Aqueous batteries are a reliable alternative for next-generation safe, low-cost, and scalable energy storage.

Abstract

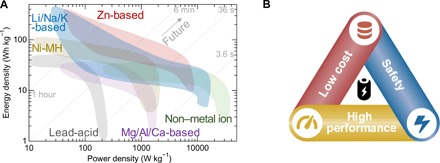

Safety concerns about organic media-based batteries are the key public arguments against their widespread usage. Aqueous batteries (ABs), based on water which is environmentally benign, provide a promising alternative for safe, cost-effective, and scalable energy storage, with high power density and tolerance against mishandling. Research interests and achievements in ABs have surged globally in the past 5 years. However, their large-scale application is plagued by the limited output voltage and inadequate energy density. We present the challenges in AB fundamental research, focusing on the design of advanced materials and practical applications of whole devices. Potential interactions of the challenges in different AB systems are established. A critical appraisal of recent advances in ABs is presented for addressing the key issues, with special emphasis on the connection between advanced materials and emerging electrochemistry. Last, we provide a roadmap starting with material design and ending with the commercialization of next-generation reliable ABs.

INTRODUCTION

Because of dwindling supplies and pollution caused by the burning of fossil fuels, the search for alternative clean energies is becoming the spotlight of worldwide research. This has led to an upswell in demand for storage of electrical energy, particularly in advanced batteries that have practical potential for grid-scale applications. Of particular research interest are the rechargeable lithium ion batteries (LIBs) (1). However, despite a high energy density, safety remains a ubiquitous issue that has impeded LIBs in security-critical applications. Incidents in recent years include Boeing 787 battery fires in 2013, Samsung Note 7 explosions in 2016, and the Tesla Model S combustions in 2019. These have caused serious threats to human health or life, which remind us continuously that safety is a prerequisite for batteries (2). In addition, the scarce abundance and increasing cost of Li (and Co) also pose challenges for large-scale applications (3, 4), while the development of resourceful sodium ion batteries (SIBs) and potassium ion batteries (PIBs) in the past decade was somewhat hindered by safety risks and environmental challenges due to the use of volatile, flammable, and toxic organic electrolytes (5, 6). The aforementioned drawbacks of the organic media-based systems have stimulated the pursuit for alternative advanced batteries with possibility for their grid-scale applications.

Aqueous batteries (ABs) are safer alternatives compared with current LIBs, SIBs, and PIBs. The use of aqueous electrolytes also offers tremendous competitiveness in terms of (i) low cost, the electrolyte and manufacturing costs are reduced by excluding oxygen-free and drying assembly lines; (ii) environmental benignity, because of the nonvolatility, nontoxicity, and nonflammability of water; (iii) capability of fast charging and high power densities due to the high ionic conductivity of aqueous media; and (iv) high tolerance against electrical and mechanical mishandling, i.e., survival after fast discharging, bending, cutting, and washing, which will not cause any disastrous consequences. Until now, various types of ABs (e.g., Ni-Fe, Ni-Cd, and Pb-acid ABs) have been successfully fabricated. Recently, because of advances in the development of materials and their better electrochemical performance, ABs as one of the ideal candidates are being revitalized especially for large-scale energy storage.

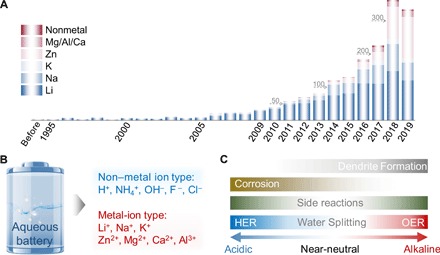

We have witnessed an astounding increase in publications regarding ABs, especially in the recent 5 years (Fig. 1, A and B). However, the grid-scale applications of ABs have been impeded by two ubiquitous issues, i.e., limited energy density and unsatisfactory life span. Fundamentally, water has inherent thermodynamic oxidation potential [oxygen evolution reaction (OER)] and reduction potential [hydrogen evolution reaction (HER)], which differ by a narrow voltage window of 1.23 V. The narrow electrochemical stability window (ESW) of water would suppress the operating voltage (Fig. 1C), leading to insufficient energy density of ABs (7). Practically, aqueous electrolytes with different pH ranges have been adopted in various ABs, which may trigger the water-based side reactions and greatly restrict the life span of ABs. Early applications of alkaline rechargeable batteries such as Ni-based Ni-Cd, Ni-Fe, and Ni–metal hydride (Ni-MH) and Zn-based Zn-Ni/Co and Zn-MnO2 batteries, undergo either low deposition/dissolution coulombic efficiency (CE) by dendrite formation, corrosion, and irreversible by-products, or volume contraction/expansion during discharge/charge cycles at the anode side. At the cathode part, the risk of OER further decreases CE, resulting in severe capacity fading of ABs (Fig. 1C). A decrease in pH of acidic electrolytes (Pb-acid, Zn-Ce, and all-V ABs) would introduce HER at the anode and induce low CE by side reactions, such as corrosion and by-product formation (Fig. 1C), leading to sustained consumption of electrolyte and capacity decay. For the near-neutral electrolytes (Li+, Na+, K+, Zn2+, Mg2+, Ca2+, and Al3+ metal-ion ABs), limitations in the capacity and redox potential at the anode side further lower the output energy density of ABs. The high capacity and low-voltage redox reactions of metals (except for Zn/Zn2+) are out of the scope of the ESW of water, which cannot be directly used as anodes in aqueous electrolytes. Moreover, the dendrite formation and decrease in CE by side reactions are inherently unavoidable even in near-neutral electrolytes (Fig. 1C), especially for achieving a long-term life span. Obviously, different AB systems may pose different challenges, while their potential interactions could be exploited, and the successful strategies established for a specific system could benchmark the success of others. To the best of our knowledge, the existing reviews of ABs either specialize in acidic Pb-acid batteries (8), alkaline batteries (9), or in neutral monovalent ion (7), multivalent ion (10), and hybrid ion batteries (11). It is desirable to provide an overview with integrated strategy in the broader context of different ABs.

Fig. 1. Status and challenges of current ABs.

(A) Number of publications devoted to different ABs. Data were collected from Web of Science in October 2019. Inset numbers represent typical scale labels. (B) Classification of ABs. (C) Summary of key challenges that are limiting energy/power densities and life span of current acidic, near-neutral, and alkaline ABs.

Despite the recent research efforts in understanding the electrochemistry of novel ABs and achieving high electrochemical performance in terms of various materials design, the gaps between expectations and reality have plagued their grid-scale application. In this review, instead of compiling recent achievements, the key issues that limit electrode operation in different AB systems are critically analyzed, from the perspective of both fundamental research and their practical application. This review also draws a timely generalized understanding, with potential relationships and integrated strategies, to the rapid advances in the development of different AB systems. Furthermore, considering that large-scale application of ABs is still in the incipient stage, it is timely to present a perspective on the design principles and roadmap to the practical use of next-generation reliable ABs.

CHALLENGES OF ABs

The promising combination of safety, low cost of raw materials and manufacturing, and environmental benignity should allow ABs to become leading candidates for energy storage solutions. To date, considerable progress on ABs has been achieved. We have witnessed an explosive growth of publications regarding advanced ABs especially in the recent 5 years, but there are still some limitations that should be overcome. The design and application of electrode materials that are compatible with aqueous electrolytes are of vital importance to achieve high performance and producible energy storage systems.

Nature of different charge carriers

Depending on the nature of migration ions, ABs can be classified into two types: metal-ion ABs and non–metal-ion ABs. So far, a variety of metal-ion ABs, such as Li+, Na+, K+, Zn2+, Mg2+, Ca2+, and Al3+, have been demonstrated on the basis of metal-ion intercalation chemistry. Li+-based ABs (LiABs) are first extensively developed because of the solid research basis in conventional nonaqueous Li-ion batteries, and benefits in terms of cost, safety, power capability, etc. As sodium and potassium are more abundant than lithium, Na+-based ABs (NaABs) and K+-based ABs (KABs) are considered as more attractive power sources than LiABs for large-scale energy storage. However, the radii of Na+ (0.95 Å) and K+ (1.33 Å) are much larger than those of Li+ (0.60 Å) (Fig. 2A), so the selection criterion was specialized to only a few compounds, showing capability of Na+ or K+ deintercalation/intercalation in aqueous media. Because of the smaller hydrated radius of solvated K+ (3.31 Å), KAB-based electrolyte exhibits much higher ionic conductivity, which enables higher rate capability in K+ storage than in Li+ and Na+ (Fig. 2A) (12).

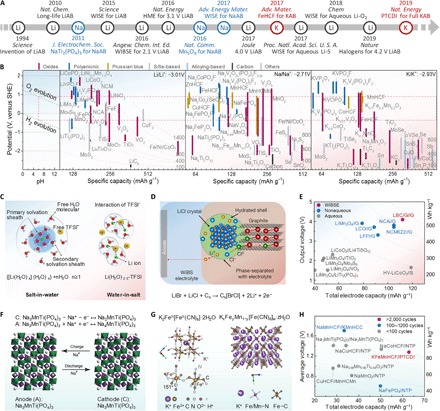

Fig. 2. Summary of electrolyte and electrode engineering strategies for the design of high-performance ABs.

(A) Comparison of ionic weight, cation radius, and hydrated radius of the typical metal-ion and non–metal ion charge carriers. (B) Summary of strategies to improve the output voltage of ABs, which can be categorized as either overpotential control or electrode design. (C) Illustration of output voltage extension from the perspective of overpotential control with water-in-salt electrolyte (WISE) or hydrate-melt electrolytes. The salt-in-water electrolyte refers to traditional aqueous electrolyte. The WISE corresponds to Mo6S8/LiMn2O4 cell in lithium bis(trifluoromethylsulphonyl)imide (LiTFSI)·H2O electrolyte (27). The hydrate-melt electrolyte is Li4Ti5O12/LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 cell in Li(TFSI)0.7(BETI)0.3·2H2O electrolyte (30). The water-in-bisalt electrolyte (WIBSE) can be C-TiO2/LiMn2O4 cell in LiTFSI + LiOTf (lithium trifluoromethane sulfolate) electrolyte (29), graphite/LiVPO4F cell in LiTFSI + LiOTf gel electrolyte (62), or graphite/lithium halide salts cell in LiTFSI + LiOTf gel electrolyte (28). (D) Illustration of output voltage extension from the perspective of electrode design with capacity balance between cathode and anode and surface electronic state control.

New opportunities are emerging in other multivalent metal-ion charge carrier–based ABs such as Zn2+, Mg2+, Ca2+, and Al3+, not only because they use earth-abundant metals but also due to their improved safety and high volumetric energy density. Nevertheless, the development of Mg, Ca, and Al-ABs has been stagnant because of even tougher criteria for hosting their large-size solvated cations (Fig. 2A) and poor reversibility in plating/stripping of Mg, Ca, and Al (13). In contrast, zinc is particularly advantageous in superior Zn/Zn2+ reversibility and its proper redox potential of −0.763 V versus standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) compared with other metals, e.g., Li, Na, K, Mg, Ca, Al, etc., in aqueous media (14). These virtues make an astounding development of Zn-based ABs in the past 5 years and provide a potential candidate for large-scale electrical energy storage.

Non–metal-ion charge carriers include anions such as hydroxyl (OH−) and halides (F− and Cl−) and cations such as proton (H+) and ammonium (NH4+) (15, 16). The attractiveness of rechargeable non–metal-ion ABs resides in the use of sustainable and unlimited charge carriers on Earth. Compared with metal-ion charge carriers (Fig. 2A), non–metal ions not only deliver lighter molar mass (only 17 g mol−1 for OH−, 18 g mol−1 for NH4+, and 19 g mol−1 for F− and H3O+) but also exhibit smaller hydrated ionic size (2.82 Å for H3O+, 3.00 Å for OH−, 3.31 Å for NH4+, 3.32 Å for Cl−, and 3.52 Å for F−), resulting in fast diffusion in aqueous electrolytes (17). Different from high corrosion damage and pollution hazards of the strong alkaline electrolytes, the halide ABs take advantage of the mild salt electrolyte such as NaCl solution (18). Compared with proton or hydronium, NH4+ is less corrosive and less prone to HER, which may deliver superior cycling performance (19).

Risk of water splitting and limited output voltage

Water splitting involves two half-reactions of the OER and HER, which require four- and two-electron transfer, respectively. The reaction pathways are sensitive to (i) the pH of electrolyte, for example, the overall reaction pathways of both OER and HER vary at different pH (OER in acidic solution is 2H2O → O2 + 4H+ + 4e−, while that in alkaline solution is 4OH− → O2 + 2H2O + 4e−; HER in acidic solution is 2H+ + 2e− → H2, while that in alkaline solution is 2H2O + 2e− → H2 + 2OH−); (ii) the structure of electrode surface, for example, the materials with different geometric structures (e.g., facets and crystallinity) and electronic structures (e.g., d-band center) exhibit different reaction mechanisms. Consequent generation of gases (H2 and O2) may destroy the structure, isolate the electrolyte, and induce large polarization, instead. The evolution of H2/O2 from aqueous electrolytes is a crucial issue that should be considered when designing materials for advanced ABs with long life span and high energy density. Moreover, HER/OER occurring on the surface of electrodes consumes a portion of electrons, which should be provided to the active materials, resulting in inferior CE, battery swelling, and continuous consumption of the electrolyte. It is important to extend the operating window and suppress the water splitting process of both cathodes and anodes in ABs.

In general, efficient ways to address this problem involve either the overpotential control or electrode design (Fig. 2B). From the perspective of overpotential control, the passivation of water electrolysis is evident. Materials with evident catalytic effect on water splitting should be avoided in ABs to maximize the voltage window. For example, Li+-intercalated vertically aligned MoS2 (20), S-vacancy and edge-activated 1T-phase MoS2 (21), and Li conversion reaction–induced ultrasmall transition metal oxides (22) are demonstrated as (bifunctional) catalysts showing high activity for water splitting. However, some philosophies for the design of catalysts could involve the passivation of catalytic processes, which, in turn, optimizes output voltage for ABs. It was found that the rate of HER is closely associated with exchange current density, overpotential, and electrolyte concentration (23, 24). Strategies to decrease the exchange current density and increase the overpotential have been developed to improve the CE and suppress self-discharge in ABs. The pH of the electrolyte, as an indicator of the acidity or alkalinity, plays a pivotal role in affecting the dynamics of redox reactions involving H+ and OH−. It is speculated that the concentrated, high-pH, O2-free electrolytes are better for low-voltage insertion electrodes (25). In general, neutral electrolytes show evident higher operating voltages than acidic or alkaline electrolytes, attributed to the larger HER and OER overpotentials (26).

Different from the decomposition of organic electrolytes in which the protective solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) on the surface of the active material is generated for the electrode stabilization after solvent decomposition, the dissociation of aqueous electrolyte cannot form traditional SEI and stabilize the electrode. Recent efforts have successfully transplanted the concept of SEI into aqueous media, leading to the notable expansion of ESW in ABs from 1.23 to beyond 4.0 V (27, 28). The tailor design of ion-conductive and electron-insulating SEI has enabled high-voltage ABs (Fig. 2C), such as Mo6S8/LiMn2O4 cell in lithium bis(trifluoromethylsulphonyl)imide (LiTFSI) “water-in-salt” electrolyte (WISE) (27) and C-TiO2/LiMn2O4, graphite/LiVPO4F, and graphite/lithium halide salt cells in LiTFSI + LiOTf (lithium trifluoromethane sulfolate) “water-in-bisalt” electrolyte (WIBSE) (29), which deliver energy densities and cycling stability approaching the state-of-the-art organic LIBs. Similarly, the thermodynamic and kinetic extension of the potential window and the upward shift of the electrode potentials can be achieved in Li4Ti5O12/LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 cell in Li(TFSI)0.7(BETI)0.3·2H2O hydrate-melt electrolyte (30), in which all water molecules are coordinated with hydrate melt of Li salts and uncoordinated water molecules are therefore eliminated.

Apart from the overpotential control strategies of pH adjustment and introduction of SEI and hydrate-melt, electrolyte additives such as cathode additive tris(trimethylsilyl) borate (TMSB) (31) and anionic surfactant sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (32), protective artificial layers of graphene on LiMn2O4 (33), polymer-coated Mg (34), AlCl3-ionic liquid–treated Al (35), hydroxylated interphase-protected Mn5O8 (36), and solid-state electrolytes (23, 37) are also effective in suppressing HER and/or OER and in further stabilizing and extending the output voltage of ABs.

From the perspective of electrode design, first of all, the capacity between cathode and anode should be well balanced to take full usage of ESW. As can be found in Fig. 2D, the untapped potential could be readily exploited by capacity balance, which has been proved the easiest way to expand the operating voltages of electronic double-layer capacitor and pseudocapacitors (26, 38). It is known that pseudocapacitive behavior has frequently been demonstrated in metal-ion intercalation of ABs to boost the high-rate and long-cycling performances (17, 39). The capacity balance strategy would be efficient in improving the voltage profiles of ABs after careful speculation of the capacity contribution (mass times specific capacity) from anode and cathode within the voltage window. Similarly, control of the equilibrium potential P0 by surface charge control method could be used to enlarge both the operating voltage and the specific capacity of the aqueous devices (40). It is concluded that the surface charge control can be achieved by charge injection (precharge), thermo-electrochemical effect (heating), and functional group introduction.

Introduction of extra redox activity that is competitive with HER or OER has been considered to be an effective approach to enhance both the capacity and output voltage of ABs. Hopefully, the selected redox couples should present redox potentials approaching the potentials of HER or OER, so that aqueous electrolyte decomposition could be suppressed and the output voltages are then boosted, attributed to the fast kinetics of the extra redox activity relative to those of HER or OER. Inspired by this, our group introduced a competitive high-voltage redox couple of Mn2+/Mn4+ in conventional Zn-ion battery (ZIB) by facile proton activity control method to significantly extend the output voltage of aqueous ZIBs (41). Other competitive redox couples have been investigated, contributing to the high voltage and energy density of ABs, like negatively charged couples of [Fe(CN)6]4−/[Fe(CN)6]3−, I3−/I−, and Br3−/Br− to suppress OER on the cathode and positively charged couples of MV2+/MV+ and HV2+/HV+ (MV and HV refer to methyl viologen and heptyl viologen, respectively) to replace the lower limit of HER (42). More trivially, the use of current collectors is important to prevent electrolysis of water and avoid corrosion. Currently, Ti, stainless steel, and bare current collectors with unreactive coating like epoxy resin are popular choices. Aqueous mixed ions or hybrid batteries are proposed to take full advantage of the cathode and anode voltage limitations with different ionic electrochemistry, such as InHCF/Na++K+/NaTi2(PO4)3 mixed-ion battery with a voltage of ~1.6 V (43) and Zn/Zn2++Li+/LiMn2O4 hybrid battery with voltage plateau ~1.8 V (44). Furthermore, other electrode design techniques have also been adopted, such as three-dimensional (3D) structure design of Zn foam (37), atomic layer deposition of amorphous TiO2 on the surface of Zn anode (45), doping Al into VO1.52(OH)0.77 (46), and introduction of cation deficiencies into ZnMn2O4 cathode (47).

Dendrite growth

Dendrite growth has shown potential hazards of piercing separators and detaching from the electrode, which would deteriorate the CE and cycling stability of ABs. Apart from Zn, most of metals cannot be directly used as anodes in aqueous media, so dendrites/protrusions are not an obvious problem in other metal-ion ABs. A uniform current and potential distribution have been believed traditionally in promoting homogeneous and compact zinc electrodeposits. The amphoteric zinc shows high solubility, electrochemical activity, and thermodynamical instability in alkaline electrolytes. As a result, the formation of zinc dendrites/protrusions is especially serious in alkaline media compared with acidic and near-neutral electrolytes (Fig. 1C), such as alkaline Zn/Ni, Zn/Mn, and Zn/air batteries, which significantly limited their life spans and commercial development prospect. The redox couple of Zn2+ ↔ Zn in mild aqueous electrolyte may reduce the Zn dendrite formation, but zinc dendrite after repeated plating/stripping is inherently unavoidable, especially for achieving long-term cycle life. According to the general principle that the deposits should have good adhesion to the substrate but be easily dissolved during stripping, the factors that affect the metal deposits mainly include (i) electrolyte composition or additives, (ii) electrode design involving 3D nanoarchitectures or surface engineering, and (iii) design of membrane separators.

Usually, zinc dendrite growth involves repeated processes of nucleation and plating/stripping. The formation of Zn with a high curvature due to the inhomogeneous nucleation should enhance local electrical fields, leading to strong adsorption of Zn2+ and further exacerbate dendrite/protrusion growth. The addition of inert components, such as Mn(CF3SO3)2 (48) and LiTFSI (49), into aqueous electrolyte has been proved to be effective in suppressing the formation and growth of detrimental dendrites. The adsorbed inert cations on the surface of dendrites/protrusions can repel extra incoming Zn2+ cations. However, the high cost of these additives blocked their practical application. Exploring more efficient and low-cost electrolyte additives like MnSO4 (50) and Na2SO4 (51) presents more tangible benefits. Other affordable attempts of using solid-state electrolytes were shown to minimize the formation of dendrites/protrusions. Our recent studies showed that the growth of Zn dendrite can be thoroughly eliminated by adopting low-cost fumed silica-based solid-state electrolyte (37), allowing the dendrite-free Zn deposition due to its excellent compatibility with Zn anode and partially wetted interface between Zn and solid-state electrolyte. Because of the sufficient surface area and active sites for Zn plating/stripping, the derived Zn electrode showed a depth of discharge (DoD) of 66%, which is much higher than those reported for Zn foil–based ZIBs. Hence, the battery can deliver impressive long-term durability up to 2000 cycles at 20°C.

Another effective strategy is to coat a protective surface layer on the Zn foil to facilitate homogeneous current distribution and Zn accommodation, such as carbonaceous materials like reduced graphene oxide and active carbon, metal oxides/hydroxides like Bi2O3, CaCO3, Ca(OH)2, and alloying with other metals, e.g., Sn, In, Bi, or Ni. In addition, the topography of the Zn anode is crucial in regulating dendrite formation. By increasing the surface area or designing 3D porous architecture, one can increase the concentration of electrochemical active sites and minimize local current or overpotential to suppress the formation of zinc dendrites/protrusions. Moreover, the void space of 3D Zn architecture would restrain the fresh Zn deposits and diminish the potential for shape change after repeated plating/stripping. To date, Zn metal anodes with various nanoarchitectures have been investigated, including fine powders, spheres, 1D wires, 2D flakes, and 3D foams (37, 52–54). Similar to restraining Li dendrite growth, the design of separators is considered effective for regulating uniform Zn deposition. It was reported by Yuan et al. (55) that the low-cost polybenzimidazole membrane could effectively prevent the zinc dendrite growth and deliver lower resistance than Nafion 115 membrane in the Zn-Fe battery. The selective ion conductive membrane with heterocyclic rings guarantees fast transportation of hydroxyl ions and mitigates ion concentration gradients, which are believed to be the primary source of dendrites/protrusions.

Corrosion, passivation, and other side reactions

The corrosion, passivation, and other side reactions during the charge/discharge process are closely related to the CE and cycling stability. Corrosion (self-discharge) is an influential side reaction in strong acidic or alkaline aqueous electrolytes, which not only decreases CE but also leads to the irreversible consumption of water and concentration change in electrolyte. The corrosion of electrodes commonly exists in ABs and usually takes place at the interface between the electrode surface and the electrolyte environment. Thus, chemistry at the electrode-electrolyte interface plays a critical role in protecting the electrode against corrosion. The interfacial chemistry and corrosion mechanisms are closely related to the composition and physicochemical properties of the electrolyte such as the pH value. Therefore, depending on these factors, different strategies have been used for certain systems, which resulted in reducing corrosion of zinc anode and improving battery performance. The mainstream strategies reported so far to reduce the corrosion rate of electrode materials include the addition of inorganic (like Zn-Bi alloy and silica coating) or organic [e.g., polyethylene glycol and polyaniline (PANI) coating] corrosion inhibitors to the electrode or electrolyte (56). On the other hand, inhibiting the corrosion of the current collectors is also a very important issue. Considering the charge effect, which can accelerate electrochemical corrosion, the stable potential of metal current collectors should also be considered on the basis of the Pourbaix (pH versus potential) diagram. For example, conventional Al and Ni cathodic current collectors are prone to the corrosion in weak acidic media at a relatively positive potential and therefore should be avoided for cathodic current collectors in Zn/Al-based ABs (AlABs).

Passivation, which is related to the formation of secondary insulating species, such as ZnO and Zn(OH)2 in alkaline Zn-based ABs, would increase internal resistance and reduce the reversibility and energy efficiency of the electrodes. Precipitation of the insulating layer on the surface of active electrodes would block the migration of charge carriers and formation of reversible products. It is important to reduce the passivation effect in Zn anodes to increase zinc utilization efficiency.

The thermodynamic stability of the host materials after charge injection is detrimental to the long-term cycling stability in ABs. The thermodynamic relationship to evaluate the stability of the electrode materials in an Li-based aqueous medium was evaluated by Dahn and co-workers (57) with the help of the following reactions

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where V (versus Li+/Li) is the delithiation potential of the electrode material, pH refers to the electrolyte, and Li(s) refers to the intercalated Li. From Eqs. 1 and 2, one electrode material is expected to be stable in the aqueous solution when its redox voltage is higher than V. For example, the lithiated Li2Mn2O4 with redox voltage of ∼2.97 V versus Li+/Li is unstable in neutral or weak acidic electrolyte, while it would be stable in an electrolyte with pH higher than 8. Unwanted side reactions of elemental dissolution may occur in LiFePO4 electrode at concentrated alkaline media (7), or Zn2+ intercalated MnO2 even at near-neutral electrolyte (41). In addition, side reactions might be worse at similar voltages in the presence of O2 as can be concluded on the basis of Eqs. 3 and 4. Hence, strategies such as elimination of residual O2 by N2 ejection or assembling batteries in inert atmosphere and fine optimization of the cutoff voltage are effective ways for stabilizing electrode in ABs. Surface coatings like carbon and introduction of electrode additives are also helpful in preventing side reactions (7).

It is worth noting that the challenges in ABs, such as water splitting, corrosion, dendrite growth, passivation, and other side reactions, are closely interconnected. As can be concluded on the basis of earlier discussion (Eqs. 2 and 3), the corrosion or other side reactions may occur concurrently with hydrogen evolution. Formation of the passivation layer should suppress the charge transport kinetics on the electrode surface, which accelerates dendrite growth with shape change. An integrated strategy should be encountered to overcome the difficulties in fabricating advanced ABs with high output voltage and long-term cyclability.

MATERIALS DESIGN AND IMPROVEMENT OF ADVANCED ABs

The search for materials that are electrochemically reversible with large ESW and chemically robust toward acidic/alkaline/near-neutral aqueous media is essential for improving the comprehensive performance ABs. On the basis of the knowledge of the aforementioned challenges and strategies in ABs, many advanced materials used in ABs have been investigated, which is summarized in the following sections.

Advances in Li/Na/K ion–based ABs

Li-based ABs

LiABs were first proposed in 1994 by Dahn and co-workers (58), using LiMn2O4 cathode and VO2 anode in 5 M LiNO3 aqueous electrolyte (see Fig. 3A). The first reported LiABs provided an average operating voltage of 1.5 V, with energy density (~55 Wh kg−1) larger than the Pb-acid batteries (~30 Wh kg−1), although the cycling was very poor. Since then, extensive efforts have been made toward developing various electrode materials for LiABs. Unlike the electrode materials used in organic systems, the redox potentials of electrode materials in aqueous systems should be within or near the electrolysis potentials of water. As shown in Fig. 3B, electrodes with redox potential out of range of red box (ESW of aqueous electrolytes at neutral pH conditions) cannot function properly since the continuous participation of water-splitting reaction. The electrode materials can be categorized into three classes based on their reaction mechanism (desertion/insertion, conversion, and alloying). Initially, all the electrode materials were based on a deinsertion/insertion mechanism (7, 59). Cathode candidates, including oxides [LiMn2O4, LiCoO2, and LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2(NCM)], polyanionic compounds [LiFePO4, FePO4, LiMnPO4, and Li(Fe,Mn)PO4], and Prussian blue analogs (PBAs; FeHCF, NiHCF, CuHCF, and MnHCF) have been developed (10, 59). Meanwhile, various anode candidates have been considered, including oxides (VO2, spinel Li2Mn2O4, layered γ-LiV3O8, H2V3O8, Na1 + xV3O8, V2O5, and TiO2), polyanionic compounds [pyrophosphate TiP2O7 and Nasicon-type LiTi2(PO4)3], and organic polymeric compounds (polypyrrole and polyimides) (10, 59).

Fig. 3. Summary of advanced materials for Li/Na/K ion–based ABs.

(A) Main progress in LiABs, NaABs, and KABs. (B) Summary of ESW of water and redox potentials of various electrode materials in organic LIBs, NIBs, and KIBs. (C) Illustration of the difference between Li+ solvation sheath in diluted and water-in-salt solutions. Reproduced with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science (27). (D) Schematic illustration of the conversion-intercalation mechanism occurring in the LBC-G composite in WIBS electrolyte. (E) Actual (red star) energy density of the LBC-G//G full cells compared with various state-of-the-art commercial and experimental Li-ion chemistries. (D) and (E) are reproduced with permission from the Nature Publishing Group (28). (F) Schematic illustration of the symmetric NaAB with the Nasicon-structured Na3MnTi(PO4)3 as the anode and the cathode. Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons (69). (G) Refined crystal structure of K2FeII[FeII(CN)6]·2H2O.(Left) Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons (71). (H) Comparison of average voltage, total electrode capacity, life span, and energy density for the KAB full battery with reported NaABs. (G) at right side and (H) are reproduced with permission from the Nature Publishing Group (12).

Although great achievements have been made in increasing discharge capacity and rate performance via materials design (e.g., surface coating, architecture, and composite) and electrolyte optimization (e.g., concentration, pH, oxygen elimination, and additives), LiABs are still limited because of their low voltage (<1.5 V), low energy density (<70 Wh kg−1), and poor cycling (59). For instance, advanced LiABs proposed by Sun et al. (60) based on LiTi2(PO4)3/C anode and LiMn2O4 cathode only presented an energy density of 68 Wh kg−1 (based on the total mass of active materials) with 90% of capacity retention after 300 cycles at 0.2°C.

WISE, first proposed in 2015 by Wang and co-workers (27), represents a revolutionary step in the development of LiABs, in which concentrated LiTFSI aqueous solution (20 mol LiTFSI in 1 kg of water) was chosen as the electrolyte. In such concentrated electrolyte, the H2O/Li+ ratio drops from 11 (5 m LiTFSI, m refers to molality) to 2.67 (molality of 21 m LiTFSI), decreasing the amount of free water molecule in the electrolyte, which contributes to restraining the electrochemical activity of water (Fig. 3C). The SEI on the anode surface, just like in the case of organic electrolyte (see Fig. 3D), can be effectively formed with the reduction in TFSI− anion before water decomposition, which further expands ESW to around 3.0 V (1.9 to 4.9 V versus Li/Li+). As a result, the assembled LiMn2O4/Mo6S8 AB shows a high average discharge voltage of 1.8 V, an impressive energy density of 100 Wh kg−1, together with high capacity retention (68% with 1000 cycles at 4.5°C). WISE provides wide opportunities for developing high-energy LiABs, not only by widening the ESW value of aqueous electrolytes but also by broadening the scope of materials selection. For instance, 21 m LiTFSI electrolyte affords LiAB coupled with TiS2 and LiMn2O4 with an energy density of 78 Wh kg−1 (61). In addition, formation of cathode electrolyte interphase (CEI) was proposed to stabilize the cathode (31). With the formed CEI through electrochemical oxidation of TMSB in 21 m LiTFSI, the capacity of LiCoO2 was extended to 170 mAh g−1; thus, a 2.0-V LiCoO2/Mo6S8 battery with 120 Wh kg−1 was achieved. Apparently, the formation of SEI highly depends on the salt concentration, that is, more concentrated electrolytes are needed to suppress water electrolysis. WIBSE containing 21 m LiTFSI and 7 m LiOTf, i.e., 28 m Li+ with H2O/Li+ ratio of 2 was also proposed to obtain a wider ESW (1.83 to 4.9 V versus Li/Li+) (29). As a result, the system allows the use of TiO2 as the anode material and endows LiMn2O4/TiO2 LiAB with a high discharge voltage of 2.1 V and an energy density of 100 Wh kg−1. In the same year, an Li(TFSI)0.7(BETI)0.3·2H2O hydrate-melt electrolyte was proposed by dissolving LiTFSI and LiN(SO2C2F5)2 (LiBETI) salts in water (30). Because of the expanded ESW (3.8 V, 1.25 to 5.05 V versus Li/Li+), various high-voltage LiABs, such as 3.1-V LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4/Li4Ti5O12 with 90.6 Wh kg−1 and 2.4-V LiCoO2/Li4Ti5O12 with 130 Wh kg−1, were obtained (30).

Although the above WISE, WIBSE, and hydrate-melt electrolytes can effectively expand ESW to around 3.0 V, its enlargement is still limited, especially for the cathodic stability (only >1.2 V versus Li/Li+). Consequently, most anode materials with low redox potential and high capacity, such as metallic Li (0 V versus Li/Li+, 3861 mAh g−1), graphite (0.1 V versus Li/Li+, 372 mAh g−1), silicon (0.30 V versus Li/Li+, 4200 mAh g−1), etc., are excluded. Simply increasing salt concentrations cannot resolve this severe “cathodic challenge.” As electrode potential polarized to 0.50 V versus Li/Li+ or below, these fluorinated salt anions experience increasing expulsion from the anode surface, and water molecules start to adsorb with hydrogen pointing toward the surface, leading to energetically favorable HER (62). Minimization of the number of water molecules at the anode surface before the SEI forms, that is, using a hydrophobic “inhomogeneous SEI additive” (LiTFSI-HFE gel) as a thin coating gel on the anode surface, is confirmed to be an effective strategy (62). Through minimizing the competing water decomposition, a conformal and dense SEI rich in inorganic LiF/organic C-F species will form upon lithiation of the anode. Combining the proposed LiTFSI-HFE gel with “solidified” WISE (gel-WISE, hydrogel of WISE using either polyvinyl alcohol or polyethylene oxide), a series of 4.0-V class LiABs were achieved, including 4.1-V LiVPO4F/Li, 4.0-V LiVPO4F/graphite, and 4.0-V LiMn2O4/Li, whose energy densities approached those of the state-of-the-art LIBs but with significantly enhanced safety (62). These works represent a fundamental breakthrough across the gap separating aqueous and non-ABs, although the cycling stability of these 4.0-V class LiABs needs to be further improved. More recently, Wang and co-workers in Nature (28) introduced a halogen conversion-intercalation mechanism in graphite to improve the cathode capacity. The cathode consisting of mixture of solid LiBr and LiCl with graphite (LBC-G) undergoes a two-stage charge and discharge process, which can be defined as a “conversion-intercalation” mechanism. During charging, bromide and chloride ions in LiBr and LiCl are consecutively “converted” into their nearly neutral atomic states, i.e., Br–0.05 and Cl–0.25, and intercalated into graphite interlayer (Fig. 3E), forming a densely packed stage I graphite intercalation compound C3.5[Br0.5Cl0.5] with a highly reversible electrochemical performance. Notably, this LBC-G cathode can deliver a high capacity of 243 mAh g−1 with an attractive potential (4.2 V versus Li/Li+), outperforming most conventional LIB cathode materials, such as LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (3.8 V, 200 mAh g−1) and LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2 (3.7 V, 200 mAh g−1). By coupling this cathode with a passivated graphite anode, a 4-V class LiAB with an energy density of 460 Wh kg−1 (total mass of cathode and anode) can be achieved.

Na-based ABs

NaABs appear to be a far more economically competitive than LiABs and have attracted intense interest for large-scale electric energy storage because of their natural abundant resources, low cost, high safety, and environmental friendliness. Unfortunately, similar to LiABs, most of the electrode materials that can serve well in organic Na-ion battery system cannot work in aqueous media, because of the narrower ESW of water. Together with more difficult desertion/insertion of larger Na+ (0.102 nm), the choice of electrode materials for NaABs is limited (see Fig. 3F). In recent years, most of the reported works in developing NaABs focused on the filter electrode materials. Up to now, several kinds of cathode materials, including Mn-based oxides (e.g., MnO2, Na0.44MnO2, Na2/3Ni1/4Mn3/4O2, Na0.44[Mn1−xTix]O2, and CoxMn3−xO4), polyanionic compounds [e.g., Na2FeP2O7, Nasicon-type Na3V2(PO4)3, NaVPO4F, Na3MnTi(PO4)3, Na3V2O2(PO4)2F, Na3V2(PO4)2F3, Na3Fe2(PO4)3, Na2FePO4F, and Na2VTi(PO4)3], and PBAs (e.g., NiHCF, CuHCF, CuNiHCF, and CoHCF) have been explored for NaABs. However, it must be pointed out that apart from the limited electrode potential, their delivery capacity (<150 mAh g−1) is far from satisfactory. More challengingly, for the NaAB anode, only a few inorganic materials {NaTi2(PO4)3, Na3Fe2(PO4)3, NaV3(PO4)3, Na3MgTi(PO4)3, NaV3O8, and KMn[Cr(CN)6], MoO3} have been developed. Recently, some work turns to the discovery organic anodes, such as polymerized pyrene-4,5,9,10-tetraone (−0.07 V versus SHE with 201 mAh g−1) (63) and 1,4,5,8-naphthalenetetracarboxylic dianhydride-derived polyimide (PNTCDA) (−0.6 V versus SCE with 140 mAh g−1) (64).

While from experience in developing LiABs, the WISE strategies are also feasible to broaden ESW in NaABs. Differently, only a lower salt concentration of 9.26 m NaCF3SO3 (NaOTF) is applicable to form an Na+-conducting SEI (65), because of the much more intense ion aggregation between Na+ and CF3SO3− than that between Li+ and TFSI−, thus making 2.5 V (1.7 to 4.2 V versus Na/Na+) of ESW for water. After that, several other types of WISE, including 35 m NaFSI with an ESW of 2.6 V (1.8 to 4.4 V versus Na/Na+) (66), 17 m NaClO4 with an ESW of 2.7 V (1.7 to 4.4 V versus Na/Na+) (67), and hybrid electrolyte of 25 m NaFSI + 10 m NaFTFSI (68), have been developed. Unfortunately, although the cycling stability of the NaABs is enhanced, their delivered voltage and energy density are still far from satisfactory due to the limited capacity and output voltage of electrode materials. Recently, another interesting work by Goodenough and co-workers (69) is attracting increasing attention in which symmetric NaABs are reported on the basis of Nasicon-type Na3MnTi(PO4)3 with redox couples of Mn2+/Mn3+ and Ti4+/Ti3+. This symmetric design not only reduces the manufacturing costs but also buffers the inner stress of battery with one electrode shrinkage accompanied by the expansion of another.

K-based ABs

KABs along with LiABs and NaABs are gaining a lot of attention. Because of the larger ionic radius of K+ (0.138 nm) than Li+ and Na+, the development of desertion/insertion-type electrode materials for KABs is impeded. Up to now, the choice of cathode materials for KABs is mainly focused on PBAs. In 2011, Cui and co-workers (19, 70) investigated the desertion/insertion behavior of K+ into CuHCF and NiHCF. Typical, nanostructured CuHCF with 59.14 mAh g−1 exhibited an impressive performance, including high redox potential (0.946 V versus SHE), high rate (67.8% at 83°C), and long cycling life (83% after 40,000 cycles at 17°C). Subsequently, on the basis of high K+ content and two one-electron redox processes, a high-capacity K2FeII[FeII(CN)6]·2H2O nanocube cathode with 120 mAh g−1 of discharge capacity and high redox potential (double platform at 0.9 and 0.3 V versus SCE) was developed (Fig. 3G) (71). For other cathode candidates, only V-based materials, including V2O5 and K0.22V1.74O4.37·0.82H2O, have been reported (72). Regrettably, sparse work has been reported as KAB anodes. Yao and co-workers (63) used an organic compound, poly(anthraquinonyl sulfide) in 10 M KOH, and reported a capacity of 200 mAh g−1 with −0.6 V versus SHE. In virtue of the wide ESW (−1.7 to 1.5 V versus Ag/AgCl) achieved by 30 m KAc WISE, the first inorganic anode KTi2(PO4)3 was reported by Leonard et al. (73), while its capacity was limited below 58 mAh g−1. In 2019, a full KAB was achieved by Jiang et al. (12), using KFeMnHCF cathode and 3,4,9,10-perylenetetracarboxylic diimide (PTCDI) anode in 22 M KCF3SO3 WISE. As shown in Fig. 3H, the KFeMnHCF-3565//PTCDI full battery features a capacity of 63 mAh g−1 with an average voltage of 1.27 V; thereby, an energy density of 80 Wh kg−1 can be achieved, which even outperforms most of the NaABs.

Advances in Zn-based ABs

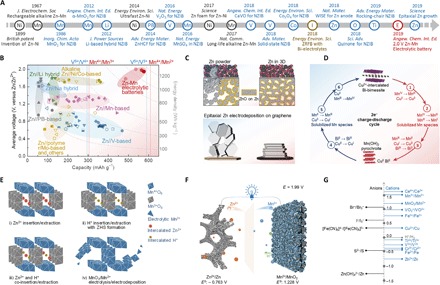

Zn-based ABs (ZnABs), the first electrochemical battery, dated back to the voltaic pile invented by A. Volta in the late 19th century. Since then, because of the very good electrochemical reversibility of zinc, dozens of Zn-based batteries were developed. Nowadays, one-third of the world battery market is composed of Zn-based batteries, which highlights its importance as a power source for a wide range of applications. On the basis of the cathode and electrolyte, ZnABs can be divided into alkaline zinc batteries (AZABs; such as Zn-Ni, alkaline Zn-MnO2, Zn-Ag, and Zn-air), near-neutral Zn-ion batteries (NZIBs; such as Zn-MnO2 and Zn-V2O5 ZIB and electrolytic Zn-Mn battery), and zinc-based redox flow batteries (such as Zn-Br, Zn-V, Zn-Ce, and Zn-I). In recent years, some breakthroughs have been achieved in aqueous Zn-based batteries (see Fig. 4A). The specific capacity versus operation voltage data for different types of batteries are displayed in Fig. 4B, based on the mass of cathode.

Fig. 4. Summary of advanced materials for Zn-based ABs.

(A) Main progress in Zn-based ABs. (B) Comparison of specific capacities and average discharge voltages of various state-of-the-art aqueous Zn-based batteries. Reproduced with permission from John Wiley and Sons (41). (C) The above is the schematic comparison of recharging Zn/Ni battery with different zinc anodes (conventional powder zinc anode versus 3D sponge zinc anode), indicating the dendrite-free feature in 3D Zn sponge anode. The below figure shows reversible epitaxial electrodeposition of Zn on graphene. Reproduced with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science (52) and (82). (D) Electrochemical reactions for the regeneration cycle of Cu2+-intercalated Bi-birnessite. Reproduced with permission from the Nature Publishing Group (74). (E) Schematic illustration of summarized reaction mechanisms for Mn-based Zn2+ ion batteries. (F) Schematic of the charge storage mechanism of Zn-Mn electrolytic battery with output voltage ~2 V. (G) Summary of standard redox potentials for various redox pairs that may be suitable for integrating new AB systems.

Alkaline Zn-based ABs

Alkaline Zn-based batteries, including Zn-Ni/Co, Zn-MnO2, Zn-Ag2O, and Zn-air batteries, which depend on the reversible redox reaction of Zn/ZnO with a redox potential of −1.35 V versus SHE, represent an old and mature battery technology, but recently, they are gaining a lot of attention. This is mainly caused by weak stability arising from the unavoidable formation of Zn dendrite, shape change, corrosion, and passivation. To solve the above issues, various strategies (23), including alloying with other metals (e.g., Bi, Sn, and In) to suppress corrosion, hybridization or surface modification with additives [such as BaO, Bi2O3, and In(OH)3 and Ca(OH)2] to suppress H2 evolution, geometry and structure design (such as Zn fibers, rods, bars, and sheets with different thickness and lengths) to mitigate shape change and zinc dendrite formation, and electrolyte additives (such as KF, K2HPO4, K2CO3, polyethylene glycol, and saturated ZnO) to reduce Zn dissolution and inhibit Zn dendrite were used. In 2017, Rolison and co-workers (52) investigated 3D Zn sponges as the anode materials at high DoD (DoDZn). As shown in Fig. 4C, thanks to the monolithic, porous, and nonperiodic architecture of Zn sponges, such 3D Zn anode achieves high utilization of 91% DoDZn and is dendrite free with repeated 50,000 cycles at <1% DoDZn. Inspired by this case, various long-life Zn anodes, based on 3D skeleton construction strategy (such as Ni nanowire, carbon cloth, Cu foam, and graphene foam) have been developed. In addition, quasi–solid-state design not only endows the batteries with high flexibility but also stabilizes the Zn anode via suppressing the corrosion and dissolution of Zn anode.

For cathode materials, MnO2 as a nontoxic, low-cost, earth-abundant, and high-capacity (617 mAh g−1) material is a promising candidate for AZABs. In alkaline Zn-Mn batteries, by-products of spinal-phase Mn3O4 (formed by Mn2+ and mother MnO2) and ZnMn2O4 [formed by MnOOH and Zn(OH)42−] accumulate after repeated cycles at deep DoD, leading to the capacity fade and eventual battery failure. In general, doping with Bi, Cu, Ni, Co, etc., elements or integrating the corresponding oxides with the cathode and using LiOH electrolyte is an effective method to enhance the capacity and rechargeability of MnO2 (23). In 2017, Banerjee and co-workers (74) realized the two-electron utilization (617 mAh g−1) of MnO2 with 6000 cycles of life span using a Cu-intercalated Bi-birnessite cathode. As shown in Fig. 4D, the key to rechargeability relies on the redox potentials of Cu to reversibly intercalate into the Bi-birnessite–layered structure during the dissolution and precipitation process for stabilizing and enhancing charge transfer characteristics. In witnessing deep utilization with high stability, such electrochemical tuning strategies unprecedentedly solved the main challenges of using MnO2 cathode in alkaline batteries.

Ni/Co-based cathode materials, because of their excellent electrochemical reversibility and acceptable theoretical capacity, have been widely used for Zn-Ni battery since the late 19th century. Among various ABs, Zn-Ni/Co batteries are particularly advantageous due to their unique merits of higher operation voltage (around 1.7 to 1.8 V; see Fig. 4B), impressive theoretical energy density (~372 Wh kg−1), high-power ability, and low cost. However, because of the poor life of zinc anode, after over 100 years, the Zn-Ni batteries were commercialized by PowerGenix (now named ZincFive Inc.) until 2003. In general, the commercial Zn-Ni battery prepared from β-phase Ni(OH)2 cathode delivers an energy density of 70 to 100 Wh kg−1, a peak power density of 2000 W kg−1, and a life span of around 500 cycles. The overall electrochemical performance is far from satisfactory for the ever-increasing demand for power storage. Aside from poor stability in zinc anode, the researchers tend to attribute such poor electrochemical performance to the reluctant specific capacity, irreversibility, and poor electroactivity in Ni/Co-based cathode. Fortunately, some achievements in designing nano-architecture Ni/Co-based cathode materials have raised hopes in recent years. In 2014, Dai and co-workers (75) inaugurated an ultrafast high-capacity Zn-Ni battery based on ultrathin NiAlCo layered double hydroxide/carbon nanotube (LDH/CNT) nanoplate cathode, in which Al and Co co-doping stabilized α-Ni(OH)2. Attributing to the high capacity (354 mAh g−1), high rate (278 mAh g−1 at 66.7 A g−1), and good stability (94% of capacity retention after 2000 cycles) of the NiAlCo LDH/CNT cathode, the assembled Zn-Ni battery delivered an energy density of 274 Wh kg−1 and a power density of 16.6 kW kg−1, together with good cycling stability (85% capacity retention after 500 cycles). Inspired by this work, so far, various Ni-based and Co-based materials, such as NiAlCo-LDH/CNT (75), Ni3S2 (76), Co3O4 (77), and NiCo2O4 (78), have been extensively explored for Zn-Ni batteries.

Besides the compositional optimization, rational nano-architecture design (e.g., nanoparticles, nanowires, nanorods, and nanosheets) can provide unique merits in mechanical and electrical properties, such as higher surface area and shorter pathways for transport of ions and electrons, and conquer the intrinsic challenges of bulk materials, such as poor electrical conductivity and large volume expansion. In addition, surface modification, such as surface coating of PANI and surface doping of phosphate ions, can further enhance the electrical conductivity of electrodes (76, 78). However, it should be noted that the developed advanced self-standing cathodes are still far from practical application, although they have achieved remarkable gravimetric capacity, high rate, and long life. Their areal capacity is generally lower than 1.0 mAh cm−2, which is much lower than the industrial-level areal capacity of ∼35 mAh cm−2 (79). Therefore, further developments of Ni-based and Co-based materials for Ni-Zn or Co-Zn batteries, which simultaneously have high gravimetric capacity, high rate capability, and long life with high mass loading, remain difficult to achieve.

Neutral ZIBs

NZIBs, which use neutral or weak acidic Zn2+-containing aqueous media as the electrolyte, are attracting increasing global attention in recent years because of their potential for large-scale electrical energy storage. As early as 1986, a rechargeable Zn-MnO2 battery using MnO2 cathode and Zn anode in 2 M ZnSO4 electrolyte was first investigated by Yamamoto et al. (80), but the reaction mechanism was unclear. Until 2012, Kang and co-workers (81) found the reversible intercalation of Zn2+ into α-MnO2 and proposed the concept of NZIBs combining with a zinc anode and a mild ZnSO4 or Zn(NO3)2 aqueous electrolyte. Intensive efforts have been devoted to NZIBs since then with the purpose of revealing the reaction mechanism and developing advanced electrode materials. Unlike AZABs, the charge storage in the anode depends on the reversible plating/stripping of Zn/Zn2+ with a redox potential of −0.763 V versus SHE. Although the severe corrosion and dissolution of Zn are eliminated, the biggest challenges are in suppressing the formation of zinc dendrite. Up to now, various efforts, including surface modification, structural optimization (37), and electrolyte optimization (47), have been explored to eliminate the formation of zinc dendrite. For instance, a high-rate flexible quasi–solid-state ZIB constructed from graphene foam supported Zn array anode, and a gel electrolyte can deliver long-term durability of 2000 cycles with 89% of the initial capacity (37). Moreover, it was recently pointed out by Archer and co-workers (82) that graphene, with a low lattice mismatch for Zn, is effective in driving the deposition of Zn with a locked crystallographic orientation, which prompts exceptional reversibility of the Zn anode.

Another issue that has hindered the application of NZIBs is the lack of robust cathode host materials for fast and reversible Zn2+ storage, due to the high charge density and high hydrated ionic radius of Zn2+. So far, although various cathode materials, such as manganese oxides, V-based, PBAs, and organic materials have been proposed (14), the development of cathode materials for ZIBs is still in its infancy stage. This is mainly ascribed to the following four aspects: (i) The reaction mechanism still remains controversial, (ii) fast capacity decay, (iii) unsatisfactory specific capacity, and (iv) poor rate performance. V-based compounds, especially vanadium oxides, are attractive host materials for Zn2+ storage. Because of their inherent features of the multiple valence states of vanadium and the large open-framework structure, V-based materials have merits of high capacity (even up to 400 mAh g−1), fast dynamics, and low cost. As for the reaction mechanism, it is generally considered as the insertion/extraction of Zn2+ in the host materials during the corresponding discharge/charge process. Recently, with the observation of zinc hydroxide sulfate [Zn4(SO4)(OH)6·nH2O, ZHS] in Zn-V systems, H+ is also regarded as the charge carrier to participate in the electrochemical reaction (83). On the basis of the simultaneous H+ and Zn2+ insertion/extraction process, the Zn/NaV3O8·1.5H2O battery proposed by Chen and co-workers (51) delivers a superior reversible capacity (380 mAh g−1) and a high durability (82% of capacity retention after 1000 cycles). Apart from the study of mechanism, more work is needed on advanced materials for improving the specific capacity, rate performance, and cycling life of V-based cathode. Up to now, some optimization strategies, including morphological and structural control (such as designing various nanoarchitectures; preinsertion of Li, Na, K, Zn, Ca, etc., metal ions; and adjustment of structural water), integrating with conductive additives, designing binder-free electrode, and optimizing electrolytes, have been attempted (83). Dozens of V-based compounds, such as V2O5·nH2O (84), Zn0.25V2O5·nH2O (85), and Zn2(OH)VO4 (37), have been developed. In general, the V-based oxides can present an ultrahigh discharge capacity of over 400 mAh g−1, while their operating voltage is relatively poorer than that of Mn-based materials (Fig. 4B). For example, the Zn/Zn0.3V2O5·1.5H2O battery fabricated by Wang et al. (86) delivers an average discharge voltage of 0.8 V, and a high specific capacity of 426 mAh g−1 at 0.2 A g−1, together with an unprecedented cycling stability (maintains 214 mAh g−1 after 20,000 cycles at 10 A g−1).

PBAs, similarly to LiAB, NaAB, and KAB systems, can also be used as cathode materials for NZIBs. In 2015, a PBA-based NZIB built on ZnHCF was first proposed by Liu and co-workers (87), with a relatively high operation voltage of ~1.7 V, a discharge capacity ~65.4 mAh g−1, and an energy density of 100 Wh kg−1. Since then, various other PBA-based NZIBs, such as CuHCF-Zn (56 mAh g−1, 1.73 V), FeHCF-Zn (120 mAh g−1, 1.1 V), NiHCF-Zn (56 mAh g−1, 1.2 V), and MnHCF-Zn (137 mAh g−1, 1.7 V), have been developed (14). However, note that because of the low capacity, the energy density of PBA-based NZIBs is still not competitive. Besides the inorganic materials mentioned above, some organic ones, such as PANI (191 mAh g−1, 1.0 V) (88) and calix[4]quinone (335 mAh g−1, 1.0 V) (89), have been developed. Up to now, the development of organic cathode materials for NZIB is still in its preliminary stage. With the abundant choices of functional group and molecular weight, there remains an immense potential to optimize the electrochemical performance of organic electrodes.

Manganese oxides, with the merits of abundant crystallographic polymorphs (α, β, γ, δ, λ, ε, and todorokite types), high theoretical capacity (308 mAh g−1), low cost, and being earth abundant, have been regarded as promising cathode candidates for NZIBs. In general, with the applicable exploration of various MnO2 polymorphs for NZIBs, there are mainly four-stream concepts as shown in Fig. 4E on the energy storage mechanism: (i) Zn2+ insertion/extraction, (ii) H+ insertion/extraction accompanied with the deposition of ZHS, (iii) coinsertion/extraction of both H+ and Zn2+ in different charge/discharge steps, and (iv) electrolysis/electrodeposition of MnO2/Mn2+, which have been systematically summarized in reports (14, 41).

Although the reaction mechanism remains under dispute, the first three mechanisms assume that the severe dissolution of Mn2+ in the discharge process is responsible for the fast capacity decay. Up to now, some effective strategies, including preaddition of Mn salt in electrolyte (50), surface coating [such as N-doped carbon (90) and PEDOT (91)], and incorporation of closely bonded ions [such as K0.8Mn8O16 (92)], have been used to suppress the dissolution of Mn2+ and enhance the cycling stability of NZIBs. Specially, the cycling stability of the Zn-MnO2 battery could be greatly enhanced by preaddition of Mn2+, achieving a 10,000-cycle life span without obvious capacity decay (93). It should be noted that such excellent cycling stability is attributed not only to the stabilized MnO2 by suppressing the dissolution of Mn2+ but also from the extra capacity provided by the redeposited MnO2 in the charge process (94). In addition, large volumetric change and structural collapse caused by repeated insertion of hydrated Zn2+ ions also result in a rapid capacity fading. Thereby, various efforts, such as morphological control of porous structure (90), coupling with graphene and CNTs (95), and structure stabilization by cationic doping and PANI intercalation (96), have been explored. For example, PANI-intercalated MnO2 nanolayer can deliver a stable discharge capacity of around 125 mAh g−1 over 5000 cycles (96).

Although great progress has been achieved as can be seen from Fig. 4A, the current Zn-based alkaline batteries and neutral or weak acidic Zn2+ batteries have shown limited output voltages (<1.8 V) and discharge capacity below 450 mAh g−1. In our latest research, we found a latent high-voltage MnO2 electrolysis process in a conventional ZIB and proposed a previously unknown electrolytic Zn-Mn system (see Fig. 4F), via enabled proton and electron dynamics (41). The four-step MnO2 electrolysis process was first analyzed by density functional theory calculations. This Zn-Mn electrolytic system presents an output voltage as high as 1.95 V, an imposing gravimetric capacity of about 570 mAh g−1, and density of ~409 Wh kg−1 based on both anode and cathode active materials. A prototype redox flow-battery stack was also built in our Zn-Mn electrolytic battery. In summary, the output voltage (~2 V), energy efficiency (88%), and cost of the electrolyte [3 to 5 US$ (kW h)−1] outperform other redox pairs integrated AB systems (Fig. 4G), such as Zn-Fe, Zn-Br2, Zn-Ce, and all vanadium flow batteries (41). It is expected that with further judicial development, such as the use of a more selective electrolyte, Zn efficiency improvement, and efficient flow-stack battery design, this Zn-Mn electrolytic flow battery design will be applicable for practical energy storage and, particularly, for large-scale grid energy storage.

Advances in Mg/Al/Ca ion–based ABs

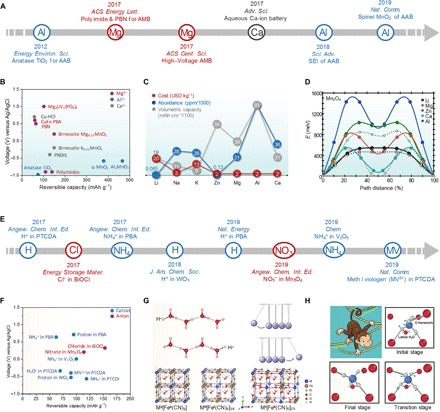

Other than the conventional aqueous Li/Na/K-ABs and ZnABs, there is another type of ABs based on relatively abundant metal elements as charge carriers, such as magnesium, aluminum, and calcium ions. Some breakthroughs and materials in Mg/Al/Ca ion–based ABs in recent years have been summarized in Fig. 5 (A and B).

Fig. 5. Summary of electrode materials for Mg/Al/Ca ion–based and non–metal ion–based ABs.

(A) Timeline of recent developments in the area of advanced aqueous Mg/Al/Ca-ion batteries. (B) Comparison of various electrode materials for aqueous Mg/Al/Ca-ion batteries. (C) Comparison of cost, abundance, and volumetric capacity of metal anodes. Data sourced from (25) and (102). (D) First-principles elastic band simulations of migration energies of metal ions in the spinel Mn2O4. Reproduced with permission from the American Chemical Society (103). (E) Timeline of recent developments in the area of advanced aqueous non–metal ion batteries. (F) Comparison of various electrode materials for non–metal ion–based ABs. (G) Scheme of the Grotthuss proton transportation. Reproduced with permission from the Nature Publishing Group (105). (H) Scheme and diffusion mechanism of NH4+ ion. Cartoon of the monkey swinging process; NH4+ breaks and reforms H─O bonds one at a time during its migration within the V2O5 bilayer. Reproduced with permission from Elsevier (17, 109).

In the study of magnesium ion ABs (MgABs), Chen et al. (97) recently proposed an aqueous magnesium ion battery, which involves a reversible Mg2+ intercalation-deintercalation in a nickel hexacyanoferrate cathode. PBA nickel hexacyanoferrate, which is shown to be capable of reversibly intercalating various cations in its open-framework structure, was also selected as the cathode in this battery. It is worth noting that the PBA cathode goes through a replacement process of extracting the Na+ ion and substituting by Mg2+ ion in the open framework without structural destruction. On the other side, an aromatic polyimide formed by condensation reaction was chosen as the anode. The polyimide family has been reported as anode host materials for both Li+ and Na+ intercalation while effectively suppressing hydrogen evolution in aqueous electrolyte. As a result, the corresponding battery can achieve a specific energy density of 33 Wh kg−1, which is close to their theoretical energy density of 48 Wh kg−1. Apart from that, Nazar and co-workers (98) also reported the insertion of Mg ion in birnessite in aqueous Mg-ion batteries, suggesting that aqueous Mg-ion batteries exhibit higher rate performance than the one in nonaqueous media due to the difference in anion desolvation energy.

To improve the energy density of aqueous magnesium ion batteries, Wang and co-authors (27, 99) applied the superconcentration strategy to expand ESW to 2.0 V, which is about three times higher than that of the conventional dilute MgSO4 electrolyte of ~0.7 V. It should be noted that the wide ESW of 2.0 V enables the use of MgxLiV2(PO4)3 (LVP), which is obtained by delithiation and subsequent magnesiation process of Li3V2(PO4)3. Similar to most of the previous MgABs, a member of the polyimide family PNTCDA is chosen as the anode. Thanks to the accelerated Mg ion diffusion within LVP and the relatively wide ESW achieved by the superconcentration strategy, MgAB exhibited an excellent rate capability of 60°C, a cycling stability within 6000 cycles, a high power density of 6.4 kW kg−1, and a high specific energy density of 68 Wh kg−1.

Overall, in the selection of electrode materials for aqueous magnesium ion batteries, two important aspects should be mentioned: (i) To enable the reversible intercalation/deintercalation of magnesium, nowadays, most of the cathode materials are achieved via prereplacement of the cations with Mg ions, while some Mg-containing oxide cathodes are also reported (97–99); (ii) as can be seen in Fig. 5B, most of the reported anodes are carbon-based polyimides and V-based oxides (100). Although diverse polyimide and PBA anodes are available, the exploration of new types of Mg-ion host electrodes with high capacity and output voltage is essential for the future development of MgABs.

Furthermore, aluminum is earth abundant, low cost, chemically inert, and has the highest volume-specific charge storage capacity (8040 mAh cm−3), as shown in Fig. 5C, which is approximately four times larger than that for lithium metal batteries (35, 101). The major issue for aluminum anode lies in the rapid and irreversible formation of a high-bandgap passivated oxide coating, Al2O3. Archer and co-workers (35) used an AlCl3–1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride–treated aluminum substrate and found that this ionic liquid–enriched film is capable of eroding the oxide film and protecting the aluminum against subsequent oxide film formation in aqueous media. After coupling with the MnO2 cathode, the AlAB achieved an energy density of up to 500 Wh kg−1. The major challenge in the cathode part lies in the high charge density of Al3+ for its reversible insertion/extraction in the host materials. To address this issue, another AlAB configuration with Al(OTF)3-H2O electrolyte and AlxMnO2·H2O cathode was reported (101). The AlAB enabled a high discharge capacity of 467 mAh g−1, resulting in a high energy density of 481 Wh kg−1. On the basis of previous studies, it can be concluded that the main issue of AlABs remains in improving the reversibility of Al3+ plating/striping at the anode and extraction/insertion at the cathode (102). Breakthroughs in novel host materials and electrolytes related to the interface engineering are desired.

In contrast to Mg and Al ions, calcium ions have a larger ion radius (0.99 Å) than that of Mg2+ (0.65 Å) and Al3+ (0.50 Å) as shown in Fig. 2A. Nevertheless, Ca2+ has a low polarization strength and charge density similar to that of Li+; therefore, the superiority of the Ca2+ chemistry could be reflected in better kinetics in electrode materials, avoiding the kinetics issues related to Mg2+ and Al3+. As a result, higher electrolyte conductivity and faster ion diffusion in the electrolyte may also be observed due to the smaller Ca2+ hydrated radius and more facile dehydration. As shown in Fig. 5D, Ca2+ is proven to have a smaller migration barrier than that of Mg2+ and Al3+ in spinel Mn2O4 (103). Despite the kinetics superiority, the development of Ca-based ABs (CaABs) is stagnated due to the limited success in Ca-ion storage materials. Recently, Gheytani et al. (104) first reported a full CaAB with organic polyimide as the anode and copper hexacyanoferrate as the cathode, showing a specific energy of 54 Wh kg−1 and outstanding stability within 1000 cycles. Identical electrodes have also been applied in an MgAB to comprehensively understand the differences of the charge carriers. The kinetics analysis showed faster kinetics in the Ca(NO3)2 electrolyte than in the Mg(NO3)2 one.

Advances in non–metal ion–based ABs

Other than the metal-ion batteries, recently there is a novel kind of aqueous “rocking-chair” battery that uses non–metal ion as the charge carrier. Some breakthroughs and materials in non–metal ion–based ABs in recent years have been summarized in Fig. 5 (E and F). Compared with the metal-ion batteries, the most significant feature of non–metal ion batteries is that the ions used in these systems are based on abundant elements; thus, the limited reserves of the elements used are no longer the bottleneck to an energy storage system.

Specifically, proton and hydronium, its simplest hydrate, have been investigated as the charge carrier in different electrodes. Ji and co-workers (105–107) have investigated the proton storage capability in hydrate oxide, highly crystalline organic electrode, and PBA. The H-based AB (HAB) is advantageous because of its excellent rate performance when hydrated oxide and PBA are used (105). It is suggested that the diffusion-free Grotthuss topochemistry is the key to this superior rate performance of proton batteries. Akin to Newton’s cradle (as shown in Fig. 5G), the transfer of protons with correlated local displacement enables their fast long-range transport. The motion process is highly varying from the conduction of metal ions where solvated metal ions diffuse at long distance individually. As a consequence, the battery based on the so-called Grotthuss proton conduction exhibited excellent rate performance of 78, 67, 56, and 49 mAh g−1 at 20°, 200°, 2000°, and 4000°C, respectively. It is noteworthy that half of its capacity at 1°C can retain even at the extremely high current density of 4000°C. The rate capability potential of HABs remains enormous due to the present limitation in the electrical resistance of the testing cells.

Ammonium is another attractive charge carrier due to its light molar mass of only 18 g mol−1 and the small hydrate ionic size, which facilitates its fast diffusion in the electrolyte. Compared with proton-based batteries, use of ammonium ions would avoid the usage of corrosive acidic electrolyte and correspondingly suppress the elemental dissolution of cathode and hydrogen evolution at the anode (108). Initially, PBA was selected as the cathode material due to its robust crystal structure and facile de/insertion of alkali metal ions (108). Similar to the cathode in MgABs, PBA used in ammonium ABs was subjected to a process of replacement of pristine alkali ions by NH4+. With the aim to improve its rate performance, authors from the same group used hydrated bi-layered V2O5 to serve as a cathode to store ammonium ions (109). In this work, the authors claimed the superior rate performance originated from a chemisorption-involved intercalation pseudocapacitance. Through comparison of different pseudocapacitive behavior of NH4+ and K+, the authors suggested a “monkey swinging” process in which the ammonium ion can twist to disconnect one of its trailing hydrogen bonds and form a new hydrogen bond with another oxygen atom during its migration in crystal structure of hydrated bi-layer V2O5 (as shown in Fig. 5H).

Apart from proton and ammonium, recently Wei et al. (110) explored the potential of using MV2+ as a dicationic charge carrier in an aromatic solid electrode material 3,4,9,10-perylenetetracarboxylic dianhydride (PTCDA). MV2+ is the largest insertion charge carrier (when nonsolvated) ever reported for batteries. The interaction between MV and PTCDA is capable of offering a decent capacity of ~100 mAh g−1 and 60% rate capability retention from 100 to 2000 mA g−1. This result shows that the large charge carrier does not compromise the specific capacity and rate capability. Exploring novel multivalent ions, especially novel organic charge carriers, might be an interesting avenue for ABs.

Except for aqueous cation batteries, there are several reports on anion non–metal ion–based ABs (18). For example, Chen et al. (18) recently reported a chloride-ion AB in an NaCl solution with BiOCl anode and silver cathode. The most extraordinary advantage of the Cl− ion is its high abundance in the natural form, for example, NaCl solution, e.g., seawater. A stable reversible capacity of 92.1 mAh g−1 was obtained. Other than chloride ions, there are also reports on the battery using fluoride ion as charge carrier (111). However, cycling stability was limited in the current halogen anion batteries. Apart from halogen anions, Jiang et al. (112) reported the reversible insertion of nitrate into Mn3O4 for aqueous dual-ion batteries. The insertion of NO3− resulted in a capacity as high as 183 mAh g−1 and more than 3500 cycles at 1 A g−1. These achievements imply that there is definitely a margin for developing anions as charge carriers for ABs.

SUMMARY AND OUTLOOK

ABs are rising as the promising energy storage systems for intermittent energy utilization and sustainable large-scale applications. Benefiting from their low cost, abundant resources, easy assembly and recycling, environmental benignity, and, above all, safety, the advanced ABs have potential to replace conventional Li-ion, Ni-MH, and Pb-acid batteries for future automotive, aerial, and scalable energy storage applications. In recent years, we witnessed a rapid development of electrode materials with remarkable electrochemical performance and new electrochemical mechanisms. Although significant advances have been made in this area, unremitting efforts are still required, including pushing the energy/power densities and long-standing stability before meeting the requirements of practical applications. Next, we will summarize the advantages and disadvantages of some typical AB systems and try to provide prospects for the next stage of the development of ABs.

Comparison of different systems

Currently, LIBs, Ni/MH, and lead-acid batteries remain as the mainstream energy storage systems in the world market of rechargeable batteries. LIBs have been the ubiquitous commercial power source for portable electronics, electric vehicles, and backup power supplies as evidenced by their widespread usage in the past decades. The scarce abundance (20 parts per million) and increasing high cost of Li (or Co) pose challenges for using them for grid storage. In addition, some incidents have exposed serious safety concerns of LIBs with organic solvents and hindered their large-scale energy applications (see Table 1). At present, lead-acid ABs are the most recognizable aqueous-based batteries in our daily life and still hold a major proportion of the global battery market. Major market sectors for lead-acid batteries are starting lighting ignition (SLI) for cars, automotive including e-bikes, forklifts, and other vehicles and stationary industrial uses, including uninterruptible power supplies (UPS) and grid-scale energy storage units. However, they are also known to have a low energy density of ca. 35 Wh kg−1, which is less than a quarter of the value of LIBs (see Fig. 6A). They are also limited by problems of toxicity and low charge/discharge efficiency. Nickel-iron batteries have shown their environmental friendliness, longevity, and tolerance to electrical misuse compared with lead-acid batteries, while with the same problems of low energy density and CE (ca. 60%). Ni-MH battery remains a great success for use in hybrid electric vehicles (HEV; such as Prius, Toyota) due to its relatively high energy density, safety, and wide temperature range performance (113). The stagnation of the development can be ascribed to its limited energy density, usage of rare-earth resources, and memory effects compared with LIBs (see Table 1). Recent improvements in alkaline Ni/Co-Zn and Mn-Zn batteries have focused on the advanced nanoengineering design, with increased electrochemical reversibility and decreased formation of irreversible phases including γ-NiOOH, Mn3O4, and ZnMn2O4. These batteries have shown potential for applications as the next-generation power sources in low-speed electric vehicles, battery electric vehicles, HEV, and emerging grid-scale electrical energy storage systems.

Table 1. Comparison of different ABs and other commercialized electrochemical energy storage technologies.

|

Representative battery type |

Electrochemical reaction mechanism |

Electrolyte |

Working voltage (V) |

Theoretical energy density (Wh kg−1) |

Practical energy density (Wh kg−1) |

Cost of electrolyte |

Status |

Advantages (A) versus disadvantages (D) |

| Li-ion battery | LiC6 + FePO4 ↔ LiFePO4 + 6C + e− |

1 M LiPF6 | 3.3 | 385 | ~145 (device scale) | Middle | Commercialized | A: High energy density and good overall performance. D: Safety risk, strict manufacture, limited low- temperature performance, and limited Li/ Co resources. |

| Lead-acid battery |

Pb + PbO2 + 2H2SO4 ↔ 2PbSO4 + 2H2O + 2e− |

5 M H2SO4 | 2.0 | 167 | ~35 (device scale) | Cheap | Commercialized | A: Good safety, low cost, and low self- discharge. D: Low energy density, poor cyclability, and environmental issue. |

| Ni-Fe battery | Fe + 2NiOOH + 2H2O + 2H2O ↔ Fe(OH)2 + 2Ni(OH)2 + 2e− |

2 M KOH | 1.2 | 234 | ~40 (device scale) | Cheap | Commercialized | A: Good safety, low cost, long life, and tolerance to electrical abuse. D: Low energy density and hard to maintain. |

| Ni-MH battery | MH + NiOOH ↔ M + Ni(OH)2 + e− |

6 M KOH | 1.35 | 340 | ~100 (device scale) | Cheap | Commercialized | A: Good safety, wide temperature range, and overchargeability. D: Limited energy density, usage of rare-earth resources, and memory effect. |

| Alkaline Ni(Co)-Zn battery |

Zn + 2NiOOH + 2H2O ↔ Zn(OH)2 + 2Ni(OH)2 + 2e− |

1 M KOH + 20 mM Zn(ac)2 |

1.7 | 372 | ~90 (device scale) | Cheap | Commercialized | A: Good safety, low cost, and good low- temperature performance. D: Limited energy density and limited cycling life. |

| Alkaline Mn-Zn battery (74) |

Zn + 2MnO2 + 2H2O ↔ Zn(OH)2 + 2MnOOH + 2e− |

37 weight % KOH |

1.2 | 358 | ~100 (electrode scale) |

Cheap | Bench scale | A: Good safety and low cost. D: Limited energy density and poor high-DoD cyclability. |

| Li-ion AB (28) | Cn + LiBr + LiCI ↔ Cn[BrCI] + 2Li++2e− |

21 M LiTFSI + 7 M LiOTf |

4.2 | 617 | ~460 (electrode scale) |

Expensive | Bench scale | A: Good safety and high energy density. D: High cost in electrolyte and limited rare capability. |

| Na-ion AB (69) | 2Na3MnTi(PO4)3 ↔ Na4MnTi(PO4)3 + Na2MnTi(PO4)3 + e− |

1 M Na2SO4 | 1.4 | 41 | ~40 (electrode scale) |

Cheap | Bench scale | A: Good safety and low cost. D: Low energy density and limited cyclability. |

| K-ion AB (12) | KFeMnHCF + PTCDI ↔ KxPTCDI + K1−xFeMnHCF |

22 M KCF3SO3 |

1.2 | – | ~80 (electrode scale) |

Expensive | Bench scale | A: Good safety. D: High cost in electrolyte and low energy density. |

| Al-ion AB (101) | AlxMnO2nH2O + (y − x)Al ↔ AlyMnO2nH2O |

5 M Al(OTF)3 |

1.1 | 561 | – | Expensive | Bench scale | A: Good safety. D: High cost in electrolyte and low energy density. |

| Zn-ion AB (85, 96) |