Description

A 17-year-old man with a several week-long history of lower left leg pain presented with lower left leg paresthesia and weakness. MRI of the spine revealed a non-enhancing extradural mass at L4 with compression of the cauda equina (figure 1). The patient underwent L4–L5 laminectomy, followed by gross total resection of the tumour, where histopathology showed a myxoid background with small cystic spaces and vacuolated physaliferous cells, consistent with a diagnosis of chordoma (figure 2). Expression of cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen, S100 and brachyury confirmed the diagnosis. Following the surgery, the patient showed resolution of left leg paresthesia, weakness and the majority of back pain. Seven years postsurgery, the patient showed no evidence of recurrent disease.

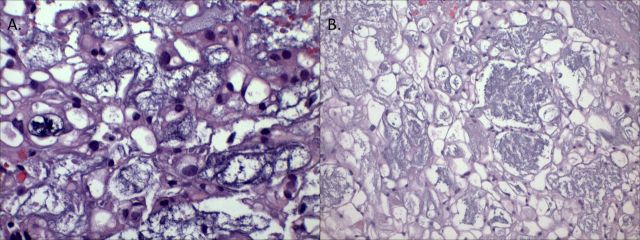

Figure 1.

MRI reveals an L4 mass with compression of the cauda (A) equina that is non-enhancing (B) and is extradural best visualised on axial T2-weighted sequences (arrowhead) (C).

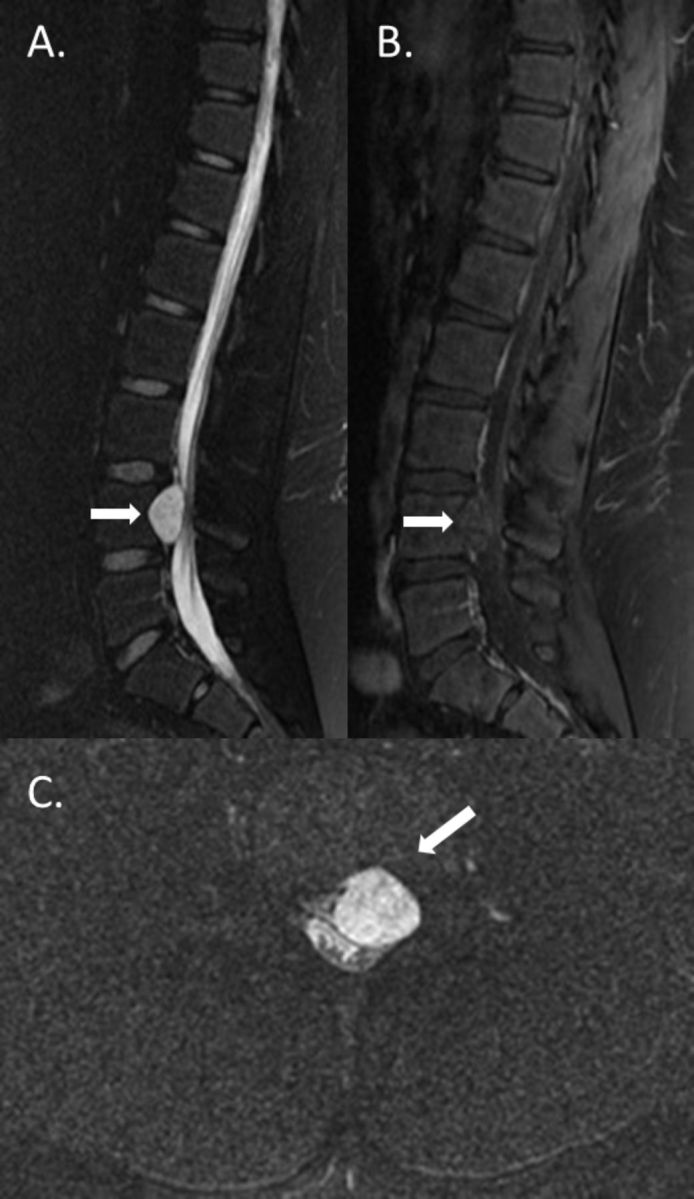

Figure 2.

Histopathology of the tumour reveals (A) myxoid background with small cystic spaces and vacuolated physaliferous cells, H&E (x200 magnification) and (B) vacuolated physaliferous cells, consistent with a diagnosis of chordoma. (x400 magnification).

Chordomas are very rare slow growing, aggressive, and locally invasive tumours derived from remnants of the notochord.1–3 They have an incidence of 0.8 per 100 000 and most frequently arise in adults between 50 and 60 years old.1–3 Paediatric cases of chordoma are rare, comprising only 6.3% of all chordoma cases.3 Chordomas typically arise in the cranium, mobile spine and sacrum.1–3 Symptoms of cranial chordoma can include cranial nerve palsies, endocrinopathy and headaches.1 3 Symptoms of spinal and sacral chordoma can include weakness, pain and paresthesia of the limbs, back pain, loss of bowel and bladder control and dysphagia.1 Because current radiotherapy and chemotherapy have been found to be ineffective in treating these tumours, treatment for chordomas involves aggressive surgery, which may be followed by high-dose radiation.1 3 In particular, complete en bloc resection without violation of the tumour capsule has been shown to be associated with reduced recurrence and prolonged survival.1 3 However, this procedure is not possible in all cases, and due to the highly invasive and recurrent nature of this disease, overall survival remains fairly low, with reports of approximately 6–13 years.1–3

Differential diagnoses for spinal chordoma include chondrosarcoma, giant-cell tumour, lymphoma, metastasis and plasmacytoma.4 However, defining histopathological features of conventional chordoma can aid in diagnosis. Conventional chordomas typically appear as grey, lobular masses composed of physaliferous cells in a myxoid matrix and are characterised by expression of cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen, S100 and brachyury.1–3 While the molecular mechanisms driving chordoma development are not well studied, epithelial–mesenchymal transition induced by downregulation of E-cadherin has been suggested to play a role.2 Deletions in chromosomes 1 and 3 have also been reported in several cases of chordoma.2 In poorly differentiated paediatric chordoma, loss of SMARCB1/INI1 expression by immunohistochemistry has been reported.5 In a small number of cases, heterozygous novel missense and nonsense mutations in SMARCB1 have been identified that may serve as a molecular driver of disease.5

This case highlights the importance of aggressive surgery in the treatment of chordomas and the need to consider chordoma as a differential diagnosis for extradural spinal tumours. Further studies are needed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms that drive chordoma formation and progression as well as identify additional effective therapies to treat these tumours, especially in cases where complete tumour resection is not possible.

Learning points.

Chordomas are rare, aggressive and locally invasive tumours derived from remnants of the notochord that can be differentiated from other lesions by their characteristic physaliferous cells and expression of cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen, S100 and brachyury.

Paediatric cases of chordoma comprise only 6.3% of all chordoma cases and a focal extramural presentation is extremely rare.

Aggressive surgery should be considered as the main treatment modality. In particular, en bloc resection has been associated with reduced recurrence and prolonged survival.

Footnotes

Contributors: LC was responsible for the design and creation of the case report and approves of its contents. DMM was responsible for the design and creation of the case report and approves of its contents. MLL was responsible for the design and creation of the case report and approves of its contents. JRC was responsible for the design and creation of the case report and approves of its contents. All authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Walcott BP, Nahed BV, Mohyeldin A, et al. Chordoma: current concepts, management, and future directions. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e69–76. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70337-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gulluoglu S, Turksoy O, Kuskucu A, et al. The molecular aspects of chordoma. Neurosurg Rev 2016;39:185–96. 10.1007/s10143-015-0663-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau CSM, Mahendraraj K, Ward A, et al. Pediatric chordomas: a population-based clinical outcome study involving 86 patients from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end result (seer) database (1973-2011). Pediatr Neurosurg 2016;51:127–36. 10.1159/000442990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatem MA. Lumbar spine chordoma. Radiol Case Rep 2014;9:940. 10.2484/rcr.v9i3.940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonelli M, Raso A, Mascelli S, et al. SMARCB1/INI1 involvement in pediatric chordoma: a mutational and immunohistochemical analysis. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41:56–61. 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]