; United Kingdom Study 2; 87 | Feasibility study Qualitative interviews Study 2; RCT Interventio n and control | SMS | Study 1; Participants received daily SMS requesting consumption data for previous day and qualitative study to determine feasibility for using SMS in surveillance. Study 2; RCT where participants in experimental group received SMS estimate of alcohol expenditure during previous month. | None stated | 157 days | Compared measures of hazardous consumption with self-reporting alcohol use Association between events and consumption Thematic analysis of qualitative data about feasibility and barriers to surveillance using SMS | Not stated | Greater consumption on Fri, Sat, Wed and celebratory events. SMS was acceptable and private, preferred over email and web based methods. | RCT suggests simple SMS intervention might be effective in reducing alcohol consumption in future trials | Small sample Selection bias |

| Riordan, Conner et al. (2015) | 130 Freshman year students, aged 18–27; New Zealand | RCT EMA-EMI intervention (n =) EMA control (n =) | SMS | Ecological momentary intervention/ advice using a mobile device. Control group received SMS messages in Orientation Week and weekly in first semester. Participants reported number of drinks consumed day before. Intervention group received EMA messages and one nightly EMI message, with health or social consequence of alcohol use, in Orientation Week. | Motivation al interviewing principles and social network counseling | Orientation week | Use of standard drinks Preuniversity alcohol consumption in a typical week, in Orientation week and during the academic semester | Academic semester | Women in the intervention group consumed significantly fewer drinks during orientation week and on weekends in the semester The EMI did not reduce men’s drinking. | Focused on event specific interventions (known risk period) Real-time advice | High attrition Sampling bias Didn’t use matched controls or a ‘noassessment’ control |

| Strohman et al. (2016) | 58 university students aged 18–22; United States | RCT Interventio n n = 29 Control n = 29 | Website | Alcohol-wise intervention delivered by computer with motivation enhancement strategies to reduce students’ likelihood of engaging in risking drinking | Not stated | Intervent ion group 90 minutes initial, 90 minutes at follow-up, total 3 h. Control group 1.5 h total. | Drinking days, peak number of drinks in one sitting, average BAC, alcohol expectancies, perceptions of drinking norms, negative consequences of alcohol use | 30 days | No significant changes over time in alcohol expectancies in either group. Intervention group; freshman and sophomores showed significant reduction in number of drinks and BAC. No effect for juniors or seniors Intervention group reported more accurate estimate of drinking norms at follow-up. | First RCT on widely used program; some evidence of effectiveness for underclassmen | Participant attrition Small sample size Limited gender and racial diversity Duration of follow-up Self- report measure |

| Suffoletto et al. (2016) | 224 Undergraduates; United States | Analysis of secondary data | Text Messaging | Students who violated alcohol policy completed in-person sessions and enrolled in 6-week SMS program Thursday messages asked about intentions to drink and agreement to commit to drinking limit. Sunday asked to report highest number of drinks on a single occasion on the weekend and received feedback. | Theory of Planned Behavior | 6 weeks | Response to Thursday SMS; plan to drink over the weekend, commit to goal to limit drinks Sunday SMS; maximum drinks at one occasion over the weekend and any episode of weekend binge drinking. | 90% of SMS queries completed Weekend binge drinking decreased over 6 weeks Commitment to a goal was associated with less alcohol consumption. Men had greater reductions when they committed to a goal. | SMS messaging may be a feasible and effective booster strategy. | Single site All received in-person sessions, so effects cannot be separated No comparison condition. Possible seasonal confounding No info on non-gender moderators. External validity of findings not possible. | |

| Vogl et al. (2009) | 1466 high school students aged 13 years; Australia | Cluster RCT Intervention; computerized prevention program (n = 611) Control; usual class (n = 855) | Computer delivered drama | Six lessons aimed at decreasing alcohol misuse. Topics include; social pressure, alcohol-free activities, advertising, decision-making, emergency actions, recovery. Control group received the usual state education re alcohol. | None stated | During the school year | Change in knowledge, alcohol use, alcohol- related harms and alcohol expectancies | baseline 6 and 12 months | Intervention more effective in informing safer drinking choices and decreasing social expectation. For girls; effective in decreasing average alcohol consumption, alcohol-related harms and frequency of drinking to excess. For males; behavioral effects not significant. | Cluster RCT design. Innovative computer-delivered program | Attrition of high risk students limits validity of findings Some control group teachers limited normative component of the program, considered key to program success Self-report measures |

| Weitzel et al. (2007) | 40 college students aged 18 years or above; United States | RCT Intervention; handheld computer-plus-messaging (HHM) (n = 20) Control; handheld-only (HH) (n = 20) | SMS | Baseline survey to assess drinking behavior Intervention group received daily tailored messages about avoiding negative consequences, recorded consumption daily. If alcohol consumed, asked about amount, type, consequences Control group; completed daily | 2 weeks | Anticipated consequences of drinking, confidence of avoiding negative consequences Behavioral variables; i) total drinks in study period, 2) number of drinking days, 3) drinks per day, 4) negative consequences, 5) negative consequences per day Follow-up survey on experience and attitudes. | 2 weeks | Participants in HHM reported drinking significantly fewer drinks per drinking day and lower expectancies of getting into trouble as a result of alcohol consumption | Randomisation Real-time, tailored messages Use of SMS reminders to complete surveys | Small, convenience, sample Self-reporting Reliability and validity of daily surveys may not have been determined ACES and ASES need to be further validated 40 word messages are short and were not formally pretested Costs of equipment and personnel Short study period Low-dose intervention | |

| Wright et al. (2016) | 42 participants aged 18–25 years; Australia | Participator y design; workshop, evaluation by survey and in- depth interviews | SMS | Participants competed initial questionnaire then hourly SMS sent until 2 am Tailored SMS was sent in reply. Follow-up questionnaire |

Ecological Momentary Assessment | 2 weeks | Pre survey; alcohol consumption, planning, eaten dinner, spending, message to self Hourly survey; location, alcohol consumption, spending, mood, perceived drunkenness Next day survey; further consumption, spending, total recall of standard drinks and spending, adverse events Evaluation; acceptability, feasibility, participant experience | One week after | 89% response rate Participants focused on their drinking often for the first time 98% comfortable with regular reporting and sharing sensitive information including adverse events Mobile phones suitable for data sharing, if not intrusive | Participatory design Real-time data collection and tailored feedback reducing recall bias | Didn’t test effectiveness of the intervention Small sample Self-reporting Recall bias Participants involved in both design and study may have felt heavily invested and supported intervention more than if a new group tested and evaluated. |

Inclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they examined the impact of mHealth interventions for reducing alcohol consumption among young people between the ages of 12 and 26 years without known alcohol addiction. Studies involving young people with alcohol dependency or a pre-existing condition related to alcohol were not included. The studies had to include an mHealth intervention delivered via website or mobile technology (including text messages, Apps on smartphone devices, iPad and internet delivered treatment).

Data synthesis and analysis

All articles included in the review were appraised for quality using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist (Better Value Healthcare, 2017) individually by each of the authors. Classification of evidence was as follows; randomized control trials, randomized comparison trials, controlled trials without randomization, cohort or case-control studies, comparison without an intervention and descriptive studies. Overall study quality was high.

Results

Description of studies – settings

Our findings revealed a range of recruitment settings for mHealth interventions. One study used a clinical location for recruitment (an Emergency Department) (Suffoletto, Callaway, Kristan, Kraemer, & Clark, 2012) and three used community environments including a festival and shopping centers (Crockett et al., 2013), live music events and pubs (Carrà et al., 2015), and an outdoor music festival (Wright, Dietze, Crockett, & Lim, 2016). Schools (n = 5) were the main locations used for young people between the age of 12–19 (Balsa, Gandelman, & Lamé, 2014; Bannink et al., 2014; Haug et al., 2013; Jander et al., 2016; Vogl et al., 2009). The remaining studies (n = 9) recruited from university settings (Fraeyman, Van Royen, Vriesacker, De Mey, & Van Hal, 2012; Gajecki, Berman, Sinadinovic, Rosendahl, & Andersson, 2014; Mason, Benotsch, Way, Kim, & Snipes, 2014; Strohman et al., 2016; Suffoletto et al., 2016; Weitzel et al., 2007), in Freshers Week/Orientation week (Moore et al., 2013, Riordan, Conner, et al. 2015) or through established University associations (Flaudias et al., 2015).

There was considerable variation in the countries where studies were conducted. Of the 18 articles, eight were from Europe; Holland (Bannink et al., 2014; Jander et al., 2016), Italy (Carrà et al., 2015), France (Flaudias et al., 2015), Sweden (Gajecki et al., 2014), Belgium (Fraeyman et al., 2012), Switzerland (Haug et al., 2013) and the United Kingdom (Moore et al., 2013), five were from the United States (Moore et al., 2013; Strohman et al., 2016; Suffoletto et al., 2012, 2016; Weitzel et al., 2007), three were from Australia (Crockett et al., 2013; Vogl et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2016), one was from New Zealand (Riordan, Conner, et al. 2015) and one from Uruguay, South America (Balsa et al., 2014).

Type of intervention

The studies used a variety of interventions. Text messages (SMS) were the most commonly used intervention (n = 8) (Weitzel et al., 2007; Suffoletto et al., 2012; Crockett et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2013; Mason et al., 2014, Riordan, Conner, et al. 2015; Suffoletto et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2016). Seven studies used websites to deliver interventions (Balsa et al., 2014; Bannink et al., 2014; Flaudias et al., 2015; Fraeyman et al., 2012; Haug et al., 2013; Jander et al., 2016; Strohman et al., 2016). Two interventions included Apps; D-ARIANNA (Carrà et al., 2015), Promekill and Party Planner (Gajecki et al., 2014). One study used a dramatized story to convey safe drinking messages (Vogl et al., 2009). Six studies used secondary techniques such as text messages, interviews, or email reminders to follow-up participants or to support the primary intervention (Balsa et al., 2014; Crockett et al., 2013; Flaudias et al., 2015; Fraeyman et al., 2012; Haug et al., 2013; Wright et al., 2016).

Comparison and control groups

Of the 18 articles reviewed, six (n = 6) randomly allocated participants into two groups to test an intervention (Weitzel et al., 2007; Vogl et al., 2009; Crockett et al., 2013; Balsa et al., 2014, Riordan, Conner, et al. 2015; Strohman et al., 2016). Of these studies, four administered a self-report survey at baseline and, based on the survey results, participants were chosen to be part of the intervention (Weitzel et al., 2007; Vogl et al., 2009; Balsa et al., 2014, Riordan, Conner, et al. 2015). Crockett et al. (2013) recruited young people at an outdoor music festival and then randomly assigned participants to the intervention (Crockett et al., 2013), and Strohman et al. (2016) used a wait-list control group.

Two studies randomly allocated participants into three groups. Flaudias et al. (2015) used Facebook, and randomly assigned participants to Facebook, Facebook and text messages, and Paired Facebook use (Flaudias et al., 2015). Haug et al. (2013) used a non-specified online assessment tool to collect data describing demographics, alcohol consumption and drinking behavior (Haug et al., 2013).

Two studies used a three-armed cluster Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) (Bannink et al., 2014; Gajecki et al., 2014). Jander et al. (2016) used a cluster RCT (Jander et al., 2016), and Suffoletto et al. (2012) used a pilot RCT. Gajecki et al.’s (2014) trial included two different Apps, one by the Swedish government (Promekill) and one of their own designs called Party Planner. One group was designated Promekill, the other Party Planner, and the third received no intervention (Gajecki et al., 2014). Bannink et al. (2014) tested an E-Health-4-U intervention (web-based tailored messages), with follow-up consultation and control. The control group received no intervention (Bannink et al., 2014). Jander et al. (2016) used a cluster RCT in which participants were assigned to the experimental or the control condition. Suffoletto et al. (2012) used the AUDIT-C tool to identify ‘hazardous’ drinkers. The intervention group was sent text messages and supported to set goals, an assessment group was sent text messages requiring feedback and the control group only received text messages (Suffoletto et al., 2012). Mason et al. (2014) and Moore et al. (2013) used pre-test selection (Mason et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2013) whilst Carrà et al. (2015), Wright et al. (2016) and Fraeyman et al. (2012) used no control (Carrà et al., 2015; Fraeyman et al., 2012; Wright et al., 2016). Lastly, Suffoletto et al. (2016) used secondary data analysis to measure the success of an intervention on a college campus.

Intervention length, design and follow-up

There was substantial variation in the length of interventions, time carried out and follow-up, with the shortest intervention being 2to 3 h and the longest being 1year. This variation made it difficult to compare and contrast each study, therefore we will discuss these interventions, as web-based designs, text message interventions and Apps.

Web-based interventions

Eight studies used web-based interventions (Balsa et al., 2014; Bannink et al., 2014; Fraeyman et al., 2012; Haug et al., 2013; Jander et al., 2016; Mason et al., 2014; Strohman et al., 2016; Vogl et al., 2009). Both Balsa et al. (2014) and Haug et al. (2013) supported their web-based intervention by email and text message reminders. The prescribed amount of interaction via web-based interventions ranged from 2 hto 1year. Balsa et al.’s (2014) intervention was delivered in a school and lasted for 2 h, while Fraeyman et al. (2012) and Jander et al. (2016) followed participants for up to one year after their initial assessment.

Both Bannink et al. (2014) and Mason et al. (2014) used a website as a platform to assess the drinking levels of young people, and then used a follow-up consultation. Bannink et al. (2014) used a website called E-Health-4-U. Pre-post questionnaires developed by the research team to self-report health behaviors were used at baseline and follow-up (Bannink et al., 2014). Fraeyman et al. (2012) developed a website intervention, which was available for 1 year. Young people self-assessed their alcohol use using the AUDIT-C and were then directed to specific areas on the website where they received immediate, personalized feedback and suggestions for further action. This program was available for 1 year and evaluation of the website, and its resources was conducted using five focus groups (Fraeyman et al., 2012). In contrast, Haug et al. (2013) used a website aimed at reducing risky drinking levels. Participants were supported with individualized SMS’s based on four key elements: gender, age, number of standard drinks in the past week, and frequency of risky drinking in the past 30 days (Haug et al., 2013).

Jander et al.’s (2016) website intervention was game based, called Alcohol Alert. During the game, participants were asked questions based on a few different models; the I-Change model (de Vries et al., 2003), the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein, 1980), the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1986), the Health Belief Model (Janz & Becker, 1984), the Precaution Adoption Model (Weinstein, 1988), and the Transtheoretical Model of Change (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). After this assessment, the experimental group received computer-based tailor-made feedback (Jander et al., 2016). A computer-based cartoon drama called CLIMATE was used by Vogl et al. (2009) to deliver their intervention over six sessions. The SHARP survey instrument, consisting of 105 items, was completed by participants at baseline, post-intervention, 6 months and at 1 year (Vogl et al., 2009).

Mason et al. (2014) asked participants to undertake a web-based assessment using the AUDIT-C; Brief Symptom Inventory; Drinking Expectancy Questionnaire and Stage of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale. Researchers then used a twenty-minute motivational interview and followed up with four to six text messages daily for four days (Mason et al., 2014). Strohman et al. (2016) used a computer-based intervention called Alcohol-Wise, which contained six modules. Participants were then followed up one month later with their eCHECKUP survey.

Text message interventions

Both Crockett et al. (2013) and Moore et al. (2013) used text messages as their primary intervention. Crockett et al. (2013) sent text messages for 5weeks; then assessed this intervention using qualitative interviews. Moore et al. (2013) sent text messages to test the validity of self-reporting of alcohol consumption amongst participants. They also used the AUDIT-C and the Fast Alcohol Screening Test (FAST) to determine baseline alcohol use. Each day participants were asked to text their alcohol use. The feasibility of this intervention was assessed using qualitative interviews (Moore et al., 2013).

The AUDIT-C was used by Suffoletto et al. (2012) to gain baseline data. Participants were then randomized and asked to set goals. Text messages were sent using the Pittsburgh Alcohol Reduction through Text Messaging (PART) tool (Suffoletto et al., 2012). In another study, Suffoletto et al. (2016) analyzed secondary data from a mandatory program given to young people who violated college alcohol rules. These young people were required to undergo a 2-h workshop, and consultation followed by 6weeks of automated two-way text messages named Panther TRAC. The goal of Panther TRAC was to allow young people to set goals, commit to a drinking limit, report their alcohol use and receive messages of support (Suffoletto et al., 2016).

Riordan, Conner, et al. (2015) used an ecological momentary intervention (EMI) during a University Orientation (O) week. Text messages were sent each night of O week, promoting prevention. Prior to receiving an text, participants were given information on standard drinks and were then asked to fill out a questionnaire detailing their alcohol use. The intervention was assessed using timeline feedback, and self-reporting of alcohol use (Riordan, Conner, et al. 2015). Wright et al. (2016) used text messages, links to surveys and Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) as their mHealth intervention. EMA is where mobile technology is incorporated into psychosocial and health behavior treatments. The intervention lasted for 1week and effectiveness was analyzed using focus groups (Wright et al., 2016).

In the study by Weitzel et al. (2007) participants used handheld computers to complete daily surveys about their drinking behavior; they then received tailored text messages on the consequences of alcohol use (Weitzel et al., 2007). Flaudias et al. (2015) used the social networking site Facebook and sent text messages to young people for 5months.

App interventions

Apps were used in two studies; Carra et al. (2015) developed an App named D-ARIANNA, which was self-administered for 2weeks. Students were asked to participate in a questionnaire, developed by the researchers, to identify risk and protective factors prior to using the App (Carrà et al., 2015). Gajecki et al. (2014) used two Apps as interventions (Promekill and Party Planner) and were followed up after 5weeks. The AUDIT-C was used to identify the number of participants who drank at risky levels (Gajecki et al., 2014).

Intervention effectiveness

The effectiveness of interventions varied across the 18 studies, with 10 studies reporting some effectiveness (Carrà et al., 2015; Flaudias et al., 2015; Fraeyman et al., 2012; Haug et al., 2013; Jander et al., 2016; Mason et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2013; Suffoletto et al., 2012, 2016; Weitzel et al., 2007), three reporting mixed results (Vogl et al., 2009, Riordan, Conner, et al. 2015; Strohman et al., 2016), and two reporting no effectiveness (Bannink et al., 2014; Gajecki et al., 2014). Three studies were evaluations and did not test interventions (Balsa et al., 2014; Crockett et al., 2013; Wright et al., 2016). Again, to the large variation in outcomes, we have divided the studies into effective, mixed results, not effective and other.

Effective

Carra et al. (2015) reported success in the delivery of their App D-ARIANNA with young people reporting increased knowledge of the risks of binge drinking, and the majority of users stating the App was easy to use (Carrà et al., 2015). Flaudias et al. (2015) showed a reduction in the link between alcohol and ‘partying’ in both intervention groups, but not the control. The declared number of glasses of alcohol consumed at festive moments diminished between the beginning and the end of the program for the intervention groups. Furthermore, the link between a reduction in alcohol consumption and festive moments was influenced by the number of days since registration and not by age or number of text messages received (Flaudias et al., 2015). Fraeyman et al. (2012) found use of a web-based questionnaire, tailored feedback, and referrals to counseling was well-received, and participants were more motivated to consider their alcohol use. Those in a ‘high risk’ group were willing to seek help (Fraeyman et al., 2012). Haug et al. (2013) found a decrease in the number of persons engaging in risky single episode drinking and a decrease in the number of persons with more than two occasions of risky drinking in the last month (Haug et al., 2013). Jander et al. (2016) found that their web intervention was effective in reducing risky drinking among young people aged 15 and 16 years when they participated in at least two intervention sessions. Mason et al. (2014) found participant’s readiness to change increased after receiving tailored text messages along with greater confidence to change drinking behavior. Moore et al. (2013) found that for surveillance, text was acceptable, private and preferred over email and web-based methods and so might be effective in reducing alcohol consumption in future trials (Moore et al., 2013). Suffoletto et al. (2012) found a reduction in heavy drinking days and fewer drinks per drinking days with participants who received SMS messages and set goals being less likely to repeat heavy drinking days (Suffoletto et al., 2012). In 2016, Suffoletto et al. found weekend risky drinking decreased for students who violated an alcohol policy after participating in a face-to-face session and a 6-week program of text messages that included goal setting. Commitment to the goal was associated with less alcohol consumption, with men having greater reductions than women (Suffoletto et al., 2016). Weitzel et al. (2007) found students who used a hand-held computer to receive tailored text messages about negative consequences of alcohol consumption reported significantly fewer drinks per drinking days and lower expectancies of getting into trouble as a result of their consumption (Weitzel et al., 2007).

Mixed results

Riordan, Conner, et al. (2015) had mixed results from their intervention. They found that overall there was no difference between EMA and EMA-EMI (Ecological Momentary/Advice interventions) conditions for pre-university drinking, Orientation Week drinking, or semester weekend drinking. However, women in the EMA-EMI condition compared with women in the EMA-only condition consumed significantly fewer drinks during O Week and weekend drinks during the first semester. There was no difference between men’s drinking in either condition, at any time (Riordan, Conner, et al. 2015). Strohman et al. (2016) also had mixed results. At follow-up, freshman and sophomore students in the intervention group showed a significant reduction in peak number of standard drinks and blood alcohol concentration, but the effect was not observed for juniors and seniors. The study provides evidence for the short-term usefulness of a web-based intervention in reducing drinking among underclassmen (Strohman et al., 2016). Vogl et al.’s (2009) result from a school-based, computer-driven drama differed between genders. For girls aged 13 years, there was a decrease in alcohol consumption, alcohol-related harms and frequency to drink to excess. Behavioral effects for boys were not significant (Vogl et al., 2009).

Not effective

Two studies did not produce an intervention effect. Bannink et al. (2014) could not demonstrate that web-based health messaging was effective for young people as participants did not perceive the messages they received as personally relevant (Bannink et al., 2014). Gajecki et al. (2014), who used two different Apps, showed that Apps can be used to deliver information about alcohol. However, their results were inconclusive about the effectiveness of Apps to reduce alcohol consumption. The results from one App (Promekill) found that young people increased their alcohol consumption, whereas the other App (Party Planner) did not appear to have any impact on young people’s drinking (Gajecki et al., 2014).

Other

Two studies were evaluations and did not measure the effectiveness of an intervention. Balsa et al. (2014) focused on low participation in a web-based school program and found it could be improved using periodic reminders, a longer intervention and by making it mandatory (Balsa et al., 2014). Crockett et al. (2013) evaluated the feasibility of using text messages to convey harm-reduction messages. While messages were effective for content, timing and language, less than half understood the messages specific to alcohol (Crockett et al., 2013). Wright et al.’s (2016) feasibility study found hourly text messages to collect data through online questionnaires and tailored feedback delivered over one night out was acceptable to young people. However, the authors acknowledge that comprehensive testing and evaluation are now required (Wright et al., 2016).

Discussion

This review supports the idea that an mHealth approach provides an affordable method to disseminate information to young people (Moore et al., 2013; Gajecki et al., 2014; Mason et al., 2014; Carrà et al., 2015; Flaudias et al., 2015, Riordan, Conner, et al. 2015). mHealth interventions can be convenient, accessible, relevant, anonymous (Crockett et al., 2013; Flaudias et al., 2015) and portable for young people (Moore et al., 2013, Riordan, Conner, et al. 2015). Young people are willing to share or forward text messages, which supports the assertion that text messages can be used to reach a wider population than the initial message recipients (Crockett et al., 2013). Text messaging has no geographical boundaries and is accessible at all times (Flaudias et al., 2015). Haug et al. (2013) and Moore et al. (2013) reported mHealth interventions as useful ways of collecting individual, real-time data on alcohol use.

Of the 18 studies included in this review, two studies by Suffoletto et al. (2012, 2016), argued that brief interventions have the potential to produce behavior change, but larger studies are needed to assess efficacy. They also claimed that a text message program could be useful as a booster for helping young people reduce weekend binge drinking. Whereas Wright et al. (2016) asserted that for mHealth interventions to be successful a continual process of evaluation needs to take place to ensure that young people’s ideas are implemented into each new set of messages, leaving them feeling valued and included in the process.

Characteristics of effective mhealth interventions to reduce alcohol consumption

Tailored messaging and prevention messages at a younger age were found to be effective. In addition, findings show that interventions need to be interesting and interactive to hold the attention of young people. Studies that used static educational materials were not successful (Balsa et al., 2014). Similarly, Bannink et al. (2014) found that tailored messages could be improved further, claiming that if messages were more personally relevant, they would be more likely to be effective (Bannink et al., 2014). Both Jander et al. (2016) and Strohman et al. (2016) found that prevention messages had a greater impact for those at the beginning of their ‘drinking career’ (Jander et al., 2016; Strohman et al., 2016). Strohman et al. (2016) assert that prevention efforts should be concentrated in the first 2 years of college whereas other methods, not stipulated in this review, may be needed for those with a longer history of alcohol consumption.

Overall this review revealed that there was great variability in the study’s methodology, participant characteristics, including sample size and diversity, setting, use of theoretical basis, duration of the interventions and follow-up period. This variability resulted in difficulties in a comparative analysis of the effectiveness of the interventions and of their outcomes.

Generalizability of any of the results is limited. Collectively, the studies do suggest the acceptability of mHealth technologies among young people; however, it was difficult to determine which type of mHealth delivery system was statistically significant in changing outcomes (text, Apps, web-based, computer game, etc.).

Limitations

The studies in this review are varied and thus it is difficult to draw firm conclusions. Many of the studies used different measures to assess their outcome variables, were conducted for different lengths of time, and at different levels of intensity/participant involvement. While our database search was extensive, this manuscript may not provide an exhaustive review of all of the literature on the use of mHealth technology to reduce alcohol consumption in young people. It should be noted that literature is available on the effectiveness of mHealth interventions for other populations, and that by limiting our search to young people (16–26) without known alcohol addiction we have limited the scope of findings.

Concluding remarks and future directions

Despite the limitations, this review provides some evidence for the effectiveness of mHealth technology to reduce risky drinking amongst young people. SMS messaging had the greatest efficacy amongst the interventions reviewed in this population. Interestingly, young people did not mind being interrupted by text messages as part of an intervention. Findings suggest that young people liked personalized messaging and this in itself created an effective way to convey mHealth messaging. In summary, mHealth is seen as a portable, immediate way to tailor information for young people. In addition, a reliance on settings such as schools and universities for recruiting young people narrowed the diversity of the population and the generalizability of the results.

The results of this study did not conclude that mHealth technology can definitively influence behavior change, although there was evidence that reported alcohol consumption was reduced in nine of the 18 studies. Further research using an adequately powered sample size in varied settings, with an adequate period of intervention and follow-up, based on theoretical perspectives that underpin behavior change in young people’s use of alcohol is needed. Ensuring participation of young people in study designs and implementation may also assist in the sustainability of results and their transfer into effective public health policy and practice.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None to declare

References

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balsa AI, Gandelman N, & Lamé D (2014). Lessons from participation in a web-based substance use preventive program in Uruguay. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 23(2), 91–100. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2012.748600 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1986). Social foundations of through and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bannink R, Broeren S, Joosten-van Zwanenburg E, van As E, van de Looij-Jansen P, & Raat H (2014). Effectiveness of a web-based tailored intervention (E-health4Uth) and consultation to promote adolescents’ health: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(5). doi: 10.2196/jmir.3163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Better Value Healthcare. (2017). Critical appraisal skills programme (CASP). Retrieved from http://www.casp-uk.net/

- Carrà G, Crocamo C, Schivalocchi A, Bartoli F, Carretta D, Brambilla G, & Clerici M (2015). Risk estimation modeling and feasibility testing for a mobile ehealth intervention for binge drinking among young people: The D-ARIANNA (Digital-alcohol risk alertness notifying network for adolescents and young adults) project. Substance Abuse, 36(4), 445–452. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.959152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavello D, Df T, Ries D, Brown J, DeVellis R, & Ammerman A (2012). A social media-based physical activity intervention: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Preventitive Medicineq, 43, 527–532. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn AM, Hunter-Reel D, Hagman BT, & Mitchell J (2011). Promoting behavior change from alcohol use through mobile technology: The future of ecological momentary assessment. Alcoholism-Clinical And Experimental Research, 35(12), 2209–2215. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01571.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett B, Keleher H, Rudd A, Ruth K, Locke B, & Roussy V (2013). Using SMS as a harm reduction strategy: An evaluation of the RAGE(Register and get educated) project [online]. Youth Studies Australia, 32(3), 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries H, Mudde A, Leijs I, Charlton A, Vartiainen E, Buijs G (2003). The European smoking prevention framework approach (ESPA) an example of integral prevention. Health Education Research, 18(5), 611–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue K, Patton R, Phillips T, Deluca P, & Drummond C (2014). The effectiveness of electronic screening and brief intervention for reducing levels of alcohol consumption: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(6), e142. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M (1980) A theory of reasoned action: Some applications and implications. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, Nebraska: Vol. 27 65–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaudias V, de Chazeron I, Zerhouni O, Boudesseul J, Begue L, Bouthier R, … Brousse G (2015). Preventing alcohol abuse through social networking sites: A first assessment of a two-year ecological approach. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17 (12), e278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler LA, Holt SL, & Joshi D (2016). Mobile technology-based interventions for adult users of alcohol: A systematic review of the literature. Addictive Behaviors, 62, 25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraeyman J, Van Royen P, Vriesacker B, De Mey L, & Van Hal G (2012). How is an electronic screening and brief intervention tool on alcohol use received in a student population? A qualitative and quantitative evaluation. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(2), e56. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajecki M, Berman AH, Sinadinovic K, Rosendahl I, & Andersson C (2014). Mobile phone brief intervention applications for risky alcohol use among university students: A randomized controlled study. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 9(1), 11. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-9-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold J, Lim MS, Hocking JS, Keogh LA, Spelman T, & Hellard ME (2011). Determining the impact of text messaging for sexual health promotion to young people. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 38(4), 247–252. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f68d7b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug S, Schaub MP, Venzin V, Meyer C, John U, & Gmel G (2013). A pre-post study on the appropriateness and effectiveness of a web- and text messaging-based intervention to reduce problem drinking in emerging adults. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(9), e196. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospital MM, Wagner EF, Morris SL, Sawant M, Siqueira LM, & Soumah M (2016). Developing an SMS intervention for the prevention of underage drinking: Results from focus groups. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(2), 155–164. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1073325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine L, Falconer DW, Jones C, Ricketts IW, Williams B, & Crombie IK (2012). Can text messages reach the parts other process measures cannot reach: An evaluation of a behavior change intervention delivered by mobile phone? PloS One, 7, e52621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jander A, Crutzen R, Mercken L, Candel M, & de Vries H (2016). Effects of a web-based computer-tailored game to reduce binge drinking among dutch adolescents: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(2), e29. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, & Becker MH (1984). The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Behaviour, 11(1), 1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Huedo-Medina TB, & Carey MP (2011). Interventions to reduce sexual risk for human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents: A meta-analysis of trials, 1985–2008. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(1), 77–84. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Ferssizidis P, Collins RL, & Muraven M (2010). Emotion differentiation as resilience against excessive alcohol use: An ecological momentary assessment in underage social drinkers. Psychological Science, 21(9), 1341–1347. doi: 10.1177/0956797610379863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi DM, Borsari B, Levine MJ, Li S, Lamberson KA, & Matta LA (2017). A systematic review of the mHealth interventions to prevent alcohol and substance abuse. Journal of Health Communication, 22(5), 413–432. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2017.1303556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi DM, Cochran AR, Kelly JF, Cornelius JB, & Belk C (2014). Integrating mHealth mobile applications to reduce high risk drinking among underage students. Health Education Journal, 73(3), 262–273. doi: 10.1177/0017896912471044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kool B, Smith E, Raerino K, & Ameratunga S (2014). Perceptions of adult trauma patients on the acceptability of text messaging as an aid to reduce harmful drinking behaviours. BMC Research Notes, 7(1), 4. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luxton DD, McCann RA, Bush NE, Mishkind MC, & Reger GM (2011). mHealth for mental health: Integrating smartphone technology in behavioral healthcare. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(6), 505. doi: 10.1037/a0024485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maher C, Ryan J, Kernot J, Podsiadly J, & Kennihan S (2016). Social media and applications to health behaviour. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mason M, Benotsch EG, Way T, Kim H, & Snipes D (2014). Text messaging to increase readiness to change alcohol use in college students. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 35(1), 47–52. doi: 10.1007/s10935-013-0329-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, & West R (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6(1), 42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milward J, Khadjesari Z, Fincham-Campbell S, Deluca P, Watson R, & Drummond C (2016). User preferences for content, features, and style for an app to reduce harmful drinking in young adults: analysis of user feedback in app stores and focus group interviews. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 4(2), e47. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SC, Crompton K, van Goozen S, van Den Bree M, Bunney J, & Lydall E (2013). A feasibility study of short message service text messaging as a surveillance tool for alcohol consumption and vehicle for interventions in university students. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1011. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, & Norcross JC (1992). In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviours. American Psychology, 47(9), 1102–1114. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quanbeck A, Chih M-Y, Isham A, Johnson R, & Gustafson D (2014). Mobile delivery of treatment for alcohol use disorders: A review of the literature. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 36(1), 111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid SC, Kauer SD, Dudgeon P, Sanci LA, Shrier LA, & Patton GC (2009). A mobile phone program to track young people’s experiences of mood, stress and coping. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44(6), 501. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0455-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner KA, Natalie W, Varsha P, & Ross M (2012). Harm reduction text messages delivered during alcohol drinking: Feasibility study protocol. JMIR Research Protocols, 1(1), e4. doi: 10.2196/resprot.1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan BC, Conner TS, Flett JAM, & Scarf D (2015). A brief orientation week ecological momentary intervention to reduce university student alcohol consumption. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(4), 525–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrier LA, Rhoads AM, Fredette ME, & Burke PJ (2014). Counselor in your pocket: Youth and provider perspectives on a mobile motivational intervention for marijuana use. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(1–2), 134–144. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.824470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring B, Gotsis M, Paiva A, & Spruijt-Metz D (2013). Healthy apps: Mobile devices for continuous monitoring and intervention. IEEE Pulse, 4(6), 34–40. doi: 10.1109/MPUL.2013.2279620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohman AS, Braje SE, Alhassoon OM, Shuttleworth S, Van Slyke J, & Gandy S (2016). Randomized controlled trial of computerized alcohol intervention for college students: Role of class level. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 42(1), 15–24. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2015.1105241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suffoletto B, Callaway C, Kristan J, Kraemer K, & Clark DB (2012). Text-message-based drinking assessments and brief interventions for young adults discharged from the emergency department. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 36(3), 552–560. doi: 10.1111/acer.2012.36.issue-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suffoletto B, Callaway CW, Kristan J, Monti P, & Clark DB (2013). Mobile phone text message intervention to reduce binge drinking among young adults: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 14(1), 93. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suffoletto B, Merrill JE, Chung T, Kristan J, Vanek M, & Clark DB (2016). A text message program as a booster to in-person brief interventions for mandated college students to prevent weekend binge drinking. Journal of American College Health, 64(6), 481–489. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2016.1185107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait RJ, & Christensen H (2010). Internet-based interventions for young people with problematic substance use: A systematic review. Medical Journal of Australia, 192(11), S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogl L, Teesson M, Andrews G, Bird K, Steadman B, & Dillon P (2009). A computerized harm minimization prevention program for alcohol misuse and related harms: Randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 104(4), 564–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02510.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way T, Mason M, Benotsch E, Kim H, & Snipes D (2013). Design of an Interactive Text Messaging Platform for Problem Alcohol Use Intervention in College Students.

- Weaver ER, Horyniak DR, Jenkinson R, Dietze P, & Lim MS (2013). “Let’s get wasted!” and other apps: Characteristics, acceptability, and use of alcohol-related smartphone applications. Jmir MHealth And UHealth, 1(1), e9. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.2709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein ND (1988). The precaution adoption process. Health Psychology, 7(4), 355–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzel JA, Bernhardt JM, Usdan S, Mays D, & Glanz K (2007). Using wireless handheld computers and tailored text messaging to reduce negative consequences of drinking alcohol. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(4), 534–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A, Kavanagh D, Stallman H, Klein B, Kay-Lambkin F, Proudfoot J, … Young R (2010). Online alcohol interventions: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 5, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2014). Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2015). Media centre; alcohol fact sheet. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs349/en/

- Wright CJC, Dietze PM, Crockett B, & Lim MSC (2016). Participatory development of MIDY (Mobile Intervention for Drinking in Young people). BMC Public Health, 16(1), 184. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2876-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]