Abstract

Purpose

To demonstrate feasibility of developing a noninvasive extracellular pH (pHe) mapping method on a clinical MRI scanner for molecular imaging of liver cancer.

Methods

In vivo pHe mapping has been demonstrated on preclinical scanners (e.g., 9.4T, 11.7T) with Biosensor Imaging of Redundant Deviation in Shifts (BIRDS), where the pHe readout by 3D chemical shift imaging (CSI) depends on hyperfine shifts emanating from paramagnetic macrocyclic chelates like TmDOTP5− which upon extravasation from blood resides in the extracellular space. We implemented BIRDS-based pHe mapping on a clinical 3T Siemens scanner, where typically diamagnetic 1H signals are detected using millisecond-long radiofrequency (RF) pulses, and 1H shifts span over ±10 ppm with long transverse (T2, 102 ms) and longitudinal (T1, 103 ms) relaxation times. We modified this 3D-CSI method for ultra-fast acquisition with microsecond-long RF pulses, because even at 3T the paramagnetic 1H shifts of TmDOTP5− have millisecond-long T2 and T1 and ultra-wide chemical shifts (±200 ppm) as previously observed in ultra-high magnetic fields.

Results

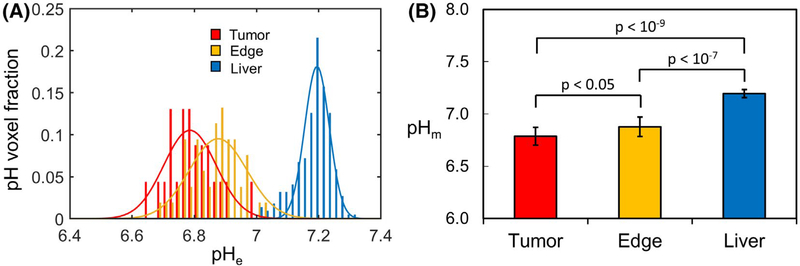

We validated BIRDS-based pH in vitro with a pH electrode. We measured pHe in a rabbit model for liver cancer using VX2 tumors, which are highly vascularized and hyperglycolytic. Compared to intratumoral pHe (6.8 ± 0.1; P < 10−9) and tumor’s edge pHe (6.9 ± 0.1; P < 10−7), liver parenchyma pHe was significantly higher (7.2 ± 0.1). Tumor localization was confirmed with histopathological markers of necrosis (hematoxylin and eosin), glucose uptake (glucose transporter 1), and tissue acidosis (lysosome-associated membrane protein 2).

Conclusion

This work demonstrates feasibility and potential clinical translatability of high-resolution pHe mapping to monitor tumor aggressiveness and therapeutic outcome, all to improve personalized cancer treatment planning.

Keywords: BIRDS, liver cancer, MRS, pH mapping, tumor microenvironment, tumors

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Rapidly growing tumor cells possess increased glucose metabolism, but reduced oxidative metabolism, even in the presence of sufficient oxygen. Because of this metabolic uncoupling, named aerobic glycolysis (“Warburg effect”), a large amount of hydrogen ions and lactate are generated, which are extruded out into the extracellular space to acidify the tumor microenvironment.1 Moreover, tumor growth and metastasis are both enhanced by acidic pHe, by activation of matrix metalloproteases and cathepsins2 while building resistance to therapy.3 While there is an imperative need for techniques that provide noninvasive pHe measurements in vivo, there is a paucity of pHe mapping methodology on clinical imaging instruments.

MRI and MR spectroscopy (MRS) are the most commonly used noninvasive techniques for in vivo pH mapping. A very popular MRI-based method is the chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST),4 where the proton exchange between the bulk water and the amide, amine, or hydroxyl groups of various molecules is pH dependent. Although pH mapping with CEST is highly attractive and has translational potential, it is not completely quantitative because of a large number of confounding factors (e.g., unknown temperature, unknown agent concentration, multiple exchangeable pools, magnetization transfer effects, inhomogeneities of magnetic [B0], and radiofrequency [RF; B1] fields, etc), although there are approaches that can account for some of these issues.5 For example, both B0 and B1 CEST corrections can be easily applied,6 whereas a ratiometric CEST approach7,8 makes the CEST contrast independent of the agent concentration. The most commonly used MRS method for pH is based on the 31P chemical shift difference between the endogenous inorganic phosphate and phosphocreatine,9 whereas other MRS methods require exogenous agents like (±)2-imidazole-1-yl-3-ethoxycarbonylpropionic acid with 1H MRS10 or 3-aminopropyl phosphonate with 31P MRS.11 However, these methods require long acquisition times because they detect diamagnetic signals that have longitudinal (T1) relaxation times of several seconds, and their linewidths are narrow because of long transverse (T2) relaxation times (hundreds of milliseconds). High-resolution pH mapping with 1H chemical shift imaging (CSI) can be achieved using Bosensor Imaging of Redundant Deviation in Shifts (BIRDS) with the macrocyclic chelate, DOTP (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetrakis[methylenephosphonate]), complexed with paramagnetic thulium (Tm3+) ion. The nonexchangeable 1H chemical shifts of TmDOTP5− are sensitive to pH and have extremely short T1 and T2 values,12,13 thus allowing pHe mapping using ultra-fast 3D CSI because of extremely short relaxation times and 1H signals that span wide chemical bandwidths. With ultra-short relaxation times, high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) 3D-CSI data from 1Hs of TmDOTP5− can be obtained with reasonable signal averaging. BIRDS has been demonstrated in brain of small and large animals, but on high-field preclinical scanners.12–21 We previously used pHe mapping with BIRDS to measure the intratumoral/peritumoral pHe gradient in 9L and RG2 gliomas in rat brain and to correlate the extensive acidic pHe in regions surrounding the tumor with tumor cell invasion.15 Rats bearing U251 gliomas treated with temozolomide (40 mg/kg) had a lower intratumoral/peritumoral pHe gradient in addition to a reduced tumor volume, reduced proliferation, and induction of apoptosis when compared to untreated rats.20 Implementation of BIRDS on a clinical scanner and in a large animal model represents the next step toward expanding its applicability to a wider variety of clinical methodologies.22

The goal of this work is to examine the efficacy of pHe mapping with BIRDS on a clinical scanner, which could allow potential clinical translatability of high-resolution pHe mapping of liver cancer. Here, we describe modifications implemented on an existing Siemens 3D-CSI pulse sequence to make it feasible for ultra-fast 3D-CSI acquisition (repetition times on the order of milliseconds), which is a requirement for pH mapping with BIRDS. We demonstrated the accuracy of pH mapping with BIRDS in vitro by comparing the average pH measured in a glass bottle with that measured using a pH electrode. We also established a relationship between SNR and the precision of pH measurements with BIRDS. To demonstrate feasibility of BIRDS in vivo on a clinical scanner, we used a rabbit model for liver cancer, where we measured the intratumoral/peritumoral pHe differences in livers implanted with highly vascularized and hyperglycolytic VX2 tumors.23–27 This tumor model has been previously used for translational studies involving intra-arterial therapies for liver cancer treatment.23,28 Histopathological markers indicative of glucose uptake (glucose transporter 1; GLUT-1) and chronic acidosis (lysosome-associated membrane protein 2; LAMP-2) were found to be upregulated in the VX2 tumors.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Animal preparation

Experiments were conducted in accord with institutional guidelines under approved Animal Care and Use Committee protocols. Animals were maintained in laminar flow rooms at constant temperature and humidity, with food and water given ad libitum. Nine male New Zealand White rabbits (2.5–4.0 kg; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) underwent implantation of VX2 tumors in the left lobe of the liver as explained earlier.25,29,30 VX2 tumors (CRL-6503) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). All experiments were performed with mycoplasma-free cells. Briefly, VX2 tumor chunks were injected into the hind leg of a donor rabbit and tumors were allowed to grow for up to 21 days. Tumor chunks were harvested from the donor animal, and ~0.4 mL were injected by a laparotomy into the left lobe of liver in the recipient rabbits using an 18G coaxial catheter system. Abdominal fascia and skin were closed in 2 layers using absorbable suture materials (chromic gut 3.0; vicryl 4.0). Tumors were allowed to grow for 14 days until a solitary tumor (1–2 cm in diameter) became visible on contrast computed tomography imaging.31,32

Animals were sedated with inhaled isoflurane (3%) along with intramuscular acepromazine (0.25–1.00 mg/kg) and ketamine hydrochloride (30–45 mg/kg). Supplemental heat support was provided and physiological monitoring (oxygen saturation, heart rate, and body temperature) was performed during the experiment. Analgesic meloxicam (0.3 mg/kg) and buprenorphine (0.02–0.05 mg/kg) were administered subcutaneously before and after surgical interventions. Surgery and MR data acquisition were performed under general anesthesia using isoflurane 1% to 3% in oxygen.

2.2 |. MRI and CSI data acquisition

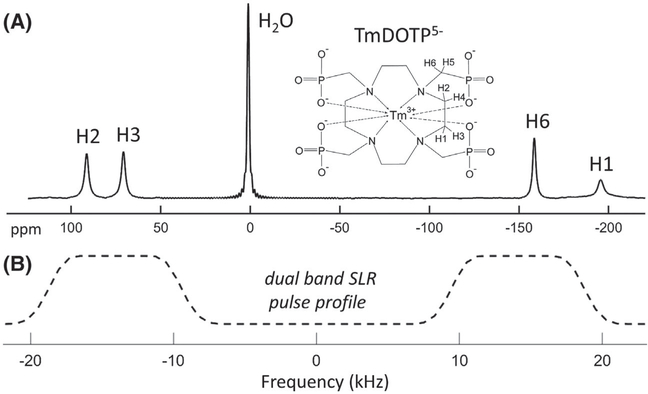

MRI and CSI data were obtained on a 3T Prisma scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using a 15-channel RF knee coil. For the in vitro experiments, a 100-mL glass bottle containing 10 mM of TmDOTP5− (Macrocyclics, Inc., Plano, TX) was used. For the rabbit experiments, 15 mL of TmDOTP5− was infused at a constant rate of 0.5 mL/min for 30 minutes for a total dose of 0.5 mmol/kg, and it was not balanced by the excretion rate. The concentration of the TmDOTP5− stock solution was calculated each time based on the weight of the animal, to yield a total volume of 15 mL. Probenecid, a drug used previously with BIRDS to increase agent perfusion by temporarily blocking kidney function,18 was not necessary in these experiments given that the contrast agent was easily able to perfuse the liver without its use. The T1 volumetric interpolated brain examination (VIBE) images were obtained for localization purposes using a field of view (FOV) of 20 × 20 cm2, 384 × 384 matrix, 60 slices of 2.5-mm thickness, recycle time = 5.2 ms, and TE = 2.5 ms. Because paramagnetic probes like TmDOTP5− possess extremely short T1 and T2 values (0.1–10.0 ms; Table 1) and 1H signals that span wide bandwidths (±200 ppm; Figure 1A), a regular 3D-CSI sequence was modified to minimize TE and recycle time, thus reducing the signal loss during preparation and acquisition. Selective excitation of H2, H3, and H6 protons of TmDOTP5− (Figure 1A) was achieved using a dual-band 640-μs Shinnar-Le Roux (SLR) RF pulse with 10.4-kHz bandwidth and 18.9-kHz separation (Figure 1B). The SLR pulse, generated in Matlab (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA) using MATPULSE v2.4,33 produces a minimal excitation of the water signal (<0.1% rejection band ripples; Figure 1B), thus bypassing the need for water suppression. Because the H2, H3, and H6 chemical shifts are not positioned symmetrically relative to the water signal, the frequency of the SLR pulse was offset by −4930 Hz relative to the water frequency to ensure the full excitation of TmDOTP5− protons on both sides of the water resonance (Figure 1B). In addition, to further reduce the signal loss attributable to transverse T2 relaxation, an excitation-only RF pulse sequence was used instead of a spin-echo sequence. A 3D-CSI sequence was preferred to a more commonly used 2D-CSI sequence, because of the large chemical shift spread of more than 200 ppm for the TmDOTP5− protons, which would result in a significant spatial displacement of CSI signals during the 2D slice selection gradient. A recycle time of 8 ms was used to ensure that the specific absorption rate does not exceed the limits allowed on a clinical scanner. Other parameters used for the 3D-CSI acquisition were: a FOV of 20 × 20 × 25 cm3, 20 averages, 13 × 13 × 13 rectangular encoding steps, and 6 minutes total acquisition time. The CSI data set was reconstructed to 25 × 25 × 25 resolution, with a voxel size of 8 × 8 × 10 mm3.

TABLE 1.

Longitudinal T1 and transverse T2 and relaxation times for the H2, H3, and H6 protons of TmDOTP5− at 3T and room temperature

| Relaxation times | H2 | H3 | H6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (ms) | 1.81 ± 0.03 | 1.82 ± 0.04 | 3.25 ± 0.06 |

| T2 (ms) | 1.84 ± 0.04 | 1.90 ± 0.05 | 2.89 ± 0.07 |

| T2* (ms) | 1.80 ± 0.02 | 1.89 ± 0.02 | 2.80 ± 0.07 |

Notes: The T1 and T2 values were calculated using inversion recovery and spin-echo experiments, respectively. The values were calculated from the line widths of the H2, H3, and H6 resonances according to Equation 4.

FIGURE 1.

Chemical structure and 1H spectrum of TmDOTP5− at 3T. The MRS signals for the H1, H2, H3, and H6 TmDOTP5− protons are indicated together with the water signal (A). The frequency profile of the dual SLR pulse used for excitation is also shown below the 1H NMR spectrum (B) to demonstrate how the MRS signals of H2, H3, and H6 protons were selectively excited, at the same time providing minimum water excitation (<0.1% rejection band ripples). Because the H2, H3, and H6 chemical shifts are not positioned symmetrically relative to the water signal, the frequency of the SLR pulse was offset by −4930 Hz relative to the water frequency to ensure the full excitation of TmDOTP5− protons on both sides of the water resonance

2.3 |. MRI and CSI data processing

The global signal Sk for TmDOTP5− proton number k, where k is 2, 3, and 6 in our experiments, was calculated in each voxel from the weighted contribution of the signal from each channel (Equation 1):

| (1) |

where NC = 15 was the number of channels, Sk,n was the signal for proton k and channel n, and wk,n was its corresponding signal intensity (height). This reconstruction approach maximizes the contribution of channels with high signal intensity and was applied separately to each TmDOTP5− resonance.

The pH was calculated in each CSI voxel from the chemical shifts δ2, δ3, and δ6 of H2, H3, and H6 TmDOTP5− protons, respectively, as described in our previous work.12,13 Briefly, a multiparametric second-order polynomial equation was used to describe the pH dependence on the TmDOTP5− chemical shifts (Equation 2):

| (2) |

where the parameters a0, , and (k = 2, 3, 6; j = 2, 3, 6) were obtained as previously described from the nonlinear least-squares fit of pH as a function of H2, H3, and H6 chemical shifts.13

2.4 |. pH error versus SNR

The goal of pHe mapping with BIRDS is to obtain precise pH measurements at high spatiotemporal resolution. With increasing resolution, the peaks will have lower SNR. Therefore, we studied how SNR affected the precision of pH determination. We calculated the SNR as the ratio between the height of a resonance and the noise in the spectrum. The noise was calculated as 3 standard deviations (SDs) measured in a spectral region devoid of any resonances. We chose to use 3 SDs for the noise estimation because 87% of the data in a normal distribution are within ±1.5 SDs of the mean, whereas only 68% of the data are within ±1 SD of the mean. However, the choice of how we defined the noise will not change the estimation of pH accuracy as long as the noise is calculated similarly for all in vitro and in vivo situations. We used an in vitro TmDOTP5− spectrum from a CSI voxel with high SNR (>100) to which we added uniformly distributed random noise with 200 different amplitudes. This procedure generated SNR values for the TmDOTP5− protons between 1 and 100. For each noise amplitude, we repeated the same procedure 1000 times, each time adding different random noise of the same amplitude, followed by fitting the H2, H3, and H6 signals with a Lorentzian function, measuring their chemical shifts (from the Lorentzian fit) and their SNR, and then calculating the pH according to Equation 2. Because the 3 TmDOTP5− protons have similar SNR values, with H6 having only slightly higher SNR than H2 and H3 protons (Figure 1A), we used the average SNR for these 3 protons for our calculations. Finally, at each noise amplitude, an average SNR and the corresponding SD in pH, σpH, were calculated from the individual values obtained for each of the 1000 simulations.

To obtain a more detailed picture of the pHe distribution inside the tumor and at tumor edge and compare it to normal tissue, a pHe voxel fraction N was calculated as the number of voxels with pHe values within every 0.02 interval between 6 and 8, divided by the total number of voxels, in all VX2 tumor and liver voxels from all the animals investigated. A voxel was considered “inside” the tumor if its “inside” partial volume, measured using the T1 VIBE image, was larger than 50%. The voxel fraction was then fitted to a Gaussian distribution (Equation 3):

| (3) |

which provided pHm (or the mean of the pHe distribution), the SD B of the distribution and the voxel fraction N0 at pHe = pHm. Note that the SD B of the Gaussian distribution of pHe values is different than the SD in pH, σpH, used for estimation of the error in pH determination.

2.5 |. Relaxation measurements

T1 was measured using inversion recovery, where each TmDOTP5− resonance was selectively inverted using a 180° Gaussian pulse, and each intensity was measured at various inversion times. T2 was measured using spin echo, where each TmDOTP5− resonance was selectively excited and refocused with Gaussian 90° and 180° pulses, and each intensity was measured at various echo times. T1 and T2 were calculated from the nonlinear least-squares fit of intensities as function of inversion time or echo time, respectively, to a single exponential. The values were calculated from the line widths of the TmDOTP5− protons, Δv1/2, measured in Hz, according to Equation 4:

| (4) |

2.6 |. Histopathological and immunochemistry staining

Upon completion of scanning, the animals were sacrificed by intravenous injection of euthasol (0.5 mL/kg). Tumor and surrounding tissues as well as contralateral liver were immediately harvested, sectioned in slices of 3 to 5 mm, fixed with 10% buffered formalin overnight, and embedded with paraffin for radiological histopathological correlation. The tissue was sliced in 2-μm sections, deparaffinized using xylene, and rehydrated with a descending ethanol dilution series. After the samples were washed with deionized water, they were permeabilized in boiling retrieval solution for 40 minutes at 95°C. Hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) staining was used according to standard protocols for general histopathology and quantification of tumor viability and necrosis of all tumors. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed also on selected tumor samples. Tumor sections were evaluated for GLUT-1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# PA1–46152, RRID:AB_2302087; 1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and LAMP-2 (Abcam Cat# ab13524, RRID:AB_2134736; 1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) targets. The specimens were incubated with ~100 μL of peroxidase quenching solution for 5 minutes and with blocking solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 20 minutes. The incubation with primary antibodies was done in hydration chambers at room temperature for 50 minutes. Subsequent incubation with biotinylated secondary antibody, streptavidin-peroxidase, and 3,3-diaminobenzidine chromogen were performed as previously described.34 Hematoxylin was used as a counterstain. The histology samples were digitalized and visualized at various magnification levels using Aperio and ImageScope software (v12.3; Leica Biosystems Imaging, Inc., Vista, CA).

2.7 |. Statistical analysis

All results are expressed in terms of mean ± SD, and all comparisons were assessed by Student’s t test with 2 tails, where P values < .05 were considered to be significant.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. In vitro pH mapping

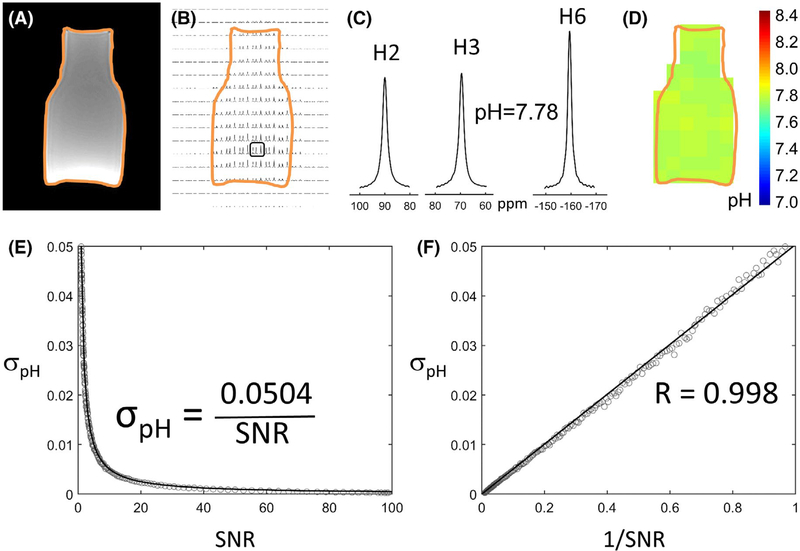

A 100-mL glass bottle containing 10 mM of TmDOTP5− (Figure 2A) was used to show an example of pH mapping with BIRDS in a CSI slice, where the H2, H3, and H6 signals of TmDOTP5− were visible in the voxels located inside the bottle (Figure 2B). A T1 VIBE image (Figure 2A) was used to draw the outline of the glass bottle (shown with the orange contour in Figure 2). Examples of H2, H3, and H6 signals are shown in Figure 2C, from the voxel indicated by a black rectangle in Figure 2B. For this voxel, the pH calculated from the chemical shifts of H2, H3, and H6 protons (Equation 2) was 7.78. A pH value of 7.75 was measured in the bottle before the acquisition with a Mettler-Toledo S220 pH meter (Mettler-Toledo International Inc, Columbus, OH), confirming the accuracy of the pH measured by BIRDS. For CSI voxels positioned at the edge of the bottle, a voxel was considered “inside” the bottle if its “inside” partial volume, measured using the intensity from the T1 VIBE image, was greater than 50%. Using this approach, a pH map of the bottle was constructed (Figure 2D). The average pH value measured using the voxels positioned inside the bottle in this CSI slice was 7.77 ± 0.01, which was consistent with the pH value of 7.75 measured using the pH electrode.

FIGURE 2.

In vitro pH mapping with BIRDS at 3T in a glass bottle containing 10 mM of TmDOTP5− and accuracy of pH determination as a function of SNR of TmDOTP5− protons. A T1 VIBE MR image (A) was used to draw the outline of the glass bottle (orange). The CSI signals of H2, H3, and H6 protons of TmDOTP5− are visible in each voxel inside the orange contour (B). Examples of 1H resonances of the H2, H3, and H6 signals from TmDOTP5− in the voxel indicated by a black rectangle in (B) are shown in (C). In this voxel, the pH measured by BIRDS was 7.78. The pH map (D) of the CSI slice shown in (B) indicates an average pH value of 7.77 ± 0.01, which is consistent with the pH value of 7.75 measured using a pH electrode. All pH values measured by BIRDS were calculated using Equation 2. To quantify how accurately we can measure the pH, we used the TmDOTP5− spectrum shown in (C), and we added random noise of various amplitudes to obtain spectra with variable SNR (see Materials and Methods). A plot of the SD σpH versus SNR (E) indicates an inverse relationship; low SNR corresponds to a significant increase in σpH. Interestingly, a strong linear relationship (R = 0.998) was observed between σpH and 1/SNR (F), with a slope of 0.0504 calculated from the linear least-squares fit of σpH versus 1/SNR, according to Equation 5. The solid line in (E) represents Equation 5 with C = 0.0504, obtained from the linear fit shown in (F)

3.2 |. Accuracy of pH measurement

The accuracy of pH determination depends on how precisely the H2, H3, and H6 chemical shifts are measured. A low SNR for these resonances would decrease the accuracy of chemical shift determination, and which in turn would result in greater error in pH measurement. Repeated measurements of the same variable (pH) under the same conditions (added random noise of the same amplitude) can provide an estimation of the measurement accuracy (see Materials and Methods). A plot of SD in pH (σpH) versus average SNR indicates that σpH increases significantly as the SNR of the TmDOTP5− protons decreases (Figure 2E), suggesting a linear relationship between σpH and 1/SNR (Equation 5):

| (5) |

Indeed, a plot of σpH versus 1/SNR (Figure 2F) demonstrates a strong linear relationship (R = 0.998), with a slope C = 0.0504 calculated from the linear least-squares fit according to Equation 5. This relationship is very useful for pH mapping with BIRDS, providing a way to estimate the error in pH measurement at various SNR values. For example, for SNR > 5, the error in pH determination is σpH < 0.01 (Figure 2E,F).

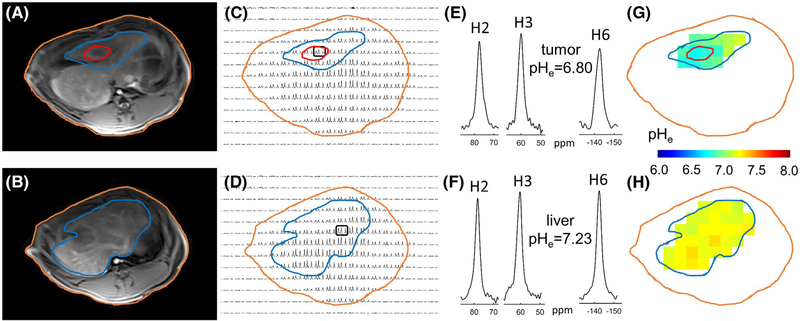

3.3 |. In vivo pH mapping in a rabbit liver tumor model

Tumor growth was demonstrated to be reproducible in all animals (n = 9). Examples of pHe mapping using BIRDS with TmDOTP5− in a rabbit liver with a VX2 tumor are shown in Figure 3. The VX2 tumor was localized by its hypointensity in the T1-weighted VIBE images (Figure 3A) and is shown using a red contour. The whole liver was also localized using the T1-weighted VIBE images (blue contour in Figure 3). For referencing/localization purposes, the profile of the rabbit body is also shown (orange contour in Figure 3). The 2 corresponding CSI slices (Figure 3C,D) are shown adjacent to the T1-weighted images. High SNR signals were visible for the H2, H3, and H6 TmDOTP5− protons inside the VX2 tumors, but also in the neighboring liver regions and in other regions of the body (e.g., blood vessels, muscles) where TmDOTP5− diffused and/or accumulated during infusion. Examples of H2, H3, and H6 signals from 2 voxels, 1 localized inside the VX2 tumor and the other in the normal liver are shown in Figure 3E,F, respectively. The pHe in these voxels, calculated according to Equation 2, were 6.80 and 7.23, respectively. For the 2 CSI slices shown in Figure 3C,D, the corresponding pHe maps were also generated (Figure 3G,H). For this rabbit, the average pHe is lower inside the VX2 tumor (6.77 ± 0.03), but also in the tumor’s adjacent regions (6.89 ± 0.09), compared to that measured in the normal liver (7.22 ± 0.04).

FIGURE 3.

In vivo pHe mapping using BIRDS with TmDOTP5− in a rabbit liver at 3T. T1 VIBE MR images (A,B) were used to localize the VX2 tumor (red contour) within the liver (blue contour), while the profile of the rabbit body is shown with an orange contour. Two different CSI slices from the same animal were used to show the H2, H3, and H6 MR signals of TmDOTP5− in each voxel, in a part of the liver containing the VX2 tumor (C) and in a part of the liver devoid of any tumor (D). 1H spectra containing the H2, H3, and H6 resonances from tumor (E) and normal liver (F) indicate a high SNR in these voxels (>10), allowing accurate pHe determination (6.80 for the tumor and 7.23 for the normal liver). The pHe maps corresponding to the 2 CSI slices shown in (C) for the liver region with a VX2 tumor and in (D) for a normal liver region are shown in (G) and (H), respectively. The measurements indicate lower average pHe values inside the tumor (6.77 ± 0.03) and in the immediate vicinity of the tumor (6.89 ± 0.09), compared to those for the normal liver (7.22 ± 0.04). All pHe values measured by MR were calculated using Equation 2

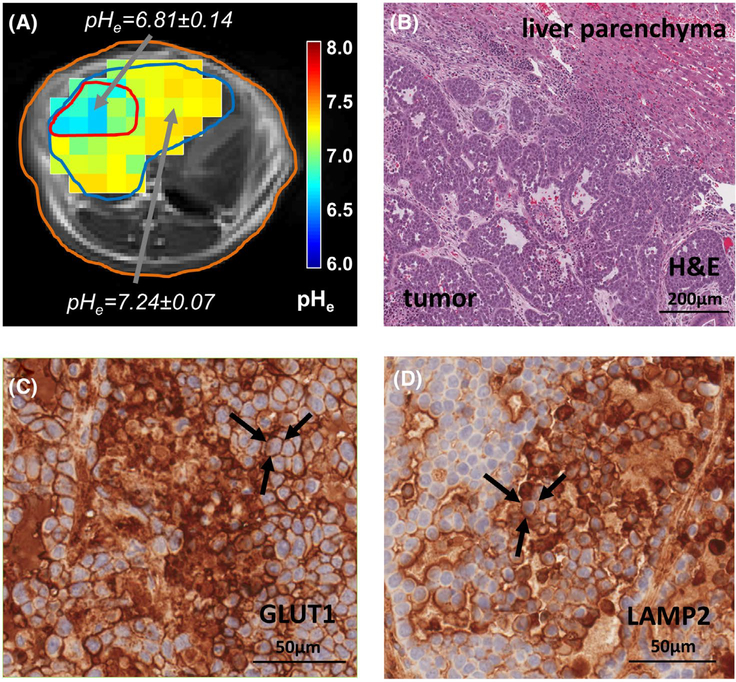

The presence of VX2 tumor cells localized in the liver was recognized by their hypointensity in the T1-weighted VIBE images, and their lower pHe (Figure 4A) was confirmed with histopathology and immunochemical staining. H&E staining of VX2 tumors revealed in the majority of tumors a necrotic tumor core and a viable tumor rim with densely packed tumor cells (Figure 4B). IHC staining confirms overexpression of GLUT-1 in cancer cells (Figure 4C), consistent with their hyperglycolytic phenotype. IHC staining for LAMP-2 indicated surface staining of cancer cells (Figure 4D), revealing exposure to chronic acidosis.

FIGURE 4.

Confirmation of tumor pHe with histology. (A) pHe maps overlaid on T1 VIBE images show regions of lower pHe inside the VX2 tumor (red contour) and higher pHe outside the tumor in the rest of the liver (blue contour) surrounded by the rabbit’s abdomen (orange contour). (B) H&E staining shows the VX2 tumor in the lower left and normal liver parenchyma in the upper right corner. (C) IHC staining confirms overexpression of GLUT-1 in cancer cells indicative of their hyperglycolytic phenotype. (D) IHC staining for LAMP-2 demonstrates positive surface staining of cancer cells indicative of exposure to chronic acidosis. The black arrows in (C) and (D) indicate examples of positively stained tumor cells

In all rabbits, an intratumoral/peritumoral pHe gradient was observed, with the lowest pHe measured inside the VX2 tumors, a slightly higher pHe in the regions adjacent to the tumors, and the highest pHe in the liver regions further removed from the tumor (Figure 5). To better understand and compare the pHe distributions in these 3 liver regions, a pH voxel fraction was calculated for each of these regions by counting the number of voxels with pHe values within every 0.02 pH interval from 6 to 8, relative to the total number of voxels (Figure 5A). A fit of the pHe voxel fraction to a Gaussian distribution (Figure 5A) provided pHm, which represents the mean of the pHe distribution, and the SD B, according to Equation 3. Calculating the means and the SDs directly from the measured pHe values yielded almost identical values as those obtained by fitting to Gaussian distributions. Therefore, to avoid presenting redundant results, we chose to show the results in the form of Gaussian distributions and their fits. Moreover, a Gaussian distribution visually conveys more information about the heterogeneity of the region investigated than just the mean and the SD values (i.e., we can visualize how symmetric the distributions are or if the distributions show a single or multiple peaks). The pHm values inside the tumor, at tumor edge, and in normal liver were 6.79 ± 0.08, 6.88 ± 0.09, and 7.19 ± 0.04, respectively (Figure 5B). The pHm values inside the tumor and at tumor’s edge were significantly lower (P < 10−9 for tumor; P < 10−7 for tumor’s edge) than in normal liver. Moreover, the pHm value inside the tumor was also significantly lower than that at tumor’s edge, although the calculated P value of 0.045 was only moderately significant.

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of pHe values in the rabbit liver with VX2 tumors. The voxel fraction with pH values within every 0.02 pH interval (A) was calculated for all voxels inside the VX2 tumors (red), at the tumor edge (orange), and for normal liver (blue). The mean pH value, pHm (B), and the corresponding SD (indicated by the error bars) were calculated from the fit of the pH voxel fraction to a Gaussian distribution (A) inside the VX2 tumors (red), at the tumor edge (orange), and in the normal liver (blue) according to Equation 3. Significantly lower pHe values were measured inside the tumor (pHm = 6.79 ± 0.08; P < 10−9) and at tumor edge (pHm = 6.88 ± 0.09; P < 10−7), compared to the pHe values measured in the normal liver (pHm = 7.19 ± 0.04). The pHe values inside the tumor are also significantly lower than those in the immediate vicinity of the tumor (P < .05)

4 |. DISCUSSION

In this work, we report pHe mapping with BIRDS in an orthotopic tumor model for liver cancer on a human-sized MRI scanner. Implementation of BIRDS on a clinical scanner (Siemens) at lower magnetic field (3T) opens up the possibility of conducting a multitude of novel MRI/MRS experiments with direct clinical translation and relevance. Several modifications of a standard Siemens CSI sequence were necessary to accommodate the ultra-short relaxation times of TmDOTP5– (Table 1). A pulse sequence with a short preparation time and fast acquisition was required. To circumvent the requirement for water suppression (which is usually several hundred milliseconds long), we used a dual-band SLR pulse, in which the resonances on both sides of the water were excited while the water signal was minimally affected (Figure 1A). The SLR pulse was a good option because of its flexibility in choosing the amplitude of pass and rejection band ripples.33,35 For this work, we chose a value of 0.1% for the rejection band ripples, which resulted in a significantly reduced water excitation (<1%). Moreover, the usage of a large acquisition bandwidth (50 kHz or 406 ppm at 3T) required by the large chemical shift spread of TmDOTP5− resonances (more than 200 ppm) was beneficial, resulting in a reduced dwell time (20 μs) and therefore allowing an increased number of data points over acquisition duration of several milliseconds. We chose to use a 3D-CSI sequence with encodings in all spatial directions because a 2D-CSI sequence with a slice selection gradient would result in a significant spatial displacement between the H2/H3 signals and H6 signal (Figure 1A) attributable to chemical shift displacement artifact. BIRDS was acquired for the first time using a multiple channel RF coil, which provided increased SNR by a signal weighted reconstruction (Equation 1).

A somewhat unexpected result was that for the H2 and H3 protons, T1 < T2 (Table 1). For the overwhelming majority of NMR signals, T1 is longer than T2, although there are some exceptions to this general trend.36 However, we believe that these small differences in T1 and T2 values are within experimental error of our relaxation measurements on the scanner, and in addition, for all 3 TmDOTP5− protons, the ratio T2/T1 was close to 1, indicating an improved SNR compared to most other diamagnetic molecules detected by MRS, for which the ratio T2/T1 is usually much smaller than 1.

The 3D-CSI in vitro data with a 10-mM TmDOTP5− glass bottle (Figure 2A–D) showed that most of the H2, H3, and H6 signals have SNR values higher than 20, allowing a very accurate pH determination, with an error of <0.003 (Figure 2E,F). Note that SD is a measure of how random errors (simulated here by random noise) affect the accuracy of pH determination. However, systematic errors in pH cannot be determined by the random noise addition approach, but it can be validated by pH measurements using alternative methods. The validity of pH measurements with BIRDS was confirmed previously in rat brain with 31P-MRS15 using inorganic phosphate and phosphocreatine resonances. Moreover, in the current work, the average pH value (7.77 ± 0.01) measured in the glass bottle with BIRDS (Figure 2) was confirmed by the pH electrode measurement (7.75).

SNR values larger than 10 were measured in most of the voxels in rabbit liver and in VX2 tumors for the H2, H3, and H6 TmDOTP5− resonances (Figure 3E,F). According to our σpH versus SNR relationship (Figure 2E,F), this corresponds to an error in pH measurement smaller than 0.005. The large SNR values measured in most of the normal liver tissue regions are a direct consequence of excellent blood perfusion in the liver, although somewhat smaller SNR (approximately 5–10) was measured in some liver regions (e.g., the liver dome in Figure 3C,D). However, despite its lower SNR, the pH accuracy in these voxels remains high, as indicated by a pH error smaller than 0.01 (Figure 3E,F). This is attributed to the fact the pH readout by BIRDS is purely based on the chemical shift of the detected peak, not its amplitude. Using the in vitro SNR of ~90 (measured in the phantom with 1 average) and the in vivo SNR of ~20 (measured in the liver with 20 averages), we estimated that the TmDOTP5− concentration in liver is ~0.5 mM. Because SNR also depends on the position of the voxel relative to the 15-channel RF coil, the conversion from in vitro to in vivo concentrations based purely on SNR and without accounting for the coil sensitivity is not quite accurate. Several experiments done in separate animals using lower doses (data not shown) indicate in vivo SNR values lower than 10 and 5, which correspond to doses of 0.25 and 0.125 mmol/kg of TmDOTP5−, respectively. Because in our experiments we targeted a pH accuracy of 0.01 or higher (SNR > 5), we determined that the lowest dose that can potentially be used without significantly decreasing the pH accuracy is 0.25 mmol/kg.

The line widths of the TmDOTP5− resonances in vivo were slightly larger (20–40%) compared to those measured in vitro, suggesting heterogeneity in the pHe distribution inside each voxel. This was also supported by the larger line widths (10–20%) measured in the tumor voxels compared to those of normal voxels, which was likely a consequence of a more heterogeneous tumor environment. CSI acquisition was achieved without respiratory gating, supporting our hypothesis that, because of its very short T2 relaxation times, BIRDS is not prone to B0 inhomogeneities produced by rhythmic breathing. However, for increased accuracy of BIRDS-based pHe mapping respiratory gating, breadth hold and motion correction can be used, especially for clinical translation, although this might decrease the temporal resolution slightly.

A limitation of this study was the relatively large voxel size (8 × 8 × 10 mm3). Thus, the CSI voxels and anatomical borders of the tumor were not perfectly “aligned,” and thus for voxels at the edge of the tumor, there was partial volume occupied by “outside the tumor” tissue, according to the T1 VIBE images used for anatomical registration. In this case, the most appropriate choice was to consider the voxel a “tumor voxel” if more than 50% of its volume was inside the tumor. Another potential limitation of the study was the heterogeneity in the size of tumors. However, the SD of average tumor pH values was very small (0.08), underscoring the reproducibility of the pHe measurements with BIRDS. Moreover, the 3D-CSI data were acquired by evenly spaced cubical encoding of k-space, requiring long acquisition times. We have previously shown that using reduced spherical encoding of k-space instead would allow a major increase in SNR.14 This k-space sampling modification of 3D-CSI data will be implemented in the future to further improve the SNR and thus reduce the aforementioned partial volume effects.

Given the ultra-short relaxation times of agents like TmDOTP5− even at 3T and which are not significantly different from their 11.7T values,13 BIRDS sensitivity is sufficiently high at clinically relevant magnetic fields. Paramagnetic agents like TmDOTP5− and similar trivalent lanthanide metal ion probes show significant clinical promise,37 but only Gd3+ agents remain US Food and Drug Administration approved. However, efforts are underway for clinical compatibility of non-Gd3+ agents with increased BIRDS sensitivity. One approach is the addition of methyl groups,12,21 as in TmDOTMA− (12 protons) versus TmDOTP5− (4 protons). Another approach is liposomal encapsulation of agents.38 Both approaches have been shown to increase BIRDS sensitivity by almost an order of magnitude, thereby reducing the agent’s dose and toxicity. Furthermore, there are several divalent transition metal ion probes with Fe2+, Ni2+, or Co2+39 that could also be promising candidates. Thus, we envision that these types of lanthanide and/or transition metal ion probes for pHe imaging with BIRDS would be clinically available in the near future.

The significantly lower pHe (P < 10−9) measured inside the VX2 tumors (pHm = 6.79 ± 0.08) compared to normal liver (pHm = 7.19 ± 0.04) was consistent with our previous pH measurements in rat brain tumors.15 This intratumoral/peritumoral pHe gradient is a consequence of the Warburg effect and is a metabolic signature of the tumor microenvironment. Moreover, significantly low pHe (pHm = 6.88 ± 0.09; P < 10−7) was also measured in adjacent regions outside of the tumor core, suggesting that the diffuse areas of low pHe could possibly indicate invading tumor cells.15 A similar result was observed in rat brains containing 9L and RG2 tumors, with the more aggressive RG2 tumors demonstrating diffuse areas of low pHe in the neighboring regions compared to the less aggressive 9L tumors.15 Given that VX2 tumors are also known to be fairly aggressive, invasive, and locally destructive,23–27 the areas of low pHe observed outside the tumor margins were consistent with the tumor’s aggressive phenotype. Furthermore, there is evidence that the immune response in the peritumoral regions is affected by acidic pH.40,41 Thus, a more thorough investigation of these regions is necessary, involving also the development of CSI methodologies that will allow pH mapping at even higher spatial resolution. As discussed above, this can be achieved by implementation of a 3D-CSI sequence with reduced spherical encoding of k-space in clinical scanners, as was previously demonstrated for preclinical scanners.14 Alternatively, a 2D-CSI sequence with separate excitation of H2 and H3 protons followed by excitation of the H6 proton can also be considered, where the 2 separate excitations would provide a way to avoid the chemical shift displacement artifact. Moreover, a 2D sequence would allow more time for signal averaging, to obtain sufficient SNR for higher resolution pH mapping.

The ability to measure the acidification of tumor microenvironment may help to better understand the underlying tumor biology, but also to monitor its metabolic activity. Increased expression levels of GLUT-142 contribute to tumor acidification measured quantitatively with BIRDS. Moreover, a newly established histological marker, LAMP-2, for which translocation and expression on cell membranes is associated with chronic acidosis of cancer cells,43 was utilized here for confirmation of in vivo pHe measurements.

5 |. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, in the current work we establish BIRDS as a noninvasive CSI method for pHe mapping on a clinical scanner, and we use it to compare pHe of VX2 tumors with normal liver pHe. The pHe measurements with BIRDS may potentially complement cancer diagnosis not only for tumor detection, but also as a functional biomarker to monitor metabolic activity of different tumor types, susceptibility to treatment, and response to therapy. While this study only investigates pHe mapping in liver with tumors, BIRDS may potentially be used as a noninvasive pHe mapping tool for other organs where TmDOTP5− can gain access (i.e., kidney, pancreas, heart, and brain), for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of pH-related diseases or conditions beyond cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the technical support of the staff within the Yale Translational Research Imaging Center for assistance with animal care. We thank Luzie Dömel, Isabel Schobert, Tabea Borde, and Lucas Adam for their support in animal handling and Maolin Qiu for technical assistance.

Funding information

NIH, Grant/Award Numbers: R01 CA206180, R01 EB-023366, P30 NS-052519, and T32 GM007205; Society of Interventional Oncology Research Grant.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr Savic reports grants from Leopoldina Postdoctoral Fellowship outside the submitted work. Dr Chapiro reports grants from the German-Israeli Foundation for Scientific Research and Development, The Rolf W. Günther Foundation for Radiological Research, Boston Scientific, Guerbet, and Philips Healthcare outside the submitted work. Dr Lin is a Visage Imaging employee.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hashim AI, Zhang X, Wojtkowiak JW, Martinez GV, Gillies RJ. Imaging pH and metastasis. NMR Biomed. 2011;24:582–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webb BA, Chimenti M, Jacobson MP, Barber DL. Dysregulated pH: a perfect storm for cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:671–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST). J Magn Reson. 2000;143:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim J, Wu Y, Guo Y, Zheng H, Sun PZ. A review of optimization and quantification techniques for chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI toward sensitive in vivo imaging. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2015;10:163–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim M, Gillen J, Landman BA, Zhou J, van Zijl PC. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:1441–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward KM, Balaban RS. Determination of pH using water protons and chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST). Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:799–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Y, Zhou IY, Igarashi T, Longo DL, Aime S, Sun PZ. A generalized ratiometric chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI approach for mapping renal pH using iopamidol. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:1553–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petroff OA, Prichard JW, Behar KL, Alger JR, Shulman RG. In vivo phosphorus nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy in status epilepticus. Ann Neurol. 1984;16:169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Martin ML, Herigault G, Remy C, et al. Mapping extracellular pH in rat brain gliomas in vivo by 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging: comparison with maps of metabolites. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6524–6531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillies RJ, Liu Z, Bhujwalla Z. 31P-MRS measurements of extracellular pH of tumors using 3-aminopropylphosphonate. Am. J. Physiology. 1994;267(1 pt 1):C195–C203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coman D, Trubel HK, Hyder F. Brain temperature by Biosensor Imaging of Redundant Deviation in Shifts (BIRDS): comparison between TmDOTP5− and TmDOTMA. NMR Biomed. 2010; 23:277–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coman D, Trubel HK, Rycyna RE, Hyder F. Brain temperature and pH measured by (1)H chemical shift imaging of a thulium agent. NMR Biomed. 2009;22:229–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coman D, de Graaf RA, Rothman DL, Hyder F. In vivo three-dimensional molecular imaging with Biosensor Imaging of Redundant Deviation in Shifts (BIRDS) at high spatiotemporal resolution. NMR Biomed. 2013;26:1589–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coman D, Huang Y, Rao JU, et al. Imaging the intratumoral-peritumoral extracellular pH gradient of gliomas. NMR Biomed. 2016;29:309–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coman D, Kiefer GE, Rothman DL, Sherry AD, Hyder F. A lanthanide complex with dual biosensing properties: CEST (chemical exchange saturation transfer) and BIRDS (biosensor imaging of redundant deviation in shifts) with europium DOTA-tetraglycinate. NMR Biomed. 2011;24:1216–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coman D, Sanganahalli BG, Jiang L, Hyder F, Behar KL. Distribution of temperature changes and neurovascular coupling in rat brain following 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) exposure. NMR Biomed. 2015;28:1257–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang Y, Coman D, Herman P, Rao JU, Maritim S, Hyder F. Towards longitudinal mapping of extracellular pH in gliomas. NMR Biomed. 2016;29:1364–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maritim S, Coman D, Huang Y, Rao JU, Walsh JJ, Hyder F. Mapping extracellular pH of gliomas in presence of superparamagnetic nanoparticles: towards imaging the distribution of drug-containing nanoparticles and their curative effect on the tumor microenvironment. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2017;2017:3849373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao JU, Coman D, Walsh JJ, Ali MM, Huang Y, Hyder F. Temozolomide arrests glioma growth and normalizes intratumoral extracellular pH. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh JJ, Huang Y, Simmons JW, et al. Dynamic thermal mapping of localized therapeutic hypothermia in the brain. J Neurotrauma. 2019. August 22 10.1089/neu.2019.6485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savic LJ, Schobert I, Peters D, et al. Molecular imaging of extracellular tumor pH to reveal effects of loco-regional therapy on liver cancer microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;clincanres-1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liapi E H Geschwind J-F, Vali M, et al. Assessment of tumoricidal efficacy and response to treatment with 18F-FDG PET/CT after intraarterial infusion with the antiglycolytic agent 3-bromopyruvate in the VX2 model of liver tumor. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:225–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vali M, Vossen JA, Buijs M, et al. Targeting of VX2 rabbit liver tumor by selective delivery of 3-bromopyruvate: a biodistribution and survival study. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;327:32–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buijs M, Vossen JA, Geschwind J-F, et al. Quantitative proton MR spectroscopy as a biomarker of tumor necrosis in the rabbit VX2 liver tumor. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:1175–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko YH, Pedersen PL, Geschwind JF. Glucose catabolism in the rabbit VX2 tumor model for liver cancer: characterization and targeting hexokinase. Cancer Lett. 2001;173:83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park HS, Chung JW, Jae HJ, et al. FDG-PET for evaluating the antitumor effect of intraarterial 3-bromopyruvate administration in a rabbit VX2 liver tumor model. Kor J Radiol. 2007;8:216–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duran R, Mirpour S, Pekurovsky V, et al. Preclinical benefit of hypoxia-activated intra-arterial therapy with evofosfamide in liver cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:536–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen JH, Lin YC, Huang YS, Chen TJ, Lin WY, Han KW. Induction of VX2 carcinoma in rabbit liver: comparison of two inoculation methods. Lab Anim. 2004;38:79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee K-H, Liapi E, Vossen JA, et al. Distribution of iron oxide-containing Embosphere particles after transcatheter arterial embolization in an animal model of liver cancer: evaluation with MR imaging and implication for therapy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:1490–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto A, Imai S, Kobatake M, Yamashita T, Tamada T, Umetani K. Evaluation of tris-acryl gelatin microsphere embolization with monochromatic X Rays: comparison with polyvinyl alcohol particles. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17(11 pt 1):1797–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong K, Kobeiter H, Georgiades CS, Torbenson MS, Geschwind JF. Effects of the type of embolization particles on carboplatin concentration in liver tumors after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in a rabbit model of liver cancer. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:1711–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matson GB. An integrated program for amplitude-modulated RF pulse generation and re-mapping with shaped gradients. Magn Reson Imaging. 1994;12:1205–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chapiro J, Sur S, Savic LJ, et al. Systemic delivery of microencapsulated 3-bromopyruvate for the therapy of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6406–6417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pauly J, Le Roux P, Nishimura D, Macovski A. Parameter relations for the Shinnar-Le Roux selective excitation pulse design algorithm [NMR imaging]. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1991;10:53–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anet FAL, O’Leary DJ, Wade CG, Johnson RD. NMR relaxation by the antisymmetric component of the shielding tensor: a longer transverse than longitudinal relaxation time. Chem Phys Lett. 1990;171:401–405. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hyder F, Rothman DL. Advances in imaging brain metabolism. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2017;19:485–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maritim S, Huang Y, Coman D, Hyder F. Characterization of a lanthanide complex encapsulated with MRI contrast agents into liposomes for biosensor imaging of redundant deviation in shifts (BIRDS). J Biol Inorg Chem. 2014;19:1385–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olatunde AO, Bond CJ, Dorazio SJ, et al. Six, seven or eight coordinate Fe(II), Co(II) or Ni(II) complexes of amide-appended tetraazamacrocycles for ParaCEST thermometry. Chemistry. 2015;21:18290–18300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buck MD, Sowell RT, Kaech SM, Pearce EL. Metabolic instruction of immunity. Cell. 2017;169:570–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goetze K, Walenta S, Ksiazkiewicz M, Kunz-Schughart LA, Mueller-Klieser W. Lactate enhances motility of tumor cells and inhibits monocyte migration and cytokine release. Int J Oncol. 2011;39:453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab. 2008;7:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Damaghi M, Tafreshi NK, Lloyd MC, et al. Chronic acidosis in the tumour microenvironment selects for overexpression of LAMP2 in the plasma membrane. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]